Terra que Deus bemdizia!

NEW YORK: John Lane Company. MCMXII.

Title: Library Cataloguing

Author: John Henry Quinn

Release date: April 5, 2015 [eBook #48645]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Richard Tonsing, Adrian Mastronardi and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(This file was produced from images generously made

available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

LIBRARY CATALOGUING

BY

J. HENRY QUINN

Librarian, Metropolitan Borough of Chelsea; Library Association Examiner in Cataloguing and Lecturer in Librarianship, London School of Economics (Univ. of London.)

LONDON:

TRUSLOVE & HANSON, LTD.

1913.

LONDON: TRUSLOVE AND BRAY, LTD., PRINTERS, WEST NORWOOD, S.E.

Some years ago I prepared a Manual of Library Cataloguing, which met with more acceptance than was expected, and has been out of print for some time. Upon considering requests for a new edition, I concluded that a book upon somewhat different lines would be more likely to meet the present requirements of librarians and library assistants—this volume is the result.

No pretence is made that the work is exhaustive or complete, but it is hoped that it will serve as a practical and useful introduction to the several codes of cataloguing rules. The statements made in it are not meant to be dogmatic, but they indicate the lines upon which good and accurate work is to be accomplished. As the illustrative examples were chosen from every-day books, and are worked out as simply as possible, they should be found useful by beginners; especially in preparing for the examinations of the Library Association in this subject.

I am indebted to my friend Mr. Frank Pacy, City Librarian of Westminster, for reading my proofs and suggesting many improvements, although I am sure he would not care to accept responsibility for all the views expressed or the mode of expressing them.

J. H. Q.

Chelsea,

London, S.W.

July, 1913.

| CHAPTER I. | |

|---|---|

| Introductory. | |

| PAGE | |

| The Difficulties of Cataloguing a Library—The Qualities Desirable in a Cataloguer—The Necessity for Systematic Cataloguing | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Short History of Modern Cataloguing. | |

| The British Museum Rules—Jewett's Rules—Crestadoro's Catalogues—Huggins' Liverpool Catalogue—Cutter's Rules—The Anglo-American Code—Dziatzko's Instruction—Dewey's Classification—The British Museum and other Catalogues | 7 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Dictionary versus Classified Catalogues. | |

| Form to be fixed—The users of Catalogues—Questions Catalogues are expected to answer—The Dictionary Catalogue—The Classified Catalogue—The Alphabetico-Classed Catalogue—Definitions | 19 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Single Author Principal-Entry. | |

| Stationery—The Author-Entry—Full Names—Imprint and Collation—Order of Information Tabulated—Subject-Entry—Headings—Class-Entry | 32 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Joint-Authors. | |

| Joint-Authors—Collations—Synonymous Subject-Headings—Participants in a Correspondence—References—Man and Wife as Joint Authors | 48 [Pg vii] |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Books by more than Two Authors. Composite Books. | |

| Books by Three Authors—Choice of Subject-Headings—Cross-References—Books by a Number of Authors—Ecclesiastical and other Titles of Honour—The use of Capitals—Editors—Dates of Publication—Title-Entries—Punctuation—"Indexing" Contents of Composite Books—Separate Works printed together—Volumes of Essays by Single Authors | 58 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Illustrated Books. Music. | |

| Authors and Illustrators—Translations of Foreign Titles of Books of Illustrations and of Music—The Cataloguing of Music—Librettists—"Indexing" Miscellaneous Music—Dates of Publication | 80 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Publications of Governments, Societies, and Corporate Bodies. | |

| Co-operative Indexes—Publications of Societies—Publishing Societies—Government Publications—Statutes—Colonial and Foreign Government Publications—Local Government Publications—Associations and Institutions—Congresses | 95 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Compound Names. Names with Prefixes. Greek and Roman Names. | |

| Rendering of the Names of Foreign Authors—Compound Names—Changed Names—Foreign Compound Names—Names with Prefixes—Short Entries—Title-Entries—Foreign Names with Prefixes—Greek and Latin Authors | 110 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| First Name Entry. | |

| Monarchs—Queens—Order of Arrangement—Princes—Popes—Series Entries—Saints—Friars—Mediæval Names—Artists, &c. | 132 [Pg viii] |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Noblemen. Oriental Names. | |

| Noblemen—Title v. Family Name—Double Subject-Entry—Oriental Names—Indian Names—Japanese and Chinese Names—Hebrew Names—Maori Names | 148 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Pseudonyms. Married Women. | |

| Pseudonyms v. Real Names—The Better-known Name—Methods of Marking Pseudonyms—Writers who use Two Names—Phrase-Pseudonyms—Specific Entry—Repetition Dashes—Use of Capitals for Emphasis—Women's Names Changed by Marriage—Anonymous Books—The Discovery of Authors of Anonymous Books—"By the Author of ——"—Names consisting of Initials only | 161 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| The Bible and other Sacred Books. Newspapers, &c. | |

| "Anonyma" continued—The Bible and other Sacred Books—Commentaries and Concordances—Newspapers and Periodicals—Directories and Annuals | 185 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Miscellaneous. | |

| Title-Entries—Classics—Specific Subject—Concentration of Subject—Definite Headings—Popular Terms—Historical Fiction—Novels in Series—Sequels—Fiction Known by Special Titles—Books with Changed Titles—Annotations—Form Entries—Summary Hints | 199 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| The Printing of Catalogues. | |

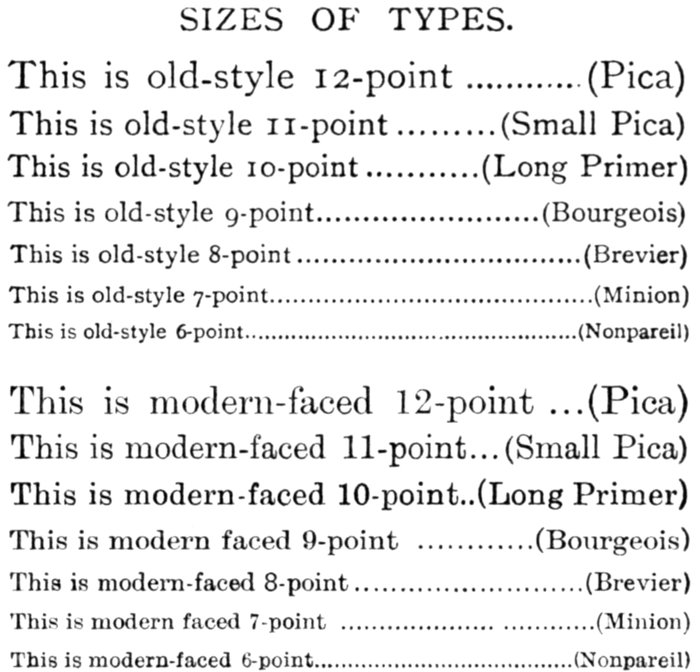

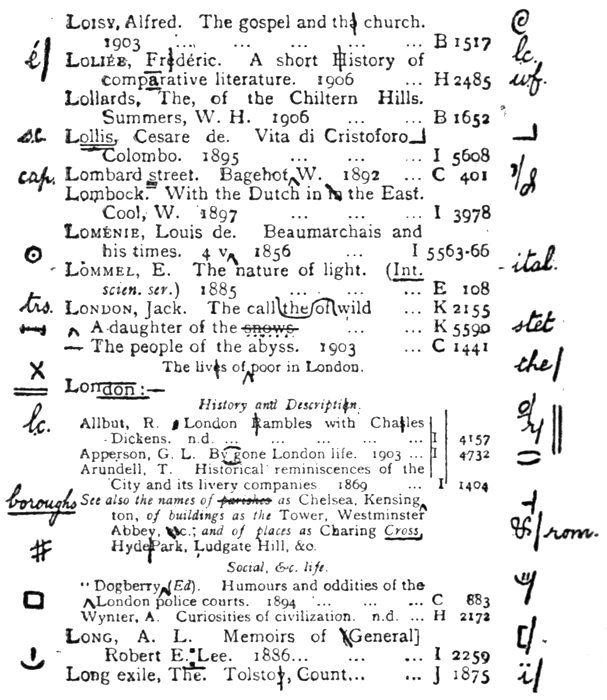

| The Preparation of "Copy"—Markings for Type—Styles of Printing in Various Catalogues—Table of Types—Tenders for Printing—Model Specification—Reading and Correction of Proofs—Type "Kept Standing" | 217 |

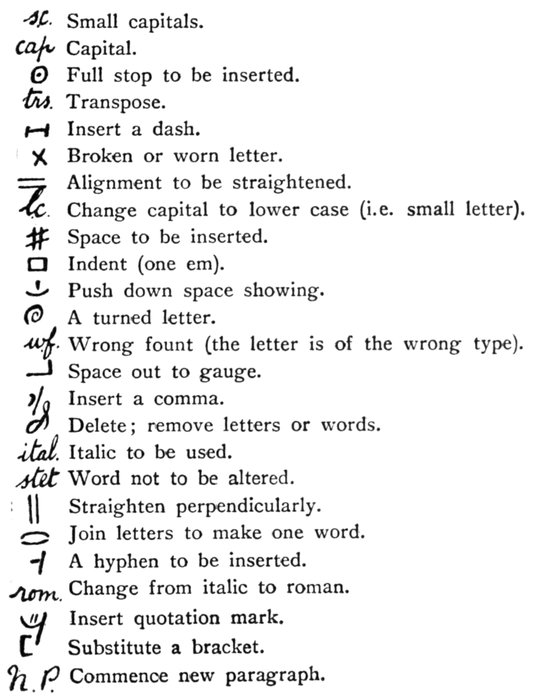

| Appendix A.—The Correction of Printer's Proof | 236 |

| " B.—A List of Contractions | 239 |

| " C.—A List of Pseudonyms with the Real Names | 242 |

| Index | 250 |

Library Cataloguing.

The difficulties of Cataloguing a Library. The qualities desirable in a Cataloguer. The necessity for Systematic Cataloguing.

Among the varied duties of a librarian that of cataloguing his books is generally supposed by the uninitiated to be one of the easiest. The popular idea is that books are sent to libraries—public libraries at any rate—by grateful publishers, when all the librarian has to do is "to catalogue them," put them up in rows on shelves, and hand them out to the first person who asks for them. The cataloguing of a library is ranked with that of any other inventory, and a catalogue popularly regarded as a mere list, calling for no particular knowledge, effort, or care in its production. The late Prof. John Fiske opens an interesting essay on "A Librarian's Work" in his Darwinism and other Essays (Macmillan, 1879) in these words, which are equally applicable to any library of any pretension:—

I am very frequently asked what in the world a librarian can find to do with his time, or am perhaps congratulated on my connection with Harvard College Library, on the ground that[Pg 2] "being virtually a sinecure office (!) it must leave so much leisure for private study and work of a literary sort." Those who put such questions, or offer such congratulations, are naturally astonished when told that the library affords enough work to employ all my own time, as well as that of twenty assistants; and astonishment is apt to rise to bewilderment when it is added that seventeen of these assistants are occupied chiefly with "cataloguing;" for, generally, I find, a library catalogue is assumed to be a thing that is somehow "made" at a single stroke, as Aladdin's palace was built, at intervals of ten or a dozen years, or whenever a "new catalogue" is thought to be needed. "How often do you make a catalogue?" or "When will your catalogue be completed?" are questions revealing such transcendent misapprehension of the case that little but further mystification can be got from the mere answer, "We are always making a catalogue, and it will never be finished."

Prof. Fiske then proceeds to describe the difficulties of cataloguing a library: "just cataloguing a book" not being by any means so simple a task; and he goes on to demonstrate that the work requires "considerable judgment and discrimination" besides "a great deal of slow, plodding research." Perhaps there is no literary labour of the kind, mere "hewing of wood and drawing of water" though it be, that so quickly takes the conceit out of those essaying it, they finding it both "arduous and perplexing." "The peculiarities of titles are, like the idiosyncrasies of authors, innumerable. Books are in all languages and treat of subjects as multitudinous as the topics of human thought." A good[Pg 3] cataloguer should be learned in the history of all literary, scientific, religious, philosophical, economic, and political movements of all ages and all countries, and especially must he be abreast of the times in a knowledge of men and things, literary, scientific, and otherwise. He needs be something of a linguist, should be exact, orderly, methodical, with fixed ideas and yet an open mind, painstaking, and persevering. Even with the exercise of all these attainments and qualities, his work will not be found to be beyond criticism. No pretence is made to assert that cataloguers as a body do conform to this ideal; if they did it is probable they would find more profitable employment. The next best thing to possessing these qualifications, however, is to have as many as can be attained, and make up for the rest by knowing where to find information as needed. If the cataloguer be not "a walking encyclopædia" in himself, he at least should know how to utilise the printed ones, and all other literature at his command.

There are many kinds of library catalogues ranging from the mere lists made by private persons of their own books to the great "Catalogue of Printed Books in the British Museum," which is so extensive by reason of the number of books contained in it, that its entries are virtually limited to a single item for each book. Whether small or great, the principles governing their compilation are much the same, the following chapters being principally intended as a guide to the cataloguing of a public library of average size.

No matter how good a library may be, its collections are practically lost and useless without an[Pg 4] adequate, properly-compiled catalogue. As Carlyle puts it "A big collection of books without a good catalogue is a Polyphemus with no eye in his head." Even an indifferent library can be made to render comparatively good service with a good catalogue. In order to compile such a catalogue it is essential that certain particulars be given descriptive of the books, and in so systematic a way that, while the entries will afford all reasonable information to the person well-versed in books, they shall, at the same time, be so clear and simple in character as to be understood without much effort by anyone of average intelligence. These particulars should be comprehensive enough to afford some general idea of the nature and scope of the book described without actually examining it, though in this respect much depends upon the character and resources of the library. The full descriptions usual in special bibliographies meant for experts are not to be expected or required in the catalogue of a popular general library.

The value of a good catalogue does not depend upon its extent or size any more than does that of a good book, but rather upon the exactness of the method by which the information given is digested and concentrated. There are library catalogues so elaborately compiled and imposing in appearance that they might be, and often are, considered to be most excellent productions, whereas those who use them find them little more than a medley of book-titles—pedantic without being learned. On the other hand, "infinite riches in a little room" would often be an appropriate motto for some insignificant-looking catalogue. Sometimes it happens that quite[Pg 5] a small library has a large catalogue. This does not always arise from a desire to make the most of the library, but may, likely enough, be owing to the fact that the compilation was undertaken by some over-zealous committeeman or other amateur, who, being "fond of books," considered this a sufficient qualification for cataloguing them without knowing that it is far easier to over-catalogue a library than to do the work judiciously—the result being both wasteful and disastrous. The first catalogues of the smaller public libraries are sometimes of this character, not always for the reason just stated; probably owing to the desire to save the salary of the librarian by postponing his appointment to the last moment. He is then expected to select and purchase the books as well as produce a printed catalogue of them within a few weeks: the conception being that a library can be selected, arranged, and listed in bulk as goods are bought, displayed, and ticketed in a shop, and in as short a time. The cataloguing, then, has perforce to be delegated to an assistant, who possibly has no training whatever. For this reason and others the catalogue of a new public library can seldom be taken as representing the knowledge or ability of the librarian as a cataloguer.

With the spread and rise in the standard of education, more exact and better work is now demanded in libraries than was the case during the early years after the passing of the first Public Libraries Act. The slipshod, unsystematic cataloguing at one time in vogue is not acceptable now, and the public demands something more than bald lists compiled upon no principle in particular, which[Pg 6] are often more bewildering than helpful to an inquiring reader. The student and that interesting person "the general reader" have a better understanding than formerly of the uses and peculiarities of books, and look for precise information concerning them. No better evidence of the general interest taken in books is needed than that afforded by the large place occupied by the reviewing of literature of all kinds in the daily press and popular journals, even in minor periodicals. There must be a public for such reviews, otherwise editors would not provide them; and, no doubt, the spread of libraries has something to do with it. The old dictum that it was not the business of a cataloguer to go behind, or add to, the information deemed sufficient by an author for the title-page of his book does not now find acceptance.

Those who are possessed of even a little experience will know that it is impossible to compile a library catalogue in a haphazard fashion, and that clear and definite rules for guidance must be laid down before any part of the work is attempted, otherwise confusion and want of proportion will result, to say nothing of the likelihood of the loss of work already done. Happily for a number of years now the rules governing the proper compilation of catalogues have been codified, and the following chapters, while based upon no particular code, are meant to serve as a practical introduction to the best-known of them with some little modifications that have been found to be convenient in practice.

The British Museum Rules. Jewett's Rules. Crestadoro's Catalogues. Huggins' Liverpool Catalogue. Cutter's Rules. The Anglo-American Code. Dziatzko's Instruction. Dewey's Classification. The British Museum and other Catalogues.

Before proceeding to consider the practical side of the subject, we may take a brief glance at the history of modern cataloguing of public libraries in this country. The earlier catalogues were limited either to author-entries or were classified according to the whims of the compiler, sometimes according to the rooms or shelves in which the books were placed.

The subject of cataloguing received the most serious attention in the year 1850, and, roundly, we may date its history from then. "The Rules for the Compilation of the Catalogue of Printed Books in the Library of the British Museum" had been adopted in 1839, and were printed in 1841. In a great measure they may be regarded as the basis of all cataloguing rules since that time, at any rate for author-entry or its equivalent. In 1850 a Royal Commission on the management of the British Museum had sat and issued its report, and rate-supported public libraries were coming into existence. There had been much discussion on the need for an adequate and promptly-produced catalogue of the books in the Museum, and many views upon[Pg 8] the subject were set forth, especially by literary experts. Their criticism was in the main directed against the existing rules known as Panizzi's. Anthony Panizzi, then Principal Librarian, with others of the Museum staff, including Thomas Watts, Winter Jones, and Edward Edwards, had each separately prepared a set of rules according to his own ideas for the compilation of the projected catalogue, and these were afterwards discussed by the compilers collectively, and differences of opinion decided by vote.

The Secretary of this Royal Commission was J. Payne Collier, and he was one of the opposers of Panizzi's rules, especially taking exception to the fulness of entry because of the delay it entailed. To show practically how he would catalogue he tried his hand on twenty-five books in his own library and submitted the results. Mr. Winter Jones reported upon it, and said it contained almost every possible error which can be committed in cataloguing books. Payne Collier's attempt and his justification of it appear in the first part of the Gentleman's Magazine for 1850, where it will be seen that a German edition of Shakespeare is entered under the editor alone, and a play of Aristophanes is also so treated, besides other mistakes of a very amateurish nature.

In this same year (1850) attention was being directed in America to library cataloguing. The Smithsonian Institution sent out a circular to the effect that, being desirous of facilitating research in literature and science, and of thus aiding in the increase and diffusion of knowledge, it had resolved to form a general catalogue of the various libraries[Pg 9] in the United States. The librarian of the institution, Prof. Charles C. Jewett, had prepared plans for the accomplishment of this object. The first part related to the stereotyping of catalogues by separate titles in a uniform style. This stereotyping was proposed to save time, labour, and expense in the preparation of new editions of such a general catalogue. Only as many copies as were needed for present use were to be struck off, and then new editions were to be printed from time to time with later additions also in stereotype. This idea, though it crops up from time to time, has now no novelty about it, though recent inventions in type-setting machines have certainly given cause for its reconsideration. No plan of this kind, particularly if it were to be co-operative among the libraries, could be of the least value unless there were uniformity of compilation according to fixed rules, and so the second part consists of a set of general rules to be recommended for adoption by the different libraries of the United States in the preparation of their catalogues. Jewett's code was based upon Panizzi's "Rules for the British Museum," with modifications and additions to suit them to general use, and more especially in connection with his proposed co-operative catalogue. Upon this point he says, "The rules for cataloguing must be stringent, and should meet as far as possible all difficulties of detail. Nothing, so far as can be avoided, should be left to the individual taste or judgment of the cataloguer. He should be a man of sufficient learning, accuracy, and fidelity, to apply the rules." In order to emphasise further the need for uniformity, he[Pg 10] proceeds to say that "if the one adopted were that of the worst of our catalogues, if it were strictly followed in all alike, their uniformity would render catalogues thus made far more useful than the present chaos of irregularities." From his point of view of a national catalogue, he was perfectly right, though for general cataloguing the argument is not convincing. Probably there is room for a greater degree of uniformity in the catalogues of public libraries than exists at present, and a better understanding upon this point might be of some advantage to readers and workers generally. The fact that catalogue rules of a standard kind exist does not seem to have exercised any great influence in this respect.

The full title of Jewett's work is "On the Construction of Catalogues of Libraries and their Publication by means of separate Stereotyped Titles, with Rules and Examples, by Chas. C. Jewett, Librarian of the Smithsonian Institution, Washington." The first edition was issued in 1852, and another in the following year. The number of rules is thirty-nine, and they are furnished with a series of examples and a specimen subject-index. This may be regarded as the first code of rules which contains subject-entries as well as author-entries.

In 1856, some two years before Jewett put his rules into practice in a catalogue of the Boston Public Library, Mr. A. Crestadoro published a pamphlet on "The Art of Making Catalogues of Libraries." The system he recommended was to compile the catalogue with the titles of the books given fully, leading off with the author's names, but[Pg 11] arranged in no particular order. These entries were to be consecutively numbered. To this list of books there was to be an index of authors and subjects in a brief form with the number referring to the entry in the main catalogue. The subject-words were to be taken from the titles of the books themselves and accordingly books with synonymous titles were entered under those titles with such cross-references as were needed. This method was put into force by Crestadoro when librarian of the Manchester Public Library, and the catalogue still remains in use for the older books in the Reference Library there. The first volume was published in 1864, the entries being numbered from 1 to 26,534, though they are arranged more or less alphabetically under authors' names, or the principal subject-words if anonymous. To this volume is attached a brief subject-matter index. Two later volumes were published in 1879, and in these the books are apparently entered very much as they were received into the Library. A separate volume, however, serves as an index, both of authors and subjects, to all three volumes, and this volume is still the real finding catalogue, the volumes with the full particulars being little used in comparison.

This index-form of brief entries of authors and subjects in one alphabet was utilised for catalogues of lending libraries in Manchester; the following example of later date being taken from one of these:—

Glacial Period, Man and the. By Wright

Glaciers of the Alps: a Lecture. By Molloy

Gladiators. By Melville

[Pg 12]Gladman (F. J.) School Method

Gladstone (Catherine) Life of. By Pratt

Gladstone (J. H.) Michael Faraday.

Gladstone (W. E.) Biography of. By Russell

— Biography of. By Smith

— Character of.

— England under. By McCarthy

— Essay on. By Brown

— Gladstone's House of Commons. By O'Connor

— Gleanings of Past Years

— Government. By Kent

— Homer

— Impregnable Rock of Holy Scripture

A similar arrangement was also adopted for the Birmingham Public Library by the late J. D. Mullins in 1869.

At this time, or a little earlier, Samuel Huggins, a retired architect, was engaged by the Liverpool Corporation to compile a catalogue of the Public Reference Library there. He took Jewett's Catalogue of the Boston Public Library as his model, but with certain modifications. He says "in the shaping out of all its chief features—Poetry, Painting, Music, Architecture, the Drama, Novels, and the Bible group, it has been so treated as to constitute it an original and unique catalogue, which in regard both to form and detail of these great departments of the field of knowledge is superior, so far as I know, to any other work of the kind. The subjects generally are more concentrated, brought into fewer and larger groups than in the excellent catalogue just named"—that is Jewett's Boston one. One of the principles that he lays down is that a book of science or art with a geographical limitation will be found not under the scientific subject of which it treats, but under the name of[Pg 13] the country or place to which the scientific research is confined, and so a book on the conchology of France does not appear under Conchology but under France—subject division "Natural History." Mr. Huggins apparently was not satisfied that this idea met all needs as he printed an appendix to his volume "wherein for the greater convenience of the student, those works in the catalogue which, by the geographical principle of distribution, are classed under the places to which their subjects respectively are confined, and so, wide scattered, are brought together, and grouped according to their subject." The work was published in 1872, its main principles being more distinctly those we now understand by the form "a dictionary catalogue" and it was probably the first of the kind in this country. Under the older index catalogues a book upon Palestine might be under such headings as Palestine, Holy Land, Land of Promise, Lands of the Bible, Bible Lands, or any other title adopted by the authors on their title-pages, whereas these were all concentrated under a single heading with such reasonable references and cross-references as were needed to bind the whole together or "syndetic" as Cutter terms it. This catalogue is still in use in the Liverpool Reference Library, but has been improved in detail in the later supplementary volumes, including the elimination of the form-headings, of which Mr. Huggins made so much.

Other developments in library cataloguing about this period lay more in the direction of attempts to combine the hitherto almost general classified catalogues with subject and author catalogues in the unsatisfactory alphabetico-classed form.

Up to this time, however, there was no adequate code of rules suited to all requirements. As we have seen, the British Museum rules were for author-entry, and Jewett's were by no means complete enough for the purpose. In 1876, Mr. C. A. Cutter published his "Rules for a Printed Dictionary Catalogue," this work forming the second volume or part of the "Special Report of the U.S. Bureau of Education on the History, Condition, and Management of Public Libraries in the United States of America." These rules numbered 205 as compared with Jewett's 39, and Mr. Cutter put them into use in, if they were not actually based upon, his large Catalogue of the Library of the Boston Athenæum. A second edition of these rules, with corrections and additions, was issued as a separate work in 1889, a third in 1891, and a fourth in 1904. This last edition contained Mr. Cutter's latest corrections and additions (he died in September, 1903), the number of rules being increased thereby to 369. It is at present the standard and most exhaustive work of the kind, and is unlikely to be soon superseded, though it will be improved upon from time to time as library practice requires and its essential principles become embodied in other codes. Librarians of all ranks are indebted to the American Government for the generosity with which they distributed it freely to applicants.

Both the American and British Library Associations formulated rules—the former in 1878 and the latter in 1883—though neither can be said to have been of much service, the American being a condensation of Cutter with some unimportant variations,[Pg 15] and the British getting no further than author and title entries. The two Associations have now combined in a series of rules known as the "Anglo-American code" and entitled "Cataloguing Rules, Author and Title Entries, compiled by Committees of the American Library Association and of the Library Association." This was published in 1908, and the history of its production forms a preface to the work. A fuller history and description of it by the Secretary of the British Committee, Mr. John Minto, is contained in the Library Association Record, volume 11, 1909. A noteworthy statement he makes is "I do not think that it was supposed to be the business of the Committee to provide for the needs of very small libraries, which, on account of the inadequacy of their funds, are unable to provide full catalogues, and are obliged to be content with mere title-a-line lists. The requirements of such libraries are already well served with existing codes—for example Cutter's Rules which provide alternative forms, short, medium, and full, for various grades of libraries." For this very reason the Anglo-American code will never find much favour for practical use in this country, though it is at present the basis for the Library Association examinations in this subject.

In 1886 Prof. Dziatzko published his "Instruction für die Ordnung der Titel im alphabetischen Zettelkatalog der Königlichen und Universitäts-Bibliothek zu Breslau" which Mr. K. A. Linderfelt of Milwaukee translated and adapted in 1890, with the other standard rules, under the title "Eclectic Card Catalog Rules, Author and Title Entries, based on Dziatzko's 'Instruction' compared with[Pg 16] the Rules of the British Museum, Cutter, Dewey, Perkins, and other Authorities." It is so ample in its details that it covers all possible forms of authors' names and is therefore most valuable for reference or for compiling any catalogues, though it may contain a great deal that is rarely required in average library practice. The appendix, containing a list of oriental titles and occupations with their significance, is a useful feature of the work.

So many classified catalogues have appeared of late years arranged according to the Dewey Decimal System that no notes upon the history of cataloguing would be complete without some reference to that system. There is no doubt that it is mainly responsible for the revival of this form of catalogue. The system was planned or invented by Mr. Melvil Dewey, when librarian of Amherst College, U.S.A., and was in the first instance intended for cataloguing and indexing purposes, though it is now more commonly used for classifying and numbering the books upon the shelves. It was the result of a good deal of careful study of library needs and, on the face of it, is simple and practical. As to this Dewey says "in all the work philosophical theory and accuracy have been made to yield to practical usefulness. The impossibility of making a satisfactory classification of all knowledge, as preserved in books, has been appreciated from the first, and nothing of the kind attempted. Theoretical harmony and exactness have been repeatedly sacrificed to the practical requirements of the library."

In spite of this statement it is astonishing how few defects it has as a system of classification,[Pg 17] especially when it is remembered that every class and every subject is divided into ten heads. This limitation has the tendency to congest some subjects while others do not admit of the use of so many as ten numbers. Withal it is very elastic and useful, though, as may be expected, things American get preferential and fuller treatment. The first edition was published from Amherst College Library in 1876, the second from Columbia College Library in 1885, the third in 1888, the fourth from the New York State Library in 1891; the last ("edition 7") being that of 1911, each being a revision and enlargement of the earlier edition. The very full index attached to the scheme makes it comparatively easy to use, but, in the process of using, it is astonishing how many books have to be specially considered as to their correct place, a comparison of catalogues compiled under the system showing that different minds have interpreted the scheme quite differently.

There are other schemes of classification applicable to cataloguing, as for instance that known as the "Expansive," the compilation of the late C. A. Cutter, and the "Adjustable" of Mr. J. D. Brown. This last is used in several public libraries worked upon what is termed the "open access" system. The earlier history of classified cataloguing is treated fully enough for most purposes in Mr. J. D. Brown's books on library classification.

Even this mere sketch in outline of cataloguing history would be incomplete without some allusion to the printing of the "British Museum Catalogue of Printed Books." The printing of the first portion, containing the books to the end of 1881, was the[Pg 18] work of twenty years, and consists of 393 parts, which superseded more than 2,000 folio volumes of the manuscript catalogue. The supplement containing the books added to the Museum during the years 1882-1899 was completed in 1905, and those who have the opportunity of constant reference to the pages of the complete work know how valuable—even indispensable—it is, and look forward to the appearance of the next supplement. Decennial supplements would be none too frequent.

When to-day so many excellent catalogues of libraries are produced it would be invidious to single out any for special praise, but no excuse is needed for naming that of the London Library published in 1903 with its subject volume of 1909, both volumes being remarkable for condensation and accuracy. At this time (1913) a new revised and enlarged edition is announced for publication.

Mr. H. B. Wheatley's interesting little book, "How to Catalogue a Library," must not be overlooked in connection with the history of modern library cataloguing, particularly the chapter on "The Battle of the Rules."

Form to be fixed. The users of Catalogues. Questions Catalogues are expected to answer. The Dictionary Catalogue. The Classified Catalogue. The Alphabetico-Classed Catalogue. Definitions.

We now proceed to consider the needs of those for whom our catalogues are prepared.

It may be presumed that most of those who use this book are engaged in municipal or similar libraries, where the requirements of the many must be taken into account rather than the special needs of the few. For those who have yet to acquire experience it is as well to state that in cataloguing, as in most other departments of library work, a definite decision as to the form and methods to be adopted must be made at the outset, as it is impossible to start upon one form and then change to another without confusion or the sacrifice of work already done. Then, again, readers as a rule are extremely conservative, and not only dislike a change but are quick to resent it even when the advantages are sufficiently obvious to warrant it. Librarians and their assistants, too, get accustomed to a particular method, and after several years of working find it difficult to make a change to another without it affecting their work, often unconsciously.

The spread of education and reading nowadays would lead us to suppose that most people possess[Pg 20] a sufficient amount of general knowledge to enable them to make an intelligent use of a catalogue, provided it is compiled upon well-defined and logical principles. Should the compiler happen to have all the accomplishments named in Chapter I., and yield to the temptation to air them by the production of a highly scientific catalogue, he will find that his labours are unappreciated, and that he must adapt his work to the needs of the average "man in the street." Mr. H. B. Wheatley says as to this "that some persons seem to think that everything is to be brought down to the comprehension of the fool; but if by doing this we make it more difficult for the intelligent person, the action is surely not politic. The consulter of a catalogue might at least take the trouble to understand the plan upon which it is compiled before using it." Mr. Wheatley's experience is not that of public librarians generally, as not one person in a thousand does take this trouble.

However this may be, there is no difficulty in attaining the happy medium whereby the ignorant (speaking, of course, comparatively) finds his wants met as readily as the most learned, and with simplicity and thoroughness. It has been put in other words thus: "The right doctrine for a public library catalogue is that it should be made not from the scientific cataloguer's point of view, with a minimum of indulgence for ignoramuses, but from the ignoramus's point of view with a minimum, of indulgence for the scientific cataloguer. That the person who not only does not know but does not even know how to search should be primarily provided for." Therefore this idea of suiting the needs[Pg 21] of the particular public using the library must never be overlooked by the cataloguer.

Besides considering what are likely to be the needs of the majority of the readers who will use the library to be catalogued, we must decide what is the maximum amount of information that the catalogue should afford them, also which form will give the most of this information with the least trouble and delay to the inquirer.

What are the questions likely to be asked that a catalogue can be reasonably expected to answer? These do not exceed a dozen, and are as follows:—

1.—Have you a particular book by a given author?

2.—What books have you by a given author?

3.—What books in the library has a particular person edited, translated, or illustrated?

4.—What books have you upon a specific subject? say roses.

5.—What books are there relating to a general subject? say all kinds of flowers.

6.—What books have you in a particular class of literature? say biography or theology.

7.—What books have you in a particular language?

8.—What books have you in a particular literature? say French. (This is a somewhat remote but not unreasonable question.)

9.—Have you a book (author unnamed) bearing a particular title? and, on the same footing with this inquiry, Have you any of the series called so and so?

10.—What books have you in a particular form of literature? as poetry.

11.—Have you a novel or other work by a particular author dealing with a particular period? or any similar question relating to the inner nature of a book.

12.—In what volume of an author's works is a particular essay contained? (This last question is really the same as the first in another form.)

The first and second questions will be answered by a catalogue consisting of author-entries, that is a dictionary of authors, or if compiled under the British Museum rules it will answer these and the third also to a large extent. In addition it should answer No. 12. Questions 4, 5, 6, and 10 can be answered by means of the catalogue known as classified—the entries being arranged in general classes and sub-divided as necessary, but logically, according to the scientific relations of the subjects of the books. If an author-index is added other questions also would be answered with a little trouble. The same questions will be answered by the form known as alphabetico-classed—that is a catalogue of subject, class, and form entries arranged alphabetically.

No one style of catalogue, however, will answer all of these questions, but the one that will answer most of them with the least trouble and loss of time to the user is that known as the dictionary catalogue. It consists of an arrangement of author, subject, and (to a limited extent) title entries in a single alphabetical sequence, and is by far the most popular form. It is neither economical nor the most logical, but its[Pg 23] convenience for ready reference compensates for these defects. It ordinarily answers questions 1, 2, 4, 5, 9, and can be made to answer questions 3, 7, 11, and 12—that is nine questions out of the twelve.

The two most common forms of catalogues are the dictionary and the classified. For many years much controversy has arisen respecting their comparative usefulness, and there is much to be said in favour of both, each having merits, as already shown, not possessed by the other. The late C. A. Cutter points out the advantages of the classified catalogue, thus: "One who is pursuing any general course of study finds brought together in one part of the catalogue most of the books he needs. He sees not merely books on the particular topic in which he is interested, but in immediate neighbourhood works on related topics, suggesting to him courses of investigation which he might otherwise overlook. He finds it an assistance to have all these works spread out before him, so that he can take a general survey of the ground before he chooses his route; and as he goes back, day after day, to his particular part of the catalogue he becomes familiar with it, turns to it at once, and uses it with ease. The same is true of the numerous class who are not making any investigation or pursuing any definite course of study, but are merely desultory readers. Their choice of books is usually made from certain kinds of literature or classes of subjects. Some like poetry or essays or plays [curiously he omits novels]; others like religious works, or philosophical works, or scientific works, not caring about the particular subject of the book[Pg 24] so much as whether it be well-written or interesting. To these persons it is a convenience that their favourite kind of reading should all be contained in one or two parts of the catalogue, and freed from the confusing admixture of titles of a different sort. An alphabetical list of specific subjects is to them little more suggestive than an alphabetical list of authors. It is true that by following up all the references of a dictionary catalogue under Theology, for example, a man may construct for himself a list of the theological literature in the library; but to do this requires time and a mental effort, and it is the characteristic of the desultory reader that he is averse to mental effort. What is wanted by him and by the busy man when now and then he has the same object, is to find the titles from which he would select brought together within the compass of a few pages; few, that is, in comparison with the whole catalogue. It may be 500 pages, but 500 pages are better than 10,000. The classed catalogue is better suited also than any other to exhibit the richness of the library in particular departments."

Cutter, at the same time, proceeds to name some of the disadvantages of this style of catalogue. "A large part of the public are not pursuing general investigations. They want to find a particular book or a particular subject quickly; and the necessity of mastering a complex system before using the catalogue is an unwelcome delay or an absolute bar to its use." Then, again, there is the difficulty of want of agreement as to classifications. The simple remedy for such difficulty is an alphabetical index of all the subjects appearing in the catalogue, whereby an inquirer is directed[Pg 25] to the particular part of the catalogue in which he will find books upon the subject or topic he wants. There are very few, if any, catalogues of the kind without indexes now, though in the early days they were seldom provided.

As said already, early catalogues of libraries were mostly either classified or simply author catalogues. The classification was, often enough, very poor, the sub-division not being carried very far, and this led to the invention or evolution of the dictionary catalogue and brought the classified, such as it was, into disrepute.

The cataloguing of a library is one of the most troublesome and expensive departments of its administration. The cost of printing is greater than ordinary printing, and the expense to a library with its limited income is always serious, because people will not buy a catalogue even at half the cost price of printing but prefer to make use of the copies provided at the desks. Moreover, at the end of six or even fewer months after publication the public usually regard it as out of date and decides to wait for the next edition. In this respect the classified catalogue has the advantage, as it costs less to print, and for this reason, as well as owing to the custom of admitting readers to the shelves of public libraries, there has been a revival of this style of catalogue in late years, especially as it serves as a key or guide to the arrangement of the books upon the shelves of "open access" libraries. It can moreover be printed and issued in sections without affecting its completeness in the end.

The dictionary form, as distinguished from a mere alphabetical list of authors, consists[Pg 26] of entries of books under their specific subjects, instead of their classes. To quote Cutter again: "Thus if a book treats of Natural History it is put under that heading; if it treats of Zoology alone that word is the rubric; if it is on Mammals it will be found under mammals; and, finally, if one is looking for a treatise on the elephant, he need not know if that animal is a mammal; he need not even be sure that it is an animal; he has merely to be sufficiently acquainted with his alphabet to find the word Elephant, under which will appear all the separate works that the library contains on that subject. Nothing, one would think, can be more simple, easy to explain, easy and expeditious to use than this. No matter what he wants he will find it at once provided that the library has a book on just that subject and that it has been entered under the very word which he is thinking of. If these conditions are not fulfilled, however, there is more trouble. If the library has no book or article sufficiently important to be catalogued on that topic he must look in some more comprehensive work in which he will find it treated (as the history of Assyrian art is related in the histories of Art), in which case he will get no help whatever from any dictionary catalogue yet made, in finding the general work, he must trust to his own knowledge of the subject and of ordinary classification to guide him to the including class, or there may be something to his purpose in less general works (as books on Iron bridges or Suspension bridges might be better than nothing to a man who was studying the larger subject Bridges), but in this case also[Pg 27] he will very seldom get any assistance from dictionary catalogues, and must rely entirely upon his previous knowledge of the possible branches of his subject. Even in those catalogues which relieve him of this trouble by giving cross-references, he must look twice, first for his own word and then for the word to which he is referred from that."

A judicial statement of the merits of both these styles of catalogue is contained in a paper by Mr. F. T. Barrett, of Glasgow, entitled "The Alphabetical and Classified Forms of Catalogues compared," printed in the Transactions of the Second International Library Conference, 1897. In the Library Association Record, 1901 (pt. 1), pp. 514-531, there is a verbal and friendly duel between Mr. W. E. Doubleday and the author upon the matter, mainly from the practical point of view.

The Alphabetico-Classed catalogue, as its name denotes, is an attempt at a classified catalogue in alphabetical order of subjects or classes, and is a mixture of the two systems already spoken of, and about as satisfactory as hybrids usually are. The late Prof. Justin Winsor characterised it as "the mongrel alphabetico-classed system, a primarily classed system with an alphabetical graft upon it is a case of confusion worse confounded." The great difficulty both to compiler and user is to know where the subjects leave off and the classes begin—in other words, whether a subject or a class entry is likely to be the one wanted. One of the best examples of this kind of catalogue is the late Mr. Fortescue's "Subject Index to the British Museum Catalogue," and he apparently experienced[Pg 28] the difficulty of deciding, as for instance a book on the elephant appears under Elephant, but a work upon the Elk must be looked for under "Deer." The usefulness of this particular catalogue cannot be gainsaid as its value is too well known, mainly because there is no other form of subject-catalogue for the library of the British Museum. Besides it has such a comprehensive series of cross-references that difficulty is largely obviated, and then again it is only meant as a subject supplement to the principal catalogue. Admirable as it is, we may see how it works out in practice. Suppose we are interested in Law. Under the heading "Law" we find a large number of entries divided into particular kinds of law as "Commercial," "Criminal," "Ecclesiastical," &c., and these are further sub-divided under the names of countries. One would suppose that the subject would be here treated in a most exhaustive manner. But that is not so, as if we require books on the Laws of England we must turn to the word "England." Thus we have books on English criminal law under "Law"; a book upon English general law under "England"; and a book say upon English election law under "Elections, Law of." If it is right to put books on the law of elections under Elections it might be assumed that books on criminal law would go under "Criminal law," but there is not even a reference to say where they are to be found. Admittedly "Law" is a large and complex subject, and would fill many pages if the books upon it were brought together. As it is the searcher must take a long time to ascertain in any exhaustive manner what books upon the subject[Pg 29] are contained in Mr. Fortescue's Indexes. Even if the inquiry is narrowed down to say Italian law, searches must be made in many places without touching special Italian law at all. However there is no system but has its drawbacks, though probably the alphabetico-classed has the most.

There is such a thing as a dictionary system that combines an unseen but systematically classified system. Its root method would be to adopt some thorough scheme of classification permitting of the finest possible detail in topic and adjust thereto any necessary cross-references to cover synonymous names and double subjects. The cataloguer would keep the complete scheme in all its details before him and, by means of an alphabetical index to every adopted name, he would have a list of the subject-headings in dictionary order and to these he would adhere. There would still be specific entry. This is the method that should be pursued in the compilation of dictionary catalogues. The classification may exist only in the mind of the cataloguer and be formulated in no other way unless he relies upon headings already fixed in his catalogue. By trying to adjust headings in such catalogues to any logical classification one can soon ascertain whether they are systematic or haphazard.

The following definitions should be noted before proceeding to the next chapter:—

Author-Catalogue is one in which the entries are arranged alphabetically according to the names of the authors (a dictionary of authors).

Title-Catalogue is one in which the entries are arranged alphabetically according to some word of[Pg 30] the title, especially the first (a dictionary of titles).

Subject-Catalogue is one in which the entries are arranged according to the subjects of the books, alphabetically by the words selected to denote those subjects (dictionary arrangement). If these subject entries are not arranged alphabetically, but are formed into classes philosophically according to the scientific relations of the subjects, then it is a classed or classified catalogue.

Form-Catalogue is one in which the entries are arranged according to the forms of literature and the languages in which the books are written, either alphabetically or according to the relations of the forms to one another.

Apart from these there is a style of catalogue in which the entries are selected to suit the kind of person for whom the books are designed. A catalogue of books for children would be of this order. While it would include books in all classes of literature written to suit juvenile capacity, yet it may reasonably be regarded as a class in itself, and a place is usually assigned to it in a classified catalogue.

When a catalogue of a particular class of literature is separately published it is called a Class-List. A catalogue of novels, or of poetry, or of music would be so termed.

By the term Dictionary Catalogue we understand a combination of the first three, viz., Author, Title, and Subject catalogues in a single alphabet.

The last two forms when thrown together, not in alphabetical but in logical arrangement, make the Classified Catalogue.

The same two if arranged alphabetically and not logically form the Alphabetico-Classed Catalogue. With this last form the author-catalogue could be combined without any disturbance of its arrangement. It can only be added to the classified as an index or appendix.

Stationery. The Author-Entry. Full Names. Imprint and Collation. Order of Information Tabulated. Subject-Entry. Headings. Class-Entry.

To study systematically the various codes of cataloguing rules is of great value to the beginner in the work of cataloguing a library, though the apparent variations and contradictions in the codes are at first somewhat confusing. Their practical application to work in hand serves better to prove the usefulness and necessity of adopting some code or a modification of it before much progress is made. Once a choice is made, it is better to adhere to it uniformly throughout.

The purpose of the catalogue has a bearing upon the nature of the stationery required. A catalogue cannot be written into a book like an inventory; each item—even books by the same author or upon the same subject—must be upon a separate paper slip or card cut uniformly to any size fixed upon. Paper slips serve quite well for manuscript, or "copy" as it is termed, for the printer, but tough cards of good quality are needed for a catalogue on cards to be handled by many persons. It is a good plan in any case first to prepare the catalogue upon slips or cards for office use; then, when checked and revised, to copy from these for public use, either upon the good quality cards as suggested, or into the book-form of catalogues with separate[Pg 33] leaves, known as "sheaf-catalogues." This last-named form is preferable for public use, and takes up less room. Any size of slips or cards may be adopted provided they are exactly cut to a fixed size, 5 inches by 3 inches being convenient; or the size usually provided with the index filing outfits, now so generally in commercial use, which were first used in the cataloguing of libraries, and then applied to other purposes. If the slips or cards are for handwriting, they should be ruled "feint" across, and whether so written or typed, are better with red lines marking margins of about half an inch at each side. If written by hand, the writing should be round, clear, of fair size, and above all, free from flourishes, whether written for public use or for the printer.

Two of the first questions a catalogue will be expected to answer are

Have you a particular book by a given author?

What books have you by a named author?

These two questions are not precisely identical, though they are both answered by the same form of catalogue entry, namely, that under the surname of the writer of the book, known as the "author-entry." This, or some substitute therefor, is invariably regarded as the main, or principal, entry. Though the placing or position of such an entry is not the same in both the dictionary and classified forms of catalogue, one falling under the author's name according to its place in the alphabet, and the other into its position in a class, the form of the entry itself is the same in both. The particulars for this entry must always be taken from the full title-page of the book, never from[Pg 34] the binding or from the preliminary or half-title, though at times this half or "bastard-title" will furnish the name of the series or some other detail not given elsewhere but wanted for full-entry.

The title-page of the first book we deal with reads:—

The surname of the author then is Bell, and we either enclose his further names in parentheses, as

Bell (Aubrey F. G.)

or with a comma and full stop, as

Bell, Aubrey F. G.

There is no reason for advocating the adoption of one of these styles more than the other, especially in these days of type-setting machines. Where[Pg 35] hand composition is still in use, and particularly in small printing offices, the use of a large number of parentheses ( ) causes "a run on sorts," that is, the supply wanted is greater than is ordinarily found with a fount of jobbing type. Nowadays, it being merely a question of taste, and not one of expediency, it matters less, and as my personal preference is for the use of the comma and point, that style is used in the examples given throughout this book. The form decided upon must be adhered to if only to ensure uniform appearance—certainly both forms should not be found in one catalogue. Attention to details of this kind is the essence of good work, and after a time cataloguers, becoming accustomed to a particular style, fall, as a matter of course, into its use quite readily.

The surname is followed, as shown, by the Christian or forenames, but we are often confronted with the necessity for deciding how much of these forenames shall go in—shall they be given as on the title-page, or shall we find out the full names covered by the initials, or will initials alone suffice? In some catalogues the full names are given, in others only the initials, and in a few rare instances of "index-entry" catalogues the surname alone. For an average catalogue to give the name in its fullest possible form is more than is required, and is wasteful of space, while the bare initials do not enable us to discern whether the author is a man or a woman. It is more helpful to give the first or other important forename, and to do so does not lengthen the catalogue to any appreciable extent. The danger of this omission is exemplified at the end of this chapter.

In the catalogues of large libraries it is often necessary to take the trouble to get all names as fully and correctly as possible, otherwise, owing to the likelihood of numerous entries under persons with the same surnames, errors may result if the authors are not distinguished from one another in this way. This does not imply that the cataloguer of a collection of books up to 100,000 volumes need go to the trouble of giving every name in full as if he were compiling a biographical dictionary; nor need he add the dates of the author's birth and death to the name, as is sometimes done, because the labour will be unappreciated, and be wasted. Such dates, however, have at times to be given to distinguish between authors whose names are alike.

It is a wise plan, in any case, to limit the forenames or initials to those used by an author on his books at any time during his career. For all reasonable purposes, or any purpose, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, for example, is sufficient, though his name was properly Gabriel Charles Dante Rossetti, Charles Dickens, instead of Charles John Huffam Dickens, will not be mistaken for any other of the name, and Joaquin Miller will serve better than Cincinnatus Heine Miller.

A few instances taken from recent books by well-known authors will show how difficulties may arise in this connection. George Bernard Shaw's "Man and Superman" according to the title-page is "by Bernard Shaw," whereas his "The quintessence of Ibsenism" is "by G. Bernard Shaw." Martin Hume's work on "The love affairs of Mary, Queen of Scots" is given as "by Martin Hume," but his "Spain: its greatness and decay" is "by Martin[Pg 37] A. S. Hume." There is the "Life of Gladstone" "by Herbert Woodfield Paul," a book "Men and letters" "by Herbert Paul," and "Matthew Arnold" (in the "English Men of Letters" series), "by Herbert W. Paul." Then we have the case of the well-known writer on animal life who changed his name recently on his books from Ernest Seton Thompson to Ernest Thompson Seton. This leads the unwary cataloguer into the mistake of getting books by the same author under different names. It must be confessed that the risk is not great where such well-known writers are concerned, but if they should be unknown authors of a past age or another country, the cataloguer would probably not be so well-informed, and fall into error. To cite an instance of this, the French author, Louis Jacques Napoleon Bertrand, we are told, took the name of Ludovic Bertrand, and later substituted Aloysius for Ludovic, the wonder being that he did not change the Bertrand also. There is need to be constantly on the alert for those who have no fixity of name. The only little satisfaction the cataloguer has if he finds he has tripped is that few will have sufficient knowledge to discover his fault.

Besides the catalogues of important libraries, the following may be named as among the more useful works of reference for working out the names of authors and other personages:—

Phillips, Lawrence B. The dictionary of biographical

reference. 1871 and later reprints.

Stephen, Sir Leslie, and Sir Sidney Lee (Eds.)

The dictionary of national biography; with

[Pg 38]the supplements. 1885-1912.

Allibone, S. A. Critical dictionary of English

literature and British and American authors;

with supplement of J. F. Kirk. 1885-91.

Smith, B. E. (Ed.) The Century cyclopedia of

names. 1894.

Auge, Claude (Ed.) Nouveau Larousse illustré;

avec supplement.

Biographie universelle, ancienne et moderne. 1811-28.

Nouvelle biographie générale. 1852-66.

Allgemeine deutsche Biographie. 1875-1908.

Appleton's Cyclopædia of American biography.

1888-89.

The New York State University Library Bulletin, Bibliography, No. 5, issued in 1898 at the price of 3d., consists of "A selection of Reference Books for the use of Cataloguers in finding Full Names."

To revert to the book we are dealing with. As the author gives his first Christian name in full and two initials for the others we may regard it as quite full enough for any style of catalogue, and adding the title of the book, the entry becomes

Bell, Aubrey F. G.

In Portugal.

The quotation on the title-page, with its translation, is ignored altogether, as would be anything of a similar nature, such as a motto; these are merely adornments of the title-page, and have no bearing whatever upon the book from the cataloguer's standpoint. If it were intended to be very exact the omission could be indicated by three dots (...) but the need for doing this only applies in the case of rare or special editions.

We have now got the first two parts of our catalogue entry, and in the order from which there[Pg 39] can be no deviation. Our next step is to decide how much further information is to be given. A catalogue of a library has been defined as a list of the titles of books which it contains, and that it (the catalogue) must not be expected to give any further description of a book than the author gives, or ought to give, on the title-page, and the publisher in the imprint, or colophon.

The catalogue can be made to give, besides the titles of books, such descriptions, more or less extended, drawn from all available sources of information, as may be necessary to furnish means of identifying each work, of distinguishing its different editions, of ascertaining the requisites of a perfect copy, of learning all facts of interest respecting its authorship, publication, typography, subsequent causalities, alterations, etc., its market value, and the estimation in which it is held.

For our entry we shall adopt the happy mean between these two and add to this entry, because it is the principal one, the information contained in the "imprint" at the foot of the title-page, giving the place of publication, the publisher's (or printer's) name, and the date of publication. In the early days of printing this information was given at the end of a book, and termed the "colophon." We shall also give the information spoken of as "the collation," consisting of a statement of the number of pages in the book, whether it is illustrated, and how, by maps, portraits, or otherwise, and even if the illustrations are in colour.

The first-named place of publication on the title-page of the book is London. In the catalogues of British libraries it is a recognised custom to omit[Pg 40] naming the place of publication when a book is unmistakably published in London, this being taken as understood, all other places being given. Except in booksellers' lists and similar catalogues, the name of the publisher may also be left out, though it is often given in the full form of library catalogues. In the case of this book, the name of the second place, New York, is merely supplemental, the book being printed as well as published in this country. The date of publication must always be given, and in every entry (with the single exception of works of fiction, referred to later), not in Roman numerals, however, but in Arabic.

When books are in a number of volumes, the earliest and latest dates are given. These dates are not necessarily those of the first and last volumes, as the volumes may not have appeared in regular sequence, or a set may be made up from editions of varying dates.

For "the collation" we carefully examine the book and find that it has eight pages of prefatory matter marked with Roman numerals (i.—viii.), and the body of the work contains 227, paged in Arabic. This is shown as pp. viii. + 227, or as pp. viii., 227. The book has no map or illustrations. The enumeration of the pages in this way, it may be said, conveys no very exact idea of the extent of the work, as, of course, large type requires many more pages than small. Even the thickness of the book is not indicated by stating the number of pages, as an India-paper edition will contain just the same number of pages as one on thick paper. For these and other reasons, such information can be omitted if economy of space is of any conse[Pg 41]quence. If a book is in more than one volume it is unusual to give the number of pages, though it is sometimes done in publishers' lists. A "book" is invariably understood to mean a complete work, whether in one or many volumes.

The size of the book may also be given, and will occasionally prove useful, while completing the entry. The book we are dealing with is octavo in size, coming between the sizes known as "crown" and "demy," but as these terms convey no special idea to the uninformed in book sizes, and, indeed, no very definite idea to those who are, it will suffice for most purposes to call the book 8o (octavo) unless the height is given instead in inches or in centimetres, as 8¼in. or 21cm. For most catalogues it will be found sufficient to give the sizes when they exceed octavo, it being understood that all books are of that size, or less, unless the contrary is indicated by the signs 4o(quarto) or fo (folio).

The entry completed upon these lines becomes

Bell, Aubrey F. G.

In Portugal. London and New York, John

Lane, 1912. pp. viii., 227. 8o

The information to be given, when tabulated, falls into this order

Numbers 4, 5, 6, 12, and 13 are not required or given in the above entry, but are here inserted to make the table complete. With the exception of numbers 1 to 4, this order may be varied at will, but only at the outset, as whatever order is decided upon must afterwards be adhered to. The following statement of the order given in some of the rules is of interest in this connection, and will be helpful:—

British Museum order under its Rules (3, 16-22):

1, Author. 2, Title. 3, Edition. 4, Number of parts or volumes or numbered pages if a single volume. 5, Place of printing or publication and printer's name (if necessary). 6, Date. 7, Size. 8, Press mark. 9, Note, if required.

Cutter's Rules:

1, Author. 2, Title. 3, Edition. 4, Place of publication. 5, Publisher's name. 6, Date. 7, Number of volumes or number of pages, illustrations, etc. 8, Size. 9, Notes of contents.

Library Association and American Library Association Rules:

1, Author. 2, Title. 3, Additions to title, if any. 4, Edition. 5, Place of publication. 6, Publisher's name. 7, Place of printing, if given. 8, Date. 9, Volumes or pages, illustrations, etc. 10, Size. 11, Series. 12, Contents and notes.

For most libraries the information can be satisfactorily curtailed and limited to the following:—

1, Author. 2, Title. 3, Edition. 4, Date. 5, Press mark. 6, Contents or annotations. To these may be added, between 3 and 4, an abbreviation telling if the book is illustrated, as "illus.", instead of giving the collation in full.

The reduced entry for our book accordingly becomes

Bell, Aubrey F. G.

In Portugal. 1912

Having the author or principal entry complete, we now proceed to examine the book for subject-entry, and find that it consists of descriptions of journeys to places off the beaten track in Portugal. Even with the title of the book so obvious and the subject so clearly named in it, it is wise not to take it for granted, and examine the book as it may contain something of value belonging to another subject—for example, there is a book of travel in the Near East bearing the title "Pen and pencil in Asia Minor" which contains no less than thirteen chapters upon silkworms and the silk industry, not only in the Levant, but in France and elsewhere—quite a respectable book within a book, but this the title-page fails to reveal. The subject of our book, however, is open to no doubt, and for the dictionary catalogue the subject-entry is

Portugal:

Bell, A. F. G. In Portugal. 1912

No further entries are called for than these two (author and subject).

In all entries subordinate to the main entry, where the fullest particulars concerning the book are given, the information is condensed sufficiently to identify the book upon the supposition that those who require more details will turn to the main entry for them. The omissions from the subordinate entries are the full Christian names of authors (initials alone being given), the names of editors, translators, or illustrators, the names of series, the collations, sizes, and places of publication. The entries used throughout this work demonstrate this. The dates of publications are invariably given in all entries except where shown.

It has been contended that all details are as much wanted under the subject as under the author. There is much to be said in favour of this, but it is impossible to make every entry a main-entry when expense and the size of the catalogue have to be considered.

When the time comes for preparing the manuscript of the catalogue for the press, should it happen that there was no other book upon the subject, then the form of entry can be changed to what may be called a subject-title-entry, thus

Portugal, In. Bell, A. F. G. 1912

upon the principle that a "heading" is not required unless there are two or more books to go under it. By the reverse process, if there should be two or more title-entries of books unquestionably upon the same subject then these are converted into entries under a single subject-heading. If the two entries were

Portugal, In. Bell, A. F. G. 1912

Portugal, Sunshine and storm in. Watson, G. 1904

they are changed to

Portugal:

Bell, A. F. G. In Portugal. 1912

Watson, G. Sunshine and storm in Portugal. 1904

It is possible further to economise these entries:

Portugal:

Bell, A. F. G. In P. 1912

Watson, G. Sunshine, etc. in P. 1904

This style was adopted in quite good catalogues, and there is no particular loss of information through it, though the gain of space hardly compensates for the want of clearness, to say nothing of the somewhat bald appearance of the entries.

In all the subject-entries above it will be observed that the author's surname leads, the reason for this being that it serves to guide to the name under which the main-entry is to be found. The books are also arranged in alphabetical order by these surnames under the subject-heading.

If the catalogue we are compiling is not dictionary but classified in its arrangement, then, as already stated, there is but one entry (other than the brief index entries), and that the main-entry. Upon this is marked the numerical symbols of the classification adopted, which we shall presume throughout is the best-known and most used, Dewey's Decimal Classification. For convenience in sorting, the numbers are better written on the top right-hand of the slip or card. Our entry is marked accordingly

914.69

Bell, Aubrey F. G. In Portugal. London and

New York, John Lane, 1912. pp. viii., 227. 8o

This entry can be curtailed if considered desirable, as shown above for the dictionary catalogue.

As some persons may not have used the Dewey Classification, it may be explained that these numerical symbols signify

| 900 | History (the General Class). |

| 910 | Geography and Travels. |

| 914 | Europe. |

| 914.6 | Spain (the Iberian Peninsula). |

| 914.69 | Portugal. |

Brief entries are needed for the author and subject-index or indexes, which appear at either the end or beginning of the catalogue when printed, thus

Bell, A. F. G. In Portugal. 914.69

Portugal (Travels). 914.69

In the following pages all the examples given to illustrate the various points which arise in the cataloguing of books are worked out in full for both the dictionary and classified catalogues, in order to show the whole method of treatment, as well as to prevent the misunderstanding which arose upon explanations given only by way of suggestion, and not as completed examples, in my former book upon this subject.

To show how difficult it is for experienced cataloguers to avoid error and the pitfalls in their way, it may be mentioned that several otherwise good catalogues have these two books

Here and there in Italy and over the border, by

Linda Villari. 1893

Italian life in town and country, by L. Villari. 1902

entered as

Villari, Linda. Here and there in Italy. 1893

— Italian life in town and country. 1902

though the latter book is by Luigi Villari. With nothing in either book to show this, the presumption that both books are by the same author is excusable, the initials of the authors' names and the subject being alike, yet it proves that it does not do to jump to conclusions. Correctly catalogued, the entries are

Villari, Linda. Here and there in Italy and over

the border. pp. viii., 269. 1893

Villari, Luigi. Italian life in town and country.

(Our neighbours.) pp. xii., 261, illus. 1902

and the subject-entries are

Italy.

Villari, L. Here and there in Italy. 1893

Villari, L. Italian life in town and country. 1902

Both entries will be marked 914.5 for the classified catalogue (History—Geography and Travels—Europe—Italy), and the index entries will be

Villari, Linda. Here and there in Italy. 914.5

Villari, Luigi. Italian life. 914.5

Italy (Travel). 914.5

Joint-Authors. Collations. Synonymous Subject-Headings. Participants in a Correspondence. References. Man and Wife as Joint-Authors.

When a book is written by two authors, the entry is given under the first-named on the title-page. The following is an illustration of the method of treatment in such a case, and in order to make the matter clear, the title-page is set out in full as before. The whole title is printed in capital letters, and has no other punctuation than that shown.

Upon the lines already laid down, the main-entry becomes

Ely, Richard T., and George Ray Wicker.

Elementary principles of economics; together

with a short sketch of economic history. New

York, Macmillan Co., 1910. pp. xii., 388

Frequently the names of the authors are seen rendered in this fashion

Ely, Richard T., and Wicker, George Ray

While it is essential and unavoidable that the name of the first author should be turned about to get his surname as the leading word, yet there is no object in twisting about the second author's name in like manner, as it is not so required, therefore the ordinary reading of the name is better and simpler, as given in the first entry.

Unless needed to distinguish between different authors of the same name, the academical degrees are omitted, as well as any statement concerning the professorships held by these authors, although the fact that they hold such offices goes to prove their qualifications for dealing with this subject. If it were desired to direct attention to this, it could be done by means of a note or annotation to the entry, after this manner

The first author is Prof. of Pol. Econ., Wisconsin Univ., and the second Asst. Prof. of Economics, Dartmouth Coll.

The share of the second author in the book needs to be recognised, and this is accomplished by means of a reference, as

Wicker, George Ray (Joint-Author.) See Ely,

Richard T.

If this writer happens to be the sole author of another work, then the form of reference is made to read

Wicker, George Ray.

— (Joint-Author). See also Ely, Richard T.

To give the reference in this form may seem to be a contradiction of the previous statement that the second author's name need not be turned about, but in this case it is necessary to point directly to the name Ely under which the entry is found.

An alternative style for both the above references so far as the use of capitals and punctuation is concerned is

Wicker, Geo. Ray (joint-author) see Ely,

Richard T.

Wicker, Geo. Ray.

— (joint-author) see also Ely, Richard T.

It must be borne in mind that whatever style is adopted should be strictly followed throughout.