TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE:

—Obvious print and punctuation errors were corrected.

”ANY THING GOING ON TO-NIGHT?” VAN CLEEF ASKED THE POLICE SERGEANT. (Page 44.)

UNDER ORDERS

THE STORY OF A YOUNG REPORTER

BY

KIRK MUNROE

AUTHOR OF “THE FLAMINGO FEATHER,” “DERRICK STERLING,”

“DORYMATES,” “CAMPMATES,” ETC., ETC.

ILLUSTRATED

G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

| NEW YORK 27 WEST TWENTY-THIRD ST. |

LONDON 27 KING WILLIAM ST., STRAND |

The Knickerbocker Press

1890

Copyrighted, 1890

by

KIRK MUNROE

The Knickerbocker Press, New York

Electrotyped, Printed, and Bound by

G. P. Putnam’s Sons

TO JOHN BOGART

FOR MANY YEARS CITY EDITOR OF THE NEW YORK “SUN”

who, more than any other, helped me to obtain a literary foothold, whose honesty of

purpose, strict sense of justice, and unswerving fidelity to duty uplifted

him as an example of the ideal city editor, the dedication of

this story of newspaper life is offered as a tribute

of gratitude and affection by

The Author

CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I.— | The Captain of the Crew Resigns | 1 |

| II.— | Trying to Become a Reporter | 16 |

| III.— | The Old Gentleman of the Oxygen | 32 |

| IV.— | Beginning a New Life | 49 |

| V.— | The Kind of a Fellow Billings Was | 66 |

| VI.— | A Reporter at Home | 81 |

| VII.— | “No Loafers nor Reporters Admitted” | 96 |

| VIII.— | ”Lord Steerem,” the Coxswain | 111 |

| IX.— | An Act of Folly and a Cruel Dispatch | 125 |

| X.— | Myles Makes a Startling Discovery | 141 |

| XI.— | A Fight and a Mistake | 157 |

| XII.— | Myles Falls into a Trap | 172 |

| XIII.— | The Strikers Capture a Train | 186 |

| XIV.— | A Race against Time | 199 |

| XV.— | The 50th Regiment, N. G. S. N. Y. | 214 |

| XVI.— | Recalled and Dismissed | 229 |

| XVII.— | The Best Sister in the World | 243 |

| XVIII.— | Who Robbed the Safe? | 260 |

| XIX.— | Reinstated and Arrested | 277 |

| XX.— | Collecting Evidence for the Defence | 294 |

| XXI.— | A Day of Trial | 311 |

| XXII.— | Triumphantly Acquitted | 329 |

ILLUSTRATIONS.

| PAGE | |

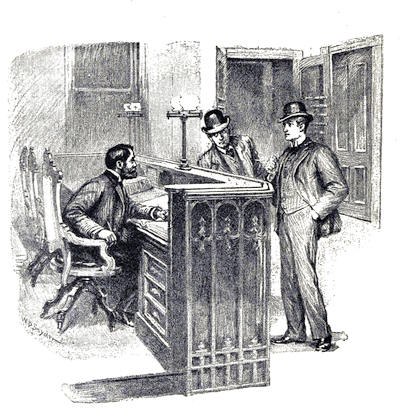

| “ANY THING GOING ON TO-NIGHT?” VAN CLEEF ASKED THE POLICE SERGEANT | Frontispiece |

| “IF YOU MUST GO TO WORK AT ONCE, WHY NOT TRY JOURNALISM?” | 14 |

| VAN CLEEF SAID SOMETHING TO THE CITY EDITOR IN A LOW TONE | 30 |

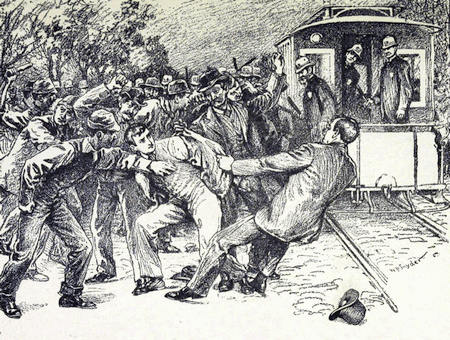

| A HOARSE VOICE SHOUTED THE OMINOUS WORD “SPOTTER” | 68 |

| “I DON’T SEE HOW WE CAN BREAK THROUGH THAT RULE, EVEN IN YOUR CASE” | 96 |

| AS HE WAS STOOPING TO SET FIRE TO THE READY FUEL, THE SOUND OF HIS OWN NAME CAUSED HIM TO DROP THE MATCH | 150 |

| THE STRIKERS REORGANIZING THE MILITIA | 192 |

| THE CAR PLUNGED FORWARD, TURNED COMPLETELY OVER, AND CRUSHED POOR MYLES BENEATH IT | 212 |

| THE NEXT MOMENT HE FOUND HIMSELF STANDING ON THE PLATFORM BESIDE THE COLONEL | 226 |

| HE LEANED GLOOMILY AGAINST THE MANTEL SHELF THAT NEARLY FILLED ONE SIDE OF THE ROOM | 248 |

| “WHO ARE YOU?” SAID BILL, HOLDING ON TO TIGE WITH ALL HIS MIGHT | 310 |

| “IT’S ALL RIGHT, OLD MAN. YOUR SPACE HAS BEEN MEASURED, AND THE FULL BILL IS ALLOWED” | 342 |

UNDER ORDERS.

CHAPTER I.

THE CAPTAIN OF THE CREW RESIGNS.

“THE situation certainly looks desperate, Anna,” said Mr. Manning, with a deep sigh, as he turned wearily on his couch and reached out a thin white hand that was immediately clasped between the plump ones of his cheery-faced wife. Her face did not look so very cheery just at this moment, however, for lines of anxiety were wrinkling her forehead and her eyes were full of tears. Then, too, she was thinking so hard that her mouth was all puckered up.

“Yes, it does look a little desperate,” she admitted; “but, bless you! it has looked desperate plenty of times before, and we have always come out all right somehow. God has been too good to us so far to desert us now, and I, for one, am willing to trust him to the end.”

“Well, dear,” answered her husband, “if you are, I ought to be, for the heaviest part of the burden must fall on you.”

The Mannings lived in a pleasant, old-fashioned New Jersey village a few miles out of New York, and had, until recently, been in the most comfortable circumstances. Mr. Manning was the manager of a large manufacturing business and received a handsome salary, from which he should have laid by a snug sum against a “rainy day.” He knew it was his duty to do this; but each year brought some new expense that seemed as if it ought to be met, and each year he said to himself:

“Well, I can’t do any thing about it this time, that’s certain; but next year I must surely begin to lay something aside.”

So year after year passed, until finally, when Myles Manning, the only son of the family, was ready to enter college, the annual expenses were found to be in excess of the handsome annual income, and nothing had been saved.

Alarmed at this state of affairs, and not prepared just then to retrench or practise an economy that would make them seem poor in the eyes of their[3] neighbors, Mr. Manning mortgaged their beautiful home. His wife at first refused to sign the necessary papers, but was at last persuaded into doing so.

It was only to raise enough money to see Myles properly through college. Then he would go into business and soon be in a position to help them, said Mr. Manning. He also said there was nothing in the world like college for a young man. Besides the education that it gave him, he made friends in college that were friends for life and always ready to help one another. Every thing depended, though, upon the set he got into. It must be the very best in the college, to be worth any thing at all. To keep up with that set in X—— College would cost something, and unless they mortgaged the place he really did not see how he was to raise the necessary money. They surely could not do less for their only son than to send him handsomely through college, and, after all, it would in the end prove one of the very best investments they could make.

So Mrs. Manning was persuaded, the mortgage was signed, and Myles went to X—— College. There, on account of his good looks, his generous disposition, his unfailing good-nature, and his apparent[4] command of ready money, he speedily became the most popular man of his class, and a leader in its “very best set,” by which was meant the wealthiest and most extravagant lot of young fellows in it.

At the time this story opens he had nearly finished his third year of college life, and was looking forward with joyful anticipations to being soon that proudest, and, in his own estimation, most important of mortals—a senior. He was captain of the university crew, which was in steady training for the great annual race with the Z—— College crew at New London. He was also the best all-around athlete of his college. This, according to Ben Watkins, who had been his rival for the captaincy of the crew, and was almost the only fellow in his class who disliked Myles, was not surprising. He said that Manning did nothing else besides row and practise in the gymnasium. This was not true; for, although Myles did not rank very high at examinations, he still studied enough to enable him to pass with a fair average of marks. He had, moreover, determined upon a career which it seemed to him would not require a very profound scholarship. It was that of a politician; and he felt quite sure that[5] the influence of his own father, or that of some of his gay young college friends, would secure him some snug political position as soon as he was graduated.

Thus far, therefore, life had gone easily and prosperously with this light-hearted young fellow, and its future looked bright before him. He knew nothing of its ruder aspects—of its despair, its hunger, and its poverty. There were those who said of him that, while he was a good fair-weather sailor, he was not of the stuff to face, and do brave battle with, the storms of adversity, should they ever overtake him.

Now, just such a storm had overtaken Myles Manning, and he was to be tried. Nearly a year before a trouble of the eyes with which Mr. Manning was afflicted had suddenly resulted in total blindness. It was at first supposed to be only temporary, but as time wore on, and one painful operation after another failed to afford relief, hope began to yield to despair, and his career of usefulness seemed ended. Thus far his salary had been continued, and the affairs of the Manning family had gone on much as usual. At last there came a letter in which, while regretting the necessity, the president of the company that had employed[6] Mr. Manning informed him that, as there was no present prospect that he would be able to resume his duties, the payment of his salary must cease from that date.

As Mrs. Manning finished reading this politely cruel letter to her husband she tried to speak cheerfully of it, and to find some gleam of hope in their situation. In her heart, however, she was compelled to admit that it was indeed desperate, and that she did not know which way to turn.

It was Saturday, and Kate Manning, the only daughter of the family, and a year younger than Myles, was home from Vassar, the summer vacation at which was already begun. The evening before, she and her mother planned a trip to a noted sea-side resort, at which they hoped Mr. Manning might be benefited, and where Kate, who was as fond of society as her brother, and in her way quite as popular as he, anticipated a delightful time. Myles had written that he expected an invitation to go on a yachting trip with Bert Smedley, one of the wealthiest of his classmates. Thus he too might be looked for at the same famous resort. He was to come home for Sunday to talk over plans for the summer.

Myles was never in better spirits, nor more full of enthusiasm over what he was doing, and about to do, than when he reached home that Saturday evening. After he had kissed his mother and sister, and been warned by them not to be boisterous, as his father was sleeping, they could do nothing for some time but sit and listen to his glowing accounts of college life and the joys of which it held so many for him.

At last he noticed their mood, and, stopping short in the middle of a glowing description of his crew and the splendid work it was doing, he asked:

“But what ails you two? You are as mum as oysters.”

Then the mother crossed over to the sofa on which he sat, and, taking one of his hands in hers, said:

“My poor dear boy! It is so good to see you bright and happy that we hadn’t the heart to interrupt you with our sorrows.”

“Sorrows!” exclaimed Myles, in a bewildered tone. “What do you mean, mother? Is any one dead? or is father worse?”

Then they told him the whole story; of the letter that had come that day, of the mortgage, with its ever accumulating load of interest, and[8] of the desperate financial condition of the family generally.

When the sad tale was ended the boy sat for a moment as motionless as though stunned. Then in a husky voice he asked:

“Is that all, mother?”

“No, dear, it is not,” answered the brave little woman. “Kate and I have been looking at the situation in every possible light this afternoon, and have finally decided upon a plan in which we want your help. It is to rent this house furnished, and with every thing belonging to it, except the gardener’s cottage. Into that we will move, and there we can manage to live very comfortably. Of course all the servants will be dismissed, and Kate is going to give up Vassar in order to stay at home and help me with the housework. In this way we hope to be able to pay the interest on the mortgage until there is a good chance to sell the property, when we shall be relieved of that burden. You have but one more year of college. By practising the closest economy all around—and this is where you can help us,—we think we can get you through with that. Then you will find some business and aid in supporting the[9] family. Thus we shall have only one year of real hard times, and that will soon be over with.”

“Mother!” exclaimed the boy, giving a squeeze to the soft little hand clasped in his big brown ones; “you are the very best and bravest woman in the world. And, Kate, you are a dear, splendid girl. But do you suppose for one minute that I am going to let you two do all this for me and do nothing for myself? No, sir-e-e! If Kate must give up her college, in which I know she is doing a thousand times better than I am in mine, why, I shall do the same. I shall do it on Monday too. College isn’t worth half so much in this world as home is, and where there is going to be a fight to keep that, I’m going to be one of the fighters. Now don’t say a word against it; I know the right thing to do, and I’m going to do it.”

Nothing they could say served to alter his determination in the slightest. He only added to his arguments that he was not giving up so very much after all, for it wouldn’t be much fun to stay in college after he was no longer able to hold up his end. Into his mind came also unpleasant memories of a few little bills that even his generous allowance had[10] not been sufficient to meet; but of these he said nothing. He felt that they were his private burden and must be borne alone.

In spite of their remonstrances against his decision to leave college, both Mrs. Manning and Kate were greatly cheered by his manly resolution and brave words. As they listened to them their hearts grew many degrees lighter than they had been before his arrival.

When the boy told his father of his plans, the next day, Mr. Manning heartily approved of them. He only asked his son what steps he proposed to take to get into business.

“My influence might be sufficient to secure you some sort of a position with the M—— Company,” he added, naming the one for which he had acted as manager.

“No, sir!” exclaimed Myles. “Any thing rather than that. I’d sell papers on the street sooner than work under the man who wrote you that letter. Don’t you worry, sir. I’ll find a place quick enough. There are lots of fellows in my class who are the sons of business men, and who would be glad to give me notes to their fathers.[11] Some of them are sure to take me in and give me a start.”

The father sighed as he thought of the difference between friends in prosperity and friends in adversity; but he would not say any thing to dampen his boy’s ardor.

“Let him work out his own salvation,” said the blind man to his wife. “The harder the fight the more highly will he prize the victory when it is won, as I am certain it will be sooner or later. I am afraid, though, that it will be a long time before he is able to afford you any real assistance. If he supports himself for the first year or two he will be doing unusually well.”

When Myles and his sister went to church together that Sunday morning many an admiring glance was cast at the stalwart young captain of the X—— College “Varsity” crew, and more than one pretty girl privately decided to wear X—— colors on the day of the great race.

On Monday, when his mother and Kate kissed him good-bye, tears stood in their eyes, and the former said:

“Oh, Myles, think again, and seriously before you[12] take this step. We can manage somehow to keep you in college for one little year more; I know we can.”

“Of course you could, mother. You could do any thing that you set out to do, only I won’t be kept,” answered the boy, bravely. “The next thing you hear of me will be that I am a junior partner in some Wall Street concern; see if I am not.”

The first person Myles met upon entering the college-grounds was Bert Smedley, who held out a paper to him, saying:

“You are just the one I was looking for, Manning. We have got to raise a hundred or two more to see you fellows through at New London, and our set has undertaken to do it. Here’s the subscription paper, and I wouldn’t let a fellow sign it until I’d got your name to head the list. So, now, give us something handsome as a starter.”

Myles’ heart sank at these words, and there was a choking sensation in his throat as he answered:

“There’s no use coming to me, Bert, I can’t give a cent. You see, my father has got into trouble, and I’ve got to leave college and go to work to help him out of it. If you will only speak a word for me[13] to your father, though, and ask if he can’t find me some sort of a berth in his business, whatever that is, for I don’t think I ever heard you say, I’ll be ever so much obliged to you, and will do as much and more for you if ever I have a chance.”

“But you are captain of the crew!” gasped Smedley, bewildered by this sudden turn of affairs.

“No, I’m not, now,” answered Myles. “My resignation is already written and sent in. It was hard enough to give it up, you’d better believe; but it had to be done—and business before pleasure, you know. You’ll speak a good word for me, old man, won’t you?”

“I’ll see,” replied the other. Then adding, “Excuse me a moment; there’s Watkins, and I must have his name,” he hurried away, anxious to be the first to communicate the astounding intelligence he had just learned to Myles’ most prominent rival.

The news flew fast, and Myles had hardly begun to dismantle his room of its many pretty bits of bric-a-brac, preparatory to packing up his belongings, before it was filled with a throng of fellows anxious to hear from his own lips the truth of the startling rumor.

“It’s a shame!” cried one.

“It will break up the crew!” exclaimed another.

“We might as well give the race to Z—— and be done with it.”

But their thoughts seemed to be mostly of their own disappointment. Poor Myles, almost stunned by the clamor about him, could hardly hear the words of pity for himself, and sympathy with his misfortune, that were uttered here and there. It seemed to him that they cared nothing for him or his troubles, but thought only of what a loss he would be to the crew. Thus thinking he could not bring himself to ask their help in securing employment, as he had intended; and, though they were the fellows of his “set,” upon whom he depended for aid, he let one after another of them leave the room without broaching the subject. At length the room was cleared and he was left alone.

Not quite alone though. A fellow named Van Cleef, whom Myles knew but slightly, and who was such a hard-working student as to be termed the class “dig,” remained. As Myles turned and noticed him for the first time Van Cleef said:

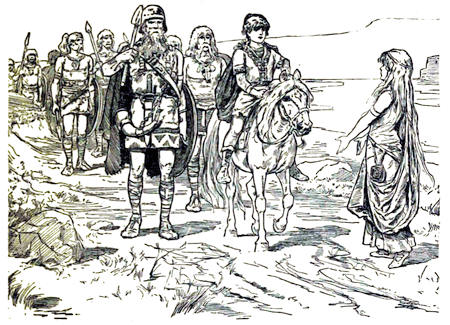

“IF YOU MUST GO TO WORK AT ONCE, WHY NOT TRY JOURNALISM?” (Page 15.)

“I’m awfully sorry for you, Manning, and you are heartily welcome to any thing I can do to help you. If you must go to work at once why not try journalism? It is hard work, but it pays something from the very start, and that is more than can be said of almost any other business.”

CHAPTER II.

TRYING TO BECOME A REPORTER.

“JOURNALISM!” exclaimed Myles Manning, in answer to Van Cleef’s suggestion. “Why, I never thought of such a thing, and I don’t know the first thing about it. To be sure,” he added, reflectively, “I have helped edit the college Oarsman, and have written one or two little things that got published in our country weekly out home; but I don’t suppose all that would help a fellow much in real journalism.”

Here Myles looked up at his companion, hoping to hear him say that these things would go far toward securing him a position on one of the big dailies. But Van Cleef was too honest a fellow to raise false hopes in another, and he said:

“No; of course all that doesn’t amount to any thing. Everybody does more or less of that sort of thing nowadays, and it’s generally in[17] the poetry line; but there’s nothing practical in it.”

Here Myles blushed consciously as he recalled the fact that most of his own efforts had been in the “poetry line”; but he said nothing.

“At any rate,” continued Van Cleef, “you probably know as much of journalism as you do of Wall Street or any other business, and that is just nothing at all. You’d have to begin at the very bottom, any way, and work up. Now, reporting is the only thing I know of that pays a fellow living wages from the very first, and that is the reason I mentioned it.”

“Reporting!” echoed Myles, pausing in his packing and looking up with an expression of amazement. “You don’t mean to say that your ‘journalism’ means being only a common reporter?”

Now, in Myles’ set reporters were always spoken of, when mentioned at all, as a class of beings to be despised. He had come to regard them as a lot of very common fellows, who spent their time in prying into other people’s business, who were to be avoided as much as possible, but who must be treated decently when met, for fear lest they might “write a fellow up,” or put his name in the papers in some[18] unpleasant connection. When Van Cleef mentioned journalism his hearer’s fancy at once sprang into the position of an editorial writer, a well-paid contributor of graceful verse or witty paragraphs, a critic, foreign correspondent, or something of that sort. But to be only a reporter! Why, the mere thought of such a thing was humiliating.

“Why not?” asked Van Cleef, in reply to Myles’ question, and in surprise at his tone. “A first-class, well-trained, reporter is one of the brightest, smartest, and best-informed men in the city. He knows everybody worth knowing, and every thing that is happening or about to happen. He is as valuable to his paper as the editor-in-chief, and he often earns as much money. A reporter must of necessity learn something of every kind of business, and he meets with more chances than any other man to change his employment, if he wants to, for one that will pay him better.

“Look at the prominent politicians, railroad presidents, and others now occupying the most honorable positions of trust and power in this country, and see how many of them began life as reporters. Our present Secretary of State was once a reporter,[19] and a good one too. The President’s private secretary, who is called the ‘power behind the throne,’ was a reporter. A late Secretary of the Treasury was once a reporter. I have a personal knowledge of six members of Congress who used to be reporters. All the foreign correspondents, who are really the men controlling the destinies of nations, are nothing more nor less than reporters. Stanley was a reporter, and so were hundreds more who are now world-famed. Oh, I tell you what, Manning, there is nothing to be ashamed of in being a reporter, though I will admit that most people seem to think there is.

“Of course, there are a lot of sneaks and worthless fellows in this business, as in every other, but they are decidedly in the minority, and are fast being weeded out. The newspapers now demand the very best men as reporters, and they are getting them, too. You have heard, of course, of the professorship of journalism at C—— College? Well, it was established by a man who, only a few years ago, was a reporter on one of the New York papers, and he is making a first-class thing of it. I am a sort of a reporter myself,” he continued, laughing, “and the[20] minute I graduate from here I mean to become a full-fledged one.”

“You a reporter!” cried Myles. “How can you be a reporter and a college man at the same time?”

“Easy enough, or rather by working hard and sacrificing some sleep,” answered Van Cleef. “You see,” he continued, in a slightly embarrassed tone, for he was not given to talking of himself or his own affairs, “I am not one of you wealthy fellows, but have had to hoe my own row ever since I was fifteen. When I came here to enter college I had to find something to do to support myself at the same time. After a lot of disappointments I was fortunate enough to obtain a night-station job on the Phonograph, and, though the pay is small, it is enough to keep me going.”

“What do you mean by a ‘night-station’ job?” asked Myles, now greatly interested in what Van Cleef was saying.

“Why,” laughed the other, “it means that I go at ten o’clock every evening to the police-station nearest Central Park, on either the east or the west side of the city, and walk from there down to the Battery. On the way I stop at every station and at the[21] hospitals to inquire for stray bits of news or interesting incidents. As the route lies through the very lowest and worst parts of town one is also apt to run across something or other of interest that even the police have not found out. I have to be all through and report at the office at sharp one o’clock.”

“I should think that would be fun,” said Myles; “and I should like mightily to take the trip with you some night.”

“I should only be too glad of your company,” returned the other, “and perhaps you would enjoy it for once. I can tell you though, it gets to be awfully monotonous after you have done it for a year or so, and I shall be happy enough to give it up for regular reporting when the time comes that I can do so.”

“Aren’t you in great danger, walking alone so late at night through the slums?” asked Myles.

“Oh, no—that is, not to speak of. A reporter, if he is known to be such, is generally safe enough wherever he goes, and I am pretty well known by this time along the entire line of my route.”

“You carry a pistol, of course?”

“Indeed I do nothing so foolish,” answered Van Cleef. “It would be certain to get me into trouble sooner or later. I only carry this badge, and it affords a better protection than all the pistols I could stuff into my pockets.”

Here the speaker threw open his coat and displayed the silver badge of a deputy sheriff pinned to his vest.

“Yes, I have been regularly sworn in,” he continued, in answer to Myles’ inquiring glance, “and the sight of it acts like magic in quieting a crowd of toughs. It passes me through fire-lines, too, which is often a great convenience.”

“What do you do in vacations?” asked Myles, with the curiosity of one exploring a new world of experience, the very existence of which he had not heretofore dreamed of.

“Do my station-work nights, and in the daytime read law or study English literature in the library,” answered Van Cleef. “Once in a while the city editor offers me an excursion assignment. Then I take a day off from study and get paid for going into the country at the same time.”

“An excursion assignment?” questioned Myles.

“Yes; every job on which a reporter is sent is called an ‘assignment,’ or, in some offices, a ‘detail,’ and if he is sent on a Chinese picnic, or down the bay with the newsboys, or up the Sound with the fat men, or on any other trip of that kind, it is an excursion assignment.”

“Well, look here, Van Cleef, it seems to me that you are one of the most plucky fellows I ever met!” exclaimed Myles, extending a hand that the other grasped heartily, “and I am ashamed of myself not to have known you before.”

“I don’t know that that has been your fault so much as my own. I knew that I had no business with your set of fellows, so I have kept out of your way as much as possible,” remarked the other, quietly.

“And a good thing for you that you have,” cried Myles, bitterly, “for my opinion of that set of fellows is—well,” he added, checking himself, “never mind now what it is. I have done with them, and they with me. The question of present interest is, do you think I could ever make a reporter; and, if so, can you tell me where to find a job at the business?”

By these questions it will be seen that our young man’s ideas concerning business, and the business of reporting in particular, had undergone some very decided changes since he left home that morning.

“You are undoubtedly bright enough and smart enough,” answered Van Cleef, “and I have no doubt that if you should stick to the business long enough, and accept its rough knocks as a desirable part of your training, you could readily become a first-class reporter. As for obtaining a job at it, that is quite another thing. The newspaper offices all over the country, and especially in New York, are besieged by young fellows who want to try their hand at reporting, but not one in a hundred of them is taken on. I’ll tell you, though, what we will do. The only paper on which I know anybody of influence is the Phonograph, and perhaps you wouldn’t like it as well as some other. So you take a run by yourself among the offices of all the big dailies this afternoon. The little ones are not worth trying. Send your card in to the city editors, and apply for work. If you don’t find any that suits you, meet me at the Phonograph office at five o’clock and I’ll introduce you to the city editor there. I don’t say that my introduction[25] will do any good. Probably it won’t; but at any rate it will give you a chance to talk with him, and plead your own case. Afterward we will dine together somewhere, and then, if you choose, you can go with me on my round of stations.”

“Good enough!” cried Myles; “that’s an immense plan, and we will carry it out to the letter. You won’t mind if I say there are one or two papers that I’d rather become connected with than with the Phonograph. That seem just a little more respectable and high-toned, don’t you know.”

“Oh, yes, I know,” laughed Van Cleef, “and my feelings are not in the slightest ruffled by your prejudice, which is quite a popular one. I attribute it wholly to your ignorance, and know that you will outgrow it before you have been many days a reporter.”

“And, by the way,” said Myles, as the other was about to leave the room, “you must dine with me at the Oxygen to-night. It may be the last time I am ever able to take anybody there, you know.”

“All right,” answered Van Cleef. “Good-bye till this evening.”

The sale, to a dealer in such things, of the furniture,[26] pictures, and costly but useless knick-knacks with which his room was crowded, enabled Myles to pay his debts and left him about ten dollars with which to make a start in the business world. It was after two o’clock when he completed his arrangements for leaving college. He was strongly tempted to go to the river and take a look at the crew in their practice spin; but “business before pleasure,” the motto that he had already used once that day, flashed into his mind, and he resolutely turned his face toward downtown and the newspaper offices.

Arrived at the office of the paper which, for some unexplainable reason, he considered the most respectable of all, he naturally turned into the counting-room that was located on the ground floor and inquired for the city editor.

“Editorial rooms up-stairs,” was the curt answer of a busy clerk, who did not even look up from the work upon which he was engaged.

When an elevator had lifted Myles to the very top of the tall building, he found himself in a small, bare room provided with two or three chairs, and a bench upon which two small boys were playing at jackstones. One of them, leaving his game and[27] stepping smartly up to Myles, asked what he wanted there.

“I want to see the city editor,” was the answer.

“What’s your business with him?” asked the boy.

“None of your business what my business is, you impudent young rascal,” answered Myles, angrily. “Go at once and tell the city editor that I wish to see him.”

“And who are you, anyway?” demanded the boy, assuming an aggressive attitude, with arms akimbo and head cocked to one side. The other boy, whose interest was now aroused, came and stood beside his companion in a similar attitude, and they both gazed defiantly at the young man.

The situation was becoming ridiculous, and, to relieve himself from it as quickly as possible, Myles produced his card-case, thrust a card into the hand of the first boy, and said, in a tone of suppressed rage:

“Take that to the city editor this instant, you imp, and say that the gentleman wishes to see him on business, or I’ll throw you out of that window.”

Somewhat frightened by Myles’ tone the boy left the room muttering:

“A fine gentleman he is, ain’t he! A-threatening of a chap not half his size.”

In less than a minute he returned with a renewed stock of impudence. Offering the card back to Myles he said:

“The city editor says that he don’t know you, and you’ll have to send word what your business is with him.”

It was too humiliating. Myles could not confide to the grinning figures before him that he was seeking a reporter’s position, and so, muttering some unintelligible words, he turned to leave. He had to wait several minutes for the elevator, and while he did so he could not help overhearing the jeering comments of the two young rascals upon himself. One of them said:

“He’s out of a job, that feller is, and he came here to offer hisself as boss editor.”

“Naw, he didn’t neither,” drawled the other. “He ain’t after no such common posish as that. What he wants is your place or mine. But he’s too young, and fresh, he is. He wouldn’t suit. No, sir-e-e.” And then the two little wretches exploded with laughter at their own wit.

Myles walked about the City Hall Park for some time before he could summon up sufficient courage for a second venture. When at last he found his way to another editorial waiting-room it was only to be informed that the city editor was out and would not be back until six o’clock.

A third attempt resulted in his being ushered into the presence of a brisk young man, apparently not much older than himself. This self-important individual listened impatiently while Myles hesitatingly made known his desires, and promptly answered:

“Very sorry, sir, but absolutely no vacancy in our staff. Five hundred applicants ahead of you. No chance at all. Good-day.”

Thus dismissed Myles got out of the office somehow, though how he could not have told. His mind was filled with mortification, disappointment, and anger at everybody in general and himself in particular for being so foolish as to imagine that it was an easy thing to obtain a position as reporter on a great daily.

It was after the appointed hour before he was sufficiently calmed down to visit the office of the Phonograph, and he found Van Cleef anxiously awaiting him.

“Well,” he said, questioningly, after he had passed Myles through a boy-guarded entrance into a large, brilliantly lighted room in which a number of young men sat at a long desk busily writing. “How have you got on?”

“Not at all,” answered Myles, “and I don’t believe I am ever likely to.”

“Nonsense! You mustn’t be so easily discouraged. Come and let me introduce you to Mr. Haxall, our city editor. He is a far different kind of a man from any of the others, I can tell you.”

Mr. Haxall was kindly polite, almost cordial in his manner, and listened attentively to Myles’ brief explanation of his position and hopes. When it was finished he, too, was beginning to say, “I am very sorry, Mr. Manning, but we have already more men than we know what to do with,” when Van Cleef said something to him in so low a tone that Myles did not catch what it was.

“Is that so?” said Mr, Haxall, reflectively, and looking at Myles with renewed interest. “It might be made very useful, that’s a fact. Well, I’ll strain a point and try him.”

VAN CLEEF SAID SOMETHING TO THE CITY EDITOR IN A LOW TONE. (Page 30.)

Then to Myles he said:

“Still, we are always on the lookout for bright, steady young fellows who mean business. So if you want to come, and will report here at sharp eleven o’clock to-morrow morning, I will take you on trial till next Saturday and pay you at the rate of fifteen dollars per week.”

CHAPTER III.

THE OLD GENTLEMAN OF THE OXYGEN.

POOR Myles had met with so many rebuffs and disappointments, and his own opinion of himself had been so decidedly lowered that afternoon, that he was fully prepared to have his offer of service refused by the city editor of the Phonograph. He was therefore not at all surprised when Mr. Haxall began in his kindly but unmistakable way to tell him that there was no vacancy. He had already made up his mind to give up trying for a reporter’s position and make an effort in some other direction, when, to his amazement, he found himself accepted and ordered to report for duty the following day. It was incomprehensible. What had Van Cleef said to influence the city editor so remarkably?

There was no chance to ask just then, for Mr. Haxall had already resumed his reading of the evening papers, a great pile of which lay on his desk, and[33] Myles realized that the short interview, by which the whole course of his life was to be affected, was at an end. So he merely said: “Thank you, sir, I’ll be on hand,” and turned to follow Van Cleef, who had already started toward the door.

The boy’s mind was in a conflicting whirl of thoughts, and he was conscious of a decided sense of exaltation. He had actually got into business and was to receive a salary. To be sure, it was only promised for one week; but even in that short time he felt that he could prove so useful that the city editor would wonder how he had ever got along without him.

As they passed into the anteroom of the office Van Cleef introduced his companion to a Mr. Brown, a stout, middle-aged man, who occupied a dingy little den, in which he was busily writing by the light of a single gas-jet. Mr. Brown was affably condescending, was pleased to make Mr. Manning’s acquaintance, and hoped he would like the office.

As they bade him good-evening and started downstairs Myles asked:

“Who is this Mr. Brown, Van? Is he one of the editors?”

“Bless you, no,” laughed Van Cleef. “He is the janitor of the building.”

“The janitor!” exclaimed Myles, with a slight tone of contempt in his voice. “Why, I thought he must be the managing editor at the very least. What on earth did you want to introduce me to the janitor for? I’m not in the habit of knowing such people.”

“Oh, you are not, aren’t you!” replied Van Cleef, a little scornfully. “Well, the sooner you form the habit the better you will get along as a reporter. It’s no use putting on airs, old man,” he continued, more kindly. “A reporter has got to be on friendly terms with all sorts of men, from presidents to janitors, and a good deal lower in the social scale than that too. Besides, Brown is a mighty good fellow, as you will find out when you come to know him. He also occupies a position in which he can smooth your path or make you uncomfortable in many little ways, as he takes a notion. Why, for one thing, he has charge of all those rascals of office-boys, and they will treat you respectfully or the reverse according as they see that you are in Brown’s good or bad graces. That seems a little thing, but you will find that it makes a great difference to your peace of[35] mind. Oh, yes, you must cultivate Brown by all means.”

When they were seated in the elevated train on their way up-town Myles suddenly remembered his companion’s mysterious communication to the city editor, and asked him what he had said to cause Mr. Haxall to alter his decision so completely.

“It was evident,” he continued, “that he was about to give me a polite dismissal, but you whispered a word or two in his ear and he immediately engaged me. What was it? Did you tell him I was one of the principal stockholders in the paper?”

Van Cleef burst into a fit of laughter so uncontrollable that it was a full minute before he could answer. At last he said:

“No, indeed; I didn’t tell him that you were a stockholder in the paper; for, in the first place, I didn’t know that you were. In the second place, the stockholders are the bane of his existence, and worry him more than anybody else by forcing worthless fellows, who have some claim upon them, into his department. Oh, no, I wasn’t going to ruin your chances by representing you in any such unfavorable light as that.”

“What did you tell him then?”

“Why, I simply mentioned that you owned a dress-suit.”

For a moment Myles stared at his companion in speechless amazement. Finally he gasped out:

“A dress-suit! You told him that I owned a dress-suit! What in the name of common sense could that have to do with his taking me on as a reporter? Or are you only joking?”

“Not a bit of it,” answered Van Cleef. “It honestly was the dress-suit, and nothing else, unless it was your manner and personal appearance that fixed the business for you. You see, there are lots of places to which a city editor wishes to send a reporter where only fellows in full evening dress are admitted. Now, most reporters are too poor to own dress-suits, or else they have so little use for such luxuries that they don’t care to go to the expense. Thus it is often hard for the city editor to find a man for some important bit of work just on this account. He therefore keeps a list of all the reporters on the staff who own swallow-tails, and is mighty glad to add to it, especially if the proposed addition is evidently a gentleman. I saw that he wasn’t[37] going to give you a show, and just then it occurred to me to suggest the only special recommendation I could think of. But what makes you look so downcast? It worked all right, didn’t it?”

“Oh, yes,” answered Myles, whose self-esteem had just received the severest shock of the day by learning the secret of his recent success, which he had fondly imagined was owing to something far different. “Yes, it worked all right; but I’ve always heard that clothes did not make the man, while here is proof positive that clothes can at least make a reporter. It is awfully humiliating, and the worst of it is that I haven’t a dress-suit.”

“Why, I have seen you wear it time and again?” exclaimed Van Cleef.

“Yes, but I found it necessary to raise a little ready money to-day,” answered Myles, though he hated to make the admission; “so I sold it along with some other things I thought I should never need again to Johnny, the ‘old-clo’ man.’”

“You don’t mean it!” cried Van Cleef. “Well, that is bad, and the only thing for you to do is to go to Johnny first thing in the morning and make him let you have it back.”

“But I am afraid I haven’t money enough to redeem it,” said Myles, with a heightened color. In the set to which he had so recently belonged poverty was the thing most sneered at, and Myles had not yet learned that it was one of the last things to be ashamed of.

“Oh, I can make that all right,” answered the other, cheerfully. “I have a few dollars put away against next year’s term-bills, and you are more than welcome to them. Yes, indeed, you must take them,” he added, earnestly, as he saw the shadow of a refusal in his companion’s face. “We must get hold of that dress-suit again if it is a possible thing. It will really be doing me a favor besides; for while I have them I’m always tempted to spend those dollars. If they are invested as a loan, though, I can’t spend them, and I shall have the satisfaction of knowing they are safe.”

Myles had tried, unsuccessfully, to borrow a small sum of money that morning from several of his wealthy classmates. Now, to have this generous offer made by one of the very poorest among them was so overwhelming that he hardly knew what to say. He hated to accept money from one who was so little[39] able to spare it. He also feared to hurt his friend’s feelings by refusing, and he realized the importance of recovering that dress-suit. These thoughts flashed through his mind in an instant, and then he did exactly the right thing, by heartily thanking Van Cleef for his kind offer and accepting it.

The “Oxygen” was a club occupying a small but well appointed club-house, supported by one of the college Greek-letter fraternities of which Myles had recently been made a member. He was very proud of belonging to this, his first club, but he foresaw that, with his altered circumstances, it was a luxury that he could no longer afford. He had therefore made up his mind to hand in his resignation that very evening.

After a particularly nice little dinner, for Myles, like many another, was inclined to be very generous in the expenditure of his last dollar, and after he had written a line to his mother, the friends sat in the reading-room. Here they talked in low tones of their future plans and of their college life, which, to Myles, already seemed to belong to the dim past. The only other occupant of the room was a small, rather insignificant looking old gentleman, who was[40] carelessly glancing over some papers at a table near them. Finally Van Cleef asked to be excused for a short time, as he had an errand that would take him a few blocks from there, and which must be done that evening.

He had hardly left when the old gentleman looked up from his papers and said to Myles:

“I beg your pardon, but are you not Mr. Manning, captain of the X—— College ’Varsity crew?”

“Yes, sir,” answered Myles, “I am—that is, I was—I mean my name is Manning, and I was until this morning captain of the crew; but I have resigned.”

“Indeed! I am very sorry to hear it,” replied the old gentleman, with an air of interest. “Would you mind telling me why you found it necessary to do so? I am an old X—— College man myself, and take a great interest in all its athletic sports, especially its boating. I have been much pleased with the performance thus far of this year’s crew under your captaincy, and regret seriously that you feel obliged to give it up.”

Encouraged by the old gentleman’s friendly manner, and very grateful for his sympathy and kindly interest in himself, Myles readily answered his questions,[41] and within a few minutes was surprised to find how freely he was talking to this stranger. He could not have told how it was brought about, but before their conversation ended he had confided to the other all his trials, plans, and hopes, including the facts that he was on the morrow to begin life as a reporter on the Phonograph, and that he intended resigning from the Oxygen that evening.

When Myles realized that he was becoming almost too confidential, and checked himself as he was about to relate the dress-suit incident, the old gentleman said:

“I have been greatly interested in all this, and now, to show that I appreciate the confidence you have reposed in me, I am going to ask a favor of you.”

“Which I shall be only too happy to grant, sir, provided it lies within my power,” answered Myles, who had taken a great fancy to the old gentleman.

“It is that you will not resign from the Oxygen.”

“But I must, sir, much as I hate to.”

“Not necessarily,” replied the other. “You know that at the business meetings of the club all members are allowed to vote by proxy if they are unable to be personally present. Now I am nearly always[42] compelled to be absent from these meetings. In fact, I rarely find time to visit the club at all; but, as one of its founders, I am most anxious for its success, and desirous of still having a voice in the conduct of its affairs. This I can only do by appointing a regular proxy, and if you will kindly consent to act as such for me I will gladly pay your dues to the club, and shall still consider myself under an obligation to you.”

The temptation to accept this friendly proposal was so great that Myles only protested feebly against it. His faint objections were quickly overruled by the old gentleman, who had no sooner gained the other’s consent to remain in the club and act as his proxy than he looked at his watch and, exclaiming, “Bless me, it is later than I thought!” bade Myles a cordial good-night and hurried away.

“What did you say his name was?” asked Van Cleef, after he had returned and listened to Myles’ enthusiastic description of his new friend and account of their interview.

“His name?” repeated Myles, hesitatingly, “why, I don’t believe he mentioned it. I’ll go and ask the door-tender.”

But the door-tender had just been relieved and gone home, while the boy who acted in his place of course knew nothing of who had come or gone before he went on duty.

“Well, that is good,” laughed Van Cleef, when Myles returned and, with a crestfallen air, announced that he could not discover the name of the person for whom he had just consented to act as proxy. “The old gentleman has shown himself to be a better reporter, or detective, which is much the same thing, than you, Manning. He has gained a full knowledge of you and your plans, while you have learned absolutely nothing about him. He may be an impostor, for all you know.”

“Not much he isn’t,” answered Myles, somewhat indignantly; “I’d trust his face for all that he claimed, and a good deal more beside. Anyhow he is a Psi Delt, for he had the grip.”

“Oh, well,” said Van Cleef, good-naturedly, seeing that his companion was a little provoked at being thought easily imposed upon, “I dare say it’s all right, and you’ll hear from him in some way or other.”

As the friends thus talked they were walking[44] rapidly toward the first of the many police-stations that Van Cleef was obliged to visit every night, for it wanted but a few minutes of ten o’clock.

The plain brick building situated in the middle of a block and used as a police-station could be distinguished from the houses on either side of it at a long distance up or down the street by the two green lights on the edge of the sidewalk in front of it. Reaching it, the reporters ran up a short flight of steps, and entered a big square room, the silence of which was only broken by the ticking of a telegraph instrument in one corner. The room was brightly lighted and scrupulously clean. An officer in a sort of undress uniform, who is known as a “door-man,” whose business it is to take care of the station-house and of the cells beneath it, saluted Van Cleef as he entered. Returning the salute, the reporter stepped up to a stout railing that ran the whole length of the room at one side, and, addressing another officer, who sat at a big desk writing in an immense book, said:

“Good-evening, sergeant.”

“Good-evening, Mr. Van Cleef.”

“Any thing going on to-night?”

“Nothing more than ordinary.”

“You don’t mind my looking at the blotter?”

“Certainly not.”

“Hello! what’s this drowning case?” inquired Van Cleef, as he ran his eye down a page of the big book, on which were recorded the arrests or other important incidents reported by the officers of that station during the day.

“That? Oh, that’s nothing particular. It happened a couple of hours ago, and your head-quarters man has got all there is of it long before this.”

Van Cleef asked no further questions, but, making a few notes of the case, he bade the sergeant good-night, and he and Myles left the station.

As they gained the street Van Cleef said:

“Head-quarters may or may not have got hold of that case, and it may not amount to any thing anyway, but I think it’s worth looking up. So if you don’t mind going a bit out of our way, we will see what we can find out about it.”

“What do you mean by head-quarters?” asked Myles.

“Why, all the large papers keep a man at the Police Head-quarters on Mulberry Street day and[46] night, and he telegraphs all important police news from there to them,” answered Van Cleef.

Away over to Tenth Avenue they went. There they hunted some time before they found the right number. Then through a narrow, intensely dark and vile-smelling alley, across a dirty court, and into a tall back tenement swarming with human beings, up flight after flight of filthy stairways they climbed to the very top of the house before they reached the room of which they were in search. Van Cleef knocked at the closed door, but, receiving no answer, he pushed it open and they entered.

A single flaring candle dimly lighted the scene. The room was so bare that a rude bedstead, a ruder table, two chairs, and a rusty stove constituted all its furniture. On the bed, still in its wet clothing, lay the body of the drowned man. It was little more than a skeleton, and the cheeks were white and hollow. Beside the bed, with her face buried in her hands, knelt a woman moaning, while from a corner two wretched children, huddled together on a pile of rags, stared at the visitors with big, frightened eyes.

As Van Cleef touched the kneeling woman on the[47] shoulder and spoke to her, she ceased her moaning and lifted the most pitiful, haggard, and altogether hopeless face Myles Manning thought he had ever seen.

“Go away!” she cried, “and leave me alone to die with him! O Jim, my Jim! why couldn’t you take me with you? Why did you leave me, Jim—Jim—my Jim, the best husband that ever a woman had?” Then she again buried her face, and again began her heart-rending moaning.

It was a long time before Van Cleef, using infinite patience, tact, and soothing words could learn her story. It was an old one of a husband and father broken down in health, thrown out of employment, too proud to seek public charity, and finally plunging into the river to escape the piteous cries of his starving little ones. He had gone out that evening to seek food, saying that he would either bring it or never come back alive. He knew that if he were dead his family would stand a better chance of being cared for than while he was living.

As Myles and Van Cleef left this place of sorrow and suffering, the latter slipped a dollar into the woman’s hand and promised further aid on the morrow. Myles, poor fellow, was so affected by[48] what he saw that he would have given her his sole bit of wealth—a five-dollar bill,—but his companion restrained him.

They had to hurry through with the half-dozen police-stations and two hospitals remaining on their route to make up for lost time.

Trinity bells were chiming a quarter to one o’clock as they reached the Phonograph office. The editorial rooms were ablaze with electric lights. Reporters and messenger-boys were dashing in and out. Men in their shirt-sleeves were writing or editing copy at the long desks. The whole scene was the one of breathless haste and well ordered confusion that always immediately precedes the going to press of a great daily.

Van Cleef made his report to the night city editor, and was ordered to write out his story in full. While he was doing this, Myles sat and watched him, wondering if he could possibly compose a readable description of what they had just seen amid such surroundings. At last Van Cleef finished, handed in his copy, and at half-past two o’clock the two weary fellows turned into bed, Myles sharing his companion’s humble lodgings for the night.

CHAPTER IV.

BEGINNING A NEW LIFE.

VAN CLEEF seemed to fall asleep at once, but the novel train of thought whirling through Myles’ brain rendered it impossible for him to follow this example immediately. As he lay, with wide-open eyes, recalling the incidents of the day it seemed incredible that he had seen, and learned, and gone through with what he had, all within the space of a few hours. Could it be that he had left home prepared to give up his college life only that morning? He must send them a long letter, for they would be so anxious to hear every thing that had happened to him. As he said this to himself his thoughts merged into dreams so gradually that he had no knowledge of where the one ended and the other began.

“Wake up, old man, wake up! Here it is nine o’clock Tuesday morning and the week’s work yet to be done.”

It was Van Cleef’s voice, and as Myles sprang to a sitting posture and rubbed his eyes he saw his friend standing beside the bed fully dressed and looking as bright as if sleep were something for which he had no need.

“Yes,” he said, in answer to Myles’ inquiring glance, “I have been up and out for an hour, and I’m sorry to say that I have bad news for you.”

Myles’ expression at once became anxious. Had the city editor sent word that he had changed his mind and did not want him after all?

“You see,” continued Van Cleef, “I was worried about that dress-suit business. So I just slipped out without waking you, and went up to old Johnnie’s to get it; but I was too late. He sold it last evening; and so—there we are!”

“Then I suppose there is no use of my going down to the Phonograph office again,” said Myles, trying to speak with a cheerfulness that he did not feel.

“No use!” exclaimed the other. “Why, of course there is. You are under orders, you know, and must at least report for duty, whether you are wanted or not. The only thing is that you will have to tell Mr. Haxall.”

“Yes, I suppose I must,” answered Myles, soberly, as he began to dress, “and then he will probably tell me that a dress-suit, and not Myles Manning, was what he engaged, and that without it he has no use for its late owner. I suppose I can stand it, though, as well as another, but it will be a disappointment.”

“Of course it will if it comes,” replied Van Cleef, cheerfully; “but I do not believe it will. At any rate there is no use making matters worse by worrying in advance; so let’s brace up and go out for breakfast. I’m as hungry as a boot-black. By the way, I spoke to my landlady this morning and find that she has a vacant hall-bedroom that you can have for three dollars a week if you want it. It’s small, but it’s clean and airy, and this is a most respectable neighborhood. Above all, it is cheap, which is the main thing with me, and also, I take it, with you just at present.”

“Of course it is,” answered Myles, “and I shall be only too glad to be in the same house with you. You are almost the only friend I own now; at any rate, you are the most valuable one.”

As he spoke Myles found himself wondering if this valued friend could be the same class “dig”[52] with whom he had been barely on speaking terms only the morning before.

At a small but tidy restaurant near by, they obtained an excellent breakfast of coffee, rolls, and boiled eggs, for twenty-five cents apiece. Van Cleef apologized for this unusual extravagance, saying that he generally breakfasted on coffee and rolls alone for fifteen cents, but that this was an occasion.

In the restaurant they found copies of the morning papers, and Myles, paying no attention to those that he had been in the habit of reading, eagerly seized the Phonograph. Yes, there it was; a half-column account of the scene they had witnessed the night before in the Tenth Avenue tenement-house. How interesting it was! How well expressed, and what a pathetic picture it presented of that room and its occupants! As Myles finished reading the story he turned to his companion with honest admiration.

“You are a regular out-and-out genius, Van!” he exclaimed. “If I could write a story like that and get it printed I’d be too proud to speak to common folks, and I’d expect to have my salary raised to the top notch at once.”

“Well, I fancy you’d have to take it out in expecting, then,” laughed the other. “That may be a fair sort of a story, and I won’t say that it isn’t, but at the same time I doubt if any one besides yourself gives it a second thought. You wouldn’t if you’d been in the office a week or two and studied the other fellows’ work. Why, the very brightest men in the city are on the Phonograph, as you will soon discover. As for a raise of salary—well, you will have to write many and many a story better than this little screed of mine before that happy event takes place.”

“Then mine will continue to be fifteen per week for the rest of my natural life, or, rather, for as long as they will let me hang on down there, I’m afraid,” sighed Myles.

“Not a bit of it, my dear fellow. A year from now you will be ’way up, probably on space, and looking back with infinite pity upon yourself as a salary man at fifteen dollars a week. There is just one bit of advice, though, that, if you will let me, I should like ever so much to give you as a starter. It is, never refuse an assignment. No matter how hard or distasteful or insignificant the job promises to be,[54] take it without a word and go through with it to the best of your ability without a murmur. Also, never hesitate to take hold of any piece of work offered you for fear you may not be capable of performing it. A reporter must be capable of any thing and must have the fullest confidence in himself. If the city editor says some fine morning, ‘Mr. Manning, the Phonograph wishes to locate the North Pole; will you be kind enough to go and discover it?’ you must answer, ‘Certainly, sir,’ and set off at once. Such an undertaking might prove expensive; but that is the city editor’s lookout, not yours. You are under orders exactly as though you were in the army, and your responsibility ends with obeying them to the letter. Now I must be off to recitation and you must be getting downtown. So good-bye, and good-luck to you. I shall probably see you again at the office this evening.”

All the way downtown the wheels of the elevated train seemed to rattle out, “Under orders, under orders,” and Myles could think of nothing else.

“How many people are ‘under orders!’” he said to himself as he reflected that most of the best work[55] of the world was accomplished by those who obeyed orders. Thus thinking he finally decided that he was proud of being “under orders,” and that if he could make a name in no other way he would at least gain a reputation for strict obedience to them. In reaching this conclusion he took a most important forward step, for in learning to obey orders one also learns how to give them.

Myles reached the office a few minutes before eleven o’clock, and, walking boldly past the boys who guarded its entrance, bowing to, and receiving a pleasant “good-morning” from, Mr. Brown as he did so, he entered the city-room, as that portion of the editorial offices devoted to the use of reporters and news editors is called.

The great room was as clean, neat, and fresh as the office-boys, who had been at work upon it for the past hour, could make it. Every desk and chair was in its place, and not a scrap of paper littered the newly swept floor. In the corner farthest from the entrance, beside a large open window that overlooked the busy scene of Park Row, City Hall Park, and Broadway beyond it, sat the city editor before a handsome flat-topped desk. Other single desks[56] occupied favorable positions beside other windows, but their chairs were vacant at this early hour. Down the middle of the floor ran two parallel rows of double desks, each containing a locked drawer and each supplied with pens, ink, writing-and blotting-paper. These were for the reporters. At one side was a long reading-shelf, beneath which hung files of all the city papers. At the back of the room was a row of lockers like those in a gymnasium, in which were, kept overcoats, hats, umbrellas, and other such articles belonging to the occupants of the office.

A dozen or more bright-looking, well-dressed young men sat or stood about the room chatting, reading the morning papers, or holding short consultations with the city editor. While talking with them he hardly looked up from the paper that he was glancing over with practised eyes, and occasionally clipping a paragraph from with a pair of long, slim shears. He took these papers from a pile lying on his desk that contained a copy of every morning daily published in New York, Brooklyn, or Jersey City. The little slips that he cut from them were laid by themselves at one end of his desk.

It was a pleasant room. Its very air was inspiring, and Myles wished he were sure of being permanently established as one of its occupants. But the thought of the confession he had to make, and of its probable results, weighed heavily on his mind. He was impatient to have it over with and to know the worst at once.

Walking straight up to the city editor’s desk he said:

“Good-morning, Mr. Haxall. I——”

“Ah, good-morning, Mr. Manning. Glad to see you so promptly on hand. If you will find a seat I’ll have time to talk with you in a few minutes.”

So Myles found a seat on a window-sill and amused himself by watching what was going on around him. He noticed that as each reporter entered the room he walked directly to a slate, that hung on the wall near the door, and read carefully a list of names written on it. He afterward found that this was a list of those for whom mail matter had come addressed to the office. Having received his letters from Mr. Brown, and taken one or more copies of the morning Phonograph from a pile on the janitor’s desk, each reporter occupied himself as[58] he chose until summoned by Mr. Haxall and given an assignment.

Upon accepting this, his name and the nature of the duty he was about to undertake were entered on the page, for that day, of a large blank-book known as the “assignment book.” Myles also noticed that nearly every assignment was given in the form of one of the slips clipped from other papers by the city editor. The reporter generally walked slowly away, reading this slip, and studying the problem thus presented to him, as he went. When, some days afterward, Myles had a look at this famous assignment book he found that each of its pages was dated, and that in it clippings, referring to future events, were entered under their respective dates.

The young reporter sat so near the city editor’s desk that he could catch fragments of the conversation between Mr. Haxall and those whom he was dispatching to all parts of the city, its suburbs, and apparently to remote corners of the country as well He overheard one young man ordered to take a journey that would certainly occupy days and possibly weeks. Myles watched this reporter with[59] curious eyes as, after taking a small hand-bag from his locker, he left the office as carelessly as though his journey was only to be across the Brooklyn Bridge instead of into a wilderness a thousand miles away, as it really was.

Myles envied this reporter, as he also did another who was sent out to the very New Jersey village in which his own home was located. How he did wish he might have that assignment.

At length when the others had been sent away on their respective errands Mr. Haxall called his name, and he stepped forward with a quickly-beating heart to receive his first assignment.

“I only wanted to know your city address, Mr. Manning,” said the city editor, looking up with a pleasant smile. “We find it necessary to know where our reporters live, so that in an emergency they may be reached out of office-hours.”

When Myles had given the required address he still remained standing before the desk. Noticing this Mr. Haxall again looked up and said:

“Is there any thing else?”

“Yes, sir,” answered Myles, hesitating and becoming very red in the face, like a school-boy before[60] his master, “I wanted to say that I haven’t any dress-suit.”

“Haven’t what?” asked the city editor, in amazement.

“A dress-suit.”

“Haven’t a dress-suit?” repeated Mr. Haxall, with a perplexed air, and regarding Myles as though he feared for his mental condition. “Well, what of it?”

“Why, I thought the reason you engaged me was because I owned a dress-suit. Mr. Van Cleef told me so.”

“Oh,” laughed the city editor, tilting back in his chair for the fuller enjoyment of his merriment. “That’s a good one! And now it seems that you don’t own a dress-suit, after all. Well, I am sorry; but never mind, we will try to get along without it, and I will find something for you to do directly that won’t require one.”

So the confession was made and Myles had not lost his place, after all. He resumed his seat with a light heart and for another hour patiently awaited orders. In the meantime several men came in, wrote out their reports, handed them to the city editor, and[61] were sent off again. Mr. Haxall filed most of these reports on a hook without even glancing over them.

At the end of an hour, when the office was completely deserted by all except the city editor and himself, Myles was again called by name.

“Now,” thought he, “I am surely to get an assignment.”

And so he did, though it was by no means such an one as he expected. Handing him a ten-cent piece, the city editor said:

“I find that I can’t take time to go out for lunch to-day, Mr. Manning, and as the office-boys seem to be absent, will you kindly run out to the nearest restaurant and get me a couple of sandwiches?”

It was disappointing and mortifying to be sent on such an errand, and for an instant Myles’ pride rebelled against it. Then the words “under orders,” together with Van Cleef’s advice, flashed into his mind, and with a cheerful “Certainly, sir,” he started off.

When he returned and laid the sandwiches, neatly done up in thin white paper, on Mr. Haxall’s desk, that gentleman said:

“I wish you would just step over to Brooklyn,[62] Mr. Manning, and report to Billings at Police Head-quarters. He has charge of the horse-car strike over there, and telegraphs that he can use another man to advantage.”

“Is he a police captain, sir?” asked Myles, not knowing who Billings might be.

“A police captain? Of course not. What put that idea into your head?” replied Mr. Haxall, a little sharply. “Billings is one of our best reporters, and, as I said, is in charge of this street-car strike.”

“Oh, thank you, sir,” answered Myles, as he started off greatly enlightened by this explanation.

He had no difficulty in finding Brooklyn, because he had been there before; but he was obliged to inquire the way to Police Head-quarters. A few years ago he would have had a long walk before reaching it, for not one of the hundreds of horse-cars that usually throng the tracks on Fulton Street was to be seen. Their absence made that part of the city seem strangely silent and deserted; but fortunately the elevated trains were running, and Myles soon reached his destination.

The street in front of Police Head-quarters was[63] blocked by a good-natured throng of strikers, through which Myles had some difficulty in forcing his way. At the door he was met by a policeman, who gruffly said: “No admittance, young man,” and immediately afterward, when Myles had stated his business, “Certainly, walk right in. You will find Mr. Billings in the inspector’s room.”

Now Myles had formed an impression of Billings, which was that he must be a man much older than himself, and probably larger and stronger, or else why should he be detailed for this especial work? He expected to find him busily engaged in writing, or dispatching other reporters hither and thither, and having the anxious, self-important air of one who occupied a delicate and responsible position.

The real Billings as he there appeared, seated at a table in the inspector’s room intent upon a game of dominos with the inspector himself, was about as different from this impression as it is possible to conceive. He was a slightly-built, delicate-looking young man, apparently not any older than Myles, and with a beardless face. He was exquisitely dressed, deliberate in his movements, and so languid of speech that it seemed an effort for him to talk.[64] Myles remembered to have seen him in the Phonograph office that morning and to have wondered what business that dude had there.

However, this was undoubtedly the Billings to whom Mr. Haxall had ordered him to report, and he accordingly did so.

“Yes,” said Billings, with a gentle drawl, as he looked up from his game and regarded Myles with a pair of the most brilliant and penetrating eyes the latter had ever seen. “Just had a dispatch about you from Joe (Mr. Joseph Haxall). New man. Name of Manning. Break you in. Well, Manning, there’s a strike. No horse-cars all day. Railroad officials about to send car out on B—— Avenue line. Leaves stable in fifteen minutes. Probably be some fun. You may go and ride on this car. Have a good time. Take it all in, then come back here.”

Myles could have choked the little fellow who coolly sat there telling him to do thus and so. For the second time that day he was strongly tempted to rebel and to maintain his dignity. The idea of that “little absurdity,” as he mentally styled Billings, issuing commands to him! Then for the second time came the words “under orders.” Had[65] he not been ordered to obey Billings? To be sure he had, and with an “All right” he left the building.

As he made his way toward the car-stables he wondered why Billings had not undertaken that ride himself, as he seemed to have nothing else to do except play dominos. The more he thought of it the more he became convinced that it was because Billings was afraid.

CHAPTER V.

THE KIND OF A FELLOW BILLINGS WAS.

“YES, Billings must be afraid,” said Myles, to himself, “and I don’t know but what I would be, too, if I were such a white-faced little chap as he is.” Here Myles threw back his own broad shoulders, held his head a trifle higher than usual, and rejoiced in the stalwart frame that had been such an ornament in the X——“‘Varsity” boat. “I wonder what Mr. Haxall meant,” he continued to himself, “by speaking of him as one of the best reporters on the Phonograph. If he should see him at this moment I rather think he would call him something else. How little a city editor can really know of his men any way!”

While thus thinking Myles was threading the unfamiliar streets of a city as strange to him as though it had been a hundred miles from New York, in search of the car-stables of the B—— Avenue line.

It took him so long to find them that, when he finally did so, the car on which he was ordered to ride had been gone some ten minutes. There was nothing to do but overtake it if possible, and the young reporter started down the track at the same pace he was accustomed to set for his crew when they were out for a “sweater,” as they called their training runs.

After running half-a-dozen blocks he began to meet signs of the strike. Here was a broken and overturned market-wagon that had evidently been placed across the track as a barricade, and there a place from which some paving-stones had been torn up. Now he began to be joined by others running in the same direction with himself, and to hear a noise different from the ordinary sounds of the city. As he rounded a corner this noise resolved itself into the shouts, cheers, and yells of an angry mob, and above all rang out sharply an occasional pistol-shot.

The street was filled with hundreds of excited men and boys, whose number was constantly increasing. They were all crowding toward some object of common interest which, when he got close enough to make it out, Myles saw was the very car in which[68] he had been ordered to ride. It was occupied by a dozen or so of policemen, and was slowly urging its way forward with frequent halts, while another squad of policemen cleared a passage for it through the crowd. Every now and then a paving-stone crashed through a window or splintered the woodwork of the car. A throng of reckless men surged alongside of it, trying in every way they could think of to impede its progress. The company had declared this car should go through. The strikers declared it should not. They tried to lift it from the rails, to overturn it, to drag the driver from his platform, to kill the horses, or in some other way to stop that car.

By a steady use of their long, powerful night-clubs, the police who guarded the car had thus far kept the mob at bay, and prevented them from accomplishing their purpose.

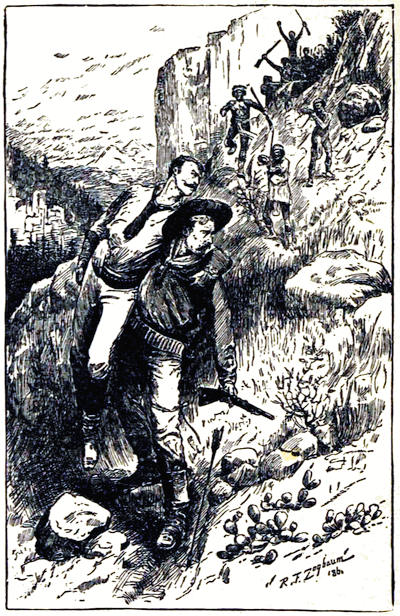

A HOARSE VOICE SHOUTED THE OMINOUS WORD “SPOTTER.” (Page 69.)

Through this angry throng Myles now began to make his way, for he had been sent to ride with those policemen, and he was determined to do so if it were a possible thing. At first he had comparatively little trouble; but as he approached the thick of the crowd he was obliged to push so roughly, and make such decided efforts to get ahead, as to draw attention upon himself. At first he was only shoved, and his way was purposely blocked. Then the looks of those about him began to grow black and threatening. A hoarse voice shouted the ominous word, “spotter.” The cry was taken up and repeated by a hundred throats. Then Myles received a savage blow from behind. The crowd had recognized that he was not of them, and blindly argued that he must therefore be against them. The situation was a critical one, and Myles realized it.

He was now hemmed in so closely on all sides that to retreat would be impossible even had he thought of such a thing, but he did not. His one idea was still to get to the car, and under a shower of blows, that he warded to the best of his ability, or bore unflinchingly, he struggled forward. All of his strength, pluck, and skill, however, could not save him, and within two minutes he was borne to the ground by the sheer force of numbers, while some of his enemies fell on top of him.

At that moment there came a quick measured tramp of feet, a backward movement of the mob, and the crash of tough locust clubs. The police[70] were charging to the rescue of the brave young fellow. He struggled to his feet bruised, breathless, hatless, with clothing torn and covered with dust, but with unbroken bones and undaunted spirit.

“Who are you? and what do you mean by making such a row?” demanded the roundsman who led the charging party, as he laid his hand heavily on Myles’ shoulder.

“A reporter from the Phonograph, who was ordered to ride on that car, and means to if he can fight his way to it,” was the answer.

“I might have known it,” said the officer, with a resigned air. “You reporters do beat the world for getting us cops into trouble. The idea of a chap like you undertaking to fight that whole crowd! Nobody but a crank or a reporter would think of such a thing. It’s a good thing to carry out orders when you can, but it’s a better to use common-sense and not attempt to undertake impossibilities.”

“I was only trying to find out whether it was an impossibility or not,” laughed Myles.

While they thus talked the officer led his party of police back to the car. It had stopped while its defenders charged the mob, and now it again started[71] ahead. Hardly had it got into motion when, with a wild yell, the mob came charging back upon it, and with a tremendous crash the car was lifted from the track and hurled upon its side. It was a full minute before Myles succeeded in clearing himself from the wreck and again scrambling to his feet. As he was rubbing the dirt from his eyes, and thinking what a particularly lively occupation this business of reporting was, he heard a familiar voice call out:

“I say, new man—I don’t remember your name—why don’t you come up here? You can get an elegant view of the scrimmage.”