Title: The Chautauquan, Vol. 03, June 1883

Author: Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle

Chautauqua Institution

Editor: Theodore L. Flood

Release date: August 15, 2015 [eBook #49705]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Emmy, Juliet Sutherland, Music transcribed by

June Troyer and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

at http://www.pgdp.net

A MONTHLY MAGAZINE DEVOTED TO THE PROMOTION OF TRUE CULTURE. ORGAN OF

THE CHAUTAUQUA LITERARY AND SCIENTIFIC CIRCLE.

Vol. III. JUNE, 1883. No. 9.

President, Lewis Miller, Akron, Ohio.

Superintendent of Instruction, J. H. Vincent, D. D., Plainfield, N. J.

General Secretary, Albert M. Martin, Pittsburgh, Pa.

Office Secretary, Miss Kate F. Kimball, Plainfield, N. J.

Counselors, Lyman Abbott, D. D.; J. M. Gibson, D. D.; Bishop H. W. Warren, D. D.; W. C. Wilkinson, D. D.

| REQUIRED READING | |

| A Glance at the History and Literature of Scandinavia | |

| VII.—Swedish History from Charles XII. to Oscar II. | 487 |

| History of Russia. | |

| Chapter XI.—The Troitsa—Dmitri Donskoï—Vasili Dimitriévitch, and Vitovt of Lithuania | 489 |

| Pictures from English History | |

| IX.—The Sorrowful Queen. | 494 |

| SUNDAY READINGS. | |

| [June 3.] | |

| Religion in Common Life—Part I. | 496 |

| [June 10.] | |

| Religion in Common Life—Part II. | 498 |

| [June 17.] | |

| Religion in Common Life—Part III. | 500 |

| [June 24.] | |

| The Eleventh Commandment—Manners | 501 |

| Chinese Literature | |

| On the Origin and Nature of Filial Duty | 503 |

| The Improvement of One’s Self | 503 |

| Sentences from Confucius | 503 |

| A Ballad on “Picking Tea in the Gardens in Springtime.” | 503 |

| The Mender of Cracked Chinaware | 504 |

| Japanese Literature | |

| Translations from Japanese Mythology | 505 |

| Japanese Proverbs | 506 |

| Raiko and the Oni | 506 |

| Deliverance: Nirvana | 507 |

| June | 507 |

| Taxidermy | 507 |

| Gymnastics | 508 |

| Etching | 509 |

| The Two Sowers | 509 |

| A Tour Round the World | 510 |

| Art of Conversation | 514 |

| Cheerfulness Taught by Reason | 514 |

| Tales from Shakspere | |

| All’s Well That Ends Well | 515 |

| The Last Snow of Winter | 518 |

| Conjurors | 518 |

| The Influence of Wholesome Drink | 519 |

| C. L. S. C. Work | 522 |

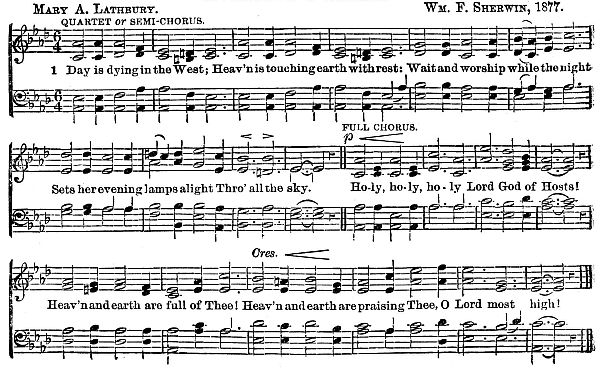

| C. L. S. C. Song | 523 |

| Pacific Branch C. L. S. C. | 523 |

| C. L. S. C. Testimony | 524 |

| A Letter from England | 524 |

| Local Circles | 525 |

| Local Circle Lectures | 529 |

| Questions and Answers | 530 |

| Outline of C. L. S. C. Studies | 531 |

| C. L. S. C. Readings For 1883-84 | 531 |

| Ardor of Mind | 532 |

| The Song of the Robin | 532 |

| With Agassiz at Penikese | 533 |

| The Coming of Summer | 536 |

| In Some Medical By-Ways | 537 |

| Death’s Changed Face | 537 |

| Chautauqua Ripples | 538 |

| Chautauqua School of Languages | |

| Hints to Beginners in the Study of New Testament Greek.—III. | 539 |

| Editor’s Outlook | |

| The Chautauquan | 540 |

| The C. L. S. C. Course of Study for 1883-84 | 540 |

| The English-Irish Troubles | 540 |

| Prohibition in Politics | 541 |

| Editor’s Note-Book | 541 |

| Editor’s Table | 543 |

| C. L. S. C. Notes on Required Readings For June | |

| History and Literature of Scandinavia | 544 |

| History of Russia | 545 |

| Pictures from English History | 546 |

| Notes on Sunday Readings | 546 |

| Notes on Chinese Literature | 547 |

| Notes on Japanese Literature | 547 |

| Notes on Text-Book 34 | 548 |

| Lecture by Artemus Ward | 543 |

In the poem of Axel some of our readers may suspect that Tegnér has idealized the exploits and daring of Charles XII. and his enthusiastic guard of honor. Doubtless some allowance must be made for the exaggerations of time, but that Charles XII. stands almost alone in history for indomitable resolution and reckless bravery, seems clear. To estimate his career and character in a word we can not do better than turn to the last pages of Voltaire’s history of his life, from which we quote the following:

“Almost all his actions, even those of his private life, bordered upon the marvelous. He is perhaps the only one of all mankind, and hitherto the only one among kings, who has lived without a single frailty. He carried all the virtues of heroes to an excess at which they are as dangerous as their opposite vices. His resolution, hardened into obstinacy, occasioned his misfortunes in the Ukrane, and detained him five years in Turkey; his liberality, degenerating into profusion, ruined Sweden; his courage, extending even to rashness, was the cause of his death; his justice sometimes approximated to cruelty; and during the last years of his reign, the means he employed to support his authority differed little from tyranny. His great qualities, any one of which would have been sufficient to immortalize another prince, proved the misfortune of his country. He never was the aggressor; yet in taking vengeance he was more implacable than prudent. He was the first man who ever aspired to the title of conqueror, without the least desire of enlarging his own dominions; and whose only end in subduing kingdoms was to have the pleasure of giving them away. His passion for glory, for war and revenge, prevented him from being a good politician; a quality without which the world had never before seen any one a conqueror. Before a battle, and after a victory, he was modest and humble, and after a defeat firm and undaunted; rather an extraordinary than a great man, and more worthy to be admired than imitated.”

After the death of Charles, who had never thought of designating a successor, two claimants for the throne came forward; his sister Ulrika and his nephew Carl Frederick. By intrigue with the nobles the former secured the prize, promising to give up the almost absolute power that had been wielded by the Vasa line. Two years later Ulrika resigned the sovereignty to her husband, Prince Frederick of Hesse. One of the most distressing chapters of Swedish history now begins. Frederick I. was indolent and indifferent to the claims of his position. When an energetic policy might at least have protected the country, he looked on in apathy while party strife within and greed of conquest from without nearly sundered the kingdom. Russia obtained Ingermanland, Esthonia, Livonia, and part of Finland, and in effect controlled the territory which it spared. After thirty years of such virtual interregnum the throne was again mounted by an alien prince, Adolf Frederick of Holstein. This was going from bad to worse. The new Frederick was weaker, if not more indolent than his predecessor, and in the twenty years of his authority the nation reached the bottom of its helplessness and insignificance. In 1771, Gustaf III., son of Adolf Frederick, was crowned. None of the father’s qualities appear in this son. Born on Swedish soil, though of alien blood, he had early imbibed the spirit of the Vasa monarchs, and set out to rival their achievements. He at once overthrew the power of the council and assumed again the reins of irresponsible authority. He became involved in a war with Russia, then ruled by Catherine II., who effected an alliance with Denmark against him. By the influence of Prussia and England Danish co-operation with Russia was abandoned. After a few skirmishes Gustaf was induced to close the campaign without accomplishing the results attempted. It was clear the odds were too great.

Sweden, now that all foreign differences were adjusted, was in condition to enter upon a long period of prosperity. But to the restless temper of the king, peace was impossible. He was ever entertaining great schemes, and laid plans even for interfering with the course of events in France, hoping to set aside the course of the revolution and set up again the authority of the Bourbon family. Money was solicited from the Diet for this purpose. The wildness of such a project when the country was groaning under an accumulated burden of debt, caused a strong revulsion of feeling against the king. A conspiracy was formed to remove him, and on the 16th of March, 1792, while attending a masked ball in Stockholm, he was assassinated.

Gustaf III. left as heir to the throne an only son, who was declared king at the age of fourteen, under the title of Gustaf Adolf IV. During the four years that remained of his minority the country was entrusted to the regency of his uncle, Duke Charles of Sodermanland. On attaining his majority, Gustaf IV. was crowned, and assumed direction of the government. The people rejoiced again in the accession of a prince of unusual promise, but they were again doomed to disappointment. The king refused to continue the policy inaugurated by his uncle, of supporting the new order of things in France. To the quality of wilfulness he soon united that of fanaticism. Napoleon was to his mind unmistakably the Great Beast foretold in the Book of Revelations. He, therefore, without duly weighing the consequences,[488] joined the triple coalition against France. This step led to numerous evils. Taking the field in person, he matched his strength against Bernadotte, who took possession of Hanover. After the battle of Austerlitz, and the peace of Tilsit, the insane King of Sweden attempted to continue the war alone. Despoiled of Pomerania by the French, he was next to rouse the ire of Russia and lose Finland. Even England, who had come to his rescue, abandoned all hope of his administration and recalled her troops. The nation was in despair; revolution was again its only hope. A project was formed to place the crown in foreign hands, and offer of it was made to the English Duke of Gloucester. The rumor of an intended deposition spread, and the people hailed it with enthusiasm. Without waiting to settle the question of who should take the crown, a body of troops marched from the borders of Norway to the royal palace in Stockholm, and in the name of the nation seized the person of the king. On the 29th of March, 1809, he signed his abdication, henceforth to be an exile and a wanderer. He assumed the name of Count Gottorp, made a brief sojourn in England, whence he repaired to the Continent, and finally died in 1837 at St. Gall, in Switzerland.

Duke Charles of Sodermanland, after the expulsion of his nephew, was again made regent, and later proclaimed king of the realm, under the title of Charles XIII. He was the son of the sister of Frederick the Great of Prussia, and had long served the country in the position of chief-admiral. Being without an heir, with the consent of the states, Prince Christian of Holstein-Sonderburg was designated as his successor. The latter, however, died suddenly the same year, while reviewing troops near Helsingborg; not without suspicion of poisoning. The question of the succession was again opened, and finally settled in a manner very unexpected. The states at first proposed to adopt the brother of the late prince, and one Count Mörner was dispatched to Paris to obtain the consent of Napoleon. The young nobleman, however, had thought of a more romantic plan, which was no less than the adoption of one of Napoleon’s famous marshals for the vacant throne. His choice was Bernadotte, who, we have seen, had served his master in a campaign in the North. Napoleon gave an unwilling consent, and Jean Bernadotte was declared Crown-prince of Sweden.

Bernadotte repaired at once to Sweden and assumed control of the national defenses. It was a critical moment. Sweden had for some time been under the control of France, which was now alienated by the Swedish choice of sovereign. Napoleon forced Sweden into a war with England, while hostilities were also threatened by Russia and Denmark, and seized Swedish Pomerania. Bernadotte, however, possessed a knowledge of diplomacy as well as of the art of war. He formed with Alexander of Russia a secret treaty of alliance, and secured promise of the annexation of Norway. Napoleon soon after declared war against Russia, and for assistance offered Bernadotte a large increase of territory. The fate of Europe lay in Bernadotte’s decision. He declined to join his former master, and strengthened the heart as well as hands of Alexander for the coming struggle. After the retreat of Napoleon from Moscow, Bernadotte failed to support the allied powers with the co-operation they had expected, and seems to have cherished for many years the hope of being nominated the successor of Napoleon.

The first fruit of the downfall of Napoleon was the annexation of Norway. This was not done without resistance. England and Russia were pledged to support the change; and in 1814 a Swedish fleet moved upon the seaboard towns, while an army crossed the border and expelled the Danish prince. From this year each nation legislating by a different congress has been governed by a common king. This king continued to be, in name, the chief-admiral who had been crowned Charles XIII, until 1818. In this year occurred his death, and Crown-prince John Bernadotte was crowned king, with the title of Charles John XIV. As a civil administrator he was less successful than as a commander. He had been bred a warrior, had been too long accustomed to absolute command, to accommodate himself easily to the changed conditions of peace. He distrusted reform, and reposed the security of his throne rather in the higher than the lower orders of the people. Yet he gave the country freedom from foreign greed, relief from the old burdens of taxation and debt, thus enabling capital and industry to develop the resources of the country. In the quarter of a century during which he kept the throne, Sweden and Norway, in the development of their resources, kept pace with the most prosperous nations of Europe.

Charles XIV. died in 1844, at the ripe age of eighty, and his son, Oscar I., succeeded. He was a man in sympathy with the new order of things, and gave the people immediately the reforms they had so long desired. His father had never succeeded in making himself a Swede, but lived a foreigner among his people till the last. Oscar early set himself the task of adopting the language and manners of his new country, and in 1818 entered the University of Upsala, from which he graduated with distinction. He was an expert musician, and composed several pieces, including hymns, ballads, and even an opera, which are yet mentioned. As he advanced in years he gave increased attention to more serious subjects, interesting himself especially in the problems of education, prison discipline, and the national policy. In the last he was opposed to the close alliance his father maintained with Russia, and when he came to the throne terminated the somewhat galling relations hitherto maintained with that power. His thorough sympathy with whatever was truly national made him exceedingly popular. When the Crimean war broke out in 1855, Oscar joined France and England against Russia, the old foe of the Swedes, and at its close entered into a compact with Denmark for the mutual protection of the two kingdoms. He married Josephine of Leuchtenburg, granddaughter of the Empress Josephine. To the oldest of his four sons he resigned the government in 1857, his health having failed. His death occurred two years later. He will be remembered as one of the most conscientious and enlightened sovereigns of modern times.

Charles XV., who, as regent, had relieved his father of the cares of state, was careful to continue the liberal policy of the preceding reign. The only question which disturbed the politics of the time had reference to the constitution of the Riksdag, or congress of the nation. This had consisted of four chambers, representing the four orders of the nobles, the clergy, the citizens, and the peasants. In the adjustment it was agreed there should be two chambers only. The members of the first chamber were to be elected for nine years by the Landsthing of the province in conjunction with the electors of the larger towns, and to receive no pay. The members of the second chamber were to be elected for three years, being classed as town and country deputies, and to receive compensation from the government. King Charles was a man of refined sensibilities, and amused himself at times with poetry, a volume of which is extant. He was always opposed to capital punishment.

The death of this king occurred on the 18th of September, 1872. He left only a daughter, wife of Prince Frederick, of Denmark; his brother, therefore, was crowned as Oscar II. He has worthily continued the policy of his predecessors, and gratified his people by many reforms. He is also a man of liberal culture and literary tastes, and has given his countrymen a translation of Goethe’s “Faust.”

By Mrs. MARY S. ROBINSON.

The traveler who wends his way toward “Holy Mother Moscow,” meets with many a pilgrim journeying to pray before the shrine of a saint, founder of a community first of all religious, but industrial and scholastic also, whose buildings are seen from afar, and whose inhabitants are numbered by thousands. This place, whose revenues, increased by the voluntary offerings of multitudes of the faithful, are comparable with those of the imperial household, is the Troitskaia-Sergieva, the Trinity-Sergius Monastery, one of the four Lauras, or monastic establishments of the first order; that of Alexander Nevski, at Petersburg, of Solovetski by the Frozen Sea, and the Pecherski, or the Catacombs at Kief, being the other three.

In the days of Simeon the Proud, son and successor of Kalita, Sergius, the Benedict of the Russian Church, withdrew from the stirring, tempting life of the capital to dwell apart and foster his religious aspirations, selecting for his retirement a spot some sixty miles from Moscow, within an untrodden wood, where for a long period his only companions were the bear and the beaver; his food, herbs and the wild honey, always abundant in the hollow trees of Russian forests. In those times when the benignant influence of Christianity was scarcely felt in many classes of society, the spiritually minded, who valued above all other possessions their simple virtue and a good conscience, were drawn to a secluded and exclusively religious life; hence, as the years passed, numbers of sincere self-denying souls gathered about the son of the Rostof boyar. His moral wisdom and impartial position caused him to be consulted by the great and powerful on occasions momentous for themselves, or for the welfare of their people. Warriors sought his blessing upon their enterprises, and princes asked his counsel upon affairs of state. The particular privileges accorded to ecclesiastical institutions, the security of their estates, and the industrial instruction imparted by the monks to the common people, drew large numbers of these latter to the region of the monastery, whose work-shops and glebes were the most prosperous of the country, and whose industries were uninterrupted by the continual ravages of war. Cleanly kept, enclosed within walls of huge thickness flanked with towers, the inhabitants of Troïtsa were exempt from the calamities of pestilence and fire. Having many dependents living in communal villages,—in the days of serfdom it possessed a hundred and six thousand serfs, not to mention the monastic establishments, some thirty-two in number, that were offshoots from it,—its peace-loving inhabitants could defend themselves and their people in times of emergency. The fires of national and religious independence burned upon altars within its gates that were never reached by papal Pole or pagan Tatar, although it was more than once besieged. The most cruel of Tsars, the wicked Ivan Fourth, appropriated money and men for the building of half its stately structures. Hither came Peter the Great for rest of soul during the intervals of his journeys and campaigns; and Catherine Second, putting aside her cares, abandoning for the time her excesses, to commune with the Sovereign before whom emperors and empresses are but sinful, perishing, human beings. From the beginning, pilgrims from all the grades of life have journeyed to the shrine[A] of the saint, who remained to his latest day a simple, laborious servitor, in no way exalted by the honors put upon him, or by the material increase of his community. In later years the Metropolitan of Moscow has been the archimandrite, or abbot, of the monastery; a dignitary who, because he restrains the souls of men, is revered with the solemnity that belongs to those who represent exclusively that spiritual element in human life which, though not of this world, has ever been an inalienable force in the shaping of its destinies.

Simeon acquired his surname by reason of his haughty demeanor to the other princes; but he maintained cordial relations with the khan, to whom he sent many costly gifts, for whom he raised large revenues, and from whom he received the pay of a farmer-general. He assiduously cultivated the industries and arts that his father had encouraged. We read of bells for the cathedrals being cast in his reign, and imposing paintings for certain of the churches. His will was written on paper (1353) instead of the parchment that had previously been used for purposes of writing.

His enriched, well-ordered state passed to the care of his brother, Ivan Krotki, the Debonair, or Gentle, a prince too unlike his predecessors to govern the realm they had formed by repression and a vigorous assertion of power. The elements of turbulence broke forth anew. Novgorod, that had paid a contribution to Simeon, who on his part had confirmed its liberties, closed its coffers and elected a prince with the freedom of former years. The military governor of Moscow was murdered, nor was his death avenged. The patriarch of Constantinople put forward a rival to the holy Alexis, primate of the capital, and who was immeasurably loved and revered by the Muscovites. So unsuited were the virtues of this prince to his place and time, that at the close of his six years’ reign, Dmitri of Suzdal obtained the title of Grand Prince (1359), and made his solemn entry into Vladimir, to the threatened subordination of the principality of Moscow. Alexis, the primate, devoted himself to the education of Ivan’s children. When the eldest, Dmitri, was twelve years old, at the instance and by the influence of the faithful bishop, “whose prayers had preserved the life of the khan, and had strengthened his armies,” the young prince obtained the right to bear rule from his master at Saraï. Thus early was the government laid upon the shoulders of this descendant of the Nevski and of Monomakh; a ruler who was chivalrous without cruelty, devout without ostentation; who not only acquired but was voluntarily and gladly accorded the supremacy over his kinsmen and his realm, and who by his personal nobility did much toward preserving his people from the debasement of their conquerors.

Dmitri, assured of his strength, ventured to re-assert the Russian claim to Bolgary, the extensive region east of the Volga, where he compelled the Tatars to pay him tribute and to accept Russian magistrates for their settlements, some of which had grown to sizable cities. Later he gained a brilliant victory over a lieutenant of the khan, Mamaï, in the province of Riazan. “Their time is past, and God is with us!” he exclaimed in the triumph of the hour. Two years later, Mamaï having silently gathered an immense and motley host, aided too by the intrigues of Oleg of Riazan, who, restive under the power of his neighbor, had made friendly alliances with the Tatars and with Lithuania, dared to defy the strength of a now nearly united realm. For Dmitri had summoned all the princes, and these came with their contingents, crowding the Kreml and the city with their drujinas and troops, and received with acclamations by the people.

Never had such an army been seen in Russia: the safest estimates number it at a hundred and fifty thousand, including seventy-five thousand cavalry. Prince Dmitri strengthened his soul in prayer at Troitsa, where he obtained in the name of the God of Nations the blessing of Sergius, and was given two monks, brave men, to go forward with him and his host. As this embodied strength and hope of the nation moved toward the banks of the Don, it was threatened by the Lithuanians from the west, and the Tatar hordes from the east. A message from Sergius favoring an advance, decided the councils of war; and when the passage of the river was effected, the army formed for battle on the plain of Kulikovo, the Field of Woodcocks, westward of the Don and southward of Riazan (1380). A mound of earth was cast up for the general-prince to witness the movements of the action; and as he stood upon it, the army in one loud voice of unison offered the prayer: “Great God, grant to our sovereign the victory.” Dmitri, beholding the marshaled ranks, and knowing the solemn fate that was soon to dim their splendor and disorder their stately array, knelt in the sight of all the troops, and with uplifted arms besought the divine protection for Russia. As he rode before the men, he proclaimed: “The hour for the judgment of God is come,” and when the alarum had been sounded, he stood ready to lead the first advance. “It is not in me to seek a place of safety,” he said to those who would deter him, “when I have exhorted these, my brethren, to spare not themselves for the good of the land. If I am cut down, they and him in whom we confide will protect our Russia.”

The battle was long and strenuously contested; for in respect of the future, it was to be decisive for or against the ascendency of the Asiatics, and the self-government of the Russian states. A breach had been made in the drujina of the Grand Prince, when his trusted kinsman Vladimir, and the watchful Dmitri of Volhynia came from their appointed positions to his support. The right, left, and center of the host were woefully thinned, but they were not repulsed. Mamaï, from the height of a funeral mound, saw his men[491] desperate, falling and giving way, as the afternoon waned, and covering his eyes, exclaimed: “The God of the Christians is all-powerful!” The Mongols in trepidation and wild disorder were pursued in all directions; a hundred thousand of them lay dead or shrieking in death agonies upon the plain; nor was the Russian host hardly less depleted. When Vladimir, who won the distinction of “the Brave,” in this action, planted his banner upon a mound, and with signal trumpets rallied the remnant of the men, princes, nobles, soldiers obeyed the call; but Dmitri was not among them. After a long search he was found, faint, bleeding, his armor shattered. The whispered words of good cheer, the banners waving before his dimly opening eyes, caused his pulses to beat again, and as he lay surrounded by his captains, his low prayer of thanksgiving was heard between the huzzas of the weary yet rejoicing ranks. From that day forward he was Dmitri Donskoï—of the Don—for by its waters he had broken the tradition of servitude; under his leadership the Russian heart had been rekindled to its ancient courage; the Russian manhood had been restored. As his litter was borne from the field, he saluted his fallen comrades in arms: “Brothers, nobles, princes, here is found a resting place for you. Here, having offered yourselves for our land and faith, you have passed to a peace nevermore disturbed by conflict. Hail and farewell.”

Such was the battle of Kulikovo—the reparation of what was foregone at the battle of the Kalka.[B] The nation, however, had still much to endure from, and was essentially modified in its manners and customs by the people who had been its masters. Four centuries or more were required for the European Mongols to adopt the customs of Russian civilization, and to render them sufficiently instructed to contribute to the prosperity of the empire. The pestilence of the fourteenth century, the Black Death, together with the dissensions of the khans, impaired the strength of the Horde, which rallied, however, under Timur Lenk, the Lame, or Tamerlane, as he is commonly named, a direct descendant of Genghiz on the maternal side[C]. Toktamuish, one of his generals, took possession of the country from the Volga to the Don, and turned his horses’ heads toward the north. The counsels of the princes were divided. Dmitri would not that the thousands buried at Kulikovo should have perished in vain: but the principalities were in no condition for the further maintenance of war. In the hope of help from the north, Dmitri withdrew to Kostroma, above Moscow. The Mongols laid siege to his capital, but finding they could make no breach in its defenses, entered into negotiations, or affected to do so, and watching their opportunity, surprised the gates. Then ensued the devastation of former days. The precious archives of national history, the ancient stately buildings, were all consumed: the citizens were massacred without distinction or mercy. “In one day perished the beauty of the city that had overflowed with riches and magnificence,” writes Karamsin; “smoke, ashes, ruined churches, corpses beyond the counting, a frightful waste, alone remained.” Dmitri, like his ancient kinsman, Iuri,[D] returned to deplore the ruin of the richest portion of his country, for which, in vain, as it appeared, he had labored and suffered from his youth up. The prince’s son, Vasili, was detained as hostage at the Horde, but escaped after a three years’ captivity. Many more were required for the rebuilding of the city. The Tatar baskaks were again established among the slowly reviving communities. But incapable of solidarity, these people were unable permanently to subdue the dwellers in cities, or to destroy a firmly compacted state. The invasion of Toktamuish closed the drama of their conquests in Europe.

Dmitri lived some years after this overthrow of his hopes, but continued to the last, strong and assiduous for the up-building of his principality. The walls of the Kreml[E] were rebuilt this time not of oak, but of stone; churches and fortified monasteries were reared within and beyond the city walls. Not less necessary than his own dwelling is the house of worship to the religious Russian. Kief at one time had four hundred churches, or nearly fifty more than Rome, and Moscow, though almost entirely rebuilt since 1813, encloses a hundred and seventy within its walls. To the west of the Grand Principality, extending to the Urals, the stone girdle of Eastern Russia[F], lay the vast territory of Permia, or Perm. A monk, Stephen, went forth into its unexplored wastes, won the hearts of some of its people, confuted their sorcerers, overthrew their idols, notably one much adored, the Golden Old Woman, who held two children in her arms—established schools, and in time was made bishop of the diocese he had discovered; wherein finally he was put to death, winning thus the honor of the first Russian missionary and missionary martyr, and enduring reverence for his mortal remains, entombed in the capital of his country.

In the south, the intrepid, maritime Genoese formed colonies at Kaffa and Azof, connecting links between Russia and the West. Among the articles brought into the country at this period were cannon. Parks of artillery were used in the army, in the last year of the Donskoï’s reign.

His personel, as retained by the historical paintings representing the scenes of his career, is that of a serious, steadfast man, patient and brave, intent upon his affairs, without self-consciousness, capable of that tempered happiness that attends long-continued exertion. His dark hair falls upon vigorous shoulders; a full and manly beard does not conceal the firm outlines of the lower part of the face. The eyes are touched with care, their region deeply traced with marks of toil; a seamed, broad forehead sustains the weight of its crown. They that looked upon this prince must have been reminded of the Presence that strengthens and subdues the souls of all good men. Dmitri, Alexis, and Sergius, the ruler, the pastor, and the saint, made the titles “Holy Russian Empire,” “Holy Mother Moscow,” not wholly insignificant, not entirely a sad irony upon the conduct of those who wrought by manifold means toward the compacting of the nation.

A bylina, or historical ballad, chants the last scene in this eventful, care-laden life. In the Uspenski Sobor, “the Holy Cathedral of the Assumption, Saint Cyprian was chanting the mass. There, too, worshiped Dmitri of the Don, with his princess Eudoxia, his boyars, and famous captains. Suddenly ceased the prince to pray: he was rapt away in[492] spirit. The eyes of his soul were opened in vision. He sees no longer the candles burning before the sacred pictures; he hears no longer the holy songs. He treads the level plain, the field of Kulikovo. There, too, walks Mary, the Holy Mother: behind her the angels of the Lord, angels and archangels, with swinging lamps. They sing the pæans of those who fell upon that earth, beneath the blade of the pagan. Over them she, too, lets fall the amaranth.—‘Where is the hero who stood here for his people and for my Son? He is to lead the choir of the valiant: his princess shall join my holy band.’ * * * * * * * In the temple the candles burned, the pictures gleamed, the precious jewels were bright. Tears stood in the grave eyes of our prince. ‘The hour of my departure is at hand,’ he said. ‘Soon I shall lie in unbroken rest; my princess shall take the veil, and join the choir of Mary.’” For from the days of Anne, daughter of Olaf of Sweden, and consort of the great Iaroslaf (1050), the wives of the Grand Princes, following the custom of the widowed empresses of Byzantium, had retired to a convent upon the death of their lords.

Dmitri, by compact with a number of his kinsmen, princes, had effectually secured the Muscovite succession to the eldest son, thus abolishing the old Slavic law, whereby the elder, were he son or brother of the deceased prince, entered upon it. So entire was the confidence, so genuine was the affection that he had inspired in the hearts of his countrymen—for he was, in effect, the Russian Washington—that his son Vasili (Basil) received upon his shoulders the “collar” and burden of government (1389) without opposition. His reign of thirty-six years proved that he had inherited his father’s skill and good fortune, if not fully his greatness of mind. The Donskoï had secured the virtual consolidation of the adjoining State of Vladimir, or Suzdal, with that of Moscow. The far-reaching territories of Novgorod the Great, too, were gradually being regarded as a part of the Grand Principality, notwithstanding frequent demonstrations of resistance from its people, who yet paid tribute to, and had chosen, from motives of policy, a succession of grand princes for their princes. The republic, after its humiliation by the Mongols, had warily parried the Muscovite encroachments by frequent alliances with Lithuania,[G] a realm much larger than organized Russia in the fourteenth century—whose tribes had been united by a succession of powerful native chiefs.

By the charter of Iaroslaf the Novgorodians were accorded the right of choosing their sovereign; hence, when circumstances rendered a Lithuanian prince desirable for their protection against a Muscovite one, they obtained him by election. But affinities of race, religion, and a common history, were too strong to permit a permanent union with a foreign power.

From the Horde, Vasili, by bountiful payments, procured an iarluik for seven appanages, including Murom, Suzdal, and Nijni or Lower Novgorod—all belonging to his less wealthy kinsmen, who were offered their choice of becoming his dependents, or of dying in captivity or exile. The succession of the eldest son had procured the elevation of the nobles of the grand prince to a subordinate princely rank and power. In view of this fact, perhaps, the citizens of Nijni-Novgorod voluntarily surrendered their last titular prince, Boris: for if a Muscovite boyar could become a prince, and if the Muscovite grand prince could work his will with the khan, why resist this ever growing, ever more dominant power? Accordingly, amid the clangor of the bells of these ancient, hitherto independent cities, the son of the Donskoï was proclaimed their sovereign.

Arrogant and overbearing to his kinsmen, the native princes, the sagacious Vasili maintained amicable relations with the Tatar on the east, and the Lithuanian on the west, notwithstanding that he had been hostage and prisoner at Saraï´, that he had escaped thence as a fugitive, and that his domains were twice invaded by the hordes of its peoples. Tamerlane, at this time at variance with his former general, Toktamuish, harried the dismembered empire of Kipchak and moved westward into Russian boundaries, destroying the people by the sword, and their possessions by the fire-brand. Moscow was again in peril: in its streets and its homes were revived with fearfulness and trembling tales of the destruction of 1382. The Tatars were sixty leagues away at Elets on the Don, a town which they razed. Its ancient monastery of the Trinity has four memorial chapels commemorative of the citizens that perished at the time—all the place contained, save a few fugitives.

There the wild horsemen suddenly turned southward and rode into Azof, the emporium of the wealth of merchants who had come thither from Cairo, Venice, Genoa, Catalania, and the Biscayan country. Fresh from the hoarded treasures of Bokhara and Hindustan, and having in expectancy the wealth of Constantinople and of the Nile cities, they were allured to the regions of the south in preference to the toilsome way over steppe and through forest, to the peopled country of the north.

But they remained not long absent. Vitovt, the vigorous Lithuanian chief and prince, took the opportunity to raise a crusade against the never resting, ever appearing, all-devouring Tatar. To this end he obtained an army from the King of Poland, five hundred of “the iron men,” the Sword Bearers, numbers of the Russian princes with their contingents, whose ancient kinsmen had borne the standards at Kulikovo, and not least, Toktamuish, the exiled khan, fugitive from Tamerlane; for in nearly all the wars carried on east of Hungary and Poland after the thirteenth century, the European Mongol had his place and his active part.

By the river Vorskla, a branch of the Dnieper, a hundred and eighty miles southeast of Kief, the crusade of Vitovt was brought to a disastrous closing; the Tatar general, Ediger, friend and ally of Temir Kutlu, khan of the invading host, coming to the help of his people at the crisis of battle, and inflicting an overwhelming defeat upon the hosts of the Lithuanian. The message of Temir Kutlu before the closing of the armies is suggestive of the precarious fortunes of the khans, still barbaric and quite as roving as those had been who crossed the European boundaries in 1224. He demands the rendition of “my fugitive Toktamuish. I can not rest in peace knowing that he is alive and with thee. For our life is full of change. To-day a khan, to-morrow a wanderer; to-day rich, to-morrow without an abiding place; to-day friends only, to-morrow all the world our foes.” Ediger’s opportune arrival with a strong force confirmed the resolution of the khan against yielding to the demands of Vitovt, who offered him the alternative of being a “son” or a slave. The Vorskla proved for him and his people another Kalka;[H] the Tatars followed hard after the remnant of the Lithuanian ranks, and again plundered Kief, and desecrated its sacred Monastery of the Catacombs.

Between the growing kingdom of Poland and the principality of Lithuania, on the west, and the locust-like swarms of Mongols unexpectedly appearing ever and anon from beyond the Asiatic boundaries, Moscow and the Russian States generally, were ever liable to surprise and to the danger of being crushed, from the thirteenth to the sixteenth century. Ediger, elated by his success over the combined forces of Vitovt, caused the report to be spread about, that he should carry the war into Lithuania: at the same time, with the secrecy[493] and celerity characteristic of his race, he appeared at the front of his horsemen and wagons within the boundaries of the Grand Principality. Vasili withdrew to Kostroma (1408), as his father Dmitri had withdrawn on a similar emergency, and left the city to the defense of Vladimir the Brave. Again was all the surrounding country harried, the towns burned, the farms and fields destroyed, the transport of provisions stopped, and a dense population brought to the verge of starvation by the terrible Tatar. But just before the situation became one of extremity, reports of divisions and dangers at the Horde, compelled Ediger to raise the siege. He sent a haughty message to the Kremlin, demanding tribute from the citizens, which he obtained to the amount of three thousand roubles, a sum equivalent to not less than thirty thousand dollars in our day. The sentinels who looked forth from the embrasures of the citadel, were glad that at any price could be purchased the sight of the hordes darkening the horizon with their disappearing.

Vitovt’s uncle, Olgerd, had been ally, by marriage and in war, with one of the Mikhails of Tver, successor of that prince whose martyrdom we have narrated.[I] Thrice during the reign of the Donskoï, had Olgerd led his brother-in-law, Mikhail, up to the walls of Moscow; but the prudence, both of the offensive and defensive leaders, withheld them from a decisive engagement that would prove certainly ruinous to the party who should suffer defeat. The same rôle was repeated between Vitovt and Vasili Dimitriévitch: this time with the result of a settlement of boundaries, in which Vitovt was careful to retain his valuable conquest, Smolensk. Before and after these conflicts, Vasili acquired certain cities from the State of Tchernigof, and large territories on the northern Dwina[J] in the territory of Novgorod, where the Good Companions, Bravs Gens, adventurous military bands, and commercial settlers, frequently came in conflict with Muscovite subjects, themselves pioneers upon the wastes and toward the ports or harbors of the far north. Vasili, pursuant to the policy of his dynasty, had recourse to undisguisedly severe methods to break the power of the free principality, and to incorporate it as much as he might, within his own. He obtained control of the Republic of Viatka, and framed treaties advantageous for Moscow with the princes of Tver and Riazan. These politic measures, with his unvarying entente cordiale with the dominant khan of the Horde, and the marriage of his daughter to the Greek Emperor, John Paleologus, strengthened his firm government, and widened the reputation of his industrious, wealthy, well-ordered state. Vitovt, whom we have named as the last of four chieftains, who secured unity to the tribes of his country, and sought to establish an independent nationality, did not lose courage nor ambition by the disaster at the Vorskla (1399). The Russian provinces of his country were under the religious direction of the metropolitan of Moscow. Vitovt procured that a learned Bulgarian monk should be installed metropolitan of Kief, in his time within Lithuanian boundaries—thus obtaining for his possessions a religious independence. He had designs also to free his country from its subordination to Poland; and by cultivating the friendship of Sigismund (1429), emperor of Germany, he obtained the favor of that monarch in helping him to become king of Lithuania. His court at Troki and Vilna was regal, in truth, in its magnificence, where the old man, an octogenarian, presided at long-continued festivals, at which seven hundred oxen, fourteen hundred sheep, and game in proportion, were consumed daily; where his grandson, Vasili Vasilèvitch, prince of Moscow, Photius, metropolitan of Moscow, the princes of Tver and Riazan, Iagello, king of Poland, the khan of the Crimea (one of the divisions of the ancient Kipchak), the hospodar of Wallachia, the grand-master of Prussia, the landmeister of Livonia, and embassadors from the Oriental empires, were entertained at his table as guests and friends. But his hopes of royalty were never realized. Even while the envoys of Sigismund were bringing him the scepter and the crown, the Pope, with whom the Poles had been conferring, compelled them to turn upon their path. The old chieftain survived this disappointment but a year; and with his life ended the attempts to create a distinct Lithuanian nationality, although for nearly a century thereafter it was governed by a prince of its own election. Early in the sixteenth century it was more definitely united with Poland, though still retaining its title of grand duchy, or principality. Its Russian provinces were Polonized; the descendants of Mindvog and Gedimin, Rurik and Iaroslaf, assumed the customs and language of the Polish nobility, and have retained them in the main, even under the repressive, reconstructive government of the tsars. Podolia, Volhynia and Kief are, in modern phrase, Ruthenian, occupied by a people homogeneous with those of Gallicia in Austria, with Southern Poland, and Northeastern Hungary.

With the increase of industries in Russia, an increase of coins became necessary. In 1420 Novgorod had its own mint, and its coins, stamped with the device of a throned prince, were twice the value of those of Moscow or of Tver. A Tatar coin, denga, from tanga, which signifies a mark, was current in the last named cities. For small transactions pieces of marten skins, squirrels’ heads, squirrels’ ears even—the latter less than a farthing in value—had been in vogue, but were gradually displaced, as was the giving of gold and silver by weight, in the larger transactions of commerce.

We have thus traced the development of the Russian state from its inception, to its compacting and centralization as the Grand Duchy, or Principality of Moscow, whose subsequent tsars brought under their sway most of the territory included within the boundaries of the modern empire. The writer of these chapters regrets that the limits of The Chautauquan prevent the presentation of the characters and careers of the two Ivans,—the Great and the Terrible—of Philarete, Peter the Great, Catherine Second, and other royal or noble personages whose genius, or whose moral force, have contributed in the later centuries to the elevation of the Russian Empire to a foremost place among the European powers. She can but entertain the hope, however, that this account of its rise and growth will awaken an inclination in the minds of those who have followed her narrative, to learn something further of a people whose aspirations for national freedom have been re-awakened and stimulated by our own history and prosperity; a nation whose tendencies and interests are largely similar, nay, are identical in the main, with those of the people of this republic.

We must not be surprised to find that even the highest works of God come to an end. Everything with an end, beginning, and origin, has the mark of its circumscribed nature in itself. The duration of a universe has, by the excellence of its construction, a permanence in itself, which, according to our ideas, comes near to an endless duration. Perhaps thousands, perhaps millions of centuries will not bring it to an end; but while the perishableness which adheres to the evanescent natures is always working for their destruction, so eternity contains within itself all possible periods, so as to bring at last by a gradual decay the moment of its departure.—Kant.

By C. E. BISHOP.

There was some perturbation in the C. L. S. Circle about “reading novels,” what time “Hypatia” was on the list. If the objectionable element in such reading is its improbability and contrariety to reason, those who are still opposed to it are warned not to read the life and adventures of Margaret of Anjou, some time queen of King Henry VI. It is not alone that her adventures were strange and her character remarkable, when truthfully described; she was the subject of romance writers of willful and, it is to be feared, malicious natures, only they called themselves “historians,” “chroniclers.” Their writings therefore are more objectionable than straight fiction, because they deliberately pervert truth and ask us to believe it. The best we can do with all the accounts of the Wars of the Roses is to weigh one story against another, and select that which pleases our reason or fancy better—just as a purchaser of novels does.

Margaret was born of “poor but proud,” royal parents, and was, at the age of fourteen, celebrated all over Europe for beauty, accomplishments, courage, et cetera. I fancy she would have been a good, average “American girl” of the present day, so you can fancy the sensation she created at the court of her uncle, the King of France, and afterward at that of her husband. She was a fascinator. The Earl of Suffolk lost his judgment about her when he went to negotiate the marriage, and he made so bad a bargain that he lost his head for it afterward; it was cut off in a mysterious manner in a skiff in the middle of the Channel. It was a sorry match for Margaret, after all. Her husband was grandson of the insane Charles VI. of France. When the hereditary taint did not show in Henry and he had lucid intervals, he was a weak man indeed; spending most of his time counting his beads and meditating; a good, simple-hearted man, just the one who ought not to have been the husband of Margaret of Anjou and King of England at that troublous time.

For, from the time when Henry, a babe of nine months, came, or was brought, to the throne, he had been the victim and alternate tool of the most selfish and unscrupulous noblemen in England arrayed in hostile factions. Into this den Margaret was brought at the age of fifteen, and before two years had passed she had become, to all intents, ruler of England. Henry from that time was as much counted out of the dark games of state-craft and priest-craft that cursed England as if he had been a holy relic. Intrigue, assassination, foreign aggression, and even servile insurrection under Jack Cade were brought to bear on her in vain. The people of England hated her because she was a foreigner, and visited on her all the sins of her court, the imperfections of her husband, their own miseries at home and their shame abroad for the loss of all the winnings of Henry V., Edward III., and the Black Prince. There was no real ruler, and the evil seeds of the usurpation of Henry IV. had ripened in a fearful crop of lawlessness and violence, high and low. There was “a man on horseback” to take advantage of all this evil conjunction of Margaret’s stars,—Edward, Duke of York, to-wit: He first plotted, then struck for the throne. The issue between Lancaster and York was made up, and the red rose and the white became symbols of blood and pale death.

It was while this ill-omened issue was crystallizing into action, that Margaret’s only child was born, and even this usual solvent of kingly troubles proved the culmination of her misfortunes and of England’s woes. The birth of the successor changed the issue from a quarrel of York with the court to a deadly enmity of York against Margaret and her son: they were one more block in his path. When the child was born (1453) his father had been for weeks in an idiotic daze—one of the fits he was subject to—not able to move or speak, or hear, or perceive anything; and the boy was some months old before his father could be made to know of his existence. Even this distressing affliction was made to tell against her, for, says an old letter writer, the “noble mother sustained not a little slander and obloquy of the common people, saying that he was not the natural son of King Henry, but changed in the cradle.” The poor mother repeatedly tried to vindicate her honor and strengthen the perilous position of her son by getting the father to recognize him. A letter of that day pathetically says:

“The Duke of Buckingham took the prince in his arms, and presented him to the king in goodly wise, beseeching the king to bless him: and the king gave no manner answer. Nathless, the duke abode still with the prince by the king: and when he could no manner answer have, the queen came in and took the prince in her arms, and presented him in like form as the duke had done, desiring that he should bless it. But all their labor was in vain, for they departed thence without any answer or countenance, saving only that once he looked upon the prince and cast down his eyes again, without any more.”

Is there a more touching tableau in all the pages of romance than this? Picture the young mother, with the discredited babe in her arms, watching, heart-sick, day after day and week after week, for the first flicker of the light of returning reason on that vacant countenance. But no sign of intelligence did the imbecile king give for over a year, and meantime York had himself appointed “protector” of the young prince, and all the barons stood by their castles in “armed neutrality,” waiting to see if the Lord’s anointed would not die and leave the crown to be wrestled for. Better for them, better for England, far better for Margaret, had he never wakened from his trance. When he did, York set his army in motion, and the War of the Roses was begun.

Battles, with alternating victories, supplemented by summary executions by the victors, followed each other. At length King Henry was taken prisoner and forced to a compromise, by which he was to reign for life and Edward of York was to succeed him. This treaty, which dishonored Margaret and disinherited her son, changed her. From that hour the mother became a lioness in defense of her young.

The mother’s struggles in her son’s cause during the succeeding sixteen years contain volumes of romance. The alternations of defeat and victory, of hope and despair, of triumph and exile in caves and woods, of intrigue with Lancastrian haters of the house of York, and of negotiations with foreign powers, sometimes fruitless, sometimes successful—at all times the highest exhibitions of diplomacy of the time—all seem, at this distance, to be strangely out of place in sober history.

The first battle of St. Albans, 1455, was followed by the Love Day when “all was forgiven,” as the advertisements say, and the best haters were paired off and marched to St. Paul’s to hear the grand Te Deum over the peace; the queen led by the Duke of York, Somerset and Salisbury, Warwick and Exeter, after the manner of the “Massachusetts and South Carolina” procession at the Peace Conference during the civil disturbance in our own country. This lasted a short time, and then came the battle of Bloreheath, where Henry for once showed a spirit “so knightly, manly and comfortwise that the lords and people took great joy,” deserted the Yorkists and compelled Warwick to flee the country. But before the middle of that summer (1460) Warwick and Edward were back with an army. The queen was beaten at Northampton; wondering King Henry was[495] taken prisoner, and a few days later placidly attended with his captors a service of thanksgiving for his wife’s defeat and his deliverance from his friends. It was now that the treaty was made disfranchising his own son. As for Margaret and the prince, they fled to Wales, where she was waylaid and robbed of her jewels, and escaped while her baggage was being rifled; thence crossing Menai Straits in a skiff, they reached Scotland.

Now occurred a tragic episode in keeping with all this strange, eventful history. King James of Scotland undertook to create a diversion in Margaret’s favor by besieging the border city of Roxburgh. One of the weapons of the besiegers was a rude cannon of that day, made of bars of iron heavily hooped like a barrel, and keyed with oaken wedges. King James wanted to “touch off” this dreadful “bombard” himself; it burst, a wedge struck him and he fell dead; and Margaret lost another ally. But the castle was taken, for the widowed Scottish queen came into camp leading the heir, a boy of eight years, the eldest of a family of seven children; her exhortations incited the assault that carried the castle. And then this widowed queen hastened to comfort and aid the worse than widowed queen who had fled to her realm. In eight days thereafter Margaret had 18,000 brave North-of-England men around her, and on the last day but one of the year 1460 she fought and defeated York at Wakefield. Thus within six months from the day when her fortunes seemed irretrievably ruined, and her husband and kingdom alike lost to her, she had the bleeding head of her antagonist, the Duke of York, stuck up over the gate of his own city of York. So it is said: but so it is contradicted. Here comes in the contemporary romancing. In this scene Shakspere’s genius has blackened the name of Margaret of Anjou, as it did that of another French heroine of this epoch, Jeanne d’Arc; he was English enough to always hate the French, and especially French heroines.

Margaret marched toward London, and encountered the King-Maker, who had come out as far as St. Albans with the captive royal imbecile at the head of his forces. Warwick was beaten and Henry fell a captive into his wife’s hands. There was a touching family re-union on the battlefield, and the king knighted his son, who, though only seven years old, had acted as much like a “lion’s whelp” as the Black Prince had done at Cressy.

But there was another boy in the field, the young duke of York, aged nineteen, to take up his father’s work and avenge his father’s death. This boy threw himself into London, closed it against Margaret, cut off her supplies, and just fifteen days after the victory of Wakefield it was responded to by cries of “Long live King Edward!” which hailed young York’s accession to the throne as Edward IV. The fatal battle of Touton followed the same month—a remarkable tragedy by itself. It was fought in the midst of a furious snow storm, which blinded the Lancastrian archers. Here Warwick is pictured as redeeming the day by dismounting and stabbing his horse, to demonstrate the impossibility of retreat to his retainers; drawing his sword and kissing the cross on its hilt he cried: “I live or die here. Let those who will turn back, and God receive the souls of all who fall with me.” The battle lasted all day; the slaughter of the defeated Lancastrians all the next day—for Edward had proclaimed no quarter. Such was the spirit that had now infected both sides in this fratricidal strife.

First to Scotland, and then to France, Margaret and her precious charge went, imploring aid. But chivalry was now on its last legs. However, she did get a small force from Louis of France, on promising to give up to him Calais when she should regain England, and with this she landed in Northumberland in October, 1462; but the elements again fought against her; a sudden storm shipwrecked the expedition and the royal party barely escaped in a small boat to Berwick, Scotland. Months of suffering, wandering and hiding followed. A single herring makes a meal for the royal family! She is set upon by a band of robbers in a wood and makes her escape while they are fighting over her jewels; she is lost in the forest, into whose depths she has fled blindly, and is suddenly stopped by another robber, sword in hand, to whom Margaret resolutely says, “My friend, protect the son of your king!” The supposed robber is a Lancastrian noble in hiding like herself and he shelters the royal guests for some days in a secret cave, where he has his retreat. Again they are arrested with a faithful knight and put on board a small vessel, to be conveyed to England; but the knight, his servant and the prince rise en route and overcome their captors, and they make their way to Flanders. Meantime, King Henry, who has become separated from them, and for months wanders and hides like them, is betrayed by a monk into Edward’s hands and conveyed to the Tower, every indignity being heaped upon him (1465). He never after emerged alive, save once—when Warwick, in revolt, drove Edward IV. out of the kingdom and paraded London with the poor captive, hailing him Henry VI. restored.

A complete history of this most varied and tragic period would include all the ups and downs of Edward IV.; the glory, decline and fall of Warwick, “the Last of the Barons,” and a volume of stormy, bloody incidents. This crisis is the dividing ridge between the areas of mediævalism and of modern times. Feudalism disappeared and the commercial system took its place. The fittest survived, the weaker system went down and buried poor Margaret’s fortunes in the debris. Her figure and Warwick’s, strangely enough, together stand relieved in the lurid lights that accompany the crash.

That closing scene was the most strange and tragic of all. “The King-Maker” has quarreled with the king whom he made Edward IV., and under the sting of that licentious prince’s plot to corrupt the virtue of Warwick’s favorite daughter, Anne Neville (afterward wife of Richard III.), the father has hastened to France and offered to Margaret the King-Maker’s sword to make the young Edward of Lancaster king of England. After long delays, again buffeted by conspiring waves, Warwick, Margaret, and Edward (now a soldierly youth of eighteen), land in England, but separately. Her ill-fortune follows her to the last, and their divided forces are cut off in detail by Henry’s army. The battle of Barnet, where “the Last of the Barons” falls, is lost because of a fog in which his troops destroy each other by mistake. Then in a few days Margaret is hemmed in with her little army against the river Severn, and the last act of the tragedy is enacted at Tewksbury. When all is lost, the woman in the heroic queen asserts itself in a swoon, and her son is captured fighting fiercely to cover the escape of the mother who had fought so fiercely and so many times to cover his. The young prince is brought bound into King Henry’s tent, and the contending cousins stand face to face—the representatives of the expiring Past and the living Future.

“What brings you to England?” sternly demands the king.

“I came to seek my father’s crown and mine own inheritance,” replies the undaunted representative of the older England.

For answer the king strikes the manacled youth in the face with his steel gauntlet. Yes, there can be no mistaking it. Chivalry is dead! The Duke of Clarence and the Duke of Gloucester draw and bravely cut down the prisoner, and the last hope of Lancaster’s royal line is dead upon the ground. Richard II. is avenged, and one more tragedy is added to the fearful chronicle of royal crimes.

One day in May, 1471, the pale, meek face of Henry VI.[496] looked down from a grated window in the tower upon a street pageant which his wife graced as a captive in the train of the victorious Edward IV. Then a few days later that same face, just as calm but paler, was exhibited in St. Paul’s. The Yorkists said he died of grief. The Tudor historians placed his death, with the invented hump, on the back of Richard III., and the genius of Shakspere riveted them there and a fearful load of other sins on top of them. So closed the usurping line of Lancaster at the hands of the usurpers of York.

Margaret was soon ransomed by the king of France, and returned to her father in Anjou. Miss Strickland says: “Margaret had lost her beauty with excessive weeping: a dry leprosy transformed this princess, who had been the fairest in the world, into a spectacle of horror.” She died in 1483, aged fifty-one years, into which had been compressed an age of tragedy and sorrow. Three hundred years later, another unhappy sovereign, Maria Louisa, Napoleon’s empress, possessed Margaret’s breviary, in which there was a sentence in Margaret’s hand that told the moral of her life:

SELECTED BY THE REV. J. H. VINCENT, D.D.

By JOHN CAIRD, D.D.[L]

To combine business with religion, to keep up a spirit of serious piety amid the stir and distraction of a busy and active life—this is one of the most difficult parts of a Christian’s trial in this world. It is comparatively easy to be religious in the church—to collect our thoughts, and compose our feelings, and enter, with an appearance of propriety and decorum, into the offices of religious worship, amid the quietude of the Sabbath, and within the still and sacred precincts of the house of prayer. But to be religious in the world—to be pious, and holy, and earnest-minded in the counting-room, the manufactory, the market-place, the field, the farm—to carry out our good and solemn thoughts and feelings into the throng and thoroughfare of daily life—this is the great difficulty of our Christian calling. No man not lost to all moral influence can help feeling his worldly passions calmed, and some measure of seriousness stealing over his mind, when engaged in the performance of the more awful and sacred rites of religion; but the atmosphere of the social circle, the exchange, the street, the city’s throng, amid coarse work and cankering cares and toils, is a very different atmosphere from that of a communion-table. Passing from the one to the other has often seemed as if the sudden transition from a tropical to a polar climate—from balmy warmth and sunshine to murky mist and freezing cold. And it appears sometimes as difficult to maintain the strength and steadfastness of religious principle and feeling, when we go forth from the church into the world, as it would be to preserve an exotic alive in the open air in winter, or to keep the lamp that burns steadily within doors from being blown out if you take it abroad unsheltered from the wind.

So great, so all but insuperable, has this difficulty ever appeared to men, that it is but few who set themselves honestly and resolutely to the effort to overcome it. The great majority, by various shifts or expedients, evade the hard task of being good and holy, at once in the church and in the world.

In ancient times, for instance, it was, as we all know, the not uncommon expedient among devout persons—men deeply impressed with the thought of an eternal world, and the necessity of preparing for it, but distracted by the effort to attend to the duties of religion amid the business and temptations of secular life—to fly the world altogether, and, abandoning society and all social claims, to betake themselves to some hermit solitude, some quiet and cloistered retreat, where, as they fondly deemed, “the world forgetting, by the world forgot,” their work would become worship, and life be uninterruptedly devoted to the cultivation of religion in the soul. In our own day the more common device, where religion and the world conflict, is not that of the superstitious recluse, but one even much less safe and venial. Keen for this world, yet not willing to lose all hold on the next—eager for the advantages of time, yet not prepared to abandon all religion and stand by the consequences, there is a very numerous class who attempt to compromise the matter—to treat religion and the world like two creditors whose claims can not both be liquidated—by compounding with each for a share—though in this case a most disproportionate share—of their time and thought. “Everything in its own place!” is the tacit reflection of such men. “Prayers, sermons, holy reading”—they will scarcely venture to add, “God”—“are for Sundays; but week-days are for the sober business, the real, practical affairs of life. Enough if we give the Sunday to our religious duties; we can not always be praying and reading the Bible.”

Now, you will observe that the idea of religion which is set forth in the text, as elsewhere in Scripture, is quite different from any of these notions. The text speaks as if the most diligent attention to our worldly business were not by any means incompatible with spirituality of mind and serious devotion to the service of God. It seems to imply that religion is not so much a duty, as a something that has to do with all duties—not a tax to be paid periodically and got rid of at other times, but a ceaseless, all-pervading, inexhaustible tribute to him, who is not only the object of religious worship, but the end of our very life and being. It suggests to us the idea that piety is not for Sundays only, but for all days; that spirituality of mind is not appropriate to one set of actions and an impertinence and intrusion with reference to others, but like the act of breathing, like the circulation of the blood, like the silent growth of the stature, a process that may be going on simultaneously with all our actions—when we are busiest as when we are idlest; in the church, in the world, in solitude, in society; in our grief and in our gladness; in our toil and in our rest; sleeping, waking; by day, by night—amid all the engagements and exigences of life. For you perceive that in one breath—as duties not only not incompatible, but necessarily and inseparably blended with each other—the text exhorts us to be at once “not slothful in business,” and “fervent in spirit, serving the[497] Lord.” I shall now attempt to prove and illustrate the idea thus suggested to us—the compatibility of religion with the business of common life.

We have, then, Scripture authority for asserting that it is not impossible to live a life of fervent piety amid the most engrossing pursuits and engagements of the world. We are to make good this conception of life—that the hardest-wrought man of trade, or commerce, or handicraft, who spends his days “‘mid dusky lane or wrangling marl,” may yet be the most holy and spiritually-minded. We need not quit the world and abandon its busy pursuits in order to live near to God—

It is true indeed that, if in no other way could we prepare for an eternal world than by retiring from the business and cares of this world, so momentous are the interests involved in religion, that no wise man should hesitate to submit to the sacrifice. Life here is but a span. Life hereafter is forever. A lifetime of solitude, hardship, penury, were all too slight a price to pay, if need be, for an eternity of bliss: and the results of our most incessant toil and application to the world’s business, could they secure for us the highest prizes of earthly ambition, would be purchased at a tremendous cost, if they stole away from us the only time in which we could prepare to meet our God—if they left us at last rich, gay, honored, possessed of every thing the world holds dear, but to face an eternity undone.

But the very impossibility of such a sacrifice proves that no such sacrifice is demanded. He who rules the world is no arbitrary tyrant prescribing impracticable labors. In the material world there are no conflicting laws; and no more, we may rest assured, are there established in the moral world, any two laws, one or the other of which must needs be disobeyed. Now one thing is certain, that there is in the moral world a law of labor. Secular work, in all cases a duty, is, in most cases, a necessity. God might have made us independent of work. He might have nourished us like “the fowls of the air and the lilies of the field,” which “toil not, neither do they spin.” He might have rained down our daily food, like the manna of old, from heaven, or caused nature to yield it in unsolicited profusion to all, and so set us free to a life of devotion. But, forasmuch as he has not done so—forasmuch as he has so constituted us that without work we can not eat, that if men ceased for a single day to labor, the machinery of life would come to a stand, and arrest be laid on science, civilization, and progress—on every thing that is conducive to the welfare of man in the present life—we may safely conclude that religion, which is also good for man, which is indeed, the supreme good of man, is not inconsistent with hard work.

And that this is so—that this blending of religion with the work of common life is not impossible, you will readily perceive, if you consider for a moment what, according to the right and proper notion of it, Religion is. What do we mean by “Religion?”

Religion may be viewed in two aspects. It is a Science, and it is an Art; in other words, a system of doctrines to be believed, and a system of duties to be done. View it in either light, and the point we are insisting on may, without difficulty, be made good. View it as a science—as truth to be understood and believed. If religious truth were, like many kinds of secular truth, hard, intricate, abstruse, demanding for its study, not only the highest order of intellect, but all the resources of education, books, learned leisure, then indeed to most men, the blending of religion with the necessary avocations of life would be an impossibility. In that case it would be sufficient excuse for irreligion to plead, “My lot in life is inevitably one of incessant care and toil, of busy, anxious thought, and wearing work. Inextricably involved, every day and hour as I am, in the world’s business, how is it possible for me to devote myself to this high and abstract science?” If religion were thus, like the higher mathematics or metaphysics, a science based on the most recondite and elaborate reasonings, capable of being mastered only by the acutest minds, after years of study and laborious investigation, then might it well be urged by many an unlettered man of toil, “I am no scholar—I have no head to comprehend these hard dogmas and doctrines.”

But the gospel is no such system of high and abstract truth. The salvation it offers is not the prize of a lofty intellect, but of a lowly heart. The mirror in which its grand truths are reflected is not a mind of calm and philosophic abstraction, but a heart of earnest purity. Its light shines best and fullest, not on a life undisturbed by business, but on a soul unstained by sin. The religion of Christ, while it affords scope for the loftiest intellect in the contemplation and development of its glorious truths, is yet, in the exquisite simplicity of its essential facts and principles, patent to the simplest mind. Rude, untutored, toil-worn you may be, but if you have wit enough to guide you in the commonest round of daily toil, you have wit enough to learn to be saved. The truth as it is in Jesus, while, in one view of it, so profound that the highest archangel’s intellect may be lost in the contemplation of its mysterious depths, is yet, in another, so simple that the lisping babe at a mother’s knee may learn its meaning.

Again: view religion as an Art, and in this light, too, its compatibility with a busy and active life in the world, it will not be difficult to perceive. For religion as an art differs from secular arts in this respect, that it may be practiced simultaneously with other arts—with all other work and occupation in which we may be engaged. A man can not be studying architecture and law at the same time. The medical practitioner can not be engaged with his patients, and at the same time planning houses or building bridges—practicing, in other words, both medicine and engineering at one and the same moment. The practice of one secular art excludes for the time the practice of other secular arts. But not so with the art of religion. This is the universal art, the common, all-embracing profession. It belongs to no one set of functionaries, to no special class of men. Statesman, soldier, lawyer, physician, poet, painter, tradesman, farmer—men of every craft and calling in life—may, while in the actual discharge of the duties of their varied avocations, be yet, at the same moment, discharging the duties of a higher and nobler vocation—practicing the art of a Christian. Secular arts, in most cases, demand of him who would attain to eminence in any one of them, an almost exclusive devotion of time and thought, and toil. The most versatile genius can seldom be master of more than one art; and for the great majority the only calling must be that by which they can earn their daily bread. Demand of the poor tradesman or peasant, whose every hour is absorbed in the struggle to earn a competency for himself and his family, that he shall be also a thorough proficient in the art of the physician, or lawyer, or sculptor, and you demand an impossibility. If religion were an art such as these, few indeed could learn it. The two admonitions, “Be diligent in business,” and “Be fervent in spirit, serving the Lord,” would be reciprocally destructive.

But religion is no such art, for it is the art of being, and of doing good; to be an adept in it, is to become just, truthful, sincere, self-denied, gentle, forbearing, pure in word and thought and deed. And the school for learning this art is[498] not the closet, but the world—not some hallowed spot where religion is taught, and proficients, when duly trained, are sent forth into the world—but the world itself—the coarse, profane, common world, with its cares and temptations, its rivalries and competitions, its hourly, ever-recurring trials of temper and character. This is, therefore, an art which all can practice, and for which every profession and calling, the busiest and most absorbing, afford scope and discipline. When a child is learning to write, it matters not of what words the copy set to him is composed, the thing desired being that whatever he writes, he learn to write well. When a man is learning to be Christian, it matters not what his particular work in life may be; the work he does is but the copy-line set to him; the main thing to be considered is that he learn to live well. The form is nothing, the execution is everything. It is true, indeed, that prayer, holy reading, meditation, the solemnities and services of the church are necessary to religion, and that these can be practiced only apart from the work of secular life. But it is to be remembered that all such holy exercises do not terminate in themselves. They are but steps in the ladder of heaven, good only as they help us to climb. They are the irrigation and enriching of the spiritual soil—worse than useless if the crop be not more abundant. They are, in short, but means to an end—good, only in so far as they help us to be good and do good—to glorify God and do good to man; and that end can perhaps be best attained by him whose life is a busy one, whose avocations bear him daily into contact with his fellows, into the intercourse of society, into the heart of the world.