The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Title: Autobiography of Samuel S. Hildebrand, the Renowned Missouri "Bushwacker" and Unconquerable Rob Roy of America

Author: Samuel S. Hildebrand

Editor: James W. Evans

A. Wendell Keith

Release date: November 5, 2015 [eBook #50389]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive)

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

1

This is to certify that I, the undersigned, am personally acquainted with Samuel S. Hildebrand (better known as “Sam Hildebrand, the Missouri Bushwhacker,” etc.,) and have known him from boyhood; that during the war, and on several occasions since its termination, he promised to give me a full and complete history of his whole war record; that on the night of January 28th, 1870, he came to my house at Big River Mills, in St. Francois county, Missouri, in company with Charles Burks, and gave his consent that I and Charles Burks, in conjunction, might have his confession whenever we were prepared to meet him at a certain place for that purpose; that in the latter part of March, 1870, in the presence of Sam Hildebrand alone, I did write out his confession as he gave it to me, then and there, until the same was completed; and that afterwards James W. Evans and myself, from the material I thus obtained, compiled and completed the said confession, which is now presented to the public as his Autobiography.

STATE OF MISSOURI, }

County of Ste. Genevieve. }

On this, 14th day of June, 1870, before me, Henry Herter, a Notary Public within and for said county, personally appeared W. H. Couzens, J. N. Burks and G. W. Murphy of the above county and State, and on being duly sworn they stated that they were well acquainted with Charles Burks of the aforesaid county, and A. Wendell Keith, M. D., of St. Francois county, Missouri, and to their certain knowledge the facts set forth in the foregoing 2 certificate are true and correct, and that Samuel S. Hildebrand also acknowledged to them afterwards that he had made to them his complete confession.

Subscribed and sworn to before me, this 14th day of June, 1870.

The Statement made by A. Wendell Keith, M. D., is entitled to credit from the fact of his well-known veracity and standing in society.

I hereby certify that the persons whose official signatures appear above have been commissioned for the offices indicated; and my personal acquaintance with Dr. Keith, Honorables Evans, Sebastian, Cayce, Bogy and Sheriff Murphy is such that I say without hesitation their statements are entitled to full faith and credit.

3

4

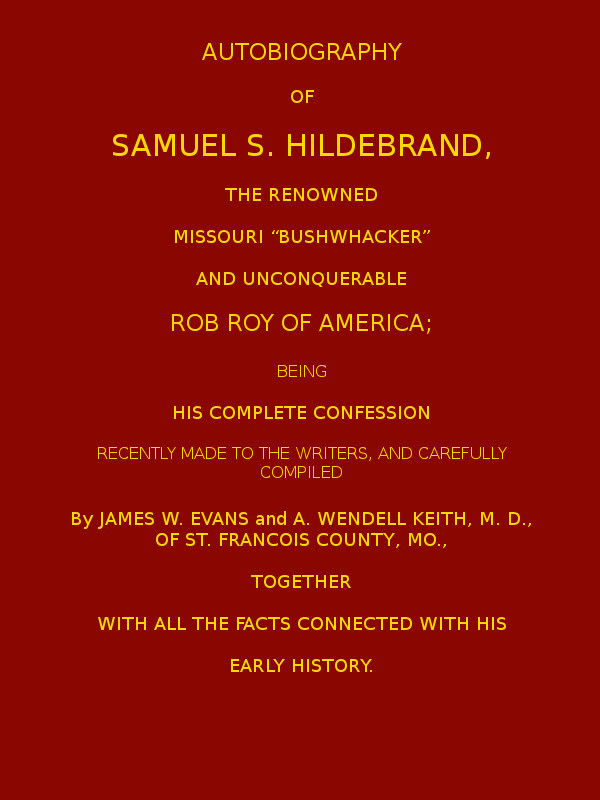

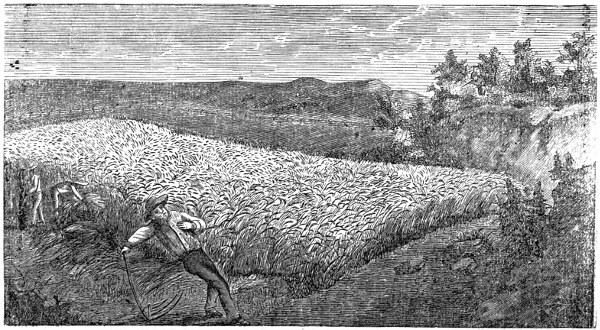

HILDEBRAND DRIVEN FROM HOME.

5

6

Entered according to act of Congress in the year 1870, by James W. Evans and A. Wendell Keith, M. D., in the Clerk‘s Office of the District Court of the United States for the Eastern District of Missouri. 7

CHAPTER I. |

|

|---|---|

| Introduction.—Yankee fiction.—Reasons for making a full confession. | 25 |

CHAPTER II. |

|

| Early history of the Hildebrand family.—Their settlement in St. Francois county, Mo.—Sam Hildebrand born.—Troublesome neighbors.—Union sentiments. | 29 |

CHAPTER III. |

|

| Determination to take no part in the war.—Mr. Ringer killed by Rebels.—The cunning device of Allen Roan.—Vigilance Committee organized.—The baseness of Mobocracy.—Attacked by the mob.—Escape to Flat Woods. | 35 |

CHAPTER IV. |

|

| McIlvaine‘s Vigilance mob.—Treachery of Castleman.—Frank Hildebrand hung by the mob.—Organization of the mob into a Militia company. | 42 |

CHAPTER V. |

|

| His house at Flat Woods attacked by eighty soldiers.—Miraculous escape.—Capt. Bolin.—Flight to Green county, Arkansas. | 48 |

CHAPTER VI. |

|

| Interview with Gen. Jeff Thompson.—Receives a Major‘s Commission.—Interview with Capt. Bolin.—Joins the Bushwhacking Department. | 54 |

CHAPTER VII. |

|

| First trip to Missouri.—Killed George Cornecious for reporting him.—Killed Firman McIlvaine, captain of the mob.—Attempt to kill McGahan and House.—Return to Arkansas. | 58 |

CHAPTER VIII. |

|

| Vigilance mob drives his mother from home.—Three companies of troops sent to Big river.—Capt. Flanche murders Washington Hildebrand and Landusky.—Capt. Esroger murders John Roan.—Capt. Adolph burns the Hildebrand homestead and murders Henry Hildebrand. | 66 |

CHAPTER IX. |

|

| Trip with Burlap and Cato.—Killed a spy near Bloomfield.—Visits his mother on Dry Creek.—Interview with his uncle.—Sees the burning of the homestead at a distance. | 75 |

CHAPTER X. |

|

| Trip with two men.—Killed Stokes for informing on him.—Secreted in a cave on Big river.—Vows of vengeance.—Watched for McGahan.—Tom Haile pleads for Franklin Murphy.—Tongue-lashed and whipped out by a woman. | 84 8 |

CHAPTER XI. |

|

| Trip to Missouri with three men.—Fight near Fredericktown.—Killed four soldiers.—Went to their camp and stole four horses.—Flight toward the South.—Robbed “Old Crusty”. | 91 |

CHAPTER XII. |

|

| Trip with three men.—Captured a spy and shot him.—Shot Mr. Scaggs.—Charged a Federal camp at night and killed nine men.—Came near shooting James Craig.—Robbed Bean‘s store and returned to Arkansas. | 96 |

CHAPTER XIII. |

|

| The Militia mob robs the Hildebrand estate.—Trip to Missouri with ten men.—Attacks a government train with an escort of twenty men.—Killed two and put the others to flight. | 102 |

CHAPTER XIV. |

|

| Federal cruelty.—A defense of Bushwhacking.—Trip with Capt. Bolin and nine men.—Fight at West Prairie.—Started with two men to St. Francois county.—Killed a Federal soldier.—Killed Addison Cunningham.—Capt. Walker kills Capt. Barnes, and Hildebrand kills Capt. Walker. | 106 |

CHAPTER XV. |

|

| Started alone to Missouri.—Rode off a bluff and killed his horse.—Fell in with twenty-five Rebels under Lieut. Childs.—Went with them.—Attacked 150 Federals at Bollinger‘s Mill.— Henry Resinger killed.—William Cato.—Went back to Fredericktown.—Killed one man.—Robbed Abright‘s store. | 114 |

CHAPTER XVI. |

|

| Started to Bloomfield with three men.—Fight at St. Francis river.—Goes from there alone.—Meets his wife and family, who had been ordered off from Bloomfield.—Capture and release of Mrs. Hildebrand.—Fight in Stoddard county.—Arrival in Arkansas. | 121 |

CHAPTER XVII. |

|

| Put in a crop.—Took another trip to Missouri with six men.—Surrounded in a tobacco barn.—Killed two men in making his escape.—Killed Wammack for informing on him.—Captured some Federals and released them on certain conditions.—Went to Big River Mills.—Robbed Highley‘s and Bean‘s stores. | 128 |

CHAPTER XVIII. |

|

| Selected seven men and went to Negro Wool Swamp.—Attacked fifteen Federals—A running fight.—Killed three men.—Killed Mr. Crane.—Betrayed by a Dutchman, and surrounded in a house by Federals.—Escaped, killed eight Federals, recaptured the horses, and hung the Dutchman. | 136 |

CHAPTER XIX. |

|

| Went with eight men.—Attacked a Federal camp near Bollinger‘s Mill.—Got defeated.—Men returned to Arkansas.—Went alone to St. Francois county.—Watched for R. M. Cole.—Killed Capt. Hicks. | 147 |

CHAPTER XX. |

|

| Trip to Hamburg with fifteen men.—Hung a Dutchman and shot another.—Attacked some Federals in Hamburg but got gloriously 9 whipped.—Retreated to Coon Island.—Killed Oller at Flat Woods.—Robbed Bean‘s store at Irondale. | 153 |

CHAPTER XXI. |

|

| Started with six men on a trip to Springfield, Missouri.—Deceived by a Federal spy in the Irish Wilderness—Captured through mistake by Rebels.—Routed on Panther creek.—Returned home on foot. | 159 |

CHAPTER XXII. |

|

| Started with four men.—Surrounded in a thicket near Fredericktown.—Escaped with the loss of three horses.—Stole horses from the Federals at night.—Killed two soldiers.—Suffered from hunger.—Killed Fowler.—Took a horse from G. W. Murphy.—Went to Mingo Swamp.—Killed Coots for betraying him.—Killed a Federal and lost two men. | 168 |

CHAPTER XXIII. |

|

| Went to Mingo Swamp with ten men.—Went to Castor creek.—Attacked two companies of Federals under Capt. Cawhorn and Capt. Rhoder.—Bushwhacked them seven nights.—Went with Capt. Reed‘s men.—Attacked Capt. Leeper‘s company.—Killed fourteen, captured forty horses, forty-four guns, sixty pistols, and everything else they had. | 182 |

CHAPTER XXIV. |

|

| Took a trip with fifteen men.—Captured a squad of Federals.—Reception of “Uncle Bill.”—Hung all the prisoners.—Captured five more and hung one. |

187 |

CHAPTER XXV. |

|

| Put in a crop.—Started to Missouri with nine men.—Killed a soldier near Dallas.—Went to St. Francois county and watched for Walls and Baker.—Watched near Big River Mills for McGahan.—Narrow escape of William Sharp.—Robbed Burges, Hughes and Kelley of their horses.—Robbed Abright‘s store.—Captured some Federals on White Water. | 195 |

CHAPTER XXVI. |

|

| Started to St. Francois county, Missouri, with eight men.—Hung Vogus and Zimmer.—Hung George Hart.—Robbed Lepp‘s store.—Concealed in Pike Run hills.—Started back.—Hung Mr. Mett‘s negro, “Old Isaac.”—Hung another negro.—Took two deserters back and hung them. | 205 |

CHAPTER XXVII. |

|

| Started with nine men to St. Francois county.—Stopped in Pike Run hills.—Robbed the store of Christopher Lepp.—Hung Mr. Kinder‘s negro.—Attacked by Federals.—Killed two men and lost one.—Shot two soldiers on a furlough.—Enters a mysterious camp. | 212 |

CHAPTER XXVIII. |

|

| Capt. John and a company of Federals destroy the Bushwhackers‘ Headquarters in Green county, Arkansas.—He is bushwhacked, routed and killed.—Raid into Washington county with fourteen men.—Attacked by twenty Federals.—Killed the man who piloted Capt. John. | 219 10 |

CHAPTER XXIX. |

|

| Took a raid into Missouri with four men.—Killed a Federal.—Killed two of Capt. Milks‘ men.—Started to De Soto.—Routed by the Federals.—Adventure with a German.—Killed three Federals on Black river. | 228 |

CHAPTER XXX. |

|

| Commanded the advance guard on Price‘s raid.—The Federals burn Doniphan.—Routed the Federals completely.—Captured several at Patterson.—Killed Abright at Farmington.—Left Price‘s army.—Killed four Federals.—Major Montgomery storms Big River Mills.—Narrow escape from capture. | 237 |

CHAPTER XXXI. |

|

| Selected three men and went to Missouri to avenge the death of Rev. William Polk.—Got ammunition in Fredericktown.—Killed the German who informed on Polk.—Return to Arkansas. | 244 |

CHAPTER XXXII. |

|

| Started with eight men on a trip to Arkansas river.—Hung a “Scallawag” on White river.—Went into Conway county.—Treachery of a negro on Point Remove.—“Foot-burning” atrocities.—Started back and hung a renegade. | 250 |

CHAPTER XXXIII. |

|

| Gloomy prospects for the South.—Takes a trip to Missouri with four men.—Saved from capture by a woman.—Visits his mother on Big river.—Robs the store of J. V. Tyler at Big River Mills—Escapes to Arkansas. | 257 |

CHAPTER XXXIV. |

|

| Started to Missouri with three men.—Surrounded at night near Fredericktown.—Narrow escape by a cunning device.—Retired to Simms‘ Mountain.—Swapped horses with Robert Hill, and captured some more.—Killed Free Jim and kidnapped a negro boy. | 264 |

CHAPTER XXXV. |

|

| Trip to Missouri with four men.—Attempt to rob Taylor‘s store.—Fight with Lieut. Brown and his soldiers.—Killed Miller and Johnson at Flat Woods.—Return home from his last raid.—The war is pronounced to be at an end.—Reflections on the termination of the war.—Mrs. Hildebrand‘s advice.—The parole at Jacksonport. | 275 |

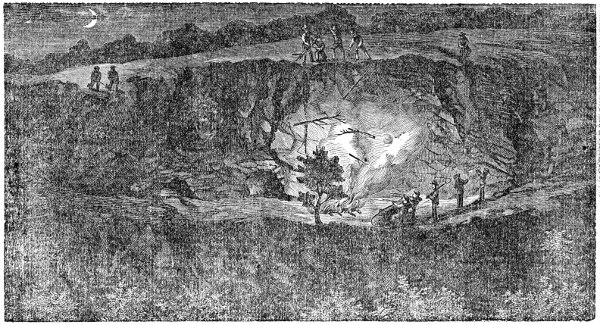

CHAPTER XXXVI. |

|

| Imprisoned in Jacksonport jail.—Mrs. Hildebrand returns to Missouri.—Escape from prison.—Final settlement in Ste. Genevieve county.—St. Louis detectives make their first trip.—The Governor‘s reward.—Wounded by Peterson.—Removed to his uncle‘s.—Fight at John Williams‘.—Kills James McLaine.—Hides in a cave. | 286 |

CHAPTER XXXVII. |

|

| Military operations for his capture.—Col. Bowen captures the Cave.—Progress of the campaign.—Advent of Governor McClurg.—The Militia called out.—Don Quixote affair at the Brick Church.—The campaign ended.—Mrs. Hildebrand escapes to Illinois.—“Sam” leaves Missouri.—His final proclamation. | 300 |

11

The public having been grossly imposed upon by several spurious productions purporting to be the “Life of Sam Hildebrand,” we have no apology to offer for presenting the reader with his authentic narrative.

His confession was faithfully written down from his own lips, as the foregoing certificates abundantly prove.

From this copious manuscript we have prepared his autobiography for the press, with a scrupulous care to give it literally, so far as the arbitrary rules of language would permit. Sam Hildebrand and the authors of this work were raised up from boyhood together, in the same neighborhood, and we are confident that no material facts have been suppressed by Hildebrand in his confession.

The whole narrative is given to the reader without any effort upon our part either to justify or condemn his acts. Our design was to give the genuine autobiography of Sam Hildebrand; this we have done.

The book, as a record of bloody deeds, dare-devil exploits and thrilling adventures, will have no rival in the catalogue of wonders; for it at once unfolds, 12 with minute accuracy, the exploits of Hildebrand, of which one-half had never yet been told. Without this record the world would forever remain in ignorance of the night history of his astounding audacity.

We here tender our thanks to those of our friends who have kindly assisted us in this work, prominent among whom is Miss Hilda F. Sharp, of Jefferson City, Mo., who furnished us with those beautiful pencil sketches from which our engravings were made.

Big River Mills, Mo., June, 1870. 13

Before proceeding with the Autobiography of Samuel S. Hildebrand, we would call the attention of the reader to the fact, that since notoriety has been thrust upon the subject of these memoirs, public attention has been pointed to the fact, that in German history, the Hildebrands occupy a very prominent position.

The authors of this work, by a diligent research into ancient German literature, have been able to trace the origin and history of the Hildebrand family, with tolerable accuracy, to the beginning of the ninth century. The name Hildebrand or Hildebrandt is as old as the German language. Hilde, in ancient German, signified a “Hero,” and brand, a “blaze or flame.” It is thought by some writers that the name doubtless signified a “flaming hero.” 14

Whether this is the case or not, it matters but little, as the fact remains clearly defined that the first man of that name known to history was a hero in every sense of the word. The “Heldenbuch” or Book of Heroes, in its original form, dates back to the eighth century. It is a beautiful collection of poems relative to Dietrich or Theodoric. It was written down from memory by the Hessian monks on the outer pages of an old Latin manuscript, and was first published by Eccard in prose, but it was afterwards discovered that the songs were originally in rhyme.

The poem treats of the expulsion of Dietrich of Vaum out of his dominions by Ermenrick, his escape to Attila and his return after an adventurous exile of thirty years. Hildebrand (the old Dietrich) encounters his son, whom he left at home in his flight, in a terrible encounter without knowing who he was. We will present the reader with Das Hildebrands lied (The song of Hildebrand), not on account of any literary merit it may possess, but because of its great antiquity and its popularity among the German people at one time, and by whom it was dramatized. 15

18 We congratulate our readers on having survived the reading of the above poem, written a thousand years ago, about old Dietrich, the “father Abraham” of all the Hildebrands; but he must not forget that he is subject to a relapse, for here are two verses not taken from the “Book of Heroes,” but from an old popular song in use to this day among the peasantry in South Germany:

The reader will perceive that the peasantry are disposed to “poke fun” at the great ancestor of the Hildebrand family; this, however, we will attribute to envy, and make no effort to prove that “Hildebrand and his son Hudebrand” were Good Templars, lest we prove too much, and cause the reader to doubt their Dutch origin altogether. 19

Following the geneology down, we meet with several of the Hildebrands celebrated in the ecclesiastical, literary and scientific world. Of the parentage of Gregory VII. but little is known more than that he was a Hildebrand, born near Rome, but of German parents. On becoming a Roman Pontiff in 1077, he assumed the name of Gregory. He occupied the chair of St. Peter for eight years, during which time he assumed an authority over the crowned heads of Europe, never before attempted. He was a bold man, but was driven from his chair in 1085.

George Frederick Hildebrand was a famous physician, who was born June 5, 1764, at Hanover. He was one of the most learned men of his age; was appointed professor of Anatomy at Brunswick, but he soon took the chair of Chemistry, at Erlangen, in Bavaria. He died March 23, 1816, leaving some of the most elaborate and valuable works ever written.

Ferdinand Theodore Hildebrand was born Juno 2, 1804, and under the tuition of Professor Schadaw, at Berlin, he became very renowned as a painter. He followed his tutor to Dusseldorf in 1826, and was one of the most celebrated artists of the Academy of Painting at that place. In 1830 Hildebrand visited Italy to view the productions of some of the old masters, and afterwards traveled through the Netherlands. Some of his best pictures were drawn to represent scenes in the works of Shakspeare, of which “King Lear mourning over the death of Cordelia,” was perhaps the most important. But among the critics, “The sons of Edward” was considered his greatest production. 20

It is not our purpose to name all the illustrious Hildebrands who have figured in German history or literature; for it must be borne in mind that from the ninth century down to the sixteenth, the name Hildebrand was almost invariably applied as a given name; it was not until that century that it appears as a sur-name. It is a fact, however, well known to historians, that the same given name is frequently retained in a family, and handed down from one generation to another perhaps for one thousand years.

In the southern part of Germany the name Hildebrand was borne by a certain class of vassals, but in the Northern States of that country, there were families of noble birth by the same name. The record of those nobles runs back with a great deal of certainty to a very remote period of German history—beyond which, the dim out-lines of tradition alone can be our guide. This tradition, whether entitled to credit or not, traces the geneology of the Hildebrands in the line of nobles up to Sir Hildebrand, the exiled hero mentioned in the Book of Heroes.

According to the record of the Hildebrand family, as given by Henry Hildebrand of Jefferson county, Missouri, to the authors of this work; the seventh generation back reaches to Peter Hildebrand of Hanover. He was born in 1655, and was the youngest son of a nobleman. His father having died while Peter was yet a boy, he was educated at a military school, and after arriving to manhood he served several years in the army. Returning at length, he was vexed at the cold reception he received from his elder brother, who 21 now inherited the estate with all the titles of nobility belonging to the family. He resolved to emigrate to the wild solitudes of America, where individual worth and courage was the stepping stone to honor and distinction.

His family consisted of a wife and three children; his oldest son, Jacob, was born in 1680; when he was ten years of age the whole family emigrated to New Amsterdam, remained three years and then settled in the northern part of Pennsylvania, where he died a few years afterwards.

Jacob Hildebrand‘s second son, Jacob, was born in 1705. He was fond of adventure and joined in several exploring expeditions in one of which he was captured by a band of Miami Indians, and only escaped by plunging into the Ohio river and concealing himself under a drift of floating logs. His feelings of hostility against the Indians prompted him to join the expedition against them under Lieutenant Ward, who erected a fort at what is now called Pittsburg, in 1754, here he was killed in a vain attempt to hold the garrison against the French and Indians under Contrecoeur.

His third son, John Hildebrand, was born in 1733, and at the death of his father was twenty-one years of age. Like most of the frontiermen of this early period, he seemed to have an uncontrolable love of adventure. His most ardent desire was to explore the great valley of the Mississippi. At the period of which we are now speaking (1754), he joined James M. Bride and others and passed down the Ohio river in a canoe; to his regret, however, the company only reached the mouth of 22 the Kentucky river, cut their initials in the barks of trees, and then returned. In 1770 he removed to Missouri. His family consisted of his wife and two boys—Peter was born in 1758, and Jonathan in 1762. He built a flat-boat on the banks of the Ohio, and taking a bountiful supply of provisions, he embarked with his family. To avoid the Indians he kept as far from each shore as possible, and never landed but once to pass around the shoals. On reaching the Mississippi he spent more than a week in ascending that river to gain a proper point for crossing. He landed on the western side at Ste. Genevieve.

Viewing the country there as being rather thickly settled, he moved back into the wilderness about forty miles and settled on Big River at the mouth of Saline creek. He was the first settler in that country which was afterwards organized as Jefferson county. He opened a fine farm on Saline creek, built houses, and considered himself permanently located in that wild country. The Indians were unfriendly, and their hostility toward white settlers seemed to increase until 1780, when Peter Chouteau, by order of the Lieutenant Governor of Louisiana, went to see Hildebrand and warned him to leave on account of Indian depredations. He then removed to Ste. Genevieve.

In 1783, Peter Hildebrand left Ste. Genevieve and settled on Big River in the same neighborhood where his father had resided. He had a wife and four children, whose names were, Isaac, Abraham, David, and Betsy. He was a good marksman and very fond of hunting. After he had resided there about one year, 23 he was shot and killed by the Indians on the bank of Big River one morning while on his return from hunting wild game; after which the family removed nearer to a settlement.

In 1802, David Hildebrand settled on Big River, and about the same time Jonathan Hildebrand settled himself permanently on the same river. He lived until the commencement of the late war, and then died at the age of one hundred years. He had three sons, whose names are, George, Henry, and Samuel.

In 1832, George Hildebrand and his family moved higher up on Big River and settled in St. Francois county—his house was the Hildebrand homestead referred to in these pages—and he was the father of Samuel S. Hildebrand, whose Autobiography we now submit to our readers. 24

25

AUTOBIOGRAPHY

OF

SAMUEL S. HILDEBRAND.

Introduction.—Yankee Fiction.—Reasons for making a full confession.

Since the close of the late rebellion, knowing that I had taken a very active part during its progress several of my friends have solicited me to have my history written out in full. This anxiety to obtain the history of an individual so humble as myself, may be attributed to the fact, that never perhaps since the world began, have such efforts been put forth by a government for the suppression of one man alone, as have been used for my capture, both during the war and since its termination. The extensive military operations carried on by the Federal government in South-east Missouri, were in a great measure designed for my special destruction. 26

Since the close of the rebellion, while others are permitted to remain at home in peace, the war, without any abatement whatever, has continued against me with a vindictiveness and a lavish expenditure of money that has no parallel on this continent; but through it all, single-handed, have I come out unscathed and unconquered.

My enemies have thrust notoriety upon me, and have excited the public mind at a distance with a desire to know who I am and what I have done. Taking advantage of this popular inquiry, some enterprising individual in an eastern state has issued two or three novels purporting to be my history, but they are not even founded on fact, and miss the mark about as far as if they were designed for the Life of Queen Victoria. I seriously object to the use of my name in any such a manner. Any writer, of course, who is afflicted with an irresistible desire to write fiction, has a perfect right to do so, but he should select a fictitious name for the hero of his novels, that his works may stand or fall, according to their own intrinsic merit, rather than the name of an individual whose notoriety alone would insure the popularity of his books. But an attempt to palm a novel on the inquiring public as a history of my life, containing as it does a catalogue of criminal acts unknown to me in all my career, is not only a slander upon myself, but a glaring fraud upon the public.

Much of our misfortune as a nation may be attributed to the pernicious influence of the intolerant, intermeddling, irrepressible writers of falsehood. In a community 27 where the spirit of fiction pervades every department of literature and all the social relations of life, writers become so habituated to false coloring and deception, that plain unadorned truth has seldom been known to eminate from their perverted brains; it would be just as impossible for them to write down a naked fact as it would for the Prince of Darkness to write a volume of psalms.

The friend who has finally succeeded in tracing me to my quiet retreat in the wild solitudes of the down trodden South, is requesting me to make public the whole history of my life, without any attempt at palliation, concealment or apology. This I shall now proceed to do, in utter disregard to a perverted public opinion, and without the least desire or expectation of receiving justice from the minds of those who never knew justice, or sympathy from those who are destitute of that ingredient.

The necessity that was forced upon me to act the part I did during the reign of terror in Missouri, is all that I regret. It has deprived me of a happy home and the joys of domestic peace and quietude; it has driven me from the associations of childhood, and all the scenes of early life that so sweetly cling to the memory of man; it has caused my kind and indulgent mother to go down into her grave sorrowing; it has robbed me of three affectionate brothers who were brutally murdered and left weltering in their own innocent blood; it has reduced me and my family to absolute want and suffering, and has left us without a home, and I might almost say, without a country. 28

A necessity as implacable as the decrees of Fate, was forced upon me by the Union party to espouse the opposite side; and all the horrors of a merciless war were waged unceasingly against me for many months before I attempted to raise my hand in self defense. But fight I must, and fight I did! War was the object, and war it was. I never engage in but one business at a time—my business during the war was killing enemies. It is a very difficult matter to carry on a war for four years without some one getting hurt. If I did kill over a hundred men during the war, it was only because I was in earnest and supposed that everybody else was. My name is cast out as evil because I adopted the military tactics not in use among large armies. They were encumbered with artillery and fought where they had ample room to use it, I had no artillery and generally fought in the woods; my plan was the most successful, for in the regular army the rebels did not kill more than one man each during the war. 29

Early History of the Hildebrand family.—Settled in St. Francois county, Missouri.—Sam Hildebrand born.—Troublesome Neighbors.—Union Sentiments.

In regard to the early history of the Hildebrand family, I can only state what tradition has handed down from one generation to another. As I have no education, and can neither read in English nor Dutch, I am not able to give any of the outlines of history bearing upon the origin or acts of the Hildebrands in remote ages. This task I leave for others, with this remark, that tradition connects our family with the Hildebrands who figured in the German history up to the very origin of the Dutch language. The branch of the family to which I belong were driven from Bavaria into Netherlands two hundred years ago, where they remained about forty years, and then emigrated to Pennsylvania at the first settlement of that portion of America.

They were a hardy race of people and always shunned a city life, or being cooped up in thickly settled districts; they kept on the outskirts of aggressive civilization as it pressed the redman still back into the wild solitudes of the West, thus occupying the middle ground or twilight of refinement. Hence they continually breathed the pure, fresh air of our country‘s morning, trod through the dewy vales of pioneer life, 30 and drank at Freedom‘s shady fountains among the unclaimed hills.

They were literally a race of backwoodsmen inured to hardship, and delighted in nothing so much as wild adventure and personal danger. They explored the hills rather than the dull pages of history, pursued the wild deer instead of tame literature, and enjoyed their own thoughts rather than the dreamy notions eminating from the feverish brain of philosophy.

In 1832 my father and mother, George and Rebecca Hildebrand, settled in St. Francois county, Missouri, on a stream called Big River, one of the tributaries of the Meramec which empties into the Mississippi about twenty miles below St. Louis.

The bottom lands on Big River are remarkably fertile, and my father was so fortunate as to secure one of the best bodies of land in that county. Timber grew in abundance, both on the hills and in the valleys, consequently it took a great deal of hard labor to open a farm; but after a few years of close attention, father, by the assistance of his boys who were growing up, succeeded in opening a very large one. He built a large stone dwelling house two stories high, and finished it off in beautiful style, besides other buildings—barns, cribs and stables necessary on every well regulated farm.

Father and mother raised a family of ten children, consisting of seven boys and three girls. I was the fifth one in the family, and was born at the old homestead on Big River, St. Francois county, Missouri, on the 6th day of January, 1836. 31

The facilities for acquiring an education in that neighborhood were very slim indeed, besides I never felt inclined to go to school even when I had a chance; I was too fond of hunting and fishing, or playing around the majestic bluffs that wall in one side or the other of Big River, the whole length of that crooked and very romantic stream. One day‘s schooling was all that I ever got in my life; that day was sufficient for me, it gave me a distaste to the very sight of a school house. I only learned the names of two letters, one shaped like the gable end of a house roof, and the other shaped like an ox yoke standing on end. At recess in the afternoon the boys got to picking at me while the teacher was gone to dinner, and I had them every one to whip. When the old tyrant came back from dinner and commenced talking saucy, I gave him a good cursing and broke for home. My father very generously gave me my choice, either to go to school or to work on the farm. I gladly accepted the latter, redoubled my energy and always afterwards took particular pains to please my father in all things, because he was so kind as not to compel me to attend school. A threat to send me to school was all the whipping that I ever required to insure obedience; I was more afraid of that than I was of old “Raw-head-and-bloody-bones,” or even the old scratch himself.

In 1850, my father died, but I still remained at the homestead, working for the support of my mother and the rest of the family, until I had reached the age of nineteen years, then, on the 30th day of October, 1854, I married Miss Margaret Hampton, the daughter 32 of a highly esteemed citizen of St. Francois county. I built a neat log house, opened a farm for myself, within half a mile of the old homestead, and we went to housekeeping for ourselves.

From the time that my father first settled on Big River, we had an abundance of stock, and especially hogs. The range was always good, and as the uplands and hills constituted an endless forest of oaks, the inexhaustible supply of acorns afforded all the food that our hogs required; they roamed in the woods, and of course, many of them became as wild as deer; the wild ones remained among the hills and increased until they became very numerous. Whenever they were fat enough for pork, we were in the habit of going into the woods with our guns and our dogs and killing as many of them as we could.

A few years after my father had settled there, a colony of Pennsylvania Dutch had established themselves in our neighborhood; they were very numerous and constituted about two-thirds of the population of our township. They soon set up “wild hog claims,” declaring that some of their hogs had also run wild; this led to disputes and quarrels, and to some “fist and skull fighting,” in which my brothers and myself soon won the reputation of “bullies.” Finding that they had no show at this game, they next resorted to the law, and we had many little law suits before our justice of the peace. The Dutch out swore us, and we soon found the Hildebrand family branded by them with the very unjust and unpleasant epithet of “hog thieves;” but we went in on the muscle and still held the woods. 33

As our part of the country became more thickly settled and new neighbors came in, they in turn were prejudiced against us; and the rising generation seemed to cling to the same idea, that the Hildebrands seemed to love pork a little too well and needed watching. Unfortunately for me, my old neighbors were union men; all my sympathies too, were decidedly for the union. I heard with alarm the mutterings of war in the distance, like the deep tones of thunder beyond the frowning hills. I had never made politics my study; I had no education whatever, and had to rely exclusively on what others told me. Of course I was easily imposed upon by political tricksters, yet from my heart I deplored the necessity of a resort to arms, if such a necessity did exist, and whether it did or not was more than I could divine.

While my union neighbors and enemies were making the necessary preparations for leaving their families in comfortable circumstances before taking up arms in defense of their country, there were a few shrewd southern men around to magnify and distort the grievances of the southern people. In many cases the men whom they obtained had nothing in the world at stake, no useful object in view, no visible means of acquiring an honest livelihood, and were even without a horse to ride. This, however, only afforded them a pretext for practicing what they called “pressing horses,” which was done on a large scale. Neither political principles, patriotic motives, nor love of country prompted this abominable system of horse stealing. It was not confined to either party, and it was a remarkable 34 co-incident how invariably the political sentiments of a horse-pressing renegade would differ from the neighbor who happened to have the fastest horses. 35

Determination to take no part in the War.—Mr. Ringer killed by Rebels.—The cunning device of Allen Roan.—Vigilance Committee organized.—The baseness of Mobocracy.—Attacked by the Mob.—Escape to Flat Woods.

In the spring of 1861, the war of the Great Rebellion was inaugurated, and during the following summer was carried on in great fury in many places, but I shall only speak of those occurrences which had a particular bearing upon myself.

I called on some good citizens who were not republicans, and whom I knew to be well posted in the current events of the day, to ask them what course it was best for me to pursue during the unnatural struggle. They advised me to stay at home and attend to my own business. This I determined to do, so I paid no further attention to what was going on, put in my crop of corn at the usual season and cultivated it during the summer.

On the 9th day of August the popular excitement in St. Francois county was greatly increased by the killing of Mr. Ringer, a union man, who was shot at his own house for no other cause than his political principles. He was killed, as I afterwards learned, by Allen Roan and Tom Cooper. It should be borne in mind that Roan was a relative of mine with whom I was on 36 friendly terms. I was not implicated in the death of Ringer in any manner, shape, or form, but suspicion rested upon me; the “Hildebrand gang” were branded with the murder.

I could not check Roan in the rash course he was pursuing; but in all sincerity, I determined to follow the advice given me by a certain union friend, who told me to take no part in the cause that would in the end bring disaster upon myself. It was good advice; why then did I not follow it? In the presence of that Being who shall judge the quick and the dead, I shall truthfully and in a few words explain the whole matter. I had no sooner made up my mind fully what course to pursue, than I was caught in a cunningly devised trap that settled my destiny forever.

One evening Allen Roan came to my field where I was plowing and proposed swapping horses with me; the horse which he said he had bought was a better one than my own, so I consented to make the exchange; finding afterwards that the horse would not work in harness, I swapped him off the next day to Mr. Rogers.

Prior to this time my neighbors had organized themselves into what they called a Vigilance Committee, and were moving in squads night and day to put down horse stealing. Only a few of the committee were dangerous men, but Firman McIlvaine, who was put at the head of the gang was influenced by the worst element in the community; it became a political machine for oppression and bloodshed under the guidance of James Craig, John House, Joe McGahan, John Dunwoody, 37 William Patton, and others, who were swearing death to every man implicated in any way with the southern recruits who were pressing horses.

The horse I had traded for from Allen Roan and which Rogers obtained from me, proved to be the property of Dunwoody. I was apprised of the fact by a friend at night, and told also that they had threatened me and my brother Frank with death if they could find us, and notwithstanding our entire innocence in the matter, we were compelled to hide out. We knew that when the law is wrested from the civil authorities by such men as they were, that anything like a trial would not be permitted. We secreted ourselves in the woods, hoping that matters would take a different turn in a short time; each night I was posted in regard to their threats. I would willingly have surrendered myself to the civil authorities with a guarantee of a fair trial; but to fall into the hands of an unscrupulous mob who were acting in violation of law, particularly when law and order was broken up by the heavy tramp of war, was what we were compelled by all means to avoid. We had no alternative but to elude their search.

It is a fact well known, that in the upheaval of popular passion for the overthrow of law and order under any pretext whatever, a nucleus is formed, around which the most vile, the most turbulent, and the most cowardly instinctively fly. Cowardly villains invariably join in with every mob that comes within their reach; personal enmity and spite is frequently their controling motive; the possible opportunity of redressing some supposed grievance without incurring 38 danger to themselves is their incentive for swelling the mob. A person guilty of any particular crime, to avoid suspicion, is always the most clamorous for blood when some one else stands accused of the same offense. In the Vigilance Committee were found the same materials existing in all mobs. No brave man was ever a tyrant, but no coward ever failed to be one when he had the power. They still kept up the search for me and my brother with an energy worthy of a better cause.

It was now October, the nights were cold and we suffered much for the want of blankets and even for food. We were both unaccustomed to sleeping out at night and were chilled by the cold wind that whistled through the trees. After we had thus continued in the woods about three weeks, I concluded to venture in one night to see my family and to get something to eat, and some bed clothes to keep me more comfortable at night.

I had heard no unusual noise in the woods that day, had seen no one pass, nor heard the tramp of horses feet in any direction.

It was about eleven o‘clock at night when I got within sight of the house, no light was burning within; I heard no noise of any kind, and believing that all was right I crept up to the house and whispered “Margaret” through a crack. My wife heard me, and recognizing my voice she noiselessly opened the door and let me in. We talked only in whispers, and in a few minutes she placed my supper upon the table. Just as I was going to eat I heard the top rail fall off my yard fence. The noise did not suit me, so I took my gun in one 39 hand, a loaf of corn bread in the other, and instantly stepped out into the yard by a back door.

McIlvaine and his vigilantees were also in the yard, and were approaching the house from all sides in a regular line. In an instant I detected a gap in their ranks and dashed through it. As they commenced firing I dodged behind a molasses mill that fortunately stood in the yard, it caught nine of their bullets and without doubt saved my life. After the first volley I struck for the woods, a distance of about two hundred yards. Though their firing did not cease, I stopped midway to shoot at their flame of fire, but a thought struck me that it would too well indicate my whereabouts in the open field, so I hastened on until I had gained the edge of the woods, and there I sat down to listen at what was going on at the house. I heard Firman McIlvaine‘s name called several times, and very distinctly heard his replies and knew his voice. This satisfied me beyond all doubt that the marauders were none other than the self-styled Vigilance Committee.

I was fortunate in my escape, and had a deep sense of gratitude to heaven for my miraculous preservation. Though I had not made my condition much better by my visit, yet I gnawed away, at intervals, upon my loaf of corn bread, and tried to reconcile myself as much as possible to the terrible state of affairs then existing. I saw very plainly that my enemies would not permit me to remain in that vicinity; but the idea of being compelled to leave my dear home where I was born and raised, and to strike out into the unknown world with my family without a dollar in my pocket, 40 without anything except one horse and the clothing we had upon our backs, was anything in the world but cheering. However, I had no alternative; to take care of my dependent and suffering family, was the motive uppermost in my mind at all times.

After the mob had apparently left, my wife came out to me in the woods. Our plans were soon formed; after dressing the children, five in number, as quietly and speedily as possible, she brought them to me at a designated point among the hills in the dark forest. She returned to the house alone, and with as little noise as possible saddled up my horse, and after packing him with what bed clothing and provisions she conveniently could, she circled around among the hills and rejoined me at a place I had named in the deep forest about five miles from our once happy home. Daylight soon made its appearance and enabled me to pick out a place of tolerable security.

We remained concealed until the re-appearance of night and then proceeded on our cheerless wandering. In silence we trudged along in the woods as best we could, avoiding the mud and occasional pools of water. I carried my gun on my shoulder and one of the children on my hip; my wife, packing the baby in her arms, walked quietly by my side. I never was before so deeply impressed with the faith, energy and confiding spirit of woman. As the moon would occasionally peep forth from the drifting clouds and strike upon the pale features of my uncomplaining wife, I thought I could detect a look of cheerfulness in her countenance, and more than once I thought I heard a suppressed 41 titter when either of us got tangled up in the brush. When daylight appeared we were on Wolf creek, a few miles south of Farmington; here we stopped in the woods to cook our breakfast and to rest a while. During the day we proceeded on to what is called Flat Woods, eight miles from Farmington, in the southern part of St. Francois county, and about ten miles north from Fredericktown. From Mr. Griffin I obtained the use of a log cabin in a retired locality, and in a few minutes we were duly installed in our new house. 42

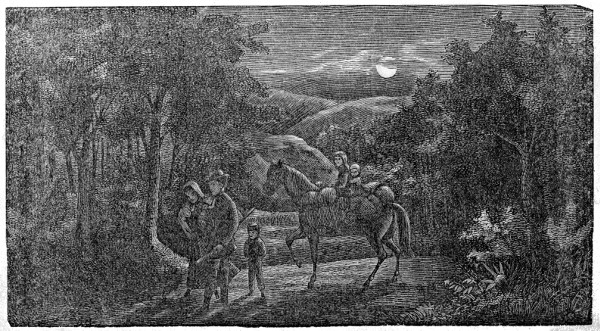

McIlvaine‘s Vigilance Mob.—Treachery of Castleman.—Frank Hildebrand hung by the Mob.—Organization of the Mob into a Militia Company.

The Vigilance Committee, with Firman McIlvaine at its head, was formed ostensibly for the mutual protection against plunderers; yet some bad men were in it. By their influence it became a machine of oppression, a shield for cowards, and the headquarters for tyranny.

After I left Big River my brother Frank continued to conceal himself in the woods until about the middle of November; the weather now grew so cold that he could stand it no longer; he took the advice of Franklin Murphy and made his way to Potosi, and in order to silence all suspicion in regard to his loyalty, he went to Captain Castleman and offered to join the Home Guards. Castleman being intimate with Firman McIlvaine, detained Frank until he had time to send McIlvaine word, and then basely betrayed him into the merciless hands of the vigilant mob.

In order to obtain a shadow of legality for his proceedings, McIlvaine took brother Frank before Franklin Murphy, who at that time was justice of the peace on Big River. Frank was anxious that the justice might try the case; but when Murphy told them that all the authority he had would only enable him to commit him to jail for trial in the proper court, even if the 43 charges were sustained, they were dissatisfied at this, and in order to take the matter out of the hands of the justice and make it beyond his jurisdiction, they declared that he had stolen a horse in Ste. Genevieve county.

The mob then took Frank to Punjaub, in that county, before Justice R. M. Cole, who told them that he was a sworn officer of the law, and that if they should produce sufficient evidence against their prisoner, he could only commit him to jail. This of course did not satisfy the mob; to take the case out of his hands, they stated that the offense he had committed was that of stealing a mule in Jefferson county. They stated also that Frank and Sam Anderson had gone in the night to the house of a Mr. Carney to steal his mare; that Mrs. Carney on hearing them at the gate, went out and told them that Mr. Carney was absent and had rode the mare; that they then compelled Mrs. Carney to go with them a quarter of a mile in her night clothes to show them where Mr. Becket lived; and finally that they went there and stole his horse. Failing however to obtain the co-operation of the Justice in carrying out their lawless designs, the mob left with their prisoner, declaring that they were going to take him to Jefferson county for trial.

The sad termination of the affair is soon told. The mob took my kind, inoffensive brother about five miles and hung him without any trial whatever, after which they threw his body in a sink-hole thirty feet in depth, and there his body laid for more than a month before it was found. A few weeks after this cold blooded 44 murder took place, Firman McIlvaine had the audacity to boast of the deed, declaring positively that Frank had been hung by his express orders. This murder took place on the 20th day of November, 1861, about a month after I had been driven from Big River.

A few nights after my arrival at Flat Woods I made my way back to my old home in order to bring away some more of my property, but on arriving there I found that my house had been robbed and all my property either taken away or destroyed. I soon learned from a friend that the Vigilance Committee had wantonly destroyed everything that they did not want. I returned to Flat Woods in a very despondent mood. I was completely broken up.

The union men were making war upon me, but I was making no war upon them, for I still wished to take no part in the national struggle. I considered it “a rich man‘s war and a poor man‘s fight.” But a sense of my wrongs bore heavily upon me; I had been reduced to absolute poverty (to say nothing of the murder of my brother) by the unrelenting cruelty of Firman McIlvaine who was a rich man, drowned in luxury and surrounded by all the comforts of life that the eye could wish, or a cultivated appetite could desire.

The war was now raging with great fury in many sections of the country; yet I remained at home intent on making a living for my family, provided I could do so without being molested, but during all the time I was at work, I had to keep a sharp lookout for my enemies. 45

FRANK HILDEBRAND HUNG BY THE MOB.

46

47

That leprous plague spot—the Vigilance Committee—finally ripened and culminated in the formation of a company of militia on Big River, with James Craig for Captain and Joe McGahan for First Lieutenant. The very act for which they were so anxious to punish others, on mere suspicion, they themselves now committed with a high hand.

They were ordered to disarm southern sympathizers and to seize on articles contraband of war, such as arms and ammunition. This gave them great latitude; the cry of “disloyal” could be very easily raised against any man who happened to have a superabundance of property. “Arms” was construed also to include arm chairs and their arms full of everything they could get their hands on; “guns” included Gunn‘s Domestic Medicine; a fine claybank mare was confiscated because she looked so fiery, and a spotted mule because it had so many colors; they took a gun from Mr. Metts merely because he lived on the south side of Big River; they dipped heavily into the estate of Dick Poston, deceased, by killing the cattle for beef and dividing it among themselves, under the pretext that if Dick Poston had been living, he most undoubtedly would have been a rebel. 48

His house at Flat Woods attacked by Eighty Soldiers.—Wounded.—Miraculous Escape.—Captain Bolin.—Arrival in Green County, Arkansas.

In April, 1862, after we had lived at Flat Woods during six months of perfect tranquility, that same irrepressible Vigilance Committee, or some men who had composed it, learned finally that I was living at Flat Woods. Firman McIlvaine and Joe McGahan succeeded in getting eighty soldiers from Ironton to aid in my capture. I had been hauling wood; as soon as I unloaded the wagon I stepped into the house, and the first thing I knew, the eighty soldiers and the vigilantees were within gunshot and coming under full charge. I seized my gun and dashed through a gap in their lines that Heaven had again left open for my escape. They commenced firing upon me as soon as I was out of the house. The brush being very thick not far off, I saw that my only chance was to gain the woods, and that as soon as possible. I ran through the garden and jumped over a picket fence—this stopped the cavalry for a moment. I made through the brush; but out of the hundreds of bullets sent after me, one struck my leg below the knee and broke a bone. I held up by the bushes as well as I could, to keep them from knowing that I was wounded. While they had to stop to throw down a fence, I scrambled along about 49 two hundred yards further, and crouched in a gully that happened to be half full of leaves; I quickly buried myself completely from sight. The soldiers were all around in a short time and scoured the woods in every direction; then they went back and burned the house and everything we had, after which they left and I saw them no more.

Sixteen of Captain Bolin‘s men on the day before had been seen to cross the gravel road; this, probably, was why the federal soldiers did not remain longer. Captain Bolin was a brave rebel officer, whose headquarters were in Green county, Arkansas, and under whose command some of the most daring spirits who figured in the war, were led on to deeds of heroism scarcely ever equaled.

Our condition was truly deplorable; there I lay in the gully covered up with leaves, with one leg rendered useless, without even the consolation of being allowed to groan; my family, too, were again without shelter; the soldiers had burned everything—clothes, bedding and provisions.

As I lay in that gully, suffering with my wounds inflicted by United States soldiers, I declared war. I determined to fight it out with them, and by the assistance of my faithful gun, “Kill-devil,” to destroy as many of my blood-thirsty enemies as I possibly could. To submit to further wrong from their hands would be an insult to the Being who gave me the power of resistance.

After the soldiers had left, my wife came in search of me, believing that I was wounded from the manner 50 in which I seemed to run. I told her to go back, that I was not hurt very bad, and that when she was satisfied that no one was watching around, to come at night and dress my leg. She went, however, in search of some friend on whom we could rely for assistance. Fortunately she came across Mr. Pigg, to whom she related the whole circumstance, and he came immediately to my relief. He was a man of the right stripe; regardless of consequences, he did everything in his power to relieve my suffering, and to supply my family with bedding and provisions. He removed us by night to a place of safety, and liberally gave us all we needed. While I thus lay nursing my wound, my place of concealment was known only to a few men whom we could easily trust.

In my hours of loneliness I had much time for reflection. The terrible strait in which I found myself, naturally led me to the mental inquiry: “Have I the brand of Cain, that the hands of men should be turned against me? What have I done to merit the persecution so cruel and so persistent?” I could not solve the questions; in the sight of a just God I felt that I did not merit such treatment. Sometimes I half resolved to go into some other State on purpose to avoid the war; but I was constantly warned by my friends who were southern men, (the only men with whom I could hold communication at present,) that it would be unsafe to think of doing so, and that my only safety lay in my flight to the southern army. The vigilance mob had nearly destroyed every vestige of sympathy or good feeling I had for the union people. They had 51 reported me, both to the civil and military authorities, as being a horse thief, and, withal, a very dangerous man.

On thinking the matter over I lost all hope of ever being able to reinstate myself in their favor and being permitted to enjoy the peaceful privileges of a quiet citizen. The die was cast—for the sake of revenge, I pronounced myself a Rebel.

I remained very quietly at my place of concealment while my wife doctored my wounded leg for a week before my friend had an opportunity of sending word to any of Captain Bolin‘s men to come to my relief. As soon as my case was made known to them, however, a man was dispatched to see me for the purpose of learning all the particulars in the case. He came and asked me a great many questions, but answered none. When he arose to depart he only said, “all right—rest easy.”

The next night I was placed in a light spring wagon among some boxes of drugs and medicines, and was told that my wife and family would be taken to Bloomfield by Captain Bolin in a short time, and protected until I could come after them. A guard of two men accompanied us, and rode the whole night without speaking a word to any one. Nearly the whole route was through the woods, and although the driver was very watchful and used every precaution against making a noise, yet in the darkness of the night I was tumbled about among the boxes pretty roughly.

When daylight came we halted in a desolate looking country, inhabited only by wild animals of the forest. 52 We had traveled down on the western side of St. Francois river, and were now camped near the most western bend on that river near the southern line of Madison county; we remained all day at that point, and I spent most of my time in sleeping. When the sun had dipped behind the western hills we again commenced our journey. Our course seemed to bear more to the eastward than it did the night before, and as we were then in a country not so badly infested with Federals, we traveled a good part of our time in narrow, crooked roads, but they were rough beyond all description, and I was extremely glad when about eight o‘clock in the morning we halted for breakfast on the western bank of St. Francois river, about midway between Bloomfield, in Stoddard county, and Crane creek, in Butler.

While resting here a scouting party from General Jeff. Thompson‘s camp came riding up.

“Well boys! what have you in your wagon?”

“Drugs and medicines for Captain Bolin‘s camp.”

On hearing this they dismounted and kept up a lively conversation around the camp fire. Among their number was a jovial fellow who kept the rest all laughing. I thought I knew the voice, and as I turned over to peep through a hole in the wagon bed, he heard me and sprang to his feet.

“Who in thunderation have you in the wagon?”

“Some fellow from St. Francois county, wounded and driven off by the Federals.”

“The devil! why that is my native county. I‘ll take a look at that fellow. It‘s Sam Hildebrand as I live! How do you do, old rapscallion?” 53

“Well, well, if I haven‘t run across Tom Haile, the dare-devil of the swamps!”

“Old ‘drugs and medicines‘ what are you doing here? trying to pass yourself off for a great medicinal root I suppose. Do you feel tolerable better? I‘m afraid you are poison. Say, Sam, did you bring some good horses down with you?”

“Hush Tom! if they find out that I‘m not a horse thief, they will drum me out of camp!”

The party soon prepared to start; the first man who attempted to mount came near being dashed to the ground in consequence of the rattling of a tin cup some one had tied to his spur. Tom said it was a perfect shame to treat any man in that way; the man seemed to think so, too, judging from the glance he cast at Tom. But they mounted, dashed through a sheet of muddy water, then over a rocky point, and soon were far away amid the dim blue hills.

We started on, and after traveling until about midnight, we reached the State line between Missouri and Arkansas, there we remained until morning; on starting again we were in Green county, Arkansas, and sometime during the day we arrived safely at the Headquarters of Captain Bolin, and I was welcomely received into the little community of families, who were here assembled for mutual protection—most of them were the families of Captain Bolin‘s men. I received every attention from them that my necessities required, and as my wound seemed to be doing well, I felt for a time quite at home. 54

Interview with Gen. Jeff. Thompson.—Receives a Major‘s Commission.—Interview with Captain Bolin.—Joins the “Bushwhacking Department.”

Captain Bolin with most of his forces were somewhere in the vicinity of Bloomfield, Missouri, and as I was anxious to identify myself with the army, I got the use of a horse as soon as I was able to ride, and in company with several others proceeded across the swampy country east of the St. Francis river, for the purpose of joining General Jeff. Thompson. I reached his headquarters in safety, and stayed about camp, frequently meeting acquaintances from Missouri and occasionally getting news from home. As soon as I could gain admission to the General‘s headquarters I did so, and he received me very kindly. He listened very attentively to me as I proceeded to state my case to him—how my brother had been murdered, how I had barely escaped the same fate, and how I had finally been driven from the country.

General Thompson reflected a few moments, then seizing a pen he rapidly wrote off a few lines and handing it to me he said, “here, I give you a Major‘s commission; go where you please, take what men you can pick up, fight on your own hook, and report to me every six months.” I took the paper and crammed it down into my pantaloon‘s pocket and walked out. I 55 could not read my commission, but I was determined to ask no one to read it for me, for that would be rather degrading to my new honor.

I retired a little distance from camp and taking my seat on an old cypress log, I reflected how the name of “Major Sam Hildebrand” would look in history. I did not feel comfortable over the new and very unexpected position in which I had been placed. I knew nothing of military tactics; I was not certain whether a Major held command over a General or whether he was merely a bottle washer under a Captain. I determined that if the latter was the case, that I would return to Green county and serve under Captain Bolin.

As I had no money with which to buy shoulder-straps, I determined to fight without them. I was rather scarce of money just at that time; if steamboats were selling at a dollar a piece, I did not have money enough to buy a canoe paddle. I stayed in camp, however, several days taking lessons, and hearing the tales of blood and pillage from the scouts as they came in from various directions.

By this time my wound felt somewhat easier, so I mounted my horse and made my way back to Green county, and arrived safely at Captain Bolin‘s headquarters. The Captain was at home, and I immediately presented myself before him. He said he had heard of me from one of his scouts, and was highly gratified that one of his men had seen proper to have me conveyed to his headquarters.

“I presume,” said he, “that you have been to the 56 headquarters of General Jeff. Thompson. Did you see the ‘Old Swamp Fox?‘”

“I did.”

“What did he do for you?”

Here I pulled my commission from my pocket, that now looked more like a piece of gunwadding than anything else, and handed it to the Captain.

“Well, Major Hildebrand—”

“Sam, if you please.”

“Very well then, what do you propose to do?”

“I propose to fight.”

“But Major—”

“Sam, if you please.”

“All right, sir! Sam, I see that you have the commission of a Major.”

“Well Captain, I can explain that matter: he formed me into an independent company of my own—to pick up a few men if can get them—go where I please—when I please—and when I go against my old personal enemies up in Missouri, I am expected to do a Major part of the fighting myself.”

At this the Captain laughed heartily, and after rummaging the contents of an old box he drew forth something that looked to me very much like a bottle. After this ceremony was over he remarked:

“Well sir, the commission I obtained is of the same kind. I have one hundred and twenty-five men, and we are what is denominated ‘Bushwhackers‘; we carry on a war against our enemies by shooting them; my men are from various sections of the country, and each one perhaps has some grievance to redress at home; in 57 order to enable him to do this effectually we give him all the aid that he may require; after he sets things to right in his section of country, he promptly comes back to help the others in return; we thus swap work like the farmers usually do in harvest time. If you wish an interest in this joint stock mode of fighting you can unite your destiny with ours, and be entitled to all our privileges.”

Captain Bolin‘s proposition was precisely what I so ardently desired. Of the real merits of this war I knew but little and cared still less. To belong to a large army and be under strict military discipline, was not pleasing to my mind; to be brought up in a strong column numbering several thousands, and to be hurled in regular order against a mass of men covering three or four miles square, against whom I had no personal spite, would not satisfy my spirit of revenge. Even in a fierce battle fought between two large opposing armies, not more than one man out of ten can succeed in killing his man; in a battle of that kind he would have no more weight than a gnat on a bull‘s horn.

I was fully satisfied that the “Bushwhacking department” was the place for me, with the continent for a battle field and the everlasting woods for my headquarters. 58

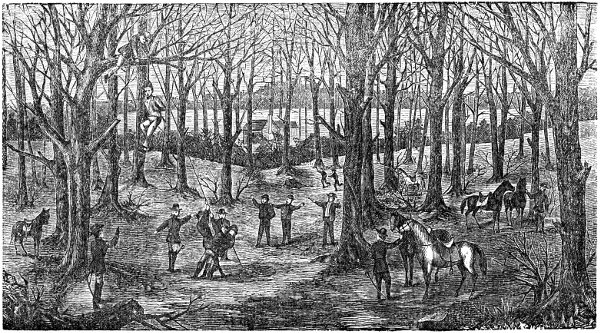

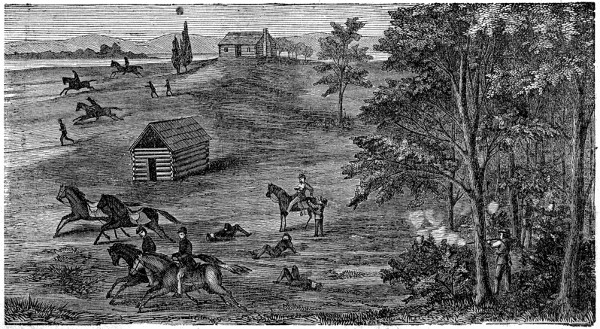

Trip to Missouri.—Kills George Cornecious for reporting on him.—Kills Firman McIlvaine.—Attempt to kill McGahan and House.—Returns to Arkansas.

My wound kept me at headquarters for about six weeks after my arrival in Arkansas. During all this time I could not hear a word from my family, for the Federals had possession of every town in that section of country, together with all the roads leading from one county to another.

On the 1st day of June, 1862, having been furnished a horse, I took my faithful gun, “Kill-devil,” and started on my first trip back to Missouri. As my success would depend altogether on the secrecy of my movements, I went alone. I traveled altogether in the night, and most of the time through the woods. From Captain Bolin‘s men I had learned the names of Southern sympathizers along the whole route, so I made it convenient to travel slowly in order to favor my wounds and to get acquainted with our friends.

I arrived in the vicinity of Flat Woods, in St. Francois county, Missouri, on the 12th day of June, and immediately commenced searching for George Cornecious, the man who reported my whereabouts to McIlvaine and the soldiers, thereby causing me to be wounded and expelled from Flat Woods. After searching two days and two nights I succeeded in shooting 59 him; he was the first man I ever killed; a little notch cut in the stock of my gun was made to commemorate the deed.

To avoid implicating my family in any way with my transactions, I satisfied myself with exchanging words with my wife through a friend who was thought by his neighbors to be a Union man. My family resided in a little cabin on Back creek, and my wife was cultivating a garden.

To carry out the darling object I had in view—that of killing Firman McIlvaine—I went to Flat river, and after remaining several days, I took a pone of bread for my rations and walked to his farm on Big river after night.

I passed through his fields, but finding no place where harvesting was going on, I crossed Big river on a fish-trap dam and ranged over the Baker farm on the opposite side of the river, about a mile above Big river Mills, where the McIlvaine family now resided.

I found where harvesting had just commenced in a field which formed the southwestern corner of the farm. This field is on the top of a perpendicular bluff, about one hundred feet high, and is detached from the main farm by a road leading from Ste. Genevieve to Potosi.

A portion of the grain had already been cut on the western side of the field, near the woods; there I took my station in the fence corner, early in the morning, thinking that McIlvaine would probably shock the grain while the negroes were cradling. In this I was mistaken, for I saw him swinging his cradle in another part of the field, beyond the range of my gun. 60

I next attempted to crawl along the edge of the bluff among the stunted cedars, but had to abandon the attempt because the negroes stopped in the shade of the cedars every time they came around. Then I went back into the woods, and passed down under the bluff, along the edge of the river, until I got opposite the place where they were at work; but I found no place where I could ascend the high rock. I went around the lower end of the bluff, and crawled up to the field on the other side, but I was at too great a distance to get a shot. Finally, I went down to the river and was resting myself near a large flat rock that projected out into the river, where some persons had recently been fishing, when suddenly Firman McIlvaine rode down to the river and watered his horse at a ford about sixty yards below me. I tried to draw a bead on him, but the limb of a tree prevented me, and when he started back he rode too fast for my purpose.

At night I crept under a projecting rock and slept soundly; but very early in the morning I ascended the bluff and secreted myself at a convenient distance from where they had left off cradling. But I was again doomed to disappointment, for, as the negroes were cradling, McIlvaine was shocking the grain in another part of the field.

In the evening, as soon as they had finished cutting the grain, all hands left, and I did not know where they were. I next stationed myself at a short distance from the river, and watched for him to water his horse; but his father presently passed along leading the horse to water. 61

KILLING McILVAINE.

62 63

I again slept under the overhanging rock; and on the next morning (June 23d) I crossed the river on the fish dam, and went to the lower part of McIlvaine‘s farm. There I found the negroes cutting down a field of rye. They cut away for several hours, until they got it all down within one hundred yards of the fence, before McIlvaine made his first round. On getting a little past me, he stopped to whet his scythe; as soon as he had done so he lowered the cradle to the ground, and for a moment stood resting on the handle.

I fired, and he fell dead.

Nothing but a series of wrongs long continued could ever have induced me to take the life of that highly accomplished young man.

After the outbreak of the war, while others were losing horses, a fine mare was stolen from him. The theft was not committed by me, but my personal enemies probably succeeded in making him believe that I had committed the act.

He was goaded on by evil advisers to take the law into his own hands; my brother Frank was hung without a trial, and his body thrown into a sink-hole, to moulder like that of a beast; my own life had been sought time and again; my wife and tender family were forced to pass through hardships and suffering seldom witnessed in the annals of history. The mangled features of my poor brother; the pale face of my confiding wife; the tearful eyes of my fond children—all would seem to turn reprovingly upon me in my midnight dreams, as if demanding retributive justice. 64 My revenge was reluctant and long delayed, but it came at last.

I remained in the woods, near the residence of a friend for a day or two, and then I concluded to silence Joe McGahan and John House before returning to Arkansas. I proceeded to the residence of the former, who had been very officious in the Vigilance mob, and posted myself in some woods in the field within one hundred yards of the house, just as daylight began to appear. I kept a vigilant watch for him all day, but he did not make his appearance until it had commenced getting dark; then he rode up and went immediately into his house. By this time it was too dark for me to shoot at such a distance. I moved to the garden fence, and in a few minutes he made his appearance in the door with a little child in his arms. The fence prevented me from shooting him below the child, and I could not shoot him in the breast for fear of killing it.

He remained in the door only a minute or two, and then retired into the house; and while I was thinking the matter over, without noticing closely for his reappearance, I presently discovered him riding off. I went to a thicket in his field and slept until nearly day, when I again took my position near the house, and watched until night again set in, but fortunately for him he did not make his appearance.

I now went about four miles to the residence of John House, selected a suitable place for my camp, and slept soundly until daybreak. I watched closely all day, but saw nothing of my enemy. As soon as it was dark I went back to Flat river, and on the next night I 65 mounted my horse and started back to Green county, Arkansas, without being discovered by any one except by those friends whom I called on for provisions. 66

Vigilance mob drives his mother from home.—Three companies of troops sent to Big river.—Captain Flanche murders Washington Hildebrand and Landusky.—Captain Esroger murders John Roan.—Capt. Adolph burns the Hildebrand homestead and murders Henry Hildebrand.

I shall now give a brief account of the fresh enormities committed against the Hildebrand family. The same vindictive policy inaugurated by the Vigilance mob was still pursued by them until they succeeded, by misrepresentation, in obtaining the assistance of the State and Federal troops for the accomplishment of their designs.

A Dutch company, stationed at North Big River Bridge, under Capt. Esroger; a Dutch company stationed at Cadet, under Capt. Adolph, and a French company stationed at the Iron Mountain, under Capt. Flanche, were all sent to Big River to crush out the Hildebrand family.

Emboldened by their success in obtaining troops, the Vigilance mob marched boldly up to the Hildebrand homestead and notified my mother, whom they found reading her Bible, that she must immediately leave the county, for it was their intention to burn her house and destroy all her property.

My mother was a true Christian; she was kind and affectionate to everybody; her hand was always ready 67 to relieve the distressed, and smooth the pillow for the afflicted; the last sight seen upon earth by eyes swimming in death has often been the pitying face of my mother, as she hovered over the bed of sickness.

I appeal to all her neighbors—I appeal to everybody who knew her—to say whether my mother ever had a superior in this respect.

When ordered to leave her cherished home, to leave the house built by her departed husband, to leave the quiet homestead where she had brought up a large family, and where every object was rendered dear by a thousand sweet associations that clung to her memory, she turned her mind inwardly, but found nothing there to reproach her; then to her God she silently committed herself.

She hastily took her Bible and one bed from the house—but nothing more. She had arrangements made to have her bed taken to the house of her brother, Harvey McKee, living on Dry Creek, in Jefferson county, distant about thirty five miles. Then, taking her family Bible in her arms, she burst into a flood of tears, walked slowly out of the little gate, and left her home forever!

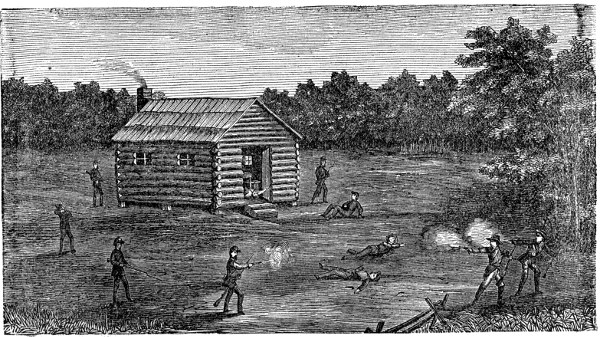

I will here state that I was the only one of the Hildebrand family who espoused the Rebel cause. After the murder of my brother Frank, I had but three brothers left: William, Washington and Henry. William joined the Union army and fought until the close of the war. Washington took no part in the war, neither directly nor indirectly. Never, perhaps, was there a more peaceable, quiet and law-abiding 68 citizen than he was; he never spoke a word that could be construed into a sympathy for the Southern cause, and I defy any man to produce the least evidence against his loyalty, either in word or act. While the war was raging, he paid no attention to it whatever, but was busily engaged in lead mining in the St. Joseph Lead Mines, three miles from Big River Mills, and about six miles from the old homestead. In partnership with him was a young man by the name of Landusky, a kind, industrious, inoffensive man, whose loyalty had never once been doubted. My sister Mary was his affianced bride, but her death prevented the marriage.

My brother Henry was a mere boy, only thirteen years of age. Of course he was too young to have any political principles; he was never accused of being a Rebel; no accusation of any kind had ever been made against him; he was peaceable and quiet, and, like a good boy, he was living with his mother, and doing the best he could toward supporting her. True, he was very young to have the charge of such a farm, but he was a remarkable boy. Turning a deaf ear to all the rumors and excitements around him, he industriously applied himself to the accomplishment of one object, that of taking care of his mother.

On the 6th day of July, 1862, while my brother Washington and Mr. Landusky were working in a drift underground, Capt. Flanche and his company of cavalry called a halt at the mine, and ordered them to come up; which they did immediately. 69

FEDERAL ATROCITY.

70 71

No questions were asked them, and no explanations were given. Flanche merely ordered them to walk off a few steps toward a tree, which they did; he then gave the word “fire!” and the whole company fired at them, literally tearing them to pieces!

I would ask the enlightened world if there ever was committed a more diabolical deed? If, in all the annals of cruelty, or in the world‘s wide history, a murder more cold-blooded and cruel could be found?

A citizen who happened to be present ventured to ask in astonishment why this was done; to which Flanche merely replied, as he rode off, “they bees the friends of Sam Hildebrass!”