Title: The Girl's Own Paper, Vol. XX, No. 985, November 12, 1898

Author: Various

Release date: December 5, 2015 [eBook #50615]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Susan Skinner, Chris Curnow, Pamela Patten and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

| Vol. XX.—No. 985.] | NOVEMBER 12, 1898. | [Price One Penny. |

[Transcriber's Note: This Table of Contents was not present in the original.]

"OUR HERO."

HENRY PURCELL: THE PIONEER OF ENGLISH OPERA.

WORDS TO THE WISE OR OTHERWISE.

ORPHEUS.

FATHER ANTHONY.

CHINA MARKS.

ABOUT PEGGY SAVILLE.

"IN MINE HOUSE."

ANSWERS TO CORRESPONDENTS.

THE GIRL'S OWN QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS COMPETITION.

A TALE OF THE FRANCO-ENGLISH WAR NINETY YEARS AGO.

By AGNES GIBERNE, Author of "Sun, Moon and Stars," "The Girl at the Dower House," etc.

All rights reserved.]

ON PAROLE.

If the shock of this abrupt arrest of the whole body of English travellers, who happened to be within reach of the First Consul, fell sharply on those at home, it fell at least no less sharply on those who were arrested.

An official notice was served upon all who could, by the utmost stretching, be accounted amenable to the act. In that notice, received alike by Colonel Baron and by Denham Ivor, they were informed that—"All the English enrolled in the Militia, from the ages of eighteen to sixty, or holding any commission from His Britannic Majesty, shall be made prisoners of war;"—the reason given being the same as was alleged in the version which speedily appeared in English papers.

The mention of the Militia was, however, additional; and there was something else also. It might fairly have been argued that professional men, men of business, and men of no particular employment, could not be included in the above statement. To guard against such reasoning the document went on to explain—"I tell you beforehand that no pretext, no excuse, can exclude you; as, according to British law, none can dispense you from serving in the Militia."

This notion was made the basis for a far more sweeping arrest than had at first been supposed possible. Not only officers in the Army and Navy, who were then in France or in other countries under the dominion of Napoleon, not only men who had served or who might be called upon to serve in the Militia, but lawyers and doctors, clergymen and men of rank, men of business and men in trade, all alike were detained, all alike were forced immediately to constitute themselves prisoners of war upon parole, with only the alternative of becoming prisoners of war in prison, instead of upon parole.

Those who consented to give their word of honour not to attempt to escape were allowed to remain at large, and to lodge where they would, under certain limitations. That is to say, they had to live in specified places, where they were under the continual inspection of the gendarmerie, and where they had at regular intervals to report themselves. Whether they were soldiers, sailors, clergymen, or business men, they were thus at once cut off from their work in life, and many were debarred from their only means of livelihood.

As a first move, the mass of the Paris détenus were ordered to Fontainebleau; and thither Colonel and Mrs. Baron had to betake themselves. Thither also Denham Ivor would speedily have to follow: though, on the score of danger to others from infection, a few days' delay was permitted.

The question had at once arisen whether Mrs. Baron should not be sent to England with Roy, as soon as the boy might be fit to travel, since women were theoretically free to go where they would, provided only that they could obtain passports. But Mrs. Baron refused to consider any such proposal. She could not and would not be separated from her husband. "Of course I shall go to Fontainebleau," she said decisively. "It cannot be for long. Roy must come to us there. It only means leaving his schooling for a quarter of a year; and he will not be strong enough for lessons at present. Something is sure to be arranged soon, and then we shall all go home together."

Others were less sanguine of a quick release; but Colonel Baron could seldom stand out against his wife, when she set her dainty foot down. He made a half struggle, and won from her a promise that, if he should be ordered farther away, she would then consent to Roy's being sent home. Beyond that he failed to get his own way.

Long before Roy could be counted safe for even the short journey to Fontainebleau, Denham had an intimation that his going thither might be no longer deferred. Thus far he had not thought it needful to tell the boy what had happened; but now the telling had become a necessity.

"Den, I want to look out of the window. Oh, let me look out," entreated Roy, as the heavy beat of a drum sounded. He wriggled on the hard sofa, where he had begun to spend a part of each day. Roy had grown thin, and his eyes blinked weakly when turned to the light.

"You want to see the soldiers?"

"Yes. Do let me. May I try to walk to the window all alone? I know I can."

Ivor laughed, though not mirthfully. "Try!" he answered, and Roy made a brave attempt, actually reaching the window without being helped.

"Come, that was good. You are getting on nicely. Now sit down, and look out for the soldiers. I think they are coming this way."

The boy gazed eagerly, flushing.

"I wish they were English," he said. "I wish I was in England. When are we going home, Den? And when may I see my mamma? I do want to have Molly again. It's ages since I saw Molly—and I want her!"

Denham was silent.

"It was stupid of me to be so glad to come away from Molly. Nothing is half nice without her."

"I am glad you have found that out. She is a dear little sister, and she would do anything in the world for you."

"Oh, well, of course, I know she would," assented Roy. "And I always was fond of Molly too. She gets cross sometimes, though."

"Roy never gets cross, I suppose?"

Roy laughed rather consciously, and then gave vent to a sigh. "Oh, dear, I don't like this chair. Not half so much as the sofa. It makes me tired. I wish nobody ever had the small-pox. When shall I be all right again, I wonder? I do hate being ill such a tremendously long time."

Denham picked him up bodily, as if he had been an infant, carried him across, and deposited him where he had been before.

"You have done about enough for one day. Oh, you will soon be well now; no fear! And you may count yourself fortunate, not to have been much worse. Yours has been a slight attack, compared with what many people have."

"I don't call it slight. I call it a most beastly horrid illness. Den, when shall we go home? I want Molly."

Denham took a seat by his side.

"I am not sure. It may not be just yet."

"Why not? I thought we were going as soon as ever we could."

"As soon as possible; yes. The question is, how soon that will be. Some of us are not able to go yet; but I am hoping that your father will send you home, and not let you wait for him and me."

"Why, Den?" Roy twisted round to gaze in astonishment. "Why, Den! I thought you were all waiting, only just till I should get over this. I didn't know there was anything else. Is there anything else? Has something happened? Do tell me."

"You and your mother are free to go back to England, as soon as she is willing to do so. Your father and I are not free."

"Aren't you? Why not? What is the matter with papa?"

"Nothing is the matter with him, so far as health is concerned. Only, he is not free and I am not free. We are both prisoners."

Roy's large grey eyes grew bigger and rounder.

"Den! Why—Den—what can you mean? Prisoners! You and papa prisoners! Why, you haven't been fighting."

"No, we have not been fighting. We ought not to be prisoners. Such a thing has never happened before, in any war between civilised countries. But war has been declared, as you know was expected before you were taken ill. And one of the first things that Napoleon did, directly war broke out, was to make all English travellers prisoners of war."

Roy clenched his fist.

"He professes to have had provocation. There were French vessels in our ports, and these were seized, as soon as our Ambassador had been ordered to return home. But that was in accordance with a very old custom—centuries old. Napoleon's act of reprisal is altogether new. It is a thing unheard of—making war on travellers and peaceful residents; a disgrace to himself and his nation. You know what is meant by 'reprisals' in war. This is his 'reprisal' for the vessels seized. Every Englishman in France, or in any country under Napoleon's sway at this moment, is declared to be a prisoner."

"Then I'm a prisoner too."

"You are under age. Some boys of your age have been arrested, I believe, but only because they hold His Majesty's Commission in the Navy. Otherwise, under eighteen you are free."

"But you are not in prison."

"I am on parole. I have given my word of honour not to try to get away."

"Then you mustn't escape, even if you can?"

"No. If I had refused to give my parole, I should have been at once sent{99} to prison—probably have been thrown into a dungeon."

The boy was as white as a sheet.

"And papa——?"

"Has given his parole also."

"And—mamma?"

"Your mother is at liberty to go home, and your father wishes her to do so, and to take you; but she says she will not leave him. One can understand her feeling, and yet it is a pity. In England she would be safer and better off. But you know how unhappy she always is, if she is away from your father even for a few days. You, of course, will have to be sent home soon, so as to go on with your schooling; but at first you will join us at Fontainebleau. We hope to be all released in a very little while. The thing is so disgraceful, that Napoleon can hardly persevere in it—so most people say. But we shall soon see. If we are not soon set free, your father will no doubt try to persuade your mother to take you home."

"Where is Fontainebleau?"

"Some distance from Paris. Don't you know the name? Your father and mother are there already, and now I have to go too. I have only been allowed to wait for a few days, because of your illness, and I must not put off any longer."

"Are you going soon? Will you take me?"

"Not just yet, my boy. You are hardly fit for the journey. A chill might lay you by again; besides, other people might catch the small-pox from you. So I have settled to leave you here a little longer, in charge of kind Mademoiselle de St. Roques. She and Monsieur and Madame de Bertrand will see well after you."

Roy looked very doleful.

"When are you going?"

"I am afraid—to-morrow. But for that I would not have told you quite so soon. But you will keep up a brave heart. You are a soldier's son, you know, so you mustn't give in."

Roy's face worked.

"I don't want you to go," he said. "That horrid old beast of a Napoleon; I wish somebody or other would guillotine him—that I do! He deserves it richly! Must you go?"

"I'm afraid I have no choice. The gendarmes have been looking me up; and if I put off any longer I shall get into trouble with those gentlemen. I'm bound to report myself at Fontainebleau before the evening of the day after to-morrow. But you will soon come after me. Why—Roy!"

"I can't help it. It's so horrid," sobbed Roy, direfully ashamed of himself. "I—don't like you to go. I don't like you and papa to be prisoners. And oh—poor little Molly! What will she do! Den, why does God let such wicked men be in the world? I wouldn't. I'd kill them right off."

"One can't always see the reason. Some good reason there must be."

"I don't know how there can be! It's all as horrid as horrid, and everything is miserable!" The boy rubbed his coat-sleeve across his eyes, only to burst out sobbing afresh. "I can't help it," he gasped. "Oh, please don't ever tell Molly."

"No, I will not. But Molly would understand. It is only that you are pulled down and weak. In a few days you will not feel inclined to cry. Never mind, Roy, things will be better by-and-by. You see, you and I can't help what Buonaparte does. He has to answer for himself. You and I have only to see that we do our part in life bravely and rightly and truly. This is rather hard to bear, but it has to be borne, and we must try and be cheery for the sake of other people. Don't you see?"

Something in the young man's voice made Roy ask, "Do you mind very, very much?"

"What do you think? Wouldn't you mind in my place? Roy—if you have Molly at home, I have—Polly!"

"Oh, it's just perfectly horrid!" sobbed Roy. "It's just as beastly as it can be!"

Roy had good reason to talk of "poor little Molly." Molly's state of mind during many days bordered on despair—so far as despair is possible to a healthy child. The very idea that weeks and months might pass before she could again see her beloved twin-brother was too dreadful.

"Roy will be sent home, of course. It is out of the question that he should be allowed to stay in France. Think of the boy's education," Mrs. Fairbank said repeatedly. But others were not so sure.

There is much variety in the different accounts given at the time, as to the number of English subjects who actually suffered arrest. Some estimates amount to as high a figure as ten thousand, but these appear to make no allowance for the rapid homeward rush just at the last. This assertion may be found in Sir Walter Scott's writings, which does not settle the matter, since strict accuracy was not his peculiar gift. Other estimates give only a few hundreds as the number detained, most of them belonging to upper ranks in society.

A burning outburst of indignation took place throughout England, and the newspapers vied one with another in wrathful condemnation of the "unmannerly violation of the laws of hospitality."

One serious complication of affairs, which perhaps had not been foreseen by the First Consul, when he took this step, was a deadlock in the exchange of prisoners, usual in war between civilised nations.

It was impossible for the English Government to recognise that men so unjustly seized were lawful prisoners of war, by consenting to release, in exchange for them, French prisoners lawfully taken. Indeed, from that date exchange practically ceased altogether; English prisoners having to languish in France, and French prisoners having to languish in England, without this hope of gaining their freedom before the close of the war. Some few exceptions were made in later years, but not many.

After a time an attempt was made by the body of détenus themselves—this being the name that they were known by, in distinction from regular and lawfully-made prisoners—to obtain their release. They sent a carefully-worded petition to the French Minister of War, entreating to be set free, and offering, if their petition were granted, to pay out of their own pockets the value of those vessels which had been first seized by the English, as well as to do their utmost to obtain the release of the French sailors who had been on board those vessels. This request was flatly refused. The French Minister, in his reply, plainly declared that the English had not been detained merely on account of those captured vessels, as was stated in Napoleon's manifesto, but for other reasons as well.

War, once begun, was carried on with energy by both the English and the French. Napoleon marched his troops about Europe, as it pleased him, meeting with little or no resistance. Germany, Austria, and other nations, all meekly and tamely submitted; the only continental power which had the pluck to offer even a faint resistance at that date being little Denmark. Great Britain alone faced the usurper with a scornful and fearless determination; and the most ardent desire of Napoleon's heart was to crush the haughty island, which would have none of his pretensions, and which refused to bow before him.

As a first step, he did his best to damage English commerce, by closing continental markets against her—supremely careless of the suffering which, by this move, he inflicted on his own friends and subjects. But at this particular game England was the better hand of the two. At that time ironclads were unknown; and though the great three-deckers, with their fifty or seventy guns a-piece, could not be built in a day, yet war vessels were of every description, from such three-deckers down to merchant ships, hastily fitted with a few guns, and sent forth to do their best. In a short time England had about five hundred war vessels of divers kinds, large or small, with which she swept the seas, recaptured such colonies as had been yielded to France by the Treaty of Amiens, blockaded harbours in countries subject to the First Consul, and made descents upon French ports, carrying off prizes in the very teeth of French guns and fortifications.

Napoleon's next move was definitely to announce his intention of invading England, of conquering the country, and of making it into a province of France—a feat more easily talked of than accomplished. But preparations for this scheme were pushed forward on a great scale. Huge flotillas of flat-bottomed boats, to act as transport for the invading army, were collected at various places, more especially at Boulogne; and at the latter spot a camp was formed of about one hundred thousand soldiers, to be in readiness for the moment of action. Also a fleet of French men-of-war was being prepared to convoy the flat-bottomed boats full of soldiers across the Channel.

(To be continued.)

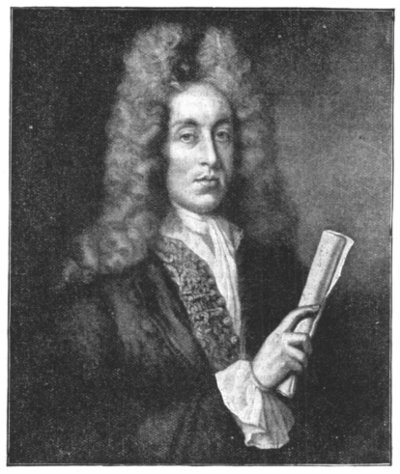

By ELEONORE D'ESTERRE-KEELING.

On the 25th of November, 1680, there appeared in the columns of the London Gazette the following announcement:—

"Josias Priest, who kept a boarding-school of gentlewomen in Leicester Fields, is removed to the great schoolhouse at Chelsey that was Mr. Portman's. There will continue the same masters and others to the improvement of the said school."

Leicester Fields was in 1680 the name of that part of London now known as Leicester Square, and the removal of their school from this central position to the village of Chelsea, at two miles distance, must have made a considerable difference in the lives of the young gentlewomen who had been confided to the care of Mr. Josias Priest. But preparations were just then being made for a great event, and the wily dominie doubtless knew what he was about when he chose the drear month of November for his flitting.

In the great schoolhouse which had been Mr. Portman's there was to be such a Christmas "break-up" as had never been known, and the young gentlewomen of Mr. Priest's establishment had no leisure to lament the gaieties of London life, for their thoughts were fully occupied by the practising of their music and their steps, not to mention such frivolous matters as the trying-on of fancy costumes and the twisting of bright English tresses into the coils which should surmount the dainty heads of maids and matrons of classic Carthage.

The new Chelsea school-master was nothing if not ambitious, and no less a thing would satisfy him than the performance of an original opera by the young gentlewomen of his establishment. To realise the full extent of this ambition one must remember that up to this time (1680) opera was unknown in England. The first opera ever written was Peri's Dafne, and this had been privately performed in Florence in 1597. The same composer's second opera, Eurydice, was the first work of the kind to receive public support, it being performed in 1600, also at Florence. Opera now slowly found its way across Europe, reaching Germany in 1627, when Heinrich Schutz's Dafne was given at Torgau; and arriving at Paris in 1659, in which year La Pastorale, by Robert Cambert, was sung before a public audience. From this time it made rapid strides in the French capital, and Lully's operatic compositions were regarded as masterpieces. England, however, still hung back, not because there was any lack of excellent musicians in the country, but because the sympathy and encouragement which are necessary to the advancement of any art were not forthcoming.

Under the stern rule of the Puritans, music had been rigorously suppressed, and the compositions of our older masters, existing only in precious manuscripts, had been torn up and trampled under foot. The destruction of singing-books was so complete that very few specimens of pre-Commonwealth music now exist, and to add to the general ruin, valuable organs were broken up, the one in Westminster Abbey itself being pulled to pieces and its pipes pawned at the ale-houses for pots of ale.

Although the work of destruction was being thus drastically carried out by Cromwell's soldiers, the Protector was not himself without a strong love for music, and one of the acts for which musicians owe him gratitude was his rescue of the organ in Magdalen College, Oxford. This beautiful instrument he had privately brought to Hampton Court and placed there in the great gallery, in order that he might listen to the music played on it by his secretary, the poet Milton. After Cromwell's death it was returned to Magdalen College, but eventually it was sold, and it now stands in Tewkesbury Abbey.

The year of Cromwell's death (1658) witnessed the birth of England's greatest composer. In a small back street of Westminster, St. Ann's Lane, Old Pye Street, there was living at this time a clever musician called Henry Purcell. At the Restoration he was made Gentleman of the Chapel Royal, and in this capacity he sang at the coronation of Charles II., when, in order to do honour to the occasion, he, in common with his colleagues, received "four yards of fine scarlet cloth to be made into a gown." He was also elected singing-man of Westminster Abbey, and Master of the Chorister Boys, as well as music-copyist. This last was deemed a very honourable position, and owing to the wholesale destruction of church music-books during the Commonwealth, it was no sinecure; for it must be remembered that in those days there were no cheap editions of printed music, and every composition had to be laboriously transcribed by hand, printed copies being very rare and expensive.

Little is known of the private life of Henry Purcell, senior, beyond the fact that his wife's name was Elizabeth, and that he was the father of the greater Henry Purcell, the child whose birth occurred in the very year in which his father's fortunes began to look up; and in which, by the accession of Charles II., there was given to music an impetus that was significantly foreshadowed by the advent of England's greatest musician.

Beneath the grey walls of Westminster Abbey little Henry passed the first years of his life, the sounds of music constantly in his ears and in his heart, and so well had his sweet baby voice been trained that, at the death of his father, when he was but six years old, he was admitted as a chorister of the Chapel Royal. His father's brother Thomas, also a gifted musician, henceforth took care of the boy and superintended his education with watchful tenderness. His teacher at this time was Captain Cooke, an old man, who had belonged to the chapel of Charles I., and who, on the breaking out of civil war, had turned soldier and fought on the Royalist side. He had won a captain's commission, and now, as a reward for his loyalty, he was appointed by Charles II. Master of the Children of the Royal Chapel. Many of the anthems composed by Purcell, and still in use in our cathedrals, date from this time, and he was only twelve years old when he wrote the ode which he called "The Address of the Children of the Chapel Royal to the King and their Master, Captain Cooke, on his Majesties Birthday, A.D. 1670, composed by Master Purcell, one of the Children of the said Chapel."

At sixteen our composer became a pupil of the famous Dr. John Blow, one of the greatest musicians of this time; and now his genius developed with marvellous rapidity.

Amongst the minor canons of Canterbury Cathedral, there was one John Gostling, the fortunate possessor of a bass voice of extraordinary compass. This man was a great favourite with Charles II., and on one occasion the King, having arranged a pleasure trip in his new yacht, The Fubbs, round the Kentish coast, desired Gostling to join the party "in order to keep up the mirth and good-humour of the company." The boat had not gone very far when a terrible storm arose, and the danger became so imminent that the King and the Duke of York had to work like common sailors to help keep the vessel afloat. They escaped, but the impression made on Gostling was so profound that on his return to London he selected those passages from the Psalms which declare the wonders and terrors of the deep, and gave them to his young friend Purcell to compose, the wonderful anthem "They that go down to the sea in ships" being the result.

It was with reference to this singer that Charles II. made the bon mot, "You may talk as much as you please of your nightingales, but I have a gosling who excels them all!"

In 1680 Dr. Blow resigned his position as organist of Westminster Abbey in favour of his young pupil, and thus at twenty-two years of age, we find Purcell in possession of the most important musical appointment in the kingdom. His fame was already secure, but this year was to put the crown on all his former achievements, and this crown was to be twined for him by English school-girls.

In this year Mr. Josias Priest moved his school for young gentlewomen to Chelsea. In this year also he conceived the bold idea of an English opera, and having chosen his subject, the classic history of Dido and Æneas, he had commissioned Nahum Tate, a native of Dublin, who was already known as co-author (with Nicholas Brady) of the metrical version of the Psalms, to prepare the book. The brilliant young organist of Westminster Abbey was engaged to compose the music, and so heartily did he throw himself into the work that an opera was produced which could measure itself against the best existing productions of Italy, France, or Germany.

That the music should have been so surpassingly beautiful is the more surprising when we remember the limitations imposed upon its creator. With the exception of the part of Æneas, which was given to a tenor, all the parts were written in the G, or treble, clef as being the easiest for young gentlewomen; and the orchestral accompaniments were confined to two violins, a viola, bass, and harpsichord.

The composer himself played the harpsichord parts on this first occasion, and the audience seems to have consisted, as is usual in such cases, of the parents and friends of the young performers. The entertainment was pronounced an unqualified success, and it would indeed have been a crabbed auditor who could have remained unmoved while Queen Dido confided the story of her love to her trusty Belinda, or listened to the protestations of the faithless Æneas. Bands of shepherds and shepherdesses, enchanters and sorceresses, varied the solo parts with choral song and dance, and towards the close came that incomparable death-song, the exquisite pathos and beauty of which still strike home to every listener. "Remember me," sings the forsaken and dying queen to her faithful Belinda, "but oh, forget my fate!"

Mr. Fuller Maitland says in connection with this song:—

"It is an inspiration that has never been surpassed for pathos and direct emotional appeal. It was this directness of expression rather than his erudition that raised Purcell to that supreme place among English composers which has never been disputed. The very quality of broad choral effect which has been most admired in Händel's work was that in which Purcell most clearly anticipated him. In actual melodic beauty Purcell's airs are at least on a level with Händel's."

At the close of the performance, the Lady Dorothy Burk, one of the young gentlewomen of Mr. Josias Priest's school, recited an epilogue, written for her by Thomas D'Urfey. It is too long to quote entire, but the following extracts from it may interest our girls of to-day.

Dido and Æneas was not printed until 1840, and even then it was but an imperfect version of the opera that was given to the world. Since 1895—the bi-centenary of the composer's death—the Purcell Society has been issuing a complete edition of the works of the "English Orpheus," and Dido and Æneas has now at last come into its right. During Purcell's lifetime opera was not held in high favour in this country, a fact which is significantly proved by the circumstance that Dido and Æneas had no successor. In the Gentleman's Journal for January, 1691-92, we find this quaint statement: "Experience hath taught us that our English genius will not rellish this perpetuall singing." Henceforward our first opera composer confined himself to incidental music introduced into spoken drama. A poor perversion of The Tempest, by Shadwell, was honoured far too highly by being set to music by him, and only those parts of the music which were associated with Shakespeare's words, such as, "Come unto these yellow sands," and "Full fathom five," have survived.

An adaptation of Beaumont and Fletcher's Dioclesian has fared no better, but it attained the honour of print during its composer's lifetime. It was dedicated to the Duke of Somerset, and was accompanied by an address to his Grace containing the following passage, which is of interest to us to-day, as showing the respective positions of the sister arts at the close of the 17th century.

"Music and Poetry have ever been acknowledged Sisters, which, walking hand in hand, support each other; As Poetry is the harmony of Words, so Musick is that of Notes; and, as Poetry is a Rise above Prose and Oratory, so is Musick the exaltation of Poetry. Both of them may excel apart, but sure they are most excellent when they are joyn'd, because nothing is then wanting to either of their Perfections: for thus they appear like Wit and Beauty in the same Person. Poetry and Painting have arriv'd to their perfection in our own Country. Musick is yet but in its Nonage, a forward Child which gives hope of what it may be hereafter in England when the Masters of it shall find more Encouragement. 'Tis now learning Italian, which is its best Master, and studying a little of the French Air, to give it somewhat more of Gayety and Fashion."

Dioclesian, backed by the Duke of Somerset, was successful. It was performed in 1690, and was said to have "gratify'd the expectation of Court and City, and got the author great reputation."

In the following year Purcell wrote the music to King Arthur, the work which, next to Dido and Æneas, holds the highest rank amongst his secular compositions. The drama had been written by Dryden, but the entire plot had to be so changed, owing to the altered political situation, that the poet, in his preface, after lamenting the destruction of his verse, goes on to say—

"There is nothing better than what I intended than the Musick; which has since arriv'd to a greater perfection in England than ever formerly; especially passing through the artful hands of Mr. Purcell, who has compos'd it with so great a genius, that he has nothing to fear but an ignorant, ill-judging audience."

The immediate success of King Arthur seems to have been great, though it did not long hold the stage. The time for works of this kind was not yet come; in 1770 it was revived at Drury Lane, with a considerable access of popularity. Since that time it has been heard at tolerably frequent intervals, and a masterly performance was given under the direction of Dr. Hans Richter at the Birmingham Festival in October, 1897.

Though Purcell's life only extended over thirty-seven years, he had the composition of odes, on various occasions, for no less than three English sovereigns. In addition to his numerous contributions in honour of Charles II., some of which have been noted here, he wrote for the coronation of James II. the two splendid anthems, "I was glad," and "My Heart is inditing." He also wrote for James an ode beginning, "Why are all the muses mute?" There seems to be something of irony in the fact that he should likewise have been the author of a melody which, according to contemporary writers, did more than anything else to "chase James II. from his three kingdoms," but though Purcell certainly wrote the music ultimately sung to Lilliburlero, it is no less true that he had no knowledge of the use to which his melody would be put. Amongst his minor compositions of this time were a march and a quickstep, and the Irish Viceroy, Lord Wharton, was discriminating enough to recognise that the tune of the latter, wedded to words by himself, in which the king and the Papists were held up to derision, would have an extraordinary effect upon the masses of the people. The event proved that he was right. According to Bishop Burnet, "the impression made on the army was one that cannot be imagined by one that saw it not. The whole army, and at last the people, both in city and country, were singing it perpetually, and perhaps never had so slight a thing so great an effect."

The tune is a bright, gay one, and is now put to a harmless use by being sung to the nursery rhyme—

It is also sung by young girls in the south and south-east of Ireland, while reaping in the fields, to the words—

and usually has reference to one of their number who is less nimble than her companions.

James having fled, it was next Purcell's duty to compose an ode in commemoration of the accession of William and Mary. This was performed at the Merchant Taylor's Hall, at a gathering of Yorkshiremen, for which reason it is now known as the "Yorkshire Feast Song."

He wrote odes to St. Cecilia, which were used at the festival of St. Cecilia's Day for several years, the finest of them being the last, the magnificent Te Deum and Jubilate, written in 1694. It was the first work of this kind that had ever been heard in England, and from the date of its composition till 1713 it was performed regularly every year. Then Händel's great Te Deum and Jubilate for the Peace of Utrecht was composed, and was performed alternately with the work of the English musician until 1734, when Händel's Dettingen Te Deum displaced both its predecessors.

In December, 1694, Queen Mary died, and Purcell composed the music for her funeral. There were two new anthems, "Blessed is the man that feareth the Lord," and "Thou knowest, Lord, the secrets of our hearts." We have the testimony of one who was present in the choir on this solemn occasion as to the effect produced by the noble music. "I appeal to all that were present," says this authority, "as well such as understood music, as those that did not, whether they ever heard anything so rapturously fine and solemn, and so heavenly in the operation, which drew tears from all, and yet a plain, natural composition, which shows the power of music, when 'tis rightly fitted and adapted to devotional purposes."

The second anthem, "Thou knowest, Lord," has been sung at every choral funeral in Westminster Abbey and St. Paul's from that day to this, for Dr. Croft, who set the Burial Service to music, abstained from setting these words, declaring that the music left by Purcell was unapproachable.

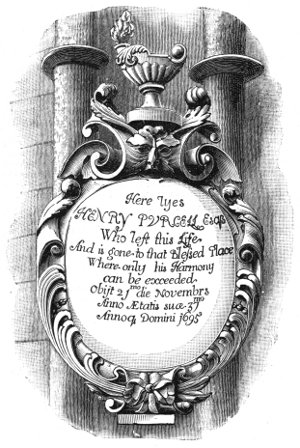

Only a few months after Queen Mary's death the composer also passed away to "that place where alone his harmony could be excelled," and the solemn strains of the anthem but lately written for the dead Queen were sung by his friends and colleagues as they laid the loved master to his rest beneath the shadow of that organ on which he had so often played.

Dr. Blow, who had stood aside to let the younger musician take his place, now resumed his appointment as organist of Westminster Abbey; and, facing the memorial tablet raised there to Henry Purcell, we may see one placed to the memory of Blow, recording, amongst other tributes to his mind and heart, that he was "the master of the famous Mr. Henry Purcell."

A collection of "Choice Pieces for the Harpsichord," by Purcell, was published by his widow after his death, as well as two books of songs called Orpheus Britannicus. Prefixed to the second of these volumes is an ode from which, in conclusion, I give a short extract.

By "MEDICUS" (Dr. GORDON STABLES, M.D., R.N.).

The sunsets at Nairn, N.B., are often beautiful in the extreme. Last night, however, was probably an exception, for the sun gave just one yellow uncertain glare across the wind-chafed waves, then sank behind a bank of sulphureous-looking clouds. Darkness came on a whole hour before its time, and though an almost full moon was in the sky, the rolling cumulus eclipsed it. And such awful cumulus I have never seen before; so black, so beast-like in shape. To gaze up into the heavens was like catching a glimpse of some scenes in Dante's Inferno.

Then high and higher rose the wind, howling and "howthering" from off the stormy Nor' lan' sea. Although my caravan is well anchored down in the wide green meadow in which I lie, she pulled and dragged at her hawsers, and swung and rolled like a ship in the chops of the Channel. But a wild wind and a van that rocks, bring sweetest slumbers to the brain of the poor wandering gipsy, and it was well-nigh six this morning before I opened my lazy eyes.

The sea out yonder is an ocean of blue ink flecked with snow-white foam; for the storm still blows, though less fiercely. Beyond the Moray Frith sunshine and shadow are playing at hide-and-seek, and so bright are the colours of woodland and fields, their deep dark greens, their yellows and the touches of crimson on the beetling cliffs, that they bring vividly to my recollection the awful pictures I used to paint when a boy of eight or nine.

It is already well on in the fa' o' the year, and I am still 700 miles from my English home. But there is a sting in the air now, both morn and even, which sharply touches up one's kilted knees. Wonderfully bracing, however; there is health in every breeze, and I believe my girl-readers, who happen to possess anything having the slightest resemblance to a constitution, should go out for exercise in all weathers.

And now let me give a few hints in paragraphs, which I feel certain will appeal to many of my readers.

By this I mean those which are not congenital, such as club-foot, for instance; deformities, in fact, that girls bring on themselves. I will go down as low as the feet first. Well, it is, of course, greatly to be deplored that Providence did not give you feet to fit your shoes; but really, to compress the feet means perpetual discomfort and danger. Cases of headaches and extreme nervousness may often be traced to the wearing of tightly-fitting boots or shoes. Pimples or acne, red nose, dyspepsia and varicose veins may also be produced through the same cause. Nearly all deformities of the feet can now be removed by surgical appliances. Flat foot, or want of arch, is one of these. It is not only remediable, but it should be remedied.

The toes ought to have play in a shoe, else girls can never walk, or dance, or play tennis, or golf gracefully. God never meant your foot to be all one solid lump squeezed into a shoe three sizes too small for you, or depend upon it He never would have given you toes.

Corns will not form—whether hard or soft—on the foot that wears a nice smooth stocking and an easy-fitting boot. The nails should be attended to every morning or evening after the bath, and ought to be cut square off, and not down the sides, else the consequence may be an in-growing nail and painful ulceration.

Never sit long with your legs crossed one over the other. It interferes greatly with the circulation, and may cause varicose veins.

Bent spine.—This is preventible in many ways. When writing, reading or typing do not lean forward; sit erect, and keep even the neck straight. Throw the shoulders well back, and thus will you expand chest and lungs. The same rule holds good if cycling. All kinds of exercises should be taken that tend to develop the muscles of the chest and give plenty of room for heart and lungs. Tight-lacing causes shocking and dangerous deformity, displacing all the internal organs and interfering with their work, so that your tight-laced girls are at best but hanging to life by the eyelashes, and the man who marries such a one is no better than a fool.

Blood purifiers sold in shops are one of the swindles of the age, and the time is not far distant, I hope, when quackery will be banished entirely from the British Isles. Meanwhile beware of everything you see on a chemist's counter that bears a government three-halfpenny stamp.

You cannot be happy, it is true, if the blood be impure, and moreover, while it is so you are far more liable to catch colds and coughs and any ailment that may be epidemic, such as influenza.

1. Never eat to repletion. If you eat slowly you will not do so.

2. Avoid too much sugar and pastry, especially if you have a slight leaning towards embonpoint. The lean may use sugar, but not the round-faced and obese.

3. Good ripe fruit before breakfast.

4. The morning bath to keep the skin pores open, and thus reduce the work of the internal excreting organs.

5. A large tumblerful of hot water with a squeeze of lemon in it, after the bath.

6. No tea in the morning, but coffee, cocoa, or hot milk.

7. Eat slowly, masticate well. Never get into an exciting argument at table.

8. Be regular in all your habits, and sleep with your windows open.

Thus shalt thy blood be pure.

Now that the nights are getting long, and we have to read by lamp-light, by electric, or gas-light, a word about the eyes may be opportune. Don't therefore try or tire your eyes too much. Read in a good light. Remember that tiring the eyes means tiring the brain, for the nerves of sight issue therefrom. Students should frequently bathe brow and eyes in the coldest of water, and rest awhile on the sofa with a newspaper over the face.

Eyes and health go hand in hand, and if your liver or stomach be out of order, the eyesight will become more or less dim for a time. It is most important therefore that girls engaged in study, or who do office work, should make a point of keeping their health well up to the mark.

Cycling is revolutionising the kingdom, partly for good, partly, alas! for harm. But I want to warn parents against permitting children of too tender years to cycle. Remember I myself might be called a cyclomaniac. Many is the article and many the book I have written on this charming method of pedal progression, but I never have been a scorcher.

I say, and fear no contradiction, that no girl should be permitted to mount a bike, until she is eleven or twelve years of age, and even then she must ride in moderation. Else years and years of ill-health and trouble are in store for her in after-life. Children should be taken good care of when out cycling, and those with them should ride in moderation, else the child will kill herself in trying to keep up.

The same may be said about club-cycling for young men. Just as there is always a tiny wee "drochy" in a litter of pigs, so in a club out for a spin there is always one or more poor white-faced visions of lads that a Chinaman could whip, and it is pitiful to gaze on their weazened white bits of perspiring faces as they bend over their bars and try to keep up. Such brats often smoke too. Alas! alas! but there is one consolation, they soon sink into their morsels of graves, and the world wags better without them.

This is usually called "Anæmia." The words of a fellow-practitioner in a recently published medical journal are so good that I make no apology for transcribing them for your benefit.

"It is doubtful, in my mind, whether the average doctor realises the frequency of anæmia. I am sure that if the general practitioner gave due attention to the factor anæmia, we should have comparatively few cases of disease extending into the chronic stage. Too few physicians are accustomed to take into account all the elements of every case, including this, the most prevalent and essential of all. Any disease that depletes the system and draws largely on the vital forces will involve the condition we call anæmia. On all such occasions, it is of the first importance for the doctor to be constantly on the look-out for this condition. The best means of diagnosis is microscopic examination of the blood, to determine its quality from the number of red corpuscles and the proportion of hæmaglobin, and also as to its freedom from bacteria.

"As to the treatment of anæmia, blood, in my opinion, is undoubtedly the only agent that can absolutely restore the normal condition of blood. Iron has long been the favourite remedy with the profession for the treatment of anæmia. But a careful study of clinical cases, and careful perusal of the opinions of the most intelligent medical men, will elicit the fact that this remedy will not all the time produce the most satisfactory results. In fact, the majority of physicians will tell you that iron will act favourably up to a certain point only. Why is this? It is because iron preparations are not readily absorbed, and because they can only stimulate cell proliferation, but cannot help the deficient nutrition of the proliferating cells. It is for this reason that, as much clinical experience has proved to me and many others, patients put on iron and other so-called blood tonics seldom make any permanent improvement. The agent that brings results clinically is one that not only causes rapid cell proliferation, but supplies the new-born cells with direct nutrition, thereby causing them to proliferate in turn; thus finally restoring the blood to the normal standard."

Well, au revoir, girls, till we meet in bleak December. And just let me thank the G. O. P. lasses who visited my caravan this year in Scotland, and brought me smiles and pretty flowers.

By "A. N."

By SOMERVILLE GIBNEY.

Sixteen years had sped by, leaving their footprints behind them. Sir Ralph Travers was no more, and his son Hugh reigned in his stead at Combe. Lady Travers still lived, and with her, almost as a daughter, the little Cecily we last saw beneath the copper-beech tree, but now grown into a graceful young woman of one-and-twenty. The kindness of the aunt had brought its reward in the devotion of the niece, whose loving care and attention was the more appreciated now that the mainstay of the house was often away at his duties. Hugh was an officer in the army, and, like his father before him, had sided with his king, and more recently with that unfortunate monarch's son. But at this moment the affairs of royalty were not prospering. The fatal fight at Worcester had taken place the previous day, and already rumours had reached Combe as to the result. A packman had arrived at the village, and had told how, on his journey that morning, he had seen parties of Cromwell's Ironsides searching the country for remnants of the royal troops. The news had quickly been carried to the Abbey, increasing the already terrible anxiety of the two ladies. They were well aware that Hugh was in the battle, for he had sent them word, by one of his troopers, only a few days previously as to his whereabouts. But what was his fate? Was he a prisoner? Was he a fugitive? Was he killed? Lady Travers, as she sat alone in her chamber asking herself these questions, felt that definite news, even if it were the worst, would be better than the fearful uncertainty that was crushing her. Cecily had been with her, doing her best to appear cheerful and minimise the perils of the situation, though the part she played was that of a would-be deceiver as far as her own convictions went. She knew Hugh would be no lag-behind where danger threatened. He was not one to hang back when his right arm was needed, and she felt that if he had escaped a soldier's fate it was only through the intervention of Providence, and not from any regard for his own safety. She had striven to put a bold face on the matter, but the terrible anxieties of the mother had communicated themselves to her, and as dusk was falling on that September evening she found it impossible to remain longer without breaking down, and on some trivial plea had quitted the room. Passing down the broad oaken staircase she crossed the hall, and wrapping herself in her cloak, which she had that morning left on one of the chairs, she drew the hood over her head and went out into the garden. She felt she could breathe more freely there, and relax the strain on her countenance, since there was none to watch her. But her anxiety was not relieved by one tittle; the crushing weight pressed no less heavily on her here beneath the shy stars that were just beginning to peep than in her lady aunt's chamber. Her heart and her thoughts were with her soldier cousin, and once and again she paused in her walk to listen, as she fancied she caught the sound of galloping hoofs and the clatter of steel in the village below. But all seemed at peace. The wind had sunk with the sun, and hardly a leaf stirred. The sounds that met her ears were only the uncouth voices of the herdsmen and labourers discussing the news of the day in front of the tavern door. Her steps had led her some short distance from the Abbey among the clumps of evergreens that formed a screen on its eastern front. It was darker there, and the loneliness and gloom suited her state of mind. She wandered on with bent head, lost in thought, until the cracking of a dry twig{106} recalled her to herself. She looked up, and fancied she could see the boughs of a laurel on her right move. The next moment she heard her own name whispered—

"Cecily!"

She started back frightened, and would have turned and fled, but the next words reassured her.

"'Tis I—Hugh—make no sound!"

"Hugh? And you are in danger! I know it—we have heard all"; and the girl stepped forward and thrust her hand among the branches, when it was seized and held.

"Yes, they are after me—hunting me down as though I were some red deer. They will soon be here. It was my last chance or I would not have come, bringing peril to my mother and you."

"No, no; 'tis your home. It was right you should come; we may help you—you must hide; but where? I know of no spot in the house which would not be instantly discovered."

"The house will not do. I must not be seen by a soul but you. No one must know I am near the place. Hark!"—and far away in the distance could be heard the clatter of galloping horses and the rattle of steel.

"Oh, Hugh, they are coming! What can we do—what can we do?"

For answer the young man pushed his way through the branches, and, standing beside his cousin, said:

"What is this you are wearing, child?"

"My cloak."

"The very thing! Give it to me"; and as he took it off her shoulders, "Now go and see that there is no one in front of the house. It will be in shadow at present, till the moon is higher, and, thank God, there will not be much of that this night, for she is yet but young; if none be about, then raise your kerchief to your face and continue your walk."

"And you?" asked Cecily, as she turned back down the path.

"Wait and see. Hurry, for I hear the horses rising the hill."

Cecily made her way along the front of the Abbey, and then, turning, retraced her steps with her handkerchief held to her face. She did her best to assume the manner of a person taking a careless evening stroll, but at the same time her eyes were on the alert, and she could just discern the figure of her cousin creeping along close to the wall of the Abbey, until her steps carried her beyond, and she dare not turn her head for fear the simple movement might be seen by someone and attract attention. In a few minutes she had reached the evergreens again, and here she once more turned, and again passed in front of the Abbey; but, though she scanned the building as well as she was able through the gloom, she could see no sign of Hugh.

Puzzled, and yet thankful was she. What had become of him? There was no door near through which he could have entered the house, and the cessation of the slight scrunching of the gravel beneath his feet had told her that he had not proceeded further. But she had small space for conjecture, for there were galloping steads on the drive leading to the house, and the next moment she found herself surrounded by a number of the dreaded Ironsides.

"Trooper Flee-the-Devil, detain that maiden, and bring her within the house; she may possess the information we desire. Sergeant Piety, follow me with six men. The rest under Lieutenant Champneys surround the dwelling, keep strict guard, let none go out or come in, and search the bushes and thickets."

"What is the meaning of this, sir?" inquired Cecily, assuming an indignant and surprised air, in answer to the commands given by the leader of the party.

"I wot ye know full well already, maiden; but if it be otherwise, ye shortly shall know. Trooper Flee-the-Devil, lead on. The rest to your duties."

Surrounded by the Ironsides, Cecily was led back into the house, and here the leader took up his position in front of the huge fireplace and kicked the logs on the hearth into a blaze, as he indicated the spot where his prisoner was to stand. After warming his hands a moment or two in silence, he turned about and said:

"One of you remain here with the maid and me; the rest search the house, and mind ye find him, for he is here. We have certain knowledge of the fact. Leave no hole or corner unvisited, but bring him before me alive or dead. Meanwhile I will try what gentle means may do in this direction"—nodding towards the girl.

The troopers separated, some making their way to the kitchen and chambers on the ground floor, while others mounted the stairs to the upper rooms and attics.

Cecily felt strangely calm and collected in face of the peril. In after times when she came to think it all over she wondered at herself, but she recalled the fact that at the moment she was well-nigh certain her cousin was not on the premises, or, at any rate, inside the Abbey, and she had felt that if there were a safe hiding-place to be found his intimate knowledge of his own home would stand him in good stead in the emergency.

"Well, maiden, where is this traitor? You had best speak at once, and save time and trouble, for I doubt not you are well informed of his movements."

"We have no traitors among the dwellers at Combe Abbey, sir, and if there be any here now they are no welcome guests, I promise you," replied the girl calmly, looking the officer straight in the face.

"I would have you keep a civil tongue in your head, as becomes a modest maid," replied her interrogator. "Tell me at once, where is this pestilent rogue, Hugh Travers?"

"I know of no 'pestilent rogue' of that name, though that same name is the property of my cousin and the owner of this house."

"And he is here at this moment."

"Is he? Then why detain and question me, since you are so well informed? Permit me to leave you; I must attend on my aunt, who is but poorly, and who will be disturbed by this unwonted turmoil, for Combe Abbey is a peace-loving house." And Cecily made as though she would cross the hall and mount the stairs; but the trooper beside her laid his hand on her arm and detained her as the officer continued:

"Stay where you are, wench; this giddy talking will avail you nothing."

"Sir, methinks those that preach would do well to set an example," said Cecily, with a slight curl of disdain on her lip.

"Ah, in what way mean you?"

"Those that prate of civil tongues should be possessed of the same."

"Heyday! A plague on you for a saucy slut!"

"After that I listen to no more of your instructions, sir. I will not have you as my master"; and Cecily curtseyed in mock deference to the officer, who, losing his temper, said loudly—

"A truce to this folly! Where is Hugh Travers?"

"I know not."

"But he is here."

"So you tell me."

"You have seen him."

"So you say."

"I will have him!"

"That is as may be. Can I tell you ought else?"

"I can tell you that it will be the worse for all here if he be not given up at once. The Lord Protector has his eye upon this house."

"Then I wonder he has not seen the owner, since you say he is here."

"Faugh! 'Tis folly to bandy words with a woman! Ah, here is something!"—as a trooper was seen coming down the stairs leading Lady Travers.

At the sight Cecily broke away from her captor, and, running to meet her aunt, offered her arm as a support.

"What is the meaning of all this, Cecily?" asked the old lady.

"It means, aunt, that this gallant gentleman has brought us news of Cousin Hugh, since he asserts that he is here."

"Hugh—here? Where? Why was I not informed?"

"Nay, madam, this young lady is too ready with her tongue, and by verbal quips has been endeavouring to deny the fact of her cousin's presence here."

"Then she did but speak the truth, sir. I have not seen my son for this many a long day. Would God I had! But that he was with the army at Worcester we know full well, since he sent us word of the fact but a few days since."

"You hear, sir?"

"Yes, I hear. But seeing is believing, and I will——"

"As you will, sir. The word of a lady counts nought with a soldier nowadays, it seems."

The officer gave a glance at the young girl as if about to frame a retort, but it may be the presence of Lady Travers deterred him, for with a shrug of the shoulders he turned to the troopers and bade one of them follow him upstairs, while the other remained as a guard over the ladies. This latter man—the one who had brought Lady Travers from her room—appeared to possess some shade of good feeling, for as soon as his officer had disappeared he withdrew to the other side of the hall, leaving the ladies practically alone in front of the fire, where they could converse undisturbed.

Cecily, deeming it the wiser plan to appear as unconcerned as possible, informed her aunt, in a tone that could easily reach the sentry's ears, how her evening stroll had been so rudely interrupted by the soldiers, and how she had been made a prisoner and detained in the hall while the house was being searched. Lady Travers, being totally unconscious of the near presence of her son, had nothing to conceal, and therefore, all unknowingly by what she said, ably seconded Cecily's efforts. It was in this way the ladies conversed for some time, until the captain descended the stairs after what, from his manner, had evidently been an unsuccessful search, when Lady Travers plied him with questions as to her son's fate. These he answered grudgingly, as though doubting their genuineness.

Meanwhile the servants had been driven into the hall like a frightened flock of sheep, and were each interrogated in turn; but their answers threw no light on the subject, and the officer's expression at the conclusion of the examination was more puzzled than at the commencement. He sent for Lieutenant Champneys, and on his arrival he could report no better success than had attended his captain. Not a soul had been seen outside the building, save the grooms in the stable-yard; the gardens, the park and the plantations had been searched without a trace being found. There were no suspicious circumstances; no one seemed to wish to conceal anything; no obstacles had been placed in the way, and yet, from certain information possessed by the officer, he knew that Hugh Travers, if he had not actually been in the house or grounds, had been very close to them. He was baffled. He had anticipated an easy{107} capture, but instead of that the chances of one seemed to be receding each moment. Hugh Travers was not the only fugitive on whose head was set a price; there were others suspected of being in the neighbourhood, and it would be folly to sacrifice all for the sake of this one somewhat vague chance. Still he was piqued by Cecily's taunts, and loth to own himself defeated. At any rate, he would make one more effort. He himself would go round the outside of the Abbey, and Cecily should accompany him. The moon had risen by this time, and there was more light than when he had arrived. He might possibly to able to discover something, or the girl might betray herself in some way, though he was by no means so certain now as he had felt at first that she had anything to betray.

Cecily offered no objection to his request for her company, and, having sent one of the maids for a wrap, they set out together. At first little was said by either of them, but then it occurred to the girl that the sound of her voice might act as a warning of danger to her cousin, if he were hiding anywhere near at hand, and she commenced to talk loudly and rapidly about anything that came into her mind.

They were passing the front of the Abbey, and, as the faint moonlight fell upon the grey stone face, making the shadows that lingered in the corners still more deep, Cecily was pointing out the windows of the various rooms, and the Travers coat-of-arms carved above the doorway. "And higher up," she continued, "are two niches, in the one stands the figure of Abbot Swincow, the founder of the house, for, as its name must have informed you, sir, it was formerly a religious house, and I trust it is worthy of the designation now, though in a slightly different sense; and in the other—— Oh!"—and Cecily swayed, and almost fell, but the next moment caught the arm of her companion and steadied herself.

"Ah, what is it?" exclaimed the officer, looking round suspiciously.

"Forgive me," said Cecily, looking on the ground as if seeking something. "It was very sharp at the moment. A newly broken flint, I suppose. May I take your hand for a minute? It is hard to see where one puts one's foot in this light."

"Certainly, madam," said the officer, rather pleased than otherwise; for, though a Puritan, he had an eye for a pretty face, more especially when no one was by to see him. "I trust you feel better already?"

"I thank you, sir—yes."

"You were saying——"

"Ah, yes—about the niches. In one was placed the figure of Abbot Swincow, and in the other that of a Father Anthony, who was supposed to have aided him in the building and institution of the house. But they have suffered much through time and weather, and now bear but small resemblance to the originals, I trow."

"As a true servant of the Lord Protector it is my duty to destroy such images, as contrary to the tables of the law, and being the work of men's hands, but other business is to the fore at the moment, and the capture of rebels is a more meritorious employment than knocking off the heads of statues."

"Doubtless, sir, and surely they will wait your time, seeing it is some hundreds of years since they took up their position."

"Cease jesting, maiden. Quips and cranks are not seemly in a woman, nor in a man either, seeing the days are evil. You and I have got on better since you have bridled your tongue."

"As you will, sir; and now, if it be your pleasure, I will lead you to the gardens and stables."

"Ah, trooper! Any news?"—as a figure approached them from out the gloom.

"None, captain—not a living soul—not so much as a rabbit has crossed my path."

"Is it so? Keep your loins girt and your ears and eyes open, and we may yet prevail. Lead on, maiden."

Round the gardens, through the stables, up into the loft and store chambers went the captain and Cecily, the latter talking all the time, but in a lower tone and far more naturally than before the stumble on the gravel in front of the Abbey.

At length the round was completed, and as the officer again entered the hall with Cecily, he said—

"Well, all has been done that can be done. The man I want is not here. He must have passed on, deeming it too dangerous a spot wherein to rest. But I'll have him yet."

"That is as may be, sir. Still, in any case, I trust that you will not deem either my aunt or myself wanting in courtesy in affording you all the help in our poor power in your search."

"Nay, maiden. If I judge rightly, you have done all you can to aid the ruler of this realm. You have done your duty."

"I have," thought Cecily, though she merely bowed modestly and kept silence.

"Trooper Piety, bid the lieutenant get the men together; we must away."

"Not before you have supped with us, sir?" said the courteous Lady Travers. "Combe Abbey never turned away a hungry man, were he friend or enemy."

"I thank you, madam—not to-night. There is work to be done, and the soldiers of the Lord think less of their stomachs than their duty." And going to the door, the officer watched the mounting of his men.

It was then that Cecily found the opportunity to whisper to one of the serving-men.

"Count how many there be, Roger, and then away to the village through the orchard and see if the numbers be the same there, and that they have left none behind to spy. Bring me word as soon as may be."

A few minutes later, and with a farewell salute, the officer led his men down the avenue, and peace once more reigned at Combe Abbey.

It was after supper, and when Lady Travers had retired, that Roger returned.

"The number was the same, mistress, and I followed them a good two miles or more, and none fell out."

"That is well, Roger; then we may have peace again for a time. And now to bed, for we are all upset by this night intrusion."

But there was little sleep for Cecily. When all was quiet she stole down to the larder, and made up a packet of food, and with this, and a roll of twine in her hand, she quietly made her way on to the leads. "Father Anthony must be starving," she said to herself, as she fastened her parcel on to the string, and then cautiously looked out over the parapet. The whole world seemed asleep in the waning moonlight. There was not a sound to be heard; the lights in the village below were all extinguished; it was as though she stood on some eminence, gazing over an uninhabited land. Yet even thus the girl felt there was need of care, and it was scarcely above a whisper that she breathed the words, "Father Anthony!" as she leant forward, and looked into the dark shadow below.

"A blessing rest on your head whoever you may be!" were the words that came upwards in reply, almost like an echo.

"It is I—Cecily. And I have somewhat for your sustenance, father, since vigils such as yours cannot be maintained without support."

"And 'twill be right welcome, for I am famished and cold and cramped to boot."

The parcel was lowered, and again for a time there was silence, until at length came the direction—

"Draw up the cord, Cecily; I have finished, and now must away. The place is clear of the bloodhounds?"

"Yes. They are all gone onward; Roger watched them half-way to Meerdale."

"Then I will double back on their tracks, and may yet get off with a whole skin. Think you Roger could bring a suit of peasant's clothes to the hut in Varr Wood to-morrow evening?"

"Of a surety, yes."

"Then bid him place it in the rafters above the door and return at once. He will not see me."

"It shall be done."

"My mother—does she know I am here?"

"No one knows but me."

"Then tell her not of my coming. I hope to reach France, and if so will send you word. Till then tell her nothing. And now go; you must be nigh spent with what has taken place to-night. But 'twas bravely done, and has saved my neck. I heard every word as you led that bear on his wild-goose chase. And you uttered no wiser one than the 'Oh!' as you feigned to tread on something sharp and hurt your foot. But away with you. We will talk of all this in happier days to come, please God. I would I could kiss you once. But it may not be. Keep a brave heart, little girl, and Father Anthony shall enjoy his own again in good time."

"Farewell, Father Anthony, and the saints have you in their keeping!"

And again there was silence over Combe Abbey, save for a rustling in the ivy.

More years have passed, and merry England is itself once more. Laughter and mirth have ascended the throne side by side with the restored king. And nowhere in all the land is there more happiness than at Combe Abbey in the "West Countree." The lord of the soil is home again, and the villagers are busy with evergreens and wreaths, since on the morrow he takes to wife his cousin, Cecily Wharton. And as the happy couple, seated side by side with Lady Travers beneath the copper-beach, gaze on the old grey Abbey and the empty niche, their thoughts revert to the night when it afforded shelter to the second Father Anthony.

[THE END.]

ENGLISH PORCELAIN.

The introduction of porcelain manufacture into the earthenware factory of Swansea was due to Messrs. Hains & Co. towards the close of the last century; but it was of an inferior kind. In 1802 Mr. Dillwyn purchased the works, and in 1814 they had arrived at great perfection under the management of Billingsley. The former retired in 1813 and was succeeded by his son. The next year the porcelain manufacture was revived and carried on for about seven years very successfully; Baxter, an accomplished figure painter, having entered the service of Mr. Dillwyn, junior, and continuing with him for three years, but returning to the Worcester works in 1819.

Dillwyn's china seems to have been, as a rule, distinguished by the impressed or stencilled name (in red) "Swansea," also the tridents, as illustrated.

The factory was closed about the year 1820, John Rose of Coalport having purchased the plant and removed it to his own works.

Sometimes the name "Swansea" is stencilled in red and sometimes impressed only. A very scarce mark is "Dillwyn & Co."; also the two words stamped in capitals are enclosed in lines all round.

Derbyshire porcelain represents four different periods, the manufactory having been founded by William Duesbury, of Longton, Staffordshire, in 1781. It was formed from the Bow and Chelsea china, the founder having purchased part of the plant of the former factory and the whole of the works of the latter, carrying on the Chelsea and Derby works simultaneously. His son succeeded him in 1788, taking Michael Kean into partnership; who ultimately disposed of the works to Robert Bloor (in 1815), at whose death they were closed. But a small factory was opened by Locker, Bloor's manager, which afterwards passed into the management of Messrs. Stevenson, Sharp, & Co., and then Stevenson & Hancock. In the hands of Robert Bloor the manufacture declined in excellence.

The earliest mark is a "D" or the name "Derby" incised or painted in red. On the union of the works with those of Chelsea and Bow there was an indication of the combination as seen in the second and third illustrations given (a "D" crossed horizontally by an anchor), and the crown was added above the anchor after the Royal visit in 1737, the mark being, as a general rule, painted in blue. The crown, crossed batons, dots, and letter "D" were painted diversely, sometimes in gold, blue, or puce, and subsequently in vermilion. Later on three Chinese marks were employed, known as "the potter's stool," the Sèvres mark (a "D" in the centre and crown above), and the crossed swords of the Meissen factory. The batons in early use are now transformed into the swords by the present manufacturers, Stevenson & Hancock, and they have added their own initials; the whole device (crown, swords, dots, and initials) surmounting the letter "D," as will be seen in the last illustration.

It was in the third epoch of the manufacture of what is distinguished as the "Crown Derby," that porcelain works were established in the same county by John Coke at Pinxton (near Alfreton), 1793-5. Fine transparent, soft paste was used there; but the factory was closed in 1812. The patterns distinguishing this ware was a small sprig copied from the Angouleme porcelain—such as a blue forget-me-not, or cornflower, and a gold sprig. At Church-Gresley and at Winksworth (in the same country) there were other factories connected with the name of Gill, but undistinguished by any special marks.

The counterfeit mark employed at times on the Worcester china was likewise used on genuine Derby work, a sign borrowed from the Meissen factory to which reference has been made. The Duke of Cumberland, Sir F. Fawkner, and Nicholas Sprimont (a Frenchman) were amongst the first proprietors, and were succeeded by the latter (Sprimont).

As I observed, the Derby china manufacture passed through four periods or states of artistic development, the Duesbury being the first and best (1749), and then the younger Duesbury and Kean. Under the Bloor direction—lasting from 1815 to 1849—for some reason or other the artistic excellence declined.

Bloor's agent, Locker & Co., Stevenson, Sharp & Co., and Courtsay marked their work with their own names. The proprietors at the present time are Messrs. Stevenson & Hancock, and they have ceased to use the old mark as regards the batons, and now employ hilted swords, and have added their initials ("S" and "H") one on either side, as will be seen in the illustration. It may be well to observe that a six-pointed star, stamped in the centre, at the bottom of any article may be accepted as a Crown Derby mark. The porcelain produced by Mr. Duesbury resembled the Venetian in the Cozzi period.

It would be impossible to enter into a detailed account of all the various marks that distinguish the Derby china; but I may observe, as regards the last given (in a square form), that it appears on a plate of Oriental pattern, the crown and letter "D" painted in red. The square is not always surmounted by the crown. The capital "D" in italic lettering surmounting the written name "Derby" is the early mark used before 1769, and is found on very old china. The "N" is an incised mark and is probably an indication{109} that the porcelain was produced in the old works in Nottingham Road; and when in 1769 the Chelsea works were united to those of Derby, the union was indicated by the anchor of Chelsea crossing an italic capital of the letter "D." Derby figures are generally very roughly marked with three round blotches underneath them and the number scratched on the clay.

To Mr. Richard Chaffers—contemporary of Josiah Wedgwood—we owe the introduction of porcelain ware into the pottery factory in Liverpool in 1769. Of him, the latter said, "Mr. Chaffers beats us in all his colours." After ten years' work, having caught a fever from his manager Podmore, he died.

Philip Christian became the leading potter after that, and he produced large china vases equal to Oriental work and of great perfection. His china is marked "Christian" in capital letters.

John Pennington was specially celebrated for beautiful punch-bowls and for a very fine blue, for the recipe for making which he refused 1,000 guineas from a Staffordshire house. His business began in 1760 and lasted for thirty years. His mark was "P" "p" or his name in capital letters. He had been apprenticed to Josiah Wedgwood, thence he went to Worcester as foreman and chief artist to Flight & Barr, before he conducted the works at Liverpool.

Pennington carried on the china manufacture in Liverpool from 1760 to 1790. And, prior to him, I may name the factory of W. Reid & Co., of Castle Street, Liverpool, whose principal manufactures were in all descriptions of blue and white said to have been as good as any produced elsewhere in England.

Chaffers was drawing soap-rock from Mullion (Cornwall) in 1756 in preparation for the manufacture, even before Cookworthy of Plymouth had produced his hard-paste porcelain.

Besides the Penningtons and Philip Christian, Barnes, Abbey, Mort, Case and Simpson are all names celebrated in the Liverpool factory and in the neighbourhood.

The Lowestoft manufactory in Suffolk was founded by Hewlin Luson, Esq., in 1756 and erected on his own estate in the first instance at Gunton Hall.

In 1775 the Lowestoft porcelain had attained great perfection. Hard paste was then introduced, after a period of twenty years of the use of the soft, which was of fine quality. The hard was of very thick substance, but with a fine glaze.

So close was the resemblance acquired to Oriental porcelain at this factory that it was difficult for the general observer to distinguish between them, which difficulty was enhanced by the fact that no mark was ever used as it was an object with the proprietors to make their work pass for genuine Oriental ware. Yet there were certain peculiarities in style and colouring which were sufficient to betray their origin. Amongst these the prevalence of the rose in the declaration of a very large proportion of the china often served to identify it, being painted by Thomas Rose. The flower was generally pink and represented as having fallen from the stem. The most difficult of recognition amongst the varieties of Lowestoft china are the examples in white and blue.

Amongst other designs, the "fan and feather" pattern was striking in character in imitation of the Capo di Monte; painted in blue, purple, and red, and often in diaper work in gold and colours. Here also a very fine egg-shell china was produced bearing delicately-painted ciphers, coats of arms, crests and scrolls, and designs in pink camaieu, with highly-finished gold borders, pearled with colours; also dessert services with raised mayflowers on blue and white grounds and pierced sides; transfer-painting being also in use.

As every description of device taken from nature, including Oriental figures and other designs, was produced at this factory, it is impossible to describe them all. I may here observe that a china teapot of the distinctive "owl service" pattern was recently sold for upwards of £50.

The revival of the works after the opposition raised to them in Luson's time by the London manufacturers was due to Messrs. Walker, Browne, senior and junior, Aldred, and Richman, and Allen, who carried on a large trade with Holland.

The ultimate closure of the works was due to a disastrous combination of circumstances, which took place about 1803-4. There was a decline in the art some few years previously. It became too showy and over-gilded.