Title: Too Fat to Fight

Author: Rex Beach

Illustrator: Thornton D. Skidmore

Release date: December 21, 2015 [eBook #50735]

Most recently updated: October 22, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Shaun Pinder and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

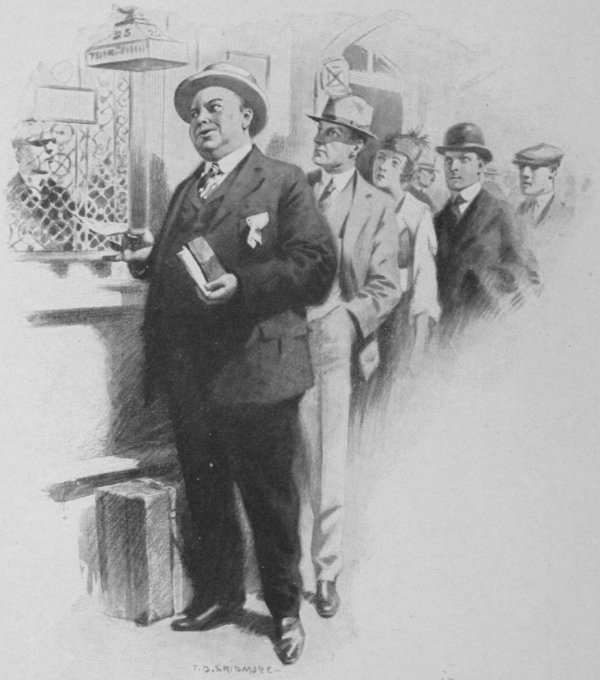

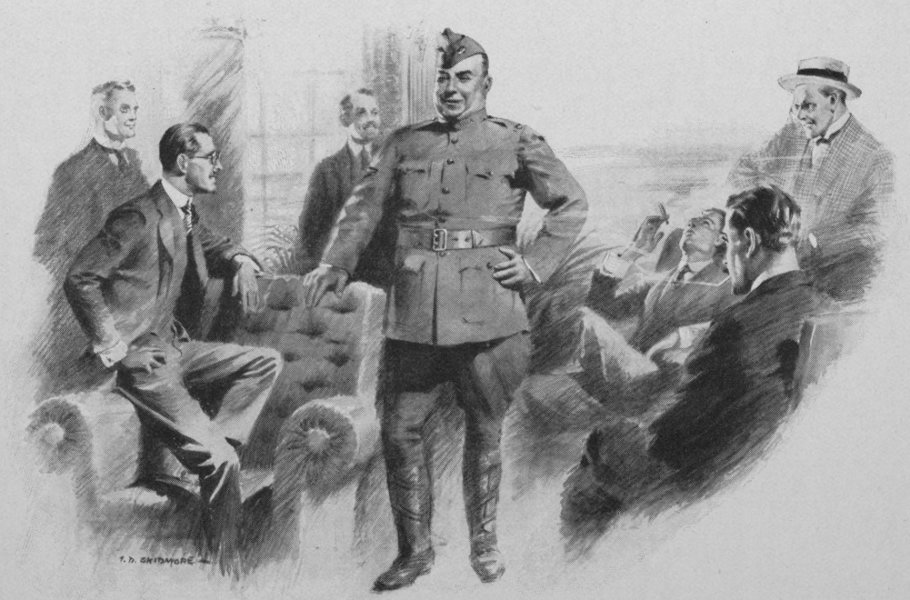

“PLATTSBURG. ONE WAY”

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | “Plattsburg. One Way” | 11 |

| II. | Dimples Tries the Y. M. C. A. | 22 |

| III. | “One Man to Every Ten!” | 39 |

| IV. | Hill Two Eighty-five | 43 |

| V. | Dimples Takes Part in a Ceremony | 47 |

| “Plattsburg. One Way” | Frontispiece |

| Occasionally He Ordered His Favorite Dish, Corn-starch Pudding | Facing p. 24 |

| He Had Gained a Pound! | “ 28 |

| A Rotund, Mirth-provoking Spectacle in His Bulging Uniform, with His Tiny Overseas Cap Set Above His Round, Red Face Like the Calyx of a Huge Ripe Berry | “ 42 |

“Plattsburg. One way,” Norman Dalrymple told the ticket-agent. He named his destination more loudly, more proudly than necessary, and he was gratified when the man next in line eyed him with sudden interest.

Having pocketed his ticket, Dalrymple noted, by his smart new wrist-watch with the luminous dial, that there was still twenty minutes before train-time. Twenty minutes—and Shipp had a vicious habit of catching trains by their coat-tails—a habit doubly nerve-racking to one of Dalrymple’s ponderous weight and deliberate disposition. That afforded ample leeway for a farewell rickey at the Belmont or the Manhattan; it was altogether too long a time to stand around. Mr. Dalrymple—his friends called him “Dimples”—had long since concluded that standing was an unnatural posture for human beings, and with every pound he took on there came a keener appreciation of chairs, benches, couches, divans—anything and everything of that restful pattern except hammocks. Hammocks he distrusted and despised, for they had a way of breaking with the sound of gun-shots and causing him much discomfiture.

Next to standing, Dimples abhorred walking, for the truth is he shook when he walked. Therefore he chose the Belmont, that haven of rest being close at hand; but ere he had gained the street his eye was challenged by a sight that never failed to arrest his attention. It was the open door of an eating-place—the station restaurant—with idle waiters and spotless napery within. Now, drink was a friend, but food was an intimate companion of whom Dimples never tired. Why people drank in order to be convivial or to pass an idle quarter of an hour, the while there were sweets and pastries as easily accessible, had always been a mystery to him. Like a homing pigeon, he made for this place of refreshment.

Overflowing heavily into a chair, he wiped his full-moon face and ordered a corn-starch pudding, an insatiable fondness for which was his consuming vice.

As usual, Shipp made the train with a three-second factor of safety in his favor, and, recognizing the imposing bulk of his traveling companion, greeted him with a hearty:

“Hello, Dimples! I knew you’d come.”

When they had settled themselves in their compartment Dalrymple panted, breathlessly:

“Gee! How I hate people who paw at departing trains.”

“I made it, didn’t I? You’re getting fat and slow—that’s what ails you. A fine figure of an athlete you are! Why, you’re laying on blubber by the day! You’re swelled up like a dead horse.”

“I know,” Dimples nodded mournfully. “I’ve tried to reduce, but I know too many nice people, and they all have good chefs.”

“Boozing some, too, I suppose?”

“Oh, sure! And I love candy.”

“They’ll take you down at Plattsburg. Say! It’s great, isn’t it? War! The real thing!” Shipp’s eyes were sparkling. “Of course it came hard to give up the wife and the baby, but—somebody has to go.”

“Right! And we’re the ones, because we can afford it. I never knew how good it is to be rich and idle—did you? But think of the poor devils who want to go and can’t—dependents, and all that. It’s tough on them.”

The other agreed silently; then, with a smile, he said:

“If they’re looking for officer material at Plattsburg, as they say they are, why, you’ve got enough for about three. They’ll probably cube your contents and start you off as a colonel.”

Dimples’s round, good-natured face had become serious; there was a suggestion of strength, determination, to the set of his jaw when he spoke.

“Thank God, we’re in at last! I’ve been boiling ever since the Huns took Belgium. I don’t care much for children, because most of them laugh at me, but—I can’t stand to see them butchered.”

Plattsburg was a revelation to the two men. They were amazed by the grim, business-like character of the place; it looked thoroughly military and efficient, despite the flood of young fellows in civilian clothes arriving by every train; it aroused their pride to note how many of their friends and acquaintances were among the number. But, for that matter, the best blood of the nation had responded. Deeply impressed, genuinely thrilled, Shipp and Dalrymple made ready for their physical examinations.

Dimples was conscious of a jealous twinge at the sight of his former team-mate’s massive bare shoulders and slim waist; Shipp looked as fit to-day as when he had made the All-American. As for himself, Dimples had never noticed how much he resembled a gigantic Georgia watermelon. It was indeed time he put an end to easy living. Well, army diet, army exercise would bring him back, for he well knew that there were muscles buried deep beneath his fat.

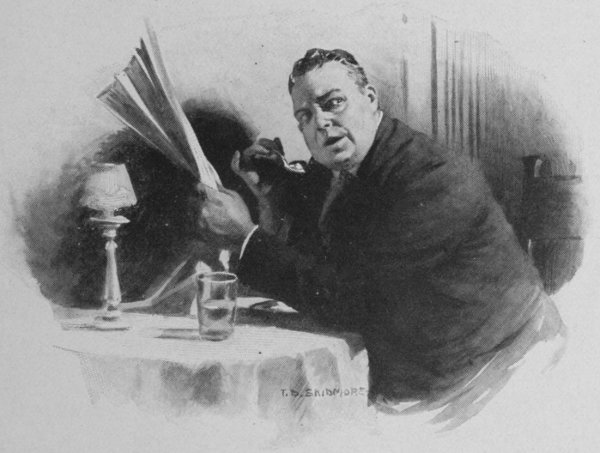

“Step lively!” It was an overworked medical examiner speaking, and Dimples moved forward; the line behind him closed up. As he stepped upon the scales the beam flew up; so did the head of the man who manipulated the counter-balance.

“Hey! One at a time!” the latter cried. Then with a grin he inquired, “Who’s with you?” He pretended to look back of Dimples as if in search of a companion, after which he added another weight and finally announced, in some awe:

“Two eighty-five—unless I’m seeing double.”

“‘Two eighty-five!’” The chief examiner started, then to Dalrymple he said: “Step aside, sir. Fall out.”

“What’s the idea?” Dimples inquired, with a rose-pink flush of embarrassment.

“You’re overweight. Next!”

“Why, sure I’m overweight; but what’s the difference?”

“All the difference in the world, sir. We can’t pass you. Please don’t argue. We have more work than we can attend to.”

Shipp turned back to explain.

“This is Norman Dalrymple, one of the best tackles we ever had at Harvard. He’s as sound as a dollar and stronger than a bridge. He’ll come down—”

“I’m sorry; but there’s nothing we can do. Regulations, you know.”

“Sure!” The man at the scales was speaking. “Two eighty-five isn’t a weight; it’s a telephone number.”

Dalrymple inquired, blankly:

“Do you mean to say I can’t get in? Why, that’s too absurd! I must get in! Can’t you fix it somehow?”

“You’re holding up the others. Won’t you please step aside?”

Shipp drew the giant out of line and said, quietly:

“Don’t argue. Get into your duds and wait for me. It will be all right. We know everybody; we’ll square it.”

But it was not all right. Nor could it be made all right. Weary hours of endeavor failed in any way to square matters, and the two friends were finally forced to acknowledge that here was an instance where wealth, influence, the magic of a famous name, went for naught. They were told politely but firmly that Norman Dalrymple, in his present state of unpreparedness, could not take the officers’ intensive-training course. Dimples was mortified, humiliated; Shipp felt the disappointment quite as keenly.

“That’s the toughest luck I ever heard of,” the latter acknowledged. “You’ll have to reduce, that’s all.”

But Dimples was in despair.

“It’s healthy fat; it will take longer to run it off than to run the Germans out of France. The war will be over before I can do it. I want to get in now. Too fat to fight! Good Lord!” he groaned. “Why, I told everybody I was going in, and I cut all my ties. Now to be rejected!” After a time he continued: “It knocks a fellow out to reduce so much. If I managed to sweat it off in a hurry, I’d never be able to pass my physical. That sort of thing takes months.”

Shipp silently agreed that there was some truth in this statement.

“Tough? It’s a disgrace. I—I have some pride. I feel the way I did when I lost our big game. You remember I fumbled and let Yale through for the winning goal. I went back to the dressing-room, rolled up in a blanket, and cried like a baby. You and the other fellows were mighty decent; you told me to forget it. But I couldn’t. I’ve never forgotten it, and I never shall.”

“Pshaw! You made good later.”

“I fell down when it was my ball. It’s my ball now, Shipp, and I’ve fallen down again. I’ve led a pretty easy, useless life, these late years, but—I feel this thing in Europe more than I thought I could feel anything. I’ve contributed here and there, let my man go, and economized generally. I’ve adopted whole litters of French orphans, and equipped ambulance units, and done all the usual things the nice people are doing, but I was out of the game, and I wanted—Lord! how I wanted to be in it! When we declared war, I yelled! I went crazy. And then along came your wire to join you in this Plattsburg course. Good old Shipp! I knew you’d get on the job, and it raised a lump in my throat to realize that you were sure of me. I—was never so happy”—the speaker choked briefly—“as while waiting for the day to arrive. Now I’ve fumbled the pass. I’m on the sidelines.”

Norman Dalrymple did not return home, nor did he notify his family of his rejection. Instead, he went back to New York, took a room at the quietest of his numerous clubs, engaged a trainer, and went on a diet. He minded neither of the latter very greatly for the first few days, but in time he learned to abhor both.

He shunned his friends; he avoided the club café as he would have avoided a dragon’s cave. The sight of a push-button became a temptation and a trial. Every morning he wrapped himself up like a sore thumb and ambled round the Park reservoir with his pores streaming; every afternoon he chased his elusive trainer round a gymnasium, striving to pin the man’s hateful features, and never quite succeeding. Evenings he spent in a Turkish bath, striving to attain the boiling-point and failing by the fraction of a degree. He acquired a terrifying thirst—a monstrous, maniac thirst which gallons of water would not quench.

Ten days of this and he had lost three pounds. He had dwindled away to a mere two hundred and eighty-two, and was faintly cheered.

But he possessed a sweet tooth—a double row of them—and he dreamed of things fattening to eat. One dream in particular tried the strongest fiber of his being. It was of wallowing through a No Man’s Land of blanc-mange with shell-craters filled with cream. Frozen desserts—ice-cold custards! He trembled weakly when he thought of them, which was almost constantly. Occasionally, when the craving became utterly unbearable, he skulked guiltily into a restaurant and ordered his favorite dish, corn-starch pudding.

OCCASIONALLY HE ORDERED HIS FAVORITE DISH, CORN-STARCH PUDDING

At the end of three weeks he was bleached; his face was drawn and miserable; he looked forth from eyes like those of a Saint Bernard. He had gained a pound!

HE HAD GAINED A POUND!

Human nature could stand no more. Listlessly he wandered into the club café and there came under the notice of a friend. It was no more possible for Dimples to enter a room unobserved than for the Leviathan to slip unobtrusively into port. The friend stared in amazement, then exclaimed:

“Why, Norm! You look sick.”

“‘Sick?’” the big fellow echoed. “I’m not sick; I’m dying.” And, since it was good to share his burden, he related what had happened to him. “Turned me down; wouldn’t give me a chance,” he concluded. “When I strained the scales, they wanted to know who I had in my lap. I’ve been banting lately, but I gain weight at it. It agrees with me. Meanwhile, Shipp and the others are in uniform.” Dimples bowed his head in his huge, plump hands. “Think of it! Why, I’d give a leg to be in olive drab and wear metal letters on my collar! ‘Sick?’ Good Lord!”

“I know,” the friend nodded. “I’m too old to go across, but I’m off for Washington Monday. A dollar a year. I’ve been drawing fifty thousand, by the way.”

“I’m out of that, too,” Dimples sighed. “Don’t know enough—never did anything useful. But I could fight, if they’d let me.” He raised his broad face and his eyes were glowing. “I’m fat, but I could fight. I could keep the fellows on their toes and make ’em hit the line. If—if they built ships bigger, I’d stowaway.”

“See here—” The speaker had a sudden thought. “Why don’t you try the Y?”

“‘The Y?’ Yale?”

“No, no. The Y. M. C. A.”

“Oh, that! I’ve hired a whole gymnasium of my own where I can swear out loud.”

“The Y. M. C. A. is sending men overseas.”

“I’m not cut out for a chaplain.”

“They’re sending them over to cheer up the boys, to keep them amused and entertained, to run huts—”

Dalrymple straightened himself slowly.

“I know; but I thought they were all pulpit-pounders.”

“Nothing of the sort! They’re regular fellows, like us. They manage canteens and sell the things our boys can’t get. They don’t let them grow homesick; they make them play games and take care of themselves and realize that they’re not forgotten. Some of them get right up front and carry hot soup and smokes into the trenches.”

“Me for that!” Dimples was rising majestically. “I could carry soup—more soup than any man living. The trenches might be a little snug for me round the waist, but I’d be careful not to bulge them. Cheer up the boys! Make ’em laugh! Say—that would help, wouldn’t it?” He hesitated; then, a bit wistfully, he inquired, “The Y fellows wear—uniforms, too, don’t they?”

“Well, rather. You can hardly tell them from the army.”

In Dalrymple’s voice, when he spoke, there was an earnestness, a depth of feeling, that his hearer had never suspected.

“Uniforms mean a lot to me lately. Every time I see a doughboy I want to stand at attention and throw out my chest and draw in my stomach—as far as I can. There’s something sacred about that olive drab. It’s like your mother’s wedding-dress, only holier, and decenter, if possible. Somehow, it seems to stand for everything clean and honorable and unselfish. The other day I saw the old Forty-first marching down to entrain, and I yelled and cried and kissed an old lady. Those swinging arms, those rifles aslant, those leggings flashing, and that sea of khaki rising, falling—Gee! There’s something about it. These are great times for the fellows who aren’t too old or too fat to fight.”

“Those Y men fight, in their way, just as hard as the other boys, and they don’t get half as much sleep or half as much attention. Nobody makes a fuss over them.”

Dimples waited to hear no more. The Y. M. C. A.! He had not realized the sort of work it was doing. But to keep the boys fit to fight! That was almost as good as being one of them. And he could do it—better than anybody. As his taxicab sped across town he leaned back with a sigh of contentment; for the first time in days he smiled. The Y. M. C. A. would have no scales! To the boys at the front a fat man might be funnier even than a skinny one. He was mighty glad he had heard of the Y in time. And it would be glad he had, for his name was worth a lot to any organization. No more dry bread and spinach—Gott strafe spinach! How he hated it! No more exercise, either; he would break training instantly and tell that high-priced reducer what he really thought of him. Useful work, work to win the war, was one thing, but this loathsome process of trying out abdominal lard—ugh! He decided to dine like a self-respecting white man that very night, and to deny himself nothing. The club chef made a most wonderful corn-starch pudding, indescribably delicious and frightfully fattening. At the mere thought, an eager, predatory look came into Dimples’s eyes. He would go overseas without delay; he would be in France doing his bit while Shipp and the others were still rehearsing their little tricks and learning to shout, “Forward, ouch!” Of course those fellows would win commissions—they were welcome to the glory—but meanwhile he would be right down in the dirt and the slime with the boys in leggings, cheering them up, calling them “Bill” and “Joe,” sharing their big and their little troubles, and putting the pep into them. That’s what they needed, that’s what the world needed—pep! It would win the war.

Dalrymple was surprised when he entered the Y. M. C. A. quarters to find them busy and crowded. He sent in his card, then seated himself at the end of a line of waiting men. He wondered if, by any chance, they could be applicants like himself, and his complacency vanished when he learned that they could be—that, indeed, they were. His surprise deepened when he saw that in no wise did they resemble psalm-shouters and Testament-worms such as he had expected, but that, on the contrary, they looked like ordinary, capable business and professional men.

Dimples wondered if this were, after all, a competitive service. He broke into a gentle, apprehensive perspiration.

His name was called finally; he rose and followed a boy into a room where several men were seated at a table. Two of them were elderly, typical; they wore various unbecoming arrangements of white whiskers, and one glance told Dimples that they knew a lot about God. One of the others resembled a judge, and he it was who spoke first.

“You wish to go to France for the Y. M. C. A.?” the latter inquired.

“Yes, sir. They wouldn’t let me in at Plattsburg. I’m too fat, or the camp is too small. I’d very much like to go overseas.”

“It is hardly necessary to ask if you have had experience in promoting social entertainments and recreations.”

The speaker smiled. Dimples’s face broke into an answering grin.

“‘Entertainments!’ ‘Recreations!’ They are my stock in trade. I’m an authority on all kinds of both; that’s what ails me.”

Another member of the board inquired:

“Are you a temperate man, Mr. Dalrymple?”

“Oh no!” Dimples shook his head. “Not at all.”

“What sort of—er—beverages do you drink?”

“What have you got?” the young giant blithely asked. Noting that his comedy met with no mirthful response, he explained more seriously: “Why, I drink practically everything. I have no particular favorites. I dare say it’s against your rules, so I’ll taper off if you say so. I’d take the Keeley to get across. Of course I make friends easier when I’m moderately lit—anybody does. I’m extraordinarily cheerful when I’m that way. You’ve no idea how—”

“Surely you understand that we tolerate no drinking whatever?”

“No, sir; I didn’t fully understand. I know several Christian young men who drink—more or less. However, that’s all right with me. I’ve never tried to quit drinking, so I’m sure I can.”

“Are you familiar with the character and the aims of the Young Men’s Christian Association?” One of the white-bearded gentlemen put this question.

“In a general way only. I knew you had a gym and a swimming-tank and ran some sort of a Sunday-school. It never appealed to me, personally, until I heard about this work you’re doing in France. That’s my size. That fits me like a pair of tights.”

“Do you play cards?”

“Certainly. I’m lucky, too. Any game the boys want, from bridge to black jack.”

“I mean—do you play for money?”

“Is that on the black list, too?” Dimples’s enthusiasm was slowly oozing away. Noting the falling temperature of the room, he confessed honestly, but with some reluctance: “I suppose I do all of the things that ordinary idle fellows do. I drink and gamble and swear and smoke and overeat and sleep late. But that doesn’t hurt me for carrying soup, does it?”

No one answered this challenge; instead, he was the recipient of another question that caused him to squirm.

“Would you consider yourself a moral young man?”

Slowly the applicant shook his head.

“To what Church do you belong?”

“I don’t.”

“How long since you attended divine service?”

“A good many years, I’m afraid.”

There followed a moment of silence; the men at the table exchanged glances, and into Dimples’s face there came an apprehensive, hunted look. He wet his lips, then said:

“Anyhow, you can’t accuse me of mendacity. I don’t lie. Now that you know the worst about me, I’d like to inventory my good points.” This he proceeded to do, but in all honesty it must be said that his showing was not impressive. Never having given serious thought to his virtues, there were few that he could recall at such short notice. He concluded by saying: “I know I can make good if you’ll give me a chance. I—I’ll work like a dog, and I’ll keep the boys laughing. I won’t let them get homesick. I— Why, gentlemen, this is my last chance! It will break my heart if you turn me down.”

Not unkindly the “judge” said:

“We will consider your application and notify you.”

This very kindliness of tone caused the fat man to pale.

“I know what that means,” he protested. “That’s Y. M. C. A. for ‘no.’ Let me go,” he implored. “I’ll serve. I’ll stand the punishment. I’m strong and I’ll work till I drop. You won’t be ashamed of me, honestly.”

“We’ll notify you without delay, Mr. Dalrymple.”

There was no more to be said. Dimples wallowed out of the room with his head down.

That night he walked the soft-carpeted floor of his chamber until very late, and when he did go to bed it was not to sleep. Daylight found him turning restlessly, his eyes wide open and tragic. Another failure! Within him the spirit of sacrifice burned with consuming fury, but there was no outlet for it. Through his veins ran the blood of a fighting family; nevertheless, a malicious prank of nature had doomed him to play the part of Falstaff or of Fatty Arbuckle. What could he do to help? Doubtless he could find work for his hands in ship-yard or foundry, but they were soft, white hands, and they knew no trade. Give? He had given freely and would give more; but everybody was giving. No; action called him. He belonged in the roar and the din of things where men’s spirit tells.

That afternoon he was waddling down Fifth Avenue when Mr. Augustus Van Loan stopped him to exclaim:

“Good Heavens, Dimples! What has happened to you?”

Van Loan was a malefactor of great wealth. His name was a hissing upon the lips of soap-box orators. None of his malefactions, to be sure, had ever yet been uncovered, nor were any of the strident-voiced orators even distantly acquainted with him, but his wealth was an established fact of such enormity that in the public eye he was suspect.

“I’m all in,” the disconsolate mammoth mumbled, and then made known his sorrow. “Too fat to get in the army; too soft morally to get in the Y. M. C. A. I didn’t know how rotten I am. I can’t carry a gun for my country; I’m not good enough to lug soup to the boys who do. And, meanwhile, the Huns are pressing forward.”

Van Loan eyed him shrewdly.

“Do you feel it as badly as all that?”

Dalrymple nodded.

“I don’t want to be a hero. Who ever heard of a hero with a waistband like mine? No; I’d just like to help our lads grin and bear it, and be a big, cheerful fat brother to them.”

Without a word Mr. Van Loan took a card from his pocket and wrote a few lines thereon.

“Take that down to the Y and tell them to send you on the next ship.” He handed Dimples the card, whereupon the giant stared at him.

“D—d’you know that outfit?”

“Know it?” Van Loan smiled. “I’m the fellow who’s raising the money for them. They’ve darn near broken me, but—it’s worth it.”

With a gurgling shout Dimples wrung the malefactor’s hand; then he bolted for the nearest taxi-stand and squeezed himself through a cab door.

Ten minutes later he entered the boardroom at the Y. M. C. A. and flung Van Loan’s card upon the table.

“Read that!” he told the astonished occupants.

The “judge” read and passed the card along.

“Where do I go from here?” Dimples demanded, in a voice of triumph.

“Why”—the “judge” cleared his throat—“to your tailor’s for a uniform, I should say.”

Late the following afternoon, as the judicial member of the Y examiners was leaving the building, his path was barred by a huge, rotund figure in khaki which rose from a bench in the hall. It was Dalrymple.

“I’ve been blocking traffic here for an hour,” the giant explained. “Look at me! It’s the biggest uniform in New York, and it was made in the shortest time.” Noting the effect his appearance created, he went on, “I suppose I do look funny, but—there’s nothing funny to me about it.”

The elder man’s face grew serious.

“I’m beginning to believe you’ll make good, Dalrymple. I hope so, for your sake and for the sake of the Association. If you don’t, we’ll have to order you back.”

“I’ll take that chance. You gentlemen think I’m unfit to wear these clothes and—maybe I was yesterday, or even this morning. But when I saw myself in this uniform I took stock and cleaned house. I got all my bad habits together and laid them away in moth-balls for the duration of the war.”

“That means something for a man like you. What induced you to do it?”

“This.” Dimples stroked his khaki sleeve with reverent, caressing fingers. “It’s almost like the real thing, isn’t it? Not quite, but near enough. It’s as near as I can ever get, and I sha’n’t do anything to disgrace it. I can shut my eyes and imagine it is the real thing. I don’t suppose you understand in the least what I’m driving at—”

“I think I understand thoroughly, sir. But don’t believe for a moment there is anything counterfeit, anything bullet-proof, about what you have on. You will be fighting, Dalrymple, just the same as the other boys; every service you perform, every word of cheer, every deed of kindness, will be a bomb dropped back of the German lines. Why, man, do you know that the work of the Y. M. C. A. adds ten per cent. to our fighting force? It’s a fact; Pershing says so. If you make good, you’ll be adding one man to every ten you meet.”

“‘One man to every ten!’” Dimples breathed. “That’s great! That’s more than I could have done the other way. I’m good for something, after all.”

It seemed impossible that a wealthy, prominent young New York club-man could so quickly, so utterly drop out of sight as did Dimples Dalrymple. One day he was in his familiar haunts, a rotund, mirth-provoking spectacle in his bulging uniform, with his tiny overseas cap set above his round, red face like the calyx of a huge ripe berry; the next day he was gone, and for several months thereafter his world knew him not.

A ROTUND, MIRTH-PROVOKING SPECTACLE IN HIS BULGING UNIFORM, WITH HIS TINY OVERSEAS CAP SET ABOVE HIS ROUND, RED FACE LIKE THE CALYX OF A HUGE RIPE BERRY

Captain Shipp, now attached to a famous division awaiting embarkation, was the first to hear from him. He read Dimples’s letter twice before passing it on. It ran as follows:

Dear Brigadier-General,—You must be all of the above by this time; if not, there is favoritism somewhere and you ought to complain about it. Probably you’re wondering where I am. Well, that’s your privilege, Brig. I’m in a two-by-four village with a name as long as the Frisco System, and you’ll instantly recognize it when I tell you it has one white street and a million rats. There are no houses whatever. Further information might give aid and comfort to the enemy.

I’ve written lots of letters back home, but this is the first one of my own that I’ve had time for. I’m in the game, Brig, and I haven’t fumbled the ball. I live in a little tin shanty with a sand-bag roof, and I wear a little tin hat that holds just enough warm water to shave with. It held more—until lately; now there’s a hole in it that I wouldn’t trade for the Hudson “tube.” I was starting out with two cans of hot cocoa when the street was shelled. I spilled the boys’ cocoa and got a dent in my own, but those Bessemer derbies are certainly handy shock-absorbers. I woke up with my head in Dr. Peters’s lap.

Right here I must make you acquainted with Pete. He’s a hundred-pound hymn-weevil, and the best all-round reverend that ever snatched a brand from the burning. He dragged me in under cover all alone, and he used no hooks. Pretty good for a guy his size, eh?

Pete and I are partners in crime—and, say, the stuff we pull in this hut! Movies, theatricals, concerts, boxing-bees—with the half-portion reverend in every scrimmage. He’s a Syncopated Baptist, or an Episcopalian Elk, or something; anyhow, he’s nine parts human and one part divine. That’s the way the Y is wearing them over here. He’s got the pep, and the boys swear by him. When the war is over he hopes to get a little church somewhere, and I’m going to see that he does, if I have to buy it, for I want to hear him preach. I never have heard him, but I’ll bet he’s a bear. Take it from me, he’ll need a modest cathedral with about six acres of parking-space inside and a nail in the door for the S. R. O. sign.

We have a piano, and games, and writing-materials, and a stock of candy and tobacco and chocolate and stuff like that. I haven’t tasted a single chocolate. Fact! But it has made an old man of me. Gee! I’d give that loft building on Sixteenth Street to be alone with an order of corn-starch pudding. However, barring the fact that I haven’t lost an ounce in weight, I’m having a grand time, for there’s always something to do. Details are constantly passing through, to and from the front-line trenches, which (whisper) are so close that we can smell the Germans. That’s the reason we wear nose-bags full of chloride of lime or something. Pete and I spend our days making millions of gallons of tea and coffee and cocoa, and selling canned goods, and sewing on buttons, and cracking jokes, and playing the piano, and lugging stretchers, and making doughnuts, and getting the boys to write home to mother, and various little odd jobs; then, at night, we take supplies up to the lads in the front row of the orchestra. That’s a pretty game, by the way, for a man of my size. Nobody ever undertakes to pass me in a trench; I lie down and let them climb over. It keeps the boys good-natured, and that’s part of my job. “Hill Two Eighty-five”—that’s what they call me.

We had a caller to-day. One of the Krupp family dropped in on us and jazzed up the whole premises. There is Bull Durham and rice-papers and chocolate and raspberry jam all over this village, and one corner of our hut has gone away from here entirely. We haven’t found the stove, either, although Pete retrieved the damper, and the rest of it is probably somewhere near by.

Of course I had nothing hot for the boys when I went up to-night. It was raining, too, and cold. But they didn’t mind. They don’t mind anything—they’re wonderful that way. We all had a good laugh over it, and they pretended they were glad it was the stove and not I that got strafed. I really believe they like me. Anyhow, they made me think they do, and I was so pleased I couldn’t resist sitting down and writing you. Altogether, it was a great day and a perfect evening.

During the first few weeks after his arrival in France Captain Shipp had no time whatever for affairs of his own, but a day came finally when he took a train for a certain base close up behind an American sector, intending there to more definitely locate Dimples’s whereabouts and to walk in upon him unannounced. It would be a memorable reunion; he could hear now the big fellow’s shout of welcome. That genial behemoth would have a tale to unfold, and they would talk steadily until Shipp’s leave was up.

But bad news was waiting at the base—news that sent the captain hurrying from first one hospital to another.

“Dalrymple? Oh yes, he’s here,” an orderly informed the distracted visitor.

“Is he— May I see him?”

A small, hollow-eyed man with a red triangle upon his sleeve rose from a chair and approached to inquire:

“Are you, by any chance, Captain Shipp?”

“I am.”

“Dimples has often spoken of you. He has been expecting you for weeks. I’m just going in.”

“You are Doctor Peters—Pete?” The Y secretary nodded. “What ails him? I heard he was wounded—”

“Yes. His leg. It’s very serious. I come every day.”

The speaker led the way, and Shipp followed down a long hall redolent of sickly drug smells, past clean white operating-rooms peopled with silent-moving figures, past doors through which the captain glimpsed dwindling rows of beds and occasional sights that caused his face to set. In that hushed half-whisper assumed by hospital visitors, he inquired:

“How did it happen?”

“There was a raid—a heavy barrage and considerable gas—and it caught him while he was up with supplies for the men. He began helping the wounded out, of course. It was a nasty affair—our men were new, you see, and it was pretty trying for green troops. They said, later, that he helped to steady them quite as much as did their officers.”

“I can believe that. He’s a man to tie to.”

“Yes, yes. We all felt that, the very first day he came. Why, he was an inspiration to the men! He was mother, brother, pal, servant to the best and to the worst of them. Always laughing, singing—There! Listen!”

The Reverend Doctor Peters paused inside the entrance to a ward, and Shipp heard a familiar voice raised in quavering song:

“Why”—Shipp uttered a choking cry—“he’s out of his head!”

“Oh yes; he has been that way ever since they amputated.”

“‘Amp—’ Good God!” Shipp groped blindly for support; briefly he covered his eyes. Then, like a man in a trance, he followed down the aisle until he stood, white-lipped and trembling, at the foot of Dalrymple’s bed.

It was difficult to recognize Dimples in this pallid, shrunken person with the dark, roving eyes and babbling tongue. The voice alone was unchanged; it was husky, faint as if from long, long use, but it was brave and confident; it ran on ceaselessly:

“Keep your nerve up, pal; you’re standing it like a hero, and we’ll have you out to the road in no time. Smokes! I tell you they must have smokes if you have to bring ’em in on your back—Gangway for the soup-man! Come and get it, boys. Hot soup—like mother used to make. Put on the Harry Lauder record again. Now then, all together:

The little minister had laid a cool hand upon Dimples’s burning brow; his head was bowed; his lips were moving.

“When did you write to your mother last?” the sick man babbled on. “Sure I’ll post it for you, and I’ll add a line of my own to comfort her—Water! Can’t you understand? He wants water, and mine’s gone. Too fat to fight! But I’ll make good; I’ll serve. Give me a chance—Steady, boys! They’re coming. They’re at the wire. Now give ’em hell! We’ll say it together, old man: ‘Our Father which art in heaven, hallowed be thy name—’”

There were scalding tears in Shipp’s eyes; his throat was aching terribly when Doctor Peters finally led him out of the ward. The last sound he heard was Dalrymple’s voice quavering:

“I had my hands full at the hut, for the wounded were coming in,” Doctor Peters was saying, “but every one says Dimples did a man’s work up there in the mud and the darkness. Some of the fellows confessed that they couldn’t have hung on, cut off as they were, only for him. But they did. It was late the next day before we picked him up. He was right out in the open; he’d been on his way back with a man over his shoulders. He was very strong, you know, and most of the stretcher-bearers had been shot down. The wounded man was dying, so Dimples walked into the barrage.”

“And he was afraid he wouldn’t make good!” Shipp muttered, with a crooked, mirthless smile.

“Yes—imagine it! There was never a day that he didn’t make me ashamed of myself, never a day that he didn’t do two men’s work. No task was too hard, too disagreeable, too lowly. And always a smile, a word of cheer, of hope. Our Master washed people’s feet and cooked a breakfast for hungry fishermen. Well, the spirit of Christ lives again in that boy.”

Shipp’s leave had several days to run; such time as he did not spend with Doctor Peters he put in at Dimples’s bedside. He was there when the delirium broke; his face was the first that Dimples recognized; his hand was the first that Dimples’s groping fingers weakly closed upon.

They had little to say to each other; they merely murmured a few words and smiled; and while Dimples feasted his eyes upon the brown face over him, Shipp held his limp, wasted hand tight and stroked it, and vowed profanely that the sick man was looking very fit.

Later in the day the captain said, with something like gruffness in his voice:

“Lucky thing you pulled yourself together, old man, for you’re booked to take part in a ceremony to-morrow. A famous French general is going to kiss you on both cheeks and pin a doodad of some sort on your nightie.”

Dimples was amazed.

“Me? Why, the idea!”

“Sure!” Shipp nodded vigorously. “Ridiculous, isn’t it? And think of me standing at attention while he does it. Pretty soft for you Y fellows. Here you are going home with a decoration before I’ve even smelled powder.”

“Oh, I’m not going home,” the other declared. “Not yet, anyhow. A one-legged man can sell cigarettes and sew on buttons and make doughnuts just as well as a centipede.”

A smiling nurse paused at the bed to say:

“You’re awfully thin, Mr. Dalrymple, but we’ll soon have you nice and fat again. The doctor says you’re to have the most nourishing food—anything you want, in fact.”

“‘Anything?’”

“Anything within reason.”

Dimples grinned wistfully, yet happily.

“Gee!” said he. “I’d like some cornstarch pudding.”

Cover, full stop inserted after ‘D,’ “T. D. SKIDMORE”

Page 23, ‘pi’ changed to ‘pin,’ “striving to pin the man’s hateful”