Title: When Sarah Saved the Day

Author: Elsie Singmaster

Release date: June 7, 2016 [eBook #52257]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, Ryan Cowell and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

BOOKS BY ELSIE SINGMASTER

When Sarah Saved the Day

When Sarah Went to School

Gettysburg

Katy Gaumer

Emmeline

The Long Journey

The Life of Martin Luther

John Baring's House

Basil Everman

Ellen Levis

Bennett Malin

The Hidden Road

A Boy at Gettysburg

Bred in the Bone

Keller's Anna Ruth

'Sewing Susie'

What Everybody Wanted

Virginia's Bandit

You Make Your Own Luck

A Little Money Ahead

WHEN SARAH SAVED THE DAY

BY ELSIE SINGMASTER

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

The Riverside Press Cambridge

COPYRIGHT, 1909, BY ELSIE SINGMASTER

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED INCLUDING THE RIGHT TO REPRODUCE THIS BOOK OR PARTS THEREOF IN ANY FORM

Published October 1909

PRINTED IN THE U.S.A.

TO CAROLINE HOOPES SINGMASTER

| I. | Uncle Daniel's Offer | 1 |

| II. | The Rebels take to Arms | 24 |

| III. | Uncle Daniel steals a March | 44 |

| IV. | There is Company to Supper | 62 |

| V. | The Blow falls | 79 |

| VI. | The Orphans' Court | 97 |

| VII. | "And now We will go Home" | 116 |

| Sarah did not speak, she only hid her eyes (Page 126) | Frontispiece |

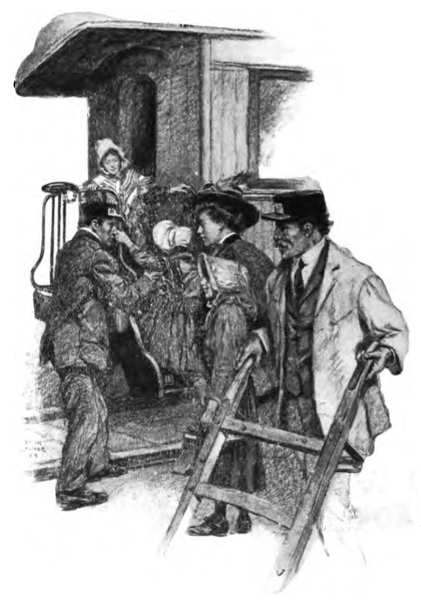

| Go away and leave me with my children | 20 |

| The station agent looked at them curiously | 94 |

| Uncle Daniel smiled and drew out two shining dollars | 112 |

Sarah Wenner, who was fifteen years old, but who did not look more than twelve, hesitated in the doorway between the kitchen and the best room, a great tray of tumblers and cups in her hands.

"Those knives and forks we keep always in here, Aunt Mena. We do not use them for every day."

Her aunt, Mena Illick, lifted the knives from the drawer where she had laid them. One could see from her snapping black eyes that she did not enjoy being directed by Sarah. But order was order, and no one ever justly accused a Pennsylvania German housewife of not putting things where they belonged. She laid the knives on the table for Sarah to put away.

The kitchen seemed strangely lonely and empty that evening, in spite of the number of persons who were there.

Besides little Sarah, who was the head of the Wenner household, now that the father was dead and the oldest son had gone away, and her Aunt Mena, who had driven thither for the funeral that afternoon, there was an uncle, Daniel Swartz, and his wife Eliza, who was just then wringing out the tea-towels from a pan of scalding suds, and the Swartzes' hired man, Jacob Kalb, short and stout, with a smooth-shaven face and tiny black eyes.

Daniel Swartz sat beside the wide table, the hired man by his side. On chairs against the wall, sitting now upright, now leaning against each other when sleep overpowered them, were the Wenner twins, Louisa Ellen and Ellen Louisa, whose combination of excessive slenderness and appearance of good health could be due only to constant activity. In their waking moments they looked[Pg 3] not unlike eager little grasshoppers, ready for a spring.

The last member of the party lay peacefully sleeping on the deep settle before the fireplace. His wide blue eyes were closed, his chubby arms thrown above his head. Worn with the excitement of the day, too young to realize that the cheerful, merry father whom they had carried away that afternoon would never return, he slept on, the only one entirely at ease.

Daniel Swartz rose every few minutes to cover him more thoroughly. Aunt 'Liza and Aunt Mena watched Uncle Daniel, the eyes of the twins rested with scornful disfavor upon Jacob Kalb, and Sarah watched them all. Her tired eyes widened with apprehension when she saw her uncle bend over Albert as if he were his own, and she bit her lips when she saw Aunt 'Liza and Aunt Mena whispering together. Returning with the empty tray, she moved swiftly across the kitchen to where the twins were sitting.

At that moment they were awake and engaged in their favorite pastime of teasing Jacob Kalb.

Jacob had an intense desire to be considered English, and in an unfortunate moment had translated his name, not realizing how much worse its English equivalent, "Calf," would sound to English ears than the uncomprehended German "Kalb." It was the twins' older brother, William, who had now been away from home so long that they had almost forgotten him, who had heard Jacob telling his new name to some strangers.

"Ach, no, I cannot speak German very good. I am not German. My name is Jacob Calf."

He saw in their faces that he had made a mistake, but it was too late to retract. Besides, William Wenner, whom he hated, and who had been to the Normal School, had heard, and as long as Jacob lived the name would cling to him. Ellen Louisa and Louisa[Pg 5] Ellen, accustomed to shout it at him from a safe vantage-ground on their own side of the fence, called it softly now when the older people were talking, "Jacob Calf! Jacob Calf!"

Then, suddenly, each twin found her arm clutched as though in a vise.

"Ellen Louisa and Louisa Ellen, be still. Not a word! Not a word!"

"But—" began the twins together. Sarah had always aided and abetted them. It was Sarah who had invented such brilliant rhymes as,

Sarah's nonsense had amused the father and delighted the children for many weary months. Why had she suddenly become so strange and solemn? To the twins death had as yet no very terrible meaning, and they knew nothing of care and responsibility. Each jerked her arm irritably away from Sarah's hand. Why didn't she tell the aunts and[Pg 6] uncle to go home and let them go to bed? And why was Jacob Kalb there in the kitchen? Why—But the twins were too drowsy to worry very long. Leaning comfortably against each other, they fell asleep once more.

Sarah continued her journey across the room to gather up a pile of plates. She sympathized thoroughly with the twins in their hatred for the hired man. He had no business there. If the uncle and aunts wished to discuss their plans, they should do it alone, and not in the presence of this outsider. But he knew all Uncle Daniel's affairs, and was now too important a person to be teased.

Sarah put the plates into the corner-cupboard, arranging them in their accustomed places along the back. She had seen Aunt Eliza's and Aunt Mena's eyes glitter as they washed them.

"It ain't one of them even a little bit cracked," said Aunt 'Liza. "They should[Pg 7] have gone all along to pop and not to Ellie Wenner."

"And the homespun shall come to me," said Aunt Mena.

Sarah had been ready with a sharp reply, but had checked it on her lips. "Pop" and Aunt Mena, indeed! She thought of their well-stocked houses. Her mother had had few enough of the family treasures.

She stopped for a moment to wipe her eyes before she went back to the kitchen, standing by the window and looking out over the dark fields. There was no lingering sunset glow to brighten the sky, but Sarah's eyes seemed to pierce the gloom, as though she would follow the sun to that distant country where her brother had vanished.

Two hundred years before, their ancestors had come from the Fatherland, and ever since, adventurous souls had insisted upon leaving this safe haven to penetrate still farther into the enchanted West. Whole families had gone; in Ohio were towns and[Pg 8] counties whose people bore the familiar Pennsylvania German names, Yeager, Miller, Wagner, Swartz, Schwenk, Gaumer. Dozens of young men had gone to California in '49. Some had returned, some were never heard of again. Fifty years later, the rumor of gold drew young men away once more, this time into the bitter cold of the far Northwest.

William's indulgent father had let him go almost without a word of objection. He knew what wanderlust was. And for some reason William had seemed suddenly to become unhappy. The farm was small, too small to support them all; there were four younger children, and William, to his father's and mother's secret delight, had declined his Uncle Daniel's offer of adoption. They had let him take his choice between the straitened, simple life at home and the prospect of ease and wealth at Uncle Daniel's.

Uncle Daniel had never forgiven them or him. William's success at the Normal School, where, with great sacrifice, he was sent,[Pg 9] irritated him; William's election as a township school director made him furious.

It is safe to say that Daniel Swartz and Jacob Kalb were the only persons in Upper Shamrock township who did not like William. Even Miss Miflin, the pretty school-teacher, went riding with him in his buggy, and all the farmers and the farmers' wives were fond of him.

"His learning doesn't spoil him," said Mrs. Ebert, who lived on the next farm. "He is just so nice and common as when he went away."

And then he had gone away again, not to the Normal School, but to Alaska. Sarah remembered dimly how he and his father had pored over the old atlas after the twins had been put, protesting, to bed, and the mother had sat with Albert in her arms, and, when the men were not watching her, with a sad, frightened look in her eyes. Sarah could understand both her brother's eagerness and her mother's sadness. Little did any[Pg 10] of them foresee what the next few years were to bring. The little mother went first, with messages for William on her last breath, and now the dear, cheerful father. Surely, if William could have guessed, he would never have gone so far away.

But for two years they had had no word. At first there had been frequent letters. When he reached Seattle, it had been too late for him to go north, and he waited for spring. Then it was difficult to get passage, and there was another delay. After that the letters grew fewer and fewer, and finally ceased.

Meanwhile, a strange shadow had crept over William's name and William's memory. Pretty Miss Miflin asked no more about him, Uncle Daniel came and spoke sharply to Sarah's father and mother and then they talked about him in whispers when they thought Sarah did not hear. Once she caught an unguarded sentence:—

"I have written again. If he does not answer, he is dishonest or—"

"No!" her mother had answered sharply. "No! William will come home, and then he will tell us!"

But William had neither come nor written. So far as they knew he had not heard of his mother's death, and there was no telling whether the announcement of his father's death would reach him. Perhaps he, too, might be—

But that thought Sarah would not admit for the fragment of a second to her burdened mind. She wiped away her tears once more, and then she almost succeeded in smiling. The black clouds in the west were parting. Here and there a star peeped through. She knew a few of them by name. There was Venus,—Sarah, whose English was none of the best, would have called it "Wenus,"—her father had loved it. Often he had watched it from this window. Perhaps William saw it, too, in that mysterious night in which he lived. Ah, what tales there would be to tell when William came home!

Her father's death had meant the giving up of all Sarah's dreams and hopes. Three years before, they had driven one day to a neighboring town. Drives were not frequent in that busy household. Sarah remembered yet how fine Dan and Bill had looked in their newly blackened harness, and how proud she had felt, sitting with her father on the front seat.

They had seen many wonderful things: a paint-mill, a low, long building, covered, inside and out, with thick layers of red powder; and the ore mines, great holes in the yellow soil, where the ore needed only to be dug out from the surface; and they had stopped to watch a cast at a blast-furnace. But most wonderful of all was the "Normal." Sarah had seen the slender tower of the main building against the sky.

"What is then that?" she had asked.

"That is the Normal, where William went to school."

"Ach, yes, of course!" cried Sarah.

All the delightful things in the world were connected with William. Her father looked down at the sparkling eyes in the eager little face. He had had little education himself, but he knew its value.

"Would you like, then, to come here to school?"

Sarah's face grew a deep crimson. She looked at the trees, the wide lawns, the young people at play in the tennis-courts.

"I? To school? Here?"

"Of course. Wouldn't you like to be such a teacher like Miss Miflin?"

Sarah's face grew almost white. It was as though he had said, "Would you like to be President of the United States?"

"I! Like Miss Miflin! Ach, pop, do you surely mean it? But I am too dumb."

Her father laughed.

"No, you are not dumb. If you are good, and if you study, you dare come here."

Ah, but how could one study with a sick mother, and then a sick father and a baby[Pg 14] to look after, and twins like Ellen Louisa and Louisa Ellen to bring up, and—

Sarah went slowly back to the kitchen. It was like going into church, all was so still and solemn. Albert and the twins slept, Aunt 'Liza and Aunt Mena had taken their places on the opposite side of the table from Uncle Daniel and Jacob Kalb.

"Come, come," cried Uncle Daniel impatiently. He did not like black-eyed little Sarah. She looked too much like her father, whom his sister had married against his will. "We must get this fixed up. Sit down, once."

Sarah sat down on the nearest seat, which was the lower end of the settle on which Albert lay. She wiped her hot face on her gingham apron, then laid her hand on Albert's stubby little shoes, as though she needed something to hold to.

"Don't," commanded Uncle Daniel. "You wake him up if you don't look a little out."

Sarah's eyes flashed. As though she would wake him, her own baby, whom she had tended for three years! She wanted to tell them to go, to leave her alone with her children. But again she was wisely silent. She did not know yet what it was that her uncle meant to "fix up."

Swartz pulled his chair a little closer to the table. He looked uncomfortable in his black suit and his stiff collar. Occasionally he slipped his finger behind it and pulled it away from his throat, as though it were too tight. It seemed as if his remarks were for the benefit of Sarah alone, even though he did not look at her, for Aunt Mena and Aunt 'Liza and the hired man helped him out with an occasional word as if they knew beforehand what he meant to say.

He, too, had his dreams. One was to see a son in his house; another was to see the Wenner farm once more united to his own as it had been in his father's lifetime. Then he would have the old border on the creek.[Pg 16] There was also talk of the strange, new "electricity cars" running along the creek. That would double the value of the farm.

But he said nothing of this in his speech to Sarah.

"A couple of years back," he began, "I made an offer to Wenner. I said to him, 'I will take William and bring him up right, and then he can have the farm when I am no longer here.' That is what I said to your pop. But he wouldn't have it. He had to send William instead to school."

"Then what did he get for his schooling?" asked Jacob Kalb.

"I never had no schooling," said Uncle Daniel. "And you see where I am. Nobody needs schooling but preachers and teachers."

"I don't believe in schooling," said Aunt Eliza.

"Nor I," said Aunt Mena.

Sarah's eyes continued to flash, but she said nothing. She knew that they were expressing their scorn for her father's judg[Pg 17]ment, but she was too tired to answer. If they would only go home! She saw her uncle look at little Albert. He need not think she would give him up. Sarah almost laughed at the idea. Then she heard that her uncle had begun to speak again.

"Well, now I have another offer to make. Mena will take Ellie and Weezy. I will take Albert. He shall be Albert Swartz from now on. And Sarah can come also to us to help to work."

"You will have to be a good little girl and work right," admonished Aunt 'Liza.

"And you will have a good home," put in Jacob Kalb. "You and the zwillings (twins)." There were times when Jacob's English vocabulary was not equal to the demands upon it.

Sarah's pale cheeks grew a little whiter. But Uncle Daniel had said it was an offer. An offer could be declined.

"But we are all going to stay here together like always," she said. "I and Albert and the twins."

She saw their anger in their faces.

"What!" said Aunt Eliza.

"Such dumb talk!" cried Uncle Daniel.

"Are you then out of your mind?" asked Aunt Mena.

Jacob Kalb alone said nothing. But Sarah saw him smile. He planned to live in the Wenner farmhouse.

"Will you plough?" demanded Uncle Daniel.

"Or plant the seeds?" asked Aunt 'Liza.

"Or harvest?" said Aunt Mena.

Sarah spoke quietly. "I have it all planned. Ebert will farm like always for the half."

"The half!" repeated Uncle Daniel. "Should we then give this good money to Ebert? The half! I will farm."

"Well, then," said Sarah. "But you must pay the half to us because we must live."

"Pay the half to you!" exclaimed Aunt Mena.

"It is our farm," replied Sarah. "It was my mom's and my pop's farm. It isn't yours."

"Well, it will be mine," said Uncle Daniel. "What would such children make with such a farm?"

"I am not a child," answered Sarah firmly. "For three years already I managed the farm while my pop was sick. And it is William's farm so much as ours. And when William comes home—"

"William will never come home," said Uncle Daniel.

Sarah got up from the old settle.

"William will come home!" she cried. "It don't make nothing out if you do give us homes. If you take the farm, it will be stealing."

"Ei yi!" reproved Aunt Mena shortly. "That is no word for little girls!"

"A whipping would be good for her," offered Jacob Kalb.

"You haven't any right here, Jacob C-calf," cried Sarah.

Jacob's little eyes narrowed. "It is no way for little girls to talk when their brothers steal school-board money, and go off and their pops have to pay it," he said.

For a moment there was silence, then a reproving murmur from Aunt Mena.

"It isn't true!" cried Sarah. "It isn't true!" Suddenly she remembered her father's sadness, her mother's tears.

She burst into wild crying. "Ach, I wish you would go away and leave me with my children! I will get good along, if you will only let me be. Albert should be this long time in his bed. I wish you would go home."

She bent to lift the sleeping child. But her uncle pushed her aside.

"Albert is coming home with me," he said, as he lifted him up. "Jacob, put Weezy and Ellie in the carriage with Aunt Mena."

Sarah tried to keep her hold of the little boy. But she struggled in vain. Jacob Kalb picked up one of the twins.

"Ellen Louisa!" called Sarah.

Ellen Louisa struggled into wakefulness.

"Let me down, Jacob Calf; let me down!" She began to cry. "Ja-cob Calf, you m-make m-me l-laugh; let me down!"

But Ellen Louisa was borne shrieking from the room.

"Louisa Ellen!" called Sarah.

But Louisa Ellen found herself closely held by Aunt 'Liza and Aunt Mena, and she, too, was led forth.

"You are thieves!" cried Sarah wildly.

"Be still," commanded Uncle Daniel. "Will you wake him up?"

Then he, too, went toward the door. Aunt 'Liza put in her round face. They did not mean to be cruel. But little Sarah must be taught to know her place.

"Come, Sarah."

"I am going to stay here," said Sarah. She stood in the middle of the room, a wild, pathetic little figure.

"Come on," commanded Uncle Daniel.

"I am going to stay here," said Sarah.

At that moment Jacob Kalb returned. The poor twins had, despite their rage, fallen immediately asleep in Aunt Mena's carriage.

"Let her stay," he advised. "She will get pretty soon tired of it when she is afraid in the middle of the night."

"Ach, no!" cried Aunt Eliza. "She can't stay here."

But Uncle Daniel decided to take Jacob's advice.

"Come on, 'Lizie," he said.

For a moment after they had gone, Sarah stared about her. Afraid! Here in her own house with all the dear, familiar things of every day! There was nothing to be afraid of. She stood with blinking eyes, trying to remember what they had said about William; but her mind was a blank. She knew only one thing,—if she did not go upstairs, she should fall asleep where she stood.

She barred the doors and was about to put out the light, when she saw, above[Pg 23] the mantel-shelf, the one firearm which the Wenners possessed,—an old shot-gun, which William had broken years ago, shooting crows. Still half asleep, she lifted it down, and put out the light. Then, dragging it by the muzzle in a position which would have been extremely dangerous had the poor old thing been loaded or capable of shooting, she took her candle and went upstairs.

When Sarah woke at six o'clock the next morning, the faint gray of the winter sunrise was in the sky. She opened her eyes drowsily, trying to account for the heavy depression which seemed to weigh her down. Then, when her outstretched arms found no sturdy little figure beside her, and a glance across the room showed the smooth, unopened trundle-bed, she remembered suddenly all that had happened on that sad yesterday. Her father was gone, and Albert and the twins, and there was no telling how long she would be allowed to stay in the farmhouse. She realized how impossible it would be for a little girl—in the gray dawn Sarah felt very small and young—to hold out long against so determined a man as[Pg 25] Daniel Swartz. She turned her face deeper into the pillow.

Then, suddenly, a soft sound recalled her to herself. It was the whinnying of Dan and Bill, calling for their breakfast, already long overdue. And the cows must be fed and milked, and the chickens must have their warm mash. Sarah was upon her feet in an instant. She was not quite alone so long as these helpless creatures depended upon her.

An hour later, she drove out of the yard on her way to the creamery. With activity, ambition had returned; she began even to hope that her uncle might be persuaded to let her stay. The sun had risen clear and bright, and all the cheerfulness of Sarah's disposition responded to it.

She wondered, as she drove along the frozen roads, whether it would not be possible to add a third cow to her dairy. And she could keep more chickens. Her father had taught her how to look after them,—[Pg 26]their hens always laid better than Aunt Eliza's. And if the chickens did well, and if Ebert would put out the crops for her,—poor Sarah meant to go ahead just as though her uncle had not said that he would farm,—and if the children were allowed to come back, and then if William came home—She knew in the bottom of her heart that they were air castles, but she found them pleasant abiding-places.

The men, waiting in line at the creamery, called to her kindly, all but Jacob Kalb, whose wagon was third from the delivery door.

Henry Ebert was at that moment chirruping to his horse to move into place before the platform.

"Sarah!" he called. "Wait once. I move a little piece back, and you can come in first."

Jacob Kalb approved of no such chivalrous impulses.

"Those that come first should have first place," he growled. "I can't wait all day."

But the men only laughed. None of them liked Jacob Kalb.

Sarah swung Dan into line before the door. A week before, she would have called out,—

"blaff" being the Pennsylvania German word for bark, but now she sternly checked her poetic fancies. Sarah had made up her mind to be very wise and politic. But she could not repress a smile of satisfaction over her brilliant combination of Pennsylvania German and English.

Jacob saw the smile and watched her, scowling. It irritated him to see her there, businesslike and cheerful, and it did not give him any pleasure to hear a neighbor call to her that he would stop for her milk-can the next morning. Sarah shouted back her thanks.

Ebert consented willingly to put out the crops. He had a great admiration for smart little Sarah.

"Next week I begin to plough," he promised.

Then Sarah slapped the reins on Dan's back and was off. There was plenty to do at home: the house to put in order, several hens to set, and some baking to be done. As she drew near the farm, she became apprehensive. Suppose her Uncle Daniel should have taken possession while she was away! She had locked the door, but the fastenings of the windows were not very secure. And to whom, in such a case, should she go? Not to any of the farmers round about: they were poor and had many children.

She could not take Uncle Daniel's charity,—she knew that, no matter how hard she worked, he would still consider it charity,—and she could not live with Aunt Mena, who had the twins. She thought vaguely of going with her trouble to Miss Miflin. But Miss Miflin had no home.

There was no sign of any alien presence as she drove up the lane. The cat sat[Pg 29] comfortably on the doorstep, a sure sign that there were no strangers about. Sarah stopped thankfully to pat him before she fitted the key into the lock.

"You poor Tommy, where would you go if Sarah went away?"

Still talking to the cat, she pushed open the door. Then she stood still, as though she were turned to stone.

Within, all was confusion. She did not see that it was the sort of confusion which could be created in a few minutes and as quickly straightened out. Immediately in front of the door the old settle had been turned over on its stately back, and the chairs were piled high on the table in a sort of barricade.

Sarah's first thought was of thieves. Then she realized that she was looking straight into the barrel of a shot-gun.

It made no difference that it was the same broken gun which she had carried upstairs with her the night before, and that she[Pg 30] knew it would not shoot. She was terrified at first beyond the power of speech. She leaned, weak and faint, against the door-post, and presently demanded who was there.

Two voices answered her.

"Hands up!"

Then Sarah rushed forward.

"Ellen Louisa!" she cried. "Louisa Ellen!"

The twins had been carried to Aunt Mena's and put to bed without waking. Then Aunt Mena had sat down before the kitchen fire to explain to her husband why she had brought them home.

"Daniel, he says I shall take them. He takes the farm, and he will pay me each week a dollar for Ellie and Weezy. He has to, or I will not keep them. And I get my share of pop's and mom's things what Ellie had, too. They won't do these children no good. But I will not manage Ellie and Weezy like him. He is too cross. I will first tame them. But he is not cross to Albert. Now these[Pg 31] twins shall do for a few days what they want. They dare go to school this year and next yet, then they must stop."

In the morning Aunt Mena began her process of taming, which would undoubtedly have proved successful with persons more amenable than the twins. In the first place, she let them sleep as long as they liked. When Ellen Louisa woke, she saw by the century-old clock, ticking on the high chest of drawers, that it was seven o'clock. She nudged Louisa Ellen, who scrambled out of bed.

"We must hurry or we will be late to—" At that moment Louisa Ellen, instead of rolling out of a low trundle-bed, fell with a loud thump, from the high four-poster. She realized that they were not at home. Then upon them both dawned the recollection of the night before, and the weary days before that.

"P-pop, he wouldn't like it that we were here," said Louisa Ellen. "He said we should stay always by Sarah."

Ellen Louisa did not answer, but began to put on her shoes and stockings with lightning speed. The twins never wasted many words.

As soon as Aunt Mena heard them stirring about, she came to the foot of the steps.

"Wee-zy," she called. "El-lie! Breakfast."

"Our names—" began Ellen Louisa shrilly; then she was stopped by Louisa Ellen's hand on her mouth.

"Don't make her mad over us," advised Louisa Ellen. "She might pen us up."

"We will go to school," said Ellen Louisa. "Then we will go home to dinner. Pop wouldn't like it if we weren't in school."

But Aunt Mena did not approve.

"In a couple of days you shall go again in the school. But you are not going any more in the Spring Grove School. It is not any more your district."

"N-not to Miss Miflin!" gasped Ellen Louisa.

"No, you are no more in Miss Miflin's district."

"B-but—" Ellen Louisa felt her braid of black hair sharply tweaked. Louisa Ellen was a shade thinner than Ellen Louisa and a trifle quicker witted.

"You didn't have to tell Aunt Mena right out that we were going home," she said, when they had finished their breakfast. "Now come on."

The coast was, at that moment, perfectly clear. Aunt Mena was in the cellar getting the cream ready to churn, and Aunt Mena's husband was in a distant field, ploughing. The twins seized caps and shawls and fled. Ellen Louisa made for the high road.

"What have you for!" cried Louisa Ellen. "That way she will look for us. We go this way to the Spring Grove road. Come on."

Ten minutes later, when Aunt Mena came to the door, they were not in sight. Aunt Mena was not much troubled. She did not[Pg 34] know that Sarah had been allowed to stay in the farmhouse.

"Pooh! they will go to Daniel, and he will fetch them home, or I will fetch them home. It is all one."

And Aunt Mena went back to her work.

The twins had a ride in a farmer's cart, which brought them to the foot of the lane. Realizing that they were too late for school, they decided to go home until the afternoon session. Then Sarah would write a note of explanation to Miss Miflin. To the twins Sarah's notes were as all-powerful as Aladdin's lamp. To Miss Miflin they were sources of both mirth and grief. She laughed because they were so irresistibly funny, and then she almost cried because they reminded her of plans and hopes once dear to her heart, which had been ended forever by misunderstanding and resentment.

"Dear Teacher," Sarah wrote. "Please excuse the zwillings" (there were times in the[Pg 35] stress of hasty composition when English words eluded Sarah's grasp as they eluded Jacob Kalb's) "for being late. They cannot come now so early like always, while they must help a little in the morning.

Their father,

Sarah Wenner."

Sarah considered that the signature was a happy combination of the respect due to fathers and the sign of her stewardship of his affairs.

Sometimes Miss Miflin started to go to see little Sarah, who had been the best and brightest pupil she had ever had, but she never got quite to the house. She blamed herself for William's going away, and she thought that they too might blame her. So she turned back.

The twins had not been at all alarmed by the closed house. Sarah always drove to the creamery. They did not realize that Albert had been taken away, and supposed that he[Pg 36] had gone with her, since they were not there to look after him. Prying open the cellar door, which was fastened by a loose bar that could be moved from the outside, they were soon in the house. They were wild with delight over their escape.

"Let us get ready for Aunt Mena if she comes," proposed Louisa Ellen. "Let us built such a fort."

It was "such a fort" which had frightened Sarah. Now the twins flung themselves upon her. They had run off, they had come home, they were not going to school till afternoon, they—But where was Albert?

"He is by Uncle Daniel," answered Sarah slowly.

"Then we will fetch him." The twins made a dash for the door. But Sarah held them back.

"No," she said. "Uncle Daniel will keep Albert by him. And perhaps Aunt Mena will fetch you again, and perhaps Uncle Daniel will take the farm away from us,[Pg 37] and perhaps we cannot be any more together."

The twins were amazed and bewildered. Sarah's solemnity worried them more than the catalogue of evils.

"What shall we do?" they asked.

"You can learn your lessons and say them to me. And you can sew your patchwork and be quiet and smart."

All the rest of the morning, and all the afternoon, there was quiet such as the farmhouse had never known when a twin was within it and awake. Dinner was eaten almost in silence, and then Sarah, locking the door behind her, and with many long glances over the fields and road, went out to feed the stock.

She fancied that she saw a little face pressed to the kitchen window of the Swartz farmhouse, far away across the brown fields, but she could not be sure. Albert was so little, he had learned to be fond of Uncle Daniel, who was constantly giving him presents of[Pg 38] candy and peanuts; it would be easy enough, Sarah thought, for them to keep him there.

It was almost supper time, and the early dusk was falling, when the twins were ready to recite their lessons. It is safe to say that never, even in Pennsylvania Germandom, was there a class like this which Sarah held. Fortunately the twins were good arithmeticians, for Sarah could not have corrected their mistakes; she had been too long away from school for that. The twins never guessed that, when she insisted upon a careful explanation of each simple process, she was learning from them.

They had not heard as yet Miss Miflin's careful pronunciation of the words of the spelling lesson; so when Sarah said "walley" or "saw," they answered at once "v-a-l-l-e-y" or "t-h-a-w," never dreaming that Sarah's speech embodied all the mistakes which Miss Miflin tried to correct.

When it came to the geography lesson, Sarah shone. The twins had not had the[Pg 39] advantage of hearing their father and William speculate about strange and distant lands; they had a certain amount of book-knowledge, but no imagination to enliven it.

"How wide is the Amazon River at its mouth?" asked Sarah.

"Two hundred miles," answered the twins glibly.

"How wide is that?"

Louisa Ellen responded. To her a river was a line on a map. She would make this river wide enough even to suit Sarah.

"About as wide as the coal-bucket," answered Louisa Ellen.

At that moment, before Sarah had time to explain to Louisa Ellen the phenomenal dullness of her mind, the latch of the door was lifted softly and allowed to drop.

"It is Aunt Mena," said the twins together.

Sarah motioned them to the settle.

"Sit there till I tell you to get up," she[Pg 40] commanded. "I will go up to the window and look down."

The twins held each other's hands in fright. Was Jacob Kalb coming again to carry them out?

"Aunt Mena couldn't fetch us alone," said Ellen Louisa.

Then they started up in fright, realizing that Sarah was falling downstairs. She righted herself immediately, at the bottom, and rushed past them to fling wide the door.

A tiny little figure stood without.

"I sought I would come once home," said Albert. "So I runned off."

Speech suddenly became impossible, as Albert found himself almost smothered under a multitude of caresses. When they let him go, he drew a sticky package from his blouse.

"I brought some candy along for you," he said; whereupon he was almost smothered again.

Never had the old farmhouse known more happiness than filled it that night. Never was waffle-batter so light or appetites so good. Then, what games! Sarah was a teacher, book in hand,—that was her favorite. Then they were children lost in the woods, and Sarah was a bear,—that was the twins'.

No one but Sarah realized how strange it was that they should be playing there so contentedly. It seemed to her that a vast space of time divided this day from yesterday. It seemed almost as though her father had come back, or as though William might come in upon them. Little Sarah almost listened for his step.

Then, like a warning to dream no more, there came first an imperative lifting of the latch, then a loud knock on the door.

"What do you want?" asked Sarah.

"Albert is to come right aways home." That was Jacob Kalb.

"The twins are to come right out." That[Pg 42] was Aunt Mena. For the first time in thirty years Aunt Mena's butter had failed to "get," and she was angry and impatient. She had forgotten her gentle intention to "tame" the twins. "Come right aways out, or you will get a good whipping."

The twins looked critically at the strong wall between them and the enemy. It seemed a time when the dictates of wisdom might yield to those of personal satisfaction.

"We won't," said Louisa Ellen.

"Jacob Calf!" called Ellen Louisa.

"Go upstairs and take Albert," commanded Sarah. Then she turned to the door. "You can't have my children."

"I give you a last chance," said Aunt Mena. "I don't care for the dollar a week. Shall the twins have a good home, or shall they not have a good home?"

"You cannot have my children," said Sarah again, her heart pounding like a trip-hammer.

"Well, then," called Aunt Mena furiously, as she went away.

Jacob Kalb lingered. If Mena Illick refused to take the twins, Swartz might be compelled to leave them all there. Then Jacob could not have the house.

"You ought to be srashed!" he shouted to Sarah. "You are a bad girl. You put Albert out here."

Then Jacob began to pound on the door.

It was five minutes later when Sarah came upstairs. Her face was white and her hands shook. Yet she was laughing.

"Why don't you tell him if he don't go away you will shoot him with the gun?" demanded Louisa Ellen.

Sarah laughed hysterically.

"That was just what I did tell him," she said.

Stammering, frightened, shouting something to Aunt Mena which she did not understand, Jacob Kalb fled from the Wenner farmhouse across the fields toward the Swartzes'. He burst into the kitchen, where Aunt 'Liza was putting the supper on the table, like a wild man.

Aunt 'Liza was still explaining to her angry husband how Albert got away.

"He was here, and then he wasn't here," she said almost tearfully. "And nobody was here to go after him, and I didn't know what to do, and—and I believe perhaps she came after him."

Aunt 'Liza was willing to lay the blame of Albert's escape almost anywhere but where it belonged, on herself. Then she was fright[Pg 45]ened by the look of rage in Uncle Daniel's face.

"Did you see her here after Albert?"

"No, no, I didn't see her here after him. But I thought—"

"Thinking is now no good," answered Uncle Daniel. Then he got upon his feet. "There, they're coming. I can hear them."

Before he reached the door Jacob Kalb burst in.

"Sh—she will—she will sh-shoot me!" he cried wildly. "She was going for to fetch the shot-gun to shoot me!"

Aunt 'Liza threw herself against the door, shutting it almost in Aunt Mena's face.

"Where are you shot, Jacob?" she demanded.

"I am not yet shot," answered Jacob. "But I will be shot. I—" He felt suddenly his master's grip on his arm. "Ow! What is the matter?"

"Where is Albert?" asked Uncle Daniel. "She has no gun to shoot with. What are[Pg 46] you talking about? Where is Albert, I say?"

"She wouldn't give him to me," gasped Jacob. "They yelled at me, the zwillings yelled at me. They wouldn't give him to me. She is after me with a gun. She—" There was suddenly a loud pounding at the door. "I tell you she is after me. She—"

Uncle Daniel strode to the door, and flung it wide. He, at least, was not afraid of being shot.

"What do you mean?" he shouted. Then he saw that it was Aunt Mena who stood without.

"I mean that if Ellie and Weezy don't come along home with me to-night, they are not to come at all," said Aunt Mena hotly. "I cannot be running the whole time over the country for them."

"Ellie and Weezy," repeated her brother. "Are they not by you?"

"No, they ran early this morning off already."

"And Albert ran off," said Aunt 'Liza.[Pg 47] "I could not help it. I went a little while on the garret, and when I came back, he was gone. I cannot help it. I—Where are you then going, Daniel?"

Uncle Daniel cast a scornful glance at the two women who could not keep three children, one a mere baby, from running away, and at the fright-stricken Jacob; then, regardless of the hot supper, about which he was usually so particular, he stalked out.

"Put Albert's high chair to the table," he had ordered briefly.

In fifteen minutes he was back. Aunt 'Liza had not learned much tact in all her twenty years of wedded life, or she would not have begun to question him before he was inside the door.

"Where is then Albert?" she asked.

Swartz did not deign to answer. With a heavy frown, he sat down at the table and began to eat.

"Didn't she give him to you?" demanded Aunt Mena, aghast.

"Be still," said Uncle Daniel shortly.

"Did she get after you with the gun?" asked Jacob Kalb. He had just finished giving the women an account of his adventure. He said that he saw the gun-barrel when he looked in the keyhole.

"Then she didn't come out after you?" said Aunt Mena.

"No, but she was coming," insisted Jacob. "I am going to have the law on her, that is what I am going to do. I will have her put in jail. I will have her—"

"Be quiet," said Uncle Daniel to him, also.

Aunt Mena rose to go.

"I don't come again after Ellie and Weezy, remember," she said. "If you fetch them over, perhaps I will take them back. Just tame Sarah a little—" She forgot that her own efforts at taming had not been very successful. "And then put somebody in the house, so she cannot get back. That will settle it."

"Be quiet," said Uncle Daniel again.

"I will have the law on her," muttered Jacob Kalb. Every few minutes he rubbed his leg, as though he were feeling for a gunshot wound.

It was ten minutes before Uncle Daniel laid down his knife and fork and pushed back his plate. Either reflection or the good supper had soothed him. The angry flush was dying out of his face.

"Well, what are you going to do?" asked Aunt 'Liza.

"I have it fixed," he answered complacently.

"Are you going to put her out of the house?" asked Aunt 'Liza.

"Are you going to have the law on her?" asked Jacob Kalb.

"Yes," answered Uncle Daniel. "I am going to put her out of the house, and I am going to have the law on her. I am going to do both of those things. I am going to be the guardian of her and of Ellie and Weezy and Albert."

"Guardian?" repeated Aunt Eliza.

"Yes, guardian. Those children must have a guardian, and I am the one to be it. But I must have papers. You cannot be a guardian unless you have the papers from the court. I will go to-morrow to town and get papers. Everything shall be fixed right."

Aunt Eliza was alarmed.

"But it will cost money!" she cried.

"Nothing of the kind," answered Uncle Daniel. "It is a kindness I do these children. Shall I pay for it, yet?"

"And then Sarah will have to come here?"

"Sarah will have to do what I say she shall do," answered Uncle Daniel. "And Albert and Ellie and Weezy. Everybody will have to do what I say they shall do."

Jacob Kalb gazed at him with admiration and delight. Daniel Swartz always found some way of accomplishing what he wished. It was true that he had not succeeded in adopting William Wenner. But he had[Pg 51] succeeded in punishing William, only Jacob knew how well.

If it had not been for that knowledge, Jacob Kalb would not have been looking forward with such delight to living in the Wenner house, instead of walking back and forth each night and morning to the house of his wife's father, three miles away, where he lived now.

He rose to go home, not at all certain that Sarah was not waiting for him outside the door with her shot-gun.

"In the morning you are to go early into town with me," said Uncle Daniel. "At six o'clock we will start."

"You ought to bring a little hat for Albert," said Aunt 'Liza when the door was closed.

"No, sir," answered her husband. "I bring him perhaps a little candy or peanuts, but no more. Not till he is here to stay. I brought William sometimes presents, suits, I brought him, and a little cap, and shoes,[Pg 52] and once such a little velocipede, and what did I get? No, sir. When Albert is here to stay, then I get him some things."

When supper was over, he sat down before the fire. He seemed to be brooding over William's ingratitude.

"Shoes, I bought him, and candy. And what did I get for it?"

Accompanied by Jacob Kalb, he reached the county seat long before the earliest lawyer was astir. It did not occur to him that there was a difference in lawyers or lawyers' prices. He had heard of Alexander Weaver, so he went to him.

"This is a fine way," he said to Jacob Kalb, when they had waited for half an hour. "I'd like to know how my work would get done if I fooled round this way in the early morning; that is what I would like to know. If he don't soon come, I go."

Then the door of Mr. Weaver's private office opened, and Mr. Weaver himself invited them in. He was a dear-eyed, middle-[Pg 53]aged man, so busy that he often offended his clients by his curtness. He gave Daniel and Jacob chairs where he could watch their faces. He imagined from their appearance that they had come about some country quarrel. And country fees were hard to collect.

Uncle Daniel began slowly to state his cause.

"My brother-in-law, he is dead," he announced.

"Yes?" The lawyer crossed his knees nervously.

"And my sister, she is dead."

"Yes?"

"And it is nobody to look after their things."

"Any children?"

"Yes."

"Minors?" asked the lawyer.

"No, children."

"Well, I mean any under age, under twenty-one?"

"Yes, it is a couple. Sarah—" Uncle Daniel counted them off on his fingers. The lawyer's abrupt speech startled him, and he was afraid he might forget.

"How old?"

"She is fifteen, but she is little. She could not run a farm."

"But she thinks she can do everything," put in Jacob Kalb. "She got after me with a gun."

The lawyer smiled. He did not take kindly to Jacob Kalb, and it was amusing to think of a fifteen-year-old girl "getting after" him with a gun.

"Any others?"

"Yes, it is a couple of twins, Weezy and Ellie."

"How old?"

"About ten. But they are—"

"Any others?"

"Albert. He is four. He—"

"And you want to be appointed guardian of these minor children of your sister?"

"Yes, sir." Uncle Daniel blinked. He could not understand the phenomenal quickness of this man's mind. For the next few minutes he continued to blink rapidly.

"Your name? Your occupation? The value of the property of these minors?" Question followed question so fast that Uncle Daniel could hardly think.

"You will have to sign a bond for the amount of the property, you know. Your application will be sent to the Orphans' Court. Come back in a month. The retaining fee will be twenty-five dollars."

Then Uncle Daniel got his breath.

"Twenty-five dollars! Twenty-five dollars for what?"

"For making application to the Orphans' Court. Wasn't that what you wanted me to do?"

"Y-yes, b-but twenty-five dollars for writing out a couple of papers! Twenty—"

The lawyer swung round to his desk. Daniel realized suddenly that the lawyer did[Pg 56] not care whether he got the case or not. He became all the more anxious to have this remarkable man continue it. Sarah might in some way make trouble.

"All right," he stammered. "We will come in a month back again. We—"

The lawyer flung him a crumb of comfort.

"You will be reimbursed, of course, from the estate," he said; and Uncle Daniel's face brightened.

He did not realize that in thus putting himself into the hands of the law, he would place over his own actions a guardian to whom he should some day have to give an account of his stewardship. In Uncle Daniel's mind, he was to be, after the month was up, supreme arbiter of the fates of the Wenners,—Sarah and Albert and the twins alike, and of their property. He meant to be honest. Even though he did take the farm, he would support them, Sarah and Albert at his own home, and the twins at Aunt Mena's.[Pg 57] Only, if Sarah did not behave, she would have to go out to work.

There was triumph in every motion of Uncle Daniel's broad, heavy shoulders, as he went down the steps. He had began to think that education was a good thing for lawyers, also. It must be pleasant to get twenty-five dollars for writing a few words.

At a store at the corner, he bought five cents' worth of peanuts and a small bag of candy. Then they started home, drawing rein first at the Ebert farm. Ebert appeared in response to a loud hulloa. He wondered why Swartz was stopping at his gate.

"When will you begin to plough for the little one?" Uncle Daniel asked pleasantly.

"To-morrow morning."

"Well, you needn't plough at all," said Uncle Daniel. "I am to be guardian, and I will plough."

When they reached the lane which led to the Wenner house, they saw Albert and the twins playing in the yard. Swartz pulled in[Pg 58] the horse with a jerk, then he jumped down with the little bags in his hand.

"Tell 'Lizie that Albert will be home for supper," he said.

This time he did not stride up to the door and demand Albert. Instead he stole down the lane to the back of the house. He did not mean to take any actively offensive measures till the end of the month.

Sarah was not able to tell afterwards how Albert got away. She had kept the children close beside her all the morning, and it was not until afternoon that she yielded to their pleadings to be allowed to go out of doors to play. Then she sat down at the window with some sewing in her hands, in order that she might watch them.

She had not moved until the sudden hissing of steam warned her that the water in the kettle was boiling over. It had not taken her a minute to move it to the back part of the stove, but in that instant Albert was gone. She could see them crossing the fields,[Pg 59] Albert in his uncle's arms. The twins ran frantically behind them, and Sarah hurried to the door.

"He coaxed him away with candy," wailed Louisa Ellen when they ran back. "But Albert said he was coming home for supper."

That night there were no games. The doors were barred early, the supper eaten silently. Then Sarah got pen and paper and sat down beside the lamp. She would make a last appeal to William. Perhaps, though all the other letters had failed, this might reach him, and reaching him, might touch his heart.

It would have taken Sarah all night and all the next day to say all that was in her mind. But the task of composition was difficult and the letter was short. It read:—

Dear Brother,—My Uncle Daniel is after us. He fetched Albert again. Jacob Kalb wants to live here. The twins will not[Pg 60] stay by Aunt Mena. I am doing the best I can. I wish you would come home. Uncle Daniel will not have it that the twins and Albert live in their right home. We are well and hope you are the same.

Resp. yours,

Sarah Wenner.P.S. I chased Jacob Kalb off with the gun, but I fear me that perhaps he will come again.

It was not a neat production, Sarah realized that. She tried to wipe off a teardrop which fell upon it, and made a tremendous blot. And William had always been so particular about the way she wrote. It did not occur to her that, to the heart of an affectionate brother, the pathetic blot would be more eloquent than pages of pleading.

She addressed the letter to Seattle, then, waking the twins, who had gone to sleep on the settle, she sent them to bed.

Ah, that old settle, how many times it had[Pg 61] held them! What would Uncle Daniel have done with that? He and Aunt Mena had settles of their own. Would he have left it there for Jacob Calf? And the dear, battered furniture, the high chair which had held them all, from William down to Albert,—would he have sold them? It would be like killing a live creature to break up that home. Sarah gave up her own dreams cheerfully. She thought no more of the "Normal." If they could only stay together, she would ask no more of fate.

Miss Miflin wondered day after day why the Wenner twins did not come to school. She knew that their father had died,—that would account for three or four days, but why had they not come back after the funeral?

It was true that their absence made Miss Miflin's life much easier. They were not only very active themselves, but they were able to incite the best-behaved of schools to mischief. When Miss Miflin heard confusion behind her as she put a problem on the board, she needed only to call out, "Ellen Louisa!" and then "Louisa Ellen!" and the noise ceased.

When they were approached in private, the twins were as shy as rabbits. They stood[Pg 63] twisting their aprons and looking at each other as though Miss Miflin were an ogress. There seemed to be in them the same strange quality that Miss Miflin had discovered in William and Sarah,—a certain standing on guard. It had prevented Miss Miflin from writing to William to try to straighten out the miserable tangle which they had made of their friendship; it made her think of Sarah as a rather reserved young woman, instead of a lonely little girl. It made her hesitate even to offer her sympathy now that Sarah's father was dead. She was not a Pennsylvania German, and it seemed to her that they did not thoroughly trust her.

She was always prepared for the unexpected in the twins' behavior; but when, one morning late in March, they appeared at the school-door carrying an old shot-gun, the same which had done such deadly execution upon the frightened Jacob Kalb, she said aloud, "Well, what next!" Then she went down the aisle to speak to them.

"I am glad to see you back, Ellen Louisa and Louisa Ellen." She had long since discovered that any attempt to abbreviate the names of the twins was not received with favor.

"Yes, ma'am," the twins answered politely. They could not have told why they were so mischievous; it was a Topsy-like obsession which they could not control. They both blindly adored Miss Miflin.

"And why do you come to school armed as though you were going to war?"

The twins giggled. The idea of going to war pleased them.

"So nobody shall carry us off," answered Louisa Ellen.

"Is anybody likely to carry you off?" asked Miss Miflin, smiling. She had seen at once that the gun was useless as a weapon.

"Yes, ma'am," answered Ellen Louisa.

Miss Miflin smiled again. It was time to begin school, and she supposed it was all one of the twins' tricks.

"Put the gun in the corner and go to your seats," she said.

An hour later Miss Miflin heard a stir in the back of the room.

"Ellen—" she began. Then she followed the children's gaze toward the window.

Sarah Wenner stood there, looking in, as though she only meant to assure herself of the twins' presence. But what a changed, wild-eyed Sarah! Miss Miflin dropped chalk and ruler and went to the door.

"Sarah!" she called.

Sarah came hurriedly from the other side of the schoolhouse.

"I didn't mean anything," she explained. "I wanted just to see if Ellen Louisa and Louisa Ellen were in school, that was all."

She did not say that the twins had added another frightened hour to those which had made her face so white. They had slipped away while she went to the barn.

"Didn't you want them to come to school?" asked Miss Miflin.

"Ach, yes!" cried Sarah. "I want them to go every day in the school."

Belief and the sight of Miss Miflin were already patting some color into her cheeks.

"Are you well, Sarah?" asked Miss Miflin.

"Ach, yes!" answered Sarah. "But now I must go home. You must excuse me while I disturbed the school for you. Here is lunch for Ellen Louisa and Louisa Ellen, then they need not come all the way home for dinner. Will you—will you watch them, so they do not go off to play at recess? Just give it to them if they are not good. I will then walk a piece way along to meet them when they come home from school."

Sarah was gone before Miss Miflin could ask any more questions. She saw her look back as she tramped along the muddy road, then she vanished behind a hedge of alders. Miss Miflin was puzzled and disturbed.

It was almost an hour before Sarah reached the Eberts' door. She was inexpressibly tired, and the roads were deep with mud. She had[Pg 67] not been sleeping well at night. Uncle Daniel had made no farther move, but she felt that the delay was only a truce. She had seen nothing of Albert, though it had been several weeks since his uncle had carried him away. They were guarding him well.

Ebert had not come to plough, and Sarah was worried. She had looked for him day after day, and now she feared that he was sick.

She could get no answer when she knocked at the door. The house was closed, yet in the field near by the earth had been turned up that morning. Why did they not answer? She could not know that Mrs. Ebert watched her from an upper window, with tears in her eyes.

"I wasn't going to tell her that you wouldn't plough for her," she said to her husband at noon.

"Well, I guess I am not going to plough and then let Swartz have the benefit," answered Ebert.

Troubled and anxious, Sarah went on to[Pg 68]ward home. As she turned to go up the lane she saw a man at work in the north field. Ah, Ebert had begun! Then her flying feet halted. The horses were Uncle Daniel's grays, the man was Jacob Kalb. Sarah cried out as though she had been struck.

Then she saw that the fence was down. It was not a worm-fence, which could be put up again in a little while, but a stout "post and rail." The posts had been taken out. The two fields formed together a great slope which ran from the Wenners' garden to the edge of the Swartzes' yard.

Sarah gathered her shawl a little closer about her and ran on.

"Get out, Jacob Kalb!" she called.

For a minute Jacob looked as though he meant to run. He had protested against coming to plough so near the house, for fear that Sarah might "do him something." Now he saw that Sarah did not carry a gun. He mocked her rudely.

"Get out, Sarah Wenner!"

"I tell you, you shall go away, Jacob Kalb," she shouted. "This is not your land."

Jacob laughed. "You will have to go pretty soon away," he said.

Sarah could eat no dinner, but sat at the window watching. Already the boundary between the two farms was fast disappearing. How would they be able ever to find it again? What would her mother and father have said? What would William say when he came home?

When he came home. It was growing to be if he came home in Sarah's mind. Anxiety was doing its work.

She remembered things which she had heard as a child and forgotten,—her mother's sharp criticism of Daniel Swartz's meanness, her father's good-natured laughter. She did not know how easily that same dear, thoughtless father might have made it impossible for his brother-in-law to interfere with them. He might easily have provided[Pg 70] another guardian for his children. He had meant to,—that much must be said for him,—but he was a procrastinator, and at the end there had been no time.

Sarah could not go now to meet the twins when they came from school; she did not dare to leave the house. Jacob Kalb might take possession while she was away.

The afternoon passed slowly. Toward evening, there was a late flurry of snow. And the twins did not come. Sarah ran part way down the lane,—they were not yet in sight,—then she went to the barn to milk, her ears straining to hear any unfriendly sound. It soothed and comforted her to be with the friendly beasts which she loved. Both "Mooley" and "Curly" had been born on the place, they were part of the living fibre of the homestead.

It was fortunate that the twins called to Sarah before they ran up to the door of the barn, for another shock was more than Sarah could have borne at that moment. The[Pg 71] twins' voices trembled with some exciting news.

"She came along home with us," said Louisa Ellen.

"She carried the gun for us," said Ellen Louisa.

"She is waiting at the front door."

"Who is waiting at the front door?" asked Sarah. Then she added fearfully, "Aunt Mena?"

"No, teacher."

"Teacher!" repeated Sarah. "Wh-what did she come for? Have you then not been smart?"

"For to see us," said Louisa Ellen impatiently. "She is coming for company. She—"

Sarah had crossed the lane, a milk-pail in either hand.

"Come," she called, in a voice which was meant to be a whisper, but which Miss Miflin, waiting on the broad doorstep, heard clearly. "Hurry yourselves, and fix a little up. Perhaps—" Sarah could scarcely speak for[Pg 72] excitement. "Perhaps she will stay for supper."

A moment later, she opened the front door. Her black hair was brushed back a little more closely to her head, her face shone, the great white apron which she had hastily put on over her gingham one was much longer than her dress, and from the back her gray-stockinged ankles could be seen outlined against it in pathetic thinness.

"Come in, teacher," she begged shyly. "Come once into the room [parlor] and I will hurry make a fire."

"Oh no," said Miss Miflin. "I'll come back to the kitchen with you. I didn't come to be company. I came to bring the twins home, and the gun."

"The gun!" repeated Sarah. "Did they then take the gun along? Come in. It doesn't look here so good like always. I—I didn't work this afternoon so very much. I—"

And Sarah ushered Miss Miflin into the immaculate kitchen.

Miss Miflin breathed a sigh of relief. The chill of the house had struck into her heart. Could William have lived here? Then she saw the glow of the fire, the bright rag carpet, the blooming geraniums in the window. This looked like William. Miss Miflin put out her hand and drew Ellen Louisa, in a clean white apron, to her side. She, too, was William's.

"I wonder whether you would let me stay for supper?" she asked.

The glow in Sarah's face answered her.

"If it is you good enough," answered Sarah humbly.

"Good enough!" laughed Miss Miflin. She pulled off her over-shoes and slipped out of her coat. She had no home of her own, and had been boarding at a country hotel for three years. "But you children don't stay here alone at night!"

"Yes," said Sarah.

"But aren't you afraid?"

"Ach, no! Nobody would do us anything,"[Pg 74] stammered Sarah. She could not tell this stranger any of their troubles.

"But haven't you a little brother?" Miss Miflin looked round the kitchen.

"Yes, ma'am," answered Sarah. She suddenly put out her hand, and laid it on Louisa Ellen's shoulder, and Louisa Ellen closed her lips as though she had meant to speak, but had changed her mind. "Yes, Albert. He is now by my uncle."

"And don't any of your uncle's people come to stay with you at night?"

"Ach, no!" answered Sarah. Suddenly she felt her voice give way. There was something in Miss Miflin's brown, astonished eyes which made her feel that she might cry. But that would never do. "T-take a ch-chair. I-I guess you had to laugh at how the twins learned their lessons. I taught them while they were at home."

"They learned them well," replied Miss Miflin. "Now I am going to help get supper."

The twins could scarcely believe their eyes. It was as though a fairy had come to the farmhouse, a dear, capable fairy, who could dry dishes and cut bread, and magically change tired, care-worn Sarah into the gay, cheerful Sarah of old. It was almost nine o'clock when Ellen Louisa turned from the window, against which she had been flattening her nose.

"It's snowing again," she announced.

Miss Miflin looked up in dismay. She had forgotten how fast the time was passing. Sarah never knew that, summoned by her stories and her love, it seemed to Miss Miflin that William was there with them.

"I shall have to go at once," she cried. "I had no idea it was so late."

Sarah clasped her hands together.

"You are welcome to stay here," she said. "If it is you good enough, you are welcome to stay here!"

Miss Miflin crossed the room to look out of the window.

"I guess I'll have to. Then I can take the twins with me to school in the morning and they won't need the gun. And why do they want to run away, where some one might pick them up? And who wants to pick them up?"

It was a second before Sarah answered. Suppose she should tell Miss Miflin about Uncle Daniel, and about Jacob Kalb, and all her anxieties and fears? But, no, it would never do. It made her ashamed to think of Uncle Daniel. She did not believe William would like her to tell. She frowned again at Louisa Ellen.

"Ach, they are a little wild," she explained. "They like their school, but they are a little wild."

By this time Miss Miflin had a delighted and sleepy twin on each side of her on the settle.

"But they are not going to be wild any more," she said.

Sarah was asleep that night almost before her head touched the pillow. It seemed to[Pg 77] her that peace had descended upon her heart, and hopes for a better day.

It was midnight when she suddenly awoke. Miss Miflin was standing beside the bed.

"Sarah! Sarah, dear, wake up. Your uncle is here and wants you."

Sarah tried to open her drowsy eyes.

"He can't have them," she said, bewildered. "Tell him he must go away."

"But listen, Sarah. He says Albert is sick and they want you."

Sarah sat up at once.

"He is waiting for you at the door. Come, I'll help you with your clothes. Don't come back to-night. I'll get breakfast for the twins. No, Sarah, the other shoe. No, you must put on all your warm clothes. There! Now, I'll come downstairs with you."

Sarah was too dazed with fright and sleep to speak. Miss Miflin was shocked at the anguish in her face. She put out her arms, and for one blessed moment Sarah felt the close pressure of sympathy and love.

"There, Sarah, dear! I'll look after the twins and the house, and to-morrow you must tell me everything, Sarah."

Miss Miflin opened the door, and told Uncle Daniel who she was, and Sarah went out. With confidence which touched even Uncle Daniel himself, she put her hand in his.

"Come, let us hurry," she whispered.

Sarah never forgot the wet, cold walk across the fields. The stars were out, and there was promise of a clear day, but the melted snow made the soil wet and muddy, and the air was damp. Uncle Daniel strode on, without remembering to moderate his long steps, and Sarah almost ran by his side.

She was wide awake now, the cool air on her face banished all drowsiness of body, and Albert's danger roused every faculty of her mind.

"How long was he sick already?" she asked.

"Since this morning. But he has been for a couple of days not so good."

"Where is he sick?"

"He won't eat nothing, and—and he[Pg 80] don't know us. He—he—" Uncle Daniel's voice shook. He had had a hard day. He was desperately frightened about Albert, and Aunt 'Liza had not made him more comfortable by insisting that it was a punishment for wanting his sister's farm.

"He will know me," answered Sarah with conviction. Then she began to run up the lane toward the house. She could see a light in an upstairs room, and Aunt Eliza's face was already peering anxiously out of the kitchen door.

"Albert is worse," she called. "He is talking all the time."

Sarah pushed past her into the kitchen. She had not been in the house since she was a little girl,—so entirely apart had been the lives of the two families,—but she knew the way to the stairway door. One after another the natural ills of childhood came to her mind. Albert and the twins had had chickenpox and measles and whooping-cough and mumps, and she had nursed them all. She[Pg 81] thought of the dreaded scarlet fever and diphtheria. But there was none in the neighborhood.

She hurried up the stairway, as there floated down a tiny, querulous voice,—

"I want my Sarah! I want my Sarah!"

Albert lay deep in the great feather-bed, his cheeks a flaming crimson, his arms tossing restlessly. Even when Sarah bent over him, he did not know her, but kept on with his restless crying. She put her hand on his hot forehead, she opened the collar of his night-gown.

When Aunt Eliza and Uncle Daniel came into the room, she turned upon them a look of such anguish that Aunt 'Liza began to cry, and Uncle Daniel sat down weakly in a chair.

"Is it the smallpox?" asked Aunt 'Liza fearfully.

Sarah did not answer. She looked at Albert once more. Long before, when her mother was living, the twins had found the[Pg 82] Christmas candy, and had eaten it all in a day. Then the twins had had a sorry time. They had looked just like this.

"What did you give Albert to eat?" she demanded.

"Ach! bread and meat and potatoes and pie, like always, and—"

"And what?" insisted Sarah.

"And a few crullers."

"And what yet?"

"And a little candy."

"How much candy?"

"Ach, such a little bag full."

"And what yet?"

"A few peanuts," answered Uncle Daniel doggedly.

"Get me warm water and mustard," commanded Sarah.

"C-can you make him well, Sarah?" faltered Aunt 'Liza. But she did not stop to hear the answer. At that moment she did not even feel the humiliation of having to obey fifteen-year-old Sarah.

In less than an hour, a watcher might have seen the lights in the Swartz farmhouse go out, one by one. Albert was asleep long before that, the flush faded from his cheek, the fever gone, a faint smile upon the little face on Sarah's arm. It would have been hard to tell which slept more soundly, doctor or patient.

In the next room Daniel Swartz lay wide awake. These weeks of Albert's stay with them had not been easy. It was not entirely pie and cake and candy which had made Albert sick; it was a disease which no heroic measures could cure, homesickness, and Uncle Daniel knew it.

"I never saw such a young one," he said angrily. "I was never so very for my brothers and sisters when I was little."

"Will you let him go home?" asked Aunt 'Liza timidly. The last weeks had worn more heavily upon her than upon her husband, since she had to watch all day long that white, woe-begone little face.

"Let him go home!" repeated Swartz. "When I am to be guardian to-morrow! I guess not. To-morrow Sarah has to come here. That will cure him."

It was long after daybreak when Sarah woke. Albert slept quietly beside her, and it was not likely that he would wake for several hours. She dressed hurriedly and went downstairs.

There she found Aunt Liza washing dishes and Uncle Daniel moving impatiently about, dressed in his best clothes.

"I didn't go yet to town, because I want to talk to you a little, Sarah," he began. "Sit down once and Aunt 'Lizie will give you your breakfast."

"But I must go home," objected Sarah. "Albert will be all right, only he must not have anything to eat yet awhile, only milk to drink. And he mustn't have candy, or he will get just so sick for you again. He is too little to have so much candy."

"But you stay here now and take care of[Pg 85] him," invited Uncle Daniel pleasantly. Now that he had everything in his hands he was prepared to be thoroughly amiable.

"I can come back," replied Sarah. His good humor frightened her, and she moved a little closer to the door. "But first I must go and milk. It is already late to milk."

"Jacob Kalb's wife went down this long time to milk," put in Aunt 'Liza.

"Jacob Kalb's wife!" repeated Sarah.

"Yes."

"Well, I'll go down and she can go home," said Sarah. "I—I don't need Jacob Kalb's wife to help. Then I can come back to see Albert."

She remembered afterwards that Aunt 'Liza had begun to speak, and that she had been sharply checked by Uncle Daniel. But she did not wait to hear. Jacob Kalb's wife was only a shade less disagreeable than Jacob himself. She could not bear to think of her touching her milk-pans or going into the[Pg 86] spring-house or kitchen. She ran as swiftly as she could down across the fields.

When she reached the kitchen door, she was faint with exhaustion. At first everything was black before her. Then she saw Jacob Kalb's wife standing by the stove. She was a large, fair-haired woman, with strong, bare arms. She had just lifted a pie from the oven and stood with it still in her hands, looking at little Sarah.

"I—I—you needn't bake for me," said Sarah when she could get her breath. "I am much obliged that you did the milking, but you need not bake for me."

"I am baking for myself," answered Mrs. Kalb stolidly.

"Well, you needn't bake here," cried Sarah.

Suddenly there came a rush of comprehension. It seemed for an instant as though she could neither breathe nor think. Her uncle had made Albert sick, he had sent for her to cure him, and then he had sent this woman[Pg 87] down here to take possession. She moved a step closer.

"Go out of my kitchen," she commanded thickly. "This is my kitchen, it isn't yours. These are my things, they are not yours. They are not my uncle's. He had no right to send you here. You could be arrested for it. It is stealing. Get out of my kitchen."

Suddenly everything seemed to grow black once more, and Sarah reeled. The woman came toward her.

"Are you sick? You better sit down once. It isn't my fault that I have to live here. If I don't live here, somebody else will. Let me take off your shawl for you."

"Ach, no!" cried little Sarah. "Don't touch me! Don't touch me!"

"I guess I won't do you anything if I touch you," answered the woman, the kindness in her voice changing to irritation. "Well, what in the world—"

Sarah had gone, leaving the door open behind her. Mrs. Kalb watched her run down[Pg 88] the lane, stopping occasionally to gasp for breath.

"Let her go and talk to Swartz," muttered Mrs. Kalb to herself. Then she went back to her work.

Sarah did not turn to go across the fields to the Swartz house, but went on out to the high-road. There she stood, looking about her, bewildered.

The blow had fallen at last. She had expected it hourly, but she had not foreseen such heartache as this. She had no home, and the children had no home, and William, if he came back, would have no home. The children might grow accustomed to life at Aunt Mena's and Uncle Daniel's,—she knew nothing then of Albert's homesickness,—but it would not be home. They would grow away from one another, they would not be like the children of one family.

She could not cry, she was too wretched for tears, she could only stand there in the road in the sunshine, trying to decide where[Pg 89] she should go. Then suddenly there came to her the touch of Miss Miflin's arms and the sound of Miss Miflin's voice.

"To-morrow, you must tell me everything."

She did not stop to listen to another voice, which told her that Miss Miflin was a stranger who could not really care, and who could not help. She started away, not running now,—she was too tired for that,—but walking as fast as she could, toward the Spring Grove Schoolhouse.

Recess had just begun, and the children, all but the twins, who had been granted the treasured privilege of cleaning the blackboards, were in the playground. They looked up curiously as Sarah went by. The Wenners had always been clannish. Even the twins were happier playing by themselves than with the other children.

Miss Miflin was shocked at the sight of Sarah's face. She had not worried about her, because the woman who had come to milk had said that Albert was better, and that[Pg 90] Sarah was still asleep. She had made up her mind to go back to the Wenners' that night. Perhaps if there were a grown person in the house Sarah would rest, and thus lose some of the weariness which showed so plainly in her eyes.

Now in addition to the weariness, there was distress such as Miss Miflin had never seen on the face of a young person. She went down the aisle to meet her.

"Well, Sarah," she began. Then she put out both her arms. "Why, you poor little girl! What is the matter?"

"Jacob Kalb is living in our house," said Sarah hoarsely. "We have no home any more. The twins must go to Aunt Mena, and Albert to Uncle Daniel. We have no home any more. He took it away from us. It is not right."

Miss Miflin helped Sarah to her own chair. Then she took the county paper from her desk.

"Sarah, I saw something about you and[Pg 91] the children in the paper last week. Don't you know your uncle is to be your guardian?"

"Guardian?" repeated Sarah.

"Yes, here it is. 'Daniel Swartz, of Spring Grove township, has applied to be appointed guardian of Sarah, Ellen Louisa, Louisa Ellen, and Albert Wenner, minor children of Henry Wenner, deceased.' Oh, Sarah, that means you will have to do as he says!"

"We would have to do as he says whether he was guardian or not," said Sarah dully. "He wants to take the farm. He has already taken the fence down. It is nothing to be done." Then she burst into tears. "If they would only give me a chance once! If they would let me try, I could show them what I could do. I know how the crops should be, and Ebert would work for the half, now like always. It would be just like when my pop was alive. Or if Uncle Daniel would farm and give us the half, like Ebert, so we could[Pg 92] get along. Then we could stay together. But now we have nothing. If William comes home, he won't have any place to go. He won't—"

"Listen a minute, Sarah!" said Miss Miflin. Then she did not go on at once, but turned over the paper with hands which trembled.

"Who makes him guardian?" asked Sarah.

"The judge," replied Miss Miflin absently.

"If I only could—"

"Wait a minute," said Miss Miflin again. "It may not have been decided yet. Perhaps if we went in, they would let us talk. Perhaps—"

Her hand went out suddenly to the bell-rope.