The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Maréchale (Catherine Booth-Clibborn)

Title: The Maréchale (Catherine Booth-Clibborn)

Creator: James Strahan

Release date: November 3, 2016 [eBook #53446]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

THE MARÉCHALE

(CATHERINE BOOTH-CLIBBORN)

BY

JAMES STRAHAN

AUTHOR OF "HEBREW IDEALS," "THE BOOK OF JOB," ETC.

HODDER & STOUGHTON

NEW YORK

GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY

COPYRIGHT, 1914, BY

GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY

The right of translation is reserved

Dedicated

WITH REVERENCE AND AFFECTION TO

THÉODORE MONOD

WHO TAUGHT US TO SAY TO OUR DIVINE MASTER

"NONE OF SELF AND ALL OF THEE"

PREFACE

This book is the unexpected result of a brief visit which the Maréchale paid her daughter and the writer in the spring of this year. She was daily persuaded, not so much to talk of the past, as to live parts of her life over again, for in her case the telling of a story is the enacting of a drama. At a meal-time she rarely keeps her seat, though she is apparently unconscious of leaving it and surprised that she requires to return to it. She begins to describe an incident, to recall a conversation, to sketch a character, and straightway she is suiting the word to the action, the action to the word, holding the mirror up to nature, using her brilliant dramatic gift, which is as natural to her as singing is to birds, to call up faces, to bring back voices, to restore scenes, which are all, whether grave or gay, summoned out of a dead past that has suddenly, as by the wave of a magician's wand, become once more alive.

One day I said to her, "Have you never thought of giving all this to the world?" She answered, "I am often asked to do so, and some day I may." Soon after she surprised me by saying, "I have come to the conclusion that something ought to be written now, and you must write it."

A mass of materials in English, French and German—reports, letters, diaries, magazines, and other documents—has therefore been put at my disposal. I have not used a tithe of what I have received, and much of what is left is as good as what has been taken. More will ere long, I doubt not, see the light. One of my best sources of information has been the Maréchale's own phenomenal memory, which I have tested times without number, and found invariably accurate, except in dates. Events are apt to be associated in her mind not so much with years as with homes and children, which are much more interesting.

With regard to the subject of the fourteenth chapter, the Maréchale would have preferred not to break the silence which she has maintained for a number of years, but after reading her letters and diaries I have urged her to let a brief statement be published, first because I feel that she owes something to her old comrades in the fight, and second for the sake of her own and her family's future work. Members of the family who have been consulted, as well as other friends, desire this even more strongly than the writer does.

This book consists of a few sections from a life which, like Mrs. Browning's pomegranate, "shows within a heart blood-tinctured." To a heart of love add a spirit of fire, and you have the Maréchale. Blood and fire—that is what she was at the beginning, and that is what she will be to the end. One has often heard her say that she has never been more in her element than when, on entering some town, she has found herself confronted, in a theater or casino, by "all the devils of the place." She is happy whenever "Jesus is going to have a chance for a night." In the natural course of things her greatest battles are still before her. England has need of her, France perhaps still greater need. May it be long before the Maréchale reaches her last campaign! Meanwhile the old battle-cry, En Avant!

The subject of this sketch—written during a brief respite from other work—is at present far away, but I know that what she desires to give to the world is a sense of the Divine, the miracle-working power which rewards a child-like faith, and that she will be glad if every reader closes the book with a Gloire à Dieu!

J. S.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I

CHAPTER II

CHAPTER III

CHAPTER IV

CHAPTER V

CHAPTER VI

CHAPTER VII

CHAPTER VIII

CHAPTER IX

CHAPTER X

CHAPTER XI

CHAPTER XII

CHAPTER XIII

CHAPTER XIV

CHAPTER XV

LIST OF PORTRAITS

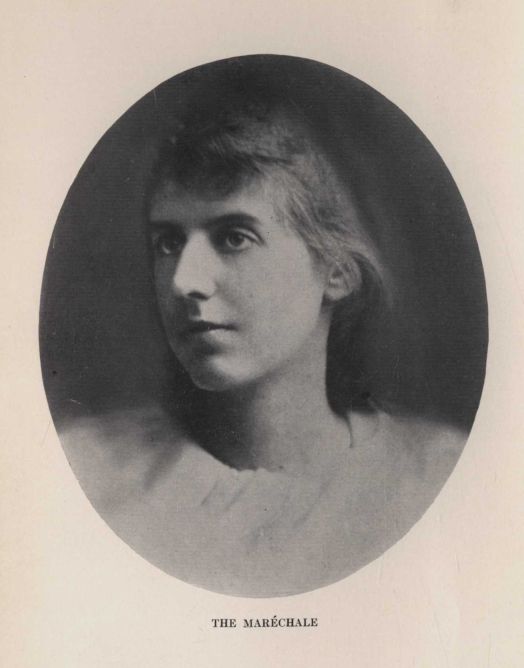

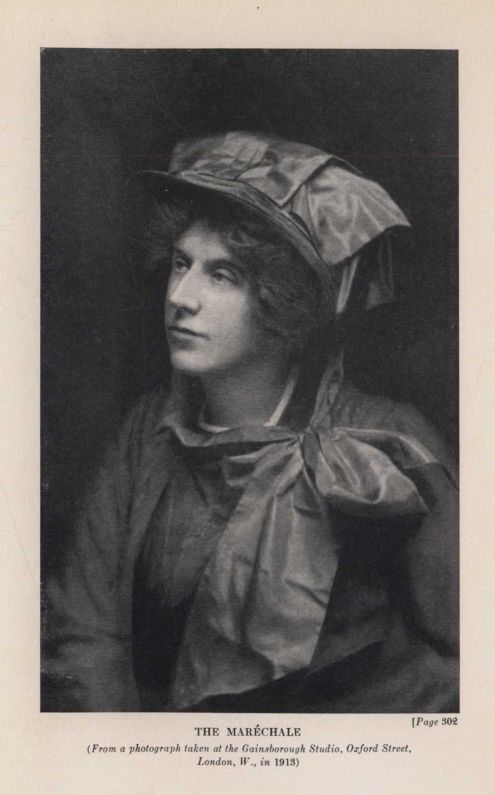

The Maréchale . . . Frontispiece

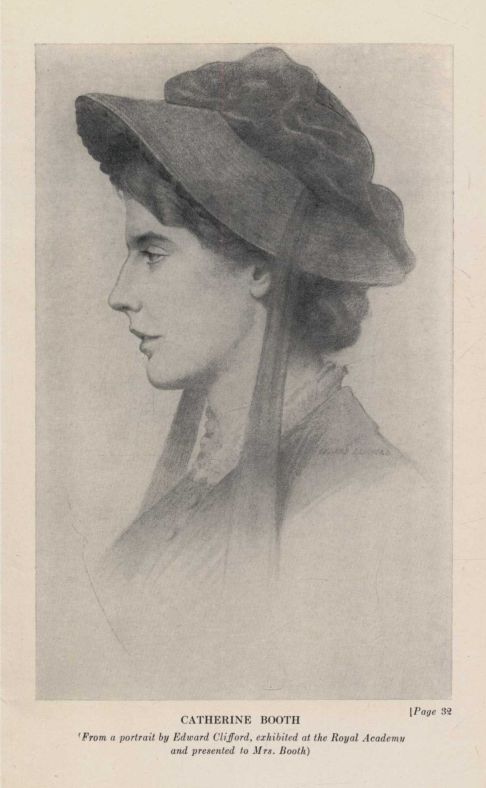

Catherine Booth . . . 32

(From a drawing by Edward Clifford, exhibited in the Royal Academy and presented to Mrs. Booth)

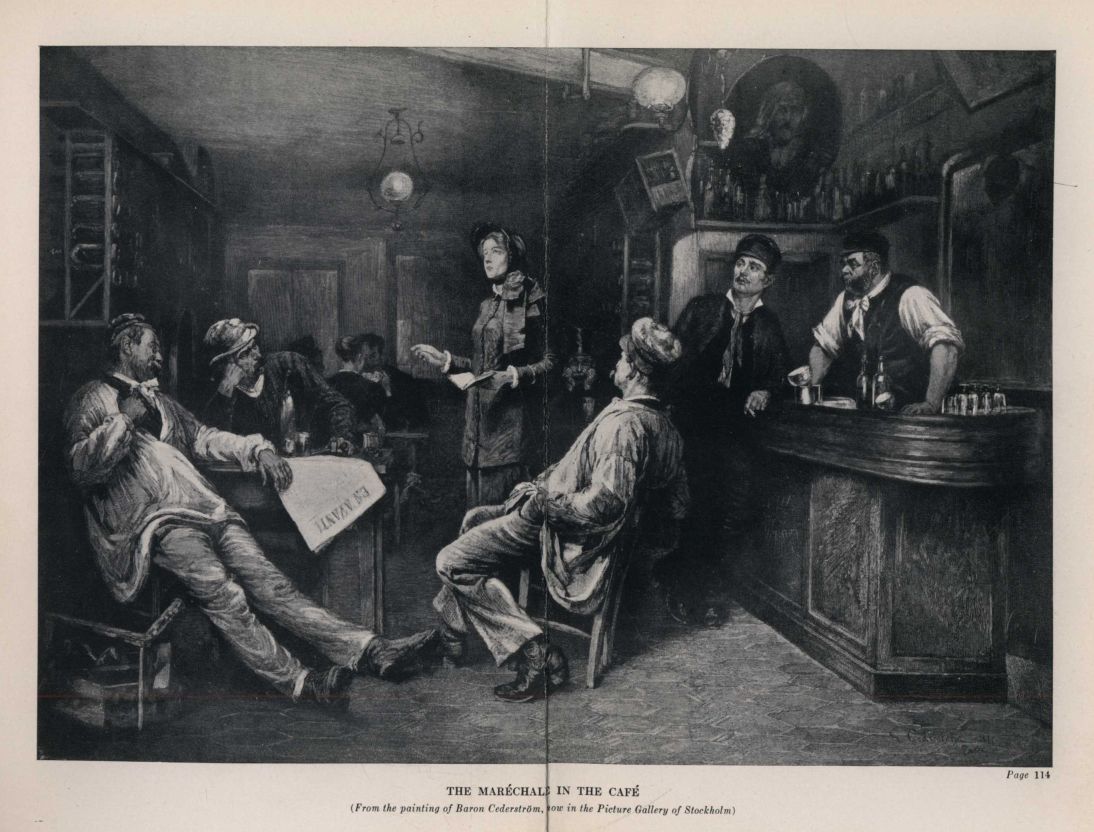

The Maréchale in the Café . . . 114

(From the painting of Baron Cederström)

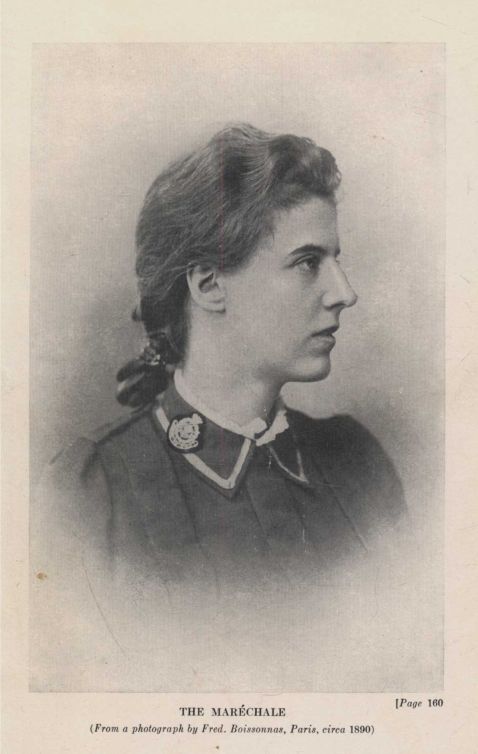

The Maréchale . . . 160

(From a photo taken in Paris, circa 1890)

The Maréchale . . . 302

(From a photo taken in London in 1913)

CHAPTER I

FINELY TOUCHED TO FINE ISSUES

In the summer of 1865 William Booth, Evangelist, found his life-work. For some time back his imagination had been more than usually active. He could not help thinking that all his past efforts had been but tentative solutions of a difficult problem. He felt the spur of a vague discontent. He seemed to be groping his way towards an unrealised ideal. At length he got the inner light he needed. While he was conducting a series of meetings in a tent pitched on the disused Quaker burying-ground at Baker's Row, Whitechapel, he saw his heavenly vision and heard his divine call. He accepted a mission which was no less real than those of Hebrew Prophets and Christian Apostles. The words in which he describes his vocation form part of the history of Christianity in England. "I found my heart," he says, "strongly and strangely drawn out on behalf of the million people living within a mile of the tent, ninety out of every hundred of whom, they told me, never heard the sound of the preacher's voice from year to year. 'Here is a sphere!' was being whispered continually in my inward ear by an inward voice ... and I was continually haunted with a desire to offer myself to Jesus Christ as an apostle for the heathen of East London. The idea or heavenly vision or whatever you may call it overcame me; I yielded to it; and what has happened since is, I think, not only my justification, but an evidence that my offer was accepted."

Thus it was that on a memorable June night, having ended his meeting and after-meeting, he rushed home, tired as usual, but with a strange light in his face which indicated an unusual glow in his heart.

"Darling," he exclaimed to his wife, "I have found my destiny!"

His unexpected words, like the touch of Ithuriel's spear, proved the quality of his life-mate's womanhood. For a moment she trembled under the test. While her husband poured out his burning words about the heathenism of London, and expressed his conviction that it was his duty to stop and preach to these East End multitudes, she sat gazing into the empty fireplace. The voice of the tempter—so she imagined—whispered to her, "This means another new departure, another start in life." She thought of five little heads asleep on their pillows upstairs, and remembered that she had already passed through more than one time of domestic anxiety. But no woman living at that time was more ready for acts of daring faith; few, if any, were so animated by scorn of miserable aims that end in self. After silently thinking and praying for some minutes, she said:

"Well, if you feel you ought to stay, stay. We have trusted the Lord once for our support and we can trust Him again."

Thus the die was cast, and the day ended with one of those scenes by which our common humanity is ennobled. "Together," he says, "we humbled ourselves before God, and dedicated our lives to the task that it seemed we had been praying for for twenty-five years. Her heart came over to my heart. We resolved that this poor, submerged, giddy, careless people should henceforth become our people and our God their God as far as we could induce them to accept Him, and for this end we would face poverty, persecution, or whatever Providence might permit in our consecration to what we believed to be the way God had mapped out for us."

One feels perfectly certain that these two modern apostles would have fulfilled their destiny even if they had stood alone; but it could scarcely have been so ample and glorious a destiny if God had not given them children who inherited their gifts and helped them to realise their ideals. It is the simple truth that the ruling passion of each of their eight sons and daughters has been the love of souls; each of them has exulted to spend and be spent in the service of Christ, which is the service of humanity; and if one of them has been too feeble in her health to be a militant Salvationist, the great Captain of our salvation accepts the will for the deed.

Among all the bold and original acts by which the breath and the flame of a new life have been brought into the modern Church, none is more striking, and yet none more simple and natural, than the revival, after all these centuries, of the apostolic ministry of women. Like Philip the Evangelist of Cæsarea, William and Catherine Booth "had four daughters who did prophesy"; brave and gifted English girls who, baptised with the Holy Spirit, used their dower of burning eloquence to bring sinners to the mercy-seat. If to-day "the women that publish the tidings are a great host," the fact illustrates the power of example. In every new movement there must be daring pioneers and self-sacrificing leaders. For woman's "liberty of prophesying," as for every other form of freedom, the price has had to be paid. The purpose of this little book is to sketch the life of the eldest of General Booth's four daughter-evangelists, who was called to carry the spirit of the Gospel—Christ's own spirit of love—first into many of the cities of England, and afterwards, in fulfilment of her distinctive life-work, into France and Switzerland, Holland and Belgium. If her story could be told as it deserves to be, it would stand out as one of the most remarkable modern records of Christian work, for there is perhaps no one living to-day who has seen so much of what Henry Drummond used to call "the contemporary activities of the Holy Ghost."

Catherine Booth the elder, the Mother of the Army, was already in her thirty-second year when she wrote her famous brochure upon Female Ministry, and, not without fear and trembling, delivered her first evangelistic address in the Bethesda Chapel at Gateshead-on-Tyne, where her husband was minister. Little Catherine, who had been baptised in that chapel, was in her second year when her mother began public speaking, and in her seventh when her father found his destiny. Probably no child ever had greater privileges than she enjoyed. Her earthly home was a house of God and a gate of heaven; and from the first she seemed to respond to all that was highest and best in her environment. She was one of those happy souls who have no memory of their conversion, who cannot recall a time when they did not heartily love the Lord Jesus Christ.

Her father was the centre of all her childish thoughts and most vivid recollections, and nothing could ever really dislodge him from the first place in her affections. An interesting page from her earliest memories may be reproduced. When she was three or four years old, her father was a Wesleyan Pastor in Cornwall, where his ministry led to a revival in which hundreds of souls found salvation. One night Katie was taken by her nurse to the meeting, and, on arrival, found herself before a flight of steps leading up to the gallery. Thinking herself quite a big girl, she wished to climb, but nurse, fearing the crowd, snatched her up and carried her to the top. At length they were inside, and what the child then saw and heard remained for ever vividly impressed on her imagination. The great building was crammed. Away down on the platform stood her father, with her mother sitting beside him. He was leading the singing, keeping time with his folded umbrella, and this was the chorus:

Let the winds blow high, or the winds blow low,It's a pleasant sail to Canaan, hallelujah!

How well did the eager-hearted little maid enjoy that voyage, and how proud she was of her captain! The winds blew low and the sun shone upon her in those days. But it could not always be fair weather. Often since that far-off Cornish time have the winds blown high, and sometimes the mariner has felt herself tossed, chartless and rudderless, on dark tempestuous seas; but ever the winds have fallen, the sun has shone out again over the waves; and to how many tens of thousands has this daughter of music sung, with sweet variations, her father's song—"It's a pleasant sail to Canaan, hallelujah!"

The Booth children were left in no mist of doubt as to their future. There was an end, a point, a purpose, in their life. They grew up in an atmosphere of decision. Many children are made timid, diffident, ineffective by their training. They are constantly told how naughty they are, till they begin to believe that they are good for nothing. The Booth parents acted on a different principle. They had faith in their children and for their children. When Katie was still a little girl in socks, her mother would say to her, "Now, Katie, you are not here in this world for yourself. You have been sent for others. The world is waiting for you." What a phrase that was to send a little girl to bed with! There she turned the words over and over in her own mind. "Mother says the world is waiting for me. Oh, I must be good.... How selfish I was in taking that orange!" The lesson was worth £1000 to a child. In the development of Katie's mind and character her mother's influence was naturally very strong. The fellowship between them soon became peculiarly intimate, and it was the mother's joy to find her alter ego in the daughter who bore her name.

Katie's memories of her early London life were bound up with the Christian Mission. Hand in hand with her sister Emma, and often singing with her "I mean with Jesus Christ to dwell, will you go?" she walked every Sunday morning along the great road leading to Whitechapel. Ineffaceable impressions were made on her sensitive mind by the open-air preaching at Mile End Waste, Bethnal Green and Hackney; by the apostolic spirit of holy enthusiasm; by the Friday morning prayer-meetings, where the officers met alone to plead with God and wrestle in tears for more power. All this became the warp and woof of her own spiritual life, preparing her for her high calling. And, though she could not remember the day of her new birth, she clearly recalled several times when she consecrated herself, body and soul, to God. In a great whitewashed building in the East End her father preached on "The King's daughters are all glorious within," and she prayed that she might have the inner purity which would make her a child of God. From a meeting of Christian workers she ran home to her room, shut herself in, and deliberately gave her heart and life to Christ. She could not, perhaps, realise all that her covenant meant, but one thing she understood—that she was called to yield herself completely to do His will and to save souls.

There was plenty of laughter and fun in that home. The Booth children were all born with the dramatic instinct, and the spirit of the Christian Mission invaded the nursery. Not only were the great dramas of the Bible—Joseph and his brothers, David and Goliath, Daniel and the lions, and a score of others—enacted there, but the meeting and the penitent form, the drunkard and the backslider, the hopeful and the desperate case were all reproduced in the plays of the children. Katie and Emma brought their babies to the meeting, and the babies generally insisted on crying, to the despair of Bramwell or Ballington, who stopped preaching to give the stern order, "Take the babies out of the theatre," against which the mothers indignantly protested, "Papa would not have stopped, papa would have gone on preaching anyhow." But the dramatic masterpiece was Ballington dealing with an interesting case—generally a pillow—coaxing, dragging, banging the poor reluctant penitent to the mercy-seat and exclaiming, "Ah! this is a good case, bless him! ... Give up the drink, brother." That is a scene which is still sometimes re-enacted to the delight of new generations.

Jesus Himself watched the games of the children who piped and mourned in the market-place. Life is none the less strenuous for its interludes of mirth. Catherine, who was dramatic to the finger-tips, was very early mastered by a sense of the sacredness of duty. The moral ideal set before her was the highest, and her conscience was tremulously sensitive. She was oppressed with the sense of what ought to be, and inconsolable when she failed to attain it. A word of rebuke cut her like a knife, and she would sometimes weep far into the night if she thought she had put pleasure before duty. It is a great thing to make religion real to children, and especially to give them a sense of the obligation to please Christ in everything. Mrs. Booth found Katie ready to go all lengths with her, and even to outrun her, in her ideas of what was right and what was wrong for Christians. It is amusing to hear that when the mother was going out one day to buy new frocks for her little girls, Katie's words to her were not "Do buy us something pretty!" but "Mind you get something Christian!" and that when Mrs. Booth came home with her purchases, and Katie rushed downstairs to meet her, the child's first inquiry was, "Are they Christian?"

But the sense of duty may become morbid if it is not transmuted by love. Many servants of God never learn the secret which makes Christ's yoke easy and His burden light. They have to confess to themselves that they cannot say, "To do Thy will, O Lord, I take delight." It would have been strange if any of the Booth children had not learned the secret. Catherine discovered it early, learned it thoroughly, and it became in after years one of the hidden sources of her power. As a child she lived in union with Christ; she practised and felt the Real Presence; she understood that Christianity is a Divine Service transfigured by a Divine Friendship. In Victoria Park there was a shady alley where she was in the habit of walking, because Some One walked beside her! In Clifton, where she lived for a time, she had a tiny upper room in which she felt that she was never alone! That was her childhood's religion, which she never needed to change. She found it to be utterly independent of time and place, form and ceremony. In the glare of public life, in the storm of persecution, in the hour of temptation and danger, she had always a cathedral into which she could retire that she might find peace. She was spiritually akin with the Hebrew mystics who lived in the secret place of the Most High, who had at all times a pavilion from the strife of tongues. In her Neuchâtel prison she wrote some simple words which sent a thrill through the heart of Christian Europe:

Best Beloved of my soul,I am here alone with Thee;And my prison is a heaven,Since Thou sharest it with me.

CHAPTER II

A GIRL EVANGELIST

When the heart is warm and full the lips become eloquent. Jesus expects each of His followers to testify for Him. His redeemed ones should need little persuasion to plead His cause. Every genuine conversion creates a new advocate for His side. Dumbness is one of the signs of unreality in religion. The sin of silence received due castigation, in public and in private, from the tongues of fire which the Spirit gave to William and Catherine Booth. Their children therefore learned that it is every Christian's calling to speak in season and out of season for Christ, to press His claims upon the willing and the unwilling alike. Katie, it appears, began among her little companions in the Victoria Park. Her old nurse still remembers how she would gather little groups about her and tell them of the Saviour's love. When she was in her twelfth year, she lived for some time with a family in Clifton, along with whom she attended the Church of England. One Sunday evening the Vicar, who had noticed her earnest gaze fixed on his face, sent for her that he might have a little talk with her. He asked her what she liked best in the Bible, and she answered "The Atonement." He was so struck by her intelligence that he offered her a children's class, which soon grew large. Week by week she talked to the little ones of sin and the Saviour. Letting story-books go, she went for their conversion. Having to return home on her twelfth birthday—the last day on which she could travel with a half-ticket—she told her mother of her great longing to continue her work among children. Her mother readily consented, and soon there was a weekly gathering of young folk in a downstairs room of the Gore Road house. After a while Katie had the assistance of her sister Emma, who was her junior by little more than a year. Tears were shed, confessions made, and lives changed in that room. And there two of the most brilliant evangelists of our time first learned to deal with souls. They were in every way kindred spirits. Long afterwards one finds Emma writing to Catherine: "We will always be 'special sisters.' We were Ma's two first girls, and were brought up side by side—and side by side we will labour and love till we stand with our children in her presence again before the Throne!"

Katie was thirteen when she first spoke in public. No one asked her to do it; she yielded to an irresistible inward impulse. Her eldest brother was conducting an open-air meeting opposite a low public-house at the corner of Cat and Mutton Bridge in Hackney. Katie was beside him, and whispered, "I will say a few words." Her brother was delighted, and she delivered her message with a directness and fluency which compelled attention and proved her a born speaker. Not very long after, she spoke in the hearing of the General, who wrote to his wife, "I don't know whether I told you how pleased I was with dear Katie speaking in the streets on Sunday morning. It was very nice and effective. Bless her!" "From this time," says Mr. Booth in a document of great importance, "she continued occasionally to speak in public meetings, but it was not until she was between fourteen and fifteen, when she was with me in Ryde, Isle of Wight, that I fully realised and settled the question. During that time my eldest son joined us for a few days, and, with another friend or two, held open-air meetings; on one of these occasions Catherine accompanied them, and her brother induced her to say a few words, which it appears fell with extraordinary power upon the listening crowd of men and others, such as usually comprise the visitors at these places. On their return my son described to me the effects of her address, but, not being fully emancipated from my old ideas of propriety, I remonstrated and urged such objections as I presume any other mother, consecrated but not fully enlightened, might have urged against her being thrust into such a public position at such an early age. My son, gazing at me with great solemnity and tenderness, said, 'Mamma, dear, you will have to settle this question with God, for she is as surely called and inspired by Him for this particular work as yourself.' These words were God's message to my soul, and helped me to pull myself up as to the ground of my objection. I retired to my room, and, after pouring out my heart to God, settled the question that henceforth I would raise no barrier between any of my children and the carrying out of His will concerning them, trying to rejoice that they, not less than myself, should be counted worthy to suffer shame for His name."

From that time Catherine's path was clearly marked out. While she continued her education, which included a special liking for French, she gradually undertook more and more public work. Her father's delight in her ripening powers found frequent utterance, and her companionship with him during the next six years of work is one of the most beautiful things in the literature of evangelism. "William," said Mrs. Booth about this time, "writes that he is utterly amazed at Katie; he had no idea that she could speak as she does. He says that she is a born leader, and will if she keeps right see thousands saved.... Praise His name that she can stand in my stead, and bear His name to perishing souls." After holding meetings in different parts of London, from Stratford and Poplar to Hammersmith, Catherine began, just before she was seventeen, to conduct evangelistic campaigns in many of the other great cities of England, sometimes lasting three weeks or a month. The largest building in the town densely crowded Sunday after Sunday, and frequently on week nights as well; hundreds of people to speak to about their souls' salvation every week; correspondence and travel; ceaseless labour and responsibility—these things absorbed all her energies of body and mind. She was but a frail girl, and suffered for a time from a curvature of spine, which compelled her to lie on her back in great weakness and pain. If she yet overcame, it is evident that she was "marvellously helped."

In 1876 Katie was one of the speakers at the annual Conference in the People's Hall, Whitechapel. As she appeared on the platform, she was described by her lifelong friend, R. C. Morgan of The Christian, as "a fragile, ladylike girl of seventeen, half woman, half child, a characteristic product of the Christian Mission, whose words fell like summer rain upon the upturned faces of the crowd." This was the Conference at which the epoch-making measure was adopted of appointing women evangelists to the sole charge of stations. Miss Booth was reserved "for general evangelistic tours."

It is interesting to glance through the numbers of the old Christian Mission Magazine and light upon brief reports of Catherine's work. From Hammersmith (1875): "Miss Kate Booth [age 16] spent a Sabbath with us, preaching twice with great acceptance. A large audience was deeply impressed, and some, we trust, were truly converted to God." From Poplar: "Mr. Bramwell and Miss C. Booth were with us. On the Sunday and Monday evening the hall was crowded, and some thirty souls at the two services sought salvation.... On Easter Sunday one sister's face was cut with a stone, and heavy stones fell upon some on many occasions of late; but we endure as seeing Him who is invisible." From Portsmouth: "Miss Booth, assisted by W. Bramwell Booth, commenced a series of special services, which God owned and blessed to the salvation of many precious souls. In the morning Miss Booth preached, and all felt it good to be there. Then a love-feast was conducted by W. B. Booth in the afternoon.... In the evening Miss Booth preached in the music-hall to upwards of three thousand people. The Spirit applied the Word with power, and seventeen broke away from the ranks of sin and enlisted under the banner of Jesus Christ." Again from Portsmouth, some months later: "We had a visit from Miss Booth with her brother Mr. Bramwell, and again the dear Lord blessed their labours in this town. Each service was fraught with Divine power; many trembled under the Word, and anxious ones came forward seeking forgiveness of sins, until the penitent-rail and vestry were filled with those who, in bitterness of soul, sought pardon and peace through Jesus."

From Limehouse (1876): "We had dear Miss Booth and her brother, and a blessed day. In the evening she preached with wonderful power, and ten or twelve came out for God. May they be kept faithful!" From Portsmouth: "Miss Booth's visit was made of the Lord a great blessing to us all. Very few who listened to her in the morning will forget how she pleaded with us to present our bodies a living sacrifice. Oh, may God bless her and make her a mighty blessing, for Christ's sake." From Whitechapel (1877): "An earnest appeal was made at one of our Sunday evening services by Miss Booth, from 'Run, speak to that young man.' Although in very delicate health, the Lord blessedly assisted her. The word was with power, and eleven souls decided for Jesus, among whom was the converted Potman. This young man was a leader in petty and mischievous annoyances. The genuineness of his conversion was evidenced by his giving up the public-house work to seek more honourable employment." From Middlesbro' (1878): "Miss Booth visited us for five days, and many blood-bought souls have been blessed and saved. Her first Sunday with us was a day of power, and it will not be soon forgotten by those present. It was a grand sight to see a large hall filled to the door with anxious hearers, while hundreds went away; but the grandest sight of all was to see old and young flocking to the penitent form." From Leicester: "Miss Booth's services may be summarised in the statement that she had twenty-two souls the first Sunday evening, and increasing victory thereafter right on to the end."

At Whitby there was a six weeks' campaign, organised by Captain Cadman. On the first Sunday "the large hall, which holds three thousand, was well filled, and in the after service many souls were brought to Jesus." On the second Sunday "Miss Booth was listened to with breathless attention. In the after service we drew the net to land, having a multitude of fishes, and among them we found we had caught a fox-hunter, a dog-fancier, drunkards, a Roman Catholic, and many others. In the week-night services souls were saved every night. The proprietor of the hall had got some large bills out announcing 'Troupe of Arctic Skaters in the Congress Hall for a week,' but he put them off by telling them it was no use coming, as all the town was being evangelised." The concluding services "drew great crowds from all parts of town and country, rich and poor, until the hall was so filled that there was no standing room." In a Consecration meeting, "After Miss Booth's address we formed a large ring in the centre of the hall, which brought the power down upon us; hundreds looked on with astonishment and tears in their eyes, whilst others gave themselves wholly to God.... Ministers, like Nicodemus of old, came to see by what power these miracles were wrought, and, going back to their congregations, resolved to serve God better, and to preach the gospel more faithfully in the future."

From Leeds: "Miss Booth in the Circus. A glorious month. Hard-hearted sinners broken down. Best of all, our own people have been getting blessedly near to God. On Sunday mornings love feasts from nine to ten.... It would be impossible to give even an outline of the various and glorious cases of conversion that have come under our notice through the month which is past. For truly Christ has been bringing to His fold rich and poor, young and old." From Cardiff: "The question, 'Does this work stand?' received a magnificent reply on Sunday. The crowds who filled the Stuart Hall, to hear Miss Booth, were the largest any one can remember seeing during all the four years of the Mission's history there." From King's Lynn: "Miss Booth's Mission. The town has had a royal visit from the Lord of Lords and King of Kings. There has been a great awakening, and trembling, and turning to the Lord. Whole families have been saved, and whole courts have sought salvation. Our holiness meeting will never be forgotten.... The work here rolls on gloriously. Not only in Lynn but for miles round the town it is well known that a marvellous work has been done and is still going forward."

All these battles and victories were naturally followed by the General with intense interest, and as often as it was possible he was at his daughter's side. Mrs. Booth joined them when they were opening a campaign together at Stockton-on-Tees, and sent her impressions to a friend. "Pa and Katie had a blessed beginning yesterday. Theatre crowded at night, and fifteen cases. I heard Katie for the first time since we were at Cardiff. I was astonished at the advance she had made. I wish you had been there, I think you would have been as pleased as I was. It was sweet, tender, forcible, and Divine. I could only adore and weep. She looked like an angel, and the people were melted, and spellbound like children." The General began to call her his "Blücher," for she helped to win many a hard-fought battle which he might otherwise have lost. When the rowdies threatened to take the upper hand at a meeting, he would say, "Put on Katie, she's our last card; if she fails we'll close the meeting."

"I remember," wrote her eldest brother, "a striking instance of this occurring in a certain northern town on a Sunday night. A crowd assembled at the doors of the theatre, composed of the lowest and roughest of the town, who, overpowering the doorkeepers, pressed into the building and took complete possession of one of the galleries, so that by the time the remainder of the theatre was occupied this portion of it represented a scene more like a crowded tap-room than the gallery of what was for the moment a place of worship. Rows of men sat smoking and spitting, others were talking and laughing aloud, while many with hats on were standing in the aisles and passages, bandying to and fro jokes and criticisms of the coarsest character. All this continued with little intermission during the opening exercises, and the more timid among us had practically given up hope about the meeting, when Miss Booth rose, and standing in front of the little table just before the footlights, commenced to sing, with such feeling and unction as it is impossible to describe with pen and ink,

'The rocks and the mountains will all flee away.And you will need a hiding-place that day.'

There was instantaneous silence over the whole house; after singing two or three stanzas, she stopped and announced her text, 'Let me die the death of the righteous and let my last end be like His.' While she did so nearly every head in the gallery was uncovered, and within fifteen minutes both she and every one of the fifteen hundred people present were completely absorbed in her subject, and for forty minutes no one stirred or spoke among that unruly crowd, until she made her concluding appeal, and called for volunteers to begin the new life of righteousness, when a great big navvy-looking man rose up, and in the midst of the throng in the gallery exclaimed, 'I'll make one!' He was followed by thirty others that night."

(From a portrait by Edward Clifford, exhibited at the Royal Academy

and presented to Mrs. Booth)

Well might the General's hopes regarding the young soul-winner be high and confident. "Papa," wrote Mrs. Booth, "says he felt very proud of her the other day as she walked by his side at the head of a procession with an immense crowd at their heels. He turned to her and said, 'Ah, my lass, you shall wear a crown by-and-by.'"

With what desires and prayers the mother of this Wunderkind followed such a career is indicated by her letters. "Oh, it seems to me that if I were in your place—young—no cares or anxieties—with such a start, such influence, and such a prospect, I should not be able to contain myself for joy. I should indeed aspire to be 'the bride of the Lamb,' and to follow Him in conflict for the salvation of poor, lost and miserable man.... I don't want you to make any vows (unless, indeed, the Spirit leads you to do so), but I want you to set your mind and heart on winning souls, and to leave everything else with the Lord. When you do this you will be happy—oh, so happy! Your soul will then find perfect rest. The Lord grant it you, my dear child.... I have been 'careful about many things.' I want you to care only for the one thing.... Look forward, my child, into eternity—on, and ON, and ON. You are to live for ever. This is only the infancy of existence—the school-days, the time. Then is the grand, great, glorious eternal harvest."

Whatever gifts were the dower of the young evangelist, she refused to regard herself as different in God's sight from the poorest and meanest of sinners. If God loved her, He loved all with an equal love. That conviction was the motive-power of all her evangelism. A limited atonement was to her unthinkable. How often she has made vast audiences sing her father's great hymn, "O boundless salvation, so full and so free!" When she was conducting a remarkable campaign in Portsmouth, she found herself one day among a number of the ministers of the town, one of whom in his admiration of her and her work persisted in calling her one of the elect. This led to an animated discussion on election. Katie listened for a while, but lost patience at last, and, rising, delivered herself thus: "I am not one of the elect, and I don't want to be. I would rather be with the poor devils outside than with you inside." Having discharged this bombshell she flew upstairs to her mother. "Oh!" she cried, "what have I done?" When she repeated what she had said, her mother, whose laugh was always hearty, screamed with delight. Election as commonly taught was rank poison to the Mother of the Army. The doctrine that God has out of His mere good pleasure elected some to eternal life made her wild with indignation. When her son Bramwell was staying for a time in Scotland, she wrote him: "It seems a peculiarity of the awful doctrine of Calvinism that it makes those who hold it far more interested in and anxious about its propagation than about the diminution of sin and the salvation of souls.... It may be God will bless your sling and stone to deliver His servant out of the paw of this bear of hell—Calvinism."

One naturally asks what became of Catherine's education all this time. On this subject also Mrs. Booth held strong views. When her daughter was sixteen she wrote to her: "You must not think that we do not rightly value education, or that we are indifferent on the subject. We have denied ourselves the common necessaries of life to give you the best in our power, and I think this has proved that we put a right value on it. But we put God and righteousness first and education second, and if I had life to begin over again I should be still more particular.... I would like you to learn to put your thoughts together forcibly and well, to think logically and clearly, to speak powerfully, i.e. with good but simple language, and to write legibly and well, which will have more to do with your usefulness than half the useful knowledge you would have to spend your time over at College." When the principal of a Ladies' College, who had attended Mrs. Booth's meetings and been blessed, offered to receive Catherine and educate her gratuitously, Mrs. Booth, after visiting the College and breathing the atmosphere of the place, declined the tempting offer with thanks. Some will, of course, be disposed to question the wisdom of the mother's decision. It should not be impossible to combine the noblest learning with the most fervent faith. Yet every discipline must be judged by its fruits. How many Catherine Booths have hitherto been produced by Newnham and Girton?

Long after Catherine the second had left her home-land, she continued to receive letters from her English converts, and when, after many years, she resumed her evangelistic work in England, people whom she had never seen and never heard of before would come and tell her that they had been saved through her mission at this or that place. All these testimonies were like bells ringing in her soul. One out of many may be resounded. Writing to Paris in 1896, Henry Howard, now the Chief of Staff in the Army, said: "I have certainly never forgotten your Ilkeston campaign of sixteen years ago, when God made your soul a messenger to my soul. You led me towards an open door which I am pleased to remember I went in at, and during these many years your own share in my life's transformation has often been the subject of grateful praise."

CHAPTER III

THE SECRET OF EVANGELISM

After many victories at home, William and Catherine Booth began to look abroad. They realised that "the field is the world," and they longed to commence operations on the Continent. In the summer of 1881, with high hopes and some natural fears, they dedicated their eldest daughter to France. In giving her they gave their best. Delicate girl though she was, she had become one of the greatest spiritual forces in England. She swayed vast multitudes by something higher than mere eloquence. Wherever she went revivals broke out and hundreds were converted. There was a pathos and a power in her appeals which made them irresistible.

At the time of her departure she received many letters from friends whom she had spiritually helped, and who realised how much they would miss her in England. Nowhere had she done more good, nowhere could her absence create a greater blank, than in her own home. Her sister Eva wrote: "I cannot bear the thought that you are gone. You have always understood me. I hope one day to be of some use to you, in return for all you have done for me." And her brother Herbert wrote her: "You cannot know how much I felt your leaving. The blow came so suddenly. You were gone. Only God and myself know how much I had lost in you. I can truthfully say that you have been everything to me, and if it had not been for you I should never have been where and what I am spiritually at present. God bless you a thousand thousand times. Oh! how I long to be of some little service to you after all you have been to me.... Thousands upon thousands of true, loving hearts are bearing you up at the Eternal throne, mine among them. You have a chance that men of the past would have given their blood for, and that the very angels in Heaven covet."

There was no Entente Cordiale in those days, and at the thought of parting with Katie, and letting her go to live in the slums of Paris, Mrs. Booth confessed that she "felt unutterable things." In a letter to a friend she wrote: "The papers I read on the state of Society in Paris make me shudder, and I see all the dangers to which our darling will be exposed!" But if her fears were great, her faith was greater. Asked by Lady Cairns how she dared to send a girl so young and unprotected into such surroundings, she answered, "Her innocence is her strength, and Katie knows the Lord." And if Katie herself was asked to define Christianity, she answered, "Christianity is heroism!" For a girl of this spirit, was there, after all, anything so formidable in the French people? Was there not rather a pre-established harmony between her and the pleasant land of France, as her remarkable predilection for the French language already seemed to indicate? Is any nation in the world so chivalrous as the French? any nation so sensitive to the charm of manner, the magnetic power of personality? any nation—in spite of all its hatred of clericalism—gifted with so infallible a sense of the beauty of true holiness? Courage, camarade!

What were the ideas with which Catherine began her work in Paris? What was her plan of campaign? How did she hope to conquer? On these points let us listen to herself. "I saw," she says, "that the bridge to France was—making the French people believe in me. That is what the Protestants do not understand. They preach the Bible, they write books, they offer tracts. But that does not do the work. 'Curse your bibles, your books, your tracts!' cry the French. I have seen thousands of testaments given away to very little purpose. I have seen them torn up to light cigars. And the conviction that took shape in my mind was that, unless I could inspire faith in me, there was no hope. Only if Jesus is lifted up in flesh and blood, will He to-day draw all men to Him. If I cannot give Him, I shall fail. France has not waited till now for religion, for preaching, for eloquence. Something more is needed. 'I that speak unto thee am He'—there is a sense in which the world is waiting for that to-day. You may say that this leads to fanaticism, to all sorts of error; and yet I always come back to it. Christ's primary idea, His means of saving the world, is, after all, personality. The face, the character, the life of Jesus is to be seen in men and women. This is the bridge to the seething masses who believe in nothing, who hate religion, who cry 'Down with Jesus Christ!' What sympathy I felt with them as I listened to their angry cries against something which they had never really seen or known. They shout 'Jesuits,' but they have never seen Jesus. Could they but see Him, they would still 'receive Him gladly.' It is the priests' religion that has made them bitter. 'Money to be baptised! Money to be married! Money to be buried!' was what I heard them mutter. Ah! they are quick to recognise the comedian in religion, and equally quick to recognise the real thing. France is more sensitive to disinterested love than any nation I have ever known. France will never accept a religion without sacrifice.

"These were the convictions with which I began the work in Paris, and, if I had to begin it over again to-day, I would go on the same lines. When I knew what I had to do, my mind was at rest. I said, 'We will lay ourselves out for them; they shall know where we live, they can watch us day and night, they shall see what we do and judge us.' And the wonderful thing in those first years of our work in France and Switzerland was the flame. We lighted it all along the line. Wherever we went we brought the fire with us, we fanned it, we communicated it. We could not help doing so, because it was in us, and that was what made us sufferers. The fire had to be burning in us day and night. That is our symbol—the fire, the fire!

Seigneur, ce que mon coeur réclame,C'est le Feu ...Le seul secret de la Victoire,C'est le Feu.

We all know what the fire is. It warms and it burns; it scorches the Pharisees and makes the cowards fly. But the poor, tempted, unhappy world knows by whom it is kindled, and says: 'I know Thee who Thou art—the Holy One of God!'

"That was what filled the halls at Havre and Rouen, Nîmes and Bordeaux, Brussels and Liège. We personified Some One, and that was the attraction. I have not the insufferable conceit to suppose that it was anything in me that drew them. What am I? Dust and ashes. But if you have the fire, it draws, it melts; it consumes all selfishness; it makes you love as He loves; it gives you a heart of steel to yourself, and the tenderest of hearts to others; it gives you eyes to see what no one else sees, to hear what others have never given themselves the trouble to listen to. And men rush to you because you are what you are; you are as He was in the world; you have His sympathy, His Divine love, His Divine patience. Therefore He gives you the victory over the world; and what is money, what are houses, lands, anything, compared with that?

"This was the one attraction. When I went to France I said to Christ: 'I in You and You in me!' and many a time in confronting a laughing, scoffing crowd, single-handed, I have said, 'You and I are enough for them. I won't fail You, and You won't fail me.' That is something of which we have only touched the fringe. That is a truth almost hermetically sealed. It would be sacrilege, it would be desecration, it would be wrong, unfair, unjust if Divine power were given on any other terms than absolute self-abandonment. When I went to France I said to Jesus, 'I will suffer anything if You will give me the keys.' And if I am asked what was the secret of our power in France, I answer: First, love; second, love; third, love. And if you ask how to get it, I answer: First, by sacrifice; second, by sacrifice; third, by sacrifice. Christ loved us passionately, and loves to be loved passionately. He gives Himself to those who love Him passionately. And the world has yet to see what can be done on these lines."

CHAPTER IV

CHRIST IN PARIS

In the early spring of 1881 Captain Catherine Booth and her intrepid lieutenants, Florence Soper, Adelaide Cox and Elizabeth Clark, who enjoyed the privilege of her example and training, began life in Paris. Later on they were joined by Ruth Patrick, Lucy Johns and others. Soon after they were joined by the General's youngest son, Herbert Booth, who is proud of having received his first black eye in assisting his sister during those early fights, and Arthur Sydney Clibborn, who lived a life of unparalleled devotion and heroism, and later became the Maréchale's husband. Years before Canon Barnett and his band of Oxford men were attracted to Whitechapel, these fresh young English girls settled in a similar quarter of the French capital. What quixotic impulses carried them thither? They had no social or political ideals to realise. They had not been persuaded that altruism is better than egoism, that the enthusiasm of humanity is nobler than the pursuit of pleasure or the love of culture. They were not weary of the conventions of society and seeking a new sensation in slumming. They were not playing at soldiers. But they, too, had their dreams and visions. They loved Christ, and they wished to see Christ victorious in Paris. Coming into a wilderness of poverty, squalor and vice, they dared to believe that they could make the desert to rejoice and blossom as the rose. They had the faith which laughs at impossibilities.

The first letter Catherine received from her father after she set foot in France breathed tender affection and ardent hope. "Oh, my heart does yearn over you! How could you fear for a single moment that you would be any less near and dear to me on account of your brave going forth to a land of strangers to help me in the great purpose and struggle of my life? My darling, you are nearer and dearer than ever.... France is hanging on you to an extent fearful to contemplate, and you must regard your health, seeing that we cannot go on without you. We shall anxiously await information as to when you make a start. Everybody who has heard you and knows you feels the fullest confidence in the result. Nevertheless I shall be glad for you to get to work, seeing that I know you won't be easy in your mind until you have seen a few French sinners smashed up at the penitent form."

With her own hand Catherine raised the flag at Rue d'Angoulême 66, in Belleville. Here was a hall for six hundred, situated in a court approached by a narrow street. The bulk of the audience that gathered there night after night were of the artisan class. Some were young men of a lower type, and from these came what disturbance there was. The French sense of humour is keen, and there were many lively sallies at the expense of the speakers and singers on the platform. Every false accent, every wrong idiom, every unexpected utterance or gesture was received with an outburst of laughter. But the mirth was superficial, and the expression on the faces of the tired men, harassed women, and pale children was one of settled melancholy. Catherine instinctively felt that what they needed was a gospel of joy; certainly not the preaching of hell, for did they not live in hell? These toiling sisters and brothers were the multitudes on whom Jesus had compassion.

Meetings were held night after night, and for six months the Capitaine was never absent except on Saturdays. Those were days of fight, and she fought, to use her own phrase, like a tiger. She had to fight first her own heart. She knew her capacity, and God had done great things through her in England. The change from an audience of five thousand spellbound hearers in the circus of Leeds to a handful of gibing ouvriers in the Belleville quarter of Paris was indeed a clashing antithesis. A fortnight passed without a single penitent, and Catherine was all the time so ill that it was doubtful if she would be able to remain in the field. That fortnight was probably one of the supreme trials of her faith. The work appeared so hopeless! There was nothing to see. But for the Capitaine faith meant going on. It meant saying to her heart, "You may suffer, you may bleed, you may break, but you shall go on." She went on, believing, praying, fighting, and at last the tide of battle turned.

The beginning of what proved a memorable meeting was more than usually unpromising. One of the tormentors, a terrible woman, known as "the devil's wife," excelled herself that night. She was of immense size, and used to stand in the hall with arms akimbo and sleeves rolled up above the elbows, and with one wink of her eye would set everybody screaming and yelling. On this occasion there was not a thing that she did not turn to ridicule. The fun grew fast and furious, and some of the audience got up and began to dance. The meeting seemed to be lost; but by a master-stroke the leader turned defeat into victory. Through the din she cried, "Mes amis! I will give you twenty minutes to dance, if you will then give me twenty minutes to speak. Are you agreed?" A tall, dark, handsome ouvrier, in a blue blouse, who had been a ringleader in the disturbances, jumped up and said, "Citizens, it is only fair play;" and they all agreed. So they had their dance, and at the end of the appointed time the ouvrier, standing with watch in hand, cried, "Time up, citizens; it is the Capitaine's turn!" The bargain was kept. Everybody sat down, and an extraordinary silence filled the place. Not for twenty, but for an hour and twenty minutes the leader had the meeting in the hollow of her hand. When the audience filed out, the tall ouvrier remained behind, and Catherine went down to where he was sitting in the back of the hall. With his chiselled face and firm-set mouth, he looked like a man who could have seen one burned alive without moving a muscle.

"Thank you," said the Capitaine, "you have helped me to-night. Have you understood what I have been saying?"

"I believe that you believe what you say."

"Oh! of course I believe."

"Well, I was not sure before." With a sigh he added, "Have you time to listen?"

"Yes, certainly."

It was midnight and they were alone. As he began in softest tones to tell the story of his inner life, she felt the delicacy of the soul that is hidden under the roughest exterior. He said, "I had the happiest home in all Paris. I married the woman I loved, and after twelve months a little boy came to our home. Three weeks after, my wife lost her reason, and now she is in an asylum. But there was still my little boy. He was a beautiful child. We ate together, slept together, walked and talked together. He was all the world to me. He was the first to greet me in the morning, and the first to welcome me in the evening when I came home from work. This went on till the sixth year struck, and then...." His lips twitched, and he turned his face away. His hearer softly said, "He died." He gave a scarcely perceptible nod, and smothered a groan. "And then," he continued, "I went to the devil. Before the open grave in the Père Lachaise cemetery, with hundreds of my comrades about me, I lifted my hand to heaven and cried, 'If there be a God, let Him strike me dead!'"

"But He did not strike you dead?"

"No."

"He is very gentle and patient with us all. And now you have come here to-night. Does it not seem to you a strange thing that you out of all the millions of France, and I out of all the millions of England should be all alone together here at midnight? How do you account for it? Isn't it because God thought of you, and loves you? ... Do you ever pray?"

"I pray? Oh, never! Perhaps I prayed as a child, but never now."

"But I pray," said the Capitaine, and, kneeling down, she prayed a double prayer, for herself as well as for him. She wanted this man's salvation for her own sake and the work's sake. For weeks she had been fighting and praying for a break, and she felt as if on the issue of this wrestling for a single soul depended the whole future of the work in France. While she prayed for his salvation from sin she was silently praying for her own deliverance from doubt and fear and discouragement. And both prayers were heard. When she opened her eyes, she saw his face bathed in tears. She knew that his heart was melted, and she spoke to him of the love of God.

"But I have hated Him. I have hated religion; I have come here to mock you; I have called you Jesuits."

"Yet God loves you."

"But why did He allow my wife to lose her reason? Why did He take my child if He is love?"

"I cannot answer these questions. You will know why one day. But I know He loves you."

"Is it possible that He can forgive a poor sinner like me?"

"It is certain."

Émile was won. Some nights afterward he gave his testimony, and for seven years he always stood by the Maréchale. He was her best helper. When he used to get up to speak, there was immediate attention. "Citizens," he would say, "you all know me. You have heard me many times. This God whom I once hated I now love, and I want to speak to you about Him."

After this, conversions became frequent. The mercy-seat was rarely empty. One of the first French songs of Catherine's composition contained the most curious idioms:

Quand je suis souffrant,Entendez mon cri, etc.—Donnez moi Jesus.

But she sang it with such feeling that it was the means of the conversion of a clever young governess, who became one of her most devoted officers.

Then another striking conquest was made. One night a rough fellow, partly drunk, approached the Capitaine and said a vile word to her in the hearing of "the devil's wife," who dealt him a blow that sent him reeling across the hall crying, "You dare not touch her, she is too pure for us!" (Elle est trop pure pour nous!) Catherine rushed between them and stopped the fight. Thus "la femme du diable" was won, and from that time she got two or three others to join her in forming Catherine's bodyguard, who nightly escorted her and her comrades through the Rue d'Allemagne, which was a haunt of criminals, and saw her safe at the door of her flat in the Avenue Parmentier.

When Baron Cederström was seeking local colour for his painting "The Maréchale in the Café,"[1] he drove down with his wife to a meeting in the Rue d'Angoulême. As they approached the hall, the Baroness caught sight of some of the faces and took fright.

[1] This painting is now in the picture gallery of Stockholm. The artist, as is well known, afterwards married Madame Patti.

"Go back, go back!" she shouted to the coachman.

The Baron tried in vain to reassure her.

"Give me my salts!" she cried, feeling as if she would faint. "I never saw such faces in my life. They are all murderers and brigands." To Catherine, who came out to welcome her, she exclaimed, "I am sure the good God won't send you to Purgatory, for you have it here!"

"You have nothing to fear," was the answer; "I am here every night." But as the Baroness was led up to the front seats, she still cast scared looks at the people she passed.

Some of the politically dangerous classes did give trouble for a time. Knives were displayed and some blood was shed. An excited sergeant of police declared one night that half the cut-throats of Paris were in that hall, and by order of the authorities it was closed. Soon, however, the meetings were again in full swing, and when Catherine's eldest brother Bramwell, her comrade in many an English campaign, paid her a flying visit three months after she left home, he was delighted with all that he saw. "The meetings," he wrote, "are held every night. The congregations vary from 150 to 400.... On Sunday, at three, I attended the testimony meeting, which is only for converts and friends. About seventy were present. Miss Booth took the centre, and gathered round her a little company. I cannot describe that meeting. When I heard those French converts singing that first hymn, 'Nearer to heaven, nearer to heaven,' I wept for joy, and during the season of prayer which followed my heart overflowed. Here, using another tongue, among a strange people, almost alone, this little band have trusted the Lord and triumphed.... Then testimonies were invited.... I wept and rejoiced, and wept again. I glorified God. Had I not heard these seventeen people speak in their own language of God's saving power in Paris during those few weeks! I require all who read this to rejoice. I believe they will. Remember how great a task it is to awaken the conscience before Christ can be offered; to convince of sin as well as of righteousness; to call to repentence as well as faith.... On the following night 300 were present.... Miss Booth stepped off the platform as she concluded her address, and came down, as so many of us have seen her come down at home, into the midst of the people. Her closing appeal seemed to go through them. Many were deeply moved. Some of those sitting at the back, who had evidently come largely for fun, quailed before one's very eyes, and seemed subdued and softened. God was working."

Later in the year the new headquarters on the Quai de Valmy were opened. Here there was a hall for 1200. No other form of religion could draw such an assembly of the lowest class of Parisians as nightly met in it. The men came in their blouses, kept their caps on their heads, and—except that they abstained from smoking, in obedience to a notice at the door—behaved with the freedom and ease of a music-hall audience. But the earnest way in which most of those present joined in the hymns proved that they were not mere spectators, and it was astonishing that many rough, unkempt, and even brutal-looking men soon learned to sing heartily without using the book.

There were a hundred converts in the first year and another five hundred in the second. Paris herself began to testify that a good work had been begun in her midst. On the way to and from the hall in the Rue d'Angoulême Catherine, who by this time had begun to be endearingly known as the Maréchale, the highest military title in France, used often to meet a priest, to whom she always said "Bon jour, mon père." One day he paused and said, "Madame la Maréchale, I want to tell you that since you began your work in this quarter the moral atmosphere of the whole place has changed. I meet the fruits everywhere, and I can tell better than you what you are doing." She felt that God sent her that word of encouragement.

One of her letters of this time indicates what kind of impression her work was making. "There is a man," she wrote, "who has attended our meetings most regularly. He listens with breathless attention, and sometimes the tears flow down his cheeks. He was visited, and sent me 70 francs for our work, with a message that he desired to see me. I saw him, and he gave me 80 more, with the words 'Sauvez la jeunesse'! ('Save the young!') I found him very dark and hopeless about himself.... The next week he again called me aside in the hall, put 50 francs into my hand, saying he hoped soon we should have a hall in every quarter of Paris. 'Save the young people!' he again said. I said 'Yes, but I want to see you saved.' 'That will come,' he said, and left the hall. Last Sunday afternoon, I noticed him weeping in a corner of the hall, as our young people were witnessing for Jesus, and, after the services, he asked if he might speak to me for two minutes; this time he handed me 60 francs, telling me to go on praying for him. He has lived a bad life and is troubled with the thought of the past."

It began to be commonly believed that the Maréchale could work certain kinds of miracles. A woman who had attended the meetings, and been blessed in her soul, became convinced that the English lady had power to cast out devils, and one day she brought a neighbour to the physician of souls, introducing her with the remark, "She has not only one but seven devils." The new-comer had a frightful face. She was so drunken, immoral and violent that nobody could live with her. Yet she, too, had a soul. The Maréchale made her get down on her knees, put both her hands on her head, and prayed that the devils might all be cast out. "She's now another woman," was the testimony soon after borne by all her neighbours.

One of the surest indications of the success of the work in Paris is found in the fact that, before the end of the first year there was a general demand for a newspaper corresponding in some degree to the English War Cry. That was a memorable day on which the Maréchale and her officers sat in their Avenue Parmentier flat, like a coterie of Fleet Street journalists, gravely discussing their new venture. It was indicative of the holy simplicity of the editor-in-chief that she thought at first of changing The War Cry into Amour. She did not realise the sensation which the cry "Amour, un sou!" would have created in the Boulevards. Her proposal was overruled, but her second suggestion, to call the paper En Avant, was received with acclamation. This was a real inspiration. The paper duly appeared in the beginning of 1882, and has gone on successfully ever since. The shouting of its name in the streets set all the world and his wife a-thinking and a-talking. What if the Man of Nazareth is after all far ahead of our modern philosophers and statesmen, and if this handful of English girls is come to lead us all forward to true liberty, equality and fraternity?

The reports of the work in France were received with feelings of gratitude at home. To "My dear Kittens"—a family pet-name—her brother Bramwell wrote: "We are more than satisfied with your progress. The General says that so far as he can judge your rate of advance in making people is greater than his own was at the beginning. I am sure you ought to feel only the liveliest confidence and greatest encouragement all the time." And to "My darling Blücher" the General himself wrote, "I appreciate and admire and daily thank God for your courage and love and endurance. God will and must bless you. We pray for you. I feel I live over again in you. We all send you our heartiest greetings and our most tender affection. Look up. Don't forget my sympathy. Don't trouble to answer my scrawls. I never like to see your handwriting because I know it means your poor back. Remember me to all your comrades."

"I feel I live over again in you." The thought was evidently habitual in the General's mind. "He bids me tell you," wrote Emma, "that you are his second self." The resemblance was physical as well as spiritual. With her tall figure, her chiselled face, her aquiline nose, her penetrating blue eyes, Catherine became, as time went on, more and more strikingly like her father. One of her sons, who saw her stooping over the General the day before he died, said that the two pallid faces were like facsimiles in marble.

CHAPTER V

FREEDOM TO WORSHIP GOD

In the autumn of 1883 the Maréchale suddenly leapt into fame as a latter-day Portia, brilliantly and successfully pleading in a Swiss law-court, before the eyes of Europe, the sacred cause of civil and religious liberty. The land of Tell, the oldest of modern republics, has always been regarded as a shrine of freedom. It has shown itself hospitable to all kinds of ideas, even the newest, the strangest, the most anti-Christian, the most anti-social. There is a natural affinity between free England and free Switzerland.

"Two Voices are there; one is of the sea,One of the mountains; each a mighty Voice:In both from age to age thou didst rejoice;They were thy chosen music, Liberty."

In the "Treaty of Friendship" between Great Britain and Switzerland, drawn up in 1855, it was agreed that "the subjects and citizens of either of the two contracting parties shall, provided they conform to the laws of the country, be at liberty, with their families, to enter, establish themselves, reside and remain in any part of the territories of the other." Yet the presence of a few English evangelists in Switzerland evoked a storm of persecution in which the first principles of religious liberty were as much violated as ever they had been in the days of the Huguenots.

When the Maréchale and some comrades accepted an urgent invitation to Switzerland, she little thought that she would be the heroine of an historical trial. She went to preach the gospel. She observed the laws of the land, and respected the religious susceptibilities of its people. When she entered Geneva, she published only one poster, and that after it had been duly visé; she allowed no processions, banners or brass bands in the streets. Her only crime was that she sought to gain the ears of those who never entered a place of worship, and that she marvellously succeeded.

If good order was not always maintained at her meetings, it was not her fault, but that of the authorities who refused to do their duty. History repeats itself. As in ancient Thessalonica during the visit of St. Paul, so in modern Geneva, some citizens, "moved with jealousy, took unto themselves certain vile fellows of the rabble, and gathering a crowd set the city on an uproar." The ringleaders of the disturbance were paid by noted traffickers in vice, who were themselves often seen in the meetings inciting the audience to riot. One of the first converts, a student, confessed that he had got twenty francs a night, and as much whisky as he could drink, to make a row.

The Department of Justice and Police chanced at that time to have as its president a Councillor of State, M. Heridier, who thought it right not to punish the offenders but to banish their victims. In a sitting of the Grand Council he said, "We have been petitioned to call out a company of gendarmerie to protect these foreigners, and to prevent brawls and rows. I will not consent to take such a step. There are already eight police agents in these places every evening who have a very hard time of it.... These agents might be doing more useful work elsewhere, and I am just about to withdraw them." That meant handing over the strangers to the tender mercies of the mob. It was a gross breach of the laws of hospitality and chivalry as well as of the constitution of a free country. The city of Calvin did not know the day of its visitation.

The Maréchale and her comrades began their meetings in the Casino on December 22, 1882. The hall was crowded, and soon there was raging a great battle between the powers of light and darkness. A disturbance had evidently been organised. A band of students in coloured caps, who had come early and taken possession of the front of the galleries and other prominent positions, were on their worst behaviour. The first hymn was interrupted by cries and ribald songs, and the prayer which followed was almost drowned. But the Maréchale was never more calm and confident than when facing such music. At every slight lull in the storm, she uttered, in clear, penetrating tones, some pointed words which pierced many a heart. Within an hour she not only had subdued her audience but was inviting those who desired salvation to come forward to the penitent form. Scoffers of half an hour ago left their places, trembling under the sense of guilt, and as they knelt down the Maréchale sang, in soft notes, the hymn:

Reviens, reviens, pauvre pécheur,Ton Père encore t'attend;Veux-tu languir loin du bonheur,Et pécher plus longtemps?O! reviens à ton Sauveur,Reviens ce soir,Il veut te recevoir,Reviens à ton Sauveur!

A strange influence stole over the meeting, hushing the crowd into profound silence, and the Spirit did His work in many hearts.

The Maréchale conducted a similar service the following night, and on Christmas Eve she faced an audience of 3000 in the Salle de la Reformation. Its composition was entirely to her mind, for she was never so inspired with divine pity and power as when she was confronting the worst elements of a town. The theatres, the cabarets, the dancing saloons, the drinking dens, and the rendezvous of prostitution had poured their contents into the hall. Socialists who had found refuge in Geneva—men of many nationalities—came en masse. A large part of the audience were so entirely strangers to the idea of worship or of a Divine Being, that the sound of prayer called forth loud derisive laughter, with questions and cries of surprise and scorn.

But the soldiers of Christ, clad in armour of light, were more than a match for the powers of darkness. Many a winged word found its mark, and the after-meeting in the smaller hall, into which three hundred were crowded, was pervaded by a death-like stillness, in which many sought and found salvation. Some of the ringleaders of the disturbance had pushed their way into this room; but they remained perfectly quiet, evidently subdued and over-awed, with an expression on their faces of intense interest, which showed that they felt they were in presence of a reality in religion which they had not before encountered. The Maréchale sang her own hymn "Je viens à Toi, dans ma misère," and many joined in the chorus:

Ote tous mes péchés!Agneau de Dieu, je viens a Toi,Ote tous mes péchés.

One of those who were melted by the words wrote: "I was like the demoniac of Gadara. I may say I was possessed; I was chained for fifteen years to a frightful life.... It was then that you came. I was at first astonished; then remorse seized me. Then followed a frightful torment in my soul—a real hell. I resolved to put an end to it one way or another. Yet I thought I would go and hear you once more. I had been in darkness and anguish since the day of the first meeting. No word had I been able to recall of that day's teaching, except the words of the sacred song 'Ote tous mes péchés' (Take all my sins away). These sounded in my heart and brain through the day and the sleepless night—these and these only. Bowed down with grief and despair, again I came to the Reformation Hall, and to the after-meeting. The first sounds which fell on my ear were again those very words, 'Ote tous mes péchés,' and then you spoke on the words, 'Though your sins be as scarlet, they shall be white as snow'; you seemed to speak to me alone, to regard me alone—and I felt it was God who had sent me there to hear those words."

Hundreds of such letters were written. Evidence came from all sides of blessing received in many homes, of wild sons reclaimed, of drunkards and vicious men transformed by the power of God, of light and joy brought into families over which a cloud had hung. Not only anarchists and prodigals, but students of theology and the children of pastors had their lives transformed. In a meeting for women only, at which 3000 were present, the daughter of Pastor Napoleon Roussel began the new life. Her brother had been one of the converts in the first meeting in the Reformation Hall. Mlle. Roussel was to be the Maréchale's secretary for five years, and accompany her in a great American tour. A divinity student who attended a "night with Jesus" on New Year's Eve, wrote: "I passed a long night of watch, which I shall never forget. Since then I am ever happy, and can say 'Glory to God' every hour of the day."

But as the tide of Divine blessing rose, the tide of human hatred also rose, and in the beginning of February the "exercises" of the Army were by Cantonal decree forbidden. A week later, the Maréchale, with a young companion, Miss Maud Charlesworth, now Mrs. Gen. Ballington Booth, was expelled from the Canton of Geneva. During her six weeks in the city she had been used to bring about probably the greatest revival which it had witnessed since the days of the Reformers.

One of the most eminent lawyers of Geneva, Edmond Pictet, who had himself been greatly blessed during those stirring weeks, helped her to draw up an Appeal (Recours) to the Grand Council. He found, however, that she needed but little help, and often remarked that with the warm heart of an evangelist she combined the lucid intelligence of an advocate. When the Council of State had deputed two or three of its members to hear her on the subject of her Appeal, she came back to Geneva under a safe-conduct to meet them. In the course of the interview, at which the British Consul in the city was present, the leading Councillor said, "You are a young woman; it is not in accordance with our ideas and customs that young women should appear in public. We are scandalised (froissés) by it." The rejoinder which he received was so remarkable a defence of "the Prophesying of Women" that we give it in full.

"Listen to me, I beg of you, sir. It is contrary, you tell me, to your sense of what is right and becoming that young women should preach the Gospel. Now, if Miss Charlesworth and I had come to Geneva to act in one of your theatres, I have no doubt we should have met with sympathy and approval from your public. We could have sung and danced on your stage; we could have dressed in a manner very different from, and much less modest than, that in which you see us dressed; we could have appeared before a miscellaneous audience, men and women, young and old, and of every class; members of the Grand Council, M. Herdier himself and others, would have come to see us act; we should have got money; Geneva would have paid ungrudgingly in that case; and you would all have sat and approved; you would have clapped your hands and cheered us; you would have brought your wives and daughters to see us, and they also would have applauded. There would have been nothing to froisser you, no immorality in all that, according to your ideas and customs. The noise (bruit) we should have thus made would not have caused our expulsion. But when women come to try and save some of the forty or fifty thousand of your miserable, scoffing, irreligious population who never enter any place of worship, when they come with hearts full of pity and love for the ignorant and sinful, and stand up to tell the glad tidings of salvation to these rebels, this mob, among whom many accept the tidings with eager joy—then you cry out that this is unseemly and immodest. You would not bring your wives and daughters to hear us speak of Jesus, though you would bring them to hear us if we danced and sang upon the stage of your theatre. Now you have expelled us; but still there are those multitudes in Geneva who are dark, lost, unsaved; and you know it. There they are; they exist. What will you do with them? Say—what will you do? Are they not a danger? Does not their lost condition cry out against you?"

The Councillor was not only silenced, but sank into his chair in a state of temporary lapse. For the moment, at least, the reality of the picture presented to him had touched his heart.

Nevertheless the Maréchale's Appeal was rejected, and M. Pictet wrote to her: "The wretched storm of anger and prejudice which you witnessed and which your friends deplore so much, has not blown over by any means. I, for one, despair of ever seeing my fellow-citizens properly understand what religious liberty and respect of other people's opinion mean,—therefore the only course left to the Army seems to be the one indicated in St. Matthew x. 23! You have done your duty, you cannot be expected to do more than Paul and Barnabas did (Acts xiii. 51)."