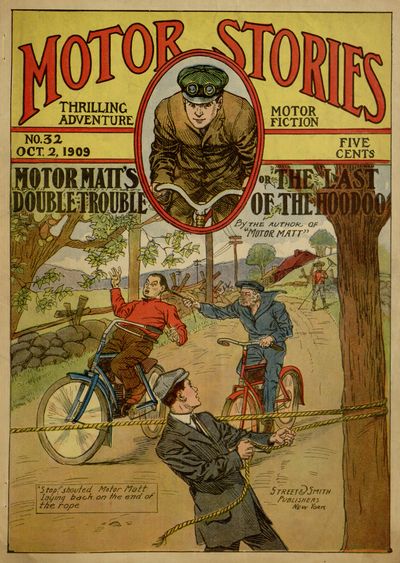

Title: Motor Matt's Double Trouble; or, The Last of the Hoodoo

Author: Stanley R. Matthews

Release date: November 15, 2016 [eBook #53533]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, Demian Katz and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (Images

courtesy of the Digital Library@Villanova University

(http://digital.library.villanova.edu/))

|

THRILLING ADVENTURE |

MOTOR FICTION |

|

No. 32 OCT. 2, 1909. |

FIVE CENTS |

|

MOTOR MATT'S DOUBLE-TROUBLE | or THE LAST OF THE HOODOO |

| By the author of "Motor Matt" | |

|

Street & Smith Publishers New York |

| MOTOR STORIES | |

| THRILLING ADVENTURE | MOTOR FICTION |

Issued Weekly. By subscription $2.50 per year. Copyright, 1909, by Street & Smith, 79-89 Seventh Avenue, New York, N. Y.

| No. 32. | NEW YORK, October 2, 1909. | Price Five Cents. |

Motor Matt's Double Trouble

OR,

THE LAST OF THE HOODOO.

By the author of "MOTOR MATT."

CHAPTER I. THE RED JEWEL.

CHAPTER II. ANOTHER END OF THE YARN.

CHAPTER III. SHOCK NUMBER ONE.

CHAPTER IV. SHOCKS TWO AND THREE.

CHAPTER V. A HOT STARTER.

CHAPTER VI. M'GLORY IS LOST—AND FOUND.

CHAPTER VII. "POCKETED."

CHAPTER VIII. SPRINGING A "COUP."

CHAPTER IX. MOTOR MATT'S CHASE.

CHAPTER X. THE CHASE CONCLUDED.

CHAPTER XI. A DOUBLE CAPTURE.

CHAPTER XII. ANOTHER SURPRISE.

CHAPTER XIII. BAITING A TRAP.

CHAPTER XIV. HOW THE TRAP WAS SPRUNG.

CHAPTER XV. BACK TO THE FARM.

CHAPTER XVI. CONCLUSION.

HUDSON AND THE NORTHWEST PASSAGE.

THE DEATH BITE.

MIGRATION OF RATS.

SOME GREAT CATASTROPHES.

Matt King, otherwise Motor Matt.

Joe McGlory, a young cowboy who proves himself a lad of worth and character, and whose eccentricities are all on the humorous side. A good chum to tie to—a point Motor Matt is quick to perceive.

Tsan Ti, Mandarin of the Red Button, who continues to fall into tragic difficulties, and to send in "four-eleven" alarms for the assistance of Motor Matt.

Sam Wing, San Francisco bazaar-man, originally from Canton, and temporarily in the employ of Tsan Ti. By following his evil thoughts he causes much trouble for the mandarin, and, incidentally, for the motor boys.

Philo Grattan, a rogue of splendid abilities, who aims to steal a fortune and ends in being brought to book for the theft of a motor car.

Pardo, a pal of Grattan.

Neb Hogan, a colored brother whose mule, stolen by Sam Wing, plays a part of considerable importance. Neb himself engineers a surprise at the end of the story, and goes his way so overwhelmed with good luck that he is unable to credit the evidence of his senses.

Banks and Gridley, officers of the law who are searching for the stolen blue motor.

Boggs, a farmer who comes to the aid of Motor Matt with energy and courage.

Bunce, a sailor with two good eyes who, for some object of his own, wears a green patch and prefers to have the public believe he is one-eyed. A pal of Grattan, who is caught in the same net that entangles the rest of the ruby thieves.

THE RED JEWEL.

Craft and greed showed in the eyes of the hatchet-faced Chinaman. He seemed to have been in deep slumber in the car seat, but the drowsiness was feigned. The train was not five minutes out of the town of Catskill before he had roused himself, wary and wide-awake, and looked across the aisle. His look and manner gave evidence that he was meditating some crime.

It was in the small hours of the morning, and the passenger train was rattling and bumping through the heavy gloom. The lights in the coach had been turned low, and all the passengers, with the exception of the thin-visaged Celestial, were sprawling in their uncomfortable seats, snoring or breathing heavily.

Across the aisle from this criminally inclined native of the Flowery Kingdom was another who likewise hailed from the land of pagodas and mystery; and this other, it could be seen at a glance, was a person of some consequence.

He was fat, and under the average height. Drawn down over his shaven head was a black silk cap, with a gleaming red button sewn in the centre of the flat crown. From under the edge of the cap dropped a queue of silken texture, thick, and so long that it crossed the Chinaman's shoulder and lay in one or two coils across his fat knees.

Yellow is the royal color in China, and it is to be noted that this Celestial's blouse was of yellow, and his wide trousers, and his stockings—all yellow and of the finest Canton silk. His sandals were black and richly embroidered.

From the button and the costume, one at all informed of fashions as followed in the country of Confucius might have guessed that this stout person was a mandarin. And that guess would have been entirely correct.

To go further and reveal facts which will presently become the reader's in the logical unfolding of this chronicle, the mandarin was none other than Tsan Ti, discredited guardian of the Honam joss house, situated on an island suburb of the city of Canton. He of the slant,[Pg 2] lawless gleaming eyes was Sam Wing, the mandarin's trusted and treacherous servant.

A Chinaman, like his Caucasian brother, is not always proof against temptation when the ugly opportunity presents itself at the right time and in the right way. Sam Wing believed he had come face to face with such an opportunity, and he was determined to make the most of it.

Sam Wing was a resident of San Francisco. He owned a fairly prosperous bazaar, and, once every year, turned his profits into Mexican dollars and forwarded the silver to an uncle in Canton for investment in the land of his birth. Some day Sam Wing cherished the dream of returning to Canton and living like a grandee. But wealth came slowly. Now, there in that foreign devil's choo-choo car such a chance offered to secure unheard-of riches that Sam Wing's loyalty to the mandarin, no less than his heathen ideas of integrity, were brushed away with astounding suddenness.

Tsan Ti slept. His round head was wabbling on his short neck—rolling and swaying grotesquely with every lurch of the train. The red button of the mandarin's cap caught the dim rays of the overhead lamps and threw crimson gleams into the eyes of Sam Wing. This flashing button reminded Sam Wing of the red jewel, worth a king's ransom, which the mandarin was personally conveying to San Francisco, en route to China and the city of Canton.

Already Sam Wing was intrusted with the mandarin's money bag—an alligator-skin pouch containing many oblong pieces of green paper marked with figures of large denomination. The money was good, what there was of it, but that was not enough to pay for theft and flight. Sam Wing's long, talon-like fingers itched to lay hold of the red jewel.

With a swift, reassuring look at the passengers in the car, Sam Wing caught at the back of the seat in front and lifted himself erect. He was not a handsome Chinaman, by any means, and he appeared particularly repulsive just at that moment.

Hanging to the seat, he steadied himself as he stepped lightly across the aisle. Another moment and he was at the mandarin's side, looking down on him.

Tsan Ti, in his dreams, was again in Canton. Striding through the great chamber of the Honam joss house, he was superintending the return of the red jewel to the forehead of the twenty-foot idol, whence it had been stolen.

While the mandarin dreamed, Sam Wing bent down over him and, with cautious fingers, unfastened the loop of silk cord that held together the front of the yellow blouse. The rich garment fell open, revealing a small bag hanging from the mandarin's throat by a chain.

Swiftly, silently, and with hardly a twitch of the little bag, two of Sam Wing's slim, long-nailed fingers were inserted, and presently drew forth a resplendent gem, large as a small hen's egg.

A gasping breath escaped Sam Wing's lips. For a fraction of an instant he hesitated. What if his ancestors were regarding him, looking out of the vastness of the life to come with stern disapproval? A Chinaman worships his ancestors, and the shades of the ancient ones of his blood have a great deal to do with the regulating of his life. What were Sam Wing's forefathers thinking of this act of vile treachery?

The thief ground his teeth and, with trembling hands, stowed the red jewel in the breast of his blouse. He started toward the rear door of the car—and hesitated again.

Sam Wing was a Buddhist, as the Chinese understand Buddhism, wrapping it up in their own mystic traditions. This red jewel had originally been stolen from a great idol of Buddha. In short, the jewel had been the idol's eye, and the idol, sightless in the Honam joss house, was believed to be in vengeful mood because of the missing optic. The idol had marshalled all the ten thousand demons of misfortune and had let them loose upon all who had anything to do with the pilfering of the sacred jewel.

Who was Sam Wing that he should defy these ten thousand demons of misfortune? How could he, a miserable bazaar man, fight the demons?

But his skin tingled from the touch of the red jewel against his breast. He would dare all for the vast wealth which might be his in case he could "get away with the goods."

Closing his eyes to honor, to the ten thousand demons, to every article of his heathen faith, he bolted for the rear of the car. Opening the door, he let himself out on the rear platform. A lurch of the car caused the door to slam behind him.

Meanwhile Tsan Ti had continued his delightful dreaming. His subconscious mind was watching the priests as they worked with the red jewel, replacing it in the idol's forehead. The hideous face of the graven image seemed to glow with satisfaction because of the recovery of the eye.

The priest, at the top of the ladder, fumbled suddenly with his hands. The red jewel dropped downward, with a crimson flash, struck the tiles of the floor, and rolled away, and away, until it vanished.

A yell of consternation burst from the mandarin's lips. He leaped forward to secure the red jewel—and came to himself with his head aching from a sharp blow against the seat back in front.

He straightened up, and the alarm died out of his face. After all, it was only a dream!

"Say!" cried a man in the seat ahead, turning an angry look at Tsan Ti. "What you yellin' for? Can't a heathen like you let a Christian sleep? Huh?"

"A million pardons, most estimable sir," answered Tsan Ti humbly. "I had a dream, a bad dream."

"Too much bird's-nest soup an' too many sharks' fins for supper, I guess," scowled the man, rearranging himself for slumber. "Pah!"

Tsan Ti peered across the aisle. The seat occupied by his servant, Sam Wing, was vacant. Sam Wing, the mandarin thought, must have become thirsty and gone for a drink.

The mandarin heaved a choppy sigh of relief. How real a dream sometimes is! Now, if he——

His hand wandered instinctively to the breast of his blouse, and he felt for the little lump contained in the bag suspended from his throat.

He could not feel it. Pulling himself together sharply Tsan Ti used both hands in his groping examination.

Then he caught his breath and sat as though dazed. A slow horror ran through his body. His blood seemed congealing about his heart, and his yellow face grew hueless.

The red jewel was gone! The front of his blouse was open!

Then, after his blunted wits had recovered their wonted sharpness, Tsan Ti leaped for the aisle with another yell.

"Say," cried the man in the forward seat, lifting himself wrathfully, "I'll have the brakeman kick you off the train if you don't hush! By jing!"

The mandarin began running up and down the aisle of the car, wringing his fat hands and yelling for Sam Wing. He said other things, too, but it was all in his heathen gibberish and could not be comprehended.

By then every person in the car was awake.

"Crazy chink!" shouted the man who had spoken before. "He's gone dotty! Look out for him!"

At that moment the train lumbered to a halt and the lights of a station shone through the car windows. The brakeman jammed open the door and shouted a name.

"Motor Matt!" wailed Tsan Ti. "Estimable friend, come to my wretched assistance!"

"Here, brakeman!" cried the wrathful passenger who had already aired his views, "take this slant-eyed lunatic by the collar of his kimono and give him a hi'st into the right of way. Chinks ought to be carried in cattle cars, anyhow."

Tsan Ti, however, did not wait to be "hoisted into the right of way."

With a final yell, he flung himself along the aisle and out the rear door, nearly overturning the astounded brakeman. Once on the station platform, he made a bee line for the waiting room and the telegraph office.

There was but one person in all America in whom the mandarin had any confidence, but one person to whom he would appeal. This was the king of the motor boys, who, at that moment, was in the town of Catskill.

ANOTHER END OF THE YARN.

On the same night this Oriental treachery manifested itself aboard the train bound north through the Catskills, a power yacht dropped anchor below the town of Catskill.

There was something suspicious about this motor yacht. She carried no running lights, and her cabin ports were dark as Erebus. She came to a halt silently—almost sullenly—and her anchor dropped with hardly a splash. A tender was heaved over the side, and four men got into it and were rowed ashore by one of their number. When the tender grounded, three of the passengers got out. One of them turned to speak to the man who remained in the boat.

"Leave the tender in the water, when you get back to the Iris, Pierson. If the tender is wanted here, a light will be shown."

"All right, Grattan," answered the man in the boat, shoving off and rowing noiselessly back to the yacht.

"Hide the lantern in that clump of bushes, Bunce," went on Grattan.

"Ay, ay, messmate," answered the person addressed as Bunce.

"Look here, Grattan," grumbled the third member of the party, "Motor Matt has cooked our goose for us, and I'll be hanged if I can see the use of knocking around the town of Catskill."

"There are a lot of things in this world, Pardo," returned Grattan dryly, "that are advisable and that you haven't sense enough to see."

Pardo muttered wrathfully but indistinctly.

"Now," proceeded Grattan, "this is the way of it: We got Motor Matt and his chum, McGlory, aboard the Iris—lured them there on the supposition that Tsan Ti had sent Motor Matt the red jewel to keep safely for him for a time. Motor Matt and McGlory walked into our trap. We got the red jewel and put the two boys ashore some fifteen or twenty miles below here. Half an hour later I put the supposed ruby to some tests and found it was counterfeit——"

"Are you sure the ruby you stole from the Honam joss house was a true gem?"

"Yes. Tsan Ti sent Motor Matt a counterfeit replica for the purpose of getting us off the track. Motor Matt and McGlory will take the first train for Catskill from the place where we put them ashore. We'll lie in wait for them on the path they must take between the railroad station and their hotel. It's a dark night, few passengers will arrive at this hour, and we can recapture the two motor boys and take them back to the Iris."

"What good will that do?" demurred Pardo. "Motor Matt hasn't the real stone—Tsan Ti must have that."

"I'll find out from Motor Matt where Tsan Ti is," said Grattan, between his teeth, "and then I'll flash a message to the mandarin that he must give up the real gem, or Motor Matt will suffer the consequences!"

"You can't mean," gasped Pardo, in a panic, "that you will——"

"It's a bluff, that's all," snapped Grattan. "It will scare the mandarin out of his wits. Have you hid the lantern, Bunce?" he demanded, as the other member of the party came close.

"Ay, Grattan," was the reply. "First bunch of bushes close to where we came ashore."

"All right; come on, then. I've figured out what train Motor Matt and Joe McGlory will catch, and it should soon be at the depot."

With Grattan in the lead, the party scrambled up the slope through the darkness, passed some ice houses, crossed a railroad track, and finally came to a halt in a lonely part of the town, near the walk leading from the railroad station to the business street and the hotels. A billboard afforded them a secure hiding place.

Grattan had figured the time of the train pretty accurately. He and his companions waited no longer than five minutes before the "local" drew to a halt at the station.

"If those boys are not on the train," muttered Pardo, "then we're fooled again. Confound that Motor Matt, anyhow!"

"He has my heartiest admiration," returned Grattan, "but I'm not going to match wits with him and call myself beaten. Hist!" he added abruptly, "here come two people—and maybe they're the ones we're looking for. Mind, both of you, and don't make a move till I give the word."

Breathlessly the three men waited. Footsteps came slowly up the walk and voices could be heard—voices which were recognized as belonging to the motor boys.

"Well, pard," came the voice of McGlory, "New York[Pg 4] for ours in the morning. Tsan Ti, with the big ruby, is on the train, bound for China and heathen happiness, Grattan has the bogus stone and is making himself absent in the Iris, and you and I are rid of the hoodoo at last, and have fifteen hundred to the good. That's what I call——"

By then the two lads had passed the billboard and were so far away that spoken words could not be distinguished. And Grattan had given no word for an attack!

"What's the matter with you, Grattan?" whispered Pardo. "They're too far off for us to bag them now."

"We're not going to bag them." Grattan was a man of quick decisions. "We've changed our plans."

While the other two mumbled their surprise and asked questions, Grattan had taken pencil, notebook, and an electric torch from his pocket. Snapping on the torch, he handed it to Bunce.

"Put a stopper on your jaw tackle and hold that," said he crisply.

Then he wrote the following:

"Conductor, Local Passenger, North Bound: Fat Chinaman, answering to name of Tsan Ti and claiming to be mandarin, on your train. He's a thief and has stolen big ruby called Eye of Buddha. Put him off train in charge of legal officer, first station after you receive this. Answer.

James Philo, Detective."

"This is a telegram," said Grattan, and read it aloud for the benefit of his two companions. "You'll take it down to the railroad station, Pardo," he went on, "and have it sent at once to the nearest point that will overtake the train Matt and McGlory just got off of. Bunce and I will wait here, and you stay in the station till you receive an answer."

"But how do you know Tsan Ti is on that train?" asked Pardo.

"Didn't you hear what was said when the motor boys passed us?"

"But nothing was said about the mandarin being on that particular train."

"I'm making a guess. If the conductor replies that no such chink is on the train, then my guess is wrong. If he answers that the chink was there, and that he has put him off, red jewel and all, into the hands of the legal authorities, then James Philo Grattan will play the part of James Philo, detective, and fool these country authorities out of their eye teeth—and, incidentally, out of the Eye of Buddha."

The daring nature of Grattan's hastily formed plan caused Pardo and Bunce to catch their breath. Grattan was a fugitive from the law, and yet here he was making the law assist him in stealing the red jewel for the second time!

"You're a wonder," murmured Pardo, "if you can make that game work."

"Trust me for that, Pardo. Now you hustle for the railroad station and get that message on the wires. Hurry back here as soon as you receive an answer."

Pardo took the paper and made off down the slope. He was gone three-quarters of an hour—a weary, impatient wait for Bunce, but passed calmly by Grattan.

When Pardo returned he came at a run.

"Your scheme's no good, Grattan!" were his first breathless words.

"Why not?" demanded Grattan. "Wasn't Tsan Ti on the train?"

"Yes—and another chink, as well. Fat Chinaman, though, jumped off at Gardenville, first station north of Catskill. Here, read the conductor's message for yourself."

Grattan, still cool and self-possessed, switched the light into his torch and read the following:

"Two Chinamen, one answering description, came through on train from Jersey City. Fat Chinaman jumped off at Gardenville, although had ticket reading Buffalo. Don't know what became of other Chinaman. Two young men boarded train River View, talked with fat Chinaman, got off Catskill.

Conductor."

Grattan must have been intensely disappointed, but he did not give rein to his temper. While Bunce spluttered and Pardo swore under his breath, Grattan was wrapped in profound thought.

"We'll have to change our plans again," he observed finally. "We gave over the idea of capturing Motor Matt and McGlory for the purpose of getting Tsan Ti held by the authorities as a thief; now we've got to give that up. Why did Tsan Ti get off the train at Gardenville when he was going to Buffalo? It was an Oriental trick to pull the wool over my eyes. The mandarin is afraid of me. We must proceed at once to Gardenville before Tsan Ti has a chance to get out of the town."

"How are we going to get to Gardenville?" demanded Pardo. "If we take the Iris——?"

"We won't."

"If we walk——"

"We won't do that, either. We'll take an automobile. It may be, too, that our motor cycles will come in handy. You go down to the bank, Pardo, signal the yacht, and have Pierson bring the two machines ashore. While you're about that, Bunce and I will visit the garage and borrow a fast machine. You know these hills?"

"As well as I do my two hands."

"On your way to the Iris I'll give you something to leave at the hotel for Motor Matt."

Grattan did some more scribbling on a blank sheet of his notebook; then, tearing out the sheet, he wrapped it around a small object and placed both in a little box with a sliding cover.

"They may recognize me at the hotel," protested Pardo.

"I don't think so. It will do me good to have you leave this, anyhow. I don't want Motor Matt to think that I was fooled very long by that bogus ruby. If we're quick, Pardo, we're going to catch Tsan Ti before he can leave Gardenville. And when we nab the mandarin we secure the ruby."

Grattan was a master rogue, and not the least of his shining abilities was his readiness in adjusting himself to changing circumstances.

Fate, in the present instance, had conspired to place him on the wrong track—but he was following the course with supreme confidence.

SHOCK NUMBER ONE.

When Motor Matt and Joe McGlory dropped off that "local" passenger train at the Catskill station they had just finished a series of strenuous experiences. These had to do with the great ruby known as the Eye of Buddha. A cunning facsimile of the gem had been sent by Tsan Ti to Matt, by express, with a letter desiring him to take care of the ruby until the mandarin should call for it. This responsibility, entirely unsought by the king of the motor boys, plunged him and his cowboy pard into a whirl of adventures, and ended in their being decoyed aboard the Iris. Here the ruby was taken from Matt by force—Grattan, who secured it, not learning until some time later that the object Matt had been caring for was merely a base counterfeit of the original gem. And Matt and McGlory did not find this out until they caught the train at Fairview, when they discovered that Tsan Ti and Sam Wing were aboard.

The twenty-mile ride from Fairview to Catskill with the mandarin proved quite an eye opener for the motor boys. They learned how Tsan Ti had deliberately set Grattan on their track to recover the bogus ruby, while he—Tsan Ti—made his escape with the real gem.

This part of the mandarin's talk failed to make much of a "hit" with Matt and McGlory. The mandarin had used them for his purposes in a particularly high-handed manner, keeping them entirely in the dark regarding the fact that the stone intrusted to Matt was a counterfeit.

Although the boys parted in a friendly way with the mandarin on leaving the train at Catskill, yet they nevertheless remembered their grievance and were heartily glad to think that they were done for all time with Tsan Ti and his ruby.

Very often it happens that when we think we are done with a thing we have reckoned without taking account of a perverse fate. This was the case with the motor boys with reference to Tsan Ti and the Eye of Buddha.

While they were climbing the slope from the railroad station to their hotel, glad of the prospect of securing a little much-needed rest, only a few chance remarks by McGlory prevented them from having an encounter with Grattan, Pardo, and Bunce, who were lurking beside the walk. And at that same moment the faithless Sam Wing was engineering his stealthy theft in the darkened passenger coach.

So stirring events were forming, all unheeded by the boys.

Upon reaching the hotel they proceeded immediately to the room which they occupied, hastily disrobed, and crept into their respective beds. In less than five minutes the room was resounding with McGlory's snores. Matt remained awake long enough to review the events of the day and to congratulate himself that he and his cowboy pard were finally rid of the "hoodoo" gem and the "hoodoo" Chinaman who had been looking for it. Then the king of the motor boys himself fell asleep.

It was McGlory's voice that aroused Matt.

"Sufferin' thunderbolts!" Matt awoke with a start and turned his eyes toward the other side of the room. The cowboy was sitting up in bed. "Talk about your shocking times, pard," he went on, "why, I've been jumping from one shock into another ever since I hit this mattress. Thought I was chased by a blind idol, twenty feet high, and sometimes that idol looked like Grattan, sometimes it was a dead ringer for Tsan Ti, and sometimes it was its own wabble-jawed, horrible self. Woosh! And listen"—McGlory's eyes grew wide and he became very serious—"the idol that chased me had red hair!"

"What difference does that make, Joe?" inquired Matt, observing that the sun was high and forthwith tumbling out of bed.

"What difference does it make!" gasped McGlory. "Speak to me about that! Don't you know Matt, that whenever you dream about a person with red hair, trouble's on the pike and you've got up your little red flag?"

"Oh, gammon!" grunted Matt. "Pile out and get into your clothes, Joe. We're taking the eleven a. m. boat for the big town, and we haven't any too much time to make our 'twilight,' help ourselves to a late breakfast, and amble down to the landing."

"Hooray!" cried McGlory, forgetting his dream in the prospect called up by his chum's words. "We're going to have the time of our lives in New York, pard! All I hope is that nothing gets between us and that eleven a. m. boat. Seems like we never make a start for down the river but Johnny Hardluck comes along, jolts us with an uppercut, and faces us the wrong way. Look here, once."

"Well?"

"If you get a letter from Tsan Ti, promise me to say 'manana' and give it the cut direct."

"What chance is there of our receiving a letter from the mandarin? He's on his way West with the Eye of Buddha, and Grattan is on his way no one knows where with a glass imitation. Both of them are satisfied, and I guess you and I, Joe, haven't any cause for complaint. The mandarin is too busy traveling to write any letters."

"Well," insisted McGlory, "give me your solemn promise you won't pay any attention to a letter from the mandarin if you receive one. If you're so plumb certain he won't write, why not promise?"

"It's a go," laughed Matt, "if that will make you feel any easier in your mind."

"It does, a heap. I'd rather have measles than another attack of mandarinicutis, complicated with rubyitis, and——"

"Oh, splash!" interrupted Matt. "We've been well paid for all the time we were ailing with those two troubles. Give your hair a lick and a promise, and let's go down to breakfast. They'll be ringing the last bell on us if we wait much longer."

"Lead on, Macduff!" answered McGlory, throwing himself around in the air and then striking a pose, with one arm up, like Ajax defying the lightning. "Remember Monte Cristo like that, pard?" he asked. "'The world is mine!' That's how I feel. Us for New York, with fifteen hundred of the mandarin's dinero in our clothes! Oh, say, I'm a brass band and I've just got to toot!"

The cowboy "tooted" all the way downstairs and into the office; then, as they passed the desk on their way to the dining room, the rejoicing died on the cowboy's lips.

"Just a minute, Motor Matt!" called the clerk, leaning over the desk and motioning.

"Lightning's going to strike," muttered McGlory; "I can see it coming."

He followed Matt to the desk. As they lined up there, the clerk fished a small box out of the office safe.

"This was left here for you last night, Matt," went on the clerk. "I was told to hand it to you this morning by the night clerk when he went off duty."

The little box was placed on the counter. Matt and McGlory stared at it.

That was not the first time they had seen that small receptacle. With the counterfeit ruby inside, it had first come into Matt's hands by express, direct from Tsan Ti; then, by a somewhat devious course of events, it had gone into the possession of Philo Grattan.

Why should Grattan have returned the box to Matt? How could he have returned it when, as Matt and McGlory believed, he was at that very moment hurrying to get out of the country and escape the law?

"Shock number one," shuddered McGlory.

"Not much of a shock about this—so far," returned Matt, picking up the box.

"Wait till you see what's inside."

"We'll open it in the dining room," and Matt turned away.

"I'll bet a bowl of birds'-nest soup against a plate of sharks' fins it's going to spoil your breakfast."

They went in and took their usual places at one of the tables. All the other guests had breakfasted, and the motor boys had the big dining room—with the exception of two or three waiters—wholly to themselves.

"Open it quick," urged McGlory.

Matt sawed through the string with his knife, pulled out the lid of the box, and dropped a gleaming red object on the tablecloth.

"Sufferin' snakes!" exclaimed McGlory. "The Eye of Buddha, or I'm a Piute! How in blazes did old Tsan Ti get the thing back to us? When I saw that last it was in a silk bag around the mandarin's neck."

"It can't be the Eye of Buddha, Joe," said Matt. "It looks to me more like the bogus gem than the real one."

"How can you tell the difference?"

"From the fact that the real stone could not by any possibility get into our hands again."

"Neither could the bogus gem—if it's where we think it is."

"I guess here's something that will explain," and Matt drew a piece of paper from the box.

"Who's it from?" queried McGlory, in a flutter.

"From Grattan," answered Matt grimly. "Listen," and he read:

"'Motor Matt: You don't know what a tight squeak you and McGlory had to-night—not aboard the Iris, but after you were put ashore. Pray accept the inclosed piece of glass with my compliments. I don't think you knew, any more than I did, that it was counterfeit. If Tsan Ti gets into any more difficulties, you take my advice and let him weather them alone.

Grattan.'"

"Shocked?" muttered McGlory. "Why, I feel as though somebody had hit me with a live wire. So Grattan found out the ruby was an imitation! And he found out in time to send that back to you last night! Say, that fellow's the king bee of all the crooks that ever lived. Present the jewel to one of these darky waiters, and let's you and I get busy with the ham and eggs. I'm glad we're for New York by the eleven-o'clock boat, and that the mandarin isn't worrying us any more."

The cowboy threw the box under the table, and would have reached for the gleaming bit of glass had not Matt grabbed it first and dropped it into his pocket.

SHOCKS TWO AND THREE.

The motor boys were very much in the dark concerning Philo Grattan's movements and intentions.

"He was right," observed Matt, referring to Grattan's note, "when he said I was in the dark as much as he was concerning that piece of glass. He wasn't fooled very long."

"There's good advice in that note," said McGlory, who was beginning to have apprehensions that he and Matt were not yet done with the Eye of Buddha. "I mean where he says that if the mandarin gets into any more difficulties we'll be wise to let him get out of them alone the best way he can."

"That's more than a piece of advice, Joe. If I catch the true meaning, it's a threat."

McGlory at once saw a light in the general gloom.

"Then, if it's a threat, pard, Grattan must be ready to make another try for the Eye of Buddha!"

"That's the way it strikes me."

"But what can Grattan do? Tsan Ti ought to be whooping it up pretty well to the west by now. He's got a good long start of Grattan in the run to 'Frisco."

"What Grattan can do," said Matt reflectively, "is as hard to understand as what he has already done. We know he has discovered that this red jewel is a counterfeit, we know he sent some one here to return the piece of crimson glass to me, and it's a fair inference that he's going to make another attempt to recover the real ruby. How he has managed to do all this, however, or what he can possibly accomplish in overhauling Tsan Ti, is far and away beyond me."

"We're out of it, anyhow," remarked McGlory, with an airy confidence he was far from feeling. "You've promised not to pay any attention to any four-eleven alarms you receive from the mandarin, and I'd feel tolerably comfortable over the outlook if—if——" He paused.

"If what?" queried Matt.

"Why, if I hadn't seen that red-headed idol chasing me in my sleep. I had two good looks at it. One look means trouble, two looks mean double trouble. Call me a Piegan if I ever knew it to fail."

Matt laughed.

"Never trouble trouble," he admonished, "till trouble troubles you."

"Fine!" exclaimed McGlory; "but it's like a good many of these keen old saws—hard to live up to. I'll bet the inventor of that little spiel died of worry in some poorhouse. I'm always on my toes, shading my eyes with my hat brim and looking for miles along the trail of life to see if I can't pick up a little hard luck heading my way. Can't wait till I come company front with it. Well, maybe it's all right. Life would be sort[Pg 7] of tame if something didn't happen now and then to make us ginger up. But we're for New York at eleven o'clock, no matter what happens!"

A few minutes later they finished their breakfast and went out into the office. As Matt pushed up to the desk to ask the amount of his hotel bill, and settle for it, the clerk shoved a yellow envelope at him.

"Telegram, Matt. Just got here."

"Shock two," groaned McGlory, grabbing at the edge of the desk. "Now what? Oh, tell me!"

Matt tore open the envelope, read the message, stared at it, whistled, then read it again.

"Somebody want us to run an air ship or go to sea in a submarine?" palpitated McGlory. "Sufferin' tenterhooks, pard! Stop your staring and whistling, and hand it to me right off the bat."

Matt caught McGlory's arm and conducted him to a corner where there were a couple of easy-chairs.

"It's from the mandarin," he announced.

"Sufferin' chinks!" breathed the cowboy. "Didn't I tell you? Say, didn't I? What's hit him now?"

"I'll read you the message, Joe."

"Go ahead. All I want you to do, pard, is just to remember what you promised me."

"'Esteemed friend,'" read Matt, "'and highly treasured assistant in time of storm——'"

"Speak to me about that!" grunted the disgusted McGlory. "His word box is full of beadwork."

"'Again I call from the bottomless pit of distress,'" continued Matt, "'and from this place named Gardenville announce the duplicity of Sam Wing, who suddenly absented himself from the train with my supply of cash and the Eye of Buddha. Having no money, I have requested of the honorable telegraph company to receive pay from you. If——'"

"He's lost the ruby!" gasped McGlory, "and Sam Wing is the guilty man! Oh, Moses, what a throwdown! Why, I had a notion Sam Wing thought the sun rose and set in Tsan Ti. And Sam Wing lifted the ruby and the mandarin's funds and hot-footed it for parts unknown! Well, well!"

"'If,'" continued Matt, continuing the reading, "'I cannot recover the priceless gem, then nothing is left for me but the yellow cord. Hasten, noble youth, and aid in catching the miserable Sam Wing.' That's all, Joe," finished Matt, with a frown.

"Then drop it in the waste basket and let's settle our bill and start for the landing. It's a quarter to eleven. While you're paying up I'll go to the room after our grips."

The cowboy started impatiently to his feet. Matt continued to sit in his chair, frowning and peering into vacancy.

"Mosey!" urged Joe.

"It seems too bad to turn Tsan Ti down in such cold-blooded fashion," said Matt.

"There you go! That's you! Say, pard, the mandarin thinks he's got a mortgage on you. What's the good of helping a chink who's so locoed he totes a fifty-thousand-dollar ruby around with him rather than hand it over to the express company for transportation? Take it from me, you can keep helping Tsan Ti for the next hundred years, and he'll never get out of the country till he separates himself from the Eye of Buddha and let some one else take the risk of getting it to Canton. Are you going?"

"The poor old duffer," continued Matt, "is always right up in the air when anything goes wrong with him. We know what the safe return of that ruby to the Honam joss house means to him, Joe. The ruler of China has sent him a yellow cord—a royal invitation for him to strangle himself if the ruby is not found and returned to the forehead of the idol."

"Look here," snapped McGlory, "time's getting scarce. Are you going down the river with me, pard, or have I got to go alone?"

Before Matt could answer, a well-dressed man hurried into the lobby from the street and rushed for the desk as though he had something on his mind.

"That's Martin," said Matt, looking at the man.

Martin was proprietor of the local garage and had been of considerable assistance to the motor boys during the first days of their stay in Catskill. It was Martin who owned the two motor cycles which had been stolen from Matt and McGlory by Bunce and a pal. The boys had had to put up three hundred dollars to settle for that escapade, but Tsan Ti had made the amount good.

Martin talked excitedly with the hotel clerk for a moment, and the clerk leaned over the desk and pointed toward the corner where the motor boys had seated themselves. Martin, a look of satisfaction crossing his troubled face, bore down on the corner.

"Look out for shock number three," growled McGlory. "Sufferin' hoodoos! We've taken root here in Catskill, and I'll bet we won't be able to pull out for the rest of our natural lives."

The cowboy, apparently discouraged with the outlook, dropped down into his chair and leaned back in weary resignation.

"Matt!" exclaimed Martin, "you're just the fellow I want to find."

"What's wrong, Mr. Martin?" inquired Matt.

"A three-thousand-dollar car was stolen out of my garage last night. The night man was attacked, knocked over the head, and then bound hand and foot. It was a most brazen and dastardly piece of work."

"Too bad," spoke up McGlory, "but things like that will happen occasionally. Think of Matt and me getting done out of those two motor cycles of yours."

"But I'll have to put up ten times what you fellows did for the motor cycles—that is, if we can't get the car back."

"We!" boomed McGlory, starting forward in his chair. "If we can't get the car back! Are Motor Matt and Pard McGlory mixed up in that 'we'?"

"Well, I thought when you knew the circumstances that——"

"Don't hem, and haw, and sidestep," cut in McGlory keenly. "You're in trouble, and whenever anybody in the whole country stumbles against something that's gone crosswise, then it's 'Hurrah, boys,' and send for Motor Matt. I wish I had words to tell you how inexpressibly weary all this makes me. Didn't you ever stop to think, Martin, that, off and on, the motor boys might have troubles of their own?"

"But listen. You haven't heard the facts."

"What are the facts, Martin?" asked Matt.

"Why, the night man recognized one of the scoundrels[Pg 8] who struck him down. The rascal was dressed in sailor clothes and had a green patch over one eye."

"Bunce!" exclaimed Matt, starting up.

"That's it," cried Martin, glad of the impression he was making. "I knew you and McGlory had been mixed up with that sailor, and I naturally thought you'd be glad of a chance to help nab him."

"About what time was the car stolen?" asked Matt, quieting McGlory with a quick look.

"About half-past two," answered Martin. "I've got a car ready to chase the scoundrels. Have you any notion which way that car ought to go?"

"You're a trifle late taking up the pursuit," remarked Matt. "Here it is nearly eleven, and the automobile was stolen at half-past two—more than eight hours ago."

"I was up at Cairo," explained Martin, "and didn't get back till ten o'clock this morning."

"I've something of a clue," said Matt, "but it may be too late to follow it."

"Where does the clue lead?"

"To Gardenville."

"Then we'll make a fast run to Gardenville. Will you go along?"

"Yes," said Matt. "Come on, Joe."

And McGlory dutifully went. As he, and Matt, and Martin passed out of the hotel, the down-river boat from Albany whistled for Catskill Landing. The cowboy looked at it.

"We'll never get to New York," he murmured; "not in a thousand years. We're out for two different kinds of trouble, and we'll be into both of 'em up to our eyes before we're many hours older."

A HOT STARTER.

Motor Matt disliked any further entanglements with Tsan Ti and the fateful ruby fully as much as did his cowboy pard, and he was greatly perturbed over the unexpected developments which had again drawn him and McGlory into the plots and counterplots hovering around the valuable gem. But it was impossible for the king of the motor boys to turn his back upon an appeal from any one in distress when it was in his power to be of help. Nevertheless, Matt might have cut loose from the mandarin, for he did not like his Oriental methods, but his temper was stirred by that half-veiled threat in the note from Grattan.

Matt and Grattan had been at swords' points ever since the motor boys had been in the Catskills. It was largely a battle of wits, with now and then a little violence thrown in for good measure, and up to that moment neither Matt nor Grattan had scored decisively.

Through Matt's intrepid work, Tsan Ti had recovered the stolen ruby, but, as in the case where he had lost the counterfeit gem, Matt's success had been merely a fortunate blunder. On the other side of the account, Grattan could be charged with a theft of the two motor cycles and with sundry other sharp practices which had gone too much "against the grain" for Matt to overlook. The daring theft of the automobile from the garage pointed the way not only for Matt to help Martin recover the machine, but perhaps, also, to recover the motor cycles, to worst Grattan, and to be of some assistance to Tsan Ti.

On the way to the garage with Martin, Matt explained these matters to McGlory.

With the whistle of the New York boat still sounding in his ears, the cowboy listened to his chum, at first, with intense disapproval; but, at the back of McGlory's nature, there was as intense a dislike for being worsted by such a crook as Grattan as there was at the back of Matt's.

Cleverly the king of the motor boys harped on this chord, and aroused in his chum a wild desire to do something that would curb, finally and effectually, the audacious lawlessness of Philo Grattan. To such an extent did Matt influence McGlory that the latter began to wonder how he could ever have thought of leaving the Catskills while Grattan was at large.

"Sufferin' justice!" exclaimed the cowboy. "Grattan is trying to bluff us out of helping the mandarin. That's as plain as the pay streak in a bonanza mine. He must have been with Bunce when the bubble was lifted, and if we chase the chug cart we can hand the boss tinhorn a black eye by getting back the machine and landing the thieves in the skookum house. Say, that would be nuts for me! The mandarin and his idol's eye can go hang—it's Grattan we're after this trip."

Matt left his chum with that impression, well knowing that if Grattan could be captured, the affairs of the mandarin would adjust themselves satisfactorily.

The night man at the garage, his head bandaged, was lingering in the big room, watching one of the day men give a final wipe to the lamps of a six-cylinder flyer that was to take the trail after Grattan. The night man's face flushed joyfully when he saw Matt and McGlory.

"Good!" he exclaimed. "I guess there'll be something doing in these parts, now that Motor Matt is going to help in the chase."

"You're the man who was on duty when the automobile was stolen?" inquired Matt.

"Don't I look the part?"

"Martin says you identified one of the men as the old sailor who wears a green patch over one of his eyes."

"Seen him as plain as I do you, this minute."

"What did the other thief look like?"

"Didn't have a chance to tell, the attack was that sudden an' unexpected."

"You are sure there were no more than two of the thieves?"

"I could take my solemn Alfred on that."

"All aboard!" called Martin, from the car. "I'm going to let you do the driving, Matt. You can forget more about automobiles than I ever knew."

Matt stepped to the side of the car and drew on a pair of gauntlets that lay in the driver's seat; then he climbed to his place, McGlory got in behind, and the car was backed around and glided out through the wide door of the garage.

With Martin indicating the way, the machine slipped rapidly out of Catskill and darted off on the Gardenville road.

"What sort of clue is taking us to Gardenville?" asked Martin, as they weaved in and out among the tree-covered[Pg 9] hills, catching occasional glimpses of the sparkling waters of the Hudson.

Matt informed Martin briefly of Tsan Ti's predicament and of Grattan's persistent attempts to get hold of the ruby.

"You think Grattan has gone to Gardenville to intercept Tsan Ti?" asked Martin.

"It would be like Grattan," Matt answered, "to hire Sam Wing to steal the ruby from the mandarin. I don't know that Grattan has done that, but it would be like him. If he did, then he would travel toward Gardenville to pick up Sam Wing."

"This looks too much like guesswork," muttered Martin, "and not very bright guesswork, either."

"I think the same way, Martin; but it's the only clue we have. Grattan and Bunce certainly had an object in view when they stole the motor car. The theft, happening at the time it did, rather inclines me to think that Grattan is beginning a swift campaign to recover the Eye of Buddha."

"Since half-past two he has had oceans of time to reach Gardenville and pick up Sam Wing and the ruby—if that was his game."

"Exactly," returned Matt. "I was telling you the same thing back at the hotel. What sort of a car was it that was stolen?"

"It was a blue car, six cylinder, and had a tonneau and top. It belonged to a man from New York. He's been telegraphing and telephoning all through the mountains. If the thieves didn't get away last night, they'll have a hard time doing it to-day."

Matt was watching the road. It was a popular highway for motor-car owners, and the surface bore evidence of the passage of many pneumatic tires. Half a dozen cars passed them, going the other way, and inquiries were made as to the blue car. The stolen automobile had not been seen or heard of. At least two of the passing drivers had come from Gardenville, and their failure to have seen anything of the stolen machine promised ill for the success of the pursuers when they should reach their destination.

"I guess I'm up against it, all right," growled Martin. "This Grattan is a clever scoundrel, and he'll know what to do to keep from getting captured."

"What's that place ahead there?" asked Matt.

What he saw was a spot where the road curved a little to one side in a valley between two hills. There were two or three hitching posts planted beside the road, and from one of the posts swung a tin bucket.

"That's a spring," said Martin, "and it furnishes ice-cold water in the very hottest part of the summer. People stop there to water their horses—and to get a drink themselves if they're thirsty."

"Let's stop, pard," called McGlory, from the tonneau. "I'm dryer than a sand pile and my throat's full of dust."

"We're only three miles from Gardenville," spoke up Martin, his words significant of the fact that there would be plenty of drinking water to be had in the town without delaying the journey at the spring.

"We'll only be a minute," said Matt, swerving to the side of the road and bringing the car to a halt.

All three jumped out, and Martin led the way to a small pool, shaded by overhanging trees. From beyond the pool came a tinkle of falling water.

"Horses are watered from this basin," remarked Martin. "The water falls from the rocks, farther on, and we'll find a cup there."

A well-worn path followed the rill that supplied the pool, and the three continued onward along the path in single file. Half a dozen yards brought them to the rocky side hill where the water welled from a crack in the granite and fell in a miniature cataract to a bowl-shaped depression at the foot of the wall.

A man was standing beside the spring when Martin, Matt, and McGlory emerged from the tangle of brush and vines. The man was just lifting himself erect after filling a tin cup that was chained to the rocks. Startled into inaction, the man stood staring at the three newcomers, the filled cup in his hand.

The surprise, it may be observed, was mutual.

The man by the spring was a Chinaman—a lean, hatchet-faced individual whose blouse and baggy trousers gave evidence of rough work in the undergrowth.

"Sam Wing!" yelled McGlory.

Yes, it was the treacherous Celestial, there was not the slightest doubt about that.

Simultaneously with his shout, McGlory leaped forward, closely followed by Matt. Sam Wing awoke to his peril not a second too soon. Casting the cup of water full in the cowboy's face, the Chinaman gave vent to a defiant yell, whirled, and vanished among the trees.

McGlory sputtered wrathfully as he shook the water out of his eyes. Matt bounded on in frantic pursuit of the fugitive.

"Come back!" cried Martin, thinking of nothing but the stolen car. "What's the use of chasing the chink?"

"You freeze to the automobile, Martin," the cowboy paused to answer. "Matt and I will put the kibosh on this yellow grafter and then we'll rejoin you. We'll not be gone long."

The words faded in a rattle and crash of violently disturbed bushes, and McGlory had vanished along his chum's trail.

M'GLORY IS LOST—AND FOUND.

This unexpected encounter with Sam Wing was certainly a "hot starter" in the matter of the stolen ruby, although of apparently small consequence in the matter of the stolen car. But Motor Matt was not particular as to which end of the double thread fortune wafted his way. He followed Sam Wing just as zealously as he would have followed Philo Grattan, had it been the white thief instead of the yellow who had fled from the spring.

The cold spring water had run down the cowboy's face, under his collar, and had glued his shirt to his wet skin.

"Speak to me about that!" he breathed angrily, as he labored on. "If the rat-eater hadn't slammed that water into my face, I'd have had him by his yellow throat in a brace of shakes! Wow, but it's cold! I feel as though I was hugging an iceberg. Where's Matt?"

McGlory had not seen his chum since he had plunged into the bushes, but had followed blindly in a course he believed to be the right one, trying only to see how much ground he could cover.

Now, realizing suddenly that he might be on the wrong track, the cowboy halted, peered around him, and listened intently. The timber was thick and the bushes dense on every side. There were no sounds in any direction even remotely suggesting the Chinaman's flight and Matt's pursuit.

"I'm off my bearings and no mistake," reflected the cowboy, searching the ground in vain for some signs of the course taken by Sam Wing and Matt. "Matt will have a time overhauling the chink in this chaparral, and the two of us are needed. But which way am I to go?"

McGlory had been hurrying along the side hill that edged the valley and the road. He swept his eyes across the narrow valley, and then up the slope toward the top of the hill.

"It's a cinch," he ruminated, "that Sam Wing wouldn't go near the trail, but would do his level best to get as far away from it as he could. That means, if I'm any guesser, that he climbed the hill and tried to lose himself beyond. Me for the other side," and the cowboy began pawing and scrambling up the steep slope.

Ten minutes of hard work brought him to the crest, and here again he halted to peer anxiously around and to listen. He could neither hear nor see anything that gave him a line on Matt and the Chinaman.

"Whoop-ya!" he yelled at the top of his lungs. "Matt! Where are you, pard?"

A jaybird mocked him from somewhere in the timber, and a frightened hawk took wing and soared skyward.

"Blamed if this ain't real excitin'!" growled the cowboy. "I'm going to do something to help lay that yellow tinhorn by the heels, though, and you can paste that in your hat. If Matt came over the hill, then it stands to reason he went down on this other side. I'll keep on, by guess and by gosh, and maybe something will happen."

McGlory kept on for half an hour, floundering through the bushes, making splendid time in his slide to the foot of the hill, and from there striking out on an erratic course that carried him toward all points of the compass. He climbed rocky hills and descended them, he followed ravines, and he sprinted across narrow levels, yelling for Matt from time to time, but receiving no answer. Then he discovered that something had happened—and that he was lost.

Trying to locate himself by the position of the sun, he endeavored to return to the road. Instead of calling for Matt, he now began whooping it up for Martin. The sun appeared to be in the wrong place, and the road and the spring had vanished. The farther McGlory went, the more confused and bewildered he became. At last he dropped down on a bowlder and panted out his chagrin and disgust.

"Lost! Me, Joseph Easy Mark McGlory, Arizona puncher and boss trailer of the deserts and the foothills! Lost, plumb tangled up in my bearings, clean gone off the jump—and in this two-by-twice range of toy mountains where Rip Van Winkle snoozed for twenty years. I wonder if Rip was as tired as I am when he laid down to snatch his forty winks. Sufferin' tenderfoot! I've walked far enough to carry me plumb to Albany, if it had all been in a straight line. Matt!" and again he lifted his voice. "Martin!"

The lusty yell echoed and reverberated through the surrounding woods, but brought no answer.

Then, suddenly, the cowboy was seized from behind by a pair of stout arms, pulled backward off the bowlder, and flattened out on the ground by a heavy knee on his chest.

It had all happened so quickly that McGlory was dazed. He was a moment or two in recovering his wits and in recognizing the sinister face and mocking eyes that bent down over him.

"Grattan!" he gasped.

"Ay, messmate," gibed a voice from near at hand; "Grattan and Bunce. Don't forget Bunce."

The cowboy turned his head and saw the sailor. The green patch decorated one of the sailor's eyes, but the other eye taunted the luckless prisoner with an exultant gleam.

McGlory struggled desperately under Grattan's hands.

"Stop it!" ordered Grattan.

As McGlory had made no headway with his frantic struggles, he decided to obey the command.

"What are you doing out here in the woods?" inquired Grattan.

"Ease up on that throat a little," wheezed the cowboy. "Want to take the breath all out of me?" The thief's fingers relaxed slightly. "I left the road a spell ago," proceeded McGlory, "and went wide of my bearings somewhere—I don't know just where."

"Lost, eh?" laughed Grattan. "Well, my lad, you've been found."

"How did you happen to find me?"

"How?" jeered Bunce. "You was makin' more noise than a foghorn. The way you was askin' Motor Matt for help, it's a wonder they didn't hear you in Catskill."

"Tie his hands with something, Bunce," said Grattan.

Bunce looked taken aback for a space, then whipped his knife laniard from about his neck, removed the knife, doubled the cord, and contrived a lashing that was strong enough to answer the purpose.

Grattan heaved the cowboy over upon his face and pulled his wrists behind him. In less than a minute the cord was in place, and the prisoner was freed of Grattan's gripping hands and allowed to sit up, his back against the bowlder.

"This meeting," grinned Grattan, "was entirely unexpected, and a pleasant surprise."

"A pleasant surprise for you, I reckon," grunted McGlory. "What did you jump onto me for like this? What good is it going to do you?"

"What benefit I am to derive from this encounter," replied Grattan, "remains to be seen. Tell me, my lad, are you and Motor Matt looking for Tsan Ti?"

An angry denial was on the cowboy's lips, but he thought better of the words before they were spoken.

"Never you mind who we're looking for, Grattan," said he.

"It's for Tsan Ti, I am sure," went on Grattan. "He's somewhere in this section, for he left Gardenville on foot, early this morning, preceded by his man, Sam Wing. I don't know exactly what's up, but I'm rather inclined to think that the mandarin is afraid of me, and is trying to get back to Catskill and place himself under the wing of his estimable protector, Motor Matt. You and Matt heard he was coming and advanced to meet him. The same man who told me the fat Chinaman was in the hills must have given you boys the same information."

"Who was the hombre, Grattan?" queried McGlory, secretly delighted to think Grattan's speculations were so wide of the mark.

"A man in a white runabout with a red torpedo beard."

"I wouldn't know a red torpedo beard from a Piute's scalplock, but I do recollect a shuffer in a white car."

This white runabout was one of the cars Matt, Martin, and McGlory had passed on the road, and the driver was one of those of whom they had made inquiries. The inquiries, of course, had been all about the stolen automobile and not about the fat Chinaman. If Grattan had been in the stolen car when asking the man in the white runabout for news of Tsan Ti, then why hadn't the runabout driver remembered the blue car and told Matt something about it?

"Where were you," went on the cowboy, "when you hailed the man in the white car?"

"On foot, by the spring," answered Grattan genially.

He was an educated man and usually good-natured—sometimes under the most adverse circumstances. That was his way, perhaps on the principle that an easy manner is best calculated to disarm suspicion.

"Where was the car you and Bunce stole from the Catskill garage?" asked the cowboy.

"We tucked it away in a pocket of the hills that my friend Pardo knew about," explained Grattan, tacitly admitting the theft and, in his customary fashion, not hesitating to go elaborately into details. "We failed to finish the work that took us to Gardenville last night. When we learned at the railroad station in that town that the fat Chinaman had started south on foot, about break of day, following another of his countrymen, we rushed the car back into an obscure place. It is not advisable, you understand, to make that car too prominent. We shall have to use it by night. Bunce and I rode to the spring on our motor cycles for the purpose of watching the road. The white runabout came along, and the driver told us, he had passed Tsan Ti, walking this way. We waited for him to pass the spring, but he did not. Thinking he had taken to the rough country, Bunce and I returned our wheels to the place where we have pitched temporary camp and began prowling around in the hope of finding the mandarin. Then, quite unexpectedly, I assure you, we heard you calling. We came to this place, guided by the sound of your voice. You know the rest, and——"

Grattan bit off his words abruptly. From a distance came a hail, so far off as to be almost indistinguishable.

"Motor Matt!" exclaimed Grattan, with a laugh. "He's looking for you, McGlory. If this keeps up, we're going to have quite a reunion. Put a hand over his lips, Bunce," he added to the sailor.

McGlory tried to give a desperate yell before the hand closed over his mouth, but he was not quick enough. Grattan, leaning against the bowlder, threw back his head and answered the distant call.

The voice in the woods drew closer and closer.

"Call again, excellent one!" came the weary voice from the scrub. "I heard you shouting some time ago, and you were calling the name of an esteemed friend for whom I am looking. Speak loudly to me, so that I may come where you are."

The three by the bowlder were astounded.

"Tsan Ti," muttered Grattan, "or I don't know the voice. Luck, Bunce! Whoever thought this could happen? The mandarin heard McGlory calling for Motor Matt—and now the mandarin is looking for McGlory and is going to find us." A chuckle came with the words. "Lie low, Bunce, and watch McGlory. Leave the trapping of Tsan Ti to me."

"POCKETED."

For the cowboy pleasant fancies were cropping out of this surprising turn of events. He reflected that Grattan did not know Sam Wing had stolen the ruby from Tsan Ti. By entrapping Tsan Ti, Grattan was undoubtedly counting upon getting hold of the Eye of Buddha.

If Bunce had known how little love McGlory had for the mandarin, he would not have been at so much pains to keep a hand over his lips. Just at that moment nothing could have induced the cowboy to shout a warning to the approaching Chinaman.

Kneeling behind the bowlder, Grattan lifted his voice for Tsan Ti's benefit. Presently the mandarin was decoyed around the side of the bowlder, and his capture expeditiously effected.

He was a badly demoralized Chinaman. His usually immaculate person had been eclipsed by recent hardships, and he was tattered and torn and liberally sprinkled with dust. His flabby cheeks were covered with red splotches where thorny undergrowth had left its mark. He was so fagged, too, that he could hardly stand. At the merest touch from Grattan he tumbled over. A most melancholy spectacle he presented as he sat on the ground and stared at Grattan with jaws agape.

"Oh, friend of my friend," wheezed Tsan Ti, passing his gaze to McGlory, "was it you who shouted?"

"First off it was," answered McGlory; "after that, Grattan took it up."

"And you are a prisoner?"

"I wouldn't be here if I wasn't."

"I'm the man for you to talk to, Tsan Ti," put in Grattan grimly. "It's me you're to reckon with."

"Evil individual," answered the mandarin, "my capture will not help you in your rascally purposes. Is not my present distress sufficient, without any of your unwelcome attentions? Behold my plight! What more can you do to make me miserable?"

"I can take the ruby away from you, for one thing."

A mirthless smile crossed the mandarin's fat face. A chuckle escaped McGlory.

Grattan stared hard at the Chinaman, and then flashed a quick glance at the cowboy.

"What are you thinking of, McGlory?" he demanded.

"I'm thinking that you're fooled again, Grattan," answered McGlory. "You know so much that I wonder you haven't heard that the mandarin has lost the ruby."

"Lost it?" A look of consternation crossed Grattan's face. "I'll never believe that," he went on. "Tsan Ti knows where the Eye of Buddha is, and there are ways to make him tell me."

"Ay, ay," flared Bunce, with a fierce look, "we'll make him tell if we have to lash him to a tree and flog the truth out o' him."

"Wretches," said the mandarin, "no matter what your[Pg 12] hard thoughts may counsel, or your wicked hands contrive, you cannot make me tell what I do not know."

Grattan would not trust Bunce to search the mandarin, but proceeded about the work himself. Two chopsticks, a silver cigarette box, an ivory case with matches, a bone-handled back scratcher, a handkerchief, a fan, and a yellow cord some three feet long were the results of the search.

There was no ruby. Grattan prodded a knife blade into Tsan Ti's thick queue in his search for the gem, and even ripped out the lining of his sandals, but uselessly.

"You know where the ruby is," scowled Grattan, giving way to more wrath than McGlory had ever seen him show before; "and, by Heaven, I'll make you tell before I'm done with you."

Tossing the yellow cord to Bunce, Grattan drew back and ordered the sailor to secure the mandarin's hands in the same way he had lashed the cowboy's.

Tsan Ti seemed to accept the situation philosophically. But that he was in desperate straits and hopeless was evidenced by his remark when Bunce was done with the tying:

"Despicable person, I had rather you put the yellow cord about my throat than around my wrists."

"You'll get it around the throat when we get back to the pocket," said Grattan brutally. "Take charge of McGlory, Bunce," he added, "and come with me."

Tsan Ti was ordered to his feet. Thereupon, Grattan seized his arm and pulled him along through the woods.

McGlory would have given something handsome if he could have had the use of his hands for about a minute. Bunce would have been an easy problem for him to solve if he had not been hampered by the knife laniard. As it was, however, the cowboy was forced to get to his feet and, with the sailor as guard, follow after Grattan and Tsan Ti.

Captors and captives traveled for nearly a mile through uneven country, thick with timber, then descended into a ravine, followed it a little way beyond a point where it was crossed by a wagon road, and came to a niche in the gully wall.

Perhaps the term "cavern" would better describe the place where Grattan, Pardo, and Bunce had pitched their temporary camp. The hole was an ancient washout, its face covered with a screen of brush and creepers.

In front of the niche, standing in a place where it had been backed from the road on the "reverse," was the blue automobile. Leaning against the automobile were the two motor cycles; and from the tonneau of the car, as Grattan and Bunce approached with their prisoners, arose the form of Pardo.

"Well, well!" exclaimed Pardo, thrusting his head out from under the top. "If we haven't got visitors! Where did you pick up the mandarin, Grattan?"

"Between here and the Gardenville road," answered Grattan. "It was easy work. Both the chink and the cowboy were kind enough to yell and tell us where they were."

Pardo, understanding little of what had really occurred, opened his eyes wide.

"Tell me more about it," said he.

"After I get the prisoners in the pocket. Bunce, bring a rope. Hold McGlory, Pardo, while he's doing it."

Pardo jumped down from the automobile and caught the cowboy's arm.

"I guess you're a heap easier to deal with than your friend, Motor Matt," was his comment.

"No guess about it," said McGlory, "it's a cinch. But I'm not fretting any."

The cowboy's eyes were on the stolen car. What a pleasure it would have been to snatch that automobile out of Grattan's clutches, leaving him and his rascally companions stranded in the hills! But that was a dream—and McGlory had already had too many dreams for his peace of mind.

Tsan Ti was shoved by Grattan through the bushes, under the trailing vines and into the washout. Pardo dragged McGlory through, close on their heels.

"Sit down, both of you," ordered Grattan, when the prisoners were in the gloomy confines of the niche.

Tsan Ti and McGlory lowered themselves to the bare earthen floor. Bunce came with the rope, and it was coiled around the cowboy's ankles, and then around the mandarin's.

"I've taken you in, McGlory," observed Grattan, to the cowboy, "for the purpose of finding out what Motor Matt is doing; and I've captured the mandarin with the idea of getting the ruby. I'm a man who hews steadily to the line, once he marks it out. I'll have my way with both of you before I am done. Mark that. You can't get away from here. Even if you were not bound hand and foot, you'd have to pass the automobile in order to reach the road—and Pardo, Bunce, and I will be in the automobile. We're all heeled, which is a point you will do well to remember."

Having eased his mind in this manner, Grattan went out of the niche, Bunce and Pardo following him. They could be heard climbing into the automobile, and then their low voices came in a mumble to the ears of the prisoners.

"Fated friend," gulped the mandarin, "the ten thousand demons of misfortune are working sad havoc with Tsan Ti."

"Buck up!" returned McGlory. "We're pocketed, all right, but matters might be worse."

"What cheering thoughts can I possibly have?" mourned the mandarin. "The Eye of Buddha has escaped me, gone I do not know where, in the possession of that Canton dog, Sam Wing, who——"

"Hist!" breathed McGlory, in a warning voice. "Grattan doesn't know who has the ruby, and it may be a good thing if we keep it to ourselves. Don't lose your nerve. Motor Matt is around, and you can count on him to do something."

"Motor Matt is both notable and energetic," droned the mandarin, "but for him to secure the ruby from Sam Wing is too much to hope for."

"There you're shy a few, Tsan Ti. I'll bet my scalp against that queue of yours that Matt has already captured Sam Wing and recovered the Eye of Buddha."

Tsan Ti stirred restlessly.

"Do not deceive me with hope, honorable friend," he begged.

"Well, listen," and McGlory proceeded to tell Tsan Ti what had happened at the spring.

Tsan Ti's hopes arose. He had been ready to grasp at anything, and here McGlory had offered him undreamed-of encouragement.

"There are many brilliant eyes in the plumage of the sacred peacock," he murmured, "but by them all, I vow to you that there is no other youth of such accomplishments as Motor Matt. And, by the five hundred gods of the temple at——"

"Cut it out," grunted McGlory. "You've got Matt and me into no end of trouble with your foolishness. When you get that ruby into your hands again, stop fumbling with it. Pass it over to some one who knows how to look after it, but don't try the job yourself. This is first-chop pidgin I'm giving you, Tsan Ti, and I don't know why I'm handing it out, after the way you hocused my pard and me with that piece of red glass. But it's good advice, for all that, and you'd better keep it under your little black cap."

Tsan Ti relapsed into thoughtful silence. The mumble of voices continued to creep in through the swinging vines and the bush tops, but otherwise the quiet that filled the "pocket" was intense.

The mandarin was first to speak. Leaning toward the cowboy, he whispered:

"There's a chance, companion of my distress, that we may be able to make our escape."

"What's the number?" queried the cowboy.

Thereupon the mandarin began revealing the plan that had formed in his mind. It was the fruit of considerable reflection and promised well.

SPRINGING A "COUP."

Stripped of its ornamental trimmings, the mandarin's plan was marvelously simple. McGlory was to roll over with his back to him, and he engaged to gnaw through the knife laniard. When the cowboy's hands were free it would be only a few moments until he removed the ropes from his ankles and set Tsan Ti at liberty.

This accomplished, McGlory was to set up a racket, calling Grattan, Bunce, and Pardo into the pocket. As they crashed through the brush in one direction, the mandarin would crash through it in another, reach the motor cycles, and rush away on one before Grattan or his companions had an opportunity to use their firearms.

"H'm," reflected McGlory. "That's a bully plan, Tsan Ti—for you. You're the boy to look out for Number One, eh? This surprise party you're thinking of springing reminds me of the way you unloaded that imitation ruby on Motor Matt, and then sat back and allowed Matt and me to play tag with Grattan."

"What is the fault with my plan, generous sir?" asked the mandarin.

"Of course," went on the cowboy, with fine sarcasm, "I don't amount to much. I kick up a disturbance in here, and when Grattan, Pardo, and Bunce rush in on me, you make a run for one of the motor cycles. In other words, I hold the centre of the stage and make things interesting for the three tinhorns while you burn the air on a benzine bike and get as far outdoors as you can. Fine!"

"Pardon, exalted friend," demurred Tsan Ti, "but you overlook the point that I will be pursued."

"I don't think I overlook a blessed point, Tsan Ti. But just answer me this: What's the good of escaping? Grattan will have to let us go sooner or later. If we put up with these uncomfortable ropes for a spell, we'll both get clear and without running the risk of stopping a bullet."

"Accept my excuses, noble youth, and please remember Grattan made some remarks about choking me with the cord in case I did not reveal the whereabouts of the ruby. That would not be pleasant."

"Sufferin' stranglers!" exclaimed McGlory; "I'd forgotten about that. Can't say that I blame you for thinking twice for yourself and once for me. I'll help on the game." The cowboy rolled over with his back to the mandarin. "Now get busy with your teeth," he added, "and be in a rush. There's no telling when the pallavering outside will be over with, and if those fellows get through before we do, the kibosh will be on us and not on them."

The logic of this last remark was not lost upon the mandarin. He grunted and wheezed and used his teeth with frantic energy. While he panted and labored, both he and the cowboy kept their ears sharp for the mumble of talk going on outside.

Fortunately for the coup the prisoners were intending to spring, the talk continued unabated. The laniard was gnawed in half, and McGlory sat up, brought his hands around in front of him, and rubbed the places where the mandarin's sharp teeth had slipped from the cord.

"You've turned part of the trick, Tsan Ti," commended the cowboy; "now watch me do my share."

With his pocket knife he slashed through the coil that held his feet, and he would then have treated the yellow cord about the mandarin's wrists in like manner had he not been stopped by a quick word.

"The yellow cord, illustrious one," said the Chinaman, "must be untied. It is a present from his imperial highness, my regent, and I may yet be obliged to use it in the customary way."

"Oh, hang your regent!" grumbled McGlory, but yielded to the mandarin's request and began untying the cord with his fingers.

This was slow work, for McGlory's fingers were still numb from the effects of his own bonds. In due course, however, the cord was removed, and the Chinaman lifted himself to a sitting posture. The cowboy used the knife on the rope that secured Tsan Ti's feet, while the latter was solicitously coiling up the yard of yellow cord and putting it away in his pocket.

"Now, courageous friend," whispered the mandarin, getting up noiselessly and stepping to the swinging green barrier at the mouth of the niche, "we are ready."

"You know how to manage a motor cycle?" queried McGlory, suddenly stifling the roar that was almost on his lips.

"Excellently well, superlative one."

"Then good luck to you. Here goes."

Above the fearsome commotion McGlory made, the words "Help!" and "Hurry!" might have been distinguished. Startled exclamations came from the automobile, followed by a sound of scrambling as the three thieves tumbled out. Then there was a crashing among the bushes and the vines, and McGlory rolled back at full length and shoved his unbound hands under him.

"What's the matter?" cried Grattan, who was first to enter the pocket.

"Mandarin tried to knife me!" whooped McGlory. "Why didn't you take his knife away from him? I might have been sent over the one-way trail if I hadn't yelled."

All three of the men were in the niche by that time.

"Where is the chink?" shouted Grattan.

The poppety-pop-pop of a motor in quick action came from without.

"He's tripped his anchor and is makin' off!" yelled Bunce.

"Stop him!" fumed Grattan, and instantly he followed Bunce and Pardo back through the swinging screen of vines and bushes.

Chuckling with delight, McGlory leaped erect, sprang to the vines, and parted them so he could look out.

Tsan Ti, his motor working splendidly, was streaking down the ravine toward the road. Bunce, who had led in the rush from the pocket, had mounted the other motor cycle and was coaxing his engine into action with the pedal.

"Catch him, Bunce!" bellowed Grattan.

Bunce's answer was lost in a series of explosions as his motor got to work. As he whirled away, Grattan and Pardo ran after him to watch the pursuit as long as possible.