Title: The Irish Penny Journal, Vol. 1 No. 15, October 10, 1840

Author: Various

Release date: February 27, 2017 [eBook #54252]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Brownfox and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from

images generously made available by JSTOR www.jstor.org)

| Number 15. | SATURDAY, OCTOBER 10, 1840. | Volume I. |

Localities are no less subject to the capricious mutations of fashion in taste, than dress, music, or any other of the various objects on which it displays its extravagant vagaries. The place which on account of its beauties is at one period the chosen resort of pleased and admiring crowds, at another becomes abandoned and unthought of, as if it were an unsightly desert, unfit for the enjoyment or happiness of civilized man. Some other locality, perhaps of less natural or acquired beauty, becomes the fashion of the day, and after a time gets out of favour in turn, and is neglected for some other novel scene before unthought of or disregarded. Yet the principles of true taste are immutable, and that which is really beautiful is not the less so because it has ceased to attract the multitude, who are generally governed to a far greater extent by accidental associations of ideas than by any abstract feelings of the mind.

Perhaps it is less attributable to any characteristic volatility in the character of the inhabitants of our metropolis, than to the singular variety and number of the beautiful localities which surround our city, and in emulous rivalry attract our attention, that this inconstancy of attachment to any one locality is more strikingly instanced among ourselves, than among the citizens of any other great town with which we are acquainted. But, however this may be, the fact is unquestionable, that there is scarcely a spot of any natural or improved beauty, within a few miles of us, which has not in turn had its day of fashion, and its subsequent period of unmerited neglect. Clontarf, with its sequestered green lanes, and its glorious views of the bay—Glasnevin, the classical abode of Addison, Parnell, Tickell, Sheridan, and Delany—Finglas, with its rural sports—Chapelizod, the residence of the younger Cromwell—Lucan, Leixlip, with their once celebrated spas, and all the delightful epic scenery of the Liffey—Dundrum, with its healthy mountain walks and atmosphere, and many others unnecessary to mention, all experiencing the effects of this inconstancy of fashion, have found their once admired beauties totally disregarded, and the admiration of the multitude almost wholly transferred to a wild and unadorned beauty on the rocky shores of Kingstown and Bullock, which our forefathers deemed unworthy of notice. But let that beauty take warning from the fate of her predecessors, and not hold her head too high in her day of triumph, for she too will assuredly be cast off in turn, and find herself neglected for some rival as yet unnoticed.

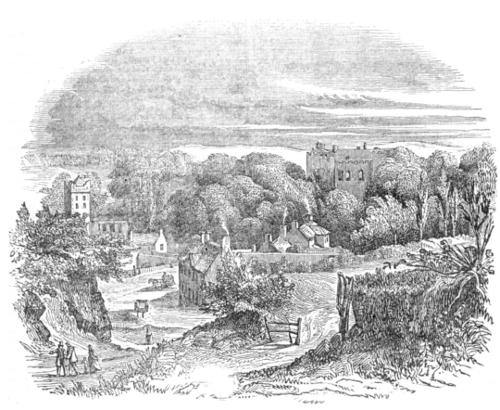

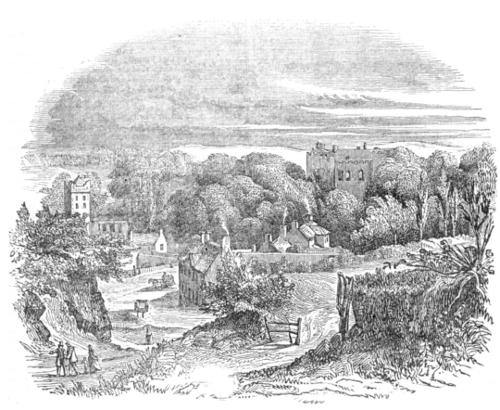

Of such unmerited inconstancy and neglect there are no localities in the neighbourhood of Dublin which have greater reason to complain than the village of Lucan and that which forms the subject of our prefixed embellishment. As the establishment of peace in Ireland led to an increase of civilization, which exhibited itself in improved roads and vehicles of conveyance, and the citizens, emerging from their embattled strongholds, ventured to enjoy the pleasures of nature and rural life, Lucan and Leixlip, with the beautiful scenery in which they are situated, became the favourite places of resort; and their various natural attractions becoming heightened by art, were described by travellers, and chaunted in song. About “sixty years since” they had reached their greatest glory, and Leixlip was the favourite of the day. It is thus described at this period by the celebrated Doctor Campbell:—“All the outlets of Dublin are pleasant, but this is superlatively so which leads through Leixlip, a neat little village about seven miles from Dublin, up the Liffey; whose banks being prettily tufted with wood, and enlivened by gentlemen’s seats, afford a variety of landscapes, beautiful beyond description.” It was at this period also that O’Keefe, in his popular opera of “The Poor Soldier,” makes Patrick sing—

But though Leixlip no longer holds out attractions sufficient to gratify those whose tastes are dependent on fashion, it has never ceased to be a favourite with all whose tastes had a more solid foundation. It was here, and in its immediate vicinity, that the two Robertses, genuine Irish landscape painters, found many of the most congenial subjects for their pencils. It was here, too, that the strong-headed painter of strong heads—the Rembrandt of miniature painters, John Comerford—used occasionally to retire, abandoning for a week or two the intellectual society of Dublin which he so much enjoyed, and the acquisition of gain which he no less relished, to make some elaborate study of one of the scenes about the Bridge of Leixlip, which he, in his own dogmatic way, asserted, “for genuine landscape beauty, could not be surpassed or even rivalled any where!” This estimate of the beauties of Leixlip’s “close shady bowers, &c.” was, we confess, a somewhat extravagant one; yet, like most other honestly formed opinions of Comerford’s, it would not have been an easy task to shake his belief in its truth, and to sustain it he could, if combated, adduce the testimony of his and our friend Gaspar Gabrielli, the first of Italian landscape painters of our times, who notwithstanding his pride in being a Roman, and his national predilections in favour of the classic scenery of his dear Italy, has often declared in our hearing that he had never seen in his own country scenery of its kind comparable with that of the Liffey, in the vicinity of Lucan and Leixlip.

But enthusiastic admiration of the scenery of Leixlip has not been confined to the painters. Hear with what gusto our friend C. O. lets himself out on this subject, not in his drawing-room character as the clerical Connaught tourist, but in his more natural, buoyant, and Irish one, as Terence O’Toole, our co-labourer in the first volume of the Dublin Penny Journal:—

“Any one passing over the Bridge of Leixlip, must, if his eye is worth a farthing for anything else than helping him to pick his way through the puddle, look up and down with delight while moving over this bridge. To the right, the river winning its noisy turbulent way over its rocky bed, and losing itself afar down amidst embossing woods; to the left, after plunging over the Salmon-leap, whose roar is heard though half a mile off, and forming a junction with the Rye-water, it takes a bend to the east, and washes the rich amphitheatre with which Leixlip is environed. I question much whether any castle, even Warwick itself [bravo, Terence!] stands in a grander position than Leixlip Castle, as it embattles the high and wooded grounds that form the forks of the two rivers. Of the towers, the round one of course was built by King John, the opposite square one by the Geraldines. This noble and grandly circumstanced pile has been in latter days the baronial residence of the White family, and subsequently the residence of [lord-lieutenants] generals and prelates. Here Primate Stone, more a politician than a Christian [churchman], retired from his contest with the Ponsonbys and the Boyles to play at cricket with General Cunningham; here resided Speaker Connolly before he built his splendid mansion at Castletown; here the great commoner, as he was called, Tom Connolly, was born. Like many such edifices, this castle is haunted: character and keeping would be altogether lost if towers of 600 years’ standing, with rich mullioned ‘windows that exclude the light, and passages that lead to nothing,’ with tapestried chambers that have witnessed pranks of revelry and feats of war, of Norman, Cromwellian, and Williamite possession, if such a place had not its legend; and one of Ireland’s wildest geniuses, the eccentric and splendid Maturin, has decorated the subject with the colourings of his vivid fancy.”

Terence adds:—“Leixlip is memorable in an historic point of view as the place where, in the war commencing 1641, General Preston halted when on his way to form a junction with the Marquis of Ormonde to oppose the Parliamentarians. Acknowledging that his army was not excommunication proof, he bowed before the fiat of the Nuncio, and lost the best opportunity that ever offered of saving his cause and his country from what has been called the ‘curse of Cromwell.’”

To this brief but graphic sketch of our friend we can add but little. Leixlip is a market and post town of the county of Kildare, situated in the barony of North Salt—a name derived from the Latin appellation of the cataract called the Saltus Salmonis, “Salmon Leap,” in the vicinity of the town—and is about eight miles from Dublin. It contains between eleven and twelve hundred inhabitants, and consists of one long street of houses, well, though irregularly built, but exhibiting for the greater number an appearance of negligence and decay. It is bounded on one extremity by the river Liffey, which is crossed by a bridge of ancient construction, and on the other by the Rye-water, over which there is a bridge of modern date. As the focus of a parish, it has a church and a Roman Catholic chapel, both of ample size and substantial construction, but, like most edifices of their class in Ireland, but little remarkable for the purity of their architectural styles. The latter is of recent erection. Its most imposing architectural feature is, however, its castle, which is magnificently situated on a steep and richly wooded bank over the Liffey; but though of great antiquity, it exhibits in its external character but little of the appearance of an ancient fortress, having been modernised by the Hon. George Cavendish, its present occupier. On its west side it is flanked by a circular, and on its east by a square tower. This castle is supposed to have been erected in the reign of Henry II. by Adam de Hereford, one of the chief followers of Earl Strongbow, from whom he received as a gift the tenement of the Salmon Leap, and other extensive possessions. It is said to have been the occasional residence of Prince John during his governorship of Ireland in the reign of his father; and in recent times it was a favourite retreat of several of the Viceroys, one of whom, Lord Townsend, usually spent the summer here. From an inquisition taken in 1604, it appears that the manor of Leixlip was part of the possessions of the abbey of St Thomas in Dublin. In 1668, the castle, with sixty acres of land, belonged to the Earl of Kildare. They afterwards passed into the hands of the Right Hon. Thomas Connolly, Speaker of the Irish House of Commons, and are now the property of Colonel Connolly of Castletown.

P.

[1] The game of chess is repeatedly noticed in connection with various historical incidents in the early history of Ireland. Theophilus O’Flanagan, in a note to his translation of Deirdri, an ancient Irish tale, published in the Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Dublin, speaks of it as “a military game that engages the mental faculties, like mathematical science.” O’Flaherty’s Ogygia states that Cathir, the 120th king of Ireland, left among his bequests to Crimthan “two chess-boards with their chess-men distinguished with their specks and power; on which account he was constituted master of the games in Leinster.”

In the first book of Homer’s Odyssey the suitors are described as amusing themselves with the game of chess:—

In Pope’s translation there is a learned note on the subject, to which the curious reader is referred; and also to a passage in Vallancey’s Essay on the Celtic Language.

[2] Literally, as lime.

[3] This will remind the reader of a similar question by Venus in the first Eneid:—

[4] A note in Miss Brooke’s translations informs us that “Finn was reproached with deriving all his courage from his foreknowledge of events, and chewing his thumb for prophetic information.”

[5] Quadrangular—the ancient cup of the Irish, called meadar. Specimens of it may be seen in the Antiquarian Museum of the Royal Irish Academy.

Discretion.—This is a nice perception of what is right and proper under the circumstances in which a person is called to act. It may be illustrated by the feelers of the cat, which are long hairs placed upon her nose, with which she readily measures the space between sticks and stones through which she desires to pass, and thus determines, by a delicate touch, whether it is sufficiently large to let her go through without being scratched. Thus discretion appreciates difficulties, dangers, and obstructions around, and enables a person to decide upon the proper course of action. “There are many more shining qualities in the mind of man, but there is none so useful as discretion. It is this which gives a value to all the rest, which sets them at work, and turns them to the advantage of the person who is possessed of them. Without it, learning is pedantry and wit impertinence; nay, virtue itself often looks like weakness. Discretion not only shows itself in words, but in all the circumstances of action; and is like an agent of Providence, to guide and direct us in the ordinary chances of life.” But how shall discretion be cultivated in children? Chiefly by example. It is a virtue especially committed to the cultivation of the mother. She may do much to promote it, by rebuking acts of imprudence, and bestowing due encouragement upon acts of discretion. Let the mother remember that discretion is important to men, and see that she cherishes it in her sons; let her remember that it is essential to women, and make sure of it in her daughters.—Dr Channing.

Though this word at a glance may be said to explain itself, yet lest our English or Scotch readers might not clearly understand its meaning, we shall briefly give them such a definition of it as will enable them to comprehend it in its full extent. The Irish Matchmaker, then, is a person selected to conduct reciprocity treaties of the heart between lovers themselves in the first instance, or, where the principal parties are indifferent, between their respective families, when the latter happen to be of opinion that it is a safer and more prudent thing to consult the interest of the young folk rather than their inclination. In short, the Matchmaker is the person engaged in carrying from one party to another all the messages, letters, tokens, presents, and secret communications of the tender passion, in whatever shape or character the said parties may deem it proper to transmit them. The Matchmaker, therefore, is a general negociator in all such matters of love or interest as are designed by the principals or their friends to terminate in the honourable bond of marriage; for with nothing morally improper or licentious, or approaching to the character of an intrigue, will the regular Irish Matchmaker have any thing at all to do. The Matchmaker, therefore, after all, is only the creature of necessity, and is never engaged by an Irishman unless to remove such preliminary obstacles as may stand in the way of his own direct operations. In point of fact, the Matchmaker is nothing but a pioneer, who, after the plan of the attack has been laid down, clears away some of the rougher difficulties, until the regular advance is made, the siege opened in due form, and the citadel successfully entered by the principal party.

We have said thus much to prevent our fair neighbours of England and Scotland from imagining that because such a character as the Irish Matchmaker exists at all, Irishmen are personally deficient in that fluent energy which is so necessary to express the emotions of the tender passion. Addison has proved to the satisfaction of any rational mind that modesty and assurance are inseparable—that a blushing face may accompany a courageous, nay, a desperate heart—and that, on the contrary, an abundance of assurance may be associated with a very handsome degree of modesty. In love matters, I grant, modesty is the forte of an Irishman, whose character in this respect has been unconsciously hit off by the poet. Indeed he may truly be termed vultus ingenui puer, ingenuique pudoris; which means, when translated, that in looking for a wife an Irishman is “a boy of an easy face, and remarkable modesty.”

At the head of the Matchmakers, and far above all competitors, stands the Irish Midwife, of whose abilities in this way it is impossible to speak too highly. And let not our readers imagine that the duties which devolve upon her, as well as upon matchmakers in general, are slight or easily discharged. To conduct a matter of this kind ably, great tact, knowledge of character, and very delicate handling, are necessary. To be incorruptible, faithful to both parties, not to give offence to either, and to obviate detection in case of secret bias or partiality, demand talents of no common order. The amount of fortune is often to be regulated—the good qualities of the parties placed in the best, or, what is often still more judicious, in the most suitable light—and when there happens to be a scarcity of the commodity, it must be furnished from her own invention. The miser is to be softened, the contemptuous tone of the purse-proud bodagh lowered without offence, the crafty cajoled, and sometimes the unsuspecting overreached. Now, all this requires an able hand, as matchmaking in general among the Irish does. Indeed I question whether the wiliest politician that ever attempted to manage a treaty of[Pg 117] peace between two hostile powers could have a more difficult card to play than often falls to the lot of the Irish Matchmaker.

The Midwife, however, from her confidential intercourse with the sex, and the respect with which both young and old of them look upon her, is peculiarly well qualified for the office. She has seen the youth shoot up and ripen into the young man—she has seen the young man merged into the husband, and the husband very frequently lost in the wife. Now, the marks and tokens by which she noted all this are as perceptible in the young of this day as they were in the young of fifty years ago; she consequently knows from experience how to manage each party, so as to bring about the consummation which she so devoutly wishes.

Upon second thoughts, however, we are inclined to think after all that the right of precedence upon this point does not exclusively belong to the Midwife; or at least, that there exists another person who contests it with her so strongly that we are scarcely capable of determining their respective claims: this is the Cosherer. The Cosherer in Ireland is a woman who goes from one relation’s house to another, from friend to friend, from acquaintance to acquaintance—is always welcome, and uniformly well treated. The very extent of her connexions makes her independent; so that if she receives an affront, otherwise a cold reception, from one, she never feels it to affect her comfort, but on the contrary carries it about with her in the shape of a complaint to the rest, and details it with such a rich spirit of vituperative enjoyment, that we believe in our soul some of her friends, knowing what healthful occupation it gives her, actually affront her from pure kindness. The Cosherer is the very impersonation of industry. Unless when asleep, no mortal living ever saw her hands idle. Her principal employment is knitting; and whether she sits, stands, or walks, there she is with the end of the stocking under her arm, knit, knit, knitting. She also sews and quilts; and whenever a quilting is going forward, she can tell you at once in what neighbour’s house the quilting-frame was used last, and where it is now to be had; and when it has been got, she is all bustle and business, ordering and commanding about her—her large red three-cornered pincushion hanging conspicuously at her side, a lump of chalk in one hand, and a coil of twine in the other, ready to mark the pattern, whether it be wave, square, or diamond.

The Cosherer is always dressed with neatness and comfort, but generally wears something about her that reminds one of a day gone by, and may be considered as the lingering remnant of some old custom that has fallen into disuse. This, slight as it is, endears her to many, for it stands out as the memorial of some old and perhaps affecting associations, which at its very appearance are called out from the heart in which they were slumbering.

It is impossible to imagine a happier life than that of the Cosherer. She has evidently no trouble, no care, no children, nor any of the various claims of life, to disturb or encumber her. Wherever she goes she is made, and finds herself, perfectly at home. The whole business of her life is carrying about intelligence, making and projecting matches, singing old songs and telling old stories, which she frequently does with a feeling and unction not often to be met with. She will sing you the different sets and variations of the old airs, repeat the history and traditions of old families, recite ranns, interpret dreams, give the origin of old local customs, and tell a ghost story in a style that would make your hair stand on end. She is a bit of a doctress, too—an extensive herbalist, and is very skilful and lucky among children. In short, she is a perfect Gentleman’s Magazine in her way—a regular repertory of traditionary lore, a collector and distributor of social antiquities, dealing in every thing that is timeworn or old, and handling it with such a quiet and antique air, that one would imagine her life to be a life not of years but of centuries, and that she had passed the greater portion of it, long as it was, in “wandering by the shores of old romance.”

Such a woman the reader will at once perceive is a formidable competitor for popular confidence with the Midwife. Indeed there is but one consideration alone upon which we would be inclined to admit that the latter has any advantage over her—and it is, that she is the Midwife; a word which is a tower of strength to her, not only against all professional opponents, but against such analogous characters as would intrude even upon any of her subordinate or collateral offices. As matchmakers, it is extremely difficult to decide between her and the Cosherer; so much so, indeed, that we are disposed to leave the claim for priority undetermined. In this respect each pulls in the same harness; and as they are so well matched, we will allow them to jog on side by side, drawing the youngsters of the neighbouring villages slowly but surely towards the land of matrimony.

In humble country life, as in high life, we find in nature the same principles and motives of action. Let not the speculating mother of rank, nor the husband-hunting dowager, imagine for a moment that the plans, stratagems, lures, and trap-falls, with which they endeavour to secure some wealthy fool for their daughters, are not known and practised—ay, and with as much subtlety and circumvention too—by the very humblest of their own sex. In these matters they have not one whit of superiority over the lowest, sharpest, and most fraudulent gossip of a country village, where the arts of women are almost as sagaciously practised, and the small scandal as ably detailed, as in the highest circles of fashion.

The third great master of the art of matchmaking is the Shanahus, who is nothing more or less than the counterpart of the Cosherer; for as the Cosherer is never of the male sex, so the Shanahus is never of the female. With respect to their habits and modes of life, the only difference between them is, that as the Cosherer is never idle, so the Shanahus never works; and the latter is a far superior authority in old popular prophecy and genealogy. As a matchmaker, however, the Shanahus comes infinitely short of the Cosherer; for the truth is, that this branch of diplomacy falls naturally within the manœuvring and intriguing spirit of a woman.

Our readers are not to understand that in Ireland there exists, like the fiddler or dancing-master, a distinct character openly known by the appellation of matchmaker. No such thing. On the contrary, the negotiations they undertake are all performed under false colours. The business, in fact, is close and secret, and always carried on with the profoundest mystery, veiled by the sanction of some other ostensible occupation.

One of the best specimens of the kind we ever met was old Rose Mohan, or, as she was called, Moan, a name, we doubt, fearfully expressive of the consequences which too frequently followed her own negociations. Rose was a tidy creature of middle size, who always went dressed in a short crimson cloak much faded, a striped red and blue drugget petticoat, and a heather-coloured gown of the same fabric. When walking, which she did with the aid of a light hazel staff hooked at the top, she generally kept the hood of the cloak over her head, which gave to her whole figure a picturesque effect; and when she threw it back, one could not help admiring how well her small but symmetrical features agreed with the dowd cap of white linen, with a plain muslin border, which she wore. A pair of blue stockings and sharp-pointed shoes high in the heels completed her dress. Her features were good-natured and Irish; but there lay over the whole countenance an expression of quickness and sagacity, contracted no doubt by a habitual exercise of penetration and circumspection. At the time I saw her she was very old, and I believe had the reputation of being the last in that part of the country who was known to go about from house to house spinning on the distaff, an instrument which has now passed away, being more conveniently replaced by the spinning-wheel.

The manner and style of Rose’s visits were different from those of any other who could come to a farmer’s house, or even to an humble cottage, for to the inmates of both were her services equally rendered. Let us suppose, for instance, the whole female part of a farmer’s family assembled of a summer evening about five o’clock, each engaged in some domestic employment: in runs a lad who has been sporting about, breathlessly exclaiming, whilst his eyes are lit up with delight, “Mother! mother! here’s Rose Moan coming down the boreen!” “Get out, avick; no, she’s not.” “Bad cess to me but she is; that I may never stir if she isn’t! Now!” The whole family are instantly at the door to see if it be she, with the exception of the prettiest of them all, Kitty, who sits at her wheel, and immediately begins to croon over an old Irish air which is sadly out of tune; and well do we know, notwithstanding the mellow tones of that sweet voice, why it is so, and also why that youthful cheek in which health and beauty meet, is now the colour of crimson.

“Oh, Rosha, acushla, cead millie failte ghud! (Rose, darlin’, a hundred thousand welcomes to you!) Och, musha, what kep you away so long, Rose? Sure you won’t lave us this month o’ Sundays, Rose?” are only a few of the cordial expressions of hospitality and kindness with which she is received. But Kitty, whose cheek but a moment ago was carmine, why is it now pale as the lily?

“An’ what news, Rose?” asks one of her sisters; “sure you’ll tell us every thing; won’t you?”

“Throth, avillish, I have no bad news, any how—an’ as to tellin’ you all—Biddy, lhig dumh, let me alone. No, I have no bad news, God be praised, but good news.”

Kitty’s cheek is again crimson, and her lips, ripe and red as cherries, expand with the sweet soft smile of her country, exhibiting a set of teeth for which many a countess would barter thousands, and giving out a breath more delicious than the fragrance of a summer meadow. Oh, no wonder, indeed, that the kind heart of Rose contains in its recesses a message to her as tender as ever was transmitted from man to woman!

“An’, Kitty, acushla, where’s the welcome from you, that’s my favourite? Now don’t be jealous, childre; sure you all know she is, an’ ever an’ always was.”

“If it’s not upon my lips, it’s in my heart, Rose, an’ from that heart you’re welcome!”

She rises up and kisses Rose, who gives her one glance of meaning, accompanied by the slightest imaginable smile, and a gentle but significant pressure of the hand, which thrills to her heart and diffuses a sense of ecstacy through her whole spirit. Nothing now remains but the opportunity, which is equally sought for by Rose and her, to hear without interruption the purport of her lover’s communication; and this we leave to lovers to imagine.

In Ireland, however odd it may seem, there occur among the very poorest classes some of the hardest and most penurious bargains in matchmaking that ever were heard of or known. Now, strangers might imagine that all this close higgling proceeds from a spirit naturally near and sordid, but it is not so. The real secret of it lies in the poverty and necessity of the parties, and chiefly in the bitter experience of their parents, who, having come together in a state of destitution, are anxious, each as much at the expense of the other as possible, to prevent their children from experiencing the same privation and misery which they themselves felt. Many a time have matches been suspended or altogether broken off because one party refuses to give his son a slip of a pig, or another his daughter a pair of blankets; and it was no unusual thing for a matchmaker to say, “Never mind; I have it all settled but the slip.” One might naturally wonder why those who are so shrewd and provident upon this subject do not strive to prevent early marriages where the poverty is so great. So unquestionably they ought, but it is a settled usage of the country, and one too which Irishmen have never been in the habit of considering as an evil. We have no doubt that if they once began to reason upon it as such, they would be very strongly disposed to check a custom which has been the means of involving themselves and their unhappy offspring in misery, penury, and not unfrequently in guilt itself.

Rose, like many others in this world who are not conscious of the same failing, smelt strongly of the shop; in other words, her conversation had a strong matrimonial tendency. No two beings ever lived so decidedly antithetical to each other in this point of view as the Matchmaker and the Keener. Mention the name of an individual or a family to the Keener, and the medium through which her memory passes back to them is that of her professed employment—a mourner at wakes and funerals.

“Don’t you know young Kelly of Tamlaght?”

“I do, avick,” replies the Keener, “and what about him?”

“Why, he was married to-day mornin’ to ould Jack M’Cluskey’s daughter.”

“Well, God grant them luck an’ happiness, poor things! I do indeed remember his father’s wake an’ funeral well—ould Risthard Kelly of Tamlaght—a dacent corpse he made for his years, an’ well he looked. But indeed I knewn by the colour that sted in his checks, an’ the limbs remainin’ soople for the twenty-four hours afther his departure, that some of the family ’ud follow him afore the year was out: an’ so she did. The youngest daughter, poor thing, by raison of a could she got, over-heatin’ herself at a dance, was stretched beside him that very day was eleven months; and God knows it was from the heart my grief came for her—to see the poor handsome colleen laid low so soon. But when a gallopin’ consumption sets in, avourneen, sure we all know what’s to happen. In Crockaniska churchyard they sleep—the Lord make both their beds in heaven this day!” The very reverse of this, but at the same time as inveterately professional, was Rose Moan.

“God save you, Rose.”

“God save you kindly, avick. Eh!—let me look at you. Aren’t you red Billy M’Guirk’s son from Ballagh?”

“I am, Rose. An’, Rose, how is yourself an’ the world gettin’ an?”

“Can’t complain, dear, in such times. How are yez all at home, alanna?”

“Faix, middlin’ well, Rose, thank God an’ you.—You heard of my granduncle’s death, big Ned M’Coul?”

“I did, avick, God rest him. Sure it’s well I remimber his weddin’, poor man, by the same atoken that I know one that helped him on wid it a thrifle. He was married in a blue coat and buckskins, an’ wore a scarlet waistcoat that you’d see three miles off. Oh, well I remimber it. An’ whin he was settin’ out that mornin’ to the priest’s house, ‘Ned,’ says I, an’ I fwhishspered him, ‘dhrop a button on the right knee afore you get the words said.’ ‘Thighum,’ said he, wid a smile, an’ he slipped ten thirteens into my hand as he spoke. ‘I’ll do it,’ said he, ‘and thin a fig for the fairies!’—becase you see if there’s a button of the right knee left unbuttoned, the fairies—this day’s Friday, God stand betune us and harm!—can do neither hurt nor harm to sowl or body, an’ sure that’s a great blessin’, avick. He left two fine slips o’ girls behind him.”

“He did so—as good-lookin’ girls as there’s in the parish.”

“Faix, an’ kind mother for them, avick. She’ll be marryin’ agin, I’m judgin’, she bein’ sich a fresh good-lookin’ woman.”

“Why, it’s very likely, Rose.”

“Throth it’s natural, achora. What can a lone woman do wid such a large farm upon her hands, widout having some one to manage it for her, an’ prevint her from bein’ imposed on? But indeed the first thing she ought to do is to marry off her two girls widout loss of time, in regard that it’s hard to say how a stepfather an’ thim might agree; and I’ve often known the mother herself, when she had a fresh family comin’ an her, to be as unnatural to her fatherless childre as if she was a stranger to thim, and that the same blood did’nt run in their veins. Not saying that Mary M’Coul will or would act that way by her own; for indeed she’s come of a kind ould stock, an’ ought to have a good heart. Tell her, avick, when you see her, that I’ll spind a day or two wid her—let me see—to-morrow will be Palm Sunday—why, about the Aisther holidays.”

“Indeed I will, Rose, with great pleasure.”

“An’ fwhishsper, dear, jist tell her that I’ve a thing to say to her—that I had a long dish o’ discoorse about her wid a friend o’ mine. You wont forget now?”

“Oh the dickens a forget!”

“Thank you, dear: God mark you to grace, avourneen! When you’re a little ouldher, maybe I’ll be a friend to you yet.”

This last intimation was given with a kind of mysterious benevolence, very visible in the complacent shrewdness of her face, and with a twinkle in the eye, full of grave humour and considerable self-importance, leaving the mind of the person she spoke to in such an agreeable uncertainty as rendered it a matter of great difficulty to determine whether she was serious or only in jest, but at all events throwing the onus of inquiry upon him.

The ease and tact with which Rose could involve two young persons of opposite sexes in a mutual attachment, were very remarkable. In truth, she was a kind of matrimonial incendiary, who went through the country holding her torch now to this heart and again to that—first to one and then to another, until she had the parish more or less in a flame. And when we consider the combustible materials of which the Irish heart is composed, it is no wonder indeed that the labour of taking the census in Ireland increases at such a rapid rate during the time that elapses between the periods of its being made out. If Rose, for instance, met a young woman of her acquaintance accidentally—and it was wonderful to think how regularly these accidental meetings took place—she would address her probably somewhat as follows:—

“Arra, Biddy Sullivan, how are you, a-colleen?”

“Faix, bravely, thank you, Rose. How is yourself?”

“Indeed, thin, sorra bit o’ the health we can complain of, Bhried, barrin’ whin this pain in the back comes upon us. The last time I seen your mother, Biddy, she was complainin’ of a weid.[6] I hope she’s betther, poor woman?”

“Hut! bad scran to the thing ails her! She has as light a foot as e’er a one of us, an’ can dance ‘Jackson’s mornin’ brush’ as well as ever she could.”

“Throth, an’ I’m proud to hear it. Och! och! ‘Jackson’s mornin’ brush!’ and it was she that could do it. Sure I remimber[Pg 119] her wedding-day like yestherday. Ay, far an’ near her fame wint as a dancer, an’ the clanest-made girl that ever came from Lisbuie. Like yestherday do I remimber it, an’ how the squire himself an’ the ladies from the Big House came down to see herself an’ your father, the bride and groom—an’ it wasn’t on every hill head you’d get sich a couple—dancin’ the same ‘Jackson’s mornin’ brush.’ Oh! it was far and near her fame wint for dancin’ that.—An’ is there no news wid you, Bhried, at all at all?”

“The sorra word, Rose: where ud I get news? Sure it’s yourself that’s always on the fut that ought to have the news for us, Rose alive.”

“An’ maybe I have too. I was spaikin’ to a friend o’ mine about you the other day.”

“A friend o’ yours, Rose! Why, what friend could it be?”

“A friend o’ mine—ay, an’ of yours too. Maybe you have more friends than you think, Biddy—and kind ones too, as far as wishin’ you well goes, ’tany rate. Ay have you, faix, an’ friends that e’er a girl in the parish might be proud to hear named in the one day wid her. Awouh!”

“Bedad we’re in luck, thin, for that’s more than I knew of. An’ who may these great friends of ours be, Rose?”

“Awouh! Faix, as dacent a boy as ever broke bread the same boy is, ‘and,’ says he, ‘if I had goold in bushelfuls, I’d think it too little for that girl;’ but, poor lad, he’s not aisy or happy in his mind in regard o’ that. ‘I’m afeard,’ says he, ‘that she’d put scorn upon me, an’ not think me her aiquals. An’ no more I am,’ says he again, ‘for where, afther all, would you get the likes of Biddy Sullivan?’—Poor boy! throth my heart aches for him!”

“Well, can’t you fall in love wid him yourself, Rose, whoever he is?”

“Indeed, an’ if I was at your age, it would be no shame to me to do so; but, to tell you the thruth, the sorra often ever the likes of Paul Heffernan came acrass me.”

“Paul Heffernan! Why, Rose,” replied Biddy, smiling with the assumed lightness of indifference, “is that your beauty? If it is, why, keep him, an’ make much of him.”

“Oh, wurrah! the differ there is between the hearts an’ tongues of some people—one from another—an’ the way they spaik behind others’ backs! Well, well, I’m sure that wasn’t the way he spoke of you, Biddy; an’ God forgive you for runnin’ down the poor boy as you’re doin’. Trogs! I believe you’re the only girl would do it.”

“Who, me! I’m not runnin’ him down. I’m neither runnin’ him up nor down. I have neither good nor bad to say about him—the boy’s a black sthranger to me, barrin’ to know his face.”

“Faix, an’ he’s in consate wid you these three months past, an’ intinds to be at the dance on Friday next, in Jack Gormly’s new house. Now, good bye, alanna; keep your own counsel till the time comes, an’ mind what I said to you. It’s not behind every ditch the likes of Paul Heffernan grows. Bannaght lhath! My blessin’ be wid you!”

Thus would Rose depart just at the critical moment, for well she knew that by husbanding her information and leaving the heart something to find out, she took the most effectual steps to excite and sustain that kind of interest which is apt ultimately to ripen, even from its own agitation, into the attachment she is anxious to promote.

The next day, by a meeting similarly accidental, she comes in contact with Paul Heffernan, who, honest lad, had never probably bestowed a thought upon Biddy Sullivan in his life.

“Morrow ghud, Paul!—how is your father’s son, ahager?”

“Morrow ghuteha, Rose!—my father’s son wants nothin’ but a good wife, Rosha.”

“An’ it’s not every set day or bonfire night that a good wife is to be had, Paul—that is, a good one, as you say; for, throth, there’s many o’ them in the market sich as they are. I was talkin’ about you to a friend of mine the other day—an’, trogs, I’m afeard you’re not worth all the abuse we gave you.”

“More power to you, Rose! I’m oblaged to you. But who is the friend in the manetime?”

“Poor girl! Throth, when your name slipped out an her, the point of a rush would take a drop of blood out o’ her cheek, the way she crimsoned up. ‘An’, Rose,’ says she, ‘if ever I know you to breathe it to man or mortual, my lips I’ll never open to you to my dyin’ day.’ Trogs, whin I looked at her, an’ the tears standin’ in her purty black eyes, I thought I didn’t see a betther favoured girl, for both face and figure, this many a day, than the same Biddy Sullivan.”

“Biddy Sullivan! Is that long Jack’s daughter of Cargah?”

“The same. But, Paul, avick, if a syllable o’ what I tould you——”

“Hut, Rose! honour bright! Do you think me a stag, that I’d go and inform on you?”

“Fwhishsper, Paul; she’ll be at the dance on Friday next in Jack Gormly’s new house. So bannaght lhath, an’ think o’ what I betrayed to you.”

Thus did Rose very quietly and sagaciously bind two young hearts together, who probably might otherwise have never for a moment even thought of each other. Of course, when Paul and Biddy met at the dance on the following Friday, the one was the object of the closest attention to the other; and each being prepared to witness strong proofs of attachment from the opposite party, every thing fell out exactly according to their expectations.

Sometimes it happens that a booby of a fellow during his calf love will employ a male friend to plead his suit with a pretty girl, who, if the principal party had spunk, might be very willing to marry him. To the credit of our fair countrywomen, however, be it said, that in scarcely one instance out of twenty does it happen, or has it ever happened, that any of them ever fails to punish the faint heart by bestowing the fair lady upon what is called the blackfoot or spokesman whom he selects to make love for him. In such a case it is very naturally supposed that the latter will speak two words for himself and one for his friend, and indeed the result bears out the supposition. Now, nothing on earth gratifies the heart of the established Matchmaker so much as to hear of such a disaster befalling a spoony. She exults over his misfortune for months, and publishes his shame to the uttermost bounds of her own little world, branding him as “a poor pitiful crature, who had not the courage to spaik up for himself or to employ them that could.” In fact, she entertains much the same feeling against him that a regular physician would towards some weak-minded patient, who prefers the knavish ignorance of a quack to the skill and services of an able and educated medical practitioner.

Characters like Rose are fast disappearing in Ireland; and indeed in a country where the means of life were generally inadequate to the wants of the population, they were calculated, however warmly the heart may look back upon the memory of their services, to do more harm than good, by inducing young folks to enter into early and improvident marriages. They certainly sprang up from a state of society not thoroughly formed by proper education and knowledge—where the language of a people, too, was in many extensive districts in such a state of transition as in the interchange of affection to render an interpreter absolutely necessary. We have ourselves witnessed marriages where the husband and wife spoke the one English and the other Irish, each being able with difficulty to understand the other. In all such cases Rose was invaluable. She spoke Irish and English fluently, and indeed was acquainted with every thing in the slightest or most remote degree necessary to the conduct of a love affair, from the first glance up until the priest had pronounced the last words—or, to speak more correctly, until “the throwing of the stocking.”

Rose was invariably placed upon the hob, which is the seat of comfort and honour at a farmer’s fireside, and there she sat neat and tidy, detailing all the news of the parish, telling them how such a marriage was one unbroken honeymoon—a sure proof by the way that she herself had a hand in it—and again, how another one did not turn out well, and she said so; “there was always a bad dhrop in the Haggarties; but, my dear, the girl herself was for him; so as she made her own bed she must lie in it, poor thing. Any way, thanks be to goodness I had nothing to do wid it!”

Rose was to be found in every fair and market, and always at a particular place at a certain hour of the day, where the parties engaged in a courtship were sure to meet her on these occasions. She took a chirping glass, but never so as to become unsteady. Great deference was paid to every thing she said; and if this was not conceded to her, she extorted it with a high hand. Nobody living could drink a health with half the comic significance that Rose threw into her eye when saying, “Well, young couple, here’s everything as you wish it!”

Rose’s motions from place to place were usually very slow, and for the best reason in the world, because she was frequently interrupted. For instance, if she met a young man on her way, ten to one but he stood and held a long and earnest conversation with her; and that it was both important and confidential, might easily be gathered from the fact that[Pg 120] whenever a stranger passed, it was either suspended altogether, or carried on in so low a tone as to be inaudible. This held equally good with the girls. Many a time have I seen them retracing their steps, and probably walking back a mile or two, all the time engaged in discussing some topic evidently of more than ordinary interest to themselves. And when they shook hands and bade each other good bye, heavens! at what a pace did the latter scamper homewards across fields and ditches, in order to make up for the time she had lost!

Nobody ever saw Rose receive a penny of money, and yet when she took a fancy, it was beyond any doubt that she has often been known to assist young folks in their early struggles; but in no instance was the slightest aid ever afforded to any one whose union she had not herself been instrumental in bringing about. As to the when and the how she got this money, and the great quantity of female apparel which she was known to possess, we think we see our readers smile at the simplicity of those who may not be able to guess the several sources from whence she obtained it.

One other fact we must mention before we close this sketch of her character. There were some houses—we will not, for we dare not, say how many—into which Rose was never seen to enter. This, however, was not her fault. Every one knew that what she did, she did always for the best; and if some small bits of execration were occasionally levelled at her, it was not more than the parties levelled at each other. All marriages cannot be happy; and indeed it was a creditable proof of Rose Moan’s sagacity that so few of those effected through her instrumentality were unfortunate.

Poor Rose! matchmaking was the great business of your simple but not absolutely harmless life. You are long since, we trust, gone to that happy place where there are neither marryings nor givings in marriage, but where you will have a long Sabbath from your old habits and tendencies. We love for more reasons than either one or two to think of your faded crimson cloak, peaked shoes, hazel staff, clear grey eye, and nose and chin that were so full of character. As you used to say yourself, bannaght lhath!—my blessing be with you!

[6] A feverish cold.

One result of perusing such interesting papers on “the Intellectuality of Domestic Animals” as that which lately appeared in the Dublin University Magazine, should be the publication of similar facts; another, the promotion of that kindness towards the inferior creation which is still, alas! so sparingly manifested. I therefore propose stuffing a cranny of the Irish Penny Journal with a few particulars relating, firstly, to the maternal and filial piety of the cat; secondly, to the humanity (or, psychologically speaking, brutality) of the same animal. Of the facts illustrative of the former virtues I was an eye-witness—those illustrative of the latter I had from a member of the family in which they occurred.

In my early home two cats, a mother and a son, formed part of the establishment. The former, a dark-grey matron, rejoiced in the euphonious name of Smut—the colour of the latter may be inferred from his appellation, Fox. Smut was, to be brief, the most lady-like cat I ever saw; Fox was a huge Dan Donnelly of a brute, a very hero of the slates, and the terror of all the cats in the neighbourhood, save one; he walloped them right and left; and many a smirking sylph of the gutters, wont to pick her steps daintily to avoid all possible contact with the wet, was seen to scamper away screaming when Fox appeared in view, for truth obliges me to record that he spared neither age nor sex. Nor was he formidable to the brute creation alone—humanity often suffered under his visitations. There was no keener forager among the larders and pantries of the neighbourhood. A poor dancing-master who had a way of leaving his window open was most frequently victimized; for as the said window was convenient to the low roof of a back house, our hero used to quietly walk in and purvey to his liking. In the recess of a chimney, and several feet above the roof of our house, was a kind of small platform, where Master Fox was usually pleased to regale himself on his ill-gotten gains. One day I saw him with a calf’s or lamb’s pluck in his mouth, twice as long as himself, darting aloft towards his refectory. The weight of the booty several times dragged him back; but he persevered till he gained his point: it was a sight ludicrous beyond all imagining.

But as it was not every day Master Fox could mulct the circumambient dancing-master in a beef-steak or a calf’s pluck, he often returned home hungry; and I am now come to the point of proving the “intellectuality” of Madam Smut, as evidenced in her maternal piety. Within the kitchen-door lay a mat, in a hole in which she daily hid a portion of her lights. She was generally dozing before the fire when her son came in for the night, and whenever I happened to follow him and watch her movements, she invariably looked up to see whether he had scented the provender: and when satisfied on that point, coiled herself up to sleep again. But her maternal tenderness never interfered with her matronly dignity. Woe betide Fox, if, in proceeding to take his place at the fire, he attempted to pass between her and it. She would instantly spring up and deal him a dab, which prevented for that time a repetition of the indecorum. I have seen him steal most cautiously along the forbidden path in the presumption that she was asleep, but I do not remember to have ever seen him effect a passage. I have said that he leathered all the cats about him save one—that one was his mother. Determined pugilist and fire-eater as he was, he never returned the dab she gave him.

The fact of which I was only an ear-witness may be briefly related. A lady of this city observing one day a wretched kitten which had been ruthlessly flung into the street before her residence, had it taken into the house and carefully tended. Some time after, when it had grown into a thorough-bred mouser, a strange cat with a broken leg hobbled into the yard, where it was discovered by the foundling, which immediately took charge of it, and regularly allotted to the sufferer a portion of its own daily food till it was sufficiently recovered to shift for itself.

As a warm friend of the inferior creation, I was much pleased to find their cause pleaded towards the close of the article, which gave rise to the present sketch, and a just encomium passed on the author of “the Rights of Animals.” And much was I gratified to find that the same cause appears to maintain an abiding interest in the bosom of the first of living poets. “C. O.” alludes as follows to a conversation he had with Mr Wordsworth on the subject:—“I remember an observation made to me by one of the most gifted of the human race—one of the stars of this generation—the poet of nature and of feeling—the good and the great Mr Wordsworth. Having the honour of a conversation with him after he had made a tour through Ireland, I in the course of it asked what was the thing that most struck his observation here as making us differ from the English; and he without hesitation said it was the ill-treatment of our horses: that his soul was often, too often, sick within him at the way in which he saw these creatures of God abused.” One evening, which I had the happiness of spending at Rydal Mount, the very same subject was broached by Mr W. Defend my countrymen I could not, but I parried the attack by showing that other segments of the united kingdom had little right to boast over them in this particular. This I proved by adverting to the notorious cat-skinning of London—a horror unknown in Ireland, bad as we are—and to certain atrocious cruelties which had just been perpetrated on some horses in Sutherland (though I must confess that I know too little of Scotland to pronounce whether its national character is tarnished by cruelty to animals or not). And much was I surprised when the son of the poet threw discredit on the character of one of the first of London newspapers, from which I had cited a recent case in proof of my assertion. It was in 1833 I visited Rydal Mount. Should this paper reach the eye of Mr W. jun., he may find my statement corroborated, and the perpetration of the barbarous trade demonstrated, by referring to the case of Elizabeth Rogerson, an old offender, who in 1839 was condemned to the ridiculously lenient penalty of two months’ imprisonment for the crime, without hard labour. A diametrically opposite opinion respecting the treatment of horses in Ireland was once expressed to me by another English gentleman of some celebrity in the religious world. He passed an encomium on the kindness to animals observable in this country, from the habit he had noticed among the drivers of jaunting-cars, during his short stay in Dublin, of feeding their horses from their hands with a wisp of hay at leisure moments—a pitch of humanity just equivalent to that of greasing the wheels of their vehicles.

Printed and published every Saturday by GUNN and CAMERON, No. 6, Church Lane, College Green, Dublin; and sold by all Booksellers.