Title: Two Dianas in Somaliland: The Record of a Shooting Trip

Author: Agnes Herbert

Release date: April 7, 2017 [eBook #54501]

Most recently updated: February 25, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger from page images generously

provided by the Internet Archive

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I—WE SET OUT FOR SOMALILAND

CHAPTER III—THE STARTING OF THE GREAT TREK

CHAPTER VI—BENIGHTED IN THE JUNGLE

CHAPTER VII—ANOTHER UNCOMFORTABLE NIGHT

CHAPTER IX—DEATH OF “THE BARON”

CHAPTER X—WE MEET “THE OPPOSITION”

CHAPTER XI—AN OASIS IN THE DESERT

CHAPTER XII—OUR BUTLER LEVANTS

CHAPTER XIII—WE CROSS THE MAREHAN

CHAPTER XIV—WE REACH A REAL LAKE

CHAPTER XV—ANOTHER GAP IN OUR RANKS

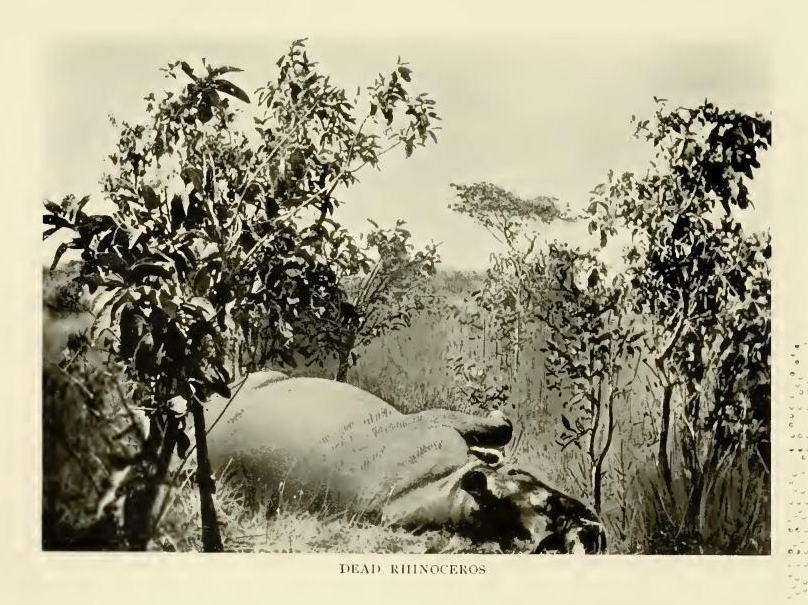

CHAPTER XVI—CECILY SHOOTS A RHINOCEROS

CHAPTER XVIII—A JOUST WITH A BULL ORYX

CHAPTER XX—END OF THE GREAT SHIKAR

This weaves itself perforce into my business

King Lear

It is not that I imagine the world is panting for another tale about a shoot. I am aware that of the making of sporting books there is no end. Simply—I want to write. And in this unassuming record of a big shoot, engineered and successfully carried through by two women, there may be something of interest; it is surely worth more than a slight endeavour to engage the even passing interest of one person of average intelligence in these days of universal boredom.

I don’t know whether the idea of our big shoot first emanated from my cousin or myself. I was not exactly a tenderfoot, neither was she. We had both been an expedition to the Rockies at a time when big game there was not so hard to find, but yet less easy to get at. We did not go to the Rockies with the idea of shooting, our sole raison d’être being to show the heathen Chinee how not to cook; but incidentally the charm of the chase captured us, and we exchanged the gridiron for the gun. So at the end of March 190-we planned a sporting trip to Somaliland—very secretly and to ourselves, for women hate being laughed at quite as much as men do, and that is very much indeed.

My cousin is a wonderful shot, and I am by no means a duffer with a rifle. As to our courage—well, we could only trust we had sufficient to carry us through. We felt we had, and with a woman intuition is everything. If she feels she is not going to fail, you may take it from me she won’t. Certainly it is one thing to look a lion in the face from England to gazing at him in Somaliland. But we meant to meet him somehow.

Gradually and very carefully we amassed our stores, and arranged for their meeting us in due course. We collected our kit, medicines, and a thousand and one needful things, and at last felt we had almost everything, and yet as little as possible. Even the little seemed too much as we reflected on the transport difficulty. We sorted our things most carefully—I longed for the floor-space of a cathedral to use as a spreading-out ground—and glued a list of the contents of each packing-case into each lid.

To real sportsmen I shall seem to be leaving the most important point to the last—the rifles, guns, and ammunition. But, you see, I am only a sportswoman by chance, not habit. I know it is the custom with your born sportsman to place his weapons first, minor details last. “Nice customs curtsey to great kings,” they say, and so it must be here. For King Circumstance has made us the possessors of such wondrous modern rifles, &c., as to leave us no reason to think of endeavouring to supply ourselves with better. We, fortunately, have an uncle who is one of the greatest shikaris of his day, and his day has only just passed, his sun but newly set. A terribly bad mauling from a lion set up troubles in his thigh, and blood poisoning finally ended his active career. He will never hunt again, but he placed at our disposal every beautiful and costly weapon he owned, together with his boundless knowledge. He insisted on our taking many things that would otherwise have been left behind, and his great trust in our powers inspired us with confidence. It is to his help we owe the entire success of our expedition.

It would be an impertinence for a tyro like myself to offer any remarks on the merits or demerits of any rifle. Not only do the fashions change almost as quickly as in millinery, not only do great shikaris advise, advertise, and adventure with any weapon that could possibly be of service to anyone, but my knowledge, even after the experience gained in our long shoot, is confined to the very few firearms we had with us. They might not have met with unqualified approval from all men; they certainly served us well. After all, that is the main point.

Our battery consisted of:

Three 12-bore rifles.

Two double-barrelled hammerless ejecting .500 Expresses.

One .35 Winchester.

Two small .22 Winchesters.

One single-barrel .350.

One 410 bore collector’s gun.

A regular olla podrida in rifles.

My uncle selected these from his armoury as being the ones of all others he would feel safest in sending us out with. There may, in the opinion of many, be much more suitable ones for women to use, but, speaking as one who had the using of them, I must say I think the old shikari did the right thing, and if I went again the same rifles would accompany me.

My uncle is a small man, with a shortish arm, and therefore his reach about equalled ours, and his rifles might have been made for us.

We also towed about with us two immensely heavy shot guns. They were a great nuisance, merely adding to the baggage, and we never used them as far as I remember.

As we meant frequently to go about unescorted, a revolver or pistol seemed indispensable in the belt, and under any conditions such a weapon would be handy and give one a sense of security. On the advice of another great sportsman we equipped ourselves with a good shikar pistol apiece, 12-bore; and I used mine on one occasion very effectively at close quarters with an ard-wolf, so can speak to the usefulness and efficiency of the weapon.

It was the “cutting the ivy” season in Suburbia when we drove through it early one afternoon, and in front of every pill-box villa the suburban husband stood on a swaying ladder as he snipped away, all ora ora unmindful of the rampant domesticity of the sparrows. The fourteenth of February had long passed, and the fourteenth is to the birds what Easter Monday is to the lower orders, a general day for getting married.

A few days in town amid the guilty splendour of one of the caravan-serais in Northumberland Avenue were mostly spent in imbibing knowledge. My uncle never wearied of his subject, and it was to our interest to listen carefully. Occasionally he would wax pessimist, and express his doubts of our ability to see the trip through; but he was kind enough to say he knows no safer shot than myself. “Praise from Cæsar.” Though I draw attention to it that shouldn’t! The fragility of my physique bothered him no end. I assured him over and over that my appearance is nothing to go by, and that I am, as a matter of fact, a most wiry person.

This shoot of ours was no hurried affair. We had been meditating it for months, and had, to some extent, arranged all the difficult parts a long time before we got to the actual purchases of stores, and simple things of the kind. We had to obtain special permits to penetrate the Ogaden country and beyond to the Marehan and the Haweea, if we desired to go so far. Since the Treaty with King Menelik in 1897 the Ogaden and onwards is out of the British sphere of influence.

How our permits were obtained I am not at liberty to say; but without them we should have been forced to prance about on the outskirts of every part where game is abundant. By the fairy aid of these open sesames we were enabled to traverse the country in almost any part, and would have been passed from Mullah to Sheik, from Sheik to Mullah, had we not taken excellent care to avoid, as far as we could, the settled districts where these gentry reside. At one time all the parts we shot over were free areas, and open to any sportsman who cared to take on the possible dangers of penetrating the far interior of Somaliland, but now the hunting is very limited and prescribed. We were singularly fortunate, and owe our surprising good luck to that much maligned, useful, impossible to do without passport to everything worth having known as “influence.”

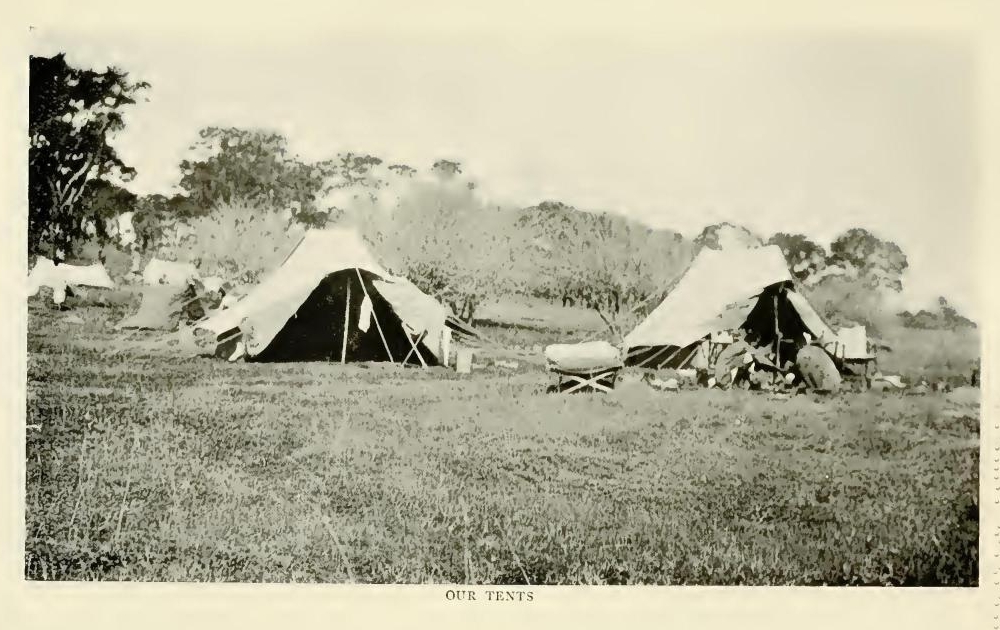

The tents we meant to use on the shoot were made for us to a pattern supplied. They were fitted with poles of bamboo, of which we had one to spare in case of emergencies. The ropes, by particular request, were of cotton, in contradistinction to hemp, which stretches so abominably.

Two skinning knives were provided, and some little whet-stones, an axe, a bill-hook, two hammers, a screwdriver—my vade mecum—nails, and many other needful articles. We trusted to getting a good many things at Berbera, but did not like to leave everything to the last. Our “canned goods” and all necessaries in the food line we got at the Army and Navy Stores. Field-glasses, compasses, and a good telescope our generous relative contributed.

They say that the best leather never leaves London, that there only can the best boots be had. This is as may be. Anyway the shooting boots made for us did us well, and withstood prodigious wear and tear.

The night before our departure we had a “Goodbye” dinner and, as a great treat, were taken to a music-hall. Of course it was not my first visit, but really, if I have any say in the matter again, it will be the last. Some genius—a man, of course—says, somewhere or other, women have no sense of humour—I wonder if he ever saw a crowd of holiday-making trippers exchanging hats—and I am willing to concede he must be right. I watched that show unmoved the while the vast audience rocked with laughter.

The pièce-de-résistance of the evening was provided by a “comic” singer, got up like a very-much-the-worse-for-wear curate, who sang to us about a girl with whom he had once been in love. Matters apparently went smoothly enough until one fateful day he discovered his inamorata’s nose was false, and, what seemed to trouble him more than all, was stuck on with cement. It came off at some awkward moment. This was meant to be funny. If such an uncommon thing happened that a woman had no nose, and more uncommon still, got so good an imitation as to deceive him as to its genuineness in the first place, it would not be affixed with cement. But allowing such improbabilities to pass in the sacred cause of providing amusement, surely the woman’s point of view would give us pause. It would be so awful for her in every way that it would quite swamp any discomfort the man would have to undergo. I felt far more inclined to cry than laugh, and the transcendent vulgarity of it all made one ashamed of being there.

The next item on the programme was a Human Snake, who promised us faithfully that he would dislocate his neck. He marched on to a gaudy dais, and after tying himself in sundry knots and things, suddenly jerked, and his neck elongated, swinging loosely from his body. It was a very horrid sight. An attendant stepped forward and told us the Human Snake had kept his promise. The neck was dislocated. My only feeling in the matter was a regret he had not gone a step farther and broken it. All this was because I have no sense of humour. I don’t like music-hall entertainments. I would put up with being smoked into a kipper if the performance rewarded one at all. It is so automatic, so sad. There is no joy, or freshness, or life about it. ’Tis a squalid way of earning money.

At last every arrangement was arranged, our clothes for the trip duly packed. Being women, we had naturally given much thought to this part of the affair. We said “Adieu” to our wondering and amazed relatives, who, with many injunctions to us to “write every day,” and requests that we should at all times abjure damp beds, saw us off en route for Berbera, via Aden, by a P. and O. liner.

I think steamer-travelling is most enjoyable—that is, unless one happens to be married, in which case there is no pleasure in it, or in much else for the matter of that. I have always noticed that the selfishness which dominates every man more or less, usually more, develops on board ship to an abnormal extent. They invariably contrive to get toothache or lumbago just as they cross the gangway to go aboard. This is all preliminary to securing the lower berth with some appearance of equity. What does it matter that the wife detests top berths, not to speak of the loss of dignity she must endure at the idea even of clambering up? Of course the husband does not ask her to take the top berth. No husband can ask his wife to make herself genuinely uncomfortable to oblige him. He has to hint. He hints in all kinds of ways—throws things about the cabin, and ejaculates parenthetically, “How am I to climb up there with a tooth aching like mine?” or “I shall be lamed for life with my lumbago if I have to get up to that height.”

Having placed the wife in the position of being an unfeeling brute if she insists on taking the lower berth for herself, there is nothing for it but to go on as though the top berth were the be-all of the voyage and her existence.

“Let me have the top berth, Percy,” she pleads; “you know how I love mountaineering.”

“Oh, very well. You may have it. Don’t take it if you don’t want it, or if you’d rather not. I should hate to seem selfish.”

And so it goes on. Then in the morning, in spite of comic papers to the contrary, the husband has to have first go-in at the looking-glass and the washing apparatus, which makes the wife late for breakfast and everything is cold.

Cecily and I shared a most comfortable cabin amidships, together with a Christian Science lady who lay in her berth most days crooning hymns to herself in between violent paroxysms of mal-de-mer. I always understood that in Christian Science you do not have to be ill if you do not want to. This follower of the faith was very bad indeed, and didn’t seem to like the condition of things much. We rather thought of questioning her on the apparent discrepancy, but judged it wiser to leave the matter alone. It is as well to keep on good terms with one’s cabin mate.

Nothing really exciting occurred on the voyage, but one of the passengers provided a little amusement by her management, or rather mismanagement, of an awkward affair. Almost as soon as we started I noticed we had an unusually pretty stewardess, and that a warrior returning to India appeared to agree with me. He waylaid her at every opportunity, and I often came on them whispering in corners of passages o’ nights. Of course it had nothing to do with me what the stewardess did, for I am thankful to say I did not require her tender ministrations on the voyage at all. Well, in the next cabin to ours was a silly little woman—I had known her for years—going out to join her husband, a colonel of Indian Lancers. She made the most never-ending fuss about the noise made by a small baby in the adjoining cabin. One night, very late, Mrs. R. could not, or would not, endure the din any longer, so decided to oust the stewardess from her berth in the ladies’ cabin, the stewardess to come to the vacated one next the wailing baby. All this was duly carried into effect, and the whole ship was in complete silence when the most awful shrieks rent the air. Most of the inhabitants of my corridor turned out, and all made their way to the ladies’ cabin, which seemed the centre of the noise. There we found the ridiculous Mrs. R. alone, and in hysterics. After a little, we could see for ourselves there was nothing much the matter. She gasped out that she had evicted the stewardess, and was just falling off to sleep when a tall figure appeared by the berth, clad in pale blue pyjamas—it seemed to vex her so that it was pale blue, and for the life of me I could not see why they were any worse than dark red—and calling her “Mabel, darling!” embraced her rapturously.

“And you know,” said Mrs. R. plaintively, “my name is not Mabel! It is Maud.”

In the uproar the intruder had of course escaped, but Mrs. R. unhesitatingly proclaimed him to be Captain H., the officer whom I had noticed at first. We discovered the stewardess sleeping peacefully, or making a very good imitation of it, and she was wakened up and again dislodged, whilst Mrs. R. prepared to put up with the wailing baby for the remains of the night.

Next morning the captain of the ship interviewed the warrior, who absolutely denied having been anywhere near the ladies’ cabin at the time mentioned, and aided by a youthful subaltern, who perjured himself like a man, proved a most convincing alibi. Matters went on until one day on deck Captain H. walked up to Mrs. R. and reproached her for saying he was the man who rudely disturbed her slumbers in the wee sma’ hours. She, like the inane creature she is, went straight to the skipper and reported that Captain H. was terrorising her. I heard that evening, as a great secret, that the warrior had been requested to leave the ship at Aden. Where the secret came in I don’t quite know, for the whole lot of us knew of it soon after.

Secret de deux,

Secret des dieux;

Secret de trois,

Secret de tous.

Do you know that?

I was not surprised to hear Captain H. casually remark at breakfast next morning that he thought of stopping off at Aden, as he had never been ashore there, and had ideas of exploring the Hinterland some time, and besides it was really almost foolish to pass a place so often and yet know it not at all. I went to his rescue, and said it was a most sound idea. I had always understood it was the proper thing to see Aden once and never again. He looked at me most gratefully, and afterwards showed us much kindness in many small ways.

Mrs. R. preened herself mightily on having unmasked a villain. She assured me the warrior’s reputation was damaged for all time. The silly little woman did not seem to grasp the fact that a man’s reputation is like a lobster’s claw: a new one can be grown every time the old one is smashed. In fact we had a lobster at home in the aquarium, and it hadn’t even gone to the trouble of dropping one reputation—I mean claw—but had three at once!

It was one of the quaintest things imaginable to watch the attitude of the various passengers towards the cause of all the trouble. A community of people shut up together on board ship become quite like a small town, of the variety where every one knows everyone else, and their business. Previous to the semi-subdued scandal Captain H. had been in great request. He was a fine-looking man, and a long way more versatile than most. Now many of the people who had painstakingly scraped acquaintance with him felt it necessary to look the other way as he passed. Others again—women, of course—tried to secure an introduction from sheer inquisitiveness.

The sole arbiter of what is what, a multum in parvo of the correct thing to do, we discovered in a young bride, a perfect tome of learning. I think—I thought so before I met this walking ethic of propriety—there is no doubt Mrs. Grundy is not the old woman she is represented to be, with cap and spectacles, though for years we have pictured her thus. It is all erroneous. Mrs. Grundy is a newly married youthful British matron of the middle class. There is no greater stickler for the proprieties living. Having possessed herself of a certificate that certifies respectability, she likes to know everyone else is hall-marked and not pinchbeck. She proposed to bring the romance of the stewardess and the officer before the notice of the directors of the company, and had every confidence in getting one or two people dismissed over it. All hail for the proprieties! This good lady markedly and ostentatiously cut the disgraced warrior, who was her vis-à-vis at table, and when I asked her why she considered a man guilty of anything until he had been proved beyond doubt to merit cutting, she looked at me with a supercilious eyebrow raised, and a world of pity for my ignorance in her tone as she answered firmly: “I must have the moral courage necessary to cut an acquaintance lacking principle.”

“Wouldn’t it be infinitely more courageous to stick to one?” I said, and left her.

We had a very narrow little padre on board too, going out to take on some church billet Mussoorie way. He was bent on collecting, from all of us who were powerless to evade him, enough money to set up a screen of sorts in his new tabernacle. Although he did not approve of the sweepstakes on the day’s run, he sacrificed his feeling sufficiently to accept a free share, and would ask us for subscriptions besides, as we lounged about the deck individually or in small groups, always opening the ball by asking our valueless opinions as to the most suitable subject—biblical, of course—for illustration. He came to me one day and asked me what I thought about the matter. Did I think Moses with his mother would make a good picture for a screen? I had no views at all, so had to speedily manufacture some. I gave it as my opinion that if a screen picture were a necessity Moses would certainly do as well as anybody else—in fact better. For, after all, Moses was the greatest leader of men the world has ever known. He engineered an expedition to freedom, and no man can do more than that.

But I begged the padre to give Moses his rightful mother at last. For the mother of Moses was not she who took all the credit for it. The mother of Moses was undoubtedly the Princess, his father some handsome Israelite, and that is why Moses was for ever in heart hankering after his own people, the Israelites. The Princess arranged the little drama of the bullrushes, most sweetly pathetic and tender of stories, arranged too that the baby should be found at the crucial moment, and then gave the little poem to the world to sing through the centuries.

I shocked the parson profoundly, and he never asked me to subscribe again. He was a narrow, bigoted little creature, and I should think has the church and the screen very much to himself by now. I went to hear him take service in the saloon on Sunday. He was quite the sort of padre that makes one feel farther off from heaven than when one was a boy.

I often wonder why so clever a man as Omar asked: “Why nods the drowsy worshipper outside?” He must have known the inevitable result had the drowsy worshipper gone in.

I fell asleep during the sermon, and only wakened up as it was about ending, just as the padre closed an impassioned harangue with “May we all have new hearts, may we all have pure hearts, may we all have good hearts, may we all have sweet hearts,” and the graceless Cecily says that my “Amen” shook the ship, which was, I need hardly tell you, “a most unmitigated misstatement.”

Aden was reached at last—“The coal hole of the East.” As a health resort, I cannot conscientiously recommend it. The heat was overwhelming, and the local Hotel Ritz sadly wanting in some things and overdone in others. We found it necessary to spend some days there and many sleepless nights, pursuing during the latter the big game in our bedrooms. “Keatings” was of no use. I believe the local insects were case-hardened veterans, and rather liked the powder than otherwise. What nights we had! But every one was in like case, for from all over the house came the sound of slippers banging and much scuffling, and from the room opposite to mine language consigning all insects, the Aden variety in particular, to some even warmer place.

In some ways the hotel was more than up to date. Nothing so ordinary as a mere common or garden bell in one’s room. Instead, a sort of dial, like the face of a clock, with every conceivable want written round it, from a great desire to meet the manager to a wish to call out the local Fire Brigade. You turned on a small steel finger to point at your particular requirement, rang a bell—et voilà! It seems mere carping to state that the matter ended with voilà. The dials were there, you might ring if you liked—what more do you want? Some day some one will answer. Meanwhile, one can always shout.

We met two other shooting parties at our auberge. The first comprised a man and his elderly wife who were not immediately starting, some of their kit having gone astray. He was a noted shot, and Madam had been some minor trip with him and meant to accompany another. She was an intensely cross-grained person, quite the last woman I should yearn to be cooped up in a tent with for long at a time. Cecily’s idea of it was that the shikari husband meant, sooner or later, to put into practice the words of that beautiful song, “Why don’t you take her out and lose her?” and stuck to it that we should one day come on head-lines in the Somaliland Daily Wail reading something like this:

GREAT SHIKARI IN TEARS.

LOOKING FOR THE LOST ONE.

SOME LIONS BOLT THEIR FOOD.=

The good lady regarded us with manifest disapproval. She considered us as two lunatics, bound to meet with disaster and misfortune. Being women alone, we were foredoomed to failure and the most awful things. Our caravan would murder or abandon us. That much was certain. But she would not care to say which. Anyway we should not accomplish anything. She pointed out that a trip of the kind could not by any chance be manoeuvred to a successful issue without the guidance of a husband. A husband is an absolute necessity.

I had to confess, shamefacedly enough, that we had not got a husband, not even one husband, to say nothing of one each, and husbands being so scarce these days, and so hard to come by, we should really have to try and manage without. Having by some means or other contrived to annex a husband for herself, she evinced a true British matron-like contempt for every other woman not so supremely fortunate.

She talked a great deal about “the haven of a good man’s love.” One might sail the seas a long time, I think, before one made such a port. Meanwhile the good lady’s own haven, the elderly shikari, was flirting with the big drum of the celebrated ladies’ orchestra at the Aden tea-house.

“All human beans,” for this is what our friend got the word to, as she was right in the forefront of the g-dropping craze, “should marry. It is too lonely to live by oneself.”

Until one has been married long enough to appreciate the delight and blessedness of solitude this may be true, but wise people don’t dogmatise on so big a subject. Even Socrates told us that whether a man marries or whether he doesn’t he regrets it. And so it would almost follow that if one never jumped the precipice matrimonial one would always have the lurking haunting fear of having been done out of something good. It may be as well, therefore, to take the header in quite youthful days and—get it over. But as the wise Cecily pertinently remarks, you must first catch your hare!

The other shooting party was that of two officers from India, one of them a distant cousin of mine, who was as much surprised to see me as I was to see him. They were setting off to Berbera as soon as humanly possible, like ourselves.

The younger man, my kinsman, took a great fancy to Cecily. At least I suppose he did, in spite of her assertions to the contrary, for he stuck to us like a burr. He was really by way of being a nuisance, as we had a great deal to do in the way of satisfying the excise people, procuring permits and myriad other things.

One evening I heard the two warriors talking and the elder said, not dreaming that his voice would carry so clearly: “Look here, if you are not careful, we shall have those two girls trying to tack on to our show. And I won’t have it, for they’ll be duffers, of course.”

I laughed to myself, even though I was annoyed. Men are conceited ever, but this was too much! To imagine we had gone to all the initial expense and trouble only to join two sportsmen who, true to their masculine nature, would on all occasions take the best of everything and leave us to be contented with any small game we could find!

It is true that being called a girl softened my wrath somewhat. One can’t be called a girl at thirty without feeling a glow of pleasure. I am thirty. So is Cecily.

I expect you are smiling? I know a woman never passes thirty. It is her Rubicon, and she cannot cross it.

My uncle had written ahead for us to Berbera to engage, if possible, his old shikari and head-man, and in addition had sent on copious instructions as to our needs generally. Our trip was supposed to be a secret in Aden, but we were inundated with applications from would-be servants of all kinds. I afterwards discovered that a Somali knows your business almost before you know it yourself, and in this second-sight-like faculty is only exceeded in cleverness by the inhabitants of a little island set in the Irish Sea and sacred to Hall Caine.

All is uneven,

And everything left at six and seven

Richard II

By this time the weekly steamer had sailed to Berbera, across the Gulf, but we arranged to paddle our own canoes, so to speak, and the two sportsmen, still, I suppose, in fear and trembling lest we should clamour to form a part of their caravan, went shares with us in hiring at an altogether ridiculous sum, almost enough to have purchased a ship of our own, a small steamer to transport us and our numerous belongings across the Gulf.

Here I may as well say that it is possible for two women to successfully carry out a big shoot, for we proved it ourselves, but I do not believe it possible for them to do it cheaply. I never felt the entire truth of the well-known axiom, “The woman pays,” so completely as on this trip. The women paid with a vengeance—twice as much as a man would have done.

The getting of our things aboard was a scene of panic I shall never forget. It was, of anything I have ever had to do with, the quaintest and most amusing of sights. Each distinct package seemed to fall to the ground at least twice before it was considered to have earned the right to a passage at all. The men engaged by us to do the transporting of our goods were twins to the porters engaged by our friends, the opposition shoot. They did not appear to reason out that as the mountain of packages had to be got aboard before we could sail, it did not matter whose porter carried which box or kit. No, each porter must stick to the belongings of the individual who hired him to do the job. Naturally, this caused the wildest confusion, and I sat down on a packing case that nobody seemed to care much about and laughed and laughed at the idiocy of it. To see the leader of the opposition shoot gravely detach from my porter a bale of goods to which their label was attached, substituting for it a parcel from our special heap, was to see man at the zenith in the way of management.

It was very early, indeed, when we began operations, but not so early by the time we sailed, accompanied by a rabble of Somalis bent on negotiating the voyage at our expense. It was useless to say they could not come aboard, because come they would, and the villainous-looking skipper seemed to think the more the merrier. Our warrior friends were all for turning off the unpaying guests, but I begged that there should be no more delay, and so, when we were loaded up, like a cheap tripping steamer to Hampton Court, we sailed. It was a truly odious voyage. The wretched little craft rolled and tossed to such an extent I thought she really must founder. I remember devoutly wishing she would.

The leader brought out sketching materials, and proceeded to make a water-colour sketch of the sea.

It was just the same as any other sea, only nastier and more bumpy. We imagined—Cecily and myself—that the boat would do the trip in about sixteen hours. She floundered during twenty-four, and I spent most of the time on a deck-chair, “the world forgetting.” At intervals Somalis would come up from the depths somewhere, cross their hands and pray. I joined them every time in spirit. Cecily told me that the little cabin was too smelly for words, but in an evil minute I consented to be escorted thither for a meal.

“She’s not exactly a Cunarder,” sang out the younger officer, my kinsman, from the bottom of the companion, “but anyway they’ve got us something to eat.”

They had. Half-a-dozen different smells pervaded the horrid little cabin, green cabbage in the ascendant. The place was full of our kit, which seemed to have been fired in anyhow from the fo’castle end. With a silly desire to suppress the evidence of my obvious discomfort, I attacked an overloaded plate of underdone mutton and cabbage. I tried to keep my eyes off it as far as possible; sometimes it seemed multiplied by two, but the greasy gravy had a fatal fascination for me, and at last proved my undoing. The elder warrior supplied a so-called comfort, in the shape of a preventative against sea-sickness, concocted, he said, by his mother, which accelerated matters; and they all kindly dragged me on deck again and left me to myself in my misery. All through the night I stayed on my seat on deck, not daring to face the cabin and that awful smell, which Cecily told me was bilge water.

It was intensely cold, but, fortunately, I had a lot of wraps. The others lent me theirs too, telling me I should come below, as it was going to be “a dirty night,” whatever that might mean. It seemed a never-ending one, and my thankfulness cannot be described when, as the dawn broke, I saw land—Somaliland. We made the coast miles below Berbera, which is really what one might have expected. However, it was a matter of such moment to me that we made it at last that I was not disposed to quibble we had not arrived somewhere else.

I managed to pull myself together sufficiently to see the Golis Range. The others negotiated breakfast. They brought me some tea, made of some of the bilge water I think, and I did not fancy it. Then came Berbera Harbour, with a lighthouse to mark the entrance; next Berbera itself, which was a place I was as intensely glad to be in as I afterwards was to leave it. I should never have believed there were so many flies in the whole world had I not seen them with mine own eyes. In fact, my first impression of Berbera may be summed up in the word “flies.” The town seemed to be in two sections, native and European, the former composed of typical Arab houses and numerous huts of primitive and poverty-stricken appearance. The European quarter has large well-built one-storied houses, flat-roofed; and the harbour looked imposing, and accommodates quite large ships.

Submerged in the shimmering ether we could discern, through the parting of the ways of the Maritime Range, the magnificent Golis, about thirty-five miles inland from Berbera as the crow flies.

The same pandemonium attended our disembarking. All our fellow voyagers seemed to have accompanied the trip for no other reason than to act as porters. There were now more porters than packages, and so the men fought for the mastery to the imminent danger of our goods and chattels. Order was restored by our soldier friends, who at last displayed a little talent for administration; and sorting out the porters into some sort of system, soon had them running away, like loaded-up ants, with our packages and kit to the travellers’ bungalow in the European square, whither we speedily followed them, and established ourselves. It was quite a comfortable auberge, and seemed like heaven after that abominable toy steamer, and we christened it the “Cecil” at once.

Cecily began to sort our things into some degree of sequence. I could not help her. I was all at sea still, and felt every toss of the voyage over. These sort of battles fought o’er again are, to say the least, not pleasant.

We had not arrived so very long before our master of the ceremonies came to discover us, with my uncle’s letter clasped in his brown hand. I shall never forget the amazement on the man’s face as we introduced ourselves. I could not at first make out what on earth could be the matter, but at last the truth dawned on me. He had not expected to find us of the feminine persuasion.

Our would-be henchman’s name was unpronounceable, and sounded more like “Clarence” than anything, so Clarence he remained to the end—a really fine, handsome fellow, not very dark, about the Arab colour, with a mop of dark hair turning slightly grey. His features were of the Arab type, and I should say a strong Arab strain ran in his family, stronger even than in most Somali tribes. I think the Arab tinge exists more or less in every one of them. Anyhow, they are not of negritic descent.

Our man used the Somali “Nabad” as a salutation, instead of the “Salaam aleikum” of the Arabs. The last is the most generally used. We heard it almost invariably in the Ogaden and Marehan countries. Clarence had donned resplendent garb in which to give us greeting, and discarding the ordinary everyday white tobe had dressed himself in the khaili, a tobe dyed in shades of the tricolour, fringed with orange. We never saw him again tricked out like this; evidently the get-up must have been borrowed for the occasion. He wore a tusba, or prayer chaplet, round his neck, and the beads were made from some wood that had a pleasant aroma. A business-like dagger was at the waist; Peace and War were united.

I noticed what long tapering fingers the Somali had, and quite aristocratic hands, though so brown. He had a very graceful way of standing too. In fact all his movements were lithe and lissome, telling us he was a jungle man. I liked him the instant I set eyes on him, and we were friends from the day we met to the day we parted. Had we been unable to secure his services I do not know where we should have ended, or what the trip might have cost. Everyone in Berbera seemed bent on making us pay for things twice over, and three times if possible. Clarence’s demands were reasonable enough, and he fell in with our wishes most graciously.

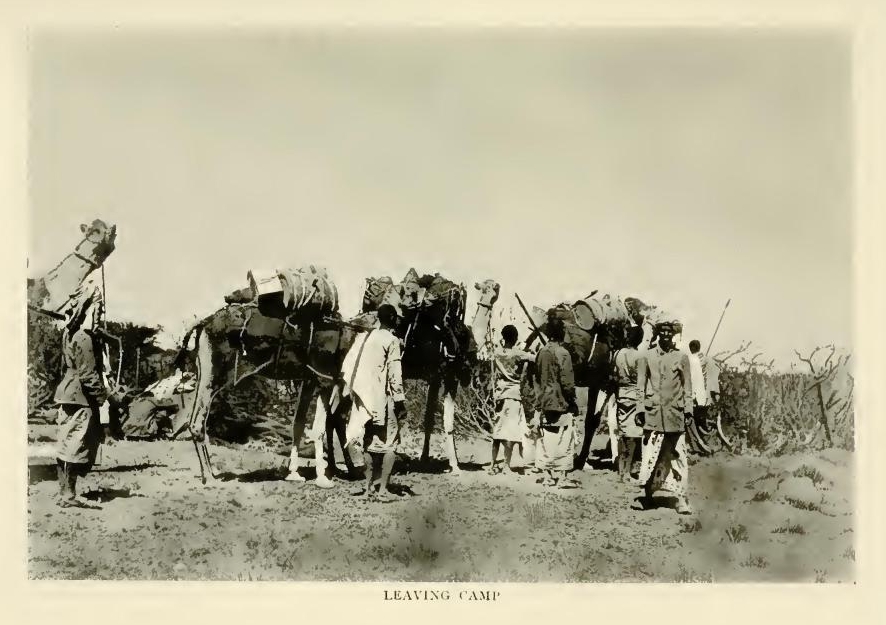

I gave instructions for the purchase of camels, fifty at least, for the caravan was a large one. There were not so many animals in the place for sale at once, and of course our soldier friends were on the look out for likely animals also.

During the next few days we busied ourselves in engaging the necessary servants. My uncle had impressed on me the necessity of seeing that the caravan was peopled with men from many tribes, as friction is better than a sort of trust among themselves. Clarence appeared to have no wish to take his own relatives along, as is so often the case, and we had no bother in the matter. But we were dreadfully ‘had’ over six rough ponies we bought. We gave one hundred and fifty rupees each for them and they were dear at forty. However, much wiser people than Cecily and myself go wrong in buying horses! Later in the trip we acquired a better pony apiece and so pulled through all right.

My cousin has a very excellent appetite, and is rather fond of the flesh-pots generally, and gave as much attention to the engaging of a suitable cook as I did to the purchase of the camels. No lady ever emerged more triumphantly from the local Servants’ Registry Office after securing the latest thing in cooks than did Cecily on rushing out of the bungalow at express speed to tell me she had engaged a regular Monsieur Escoffier to accompany us.

What he could not cook was not worth cooking. Altogether we seemed in for a good time as far as meals were concerned.

Meanwhile Clarence had produced from somewhere about forty-five camels, and I judged it about time to launch a little of the knowledge I was supposed to have gathered from my shikâri uncle. I told Clarence I would personally see and pass every camel we bought for the trip, and prepared for an inspection in the Square. I suffered the most frightful discomfort, in the most appalling heat, but I did not regret it, as I really do think my action prevented our having any amount of useless camels being thrust upon us.

Assume a virtue if you have it not. The pretence at knowledge took in the Somalis, and I went up some miles in their estimation.

As I say, some of the camels offered were palpably useless, and were very antediluvian indeed. I refused any camel with a sore back, or with any tendency that way, and I watched with what looked like the most critical and knowing interest the manner of kneeling. The animal must kneel with fore and hind legs together, or there is something wrong. I can’t tell you what. My uncle merely said, darkly, “something.” Of course I found out age by the teeth, an operation attended with much snapping and Somali cuss-words. The directions about teeth had grown very confused in my mind, and all I stuck to was the pith of the narrative, namely, that a camel at eight years old has molars and canines. I forget the earlier ages with attendant incisors. Then another condition plain to be seen was the hump. Even a tyro like myself could see the immense difference between the round, full hump of a camel in fine condition and that of the poor over-worked creature. As I knew we were paying far too much for the beasts anyway I saw no reason why we should be content to take the lowest for the highest.

Finally I stood possessed of forty-nine camels, try as I would I could not find a fiftieth. I was told this number was amply sufficient to carry our entire outfit, but how they were to do so I really could not conceive. Viewed casually, our possessions now assumed the dimensions of a mountain, and we had to pitch tents in the Square in order to store the goods safely. This necessitated a constant guard.

Everything we brought with us was in apple-pie order owing to the lists so carefully placed in the lid of each box, and gave us no trouble in the dividing up into the usual camel loads. It was our myriad purchases in Berbera that caused the chaos. They were here, there and everywhere, and all concerning them was at six and seven. I detailed some camels to carry our personal kit, food supplies, &c., exclusively; the same men to be always responsible for their safety, and that there should be no mistake about it I took down the branding marks on apiece of paper. Camels seem to be branded on the neck, and most of the marks are different, for I suppose every tribe has its own hallmark.

Some of the camels brought into Berbera for sale are not intended to be draught animals, being merely for food, and with so much care and extra attention get very fine and well-developed generally. Camel-meat is to the Somali what we are given to understand turtle soup is to the London alderman. Next in favour comes mutton, but no flesh comes up to camel. The Somali camel-man is exceedingly attentive to his charges, giving them names, and rarely, if ever, ill treating them. As a result the animals are fairly even tempered, for camels, and one may go amongst them with more or less assurance of emerging unbitten. When loading up the man sings away, and the camel must get familiar with the song. It seems to be interminably the same, and goes on and on in dreary monotone until the job is over. I would I knew what it was all about.

Of course it is a fact that a camel can take in a month’s supply of water, but it very much depends on the nature of the month how the animal gets on. If he is on pasture, green and succulent, he can go on much longer than a month, but if working hard, continuously, and much loaded, once a week is none too often to water him. They are not strong animals; far from it, and they have a great many complaints and annoyances to contend with in a strenuous life. The most awful, to my mind, is sore back and its consequences. This trouble comes from bad and uneven lading, damp mats, &c., and more often than not the sore is scratched until it gets into a shocking condition. Flies come next, and maggots follow, and then a ghastly Nemesis in the form of the rhinoceros bird which comes for a meal, and with its sharp pointed beak picks up maggots and flesh together. When out at pasture these birds never leave the browsing camels alone, clinging on to shoulders, haunch, and side, in threes and fours.

We had now in our caravan, not counting Clarence and the cook, two boys (men of at least forty, who always referred to themselves as “boys”) to assist the cook, one “makadam,” or head camel-man, twenty-four camel men, four syces, and six hunters, to say nothing of a couple of men of all work, who appeared to be going with us for reasons only known to themselves.

In most caravans the head-man and head shikari are separate individuals, but in our show Clarence was to double the parts. It seemed to us the wisest arrangement. He was so excellent a manager, and we knew him to be a mighty hunter.

The chaos of purchases included rice, harns or native water-casks, ordinary water barrels calculated to hold about twelve gallons apiece, blankets for the men, herios, or camel mats, potatoes, ghee, leather loading ropes, numerous native axes, onions, many white tobes for gifts up country, and some Merikani tobes (American made cloth) also for presents, or exchange. Tent-pegs, cooking utensils, and crowds of little things which added to the confusion. A big day’s work, however, set things right, and meanwhile Cecily had discovered a treasure in the way of a butler. He had lived in the service of a white family at Aden, and so would know our ways.

We had taken out a saddle apiece, as the double-peaked affair used by the Somalis is a very uncomfortable thing indeed.

Rice for the men’s rations we bought in sacks of some 160 pounds, and two bags could be carried by one camel. Dates, also an indispensable article of diet, are put up in native baskets of sorts, and bought by the gosra, about 130 pounds, and two gosra can be apportioned to a camel. Ghee, the native butter, is a compound of cow’s milk, largely used by the Somalis to mix with the rice portion, a large quantity of fat being needful ere the wheels go round smoothly. It is bought in a bag made of a whole goat skin, with an ingenious cork of wood and clay. Each bag, if my memory serves me rightly, holds somewhere about 20 pounds, and every man expects two ounces daily unless he is on a meat diet, when it is possible to economise the rice and dates and ghee.

The camel mats, or herios, are plaited by the women of Somaliland, and are made from the chewed bark of a tree called Galol. The harns for water are also made from plaited bark, in different sizes, and when near a karia, it is quite usual to see old women and small children carrying on their backs the heaviest filled harns, whilst the men sit about and watch operations. The harns, which hold about six gallons of water, are—from the camels’ point of view anyway—the best for transport purposes. Six can be carried at once, but a tremendous amount of leakage goes on, and this is very irritating, upsetting calculations so. The water-casks were really better, because they were padlocked, and could also be cleaned out at intervals. But of these only two can go on a camel at one time.

Our own kit was mostly in tin uniform cases, these being better than wooden boxes on account of damp and rainy weather. Leather, besides being heavy, is so attractive to ants. Our rifles, in flat cases, specially made, were compact and not cumbersome, at least not untowardly cumbersome. Our food stores were in the usual cases, padlocked, and a little of everything was in each box, so that we did not need to raid another before the last opened was half emptied. The ammunition was carried in specially made haversacks, each haversack being marked for its particular rifle, and more spare ammunition was packed away in a convenient box, along with cleaning materials, &c. We made our coats into small pantechnicons, and the pockets held no end of useful small articles and useful contraptions. My two coats, one warm khaki serge, one thin drill, were both made with recoil pads as fixtures, and this was an excellent idea, as they saved my shoulder many hard knocks.

We heard of a man who was anxious to go out as skinner, but the Opposition, for we had by now christened the rival camp so, snapped him up before we had an opportunity to engage him. On learning of our disappointment they nobly volunteered to waive their claim, but when I saw the trophy in discussion I would not take him into our little lot at any price. A more crafty, murderous-looking individual it would be hard to find.

The Opposition watched us do some of the packing, and were green with envy as they handled our rifles. The elder tried to induce me to sell him my double-barrelled hammerless ejecting .500 Express. I don’t know how I was meant to be able to get along without it, but I suppose he didn’t think that mattered.

It was then that Clarence, who had, I believe, been yearning to ask all along, wanted to know if I was any good with a rifle, and the other Mem-sahib could she shoot, and if so how had we learned, for the Somalis are nothing if not direct. They rather remind me of English North-country people with their outspoken inquisitiveness, which is at home always regarded as such charming straightforwardness of character.

I was as modest as I could be under the circumstances, but I had to allay any fears the man might be harbouring. Besides, it is not well to under-estimate oneself, especially to a Somali. Nowadays everywhere it is the thing to remove the bushel from one’s light and to make it glare in all men’s eyes. My advice to any one who wants to be heard of is—Advertise, advertise, advertise. If you begin by having a great opinion of yourself and talk about it long enough, you generally end by being great in the opinion of everyone else. I told our shikari I had the use of my uncle’s fine range at home, and the advantage of what sport there was to be had in England and Scotland. Also that this was not our first expedition. The knowledge of all this and my unbounded confidence, not to say cheek, set all doubts at rest.

Every night I was rendered desperate by the scratching in my room of some little rodent which thundered about the floor as though his feet were shod with iron.

Hurrah! At last I had him! He stole my biscuits set for my “chota hazari,” and sometimes left me stranded. They resided in a tin by my bedside. Kismet overtook him, and his nose was in the jaws of a gin. He was killed instanter, and the cat dropped in to breakfast.

I helped her to him.

She commenced on his head, and finished with his tail, a sort of cheese straw. This is curious, because a lion, which is also a cat, begins at the other end. Domesticity reverses the order of a good many things.

He left no trace behind him. Unknown (except to me) he lived, and uncoffined (unless a cat may be called a coffin) he died. By the way, he was a rat.

One afternoon Cecily and I walked along the sea coast at Berbera, and came on the most remarkable fish, jumping into the sea from the sandy shore. I asked a resident about this, and he said the fish is called “mud-skipper”—a name that seems to have more point about it than most.

So, at last, we reached the day fixed for the starting of the great trek.

My necessaries are embark’d

Hamlet

Occasion smiles upon a second leave

Hamlet

At three o’clock in the morning we joined our caravan, all in readiness, in the Square. It was still dark, but we could see the outline of the waiting camels loaded up like pantechnicon vans, and our ponies saddled in expectation of our coming. The Opposition, who had mapped out a different route, beginning by skirting the borders of the now barred reserve for game in the Hargaisa, got up to see us start and wish us “Good hunting.” What our men thought of us and the expedition generally I cannot conjecture. Outwardly at least they gave no sign of astonishment. Clarence gave the word to march, and we set out, leaving Berbera behind us, and very glad we were to see the suburbs a thing of the past. The flies and the sand storms there are most hard to bear, and a little longer sojourn would have seen both of us in bad tempers.

We made up our minds from the first to have tents pitched every night under any circumstances, and never do any of that sleeping on the ground business which seems to be an indispensable part of the fun of big game shooting. We also resolved to share a tent for safety’s sake, but after a little, when we had begun to understand there was nothing on earth to be afraid of, we “chucked” this uncomfortable plan and sported a tent apiece.

On clear nights I always left the flap of the tent open.

I loved to see the wonderful blue of the sky, so reminiscent of the chromo-lithograph pictures admired so greatly in childhood’s days. And I would try and count the myriad stars, and trace a path down the Milky Way. How glorious it was, that first waking in the early, early morning with dark shadows lurking around, the embers of the fires glowing dully, and—just here—a faint breeze blowing in with messages from the distant sea.

The long string of grunting camels ahead looked like some pantomime snake of colossal proportions as it wriggled its way through the low thorn bushes which, here and there, grew stunted and forlorn; camels move with such an undulating gait, and the loads I had trembled about seemed to be a mere bagatelle.

All too soon came the day, and, with the day, the sun in fiery splendour, which speedily reduced us both to the condition of Mr. Mantalini’s expressive description of “demn’d, damp, unpleasant bodies.” The glitter from the sand made us blink at first, but, like everything else, we got perfectly inured to it, and dark days or wet seemed the darker for its loss.

Jerk! And all the camels stopped and bumped into each other, like a train of loaded trucks after a push from an engine. The front camel decided he would rest and meditate awhile, so sat down. He had to be taught the error of such ways, and in a volley of furious undertones from his driver be persuaded to rise.

We passed numerous camels grazing, or trying to, in charge of poor looking, half-fed Somali youths. There is no grazing very near into Berbera, very little outside either unless the animals are taken far afield. Here they were simply spending their energy on trying to pick a bit from an attenuated burnt-up patch of grass that would have been starvation to the average rabbit.

The camel men in charge came over to exchange salaams with ours, and proffer camels’ milk, in the filthiest of harns, to the “sahibs.” We couldn’t help laughing. But for our hair we looked undersized sahibs all right, I suppose, but we couldn’t face the milk. It would have been almost as disagreeable as that bilge water tea.

We each rode one of our expensive steeds, and I had certainly never ridden worse. I called mine “Sceptre,” and “Sceptre” would not answer to the rein at all. I think his jaw was paralysed. He would play follow the leader, so I rode behind Cecily.

The cook of cooks made us some tea, but I don’t think the kettle had boiled. Cecily said perhaps it wasn’t meant to in Somaliland. I asked her to see that we set the fashion.

We rested during the hottest hours, and then trekked again for a little in the evening. There was no need to form a thorn zareba the first night out, as we were practically still in Berbera—at least I felt so when I knew we had covered but some fifteen miles since dawn. Perhaps it will be as well here to describe our clothes for the trip. We wore useful khaki jackets, with many capacious pockets, knickerbockers, gaiters, and good shooting boots. At first we elected to don a silly little skirt that came to the knee, rather like the ones you see on bathing suits, but we soon left the things off, or rather they left us, torn to pieces by the thorns.

Mosquitoes do not like me at all in any country, but we had curtains of course, and they served, very badly, to keep out the insects that swarmed all over one.

Next day as we progressed, we saw numerous dik-dik, popping up as suddenly as the gophers do in Canada. They are the tiniest little things, weighing only about four pounds, and are the smallest variety of buck known. The back is much arched, grey brown in colour, with much rufous red on the side. The muzzle is singularly pointed. The little horns measure usually about two and a half inches, but the females are hornless.

The ground we went over was very barren and sandy, rather ugly than otherwise, and there was no cover of any kind. Any thought of stalking the small numbers of gazelle we saw was out of the question. Besides, our main object was to push on as fast as possible to the back of beyond.

In the evenings we always did a few miles, and camped where any wells were to be found. The water was full of leeches, but we carefully boiled all the drinking water for our personal use. The Somalis seem to thrive on the filthiest liquid.

The cook got a leech of the most tenacious principles on to his wrist, and made the most consummate fuss. A bite from a venomous snake could hardly have occasioned more commotion. I can’t imagine what the condition of the man would have been had the leech stayed as long as it intended. I put a little salt on its tail, and settled the matter. By the end of the next short trek we reached the Golis Range, taking them at their narrowest part. The whole place had changed for the better. Clear pools of water glistened bright among a riot of aloes and thorns, and there was also a very feathery looking plant, of which I do not know the name.

For the first time we said to each other, “Let us go out and kill something, or try to.” There was always the dread of returning to camp unblooded, so to speak, when Clarence might, or would, or should, or could regard us as two amiable lunatics not fit to be trusted with firearms. This is a woman all over. Try as she will she cannot rise superior to Public Opinion—even the opinion of a crowd of ignorant Somalis! After all, what is it? “The views of the incapable Many as opposed to the discerning Few.”

We agreed to separate, tossing up for the privilege of taking Clarence. To my infinite regret I drew him. As a rule when we tossed up we did it again and again until the one who had a preference got what she wanted. Women always toss up like that. Why bother to toss at all? Ah, now you’ve asked a poser.

But I couldn’t get Cecily to try our luck again. She said she was suited all right. The fact being that neither of us yearned to make a possible exhibition before our shikari. There was nothing for it. I took my .500 Express, and with Clarence behind me flung myself into the wilderness in as nonchalant a manner as I could assume. I was really very excited in a quiet sort of way, “for now sits Expectation in the air.” It got a trifle dashed after an hour of creeping about with no sort of reward save the frightened rush of the ubiquitous dik-dik.

“Mem-sahib! Mem-sahib!” from the shikari, in excited undertone.

He gripped my arm in silent indication.

“Mem-sahib!” in tones of anguished reproach. “Gerenük!”

We were always Mems to Clarence, who perhaps felt, like the lady at Aden, that if we weren’t we ought to be.

I looked straight ahead, and from my crouching position could make out nothing alive. I gazed intently again. And, yes, of course, all that I looked at was gerenük, two, three, four of them. In that moment of huge surprise I couldn’t even count properly. The intervening bushes screened them more or less, but what a comical appearance they had! how quaintly set their heads! how long their necks! how like giraffes! They moved on, slowly tearing down the thorns as they fed. I commenced to stalk. There was a fine buck with a good head. It was not difficult to distinguish him, as his harem carried no horns.

For twenty minutes or more I crawled along, hoping on, hoping ever, that some chance bit of luck would bring me in fairly clear range, or that the antelope would pause again. Clearly they had not winded me; clearly I was not doing so very badly to be still in their vicinity at all. Now came a bare patch of country to be got over, and I signed to Clarence to remain behind. I was flat on my face, wriggling along the sand. If the antelope were only in the open, and I in the spot where they were screened! The smallest movement now, and... I got to within 120 yards of them when something snapped. The herd gathered together and silently trotted off, making a way through the density with surprising ease considering its thick nature. I got up and ran some way to try and cut them off, dropping again instantly as I saw a gap ahead through which it seemed likely their rush would carry them. It was an uncertain and somewhat long shot, but the chances were I should never see the animals again if I did not take even the small opportunity that seemed about to present itself. I had long ago forgotten the very existence of my shikari. The world might have been empty save for myself and four gerenük. Nervousness had left me, doubts of all kinds; nothing remained save the wonder and the interest and the scheming.

It really was more good luck than good management. I afterwards discovered that the gerenük, or Waller’s gazelle, is the most difficult antelope to shoot in all Somaliland, mostly from their habit of frequenting the thickest country.

This is where the ignoramus scores. It is well known that the tyro at first is often more successful in his stalks, and kills too, for the matter of that, than your experienced shikari with years of practice and a mine of knowledge to draw on. Fools rush in where angels fear to tread—and win too sometimes.

The herd passed the gap, and, as they did so, slowed up a bit to crush through. The buck presented more than a sporting shot, his lighter side showing up clear against his dark red back. I fired. I heard the “phut” of the bullet, and knew I had not missed. I began to tremble with the after excitements, and rated myself soundly for it. I dashed to the gap. The buck—oh, where was he? Gone on, following his companions, and all were out of sight. He was seriously wounded, there was no doubt, for the blood trail was plain to be seen. Clarence joined me, and off we went hot on the track. After a long chase we came on a thickish bunch of thorns, and my quarry, obviously hard hit, bounded out, and was off again like the wind before I had an opportunity to bring up my rifle. It was a long time before he gave me another, when, catching him in fairly open ground, I dropped him with a successful shot at some 140 yards, and the buck fell as my first prize of the trip.

Clarence’s pleasure in my success was really genuine, and I gave him directions to reserve the head and skin, royally presenting him with all the meat. I could not at first make out why he so vigorously refused it. I made up my mind he had some prejudice against this particular variety of antelope. I afterwards found that no Jew is more particular how his meat is killed than is the Somali. The system of “hallal” is very strictly respected, and it was only occasionally, when I meant the men to have meat, that I was able to stock their larder.

I tasted some of this gerenük, and cooked it myself, Our cook was, indeed, a failure. He was one of the talk-about-himself variety, and from constant assertions that he could cook anything passing well, had come to believe himself a culinary artist.

I roasted a part of the leg of my gerenük, and did it in a way we used to adopt in the wilds of Vancouver Island. A hole is made in the ground and filled with small timber and pieces of wood. This is fired, and then, when the embers are glowing, the meat being ready in a deep tin with a tight-fitting lid, you place it on the hot red ashes, and cover the whole with more burning faggots, which are piled on until the meat is considered to be ready. If the Somalis have a quantity of meat to cook, they make a large trench, fill it with firewood, and make a network of stout faggots, on which the meat is placed. It is a sort of grilling process, and very effective. If kept constantly turned, the result is usually quite appetising.

Cecily came into camp with a Speke buck. I examined it with the greatest interest. The coat feels very soft to the touch, and has almost the appearance of having been oiled. Speke’s Gazelle are very numerous in the Golis, and are dark in colour, with a tiny black tail. They have a very strange protuberance of skin on the nose, of which I have never discovered the use. Every extraordinary feature of wild life seems to me to be there for some reason of protection, or escape, or well being. Dear Nature arranges things so to balance accounts a little ’twixt all the jungle folk. In the Speke fraternity there is more equality of the sexes. The does as well as the bucks carry horns. At first I pretended to Cecily that my expedition had been an humiliating and embarrassing failure, that I had signally missed a shot at a gerenük that would have delighted the heart of a baby in arms. But she caught sight of my trophy impaled on a thorn bush, and dashed over to see it instanter.

About this time we were very much amused to discover we had among our shikaris a veritable Baron Munchausen. Of whatever he told us, the contrary was the fact. If he brought news of splendid “khubbah,” there was no game for miles. If we went spooring, he spoored to the extent of romancing about beasts that could not possibly frequent the region we were in at all. I do not mind a few fibs; in fact, I rather like them.

“A taste exact for faultless fact

Amounts to a disease,”

and argues such a hopeless want of imagination. But this man was too much altogether. Of course he may have had a somewhat perverted sense of humour.

My uncle had warned me I should find all Somalis frightful liars, and to be prepared for it. Personally, I always like to assume that every man is a Washington until I have proved him to be an Ananias.

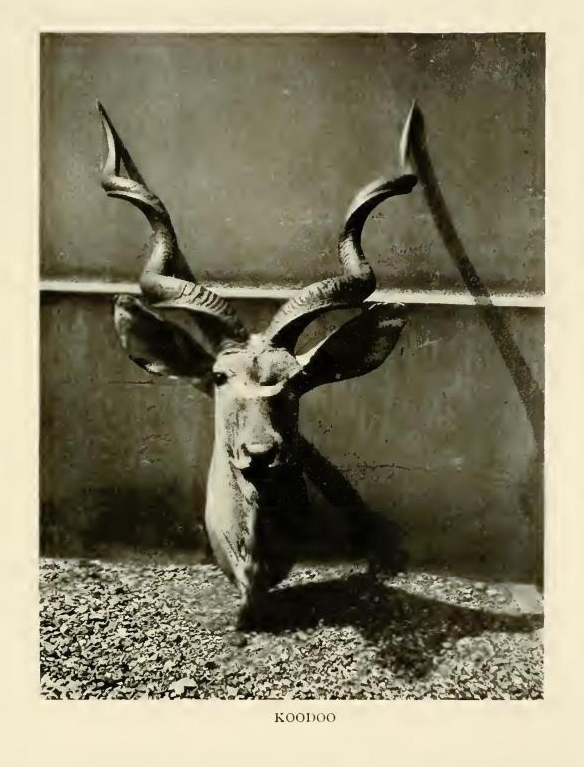

We saw—in the distance—numerous aoul, Soemmering’s Gazelle, and the exquisitely graceful koodoo, the most beautiful animal, to my thinking, that lives in Somaliland. The horns are magnificent, with the most artistic of curves. The females are hornless in this species also. When come upon suddenly, or when frightened, this animal “barks” exactly as our own red deer are wont to do. In colour they are of a greyish hue, and their sides are striped in lines of white.

It was not our intention to stay and stalk the quantities of game about us. Our desire was all to push on to the kingdom of His Majesty King Leo. So for days we went on, halting o’ nights now in glorious scenery, and everywhere the game tracks were plentiful. The other side of the Golis we thought really lovely, the trees were so lofty and the jungle so thick. The atmosphere was much damper, and it was not long before we felt the difference in our tents. However, there was one consolation, water was plentiful, and we were so soon to leave that most necessary of all things.

The birds were beautiful, and as tame as the sparrows in Kensington Gardens. One afternoon I walked into a small nullah, where, to my joy, I found some ferns, on which some of the most lovely weaver-finches had built their nests. The small birds are, to my mind, the sweetest in the world. Some were crimson, some were golden, and the metallic lustre of their plumage made them glitter in the sun. There was also a variety of the long-tailed whydah bird, some honey-suckers, and a number of exquisite purple martins. Two of the last flew just behind me, snapping up the insects I stirred up with my feet. I watched one with a fly in its beak, which it released again and again, always swooping after it and recapturing it, just like a cruel otter with its fish.

I tried to find some of the nests of the little sun-birds. I believe they dome them, but no one quite knows why. It was once thought that it was done to hide the brilliant colours of some feminines from birds of prey, but it is done by some plain ones as well. Some birds lock up their wives in the nests; they must be a frivolous species!

Many of the honey-suckers are quite gorgeous when looked at closely—especially the green malachite ones, which have a bright metallic appearance. I also watched some little russet finches performing those evolutions associated with the nesting season only. They rose clapping their wings together above them, producing a noise somewhat similar to our own hands being clapped, and when at the top of their ascent they uttered a single note and then shut up as if shot, descending rapidly until close to the ground, when they open their wings again and alight most gently. The single note is the love song, and the other extraordinary performance is the love dance. It must be attractive, as it is done by the male only, and only in the breeding season.

Farther on I got into a perfect little covey of sun-birds flying about and enjoying themselves. Every now and again one would settle on a flowering shrub with crimson blossoms, and dip its curved long beak into the cup and suck out the honey. The male of this species is ornamented with a long tail, the female being much plainer. In the brute creation it is always so; the male tries to captivate by ornaments and brilliant colours. We human beings have grown out of that and try other blandishments. But it is curious that the male has still to ask and the female to accept. We haven’t changed that. We fight just as bucks and tigers do, and the winner isn’t always chosen; there may be reasons against it. There is just that little uncertainty, that little hardness to please which gives such joy to the pursuit. Well, there are exceptions, for the ladies of the bustard persuasion fight for their lords.

On my way back to camp I saw a buck and Mrs. Buck of the Speke genus. The former stood broadside on, and almost stared me out of countenance at fifty paces. He evidently knew I was unarmed. Why do they always stand broadside on? I’ve never seen it explained. I suppose it is partly because he is in a better position for flight.

At this camp we were caught in a continuous downpour which lasted twenty-four hours, intermixed with furious thunderstorms. Cecily’s tent (fortunately she was in mine at the time) was struck, producing some curious results. The lightning split the bamboo tent-pole into shreds and threw splinters about that, when collected, made quite a big bundle. The hats and clothes which were hanging on to the pole were found flung in all directions, but nothing was burnt. The lightning disappeared into the loose soil, without appreciably disturbing it.

Then we had a glorious day sandwiched in, but returned again to the winter of our discontent and Atlantic thunderstorms. It was rather unfortunate to emerge from one rain to enter another. We took the precaution this time to entrench ourselves so that the tents were not flooded, but the poor camels must have had a bad time.

The sun reappeared at last, after a long seclusion, and all our clothes, beds, and chattels had to be dried. Never has old Sol had a warmer welcome. All nature aired itself.

We moved on and now found it needful to form a zareba at night. Into this citadel of thorns and cut bushes the camels were driven and our tents set up. At intervals of a few yards fires blazed, and a steady watch was kept.

We camped in one place for two days in order to fill up every water cask, and here Cecily and I, going out together one morning quite early, had the luck to come on a whole sounder of wart hog. I shall never forget the weird and extraordinary spectacle they presented. A big boar, rather to the front, with gleaming tushes, stepping so proudly and ever and again shaking his weighty head. They all appeared to move with clockwork precision and to move slowly, whereas, as a matter of fact, they were going at a good pace. We dropped, and I took a shot at the coveted prize, and missed! The whole sounder fled in panic, with tails held erect, a very comical sight. We doubled after them through the bush, and bang! I had another try. They were gone, and the whole jungle astir.

I bagged a very fine Speke’s Gazelle here, but am ashamed to say it was a doe. It is very hard sometimes to differentiate between the sexes in this species.

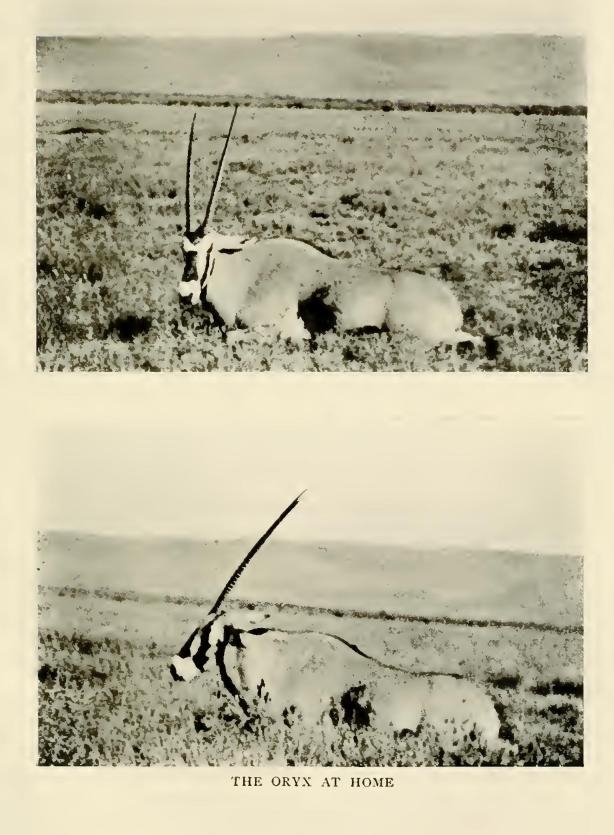

I was very much looking forward to the opportunity of bagging an oryx, I admire the horns of this antelope so greatly, though I suppose they are not really to be compared in the same breath with those of the koodoo. The oryx is very powerfully made, about the size of a pony, and the horns are long and tapering. They remind me of a vast pair of screws, the “thread” starting from the base and winding round to a few inches off the top when the horn is plain. They are the greatest fighters of all the genus buck, and the bulls are provided by nature, who orders all things well, with almost impenetrable protective horn-proof shields of immensely thick skin which covers the withers. These are much valued by the Somalis for many purposes, notably for the shields carried by them when in full dress. Set up as trophies they take a high polish and come up like tortoise-shell. One or two of mine I had mounted as trays, with protective glass, others as tables. All were exceedingly effective.

By this time we had got to and set out upon, not without some qualms, the waterless Haud, starting for the first march at cock-crow. In some parts it attains a width of over two hundred miles across. It all depends on where you strike it. We did the crossing in ten marches, taking five days over it. All that time we had to rely solely on the supply of water we carried with us, which was an anxious piece of work. I do not think we ever did so little washing in our lives before; water was too precious to juggle with then.

Haud is a Somali word signifying the kind of country so named, and may mean jungly ground or prairie-like plains. We crossed a part which reminded us both of the Canadian prairies, dried-up grass as far as the eye could reach. The waterless tract most crossed by travellers and trading caravans is arid and barren, and the paths are not discernible owing to the springy nature of the ground. Parts of the Haud are quite luxuriant, and provide grazing for countless thousands of camels, sheep, and goats. Our route lay over a flat, ugly, and uninteresting expanse. It was no use looking for signs of game. The new grass had not as yet appeared. Even the easily contented camels had to make believe a lot at meal-times.

We were marvellously lucky in our getting over this daunting place. At no time were we overwhelmed with the heat. A quite refreshing breeze blew over us most days, and at night we found it too cold to be pleasant. I called it luck, but Clarence attributed it to the will of Allah.

I got a fine bustard for the pot. A beautiful bird with a dark brown crest, and a coat, like Joseph’s, of many colours. I saved some of the feathers, they were so iridescent and beautiful. The bustard tribe in Somaliland appears to be a large one. I noticed three or four distinctly different species, with dissimilar markings. The Ogaden bustard had the prize, I think, in glory of plumage. Even his beak was painted green, his legs yellow, and all else of him shone resplendent. The cook made a bustard stew, and very good it tasted. We did not need to feel selfish, feasting so royally, for birds are not looked on with any favour by Somalis, though they do not refuse to eat them. I think it is because no bird, even an ostrich, can grow big enough to make the meal seem really worth while to a people who, though willing enough to go on short commons if occasion forces, enjoy nothing less than a leg of mutton per man.

Cecily, lucky person, shot a wart-hog, coming on him just as he was backing in to the little pied-à-terre they make for themselves. She did deserve her luck, for as I was out, and not able to help her, she had to dissect her prize alone. Pig is unclean to the Somali. Even the cook, who claimed to be “all same English,” was not English enough for this. We kept the tushes, and ate the rest. The meat was the most palatable of any we had tasted so far.

I bagged a wandering aoul, not at all a sporting shot. I got the buck in the near fore, and but for its terrible lameness I should never have come up with it at all. His wound, like Mercutio’s, sufficed. One might as well try to win the Derby on a cab-horse as come up with even a wounded buck on any of the steeds we possessed. I ambled along, and so slowly that the buck was outstripping the pony. I slipped off then, and running speedily, came within excellent range and put the poor thing out of his pain. His head was the finest of his kind we obtained.

The horns differ considerably, and I have in my collection backward and outward turning ones. Aoul is a very common gazelle in all parts of open country, barring South-East Somaliland, and travels about in vast herds. Its extraordinary inquisitiveness makes it fall a very easy victim.

Clarence went out with us in turn. His alternative was a fine upstanding fellow, but after three or four expeditions with him as guide I deposed him from the position of second hunter. He was slow, and lost his presence of mind on the smallest provocation, both of them fatal defects in a big game hunter, where quickness of brain and readiness of resource is a sine qua non.

My hour is almost come

Hamlet

A lion among ladies is a most dreadful thing, for there is not

a more fearful wild fowl than your lion living

Midsummer Night’s Dream

Very shortly after this we came to a Somali karia, or encampment. Its inhabitants were a nomadic crowd, and very friendly, rather too much so, and I had to order Clarence to set a guard over all our things.

Their own tents were poor, made of camel mats that had seen better days. The Somali women were immensely taken with our fair hair, and still more with our hair-pins. Contrary to the accepted custom of lady travellers, we did not suffer the discomfort of wearing our hair in a plait down our backs. We “did” our hair—mysterious rite—as usual. By the time I had finished my call at the camp my golden hair was hanging down my back. I had given every single hair-pin to the Somali ladies, who received them with as much delight as we should a diamond tiara.