WORKS OF ISRAEL ZANGWILL

ESSAYS:

- CHOSEN PEOPLES

- THE PRINCIPLE OF NATIONALITIES

- ITALIAN FANTASIES

- WITHOUT PREJUDICE

- THE WAR FOR THE WORLD

- THE VOICE OF JERUSALEM

NOVELS:

- CHILDREN OF THE GHETTO

- DREAMERS OF THE GHETTO

- GHETTO TRAGEDIES

- GHETTO COMEDIES

- THE CELIBATES’ CLUB

- THE GREY WIG: Stories and Novelettes

- THE KING OF SCHNORRERS

- THE MANTLE OF ELIJAH

- THE MASTER

- THE PREMIER AND THE PAINTER (with Louis Cowen)

- JINNY THE CARRIER

PLAYS:

- THE MELTING POT: A Drama in Four Acts

- THE NEXT RELIGION: A Play in Three Acts

- PLASTER SAINTS: A High Comedy in Three Movements

- THE WAR GOD: A Tragedy in Five Acts

- THE COCKPIT: Romantic Drama in Three Acts

- THE FORCING HOUSE: Tragi-Comedy in Four Acts

POEMS:

- BLIND CHILDREN

UNIFORM WITH THIS VOLUME

Cloth 2/- net. Paper 1/- net.

The Arthur Davis Memorial Lectures:

CHOSEN PEOPLES

By ISRAEL ZANGWILL

Second Impression

With a Foreword by the Rt. Hon. Sir Herbert Samuel, M.A., High Commissioner of Palestine

WHAT THE WORLD OWES TO THE PHARISEES

By the Rev. R. TRAVERS HERFORD, B.A.

With a Foreword by General Sir John Monash, G.C.M.G., K.C.B., D.C.L.

POETRY AND RELIGION

By ISRAEL ABRAHAMS, M.A., D.D.

Reader in Rabbinic at the University of Cambridge

With a Foreword by Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch, M.A., D.Litt.

SPINOZA AND TIME

By S. ALEXANDER, M.A., LL.D., F.B.A.

Hon. Fellow of Lincoln College, Oxford; Professor of Philosophy in the University of Manchester

With an Afterword by Viscount Haldane, O.M., F.R.S.

THE STATUS OF THE JEWS IN EGYPT

-

- April 30, 1922

- Iyar 2, 5682

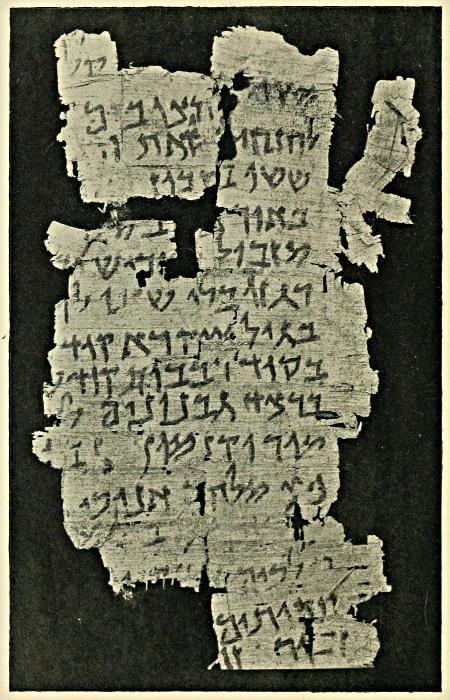

FRAGMENT OF AN ANCIENT HEBREW PAPYRUS—THE OLDEST IN THE WORLD—DISCOVERED BY PROFESSOR FLINDERS PETRIE.

For translation see Appendix.

THE STATUS OF

THE JEWS IN EGYPT

BY

W. M. FLINDERS PETRIE

D.C.L., LL.D., F.R.S., F.B.A.

Edwards Professor of Egyptology, University College

WITH A FOREWORD BY

Sir PHILIP SASSOON, Bart., M.P.

LONDON: GEORGE ALLEN & UNWIN LTD.

RUSKIN HOUSE, 40 MUSEUM STREET, W.C.1

All rights reserved

First published in 1922

NOTE

The Arthur Davis Memorial Lecture was founded in 1917, under the auspices of the Jewish Historical Society of England, by his collaborators in the translation of “The Service of the Synagogue,” with the object of fostering Hebraic thought and learning in honour of an unworldly scholar. The Lecture is to be given annually in the anniversary week of his death, and the lectureship is to be open to men or women of any race or creed, who are to have absolute liberty in the treatment of their subject.

FOREWORD

By Sir Philip Sassoon, Bart., M.P.

I thank the Society for the honour they have done me in asking me to preside upon so interesting an occasion. Professor Petrie needs no introduction; and I can but express the gratitude of the meeting to him for coming to lecture on an absorbing topic. We should have to go very far to find a more eminent Egyptologist. He is not limited to a discussion and criticism of other men’s discoveries; he is a most successful excavator himself. He has with his own hands unearthed many objects of the deepest interest to all students of the remote Egyptian past. He has been engaged in this work for forty years, during thirty of which he has occupied the distinguished position of Professor of Egyptology at this University, where he has spoken with peculiar authority on the significance of his own and other men’s discoveries, and has interpreted them to laymen such as myself. The late Arthur Davis, in whose memory[12] these lectures are held, was a type of that rare and valuable man who, while engaged in business, is yet inspired by a studious ambition. He was a man above the average, who taught the lesson to the average man of affairs that the delights of learning are open to all those who are able to make use of the opportunities they can find and create. Such men are an honour to any cultured community.

The Status of the Jews in Egypt

In considering the history of any people, one of the main elements is that of their status. What were their abilities and how were they shown? What permanent mark did they make on their period? How did they stand in reference to their neighbours, in the same country and in other countries? There are now Jews in Lemberg and Jews in Paris; but how entirely differently we regard them, because of their status. How utterly diverse is the mark left on the world by the men of mind, by Isaiah or Aristotle, compared with the energies of patriots, like the Maccabees or Sulla. Mere existence matters nothing to the present or the future; it is the energizing influence of fresh thoughts or organization that alone gives value to any people. Various races at present who think a great deal of themselves have never added a single idea[14] or capability to the rest of the world, their status is simply that of incapable dependence upon the civilization of others. Regarding then the dominant importance of status, it seemed that it would be useful to focus together the various fragments of views that have been gained as to the position occupied by the Jewish race in Egypt at different periods.

We may glance first at the earlier relations of Semites with Egypt. The second prehistoric civilization was of Eastern origin; and judging by the strong analogies of the Egyptian language with Semitic speech, it seems probable that this prehistoric age was dominated by a race which later developed into the historic Semites.

Coming into recorded history, we can now realize, from recent discoveries, how the VIIth and VIIIth Egyptian dynasties which overthrew the earlier pyramid builders were Syrian kings ruling over Egypt. Their personal names are preserved in some reigns on the great list of kings at Abydos,[1] and their status is recorded by a cylinder of one of these kings[2]—Khondy—bearing a figure of a flounced Syrian before him, and an Egyptian in the background. The king himself has his name in a cartouche and wears the crown of Upper[15] Egypt; so he did not rule only over the Delta, and his name being at Abydos points to control of the whole country. As to the language, the names of these kings appear to be Semitic, as Telulu the exalted, Shema the high, Neby the prophet. All of this accords closely with the recent publications of Professor Albert Clay[3] on the importance of a north Syrian kingdom, as the real centre of the Semitic peoples, rather than Arabia, which he regards as a backwater, where an early type has remained undisturbed. His appeal to the Semitic names in early Babylonia shows that they are quite as early as—or earlier than—the Sumerian.

This Semitic conquest of Egypt had a close parallel in the Hyksos invasion of Egypt. The Hyksos or “princes of the desert,” as they call themselves, were nomadic Semites who pushed down into Egypt during the weak condition of the country in the XIVth dynasty. Even during the XIIth dynasty there had been small bodies of Semites coming in, as shown by the celebrated scene at Beni Hasan, where Absha heads a party of 37 Amu;[4] or on a scarab of User-Khepesh, who was the guardian of 110 Amu.[5] At last a flood of nomads, probably driven south by a famine period of drought, burst into the country,[16] much like the Arab invasion of the age of Islam. After plundering the country they settled down, as earlier invaders had done, by adopting the system which they had found there, and becoming kings of Egypt, who restored and enlarged the temples and encouraged learning.[6] They continued, however, attached to their earlier life; and the remains of one king—Khyan—being found as far apart as Crete and Baghdad, indicates that they kept up a wide trade, if not an extensive rule.[7] The title adopted by that king, “embracing territories,” shows that he probably ruled Syria as well as Egypt, like the Syrian King Khondy in the VIIIth dynasty.

It is the nature of the Hyksos rule that enables us to realize the actual setting of the first stage of Jewish history. It is as one of the late waves of nomadic Hyksos that the account of Abraham must be viewed. Wandering round the Syrian desert, as the Hyksos had done, drifting up and down the ridge of hill pastures of Palestine, passing in and out of Egypt as necessity led, the life in the Patriarchal narratives gives the picture of the life of the “shepherd kings,” the “princes of the desert.” The status of these Hebrew wanderers was just that of the people among whom they[17] came in Egypt, the ruling caste of the country, who sat upon the more industrious but less independent Egyptians. They would naturally be received with the affability, and on the easy terms, which are represented. That this was taken in the course of the Hyksos rule is shown by the king having adapted himself to Egyptian feeling, and its being unsuitable to let pure nomads come in to the cultivated Delta, because the shepherds were an abomination to the Egyptians. Hence, though on perfectly good terms, it was preferred to keep these fresh nomads on the border, in the Wady Tumilat, rather than revive the antagonism of the agriculturalist. The story of Joseph falls into place most naturally in Egypt, where even under purely Egyptian kings the highest positions could be held by Pa-khar or Nehesi, “the Syrian” or “the negro.” That this was during a Semitic rule is suggested by the tide of Joseph being Abrekh, the Abarakku minister of state of Babylonia.[8]

The great change of status took place when the Hyksos were expelled, and any remnant of those tribes had to become serfs if they were tolerated at all. It seems highly probable that at this time a part of the Israelites were swept back into Palestine with the retreating[18] waves of defeated Hyksos. It is not only probable, but it is indicated by the defeat of “people of Israel” in Palestine by Merneptah (recorded on his triumphal stele)[9], at a time when the Israelites whom we know of seem to have still been in Egypt. Of the latter portion—with whom we are here concerned—we have only accounts of their serfdom; yet a stray light of a different kind has lately shown that other positions were open to them. On a large family tablet of a chief of cavalry under Rameses II, that is during the age of oppression, the Egyptians are shown worshipping the various gods of the country. The surprise comes where the servants have put their names on the blank edges of the tablet, headed by the “scribe engraver” called Yehu-naam or “Yehu-speaks”;[10] just the converse order of the most familiar phrase, “Thus saith the Lord.” This seems unmistakably to refer to a worshipper of Yehu or Yahveh, and hence an Israelite. Though this is only a single name, it implies a great deal. It shows that an Israelite during the oppression was not only an unskilled labourer, but might be one of the most highly skilled artisans, understanding hieroglyphics, and an artist able to draw and engrave[19] all the figures of the gods. This puts an especial point on the commandment against making graven images, if Israelites were actually engaged in that trade. Further, this man was employed as far south as the Fayum, and thus a hundred miles from the tolerated “Jewry” of the Wady Tumilat. The freedom which the Israelites undoubtedly had under the Hyksos makes it likely that many may have taken up different crafts, and have been scattered about in the country as demand and opportunity led them.

Those who remained in a servile position were not in the least in the condition of being separately bought and sold like cattle, as in American slavery. They were organized in regular families, with their scribes or “officers” of themselves, under the “commanders of tribute” of the Egyptians.[11] In short, their labour was a sort of tribal tax which they had to render, and for which their own headmen were responsible. How and when the individual worked was the affair of his own family and clan, and could not be dictated by the Egyptian so long as the total output was maintained. This is an important part of the status of labour, whether its system is autonomous or is an individual slavery. It seems that the status[20] was that of a tribe heavily taxed for labour, but left to follow its own arrangements. This could only be carried out where there was a solid block of the Israelite population, as in the land of Goshen, the Wady Tumilat. It does not therefore imply any special tax or disability upon those who—like the sculptor just named—had entered on various trades and work scattered in the country. Probably they were gradually lost to sight in mixture with the general population.

During the age of the Judges there was a continuous decadence in Egypt, so that on both sides it is improbable that trade led to any Jewish settlements. The rise of the Jewish kingdom, and the regular horse trade established by Solomon, together with his marriage to the royal family of Tanis, Zoan, and consequent connection with the royal family Bubastis,[12] must have led to some mercantile establishments. Still greater familiarity with Egypt came during the increasing troubles of the close of the Jewish kingdom. About seventy years before the fall of Jerusalem the new Saite King, Psamtek, had established a great frontier fort on the road to Palestine, at Tahpanhes; this was a settlement of Greek troops, and hence open to foreign residents.[13][21] Whenever there was trouble in Judæa, especially from Assyria, this fortress would be the natural asylum of any refugees, and Greek and Jew first mixed here and learned each other’s ways. The results of this mixture are evident in the reference to five cities speaking the language of Canaan, and swearing by the Lord of Hosts, and in the address of Jeremiah to the Jews which dwelt in the land of Egypt, which dwell at Migdol, the desert frontier, and at Tahpanhes, the Delta frontier, and at Noph, Memphis, and in the country of Pathros, Upper Egypt,[14] calling their attention to the desolation of Jerusalem and exhorting them therefore to give up burning incense to other gods in the land of Egypt, where they had gone to dwell already, more than ten years before the fall of Jerusalem. Their reply that they had prospered when they sacrificed to the queen of heaven was met by the prophecy that Pharaoh-Hophra should be given into the hand of his enemies and into the hand of them that seek his life.[15] The meaning of this lay in the politics of Egypt. Hophra was of the party that favoured Greeks and foreigners; but there was a strong Nationalist party of Egyptians who would exclude foreigners, and they sought the life of Hophra, and finally[22] dethroned and murdered him. This led to the exclusive policy which restricted foreign residence under Amasis. This declaration was therefore a warning against trusting to the continuance of the open policy, under which Egypt had been a refuge to the Jews. The fugitive remnant of the royal family and court had found what seemed a safe refuge at Tahpanhes, where the palace-fort had been assigned to them in the Greek camp by Hophra. There Jeremiah had buried stones in the outside platform before the entry of Pharaoh’s house, and the fort is still called “The palace of the Jew’s daughter.” Their patron, however, was to fall, and the open policy with him, and Amasis was—twenty years later—to revive the Nationalist control. He closed down all the Greek settlements and garrisons, only leaving one treaty-port to Greek trade—that of Naukratis;[16] and they paid for this Nationalist movement by falling into the power of Persia in the next generation.

The Persian conquest in 525 B.C. threw open the whole country to influences from all quarters. The series of heads of foreigners found at Memphis shows how the Babylonian traders of the old Sumerian race flocked in, with Indians, Kurds, and a multitude of[23] Scythian Cossacks, besides the ruling race of Persia itself.[17] The picture of this age of Jewish settlement has been preserved in the papyri of Elephantine;[18] and what took place there was assuredly exceeded by the less remote settlements in the rest of Egypt. We find mention of a Jew living at Abydos, which was not a centre of trade. Not only was there a Jewish colony at the Cataract, but one large and prosperous enough to build a temple to Yaho. This temple was older than the Persian invasion, and such a footing is unlikely to have been a new concession by the Nationalists; it probably dates from the time of Hophra’s foreign policy before 570.

The description of the parts which were destroyed later shows that there were five stone doorways, implying that the walls were of brick, like most buildings in Egypt. There were stone columns, bronze fittings to the doors, and a roof of cedar. The vessels of the temple service were of gold and silver. The restorations that have been proposed are rather too extensive for a temple placed in an existing town. Probably, there was a continuous high wall around, a large entrance gate opening on an outer court, from that another gate leading to an inner court, at the back of which[24] was the colonnade of the temple front; the other three doorways named would be that of the temple and those leading to the store-rooms and priests’ dwellings. Though neither the place nor the size of community would allow of a great building, it is seen that the quality of the structure implies that the Jewish residents were on a level with the Egyptians.

Though this temple was destroyed in 411 B.C. by the enmity of the Egyptian priests of Khnum, and the cupidity of the Persian governor Widarnag, yet the parties were so nearly equal that before 408 the governor and all his accomplices had perished by violence, and, in revenge, by 405 Yedeniyeh bar Gamariyeh, a principal Jew of Elephantine, had to flee to Thebes, where he was killed.

Regarding the relations of Egyptians to Jews, it is notable that proselytes were not uncommon. Ashor, an Egyptian, married a Jewess, and took the name of Nathan; Hoshea was a son of an Egyptian, Pedu-khnum; Hadadnuri the Babylonian had a son named Yathom, and grandson Melkiel.

Some matters of status which have been attributed to Babylonian influence may equally well—and more probably—be simple acceptance[25] of the Egyptian laws. In the census for payment of the temple tax of two shekels—presumably from householders—at least one in eight are women, apparently holding independent property. Since in Egypt inherited property was held by women rather than by men, this was according to native law. In marriage contracts either party could stand up in the congregation and denounce the marriage at any time, on payment of a fixed penalty. This was likewise the case in Christian Coptic marriages, as stated by a contract.[19] Hence it must be regarded as the Egyptian law, to which the Jews conformed by necessity or habit.

Thus it appears that the status of the Jewish colonies in Egypt was at least equal to that of any other foreigners, and that they had assimilated native custom and law. The ideas of these settlers at the Cataract, and probably of those elsewhere, were derived from the habits of thought of the monarchy, quite apart from the Babylonian particularism. There was no objection to taking an oath by the goddess of the Cataract, for a legal declaration, like any Egyptian. This is akin to the later Egyptian Judaism, which sought reconciliation with Gentile principles, as[26] in the Alexandrian school of Philo, and was entirely opposed to the bitterly anti-Gentile school which was developed in the Captivity.

It is evident that there was no hesitation in establishing temple worship at the Cataract, and probably also in the other cities that “called on the name of Yahveh,” as a substitute for the destroyed temple of Jerusalem. This is in accord with the establishing of the temple by Oniah some three centuries later. There was not yet the dogma that no temple could be legitimate outside of Jerusalem: that view seems to have been a development of the Babylonian party, probably in connection with their rebuilding of the temple at Jerusalem on the Return from Captivity. A rival temple would probably have been illegitimate at any time; but if the temple of Jerusalem was destroyed, or in the heretical hands of the Hellenic party, then it was looked on as more important to maintain the worship, rather than to abandon it because its true centre was unattainable. This was in accord with Western Judaism, which would subordinate the letter of the law to keeping the spirit of it; in contrast to Babylonian Judaism, which by concentrating on the letter of the law forgot the more important[27] value of it, and thus “tithed mint, anise and cummin, and omitted the weightier matters of the law.”

That the settlement at the Cataract was not very exceptional is shown not only by the reference to a Jewish resident of Abydos[20]—purely a centre of Egyptian religion—but also by a discovery this year of a rock tomb of early date which had been re-used about the fifth century B.C.[21] and inscribed with long documents in Aramaic, equal to over fifty feet of writing. M. Giron came to examine them, but they are so far damaged that it would need a longer study than he could spare to transcribe them. It is to be hoped that some other Aramaic scholar will undertake the work. This tomb is a few miles back in the eastern desert, opposite to Oxyrhynkhos. It proves that in this region of Middle Egypt there was also a Jewish settlement commonly using Aramaic.

The close of the Persian age brought in new conditions under Alexander. Wide as had been the liberty of Judaism under the international empire of Persia, it obtained still more liberal treatment from the Macedonian conqueror. In consequence of the assistance that the Jews had given against the Egyptians,[28] Alexander granted to them equal rights with the Greeks in the new foundation of Alexandria.[22] They had there a separate quarter called the Delta,[23] and they were allowed to be called Macedonians,[24] to mark them as being under royal protection. This status in Alexandria, though suspended by Caligula, was renewed by Claudius. The Jews had also other places assigned to them in Egypt, and were ruled by an ethnarch, who was chief judge and registrar of the whole of the settlers.[25]

In the Fayum they naturally found space, as the province was land reclaimed from the lake, in order to settle Greek troops as colonists. A village of Samareia is named,[26] also Jews in Psenuris.[27] At Thebes Simon son of Eleazar was tax collector.[28] Ptolemy Philopator tried to curb the power of the Jews in Egypt; and the libellous retort on him is the subject of the third book of Maccabees.[29]

The number of Jews in Egypt, and their familiarity with Greek, led to various Greek translations of books of the Hebrew Scriptures.[30] These, in popular rather than literary style, were probably used by proselytes, and followed in synagogues where Hebrew was drifting out of use. They were at last compiled, and probably completed by adding all the remaining[29] books which were familiar as religious literature, though not canonical. Thus seems to have grown up the Greek version known as the Septuagint. Its differences from the Hebrew must not all be assigned to caprice, for its sources probably antedate the formal text of the Masorah. It represents to some extent the sources of the final orthodox text. The production of such a body of translation in Egypt is proof of the large demand that must have existed in a population far more familiar with Greek than with Hebrew.

The next chapter of the Jewish history in Egypt opens out a wide view. The troubles in Palestine caused by the Hellenistic party seizing on the Temple, and the persecutions by Antiochus, had driven large numbers of Jews to settle in the Delta of Egypt; in fact, as later references seem to show, the Eastern Delta was largely occupied by Jews. It was the Hyksos occupation repeated, only in this case the settlement was probably not that of pastoral nomads, but of agriculturalists and traders. The extent of the settlement is indicated by the need for a national centre of worship on a large scale. At first Jerusalem would of course be entirely the focus of religion; but when the Temple fell into the hands of the[30] Hellenizing party, and the High-Priesthood became entirely the prey of violence and bribery, it was more and more difficult to regard the Holy City as a religious home. This severance, and the distance across a long desert journey, would lead to an entire estrangement, and the practical cessation of all Temple worship. The loss of a religious centre, and the presence of an heir of the High-Priesthood, driven out of Jerusalem by the crimes of his relatives, would at last lead to the rise of a new national centre in the midst of the faithful who were thus living in exile.[31] There must have been a large support for the project before Oniah would venture to start so great an enterprise. The vast amount of work that was done in constructing the new city shows that there was a large and wealthy population involved. The letter of application for the site, and the reply granted by Ptolemy VII, seem quite in accord with the times, and there is no reason to suppose that this title-deed of occupation would be lost to sight, and then re-invented.

The site having been granted, of a deserted city, with ruins of an Egyptian palace of Rameses III, and a massive fortification wall of the Hyksos period, there was abundant material for constructing the new city. A[31] large area was laid out beyond the wall of the old city, deliberately modelled upon the plan of Jerusalem and the temple hill. So close is the copy that Professor Dickie in his study of Jerusalem could combine the plans to help in restoring the detail of Jerusalem. The old Egyptian site was adopted as equivalent to the town of Jerusalem, and the new hill was constructed to copy the Temple, and continued northward to imitate Bezetha, leaving a deep gap representing the Tyropœan valley. To throw up these great artificial hills, to face the temple hill with stone walling, up to 100 feet high, to lay out the new city and the fortifications covering six acres, must have needed a large body of supporters, and is the strongest evidence of the numbers and status of the Jews in this district, about twenty-eight miles north of Memphis.

The status of the Jewish settlers in Egypt was influential. Oniah, the heir of the High-Priesthood, was associated with Dositheos, another Jew, as generals of the whole army of Ptolemy VII.[32] He later supported the widowed queen against the attacks of Ptolemy Physcon.[32] He lived at Alexandria, and seems to have been powerful in the court. We also read of an adventurous Jew named Yosef,[33][32] who outbid all the tax farmers and obtained great power, which was extortionately used in the Ptolemaic province of Palestine. Under Ptolemy VII also we find the Jews of Athribis,[34] the central city of the Delta, dedicating a synagogue. The spread of Jewish settlement was far beyond the city of Oniah, as in Caesar’s time the march of troops from Pelusium to Alexandria was dependent on the goodwill of the Jews of Onion.[35] The road between those cities is more than fifty miles north of the city of Oniah, and it seems therefore that the settlement which was in allegiance to that city must have extended over most of the eastern side of the Delta. As the Jews were already sharing Alexandria on equal terms with the Greeks, they must have pretty well absorbed the management of the Delta. It is in this connection that we must view the statement that they had “entire custody of the Nile on all occasions.”[36] Probably as holding mortgages on interest in much of the land of the Delta, they organized a management of the inundation to ensure the solvency of their securities. The modern Debt Control taking over the management of the Irrigation Department is the parallel to the Jewish custody of the Nile.

There was also another and entirely different side of Jewish life in Egypt. In Josephus we read a long account of the Essenes,[37] to which sect this Pharisee of the High-Priestly family had devoted himself in his youth. This account of the Ascetics of Palestine so closely accords with the account that the Alexandrian Jew Philo gives of the Therapeutae in Egypt[38] that they seem to be identical. This spread of asceticism appears to have been started by the Buddhist mission from India. It was entirely foreign to the Western ideals, yet it took root quickly after Asoka’s mission. Indian figures are found of this period at Memphis, and a multitude of modelled heads of foreigners also found there,[17] can only be paralleled by the modelled heads of foreigners made now for a Buddhist festival in Tibet, and thrown away as soon as the ceremony is over. The influence which thus came into Egypt with the Indians of the Persian occupation is found in working order by 340 B.C., and it was probably strengthened and organized by the Buddhist mission in 260 B.C., and so grew until we meet with the full description of long-established communities in the pages of Philo and Josephus. These bodies were apparently composed of philosophical Jews and proselytes largely influenced[34] by the Alexandrine mixture of Oriental beliefs with Greek theorizing.

Though we are reviewing the status of the Jews, that must include their intellectual as well as social position. The Alexandrian school of thought, as we have it in the Hermetic books[39] and in Philo, was a new development in the world, freely reasoning on the nature of God and of man, starting from various beliefs which were chosen for their prominence and compatibility, and coming to conclusions which are curiously similar to some modern thought. These ideas are the ground for various dogmas which naturally grew up from it in the development of that Jewish sect of Christianity.

We turn from these recluses back to the busy world of the Roman age, when troops for Caesar at Alexandria were collected by his General Mithradates, but stuck at Askelon, hindered by the desert and the Delta.[40] Antipater, a Jewish general with 3,000 Jewish troops, joined him, organized the desert transport with the Arabs, and then forced the fortress of Pelusium. On entering Egypt Antipater brought over the Jews of the Delta to the Caesarian cause, and so opened the way across to Alexandria, and this induced the Memphite[35] Jews also to join Caesar. This service was handsomely acknowledged by Caesar.

Augustus rewarded the fidelity of the Alexandrian Jews by giving them a renewal of all the rights and privileges of equality with the Greeks,[41] which they had in the original charter of Alexander. They had an ethnarch and a council, or a president and parliament, of their own; but the Alexandrian Greeks by their opposition to Augustus lost their right to a senate.

Trouble began with the insane Caligula,[42] who tried to force the worship of his own statues in every place. The Jewish refusal of this demand cost them the withdrawal of all rights of citizenship.[43] The Greeks then thought it an opportunity for a pogrom to revenge their subordination under Augustus.[43] On the accession of Claudius the Jews started a riot to avenge themselves on the Greeks.[44] The influence of Agrippa, which had checked the persecution of the Jews before, shielded them again at Rome. Claudius therefore sent a decree,[45] reciting the equality of the Jews and Greeks in Alexandria from its foundation, and the renewal of the rights by Augustus. Another more general decree was published in the Empire, honouring the fidelity of the Jews to[36] the Romans, and declaring that they were in all countries to keep their ancient customs without hindrance: “And I do charge them also to use this my kindness to them with moderation, and not to show a contempt of the superstitious observances of other nations, but to keep their own laws only.” By the end of his reign, however, Claudius ejected all Jews from Rome.[46] Under Nero there was an attempt of Egyptian Jews to liberate Jerusalem.[47] That failing, there was a renewed riot in the theatre at Alexandria between Jews and Greeks, ending in calling in the legions to plunder the Jewish quarter; in hard fight and massacre after it 50,000 are said to have been killed.[48] This seems to have broken the Jewish hold on the capital, and we do not hear of any more turmoil with the Jews in Alexandria.

The great war in Palestine and destruction of Jerusalem immediately after Nero’s reign put an end to Jewish aspirations for a long time. At last a general conspiracy broke out when Trajan was engaged in Parthia, and the Jews in Cyrene, Egypt, Cyprus, Palestine and Mesopotamia broke out in revolt and massacre.[49] Nearly half a million Greeks were slaughtered in Cyrene and Cyprus.[50] In Egypt all Greeks about the country were[37] massacred, or driven into Alexandria for refuge, where they massacred all Jews left in that city. All of this history shows that in numbers and power the Jews were almost the equals of the Greek population, their close organization perhaps making up for lesser numbers. The retaliation by the Roman legions was naturally a full reply to the destruction which had been dealt out to the Greeks. Henceforward there was no united action of the Jews.

The great settlement of Onion, occupying most of the eastern Delta, was depleted at the destruction of Jerusalem by Titus. The Temple of the new Jerusalem was closed in 71 A.C. by Lupus the Prefect;[51] finally, Paulinus within the next few years stripped the place, drove out the priests, shut the gates, and left the place to decay. This repression was not sheer persecution on the part of the Romans, but was caused by the Zealots, who had made the worst of the Palestine war, escaping to Egypt, and going even as far as Thebes.[52] In the interest of peace it was needful to abolish a religious centre which might have been made a rallying point for later trouble.

Although history scarcely mentions the[38] Jews in Egypt for some centuries, they were by no means expelled. As traders, perhaps as cultivators, they kept a place in the country. A surprise has come in the last few weeks by the discovery at Oxyrhynkhos, in Middle Egypt, of fragments of four papyri written in Hebrew, as early as the third century. These are thus the oldest Hebrew writings known, apart from stone inscriptions. The age of them is given by another papyrus found with them dated under Severus, 193-211 A.C. One Hebrew writing is on part of a Greek document, which by the hand is probably of the third century. The style of the Hebrew will quite agree to this, as it is closely like the synagogue inscriptions of the first century, as pointed out by Professor Hirschfeld, who has examined these papyri and made a preliminary transcript. With these letters are scraps of a liturgical work on parchment with minute writing. Two of the papyri appear to be dirges, one on the destruction of the Temple. Another papyrus has Jewish names, Joel, Nehemiah, and others.

Though the Jewish half of Alexandria had been severely, if not altogether, reduced in the great rebellion under Trajan, there had been a large return of those who were attracted by the powerful centre of commerce and activity.[39] Once more a pogrom broke out, from the fanatical Cyril in 415, who expelled the Jews, while the mob sacked the Jewish quarter.[53] Yet they returned, as, a couple of centuries later, at the conquest by Islam the Jews were expressly allowed to remain, according to the articles of capitulation.[54] During the rule of Islam the position of the Jew has fluctuated like that of the Christian. Restrictive laws have sometimes been passed, as that of El Hakim, ordering Jews to wear bells or to carry a wooden calf,[55] or the later restriction to wearing yellow turbans.[56] Yet Jews have risen to high power, as the slave-dealer who became supreme in the childhood of Ma’add about 1040, and set Sadaka, a renegade Jew, as vizier in 1044.[57] Though in recent times the Oriental Jew has little hold in Egypt, the European Jew has been a moving force in finance and enterprise.

The general conclusion appears that Egypt from its position and its fertility has always attracted the Jew. It has had therefore a notable influence on the mental attitude, especially in the Alexandrian school of the Wisdom literature and Philo. The status of the Jewish population has been fully equal to that of the other important races, native[40] and Greek, especially in the great Jewish occupation under the Ptolemies, which was perhaps the age of the greatest political power in Jewish history.

REFERENCES IN TEXT

[1] Petrie, History, i, Fig. 6.

[2] Petrie, Scarabs, xix; Egypt and Israel, Fig. 1.

[3] Clay, Empire of the Amorites.

[4] Petrie, Egypt and Israel, Figs. 2, 5.

[5] Petrie, Scarabs, xv, A.C.

[6] Petrie, History, i, Apepa 1.

[7] History, i, Khyan.

[8] Hastings, Dict. Bib., Abrekh.

[9] Petrie, Six Temples, 28.

[10] To appear in Herakleopolis.

[11] Ex. v. 14.

[12] Egypt and Israel, 68.

[13] Petrie, Tanis, 11; Defenneh, 48-53.

[14] Jer. xliv. 1.

[15] Jer. xliv. 30.

[16] Petrie, Naukratis, 7.

[17] Petrie, Memphis, 1, xxxvi-xl.

[18] Hoonacker, Une Communauté Judéo-Araméenne.

[19] Petrie, Gizeh and Rifeh, 42.

[20] Hoonacker, 39.

[21] To appear in Oxyrhynkhos.

[22] Josephus, Wars, II, xviii, 7.

[23] Wars, II, xviii, 8.

[24] Wars, II, xviii, 7.

[25] Josephus, from Strabo, Antiq., XIV, vii, 2.

[26] Mahaffy, History of Egypt, 92.

[27] Mahaffy, 93.

[28] Mahaffy, 192.

[29] Mahaffy, 145.

[30] Thackeray, St. J., The Septuagint and Jewish Worship, 11-13.

[31] Petrie, Egypt and Israel, 98-101.

[32] Josephus, Cont. Apion, ii, 5.

[33] Antiq., XII, iv.

[34] Mahaffy, 192-3.

[35] Wars, I, ix, 4.

[36] Cont. Apion, ii, 5, end.

[37] Wars, II, viii.

[38] Petrie, Personal Religion in Egypt, 63.

[39] Pers. Relig., 38.

[40] Antiq., XIV, viii.

[41] Milne, History of Egypt, 16.

[42] Antiq., XVIII, viii.

[43] Milne, 29, 30.

[44] Milne, 31, 32.

[45] Antiq., XIX, v. 2, 3.

[46] Acts xviii. 1.

[47] Milne, 35.

[48] Wars, II, xviii, 8.

[49] Milne, 52.

[50] Dion Cassius, Trajan, end.

[51] Wars, VII, x, 4.

[52] Wars, VII, x, 1.

[53] Milne, 98-9.

[54] Stanley Lane-Poole, History of Egypt, 11.

[55] Lane-Poole, 127.

[56] Lane-Poole, 301.

[57] Lane-Poole, 137.

APPENDIX

ANCIENT HEBREW PAPYRI

Provisional Translation by Dr. H. Hirschfeld

| FRAGMENT A | |

| LINE | |

| 1. | (relic of selah [?]). |

| 2. | Wells ... hewn ... |

| 3. | To lead ... to this ... |

| 4. | They rejoice ... they decay ... |

| 5. | In the light, or (with ח added) the path ... |

| 6. | Of the Temple ... He has put to shame ... |

| 7. | They trembled, languished, turned to Thee ... |

| 8. | With glee and holy convocation ... |

| 9. | In the assembly of holy myriads ... |

| 10. | When mountain peaks frowned (see Psalm lxviii. 16-17) ... |

| 11. | Myrrh and cinnamon ... |

| 12. | I am inundated with tribulation ... |

| 13. | ... |

| 14. | Kings ... |

| 15. | Engraved. |

| 16. | Remember and ... |

| 17. | ? |

| (Probably a lament on the destruction of the Temple.)[44] | |

| FRAGMENT B | |

| 1. | ? |

| 2. | surrounding (?) |

| 3. | ? |

| 4. | path ? |

| 5. | |

| 6. | upon the earth (land ?). |

| FRAGMENT C | |

| 1. | ? ? |

| 2. | ? |

| 3. | ? |

| 4. | ... males ... |

| 5. | ... and avenge the sanctuary ... |

| 6. | Thou hast ... ? us a kingdom of priests ... |

| 7. | ... a kingdom ... ? |

| FRAGMENT D | |

| 1 to 5. | illegible and untranslatable. |

| 6. | Joel ... ? |

| 7. | And Nehemiah. Nahor ... ? in judgement (?). |

| 8 to 10. | illegible ... |

Printed in Great Britain by

UNWIN BROTHERS, LIMITED

LONDON AND WOKING