Title: Corporal Tikitanu, V.C.

Author: J. C. Fussell

Release date: January 31, 2018 [eBook #56471]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Ernest Schaal and The Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from scans of public domain works at The National

Library of Australia.)

BY

J. C. FUSSELL

(Author of "Letters from Private Henare Tikitanu.")

AUCKLAND:

Worthington & Co., Printers, Albert Street.

1918.

Cover design by permission of Proprietors Auckland Weekly News.

The first time I remember catching sight of Henare Tikitanu was when he was acting as referee at a dog-fight in a Maori village in the Waikato district.

The dog-fight was no concern of mine. I was just riding past when my attention was drawn to Henare. He was endeavouring to see fair play for both the combatants. He was very excited over the affair because another Maori, named Wiremu, was hampering one dog by pulling his tail.

[pg 6] After fruitlessly yelling at Wiremu for some time in classical Maori, Henare suddenly relapsed into pidgin-English, and fired this volley at him: "Py cripes, you te ploomin' ole taurekareka,—tinkin' fish—all right. You no good for te fight. More better your ole woman drown you in te hot mud hole when you te piccanini. Gar!"

Then they flew into each other's arms and settled it that way. The dogs looked up in surprise, retired to a safe distance, and watched the proceedings, giving an occasional bark of encouragement.

Henare won. He deserved to, for he was a clean fighter and a true sport.

This event happened about two years before the Great War broke out, when Henare was eighteen. So it was not surprising that he should have been one of the first of the Waikato tribe to volunteer for service at the front, when he had reached twenty-three.

But he had his difficulties. You see [pg 7] he had a sweetheart named Kiri, a fine Maori maiden of twenty; and Wiremu wanted her. Henare and Kiri had been sweethearts from early school-days, and they rather laughed at Wiremu's aspirations. But if Henare went to the war, it might be different. During their moonlight rambles along the banks of the dark and silent Waikato river, Henare and Kiri talked the matter over. He said he would enlist if they could be secretly married first. He said he would feel more settled, and more disposed to fight, as his forefathers fought of old, inspired by the love and admiration of his wahine.

Kiri was undecided. The war might be long; the distance to France was great; the dangers and risks were many.

[pg 8] Henare naively chaffed her by saying that he might pick up an American heiress away over in Paris if she did not marry him before he enlisted. That settled it. Before they left the shade of a beautiful pohutukawa one charming summer's evening they fixed the day and made their plans—talking to one another in soft and musical Maori.

"You will be true to your absent warrior as he fights beside his Pakeha brothers, adding fresh glories to the honour of the noble Maori race?"

"Yes, my brave Tikitanu. Your Kiri will be with you in heart and spirit day and night until your return to the fair land which holds in its bosom the bodies of our noble heroes of days gone by."

A few gentle and poetic words like these made them both feel rather sentimental and emotional, so they solemnly rubbed noses and went back to the kianga.

These two dusky lovers decided on a [pg 9] secret marriage at Ngaruawahia in a fortnight's time. Kiri was to go by road to the place, and Henare by train from Mercer.

The appointed day dawned bright and fine, and Kiri arrived at Ngaruawahia in proper style half-an-hour late. But there was no sign of Henare.

As a matter of fact he did not turn up at all, for he got a bit excited at Mercer, and as there were two trains standing end to end at the station he entered the wrong carriage and got out at Pukekohe, about thirty or forty miles in the wrong direction.

They met again in about two days' time, and after a good deal of both tender and violent Maori talk, sprinkled with pidgin-English, the matter was patched up.

However, they dropped the elopement idea, rubbed noses duly and canonically, and Henare went off and enlisted as a soldier of the King. But he was anxious about his old enemy Wiremu.

The relatives of Henare and Kiri were very proud of Henare in his new uniform, and they told him that he must prove himself worthy of the hand of Kiri, the Maori princess, and grand-daughter of a great warrior chief.

Henare looked at himself in the glass and felt that he was worthy of her, or any other princess, already. He did not want to seem too cheap, because there was Wiremu to be reckoned with.

He enjoyed the camp life, the drills and parades, and entered into soldiering with as much ease and good will, as if he had been born to it.

The general opinion of the officers was that Tiki (or "Dickie" as they nick-named him) would give a good account of himself at the front.

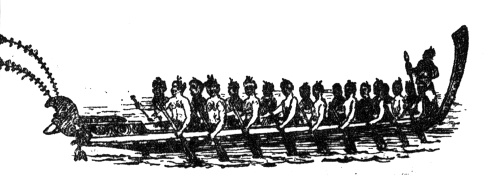

[pg 11] It was a great day in Wellington when the first batch of Maori volunteers embarked on the grey troopship. Henare and his mates were bubbling over with fun and excitement. The cheering crowds of Pakehas and Maoris, the fluttering flags, and the cheerful music of the bands, made them all feel that they were off to a grand old picnic. They laughed and joked, and sang until they were hoarse.

A few hours later, however, things did not look so bright. These Maori lads had never been away from New Zealand before, and it was sad to see their beloved land sinking out of sight into the deep blue ocean.

When the last trace had disappeared, Henare, leaning over the vessel's side, said to Honi in a hoarse whisper: "My korry, Noo Zealan' all gone now." Honi replied with affected cheerfulness: "Nemine, he jump up again bimeby," and then walked away.

[pg 12] All the boys tried to make out that they were not seasick, and poked themselves away into all sorts of nooks and corners to conceal the fact.

Henare thought that up in the rigging would be a good place, but they soon chased him out of that. He then leant over the taffrail and mused of home and Kiri.

A voyage to England in these days is eventful for anyone, but it was very much more so for the Maori boys.

When they had settled down to the routine of life on a troopship, they became keenly interested in it all and never had a "dull" day.

The first port of call filled them with much excitement and gratification—and a thirst for further adventures.

Henare rather prided himself on his letter-writing, and seized every opportunity to exercise his "gift." He disdained to write in his native language, but preferred [pg 13] "te good Englan' talk" even when writing to Maoris. At the first port he posted several letters to friends in New Zealand. One was to Kiri and another was to Wiremu.

To Kiri he wrote, among other things:

"I no forget about you yet, t'that why I write t'this letter, tell you no forget me. More better you have te British soldier than te frightened bloke like Wiremu stoppin' away from te fight. T'this ole troopship take us over te sea all right, and when te war all over he bring us back an' t'then I marry you pretty quick."

To Wiremu he wrote:—

"Py cripes, you look out when I come back if you talk too much wid te Kiri. She no belong to you. She my wahine all right. No good yer trick, you better come to te war; no stop home spoilin' te dog fight [pg 14] and try take another feller gel when him away in Shermany. Me te crack shot now so you look out."

After a voyage of nine weeks without serious mishap the Maoris landed in England "All well," and ready for the Huns.

It was not very long before the Maori boys, who had gone straight to old England, were drafted across to France, and they were soon in the thick of the Great War, fighting for all they were worth.

Henare was well to the fore, and it was often remarked that he would soon distinguish himself or know the reason why.

In fact, all the Maori boys were as keen and fearless as any of their Pakeha comrades, and made a deep impression on all the officers and men about them—and on the Germans in front of them too!

At every turn Henare proved himself a wag, a wit, and a hero. He caused many a hearty laugh by his quaint comments on the Anglo-French gibberish, and the [pg 16] churned up conditions of the country—"Py korry t'this country like te kramble egg on tose." He called the mixed-up speech "te half-caste langwidge."

But everyone was cheerful and witty on that battlefront—though sometimes there was a grim lull in the fun; just before a battle, and in the thick of it. The wittiest men fought the most desperately, but saved their wit for a pick-me-up afterwards.

During an awful fight over shell-holes and battered trenches, Henare was too eager and daring, and the result was a bad wound in the chest by a fragment of shell. He was unconscious and bleeding profusely when picked up by the Red Cross men, so, after first aid, he was conveyed with all speed to the base hospital. He soon became delirious and [pg 17] was not expected to recover.

One night about twelve o'clock he opened his eyes and glared at an attendant standing near his bunk. Then, without a moment's warning, he sprang up and grabbed the attendant by the throat yelling at the top of his voice, "Py Hori, you bally ole nigger Wiremu, I catch you t'this time." With some trouble he was put back to bed again, and relapsed into unconsciousness.

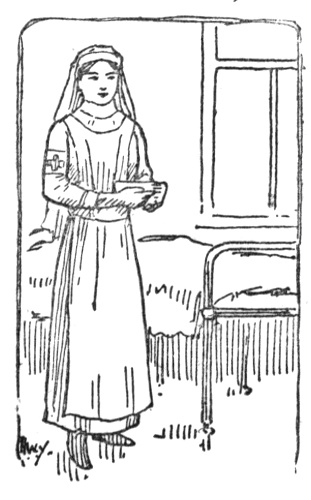

The next time he awoke, a pretty little French nurse, Marie Bouvard, was sitting by and watching him. She was just a slim little thing, more like a girl of seventeen than a woman of twenty-one. She was a born nurse, her very presence always did the sufferers good. Her voice was soft and healing, her touch was gentle and sympathetic, [pg 18] and her footsteps were like the falling of the snow.

When Marie smiled she was at her best, for her solemn little face brightened up like a sudden burst of sunshine on the flowers.

Henare watched her calmly for some time without moving, then he closed his eyes, and the man in the next bed heard him murmur,—

"Py ... korry, Py ... korry, I tink I got to Heaven at lars ... t'that the angel face all right ... you bet."

It is not surprising that under the care of a nurse like the little French Marie, the Maori hero gradually recovered. When he had reached a certain stage of recovery, he did not appear to be particularly anxious to progress any further. Most of Marie's patients felt like that. It meant parting [pg 19] with the charming little nurse, and they dreaded it.

Henare was no exception, though, be it said, Kiri was never far from his thoughts. But Marie simply fascinated him, and really the nurse herself became very much attached to the noble brown boy from England's far off Maoriland. He had been such a splendid patient, and such a grand "case" too.

As time went on, during Henare's convalescence, he and Marie became at least very good friends, and always enjoyed one another's company, and whatever conversation it was possible for them to have, with Anglo-French and pidgin-Maori as the medium.

In the middle of this pretty romance, Henare got a letter from Kiri, and it had a steadying effect upon his emotions. For patriotic reasons it was written in pidgin-Maori. Partly it ran,—

"I hope you no get kill too quick yet. Wiremu no good for me, he te shirker bloke. T'that why I want you come back without te shot. Wiremu tell my mother all te Parani gell want to marry te Maori soldier. No you get up to that trick with me.

Good-bye, come back quick when you beat te Sherman. I wait."

Kiri x x x x x

Seated cosily in an easy chair, with Marie near by at work on some bandages, Henare was listening most attentively to her efforts to tell him some of the dreadful sufferings of France in the early days of the war.

It took him all his time to make out what she said. The scene was a sadly busy one. There were several interruptions, many were coming and going all the time. Fresh batches of broken and groaning men were being brought in every hour; and restored men were taking farewell of nurses and friends before returning to the slaughter.

The cannon-boom could be distinctly heard day and night, but it disturbed no one at the hospital, for they had grown accustomed to it.

[pg 22] All the while Marie was talking, in the midst of this strange sad scene, the irregular punctuation kept on.

Boom—boom . . . . boom . . . . boom—boom—boom.

With many a shrug of the shoulders, and many a shake of her pretty head, Marie related to Henare all she dared of the brutal and revolting conduct of the Germans when first they swept over the border. She told him of the coarseness, the drunkenness, and the bullying of all ranks and grades of the invading Huns.

Every now and again Henare ground his teeth, and muttered "Py cripes; I pay him out," and "Te taipo, te bally taipo." When he heard as much as he could stand, he ventured the remark, "I tink the Sherman soldier no hurt te gell and te woman, eh?"

Marie looked at him a moment, and then said, "What you say, M'sieur?"

[pg 23] "I say te ole brute no hurt te wahine an' te piccanini—te woman an' te gell"—he answered slowly.

"Oh dear me," said Marie in real surprise, "did you nefar read ze newspaper?"

"Oh, my korry," he replied, "I can't read te Prenchy langwidge, all te word spell wrong, and te talk all silly."

"No, no, no, M'sieur, ze French speech ees ze most beauteeful in all ze land."

"Werra, where te Maori come in?"

"Ah!"

"Eh?"

When left to himself the manly Maori boy pictured up the whole scene as well as he could, and longed to get back to the trench—or over the parapet—to pay out the demons who had outraged Marie's noble people. He was getting well unusually quickly, and though loth to leave the [pg 24] charmed spot, he felt that he would soon be fit to fight again. He was busy thinking out all kinds of plans for getting even with the Huns; and he formed a mental picture of the Kaiser which was not very complimentary to that potentate. Henare saw him as a big villain with short, sharp horns above his ears, to match his upturned moustache; small wicked eyes, and a big mouth, with little tusks protruding.

This image was very vivid to Henare's native imagination, and he muttered to himself, "Py cripes, that him all right; he just want te cow feet and te monkey tail, then he te ole taipo, straight."

[pg 25] A week after his chat with the little French nurse, Henare was passed as fit for service again. He had made many friends, both French and English, around the hospital; so on the day of his departure he hunted up each one and solemnly shook hands and said "good-bye." He came to Marie last of all. She was standing just outside the big, sunlit doorway, watching the far off train of waggons slowly bringing in another batch of wounded men. Her sweet little Frenchy face looked dreadfully serious—but she turned round with that sunny smile of hers when Henare spoke.

He shuffled nervously, gave a funny little cough, that he ought to have been ashamed of as a "Maori brave," then held out his hand and said, "So long, Marie, I go back now. My korry, you make me get well too quick."

She put her head picturesquely on one side, took hold of the brown hand held out [pg 26] to her, and said, "Au revoir, Henri; I hope you weel be vera safe."

Henare felt queer. Sensations passed all over him that he had never known before. The impulse was to pick up this lovely French doll and run right away with it. But he pulled himself up and said, "Py cripes, I better go, I tink," and he bolted.

On the way back to the lines a New Zealander was chaffing Henare about Marie, and asking him whether he was going to hand over Kiri to Wiremu.

"No ploomin fear," he replied, "Not me."

"What about Marie, then?"

Henare stopped short and said—

"I tell you bout that, mate. I like to have Marie just for te pretty doll. She te beauty, py cripes, yeh. When she put te head on one side an smile, she mak me feel wery funny on te shest, t'that all!"

"Hey boss, what te name of t' place where te Kaiser stop?"

"Potsdam."

"Eh? No fear! T'that te bally swear word."

"No it's not, Dicky; that's the place all right."

"Oh, py korry, I no like to put t'that on te letter; te gell in te Post Oppis might see him."

The officer whom Henare addressed laughed heartily, and said—

"Your compunction is evidently due to the refining influence of Nurse Bouvard, eh?"

"Oh, go on, you got te rat," he replied.

[pg 28] When he was quite convinced about the Kaiser's address, Henare proceeded to make use of his "gift" at letter-writing for an attack on him by post.

To Kaiser Pilly,

Potdam.I been come all te way from Noo Zeelan to fight te Sherman soldier in Parani and make him clear outer t'this country. When I come here some feller been tell me all about t'that dirty trick all te Sherman been up to in Parani an Peljimi. No good you say t'that all gammon, it te true talk all right. What te taipo you want to make te wery big fight for? More better you keep your ole Sherman soldier in Shermany—t'that te place for him. Py cat, he not fit for go any more place—cept herra.

I tink you te bally ole fool you tink you goin to beat Englan. No good for you try t'that game. [pg 29]

What about te Maori? He not too many, but py korry he te beggar for the fight.

What about te Pritis Navy? He chase every ploomin Sherman ship off te sea; an keep te Sherman navy in te wery safe place—friten to come out.

What about te wery strong tank, an te wery quick harepeni flyin about everywhere?

Py cripes, you te wery bad ole man make all te fight for nothing. You goin to get lick bimeby.

What te good of t'that silly bloke you got over there—te Klown Prince? he no good for te fight, only for te smoke an te peer.

Now, I tell you what we goin to do, straight. We goin to keep on t'this fight till all you Sherman bloke plown up sky-high. You want ter fight te Pritis; werra, py korry, you got ter fight to te [pg 30] finish up now. No time ter stop an spit on yer hands—got to keep on wid te war widout te holiday. No ploomin harmitis (armistice) for te Pritis—we know t'that trick all right.

If you had enough an want ter stop te bally fight, I tell yer what yer goterdo: Clear out of Parani an Peljimi, an all te place where ye got no ploomin right to stop in; pay all te peoples for te house an te pretty church you been burn an break him down; give Englan all t'that navy which he hidin away in te dark; an, t'then dont you try t'this dirty trick any more, or py cripes you get wipe off te map nex time. T'this letter no te humbug, he te true talk; you find that out bimeby all right. Py cripes, you goin ter get it straight for the start this wery bad war. You better hurry up quick an get sorry, plenty more Maori boy in Noo Zeelan gettin ready to come an fight.

Henare Tikitanu.

[pg 31] Henare took great pains to write what he felt was a very convincing ultimatum—and, after much scratching out and altering, he sealed the letter and gave it to an airman to drop behind the German lines. The censor passed it with a merry laugh.

It was a great relief to Henare's troubled mind to get his letter to the Kaiser written, and sent off by its famous postman; in his native simplicity he felt that he had dealt the German Emperor a blow from which that old Fritz would not quickly recover. He had told him as plainly as possible what a Maori soldier thought of him, and that of course would affect the Kaiser's "morale."

The incident also got him talked about, until his resourcefulness and bravery came under the notice of the authorities, with the result that Henare was made a Corporal; which fact he duly mentioned in a postscript to some of his letters—with pardonable pride.

He now became more zealous and daring than ever, making quite a business [pg 33] of the war. He was turning out to be one of the best soldiers in the British line; an encouragement and inspiration to all about him.

But his zeal and daring often nearly cost him his life, and eventually cost him his liberty. It happened during a most unexpected gas attack. Henare lingered too long, was overcome by the poisonous fumes, and was taken prisoner by the Germans.

He was not badly gassed, so when he recovered enough to walk about he wanted to fight one of the guards, but a London Tommy restrained him. Henare appeared to be the first Maori prisoner captured by the Germans, for they regarded him with a good deal of interest, which he resented with expressions that were wasted on his captors.

He soon chummed up with his fellow-prisoner—the London Tommy, who urged [pg 34] him to be less talkative, so as to avoid trouble. But, as Henare could not indulge in his favourite pastime of "letter writing," he persisted in talking to Tommy about the war. He told him wonderful stories about gigantic preparations on the British front, and about the inexhaustible resources of New Zealand.

Several of the sentries understood English and Henare was listened to with undisguised interest. Then he was sent for, and taken between two guards to a German officer, who was very affable to Henare, and asked him several kindly and interesting questions. Had he quite recovered from his unfortunate "gassing"? Did he get enough to eat? Was it the kind of food the Maoris were used to? and so on.

After this the officer told the guards to withdraw twenty paces. He then smiled at Henare and asked him, in broken English, whether he would like plenty of [pg 35] money and a certain amount of freedom during his stay in Germany.

Henare grinned and said that would be "kapai."

"Vell, you shust tell me some leedle tings about der English."

"All right, I know plenty ting about him. What yer want ter know?"

"Ah! dot is goot! Now tell me how much damage der German bombs do on London."

"Wery bad, wery bad. Him brake down te shop, te church, te school, and te piccanini."

"Och! anyting else?"

"Yeh; kill te plenty ole woman too; my word yeh, te Zepp wery bad for ole Englan."

"Haf England got much food?"

[pg 36] "Not too many; only butter from Noo Zeelan."

The officer made a note of that, as a most significant fact. He then asked:

"How many soldiers vos coming from New Zealand efery mont?"

"Oh, tousan an tousan. Not enuf ship yet to bring him all."

"How many Maoris vos der bein trained?"

"Oh, bout two million, I tink."

"Gott in himmel! Are dey as big as you?"

Henare grinned and said:

"Oh, te Maori bigger 'n me. Me te little bloke, all right. No room for te big Maori on te ole troopship I came in."

The German looked thoughtful, and a bit suspicious.

"Are you telling me der truth?"

[pg 37] Henare fixed his soft brown eyes on the small blue-grey eyes of his questioner, and said, with well-feigned indignation:

"Oh, py korry, me te Sunday School poy; what for you tink me tell a lie?"

"Vell, I will ask you von more question:

"Vat do all dose big Maoris feed on?"

"Oh, te Pakeha no let te Maori eat up te prisoner now, so he eat te poaka."

"Vat is der poaka?"

"Te pig, te Sher——, I mean te Noo Zeelan pig. But te Maori like te prisoner more better."

Although the German officer was not at all satisfied with the result of his enquiries, he made up his mind to treat Henare well, with the object of getting all the information possible from him.

With their usual lack of humour, the Germans fondly imagined that they would yet be able to get some valuable information out of the "unsuspecting" native of New Zealand; for he seemed so agreeable and talkative! Little did those self-conceited Teutons understand the Maoris!

This being so, Henare was allowed a certain amount of liberty to ramble about within a given area—well behind the lines.

Two weeks after his capture a most astounding thing happened—as if it had been long cut and dried. During a semi-bright moonlight night a British plane [pg 39] made its appearance over the camp, and was being duly shelled. Presently it wavered like a wounded bird, then rapidly descended to a spare piece of ground near where Henare rambled. Hurrying towards it he found that it was not "wounded," but had alighted for a minor but necessary adjustment. As Henare approached, the airman drew his revolver, but the Maori threw up his arms and cried out:

"Hey! Don't shoot! Me te Pritis prisoner."

"Be the saints," came the reply, "Yez don't look much like a prisoner! Phat the mischief are yez doing here?"

[pg 40] "Py korry, you better hurry up—all te Sherman looking for you. I tink you better take me up in te sky, too. I can ride."

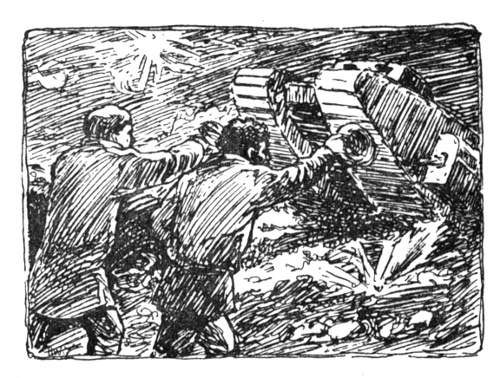

With that they both jumped into the plane, fixed the straps, and flew away. Only just in time, however, for bullets and shells soon began once more to liven things up. The plane dived, and swooped, and looped the loop until Henare thought his woolly head would drop off. They then had a safe run for an hour, but just as the aeroplane was crossing the German lines she was winged and had to descend in No-Man's-Land. Enemy searchlights soon discovered where they landed, and shells started to dance and sing all around them. The two men left the machine just before it was blown to pieces. They hid for awhile in a crater, until the welcome sound of a tank was heard. Presently she was seen lumbering along in the moonlight. Henare and the Irish airman made for her [pg 41] with all haste, waving their caps. The tank lurched towards them suspectingly, and then came to a standstill.

When the back door opened a voice called out:

"Weel naw, an' who might ye be?"

The Irishman answered:

"We're just lookin' for a bhuss to carry us back to the loines."

[pg 42] "This wee cabby is no takin' passengers, but maybe ye can squeeze in—for its rough walkin' here."

They had not travelled—or lumbered—far when the old tank tumbled headfirst into a deep shell-hole. With difficulty they all crawled out and had a good look at the undignified position of H.M.L.S. with her nose fast in the mud.

Each one of them said a few simple words suitable to the occasion. Henare's contribution was—"Py cripes! she can buck worse'n te wild Maori hoss."

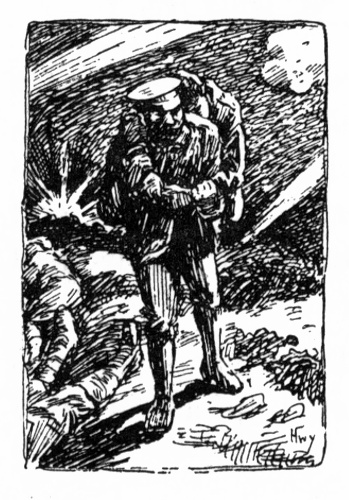

There was nothing for it now but to walk. The enemy shelling became so fierce that the wanderers separated and dodged along—each man for himself—hiding here and there, and sheltering from time to time in large craters.

Dead and dying men were lying about in all directions—giving evidence [pg 43] of recent heavy fighting. When Henare realized this, he forgot his own danger and set to work carrying wounded men—British and German—to the shelter of a crater.

Searchlights were on him nearly all the time, while bullets whistled past him and shells ploughed up the ground. He still pegged away at his noble work, until a bullet found him as he was bringing in his twentieth man—an English Captain. He had just managed to roll into the crater with his burden and then collapsed. The Red Cross picked them all up the next afternoon.

Henare was in the hospital when he came to. He was staring wildly [pg 44] at the man in the next cot—a big, brown man, bandaged, but grinning away cheerfully.

Yes! it was Wiremu all right. He had finally enlisted and the military training had made a man of him. In a desperate battle Wiremu was badly wounded, and was one of the first men that Henare had carried to the crater.

When Henare had got over the shock of meeting Wiremu, he asked after Kiri.

"Oh, she all right Henare, when I left Noo Zealan. She no forget you. She te brick."

[pg 45] And so, far into the night, the gentle murmur of musical Maori was heard as these two wounded heroes discussed the war, and old time quarrels, and Kiri's loyalty to Henare, and also the good times they themselves would have together in New Zealand, when the war was won.

It was a very happy Maori soldier who was in London a month later, preparing to go before the King and receive the noble and much-coveted badge of V.C.

When Henare left the kindly French hospital, Wiremu was getting over his wound,—more quickly than he wished, for he had completely fallen in love with Nurse Marie, and was using all the arts and devices known to the civilized Maori, to win the affections of that charming little angel of mercy.

As for Henare himself, he was not again passed for active service, but received orders to return to New Zealand, after he had obtained the highest badge of honour at the hands of the King.

[pg 47] On the day fixed for the ceremony he was all excitement. He put his things on wrong, and had to take them off again; lost belongings, and wanted to fight those that he suspected of taking them.

But the most confusing time was when they were telling him how to behave at the ceremony and in the presence of His Majesty. He couldn't remember for five minutes what he had to say and do.

At last he said to the officer instructing him—

"Py korry, mate, I gettin' too shaky. More better you get te Wikitoria Cross an bring him to me—an I get home quick."

"That would never do, my boy; half the honour is having the medal pinned on by the King himself."

"My wurra, I tink you right. We better go now; King Hori he get too tire waitin' for us."

[pg 48] Though still weak, Henare had lost all his nervousness when they arrived at Buckingham Palace grounds. He watched everything with the keenest interest, and did not hesitate to quaintly express his opinion about anything that took his fancy.

The officers felt a bit anxious when Henare showed signs of talkativeness as the King was pinning the V.C. on his breast, but they could see by His Majesty's pleasant smile that no harm was being done. No one could help smiling when Henare remarked to the King—

"Py cripes, you got te wery fine whare here."

Anyhow, the impressive ceremony passed off without a hitch, and Corporal [pg 49] Tikitanu, V.C., looked every inch a British soldier and hero—admired of all.

The very next thing to be considered was "New Zealand" with all speed.

At last, after an absence of nearly twelve months, into which were crammed the experiences and feelings of years, the Maori brave returned to his native land, bringing with him the fame and the honours he had so nobly won.

The wildest enthusiasm prevailed at the reception in Henare's native village. Maori and Pakeha customs and phrases followed one another in quick succession in the eager desire to express a joyous welcome.

"Haeremai's" were shouted at the returned soldier boy from every quarter of the crowd; vigorous nose rubbing threatened to become serious, until it was relieved by the more European ceremony [pg 50] of carrying the hero shoulder high through the excited crowd. When they reached a flag-bedecked platform, Maori orators poured forth a flood of poetic welcome, until the women broke down and wailed their solemn tangi.

As Henare stood up to reply the ground shook with the hakas and feet stamping. It was a real ovation that the loyal brown-boy received.

For the sake of the distinguished Pakehas present, Henare spoke in pidgin-English. He had often heard about the great Lord Kitchener, so he began by saying:

"Te Pritis soldier no talk too much. He te man of the do things, not t'talk it. T'that why I no got too much for te speech."

He then thanked them all very warmly for the kind and unexpected welcome they [pg 51] had tendered him, and concluded with this:

"Any bloke here want te nice soft job, no good for him go to te Sherman war; more better him stop home wid te mudder. But if all you big fat feller want to be te MAN and te decent bloke, get outer Noo Zeelan quick and help all your mate lick up te Sherman."

Kiri, his faithful Maori maiden, was foremost among those who welcomed him home; and the Rev. Honi Maki celebrated their happy wedding a week later.

Bearing on his body the honourable scars of war, and on his breast the King's acknowledgment of his bravery and loyalty, Henare spent his days going in and out among the Waikatos and neighbouring tribes, telling [pg 52] them thrilling tales of Britain's might and honour; and showing them the terrible need there is for Pakeha and Maori alike to do and dare—for the sake of Britannia, the friend of Justice and Liberty.

WORTHINGTON & CO., PRINTERS, ALBERT STREET, AUCKLAND—5380

"LETTERS FROM PRIVATE HENARE TIKITANU."

By J. C. FUSSELL.

"A very humorous account of the experiences and impressions of a typical Maori soldier on the long journey from New Zealand to France."

"If you can't raise a smile for Private Henare there is a fissure somewhere in your diaphragm."... "It is a quaint and appropriate greeting to send to friends across the seas."

"The Booklet will have a large and ready sale because of its decided merit and originality."

"They are splendid, and just the thing for sending to the trenches."

"The letters of the Maori soldier, as he sees active service."

Throughout the dialogues, there were words used to mimic accents of the speakers. Those words were retained as-is.

The illustrations have been moved so that they do not break up paragraphs.

Errors in punctuations and inconsistent hyphenation were not corrected unless otherwise noted.

On page 24, "villian" was replaced with "villain".

On page 25, "her's" was replaced with "hers".

On page 42, "H.M. L.S." was replaced with "H.M.L.S.".