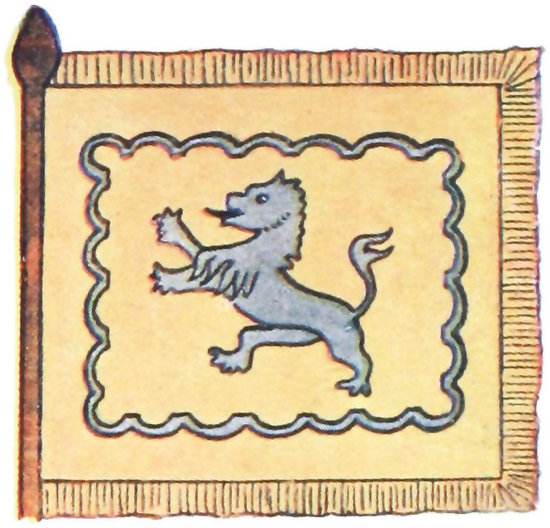

1. Second Troop of Horse Guards, 1687.

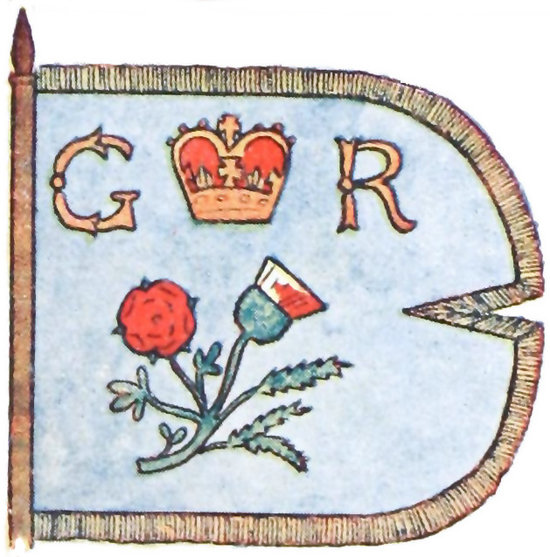

2. 5th Dragoon Guards, 1687.

3.

4.

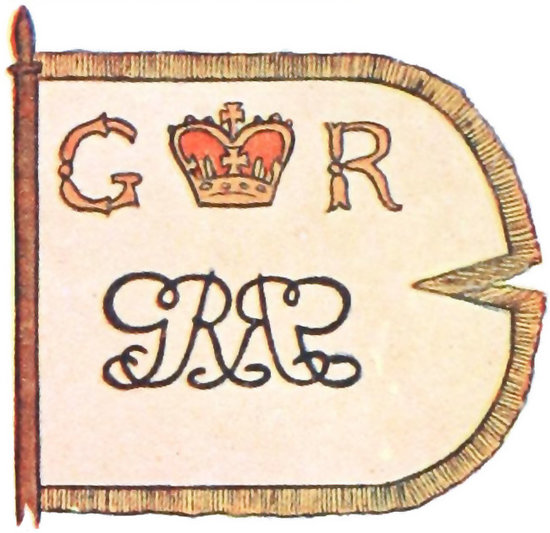

5. General Grove’s Regiment (10th Foot), 1726.

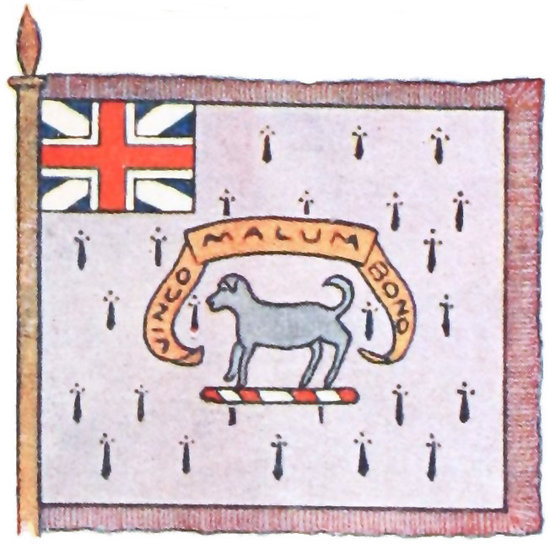

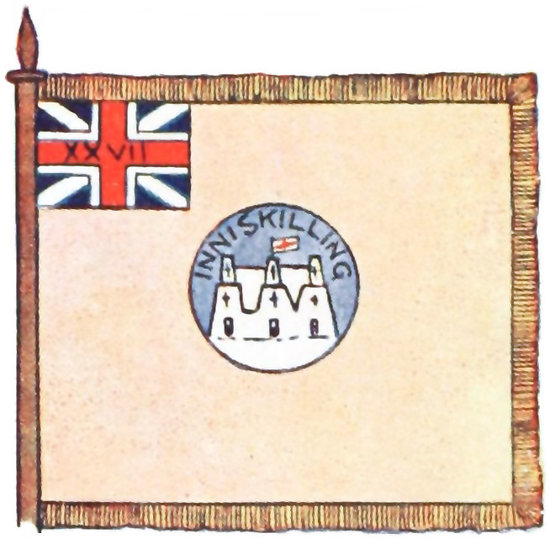

6. 27th Inniskilling Regiment, 1747.

7. 103rd Regiment, 1780.

8. 14th Regiment (Second Battalion), 1812.

Title: The Flags of Our Fighting Army

Author: Stanley C. Johnson

Release date: March 24, 2018 [eBook #56830]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Very little has been written in the past dealing with the subject of the standards, guidons, colours, etc., of the British Army. Scattered amongst Regimental histories, biographies of illustrious soldiers, and military periodicals, a fair amount of information may be discovered, but it is, of necessity, disjointed and difficult of viewing in proper perspective. Many years ago, a capital book was written by the late Mr. S. M. Milne, entitled “Standards and Colours of the British Army.” Unfortunately, this work was published privately and, accordingly, did not receive the full measure of appreciation which it merited.

Students of Army Flags should consult this book whenever possible; also “Ranks and Badges of the Army and Navy,” by Mr. O. L. Perry; and the articles which appeared in The Regiment during the latter weeks of 1916. Messrs. Gale & Polden’s folders dealing with Army Flags are also instructive.

The author wishes to acknowledge his indebtedness to Mr. Milne, Mr. O. L. Perry, and the Editor of The Regiment. He is also very grateful for the assistance extended to him by Lieutenant J. Harold Watkins and Lieutenant C. H. Hastings, Officers in charge of the Canadian War Records.

| Chapter | Page | |

|---|---|---|

| I.— | Introduction | 1 |

| II.— | A History of Military Colours | 6 |

| III.— | Standards, Guidons and Drum Banners of the Household Cavalry, Dragoon Guards and Cavalry of the Line | 36 |

| IV.— | Yeomanry Guidons and Drum Banners | 47 |

| V.— | The Colours of the Foot Guards | 54 |

| VI.— | The Colours of the Infantry | 64 |

| VII.— | Colours of Our Overseas Dominions | 115 |

| VIII.— | Miscellaneous Colours | 121 |

| IX.— | Battle Honours | 124 |

| Appendix.— | Regimental Colours of Canadian Infantry Battalions | 139 |

| Index | 147 |

| 1.—Early Regimental Colours and Standards | Frontispiece. |

| Facing page | |

| 2.—Cavalry Standards, Guidons and Drum Banners | 36 |

| 3.—Colours of the Foot Guards | 54 |

| 4.—Saving the Colours of the Buffs at Albuhera | 68 |

| 5.—Colours of the Infantry of the Line (Regular Battalions) | 80 |

| 6.—Regimental Colours of the Territorial Force | 98 |

| 7.—Colour Party of the 15th Sikhs | 116 |

| 8.—Miscellaneous Guidons and Colours | 122 |

Ever since the time when the Romans went into battle, inspired by the vexillum or labarum, military flags or colours have commanded a respect bordering almost on the sacred. Our own history is crowded with incidents which go to prove this contention. Who is there, for instance, who has not heard of the gallant deeds of Melvill and Coghill, two heroes who lost their lives in an endeavour to preserve the Queen’s colour after the disastrous Zulu encounter at Isandlwana? Or let us take the case of Lieutenant Anstruther, a youngster of eighteen, in the Welsh Fusiliers. In defending the colour he carried up the treacherous heights of the Alma, a shot laid him low, and eager hands snatched up the 2emblem without a moment’s hesitation lest it should fall into the possession of the enemy. No one thought of the danger which might overtake them whilst guarding the cherished but conspicuous banner; all were resolved to perish rather than it should be wrested from their grasp. And, let it be said, five men won the Victoria Cross that day at the Alma for their gallant defence of the colours. At the battle of Albuhera, in 1811, a colour of the 3rd Buffs was carried by Ensign Thomas. The French attacked in great force, and, surrounding Thomas, called upon him to give up the silken banner. Thomas’s answer was discourteous, but to the point; a moment later he lay dead, and the French bore away the flag with triumph. To the credit of the Buffs, we must add that the emblem was back in their possession before nightfall. These are just a few cases in which men have been ready, and even eager, to make the great sacrifice rather than lose their colours. They could be readily multiplied a hundredfold.

Fortunately, we have now reached an age when valuable lives can be no longer spent in defending military flags against the onslaughts of enemy rivals, for, to-day, there is a rule in our army regulations which forbids the taking of colours into the field of action. Before setting out to meet the foe, they are placed in safe keeping, and the rites which attend this ceremony partake of the utmost solemnity.

If military flags, which comprise the standards, guidons and drum banners of the cavalry, and also the colours of the infantry, have been reverenced in war, they are equally respected in peace time. They may never be sent from place to place without a properly constituted escort, which “will 3pay them the customary honours,” and an army regulation says that “standards, guidons, and colours when uncased are, at all times, to be saluted with the highest honours, viz., arms presented, trumpets or bugles sounding the salute, drums beating a ruffle.” When new colours are taken into service their reception is impressively conducted, and the old ones are trooped before being cased and taken to the rear.

The following miscellaneous instructions are given in the King’s Regulations with respect to military flags in general:—

“Standards and guidons of cavalry will be carried by squadron serjeant-majors. Colours of infantry will be carried by two senior second-lieutenants, but on the line of march all subaltern officers will carry them in turn.

“Standards, guidons and colours are not to be altered without the King’s special permission signified through the Army Council.

“The consecration of colours will be performed by chaplains to the forces, acting chaplains, or officiating clergymen in accordance with an authorised Form of Prayer.

“The standard of cavalry, or the King’s colour of battalions of infantry, is not to be carried by any guard or trooped, except in the case of a guard mounted over the King, the Queen, and Queen Mother, or any member of the Royal Family, or over a Viceroy, and is only to be used at guard mounting, or other ceremonials, when a member of the Royal Family or a Viceroy is present, and on occasions when the National Anthem is appointed 4to be played; at all other times it is to remain with the regiment. The King’s colour will be lowered to the King, the Queen, the Queen Mother, and members of the Royal Family, the Crown, and Viceroys only.”

Special regulations apply to the Brigade of Guards, as follows:—

“The colours of the brigade will be lowered to His Majesty the King, Her Majesty the Queen, the Queen Mother, members of the Royal Family, the Crown, Foreign Crowned Heads, Presidents of Republican States, and members of Foreign Royal Families.

“The King’s colour is never to be carried by any guard except that which mounts upon the person of His Majesty the King, or Her Majesty the Queen, or the Queen Mother.

“The regimental colours will only be lowered to a field marshal, who is not a member of the Royal Family, when he is colonel of the regiment to which the colour belongs.

“A battalion with uncased colours meeting the King’s Life Guards or King’s Guard, will pass on with sloped arms, paying the compliment ‘eyes right’ or ‘eyes left’ as required.

“A battalion with cased colours or without colours, or a detachment, guard, or relief, meeting the King’s Life Guard or the King’s Guard with uncased standard or colour, will be ordered to halt, turn in the required direction, and present arms; but will pass on with sloped arms, paying the compliment of ‘eyes right’ or ‘eyes left’ as required, if the standard or 5colour of the King’s Life Guard or King’s Guard is cased.”

Two regulations which affect the whole of the Army may well be given in conclusion:—

“Officers or soldiers passing troops with uncased colours will salute the colours and the C.O. (if senior).

“Officers, soldiers, and colours, passing a military funeral, will salute the body.”

In the period 1633-1680, the first five infantry regiments, as we know them to-day, were established, and this may be taken as a convenient point from which to begin a study of the standards and colours of our Army. Before this time the military forces of England and Scotland went into battle with a full array of waving emblems, decorated with rampant lions, powdered leopards, spread eagles, and other gaudily-painted devices, but these were usually the symbols of the knights and patrons who raised the forces. Such flags possessed much heraldic or archæological interest, but few claims on the student of military lore, and may be thus set aside with the reminder that, if knowledge of them is required, it may be gained from such sources as the roll of Karlaverok.

The first real military flags of which we have definite records were those used in the Civil Wars. The cavalry possessed standards revealing all manner of decorative symbols with mottoes telling of their leader’s faith in God, their hatred for the enemy, and the trust which they placed in Providence. The infantry forces bore colours devised with more regularity of purpose. Each colonel flew a plain white, red or other coloured flag; lieutenant-colonels were known by a flag bearing a small 7St. George’s Cross in the upper left-hand canton; whilst other officers possessed flags similar to those of the lieutenant-colonels but bearing one, two, three, or more additional devices, according to rank, such devices being lozenges, pile-wavys (i.e., tongues of flame), talbots, etc., usually placed close up to the head of the staff.

At this period Scottish forces favoured flags bearing a large St. Andrew’s Cross, in the upper triangle of which a Roman numeral was placed to denote the owner’s rank.

In 1661, under the date of February 13th, what was probably the first royal warrant to control regimental colours, was issued by the Earl of Sandwich, Master of the Great Wardrobe. It ran:

“Our Will and pleasure is, and we do hereby require you forthwith to cause to be made and provided, twelve colours or ensigns for our Regiment of Foot Guards, of white and red taffeta, of the usual largeness, with stands, heads, and tassels, each of which to have such distinctions of some of our Royal Badges, painted in oil, as our trusty and well-beloved servant, Sir Edward Walker, Knight, Garter Principal King-at-Arms, shall direct.”

This warrant is of much interest; it tells us that the early standards were painted and not embroidered; that they were made of white or red material—white was a sign of superiority, whilst red pointed to extravagance, as it was more costly than blue, yellow, etc.; and it told us that the Guards were to display the Royal badges, which they do to this day. (All these badges are dealt with in a separate chapter.)

8In later years, the small St. George’s Cross which, as we said above, figured in the upper corner of the flag, gained more prominence and filled the whole of the fabric. This may be considered the second period in the history of regimental colours. The reader will readily see that this change in English flags was brought about by contact with the Scottish regiments which had flown for many years previously their colours bearing large crosses of St. Andrew.

An interesting flag of this period is that of the Coldstream Regiment (date about 1680). A drawing of it may be seen in the Royal Library at Windsor Castle. The groundwork of blue taffeta is quite plain for the colonel. The lieutenant-colonel’s banner is blue, with a large St. George’s Cross, edged with white; whilst the major flew a similar banner, to which was added a white pile-wavy issuing from the top left-hand corner. The captains’ banners are like that of the major, but bear a distinguishing Roman numeral to show seniority of rank.

In piecing together the history of the early Army flags, a certain Nathan Brooks has given us much valuable assistance. He went to Putney Heath on October 1st, 1684, to see the King review the troops, and was wise enough to write down a description of the colours which figured in the function. Probably no better account of the flags of this period is still available. Here it is:—[1]

“The King’s Own Troop of Horse Guards and Troop of Grenadiers.—The standard, crimson with the royal cypher and crown; the guidon, differenced only from the standard by being rounded and slit at the ends.

9“The Queen’s Troop of His Majesty’s Horse Guards and Troop of Grenadiers.—The standard and guidon as the King’s.

“The Duke’s Troop of His Majesty’s Horse Guards and Troop of Grenadiers.—The standard and guidon of yellow damask, with His Royal Highness’s cypher and coronet.

“The Regiment of the Horse Guards (now the Royal Horse Guards, the Blues), eight troops.—The standard of the King’s troop, crimson, with the imperial crown, embroidered; the colonel’s colour flies the royal cypher on crimson; the major’s, gold streams on crimson; the first troop, the rose crowned; the second, a thistle crowned; the third, the flower de luce, crowned; the fourth, the harp and crown; the fifth, the royal oak; all embroidered upon the crimson colours.

“The King’s Own Royal Regiment of Dragoons, commanded by John, Lord Churchill.—The colours to each troop thus distinguished: the colonel’s, the royal cypher and crown embroidered upon crimson; the lieutenant-colonel’s, the rays of the sun, proper, crowned, issuing out of a cloud, proper, and is a badge of the Black Prince’s. The first troop has, for colours, the top of a beacon, crowned or, with flames of fire proper, and is a badge of Henry V. The second troop, two ostrich’s feathers crowned argent, a badge of Henry VI. The third, a rose and pomegranate impaled, leaves and stalk vert, a badge of Henry VIII. Fourth troop, a phœnix in flames, proper, a badge of Queen Elizabeth; each embroidered upon crimson.

10“First Regiment of Foot Guards (of twenty-four companies).—The King’s company, standard all crimson, cypher and crown embroidered in gold; the colonel’s white with the red cross (St. George’s), the crown or: the lieutenant-colonel’s, the same cross, with C.R. crowned or: the major’s, C.R. and crown, with a blaze crimson (i.e., a flame issuing from the top left-hand corner of the flag); the first company, with the King’s crest, which is a lion passant guardant crowned or, standing on a crown. (Brooks then gives the remaining company badges which are set out in full later.)

“Colestream or Cauldstream Regiment of Foot Guards.—This regiment flyes the St. George’s Cross, bordered with white in a blew field (cf. above).

“The Royal Regiment of Foot, commanded by the Earl of Dumbarton, flyes a St. Andrew’s Cross, with a thistle and crown circumscribed in the centre, ‘Nemo me impune lacessit.’

“The Queen’s Regiment of Foot, commanded by the Hon. Piercy Kirk, flyes a red cross bordered with white and rays as the admirals (see below), in a green field, with Her Majesty’s royal cypher in the centre.

“The Duke of Albany’s Maritime Regiment of Foot.—The Admiral flyes the red cross, with rays of the sun issuing from each angle of the cross, or.

“The Holland Regiment of Foot (afterwards the 3rd Buffs) flyes the red cross bordered white in a green field.

“Her Royal Highness, the Duchess of York and Albany’s Regiment of Foot (4th King’s Own) flies a 11red cross in a yellow field, bordered white, with rays, as that of the Admiral’s, with H.R.Highness’s cypher in the centre.”

Having completed the quotation from Brooks, we are able to give an extract from an old M.S., which is interesting when read in conjunction with the above descriptions of Army flags:—

“The imbroidered cypher and crowne on both sides Ye King’s owne colours, £3 . 10 . 0.

“For painting and guilding ye other 23 colours and crownes on both sides one with another at 15s. a side, £34 . 10 . 0.”

Clearly this extract refers to the First Regiment of Foot Guards, and shows that the King’s colours were embroidered, whilst the Company colours were merely painted. Before this time, we know that most flags were painted and, afterwards, that the tendency was for them to be embroidered. It seems fair, then, to infer from this that when the King reviewed his troops at Putney Heath, the period was one of transition from painted to embroidered decoration.

Passing on to the reign of King James II., it seems that he evolved many changes which were but little appreciated in the military quarters in those days. An authority of the time, named Sandford, who wrote a book entitled, “A History of the Coronation,” describes some of the Army flags as follows:—

“1st or King’s Guards.—The standard of the King’s Own Company was of crimson silk, embroidered in the centre with the royal cypher, J.R., ensigned with 12(i.e., having above it) an imperial crown in gold. The colonel’s, also of crimson silk, was not charged with any distinction or device. The lieutenant-colonel’s colour was of white silk with the cross of St. George throughout (i.e., covering the flag) of crimson silk, in the middle of which was painted an imperial crown in gold. The major’s colour was distinguished by a pile-wavy of crimson silk issuing out of the dexter chief of the first quarter (i.e., the corner of the flag nearest to the top of the staff), and an imperial crown of gold in the centre of the cross. The eldest captain’s colour was distinguished by one of the King’s cyphers, viz., J.R., interlaced, and an imperial crown painted in the middle of the cross, of gold; the second captain was differenced by two royal cyphers and crowns in the cross; the third, by three; the fourth, by four; and so on every captain to the twentieth who had his cross charged with twenty cyphers and crowns. And thus they appeared at James’s coronation.

“Coldstream Guards.—His Majesty did then also direct that the alterations following should be made in the ensigns of this his second regiment of Foot Guards, that they might be more agreeable to the colours of the first regiment; for, excepting the colonel’s ensign, which was purely of white taffeta, the other eleven were charged with crosses of crimson taffeta throughout. The lieutenant-colonel’s, without distinction. The major’s had a pile-wavy. The cross of the eldest captain was charged on the centre with the figure I. in white, ensigned with an imperial crown of gold painted thereon; the second with II., the third with III., the fourth, IV., 13and so forward to the ninth captain who was distinguished by IX., each of them under an imperial crown of gold. And thus did these ensigns fly at the coronation.”

With the help of Sandford’s description, and a series of coloured plates, which may be seen in the library at Windsor, we are able to get a very correct impression of the Army colours of this period. Generally speaking, they were remarkable for their brilliant colouring, their fanciful fabric, their lack of similarity one with another, and their show of private as opposed to royal badges. In this latter connection, the colours of James showed a clear harking back to the pre-Reformation days. Our first figure, on Plate I., reveals an attractive colour of the period; it represents the standard of the Second Troop of Horse Guards, date about 1687. The angels which support the large central crown were taken from a popular French device, whilst the three small crowns placed near the lower edge, refer to the King’s claim to the crowns of England, Ireland and France. The central cypher, it may be well to point out, is not F.R. but J.R. The second illustration reveals the Earl of Shrewsbury’s rampant lion on a yellow field. There is a difference of opinion as to whether the background should not be lightish buff, but the Windsor plates certainly favour the colour as given in Fig. 2. The flag is the colonel’s standard of Shrewsbury’s Regiment of Horse (now the 5th Dragoon Guards).

We have hinted that this was an era of much decoration, but to this rule there is one outstanding exception—we refer to the Scots Guards. In this case, the colonel’s colour was plain white, a favourite flag of 14earlier times. The lieutenant-colonel’s was the national flag of Scotland, a white St. Andrew’s Cross on a blue field. The major’s was the same, but with a pile-wavy issuing from the upper corner of the cross, and the captain’s as the lieutenant-colonel’s, but with a silver numeral placed on the uppermost blue triangle. All were provided with silver and blue tassels, and a silver spear surmounted the pole, emblems which served to distinguish the flags of the Scots Guards from the national flags which were current at that time.

From the end of the reign of James II. to 1707, when England and Scotland formed a legislative union, we can trace but little in the progress of military colours. The Union, however, came and left a very clear impress on the banners of the time. Wherever the red cross of St. George had been used, it was modified with the white cross of St. Andrew, together with its distinctive blue triangular fields. As a rule, the authorities favoured the use of small crosses, placed in the upper canton, rather than large ones covering the whole fabric, for this enabled a fairly big portion of the flag to be used for displaying the arms of each particular military unit. A typical example of this period is shown in Fig. 5. Here we have the colonel’s colour of General Grove’s Regiment, afterwards the 10th Foot (now the Lincolnshire Regiment). The talbot, the motto, and the ermine representations were all features in the crest borne by General Grove. The date of this flag is 1726. Fig. 6, which shows the colours of the 27th or Inniskilling Regiment, is also typical. Its date may be put down at about 1747.

15The union did not appear on the infantry colours alone, during this period; it also figured, but to a lesser extent, in the cavalry standards, as may be noted from the following interesting quotation from Milne.[2]

“Very little is known about cavalry standards from the time of James II. until the middle of the next century; no drawings or evidence of any kind seem forthcoming. One solitary specimen has been preserved, however, and that of great interest, namely, the Dettingen standard of the old 8th, subsequently 4th Horse (afterwards 7th Dragoon Guards).

“A record of this regiment gives a very full and detailed account of its bravery at Dettingen, under the command of its well-known colonel, Major-General John Ligonier, who was created a knight-banneret on the field of battle by the King (George II.) in person, and further proceeds to relate that Cornet Richardson, carrying a standard, was surrounded by the enemy and, refusing to surrender, received upwards of thirty sabre cuts in his body and through his clothes. His standard and standard lance were also damaged but he brought his precious charge out of action.

“During the winter the standards, so much damaged in the battle as to be unfit for use, were replaced by new ones from England, and each cornet was presented with the one he had carried, as a testimony to his good conduct. That presented to Cornet Richardson is still carefully preserved by his descendant and representative.

“It is made of crimson silk brocade, about twenty-four inches square, edged with gold and silver fringe, with a 16small union, three inches square, in the upper corner; one side, the obverse, presents the crest and motto of the colonel, General Ligonier (a demi lion issuing out of a ducal coronet) with his motto, “Quo fata vocant,” on a scroll above; the reverse gives his full coat of arms, crest, shield and motto, surrounded with a handsome trophy of standards, trumpets, and implements of war, all finely worked in gold embroidery.”

The feature of providing each side of the standard with a different pattern, mentioned above, was unusual.

So far we have seen that with but one or two exceptions, no restrictions were put upon the regimental authorities in designing their own colours. Each unit was free to select its devices at will, and choose whatever colouring seemed to fit its banners most. In 1743, however, a Royal Warrant was issued which checked this freedom of design. It ran:—

“The Union colour is the first stand of colours in all regiments, royal or not, except the Foot Guards. With them the King’s Standard is the first as a particular distinction.

“No colonel to put his arms, crest, device, or livery in any part of the appointments of his regiment.

“The first colour of every marching regiment of foot is to be the great Union; the second colour is to be the colour of the facing of the regiment, with the Union in the upper canton; except those regiments faced with white or red, whose second colour is to be the Red Cross of St. George, in a white field and a Union in the upper canton. In the centre of each colour is to be painted, in gold Roman figures, the number of the rank of the 17regiments, within a wreath of roses and thistles on one stalk, except those regiments which are allowed to wear royal devices or antient badges; the number of their rank is to be painted towards the upper corner. The length of the pike and colours to be the same size as those of the Foot Guards; the cord and tassels of all colours to be crimson and gold.

“All the Royal Regiments, the Fusilier and the Marine Regiments, the Old Buffs, the 5th and 6th Regiments, the 8th or King’s Regiment, and the 27th or Inniskilling Regiment are distinguished by particular devices, and therefore, not subject to the preceding articles for colours.

“The Standards and Guidons of the Dragoon Guards, and the Standards of the Regimental Horse, to be of Damask, embroidered and fringed with Gold or Silver. The Guidons of the Regiments of Dragoons to be of Silk. The Tassels and Cords of the whole to be of Crimson Silk and Gold mixed. The size of the Guidons and Standards, and the length of the Lance to be the same as those of the Horse and Horse Grenadier Guards.

“The King’s or first Standard and Guidon of each Regiment to be Crimson, with the Rose and Thistle, conjoined, and Crown over them, in the Centre: His Majesty’s Motto, ‘Dieu et mon Droit,’ underneath. The White Horse in a Compartment in the first and fourth corners; and the Rank of the Regiment in Gold or Silver Characters on a Ground of the same Colour as the Facing of the Regiment in a Compartment in the second and third Corners.

“The second and third Standard and Guidon of each Corps to be of the Colour of the Facing of the Regiment, 18with the Badge of the Regiment in the centre, or the Rank of the Regiment in Gold or Silver Roman characters, on a crimson ground, within a Wreath of Roses and Thistles on the same stalk, the Motto of the Regiment underneath. The White Horse, on a red ground to be in the first and fourth Compartments; and the Rose and Thistle conjoined upon a red Ground in the second and third Compartments. The distinction of the third Standard or Guidon to be a figure 3 on a circular ground of Red underneath the Motto. Those Corps which have any particular badge are to carry it in the centre of their second and third Standard or Guidon, with the Rank of the Regiment on a red ground within a small Wreath of Roses and Thistles in the second and third corner.”

This warrant is remarkable from the fact that it swept aside many customs which had taken years, even centuries in some cases, to mature, and instituted new ones which, with slight modifications, have remained till to-day. The details set out for the Dragoon Guards are particularly elaborate, so much so that few people seem to know just what to make of them. Milne says that the Dragoon regulations did not come into use very rapidly because they were not understood. To support this contention, he quotes the following Annual Inspection Returns. “1st Dragoon Guards. Shrewsbury, November 5th, 1750. The inspecting officer reports Standards received in 1740, and in bad condition, the regiment waiting for a pattern from His Royal Highness the Duke.” Again, 6th Dragoons. Ipswich, November 22nd, 1750: “Waiting for a pattern from His Royal Highness the Duke.” Evidently, says Milne, it was 19found difficult to work from the printed details, and there appears to have been delay in settling the precise form the numerous badges should take until the commander-in-chief had sanctioned a pattern standard. When the patterns were decided upon they were practically identical to those in use to-day, and far more elaborate than those they displaced, as a reference to Figs. 3 and 4 will show. In these figures, two forms of the standard of the 2nd Dragoon Guards of 1742 are given.

The 1743 warrant gave rise to much uncertainty, even outside the section which referred to the Dragoon Guards, and, consequently, it is not surprising to find that many official orders and “letters” were issued giving advice and information telling how the various regulations were to be carried out. One such document determined the measurements of the Army Union flag, which were, of course, not those of the national Union flag. The horizontal edge was given as 6 ft. 6 ins., the vertical edge, 6 ft. 2 ins.; the width of the St. George’s Cross, 1 ft. 1 in.; the width of the white edging to the St. George’s Cross, 5 ins.; the width of the St. Andrew’s Cross, 9 ins. (The diagonal red cross of St. Patrick did not then form part of the Union). Also, the length of the pike was 9 ft. 10 ins.; the length of the cords with tassels, 3 ft.; each tassel was 4 ins.; and the length of the spear-head of the pike, 4 ins.

The idea of controlling the regimental colours by the higher authorities seems to have found favour and, as a result, further regulations were issued in a supplementary warrant in 1747.[3] Colonel Napier, who was responsible 20for this document, decided upon the following particulars:—

First Regiment or the Royal Regiment.—In the centre of all their colours, the King’s Cipher[4] within the circle of St. Andrew and Crown over it; in the three corners of the second colour (i.e., the regimental colour), the Thistle and Crown. The distinction of the colours of the 2nd battalion is a flaming ray of gold descending from the upper corner of each colour towards the centre.

Second or the Queen’s Royal Regiment.—In the centre of each colour, the Queen’s Cipher, on a red ground, within the Garter and Crown over it; in the three corners of the second colour the Lamb, being the ancient badge of the regiment.

Third Regiment or the Buffs.—In the centre of both their colours, the Dragon, being their ancient badge, and the Rose and Crown in the three corners of their second colour.

Fourth, or the King’s Own Royal Regiment.—In the centre of both their colours, the King’s Cipher on a red ground, within the Garter, and Crown over it; in the three corners of their second colour the Lion of England, being their ancient badge.

Fifth Regiment.—In the centre of their two colours, St. George killing the Dragon, being their ancient badge, and in the three corners of their two colours, the Rose and Crown.

Sixth Regiment.—In the centre of their two colours, 21the Antelope, being their ancient badge, and in the three corners of their second colour, the Rose and Crown.

Seventh, or the Royal Fusiliers.—In the centre of their two colours, the Rose within the Garter and the Crown over it; the White Horse in the corners of the second colour.

Eighth, or the King’s Regiment.—In the centre of both their colours, the White Horse on a red ground, within the Garter and Crown over it; in the three corners of the second colour the King’s Cipher and Crown.

Eighteenth Regiment or the Royal Irish.—In the centre of both their colours, the Harp in a blue field, and the Crown over it, and in the three corners of their second colour, the Lion of Nassau—King William the Third’s arms.

Twenty-first, or the Royal North British Fusiliers.—In the centre of their colours, the Thistle within the circle of St. Andrew and Crown over it, and in the three corners of the second colour, the King’s Cipher and Crown.

Twenty-third, or the Royal Welsh Fusiliers.—In the centre of their colours, the device of the Prince of Wales, viz., three feathers issuing out of the Prince’s coronet; in the three corners of the second colour, the badges of Edward the Black Prince, viz., a Rising Sun, a Red Dragon, and the Three Feathers in the coronet; motto, “Ich Dien.”

Twenty-seventh, or the Inniskilling Regiment.—Allowed to wear in the centre of their colours a Castle 22with three turrets, from the middle one of which flies a St. George’s Cross, all on a blue field, and the name ‘Inniskilling’ above. (See Fig. 6).

Forty-first Regiment, or the Invalids.—In the centre of their colours, the Rose and Thistle, on a red ground, within the Garter; a Crown above. In the three corners of the second colour, the King’s Cipher and Crown.

Of the period beginning with the year 1751, Milne writes as follows:[5] “An entirely new era is now being entered upon; a complete break has taken place in the continuity of the colours of the British infantry; the colonel’s and lieutenant-colonel’s flags have disappeared[6], together with their gaudy and ever varying private armorial devices, distinctive perhaps to the educated, but to the unlettered rank and file emblematical of but little.

“In their place, boldly and resolutely stands the regimental number, simple in form, easily recognised, easily remembered, forming a rallying point in the minds of soldiers, which, as decade after decade passed away, became indissolubly connected with some glorious deed, in its turn becoming a matter of history, adding lustre to the regimental number, and so, gradually, but surely, building up that wonderful esprit de corps which has stood the nation in good stead on so many occasions.

“Extremely plain at first, only the number within its flowery surroundings, the flowers will be observed to 23become more ornate; tokens of honour, the remembrance of some gallant action or campaign, added from time to time, and ultimately the names of victories duly and discreetly authorised to be emblazoned: and all surrounding and centreing upon the old regimental number, ever enhancing its value in the eyes of those who had the honour of serving under it.”

The American War of Independence, as the reader may justly suppose, marks another period in the history of military flags. In those days it was customary, though not the immutable rule, to carry these emblems into the line of battle, and as this period of fighting brought us many reverses the effect on the colours was often disastrous. Many were taken by the enemy, many more were worn to shreds, and a few were hidden and lost. It is forgotten by some of us that American raiders infested our shores and sank numbers of British vessels. The toll of ships led, at times, to the loss of colours. Here is a case in point.

Report of an Inspection of the 81st Aberdeenshire Highlanders, at Kinsale. “Colours wanting; were taken on passage from England to Ireland by an American privateer. A new stand making in Dublin.”

As a result of all these happenings, many regiments will be found to have had new colours at some time during the period 1776-83.

Continuing our history, we find that the next step to note concerns the placing of battle honours on military flags. The first of these distinctions was “Emsdorf,” and was given to the 15th Light Dragoons in 1768. Ten 24years later, the second distinction, “Gibraltar,” was awarded to a quartette of regiments. It was the King’s appreciation of the forces which withstood the fierce siege with “red-hot potatoes” under the command of General Eliot, afterwards Lord Heathfield. The official intimation of this grant is worth quoting in extenso.

“April 28th, 1784. I seize the opportunity to acquaint you further that His Majesty has been graciously pleased in commemoration of the glorious defence made by those regiments which comprised the garrison of Gibraltar during the late memorable siege of that important fortress to permit the 12th, 39th, 56th, 58th Regiments which made a part of it, to have the word ‘Gibraltar’ placed upon their grenadier and light infantry caps, their accoutrements and drums, as likewise upon the second colour of each of those regiments, just underneath their respective numbers.

It will be noticed that the distinction was to be fixed to the second or regimental colour, and not to that of the King’s—a rule which holds till this day, with but a few exceptions.

The Act of Union, which linked together the parliaments of England and Ireland in 1801, had a considerable but obvious influence on the objects of this study. Hardly was there a flag in the whole of the Army which did not become obsolete by this union. Many of them were retired, and fresh ones provided, but the general plan was to modify the existing specimens. This was done by sewing red strips along the white limbs of the St. 25Andrew’s Cross to provide for the St. Patrick’s Cross, and by adding shamrocks to the wreath of leaves and flowers which encircled the regimental badge. Milne says that the intrusion of the shamrock was in all cases manifest, so that examples of this date may be recognised with ease.

It is worth mentioning that colours are often modified or altered to keep abreast with changing circumstances; new ones are not always provided the moment they become obsolete in one or more small particulars. The same writer from whom we just quoted describes the changes which the standard of the Coldstream Guards underwent during a period of some sixteen years. “When originally made, ... the central garter star (i.e., the regimental badge) and the wreath richly embroidered in gold bullion, but without the shamrock, and possibly the crown, were all that appeared on the plain crimson silk ground. The union with Ireland, 1801, necessitated the introduction of the shamrocks ... they have been squeezed into places when scarcely room could be found for them. ‘Egypt’ and the ‘Sphinx’ having been authorised, they would probably be added at the same time, ‘Egypt’ on a blue silk label, immediately under the wreath, the ‘Sphinx’ within a laurel wreath of gold embroidery, in all the four corners. The standard continued in this state until 1814, when the honours, ‘Lincelles, Talavera, Barrosa,’ were authorised to be used by the regiment. Consequently, they were added in gold twist letters, on the crimson ground. Two more honours, ‘Peninsula and Waterloo,’ were further authorised in 1815-16, and added soon after on crimson silk (some trouble must have been occasioned 26in fitting the two last into their places, so little room being left).”[7]

As time made the warrants of 1743 and 1747 more and more antiquated, we find that regimental commanders took ever increasing liberties with the regulations set down in those documents. To check such departures, a Mr. George Naylor, the then York Herald, an appointment in the College of Arms, was given the post of inspector of regimental colours in the year 1806. One of Mr. Naylor’s first actions was to issue a leaflet, which he sent to every commanding officer, setting out certain rules of paramount importance. The leaflet also gave a representation of both the King’s and regimental colours, showing a blank central cartouche. This, he intimated, was the standard pattern, and each commanding officer was requested to fill in the details which were particular to his own flags and return them for purposes of filing. The designs which came back to Mr. Naylor clearly pointed to the lack of uniformity which had sprung up in the preparation of colours. Many flags had been worked by ladies of title who were patrons of the local unit, the daughters of the commanding officers, and other such people, whose qualifications to embroider were greater than their understanding of heraldry. To Mr. Naylor, who knew what each flag should have borne, the designs must frankly have been disappointing. In some cases, the Egyptian Sphinx faced right instead of 27left; in others, it filled the space reserved for the central badge; one instance is known where this device was used as an ornament to cap the staff, and so heavily was it cast in silver that those who carried it were “under the necessity of unscrewing it when the regiment began to move”; a laurel wreath instead of the union wreath was another substituted design. One of the filled-in designs returned to the College of Arms showed a very dilapidated flag, but the covering letter explained that, “the George and Dragon has nearly disappeared from our King’s colour by a shell passing through it, though I trust his spirit is left amongst us.”

The period following on the peace which came with the victory of Waterloo proved of great activity in the world of military colours. The old flags had seen much active service and had become worn and torn, some had been stripped from their supports in a moment of crisis and hidden, whilst a few fell from the hands of their possessors and became lost. Also, we must not forget that many new battle honours had been recently won, and the fixing of these distinctions would always be an unwise action when the flags were showing signs of wear. Accordingly, the regiments which were provided with new stands at this time were considerable.

The post-Waterloo period was marked by the disappearance of the central heart-shaped shield (Figs. 7 and 8) in favour of a circle of red silk, which was divided into a ring and an inner circle, the first for taking the territorial designation of the regiment, and the second for showing the regimental badge or number. (It should, perhaps, be stated that royal regiments and those with higher 28numbers than seventy seldom possessed territorial designations at this time.) The central circle and ring of crimson have remained until this day. Roman gave place to Arabic numerals, but the latter have since died out; the wreath became a little more elaborate, for buds and extra leaves were introduced, and the sphinx was definitely placed below the chief badge. A word must be said respecting the battle honours; these were fixed in almost any position and combination and no rules were followed, partly because the number of honours varied with each regiment and partly because few regiments possessed sufficient to work up into a universal pattern. Not many of the banners of this time were painted, but, of course, the Foot Guards formed a notable exception. When a line regiment flew a painted flag, it was somewhat despised, and the inspection report was worded in a condemning spirit. Here is an example: “Colours only three years in use, much injured from the circumstance of the arms and ornaments being painted.”

Another era of laxity sprang up about 1830. Colours issued at this time displayed many departures from the general rules. Arabic numerals once more found favour for denoting the regimental numbers, county titles were often missing, the wreath became more fanciful, and in one case, the Northumberland Fusiliers, the badge of St. George and the Dragon was encircled by the union wreath, the central crimson circle being entirely missing. Honours were commonly inscribed on the King’s colours, which was decidedly wrong.

The swing of the pendulum came in 1844, for in that year an order issued from the Horse Guards decreed 29that battle honours were not to figure on the King’s or Queen’s colours, nothing was to be placed on them beyond the regimental designation and the imperial crown. This decision, which did not apply to the Foot Guards, as they have always been a law unto themselves, was lamented by many people, as it robbed these colours of much of their splendour. Milne thinks that the edict was issued because battle honours were fast growing in number, and if many of these were sewn on to a jack which was already a combination of seams and stitches the results would be disastrous in partly worn specimens.

At this point we must go back to the years which followed Waterloo, to discuss the standards of the Cavalry. The Hussar regiments had discarded them completely, and most, if not all, of the Lancers had done the same. No Hussars or Lancers possess them to-day, but, of course, their drum banners serve to display their arms and appointments.

The shape of these flags received attention at this time. The Life Guards and Horse Guards continued to fly square standards (there was an exception in the case of The Blues, of which mention is made later). The Dragoon Guards had favoured guidons from the date of their inception in 1746, but were ordered to carry square standards in 1837. The Dragoons continued to use the guidon-shaped banner which they selected in the days of the Stuarts, and which they still carry. The Light Dragoons only possessed banners, which were guidons, in three instances.

30A King’s regulation, dated June 1st, 1837, decreed that:—

The Standards of the Dragoon Guards were “to be of silk damask embroidered and fringed with gold. The guidons of the regiments of Dragoons to be of silk. The flag of the standard to be 2 ft. 5 ins. wide without the fringe, and 2 ft. 3 ins. on the lance. The flag of the guidon of Dragoons to be 3 ft. 5 ins. to the end of the slit in the tail, and 2 ft. 3 ins. on the lance; the first or royal standard to be crimson, and the others of the colour of the facings as before.” These latter were of a curious oblong shape, with straight edges to the portions cut away in the fly.

Another official decree, dated August 18th, 1858, ran as follows:—

“Her Majesty has been pleased to approve that regiments of Dragoon Guards henceforth carry but one standard or guidon, that the second, third and fourth standards or guidons at present in use be discontinued and that the authorised badges, devices, distinctions, and mottoes be, in future, borne on what is now called the Royal or first standard or guidon in the Dragoon Guards. N.B.—This not to apply to the Household troops, who carry one standard per squadron.”

This decree is a little difficult to understand as the third and fourth standards had not been carried for many years prior to the issue of the warrant. To-day, of course, these regiments possess but a single flag, a combination of royal and regimental colour in one.

A standard which has received much prominence, and which forms an unwelcomed exception to the rule 31that the Horse Guards fly square standards (see p. 29) was presented to the Blues by William IV. in 1812, at Windsor. We quote from a newspaper cutting:—

“At 12 the King and Queen with their suite and an escort of the Third Dragoon Guards passed along the front of the line in open carriages and, having taken post in the centre, the guns fired and the troops saluted. The troops having been wheeled inwards, and the officers called to the front, Lord Hill placing himself before his regiment, their Majesties, accompanied by the Dukes of Cumberland and Gloucester, and Prince George of Cumberland, with the Duchess of Cumberland and Princess Augusta, taking their station in the centre, the standard, richly wrought in gold and emblazoned with the trophies of the Blues, was consecrated by the Chaplain to the Forces. After an address, in which the King recapitulated the motive of his gift, and the early origin and distinguished services of the Royal Horse Guards, His Majesty presented the standard to Lord Hill, who respectfully received it on the part of his regiment. The troops then resumed line, broke into column, and marched past in ordinary and quick time.”

This standard was guidon-shaped and of crimson silk; in the centre it had the cypher of William IV., forward and reversed, interlaced, surrounded by a number of battle honours, above which was the royal crown. In the four corners were crowned emblems of the rose, thistle and shamrock.

We are now drawing to the close of this historical sketch, but before turning from the subject we must 32mark the year 1855. About this time the union wreath on the colours of the infantry regiments assumed the style as we now have it; the spear-head gave way for the lion and crown which now adorns the pike-tops, whilst the cord and tassels were given a definite style which has not been altered since.

About this time, also, a regulation was issued declaring that “The regimental or second colour is to be the colour of the facing of the regiment, with the Union in the upper canton, except those regiments which are faced with red, white or black. In those regiments which are faced red or white, the second colour is to be the red cross of St. George in a white field, and the Union in the upper canton. In those regiments which are faced with black, the second colour is to be the St. George’s Cross: the Union in the upper canton, the three other cantons, black.”

A more recent regulation has been framed which, in a measure, modifies the one just quoted. We give it at length:—

“The Colours of the Infantry are to be of silk, the dimensions to be 3 ft. 9 ins. flying, and 3 ft. deep on the pike, which, including the Royal Crest, to be 8 ft. 7½ ins., the cords and tassels to be crimson and gold mixed.

“The Royal or First colour of every regiment (of infantry) is to be the Great Union, the Imperial colour of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, in which the Cross of St. George is conjoined with the crosses of St. Andrew and St. Patrick, on a blue field. The first colour is to bear in the centre the territorial designation 33on a crimson circle with the Royal or other title within the whole, surmounted by the Imperial Crown.

“The regimental or second colour is to be the colour of the facing of the regiment, except in those regiments which are faced with white, in which the second colour is to be the red cross of St. George in a white field, with the territorial designation of the Royal or other title displayed, as on the Royal or First colour, within the union-wreath of roses, thistles and shamrocks, ensigned with the Imperial crown.

“The regimental or second colour of the First and Second battalions is to bear the ancient badges, devices, distinctions, and mottoes, which have been conferred by Royal authority. The third and fourth battalions[8] are to carry the same colours without such devices and distinctions as specially refer to actions or campaigns granted in commemoration of the services of the other two battalions. The number of each battalion, I., II., III., IV., is to be placed in the dexter cantons.

“In those regiments which bear any ancient badge, the badge is to be on a red ground in the centre. The territorial designation, if practicable, to be inscribed on a circle within the union wreath of roses, thistles, and shamrocks, and the Royal or other title in an escroll underneath, the whole ensigned with the Imperial crown.

“No additions to, or alterations in colours is to be made without the Sovereign’s special permission and authority, signified through the Commander-in-Chief of the Army.

34“Application for new colours is to be made to the Director of Clothing, in accordance with the instructions laid down in the Royal Warrant relating to clothing.”

The Foot Guards, which do not come under the heading of Infantry, follow another set of regulations (see Chapter V.). Here it is of interest to mention that, at one time, the authorities did everything in their power to make them subject to the same regulations, but the Foot Guards determined otherwise. Let us quote from Sir Frederick Hamilton’s “History of the Grenadier Guards.” In September, 1859, when new colours were about to be supplied to the Second Battalion Grenadier Guards, they were given out from the Clothing Department, thus for the first time treating the issue of Royal colours with about the same respect as is accorded to the issue of a pair of regulation boots. Previous, however, to delivery, Colonel F. W. Hamilton was requested to inspect them, when he at once observed the substitution of the regimental for the Queen’s colour and vice versâ. He also heard for the first time of the proposal that the battalions should each select, ad libitum, one only of the twenty-four Royal badges then belonging to them, and retain it as their battalion badge, leaving the rest to fall into desuetude.”

As a result of this action, the Guards protested, as only Guards can, against this attempt to rob them of their traditional customs. The matter was laid before Queen Victoria, and in the month of October, 1859, she decided that “the crimson colour, as before, should be ‘the Queen’s’ colour, and that the distinguished company badges, as hitherto borne, should be retained, and 35emblazoned in rotation in the centre of the Union or regimental colour. Excepting only the reduction in size, and the addition of the proposed gold fringe, Her Majesty would wish no further change to be made in the colours as hitherto borne by Her Regiments of Guards. The service badges or names of actions in which the regiments have distinguished themselves should be borne as hitherto-fore on both colours.” This latter decree settled probably for all time the designs of the colours of the Foot Guards.

We have now followed the growth of the military colours of the British Army during the last two hundred and fifty years. In so long a period and where so many different units are concerned, each having peculiarities of its own, it is quite impossible to note every little change and variation which has occurred, but the reader may be assured that all the more important and interesting steps in the progress of these emblems of British pluck and patriotism have received due notice.

Among the grandest and most attractive flags which are flown in any part of the world, those of the British Cavalry must be assigned a high position, for, without being gaudy, they are beautiful, elaborate, gaily coloured and full of historic detail. The reader is invited to turn to the second plate, and examine the five examples given thereon. He will see that the badges—the relics of the old baronial days—are steeped in historical fact and military tradition, that the battle honours are reminiscent of the glorious fights of other days; and that the reds and blues and greens are judiciously blended without offending the eye.

Cavalry flags are known as standards when they are square and guidons when swallow-tailed. The Household Cavalry and the Dragoon Guards possess standards and the Dragoons fly guidons. To the student of military emblems, it is somewhat disappointing to find that Hussars and Lancers have no flags with which to display their splendid traditions. In their case, we must be content to examine the cloths or banners hung around their drums. Before taking each regiment separately, it may be useful to state that a standard, without the red and gold fringe, measures 2 ft. 6 ins. by 2 ft. 3 ins.; a guidon, 3 ft. 5 ins. by 2 ft. 3 ins.; and the lance of either is 8 ft. 6 ins. long.

371st Life Guards.—The King’s Standard is crimson and bears a fairly large representation of the Royal Arms. The King’s Cypher figures in the two upper corners. Below the Arms are placed the battle honours: Dettingen; Peninsula; Waterloo; Egypt, 1882; Tel-el-Kebir; South Africa, 1899-1900; Relief of Kimberley; Paardeberg.

Three other standards are carried, each very similar to the above, the central device being the chief point of difference. (See Fig. 9.)

2nd Life Guards.—As for the 1st Life Guards, with slight technical differences. (See Fig. 9.)

Royal Horse Guards (The Blues).—As for the 1st Life Guards with slight technical differences. With this regiment the battle honours are: Dettingen; Warburg; Beaumont; Willems; Peninsula; Waterloo; Egypt, 1882; Tel-el-Kebir; South Africa, 1899-1900; Relief of Kimberley; Paardeberg.

The Standard of Honour, in reality a guidon, which was presented by William IV. (described elsewhere) must be mentioned here.

1st King’s Dragoon Guards.—This standard of crimson silk damask bears in the centre the Royal Cypher within the Garter, and ensigned with the imperial crown. Around this is placed the union wreath bearing roses, 38shamrocks, and thistles growing upon the same stalk. In the four corners are placed small oval labels; the first and fourth revealing the White Horse of Hanover, on a green mount, the background of the horse is red; the second and third being devoted to the regimental initials I. K.D.G., on a blue ground. Along the vertical edges of the standard are placed a number of golden labels, each bearing one of the following battle honours: Blenheim; Ramillies; Oudenarde; Malplaquet; Dettingen; Warburg; Beaumont; Waterloo; Sevastopol; Taku Forts; Pekin; South Africa, 1879. Below the union wreath is placed a label inscribed: South Africa, 1901-02. This flag is given in Fig. 10.

The White Horse is shown in order to recall the part which this regiment took in suppressing the Jacobite Rebellions during the reigns of George I. and II.

2nd Dragoon Guards (Queen’s Bays).—This standard closely follows the design of the 1st (King’s) Dragoon Guards. The centre, however, is filled with the cypher of Queen Caroline, within the Garter. The first and fourth corners contain the White Horse, while the second and third bear the initials II. D.G., on a buff ground. The battle honours are: Warburg; Willems; Lucknow; South Africa, 1901-02.

3rd (Prince of Wales’s) Dragoon Guards.—The Dragoon Guard type of standard is followed in this case. The central badge is the Plume of the Prince of Wales. The first and fourth corners reveal the White Horse, as above; the second corner contains a small picture of the Rising Sun, and the third, a small Red Dragon. (All these three 39devices are the appropriation of the Prince of Wales.) The battle honours are: Blenheim; Ramillies; Oudenarde; Malplaquet; Warburg; Beaumont; Willems; Talavera; Albuhera; Vittoria; Peninsula; Abyssinia; South Africa, 1901-02. (Fig. 11.)

4th (Royal Irish) Dragoon Guards.—The Dragoon Guard type of standard is again followed. The central badge contains the Harp and Crown, and the Star of the Order of St. Patrick; the second and third corners are filled with the initials IV. D.G. on a blue ground, and the battle honours are: Peninsula; Balaklava; Sevastopol; Egypt, 1882; Tel-el-Kebir. The motto, “Quis separabit,” is inscribed below the union wreath.

5th (Princess Charlotte of Wales’s) Dragoon Guards.—This standard follows the type for the Dragoon Guards. The central badge is merely the regimental designation, V. D.G. The four corners contain the White Horse and the Rose, Thistle and Shamrock on one stalk. The battle honours are: Blenheim; Ramillies; Oudenarde; Malplaquet; Beaumont; Salamanca; Vittoria; Toulouse; Peninsula; Balaklava; Sevastopol; South Africa, 1899-1902; Defence of Ladysmith. The motto of John Hampden, “Vestigia nulla retrorsum” (No going backwards), appears below the union wreath.

6th Dragoon Guards (Carabiniers).—This standard follows the type for the Dragoon Guards. The central badge is VI. D.G. The second and third corners have white labels also bearing the inscription VI. D.G. The battle honours are: Blenheim; Ramillies; Oudenarde; Malplaquet; Warburg; Willems; Sevastopol; Delhi, 401857; Afghanistan, 1879-80; South Africa, 1899-1902; Relief of Kimberley; Paardeberg.

7th (Princess Royal’s) Dragoon Guards.—The type as before. In the centre, the coronet of her late Majesty, the Empress and Queen Frederick of Germany and Prussia as Princess Royal of Great Britain and Ireland. As the facings are black, the letters VII. P.R.D.G. appear on a groundwork of this colour in the second and third corners. The battle honours are: Blenheim; Ramillies; Oudenarde; Malplaquet; Dettingen; Warburg; South Africa, 1846-7; Egypt, 1882; Tel-el-Kebir; South Africa, 1900-02.

1st (Royal) Dragoons.—A guidon of crimson silk, bearing in its centre the crest of England, within the Garter, is the flag of this regiment. The imperial crown ensigns the badge and the union wreath encircles it. The four corners contain small labels, as was the case with all the Dragoon Guard standards; the first and fourth are embellished with the White Horse, and the second and third with the initials I.D. on a blue ground. Below the union wreath is the motto, “Spectemur agendo” (Judge us by our deeds), and below this is a silver eagle, a replica of the one taken from the 105th Regiment of French Infantry at Waterloo. The battle honours are: Tangier, 1662-80; Dettingen; Warburg; Beaumont; Willems; Fuentes d’Onor; Peninsula; Waterloo; Balaklava; Sevastopol; South Africa, 1899-1902; Relief of Ladysmith.

2nd Dragoons (Royal Scots Greys).—A guidon as for the 1st Dragoons, but with the following badge: 41A thistle within the circle, and the motto of the Order of the Thistle, “Second to None,” below the circle. The second and third corners contain a blue label with the inscription II.D. The battle honours are: Blenheim; Ramillies; Oudenarde; Malplaquet; Dettingen; Warburg; Willems; Waterloo; Balaklava; Sevastopol; South Africa, 1899-1902; Relief of Kimberley; Paardeberg. The French eagle is placed below the motto. (Fig. 15.)

3rd (King’s Own) Hussars, 4th (Queen’s Own) Hussars, 5th (Royal Irish) Lancers—no guidons.

6th (Inniskilling) Dragoons.—A guidon as for the 1st Dragoons, but with the following badge: The castle of Inniskilling, flying the St. George’s Cross, and the word “Inniskilling” underneath. The second and third corners contain a primrose-coloured label with the inscription VI.D. The battle honours are: Dettingen; Warburg; Willems; Waterloo; Balaklava; Sevastopol; South Africa, 1899-1902. (Fig. 16.)

7th (Queen’s Own) Hussars, 8th (King’s Royal Irish) Hussars, 9th (Queen’s Royal) Lancers, 10th (Prince of Wales’s Own Royal) Hussars, 11th (Prince Albert’s Own) Hussars, 12th (Prince of Wales’s Royal) Lancers, 13th Hussars, 14th (King’s) Hussars, 15th (The King’s) Hussars, 16th (The Queen’s) Lancers, 17th (Duke of Cambridge’s Own) Lancers, 18th (Queen Mary’s Own) Hussars, 19th (Queen Alexandra’s Own Royal) Hussars, 20th Hussars, 21st (Empress of India’s) Lancers—none of these regiments fly guidons.

Almost as attractive as the standards and guidons are the drum banners, or drum cloths, of the cavalry. 42These appointments are usually made of brilliant coloured fabric, richly embroidered in gold, and bear the devices and, at times, the battle honours peculiar to each regiment. To our minds, it is unfortunate that the material chosen in making them does not always correspond with the facings of the unit. Hussars and Lancers, it is pleasing to know, have not been deprived of these banners or cloths.

The three sister regiments of Life Guards and Horse Guards have chosen very similar drum banners. They are crimson, and bear the Royal Arms, with two flying cherubs placed above. Gold embroidery enters largely into the decoration of these fine emblems. No battle honours are shown. The 1st Dragoon Guards carry a blue banner, richly embroidered, with the Royal Arms. The 2nd Dragoon Guards display their nickname, “Bays,” within a golden wreath, surmounted by an imperial crown, all on a cream-buff ground. The motto, “Pro Rege et Patria” (For King and Country), is inscribed on a red scroll. The 3rd Dragoon Guards have selected a banner of the same colour as their facings, namely, yellow. The Prince of Wales’s plume, the motto, “Ich Dien” (I serve), the White Horse, the Rising Sun, the Red Dragon of Cadwallader, and a union wreath all appear on this fine cloth. The 4th Dragoon Guards carry a blue banner bearing the Harp and Crown and the Star of the Order of St. Patrick, emblems showing the Irish origin of the regiment. The White Horse and a union wreath also enter into the scheme of decoration. The 5th Dragoon Guards display the White Horse, the regimental initials V. D.G., and the title, “Princess Charlotte of Wales,” on a blue scroll, all on 43a crimson cloth; (the facings are dark green). The 6th Dragoon Guards have a semi-circular banner of white material, tastefully decorated with a number of blue labels and a gold wreath encircling the regimental badge—a shield supported by a pair of crossed carbines, surmounted by an imperial crown. The 7th Dragoon Guards carry a neat blue banner decorated with the Royal Arms, a golden wreath and a scroll inscribed “The Princess Royal’s Dragoon Guards.” Turning now to the 1st Royal Dragoons, we have a dark blue cloth bearing, in gold, the Crest of England within the Garter, the Eagle, of which we spoke, a wreath of oak and laurel, the motto “Spectemur agendo,” and the regimental title. The 2nd Dragoons, the Scots Greys, show a light crimson banner, having in the centre the Thistle, around which is inscribed the motto, “Nemo me impune lacessit” (No one hurts me with impunity). The French Eagle, two flaming grenades, a wreath of golden thistles, and the motto, “Second to none,” are also given. The 3rd (King’s Own) Hussars have silver decorated drums, and possess no drum cloths. The 4th Hussars have the Royal Arms and a number of battle honours on their yellow banner. The 5th Lancers own a neat green cloth which bears the Harp and Crown, the motto, “Quis separabit” (Who shall separate?), a golden-brown wreath, two crossed lances, and a scroll inscribed with the words, “Fifth Royal Irish.” No battle honours appear. This cloth is shown in Fig. 13. The 6th Dragoons reveal their connection with Inniskilling by using the castle as a badge. A golden wreath and the imperial crown are also given, all on a yellow background. The 7th Hussars possess a dark blue banner, 44ornamented with the monogram Q.O. (i.e., Queen’s Own) interlaced within a garter, and surmounted by a crown. Battle honours are given on light blue scrolls. The 8th Irish Hussars display the harp and crown, a number of battle honours, and the regimental initials 8.K.R.I.H. (King’s Royal Irish Hussars) on a brownish-red cloth. The motto, “Pristinæ virtutis memores” (The memory of former valour), is given on a blue scroll. One of the most attractive designs is that used by the 9th Lancers. The cypher of Queen Adelaide, reversed and interlaced, within a garter, is surmounted by an imperial crown, and backed by a pair of crossed lances. The numerous battle honours are given in a circular ring, whilst the figures IX. are placed below the ring. The cloth is crimson. The 10th Hussars have the alternative title of the Prince of Wales’s Own. Their banner, accordingly, bears the Prince’s plume and motto. The honours are woven into a golden wreath which encircles the Rising Sun and Cadwallader’s Red Dragon. The material is royal blue. The 11th Hussars display the late Prince Consort’s crest and motto, “Treu und fest” (True and firm), the Egyptian Sphinx, the regimental initials, XI.H., all surmounted by a crown, and the inscription, “Prince Albert’s Own Hussars.” The cloth is crimson. The 12th Lancers also have a crimson banner, embellished by the plume of the Prince of Wales, the Egyptian Sphinx, the regimental number XII., a golden wreath, and a pair of crossed lances. The 13th Hussars wear the royal cypher enwreathed with leaves of laurel and oak, the imperial crown, and the usual array of battle honours. The motto, “Viret in Æternum” 45(Virile for ever), figures on this cream-buff banner. (Fig. 14). The 14th Hussars, being known as the 14th King’s Light Dragoons, bear this title on a golden scroll, which is placed above the royal crest within the Garter. The battle honours are inscribed upon the leaves of a laurel wreath. The cloth is crimson. Of the same colour is the drum banner of the 15th Hussars. This regiment displays the royal crest, the King’s cypher, the figures XV., the battle honours, and a golden wreath of laurel and oak. A royal blue cloth is carried by the 16th Lancers; it bears the crossed lances, which figure on all Lancer drum cloths, except those of the 17th Lancers. In this case, the well-known device of a skull and crossbones is placed within a garter, surmounted by a crown and enwreathed with a band of oak and laurel leaves. The cloth is deep blue. (Fig. 12.) The 18th Hussars are known by their deep crimson banner, bearing, among the battle honours, the inscriptions, XVIII. Hussars, Queen Mary’s Own, and the motto, “Pro rege, pro lege, pro patria conamur” (For king, for law, for country we strive). The 19th Hussars have a white cloth, showing the letter A, interlaced with the Dannebrog,[9] below which is the White Elephant of Assaye, and around it a number of labels bearing battle honours, and the inscription, Queen Alexandra’s Own Royal Hussars. The 20th Hussars favour a crimson banner, which is embellished by a large golden wreath from which are growing roses, thistles and shamrocks. The royal cypher and the imperial crown are given the central position. The last 46cavalry regiment, the 21st (Empress of India’s) Lancers, owns probably the most fanciful drum banner. The letters V.R.I. are cleverly interlaced and supported by a pair of crossed lances, the whole encircled by a union wreath and the imperial crown. “Khartoum” is inscribed upon a dark blue scroll. The banner is French grey.

Following on the Cavalry, in the Army List, comes the Yeomanry, which forms part of the Territorial Force. This unit of the Army is divided into Dragoon, Hussar and Lancer divisions, an example of each being the Westminster Dragoons, the Royal Gloucestershire Hussars, and the City of London Rough Eiders. The Dragoons, as a rule, are the only section which carry flags—in all cases they are guidons—but it must be mentioned that some Dragoon regiments display no colours, whilst a certain few of the other divisions possess these emblems, though they may not have received official recognition. Most regiments own drum cloths, but some of those raised since the Boer War carry no drums and, in consequence, wear no drum cloths. In one or two instances, i.e., in the North Somerset Yeomanry, ornamental drums are provided which need no cloth embellishments.

Yeomanry guidons are made of crimson material, edged with gold and red fringe; the pole is surmounted with the Royal lion and crown; and, in most cases, the distinctive badge is ensigned with the Royal crown, and encircled by the union wreath. The only battle honour inscribed on these flags is “South Africa,” but all regiments do not possess it.

48The Berks Yeomanry, which has its headquarters at Hungerford, flies the standard pattern of guidon, with a White Horse as central badge. This animal, as revealed on the banner, is a very poor specimen, but as it is an imitation of the one cut in the turf on the downs, we can appreciate the reason for its adoption.

The Derbyshire Yeomanry has the united red and white rose for its badge. This flower is ensigned with the imperial crown and, therefore, the ordinary crown is not placed above and outside the circular label, as is usual.

The Essex Yeomanry boasts of a motto: “Decus et Tutamen” (Honour and safety), which is inscribed on a scroll placed under the badge, consisting of a red escutcheon charged with three seaxes. These weapons are reminders of the county’s connections with bygone Saxon occupation. (Fig. 41.)

The Fife and Forfar Regiment, which hails from Cupar, is proud of its badge, a representation of the Thane of Fife. Readers of Macbeth will remember that Macduff was a descendant of the original Thane of Fife, a fine soldier who obtained a grant of the shire of Fife from Kenneth II. in recognition of his assistance when fighting against the Picts.

The Hampshire Carabiniers have the appropriate device of two carbines in saltire. They also have a rose at each corner of the guidon, white in the first and fourth corners and red in the second and third.

The Herts Yeomanry have a stag for device, whilst the Lanarkshire Yeomanry, a regiment possessing the 49alternative lengthy title of “Queen’s Own Royal Glasgow and Lower Ward of Lanarkshire,” flies a flag of the ordinary type revealing no particular badge.

The Duke of Lancaster’s Own bear the appropriate red rose of the House of Lancaster, and here we may mention that the Yorkshire Dragoons Yeomanry (Queen’s Own) display the white rose of York.

Lothians and Border Horse Yeomanry show a garb which, in non-heraldic terms, is a shock of corn.

The Montgomeryshire Yeomanry use a red dragon with green wings as the central badge, which is surrounded by a union wreath not of the regulation design.

The Norfolk Yeomanry has broken away from the traditional pattern of guidon. In each of the four comers is the Royal Cypher ensigned with the imperial crown, and in the centre are the Royal Arms. The Royal residence in Norfolk, and the King’s special interest in this county probably account for the presence of these emblems.

The Scottish Horse display the cross of St. Andrew on a blue groundwork, as the central badge, whilst in the four corners is the thistle ensigned with the imperial crown. This is one of the most pleasing guidons of the Yeomanry Force.

The Shropshire Yeomanry have as the central badge on their guidon a rendering of the arms of the Shropshire County Council (i.e., three tigers’ heads).

The Sussex Yeomanry display a badge comprising six martlets perched in three rows, all on a Blue 50background, whilst the Northamptonshire Yeomanry give another rendering of the well-known white horse.

The Westminster Dragoons, otherwise known as the 2nd County of London Yeomanry, have the Royal Cypher and Crown as central badge, whilst in the first and fourth corners are crossed axes, and in the second and third, Beaufort’s portcullis. These four devices are encircled by a union wreath of special design. (Fig. 42.)

If we leave the Yeomanry guidons, and turn to the drum banners, a more interesting set of emblems will be brought to our notice. The guidons may be accused of possessing a somewhat monotonous semblance one with the other, but this is not a characteristic of the drum cloths. They are gay-coloured, smart in appearance, and endowed with emblematic ornamentation of an interesting nature.