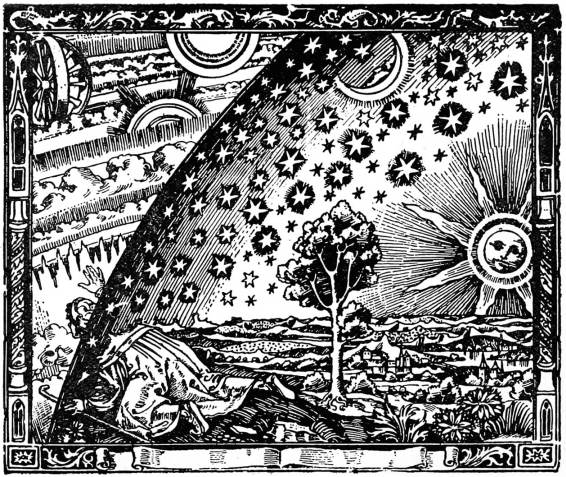

“A Missionary looking over the edge of the world at the point where Heaven and Earth meet.”

(From an old print.)

Title: History of Geography

Author: Sir John Scott Keltie

O. J. R. Howarth

Release date: November 25, 2018 [eBook #58349]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Turgut Dincer, Charlie Howard, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

“A Missionary looking over the edge of the world at the point where Heaven and Earth meet.”

(From an old print.)

BY

J. SCOTT KELTIE, LL.D.,

SECRETARY OF THE ROYAL GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY,

AND

O. J. R. HOWARTH, M.A.,

ASSISTANT SECRETARY OF THE BRITISH ASSOCIATION FOR

THE ADVANCEMENT OF SCIENCE

[ISSUED FOR THE RATIONALIST PRESS ASSOCIATION, LIMITED]

London:

WATTS & CO.,

17 JOHNSON’S COURT, FLEET STREET, E.C.

1913

v

This is not a history of geographical exploration, though the leading episodes in the advance of our knowledge of the face of the Earth are necessarily referred to in tracing the evolution of geography as a department of science. That is the object of this volume as one of a series dealing succinctly with the history of the various sciences. We are not concerned to discuss whether Geography is entitled to be considered as a science or not. It is hoped that in the attempt to tell the story of its evolution up to the present day it will be evident that it is as amenable to scientific methods as any other department of human knowledge, and that it performs important functions which are untouched by any other lines of research. I use the first person plural because I am greatly indebted to Mr. O. J. R. Howarth in coming to my help after I had accumulated much of the material, but was seriously delayed owing to a great increase in my official duties. The greater share of whatever merits the book may possess ought to be awarded to Mr. Howarth.

I am indebted to Mr. E. A. Reeves’s interesting little book on Maps and Map-making for many of the illustrations.

J. Scott Keltie.

July 2, 1913.

vii

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Beginnings | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| The Geography of the Greeks and Romans | 8 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| The Dark Age | 33 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| The Mediæval Renascence | 42 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Portuguese Expansion and the Revival of Ptolemy | 51 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| The New World | 59 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| The Far East and the Discovery of Australia | 68 |

| CHAPTER VIII.viii | |

| Polar Exploration to the Eighteenth Century | 74 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| James Cook and His Successors | 87 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Measurement, Cartography, and Theory, 1500–1800 | 90 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| The Nineteenth Century: African Research | 107 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| The Nineteenth Century and After: Asia and Australia | 115 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| The Nineteenth Century and After: The Poles | 122 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| The Nineteenth Century and After: Evolution and Progress of Geographical Science | 135 |

| Short Bibliography of Geography | 147 |

| Index | 149 |

ix

| A Missionary Looking Over the Edge of the World | Frontispiece |

| FIG. | PAGE |

| 1.—Tahitian Map | 2 |

| 2.—The World as Supposed to Have Been Conceived by Hecatæus | 11 |

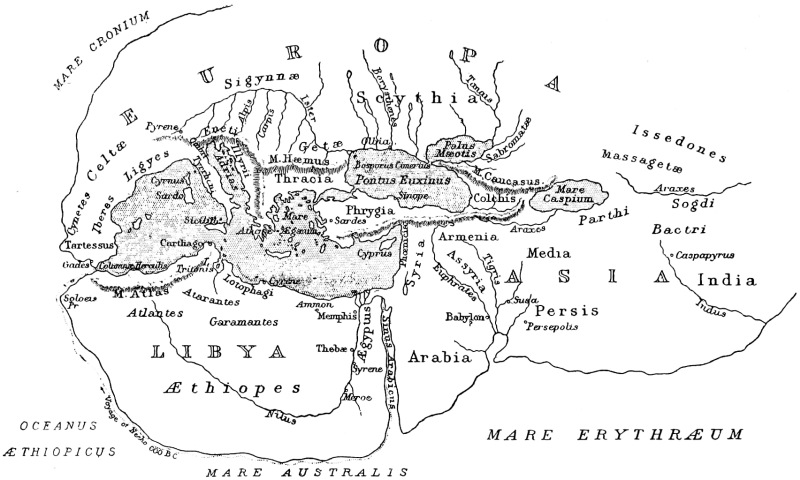

| 3.—The World According to Herodotus b.c. 450 | 15 |

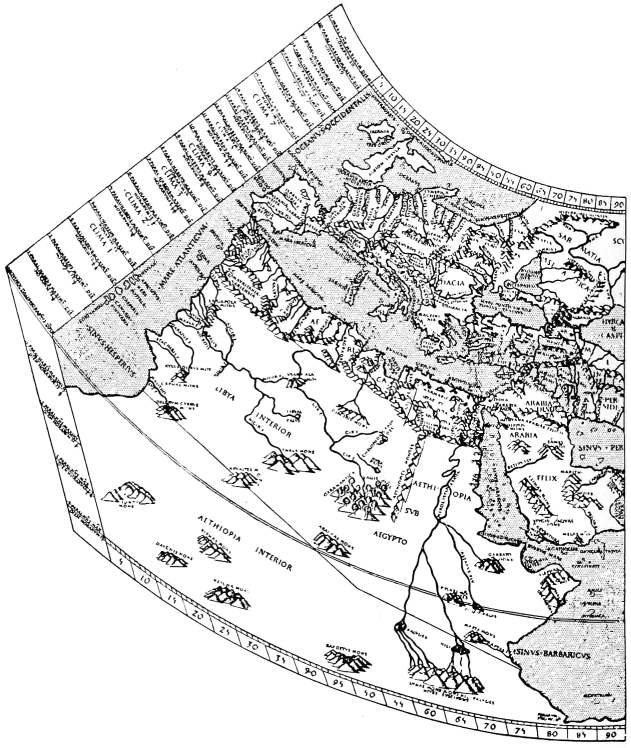

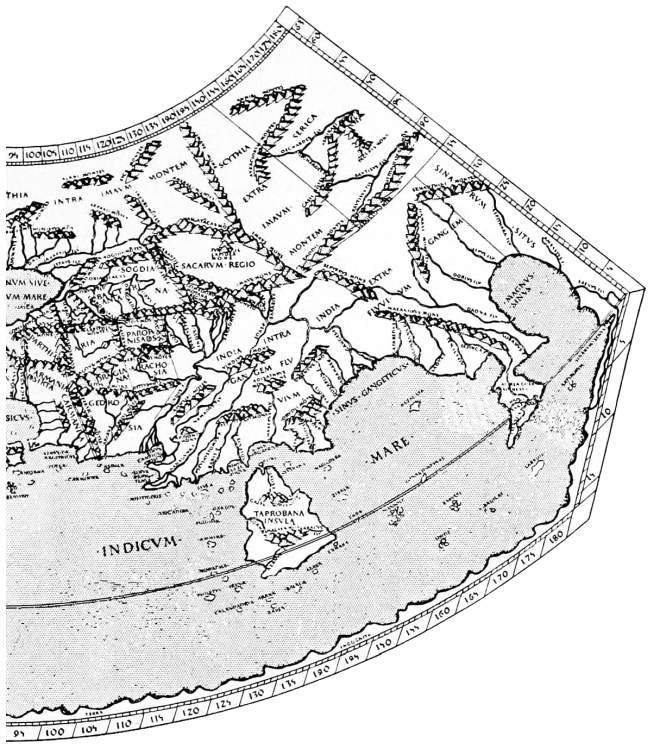

| 4.—The World According to Ptolemy | 28–29 |

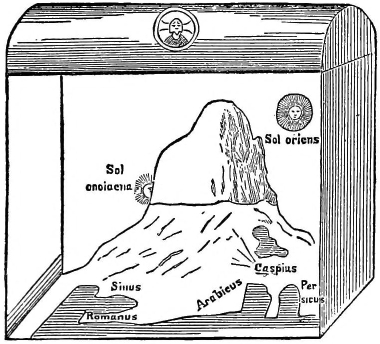

| 5.—The World According to Cosmas Indicopleustes | 35 |

| 6.—Beatus’s Map | 38 |

| 7.—The Hereford Map | 47 |

| 8.—Chart of the Mediterranean, 1500, by Juan de la Cosa | 49 |

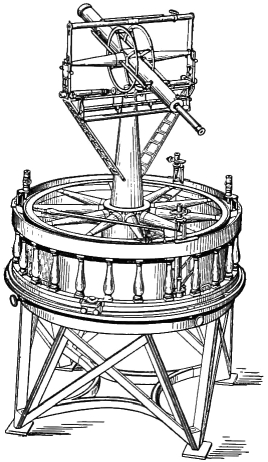

| 9.—Scaph | 91 |

| 10.—Astrolabe | 91 |

| 11.—Quadrant | 92 |

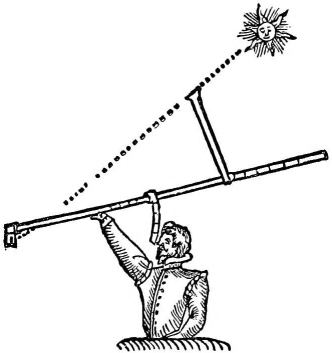

| 12.—Cross-staff | 94 |

| 13.—Davis’s Back-staff | 95 |

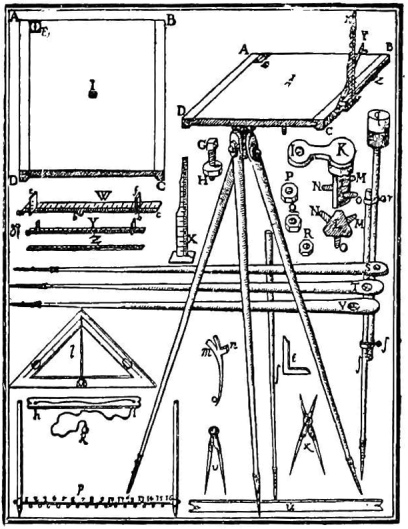

| 14.—Pretorius’s Plane-Table | 96 |

| 15.—Ramsden’s Theodolite | 97 |

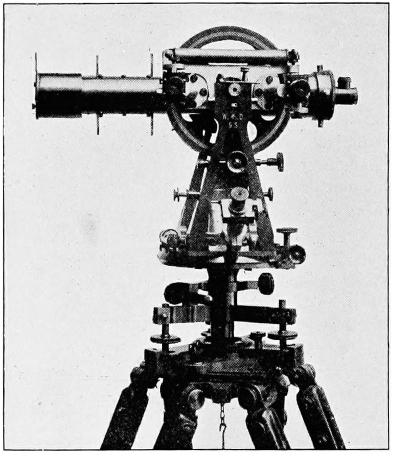

| 16.—Modern Five Inch Transit Theodolite | 98 |

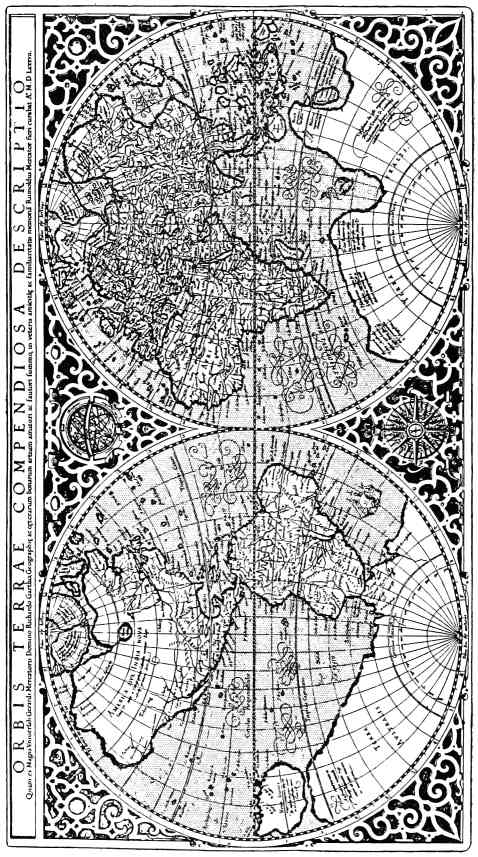

| 17.—The World According to Mercator (1587) | 100 |

1

We need not attempt any elaborate definition of Geography at this stage; it is hoped that a fairly clear idea of its field and functions may arise during the following brief summary of its history and evolution. The old-fashioned definition, “A description of the earth,” is serviceable enough if accepted in its widest sense. Geography may be regarded as the mother of the sciences. Whatever was the origin of man, whether single or multiple, and wherever he emerged into manhood, he was a wanderer, an explorer, from the first. Necessity compelled him to make himself familiar with his environment and its resources, and as the race multiplied emigration became compulsory. The more that relics of primitive humanity are brought to light, the further back must man’s earliest wanderings be dated. The five thousand years of the old Biblical chronology must be multiplied a hundred times, and still we find that half a million years ago our primitive forefathers must have travelled far from the cradle of the race. They were unconscious geographers. Their conceptions of the earth and of its place in the universe are unknown to us; it is not impossible to infer something of them by analogy of ideas existing to-day among more or less primitive peoples, though to do so is beyond our present scope. Yet it may be said that certain root-ideas of geographical theory and practice must surely date from the earliest period of man’s capacity2 for observation. Thus the necessity for describing or following a particular direction presupposes the establishment of a definite standard—the face would be turned towards the position of some familiar object; then in that direction and the opposite, and to the right hand and the left, four such standards would be found, and would become the “cardinal points.” The value, for this purpose, of so patent a phenomenon as the rising and setting of the sun must have been impressed upon human intelligence at an elementary stage. Again, map-making is not very far removed from a primitive instinct. Modern travellers have described attempts at cartography by the North American Indians, the Eskimo, and the Maori and other less advanced inhabitants of the Pacific Islands.

It is again beyond the scope of the present summary of the development of geographical knowledge among European peoples to attempt to give any detailed history of exploration; it is only possible to deal with the salient episodes, and these mainly in so far as they have influenced man’s general conception of the earth. Nevertheless, ages before the existence of any documentary evidence of its development geographical knowledge must have advanced far in other lands. America was “discovered” probably thousands of years before Columbus stumbled against the New World, or even the Norsemen had set foot in “Vineland”; it had time, before the Spaniards swarmed over it, to become the seat of civilizations whose origin is far beyond knowledge. It is worth noticing for our3 particular purpose that the European conquerors found evidence of highly developed geographical methods both in Central America and in Peru; the native maps were intelligible to them, and the Peruvian Incas had even evolved the idea of relief maps. China, again, a great power in early ages, possessed knowledge of much of central Asia; India was the seat of powerful States and of a certain civilization; Babylonia and Egypt were working out their destinies, and had their own conceptions of the earth and the universe, long before the starting-point of the detailed investigation within our present view.

But the names of Babylonia and Egypt bring us nearer to that starting-point. The history of Europe dawns in the eastern Mediterranean, and so does the history of geography. It has, however, to be premised that connection existed, in very early times, between the eastern Mediterranean circle and the lands far beyond. When princes of Iranian stock (to cite a single illustration) are found established on the confines of the Levant as early as the fifteenth century B.C., it may be realized that the known radius from the Mediterranean centre was no short one. Much earlier than this—even in the fourth millennium B.C.—astronomy, a science of the closest affinity to geography, was well organized in Babylonia, and there is evidence for a cadastral survey there. Clay tablets dating from more than two thousand years B.C. show the work of the Babylonian surveyors.

The Egyptians worked along similar lines. Examples of their map-work include a plan, in the museum at Cairo, showing the basin of the lake Mœris, with its canal and the position of towns on its borders, together with notes giving information about these places; and,4 in Turin, a map of the Wadi Alaiki, where the Nubian goldmines were situated; and this map may date from the earlier half of the fourteenth century B.C.

Meanwhile, in the Ægean lands and from Sicily to Cyprus, at points principally but not invariably insular or coastal, and especially in Crete, communities grew up that developed a high standard of civilization, to which the general name of Ægean is given. It appears that a central power became established in Crete about the middle of the third millennium B.C., and that an active oversea trade was developed in the Ægean and the eastern Mediterranean during the ensuing thousand years. As for the knowledge of the mainland which came to be called Europe, it is suggested that the Ægean civilization was assailed, about the fifteenth century B.C., by invaders from the north, and was practically submerged, probably by a similar movement, five hundred years later; and invasion presupposes intercourse.

The Phœnicians, next taking the lead in Mediterranean maritime trade, must have extended knowledge of the inhabited world, even though they left the reputation of secretiveness in respect of their excursions (a natural and not uncommon characteristic of pioneer traders). A Semitic people, they seem to have emigrated from the Persian Gulf in detachments, and established independent settlements on the Levantine littoral. Tyre was their chief trading city. They provided the commercial link between east and west. Their penetration of the western Mediterranean and even of the Straits of Gibraltar is assigned to the earliest period of their activities. They established relations not only with the Greeks and other Mediterranean peoples, but also with central European traders;5 they are said, for example, to have dealt in amber brought from the Baltic overland to the Adriatic and to the mouth of the Rhone. They founded colonies in Cyprus, Sicily, and elsewhere as far as the west of Spain, where Gades (Cadiz) was established perhaps about 1100 B.C. Thence they carried their enterprises far to the north. If they did not actually exploit the tin of Cornwall, they probably knew of Britain. One of the greatest enterprises of antiquity, if we may trust Herodotus, who was, however, sceptical, was conducted by Phœnician navigators under the auspices of Necho, king of Egypt, about 600 B.C. Even before this they brought from distant lands, it may be the Malay peninsula or it may be what is now Rhodesia, gold and other presents for King Solomon. If the Phœnicians had really found their way as far as the Zambezi and the country on the south, they may well have conjectured that it would be possible to sail round Africa. At any rate, if the story as told by Herodotus is true, Necho was convinced that Africa could be circumnavigated. The Phœnician navigators sailed down the Red Sea, and in autumn landed on the coast and sowed a crop of wheat; when this was reaped, they started again and made their way south round the Cape of Good Hope, and so northward, entering the Mediterranean in the third year. At one part of their course they had the sun on their right, which would be natural, though Herodotus regarded this as evidence of the incredibility of the narrative. There is no inherent impossibility in such an expedition, but it led to no direct results; no further effort was made to round the continent for twenty centuries.

The Phœnicians founded Carthage about 850 B.C. (though an earlier trading post occupied the site), and6 the Carthaginians carried out trading enterprises on their own account from their central point of vantage on the North African coast. Some time after Necho’s expedition (probably about 500 B.C.) they sent out two distant expeditions. One of these, under Hanno, appears to have consisted of a very large fleet, and to have been intended to establish trading posts along the west coast of Africa, which was already known to the Carthaginians. Certain details are furnished which serve to identify points at which he touched, and it is generally agreed that he got as far south as the neighbourhood of the Bight of Benin. Almost simultaneously Himilco made a voyage north along the west coast of Europe. He appears to have visited Britain, and mentions the foggy and limitless sea to the west.

Information obtained by such means as this cannot have become in any sense the common property of the period. But there would be no mean supply of geographical data at the disposal of traders on the one hand, and at least of a few philosophers and generally well-informed persons on the other, at a period long anterior to that at which it is possible to begin our detailed history. Whatever tendency there may have been on the part of the Phœnicians, and no doubt their predecessors, to preserve their commercial secrets, there is no necessity to suppose that traders in distant lands did not describe these lands to those with whom they immediately dealt. The links in the commercial chain would then become links in a chain of geographical knowledge. This supposition granted, geographers may be prepared to risk the charge of temerity if they recognize and enjoy, as an exquisite description of the unbroken summer daylight on some northern fjord-coast, the picture of the Læstrygons’ land in7 Odyssey, X.: “Where herdsman hails herdsman as he drives in his flock, and the other who drives forth answers the call. There might a sleepless man have earned a double wage, the one as neatherd, the other shepherding white flocks: so near are the outgoings of the night and of the day.” And again, “the fair haven, whereabout on both sides goes one steep cliff unbroken, and jutting headlands over against each other stretch forth at the mouth of the harbour, and strait is the entrance ... no wave ever swelled within it, great or small, but there was a bright calm all around.”1 Here are words which on their face indicate hearsay in the Mediterranean concerning Scandinavia in the Homeric age. Again, the gloomy home of the Cimmerians, at the uttermost limit of the earth, suggests hearsay of the arctic night. As to Homeric geography generally, it may be said briefly that the lands immediately neighbouring to the Ægean are well known, though there is little evidence of knowledge of the inhospitable interior of Asia Minor; something is understood of the tribes of the interior of Europe to the north; the riches of Egypt and Sidon are known; mention is made of black men, and even of pygmies, in the further parts of Africa; the western limit of anything approaching exact knowledge is Sicily. The earth is flat and circular, girt about by the river of Ocean, whose stream sweeps all round it.

1 Trans. S. H. Butcher and A. Lang.

Thus we have found geographical knowledge, so far as it is possible to trace its acquisition at all, to have been acquired for purely commercial purposes, and it remained for the Greeks to seek for such knowledge for its own sake. It has been well said that the science of geography was the invention of the Greeks.

8

The birthplace of Greek geographical theory is to be found, not in Greece proper, but in Asia Minor. Miletus, a seaport of Ionia, near the mouth of the Mæander, became the leading Greek city during the seventh to the sixth centuries B.C., trading as far as Egypt and throwing off colonies especially towards the north, on the shores of the Hellespont and the Euxine. It was thus an obvious repository for geographical knowledge, besides being a famous centre of learning in a wider sense. Thales of Miletus (640–546 B.C.), father of Greek philosophers, geometers, and astronomers, may have learnt astronomy from a Babylonian master in Cos, and became acquainted with Egyptian geometry by visiting that country; he applied geometrical theory to the practical measurement of height and distance. He has been wrongly credited with the conception of the earth as a sphere. That conception is actually credited to Pythagoras, who, born in Samos probably in 582 B.C., settled in the Dorian colony of Crotona in Southern Italy about 529 and founded the Pythagorean school of philosophy. He (or his school), however, evolved the correct conception of the form of the earth rather by accident (so far as concerns any scientific consideration) than by design, for the Pythagorean reasoning was abstract in nature, in distinction from that of the Ionian school, which sought9 material explanations for the phenomena of the universe. The Pythagoreans (whose view does not greatly affect the later history of geographical theory) conceived the earth as a globe revolving in space, with other planets, round an unseen central fire whose light was reflected by the sun, just as the moon reflects the sun’s light. Later the philosopher Parmenides, of Elea in Italy (c. 500 B.C.), considered the universe to be composed of concentric spheres or zones consisting of the primary elements of fire and darkness or night. Anaximander (611-c. 547 B.C.), a disciple of the more practical Ionian school, and a pupil or companion of Thales, conceived an earth of the form of a cylinder. He is said to have introduced into Greece the gnomon, a primitive instrument for determining time and latitude, and to have made a map. The first actual record of a Greek or Miletan map, however, occurs half a century after his time, when in 499 B.C. Aristagoras, tyrant of Miletus, asked aid of Cleomenes of Sparta against Persia, and showed him a map, engraved on bronze, of the route of his proposed expedition. Anaximenes, of Anaximander’s school, gave the earth an oblong rectangular form.

The physical division of land into continents, though obvious, presupposes the existence of a certain measure of geographical theory. Still more obvious as a primitive division would be a division simply between “my land” and “yours.” But there was a clear necessity at a very early period for names to distinguish, generally, the lands which lay on one side and the other of the Ægean-Mediterranean waters. It may well be that the names of Europe and Asia did not possess precisely this application in their original forms. Their derivation has been assigned to an Asiatic source; they signify on this view the lands respectively of darkness or sunset10 and of sunrise or light—that is to say, the lands towards west and towards east. The earliest known Greek reference to Europe, moreover, does not indicate on the face of it a distinction from Asia, though it does indicate a distinction from lands separated from it partly or wholly by water. The Homeric hymn to Apollo, which may be dated in the eighth or seventh century B.C., refers to dwellers in the rich Peloponnese and in Europe and in the sea-girt islands—albeit in place of “Europe” some scholars would read a word signifying simply “mainland.” The name of Europe, if admitted here, is taken to mean no more than northern Greece, and would thus lend some colour to an early tradition that it was derived from a Macedonian city called Europus. However this may be, it is easy to conceive that the name of Europe, being at no time given to a territory with defined frontiers, was capable of an elastic application, which would be gradually extended, or (as is more probable under primitive conditions of geographical knowledge) would remain so vague as to permit of no clear definition.

But when the names of continents emerge in Greek usage they afford the necessary distinction between the lands on either side of the Ægean-Mediterranean. They so emerge in the 6th–5th centuries B.C., and the distinction appears by that time to have been perfectly familiar, though the precise application, as will be seen, was a matter of controversy. The poet Æschylus (525–456 B.C.), who, by the way, was also a traveller, possibly to Thrace, certainly to Sicily, was acquainted with the distinction, as appears, for example, from passages in the historical drama of the Persæ, which deals with the failure of Xerxes’s invasion of Europe from Asia, and his retreat across the Hellespont. The11 distinction would hardly have been introduced into a stage-play if it had not been commonly recognized. In Prometheus Unbound, again, Æschylus refers to the river Phasis (Aras) as the boundary between Europe and Asia. Finally, Herodotus states in an early chapter of his work that the Persians appropriate to themselves Asia and the barbarian races inhabiting it, while they consider as separate Europe and the Greek race, and he does not find it necessary to offer any explanation of the names here. At a later stage the continental distinction appears to have been based on or associated with a distinction between temperate and hot lands.

Hecatæus of Miletus (c. 500 B.C.) has been hailed as12 the father of geography on the ground of his authorship of a Periodos, or circuit of the earth, the first attempt at a systematic description of the known world and its inhabitants. But even if he wrote such a work, evidence has been adduced that the extant fragments of it belong to a later forgery. However, he was a Miletan and a traveller, besides a statesman. The map which is supposed to have accompanied his work maintained the old popular idea of the earth as a circular disc, encircled by the ocean. Greece was the centre of the world, and the great sanctuary of Delphi was the centre of Greece. If this Periodos is taken as a forgery, there is a parallel case in the Periplus of the Mediterranean attributed to Scylax of Caryanda, a contemporary of Hecatæus. If Scylax wrote any such work, in its extant form it is a century and a half later than his time. He is said to have explored the Indus at the command of Darius Hystaspis, and to have returned by the Indian Ocean to the Red Sea.

Herodotus of Halicarnassus (c. 484–425 B.C.) was a historian, but was widely travelled, and understood the importance of a knowledge of the geography of a country, and its bearings on the history of its people. He only introduces geographical information in so far as it throws light on the history with which he is dealing, or because it seemed to him of special interest, or as a report of curious information obtained from the countries which he visited; but he has certainly some more exact information about the restricted world of which Greece was the centre than any of his predecessors. He visited Egypt and the Greek colony of Cyrene, on the coast of what is now Tripoli. There is reason to believe that in Asia he got as far as Babylon on the Euphrates, and perhaps as far as Susa13 beyond the Tigris. He crossed the Euxine to the northern shore as far as Olbia on the Borysthenes, and probably went round to the south-east coast to the country of the Colchians, whose characteristics he describes as if from personal knowledge. He does not seem to have got very far west in the Mediterranean, though he spent the latter part of his life in southern Italy. There is little doubt that he visited several of the Grecian islands. But apart from the information about the countries round the Mediterranean which he collected personally, his history contains material from various sources concerning the countries and peoples in Europe, Asia, and Africa. This information, on the whole, is of the vaguest kind, and shows that the Greeks whom Herodotus may be taken to represent were only groping their way with regard to a knowledge of the world outside the limits of their own restricted sphere. This vague knowledge included a considerable section of western Asia as far as the Caspian Sea and the river Araxes. Herodotus had also heard of India and of the Indus river, and had a fair knowledge of the Persians, the Medes, and the Colchians, as also of part at least of Arabia. Eastwards, in what might be called Central Asia, he had heard of the Bactrians and Sogdians to the south of the Jaxartes (Syr-darya, the northern of the two great affluents of the Sea of Aral), and of the Massagetæ, Issedones, Arimaspians, and other races or peoples; those to the north of the Jaxartes being included, according to Herodotus, in Europe, which he took to extend from the Pillars of Hercules (Strait of Gibraltar) to the Hellespont and up the Phasis (Rion) river, from its mouth in the Black Sea, to the Caspian. He also divided Asia from Libya (Africa) along the14 axis of the Red Sea, and was thus in conflict with others who had divided Europe from Asia at the Tanais, and Asia from Libya at the Nile. He would not permit a theoretical boundary-line to “bisect a nationality,” as the Nile does.

It may be well to examine Herodotus’s geographical knowledge in some detail, as representing the general knowledge possessed by a student (increased by his own travels) as distinct from that possessed by traders and colonists in different particular directions. His knowledge of Europe proper was contained within rather narrow limits. He knew, from personal knowledge, or from information obtained from merchants and colonists familiar with the shores of the Euxine (Black Sea), of the country lying to the north of that sea for some distance, of the rivers which flowed into it from the north and from the west, and of various peoples either settled in or wandering over the land that is now mainly included in Russia. His notions of the comparative dimensions of the Euxine and of the Mæotis Palus (Sea of Azov) are altogether erroneous, as might have been expected; but he knew (though in the main vaguely) of the Tanais (Don), the Borysthenes (Dnieper), and other rivers which flow into those seas. The Ister (Danube) he knew as a river of considerable importance, but he made it rise in Spain and flow north-east and east through the greater part of Europe. He conceived it as corresponding to some extent in the direction of its course with that of the Nile on the other side of the Mediterranean. He had some vague notion of the Iberians and of the Celts, as inhabiting the country to the north of the Pillars of Hercules. He knew something of the country lying to the north of Greece, Illyria, Thessaly, and Thrace, and the Rhodope1516 mountains. He has much to tell of the Scythians inhabiting the country north of the Black Sea, but it is difficult to make out exactly to what race they belonged and whither they had wandered; they may have been the forerunners of the Slav peoples. Of Europe to the north of the Danube, and of the Scythian country, he had no information of any importance. He did not believe in the Hyperboreans, nor did he credit the statement that there was any sea north of Europe. He has a good deal to say about Africa. He had been up the Nile as far as the first cataract to the old city of Elephantine, but above that his information is vague and largely erroneous. He knew of the great bend which the Nile takes to the west above Elephantine, and had heard of Meroe on the other side of that bend; but his notion of the length of Africa was so erroneous that, instead of carrying the Nile south into the interior of the continent, he made it rise far to the west and run eastwards before it turned north at Meroe. But he at least controverted the view that it rose in the ocean itself to the south—a belief based possibly on some rumour, transmitted through many lips, of the existence of great lakes towards its headwaters. As for a river flowing west-and-east, in the west of the continent, he had heard of such a river in a story of five Nasamonian youths who travelled south from the shore of the Syrtis, crossed the desert for many days, and were at last taken captive by black men of small stature, who carried them to a city on the banks of this river, whence they were subsequently allowed to return. It has been eagerly discussed what truth underlies this story, and whether the river was the Niger in its upper course; but at best the account added little to17 the knowledge of distant Africa. The idea of a pygmy people dwelling towards the southern shore of the ocean is older than the Iliad in which it is found (III, 3). Herodotus’s conception of the shape of Africa did not carry its southward extension much beyond the latitude of Cape Guardafui. He discarded the popular conception of the round earth, regarding it as longer from east to west than from north to south. The philosopher Democritus of Abdera (born c. 470–450) exhibited the same conception in a map which he constructed.

An important episode in the progress of a more accurate knowledge of the world of the Greeks was the Retreat of the Ten Thousand under Xenophon in 401–400 B.C. The younger Cyrus had made a great expedition from Sardis, in western Asia Minor, eastwards through the Cilician Gates to the Euphrates, and along the course of that river to the neighbourhood of Babylon. He was accompanied by a band of Greek mercenaries, who, after his defeat at Cunaxa, began the retreat of which Xenophon left a graphic account, containing what must have been to the Greeks much new information concerning the region from the junction of the Tigris and Euphrates northwards past Lake Van and through the mountains of Armenia, north and west to the shores of the Black Sea at Trapezus (Trebizond), and along the south coast of the Black Sea, partly by sea and partly by water, to Byzantium. Xenophon’s story is an illustration of the well-known fact that war is one of the chief means of promoting geographical knowledge. This will appear more clearly in the next important episode in the story of exploration—the campaign of Alexander the Great.

In the interval there were one or two writers from18 whose work something is to be gathered of Greek geographical knowledge and theory about the middle of the fourth century. The philosopher Plato (427–347 B.C.) may be referred to here in connection with his story, based on an Egyptian tradition, of the great island of Atlantis, that land which plays so important a part in later mythical geography. In the Egyptian story it lay just beyond the Pillars of Hercules, and adjacent to it was an archipelago. This would aid its later identification with the Canaries, though it came also to be connected with America and other known lands besides, as well as giving name to an island in the Atlantic Ocean, the disproof of whose existence may almost be called modern. From Plato’s account of Atlantis as the home of a powerful people who in early times invaded the Mediterranean lands, it has also been sought to associate the tradition with Crete at the period of the Ægean civilization mentioned in the first chapter.

Some fragments exist of the writings of the historian Ephorus of Cyme in Æolis (c. 400–330 B.C.). He seems to have endeavoured to cover the whole field of the world as known to the Greeks, and conceived the four most distant regions of the earth to be occupied on the east by Indians, on the south by Ethiopians, on the north by Scythians, and on the west by Celts. The last he considered as occupying all Spain, as well as Gaul. Strabo (p. 24) commended his geographical work and his skill in separating myth from history. A document of this period is the Periplus, already referred to as known under the name of Scylax. This class of work became more and more common as navigation developed, and corresponded in some measure to the modern Admiralty guide or pilot. The Periplus19 is confined mostly to the regions known to the Greeks bordering the Mediterranean. From the Pillars of Hercules the writer follows the north coast eastwards, including the Adriatic and the Euxine as far as the mouth of the Tanais, which he regards as the continental boundary. He then follows the Levantine coast, the north African coast westward, and the west African coast as far as the island of Cerne. He incidentally makes what is regarded as the earliest extant mention of Rome; but his notions of rivers and other features away from the coast are generally erroneous.

Aristotle (384–322 B.C.), in two of his extant works, the Meteorologica and the treatise on the Heavens, revealed something of his ideas on physical geography and the figure of the earth and its relations to the heavenly bodies. He believed the earth to be a sphere in the centre of the universe, because that was a form which matter gravitating towards a centre would necessarily assume, also because the shadow cast by the earth on the moon during an eclipse is circular. He accepted the conclusion that the circumference of the earth was 400,000 stadia (nearly 46,000 miles). His views with reference to the cosmical relations of the earth were the same as those adopted by Eudoxus of Cnidus (fl. middle fourth century), but he did his best to prove them. He adopted, however, the prevalent view that the habitable world was confined to the temperate zone between the tropics and the arctic regions. He believed there must be a temperate zone in the southern hemisphere, though he did not suggest that it must be inhabited. In the Meteorologica he treats of such subjects as weather, rain, hail, earthquakes, etc., and their causes. He recognized that20 changes took place in the relations of land and sea. His knowledge of the origin and course of rivers and their relation to mountain systems was confused, and mainly erroneous; and it would seem that little progress had been made in geographical knowledge since the time of Herodotus. In the work of Aristotle’s successor, Theophrastus of Lesbos (c. 372–287), an important department of geographical study—that of distribution—finds a place in its particular application to plants.

Alexander the Great (356–323 B.C.), King of Macedon, however, during the last few years of his life, made possible by his campaigns a greater extension of Greek geographical knowledge than had taken place almost since Homeric times. When he passed eastward through Mesopotamia, by Babylon, Susa, and Persepolis, and through Media to the southern shore of the Caspian Sea, he was in a region which, though an ancient cradle of civilization, had been till then only vaguely known to the Greeks. Beyond that he entered new country, peopled by Herodotus and others with dubious tribal names. He came almost into the heart of Central Asia, founding a city on the upper course of the Jaxartes. Passing southwards through Bactria and across formidable ranges of mountains such as the Hindu Kush, he struck the upper course of the Indus, made his way down to its delta, and would have proceeded right into the heart of India and followed the Ganges to its mouth but for his mutinous troops. He returned through the north of Baluchistan and Persia to Ecbatana, and so homeward. He also sent a member of his staff, Nearchus, by sea along the coast of Baluchistan and Persia, in order to define it and to ascertain the extent of the Persian Gulf. Dicæarchus21 of Messana, a pupil of Aristotle, who died early in the third century B.C., used the geographical results of Alexander’s expeditions, including the distances obtained by his bematists, or measurers by pacing. Dicæarchus wrote a topography of Greece, and also drew on a map a parallel or equator, for the first time, so far as is known, along the length of the Mediterranean and, with a distorted idea of their relative directions, along the Taurus and Himalayan ranges. Before his time, and probably contemporaneously with Alexander’s campaigns, Pytheas of Massilia (Marseilles) visited (practically discovered) Britain, and made mention of Thule, six days’ voyage north of it, having perhaps heard of the Orkneys and Shetlands. As these islands, however, are at no such great distance as is here suggested from the nearest point of Britain, the name of Thule has been variously taken to represent some part of Norway, the Faeröe, or Iceland: it certainly seems by some later writers to be applied to Scandinavia, and in literary usage came to signify the uttermost north. Pytheas also obtained an idea of the Baltic Sea, and is considered by some to have entered it; he is stated to have reached the River Tanais; but if that is to be considered as one of the north European rivers, and not the known Tanais of the Black Sea basin, its identity is doubtful. Pytheas was a trained astronomer; he was one of the first to calculate latitudes, and had that of Massilia nearly correct; he heard of the unbroken summer daylight and winter darkness of the far north, and he noted various features of geographical interest, such as the decrease in the number of different grain crops observed as he travelled northward. He appears, in fact, from the references in other authors, which alone furnish22 us with knowledge of his work, in the light of a scientific traveller of a type rare in his time.

Mathematical geography was carried a long step forward by Eratosthenes (c. 276–194 B.C.), a native of Cyrene, who became chief librarian at Alexandria under Ptolemy III Euergetes. He calculated the circumference of the earth. He considered Syene to be situated on the tropic (which it was not, precisely), because at noon on the day of the summer solstice the sun appeared to shine directly down a deep well there. He therefore observed the zenith distance of the sun at Alexandria at the same time, and obtained his result from this and the measured distance between Alexandria and Syene. His result was to make the earth’s circumference only about one-seventh greater than it actually is. He also estimated the size of the habitable earth (œcumene), and considered it, as a result, to be about double as long from west to east as it was broad from north to south. But his estimate of the distance from what is now the extremity of Brittany to the known eastern limit of India was about one-third too great. On a map of the world he drew seven parallels, using the few points of which the latitudes had been worked out, and also seven meridians at irregular distances apart. Hipparchus (middle and second half of the second century), an astronomer, native of Nicæa in Bithynia, who worked in Rhodes, drew an elaborate series of parallels, and made the division into 360 degrees; the spaces between the lines he called climata, or zones. The problem presented by meridians was more difficult, for there was no instrument for the calculation of longitude like the gnomon for that of latitude. A well-recognised line was that taken to lie from the mouth of the Danube to that of the Nile—Herodotus23 had used this—and southward up the latter river; but not only the line itself, but also the ideas of intermediate points lying on it, were rather far from the truth.

Eratosthenes in his writings also dealt with the history of geography and with physical geography. This last branch attracted a number of students about this period and later, as, for example, Agartharchides or Agatharchus of Cnidus (middle of the second century B.C.). Crates of Mallus, in the first half of the same century, expressed the view of the Stoic philosophers that the spherical earth was divided into four inhabited quarters—the Œcumene (the known world), the Antipodes, the Periœci, and the Antœci. Posidonius the Stoic (c. 130–50 B.C.), among his studies in various departments of knowledge, included such subjects as the ocean, volcanoes, and earthquakes; he observed the interaction of the sun and moon in their influence on tides. He recalculated the circumference of the earth, but obtained an underestimate considerably further from the truth than Eratosthenes’s overestimate; and, owing to his high scientific reputation, his error persisted in much later work. Posidonius, before settling at Rhodes, had travelled widely in Africa, Spain, and western Europe generally; and both he and Agartharchides, like other writers of this period, and Aristotle before them, recognized the importance of the human side of geography, and the influence of physical environment on the political and social régime. Polybius (c. 204–122 B.C.) of Megalopolis in Arcadia, historian, statesman, and military commander, was inspired by extensive travel to introduce the results of topographical and geographical studies throughout his history. Among travellers who rank more nearly among24 explorers there may be mentioned at this period Eudoxus of Cyzicus (fl. c. 130 B.C.), who went on a trading expedition to India, in command of a fleet which was despatched by Ptolemy Euergetes of Egypt with the specific object of exploring the Arabian Sea. Eudoxus subsequently tried without success to circumnavigate Africa, making at least two voyages along the east coast. Finally, it must be remembered that at this period the extension of the knowledge of the world was mainly due no longer to Greek, but to Roman, activities, and Roman conquests were pushed beyond the confines of accurate Greek knowledge in various directions. Much geographical material was made available by writers on Roman military expeditions. Thus Pompey was accompanied in the Caucasian region by Theophanes of Mytilene, as historian of his campaigns; Julius Cæsar wrote his own account of lands into which he carried his arms (Gaul, etc.).

From all this it appears that, according to the lights of knowledge at the time, a fair conception existed of geographical study along the main lines which it follows to-day. There was therefore occasion for a general review of the whole subject; and this occasion was seized by Strabo, a native of Amasia in Pontus, who was born c. 63 B.C., and died in the second or third decade of the following century. He was educated partly at Rome, but his language and outlook were Greek. He travelled much, as far as Etruria, the Black Sea, and the borders of Ethiopia, as well as in Asia Minor, though he knew comparatively little of Greece. His geography, which was not finally completed till towards the close of his life, was the first attempt at covering the whole geographical field—mathematical, physical, and human—and his range was thus wider25 than that of Eratosthenes. Strabo used the recent Roman authorities to some extent, such as Cæsar’s Commentaries (in part) and a map of the Roman Empire by M. Vipsanius Agrippa, son-in-law of Augustus, which was set up in Rome; and he also preferred the authority of Polybius to that of Pytheas, but his sources were mostly Greek. His appreciation of them was not always wise. He ranked the Homeric poems highly, but discredited Herodotus, who on some points had better information than he. He added nothing to the mathematical branch, in which Eratosthenes was his master. He thus accepted the spherical form of the earth, its dimensions as laid down by his predecessors, and its division into five zones. He recognized Hipparchus’s view that further astronomical observations were essential to precision in earth-measurement and the position of points on the surface; but it was outside his province to add to those existing. His work in the physical field, however, improved upon that of his predecessors, and his surveys of the features and products of the various lands must have been singularly valuable for reference. The apportionment of the seventeen books of his geography is not without interest as a rough guide to the distribution of available material and to the author’s outlook. He devoted two books to introductory matter, to Spain and France two, to Italy two, to northern and eastern Europe one, to Greece and adjacent lands three, to the main divisions and remoter parts of Asia one, to Asia Minor three, to India and Persia one, to Syria and Arabia one, to Egypt and the rest of Africa one.

Rome did not carry on the Greek tradition of the study of geographical theory. H. F. Tozer, quoting J. Partsch, writes: “It has been aptly remarked that26 the task which Eratosthenes set himself of measuring the earth by means of the heavenly bodies, and that of Agrippa, who measured the Roman provinces by milestones, may be taken as typical of the genius of the two nationalities respectively.” Thus Pomponius Mela, purporting to survey the world in his De Chorographia (written c. 50 A.D.), followed the coast and described various countries in passing, but by no means all, and added very little to geographical knowledge at large. Pliny the Elder (c. 23–79) devoted three books and part of another of his Historia Naturalis to geography; but his geography may (at least in considerable part) be compared with the arid text-book of a generation ago, though in some instances his descriptions (as of features in Palestine, Syria, and Armenia) are valuable. As bearing on the quotation made above, it may be said here that the famous Roman system of road building gave rise to two classes of road-books (as they may be termed), one consisting of lists of stations and distances, such as the Antonine Itinerary (probably, in its original form, of the late third or fourth century), the other diagrammatic, such as the Peutinger Table (probably of the first half of the third century, though named after a scholar of the sixteenth), on which roads, stations, and other details were presented in a map-like form, but independently of true scale or direction. The Roman agrimensores were skilled surveyors.

It is not, then, surprising that the two great theoretical geographers next to be considered are not associated with the capital of the Roman Empire. Of the work of Marinus of Tyre nothing is known beyond what is recorded by his immediate successor, Ptolemy, who used and acknowledged his results—as far as concerned the Mediterranean fully, and in respect of other27 countries to a modified extent. Ptolemy, mathematician, astronomer, and geographer, was a native of Egypt, who worked at or in the neighbourhood of Alexandria in the second century. His geographical book was called Geographike Syntaxis. He carried mathematical geography far beyond the standard of his predecessors. He used the theoretical division of the globe into five zones by the equator and the tropics, adopted Hipparchus’s division of the equator into 360 degrees, and worked out a network of parallels of latitude and meridians of longitude, first thus applying these terms in their technical sense. In mapping the habitable world he used the Fortunate Isles, beyond the western confines of Europe and Africa, as the location of his prime meridian. The errors which resulted from the vague idea as to the position of these islands (the Canaries and Madeira), and from the fact that Ptolemy followed Posidonius’s underestimate of the circumference of the globe and made his degree at the equator equal to 500 instead of 600 stadia,2 have been very fully analysed, but cannot be even summarized here.

2 Fifty instead of sixty geographical miles.

28

PTOLEMÆUS ROMÆ 1490.

Fig. 4.—The World according to Ptolemy.

Ptolemy had a strong tendency to exaggerate the size of the great land-masses—his Europe extended too far west (and the Mediterranean was made too long in consequence); his Africa was too wide, especially towards the south; his Asia was vastly exaggerated in its eastern extension, and many details, even in the Mediterranean area, were made too large. Ptolemy followed his predecessors in using the parallel of 36° N. as the axial line of the Mediterranean. It passes through the Straits of Gibraltar, the island of Rhodes, and the Gulf of Alexandria, and was theoretically prolonged30 eastward along the supposed line of the Taurus mountains and the range known to lie north of India. In respect to this line there were remarkable inaccuracies in laying down the coasts of the Mediterranean and in fixing the position of the points upon them. The sea itself was made not only too long, but too broad; Byzantium and the Black Sea were carried too far north, and the size of the sea of Azov was immensely exaggerated. On the other hand, Ptolemy restored the correct view, held by Herodotus, of the Caspian as an inland sea, and knew that the great river Volga entered it. Yet again, he knew nothing of Scandinavia, or of the land-locked Baltic Sea, marking only a small island of Scandia, possibly by confusion between the Scandinavian mainland and some Baltic island. But his idea of the British Isles may be taken as fairly correct, if allowance be made for their remoteness. He laid down some parts of the coast very fairly, but oriented the major axis of Scotland more nearly from east to west than from north to south; he also placed Ireland wholly more northerly than Wales. There is plenty of evidence in Ptolemy’s work of a growth of knowledge of remote lands, though much of it is vague, if not actually unintelligible to us. Thus in Asia he had an idea of the great central mountain ranges (Pamir, Tian-shan, etc.), for silk-traders had by now established trans-continental routes to China. Ptolemy had also some conception of the south-eastern coasts, which had probably been seen by Greek mariners as far as southern China. But he wholly misunderstood the form of the east of the continent, for beyond the Golden Chersonese (Malay Peninsula) there lies a vast gulf, the eastern shore of which represents his view of China, extending southward far beyond the31 equator, and facing west. Again, he had no conception of peninsular India—unless, indeed, his huge island of Ceylon (Taprobane) was drawn so by some confusion with the peninsula, as it was certainly also confused with Sumatra. Yet it would seem that he might have gathered a more accurate idea of India from the Periplus of the Erythræan Sea, a guide to navigators dated about the year 80. This work furnished sailing directions from the Red Sea to the mouth of the Indus and the coast of Malabar, following the Arabian coast, although the possibility of crossing the open sea with the assistance of the monsoon was realized at a still earlier date. And the Periplus distinctly indicates the southward trend of the Indian coast-line.

Roman penetration of Africa gave Ptolemy some new details; he also conceived the Nile as formed by two headstreams arising in two lakes, possibly on the strength of some hearsay of the facts, and he marked the Mountains of the Moon in remoter Africa, which again suggests hearsay of the heights of Ruwenzori, Kenya, and others. The Romans had penetrated Ethiopia, and possibly the region of Lake Chad, and Ptolemy also used other sources of information about North Africa which are unknown from previous writers, but are completely vague and impossible to follow. Of the shape of the continent he was almost completely ignorant; he just realized that an indentation occurs in the Gulf of Guinea, but gave it nothing like its proper value, and carried the coast thence south-westward till the continent is broader at the southern limit of his knowledge than it is at the north.

Ptolemy’s work on physical features was on the whole poor, and he neglected the human side of geography. Discarding the idea of the circumfluent ocean,32 he supposed the extension of unknown lands northward in Europe, eastward in Asia, and southward in Africa, beyond the limits in which he attempted to portray their outlines; and he even suggested a land connection between south-eastern Asia and southern Africa. Before his time the precision of mathematical method had far surpassed that of the topographical material to which it was applied.

Pausanias, a Greek probably of Lydia and about contemporary with Ptolemy, wrote a description (Periegesis) of Greece, which, apart from the archæological value which is its chief interest, contains references to various phenomena of physical geography, while as a detailed topographical work it stands alone in the literature of which an outline has thus far been given.

33

From this point it becomes necessary to vary the treatment of our subject hitherto followed. With the breakup of the Roman Empire and the establishment of Christianity the old learning was obliterated. Religion became the central fact of intellectual exercise, and, except in so far as Christian doctrine and Holy Scripture involved reference to natural phenomena, every branch of natural science was withered by the breath of theology. The first serious assaults of the barbarian invader were made on the frontiers of the Roman Empire in the fourth century A.D.; in 330 the seat of government was transferred from Rome to Byzantium, and at the close of the century the empire was divided into eastern and western parts. It has often been pointed out that these events did more than mark the beginning of the disruption of the Roman Empire; they also mark the parting of the ways of eastern and western European religion and culture. In the west it became the function of Christianity to teach and civilize peoples untaught and uncivilized; but, limited and intolerant as was its outlook upon natural science generally, it discarded the learning of the pre-Christian era. We have now to inquire how geography was affected by this attitude towards secular learning.

It is true that the habit of travel, so far from being forgotten, was even fostered by missionary work and34 the practice of pilgrimage. Again, opportunities for the extension of geographical knowledge were provided by various episodes in the history of the centuries with which we are now concerned; thus Procopius, the historian of the Persian, Vandal, and Gothic wars of the epoch of the Roman (Byzantine) emperor Justinian in the sixth century, had ample opportunities for geographical description and used them well. Justinian even despatched an expedition to China (which returned thence). But the geographical theorists of the period now under review had little if any concern with contemporary travellers’ results.

The Christian cosmographers, having found in a spiritual sense a new heaven and a new earth, were at pains to create them in a scientific sense also. It was their aim to reconcile geographical theory with the literal sense of Holy Scripture, and they were not only unable to explain, but were (for the most part) willing to disprove, pre-Christian theory by that light. Thus Lactantius Firmianus (c. 260–340), becoming converted, denied the possibility of the sphericity of the earth or the existence of antipodes. On the other hand, this conception died hard, for it was maintained by pagan writers at this time—as, for instance, Martianus Capella, who, writing in the third or fourth century, followed such authorities as Ptolemy and Pythagoras. And these pre-Christian views must have caused some of the Christian authors to doubt, for they left unsettled such questions as that of the earth’s shape, on the plea that they formed no part of the Christian doctrine; an instance of this attitude is provided by St. Basil the Great of Cæsarea (c. 330–379) in his treatise on the Hexaemeron (Six Days of the Creation).

One of the principal popular attractions of geography35 has always been its function of describing the wonders of distant lands, and in Julius Solinus Polyhistor (probably of the third century) we have a typical geographer of the marvellous, who in his Collectanea Rerum Memorabilium drew upon Pliny, Pomponius Mela, and many earlier authors for a description of the wonders of the world, and became himself regarded as a high authority. With such influences at work on the study of geography, the genesis of the theories of Cosmas Indicopleustes becomes perhaps less surprising than the theories themselves. He was a merchant of Alexandria, and a traveller (as his surname is inaccurately intended to record) in the Red Sea and the ocean beyond, who, thus fortified in geographical study, became a monk and wrote his Christian Topography about the middle of the sixth century, in opposition to36 the pre-Christian theories. Under his pen the inhabited earth became a flat, rectangular oblong surrounded by oceans. At the north is a conical mountain round which the sun (which is some forty miles in diameter and at no great distance from the earth) revolves, passing about the summit in summer, so that it is hidden from the earth for a shorter time daily than in the winter, when it passes about the base. Again, in such conditions as have been indicated, it is at least intelligible that a responsible writer should accept a mountain 250 miles high, as is stated of Mount Pelion by Dicuil, an Irish monastic scholar who completed his De Mensura Orbis Terræ in 825. He, however, was little else than a compiler, and in the manner of his kind made an ill choice of sources. Among them, however, he refers to surveys made by Julius Cæsar, Augustus, and one of the emperors Theodosius; the originals thus referred to are unknown. To mention the various Churchmen and others who, though in no sense geographers, were expected to deal with the theories of the earth and the universe in connection with their religious doctrines, would make but a tedious list.

The view of the sphericity of the earth was not wholly lost. Certain expressions of the Venerable Bede (c. 672–735), even if he did not specifically formulate the theory, were capable of that construction, although in 741 we find Virgilius, the Irish bishop of Salzburg, attacked by the Pope for his assertion of the existence of antipodes (or at least an assertion that may bear that construction). Nevertheless, these theories made headway, and from the eleventh century they became more and more acceptable to leaders of learning. Adam of Bremen accepted them; he is also an important37 figure in other departments of geography. He flourished in the second half of the eleventh century; his history is a specially valuable authority for the Baltic lands and other parts of Scandinavia and Russia. Its fourth book is a Descriptio Insularum Aquilonis, for which there was no little material, for not only had holy men from Ireland visited the Orkneys, Shetlands, Faeröe, and Iceland in the sixth and seventh centuries, but the Norsemen had entered upon their period of colonizing activity; besides Great Britain and Ireland they had reached Iceland in 874, Greenland a century later, and Vinland in 1000; and this last, that much-debated3 landfall situated somewhere on the North American coast south-west of Greenland, is first mentioned by Adam of Bremen. A similar appreciation of north European geography had been shown by King Alfred the Great, who in translating (and freely editing) earlier works had introduced much of the knowledge acquired down to his own time.

3 Not only so in modern times; at least one Scandinavian geographer, of the end of the thirteenth century, was prepared to recognize it as belonging to Africa.

Monastic cartography did not keep pace with theory. The disputed habitable land beyond the confines of the known world, and separated from it by the impassable torrid zone (a classical conception), appeared in maps of the seventh and eighth centuries. Apart from this (and it came to be generally admitted) we have rectangular oblong maps like that of Cosmas, and circular maps, out of which was evolved the diagrammatic form of a T within an O, where the T represented the Mediterranean, the Tanais, and the Nile, its upright showing the westward extension of the sea, and the cross-stroke the two rivers, to left and right3839 respectively, so that the west was at the bottom of the map. Europe lay within the left-hand angle of the T, Africa in the right-hand angle; Asia was the half circle above it. The holy city of Jerusalem lay “in the midst of the nations.” Some maps, again, gave the earth an oval form. In all, the habitable earth was still surrounded by ocean. In the far east sometimes appeared Paradise. This feature and the unknown habitable world above mentioned were both shown in the map of Beatus, a Spanish priest (c. 730–798), who illustrated his Commentaria in Apocalypsin with one of the earliest known Christian maps of the world, several copies of which, dating from the tenth to the thirteenth centuries, are preserved. In this map the “known” habitable world appears as a dome-shaped mass with its flat base to the south, forming the northern shore of a strait separating it from the unknown southern land. The known world is broken for more than half its breadth by the vast gulf of the Mediterranean, which has two great arms reaching far northward; the Caspian Sea is a gulf opening into the north-east part of the circumfluent ocean, in which are set islands in an orderly ring all round the world; all sense of direction in the flow of rivers is awry, and topographical accuracy is, of course, entirely wanting.

What early Christianity lost by looking askance at classical theory the Arabs, after the establishment of Muhammadan power in the seventh century, in great measure gained, for they were free of scruple as regarded the earlier learning, and eager for knowledge. Early in the ninth century the Caliph Al-Mamun of Bagdad gave a strong impulse to geographical and kindred studies. He caused translations to be made of Ptolemy’s astronomical and geographical works,40 and of those of other ancient authorities, among whom was Marinus of Tyre. Muhammad ben Musa, librarian of Bagdad, compiled a Description of the World, or gazetteer of place-names with their positions, on the Ptolemaic model. Degrees were measured in Syria and Mesopotamia. Among Arab descriptive works the first which survives is that of Suleiman, a merchant, who made voyages to India and China in the middle of the ninth century. In the first half of the following century Masudi travelled widely—to India and Ceylon, probably to China, to Madagascar, to the Caspian, and in Syria and Egypt. His work, the Meadows of Gold and Mines of Precious Stones, is an example of the application of the results of travel and personal observation to history; he was commonly compared with Pliny. The Muhammadan demand for geographical works at this period appears to have been great, from the fact that Abu Zaid’s work, written about 921, was revised thirty years later by Istakhri, who travelled all through the Muhammadan lands, in his Book of Climates (or Zones); and this was again revised and extended by Ibn Haukal in 977 in his Book of Roads and Kingdoms.

A more important figure is Idrisi (c. 1099–1154), an Arab of Spanish birth, who was probably educated at the great centre of learning, Cordova. He travelled in North Africa and Asia Minor, and, settling in Sicily, made a celestial sphere and a map of the world in silver for King Roger II. Idrisi conceived a substitute for a projection by dividing the inhabited world into seven climates or zones between the equatorial line and the arctic region; each of these was divided into eleven equal parts by perpendicular lines. The squares thus formed were used (to the disregard of natural or41 political divisions) in a description of the earth carried out by Idrisi for the king, which is noteworthy as having been put together, at least in part, from the reports of an organized system of observers, who were despatched at Roger’s order to various countries. Arabian cartography, however, so far as is known, was primitive. Yet the Arab astronomers made some close meridianal determinations—an error of only three degrees between Toledo and Bagdad, for example, and a calculation of the major axis of the Mediterranean which was very near the truth.

Before leaving this period it is worth remarking how commercial activity had not only developed within, but had circumscribed the European area. The Arabs, penetrating eastward into Asia, came in contact with traders from north and western Europe using a route which, from the eighth century, passed “from India through Novgorod to the Baltic; and Arab coins found in Sweden prove how closely the enterprise of the Arabs and the Northmen intertwined” (H. R. Mill). Thus ways were prepared for the advancement of geographical knowledge when the science should emerge from its stagnation.

42

It was, in fact, a desire to extend both commerce and Christian religion into the far eastern lands which led to the rescue of geographical study from the evil state into which it had fallen. The Crusades form a group of incidents of no less geographical than of historical importance. Apart from their religious significance, they were undertaken with the object of discovering new routes by which the wealth of the east could be brought into commercial exchange with that of the west; and in connection with their religious significance they gave rise to a period of Christian missionary endeavour in the east. Both movements worked together to bring about the result of a discovery of Asia, so far as Europe was concerned, only less novel and important than the discovery of the New World by Columbus and his successors. Of the many travellers whose records assisted in this discovery a few may be mentioned as examples. The first whose journeys resulted in a noteworthy addition to knowledge of the Mongol Empire was Joannes de Plano Carpini, an Italian of Umbria, who led a catholic mission sent in 1245 by Pope Innocent IV to the Mongols shortly after their great invasion of eastern Europe. He was followed in 1253–55 by William of Rubruquis, a Franciscan, who was sent to Tartary by King Louis IX, and whose account is in many respects more valuable43 than that of Carpini. We may turn aside here to remark that the great philosopher, Roger Bacon (c. 1214–94), freely quoted Rubruquis in the geographical section of his Opus Majus. This work, and that of Albertus Magnus of Swabia (c. 1206–80), the student of Aristotle, exemplify the revival of interest in geographical theory along lines not dictated by Christian in opposition to pagan doctrines. Bacon revived Aristotle’s opinions as to the spherical form of the earth. He held that the sea did not cover three quarters of the globe, and that there must needs be lands unknown, to the south, east, and west of the known world, from which they must be separated only by narrow waters.

A traveller who followed new lines on the return of his expedition to the east was Hayton, King of Lesser Armenia, in 1224–69, whose journey was described by a member of his retinue. It led him (returning) through the Urumtsi region and the Ili valley, the neighbourhood of the modern Kulja and Aulie-ata, the Syr-darya valley, Samarkand, Bokhara, Merv, and northern Persia. Next follows the greatest name among the eastern travellers of this period, and one of the greatest among all; that of the Venetian Marco Polo (c. 1254–1324). His father Nicolo and his uncle Maffeo had travelled, before his birth, to China and established friendly relations with Kublai Khan. That ruler sent them back to Europe to ask the Pope to despatch a large embassy to his court, for he was anxious to extend his relations with the western world and his knowledge of western life. There was a long delay owing to an interregnum in the papacy, nor were the brothers able to obtain the large following the Khan had desired; but they started back to China themselves in 1271, and Marco accompanied them. They44 proceeded by way of Badakshan, the Pamirs, Kashgar, Yarkand, Khotan, Lop-nor (where they covered ground not again travelled by a European for five centuries), and the desert of Gobi. Marco Polo rose in favour at the court of the Khan. Among many activities he was employed on a mission to the Indies, and no opportunity arose for him to return home until 1292. He was then sent to accompany a Persian embassy on its return journey by sea, by way of Sumatra and India. The journey entailed long delays, and Marco only reached Venice in 1295. He subsequently dictated his experiences while a captive in Genoa, having been taken prisoner in a naval encounter between Genoa and Venice at Curzola in 1298. They were taken down by a fellow-captive of literary ability, Rusticiano of Pisa. His geographical achievements have been thus summarized4:—

4 Yule and Beazley’s article on “Polo” in Ency. Brit. (11th ed.), vol. xxii.

Polo was the first traveller to trace a route across the whole longitude of Asia, naming and describing kingdom after kingdom which he had seen; the first to speak of the new and brilliant court which had been established at Peking; the first to reveal China in all its wealth and vastness, and to tell of the nations on its borders; the first to tell more of Tibet than its name, to speak of Burma, of Laos, of Siam, of Cochin-China, of Japan, of Java, of Sumatra and other islands of the archipelago, of the Nicobar and Andaman Islands, of Ceylon and its sacred peak, of India but as a country seen and partially explored; the first in mediæval times to give any distinct account of the secluded Christian empire of Abyssinia, and of the semi-Christian island of Sokotra, and to speak, however dimly, of Zanzibar, and of the vast and distant Madagascar; while he carries us also to the remotely opposite region of Siberia and the Arctic shores, to speak of dog-sledges, white bears, and reindeer-riding Tunguses.

45 Among Polo’s successors were John of Montecorvino (c. 1247–1328), a Franciscan, who became Archbishop of Peking, and wrote the first valuable account of the Coromandel coast of India about 1291; and Jordanus, a French Dominican, who, having carried Catholicism into India about 1320, improved even upon Polo’s account of the general geography, climate, and products of the peninsula. Another Franciscan who was also a skilled observer both in China and India was Odoric of Pordenone (c. 1236–81).

It may be worth recalling the difficulties which stood in the way of immediately making use of the work of travellers and students at this period. Printing was not to come into use in Europe for a century yet. Scribes, no doubt, tended to pay most attention to works of the most popular sort, and it is, therefore, no matter for wonder if the works of conscientious travellers, such as we have been describing, did not obtain anything like a wide circulation within a short period of their production. On the other hand, a work which did obtain very wide favour, judged by the standard of the time, was that much-discussed account of wholly, or very largely, imaginary experiences and wonders which appeared first in French about 1357–71 under the name of Jean de Mandeville, or, in the more familiar English form, Sir John Mandeville. This is an account in the nature of a parody of the work of Odoric and other eastern travellers, in the sense that the writer took their facts and substituted or superimposed his own fictions. It is a matter for discussion how far his work was based, if it were based at all, on independent travel and research; yet it contains something of interest to students of the history of geography, if only as an opportunity for the exercise of their imagination—as,46 for example, when the writer tells a story of a man who started forth from his home and travelled always eastward, until at last he reached it again, thus encircling the globe. The difficulties in the way of disseminating knowledge will similarly account for the fact that, although the great Arab traveller Ibn Batuta has his place in this period, he in no way affected European geographical study. He was a native of Tangier (1304–78), who occupied thirty years of his life in travel, covering extraordinary distances in west, south, and east Asia, and in Africa, and wrote valuable accounts. Egypt, Arabia, and Palestine, Syria, Asia Minor, and Persia, the territories north of the Black Sea and the Caspian, were all well known to this wanderer, who also sailed through the Red Sea and along the East African coast, visited many parts of India, the Maldive Islands, Ceylon, Sumatra, and China, and closed his career as a traveller with journeys through Spain and across the Sahara to Timbuktu. His journeys are estimated to have amounted to more than 75,000 miles. Modern criticism has proved the remarkable accuracy of his descriptions of many lands and places; but they were unknown to contemporary Europe, and, indeed, until the last century.

It may be said that if a traveller’s results did immediately come to be quoted as authoritative, it was in a measure accidental. We have already mentioned the use of the results of Rubruquis by his brother Franciscan, Roger Bacon; but Marco Polo’s results, for example, do not appear to have had any influence on cartography for about half-a-century. An excellent example of mediæval cartography, before these results and others like them began to show their influence on maps, is provided by the celebrated map preserved in Hereford4748 Cathedral, made about 1280 by Richard of Haldingham. Here is the world still shown as a round disk, with little conception of the form of the Mediterranean and its branch seas; while even the British Isles and north-west Europe are strangely distorted to fit the circle. Such is an illustration of the conception of the world still existing in western Europe. Few maps of special areas survive from this period, but that of Great Britain accompanying the work of the famous historical writer Matthew Paris (1259) is an example. It reveals, on the whole, a better idea of the internal features of the land than of its coasts and its shape, which somewhat resembles a fool’s-cap. There are also local maps of Palestine; and that country, it may be added here, is the subject of the earliest extant Christian map, in the form of a mosaic on the floor of a church in Madaba, in Syria: it dates from the sixth century. The Crusades would naturally give rise to a demand for maps of Palestine, and they also gave rise to a class of work which may be compared to the modern guide-book.

But among maps of special regions the most notable are those known as Portolano maps, which were sailing charts accompanying the Portolani, or sailing directions for the Mediterranean Sea. These, no doubt, existed long before the Crusades, in connection with which they first come to our knowledge. They are in most respects remarkably accurate. They are distinguished by groups of rhumb-lines radiating from a series of centres, and marked usually with the initials of the names of the principal winds. As the accuracy of these maps was probably improved largely as the mariners’ compass came into use, it may be mentioned that the first European notice of the use of that instrument is provided by the English scientist Alexander49 Neckam (1157–1217) of St. Albans, foster brother to King Richard I. From his mention it appears by this time to have been a familiar object. The chief centres for the production of Portolano maps were naturally those identified in an important degree with over-sea commerce; such were Genoa, Venice, Ancona, and Majorca, while the seamen of Catalonia were also prominent at this period. These maps were in some cases extended to cover lands and seas beyond the immediate Mediterranean area, and even the whole world. World maps were usually circular with Jerusalem as a centre, and, in contrast to their accuracy in respect of the Mediterranean, they were not distinguished as a rule for much regard to the best sources of information, though for that we have already adduced some measure of excuse. The map of the world by Petrus Vesconte of Genoa (c. 1320) shows the Mediterranean and the Black Seas well, the Nile fairly, the Caspian indifferently, Scandinavia badly. A50 mountain range extends west and east across almost the whole of northern Europe and central Asia; rivers drain southward to the Black Sea from this; the Indian Ocean appears as a gulf; the south-eastward extension of the African coast is retained, and the peninsular form of India is not realized. Subsequent cartographers disagreed on such points as this last. Thus in a Florentine map of about 1350, called the Laurentian or Medicean Portolano, the west coast of India is well shown, and the influence of Marco Polo’s travels is to some degree apparent. This map, moreover, has other details of interest, such as the first appearance in any known map of the Azores and the islands of Madeira with their modern names. The Catalan map of 1375 recognizes the peninsular form of India for the first time, and Marco Polo’s results are shown to be thoroughly appreciated; and yet a century later the old errors as to the form of India and Ceylon persist even in a map so excellent in many directions as that of Fra Mauro (1457).

51

There were obvious geographical and historical reasons why the kingdom of Portugal should furnish the important series of incidents in the expansion of geographical knowledge which now claims attention. The Arab power in the Iberian peninsula had been broken, and the Portuguese monarchy had established itself during the twelfth century. The Arab mantle of the explorer descended upon Portuguese shoulders. The small kingdom has a large extent of coastline; and not only is communication with Europe by land through the passes at either end of the Pyrenees comparatively difficult, but between those passes and Portugal were Spanish states, with which Portuguese relations were by no means amicable. Thus there was little opportunity for the commercial expansion of Portugal except over-seas.