DEPARTURE OF THE ORPHAN.

Engraved for Godey's Lady's Book.

Title: Godey's Lady's Book, Vol. 48, No. XVIII, April, 1854

Author: Various

Editor: Sarah Josepha Buell Hale

Release date: December 19, 2018 [eBook #58494]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Jane Robins and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

The TABLE OF CONTENTS Table has been harvested from the January Edition.

| A Mother's Love, by Mary Neal, | 355 |

| Appletons', | 380 |

| Apron in Broderie en Lacet, | 363 |

| Beauty, by Miss M. H. Butt, | 346 |

| Border and Corner for Pocket-Handkerchief, | 361 |

| Camilla Mantilla, | 289 |

| Caps, | 362 |

| Celestial Phenomena, by D. W. Belisle, | 315 |

| Centre-Table Gossip, | 379 |

| Chemisettes, | 362 |

| Cottage Furniture, | 364 |

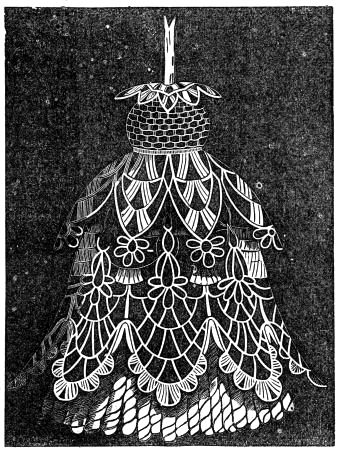

| Crochet Tassel Cover, | 358 |

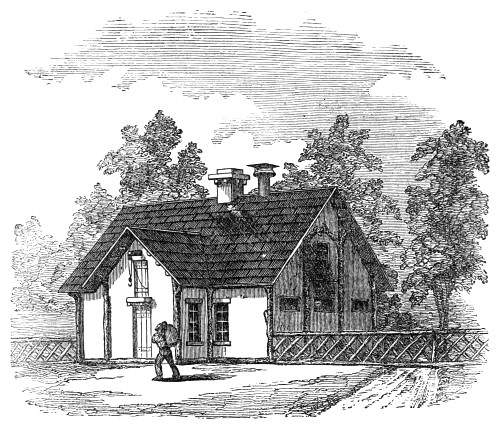

| Dairy-House and Piggery, | 349 |

| Don't Overtask the Young Brain, | 337 |

| Dream Picture, by Mrs. A. F. Law, | 353 |

| Dress--as a Fine Art, by Mrs. Merrifield, | 347 |

| Editors' Table, | 366 |

| Ellie Maylie, by Jennie Dowling De Witt, | 353 |

| Enigmas, | 377 |

| Eugenie Costume, | 292 |

| Fashions, | 381 |

| Godey's Arm-Chair, | 371 |

| Godey's Course of Lessons in Drawing, | 323 |

| I was Robbed of my Spirit's Love, by Jaronette, | 354 |

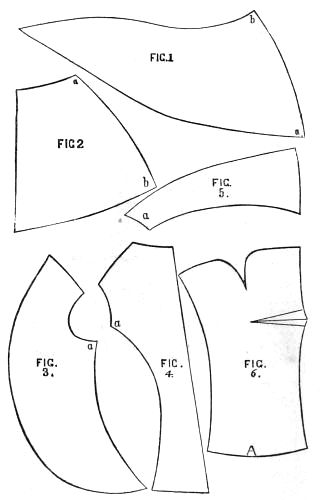

| Jacket for Riding-Dress, | 364 |

| Laces and Embroideries, | 379 |

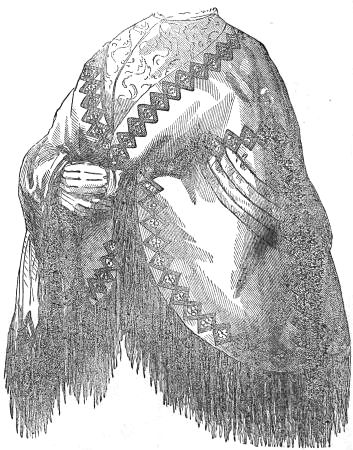

| Lady's Scarf Mantelet, | 357 |

| Lady's Slipper, | 363 |

| Le Printemps Mantilla, | 289 |

| Letters Left at the Pastry Cook's, Edited by Horace Mayhew, | 334 |

| Literary Notices, | 369 |

| Management of Canary Birds, | 322 |

| Mantillas, from the celebrated Establishment of G. Brodie, New York, | 290, 291 |

| Manuel Garcia, the celebrated Singing-Master, | 366 |

| Mrs. Murden's Two Dollar Silk, by The Author of "Miss Bremer's Visit to Cooper's Landing," | 317 |

| Netted Cap, for morning wear, | 360 |

| Our Practical Dress Instructor, | 357 |

| Patterns for Embroidery, | 365 |

| Receipts, &c., | 378 |

| Singular Inscriptions on Tombstones, | 376 |

| Some Thoughts on Training Female Teachers, by Miss M. S. G., | 336 |

| Sonnets, by Wm. Alexander, | 352 |

| Spring Bonnets, | 294 |

| The Borrower's Department, | 377 |

| The Elixir of Life, by Charles Albert Janvier, | 354 |

| The Household, | 379 |

| The Interview, by T. Hempstead, | 352 |

| The Last Moments, by R. Griffin Staples, | 356 |

| The Manufacture of Artificial Flowers, by C. T. Hinckley, | 295 |

| The Orphan's Departure, by Margaret Floyd, | 310 |

| There's Music, by Horace G. Boughman, | 353 |

| The Song-Birds of Spring, by Norman W. Bridge, | 355 |

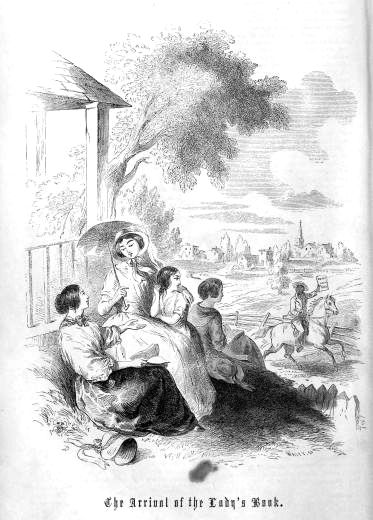

| The Souvenir; or, The Arrival of the Lady's Book. A Sketch of Southern Life, by Pauline Forsyth, | 338 |

| The Toilet, | 382 |

| The Trials of a Needle-Woman, by T. S. Arthur, | 326 |

| The Turkish Costume, | 348 |

| The Was and the Is, by O. Everts, M. D., | 356 |

| The Wild Flowers of Early Spring-time, | 343 |

| To an Absent Dear One, by Fannie M. C., | 355 |

| To Ida, by Horace Phelps, M. D., | 356 |

| True Happiness in a Palace, | 367 |

| Undersleeves, | 362 |

| Washing made Easy, | 379 |

| Willie Maylie, by Cornelia M. Dowling, | 353 |

| Zanotti: a Romantic Tale of Italy and Spain, by Percy, | 300 |

DEPARTURE OF THE ORPHAN.

Engraved for Godey's Lady's Book.

CAMILLA MANTILLA.—Light green silk, trimmed with Honiton lace.

LE PRINTEMPS MANTILLA.—Lavender or pearl-colored silk. The yoke and point cut in one piece. The trimming is a rich fringe of the same color.

THE COLUMBINE.

[From the establishment of G. BRODIE, No. 51 Canal Street, New York.]

FOR the early portion of the season, we illustrate a mantilla of great beauty. It is made of black-green or ruby-colored, with a richly embroidered ornamental design. Should it prove desirable, the upper portion of the garment may be left off, and the lower alone worn. The mantilla is trimmed with a netted fringe, seven inches wide.

THE SNOWDROP.

[From the establishment of G. BRODIE, No. 51 Canal Street, New York.]

FOR the close of this month and the early summer, we present a mantilla which shares largely the public favor. This garment has appeared elsewhere before, somewhat in advance of its time; but, as we desire to present accurate reports of what are actually the reigning modes, we publish it here for the benefit of our lady friends. It is in the berthe style, composed of white poult de soie, heavily embroidered. The collar is slashed upon the shoulder, and cross-laced with cords terminating in neat tassels. It is fringed with extraordinary richness.

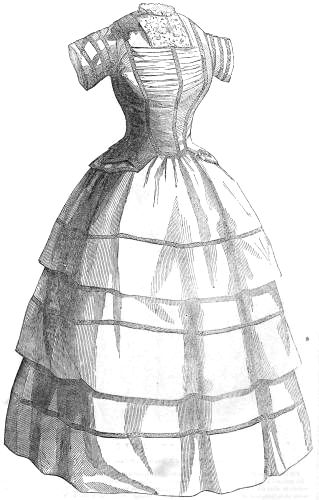

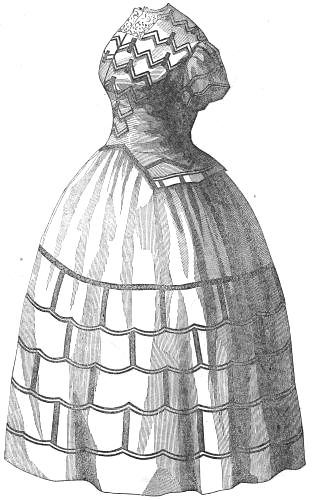

EUGENIE COSTUME.

DESIGNED, BY MRS. SUPLEE, EXPRESSLY FOR GODEY'S LADY'S BOOK.

Suitable for the coming season. Material.—Brilliante or lawn. The corsage is cut square and full, and trimmed with inserting and edging. The skirt has a hem and two tucks, each six inches deep, trimmed as above.

L'ANGLAISE.

DESIGNED, BY MRS. SUPLEE, EXPRESSLY FOR GODEY'S LADY'S BOOK.

Material.—Tissue, barège or silk. Five folds on the skirt, each five inches deep. Scallops trimmed with No. 1½ ribbon. Looped up at intervals with No. 3 ribbon, as in plate; the ribbons to suit the colors in the dress. Corsage the same.

Gimp or braid is to be used with silk.

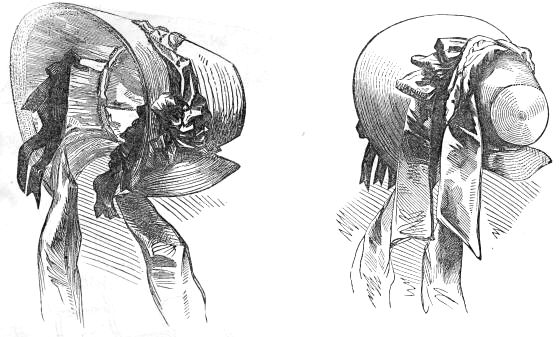

SPRING BONNET.

THIS bonnet, which is suited to a plain walking-dress, is made of straw, and trimmed with Leghorn-colored ribbon, disposed in a simple and tasteful style, with two long flowing ends on the left side. The bonnet is lined with white ærophane, laid in small neat folds; and the under-trimming consists of loops of black velvet ribbon. The second figure is the reverse side of the same bonnet.

PHILADELPHIA, APRIL, 1854.

ILLUSTRATED WITH PEN AND GRAVER.

BY C. T. HINCKLEY.

THE manufacture of artificial flowers, first brought to a high degree of excellence by the Italians, is one of no small importance, considering the amount of skill and labor which it brings into requisition. The first attempt at making artificial flowers among civilized nations was by twisting ribbons of different colors somewhat into the shape of flowers, and fastening them to wire stems. This yielded to the use of feathers, which were far more elegant, but could not always be made to imitate in color the flowers which they represented, there being considerable difficulty in getting them to take the dyes. Where the plumage of birds is of great brilliancy, the natural colors admirably answer the purpose, and do not fade or lose their resplendent hues. Thus, in South America, the savages have long known how to fabricate beautiful artificial flowers from such plumage. In Italy, the cocoons of silkworms are often used, and have a soft and velvety appearance, while they take a brilliant dye. In France, the finest cambric is the chief material, while wax is also largely employed. The arrangement of the workshop, and the variety and use of tools, where flower-making is practised on a large scale, are as follows:—

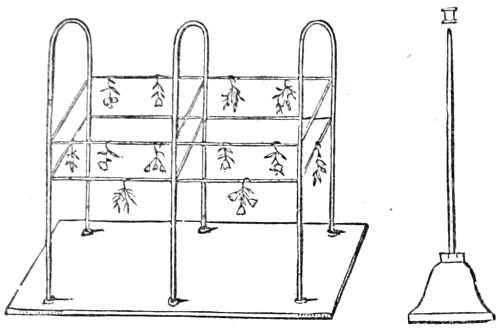

Fig. 1.

A large and well-lighted room, which has the means of warmth in winter, is selected, and along its whole extent is placed a table, similar to the writing-tables used in schools, where the work-people may have a good light as long as possible. This table is fitted with drawers containing numerous compartments, arranged so as to receive and keep separate the small parts of flowers, such as petals, stalks, minute blossoms catkins, buds, leaves not mounted on their stalks and all other parts not fit to be placed among more finished specimens. It is desirable that the table be covered with oil-cloth, so that it may be frequently cleansed, by washing, from the stains of the different colors employed. Along the whole extent of this table are placed flower-holders, that is, light frames with horizontal iron wires, to which the flowers, when attached to their stalks, are suspended by merely crooking the end of the stalk, and hanging it on the wire. Sometimes tightly strained pack-thread is used instead of wire. Figs. 1 and 2 represent two forms of flower-holder; in both cases the frame is fixed to the table. Along the tables are also ranged bobbin-holders in considerable numbers, not unlike those used by weavers. The bobbin-holder is a rod of iron, Fig. 3, about six inches high, fixed in a massive leaden or wooden base. On this rod is threaded a large bobbin, on which is wound a quantity of silk[296] or wool. On its summit may be fixed a nut, to prevent the bobbin, when in rapid motion, from whirling off the rod, but this is often omitted. Ladies who work for their pleasure frequently have this bobbin-holder made in an ornamental form, the base being covered with bas-reliefs, and the nut at the top taking the form of an arrow, a blossom, &c. But the more simple and free from ornament, the better is the holder for use, any unnecessary projections only acting as so many means of entangling the silk.

Fig. 2. Fig. 3.

Fig. 4.

The flower-maker does not take up flowers or their parts with the fingers, but with pincers of the simplest description, Fig. 4, which are incessantly in use. With these, the smallest parts of the flower can be seized, and disposed in their proper places, raised, depressed, turned about and adjusted, according to the taste of the artist, and her appreciation of natural forms. It is with the pincers also that any little contortions of the extremities of petals, and irregularities in their form and in the arrangement of stamens, are copied. The proper length of this tool is about five inches. Each workwoman brings one for her own use, and keeps it close at hand. Dressing-frames of various sizes form another part of the furniture of the work-room. On these are stretched the materials, which are gummed and dyed. A dressing-frame, Fig. 5, consists of two uprights of hard wood, with two cross pieces of the same, capable of adjustment. The frame is fitted with crooks for the attachment of the material, or with a band of coarse canvas to which the material can be sewn. These frames have no feet, and are fitted sometimes against a wall, sometimes upon a chair. When covered with the material, they are hung up against the wall by one of the cross pieces, until it is time to dismount them.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 6. Fig. 7. Fig. 8.

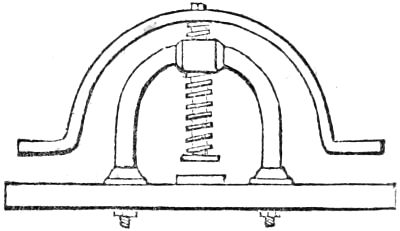

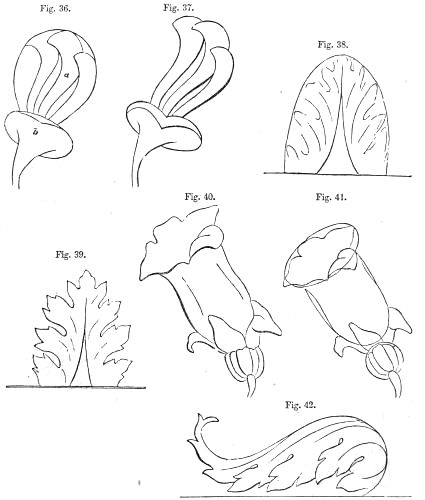

There are also various useful implements, called by the work-people "irons," for cutting out petals, calyxes, and bracts, and for giving to leaves those various serrated and other forms which produce such wonderful variety in foliage. These cutting tools, two of which are shown in Figs. 6 and 7, are of iron, with a hollow handle, flat at its upper extremity, that the hammer may be readily applied. They are about four or five inches long, and of numerous sizes and varieties. That they may cut rapidly and clearly, the edges are occasionally rubbed with dry soap. When a leaf becomes attached to the interior, and cannot be shaken out, a little ring of wire, Fig. 8, is introduced in a hole j, Fig. 7, left for that purpose to disengage it. The material is doubled several times under the cutter, so that several petals or leaves may be cut out at once. The block on which the leaves are cut out is rather a complicated affair. It is placed near a window, and as far as possible from the workers, that the blows of the hammer may not interfere with their employment. Sometimes it consists of a very stout framework of timber, on which is placed a mattress of straw to deaden the blows, and upon this mattress a thick smooth piece of lead, forming a square table, Fig. 9. In some cases a solid block of timber is used, a portion of the trunk of a tree taken near the root, and on this the mattress[297] and the leaden table are placed. The hammers used at this work are short and heavy; one is especially adapted for smoothing the surface of the lead when it becomes indented all over by the blows of the workman.

Fig. 9.

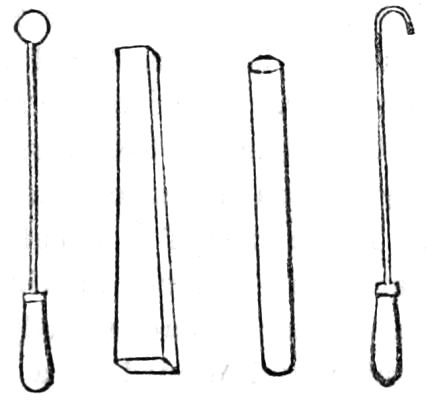

Fig. 10. Fig. 11. Fig. 12. Fig. 13.

The cutting out of the leaves and petals is only a preliminary operation to the more perfect imitation of nature; the leaves must next be gauffered to represent the veins, the fold, and the endless touches and indentations which are found in the natural plant. Gauffering is executed in two ways, the first and simplest being that which merely gives the hollow form to the petals of roses, cherry-blossoms, peach, hawthorn, and numerous other flowers which preserve, until the period of decay, somewhat of the form of a bud, all the petals beautifully curving inwards. To imitate these, the gauffering tools are simple polished balls of iron fixed on iron rods, with a wooden handle attached, as shown in Fig. 10. The balls are of various sizes, from a pin's head upwards, to adapt them to the minute blossoms of such flowers as the forget-me-not, which require only the slightest degree of curvature, and to the large flowers of camelia, dahlia, mallow, &c., where the curvature is of often very great. These balls are made slightly warm, so as to fix the forms decidedly, without effacing the colors. The petals are placed on a cushion, and the iron is pressed against them. But curvature alone is not sufficient; there is, in many petals, a decided fold or plait up the centre, springing from the point where it is attached to the germen. This fold can be obtained by the use of a prism-shaped iron, Fig. 11. Conical, cylindrical, and hooked irons, Figs. 12, 13, are also useful to imitate the various minutiæ of the blossoms. A cushion near each artist serves as a rest to the gauffering irons, which must be preserved from the least taint of dust, seeing that they are applied to the most delicately-beautiful portions of the flower. The veins and curves of leaves are given by gauffers composed of two distinct parts, on each of which is severally moulded in copper the upper and under surface of the leaf as shown in Fig. 14. Sometimes, one part is of iron, the other of copper. It is necessary to have a very large assortment of these gauffers; in fact, they should correspond in number with the cutting-irons by which the forms of leaves are punched out. The leaf or leaves being inserted in the gauffer, a powerful pressure is given to stamp the desired form. This is accomplished either by means of a heavy iron pressed on the lid, or by two or three smart blows of a hammer, or, better still, by the uniform action of a press, such as is shown in Fig. 15. Besides the above articles, the workshop is provided with an abundance of boxes, scissors large and small, for cutting wire, as well as textile fabrics, camel-hair pencils, sponges, canvas-bags, &c., that everything likely to be needed by the work-people may be immediately at hand.

Fig. 14.

Fig. 15.

The material of which flowers are made is, first and best (as already stated), French cambric, but a great quantity of Scotch cambric, jaconet, and even fine calico, are also used. For some descriptions of flowers, clear muslin,[298] crape, and gauze, are wanted; and for some very thick petals, satin and velvet are necessary. These materials are provided in various colors, as well as in white, but fresh tints have frequently to be given. These are laid on with a sponge, or a camel-hair pencil, or the petal is dipped in color; a quantity of green taffeta should always be at hand for leaves. The coloring matters used in dyeing the material for the petals are as follows: For red, in its various shades, Brazil wood is largely used, also carmine, lake, and carthamus. The best way of treating Brazil wood is to macerate it cold in alcohol for several days; a little salt of tartar, potash, or soap, will make this color pass into purple; a little alum gives it a fine crimson-red, and an acid will make it pass into yellow, of which the shade is deeper according to the quantity employed. Carmine is better in lumps than in powder; diffused in pure water, it gives rose-color; a little salt of tartar brightens the tint. Carthamus is dissolved cold in alcohol; heat, as well as the alkalies, causes it to pass to orange. The acids render it of a lively and pure red; a very delicate flesh-color is obtained by rinsing the material, colored with carthamus, in slightly soapy water. Blue colors are prepared by means of indigo, or Prussian blue. Sometimes balls of common blue are used, steeped in water. Indigo is first dissolved in sulphuric acid. This is then diluted with water, and powdered chalk or whiting is added until effervescence ceases. The liquor is afterwards decanted off, and the sediment, when washed, gives a paler color. Greater intensity is given to indigo by adding a little potash. Yellow colors are given by turmeric dissolved in spirits of wine, by saffron, chrome-yellow, &c. Green colors are obtained by mixtures of blue and yellow; violets, by mixtures of red and blue, and by archil and a blue bath; lilacs, by archil only.

The method of making a rose will give a good idea of the manufacture in general. First of all, the petals are cut out from the finest and most beautiful cambric. The pattern-shapes must be of different sizes, because, in the same rose, the petals are never equal; a good assortment of patterns enables the artist the better to imitate the variety of nature. When the petals are thus prepared, they have to be dyed in a bath of carmine in alkaline water. For this purpose, they are held separately by means of pincers, and dipped first in the bath, and then into pure water, to give them that delicacy of tint which is characteristic of the rose. But as the color of the petal usually deepens towards the centre, a tint is there laid on with the pencil, while a drop of water is laid on the point of insertion of the petal, to make the color there fade off, as it does in nature, to white. If the right tint is not given at first, the processes are repeated; any slight imperfection, such as is seen in the petals of most living flowers, being also accurately imitated with the pencil. The taffeta employed in making leaves is dyed of the proper green in the piece before cutting out. It is then stretched out to dry, and afterwards further prepared with gum-arabic on one side, to represent the glossy upper surface of leaves, and with starch on the other, to give the velvety appearance of the under side. This preparation, colored to suit the exact shade to be given to the leaf, must be just of the proper consistence, making the leaf neither too stiff nor too limp, while it gives the proper kind of under surface. Where the leaf requires a marked degree of this velvet texture, it is given by the nap of cloth reduced to fine powder, and properly tinted. A little gum is lightly passed over the surface, and when partly dry, this powder is dusted over it, the superfluous portion being shaken off. These preparations having been completed, it yet remains to give to the leaves, after they are cut out, the appearance of nature, by representing the veins and indentations which they always exhibit. For this purpose various gauffering-tools are made use of.

The material for the leaflets of the calyx in roses, is subjected to another process immediately on coming out of the dye, in order to preserve the firmness which it is necessary the calyx should have. To this end, the taffeta, while still damp, is impregnated with colored starch on both sides, and stretched on the drying-frame: when perfectly dry, the leaflets are cut out according to pattern. Buds are made also of taffeta, or, if partially open, they are made of white kid tinted of a suitable color, stuffed with cotton, or crumb of bread, and tied firmly with silk to slender wires. The stamens are prepared by attaching to a little knot of worsted a sufficient quantity of ends of silk to form the heart of the flower. These ends of silk, cut to the proper length, are then stiffened in kid jelly, and, when dry, the extremities are slightly moistened with gum-arabic and dipped in a preparation of wheaten flour, colored yellow, to represent the pollen. Each thread takes up its separate grain, and is left to dry. The heart of the flower being thus prepared, and fixed to a stem of wire, the smaller petals are arranged round it, and fixed by paste at their points. The larger petals succeed, some of which are hollowed or wrinkled, while constant care is taken to give them[299] a natural appearance in disposing them around the centre. The calyx comes next, and incloses the ends of all the petals. It is fixed with paste, and surrounded with more or less of cotton thread, which also generally incloses one or more wires attached to that which bears the heart of the flower, and forming the germ. The whole is covered with silver-paper tinted green. The leaves are mounted on copper wire, and are arranged on the stem in the order which nature teaches, the covering of cotton and tissue-paper hiding the joints.

In addition to the manufacture of flowers intended as closely as possible to represent their living models, there is a large branch of the art in which the aim seems to be to depart from nature as far as possible. These fancy flowers are the fruit of the artist's peculiar taste, and are therefore as impossible to describe as we sincerely wish they were impossible to execute. There are also flowers of natural forms, but of unnatural colors, being made to assume mournful hues to suit the circumstances of their wearers. There are also gold and silver flowers, more resplendent, but equally unnatural. Of these, sometimes the stamens and pistils alone are metallic; sometimes the petals are gilded, and sometimes the leaves and fruit glitter in the same precious metal. An easy method of applying the gilt in any device or form, is to prepare a cement which shall fix it to the cambric, paper, or other material (this cement may be honey and gum-arabic boiled in beer), and then to moisten with it the surface, placing thereon rather more gold-leaf than is necessary to cover it, pressing it down with a cotton rubber, and, when it is dry, rubbing off the superfluous gilding with the same.

Flowers are also made in chenille, but do not pretend to an accurate imitation of nature. There are two or three methods of making them, the simplest being to represent merely the shapes of flowers; for instance, apple-blossoms, represented by small loops of pink chenille arranged round a centre. Another method is, to make out the distinct petals, by rows of chenille placed close together. A third and prettier method, is that of uniting chenille with ordinary flower-making. Flowers made of feathers may be extremely rich and brilliant in their effect. Yet ordinarily feather-flowers are more difficult than satisfactory, and there are very few of our own familiar flowers that can be successfully copied by them. One of the best imitations is that of the wild clematis when adorned, as it is in autumn, with its plumed seeds. These can be admirably imitated in white marabout feathers. Some of the most available feathers for flower-making are those found under the wings of young pigeons.

The manufacture of wax-flowers is carried on by using the purest virgin wax, entirely freed from all extraneous matters. Wax that is either granular or friable must be rejected. It is generally melted in vessels of tinned iron, copper, or earthenware. To render it ductile, fine Venice turpentine, white, pure, and of an agreeable odor, is added. The mixture is constantly stirred with a glass or wooden spatula. All contact with iron must be avoided, and if the vessels are of that material, they must be well and carefully tinned. When stiff leaves are to be executed, two parts of spermaceti are added to eight parts of wax, to give transparency. Much care and tact are needed in coloring the wax. The colors being in fine powder, are made into a paste by adding little by little of essence of citron or lavender. When the trituration is perfect, this paste is mixed with melted wax, stirring rapidly all the while; and while the mass is still liquid, it is poured into moulds of pasteboard, or tinned iron, of the shape of tablets, and is then ready for use. Sometimes it is passed through fine muslin as it flows into the moulds. Another method is, to tie up the color in a muslin bag, and wave it about amongst the molten wax until the desired tint is obtained. To combine colors, it is only necessary to have two or three bags containing different colors, and to employ as much of each as shall have the desired effect. These bags, far from being spoiled by dipping in wax already containing other shades, have only to be rinsed in pure water to fit them for coloring other wax. The colors most in use in wax flower-making, are pure forms of white-lead, vermilion, lake, and carmine, ultramarine, cobalt, indigo, and Prussian blue, chrome, Naples yellow, and yellow ochre. Greens and violets are chiefly made from mixtures of the above.

The wax being prepared, the manufacture of flowers is carried on in two ways. The first consists in steeping in liquid wax little wooden moulds rinsed with water, around which the wax forms in a thin layer, so as to take the form of the mould, and thus to present, when detached from it, the appearance of the whole or part of a flower. In this way lilac and other simple blossoms are obtained with much rapidity. The branches are also executed with wax softened by heat, and moulded with the fingers round a thread of wire. As for leaves and petals, they are cut out of sheets of colored wax of the proper thickness. These sheets are glossy on one side, and velvety on the other. To express[300] the veining of leaves, they are placed in moistened moulds, and pressed with the thumb sufficiently to get the impression, which is accurately copied from nature. The petals are made to adhere simply by pressure; the leaves are placed on a little footstalk, and the latter fastened to the stem. The manner of procuring moulds for the accurate imitation of leaves, is as follows: A natural leaf of the plant it is wished to imitate is spread out on a flat surface of marble, for example. It is lightly but equally greased with olive oil, and surrounded with a wall of wax, which must not touch it. Then, in a small vessel containing a few spoonfuls of water, a few pinches of plaster of Paris are to be thrown, and briskly stirred till the liquid has the consistence of thick cream. This is poured over the leaf, and left till it is well hardened. It is then lifted up and the leaf detached, when it will be seen that the plaster has taken a perfect impression of every vein and indentation. Such moulds are rendered far more durable if they are impregnated while warm with drying oil. This gives them greater solidity, and prevents their crumbling from frequent immersion in water. It is necessary to impress strongly on all amateur wax flower-makers the necessity for having all tools and moulds completely moistened with water, otherwise the wax will be constantly adhering, and preventing neatness of workmanship.

The variety of the materials used in artificial flower-making was displayed to an amusing extent in the World's Fair. In addition to the really beautiful and artistic productions already noticed, and to the elegant flowers constructed of palm-leaves, of straw, and of shells, as well as of all the materials named in this paper, there were flowers fabricated in human hair, in chocolate, in soap, in wood, marble, porcelain, common earthenware, and other unpromising materials.

BY PERCY.

COUNT CARLO ZANOTTI was a son of one of the noblest families in Venice—the heir of its titles, its wealth, its hereditary renown, and his prospects in the spring of life were golden as the trees in autumn. An incident in his father's history, which tinged the old man's declining years with a gloomy shadow, had also its effect upon the son, and, unmindful of the brilliant future, he brooded in sadness on the past. His mother, who was the beauty of her day, had yielded to the fascinations of a young and handsome Englishman, and in an unguarded moment left her home and her husband, to throw herself upon the poor protection of a profligate, and to meet the cold sneers and savage slights of a selfish and unforgiving world. How much the character, in its gradual development, is biased by a mother's influence, it is difficult to estimate; but we all know that "the thought which mirrors Eden in the face of home" has saved even the best of us from many an error and many a sin, and generated, even in the worst, some softening emotions, and caused some kindly acts. This holy influence, linked with a mother's memory, makes each thought of her, as the German beautifully expresses it, "a prayer to God," and we rise from musing upon her gentle love—kinder, better, wiser. "The wild sea of our hearts lies mute, and o'er the waves the Saviour walks." How terrible then to have that sanctuary defiled, to be taught that purity has fled, even from Dian's temple—to be brought up an atheist in the religion of the heart!

Calm, gentle, passionless in outward aspect, the count became noted as an earnest scholar, and yet his heart contained many a hidden stratum of volcanic passion, which burned scathingly at the thought of his mother's shame! From an intense consciousness that the conduct of his parent entailed its measure of reproach upon himself, he shrank from the society of men, and sought sources of relaxation in tracing to their sequences those great thoughts which[301] the thinkers of all time, in their debasement and their exaltation, have written down and immortalized—some, on the undying page; some, on the living canvas; some, on the ever-moving firmament of ceaseless action! The shadow of the wing of time fell upon him as a man, at an age when most of us are immature, unthinking boys. The epochs of strong natures are dialed upon the mind not by the sunshine but by the darkness of the heart! Our sorrows are the evil genii who transform in a moment boyhood to manhood, and manhood to age!

Every day, every hour, this young man acquired something from ancient or from modern lore; at twenty-four he was versed in a learning beyond that of many a lifelong scholar. His studies, within a year of the period at which we introduce him to the reader, had taken a form different from any he had before pursued; the old disciples of a gorgeous mythology being neglected for the mystical and alluring spiritualism of the exponents of modern German philosophy. The English philosophy is entirely destructive of the grand, the lofty, the divine! It lowers and debases by its precepts, and chills by its explanations. The French, on the other hand, attempts no explanations; but the system is an elaborate sneer at all that is good, and true, and high, and noble. The aim of the German "is at least the nobler one, and elevates, not dwarfs, the souls of men." "There is a Godlike within us that feels itself akin to the God; and if we are told that both the 'Godlike and the God are dreams,' we can but answer that so to dream is better than to wake and find ourselves nothing!"

Who among us—but worms of the dust, low things, fit only for the mire in which they wallow—but has at one time or another demanded initiation into the secret order of the "searchers after truth?" Who among us but, unsatisfied with the knowledge that may be achieved, grasps wildly after heaven's thunderbolts, and would embrace the unattainable, feeling, as we so terribly do, the restlessness and the might of the Deity in our burning veins? Who among us but has tried to look deep into the future, and read the fate, not of the next year or moment, but of the undying spirit in that other world, of which we dream so much, and know so little?

And who among us who has had the heroism honestly to make the attempt, and to pursue to their sequences the terrible thoughts to which such reflection gives rise, but has gone down headlong to the pit? If no actual phantoms haunt the waking dreams of such unsuccessful neophytes, yet a more terrible thing is that accursed skepticism—that coldness that does not brook to be questioned, and that cannot be understood—that fills his soul. It does not come over his hours of mirth, when the wine-cup passes and the jest goes round; but, like the fabled fiend of the romancers, comes only over the lost one's soul, when his intellect would aspire and his genius dare. Comes it, with its eternal sneer, that sees nothing so high that it does not make it appear utterly despicable! When his genius would dare, comes it with its evil eyes, and he loses faith in his genius and doubts his power; loses faith when he knows that faith only can bear him through life's tempests; doubts while he feels doubt to be the unpardonable sin.[1]

Count Zanotti had passed through each of the stages of which I speak—first, an unquenchable yearning for forbidden knowledge; next, the rapture that glows when the lip touches the sparkle on the brim of the cup—and then the flatness and the weariness that follow! But for him, there was yet a hope. His heart had never beat with the quick pulse of love! Its youthful vigor was unimpaired, and in a contest with the intellect there was strong hope of it proving victorious. The struggle came soon enough.

AT the end of the long, gloomy day following the conclusion of the carnival, Zanotti accompanied his father to a midnight mass, and there for the first time saw Leonora D'Alvarez, the daughter of Spain's ambassador to the court of the winged Lion of St. Mark's. She was one of those beautiful creations that we so often dream of, and sigh for, and sometimes, but very seldom, see. Soul there shed its spiritual attributes over one from whose features even the bloom of youth seemed to catch a brighter hue. Like all Italians, Zanotti had dreamed of love—the love of the poet and the dreamer; and now he felt it in its strength—the love of a pure, unselfish, yet deep and ardent nature!

To shorten a long story (for we must leave much to be divined in this history), he felt the inspiration growing out of love impelling him to give him his feelings to the world in immortal song. He wrote, and he became famous! Then,[302] when a nation bowed before his genius—when a world re-echoed his name with reverence—he sought the woman who had roused his soul to exertion; he told her that he loved her; he told her that all the bright thoughts and sparkling fancies the universe had claimed as its own were hers—all hers; that she, and she alone, had made his name as deathless as the ethereal essence the Almighty had endowed his body with—and that unless she gave still another gift—her heart—fame, fortune, name, genius—were but empty, and hollow, and useless!

The whispered reply was no denying one, and he seemed to have attained all of happiness the world can offer. Months flew by—months in which life seemed born, like Venus, "of a rosy sea and a drop from heaven;" months when each to-morrow hung an "arch of promise," a ladder of sunlight, each round of which seemed made to lead the feet through Ivan gardens—up—up towards the sky! The glorious sun, warming like a lover's glance the beautiful bosom of the "Doge's bride"—the swelling "Adriatic"—the churches, the palaces, the prisons, whose gloom was hallowed by romantic memories, the legends attached to the palatial home of his own proud sires—these were subjects upon which, all the livelong day, he could expatiate, and she delightedly listen; and when night stole like a dream through the soft atmosphere, the stars, with their Chaldaic interpretations, furnished a new page from whence he could cull prophecies of their fate! Then would he weave old superstitions with the fancies of the poet and the lover, till he grew amazed at his own strange eloquence!

She, too, on her part, had an exhaustless theme in telling how, by degrees, his soul had, as it were, become a part of hers; how every emotion in his own mind, by an imperceptible and view-less magnetism, awakened hers to action. The simplest speech had a charm for him; there was music in her voice; her thoughts were dimless mirrors reflecting the spirituality of her soul; to use his own language, "each word was the spray of her heart, which mirrored in its sparkling globule all the beauty and none of the defects of the world around it!" The days glided by upon the swift pinions lent by unclouded happiness.

They lived in an atmosphere where all was of the past, save their love and their hopes; the multitude of traffickers and idlers that crossed their daily path were as unheeded shadows; they mingled only with beings of other times. Their friends—for the friends of the scholar became those of the maiden—were Homer and Virgil, Tasso and Marino, the graceful Catullus, and the rough, but noble-tongued Lucretius! They strolled in imagination through Ilion's Scæn gate, along the luxuriant banks of her winding rivers, and lay down to repose beneath her wild and broad-leaved fig-tree. And then, when they had gathered around them the heroes and the poets of past and buried ages, unlike Alaric, they would weigh the myrtle crown against the laurel wreath, and see glory kick the beam!

Could year after year of their lives have rolled away with such feelings and amid such employments, they would have indeed been blessed! But no! Alas! that could not be! Love, and youth, and hope, are but the sun-fringe of the cloud of life, the flame that gilds the bark it consumes, the lightning flashes that foretell a rent and shattered heart! For love, if no outward influences assail (or assailing, are conquered and driven back), there is custom, that slow, insidious lullaby, singing in Morphean tones unceasingly, till, wearied and overcome, that passion, that would have repelled a visible foe, sinks at his post in quietness—asleep!

It came! It burst upon them without a warning! Fate had suspended a sword above their heads; but, unlike the tyrant's envious favorite, they saw it not ere it fell! It came—crushing and blighting the flowers that had blossomed for them, and, tearing their young hearts from the beautiful dream-world in which they revelled, brought them back to the harsh and dull and cold realities of this! The father of the lover was suddenly arrested by the myrmidons of the terrible Council of Ten. It was discovered he was the head of a wide-spread conspiracy against the state, and the expiration of the month of his arrest saw the noble and powerful family of Zanotti exiles—its lord sent forth with the boon of life, but with ruined fortunes and a tarnished name—its heir an outcast, though spotless of a single crime.

The parting of the lovers was brief and terrible. She swore to him that death only should take the bloom from her love, that, ruined in name and fortune as he was, he was, as ever, the high priest of her heart's temple, and that no other could ever approach its altar. He offered no vows, but said to her, that if five years sped by without his presence, to deem him dead, and know he had died in striving to win laurels worthy to lay before her father's daughter!

YEARS passed, and in a foreign land Alfieri sought to win wealth and a new name to offer the idol of his heart. He succeeded beyond his wildest hopes, and with an impatience that would have been unsatisfied with the swiftness of the lightning, sped over the waters, in a richly freighted argosy of his own, back to his native city of the "Siren Sea."

Trusty adherents of his house had, in the mean time, procured the reversion of the attainder as far as it touched him, and, as his father was no longer alive, there was a strong prospect of his estate being restored to him.

Arrived at Venice, he learned that the Duke D'Alvarez had been recalled, and in the course of conversation the new ambassador mentioned that there was talk in Madrid of a projected nuptial between the Donna Leonora and the Prince Carlos of the blood royal of Spain.

Zanotti's lip quivered, and his eye flashed fiercely as he heard the rumor, but not a word escaped to betray the hot feelings that were pressing at his heart. Ere the sun sank into his bed of rosy clouds that night, his gallant ship, with straining masts and every stitch of canvas set, was speeding, like a gull, over the waters, and Zanotti paced the deck through that night and the next with a stride that betokened troubled thoughts. He reached Madrid in safety, and lost no time in finding the residence of the ambassador. There were bright lights flitting from window to window, and the sound of music was borne upon the night-wind, betokening revelry within. He stopped to question a lackey who was lounging at the entrance.

"The Donna Leonora was married this night three weeks ago, and Monseignor gives a feast to-night to his son-in-law, the prince!"

Zanotti clutched one of the pillars that supported the massive doorway, and kept his hold for a moment convulsively, for he felt his limbs failing him. This movement brought his face beneath the jet of a lighted chandelier, and the servant shrank with affright—it was like the countenance of the dead! Terrible as was the struggle in his breast; fearful as was the sudden contest of passion and despair; lost as he was to aught but a blighting sense of the wreck and desolation of his hopes, he still could not be oblivious to the significantly curious glance of the affrighted servant. By an almost superhuman effort he repressed further show of feeling, and his voice was without a particle of tremulousness, although very hollow, as he told the menial to announce "General di Romano." Such was his new rank and name! Many a fair dame started as that tall, majestic figure, with its proud head and features, pale and rigid as if hewn from the quarries of Pentelicus, passed her, as straight he proceeded to the extremity of the apartment, where, in a group conversing with smiling looks, stood the Duke de la Darca, his daughter, and the Prince Carlos of Spain. The count (or, as we should now call him, the general), unobserved by the group, placed himself near one of the large Gothic windows, opposite to which was a group of statuary that effectually concealed him from view. Here he paused to gaze upon the woman who had wrecked his happiness! Four years had passed without robbing her of a single grace, and she stood there sparkling with diamonds, radiant with beauty, and with a regality of bearing that well became her new and princely station.

An hour had elapsed, and he had watched her through many a stately measure in the pompous dances of her country, and heard her light jest and her gay laugh, and saw the same haughty fire in her magnificent black eyes, through all! Jealousy has often been described, and the burning words of the poet have wrought out an appalling picture; but if, during that hour, each wild throb of his bursting heart, if each shooting fire of his seething brain, if the madness and the agony and the fierce black promptings that fashioned each thought into shape, and called it murder! could have been conveyed in words or upon canvas to the minds of less volcanic natures, they would have laughed to scorn the artist or the author, and accused him of conjuring up the Titan agonies of hell to confine them in the contracted space afforded by the heart of a mere mortal man!

He turned from the revellers, sick and dizzy, and gazed out upon the night. The scene was as fair a one as God's smile ever lighted into beauty. The moon—floating in a sea of blue, cloudless, with the exception of one fleecy-looking mass of vapor that covered a small space like a veil of silver tissue—poured a flood of radiance upon a garden (surrounding the house on three sides) filled with rare exotics, and in the distance the steeples of the city rose up towards the sky, as if formed of luminous mist. The stars, too, were scattered round night's queen in rich profusion, and the air was fragrant with the breath of orange-blossoms. The Venetian, even in that land of sunshine and of flowers—his native Italy—had never looked upon as beautiful a scene. But it suggested no soothing fancies! It only revived the memory of hours of which it was now madness to think! Hours that were[304] freighted with dreams and aspirations as lovely as itself! Hours that were passed—and forever; and aspirations that were coffined and dead! His brain seemed bursting with the heat of the room, and, as the window was a casement but a few feet from the ground, he sprang out, and walked with a hasty step in a direction in which, from a plashing sound that smote his ear, he hoped to find a spring or fountain. He found his conjecture a correct one, and, stooping down, laved his fevered temples in the liquid, which was as cold as ice, but seemed ineffectual when applied to the terrible fever that consumed him! He threw himself upon a richly sculptured seat that was supported by two marble Dryads on the edge of the fountain, and, in spite of every restraining effort, groaned aloud. He had remained thus for some time, regardless of time, place, everything but a dull leaden weight of misery, when a light footfall on the hard gravel roused him, and, springing from his recumbent position, he was about to conceal himself amid the foliage of the adjoining shrubbery, for he was in no mood for society just then. He also had been heard, however, and a rich, musical voice exclaimed—

"Dear father, are you there?"

Good heaven! it was her voice! He stood spell-bound—volition was suspended. The next moment they were face to face! With a low thrilling cry, she cast herself upon his breast. There was a gleam half of terror—partly of surprise and partly of joy—within her eyes. There were the two again! ay, even as of yore! Leonora and Carlo! The ruined noble and his betrothed bride—the princess and the soldier!

AN instant, but a single instant, the lady remained upon his breast, and then Zanotti, removing her clinging arms, placed her upon the seat which he had himself just occupied. She looked upon him, her full dark eyes flowing with tears, and seemed struggling for utterance, but no words came! At length, with an averted face, he spoke—

"Your highness forgets our relative positions, and"—

"Forgets!" said she wildly, interrupting him; "forgets! Ay! I did indeed for a moment forget all but you; and you, Oh Carlo, is yours the voice to bring back reality? Is it for you to whom every pulsation of my heart has been dedicated; for whom in the long hours of night I have wept tears that seemed of blood—is it for you to restore me to a reality which contains no elements but those of despair, those that break hearts, those that frenzy the exhausted brain?"

Alfieri's voice was sepulchrally hollow when he replied, and the quivering of his manly frame showed the violence of the emotion within.

"Leonora," said he, "Leonora, four years ago we parted in Venice. I vowed never to see you more till I had won a name you could not shame to wear; and you swore never to betray my deep devotion. I was then unacquainted with life; I was young and trusting; I looked upon the flower and inhaled its perfume, nor sought to analyze what hidden poisons lurked within it; I looked not for a serpent or a viper in its folded leaves! I gazed upon the diamond-sheeted waters, nor thought upon the noxious elements that, uniting in malaria, might rise from their bosom to desolate many a neighboring home. I turned my eyes upon the moonlit sky without a thought of a possible hour when the same azure face of heaven would frown and the live thunder launch its bolts to ruin and destroy! Ay! I then looked but at the fair outside of all created things, and heeded not the motive or the soul within! Leonora, I looked on you, and I believed you! I went forth cheerfully to the hard fight I had before me; I kept my vow—I am a field-marshal of Austria. Have you kept yours?"

She cast upon him an imploring, a piteous glance. The moon was beaming through an interstice in the foliage and shone full upon his features, making their paleness ghastly, but showing no violent emotion—nothing but a hushed, cold, haughty sorrow.

She trembled perceptibly as she replied to his concluding question.

"Yes, as truly as I have my faith in God; Alfieri, they told me you were dead. Circumstances too complicated to explain placed my father in a position with the government that involved his life. Prince Carlos saved him, and, for the priceless service, asked but the poor repayment of my hand. I told him my heart could not accompany the gift. He still urged his suit. Could I refuse?"

"Ay, madam, the tale sounds well," was the bitter reply; "but your grief seemed of a strangely merry sort; but now your laugh was as light as any in the room, your jest as gay!"

"Zanotti!" said the lady, and there was something[305] of indignation in her tone, "I am not what the world in its cold carelessness deems me, and you judge me as the greatest stranger of them all would do! The face may be wreathed in smiles, the lips may be musical with laughing jests, and yet, in its unrevealed depths, the heart may writhe in anguish, the soul sink with despair! But this recrimination is vain, all vain!"

She clasped her forehead as if in pain, and hot tears forced themselves through the tightly pressed fingers. Her lover maintained a cold and scornful silence. All the pride of his race had combined with a deep sense of injury in a trusting and betrayed nature to make him stern and apparently heartless in his resentment. Suddenly Leonora started to her feet, the woman's pride within her revolted at what seemed the silent sarcasm of his look. Her eyes, with the tears checked suddenly within them, emitted a wild, singular, startling light; there was something of the Medusa in her aspect. She gazed at him with a strange mingling of supplication and haughtiness in her look; her glance penetrated his soul and softened it; he heard the panting throb of her heart, and knew there could be no acting in that. Her breath came warm upon his cheek; he trembled at the recollections that were crowding upon him. And then, too, she spoke—

"You use me too cruelly," she said; "I do not deserve this silent scorn! I have wronged myself by giving way to emotions for which you but mock and despise me!"

He started—were not her words true? Had he not been unjust in his grief?

"Leonora," said he, abruptly, "hear me! From my earliest youth—ever since remembrance avails me to recall events—rash, impetuous feeling (my inheritance from a long line of hot-headed ancestors) made me in every feeling extreme and violent. I rushed to my studies as to a conflict with a foe, and rested not till I had conquered every difficulty. The same in pleasure, obstacles were but the stones that made the stream of life sparkle brightly in its sun, and I leaped over them, or cast them aside with an exulting sense of power. My love for you concentrated all this vagrant impetuosity into one earnest and undying passion. It subdued and soothed the sinuosities of my outward nature; it checked the headlong restlessness that was before apparent in all I did, and turned all the various bubbling springs within me into one noiseless, but deep, resistless stream. It made an ocean of the rivers of my being; that ocean rose and fell, tinted with the sun's glorious beams for a brief space! Oh! how brief! and then storms arose; and now, when I know the tempest is to last forever, is it strange if I am indignant when I look on her who wrought all this misery, this fearful misery?"

He had spoken without looking up at her. He now raised his eyes, and found her again weeping bitterly.

"And do I not share that misery, with all the aggravation of a fruitless remorse? Oh, you know not," she added, her voice assuming a tone of beseeching earnestness, "the days and nights of intense anguish that dragged their slow length along, when thinking you lay beneath the deep sea (for they said your grave was there). When tears would flow, I wept for you, and mourned in silent anguish when they were refused me! You know not how stronger than a woman's that heart must be that can resist the appeal, continued day after day, when it comes from the lips of 'all, whom we believe to be in the wide world, whom we would bless.' Words may be met and combated; but the mute lip and imploring eye—they cannot be resisted; the tenderness that veils its dearest wish for fear of grieving us; the grief unspoken, and the more bitter from concealment! Who can see this, and in a father, every day, every hour, every minute, and nerve their hearts to deny the relief they can bestow? But all this avails nothing; the tie is irrevocable that binds me to misery and severs us forever. For you, Zanotti, you will go forth into the world; excitement is an antidote provided for the grief of man. You will win admiration and applause; your fame as a scholar and a poet, your renown as a soldier, will secure you a high position among men, higher than your rank alone would give. You will be loved, you will love again, and our hours of rapture will linger in your mind but as the recollection of a dream! I ask but a kindly remembrance and forgiveness of my unintentional sin. Farewell!"

"And is it thus we part!" There was a proud repelling sorrow in the lover's tone as he thus replied: "Is this, then, the end of our golden dream!" He paused, and, suddenly advancing, bent his head close to her ear, "Leonora, do you love me still?" The question was in a whisper. She started, a singular, a terrified expression mounting into her face. She was about to speak, but even as the words seemed on the eve of utterance, a crashing sound, as of some one forcing his way through the thickly intertwined branches of the neighboring vines, caught the attention of both herself and her companion, and, with a stifled shriek, she looked round as if seeking an opposite path by which to escape. Her[306] intention was frustrated, however, for in an instant after the intruder made his appearance.

"My husband!"

Leonora said but these two simple words, but there was a desperate impassibility in the tone in which they were spoken, that told of a heart whose terror was frozen into despair.

Zanotti, whose face had flushed crimson on the first appearance of the prince, was again as pale as death. The moon looked calmly down upon all, and God knows she had seldom shone on three persons whose hearts, in their agony, came nearer epitomes of hell than the group assembled there. Leonora seemed rooted to the spot, bound by a spell, a charm. Her small, beautiful hands were clenched convulsively together; her breath came with quick and labored gasps; her form seemed convulsed with a terrible and racking agony! She looked from her lover to her husband—a look beseeching their mutual forbearance—made a step forward, seemed struggling to articulate, and fell heavily to the earth.

SHE fell at the very feet of her husband, and he looked down with a smile that was sardonic in its bitterness. Zanotti, under an impulse that paused not to reflect that under the circumstances the action was an insult to the man who deemed himself already foully wronged, advanced with the intention of raising her, but Prince Carlos waved him back. Not a syllable had either of these men uttered. Their glances were sufficiently intelligible without speech. They seemed mutually fascinated; a kind of magnetism seemed to draw upon each the other's eyes. At length, the terrible silence was broken. It was the prince that spoke, and, as he did so, his look was terribly significant.

"Come, senor! You wear a sword!"

"What would your highness have?" said Zanotti, in the low, hoarse tone of a man struggling to subdue irrepressible emotion.

"I have said it. Draw!" was the short reply.

"What, here?" The remark escaped Zanotti unconsciously, as his eye sought the extended body of the insensible Leonora.

"Ay, sir!" said the prince. "She'll heed it not. In these little plays, you know, a tragic scene is indispensable to keep up the interest. Why should not the heroine witness it?"

Zanotti shuddered beneath the maniac look that accompanied this affected jocularity.

"As you will, sir," said he, sternly, repressing all show of feeling. "But," he ventured to add, "the lady, prince. It were unnecessary cruelty to leave her thus."

"Rather say kindness," said the other, solemnly. "It were a mercy if she never recovered."

The prince drew his sword as he spoke, and motioned to Zanotti to do the same. He did so, and, even in the momentary period occupied by the action, what a world of thoughts thronged upon him! He thought of his old cloister life, when books were at once his mistresses and his friends; he thought of his first meeting with Leonora d'Alvarez; of their parting, mitigated by a hope of reunion under happier auspices; of the miserable disappointment of that hope; and of the fearful future that was before Leonora, whether he lived or died, unless—and how weak the chance!—her husband could be convinced of her innocence.

"Prince Carlos," said he, abruptly, as the other placed himself on guard, "before we enter upon a struggle beside that inanimate body—a struggle in which death may seal my lips forever—I must crave a moment's attention. Your wife"—the word seemed almost to choke him—"is innocent of any wrong at which your suspicions would point."

The prince smiled—a smile of bitter, disdainful incredulity.

"It is true, and it were useless to deny it, I love her."

The prince started as if stung by an adder, the first departure he had made from his courtly immobility. Zanotti observed the gesture, and it gave him confidence; it showed this icy statue had human passions. He added, in a firmer tone than he had been capable of using before—

"Yes, Prince Carlos, the only being my heart worships lies there at your feet; but that love is of an earlier birth than her knowledge of your highness, and therefore the acknowledgment cannot be insulting. To-night I met her for the first time in the space of four years, and the meeting was accidental. With scarcely the hope of its finding faith, I make this asseveration. It is necessary for the reputation of that much injured lady. Her virtue—her purity is as untarnished as yonder sky!"

"Of her reputation," said the other, haughtily, "I know how to guard it. For her VIRTUE". A cold, venomous look of unbelief said the rest.

"Prince," said Zanotti, and his face showed[307] some indignation, mixed with a haughty assumption of calmness—"prince, my words are probably those of a man about to solve the mighty secret of futurity, and I swear to you she is innocent! I pledge you all my hopes of eternal salvation, and trust that God may spurn me from his throne of mercy if my words contain an element of falsehood!"

"Oaths, on such an occasion," said the other, coldly, "are worthless. This is a superfluous waste of words. Leave her defence to herself. The question is now between you and me. Your presence here, with the avowal of passion you have made, is in itself an insult demanding reparation. I consent to forget the difference of rank between a hireling soldier and a prince of Spain, and you can hardly refuse to meet my vengeance."

"Enough, sir!" said Zanotti; "that slight was unnecessary. I am ready."

Their blades crossed, and, at first, every movement was studied and cautious, as if each sought to measure the other's skill, and hesitated to risk consequences that, in the situation in which they were placed, involved life or death. Many a feint passed between them, and each found in the other a much more formidable antagonist than he had anticipated. The Italian, the moment his sword touched that of his adversary, regained at once the calm, resolute bearing of one accustomed to rely upon those qualities for existence; and the Spaniard, at first, exhibited an equal degree of coolness. Gradually, however, he grew more excited, and made one or two lunges, which were quickly parried, but no effort made to return them. This indicated, on the part of Zanotti, an intention either to confine his action to defence, or murderously wait an opportunity of ending the struggle by a single, fatal stroke. Either supposition, as be-speaking a consciousness of superiority, was sufficiently galling to add to his excitement, and his thrusts increased in number, leaving him at each more and more exposed. But, suddenly, Zanotti altered his tactics. He brought his "forte" in contact with his opponent's "foible," and the next instant the prince's weapon, twirled from his grasp, was spinning through the air and fell upon the ground at some distance from where they stood.

For one moment, one single moment, the Spaniard glared upon him, his face bearing a look of concentrated venomous hate, then, snatching from its jewelled sheath a short stiletto, he sprang with the bound of an enraged panther upon his foe. Taken unprepared—for, the moment his adversary was disarmed, he had dropped the point of his own weapon—Zanotti staggered and fell, and the next instant the dagger was, as it seemed, plunged up to the very hilt in his heart.

Drawing the weapon from its still palpitating sheath, he wiped the blade, and then, with hands wet with her lover's blood, took the form of Leonora, yet happily insensible, and bore it to the palazzo. There was still revelry and mirth within.

Years have passed; it is night, and the stars are scattered over the broad, clear face of heaven, an archipelago of worlds. There has been a thunder storm during the afternoon, and large rain-drops still burden the foliage and the grass, sparkling like a maiden's bridal tears. The sky hangs, as it were, in quiet fondness over the earth, and the night-wind is sighing love tales to the flowers.

In a garden, situated a few miles from Cordova, which incloses within its high walls a lightly, but tastefully built edifice of considerable size, are assembled some six or eight persons of both sexes. Their attitudes and occupations are various. One young girl reclines negligently, but gracefully, on the still damp grass, and touches the chords of a guitar with no unskilful hand; a fine-looking man, in the prime of life, paces up and down a long avenue, and seems to be absorbed in meditation; and another, a lady, is weaving flowers into garlands. She is a splendid-looking woman, of perhaps five-and-thirty years of age, with those large, liquid black eyes that seem to absorb and reflect back to you a portion of your own soul. Her look, however, is sad and hopeless, even her smile giving but a pale, wintry gleam. Ever and anon she sighs, too, and talks to herself in a tone unintelligible to the ear, but breathing a sad, Æolian strain to the heart. Her eye wanders in bewilderment, seeking imagined forms. Her emotions seem to be all mute, expressionless, without a language, and translatable only by signs. It is Leonora; she is crazed!

AGAIN 'twas night; but this time deepening into morn. In a spacious chamber, furnished[308] with all the appliances of opulent luxury, sat a man, upon whose massive brow forty winters had traced many a deep and rugged line. He seemed one who had not been slighted by fortune, for the insignia of several illustrious orders hung upon his breast. A small cabinet table, upon which were strewed gorgeously bound books and written papers of various kinds, was drawn up beside him. The materials for writing were also there; but he heeded them not, but sat with his head leaning upon his hands apparently in abstracted meditation.

He remained in this position for full an hour, not moving a single muscle, and more like a dead than a living thing. Then he arose suddenly, and paced the apartment with a vigorous and hasty step. His limbs were firm and his form athletic; it was his head only that looked old. This also lasted some time, and then he sat down once more, and, unlocking a concealed drawer, drew forth a letter and a miniature. Upon the letter he gazed long and earnestly, his look assuming an expression of mingled terror and dejection piteous to behold. Laying down the picture with a sigh, he then opened the billet and began to read, his countenance becoming each moment more careworn and haggard. And it was not strange it should be so; for it is a mournful thing to look upon the letters that once told of the throbbing affection of some friend or loved one, when the friendship is dead or merged in a deeper feeling for another, or the love is banished forever from its chosen temple. To recall the words that dropped on the page; archangels proclaiming with trumpet notes that we were the idol of one beating heart at least; to bring up again our old smile, and find it gleams, and with no Promethean power, upon affection's corse. Ah me, 'tis sad, indeed! The reader muttered to himself ever and anon, but his words were disjointed and unintelligible. He sighed, too, frequently and deeply, and even groaned aloud as he read the following passage:—

"Oh, believe me, your highness, it is fate, and not my own will, that makes me seem ungrateful! The gratitude your priceless favor has engendered in my breast is so warm, so fervid, that my life would be cheerfully given in requital; but when you ask my heart, alas! I can only say, I have it not to give. Years ago, ere I had seen your highness, or dreamed of the possibility of our ever meeting, Love had in my heart a Minerva birth, and, though the object of it lies in a bloody grave in a stranger's land, it will live in my own weary soul while it remains on earth, and accompany it when it flees to join him. You say, 'Perhaps I have not yet been fortunate enough to win your love or attract your regard but let me beseech you at least to receive and weigh the depth, the purity, the strength of my devotion against that of other men ere you decide.' Monseignor, you compel, even were I not willing to accord, my 'esteem;' my worthless 'regard,' and all the love my father and the dead do not claim, you also have; but were I to consent to your request, and become your wife, at his own altar should I send up a perjured vow to God."

Carefully, he placed both letter and picture in the drawer from whence he had taken them; but, instead of locking it, drew forth another "billet." It was much shorter, a mere note, in fact, but seemed to contain matter as pregnant with agitation as its predecessor. He paused some time over the following postscript:—

"You tell me that the grave, in closing over the object of my love, severed the tie between him and me forever—that death pronounced a divorce which gave me liberty to form another attachment. You know not woman's love to say so. It is impossible, when once ignited, to quench it entirely. It may be unseen, the ashes may be cold; but a spark certainly slumbers beneath them, and will never, never die! Oh, your highness, let me entreat you to select some worthier object than myself upon which to lavish your affections! I can never be yours!"

The man read this to the end. When he had finished, there was a smile of mockery upon his face; but a spasmodic shudder which convulsed his frame evinced the pain which it was meant to hide. How we learn to cheat ourselves by playing the hypocrite to others! The letter fell from his grasp to the floor. His head assumed its old position on his hand, and he gazed on vacancy. He remained in this posture so long that the candles one by one flickered and went out, not even perceiving, so great was his abstraction, the glare they gave just before they expired. The large gothic window immediately opposite to where he sat was open, and the air grew cooler and cooler each moment. It seemed, however, as if there were no stars in the sky—all was darkness. Suddenly, a terrific flash of lightning illumined earth and heaven, and cast a strong ruddy glare upon every object in the apartment. A tremendous peal of thunder followed, and the man started to his feet and advanced to the window. The rain was now coming down in large drops, and flash after flash of lightning, and peal after peal of thunder followed each other with astounding rapidity. The wind, which had lain motionless and dead previous to the beginning of the storm, now at one moment[309] went rushing by with extreme violence, and the next sank into a low moan that was awful enough to blanch the cheek and palsy the heart of the stoutest. It was like the wailing voice of a God sorrowing over the sins of man, or the spirit of earth singing a dirge over vanished time.

The tenant of the chamber stood with folded arms, regardless of the fierce gusts that ever and anon dashed the heavy rain-drops in his face, and the ghastly blue tint cast upon his countenance by the lightning made him look unearthly enough to be the arbiter of the dreadful contest then raging between the shrieking storm fiends. His eye grew brighter and more glistening. There seemed a sympathy between the unchained elements in their rage and his own proud spirit. His form dilated, and he seemed to look with a strange delight upon the swaying trees bending beneath the terrific blasts of wind, and to list to the crashing thunder with a fierce joy. A magnificent oak, which had resisted every attempt of the tempest to more than shake its smaller limbs, was suddenly torn up by the very roots, and, with a rushing noise, fell to the ground. The very earth seemed to groan as it fell.

"Thus would I die," exclaimed the looker on, exultingly—"thus would I die! Amid a world's agonizing throes, when the mountains seem to bend their scathed tops, and the ocean roars its submission to the storm."

As he spoke, he advanced, heedless of the elements, through the casement, and stood upon the extreme edge of the battlemented parapet. A shrill, mocking laugh greeted his concluding words, and a voice, that seemed to his excited imagination preternaturally hollow, exclaimed—

"And die thus you shall!"

For a moment he stood perfectly paralyzed; but a heavy hand was laid upon his shoulder, and he turned to meet the glare of two eyes that shone as if lit with fire from hell. The person from whom the glance proceeded held in a threatening position a long, keen-looking dagger, and the blade gleamed brightly in the electric light with which a sudden flash of lightning illumined the scene. The man who had a moment before looked defiantly upon the wrathy heavens shrank from the danger which now threatened him from a human foe. It was, however, but for a moment. He saw in the implacable countenance of the man who had so strangely come upon him, sufficient evidence of some dark and evil purpose to make him look for mischief. He suspected the existence of a danger that would tax his every energy. He turned upon the intruder a look of inquiry, firm and proud, and somewhat rebuking in its aspect. The next moment, however, recollecting that, in the intervals between the flashes, all was invisible, he put the question audibly, which before he had mutely expressed. A tremendous peal of thunder drowned the words in its frightful reverberations, and the lightning that followed showed him the arm of his foe raised to strike. Even as the blade touched his breast he caught his adversary's wrist and threw himself upon him. Powerful he found him beyond all expectations, and his cheek turned ghastly pale, for he felt hope deserting him.

The struggle was terrible; a look of vengeful despair sat on the beaded brow of one, and deep, dark, unmitigable hate gleamed in the strained eyeballs of the other. The assailed man chafed like a maimed lion in the hunter's toils, and his efforts bore that character of ruthless savageness which is the consequence of hopeless fear—of rayless despair. The other, in the proud consciousness of tried strength, dashed his dagger into the bosom of the clouded chaos that formed the atmosphere in which they fought, and, by the exertion of resistless bodily power, bore his victim back towards the verge of the parapet. Too pale to seem human, like the animated statues of two contending gladiators, they rocked to and fro on its extremity. A momentary strife ensued, in which the muscles of each seemed cracking with the might of their exertions. For a single instant, the assailant seemed to give way, and the heart of his victim beat with a hope that intensity made an agony; but the relaxation was but the prelude to a more violent effort. Again they were upon the verge of the battlement—they balanced upon the edge—and then sank into the darkness. A wild, sardonic laugh, and a cry of agony that seemed to freeze the very elements and hush their destructive howl into silence, went up to heaven, succeeded by a dull, heavy sound that announced the departure of two souls to judgment.

The next day the patrol discovered, beneath the postern that opened upon the castle fosse, two mangled bodies, quite dead. The one was the Prince Carlos, Regent of Spain, and the other the Count Carlo Zanotti.

BY MARGARET FLOYD.

(See Plate.)

THE early years of few have been so carefully guarded and protected as were those of Edith Frazier. Her father was the rector of a church in a beautiful but secluded country village in the south of England. In addition to his sincere piety and high-toned moral character, Mr. Frazier possessed a well-cultivated mind. His wife was also a superior woman, and as Edith was their only child, her early training was the object of their most careful attention. In a lovely and sequestered home, surrounded not only by the comforts and luxuries, but the elegances of life, and in close association with persons of high refinement and elevated goodness, the young girl grew slowly up to womanhood. There was no undue excitement of vanity or the passions to force her, like some hothouse plant, into an early maturity; and no unseasonable call upon her for self-reliance or exertion, which entirely blots out of some lives the sweet carelessness of girlhood. At sixteen, she was still almost a child, when the death of her mother, her first great sorrow, made her sensible for the first time that this world is not the place for that uninterrupted happiness which had, until then, been her portion.

Edith was almost heart-broken at the loss of her mother. They had been constant companions, and she missed her every moment more and more. Mr. Frazier tried to supply to his daughter the place both of father and mother, but he was a studious, reserved man, and himself suffering deeply from his bereavement, so that they did little else but remind each other constantly of their great sorrow.

About a year after Mrs. Frazier's death, finding that his daughter did not rally from the depression so foreign to her nature, Mr. Frazier proposed a tour through the northern part of England and Scotland. It was just at the beginning of the pleasant summer weather, and, arranging matters in his parish so that his absence for two or three months would not be felt, he decided to leave immediately.

On the Sunday before his departure, a stranger was seen in the little parish church. He was a man who would have been noticed in any place, and who, in a quiet country village, was an object of general attention. Tall, handsome, and with a strikingly high-bred and gentlemanlike appearance, he would have been singled out anywhere as one of nature's nobility. Edith was struck and gratified by the stranger's evident interest in the sermon her father preached that day. It was one with which he had taken especial pains, and the daughter, proud as well as fond of her father, was glad to see that he had at least one appreciative listener.

A few days after, Mr. Frazier and Edith set out on their journey. London was their first stopping-place, and several very busy days were spent there, while Edith, with the vivid interest of one to whom almost everything in that vast and crowded city was strange and new, visited the many places of interest and note within it. While they were standing in St. Paul's, the stranger who had attracted their attention in Hillcomb, their own village, a few days before, passed them with a look of evident recognition. They met again while going over Westminster Abbey; and it so happened that they were at the same time paying to the genius of Shakspeare the homage of a visit to his grave at Stratford, and that they passed each other again while strolling over the grounds around Newstead Abbey.

By this time they had advanced so far on the way to acquaintanceship, that, when they again encountered each other near the lakes in Westmoreland, the home of so many of the poets of England, a bow was the almost involuntary mark of recognition. English reserve and shyness might have prevented any more intimate intercourse, but for an accident that happened to Edith in Scotland.

Mr. Frazier, finding that the cool and bracing air of that country had as favorable an effect on his daughter's health as the wild and romantic scenery had on her mind, and being pleased with a quiet country inn which he had found, proposed that they should make it their home for two or three weeks. They could not have found a pleasanter resting-place, for Lock Lomond was spread out in its calm serenity at their feet, and Ben Lomond towered in savage grandeur above their heads.

The first person whom they recognized on taking their seats at the table of the inn was the stranger whom they had met so frequently. Edith could not repress a smile as she shyly returned the stranger's salutation, at the chance that seemed to take such a whimsical pleasure in thus bringing them together. A few days after, while walking with her father in the rude paths on the side of the mountain, she strayed a little way from him when he stopped to admire the scene from some particularly favorable point of view; and when she attempted to return, she found herself, to her dismay, so perplexed by the intricate windings of the paths that she was at a loss which to take. She called to her father and heard his voice in reply, but it grew fainter and fainter, until, at last, it could no longer be discerned. Becoming aware that every step she took only led her farther from home, she stopped to see if she could not in some way distinguish the right path. But she was so utterly bewildered that she found it to be impossible. She thought that the only thing that was left for her to do was to remain stationary; in that way she would, at least, avoid the danger of falling into the mountain streams around, or down any of the precipices.