Title: Stage-coach and Mail in Days of Yore, Volume 2 (of 2)

Author: Charles G. Harper

Release date: January 11, 2019 [eBook #58668]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Charlie Howard, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

WORKS BY THE SAME AUTHOR

The Brighton Road: Old Times and New on a Classic Highway.

The Portsmouth Road, and its Tributaries: To-day and in Days of Old.

The Dover Road: Annals of an Ancient Turnpike.

The Bath Road: History, Fashion, and Frivolity on an Old Highway.

The Exeter Road: The Story of the West of England Highway.

The Great North Road: The Old Mail Road to Scotland. Two Vols.

The Norwich Road: An East Anglian Highway.

The Holyhead Road: The Mail-Coach Road to Dublin. Two Vols.

The Cambridge, Ely, and King’s Lynn Road: The Great Fenland Highway.

Cycle Rides Round London.

The Oxford, Gloucester, and Milford Haven Road: Two Vols.[In the Press.

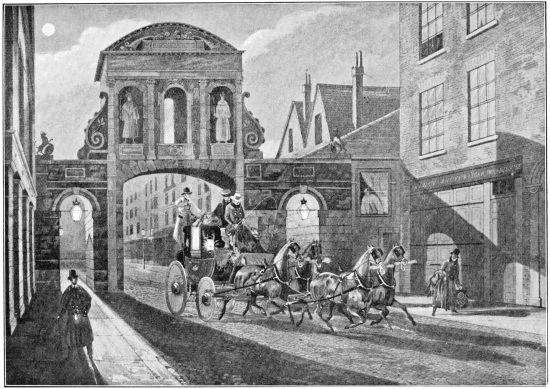

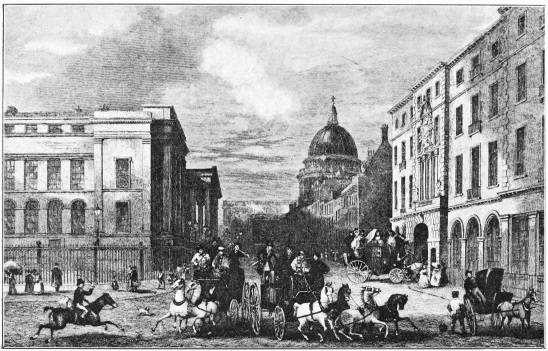

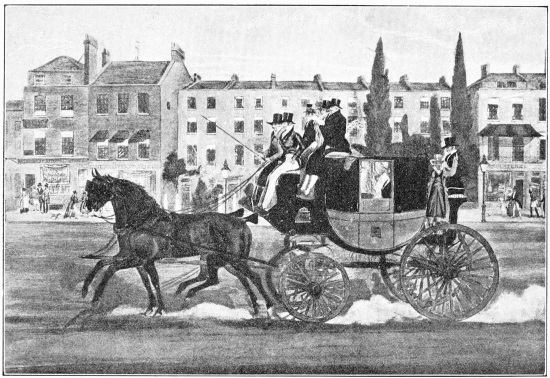

MAIL-COACH PASSING ST. GEORGE’S CIRCUS, SOUTHWARK, 1797.

After Dalgety

STAGE-COACH

AND MAIL IN

DAYS OF YORE

A PICTURESQUE HISTORY

OF THE COACHING AGE

VOL. II

By CHARLES G. HARPER

Illustrated from Old-Time Prints

and Pictures

London:

CHAPMAN & HALL, Limited

1903

All rights reserved

PRINTED BY

HAZELL, WATSON AND VINEY, LD.,

LONDON AND AYLESBURY.

vii

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Later Mails | 1 |

| II. | Down the Road in Days of Yore. I.—A Journey from Newcastle-on-Tyne to London in 1772 | 48 |

| III. | Down the Road in Days of Yore. II.—From London to Newcastle-on-Tyne in 1830 | 66 |

| IV. | Accidents | 96 |

| V. | A Great Carrying Firm: The Story of Pickford and Co. | 123 |

| VI. | Robbery and Adventure | 144 |

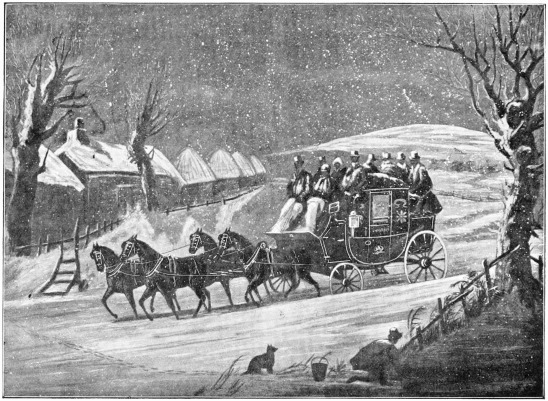

| VII. | Snow and Floods | 159 |

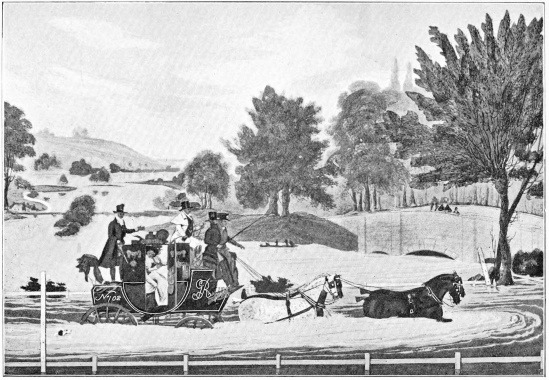

| VIII. | The Golden Age, 1824–1848 | 173 |

| IX. | Coach-proprietors | 194 |

| X. | Coach-proprietors (continued) | 226 |

| XI. | The Amateurs | 239 |

| XII. | End of the Coaching Age | 260 |

| XIII. | What Became of the Coachmen | 292 |

| XIV. | The Old England of Coaching Days | 322 |

ix

SEPARATE PLATES

| PAGE | ||

| 1. | Mail-coach passing St. George’s Circus, Southwark, 1797. (After Dalgety) | Frontispiece |

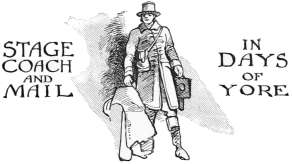

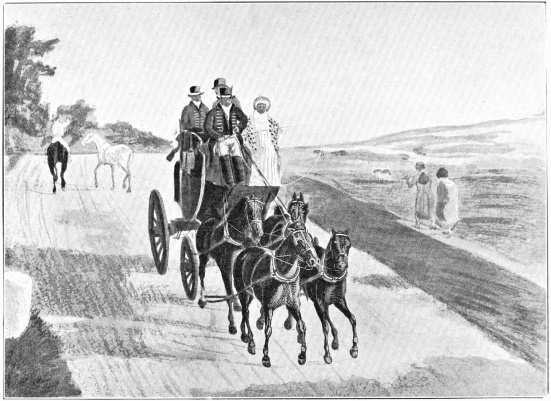

| 2. | The Worcester Mail, 1805. (After J. A. Atkinson) | 7 |

| 3. | The Mail. (After J. L. Agasse, 1842) | 13 |

| 4. | The Bristol Mail at Hyde Park Corner, 1838. (After J. Doyle) | 19 |

| 5. | The Yarmouth Mail at the “Coach and Horses,” Ilford. (After J. Pollard) | 25 |

| 6. | The “Quicksilver” Devonport Mail, passing Kew Bridge. (After J. Pollard) | 29 |

| 7. | The “Quicksilver” Devonport Mail, arriving at Temple Bar. (After C. B. Newhouse) | 37 |

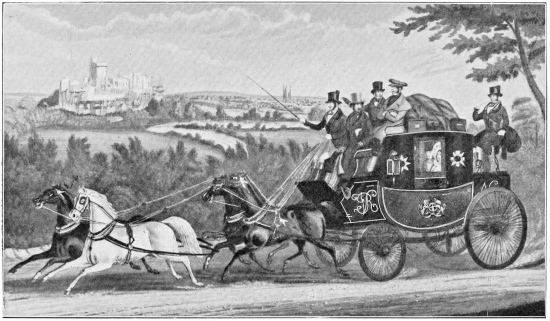

| 8. | The “Quicksilver” Devonport Mail, passing Windsor Castle. (After Charles Hunt, 1840) | 41 |

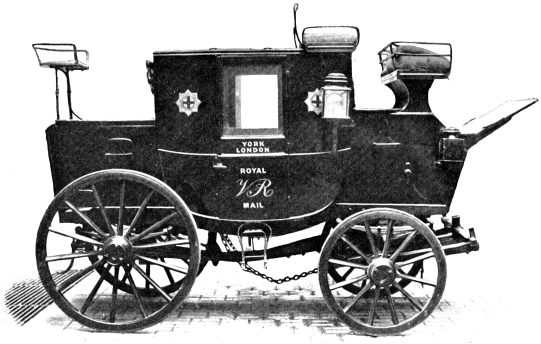

| 9. | Mail-coach built by Waude, 1830. (Now in possession of Messrs. Holland & Holland) | 45 |

| 10. | The “Queen’s Hotel” and General Post Office. (After T. Allom) | 69 |

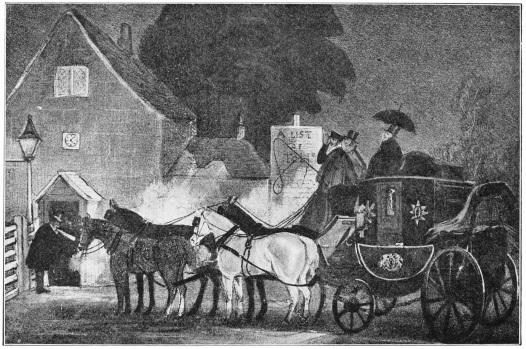

| 11. | The Turnpike Gate. (From a contemporary Lithograph) | 77 |

| 12. | A Midnight Disaster on a Cross Road: Five Miles to the Nearest Village. (After C. B. Newhouse) | 99 |

| 13. | The “Beaufort” Brighton Coach. (After W. J. Shayer) | 103 |

| 14. | A Queer Piece of Ground in a Fog: “If we get over the rails, we shall be in an ugly fix.” (After C. B. Newhouse) | 111x |

| 15. | Road versus Rail. (After C. Cooper Henderson, 1845) | 117 |

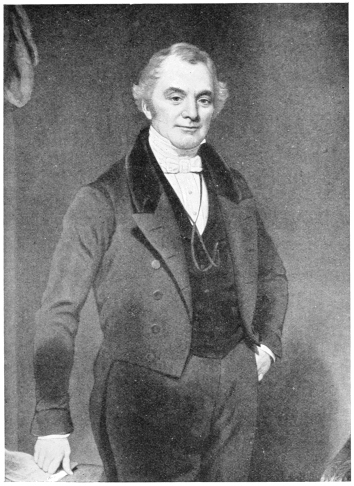

| 16. | Joseph Baxendale. (From the Portrait by E. H. Pickersgill, R.A.) | 131 |

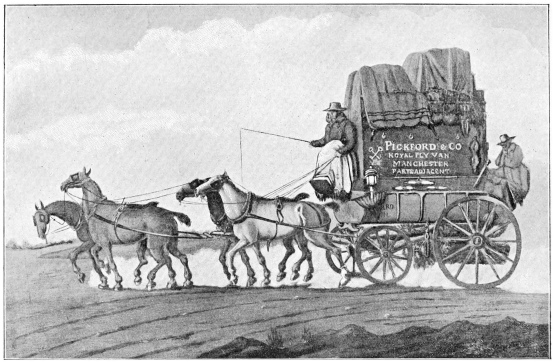

| 17. | Pickford and Co’s Royal Fly-van, about 1820. (From a contemporary Painting) | 139 |

| 18. | The Lioness attacking the Exeter Mail, October 20th, 1816. (After A. Sauerweid) | 153 |

| 19. | Winter: Going North. (After H. Alken) | 163 |

| 20. | Mail-coach in a Snow-drift. (After J. Pollard) | 167 |

| 21. | Mail-coach in a Flood. (After J. Pollard) | 171 |

| 22. | Late for the Mail. (After C. Cooper Henderson, 1848) | 183 |

| 23. | The Short Stage. (After J. Pollard) | 191 |

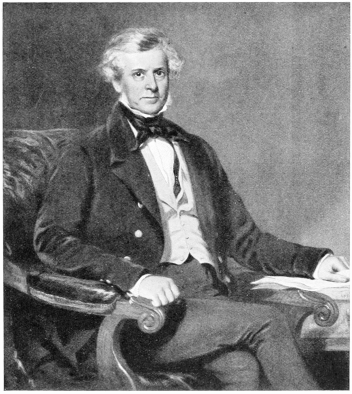

| 24. | William Chaplin. (From the Painting by Frederick Newnham) | 197 |

| 25. | The Canterbury and Dover Coach, 1830. (After G. S. Treguar) | 201 |

| 26. | James Nunn, Horse-buyer and Veterinary Surgeon to William Chaplin. (After J. F. Herring) | 205 |

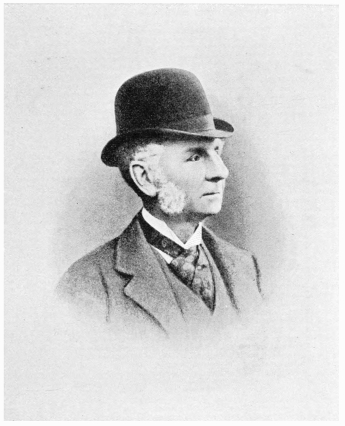

| 27. | William Augustus Chaplin. | 211 |

| 28. | The “Bedford Times,” one of the last Coaches to run, leaving the “Swan Hotel,” Bedford. | 219 |

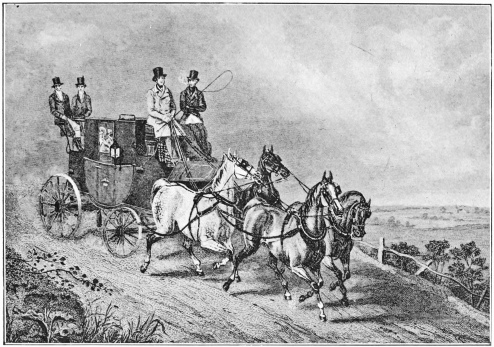

| 29. | Four-in-hand. (After G. H. Laporte) | 243 |

| 30. | Sir St. Vincent Cotton. | 249 |

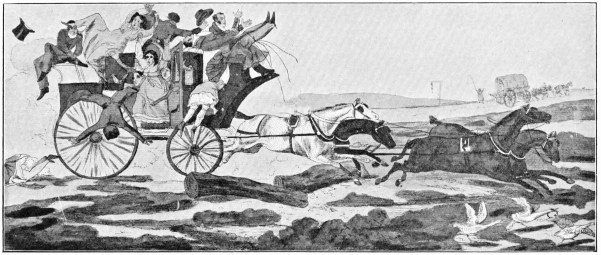

| 31. | The Consequence of being Drove by a Gentleman. (After H. Alken) | 255 |

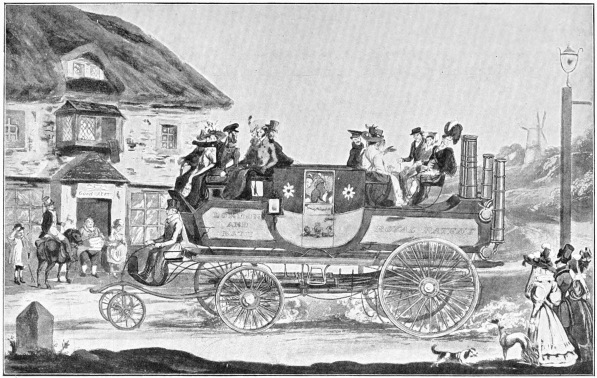

| 32. | Goldsworthy Gurney’s London and Bath Steam-carriage, 1833. (After G. Morton) | 265 |

| 33. | The Last Journey down the Road. (After J. L. Agasse) | 275 |

| 34. | The Chesham Coach, 1796. (From the Painting by Cordery) | 283xi |

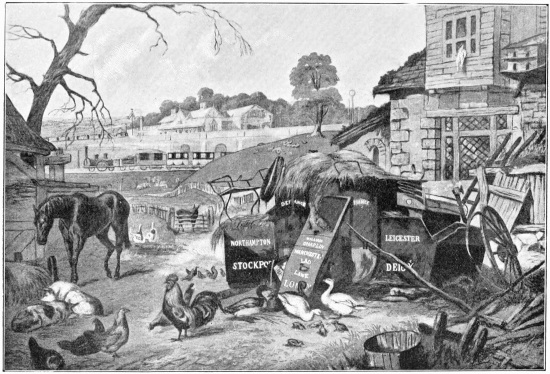

| 35. | The Last of the “Manchester Defiance.” (From a Lithograph) | 287 |

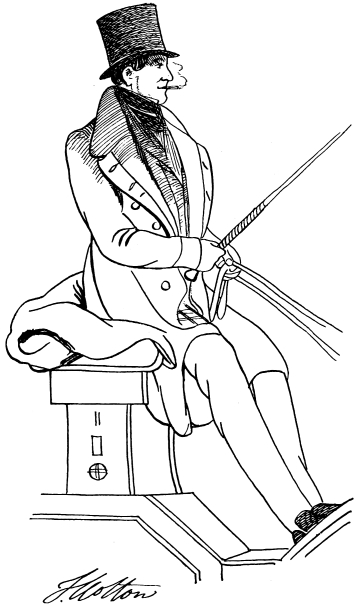

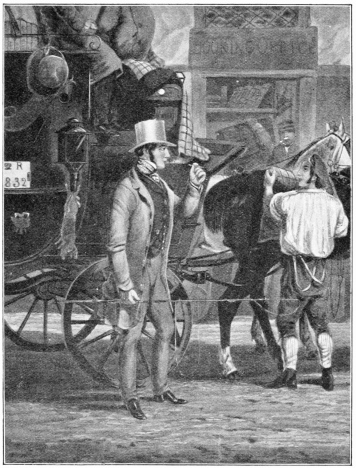

| 36. | The Coachman, 1832. (After H. Alken) | 293 |

| 37. | The Driver, 1852. (After H. Alken) | 297 |

| 38. | The Guard, 1832. (After H. Alken) | 303 |

| 39. | The Guard, 1852. (After H. Alken) | 309 |

| 40. | “All Right!”—The Bath Mail taking up the Mail-bags. (From a contemporary Lithograph) | 341 |

ILLUSTRATIONS IN TEXT

| Vignette | (Title-page) |

| List of Illustrations | ix |

| Stage-coach and Mail in Days of Yore | 1 |

| Mail-coach Halfpenny issued by William Waterhouse | 196 |

| Benjamin Worthy Horne | 221 |

| “A View of the Telegraph”: Dick Vaughan, of the Cambridge “Telegraph.” (From an Etching by Robert Dighton, 1809) | 301 |

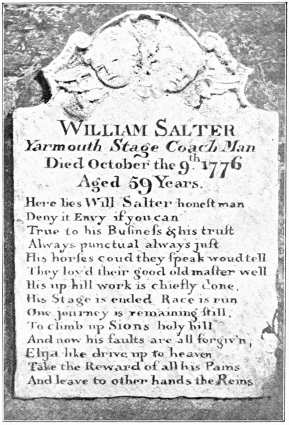

| A Stage-coachman’s Epitaph at Haddiscoe | 316 |

1

STAGE COACH AND MAIL IN DAYS OF YORE

The Bristol Mail opened the mail-coach era by going at eight miles an hour, but that was an altogether exceptional speed, and the average mail-coach journeys were not performed at a rate of more than seven miles an hour until long after the nineteenth century had dawned. In 1812, when Colonel Hawker travelled to Glasgow, it took the mail 57 hours’ continuous unrelaxing effort to cover the 404 miles—three nights and two days’ discomfort. By 1836 the distance had been reduced by eight miles, and the time to 42 hours. By 1838 it was 41 hours 17 minutes. Nowadays it can be done by quickest train in exactly eight hours; the railway mileage 401½ miles. In 1812 it cost an inside passenger all the way to Glasgow, for fare alone, exclusive of tips to coachmen and guards, and the necessary expenditure for food and drink all those weary2 hours, no less than £10 8s.; about 6⅙d. a mile. To-day, £2 18s. franks you through, first-class; or 33s. third—itself infinitely more luxurious than even the consecrated inside of a mail-coach.

The mails starting from London were perfection in coaches, harness and horses; but as the distance from the Metropolis increased so did the mails become more and more shabby. Hawker, travelling north, found them slow and slovenly, the harness generally second-hand, one horse in plated, another in brass harness; and when they did have new (which, he tells us, was very seldom) it was put on like a labourer’s leather breeches, and worn till it rotted, without ever being cleaned.

Of course, very few people ever did, or could have had the endurance to, travel all that distance straight away, and so travel was further complicated, delayed, and rendered more costly by the halts necessary to recruit jaded nature.

Hawker evidently did it in four stages: to Ferrybridge, 179 miles, where he rested the first night and picked up the next mail the following; thence the 65 miles onward to Greta Bridge; on again, 59 miles, to Carlisle; and thence, finally, to Glasgow in another 101 miles. In his diary he gives “a table to show for how much a gentleman and his servant (the former inside, with 14 lb. of luggage; the latter outside, with 7 lb.) may go from London to Glasgow.”

3

| Self. | £ | s. | d. | £ | s. | d. |

| Inside, to Ferrybridge | 4 | 16 | 0 | |||

| Inside, to Greta Bridge | 1 | 12 | 6 | |||

| Inside, to Carlisle | 1 | 9 | 6 | |||

| Inside, to Glasgow | 2 | 10 | 0 | |||

| 10 | 8 | 0 | ||||

| Servant. | ||||||

| Outside, to Ferrybridge | 2 | 10 | 0 | |||

| Outside, to Greta Bridge | 1 | 2 | 0 | |||

| Outside, to Carlisle | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Outside, to Glasgow | 1 | 13 | 0 | |||

| 6 | 5 | 0 | ||||

| Tips. | ||||||

| Inside, 6 long-stage coachmen @ 2s. | 0 | 12 | 0 | |||

| Inside, 12 short-stage coachmen @ 1s. | 0 | 12 | 0 | |||

| Inside, 7 guards @ 2s. each | 0 | 14 | 0 | |||

| Outside, for man, @ half price above | 0 | 19 | 0 | |||

| 2 | 17 | 0 | ||||

| Total | £19 | 10 | 0 | |||

Such were the costs and charges of a gentleman travelling to pay a country visit in 1812, exclusive of hotel bills for self and servant on the way.

The great factor in the acceleration of the mails was the improvement in the roads, a work carried out by the Turnpike Trusts in fear of the Post Office, whose surveyors had the power, under ancient Acts, of indicting roads in bad condition. Great bitterness was stirred up over this matter. The growing commercial and industrial towns—Glasgow prominent among them—naturally desired direct mail-services, and the Post Office, using their needs as means for obtaining, not only roads kept in good condition, but sometimes entirely new roads and short cuts, declined to start such services until such routes were provided. It was not within the power of the Department to compel new4 roads, but only to see that the old ones were maintained; but in the case of Glasgow, to whose merchants a direct service meant much, the Corporation, the Chamber of Commerce, and individual persons contributed large sums for the improvement of the existing road between that city and Carlisle, and a Turnpike Trust was formed for one especial section, where the road was entirely reconstructed. These districts were wholly outside Glasgow’s sphere of responsibilities, but all this money was expended for the purpose of obtaining a direct mail through Carlisle, instead of the old indirect one through Edinburgh; and when obtained, of retaining it in face of the continued threats of the Post Office to take it off unless the road was still further improved. It certainly does not seem to have been a remarkably good road, even after these improvements, for Colonel Hawker, travelling it in 1812, describes it as being mended with large soft quarry-stones, at first like brickbats and afterwards like sand.

But the subscribers who had expended so much were naturally indignant. They pointed out that the district was a wild and difficult one and the Trust poor, in consequence of the sparse traffic. The stage-coaches, they said, had in some instances been withdrawn because they could not hold their own against the competition of the mail, and the Trust lost the tolls in consequence; while the mail, going toll-free and wearing the road down, contributed nothing to5 the upkeep. They urged that the mail should at least pay toll, and in this they were supported by every other Turnpike Trust.

The exemption of mail-coaches from payment of tolls, a relief provided for by the Act of 25th George III., was really a continuation of the old policy by which the postboys of an earlier age, riding horseback and carrying the mailbags athwart the saddle, had always passed toll-free. Even the light mail-cart partook of this advantage, to which there could then have been no real objection. It had been no great matter, one way or the other, with the Turnpike Trusts, for the posts were then infrequent and the revenue to be obtained quite a negligeable quantity; but the appearance of mail-coaches in considerable numbers, running constantly and carrying passengers, and yet contributing nothing towards the upkeep of the roads, soon became a very real grievance to those Trusts situated on the route of the mails, but in outlying parts of the kingdom, little travelled, and where towns were lacking and villages poor, few, and far between. Little wonder, then, that the various Turnpike Trusts in 1810 approached Parliament for a redress of these disabilities. They pointed out that not only was there a greater wear and tear of the roads now the mail-coaches were running, but that travellers, relying on the fancied security of the mails, had deserted the stages, which in many cases had been wholly run off the road. Pennant, writing in 1792, tells how two6 stages plying through the county of Flint, and yielding £40 in tolls yearly, had been unable to compete with the mail, and were thus withdrawn, to the consequent loss of the Trust concerned. It was calculated, so early as 1791, by one amateur actuary, that the total annual loss through mail exemptions was £90,000; but another put it at only £50,000 in 1810.

The case of the remote country trusts was

certainly a hard one. Like all turnpikes, they

were worked under Acts of Parliament, which

prescribed the amounts of tolls to be levied, and

they were, further, authorised to raise money for

the improvement of the roads on the security of

the income arising from these taxes upon locomotion.

The security of money sunk in these quasi-Government

enterprises had always been considered

so good that Turnpike Trust bonds and mortgages

were a very favourite form of investment; but

when Parliament turned a deaf ear to the bitter

cry of the remote Trusts, the position of those

interested in the securities began to be reconsidered.

The woes of these undertakings were

further added to by the action of the Post Office,

which, zealous for its new mail-services, sent out

emissaries to report upon the condition of the

roads. The reports of these officials bore severely

against the very Trusts most hardly hit by the

mail-exemption, and the roads under their control

were frequently indicted for being out of repair,

with the result that heavy fines were inflicted.

It had been suggested that as the Post Office on7

8

9

one hand required better roads, and on the other

deprived the rural Trusts of a great part of their

income, the Government should at least pay off

the debts of the various turnpikes. But nothing

was done; the mails continued to go free, and

in the end the iniquity was perpetrated of suffering

the local Turnpike Acts to lapse and the

roads to be dispiked before the Trusts had paid

off their loans. The greater number of Trust

“securities” therefore became worthless, and the

investors in them ruined.

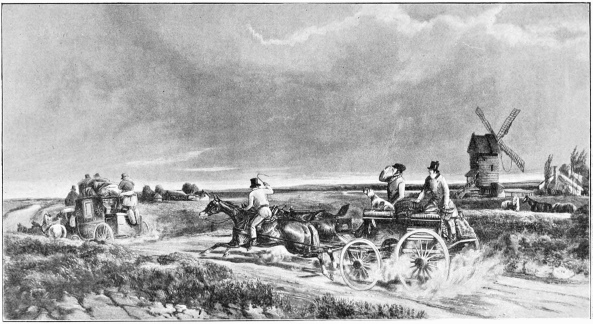

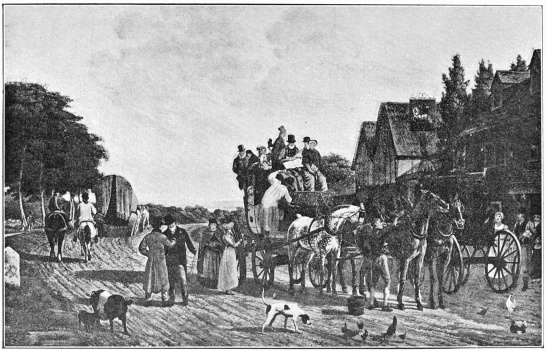

THE WORCESTER MAIL, 1805. After J. A. Atkinson.

Mail-coaches continued to go toll-free to the very last in England, although from 1798 they had paid toll in Ireland. In Scotland, too, the Trusts were treated with tardy justice, and in 1813 an Act was passed repealing the exemption in that kingdom. But what the Post Office relinquished with one hand it took back with the other, clapping on a halfpenny additional postage for each Scotch letter. It was like the children’s game of “tit-for-tat.” But it did not end here. The Trusts raised their tolls against the mail-coaches, and smiled superior. It was then the Department’s call, and it responded by immediately taking off a number of the mails. That ended the game in favour of St. Martin’s-le-Grand.

Although Parliament never repealed the exemption for the whole of the United Kingdom, it caused an estimate to be prepared of the annual cost of paying tolls, should it ever be in a mind to grant the Trusts that relief. It thus appeared,10 from the return made in 1812, that the cost for Scotland would have been £11,229 16s. 8d.; for England, £33,536 2s. 3d.; and for Wales, £5224 3s. 10d.: total, £49,990 2s. 9d. per annum.

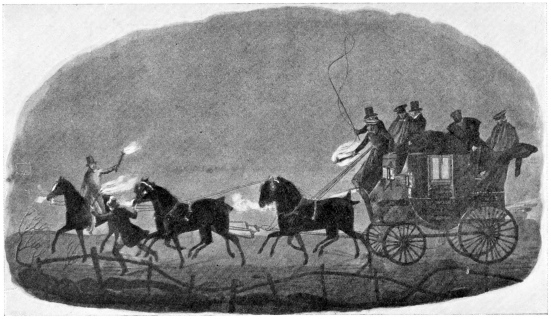

The mails, travelling as they did throughout the night, were subject to many dangers. They were brilliantly lighted, generally with four, and often with five, lamps, and cast a very dazzling illumination upon the highway. It is true that no certainty exists as to the number of lamps mail-coaches carried, and that old prints often show only two; so that the practice in this important matter probably varied on different routes and at various times. But the crack mails at the last certainly carried five lamps—one on either side of the fore upper quarter, one on either side of the fore boot, and another under the footboard, casting a light upon the horses’ backs and harness. These radiant swiftnesses, hurtling along the roads at a pace considerably over ten miles an hour, were highly dangerous to other users of the roads, who were half-blinded by the glare, and, alarmed by the heart-shaking thunder of their approach and fearful of being run down, generally drove into the ditches as the least of two evils. The mails were then, as electric tramcars and high-powered motor-cars are now, the tyrants of the road.

But they were not only dangerous to others. Circumstances that ought never to have been permitted sometimes rendered them perilous to all they carried. The possibilities of that time11 in wrong-doing are shown in the practice of Sir Watkin Williams Wynn (who assuredly was not the only one) being allowed to send his refractory carriage-horses to the mails, to be steadied. On such occasions the passengers from Oswestry found themselves in for a wild start and a rough stage, and Sir Watkin had the steam taken out of his high-mettled horses at an imminent risk to the lives and limbs of the lieges.

From 1825, when the era of the fast day-coaches

began, the mails gradually lost the proud

pre-eminence they had kept for more than forty

years. Even though they had been accelerated

from time to time as roads improved, they went

no quicker than the new-comers, and very often

not so quick, from point to point. They suffered

the disabilities of travelling by night, when careful

coachmen dared not let their horses out to their

best speed, and of being subject to the delays of

Post Office business; and so, although they might,

and did, make wonderful speed between stages,

the showing on the whole journey could not

compare with the times of the fast day-coaches,

which halted only for changing horses and for

meals, and, enjoying the perfection of quick-changing,

often got away in fifty seconds from

every halt. Going at more seasonable hours, the

day-coaches now began to seriously compete with

the mails, whose old-time supporters, although

still sensible of the dignity of travelling by mail,

were equally alive to the comfort and convenience

of going by daylight. Modern writers, enlarging12

upon the times of our ancestors, lay great stress

upon the endurance our hearty grandfathers

“cheerfully” displayed, and show us great, bluff,

burly, red-cheeked men, who enjoyed this long

night-travelling. But that is an absurdity. They

did not enjoy it; they were not all bluff and

burly; and that they welcomed the change that

gave them swift travelling by day instead of night

is obvious from the instant success of the fast day-coaches,

and from the later business-history of the

mails. Mail-contractors, who in the prosperous

days of no competition were screwed down by the

Post Office to incredible mileage figures, began

to grumble; but for long they grumbled in vain.

Even in 1834 the Post Office continued to pay

only 2d. a mile on 42 mails, 1½d. a mile on 34,

and only one received as much as 4d. The Liverpool

and Manchester carried the mailbags for

nothing, and three actually paid the Post Office

for the privilege. At this time the old rule

forbidding more than three outside passengers

on the mails was relaxed. This indulgence began

in Scotland, where the contractors, in consideration

of the sparseness of the population and the

scarcity of chance passengers on the way, were

allowed a fourth outside passenger; and eventually

many of the mails, like the stages, carried

from eight to twelve outsides. This, however, did

not suffice, for those passengers did not often

present themselves; and at last the contractors

really did not care to obtain the Post Office

business, finding it pay better to devote their13

14

15

attention to fast day-coaches on their own

account.

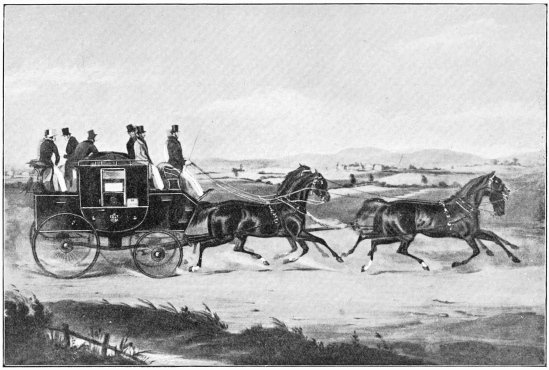

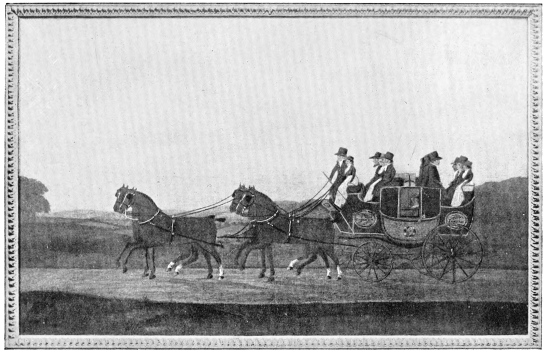

THE MAIL. After J. L. Agasse, 1824.

Thus the Post Office found itself in a novel and unwonted position. Coach-proprietors and contractors, instead of anxiously endeavouring to obtain the mail-contracts, held aloof, and the Post Office surveyors, when renewals were necessary, found they had to make the advances and do the courting. Then the tables were turned with a vengeance! For Benjamin Horne’s “Foreign Mail,” carrying what were called the “black bags” (i.e. black tarpaulin to protect the mail from sea-water) between London and Dover, 1s. 3¾d. per double mile was paid; 11⅙d. for the Carmarthen and Pembroke; and 8d., and then 9d., for the Norwich Mail, by Newmarket, strongly opposed as it was by the Norwich “Telegraph,” and therefore loading badly on that lonely road. For the Chester, originally contracted for at 1s. a mile, then down to 3d., and in 1826 up to 4d., 6d. was paid, on account of passengers going by the direct Holyhead Mail, and the Holyhead itself was raised to the same figure when fast day-stages had begun to run from Shrewsbury.

A Committee of the House of Commons had sat upon this question before these prices were given, and much evidence was taken; but these revised tariffs did by no means end the matter. Substantial contractors would in many instances have nothing to do with the Post Office, and the Department could not run the risk of employing16 irresponsible men who could not be held to their undertakings. In some few instances ordinary night-stages were given the business, and it was seriously proposed to employ the guards of existing stage-coaches to take charge of the bags, but this was never carried out. In the midst of all these worries, when it seemed as though the despatch of the mails must needs, in the altered conditions of the time, be eventually changed from night to day, railways came to relieve official anxieties, which existed not only on account of the increasing cost, but also on the score of the continually growing bulk of mail-matter, piled up to mountainous heights on the roof, instead of, as originally, being easily stowed away in the depths of the hind boot. It was considered a great advantage of the mail-coaches built by Waude in these last days that they were not only built with a low centre of gravity, but that, with a dropped hind axle, they made a deeper and more capacious boot possible, in which were stowed the more valuable portions of the mail. Had railways not at the very cynthia of the moment come to supply a “felt want,” certainly the mails must on many roads have been carried by mail-vans devoted exclusively to the service. But in 1830 the Liverpool and Manchester Railway carried mailbags, and in anticipation of the opening throughout of the London and Birmingham, the first long route, in September 1838, an Act of Parliament was passed on August 14th in that year, authorising the17 conveyance of mails by railways. We must not, however, suppose that such instant advantage was always taken of new methods. That would not be according to the traditions of the Post Office. Accordingly, we find that, although what is now the London and South-Western Railway was opened between Nine Elms and Portsmouth in May 1840, it was not until 1842 that the Portsmouth Mail went by rail. For two years it continued to perform the 73 miles 3 furlongs in 9 hours 10 minutes, when it might have gone by train in 6 hours 10 minutes less.

With these changes, London lost an annual spectacle of considerable interest. From 1791 the procession of the mail-coaches on the King’s birthday had been the grand show occasion of the Post Office year. No efforts and no expense were spared by the loyal contractors (loyal in spite of the ofttimes arbitrary dealings of the Post Office with them) to grace the day; and Vidler and Parratt, who for many years had the monopoly of supplying the coaches, equalled them in the zeal displayed. The coaches were drawn up at twelve, noon, to the whole number of twenty-seven, at the factory on Millbank, beautiful in new paint and new gilding; the Bristol Mail, as the senior, leading, the others in the like order of their establishment. On this occasion the Post Office provided each guard with a new gold-laced hat and scarlet coat, and the mail-contractors who horsed the coaches, not to be outdone, found scarlet coats for their coachmen, in addition to providing new18 harness. The coachmen and guards, unwilling to be beaten in this loyal competition, provided themselves with huge nosegays, as big as cauliflowers. When, as in the reign of William IV., the King’s birthday fell in a pleasant time of the year, the procession of the mails was a beautiful and popular sight, attracting not only the general public, but the very numerous sporting folks, who welcomed the opportunity of seeing at their best, and all together, the one hundred and two noble horses that drew the mails from the Metropolis to all parts of the kingdom. Everything, indeed, was very special to the occasion. Each coach was provided with a gorgeous hammer-cloth, a species of upholstery certainly not in use on ordinary journeys. No one was allowed on the roof, but the coachman and guard had the privilege of two tickets each for friends for the inside. Great, as may be supposed, was the competition for these. For the contractors themselves there was the cold collation provided by Vidler and Parratt at Millbank, at three o’clock, when the procession was over.

THE BRISTOL MAIL AT HYDE PARK CORNER, 1838. After J. Doyle.

The route varied somewhat with the circumstances

of the time, always including the residence

of the Postmaster-General for the time being.

Punctually at noon it started off, headed by a

horseman, and with another horseman between

each coach. Nearing St. James’s Palace, it was

generally reduced to a snail’s pace, for the crowd

always assembled densely there, on the chance

of seeing the King; and the authorities of that19

20

21

period were not clever at clearing a route.

Imagine now the front of Carlton House Palace,

or St. James’s, and the Londoners of that age

assembled in their thousands. The procession

with difficulty approaches, and halts. Two barrels

of porter—Barclay & Perkins’ best—are in

position in front of the Royal residence, and to

each coachman and guard is handed a capacious

pewter pot—it is a sight to make a Good Templar

weep. The King and Queen and the Royal

family now appear at an open window, the King

removing his hat and bowing, to a storm of

applause—as though he had done something

really clever or wonderful. Now the coachman

of the Bristol Mail uncovers, and holding high

the shining pewter, exclaims: “We drink to

the health of His Gracious Majesty: God bless

him!” and suiting the action to the words, dips

his nose into the pot, which in an incredibly

short time is completely inverted and emptied.

Fifty-three other voices simultaneously repeat

the same words, and fifty-three pint pots are

in like manner drained in the twinkling of an

eye. The King and his family now retire, and

the procession prepares to move on; but the

mob, moved by loyalty and the sight of the

beer-barrels, grows clamorous: “King, King!

Queen, Queen!” cry a thousand voices; while

a thousand more yell, “Beer, beer!” When at

length the King does return, to bow once more,

he gazes upon two thousand people struggling

for two half-empty barrels, which in the scuffle22

have upset, and speedily become empty. Meanwhile

the coaches have moved off, to complete

their tour to the General Post Office, and thence

back to Millbank.

These processions, from some cause or another not now easily to be discovered, were omitted in 1829 and 1830. May 17th, 1838, when twenty-five mails paraded, was the last occasion; for already the railway was threatening the road, and when Queen Victoria’s birthday recurred the ranks of the mails were sadly broken.

This memorable year, 1837, then, was the last unbroken year of the mail-coaches starting from London. Since September 23rd, 1829, when the old General Post Office in Lombard Street was deserted for the great building in St. Martin’s-le-Grand, they had come and gone. The first ever to enter its gates, as the result of keen competition, had been the up Holyhead Mail of that date; the last was the Dover Mail, in 1844.

The mail-coaches loaded up about half-past seven at their respective inns, and then assembled at the Post Office Yard to receive the bags. All, that is to say, except seven West of England mails—the Bath, Bristol, Devonport, Exeter, Gloucester, Southampton and Stroud—whose coaches started from Piccadilly, the bags being conveyed to them at that point by mail-cart. There were thus twenty-one coaches starting nightly from the General Post Office precisely at 8 o’clock. Here is a list of the mails setting out every night throughout the year:—

23

A List of Mail-Coaches starting nightly from London in 1837.

| Mails. | Miles. | Inn whence starting. | Time. | Average speed per hour, stops included. | ||

| H. | M. | M. | F. | |||

| Bristol | 122 | Swan with Two Necks | 11 | 45 | 10 | 3 |

| Devonport (“Quicksilver”) | 216 | Spread Eagle, Gracechurch Street | 21 | 14 | 10 | 1¾ |

| Birmingham | 119 | King’s Arms, Holborn Bridge | 11 | 56 | 9 | 7¾ |

| Bath | 109 | Swan with Two Necks | 11 | 0 | 9 | 7¾ |

| Manchester | 187 | ” ” ” | 19 | 0 | 9 | 6⅔ |

| Halifax | 196 | ” ” ” | 20 | 5 | 9 | 6 |

| Liverpool | 203 | ” ” ” | 20 | 50 | 9 | 6 |

| Holyhead | 261 | ” ” ” | 26 | 55 | 9 | 5⅔ |

| Norwich, by Ipswich | 113 | ” ” ” | 11 | 38 | 9 | 5⅔ |

| Exeter | 173 | ” ” ” | 18 | 12 | 9 | 4 |

| Hull (New Holland Ferry) | 172 | Spread Eagle, Gracechurch Street | 18 | 12 | 9 | 4 |

| Leeds | 197 | Bull and Mouth | 20 | 52 | 9 | 3½ |

| Glasgow | 396 | ” ” | 42 | 0 | 9 | 3⅖ |

| Southampton | 80 | Swan with Two Necks | 8 | 30 | 9 | 3⅓ |

| Edinburgh | 399 | Bull and Mouth | 42 | 23 | 9 | 3⅓ |

| Chester | 190 | Golden Cross | 20 | 16 | 9 | 3 |

| Gloucester and Carmarthen | 224 | ” ” | 24 | 0 | 9 | 2⅔ |

| Worcester | 115 | Bull and Mouth | 12 | 20 | 9 | 2½ |

| Yarmouth | 124 | White Horse, Fetter Lane | 13 | 30 | 9 | 1½ |

| Louth | 148 | Bell and Crown, Holborn | 15 | 56 | 9 | 0 |

| Norwich, by Newmarket | 118 | Belle Sauvage | 13 | 5 | 9 | 0 |

| Stroud | 105 | Swan with Two Necks | 11 | 47 | 9 | 0 |

| Wells | 133 | Bell and Crown | 14 | 43 | 9 | 0 |

| Falmouth | 271 | Bull and Mouth | 31 | 55 | 8 | 4 |

| Dover | 73 | Golden Cross | 8 | 57 | 8 | 1¼ |

| Hastings | 67 | Bolt-in-Tun, Fleet Street | 8 | 15 | 8 | 0 |

| Portsmouth | 73 | White Horse | 9 | 10 | 7 | 7-5/7 |

| Brighton | 55 | Blossoms Inn | 7 | 20 | 7 | 4 |

24 With the exception of the Brighton, Portsmouth, Dover and Hastings, they were all splendidly-appointed four-horse coaches; but those four places being only at short distances, speed was unnecessary, and they were only provided with pair-horse mails. Had a speed similar to that maintained on most other mails been kept up, letters and passengers would have reached the coast in the middle of the night.

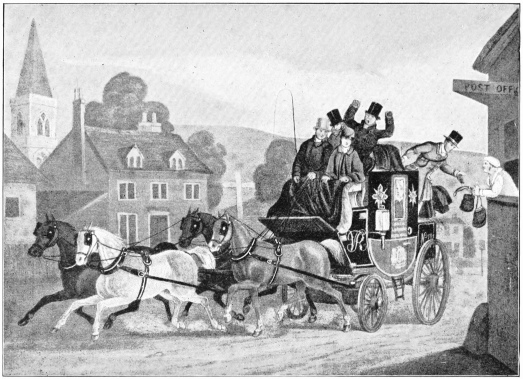

The so-called “Yarmouth Mail” was, we are told by those who travelled on it, an ordinary stage-coach, carrying the usual four inside and twelve outside, chartered by the Post Office to carry the mail-bags; but the old print, engraved here, does not bear out that contention.

The arrival of the mails in London was an early morning affair. First of all came the Leeds, at five minutes past four, followed at an interval of over an hour—5.15—by the Glasgow, and then, at 5.39, by the Edinburgh. All arrived by 7 o’clock.

There was then, as now, no Sunday delivery of letters in London, and Saturday nights were, by consequence, saturnalias for the up-mails. Although the clock might have been set with accuracy by their passing at any other time, their coming into London on Sundays was a happy-go-lucky, chance affair. The coachmen would arrange to meet on the Saturday nights at such junctions of the different routes as Andover, Hounslow, Puckeridge, and Hockliffe, and so in company have what they very descriptively termed a “roaring time.”

25

THE YARMOUTH MAIL, AT THE “COACH AND HORSES,” ILFORD.

After J. Pollard.

26

27

In 1836 the fastest mail ran on a provincial

route. This was the short 28-miles service

between Liverpool and Preston, maintained at

10 miles 5 furlongs an hour. The slowest was

the 19-miles Canterbury and Deal, at 6 miles

an hour, including stops for changing. The

average speed of all the mails was as low as

8 miles 7 furlongs an hour.

In 1838 there were 59 four-horse mails in England and Wales, 16 in Scotland, and 29 in Ireland, in addition to a total number of 70 pair-horse: some 180 mails in all. It was in this year that—the novelty of railways creating a desire for fast travelling—the Post Office yielded to the cry for speed, and, abandoning the usual conservative attitude, went too far in the other direction, overstepping the bounds of common safety. For some time the mails between Glasgow and Carlisle, and Carlisle and Edinburgh were run to clear 11 miles an hour, which meant an average pace of 13 miles an hour. These were popularly called the “calico mails,” because of their lightness. The time allowed between Carlisle and Glasgow, 96 miles, was 8 hours 32 minutes, and it was a sight to see it come down Stanwix Brow on a summer evening. It met, however, with so many accidents that cautious folk always avoided it, preferring the orthodox 10 miles an hour—especially by lamplight in the rugged Cheviots. Even at that pace there had been more than enough risk, as these incidents from28 Post Office records of three years earlier clearly show:—

| 1835. February |

5. Edinburgh and Aberdeen Mail overturned. |

| 9. Devonport Mail overturned. | |

| 10. Scarborough and York Mail overturned. | |

| 16. Belfast and Enniskillen Mail overturned. | |

| 16. Dublin and Derry Mail overturned. | |

| 17. Scarborough and Hull Mail overturned. | |

| 17. York and Doncaster Mail overturned. | |

| 20. Thirty-five mail-horses burnt alive at Reading. | |

| 24. Louth Mail overturned. | |

| 25. Gloucester Mail overturned. |

No place was better served by the Post Office than Exeter in the last years of the road, and few so well. Before 1837 it had no fewer than three mails, and in that year a fourth was added. All four started simultaneously from the General Post Office, and reached the Queen City of the West within a few hours of one another every day. On its own merits, Exeter did not deserve or need all these travelling and postal facilities, and it was only because it stood at the converging-point of many routes that it obtained them. Only one mail, indeed, was dedicated especially to Exeter, and that was the last-established, the “New Exeter,” put on the road in 1837. The others continued to Devonport or to Falmouth, then a port, a mail-packet and naval station of great prominence, where the West Indian mails landed, and whence they were shipped. To the mail-coaches making for Devonport and Falmouth, Exeter was, therefore, only an incident.

29

THE “QUICKSILVER” DEVONPORT MAIL, PASSING KEW BRIDGE.

After J. Pollard.

30

31

The “Old Exeter” Mail, continued on to

Falmouth, kept consistently to the main Exeter

Road, through Salisbury, Dorchester and Bridport.

Before 1837 it had performed the journey to

Exeter in 20 hours and to Falmouth in 34¾ hours,

but was then accelerated one hour as between

London and Exeter, and although slightly decelerated

onwards, the gain on the whole distance

was 49 minutes.

Five minutes in advance of this ran the “Quicksilver” Devonport Mail, as far as Salisbury, where, until 1837, it branched off, going by Shaftesbury, Sherborne and Yeovil, a route 5¾ miles shorter than the other. It was 1¾ hours quicker than the “Old Exeter” as far as that city. Here is the time-table of the “Quicksilver” at that period, to Exeter:—

Leaving General Post Office at 8 p.m.

| Miles. | Places. | Due. |

| 12 | Hounslow | 9.12 p.m. |

| 19 | Staines | 9.56” |

| 29 | Bagshot | 11.0 ” |

| 67 | Andover | 2.42 a.m. |

| 84 | Salisbury | 4.27” |

| 105 | Shaftesbury | 6.41” |

| 126 | Yeovil | 8.56” |

| 135 | Crewkerne | 10.12” |

| 143 | Chard | 11.0 ” |

| 156 | Honiton | 12.31 p.m. |

| 173 | Exeter | 2.14” |

Thus 18 hours 14 minutes were allowed for the 173 miles. In 1837 the “Quicksilver” was put on the “upper road” by Amesbury and Ilminster, and her pace again accelerated; this time by32 1 hour 38 minutes to Exeter and 4 hours 39 minutes to Falmouth. This then became the fastest long-distance mail in the kingdom, maintaining a speed, including stops, of nearly 10¼ miles an hour between London and Devonport. It should be remembered, when considering the subject of speed, that the mails had not only to change horses and stay for supper and breakfast, like the stage-coaches, but also had to call at the post offices to deliver and collect the mailbags, and all time so expended had to be made up. The “Quicksilver” must needs have gone some stages at 12 miles an hour.

Time also had to be kept in all kinds of weather, and the guard—who was the servant of the Post Office, and not, as the coachman was, of the mail-contractors—was bound to see that time was kept, and had power, whenever it was being lost, to order out post-horses at the expense of the contractors. Six, and sometimes eight, horses were often thus attached to the mails. The route of the “Quicksilver” from 1837 was according to the following time-bill:—

Leaving General Post Office at 8 p.m.

| Miles. | Places. | Due. |

| 12 | Hounslow | 9.8 p.m. |

| 19 | Staines | 9.48” |

| 29 | Bagshot | 10.47” |

| 67 | Andover | 2.20 a.m. |

| 80 | Amesbury | 3.39” |

| 90 | Deptford Inn | 4.34” |

| 97 | Chicklade | 5.15 a.m. |

| 125 | Ilchester | 7.50” |

| 137 | Ilminster | 8.58” |

| 154 | Honiton | 11.0 ” |

| 170 | Exeter | 12.34 p.m. |

| Time: 16 hours 34 minutes. | ||

The complete official time-bill for the whole distance is appended:—

33

Time-Bill, London, Exeter and Devonport (“Quicksilver”) Mail, 1837.

| Contractors’ Names. |

Number of Passengers. |

Stages. | Time Allowed. |

Despatched from the General Post Office, the of , 1837 at 8 p.m. | |

| In. | Out. | M. F. | H. M. | Coach No. {With timepiece sent out {safe, No. to . | |

| Arrived at the Gloucester Coffee-House at . | |||||

| Chaplin | { 12 2 | } | Hounslow. | ||

| { 7 1 | } 2 47 | Staines. | |||

| { 9 7 | } | Bagshot. Arrived 10.47 p.m. | |||

| Company | { 9 1 | } | Hartford Bridge. | ||

| { 10 1 | } 2 54 | Basingstoke. | |||

| { 8 0 | } | Overton. | |||

| { 3 5 | } | Whitchurch. Arrived 1.41 a.m. | |||

| Broad | { 6 7 | 0 39 | Andover. Arrived 2.20 a.m. | ||

| { 13 7 | 1 19 | Amesbury. Arrived 3.39 a.m. | |||

| Ward | 9 5 | 0 55 | Deptford Inn. Arrived 4.34 a.m. | ||

| Davis | { 0 5 | } | Wiley. | ||

| { 6 5 | } 0 41 | Chicklade. Arrived 5.15 a.m. | |||

| (Bags dropped for Hindon, 1 mile distant.) | |||||

| Whitmash | { 6 6 | } | Mere. | ||

| { 7 0 | } 2 59 | Wincanton. | |||

| { 13 4 | } | Ilchester. | |||

| { 4 1 | } | Cart Gate. Arrived 8.14 a.m. | |||

| Jeffery | { 2 6 | } | Water Gore, 6 miles from South Petherton. | ||

| { | } 0 44 | Bags dropped for that place. | |||

| { 5 1 | } | Ilminster. Arrived 8.58 a.m. | |||

| Soaring | 8 1 | } 0 25 | Breakfast 25 minutes. Dep. 9.23 | ||

| } 0 46 | Yarcombe, Heathfield Arms. Arrived 10.9 a.m. | ||||

| Wheaton | 8 7 | 0 51 | Honiton. Arrived 11 a.m. | ||

| Cockram | { 16 4 | 1 34 | Exeter. Arrived 12.34 p.m. | ||

| { | 0 10 | Ten minutes allowed. | |||

| { 10 3 | } | Chudleigh. | |||

| { 9 3 | } 1 57 | Ashburton. Arrived 2.41 p.m. | |||

| Elliott | {13 2 | } | Ivybridge. | ||

| { 6 6 | } 2 33 | Bags dropped at Ridgway for Plympton, 3 furlongs distant. | |||

| { 4 0 | } | Plymouth. Arrived at the Post | |||

| { 1 7 | } | Office, Devonport, the of , 1837, at 5.14 p.m. by timepiece. At by clock. | |||

| 216 1 | 21 14 | Coach No. { Delivered timepiece arr. . { safe, No. to . | |||

The time of working each stage is to be reckoned from the coach’s arrival, and as any lost time is to be recovered in the course of the stage, it is the coachman’s duty to be as expeditious as possible, and to report the horsekeepers if they are not always ready when the coach arrives, and active in getting it off. The guard is to give his best assistance in changing, whenever his official duties do not prevent it.

By command of the Postmaster-General.

George Louis, Surveyor and Superintendent.

34 The “New Exeter” Mail went at the moderate inclusive speed of 9 miles an hour, and reached Exeter, where it stopped altogether, 1 hour 38 minutes later than the “Quicksilver.” The fourth of this company went a circuitous route down the Bath Road to Bath, Bridgewater, and Taunton, and did not get into Exeter until 3.57 p.m. Halting ten minutes, it went on to Devonport, and stopped there at 10.5 that night.

The tabulated form given on opposite page will clearly show how the West of England mails went in 1837.

The starting of the “Quicksilver” and the other West-country mails was a recognised London sight. That of the “Telegraph” would have been also, only it left Piccadilly at 5.30 in the morning, when no one was about besides the unhappy passengers, except the stable-helpers. Chaplin, who horsed the “Quicksilver” and other Western mails from town, did not start them from the General Post Office, but from the Gloucester Coffee-House, Piccadilly. The mail-bags were brought from St. Martin’s-le-Grand in a mail-cart, and the City passengers in an omnibus. The mails set out from Piccadilly at 8.30 p.m.

35

The West of England Mails, 1837.

| Miles. | Places. | Old Exeter Mail, continued to Falmouth. |

Devonport (“Quicksilver”) Mail, continued to Falmouth. |

New Exeter Mail. |

Devonport Mail, by Bath and Taunton. |

| General Post Office, | |||||

| London dep. | 8.0 p.m. | 8.0 p.m. | 8.0 p.m. | 8.0 p.m. | |

| 12 | Hounslow arr. | 9.12” | |||

| 19 | Staines | 9.56” | |||

| 23 | Slough | ||||

| 29 | Maidenhead | 10.40” | |||

| 58 | Newbury | 1.53 a.m. | |||

| 77 | Marlborough | 3.43” | |||

| 91 | Devizes | 5.6 ” | |||

| 109 | Bath | 7.0 ” | |||

| 149 | Bridgewater | 11.30” | |||

| 160 | Taunton | 12.35 p.m. | |||

| 180 | Cullumpton | 2.42” | |||

| 29 | Bagshot | 10.47 p.m. | |||

| 67 | Andover | 2.20 a.m. | 2.42 a.m. | ||

| 84 | Salisbury | 4.52 a.m. | 4.27” | ||

| 124½ | Dorchester | 8.57” | 8.53” | ||

| 126 | Yeovil | ||||

| 137 | Bridport | 10.5 ” | 11.0 ” | ||

| 143 | Chard | ||||

| 80 | Amesbury | 3.39” | |||

| 125 | Ilchester | 7.50” | |||

| Honiton | 11.0 ” | 12.31 p.m. | |||

| Exeter {arr. | 2.59 p.m. | 12.34 p.m. | 2.12” | 3.57” | |

| {dep. | 3.9 ” | 12.44” | 4.7 ” | ||

| 210 | Newton Abbot arr. | 6.33” | |||

| 218 | Totnes | 7.25” | |||

| 190 | Ashburton | 2.41” | |||

| 214 | Plymouth | 5.5 ” | |||

| Devonport {arr. | 5.14” | 10.5 ” | |||

| {dep. | 5.41” | ||||

| 234 | Liskeard arr. | 7.55” | |||

| 246 | Lostwithiel | 9.12” | |||

| 252 | St. Austell | 10.20” | |||

| 266 | Truro | 11.55” | |||

| 271 | Falmouth | 3.55 a.m. | 1.5 a.m. | ||

| 31 h. 55 m. | 29 h. 5 m. | 18 h. 12 m. | 26 h. 5 m. |

It was at Andover that the “Quicksilver,” from 1837, leaving its contemporary mails, climbed up past Abbot’s Ann to Park House and the bleak Wiltshire downs, along a lonely road, and finally came, up hill, out of Amesbury to the most exposed part of Salisbury Plain, at36 Stonehenge, in the early hours of the morning. The “Quicksilver” was a favourite subject with the artists of that day, who were never weary of pictorially representing it. They have shown it passing Kew Bridge, and the old “Star and Garter,” on the outward journey, in daylight—presumably the longest day in the year, because it did not reach that point until 9 p.m. Two of them have, separately and individually, shown us the famous attack by the lioness in 1816; and two others have pictured it on the up journey, passing Windsor Castle, and entering the City at Temple Bar; but no one has ever represented the “Quicksilver” passing beneath that gaunt and storm-beaten relic of a prehistoric age, Stonehenge. One of them, however, did a somewhat remarkable thing. The picture of the “Quicksilver” passing within sight of Windsor was executed and published in 1840, two years after the gallant old mail had been taken off that portion of the road, to be conveyed by railway. Perhaps the print was, so to speak, a post-mortem one, intended to keep the memory of the old days fresh in the recollection of travellers by the mail.

The London and Southampton Railway was

opened to Woking May 23rd, 1838, and to Winchfield

September 24th following, and by so much

the travels of the “Quicksilver” and the other

West-country coaches were shortened. For some

months they all resorted to that station, and then

to Basingstoke, when the line was opened so far.37

38

39

June 10th, 1839. This shortening of the coach

route was accompanied by the following advertisement

in the Times during October 1838, the

forerunner of many others:—

THE “QUICKSILVER” DEVONPORT MAIL, ARRIVING AT TEMPLE BAR, 1834. After C. B. Newhouse.

“Bagshot, Surrey—49 Horses and harness. To Coach Proprietors, Mail Contractors, Post Masters, and Others.—To be Sold by Auction, by Mr. Robinson, on the premises, ‘King’s Arms’ Inn, Bagshot, on Friday, November 2, 1838, at twelve o’clock precisely, by order of Mr. Scarborough, in consequence of the coaches going per Railway.

“About Forty superior, good-sized, strengthy, short-legged, quick-actioned, fresh horses, and six sets of four-horse harness, which have been working the Exeter ‘Telegraph,’ Southampton and Gosport Fast Coaches, and one stage of the Devonport Mail. The above genuine Stock merits the particular Attention of all Persons requiring known good Horses, which are for unreserved sale, entirely on Account of the Coaches being removed from the Road to the Railway.”

In Thomas Sopwith’s diary we find this significant passage: “On the 11th May, 1840, the coaches discontinued running between York and London, although the railways were circuitous.” Thus the glories of the Great North Road began to fade, but it was not until 1842 that the Edinburgh Mail was taken off the road between London, York, and Newcastle. July 5th, 1847, witnessed the last journey of the mail on that40 storied road, in the departure of the coach from Newcastle-on-Tyne for Edinburgh. The next day the North British Railway was opened.

The local Derby and Manchester Mail was one of the last to go. It went off in October 1858. But away up in the far north of Scotland, where Nature at her wildest, and civilisation and population at their sparsest, placed physical and financial obstacles before the railway engineers, it was not until August 1st, 1874, that the mail-coach era closed, in the last journey of the mail-coach between Wick and Thurso. That same day the Highland Railway was opened, and in the whole length and breadth of England and Scotland mail-coaches had ceased to exist.

THE “QUICKSILVER” DEVONPORT MAIL, PASSING WINDSOR CASTLE.

After Charles Hunt, 1840.

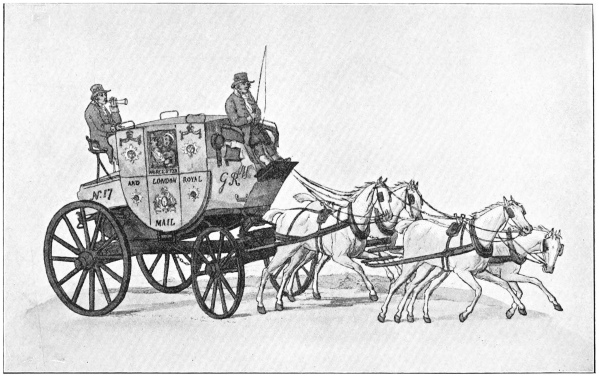

The mail-coaches in their prime were noble

vehicles. Disdaining any display of gilt lettering

or varied colour commonly to be seen on the competitive

stage-coaches, they were yet remarkably

striking. The lower part of the body has been

variously described as chocolate, maroon, and

scarlet. Maroon certainly was the colour of the

later mails, and “chocolate” is obviously an error

on the part of some writer whose colour-sense was

not particularly exact; but we can only reconcile

the “scarlet” and “maroon” by supposing that

the earlier colouring was in fact the more vivid

of the two. The fore and hind boots were black,

together with the upper quarters of the body,

and were saved from being too sombre by the

Royal cipher in gold on the fore boot, the number

of the mail on the hind, and, emblazoned on the41

42

43

upper quarters, four devices eloquent of the majesty

of the united kingdoms and their knightly orders.

There shone the cross of St. George, with its

encircling garter and the proud motto, “Honi soit

qui mal y pense”; the Scotch thistle, with the

warning “Nemo me impune lacessit”; the shamrock

and an attendant star, with the Quis

separabit? query (not yet resolved); and three

Royal crowns, with the legend of the Bath,

“Tria juncta in uno.” The Royal arms were

emblazoned on the door-panels, and old prints

show that occasionally the four under quarters

had devices somewhat similar to those above.

The name of each particular mail appeared in

unobtrusive gold letters. The under-carriage and

wheels were scarlet, or “Post Office red,” and the

harness, with the exception of the Royal cypher

and the coach-bars on the blinkers, was perfectly

plain.

One at least of the mail-coaches still survives. This is a London and York mail, built by Waude, of the Old Kent Road, in 1830, and now a relic of the days of yore treasured by Messrs. Holland & Holland, of Oxford Street. Since being run off the road as a mail, it has had a curiously varied history. In 1875 and the following season, when the coaching revival was in full vigour, it appeared on the Dorking Road, and so won the affections of Captain “Billy” Cooper, whose hobby that route then was, that he had an exact copy built. In the summer of 1877 it was running between Stratford-on-Avon44 and Leamington. In 1879 Mr. Charles A. R. Hoare, the banker, had it at Tunbridge Wells, and also ordered a copy. Since then the old mail-coach has been in retirement, emerging now and again as the “Old Times” coach, to emphasise the trophies of improvement and progress in the Lord Mayor’s Shows of 1896, 1899 and 1901, in the wake of electric and petrol motor-cars, driven and occupied by coachmen and passengers dressed to resemble our ancestors of a hundred years ago.

MAIL-COACH BUILT BY WAUDE, 1830.

Now in possession of Messrs. Holland & Holland.

The coach is substantially and in general lines

as built in 1830. The wheels have been renewed,

the hind boot has a door inserted at the back,

and the interior has been relined; but otherwise

it is the coach that ran when William IV. was

king. It is a characteristic Waude coach, low-hung,

and built with straight sides, instead of

the bowed-out type common to the products

of Vidler’s factory. It wears, in consequence, a

more elegant appearance than most coaches of

that time; but it must be confessed that what

it gained in the eyes of passers-by it must have

lost in the estimation of the insides, for the

interior is not a little cramped by those straight

sides. The guard’s seat on the “dickey”—or

what in earlier times was more generally known

as the “backgammon-board”—remains, but his

sheepskin or tiger-skin covering, to protect his

legs from the cold, is gone. The trapdoor into

the hind boot can be seen. Through this the

mails were thrust, and the guard sat throughout45

46

47

the journey with his feet on it. Immediately

in front of him were the spare bars, while above,

in the still-remaining case, reposed the indispensable

blunderbuss. The original lamps, in their

reversible cases, remain. There were four of

them—one on either fore quarter, and one on

either side of the fore boot, while a smaller one

hung from beneath the footboard, just above the

wheelers. The guard had a small hand-lamp of

his own to aid him in sorting his small parcels.

The door-panels have apparently been repainted

since the old days, for, although they still

keep the maroon colour characteristic of the

mail-coaches, the Royal arms are gone, and in

their stead appears the script monogram, in

gold, “V.R.”

48

In 1773, the Reverend James Murray, Minister of the High Bridge Meeting House at Newcastle, published a little book which he was pleased to call The Travels of the Imagination; or, a True Journey from Newcastle to London, purporting to be an account of an actual trip taken in 1772. I do not know how his congregation received this performance, but the inspiration of it was very evidently drawn from Sterne’s Sentimental Journey, then in the heyday of its success and singularly provocative of imitations—all of them extraordinarily thin and poor. Sentimental travellers, without a scintilla of the wit that jewelled Sterne’s pages, gushed and reflected in a variety of travels, and became a public nuisance. Surely no one then read their mawkish products, any more than they do now.

Murray’s book was, then, obviously, to any one who now dips into it, as trite and jejune as the rest of them; but it has now, unlike its fellows, an interesting aspect, for the reason that he gives49 details of road-travelling life which, once commonplace enough, afford to ourselves not a little entertainment. Equally entertaining, too, and full of unconscious humour, are those would-be eloquent rhapsodies of his which could only then have rendered him an unmitigated bore. It should be noted here that although his picture of road-life is in general reliable enough, we must by no means take him at his word when he says he journeyed all the way from Newcastle to London. We cannot believe in a traveller making that claim who devotes many pages to the first fifteen miles between Newcastle and Durham, and yet between Durham and Grantham, a distance of a hundred and fifty miles, not only finds nothing of interest, but fails to tell us whether he went by the Boroughbridge or the York route, and mentions nothing of the coach halting for the night between the beginning of the journey at Newcastle, and the first specified night’s halt at Grantham, a hundred and sixty-five miles away. Those were the times when the coaches inned every night, and not until the “Wonder” London and Shrewsbury Coach was started, in 1825, did any coach ever succeed in doing much more than a hundred miles a day. So much in adverse criticism. But while a very casual glance is sufficient to expose his pretensions of having made the entire journey in this manner, it is equally evident that he knew portions of the road, and that he was conversant with the manners and customs that then obtained along it—as no one50 then could help being. The fare between Newcastle and London, the lengthy halts on the way, and the manner in which the passengers often passed the long evenings at the towns where they rested for the night—witnessing any theatrical performance that offered—are extremely interesting, as also is the curious sidelight thrown upon the fact that actors—technically, in the eyes of the law, “rogues and vagabonds”—were then actually so regarded. How poorly considered the theatrical profession then was, is, of course, well known; but it is curious thus to come upon a reference to the fact that London theatres then had long summer vacations, in which the actors and actresses must starve if they could not manage to pick up a meagre livelihood by barnstorming in the country; as here we see them doing.

So much by way of preface. Now let us see what our author has to say.

To begin with, he, like many another before and since, found it disagreeable to be wakened in the morning. When a person is enjoying sweet repose in his bed, to be suddenly awakened by the rude, blustering voice of a vociferous ostler was distinctly annoying. More annoying still, however, to lose the coach; and so there was no help for it, provided the stage was to be caught. The morning was very fine when the passengers, thus untimely roused, entered the coach. Nature smiled around them, who only yawned in her face in return. Pity, thought our author, that they were51 not to ride on horseback: they could then enjoy the pleasures of the morning, snuff the perfumes of the fields, hear the music of the grove and the concert of the wood.

These reflections were cut short by the crossing of the Tyne by ferry. The bridge had fallen on November 17th, 1771, and the temporary ferry established from the Swirl, Sandgate, to the south shore was the source of much inconvenience and delay. The coach was put across on a raft or barge, but in directing operations to that end, the ferryman was not to be hurried. One had to wait the pleasure of that arbitrary little Bashaw, who would not move beyond the rule of his own authority, or mitigate the sentence of those who were condemned to travel in a stage-coach within a ferry-boat.

Our author, as he hated every idea of slavery and oppression, was not a little offended at the expressions of authority used on this occasion by the august legislator of the ferry. The passengers were now in the barge, and obliged to sit quiet until this tyrant gave orders for departure. The vehicle for carrying coach and passengers across the river was the most tiresome and heavy that ever was invented. Four rowers in a small boat dragged the ponderous ferry across the river, very slowly and with great exertions, and almost an hour was consumed in thus breasting the yellow current of the broad and swiftly-running Tyne. Meanwhile, there was plenty of time to reflect on what might happen on the passage, and abundant52 opportunity for putting up a few ejaculations to Heaven to preserve them all from the dangers of ferryboats and tyrants.

But the voyage at last came to an end. So soon as they were landed on the south side of the river Tyne, they were saluted by a blackbird, who welcomed them to the county of Durham. It seemed to take pleasure in seeing them fairly out of the domains of Charon, and whistled cheerfully on their arrival. “Nature,” said Mr. James Murray to himself, “is the mistress of real pleasure: this same blackbird cannot suffer us to pass by without contributing to our happiness. Liberty (he continued) seems to be the first principle of music. Slaves can never sing from the heart.”

No: they sing, like everyone else, from the throat.

But these observations carried them beyond Gateshead and to the ascent of the Fell, along whose steep sides the pleasures of the morning increased upon them. The whins and briars sent forth a fragrance exceedingly delightful, and on every side of the coach peerless drops of dew hung dangling upon the blossoms of the thorns, adding to the perfume. Aurora now began to streak the western sky—something wrong with the solar system that morning, for the sun commonly rises in the east—and the spangled heavens announced the advent of the King of Day. Sol at last appeared, and spread his healthful beams over the hills and valleys, and the wild beasts now53 retired to their dens, and those timorous animals that go abroad in the night to seek their food were also withdrawn to the thickets. The hares, as an exception—and yet this was not the lunatic month of March—were skipping across the lawns, tasting the dewy glade for their morning’s repast. The skylark was skylarking—or, rather, was already mounted on high, serenading his dame with mirthful glee and pleasure. (Here follow two pages of moral reflections on skylarks and fashionable debauchees, with conclusions in favour of the larks, and severe condemnation of “libidinous children of licentiousness,” who are bidden “go to the lark, ye slaves of pollution, and be wise. He does not stroll through the grove or thicket to search for some new amour, but keeps strictly to the ties of conjugal affection, and cherishes the partner of his natural concerns.”)

In the midst of these idyllic contemplations, a grave and solemn scene opened to the view. Hazlett, who had robbed the mail in 1770, hung on a gibbet at the left hand. “Unfortunate and infatuated Hazlett! Hadst thou robbed the nation of millions, instead of robbing the mail and pilfering a few shillings from a testy old maid, thou hadst not been hanging, a spectacle to passers-by and a prey to crows. Thy case was pitiable—but there was no mercy: thou wast poor, and thy sin unpardonable. Hadst thou robbed to support the Crown, and murdered for the Monarchy, thou might’st have been yet alive.”

The place where Hazlett hung, the writer54 considered to be the finest place in the world for a ghost-walk. “At the foot of a wild romantic mountain, near the side of a small lake, are his remains; his shadow appears in the water and suggests the idea of two malefactors. The imagination may easily conjure up his ghost. Many spirits have been seen in wilds not so fit for the purpose. This robber is perhaps the genius of the Fell, and walks in the gloomy shades of night by the side of this little lake. This (he adds—it must have been a truly comforting thought to the other passengers) is all supposition.” The dreary place was one well calculated for raising gloomy ideas, tending to craze the imagination.

After this, it was a relief to reach Durham, a very picturesquely situated city with a grand cathedral and bishop’s palace. The pleasant banks on the west side of the river Wear were adorned with stately trees, mingled with shrubs of various kinds, which brought to one’s mind the romantic ideas of ancient story, when swains and nymphs sang their loves amongst trees by the side of some enchanted river. The abbey and the castle called to mind those enchanted places where knights-errant were confined for many years, until delivered by some friend who knew how to dissolve the chains and charm the necromancy.

Durham, he thought, would be a very fine place, were it not for the swarms of clergy in it, who devoured every extensive living without being of any real service to the public. The55 common people in Durham were very ignorant and great profaners of the Sabbath Day, and, indeed, over almost the whole of England the greatest ignorance and vice were under the noses of the bishops. He would not pretend to give a reason for this, but the fact was apparent.

Durham was a very healthful place—the soil dry, the air wholesome; but the Cathedral dignitaries performed worship rather as a grievous task than as a matter of choice, a thing not infrequently to be observed in our own days. The woman who showed the shrine of St. Cuthbert did not understand Mr. Murray when he referred to the Resurrection, a fact that gave him a good opportunity to enlarge upon the practically heathenish state of Durham’s ecclesiastical surroundings.

All this sightseeing, and these reflections and observations at Durham (and a good many more from which the reader shall be spared) were rendered possible by a lengthy halt made by the coach in that city. Thus there was ample time for seeing the cathedral—“very noble and delightful to the eyes of those who had a taste for antiquity or Gothic magnificence,” he says.

After they were wearied with sauntering in this old Gothic abbey, they went down to the river side. There the person who was fond of rural pleasures might riot at large. Comparisons drawn on the spot between the choristers of the grove, who sang from the heart, and the minor canons and prebendaries of the cathedral, who56 wearily performed their duties for a living, were, naturally, greatly to the disadvantage of the dignified clergy.

Strolling through the suburb of Old Elvet, the company at last returned to the inn—the “New Inn” it was called. The landlord of this hostelry was a jolly, honest man; his house spacious, and fit even to serve the Bishop. All things were cheap, good, and clean at this inn. If a person came in well pleased, he would find nothing to offend him, provided he did not create some offence to himself—which sounds just a little confused.

While our itinerant chronicler was noting down all these things, orders were given for departure, and so he had hurriedly to conclude.

And now, turning from wayside reflections, we get a description of the passengers. The coach, when it left Newcastle, was full. Four ladies, a gentleman of the sword and our humble servant made up its principal contents. They sat in silence for some time, until they were jolted into good humour by the motion of the vehicle, which opened their several social faculties. One of their female companions, who was a North Briton, a jolly, middle-aged matron with abundance of good sense and humour, entertained the company for a quarter of an hour with the history of her travels. She had made the tour of Europe, and had visited the most remarkable places in Christendom, in the quality of a dutiful wife, attending her valetudinary husband, travelling57 for the recovery of his health. Her easy, unaffected manner in telling a story made her exceedingly good company, and none had the least inclination to interrupt her until she was pleased to cease. She knew how to time her discourse, and never, like the generality of her sex, degenerated into tediousness and insipidity.

At every stage she was a conformist to all the measures of the company, and went into every social proposal that was made.

Another companion was a widow lady of Newcastle, quite as agreeable as the former. She understood how to make them laugh. Unfortunately, she only went one stage, and they then lost the pleasure of her company.

The third passenger was a Newcastle lady, well known in the literary world for her useful performances for the benefit of youth. This female triumvirate would have been much upon a par had they all been travellers, for their gifts of conversation were much alike; but the lady who had taken the tour of Europe possessed in that the advantage of circumstances.

The fourth lady was the Scottish lady’s servant. As she said nothing the whole way (remarks Mr. Murray), I shall say nothing of her.

The fifth person was an officer in the army, who appeared very drowsy in the morning, and came forth of his chamber with every appearance of reluctance. His hair was dishevelled and quite out of queue, and he seemed to be as ready for a sleep as if he had not been to58 bed. He was, for a time, as dumb as a Quaker when not moved by the spirit, and by continuing in silence, at last fell asleep until they had completed nearly half the first stage. During this time, Mr. Murray sarcastically observes, he said no ill.

They finished their first stage without exchanging many words with this son of Mars, except some of those flimsy compliments gentlemen of the sword pay frequently to the ladies. After a dish of warm tea the tissues of his tongue were loosed, and he began to let his companions know that he was an officer in the army, and a man of some consequence. He seemed to be very fond of war, and spoke in high terms upon the usefulness of a standing army. When he had exhausted his whole fund of military arguments in favour of slavery and oppression, Mr. Murray observed to him that a standing army had a bad appearance in a free country, and put it in the power of the Crown to enslave the nation—with the like arguments, continued for an unconscionable space.

It is not at all surprising that the soldier resented this. The spirit of Mars began to work within him, and he threatened that if he were near a Justice of the Peace he would have this argumentative person fined for hindering him from getting recruits, adding that he once had a man fined for persuading others not to enlist in his Majesty’s service.

To this Mr. Murray rejoined that the officer59 certainly had a right to say all the fine things he could to recommend the service of his master, but, having done that, he had no more to do; and that any man had also a right to tell his friends, whom he saw ready to be seduced into bondage, that they were born free, and ought to take care how they gave up their liberty—together with remarks derogatory of the justice of courts martial.

Our author did not, however, find this military hero a bloodthirsty man, for, by his own confession, he and a brother officer had a few months before surrendered their purses to a highwayman between London and Highgate for fear of bloodshed. This showed that some officers were abundantly peaceable in time of danger, and discovered no inclination for taking people’s lives. This gentleman of sword and pistol, in particular, had a great many solid reasons why men should not adventure their lives for a little money. He said there was no courage in fighting a highwayman, and no honour to be had in the victory over one; that soldiers should preserve their lives for the service of the country in case of war, and not run the risk of losing them by foolish adventure.

These reasons did not altogether satisfy the ladies, for one of them observed that robbers were at war alike with laws and governments, and that the King’s servants were hired to keep the peace and to defend the King’s subjects from violence; that officers in the army were as much obliged by their office and character to fight robbers as they60 were bound to fight the French, or any other enemy; and that footpads were invaders of the people’s rights and properties, and ought to be resisted by men whose profession it was to fight, and who were well paid for so doing. It was for money all the officers in the army served the King and fought his battles, and why should they not as well fight for money in a stage-coach as in a castle or a field? She insisted that only one of them could have been killed by the highwayman, or perhaps but wounded, and there were several chances that he might have missed them both. But, supposing the worst—that one had been shot—it was only the chance of war, and the other might have secured the robber, which would have been of more service to the country than the life of the officer. In short, she observed, it had the appearance more of cowardice than disregard for money, for two officers to surrender their purses to a single highwayman, who had nothing but one pistol.

The lady’s reflections were severely felt by the young swordsman, and produced a solemn silence in the coach for a quarter of an hour, during which time some fell asleep, and so continued until coming to the next inn, where the horses were changed. There two or three glasses of port restored the officer’s courage, and he determined, in case of an attack, to defend every one from the assaults of all highwaymen whatsoever. To show the courage that sometimes animated him, he told the story of how he had61 dealt with a starving mob in Dumfries. The hungry people of that town, not disposed to perish while food was abundant, and corn held by the farmers and corn-factors for higher prices, assembled to protest against such methods; and the magistrates, who thought the people had a right to starve, sent for the military to oblige them to famish discreetly or else be shot. Our hero had command of the party, where, according to his own testimony, he performed wonders. The poor people were shot like woodcocks, and those who could get away with safety were glad to return home to wrestle with hunger until Heaven should think fit to provide for them.

The officer was very liberal in abusing those whom he called “the mob,” and said they were ignorant, obstinate and wicked, and added that he thought it no crime to destroy hundreds of them.

The lady who had already given him a lecture then began to put him in mind of the footpad whom he and his brother officer had suffered to escape with their purses, and asked him how he would quell a number of highwaymen. Taken off his guard at the mention of footpads, he stared out of the window with a sort of wildness, as if one had been at the coach door.

Nothing was seen worthy of note until the coach came to Grantham, which place they reached about seven in the evening. The first things, remarks Mr. Murray—with all the air of a profound and interesting discovery—that travellers saw in approaching large towns62 were, generally speaking, the church steeples. Ordinarily higher than the rest of the buildings, they were—remarkable to relate—on that account the more conspicuous. The steeple of Grantham was pretty high, and saluted one’s eyes at a good distance before the town was approached. It seemed to be of the pyramidical kind.

Grantham was a pleasant place, although the houses were indifferently built. On reaching it, they wandered through the town before returning to the inn for supper, when the captain took care to say some civil things to the landlady’s sister, who was a very handsome young woman. It was, however, easy to perceive that she was acquainted with these civilities, and could distinguish between truth and falsehood. She made the captain keep his distance in such a manner as put an entire end to his compliments. The fineness of her person and the beauty of her complexion were joined with a modest severity that protected her from the rudeness and insults which gentlemen think themselves entitled to use towards a chambermaid, the character she acted in.

After supper was done, the coach-party were informed that some of Mr. Garrick’s servants were that night to exhibit in an old thatched house in a corner of the town. They had come abroad into the country during the summer vacation, to see if they could find anything to keep their grinders going until the opening of Drury Lane Theatre. They were that night to play the Went Indian and the Jubilee.

63 The whole of the passengers went to see the performance. The actors played their parts very indifferently, but, after all, not so badly but that one could, with some trouble, manage to perceive as much meaning in their actions as to be able to distinguish between an honest man and a rogue. Our ingenious and imaginative Mr. Murray thought it must be dangerous for an actor to play the rogue often, for fear of his performance becoming something more than an imitation. But after all, he says, with the fine intolerant scorn of the old-time dissenting minister, the generality of players had little morality to lose.

It was a very poor theatre—being, indeed, not a theatre at all, and little better than a barn. The audience, however, was good, and well dressed, and the ladies handsome. The performance was over by eleven o’clock, and the company dismissed. Mr. Murray concludes his account of the evening’s entertainment by very sourly observing that their time and that of the rest of the audience might have been better employed than in seeing a few stupid rogues endeavouring to imitate what some of them really were.

The coach left Grantham at two o’clock the next morning; much too early, considering the short rest the night’s gaiety had left them. But there was no choice—they were under authority, and had to obey. That person would be a fool who, having paid £3 8s. 6d. for a seat in a stage-coach64 from Newcastle to London, should consent to lose it by not rising betimes. The worst of it was, that here one had to take care of one’s self, because no one would wait upon him or return him his money. Observe the passengers, therefore, all, in the coach by 2 a.m. The company being seated, the driver went off as fast as if he would have driven them to Stamford in the twinkling of an eye. So early was the hour that we are not surprised to be told that the author fell asleep by the time they were clear of the town, and doubtless the others did the same. It may be remarked here that a very excellent proof of this being a fictitious journey is found in there being no mention of the passengers being turned out of the coach to walk up the steep Spitalgate Hill—a thing always necessary at that period of coaching history.

The remainder of this not-inaptly named Travels of the Imagination is made up chiefly of a long disquisition upon sleep—itself highly soporific—which only gives place to remarks upon the journey when the coach arrives on Highgate Hill. Coming over that eminence, they had a peep at London.

“It must be a wonderful holy place,” he suggests to the other passengers, “there are so many church steeples to be seen.”

The others, who must have known better, said nothing.

“Are we there?” he asked when they had reached Islington.

65 “No, not there yet.”

“Is it a large place: four times as large, for instance, as Newcastle?”

“Ten times as large.”

“Where are the town walls?”

“There are no walls.”

At last they reached Holborn, and the end of the journey, where the company dispersed and our chronicler went to bed.

66

We also will make a tour down the road. It shall not be, in the strictly accurate sense of the word, a “journey,” for we shall travel continuously by night as well as day—a thing quite unknown when that word was first brought into use, and unknown to coaching until about 1780, when coaches first began to go both day and night, instead of inning at sundown at some convenient hostelry on the road.