Title: Cycle Rides Round London

Author: Charles G. Harper

Release date: January 24, 2019 [eBook #58764]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Chris Jordan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

The Brighton Road: Old Times and New on a Classic Highway.

The Portsmouth Road: And its Tributaries, To-day and in Days of Old.

The Dover Road: Annals of an Ancient Turnpike.

The Bath Road: History, Fashion, and Frivolity on an old Highway.

The Exeter Road: The Story of the West of England Highway.

The Great North Road: The Old Mail Road to Scotland. Two Vols.

The Norwich Road: An East Anglian Highway.

The Holyhead Road: The Mail Coach Route to Dublin. Two Vols.

The Cambridge, Ely, and King’s Lynn Road.

[In the Press.

RIDDEN WRITTEN

& ILLUSTRATED BY

CHARLES G. HARPER

AUTHOR OF “THE BRIGHTON ROAD” “THE PORTSMOUTH ROAD” “THE DOVER ROAD” “THE BATH ROAD” “THE EXETER ROAD” “THE GREAT NORTH ROAD” “THE NORWICH ROAD” and “THE HOLYHEAD ROAD”

London: CHAPMAN & HALL LTD. 1902.

(All Rights Reserved)

When that sturdy pioneer, John Mayall junior, first rode his velocipede from London to Brighton in 1869, in much physical discomfort, and left his two would-be companions behind him in a crippled condition, no one could have foreseen the days when many thousands of Londoners would with little effort explore the Home Counties on Saturdays or week-ends, and ride sixty or seventy miles a day for the mere pleasure of seeking country lanes and historic spots.

There are, indeed, no more ardent lovers of the country, of scenery, of ancient halls and churches, of quiet hamlets and historic castles than London cyclists, who are often, in fact, recruited from the ranks of those pedestrians who, finding they could by means of the cycle extend their expeditions in search of the venerable and the beautiful, have cast away staff and stout walking-boots, and have learnt the nice art of balancing astride two wheels.

So much accomplished, the ex-pedestrian has at once widened his radius to at least thrice its former extent, and places that to him were little known, or merely unmeaning names, have become suddenly familiar. Even the sea—that far cry to the Londoner—is within reach of an easy summer day’s ride.

Few have anything like an adequate idea of how rich in beauty and interest is the country comprised roughly in a radius of from twenty to thirty miles from London. To treat those many miles thoroughly would require long study and many volumes, and these pages pretend to do nothing more than dip here and there into the inexhaustible resources, pictorial and literary, of the hinterland that lies without the uttermost suburbs.

To have visited Jordans, where the early Quakers worshipped and are laid to rest; to have entered beneath the roof of the “pretty cot” at Chalfont St. Giles that sheltered Milton; to have seen with one’s own eyes Penshurst, the home of the Sidneys, and Chenies, the resting-place of the Russells; to have meditated beneath the “yew tree’s shade” at Stoke Poges; to have seen or done all these things is to have done much to educate one’s self in the historic resources of the much-talked-of but little-known countryside. The King’s Stone in Kingston market-place, Cæsar’s Well on Keston Common, the “Town Hall” at Gatton, the Pilgrims Way under the lee of the North Downs, and the monumental brasses of the D’Abernons at Stoke D’Abernon have each and all their engrossing interest; or, if you think them to savour too greatly of the dry-as-dust studies of the antiquary, there remain for you the quaint old inns, the sleepy hamlets, and the tributary rivers of the Thames, all putting forth a never-failing charm when May has come, and with it the sunshine, the leaves and flowers, and the song of the birds.

CHARLES G. HARPER.

Petersham, Surrey, April 1902.

| PAGE | |

| Chenies and the Milton Country | 1 |

| Surbiton to Leatherhead | 22 |

| Ightham Mote and the Vale of Medway | 36 |

| The Darenth and the Crays | 53 |

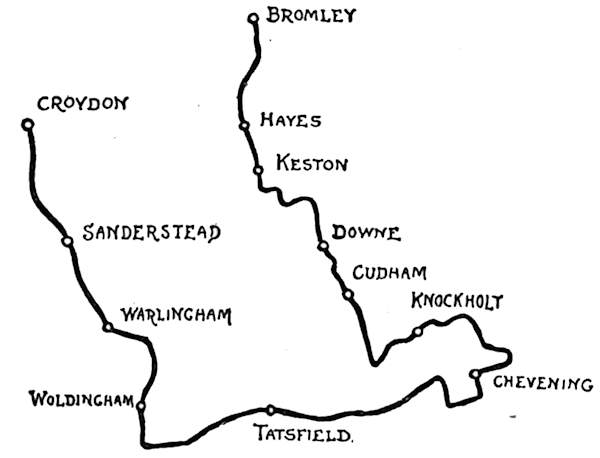

| Croydon to Knockholt Beeches and the Kentish Commons | 63 |

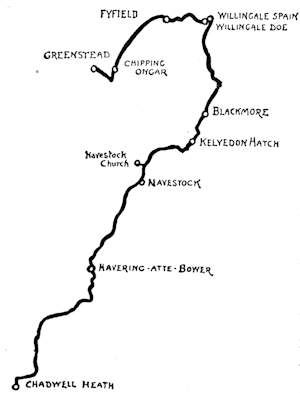

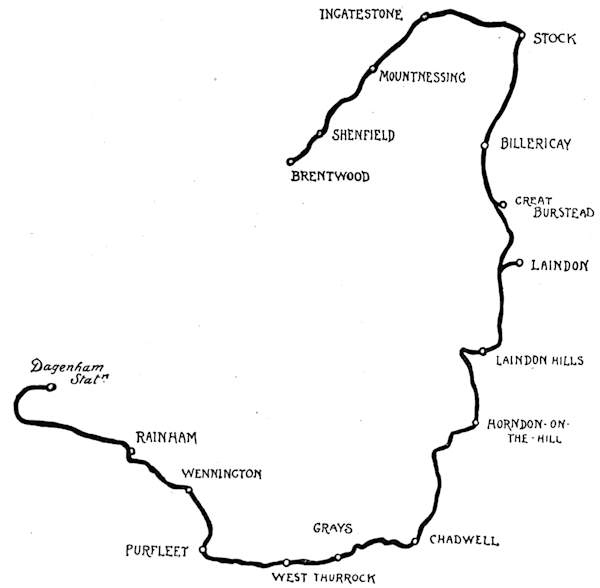

| In Old-World Essex | 75 |

| Among the Essex Hills | 86 |

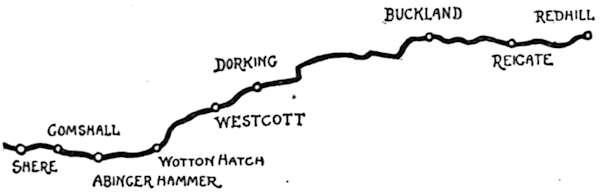

| Abinger, Leith Hill, and Dorking | 97 |

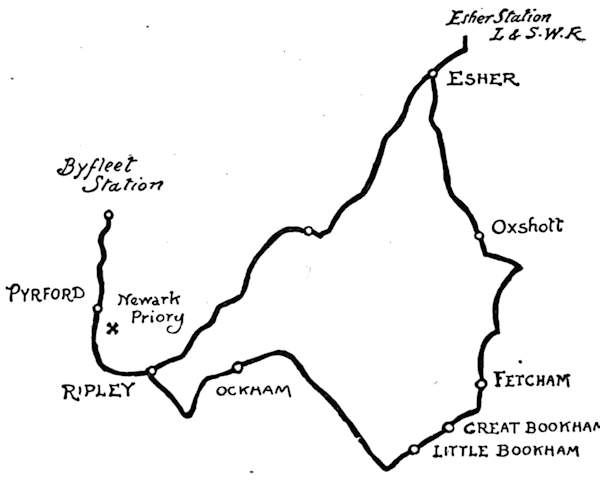

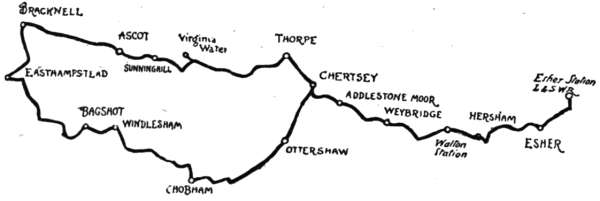

| Ripley and the Surrey Commons | 111 |

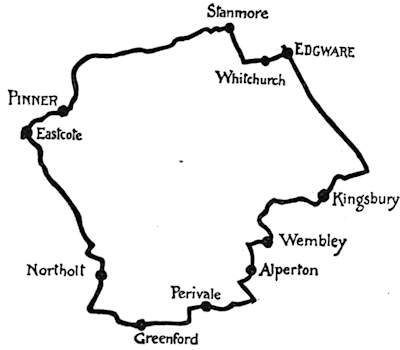

| Rural Middlesex | 121 |

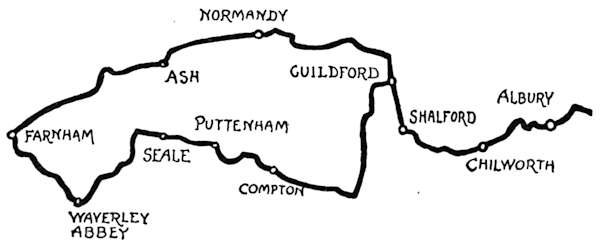

| Under the North Downs | 131 |

| The Suburban Thames | 155 |

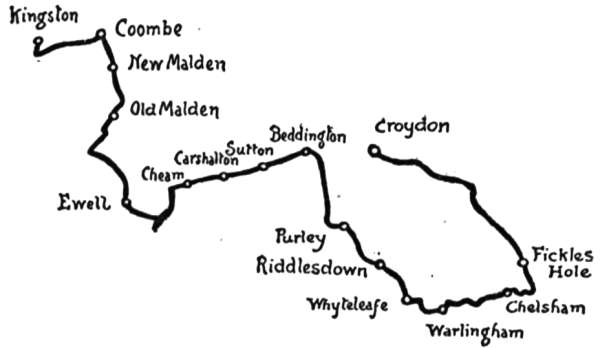

| The Southern Suburbs: Kingston to Ewell, Warlingham, and Croydon | 169 |

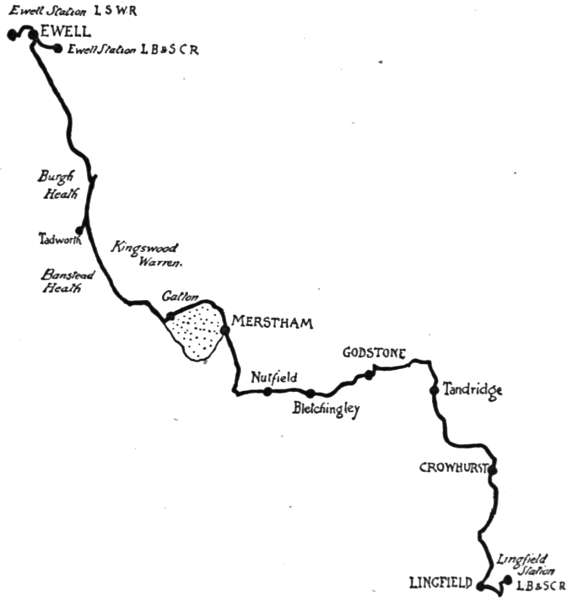

| Ewell to Merstham, Godstone, and Lingfield | 177 |

| Hever Castle, Penshurst, and Tonbridge | 186 |

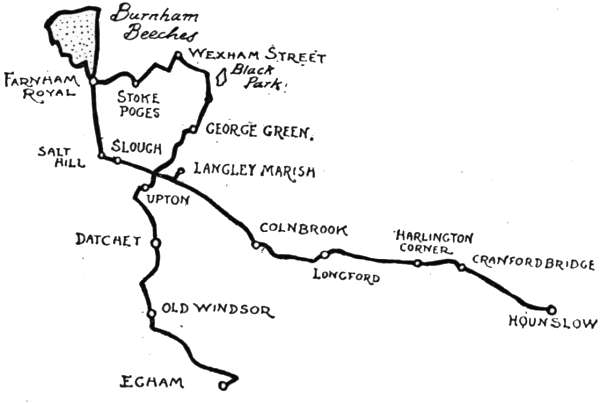

| To Stoke Poges and Burnham Beeches | 199 |

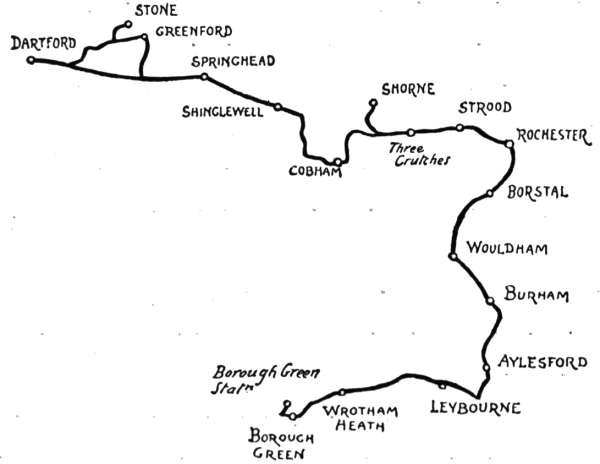

| Dartford to Rochester, Aylesford, and Borough Green | 218 |

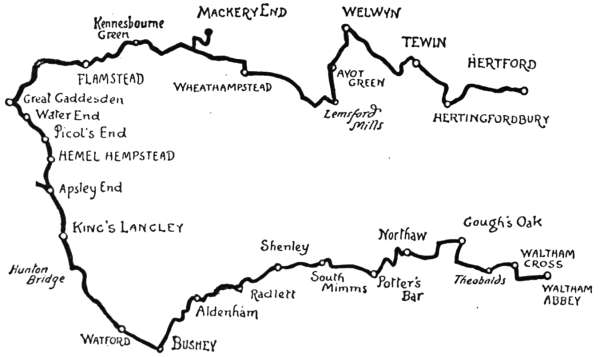

| Middlesex and Hertfordshire Byways | 231 |

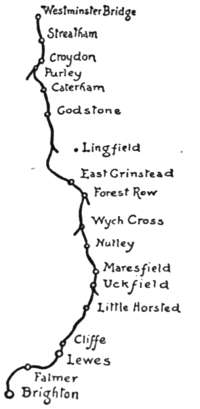

| The Back Way to Brighton | 251 |

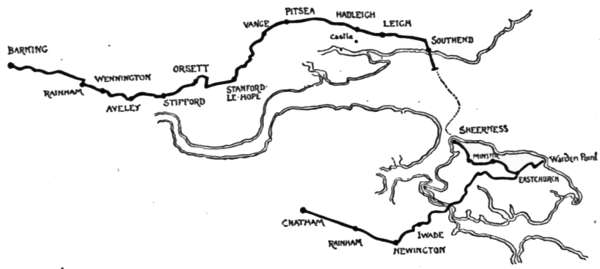

| Barking to Southend and Sheppey | 260 |

| PAGE | |

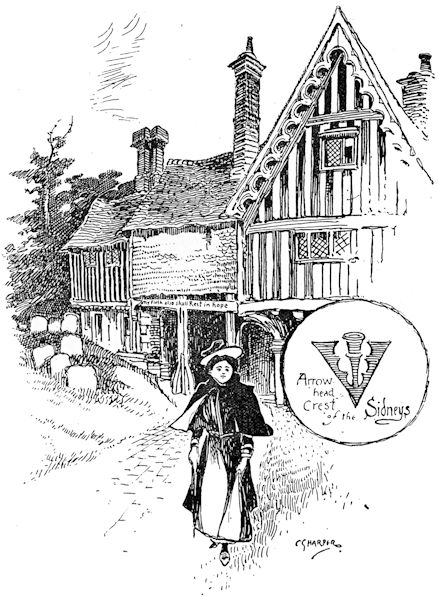

| The Old Lychgate, Penshurst | Frontispiece |

| Ruislip | 4 |

| Milton’s Cottage, Chalfont St. Giles | 13 |

| Jesus Hospital, Bray | 20 |

| Esher Old Church | 26 |

| Horseshoe Clump | 28 |

| Brass to Sir John D’Abernon | 30 |

| The Hall, Slyfield House | 31 |

| The “Running Horse” | 32 |

| Elynor Rummyng | 33 |

| Sign of the “Running Horse” | 35 |

| Crown Point | 38 |

| Sign of the “Sir Jeffrey Amherst” | 39 |

| Cromwell’s Skull | 40 |

| Ightham Mote | 43 |

| The Courtyard, Ightham Mote | 45 |

| The Dumb Borsholder | 50 |

| The Quintain, Offham | 51 |

| The Waterside, Erith | 54 |

| On the Thames, near Erith | 55 |

| Purfleet, from the Darenth Meadows | 57 |

| The Darenth | 58 |

| Eynesford | 60 |

| The Fool’s Cap Crest of Sir John Spielman | 62 |

| The Little Church of Woldingham | 66 |

| Knockholt Beeches | 71 |

| Cæsar’s Well | 73 |

| The Stocks, Havering-atte-Bower | 76 |

| Navestock Church | 79 |

| Blackmore Church | [xi] 81 |

| Two Churches in one Churchyard: the Sister Churches of Willingale Spain and Willingale Doe | 83 |

| Stock Church | 89 |

| Laindon Church | 91 |

| Parslowes | 96 |

| Ewell Old Church Tower | 98 |

| Evershed’s Rough | 103 |

| Leith Hill | 107 |

| Claremont | 113 |

| Newark Priory | 119 |

| The Little Church of Perivale | 123 |

| Pinner | 127 |

| A Mysterious Monument | 128 |

| Reigate Heath | 134 |

| Westcott | 136 |

| The Little Church of Wotton | 137 |

| Postford Ponds | 139 |

| An Old Weir on the Wey | 141 |

| The Guildhall and High Street, Guildford | 143 |

| Puttenham | 151 |

| The Seven-Dials Pillar, Weybridge | 157 |

| Pyrcroft House | 160 |

| The Ruins, Virginia Water | 164 |

| Carshalton | 173 |

| Leaving Carshalton | 175 |

| The “Town Hall,” Gatton | 180 |

| The Hollow Road, Nutfield | 181 |

| An Iron Tomb-Slab | 183 |

| The Ancient Yew, Crowhurst | 184 |

| The Gatehouse, Hever Castle | 189 |

| Hever Castle | 191 |

| Chiddingstone | 195 |

| Sunset on the Eden | 196 |

| A Crest of the Sidneys | 197 |

| Shoeing Forge, Penshurst | 198 |

| Gray’s Monument | 205 |

| The “Bicycle Window,” Stoke Poges | 208 |

| At Burnham Beeches | [xii] 211 |

| Stone | 219 |

| Early English Doorway, Stone Church | 220 |

| Interior, Stone Church | 221 |

| High Street, Rochester | 225 |

| Temple Bar | 233 |

| Gough’s Oak | 235 |

| Shenley Round-House | 236 |

| The Church Bell, Shenley | 237 |

| Water End | 242 |

| Flamstead | 245 |

| Mackery End | 247 |

| The North Downs and Marden Park | 253 |

| The “Sackville Lodging,” East Grinstead | 255 |

| Lewes | 258 |

| Barking | 263 |

| Eastbury House | 267 |

| Hadleigh Castle | 269 |

| Leigh Marshes and the Mouth of the Thames | 271 |

| Minster-in-Sheppey Church | 277 |

| Warden Point | 283 |

| Newington | 285 |

| The End | 288 |

| Sketch Maps to each Route. |

CYCLE RIDES

ROUND LONDON

Sight-seeing with ease and comfort is the ideal of the cycling tourist, and this run into a corner of Buckinghamshire and the Milton country comes as near the ideal as anything ever does in a world of punctures, leakages, hills, headwinds, and weather that is either sultry or soaking.

Starting from Southall Station, which will probably strike the tourist as in anything but a desirable locality, we gain that flattest of flat highways—the Oxford road—just here, and, leaving the canal and its cursing bargees, together with the margarine works, the huge gasometers, and other useful but unlovely outposts and necessaries of civilisation, speed along the excellent surface, past Hayes End and the hamlet Cockneys are pleased to call “’illingdon ’eath,” until within a mile and a half of Uxbridge, where a turning on the right hand will be noticed, properly furnished with a sign-post, pointing to Ickenham, Ruislip, and Pinner. Here we[2] leave the dusty high road and its scurrying gangs of clubmen, whose faces, as they scorch along, are indicative of anything but pleasure. It is a pleasant by-road upon whose quiet course we have now entered, going in a mile-long descending gradient, past the grand old trees of Hillingdon Court overhanging the way, down towards Ickenham. It is a perfectly safe and thoroughly delightful coast down here, far away from the crowds, along a lane whose leafy beauty and luxuriant hedgerows might almost belong to Devonshire, instead of being merely in Middlesex. At Ickenham, one of those singularly tiny and curiously old-world villages that are, paradoxically enough, to be found only in this most populous of English counties, are a village green, a pond, and a pump. The pond is, perhaps, not so translucent as it might be, for the reason that the ducks are generally busily stirring up the mud; and the green, being mostly loose gravel, is not so verdant as could be wished; but the pump, occupying a very central position, is at once ornate and useful, and, in appearance, something between a Chinese joss-house, a County Council band-stand, and a newspaper kiosk. Also, it still retains on its weathercock the tattered and blackened flag of some loyal celebration or another, which may mean loyalty in excelsis or merely local laziness. The very interesting old church, with whitewashed walls and with odd dormers in the roof, has some excellent windows and a little timbered spirelet that shows up white against a dense background of trees, and is, altogether, just such a place as Gray describes in his “Elegy,” in whose churchyard sleep the rude forefathers of the hamlet.[3] Suburbia has not yet disturbed this “home of ancient peace,” and it is still worth the very earnest attention of the artist, as also is that grand old Jacobean mansion of Swakeleys, standing in its park, near by.

A mile onward is Ruislip, best reached by bearing to the right at the next turning, and then sharply to the left. Round about “Riselip,” as its inhabitants call it, they grow hay, cabbages, potatoes, and other useful, if humble, vegetables; and, by dint of great patience and industry, manage to get them up to the London market. It is only at rare intervals that the villagers ever see a railway engine, for Ruislip is far remote from railways, and so the place and people keep their local character.[4] Two or three remarkably quaint inns face the central space round which the old and new cottages are grouped, and the very large church stands modestly behind, its battlemented tower peering over the tumbled roofs and gable-ends with a fine effect, an effect that would be still finer were it not that the miserably poor “restoration” work of the plastered angles, done by that dreadful person, Sir Gilbert Scott, is only too apparent.

Taking the Rickmansworth road, and presently crossing the road to Harefield, a desolate, half-ruined modern house of large size, apparently never yet occupied, is seen on the right. This is called St. Catherine’s End. Beyond it, on the same side, presently appears an unobtrusive road, with an air of leading to nowhere in particular, and, in fact, abruptly ending on the banks of Ruislip Reservoir. The sound of “reservoir” is not a pleasing one to those who are[5] familiar with the ugly things of that name with which an unbusiness-like Legislature has allowed the water companies to destroy the beauty of the suburban Thames; but there are reservoirs of sorts, and this is one of the picturesque kind. The Regent’s Canal Company made it, many years ago, as a store for refilling that waterway, and it was doubtless more than sufficiently ugly then. But trees have since that time partly covered the hillsides sloping down to it, and that finest of all artists and best of landscape gardeners, Nature, has grown rushes and water-lilies here, and nibbled a bit out of the straight-edged bank there, until the place looks anything but artificial. Wild birds and wild flowers, too, render this a pleasant spot, and there are boats even, in which one may voyage down the mile, or less, of lake, at whose distant end the red-roofed villas of Northwood may just be seen, whimsically like some foreign port.

Returning to the road, the first hill of the journey presents its unwelcome front to be climbed or walked. Duck’s Hill, as it is called, leads to an elevated tableland where the bracken and the blackberry briars grow, and shortly leads down again, by means of an exceedingly steep, though short, fall through a mass of loose stones and thick dust. The gradient and the quality of the road-surface render this bit particularly dangerous. Succeeding this is a more gradual descent, leading to a right and left road. The right-hand, on a down-grade, and one the tourist would fain follow, is not the route, which lies, instead, to the left, and goes determinedly uphill for half a mile. Just when you begin[6] to think this excursion is too much like taking a bicycle out for a walking tour, it becomes possible to mount and ride with comfort; and then, entering Batchworth Heath and Hertfordshire simultaneously, the lodge gates of Moor Park are seen across a wide-spreading green surrounded by scattered houses. It is of little use to describe Moor Park, for the house cannot be seen by the casual tourist, and the cyclist is not allowed in the grounds. The place has passed through many hands, and now belongs to Lord Ebury. It was once the property of a certain Benjamin Hoskins Styles, a forerunner of the modern type of financier, who had grown suddenly rich by speculating in South Sea shares. He caused the hills that faced the house in either direction to be cut through, in order to provide “vistas.” He secured his vistas at a cost of £130,000, which seems a high price to pay for them; but, according to Pope, he also let in the east wind upon his house, and the next owner, who happened to be Admiral Lord Anson, spent £80,000 in trying to keep it out again.

Gradual descents, and two or three sharper ones, lead for a mile in the direction of Rickmansworth, and then a C.T.C. danger-board shows its red warning face over a hedge-top, just as a beautiful distant view of the town unfolds itself below. There are those who, as a rule, disregard danger-boards: if such they be who wheel this way, let them be advised to make this an exception, for it is a long and winding drop down, and ends by making directly for a brick wall, some cottages, and a canal; sufficiently awkward things to encounter on a runaway machine. Those who will not be advised,[7] and are accordingly run away with, are recommended to choose the canal.

But the wise walk down, and, nearing the level, mount again, and wheeling over a switchback canal bridge and a river bridge, come happily into Rickmansworth.

This old town resembles Watford, Ware, and Hertford, but is much prettier. They are four sisters, these Hertfordshire towns, with a strong family likeness but minor differences. Ware is the slippered slut of them, without doubt, and Hertford (if local patriotism will forgive the comparison) the dowdy; Watford the more pretentious; while Rickmansworth is the belle. All are alike in their rivers and canals, their surrounding meads and woodlands, and their breweries.

Green pastures and still waters, hanging woods and old-world ways, render Rickmansworth delightful. One comes into it from Batchworth Heath downhill, and, across its level streets, climbs up again for Chenies, reached past Chorleywood and its common, and a succession of the loveliest parks. Chenies is a place of pilgrimage, for the church is the mausoleum of the Russells, Dukes of Bedford; and if one cannot, in fact, feel any enthusiasm for a family that has exhibited such powers of “getting on in the world,” and has consistently used those powers of self-aggrandisement, while professing Liberal opinions, at least the long and splendid series of their tombs is worth seeing.

The Rozels, as they were originally named, came over, like many other Norman filibusters, with the Conqueror. They did not, for a long while, make any[8] great mark after that event, and history passes them by until 1506. During all those centuries, the Russell genius for getting on lay fallow, and none of them did anything in particular. They just vegetated on their lands in Dorsetshire, at Kingston Russell, near Bridport, until that year, when a quite unexpected happening put the beginnings of promotion in their way. John Russell, heir of the uncultivated bucolic head of the house, had just returned from Continental travels, and had acquired polish and the command of the French, Spanish, and German tongues, accomplishments that would probably have been of no sort of use to him had it not been for the singular happening already hinted at. In the winter of 1506 the Archduke of Austria, voyaging from the Low Countries to Spain, was driven by the fury of the Channel gales into Weymouth. He was most unromantically sea-sick, and landed; although England was at that time no safe place for one of his house. But he preferred the prospect of political imprisonment to the unkindly usage of the seas. Meanwhile, until the king’s pleasure became known, he was sheltered by Sir Thomas Trenchard of Wolveton, near Dorchester; and because Sir Thomas knew no tongue but his own robust, native English, he had his young kinsman, John Russell, over from Kingston Russell, to act as interpreter and entertainer to the distinguished foreigner. Young Russell proved himself so courtly and tactful that when the Archduke visited Henry the Seventh on a friendly invitation to Windsor—where, instead of being clapped into a dungeon, he was royally entreated—he spoke in such high praise[9] of this young Englishman that the king speedily found him a position in the Royal Household. Thus was a career opened up to this most fortunate young man. He was with Henry the Eighth in France, and fought in several battles, losing an eye at the taking of Morlaix and at the same time gaining a knighthood. Diplomacy, which, rather than fighting, is the Russell métier, soon claimed him. Diplomacy, it has been well said, is the art of lying for the advantage of one’s country. Perhaps he had not learned the art sufficiently well, for his great mission to the Continent failed, and he returned, not in disgrace, but, with the inevitable Russell address and luck, to preferment. The times were fatal to honest men, and that Russell survived that troubled era and died in his bed in the reign of Mary, at peace, and ennobled by the title of Earl of Bedford, enriched with the spoils of confiscated religious houses and the lands of attainted and executed friends, is therefore no recommendation of his character, which was that of a cautious time-server and cunning sycophant. He lies here, the Founder of his house, his recumbent effigy beside that of his countess, who brought Cheneys into the family. It is a magnificent monument and the effigies evidently carefully executed likenesses, even down to the small detail of the earl’s eyelid, represented as drooping over the lost eye.

The second Earl of Bedford was a man of greater honour and sincerity than his father, the Founder. His monument and that of his countess stands beside his parents’ altar-tomb, and is of alabaster bedizened to extremity with painting and gilding. He was the[10] first Francis of the family. The last was the man (Francis, 9th Duke of Bedford) who poisoned himself in 1891.

Earl Francis, perhaps, derived his sincerity from his mother. Both were sincere Protestants, while his father was anything you pleased, so long as he could keep his head on his shoulders and put more money in his pocket. The son’s Protestantism was nearly the undoing of him, for the bloody Gardiner would probably have sent him to the stake had he not escaped to Geneva. When Elizabeth succeeded her sister, he returned and served his Queen well and truly, until his death in 1585. He was succeeded by his grandson, Edward, who in turn was followed by his cousin Francis; “the wise earl,” they call him, perhaps because he found, after being released from his imprisonment in the Tower for his political opinions, that it was more peaceful and profitable to busy himself about the draining of the ill-gotten Russell lands at Whittlesea and Thorney, than to contend with Parliament against the Crown. This is indeed wisdom, and worthy of a Russell and a lawyer; for as a lawyer he had been trained before his succession to the earldom had been thought of. His son William reproduced the shiftiness of the Founder, and lukewarmly sided first with King, then with Parliament, and so continually back and forth during the Civil War. They made him a duke before he died—they, that is to say, the advisers of William the Third—and the price paid for it was the blood of his eldest son. The title was given as a kind of solace for the loss[11] of that son, and must have been a bitter kind of plaister to salve grief. That son, William, had not the canny caution of his race, and deserves to be honoured for the self-neglecting enthusiasm for the Protestant religion which brought him to the block in 1683 for his alleged complicity in the Rye House Plot.

The most elaborate monument here at Chenies is that to his father and mother, but more truly to himself; for that fantastic pile of theatrical statuary, exhibiting the Duke and Countess contorted with paroxysms of grief, leads up, as the central point of this stony emotion, to the portrait head of this unhappy patriot who fell under the headsman’s axe.

There are other Russell monuments here, for the family has rarely been averse from post-mortem glorification; but to make a catalogue of them would be wearisome. Among the latest, and the most unassuming, is the plain slab to Earl Russell,—the Lord John Russell of earlier political struggles,—who died in 1878.

Chenies village, let it at once be said, is utterly disappointing, after one has heard so much of its beauties. “A model village,” no doubt, but how depressing these model villages are! And, indeed, the Russells rule “Chaineys” (as it should be pronounced) with an iron rule. The country in which it is set is beautiful, and at the centre of the village a group of noble trees, with a pretty spring and well-house, may be noticed; but that anyone can admire the would-be Tudor architecture of the cottages, almost all rebuilt by a Duke of Bedford about fifty years ago, is surprising. Yet there are those[12] who affect to do so. The village lies just off the road, to the right; and at its farther end stand the church and the manor-house, close to one another.

“Isenhampton Cheneys” is the real name of the place, but the Cheynes who once were paramount here are long since extinct, and the insistent “B” is now on every cottage, gate-post, and weathercock. The church, rebuilt, has the whole of its north aisle appropriated as the Bedford Chapel, so that, even here, you see how the Russells maintain the feudal idea. Froude, indeed, says the gorgeous monuments here are second only to the tombs of the Mendozas, the proudest race in Spain; but true though that be, he is grossly fulsome when he praises the Russells for their “Liberal” ideas. Truth to tell, the family has ever been content to wear the Liberal mask and yet to treat its unfortunate tenants in a manner that many an old Tory race would have neither the courage nor the wickedness to adopt. Ask of the Russell tenantry what they think, and, receiving your answer, the wonder arises how that family can keep up their curious pretence of being “friends of the people.”

Leaving Chenies, and regaining the highway to Amersham, we wheel along until, passing under the Metropolitan Railway at Chalfont Road Station, we take the second turning to the left, leading to Chalfont St. Giles. These three miles form the most exquisite part of the whole tour, from the purely rustic point of view; for they lead down through sweet-scented woodlands where the perfume of the pines and the heavy scent of the bracken (strongly resembling that of ripe strawberries) mingle with the refreshing odour of the[13] soil itself. Nothing breaks the stillness in the daytime save the hoarse “crock-crock” of the pheasants, and, when night comes, the feathered choir from the well-named neighbouring Nightingale Woods tunes up.

Chalfont St. Giles lies down in the valley of the Misbourne, across the high road which runs left and right, and past the Pheasant Inn. It is a place made famous by Milton’s residence here, when he fled London and the Great Plague. The cottage—the “pretty cot,” as he aptly calls it, taken for him by Thomas Ellwood, the Quaker—is still standing, and is the last house on the left-hand side of the long village street. The poet could only have known it to be a “pretty cot” by repute, for he was blind.

Americans, perhaps more than Englishmen, make this a place of pilgrimage; and serious offers were made, not so long since, to purchase the little gabled brick and half-timbered dwelling, and to transport it to the United States. Happily, all fears of such a fate are[14] now at an end; for the parish has purchased the freehold, and has made the cottage a museum, where the literary pilgrim can see the veritable low-browed room where Paradise Lost was written and Paradise Regained suggested, together with the actual writing-table the poet worked at. An interesting collection of early and later editions is to be seen, with Milton portraits, and cannon-balls found in the neighbourhood. No one will grudge the modest sixpence charged for admission by the parish authorities to all who are not parishioners.

The parish church still remains interesting, although three successive restoring architects have been let loose upon it; and there are some really exquisite modern stained-glass windows, as well as some very detestable ones. Their close companionship renders the good an excellent service, but has a very sorry effect on the bad. Notice the very beautiful carved-oak communion rails, which came from one of the side chapels of St. Paul’s Cathedral, given by Francis Hare, Bishop of Chichester and Dean of St. Paul’s. This spoiler of the metropolitan Cathedral is buried here, and a tablet records his dignities. Among other posts, he held that of Chaplain to the great Duke of Marlborough, whose courier, Timothy Lovett, by the way, who died in 1728, aged seventy years, lies in the churchyard, beneath the curious epitaph—

Timothy, it is evident, was not of the touring kind by choice.

Having seen these literary and other landmarks, we can either regain the road, and, passing through Chalfont St. Peter and its picturesque water-splash, where the Misbourne crosses the road by the church, come to the Oxford road, and by the turning to Denham through Uxbridge into Middlesex again; or else, braving a very steep, stony, and winding lane, make for Jordans, that lonely graveyard and meeting-house of the early Quakers, where lies William Penn, founder of the State of Pennsylvania, with many another of his sect. A left-hand fork in the road leads toilsomely in a mile and a half to the solitary shrouded dell where Jordans lies hid, embosomed amid trees. It was precisely for its solitude and comparative inaccessibility that Thomas Ellwood, the friend of Milton, with others of the Society of Friends, purchased Jordans in 1671. They bought it of one William Russell with the original intention of making it merely a burial-ground, but the building of the meeting-house soon followed.

This is the humble, domestic-looking, red brick building the pilgrim suddenly catches sight of when wheeling along the darkling lane. Hepworth Dixon, writing in 1851, says, “the meeting-house is like an old barn in appearance,” but that is scarcely correct. As a matter of fact, it greatly resembles a stable, and indeed is almost precisely identical in appearance with the still-existing range of stables facing Old Palace Green, Kensington; buildings erected at the same period as this.

The stern, austere character of the original Quakers—Cobbett calls them “unbaptized, buttonless blackguards”—is reflected in the look both of their burial-ground and their meeting-house. Nothing less like a place of worship could be imagined. Many in style—or in the lack of style—like it are to be seen in the New England States of the United States of America, to whose then desolate shores many of the early Quakers carried the creed that made them outcasts in their native land; and the American citizens who throng here in summer must often be struck with the complete likeness of the scene to many Pennsylvanian Quaker places of meeting.

The plot where Penn and many others lie is just an enclosed field, and not until recent years were any memorials placed over some of their resting-places. A dozen small headstones now mark the grave of William Penn, the Founder of the State, and others of his family.

Twice a year is Jordans the scene of Quaker worship, on the fourth Sunday in May and the first Thursday in June, when many of the faith come from long distances to commemorative services.

Leaving Jordans, and striking the road into Beaconsfield, we reach that quietly cheerful town in another two miles, coming into it past Wilton Park, on the Oxford road. The little town that gave Benjamin Disraeli his title is a singularly unpretending place, and is less a town than a very large village. Passing through its yellow, gravelly street, and turning to the left, when a mile and a half out, down the Oxford road, at the[17] hamlet of Holtspur, the way to Wooburn Green and Bourne End lies downhill, along the valley of that little-known tributary of the Thames, the Wye, which, some miles higher up, gives a name to High Wycombe. Bourne End has of late years grown out of all knowledge, being now a place greatly favoured by those outer suburbanites who more especially affect the Thames; so that new villas plentifully dot the meads and the uplands towards Hedsor Woods and Clieveden.

And so across the Thames into Cookham and Berkshire. Frederick Walker discovered Cookham, and painted the common and the geese cackling across it, long before Society had found the Thames. He died untimely, and is buried in the old church close by; and since then Cookham has become more sophisticated—pretty, of course, and equally, of course, delightful, but not the Cookham of the seventies. But if, on the other hand, you did not know the village then, and make its acquaintance only now, you will have no regrets, and will enjoy it the more. There is an odd effort at poetry on a stone in the churchyard, which, perhaps, should not be missed. It tells of the sudden end of William Henry Pullen in 1813, and among other choice lines says—

Three parts of the road from Cookham to Maidenhead are exceedingly dull and uninteresting; let us therefore[18] take the towing-path, and cycle along that, ignoring, like everyone else, the absurd prohibition launched a few seasons ago by the Thames Conservancy. Not hurrying—that would be foolishness; for although the river is well-nigh spoiled by Boulter’s Lock, it is still lovely all the way to Cookham, with the most glorious views of Clieveden Woods, rising, tier over tier, on the opposite shore. Here too, of course, have been changes since first Society, and then the Stage, discovered the river a few years ago, and bungalows are built on the meadows; but we must needs be thankful that they were built in these latter days, now that the hideous villas of forty years since are quite impossible.

Nearing Maidenhead, and coming to the Bath road, running right and left, we turn to the right and then down the first road to the left (Oldfield road), then the next two turnings in the same direction, when the old tower of Bray Church comes in sight; that Bray celebrated for its vicar immortalised in the well-known song, who, when reproached with being a religious trimmer and inconstant to his principles, replied, “Not so; for I always keep my principle, which is to live and die the Vicar of Bray.” Simon Alleyn was the name of this worthy, who lived, and was vicar, in the reigns of Henry VIII., Edward VI., Mary, and Elizabeth.

First a Papist, he kept his place by becoming a Protestant, recanting when Mary came to the throne, and again becoming a Protestant under Elizabeth. Called apostate, renegade, turncoat, and denier of Christ, modern times would give him the kindlier name of “opportunist.” At anyrate, his opportunism was successful, for he held office[19] from 1540 to 1588. The ballad originated in 1712, in a song entitled “The Religious Turncoat; or, the Trimming Parson,” which refers to no particular place or person, and has no fewer than eighteen verses, quite distinct from the modern ballad. Thus they run, for example:—

These verses, it will be noticed, place the trimming story a hundred years later.

The churchyard is entered by a lich-gate with a curious old house over it. In the church itself is a monument to William Goddard, the seventeenth-century founder of Jesus Hospital, and Joyce, his wife. That celebrated old almshouse stands on the road as we leave Bray for Windsor. It is a quaintly gabled, red brick building, with a statue of the founder in an alcove over the entrance. A central courtyard has little dwellings ranged round it, and a rather striking chapel, familiar in Frederick Walker’s famous picture, the “Harbour of Refuge,” painted here in 1871-72. Unfortunately, those who are familiar with that beautiful picture (now in the[20] National Gallery) will be disappointed on seeing the real place, for the painter has quite idealised Jesus Hospital, and has imagined many details that have no existence.

Beyond the hospital, a turning to the left leads to Windsor, past Clewer. Windsor bulks hugely from these levels, with huddled houses and the towering mass of the castle lining a ridge above the Thames; the Round Tower, grim and terrible in other days, merely, in these times, a picturesque adjunct to the landscape.

It seems, indeed, that everywhere in these days the iron gauntlet has given place to the kid glove; persuasion is, nowadays, more a mental than a physical process. Only at Windsor these things take higher ground; here for persuasion in this era read diplomacy,[21] where it had used to be a blood-boltered performance, in whose dramatic course axe and chaplain took prominent parts. The castle survives, its mediæval defences restored for appearance sake, but its State Apartments filled with polite furniture, dreadfully gilded and tawdry. It makes a picture, this historic warren of kings and princes; but alas for picturesqueness, Henry the Eighth’s massive gateway is guarded to-day—not by an appropriate Yeoman of the Guard, but by a constable of that singularly unromantic body—the police!

If one is wise, one does not visit Windsor for the sake of the State Apartments, but for the external view of the castle, set grandly, like a jewel, amid its verdant meads. The meads form the most appropriate foreground; the proper time, either early morning or evening, for then, when the mists cling about the river, and the grass is damp with them, that ancient palace and stronghold, that court and tomb of Royalty, bulks larger than at any other hour, both on sight and mind. And, having thus seen Windsor aright, you cannot but return well pleased.

Surbiton, that great modern suburb of Kingston, can conveniently be made the starting-point of many pleasant runs through Surrey. Let us on this occasion start from Surbiton Station, and, making for the high road that runs to Ripley, turn to the left at Long Ditton, where the waterworks are, and so in a mile to the first semblance of rusticity at that well-known inn, the “Angel at Ditton,” as it is generally called by the many cyclists to whom for years this has been a rallying-place; although this is not Ditton at all, and its real name the not very romantically-sounding one of “Gigg’s Hill Green.” We pass the “Angel” on the left; on the right hand stretches the pleasant Green, with roads running away in the same direction to the village of Thames Ditton, a mile away, and worth seeing for those who have the exploring faculty well developed.

But to continue straight ahead, we pass Gigg’s Hill Green only to come to other and larger commons—Ditton Marsh and Littleworth Common respectively—along a road straight and flat for a considerable distance, passing under the long tunnel-like archway of the London and South-Western main line, and emerging from it to a full view of beautiful Esher Hill, a mile and a half away, while away on the left stretch miles of open country.[23] Notice outside a modern, dry, and dusty-looking inn, called the “Orleans Arms,” a tall, circular stone pillar about ten feet in height, with names of towns along the road, and the distances to them, carved on it. This is familiarly known as the “White Lady,” and dates back to the coaching age; for this was the old road to Portsmouth, and was once crowded with traffic.

From this point it is a mile of continuous, though gentle, rise to Esher village—Sandown Park racecourse on the right, under the hill. Notice the very highly ornamental iron gates and railings of the park: a romantic history belongs to them. They came from Baron Grant’s palatial mansion of Kensington House, built but never occupied, and then demolished, which stood in Kensington Gore.

Kensington House is now quite forgot, and on its site rise the stately houses of Kensington Court. It was in 1873 that Baron Grant, bloated with the money of the widow and the orphan, plundered from them in his Emma Mine and other rascally schemes, purchased the dirty slum at Kensington then known as the “Rookery,” and set about building a lordly pleasure-house on its site. Just as it was finished, his career of predatory finance was checked, and he never occupied the vast building. For years it remained tenantless, and was then demolished. “Grant,” as he called himself, died obscurely in 1899. He had in his time been the cause of the public losing over £20,000,000 sterling. The Daily News spoke of him as an Irishman, but it will readily be conceded that his real name of Gottheimer is not strikingly Hibernian. He was, it is true, born in[24] Dublin. So was Dean Swift: but, as the Dean himself remarked, to be born in a stable does not prove one to be a horse.

Although “Grant” died obscurely, and his name and his schemes had long before that time become discredited, it must not be supposed that he was personally ruined with the wreck of his projects. Not at all. He lived and died very comfortably circumstanced, while many of his creditors remained unsatisfied. He could pay debts when he chose, but when he chose not to, there were no means of compelling him. Where have we heard the same story in recent years?

Esher, up along the hill, is a pretty village, with many and varied associations and an extraordinary number of curious relics. It is a charmingly rural place, with a humble old church behind an old coaching inn, and a new church, not at all humble, across the way. The old church and the old inn—the “Bear,” they call it—are both extremely interesting. In the hall of the inn, placed within a glass case, secure from the touch of the vulgar, are the huge boots worn by the post-boy who drove Louis Philippe, the fugitive King of the French, to Claremont in 1848. They are huge jack-boots closely resembling the type worn by Marlborough and his troopers at Blenheim, Ramilies, and Malplaquet.

“Mr. Smith”—for under that plebeian disguise the Citizen King fled from Paris—resided at Claremont by favour of Queen Victoria, and died there two years later.

Claremont is an ominous place, with a tragical cast to its story. Most of those connected with it have been unfortunate, if not before they sought the shelter of its ill-omened roof, certainly afterwards. Clive, the “heaven-born general,” who built it, shot himself; the newly married only child of George the Fourth—the ill-fated Princess Charlotte—died there, under somewhat mysterious circumstances; and the Duke of Albany, who had not long been in residence, died untimely in the south of France, in 1884.

The old church of Esher, long since disused and kept locked and given over to spiders and dust, has a Royal Pew, built for the use of the Princess Charlotte and the Claremont household in 1816. It is a huge structure, in comparison with the size of the little church, and designed in the worst possible classic taste; wearing, indeed, more the appearance of an opera-box than anything else.

The authorities (whoever they may be) charge a shilling for viewing this derelict church. It is distinctly not worth the money, because the architecture is contemptible, and all the interesting monuments have been removed to the modern building, on a quite different site, across the road.

It cannot be too strongly insisted upon that the death of the Princess Charlotte in her eighteenth year made a vast difference in English history—or, at least, English Court history. Had she survived, there would[26] have been no William the Fourth, and Queen Victoria would never have been queen. Think of it! No Victorian Era, no Victoria Station, no Victoria Embankment, no Victoria in Australia, no Victoria in Vancouver Island; and, in short, none of those thousand things and places “Victoria” and “Victorian” we are surrounded with. None of those, and certainly no Albert Halls, memorials, streets, and places commemorative of that paragon of men.

The reflections conjured up by an inspection of Esher old church are sad indeed, and the details of it not a little horrible to a sensitive person. There is an early nineteenth-century bone-house or above-ground vault attached to the little building, in which have been stored coffins innumerable. The coffins are gone, but[27] many of the bony relics of poor humanity may be seen in the dusty semi-obscurity of an open archway, lying strewn among rakes and shovels. To these, when the present writer was inspecting the place, entered a fox-terrier, emerging presently with the thigh-bone of some rude forefather of the hamlet in his mouth. “Drop it!” said the churchwarden, fetching the dog a blow with his walking-stick. The dog “dropped it” accordingly, and went off, and the churchwarden kicked the bone away. I made some comment, I know not what, and the churchwarden volunteered the information that the village urchins had been used to play with these poor relics. “They’re nearly all gone now,” said he. “They used to break the windows with ’em.” And then we changed the subject for a better.

The “new” church—new in 1852—is a very imposing one, also with its Claremont Royal Pew, very like a drawing-room, built on one side of the chancel, high above the heads of the vulgar herd, who often, when the church is open, climb up the staircase to it, and, seating themselves on the chairs, go away and boast of having sat on the seats honoured by the great—thereby proving the vulgarity aforesaid.

The church was built chiefly from the accumulated funds of a bequest anciently left to Esher. This was the piece of land now called Sandown Park and the site of the well-known racecourse, let to the racecourse company at an annual rent. Not until 1899 did it occur to the Vestry that for the Church to be the landlord of a racecourse was a rather scandalous state of affairs, and the sanction of the Charity Commissioners was[28] then sought and obtained for a scheme to sell the land outright for £12,000, this sum to be invested in Consols. These tender consciences obscured the business side of the question, for the land, if not already worth more than that sum, very shortly will be, considering the spread of London’s suburbs. It is rather singular that this freehold, bequeathed so long ago, was once the site of the forgotten Priory of Sandown, which would appear never to have been revived after its Prior and all the brethren perished in the great pestilence, the Black Death, that almost depopulated England in the Middle Ages.

Leaving the village behind and pursuing the Portsmouth road, the woodlands of Claremont Park are left behind as we come downhill towards Horseshoe Clump, a well-known landmark on this road. This prominent object is a semicircular grove of firs on[29] the summit of a sandy knoll, looking over the valley of the Mole, the “sullen Mole” of the poets, flowing in far-flung loops below, on its way to join the Thames at Molesey. This is a switchback road for cyclists thus far, for the ridge on which Horseshoe Clump stands is no sooner gained than we go downhill again, and so up once more and across the level “fair mile,” to descend finally into Cobham Street, where the Mole is reached again. Here turn to the left, along a road marked by a sign-post “Church Cobham,” the original village, off the main road, of which Cobham Street on the Portsmouth road is only an offshoot developed by the traffic of old road-faring days. Church Cobham has, besides its ancient church and “Church Stile House,” a picturesque water-mill and mill-pond beside the road. Beyond, in two miles, the tiny village owning the odd name of Stoke D’Abernon is sighted; village in name only, for the church and a scattered house or two alone mark its existence. The Norman family of D’Abernon gave their name to this particular Stoke, originally a primitive British stockade, or defensible camp, at a ford on the Mole.

For the happily increasing class of tourists who are interested in archæology, let it be noted here that the chancel of this church contains the earliest monumental brass in the kingdom, the mail-clad effigy of Sir John D’Abernon, dated 1277.

Many of his race, before and after his time, lie here. The life-sized engraved figure of this Sir John, besides being the earliest, is also one of the most beautiful. Clad from head to foot in a complete suit of chain mail,[30] his hands clasped in prayer, heraldic shield on one arm, his pennoned lance under the other, and his great two-handed sword hanging from a broad belt outside the surcoat, this is a majestic figure. His feet rest on a writhing lion, playfully represented by the engraver of the brass as biting the lance-shaft.

A second Sir John D’Abernon, who died in 1327, son of the first, also has his life-sized memorial engraved on brass.

Stoke “Dabbernun,” as the rustics call it, is at once exhausted of interest when its church has been seen.

The road now crosses the Mole by an old red brick bridge, and leads up a gentle rise to Slyfield Farm, a very picturesque old farmstead of red brick, designed in the classic style prevailing in the reign of James the First. This was once the manor-house of the now extinct Slyfield family. Fair speech and presentation of a visiting-card may generally be relied upon to secure the courtesy of a glimpse into the hall of this interesting old house, where an ancient massive carved-oak staircase may be seen, still guarded by the original “dog-gates”[31] that in the times of our forebears kept the hounds in their proper place below stairs.

The road now winds pleasantly through the valley, but not within sight of the river until past the outlying houses of the little village of Fetcham. On gaining the point where the road from Great Bookham to Leatherhead falls into the one we are following, look out for an unassuming left-hand turning past the railway arch, leading in a hundred yards to Fetcham mill-pond. This is a lovely spot, where the wild-fowl congregate, and well worth halting at on a summer’s day, but tucked away so artfully that it will scarce be found save by asking. It is a long sheet of water, with reeds, and an island in the middle, and a peep back towards Leatherhead from the farther end, where the church tower peers above the trees. Flocks of moor-hens, a few couples of stately swans, and some domestic ducks form[32] the invariable feathered company of the pond, and not infrequently the coot takes up his quarters here, with myriads of dabchicks; the great swans and little dabchicks, swimming together on the water, forming the oddest of contrasts: the swans like warships and the dabchicks like little black torpedo-boats.

Cycles can be walked along the path to the far end of the pond, where the road is reached again.

Leatherhead itself lies off to the left, less than half a mile distant, reached by a many-arched bridge straddling athwart the Mole, here a divergent and sedgy stream broken up by osier aits. On the other side of the bridge stands that crazy old inn, the “Running Horse,” claiming a continued existence since the fifteenth century and[33] to have been the scene of the celebrated “tunning of Elynor Rummyng”; but, like the silk stocking so long and so often darned with worsted that no trace of the original material remained, the “Running Horse” has in all these six centuries been so repaired here and patched there that he would be a bold man who should dare swear to a fragment of that old house remaining.

Elynor Rummyng was a landlady who flourished in the time of Henry the Seventh. Skelton, poet-laureate of that day, in a long rambling set of rhymes, neither very elegant nor very decent, describes her and her customers at great length. As for Elynor herself, he says she was so ugly that

with much else in the uncomplimentary kind.

She was, Skelton goes on to say, “sib to the devil”; she scraped up all manner of filth into her mash-tub, mixed it together with her “mangy fists,” and sold this hell-broth as ale—

There is no accounting for tastes, and, reading Skelton, it would seem as though the whole district crowded to taste the unlovely Elynor’s unwholesome brew, bringing with them all manner of goods—

and then, doubtless, there was trouble in the happy home.

Why the crowd resorted thus to tipple the horrible compound does not appear: one would rather drink the usual glucose and dilute sulphuric acid of modern times. The pictorial sign of the old house still proudly declares—

To do that, you would think, it must needs have been both good and cheap. Certainly, if the portrait-sign of Elynor be anything like her, customers did not resort to the “Running Horse” to bask in her smiles, for she is represented as a very plain, not to say ugly, old lady with a predatory nose plentifully studded with warts.

Leatherhead is a still unspoiled little town, beside its “mousling Mole,” as Drayton calls that river. “Mousling,” probably because of the holes, or “swallows,” as they are called, into which this curious river every now and again disappears, like a mouse, as the poet prettily expresses it.

From Sevenoaks, on the South-Eastern Railway, let this tour be begun; from that Sevenoaks Station rejoicing in the eminently cricketing name of “Bat and Ball.” There are reasons sufficiently weighty why the starting-point should not be fixed nearer London, chief among them being the hilly nature of the way. Sevenoaks itself, quite apart from the rather uninteresting character of its long street, does not bulk largely in the affections of the outward-bound wheelman, for to reach it one has a more than mile-long climb. But, setting our faces eastward, and avoiding Sevenoaks town, an easier beginning presents itself along the road to Seal, where, leaving behind the trim gardens and modern villas that form a kind of suburban and secular halo around the railway, we plunge into a woodland district.

Seal village is a harbinger of the Thoreau-like solitudes that succeed along the road to Ightham, standing as it does at the gates of Seal Chart, where, away from the road on either hand, stretch such crepuscular alleys of murmuring pines that even Bournemouth itself never knew. Does there exist a cyclist who can hurry along this road and not linger here, to rest his trusty steed[37] against the corrugated stem of one of these aromatic giants of the forest, and listen to the intoning of the wood pigeons in the cathedral-like half-lights? If such there be, surely he merits the Tennysonian description, “a clod of thankless earth.” The far-spreading woods are unfenced and quite open to the road for one to wander in at will, and never a sound in their solitudes but belongs to the woodlands themselves; the cooing of the pigeons, and the rustling of some “sma’ wee beastie” disturbed by the crackling of the dry twigs under your feet. The squirrels themselves are noiseless and, to the unpractised eye, invisible; but there are many of them overhead, running with lightning speed along the red-brown branches of the pines that so accurately match the rust-red hue of their fur, and so help to conceal them from casual observation.

Following the road and the woods for two miles, the highway dips sharply, and takes a left curve just where you glimpse the blue smoke rising from the rustic chimneys of a wayside inn, down on whose lichened roof you look in descending. To dismount here, just as the view begins to disclose itself, is the better way, for only thus will you be in full receipt of the beauty and the exquisite stillness of the scene. The woods recede, like some clearing in a Canadian forest, and, standing back from the road, you see the inn whose roof-tree was first disclosed. On the other side of the highway, swinging romantically from the branches of a great Scotch fir, is the picture-sign of the house, bearing the legend, “Sir Jeffrey Amherst, Crown Point,” and[38] showing the half-length portrait of a very determined-looking warrior, clad in armour and apparently deep in thought; while in the background is a broad river, across whose swift current boat-loads of soldiers, in the costume of two centuries ago, are being rowed.

The scene—the old inn, with the smoke curling peacefully upwards against the blue-black background of the pine-woods, and the picturesque sign swinging with every breeze—is a realisation of the places pictured in the glowing pages of romantic novelists. If one were only a few years younger, and conventions had not come to curb one’s first impulses, there would be no more suitable spot than this where to become an[39] amateur Red Indian, or one of the robber chiefs suitable for such a spot.

The place has rather a curious story. “Crown Point,” as it is generally called, is so named after a place in Canada where Sir Jeffrey Amherst gained a great victory over the North American Indians early in the eighteenth century. Amherst eventually became Field-Marshal and Commander-in-Chief to the Forces, and, retiring and settling in Kent, founded the family of whom the present Earl Amherst is the head. The scenery here is said to greatly resemble that of Crown Point in Canada. The sign of the inn is repainted and kept in repair by Earl Amherst.

It may be worth noting that an historical relic is[40] preserved in the immediate neighbourhood of this place; no less important an one, indeed, than the skull of Oliver Cromwell, now in the possession of Mr. Horace Wilkinson. Much discussion has arisen respecting it, but there seems no room for doubting that this is the veritable skull (or, rather, mummified head) of the Protector. The relic has a pedigree that traces it back to the stormy night when it was blown off the roof of Westminster Hall, where it had been exposed on a spike after the Restoration. The rusty spike still transfixes it, and on the dried cranium the reddish brown hair is yet to be seen. It has had many odd adventures. Picked up by a sentry on duty at[41] Westminster Hall, it was concealed under his cloak, and afterwards secretly disposed of to some of Cromwell’s descendants, coming, many years later, into the possession of a travelling showman, from whom it was purchased by a relative of the present owner.

Ightham village, to which we now make our way, must by no means be confounded with Ightham Mote, two miles distant from it southward, past the hamlet of Ivy Hatch. Steeply up, and as steeply down, with intervals of welcome flatness, goes the road to the village, always through the pine-woods, and here and there the way is overhung with little craggy cliffs of yellow sand and gravel, as yet untouched by the road-surveyors of the County Council, who will doubtless some day trim away all these rustic selvedges of the forest, and curb and bank them in a straight line. What will the artists do then? Meanwhile, one still has here just one of those characteristic scenes Morland and his school so loved to paint—the hollow road with its steep banks, in whose crumbling earth the great wayside trees have secured what looks like a precarious footing, and the sandy earth where the moles and the rabbits burrow deep amid the gnarled roots. Up on the hillside that looks down upon the road is Oldbury,[42] a Roman encampment, called by antiquaries the “Gibraltar of Kent”; but we will take the tales of its strength on trust, for a bicycle is no aid in exploring hilltop fortifications.

Ightham is a village that looks as though it had at some time aspired to become a town, so urban in character are some of its houses; urban, that is to say, in no ill sense. There is, for instance, the so-called “Town House,” one of the most beautiful and dignified architectural compositions of that late seventeenth or early eighteenth century character which in its Renaissance ideals makes so thorough a departure from the older English Gothic models. By “Town House” you are to understand a building devoted to public purposes; what we should, nowadays, more grandiloquently term a “Town Hall.” There was a time when Ightham bade fair to take on a new era of importance, in the early days of cycling, when it enjoyed a great popularity that was stolen away by Ripley, nowadays itself in the cold shade of neglect.

Turning to the right out of Ightham, through the pretty hamlet of Ivy Hatch, the Mote House is reached in two miles of shady lanes. Like many another old English house, Ightham Mote is tucked away coyly from the sight of the casual wayfarer. Looking diligently, you see it on the left hand, on coming down into a hollow, just a glimpse of its magpie black and white north front glimmering through the surrounding woods. It is one of the earliest of the fortified manor-houses, something between a castle and a residence, built when people had greater ideas of [45]comfort than obtained when the Edwardian strongholds were erected, and yet before it was safe to build a house incapable of defence. Nowadays one finds a preference for an open, breezy situation; in those times, if they did not build upon sites difficult of access in one way they did in another; if they did not select a rocky crag they sought some oozy hollow, where, with some little ingenuity, it was possible to form a broad moat by damming the surrounding streams. This was the resort adopted here, and in Ightham Mote to-day one sees the original idea of a watery girdle, from whose inner sides rise defensible walls enclosing a courtyard. The only way across this moat was by a drawbridge, now replaced by masonry, the drawbridge defended by the still-remaining entrance-tower. Originally the ornamental[46] part of the residence was strictly kept within the courtyard. The walls looking outward were either blank or else very sparingly provided with window openings. Later centuries have somewhat altered this, and the picturesque, half-timbered gables and outbuildings tell a tale of increasing security. There are those who will have it that Ightham Mote is the most picturesque old house in England. Perhaps it is, for its moss-grown stone walls, going sheer down into the clear water of the moat, its nodding, peaked gables, reflected in that beautiful ceinture, and the mellow red of the old brick entrance-tower, form a wonderful picture. Five hundred years have passed, and it is still a home. The tapestried hall, with its boldly timbered roof, yet forms the central point of the house, and the bedrooms where the Selbys, the old-time owners, slept for many generations are in use in these latter times. Modernity has crept in with regard to the essentials of comfortable living, but nowhere does it appear to mar the perfect old-world beauty of the place.

The imaginative may yet, without much difficulty in the mental exercise, people the quaint paved courtyard with the conventionally fair ladies and gentle knights of the age of chivalry; those ladies who, to judge by the works of the Old Masters, were so extremely plain, and those knights who could teach the tiger and the hyæna something in ferocity. Not that the old owners of Ightham Mote were men of this kind. Their old home plainly tells us they were not, desiring rather a peaceful seclusion than the ambitions and contentions of courts and camps. Defence, not defiance, was the[47] watchword of those who lived in this picturesque hollow, barred in at night from the chances, surprises, and alarums of the riotous outer world.

The interior arrangements include original fireplaces, carved and painted ceilings, and a chapel. The grounds without and the forest trees beyond are green and luxuriant beyond belief outside the wonders of fairy tales—to whose realms, indeed, Ightham Mote more nearly belongs than to this workaday world. The moat, fed by a crystal stream, is clear and sparkling, and birds and butterflies skim over it and into the thickets of shrubs and wild flowers like so many joyous souls escaped from a life of care and pain to rejoice for ever and ever in sunshine and a careless existence. It is with a sigh that the Londoner turns away from a place whose loveliness fills him with a glorious discontent.

Many of the Selbys lie in Ightham Church, and some have their memorials in the little domestic chapel attached to the Mote House. Dame Dorothy Selby was a very phœnix of all the virtues, if we may believe her epitaph, wherein she is compared with a number of notable biblical characters, all very edifying.

The monument to her “pretious name and honor” is still to be seen on the chancel wall of Ightham Church. She appears to have been a person of many accomplishments. Firstly, a needlewoman of considerable parts—

Then it is claimed for her that she discovered the Gunpowder Plot, in these words—

Moreover—

| Who put on Immortality |

} in the yeare of her { | Pilgrimage 69 March 15. Redeemer 1641. |

O rare and most estimable dame, paragon and phœnix, and very Gorgon of all the virtues, how little are your qualities hid in this, your epitaph!

She looks all those things and more, in her marble bust, that with thin, sharp-pointed nose, and with drawn-down mouth, gives her a very vinegary expression. There can be little doubt of it, the old lady was that terrible creature, the Superior Person.

There is, opposite this worthy lady’s monument, the stone effigy of a very much earlier inhabitant of the Mote—Sir Thomas Cawne, who died in 1374. He is represented in armour, his calm face peering out of his hauberk and chain mail. The window to his memory, over his tomb in the north chancel wall, made according to the directions in his will, still remains.

There will, doubtless, be those who, resting content with Ightham Mote, will decline to follow these wheelmarks farther, for such a place is worth lingering over. For the insatiable sight-seer who will proceed, the[49] way lies as straight ahead as the winding lane will permit to Shipborne, where we turn to the left, passing through the village, and then, in little over a mile, to the right, at the cross-roads, going, with Frith Woods on the left and Dene Park on the right, for two miles farther, turning left where a sign-post points to Hadlow. Many hollows are descended into on the way, where tiny streams run across the wooded roads, and there are correspondingly sharp rises.

Mereworth village, on the borders of the wide-spreading Mereworth Woods, lies up a turning to the right, on the fine broad road leading to Maidstone. Mereworth is remarkable for its hideous church, resembling some of Wren’s City of London churches; with a classical colonnaded porch, windows like those of a factory, and great overhanging eaves, very like those of that “great barn,” St. Paul’s, Covent Garden. A tall steeple, with classic peristyle, completes the outward composition. Now turn to the interior; an even more pagan sight than the exterior prepares the stranger for. It is like a huge room, and is divided into nave and aisles by plaster pillars, painted and grained to resemble marble, with all the fittings in a correspondingly classic style. This objectionable building owed its origin in 1748 to the eighth Earl of Westmoreland, whose seat, Mereworth House, near by, is built somewhat in the same style. The only relic of the old church is the grand monument of his ancestor, the first earl. In the churchyard is the tomb of Evelyn Boscawen, Viscount Falmouth, who married (the epitaph tells us) Baroness Le Despenser.

Here we are come into the Vale of Medway, and two miles of a beautiful road bring us to Wateringbury, where little rills, trickling down to join the greater stream, nourish all these leafy hillsides into such dense growth. There is a curious relic in Wateringbury Church—an old wooden club or mace three feet and a half in length, known as the “Dumb Borsholder,” belonging to the hamlet of Pizein Well, in the Manor of Chart. This was the central figure in the court-leet of the manor, and on those occasions was carried into the court by the head tything-man, or borsholder, as a symbol of authority, much in the same way as the Lord Mayor of London takes the Mace with him on state occasions. But the “Dumb Borsholder” seems to have been regarded both as a symbol and as a person; and, carried into court with a handkerchief passed through a ring at one end, had naturally to be answered for when called upon to put in an appearance. The other end of this club is provided with an iron spike, like a bayonet, with which to break open the doors of refractory tenants. Retired from active service so long ago as 1748, this formidable weapon is now chained up in the vestry.

From here to Teston the way is bordered by hop gardens. Teston Bridge, crossing the Medway in seven Gothic arches, is a beautiful old structure, but Teston Church, although its shingled spire on[51] the hillside looks picturesque, does not improve on closer acquaintance, having been classically re-cast, something in the manner of Mereworth.

Here we turn left, with a three-miles’ run to St. Leonard’s Street and West Malling, off to the right, where the ruins of Malling Abbey are to be seen. Straight ahead is Offham, where one must look out for the quintain on the green, a modern replica of the old English village jousting instrument, consisting of an upright post with a pivoted arm. One end of the arm is thick, and from the other was suspended a bag of flour, or some heavy object. The players in this old sport tilted on horseback at the thickened end. If their lance or staff struck it, and they were not nimble enough, the other end, swinging round, would hit them on the side of the head, unhorsing them. When the[52] hop-pickers are let loose upon the country, with every recurrent autumn, the quintain is taken in until they have gone home again.

A mile or so beyond this point our way crosses the Sevenoaks to Maidstone road, and goes in very hilly fashion to Wrotham, called “Rootam” by the natives. Notice a stone built into the wall by an inn, recounting how a Lieutenant-Colonel Shadwell was shot dead by a deserter, over a hundred years ago. From Wrotham it is a mile distant to Borough Green and Wrotham Station, whence train to Sevenoaks and London.

Within this circuit of just upon thirty miles much that is characteristic of Kent, the “Garden of England,” is to be found; much that is busily commercial, a goodly proportion of beautiful, unfrequented country, old-world villages on unspoiled stretches of river, and other villages with many mills polluting the Darenth on its way to the turbid Thames. Kent, in short, is a very varied county, growing fruit and hops, and, by reason of its waterways and its nearness to London, dotted over with factories; and this district here mapped out is a very good exemplar of the whole. Erith, which may be made the starting-point of this ride, is an interesting place, overlooking the Thames, here half a mile wide and crowded with all kinds of shipping; a tarry, longshore, semi-nautical village—or town, should it be called?—with a crazy little wooden pier boasting a picturesque summer-house kind of building at its end, and with a puffing engine of a miniature kind noisily playing at trains along it all day long, and performing mysterious shunting operations in collusion with a few lilliputian trucks. Engine and trucks to the contrary and notwithstanding, Erith is very delightfully behind the times, and is much more in accord with the days of Nelson and Dibdin and the era of tar and hemp than[54] with our own period. Romantically decayed defences against the inroads of the Thames bristle along the foreshore, like so many black and broken teeth; over across the estuary is the Essex shore, and here, at the back, at Purfleet, are, actually, chalk cliffs, giving place along the course of the river to marshes. “R.T.Y.C.” is the legend one reads on the jerseys of many prosperous-looking sailormen lounging here, for Erith is the headquarters of the Royal Thames Yachting Club.

The two miles between Erith and Crayford need detain no one. Half the distance is an ascent, and the rest goes steeply down to the valley of the Cray, where Crayford, the first of the series of villages whose names derive from that little stream, is situated. With all the good-will in the world it is difficult, if not impossible,[55] to say anything in favour of Crayford, which appears to afford congenial harbourage to all the tramps who pervade that peculiarly tramp-infested highway, the Dover road. “A townlet of slums” sums up the place. But note the long rhyming epitaph to Peter Isnell, parish clerk, on the south side of the hilltop church—

and so forth.

The first turning out of the dusty high road to the right, and then to the left, for Bexley (not Bexley Heath, which is quite another and a very squalid place) leads to a pleasant road following the river. From it, on the left hand, within a mile, a glimpse is gained of Hall Place, a beautiful old Tudor mansion built in chequers of stone and flint. An excellent view of it may be had by dismounting and looking through the wrought-iron entrance gates. Then comes the long[56] street of Bexley and its curious spire, and a brick bridge by which we cross the Cray, turning sharply to the left, and soon afterwards as sharply to the right. Very pretty is the river scenery just by Bexley Bridge; millhouse and weir and tall clustered trees making a rare picture. North Cray, the next village of The Crays, as the group is locally known, is one mile ahead. Before entering it notice the long avenue on the left leading to Mount Mascal, and then the lengthy, low white house on the right at the beginning of the village. This is the house where Lord Castlereagh committed suicide in 1822. At the interval of another mile is Foot’s Cray, where the road from Farningham to Sidcup, Eltham, and London crosses our route at right angles. The village chiefly lies at the side, along the[57] London road, and the unpretending old church at the back.

A short interval of country road, and then the outlying houses of St. Paul’s Cray, which, with the adjoining town of St. Mary Cray, forms one long street for the length of over a mile and a half, or, including Orpington, which practically joins on, of more than two miles and a half. They make paper on a large scale at St. Paul’s and St. Mary Cray, and the mills are very prominent objects. Much too prominent at St. Mary Cray is a hideous Congregational temple with a verdigris-coloured dome, and just as prominent and as ugly is the railway viaduct that straddles at a great height over the absurdly narrow street.

Orpington was the scene of the publication of Ruskin’s works during a long series of years before they were published in the usual way in London. It is a pretty[58] village, with an Early English church, a tree-shaded wayside pond with miniature waterfalls, and a general air of “something attempted, something done” to realise Ruskinian ideals. A mile and a half beyond Orpington we come down to the cross-roads leading, right to Farnborough, and left to Sevenoaks. In front, on its hillside, is a great red brick house. This is High Elms, Sir John Lubbock’s place. Turning to the left, we reach the hamlet of Green Street Green, and then, in another mile, Pratt’s Bottom. There is a continual four miles and a quarter ascent from here to the crown of Sepham Hill (or Polhill, as it is now generally called) to give the wheelman pause, and to make him wish he had come the other way round. From the Polhill Arms at the summit the average touring cyclist will observe that he has rather a nerve-shaking descent to make, judging from the elevated position he has reached and from the little world of landscape unfolded before him. Caution and a good rim-brake, to keep control over the machine, are, however, all that are necessary, even[59] though the descent be winding. A tree-covered bank on the right hand, flanking the hill with a certain solemnity, would be more impressive still to the cyclist did he know that this is the site of one of the great circle of forts now building for the defence of London. But the stranger is not cognisant of the fact, and so, unhappily, misses a patriotic thrill in passing.

Continuing the wooded descent towards the Weald, look out for a road on the left leading to Otford, a steep and stony mile and a half. Here, intrepid adventurers that we are, we have crossed the watershed and achieved the valley of the Darenth. Otford was the site of one of the sixteen palaces of the Archbishops of Canterbury. It was built just before the Reformation, by Archbishop Warham, in the reign of Henry the Eighth, and resigned by Cranmer to that very masterful monarch. The ruins of it are still to be seen by the church.

Leaving Otford, turn to the left at the cross-roads, and so, beside the railway, to Shoreham Station. The village lies on a by-road to the left. They make paper there also. It was the birthplace of that not sufficiently appreciated African explorer, Commander Lovett-Cameron, untimely dead. In the church are the flags he carried with him on the Livingstone search expedition. Like “Bobs”—who, according to Mr. Kipling, “don’t advertise”—Lovett-Cameron cared nothing for the réclame that makes reputations with the many-headed; unlike him, he missed his proper meed of recognition.

The valley of the Darenth here is very beautiful, and the river at Shoreham expands into the likeness of a great lake. Here is a choice of routes: direct, beside[60] the railway, to Eynesford, or through Shoreham to Eynesford by way of Shoreham Castle and Lullingstone. There is little to choose either way, because the “castle” at Shoreham exists no longer, and Lullingstone Park is forbidden to cyclists. Let us reserve our enthusiasm for Eynesford, an old English village of truly Elizabethan spaciousness, set down in its valley beside the Darenth, with an ancient, eminently sketchable and paintable old bridge spanning the ford that originally conferred the termination of the place-name; with a highly interesting Norman and Early English church, with lofty spire dominating the scene; and with a ruined castle tucked away in a builder’s yard. Little stress need be laid upon Eynesford Castle, because it is now, in short, only a little piece of rubble wall, and therefore to be taken very largely on trust. But the[61] village—to recur to it—is a very beautiful and æsthetically satisfying fact.

Farningham, to which we come after Eynesford, is only moderately interesting. Also, for the benefit of those who may follow in these tracks, it may be noted that it is in a hop-growing district, and when the hop-pickers are let loose upon it the society is not of the choicest. The village lies on the left-hand road; we pursue our way to Horton Kirby, where are more mills and crooked streets, and thence to South Darenth, where there are many factories and curving roads. Turn acutely (and warily) to the left, and, crossing the river, make for Sutton-at-Hone. Darenth lies off to the right. The church is Norman and Early English, and the walls have a plentiful admixture of Roman tiles. See the church, by all means, but do not take that way to Dartford. Return to the point where the road was left, and go by way of the hamlet of Hawley.