Title: Graham's Magazine, Vol. XXXI, No. 1, July 1847

Author: Various

Editor: George R. Graham

Release date: February 9, 2019 [eBook #58854]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Mardi Desjardins & the online Distributed

Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

from page images generously made available by Google Books

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XXXI. July, 1847. No. 1.

Contents

| Fiction, Literature and Articles | |

| The Slaver | |

| A Pic-Nic at White Lake | |

| Arthur Harrington | |

| General Zachary Taylor | |

| Sally Lyon’s First and Last Visit to the Ale-House | |

| The Islets of the Gulf (continued) | |

| The Love-Chase | |

| Review of New Books | |

Transcriber’s Notes can be found at the end of this eBook.

GRAHAM’S

AMERICAN MONTHLY

MAGAZINE

Of Literature and Art,

EMBELLISHED WITH

MEZZOTINT AND STEEL ENGRAVINGS, MUSIC, ETC.

WILLIAM C. BRYANT, J. FENIMORE COOPER, RICHARD H. DANA, JAMES K. PAULDING,

HENRY W. LONGFELLOW, N. P. WILLIS, CHARLES F. HOFFMAN, J. R. LOWELL.

MRS. LYDIA H. SIGOURNEY, MISS C. M. SEDGWICK, MRS. FRANCES S. OSGOOD,

MRS. EMMA C. EMBURY, MRS. ANN S. STEPHENS, MRS. AMELIA B. WELBY,

MRS. A. M. F. ANNAN, ETC.

PRINCIPAL CONTRIBUTORS.

GEORGE R. GRAHAM, EDITOR.

VOLUME XXXI.

PHILADELPHIA:

GEORGE R. GRAHAM & CO. 98 CHESTNUT STREET.

. . . . . .

1847.

CONTENTS

OF THE

THIRTY-FIRST VOLUME.

JUNE, 1847, TO JANUARY, 1848.

| A Pic-Nic at White Lake. By Alfred B. Street, | 13 | |

| Arthur Harrington. By F. E. F. | 19 | |

| A New Way to Collect an Old Debt. By T. S. Arthur, | 80 | |

| An Indian Legend. By M. | 177 | |

| An Assiniboin Lodge, (Illustrated.) | 328 | |

| Cora Neill. Or Love’s Obstacles. By Enna Duval, | 72 | |

| Evelyn Grahame. A Tale of Truth. By Ellen Marshall, | 97 | |

| Fort Mackenzie. (Illustrated.) | 271 | |

| General Zachary Taylor, (Illustrated.) | 26 | |

| Game-Birds of America, | 269 | |

| Ida Bernstorf’s Journal. By Enna Duval, | 233 | |

| Kitty Coleman. By Fanny Forester, | 262 | |

| Lolah Lalande. A Package from My Old Writing-Desk. By Enna Duval, | 150 | |

| Love’s Last Supper. Or the True Story of a Troubadour. A Provençal Biography. By Wm. Gilmore Simms, (Illustrated.) | 277 | |

| Reality Versus Romance. Or the Young Wife. By Caroline H. Butler, | 101 | |

| Reminiscences of Watering-Places. By F. J. Grund, | 217 | |

| Sally Lyon’s First and Last Visit to the Ale-House. By T. S. Arthur, | 33 | |

| Stock-Jobbing in New York. By Peter Pencil, | 145 | |

| Sophy’s Flirtation. A Country Sketch. By Mrs. M. N. M‘Donald, | 303 | |

| The Love-Chase. A True Story. By Mrs. Caroline H. Butler, | 49 | |

| The Slaver. A Tale of Our Own Times. By A Son of the late Dr. John D. Godman, | 1, 61, 109 | |

| The Islets of the Gulf. Or Rose Budd. By J. Fenimore Cooper, | 37, 85, 133, 181, 241, 288 | |

| The Ring. Or Fibbers and Fibbing. By F. E. F. | 121 | |

| The Village Doctor. Translated from the French by Leonard Myers, | 157, 223 | |

| The General Court and Jane Andrews’ Firkin of Butter. By Seba Smith, | 168 | |

| The Stratagem. By Mrs. Alfred H. Reip, | 193 | |

| The Man with the Big Box. By G. G. Foster, | 204 | |

| The Sportsman. By Frank Forester, | 208 | |

| The Last Adventure of a Coquette. By T. Mayne Reid, | 253 | |

| The Three Calls. By H. L. Jones, | 257 | |

| The Silver Spoons. By the Author of “Key West and Abaco”, | 264 | |

| The Darkened Hearth. By Henry G. Lee, | 296 | |

| The Widow and the Deformed. By Mrs. Caroline H. Butler, | 309 | |

| The Rash Oath. Translated from the French. By Mrs. Jane Tayloe Worthington, | 324 | |

| Was She a Coquette? By Mrs. Lydia Jane Pierson, | 174 | |

POETRY.

| A Bacchic Ode. By J. Bayard Taylor, | 18 | |

| A Valentine. By R. H. Bacon, | 18 | |

| A Winter’s Night in the Wilderness. By T. Buchanan Read, | 203 | |

| Brain Work and Hand Work. By Charles Street, | 167 | |

| Burial of a German Emigrant’s Child at Sea. By J. T. F. | 214 | |

| Blind! By Mrs. Joseph C. Neal, | 294 | |

| Carolan’s Prophecy. By William H. C. Hosmer, | 48 | |

| Death of the Gifted. By J. Wilford Overall, | 256 | |

| Elva. By Edward Pollock, | 128 | |

| Echo. By John S. Moore, | 180 | |

| Fair Wind. By J. T. Fields, | 261 | |

| Flowers. By S. E. T. | 268 | |

| Hermione. (With an Engraving.) | 214 | |

| Jacob’s Dream. (With an Engraving.) | 149 | |

| Jenny Low. By C. M. Johnson, | 176 | |

| Linolee. By J. Wilford Overall, | 71 | |

| Lines for Music. By G. G. F. | 179 | |

| Lucretia. By Henry B. Hirst, | 239 | |

| Lines at Parting. By T. Trevor, | 256 | |

| Miriam. By E. M. Sidney, (Illustrated.) | 36 | |

| Midnight, and Daybreak. By Mrs. J. C. Neal, | 207 | |

| My Loved—My Own. By W. H. C. Hosmer, | 295 | |

| Ode to Time. By W. Gilmore Simms, | 202 | |

| On a Sleeping Child. By S. E. T. | 323 | |

| Pioneers of Western New York. By Wm. H. C. Hosmer, | 207 | |

| Rosabelle. By “Caro,” | 58 | |

| Rural Life. (Illustrated.) | 268 | |

| Sonnet from Petrarch, on the Death of Laura. By Alice Grey, | 32 | |

| Sonnet. To a Young Invalid Abroad, | 36 | |

| Sonnet to ——. By R. H. Bacon, | 180 | |

| Sunset in Autumn. By Harriet M. Ward, | 240 | |

| Sonnet. By T. E. V. B. | 286 | |

| Sonnet. By Miss Mary E. Lee, | 302 | |

| Stanzas for Music, | 329 | |

| To Evelyn. By Kate Dashwood, | 12 | |

| To ——, at Parting. By Caroline A. Briggs, | 32 | |

| The Winged Watcher. By Fanny Forester, | 55 | |

| The Stricken. By Robt. T. Conrad, | 58 | |

| The Dreamer. By Alice G. Lee, | 77 | |

| The Demon of the Mirror. By James Bayard Taylor, | 78 | |

| The Lifted Veil. By Miss H. E. Grannis, | 83 | |

| Thou Art Cold. By S. | 106 | |

| The Spanish Lovers, (Illustrated.) | 106 | |

| To a Century Plant. By Mrs. Jane C. Campbell, | 120 | |

| The First Loss, (Illustrated.) | 154 | |

| The Invalid Stranger. By Mary E. Lee, | 173 | |

| The Lay of the Wind. By Lilias, | 180 | |

| The Mariner Returned. By Rev. E. C. Jones, | 214 | |

| The Deserted Road. By Thomas Buchanan Read, | 232 | |

| The Old Man’s Comfort. By Lieut. A. T. Lee, U. S. A. | 232 | |

| The Early Taken. By Wm. H. C. Hosmer, | 240 | |

| The Rustic Dance. By Elschen, | 267 | |

| The Last Tilt. By Henry B. Hirst, | 287 | |

| The Wayside Dream. By J. Bayard Taylor, | 302 | |

| Thou’rt Not Alone. By E. Curtiss Stine, | 308 | |

| The Autumn Wind. By Jane C. Campbell, | 329 | |

REVIEWS.

| Lives of the Early British Dramatists. By T. Campbell, Hunt, Darley and Gifford, | 59 | |

| Washington and his Generals. By J. T. Headley, | 59 | |

| Homes and Haunts of the Most Eminent British Poets. By William Howitt, | 107 | |

| The Orators of France. By Viscount de Cormenin, | 108 | |

| History of the Conquest of Peru. By Wm. H. Prescott, | 155 | |

| Modern Painters. By a Graduate of Oxford, | 155 | |

| Conversations in Rome. By William Ellery Channing, | 155 | |

| Life and Religious Opinions and Experiences of Madame de la Mothe Guyon. By T. C. Upham, | 156 | |

| The Autobiography of Goethe. Edited by Parke Godwin, | 156 | |

| Morceaux Choisis des Auteurs Modernes. By F. M. Rowan, | 156 | |

| 1776, or the War of Independence. By Benson J. Lossing, | 156 | |

| Philosophy in Sport Made Science in Earnest. From the Sixth London Edition, | 156 | |

| Men, Women and Books. By Leigh Hunt, | 215 | |

| Louis the Fourteenth, and the Court of France in the Seventeenth Century. By Miss Pardoe, | 215 | |

| The Good Genius that Turned Every Thing into Gold, or the Queen Bee and the Magic Dress. By the Brothers Mayhew, | 215 | |

| The Complete Angler, or the Contemplative Man’s Recreation. By Izack Walton, | 215 | |

| Fresh Gleanings: or a New Sheaf from the Old Fields of Continental Europe. By Ik. Marvel, | 216 | |

| The Months. By Wm. H. C. Hosmer, | 216 | |

| O’Sullivan’s Love. By Wm. Carleton, | 216 | |

| Reminiscences of Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Robert Southey. By Joseph Cottle, | 274 | |

| The Public Men of the Revolution. By Hon. Wm. Sullivan, LL. D., | 275 | |

| Budget of Letters, or Things which I Saw Abroad, | 275 | |

| Evangeline, a Tale of Acadie. By Henry Wordsworth Longfellow, | 330 | |

| Washington and the Generals of the American Revolution, | 332 | |

MUSIC.

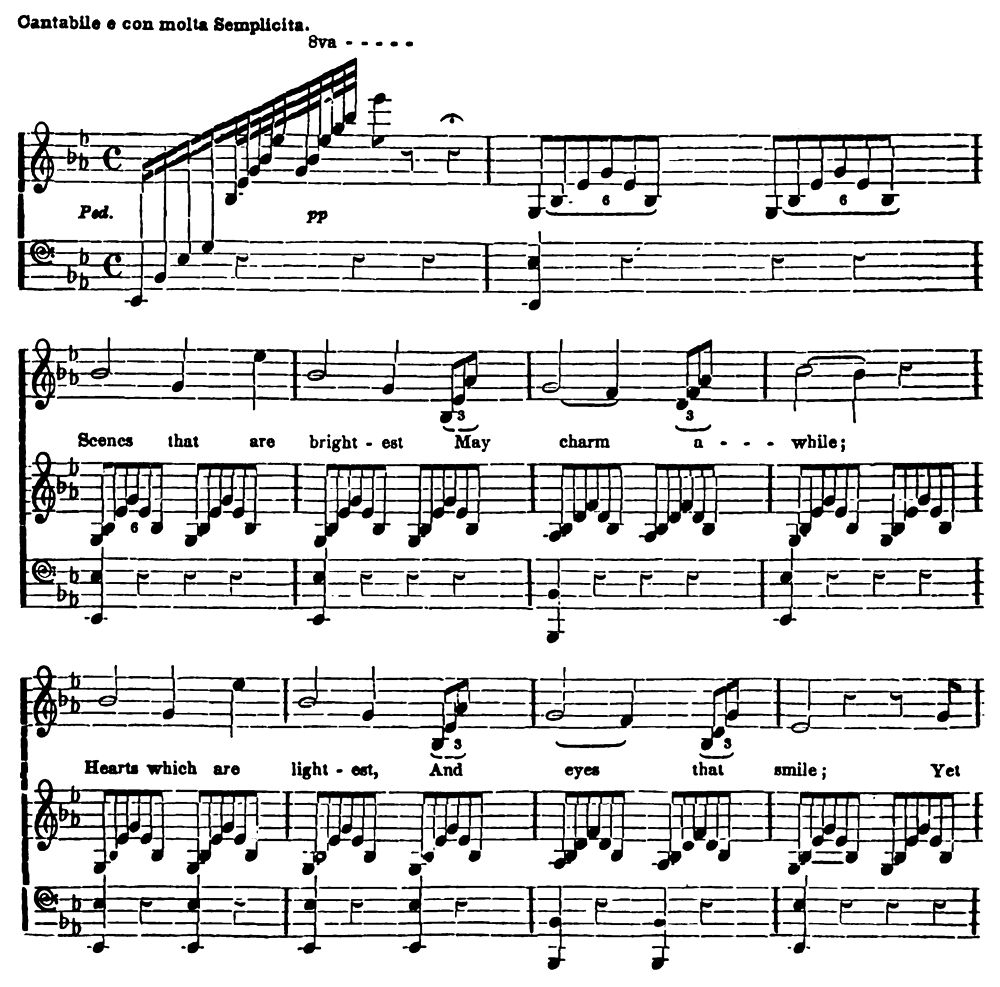

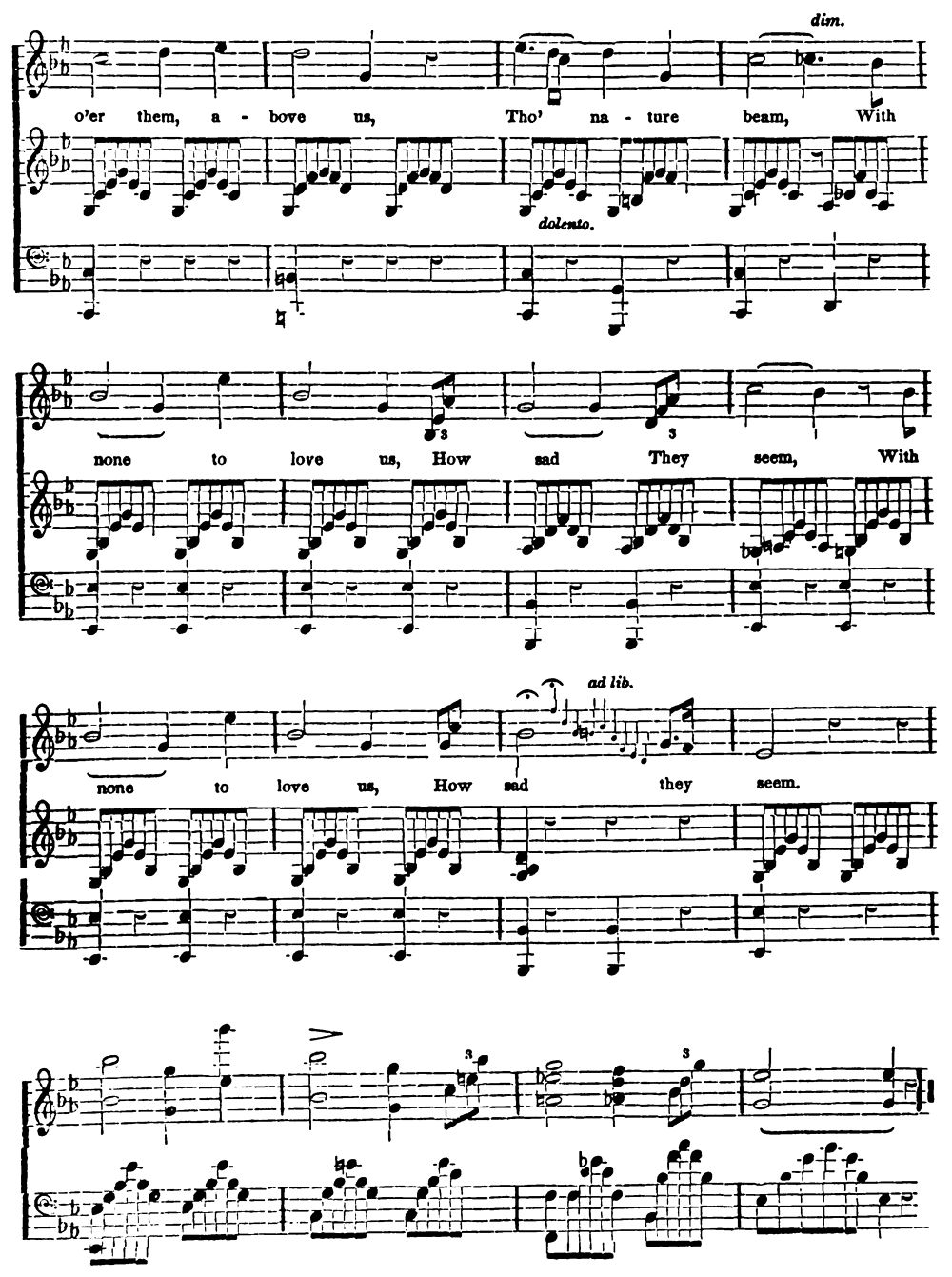

| Scenes that are Brightest. Popular Song from Maritana. Composed by W. V. Wallace. | 56 | |

| When Eyes are Beaming. Written by Heber. Music by Keller. | 212 | |

| The Fisher Boy Jollily Lives. A Glee for Four Voices. Words by Eliza Cook. Composed and Arranged by W. R. Wright. | 272 | |

ENGRAVINGS.

| Portrait of Gen. Taylor, engraved by J. Sartain, Esq. | ||

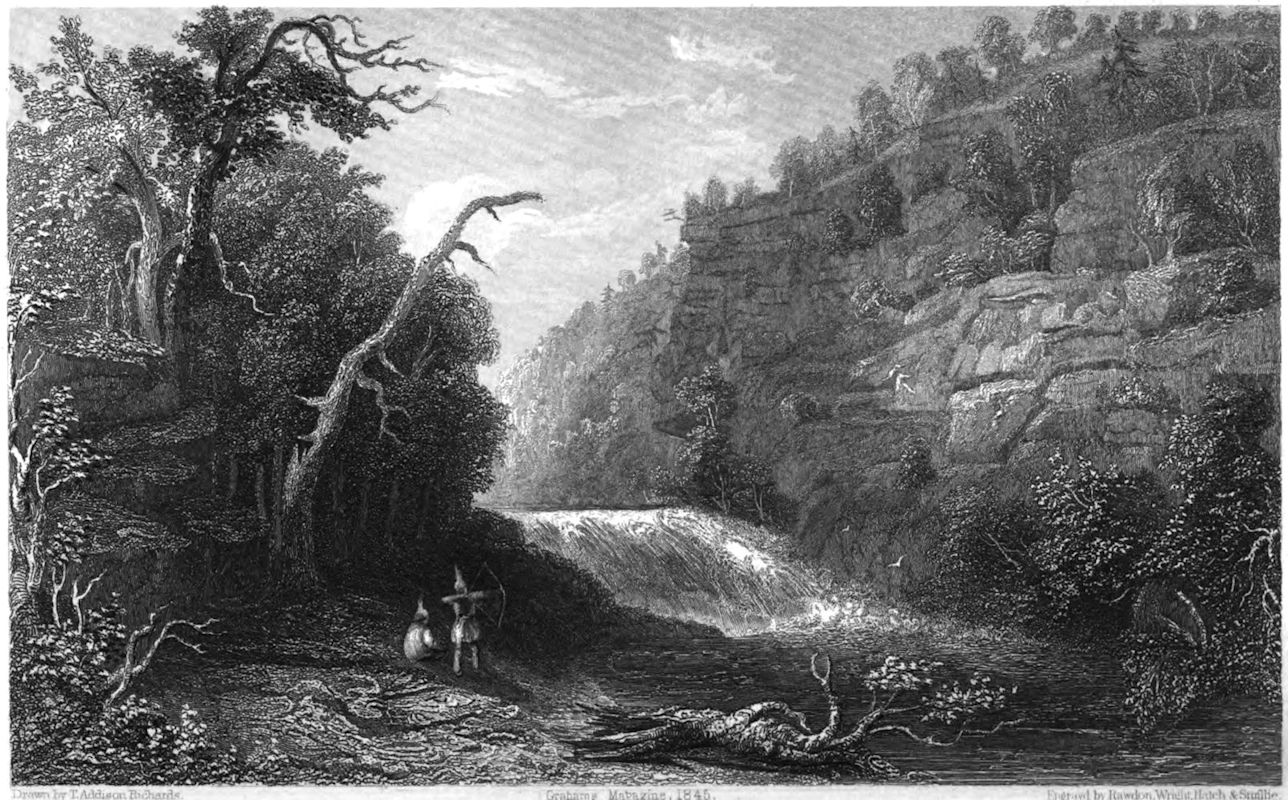

| Tallulah Falls, engraved by Smillie. | ||

| Miriam, engraved by A. L. Dick. | ||

| The Spanish Lovers, engraved by A. B. Walter. | ||

| Paris Fashions, from Le Follet. | ||

| Victoria, Princess Royal, engraved by A. L. Dick. | ||

| Jacob’s Dream, engraved by A. L. Dick, Esq. | ||

| The First Loss, engraved by H. S. Wagner. | ||

| Hermione, engraved by Jackman. | ||

| The Sportsman, engraved by A. L. Dick. | ||

| Paris Fashions, from Le Follet. | ||

| Rural Life, engraved by J. Banister. | ||

| Fort Mackenzie, engraved by Rawdon, Wright & Hatch. | ||

| Paris Fashions, from Le Follet. | ||

| The Troubadour, engraved by Ellis. | ||

| An Assiniboin Lodge, engraved by Rawdon, Wright & Hatch. | ||

| Paris Fashions, from Le Follet. | ||

Drawn by T. Addison Richards. Graham’s Magazine, 1845. Engraved by Rawdon, Wright, Hatch & Smillie

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XXXI. PHILADELPHIA, JULY, 1847. No. 1.

A TALE OF OUR OWN TIMES.

———

BY A SON OF THE LATE DR. JOHN D. GODMAN.

———

Come sit thee down, my bonnie, bonnie lass,

Come sit thee down by me, love,

And I will tell thee many a tale

Of the dangers of the sea, love.

Song.

Many modern authors, of eminent ability, have employed their time and talents in writing tales of the vast deep; and of those “who go down to the great sea in ships;” but they nearly always take for the hero of their story some horrible and bloody pirate, or daring and desperate smuggler, of the sixteenth or seventeenth century; characters that the increased number, strength and vigilance of armed cruisers, and the energy of the excise officers, have long since driven from the face of the ocean, in these capacities: and who now can only be found in that lawless traffic, the Slave Trade.

Yet that in itself comprises all the wickedness and blood-thirstiness of the pirate; the recklessness and determination of the smuggler; with the coolness, skill, and knowledge of the merchant captain.

It is true, that by taking a distant era for the date of their themes, they have a more widely extended field for the play of their imaginations, and are less liable to severe criticisms on the score of consistency; but, at the same time, they lose that hold on the feelings of their readers, that a tale of the present will ever possess; for instead of thinking of the characters, the incidents, and the scenes, as things that were, or might have been, a century ago, our imaginations are vividly impressed with the fact that they even now exist. And whilst we are quietly perusing some thrilling tale, events equally startling, deeds as dark and desperate, scenes as horrible, may be transpiring at that instant, on the bosom, or the borders, of the same ocean, that laves with its salt waters the shores of our own happy land.

But the present will be too far in the past, if we lengthen our introduction: so e’en let us to our story.

It was a moonlight night, early in the year 1835, when two young girls were reclining on a lounge, in the piazza of a beautiful and luxurious-looking house, situated near the margin of one of the most magnificent bays that indent the eastern extremity of the Island of Cuba.

The prospect was enchanting; such a one as can only be found within the tropics; the limpid waters of the bay, extending for fifteen miles, appeared in the soft and mellow radiance of the full moon a field of crisped silver; and the lovely islands with which it was dotted looked like emeralds upon its bosom; the range of hills, blue in the distance, charmingly relieved the brightness of the water, and the tall cocoa-nut trees, with their bare trunks and single tuft of leaves at top, reminded us of the genii of the night, overlooking these fair domains: a cool and gentle breeze from the ocean made music as it murmured through the foliage, and gathering sweet perfume from the flowers it kissed in its passage, reinvigorated, as it fanned, the languid frames of those overcome by the intense heat of the just spent day.

And in perfect accordance with the softness, the mildness, and the beauty of the scene, were the two lovely beings on the piazza. In the cold climate of the north, they would have been but children, so few summers had they seen; but under the influence of their own burning sun, they were just expanding into early, but most delicious womanhood.

La Señorita Clara, the eldest, had entered her sixteenth year; her sister, La Señorita Francisca, was one year younger.

They were the only children of Don Manuel Velasquez, a Spaniard of immense wealth, and of noble family, who in his youth had been sent from Spain, in a government capacity of some importance, to Cuba. He became deeply attached to, and married a beautiful Creole girl, and settled upon the island, after the expiration of his official engagement, rather than remove his loved Cubanean bride from the scenes of her childhood.

She, the idol of his youth and the treasure of his riper years, had died, a short twelvemonth prior to the commencement of our tale; and Don Manuel, who was a Spaniard of the old school, proud, stern, bigoted, and of strong prejudices, a great stickler for etiquette and form, though naturally kind-hearted and hospitable, gave sufficient evidence of his sorrow, by his increased devotion to, and fondness for, the two sweet pledges of his heart’s only affection, the legacy of his departed wife; he seemed to live but to minister to their wants; their slightest wish was his law; and every thing that wealth could command, or kind solicitude imagine, was brought to increase their happiness.

Clara, the eldest, was rather above the medium height; with a graceful figure, jet-black hair, dark eyes, perfectly formed features, and a complexion such as is only found in the daughters of Spain, (and rarely there,) as purely white as alabaster; and was surpassingly beautiful, notwithstanding the haughty expression of her mouth and eye, and the air of command that pervaded her motions.

Francisca was the opposite of her sister; rather too short than otherwise; her features were not so regular as Clara’s; but the love and kindness that shone forth in her brilliant eye, and the sweet smile that played around her mouth, more than compensated for any want of symmetry.

Their dispositions were as different as their outward contour. Clara was cold, proud and haughty; inheriting all the sterner traits of her father’s character: she was calculated to figure in the gay world, or to shine in a ball-room.

Francisca was all heart, with a gentle and affectionate disposition, yet capable, when her feelings were interested, of the greatest exertions and sacrifices; she was one born to love and be loved; and was made for either unequaled happiness or misery.

But let us return to where we first discovered them, in the piazza of their father’s house. They had been for some time quietly contemplating the fairy scene, when the silence was broken by the soft musical voice of Francisca.

“Hermanita cara, mi alma,[1] what troubles you? How, this lovely evening, can you look so sad?”

“Have I not enough to distress me, Niña?[2] Who on earth, but you, could be cheerful and contented cooped up in this dull out-of-the-way place?”

“Oh, Clara! how can you call this lovely spot dull? I wish so much that father would let me stay here all the year, instead of spending half of it in that nasty Havana, where one is bothered all the day with foppish cavalleros, dressed to death, and thinking of nothing but their own sweet selves; and all the evenings with parties or the theatre.”

“Well, Miss Rusticity, you can stay here, and flirt with boors, and look at the water and flowers, as long as you please; but I intend to have father take me to that “nasty Havana,” as you call it, next week.”

Her words Francisca found were true, for in a few days after this conversation, an unusual bustle about the quiet mansion, the harnessing of horses and mules, and the noise of servants, gave evidence of a removal. The family were about starting for the capital of the island. We will not, however, accompany them over their long and rough road, but will join them in Havana, the day after their arrival at Don Manuel’s splendid town-house.

Clara was all joy, gayety and animation at the thought of again being in the city, where she shone the observed of all observers; but Francisca was moved to tears whenever she contrasted the city with their beautiful country-seat; and knowing that she was obliged to attend a large ball that evening, given at the palazza, by the governor-general, she felt more than usually dull. The evening came, and in a sea of light, a flood of music, amidst the waving of plumes, the rustling of silks, and the flashing of jewels, the sisters appeared, the most lovely of all the galaxy of beauty that ever surrounds the vice-royal court in Cuba.

Clara was in her natural element in the light and graceful dance, or attended by a circle of admirers, returning their compliments with flashes of wit, or sallies of gay repartee, she wished for no greater happiness.

Francisca was soon fatigued and ennuied with the excitement, and retired to the shelter of a large window, shaded by orange trees in blossom, where she was comparatively alone; and sinking into one of those dreamy reveries young ladies so much delight in, had nearly forgotten the ball, when she was aroused by a rich and manly voice at her side, asking for the honor of her hand in the next dance. There was something so fascinating, so deep and tender in the tones of the speaker, that though not inclined to grant his request, she paused ere she denied him; and turning around, discovered in the person who addressed her a young American gentleman, to whom she had been introduced in the early part of the evening, and whose tall, graceful and well knit figure, sparkling and intelligent eye, beautiful mouth, and commanding air, had unconsciously made a deep impression upon her fancy, and whose image had usurped a large share of her late meditations: her reluctance to join the dance instantly vanished, and, for nearly the first time in her life, she was willingly led on the floor.

Cotillion after Cotillion they were partners, and envy was excited in the breast of many a fair Havanarean, at seeing one so young engrossing the attention of the handsomest cavalier in the room.

But Francisca knew it not; the dulcet tones of her partner’s voice, his entertaining conversation, as with a keen satirical tongue, and deep knowledge of the world, he criticised the beaux and belles of the ball-room; or with feeling and sentiment discoursed of music, poetry, or love, his delicate flattery, and assiduous attentions, rendered her insensible to aught beside, and riveted her every thought; and when her sister sought her, at a late hour, to accompany her home, it was with surprise that she discovered the rapid flight of time, and with feelings unaccountable, new and strange, such as woman only experiences once, she bid her attendant of the evening good-night, and stepped into the carriage.

Many a jest had Francisca to bear, after this evening, from her sister, in consequence of a new taste that seized her, for constant rides on the Paseo, and nightly visits to parties or the theatre, in her unsuccessful endeavors to again meet with the gallant of the governor’s ball, who never since had been absent from her mind.

But she was not soon destined to enjoy this pleasure, which was now the great hope of her life. For with all the impetuosity and ardor of her nature and climate, she had yielded to this acquaintance of a night, the rich and inappreciable treasure of her fond heart’s first love.

My fair readers may charge Francisca with want of modesty, or proper maiden delicacy, in thus yielding her young affections to the first assault; but they will unfairly judge her, and do wrong to the devoted, passionate, and enthusiastic daughters of the torrid zone, whose blood, scorning the well-regulated, curbed, and restrained pulsations of their more northern sisterhood, flows, flashes, bounds through their veins, with the impetuosity of an Alpine torrent, but with the depth and strength of a mighty river.

Their heart is in reality the seat of their life; all else, prudence, judgment, selfishness, every thing, bows to its dictates; but in this love they are constant, devoted, self-sacrificing, changing their feelings but with life.

|

Hermanita cara, mi alma—Dear sister, my soul. |

|

Niña—Child. |

——

I heed not the monarch,

I fear not the law;

I’ve a compass to steer by,

A dagger to draw.

Song.

In a secluded cove, formed by a bend in a small river, that empties its waters into the sea a few miles from Havana, whose mouth, bare thirty yards in width, would scarce be discovered by a stranger, or casual observer, so rankly and luxuriously do the mangrove-bushes grow upon its banks, and even in the water, that sailing within a hundred feet of the shore, no break or indentation is visible in the line of vegetation, lay at anchor one of the most beautiful and symmetrical top-sail schooners that ever left the port of Baltimore.

The great tautness and beautiful proportion of her masts, the length of her black fore-yards, the care displayed in the furl of her sails, and the tautness and accuracy with which her rigging was set up, would have convinced one at a distance that she was a man-of-war; this impression would have been strengthened, upon a nearer approach, by the fresh coat of jet-black paint upon her splendidly modeled hull, and the appearance of seven pieces of bright brass ordnance; one a long eighteen, on a pivot amidships, the others short carronades, three a side, ranged along her spotless deck, holy-stoned until it was as white as chalk; the ornamental awning stretched fore and aft, the neatness and care with which the running gear was stopped and flemished down, and the bright polish of all the metal work inboard, also indicated the authority and discipline of the pennant.

But the absence of that customary appendage to a cruiser, the lack of an ensign, and the total want of uniform, or uniformity, in the large crew who were scattered over her deck, enjoying or amusing themselves, in the shade, with a greater degree of license than is allowed in any regular service; in groups between the guns, and on the fore-castle, some were gambling, some spinning yarns, others sleeping, and nearly all smoking, combined with their motley appearances, for almost every maritime nation had contributed to form her compliment: Spaniards, Portuguese, Germans, Swedes, Frenchmen, Englishmen, Americans, mulattoes and swarthy negroes, were to be distinguished at a glance, and precluded the idea of her being a regularly commissioned craft: whilst the suppressed tones of the men’s voices, the air of subordination that pervaded their deportment, and the apparent sanctity of the quarter-deck, evinced a greater degree of rule and order than is to be found in a pirate.

She was neither man-of-war, bucaneer, nor honest merchantman, but the celebrated slaver “La Maraposa;”[3] who, for three years, had been setting at defiance the whole naval force on the African station; and many were the tales, current in the squadron, of her unrivaled speed, and the courage and address of her notorious captain.

Two persons were to be seen slowly pacing the schooner’s quarter-deck; one, who seemed to be the captain, was tall, with a breadth of shoulders, smallness of waist, and elasticity of motion, that promised an uncommon degree of muscular strength, united with great agility. His dress was simple; an embroidered shirt of fine linen the only upper garment, sailor pants, of white drilling, kept in their place by a sash of crimson silk around the waist; a black silk handkerchief, loosely knotted around his finely formed neck, which, with white stockings and pumps on his feet, and a broad Panama sombrero on his head, comprised the whole of his attire, and, though scant, it accorded well with the heat of the day, and showed to advantage the perfection of his form.

His face, when under the influence of pleasant emotions, or lit up by a smile, was eminently handsome, and would at once have been recognized as that of the American who had led captive the heart of Francisca at the governor’s ball. But when excited, as he now seemed to be, by evil passions, there was a fierceness and recklessness in his eye, and an expression of coolness and determination about his mouth, that rendered his countenance fascinatingly fearful.

The other was a Spaniard, who held the situation of first officer on board the Maraposa, a stout, seaman-like personage, with nothing remarkable in his appearance, except a look of daring and dogged resolution in his deep-brown eye and square lower jaw.

They had been for some time quietly continuing their circumscribed walk, when the silence was broken by the captain in a voice of suppressed anger, addressing his mate with —

“It is both foolish and boyish, I know, Mateo, to let the remembrance of that whippersnapping lubber’s words chafe me so; but to have heard him, he, who never knew disappointment, unkindness, thwarted exertions, or suspicion; and who, fresh from his lady mother’s drawing-room in London, is as proud of his new ten-gun brig, and first command, as a child of his plaything; to have heard him criticising the character of ‘Charles Willis,’ and branding him with the name of ‘outlaw!’ ‘heathen!’ ‘villain!’ ‘brute!’ and boasting to the ladies at the ball that his course would soon be run; for he, the silk-worm, intended, ere a month was past, to capture his vessel, or blow her out of the water. Caraho! he had better never cross my path—it was as much as I could do to keep my knife out of his heart even then.”

“Caramba!” exclaimed Mateo, “he will be likely to meet with disappointments enough, before he has the pleasure of capturing the little Butterfly; and he will probably find our long Tom a match for his ten barkers, even if he perfumes his balls. But, pesté, think no more of the fool, señor capitan; and wishing him ‘buen vega a los infiernos,’[4] is it not time for us to be getting under way?”

“Yes; pass the word for all hands up anchor and make sail.”

The shrill tone of the boatswain’s pipe, was soon heard, and the celerity with which the anchor was got, catted and fished, and sail made upon the schooner, proved her crew to be both active and efficient, if they were of many colors; for in five minutes after the call was first sounded she was under sail, moving down the river, and in twenty more was standing away from the shore of Cuba, with a fresh breeze, at the rate of eleven knots an hour, bound to the coast of Africa.

The Maraposa was seven days out, and it had just struck four bells in the mid-watch; the night was clear and star-light; a fresh wind was blowing from the southward and eastward, making it about three points free for the schooner—her best trim for sailing; naught was to be heard on her decks but the ripple of the water, as it curled up and divided before her wedge-like bow; so deathly silent was every thing, that had it not been for the figure of the man at the wheel, the mate leaning against the weather bulwark, and the outline of the look-out on the cat-head, giving evidence of human agency, she would have seemed some ocean-spirit, cleaving its way through its native element; the rest of the watch stowed away between the guns, sleeping, or, in sailor phrase, “caulking,” were invisible, when the look-out on the fore-topsail yard sang out, “Sail ho!”

This sound, so agreeable to the ears of a merchantman, has a very different effect upon the tympanum of a slaver—for, expecting in every sail to find an enemy, they desire no greetings on the ocean.

The mate, instantly aroused, called out in quick, short tones, “Where away?”

“Dead astern, sir,” answered the look-out.

“Can you make her out?”

“No, sir, not yet; she’s square-rigged, but so far I can’t tell whether brig or ship.”

“Very well; a stern chase is always a long one. Keep your eye on her, and let me know when you can make her out.”

“Ay, ay, sir.”

But it was not until after daybreak that they were able to make out the character of the sail—for the vessel had never yet been met with that could overhaul the Maraposa, going free in smooth water, and the stranger had not gained a foot on her. She was now discovered to be a large man-of-war brig, under a press of canvas, apparently in pursuit of the slaver. The officer of the watch went below to report to the captain, and was surprised by the eager voice with which he asked if he had ever seen the brig before, and if he knew her build—for the schooner had been chased so often, that her crew knew all the men-of-war on the station; and having always escaped with impunity, they had the most perfect reliance in the superior qualities of their own craft, so much so, that a vessel astern was regarded with scarce more interest than a floating log. With his curiosity, therefore, a good deal excited to understand the unusual anxiety of his captain, the officer replied that he thought the strange sail was an Englishman, and was sure she was an entirely new vessel; and, returning on deck, took a long and close survey of the brig, to see if he could find any thing about her more alarming than in the hundred other vessels of the same class that had pursued them; but all he could discover was, that she was a large ten-gun brig, of English build, and seemingly new; and laying down the glass, would have given himself no further trouble about the matter, had not the captain, just coming on deck, picked up the telescope, and after one steady look at the Englishman, called out, “Man the top-sail and top-gallant clew-lines and buntlines; settle away the halyards; let go the sheets; clew up; lower away the flying-jib;” and looking over the bulwarks a moment, to note the decreasing speed of the schooner, ordered the fore-sail to be lowered.

Thus leaving the vessel under only her main-sail, jib, and fore-topmast stay-sail—orders so unusual in the face of an enemy, created some surprise in the crew; but accustomed to obey, without stopping to argue, his commands were quickly executed.

The loss of so much canvas was soon perceptible in the schooner’s progress, for instead of going at the rate of eleven knots, as she had been with her former sail, she now hardly made four—and the brig astern was rapidly gaining upon them; this gave Willis no uneasiness, and he walked the deck without even looking at her for some time. He then called away the crew of the long gun, and ordered them to put a fresh load in her.

The piece was soon loaded; and the crew were now eager to know what would be the next move. One of the younger sailors stepped up to the captain of the eighteen, who was also captain of the fore-castle—a grim, weather-beaten old tar, whose face bronzed with the sun, and seamed with several scars, gave evidence of many combats, both with man and the elements—and asked if he thought the skipper was really going to have a set-to with the brig—“for, blast me, she’s big enough to blow us all to Davy Jones.”

The old salt, after emptying his mouth of a quantity of tobacco-juice, to enable him to make a reply, hitched up his trowsers with his left hand, slapped his right down on the breech of the gun, and turning his eyes toward the interrogator with huge disdain, said, “Look ye, youngster, if so be as how you’s so mighty uneasy about the captain’s motions, you had better walk aft and ask him; and as you look so uncommon old of your age, perhaps he might give you the trumpet;[5] but as for me, shipmate, it’s now two years and nine months since I joined this craft—and blast my eyes if the chap ever put his foot on a deck that can handle her better, or knows better what he is about, than the one on her quarter-deck; and, curse me, if he was to pass the word to let go the anchor in the middle of the ocean, I would be sure the mud-hook would bring up with twenty fathom, and good sandy bottom; and if it is so we engages that are brig, we will give her h—l, big as she looms.”

The brig by this time was within three-quarters of a mile of the Maraposa, astern, and a little to leeward; and with the intention, as it appeared, of ascertaining the distance, fired one of her bow-chasers—but the ball struck and richocheted over the water far in the schooner’s wake. Captain Willis, with a scornful smile on his lip, told the man at the wheel to put his helm up, and let the schooner’s head pay off. “Watch her as she falls off, Davis,” he said to the old captain of the long gun, “and fire when you get a sight.”

“Steady, so!” was Davis’s reply—and the loud boom of the cannon resounded over the water. The watchful eye of Willis discerned splinters flying from the fore-mast of the brig, and shortly after the top-mast, top-gallant and royal-masts, with all their sails and gear, were seen to totter for an instant, and then pitch over the lee side.

A loud shout from the crew of the slaver attested their gratification at the success of their first shot; and a weather-broadside from the crippled brig, whose head had fallen off from the wind, in consequence of the drift of her wrecked masts, manifested their anger.

The schooner was now put about, and sailing round and round the brig, out of the reach of her short guns, opened upon her a murderous fire from the long eighteen, and had shot away all her spars but the stump of the fore-mast, and was about boarding her; for the brig, with the stubborn determination of a bull-dog, returned gun for gun, in defiance, though her shot all fell short, and refused to surrender, notwithstanding she was likely to be riddled and sunk—for every ball from the schooner crashed through her bulwarks, or lodged in her hull.

So interested had the crew of the slaver been in watching the effect of their fire, that the schooner’s head had been directed toward the brig, and the boarders had been called away, before they discovered, not a mile distant, a large ship dead to windward, bearing down upon them, hand over hand, with studding-sails set alow and aloft on both sides. Her character was not to be mistaken—she was a large first-class sloop-of-war; and the Maraposa, thus compelled to leave her prey, just as it was about to fall in her grasp, fired one more gun, by way of salute, and running up to her main-truck a large white burgee, with “Willis” on it, in conspicuous blue letters, to let her antagonist know to whom she was indebted, crowded all sail and stood away on her former course.

Willis’s sole motive for having thus attacked a much larger vessel than his own, and the capture of which would have been no profit to him, was to be revenged on her captain, whom he knew to be the same officer that had spoken of him in such disparaging terms at the ball, where, in the character of a young American gentleman, visiting the island for pleasure, he had been compelled inactively to listen to himself most mercilessly berated.

This, to a mind like Willis’s, was a wrong never to be forgotten. Born of a good family, though in straitened circumstances, well educated, and of naturally fine feelings, he had in his youth become dissipated, and the ardor of his temperament had for awhile forced him to great lengths in vice; but soon seeing the folly of his course, he determined entirely to reform his life and become a steady, industrious man; but when he informed his relations and friends of his resolution, and asked their countenance and assistance to reinstate him in his former position, he was met with sneers of incredulity, and unkindly told that as he had “sown to the wind, he might now reap the whirlwind.” Knowing himself to be possessed of talents, energy, and perseverance, his pride and self-love were keenly stung, and feeling perfectly disgusted with the want of charity, thus displayed by those who professed to be the “salt of the earth,” and believing them to be as wicked as himself, only gifted with more hypocrisy, and chagrined with all the world, he gave himself up entirely to the guidance of his passions.

But even now, associated as he was with the most desperate and abandoned, he could not always suppress a desire to return to that society he was born to adorn.

|

La Maraposa—The Butterfly. |

|

Buen vega a los infiernos—a good voyage to the lower regions. |

|

On board of armed vessels the trumpet is always carried by the officer in command of the deck. |

——

Gon. Beseech you, sir, be merry: You have cause

(So have we all) of joy; for our escape

Is much beyond our loss.—Tempest.

The deck of the Scorpion, the brig that had suffered so much in the late encounter, presented a scene of awful confusion; the masts and spars dragging over her sides; the cut shrouds and rigging; the loose blocks and splinters lumbering her deck, covered with blood, which, pouring through the scupper-holes, was dyeing the water with its crimson tide; the groans of the wounded; the bodies of the dead—fifty of her crew having been killed and crippled—bore testimony to the dreadful effects of the slaver’s fire.

Captain De Vere, the commander of the brig, whose inability to return effectually the schooner’s fire had rendered him nearly frantic, was excited to frenzy by the insulting bravado of Willis, when he hoisted his burgee, and covered with blood from a splinter-wound in his forehead, in a voice nearly inarticulate with passion, he was giving orders to cut away the shrouds attached to his floating spars, and urging his men to clear up the deck, as the sloop, crossing his bow, hailed —

“Brig, ahoy! What brig is that?”

“Her Britannic Majesty’s brig Scorpion. What ship is that?”

“Her Britannic Majesty’s sloop-of-war Vixen. How the deuce did you get in such a pickle?”

Captain De Vere was, with all his conceit, foppishness, and effeminate appearance, as brave as steel; and having publicly boasted of his intentions in regard to Willis’s vessel, it was with the greatest mortification, and breathing deep though inarticulate vows of vengeance against him if they ever met again, he informed his superior officer that he had been so cut up by the gun of the little schooner.

The Maraposa was still in sight; and De Vere desired the sloop to go in pursuit of her, and leave him to look out for himself; but the commander of the Vixen saw the brig stood so much in need of his assistance that he rounded-to, and backing his maintop-sail, sent his boats, with men, spars, and rigging, to assist in refitting the Scorpion.

By the strenuous exertions of both crews, the brig was all a-taunto by night; and having removed her wounded on board the sloop, both vessels made sail, under a press of canvas, in the direction the slaver had last been seen.

The look-outs were stimulated to increased vigilance, by the offer of a reward of five pounds to the one who should first discover the schooner; but they made land a little to the northward of the Ambriz River, without being able to see her. Determined to intercept the slaver as she returned, the two vessels separated, the sloop sailing to the northward, and the brig to the southward, intending to cruise up and down the coast until the schooner sailed.

Willis, in the meantime, had safely completed his passage, and when his pursuers made the land, was at anchor twenty miles up a river that makes into the ocean, a degree to the south’ard of St. Felipe de Benguela, busily engaged in taking aboard his cargo of four hundred negroes, that had been waiting at the Factory for him.

It would have afforded much food for a reflective mind, that African scene. At the first glance, all was beautiful; the bright and placid river gently rippling through the mangrove-bushes and tree-limbs, that overhung until they touched its surface; the tall and luxurious forest-trees that lined its banks, with an under-growth of flowering shrubs, and gay creeping vines, hanging from bough to bough in fantastical festoons, the branches alive with chattering monkeys, and lively, noisy parrots, and birds whose brilliant plumage, as they flew from perch to perch in the strong light, resembled gold and jewels; the graceful and fairy-like schooner, with the small boats going and returning; and the long, low factory, with its palm roof, just seen through the leaves on the summit of a hill, a little back from the stream, was beautiful—very beautiful.

But on a closer examination, in that bright river were to be seen myriads of hideous, greedy alligators. The luxurious trees afforded refuge for legions of troublesome insects, and noxious reptiles; in the flowering under-growth lurked deadly and venomous serpents; and most of the gay creeping plants were poisonous; the fairy-looking schooner was discovered to be a sink of moral infamy: the small boats were ladened with miserable captives; and even the partly seen Factory was a den of sin and suffering.

The natural and the artificial harmonized well—both charming, lovely, enticing, but equally corrupt, dangerous, and unwholesome.

In eight days the slaver’s living freight was all received on board. The day before, Willis had dispatched Mateo in a small boat to the mouth of the river, for the purpose of seeing if the coast was clear, and that no men-of-war were in sight; for nearly all the slavers that are captured, are caught just as they make out from the rivers, and before they have sea-room enough to enable them to use to advantage their superior sailing qualities.

The mate, on his return, reporting all safe, the schooner got under weigh, and after working down the river, put to sea with a fair wind, and every inch of canvas set that would draw, and steered for the Isle of Cuba—her cargo all being engaged to a negro trader at the eastern end of the island.

The external appearance of the Maraposa was unaltered, still as beautiful and attractive as when we saw her lying at anchor near Havana. But inboard, a great change had taken place; then, the tidy look of every thing, the quiet and careless expression visible on the countenances of her unarmed crew, gave rise to thoughts of peace and tranquillity; even the bright brass cannon seemed more for ornament than for dealing deathly execution. But now, every sailor had thrust in a belt encircling his waist, a brace of heavy pistols; keen cutlasses were ranged in racks around the masts, ready to be grasped in an instant; the long gun was pointed toward the tafferel, her gaping muzzle ready to be trained on either gangway; in the hold, seen through the main-hatchway, was a black, compact mass of human beings, crowded as close together as it was possible to get them, the light striking upon their constantly rolling eyes, made them appear spots of moving fire; groans, awful and horrible, the sounds of retching, and the incessant clanking of fetters, smote upon the ear. An odor the most nauseating and disgusting, (caused by the confinement of so many in a space so small,) filled the air, and would have overpowered the nerves of any but those accustomed to it; but upon the hardened crew, it had no more effect than upon the schooner, who, rushing through the water with the rapidity of a dolphin, sped on toward her port.

The Maraposa had succeeded in making an offing of about two hundred miles without seeing any thing, when the wind that had been steadily freshening for some time, increased so much that she was obliged to take in her lighter canvas; still increasing, she was compelled to furl all but her fore and aft sails, and had just made every thing snug as they discovered the Scorpion, with her yards braced up, and under close-reefed topsails, about five miles distant, and standing across their bows.

To keep the schooner on in the course she was running would bring her still nearer the brig; and Willis, thinking he might pass without being seen from the Englishman, put his helm a starboard, and brought his vessel by the wind, heading to the south’ard. The sail he carried, going free, was too much for the schooner close-hauled, and he was obliged to close-reef his fore-sail, balance-reef his main-sail, and take the bonnet off his jib, to keep the Maraposa from burying herself.

The look-outs on board the Scorpion were too alert, sharpened as their sights had been by the promised reward, to let the schooner pass unobserved, and in a few moments the brig was seen to ware ship, and shake a reef out of her topsails, and setting whole courses, the brig ploughing through the waves, now burying her bows in the huge billows, as if she were going to dive to the bottom of the ocean, and then rising on their summits until the bright copper was visible the whole length of her keel, seemed to spurn their support altogether, laboring and rolling heavily through the water, she breasted her way, and in consequence of the greater amount of canvas she was enabled to carry, gained on the Maraposa. Willis watched her for some time, hoping to see her courses, that were distended to their utmost, carried away; but the duck, strong, heavy, and new, did its part manfully, and finding his hope was groundless, he endeavored to make more sail upon the schooner.

“Shake the reefs out of the fore-sail.”

“Hoist away the halyards.”

Commands that were executed as soon as uttered. But hardly had the halyards been belayed ere, with a report like a cannon, the sail split, and flying from the bolt-ropes, sailed to leeward like a wreath of smoke. A new fore-sail was soon bent. The trifling delay gave the Scorpion another advantage, but the sea was so rough that neither vessel could make rapid headway, and it was not until an hour before sunset that the brig was within gun-shot of the schooner.

She at once opened upon her with the weather-bow gun, and the ball striking the slaver just forward the main-mast, crashed through her deck, and caused heart-rending and appalling shrieks and yells to ascend from the poor devils it wounded in her hold. Shot followed shot with rapidity from the Scorpion’s bow-guns; and occasionally yawing, she would let fly with her weather-broadside, losing distance, however, every time she put her wheel up.

Willis refrained from firing, fearful of diminishing the distance by broaching-too, and kept silently on his course until night, when he could no longer distinguish the brig, and could only make out her position by the flashes of her guns, he suddenly put up his helm, eased off his sheets, and standing off directly before the wind for a few moments, lowered away every thing, leaving nothing to be seen but the schooner’s two tall masts, which were not visible one hundred yards in the dusky light.

The schooner’s spars had luckily escaped all injury, though her deck and bulwarks were a good deal shattered, and several of her men, and a number of the negroes, who suffered from their compact position, had been killed. Willis was so rejoiced to find his masts safe that he did not mind the other damage, and waiting until the flash of a gun told him the brig had passed by, and was still pursuing the course he had been steering, without observing his dodge, he bore away before the wind with all the sail he could carry, and arrived at his destination without again seeing the Scorpion.

Captain De Vere stood on the same course all night, and was surprised in the morning to see nothing of the slaver: cursing the carelessness of his men, he catted all the look-outs, and stopped the grog of the whole crew. And savage at having been thus baffled, he shaped his course toward Havana; determined to capture Willis on his next voyage, if he had to carry all the masts out of his brig.

——

Did fortune guide,

Or rather destiny, our bark, to which

We could appoint no port, to this best place?

Fletcher.

Nearly the first visit Captain De Vere made, after his arrival at Havana, was to the family of Don Velasquez. The old Don found in the Englishman’s hauteur, fastidious notions of etiquette, and pride of family, a disposition so nearly similar to his own, that he soon became prepossessed in his favor.

Donna Clara, seeing nothing objectionable in the visiter, and knowing him to be wealthy, and of good birth, with that coquetry and love of conquest, so natural in the hearts of most of the fair sex, but all powerful in the breasts of beauties, exerted her uncommon powers of fascination with great success. In answer to an inquiry after Señorita Francisca, he found that her health had been declining for a month past, and her father had, at her earnest solicitation, permitted her to return to his country-seat, accompanied by an old and faithful duenna that had been with her since her infancy.

When Captain De Vere rose to depart, after spending a most agreeable hour, he was pressed, with more warmth than Don Manuel usually used in inviting guests to his house, to call often; this invitation he took advantage of, and was soon a daily visiter. Being thus frequently in the society of Clara, his thoughts were so usurped by her, that he nearly forgot his animosity to the captain of the schooner that had used his vessel so roughly, and then baulked him of his revenge.

Willis, after landing his negroes on the coast, where the agent of the planter who had purchased the cargo was ready to receive them, made for the nearest harbor, for the purpose of overhauling his vessel, and repairing more effectually than he had been able to do at sea, the damage occasioned by the Scorpion’s cannonade. It accidentally happened that he was only a few miles to the eastward of the bay, upon the margin of which Don Velasquez’s country-house was situated; and, standing-in, he came to anchor nearly abreast of the dwelling: it being the only residence visible, Willis determined to go on shore, and endeavor to obtain from the owner, or overseer, some fresh provisions, of which he stood in need.

Ordering the launch to follow, and bring off the things he expected to get, he pulled ashore in his gig, and landing on the beach, a few hundred yards from the house, he proceeded to the garden, which, extending nearly to the water’s edge, was beautifully laid out, and full of choice and exquisite flowers; he entered it, and walked up to the piazza without seeing any person. He thought it something unusual not to find any servants lounging about so fine a looking place; but just then observing a large gang of slaves, in a neighboring field, running, jumping, and moving about, as if they were amusing themselves, he expected it was a holyday, and was just going to make a noise that would attract the attention of the inmates, when a succession of sharp, shrill, ear-piercing shrieks rang through the air, evidently uttered by a female in deep distress.

Willis, gifted by nature with a heart keenly alive to the sufferings of woman, and judging from the peculiar agony of the tones he had heard, that some foul tragedy was in progress, rushed into the house, and hurrying to the room from which the noise proceeded, discovered lying on the floor, motionless, dead, or in a syncope, an elderly lady, dressed in black; and struggling violently in the grasp of two huge, swarthy, and half naked negroes, armed with machetas, or sugar-knives, a young girl, in robes of white, whom he instantly recognized as Francisca, and whose shrieks he had heard on the piazza.

The negroes were so engaged in trying to secure Francisca (for their aim did not seem to be murder) that they had not observed the entrance of Willis.

He at one glance understood the scene; drew a pistol from his breast and shot the nearest slave dead; catching his macheta from his hand as he fell, he clove with it the head of the other negro to the chin, and received Francisca fainting into his arms, but was compelled to lay her on the floor, and spring to the door, to repel the entrance of a dozen negroes, with large machetas, who, crowding the passage, were about to occupy the room.

Willis succeeded in getting to the door first, and as it was narrow, he for a short time was able to maintain his ground; the first four that presented themselves he sent to their long home, but their fellows, exasperated at the death of their comrades, and seeing it was but one man that opposed them, rallied for a rush, that must necessarily have proved fatal to Willis, with all his strength and courage, had not a diversion been made in his favor by the opportune arrival of his boat’s crew, who had heard the pistol shot, and hurried up to the house; seeing the game going on, with a loud shout, they attacked the blacks in the rear. For a moment the slaves gave back, but the gig’s crew, consisted of only four men, and they were armed with nothing but stretchers, boat-hooks, and their common short knives, and the negroes gaining a fresh accession to their numbers, were again on the point of being victorious, as the crew of the launch, which had been in sight when the gigsmen left their boat, came driving into the passage; they were sixteen of the most powerful men in the schooner’s complement, all armed with cutlasses, (twenty being constantly kept in a locker in the stern of the launch,) and falling on the negroes with the impetuosity of a whirlwind, they bore them down like chaff; and in two moments more the house was in possession of the whites.

As soon as Willis was free from the fray, he hastened back to the apartment in which he left Francisca and the old lady. The duenna had recovered her senses, and was anxiously employed in trying to reanimate Francisca, whose pale face, as it lay upon the dark dress of her attendant, was so corpse-like, that for a short time Willis was fearful that her ethereal spirit had fled.

Stooping down he impressed a gentle kiss on her cold forehead, and the vile slaver! the man who had been branded with the name of “brute!” breathed a fervent prayer to Heaven for the happy repose of her pure soul; to his great joy, however, he soon found that his fears were premature. A low sigh escaped Francisca; her bosom heaved, and after nervously twitching her eyelids a short time, she opened them, and gazed vacantly around the room, until her sight resting upon Willis, she recovered her faculties, and, with a blush suffusing her cheek, she tried to thank him; but the effort was too great, and she again swooned away. By the use of stimulants, she was perfectly restored in the course of half an hour, and, had Willis permitted it, would have overwhelmed him with expressions of gratitude.

But he did not think the danger was over yet; and, informing them of it, invited them to accompany him on board the Maraposa, until he had been able to land a party, and see that all was quiet. The duenna was clamorous to go, and soon overpowered the weak objections of Francisca, who was in reality desirous of going, but was uneasy lest Willis might think it unmaidenly.

With all courtesy, and every soothing, gentlemanly attention, Willis accompanied them on board the schooner; and leaving them in possession of his cabin, and under the protection of Mateo, he armed a large part of his crew, and went with them on shore, to inquire into the cause of the insurrection, and make an effort to suppress it.

In the sugar-house he found the overseer of the plantation, bound hand and foot, and gagged with his own whip. Freeing him from his painful situation, Willis found that the insurrection had not been general, but was confined, as yet, to the plantation of Don Manuel; whose negroes, being all under the influence of an old Obeah man on the place, had by him been excited to rise, to take revenge on the whites for a severe whipping the overseer had been forced to give him a few days before; and the overseer said the only reason they spared his life was because the Obi man wanted to have a grand Feteesh that evening, and offer him up as a sacrifice.

The active measures taken by Willis, who was accustomed to deal with refractory negroes, soon restored order on the plantation; and leaving every thing quiet, he returned to his vessel.

Reporting the state of affairs on shore, he told the ladies he was going directly to Havana, and would be most happy to give them a passage, if they felt any timidity in reoccupying their mansion. Francisca professed to feel no uneasiness, as she now understood the cause of the outbreak; and said that the negroes had been so severely punished for this attempt, that they would be afraid to make another, particularly as the ringleaders had been killed, and was for at once going back to the house.

But this arrangement met with violent opposition from the duenna, who would not even listen to any such proposition. Ductile, and ready to be guided by her slightest wish, Francisca had always found the old lady to be heretofore, and in exact proportion was she now obstinate. Talking was thrown away upon her. She said it would be actually tempting Providence for them to return! That Don Manuel would never forgive her if she let Francisca neglect this opportunity of returning to him, while she was safe; and, finally, sullenly refused to leave the schooner until Francisca would promise to go in it to Havana.

Francisca, truly, did not feel perfectly secure in remaining at the house, and would have preferred going back to her father, had the vessel been commanded by any one but Willis; but knowing well her ardent love for him, now increased by gratitude for her recent delivery, she was fearful that in the constant and close communion that would be necessarily created by their being together, in a small vessel, for several days, she would be unable entirely to suppress all evidences of it; and as he had never yet given her any assurance that her affection was reciprocated, her pride and delicacy revolted at the thought of his discovering the state of her heart.

But she found that she had no choice; for the old lady’s fears had been so vividly excited, by the events of the day, that persuasion had no effect upon her; and Francisca, not wishing to remain at the plantation alone, reluctantly consented to take passage in the Maraposa.

As soon as the promise had been extorted, the duenna was as anxious to get ashore, for the purpose of preparing for their departure, as if she had been getting ready for her wedding; and Willis sent them home, accompanied by a number of his men, armed, and under the charge of his mate, whom he ordered to remain at the house and keep a vigilant watch until the ladies were ready to depart.

Francisca, wishing to defer the hour of departure as long as possible, made no effort to hurry the operations of her attendant, whose fears being relieved by the presence of the guard, found so many things she wanted to arrange and take with them, that the third day arrived ere she reported everything ready to start.

So inconsistent are the feelings of woman, that Francisca, who for several months had thought of naught but Willis, and looked forward to the time when she again might meet him as the dearest boon of her life, now that an opportunity offered of being constantly with him for several days, without over-stepping the bounds of propriety, hung back with dread; yet in the bottom of her heart she was glad that no excuse offered for her longer postponing the step.

Willis, who had called personally upon them but once since the day of the insurrection, pleading his duties as the cause of his absence, when he learned they were ready to start, came in his gig to take them off to the schooner.

The Maraposa’s appearance had been much altered since she came into the bay; advantage had been taken of the three days to repair all the damage that had been caused by the Scorpion, and, in honor of the fair passenger she was about to receive, instead of the coat of black with which she had been covered, she was now painted pure white, with a narrow ribbon of gold around her, and the Portuguese flag was flying from her main-gaff.

So charmed was Francisca with the beautiful appearance of the vessel, that it nearly overcame her repugnance to going on board; and the behavior of Willis, who, though perfectly courteous and kind in his manner, was reserved, dissipated the remainder of her scruples; and it was with feelings of pleasure at being near him, and able to hear his voice and see him, and with a presentiment that her love would not always be unrequited, that she stepped upon the deck.

The distance from Havana was only about three hundred and fifty miles, but a succession of light airs and calms prevailing, it was five days before the schooner accomplished the passage.

During these five days, many and various were the emotions that agitated the breast of Francisca; now she was all joy, from the pleasure afforded her by Willis’s presence, then a sickening anxiety would overcome her joy, for fear her love would never be returned, when some word, look, or tone of Willis would make her imagine that he did love her; and for a little while she would be perfectly contented, until the thought of their speedy separation, and the fear that Willis might not confess his feelings, with the uncertainty of their again meeting, would cast a heavy cloud over her spirits; and when they passed the Moro Castle, on entering the harbor, she could not determine whether she had been very happy or very miserable for the last few days.

Francisca had addressed Willis by the name of “Brewster,” the name by which he had been introduced to her at the ball; and as he did not inform her to the contrary, she had no reason to believe that it was not his proper appellation. She had some curiosity to know why he was in command of an armed vessel, but he did not mention the subject, and delicacy prevented her asking him.

The duenna was restrained by no such scruples; and having become intimate with Mateo, endeavored by all manner of inquiries to get at the history of his captain, for she had some suspicion of the state of her young charge’s feelings; the mate, however, was afflicted with a spell of taciturnity whenever she commenced about the captain, though upon all other subjects he was very communicative; and all the good dame was able to learn from him was, that the schooner was a Portuguese man-of-war, and that the captain was a young American, high in the confidence of the government, who had been sent out to the West Indies on a special mission of some kind, he did not know what!

This account would have been likely to excite the doubts of one conversant with maritime affairs, but with Francisca and the duenna, it passed current, without a suspicion of its falsity.

Willis’s mind, during this short passage, had been likewise subject to many struggles; when he first saw Francisca, his knowledge of the sex had enabled him to form a correct opinion of her character, though he had sought her out at the governor’s, with no other intention than that of passing an agreeable evening. The respect with which she had inspired him, involuntarily compelled a softer tone in his voice, and more point and feeling to his conversation than he had intended.

His course of life had, for several years, excluded him from any very intimate intercourse with the refined and virtuous of the other sex; and to be thus brought in close conjunction with one eminently lovely, and whom he knew to be intelligent, gentle, and pure, gave a direction to his thoughts, and cast a shade of happiness over his feelings, that had been foreign to them for a long time; and knowing from the expression of Francisca’s eye, and an indescribable something in her manner, that she entertained partial feelings toward him, he could not help loving her, and pictured to himself the happiness with which he could spend the balance of his life with such a companion; with eagerness would he have sought her affection, had he occupied that station in life he knew he was entitled to.

But the dark thought of his present position obtruded itself. He was a slaver—an outlaw! and in the estimation of many in the world, worse than a pirate. His sense of honor revolted at the idea of taking advantage of the ignorance and confidence of an inexperienced girl, and inducing her to share his lot, even if he could have succeeded.

He therefore treated Francisca with scrupulous politeness during the passage; and desirous of removing the temptation from him, while yet he had strength to resist, landed the ladies as soon as permits were received from the authorities, and accompanying them to Don Manuel’s door, bid them farewell, without going in. Both Francisca and the duenna were very urgent for him to enter, if only for a moment, that Don Velasquez might have an opportunity of expressing his gratitude.

The sudden return of Francisca greatly surprised her father and sister, who, after the first embrace, overwhelmed her with questions. She related all the particulars of the insurrection—her danger, and the great obligations she was under to the captain of the schooner in which she had come home; and her father was nearly angry at her for not compelling her preserver to come in with her, that he might have given him some evidence of his appreciation of the deep obligation he had laid him under; and he hurried off to find Willis, and tell him his feelings of gratitude, and endeavor to find some means of requiting him.

He readily found the Maraposa, but Willis had not yet returned on board; and Don Velasquez waited until dinner time without his making his appearance. Disappointed, he returned home, leaving with the mate a note, earnestly requesting “Captain Brewster” to call upon him.

After Willis had parted with Francisca, he found the loss of her society a greater denial, and more difficult to bear than he had imagined; and with his mind much troubled, he proceeded to a monte-room, to allay the distress of his feelings by the excitement of play. He staked high, but the luck was against him; and in a few hours all the drafts he had received from the purchasers of his last cargo passed from his pocket to the hands of the monte bank-keeper. This loss at any other time would not have disturbed him, for he made money too easy to place much value upon it; but now it caused him to feel as if every thing was against him, and in a state of mind ready to quarrel with the world, and all that was in it, he walked into the saloon attached to the monte-room, which was the fashionable lounging place of the city.

Seating himself at one of the tables, he ordered some refreshments, and was discussing them, when Captain De Vere, accompanied by two other gentlemen, entered, and placing themselves at an adjoining table, continued the conversation they had been engaged in before their entry.

Willis’s back being toward them, he would not have seen De Vere, had not his attention been attracted by hearing the name of the Maraposa mentioned; when turning around, he discovered the English Captain. His first impulse was to get up, and by insulting De Vere, compel him to give satisfaction for the contumely he had heaped upon his name the night of the ball; but remembering his person was unknown to the Englishman, he thought he would first learn the subject of their conversation.

“You only feel sore, De Vere, because the slaver dismasted you, and then played you such a slippery trick when you thought you were sure of her. By the Virgin! I would like to have seen you getting cut to pieces by a little schooner, and you unable to return a shot. Faith, I don’t blame you for hating the fellow so,” said one of De Vere’s friends.

“Hate him! yes, I would give a thousand pounds to have him on the beach alone for half an hour. Every midshipman in port laughs at the Scorpion, and says her sting was extracted by a musqueto; but, by heavens! if I can’t get a fight out of the captain, I will have the schooner as soon as she gets past the Moro.”[6]

Willis, who desired a personal encounter as much as De Vere, waited until he had finished, and stepping up to the group, bowed to the captain, and told him he had the honor of being Charles Willis, master of the schooner Maraposa; and that he would be happy to accommodate him with his company as soon as it would suit his convenience.

This sudden and unexpected movement startled De Vere and his friends; but the Englishman soon recovered his composure, and struck by the appearance of Willis, in whom, to his surprise, he discovered a gentleman of refined manners, when he expected to meet a rough, rude sailor, returned his salute, and said “That the next morning at sunrise he would meet him on the sea-shore, six miles above the city, accompanied by a friend; and if Mr. Willis had no objection, the weapons should be pistols.”

Willis replied “that it was a matter of indifference to him, and if he preferred pistols, he was perfectly satisfied;” and with a bow he wished them good afternoon, and left the saloon.

After Willis’s departure, De Vere’s friends commenced joking him upon his success, in having so soon been able to get an opportunity of revenging himself upon the dismantler of his brig.

But on the eve of a deadly encounter with a determined antagonist, a man, no matter how brave, does not feel like jesting; and after engaging the services of one of the gentlemen for the morrow, looking at his watch, De Vere suddenly remembered a pressing engagement, and bidding his companions adieu, he went to Don Manuel’s to spend another evening, perhaps his last, with Señorita Clara, to whom he was now engaged to be married.

Willis, after leaving the café, proceeded to the office of his agent, where business matters detained him until nearly dark. Attracted by the appearance of a splendid equipage that came driving from the other end of the street as he was about starting for his vessel, he looked to see if he knew the inmates, and discovered Francisca and her father sitting on the back seat. He would have gone on without speaking, but the recognition had been mutual; and the vehicle instantly stopping, Don Manuel got out, and approaching Willis with dignity and great kindness mingled in his manner, and deep feeling in his words, thanked him for his assistance and gallantry to his daughter; and begged Willis to point out some substantial method by which he could prove his gratitude, and told him he had waited all the morning on board the schooner to see him.

The captain of the Maraposa replied, that the pleasure of being able to do any thing to increase the safety or happiness of a lady, amply repaid the trouble; and that he considered all the obligation on his side, for he had by that means enjoyed for several days the society of his daughter.

“Your actions don’t tally with your words, señor capitan, or you would have come in this morning, and not have kept me so long from thanking you. But you must go with us now; no excuse will avail, for we will not take any—will we Francisca?”

“No, no! but el señor will certainly not refuse.” The look that accompanied her words had more influence on Willis than all the old gentleman had said; and getting into the carriage, they drove to Don Velasquez’s house.

Entering the drawing-room, they found Clara and Captain De Vere, to whom Don Manuel introduced Willis as “Captain Brewster,” of the Portuguese navy; the gentleman who had rendered such distinguished service to Francisca.

Clara received him with much kindness; but De Vere’s inclination was as cold and haughty as if he had been made of ice.

During the evening the family treated him with the greatest attention and consideration, and seemed hurt at De Vere’s reserve. But Willis, certain that his true character would soon be known, and feeling that he was deceiving them, though he had been forced into his present situation against his inclination, retired as soon after supper as politeness would allow, and promised Don Manuel to make his house his home, with the intention of never coming near it again.

|

It is necessary for the condemnation of a slaver, to capture her when she has either negroes on board, or slave-irons and extra water-casks. These they always disembark before they come into port, and do not take on board until they are ready to sail. |

[To be continued.

———

BY KATE DASHWOOD.

———

“I had a dream, and ’twas not all a dream.”

Dear cousin mine, last eve I had a vision —

Nay, do not start!

There softly stole into the bright Elysian

Of my young heart —

A glowing dream, like white-winged spirit stealing

Amid the shadows of my soul’s revealing.

The sunset clouds were fading, and the light,

Rosy and dim,

Fell on the glorious page where wildly bright

“The Switzer’s Hymn”

Of exile, and of home, breathed forth its soul of song —

Waking my heart’s hushed chords, erst slumbering long.

Then that sad farewell-hymn seemed floating on,

Like wild, sweet strain

Of spirit-music o’er the waters borne —

Bringing again

Fond memories, and dreams of many a kindred heart,

Dim cloistered in my bosom’s shrine apart.

And then came visions of my own bright home —

The happy band

Far distant—who at eventide oft come,

Linked hand in hand —

When to my quickened fancy love hath lent

Each thrilling tone, and each fond lineament.

They come again—the young, the beautiful —

The maiden mild,

The matron meek—whose soft low prayer doth lull

Her sleeping child;

The proud and fearless youth, with soul of fire!

Who guides his trembling steps—yon gray-haired sire.

And then came thronging all earth’s gentle spirits —

That minister

Like angels to our hearts—thus they inherit

From Heaven afar —

Their blessed faith of Truth, and love for aye,

Which scatters sunbeams on our darksome way.

My vision changed—those messengers of light,

To fays had turned,

Then trooped they o’er our fairy-land, when night

Her star-lamps burned;

They peeped in buds and flowers, with much suspicion,

For all deep-hidden sweets—for ’twas their mission.

And then they scattered far and wide, and sought

The thorny ways,

And toilsome paths, to strew with garlands wrought —

The cunning fays! —

From all the brightest and the fairest flowers

They culled by stealth from Flora’s glowing bowers.

And some were thoughtful, and removed the thorns —

Because, perchance,

Some traveler, wandering ere the morning dawns,

Might rashly dance

Thereon with his worn sandals; others planted

Bright flowers instead, at which they were enchanted.

And some were roguish fays—right merry elves,

Who loved a jest,

And ofttimes stole away “all by themselves,”

Within some rose’s breast,

And there employed their most unwearied powers

In throwing “incense on the winged hours.”

What ho! the morning dawns! the orient beams

With glory bright,

Lo! flee the fairies with the first young gleams

Of rosy light;

But fadeth not that vision from my soul,

Where its soft teachings e’er shall hold control.

And blest, like thine, is every gentle spirit

That ministers

Like angels to our hearts! such shall inherit,

From Heaven afar,

That pure and radiant light, whose holy rays

E’er bathe in sunlight earth’s dark, toilsome ways.

———

BY ALFRED B. STREET.

———