MONUMENT TO JUNÍPERO SERRA IN GOLDEN GATE PARK.

“His memory still rests like a benediction over the noble State which he rescued from savagery.”

Title: Spanish and Indian place names of California: Their Meaning and Their Romance

Author: Nellie Van de Grift Sanchez

Release date: April 11, 2019 [eBook #59251]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Bryan Ness and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

MONUMENT TO JUNÍPERO SERRA IN GOLDEN GATE PARK.

“His memory still rests like a benediction over the noble State which he rescued from savagery.”

THEIR MEANING AND THEIR ROMANCE

BY

NELLIE VAN DE GRIFT SANCHEZ

A. M. ROBERTSON

SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA

MDCCCCXIV

COPYRIGHT, 1914

BY

A. M. ROBERTSON

TO MY SON

The author wishes to express grateful appreciation of generous aid given in the preparation of this book by Herbert E. Bolton, Ph.D., Professor of American History in the University of California.

Acknowledgment is also due to Dr. A. L. Kroeber, Assistant Professor of Anthropology, Dr. Harvey M. Hall, Assistant Professor of Economic Botany, Dr. John C. Merriam, Professor of Palaeontology, Dr. Andrew C. Lawson, Professor of Geology and Mineralogy, all of the University of California; Mr. John Muir, Father Zephyrin Engelhardt, O.F.M., Mr. Charles B. Turrill, of San Francisco, and many other persons in various parts of the state for their courtesy in furnishing points of information.

For the sources used in the work, the author is indebted, in great measure, to the Bancroft Library at the University of California, and to the many writers from whose works quotations have been freely used.

“NONE CAN CARE FOR LITERATURE IN ITSELF WHO DOES NOT TAKE A SPECIAL PLEASURE IN THE SOUND OF NAMES; AND THERE IS NO PART OF THE WORLD WHERE NOMENCLATURE IS SO RICH, POETICAL, HUMOROUS, AND PICTURESQUE AS THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.... THE NAMES OF THE STATES AND TERRITORIES THEMSELVES FORM A CHORUS OF SWEET AND MOST ROMANTIC VOCABLES; ... THERE ARE FEW POEMS WITH A NOBLER MUSIC FOR THE EAR; A SONGFUL, TUNEFUL LAND; AND IF THE NEW HOMER SHALL ARISE FROM THE WESTERN CONTINENT, HIS VERSE WILL BE ENRICHED, HIS PAGES SING SPONTANEOUSLY, WITH THE NAMES OF STATES AND CITIES THAT WOULD STRIKE THE FANCY IN A BUSINESS CIRCULAR.”

ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON.

| Page | |

| CHAPTER I | |

| Introduction | 3 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| California | 13 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| In and About San Diego | 21 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Los Ángeles and her Neighbors | 51 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| In the Vicinity of Santa Bárbara | 89 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| The San Luís Obispo Group | 117 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| In the Neighborhood of Monterey | 133 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| The Santa Clara Valley | 167 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| Around San Francisco Bay | 185 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| North of San Francisco | 241 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| The Central Valley | 265 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| In the Sierras | 235 |

| Pronunciation of Spanish Names | 335 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| Final List and Index | 347-444 |

| Addenda | 445 |

| Page | |

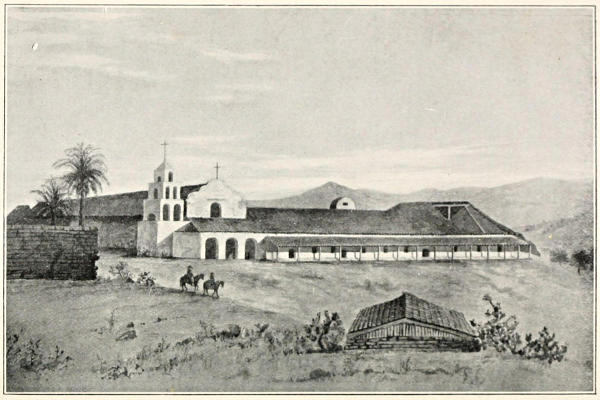

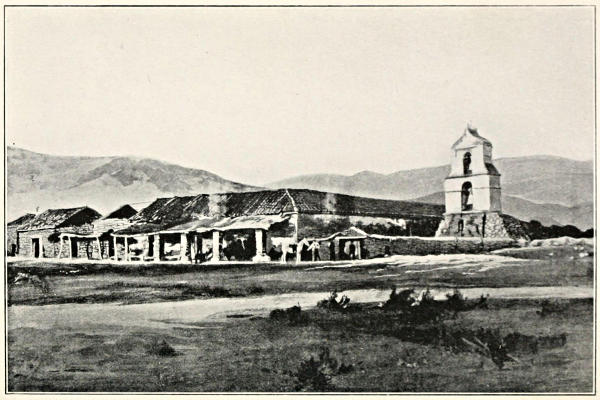

| Mission of San Diego de Alcalá, Founded in 1769 | 23 |

| Mission of San Antonio de Pala, Founded in 1816 | 31 |

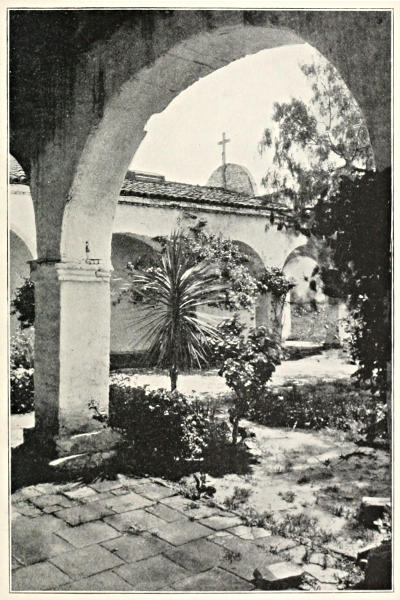

| Archway at Capistrano | 37 |

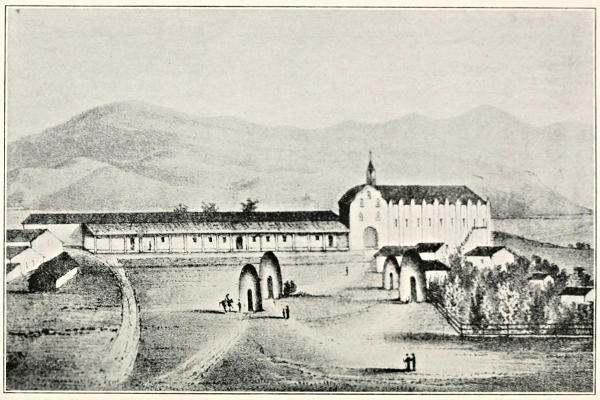

| Mission of San Gabriel Arcángel, Founded in 1771 | 67 |

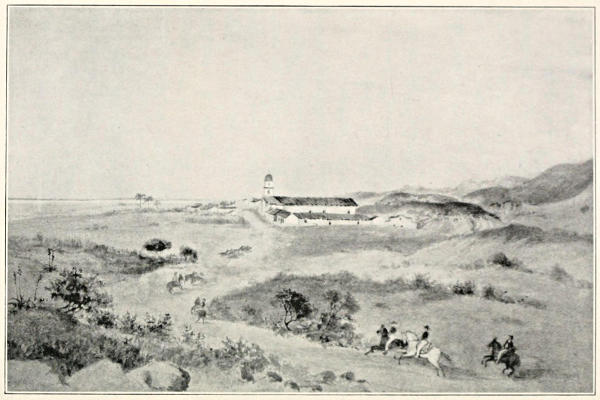

| Mission of Santa Bárbara | 91 |

| Mission of Santa Inez, Founded in 1804 | 111 |

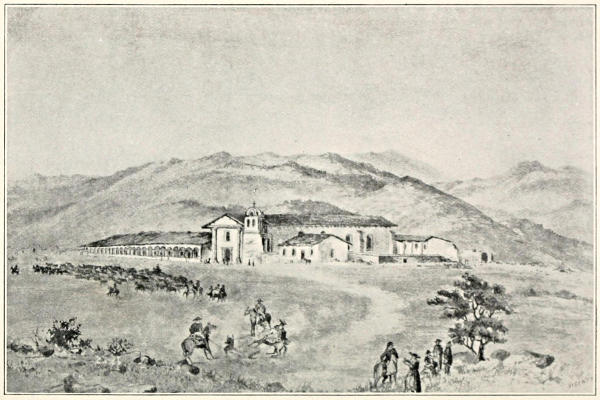

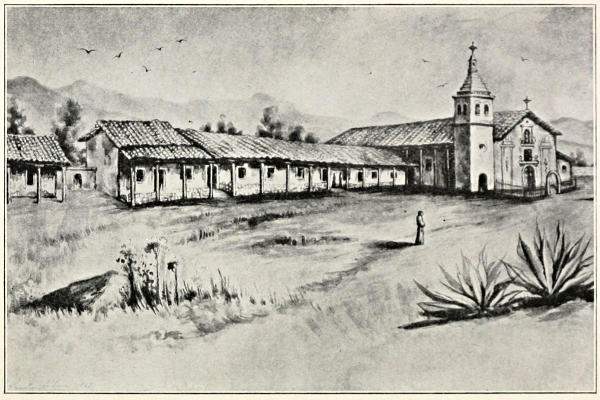

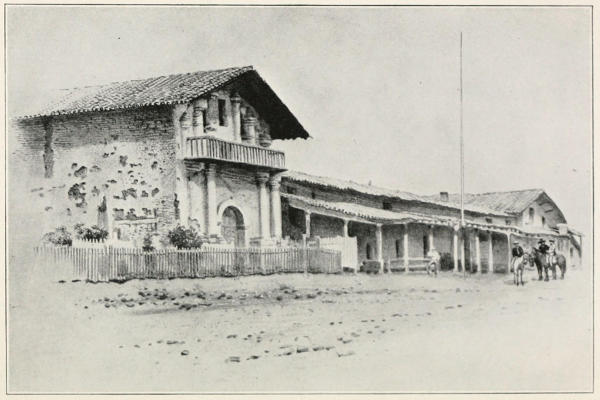

| Mission of San Luís Obispo, Founded in 1772 | 119 |

| Mission of San Miguel, Founded in 1797 | 125 |

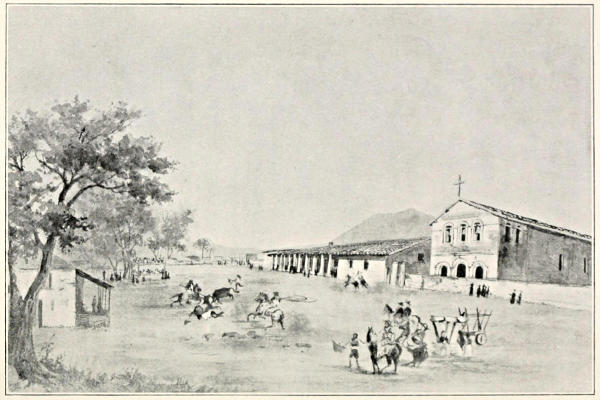

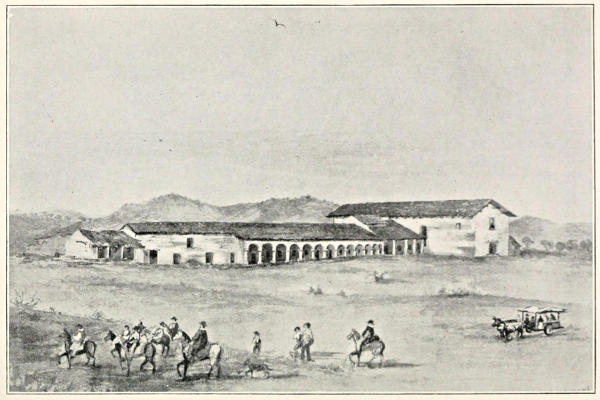

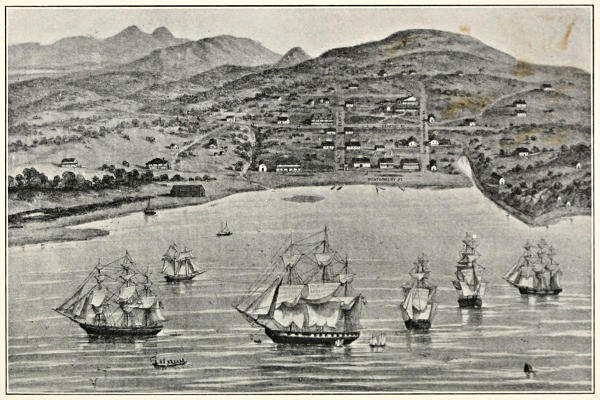

| Monterey in 1850 | 135 |

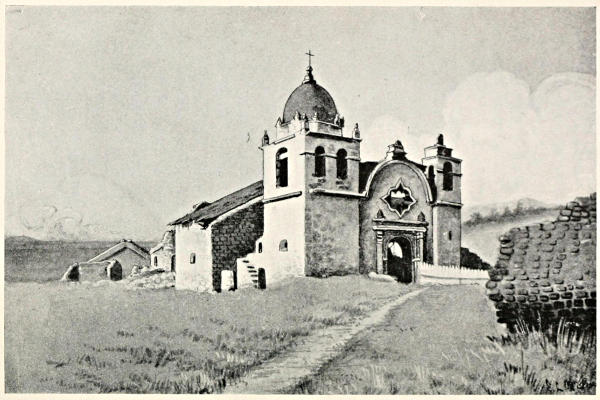

| Mission of San Carlos Borroméo, Founded in 1770 | 139 |

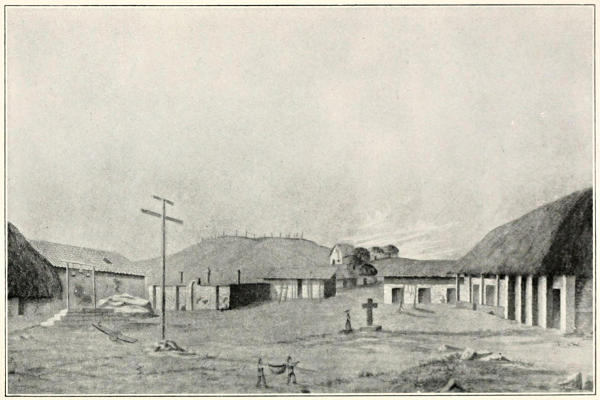

| Interior of the Quadrangle at San Carlos Mission | 143 |

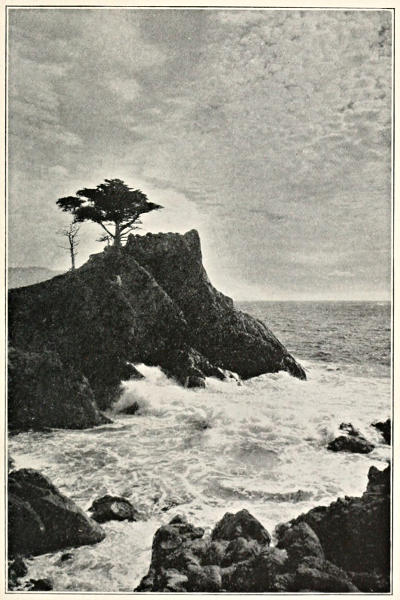

| La Punta de los Cipreses | 149 |

| Mission of San Juan Bautista, Founded in 1797 | 155 |

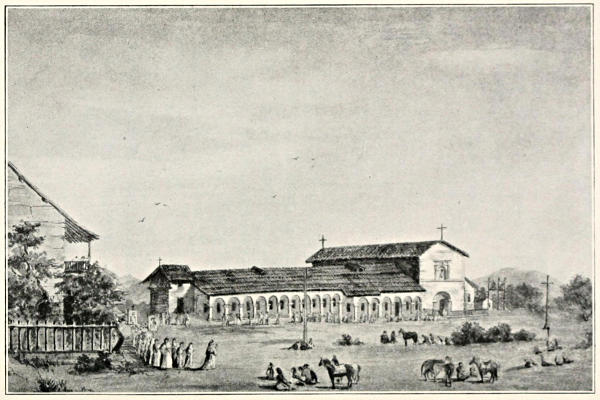

| Mission of Santa Clara, Founded in 1777 | 169 |

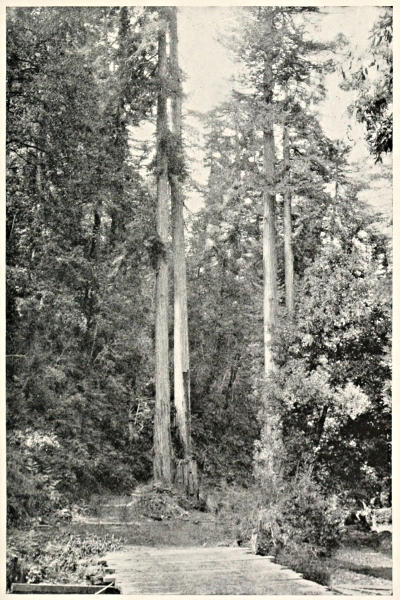

| The Palo Colorado (Redwood Tree) | 175 |

| The City of Yerba Buena (San Francisco in 1846-47) | 187 |

| Mission of San Francisco de Asís, commonly called Mission Dolores | 195 |

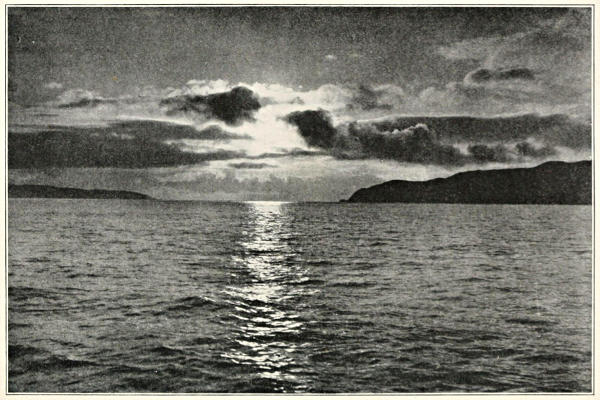

| The Golden Gate | 201 |

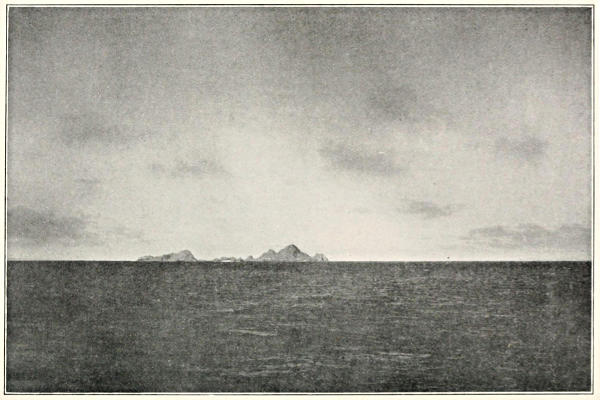

| The Farallones | 209 |

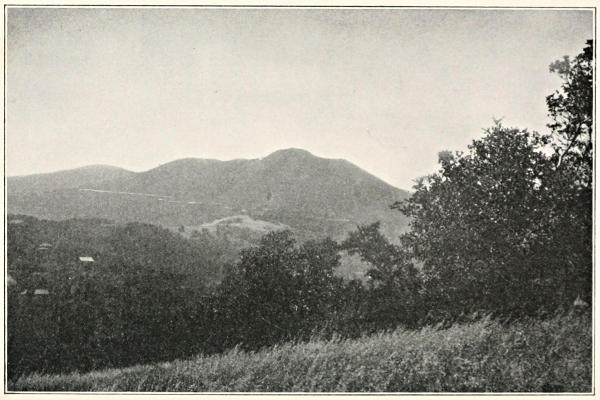

| Tamalpais | 215 |

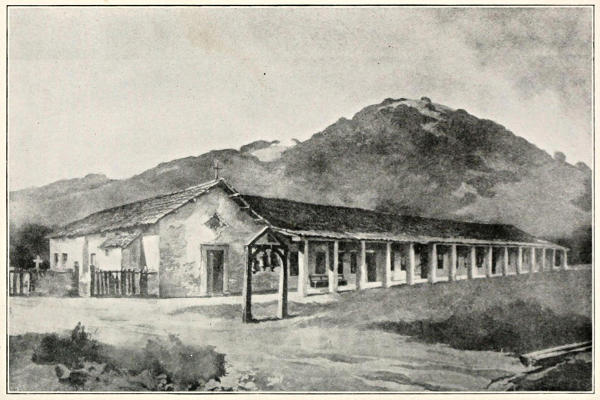

| The Mission of San Rafael, Founded in 1817 | 221 |

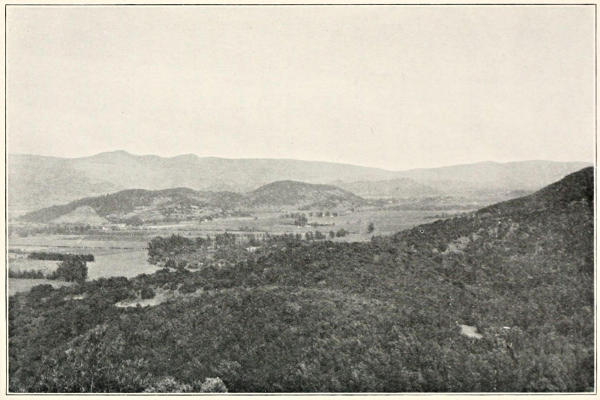

| Napa Valley | 243 |

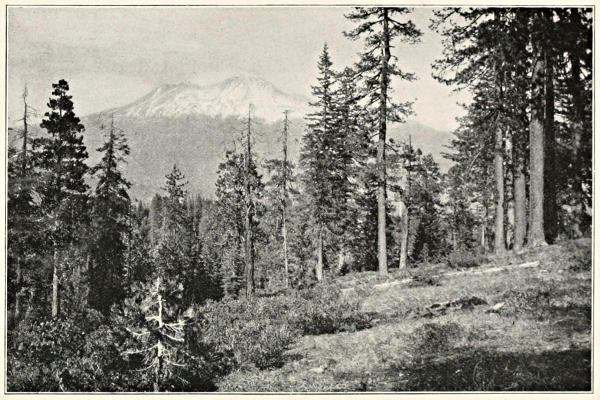

| Mount Shasta | 253 |

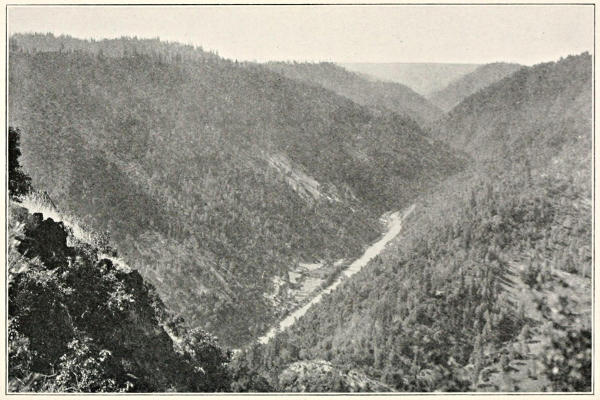

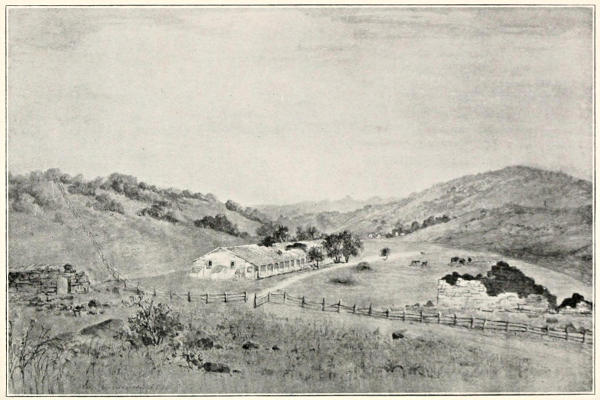

| El Río de los Santos Reyes (The River of the Holy Kings) | 279 |

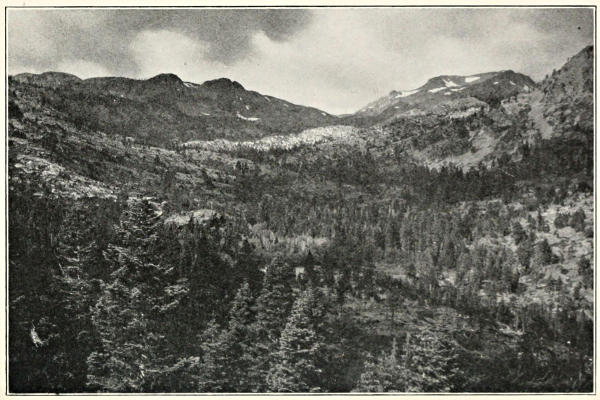

| In the Sierra Nevadas | 284 |

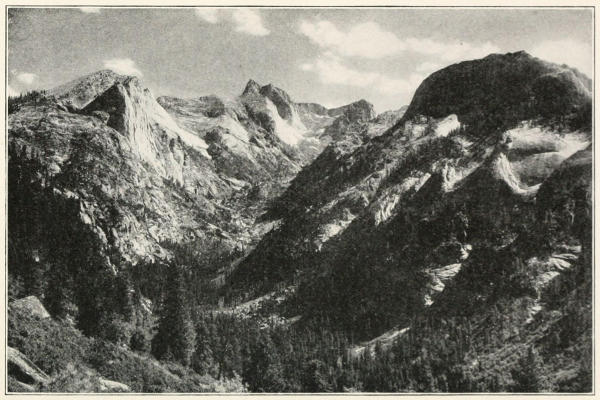

| In the High Sierras | 295 |

| El Río de las Plumas (Feather River) | 301 |

| El Río de los Americanos (American River) | 307 |

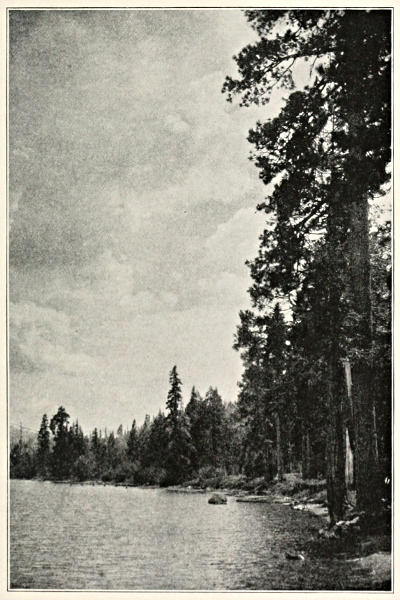

| Shore of Lake Tahoe | 313 |

| Mariposa Sequoias | 319 |

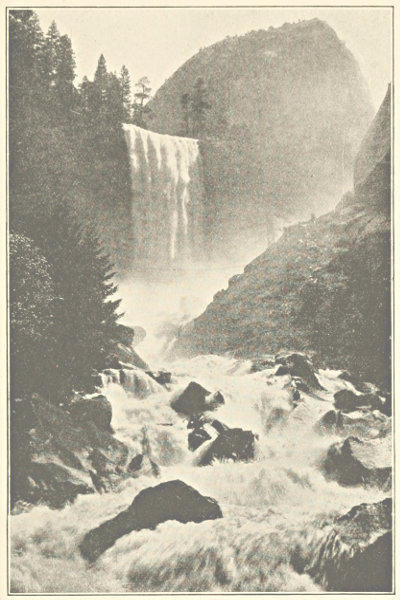

| Vernal Falls in the Yosemite Valley | 325 |

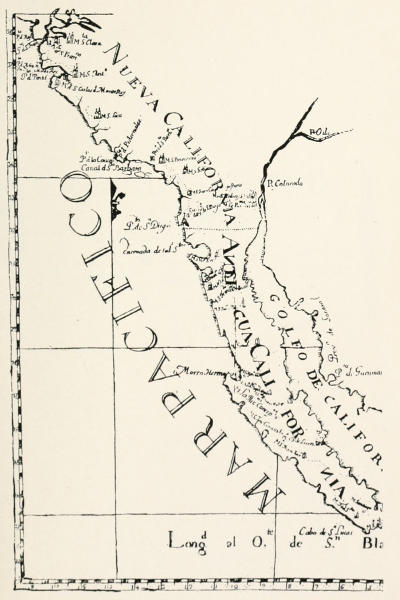

| Map of the Missions | 343 |

| Kaweah Mountains | 383 |

| The Mission of Purísima Concepción, Founded in 1880 | 409 |

| The Tallac Trail to Tahoe | 437 |

This volume has been prepared in the hope that it may serve, not only as a source of entertainment to our own people, but also as a useful handbook for the schools, and as a sort of tourist’s guide for those who visit the state in such numbers, and who almost invariably exhibit a lively interest in our Spanish and Indian place names.

We of California are doubly rich in the matter of names, since, in addition to the Indian nomenclature common to all the states, we possess the splendid heritage left us by those bold adventurers from Castile who first set foot upon our shores. In these names the spirit of our romantic past still lives and breathes, and their sound is like an echo coming down the years to tell of that other day when the savage built his bee-hive huts on the river-banks, and the Spanish caballero jingled his spurs along the Camino Real.

And in what manner, it may well be asked, have we been caring for this priceless heritage,—to keep it pure, to preserve its inspiring history, to present it in proper and authentic form for the instruction and entertainment of “the stranger within our gates,” as well as for the education of our own youth? As the most convincing answer to this question, some of the numerous errors in works purporting to deal with this subject, many of which have even crept into histories and books for the use of schools, will be corrected in these pages.

In the belief that the Spanish and Indian names possess the greatest interest for the public, both “tenderfoot” and native, they will be dealt with here almost exclusively, excepting a very few of American origin, whose stories are so involved with the others that they can scarcely be omitted. In addition, there are a number that appear to be of Anglo-Saxon parentage, but are in reality to be counted among those that have suffered the regrettable fate of translation into English from the original Spanish. Of such are Kings County and River, which took their names from El Río de los Santos Reyes (the River of the Holy[5] Kings), and the Feather River, originally El Río de las Plumas (the River of the Feathers).

While searching for the beginnings of these names through the diaries of the early Spanish explorers and other sources, a number of curious stories have been encountered, which are shared with the reader in the belief that he will be glad to know something of the romance lying behind the nomenclature of our “songful, tuneful” land.

It is a matter of deep regret that the work must of necessity be incomplete, the sources of information being so scattered, and so often unreliable, that it has been found impossible to trace all the names to their origin.

Indian words are especially difficult; in fact, as soon as we enter that field we step into the misty land of legend, where all becomes doubt and uncertainty. That such should be the case is inevitable. Scientific study of the native Californian languages, of which there were so many as to constitute a veritable Babel of tongues among the multitude of small tribes inhabiting this region, was begun in such recent times that but few aborigines were left to tell the story of their names, and those few retained but a dim memory of the[6] old days. In view of the unsatisfactory nature of this information, stories of Indian origin will be told here with the express qualification that their authenticity is not vouched for, except in cases based upon scientific evidence. Some of the most romantic among them, when put to the “acid test” of such investigation, melt into thin air. In a general way, it may be said that Indian names were usually derived from villages, rather than tribes, and that, in most cases, their meaning has been lost.

In the case of Spanish names, we have a rich mine in the documents left behind by the methodical Spaniards, who maintained the praiseworthy custom of keeping minute accounts of their travels and all circumstances connected therewith. From these sources the true stories of the origin of some of our place names have been collected, and are retold in these pages, as far as possible, in the language of their founders. Unfortunately, the story can not always be run to earth, and in such cases, the names, with their translation, and sometimes an explanatory paragraph, will appear in a supplementary list at the end of the volume. The stories have been arranged in a series of[7] groups, according to their geographical location, beginning with San Diego as the most logical point, since it was there that the first mission was established by the illustrious Junípero Serra, and there that the history of California practically began. The arrangement of these groups is not arbitrary, but, in a general way, follows the course of Spanish Empire, as it took its way, first up the coast, then branching out into the interior valley, and climbing the Sierras.

Some of the stories may appear as “twice-told tales” to scholars and other persons to whom they have long been familiar, but are included here for the benefit of the stranger and the many “native sons” who have had no opportunity to become acquainted with them.

A few words in regard to the method of naming places customary among the Spanish explorers may help the reader to a better understanding of results. The military and religious members of the parties were naturally influenced by opposite ideas, and so they went at it in two different ways. The padres, as a matter of course, almost invariably chose names of a religious character, very often the name of the saint upon whose “day”[8] the party happened to arrive at a given spot. This tendency resulted in the multitude of Sans and Santas with which the map of our state is so generously sprinkled, and which are the cause of a certain monotony. Fortunately for variety’s sake, the soldiers possessed more imagination, if less religion, than the padres, and were generally influenced by some striking circumstance, perhaps trivial or humorous, but always characteristic, and often picturesque. In many cases the choice of the soldiers has out-lived that of the fathers.

Broadly speaking, it may be said that names were first applied to rivers, creeks or mountains, as being those natural features of the country most important to the welfare, or even the very existence, of the exploring parties. For instance, the Merced (Mercy), River was so-called because it was the first drinking water encountered by the party after having traversed forty miles of the hot, dry valley. Then, as time passed and the country developed, towns were built upon the banks of these streams, frequently receiving the same names, and these were often finally adopted to designate the counties established later in the[9] regions through which their waters flow. In this way Plumas County derived its name from the Feather River, originally El Río de las Plumas, and Kings County from El Río de los Reyes (the River of the Kings). This way of naming was, however, not invariable.

It sometimes happens that the name has disappeared from the map, while the story remains, and some such stories will be told, partly for their own interest, and partly for the light they throw upon a past age.

Among our Spanish names there is a certain class given to places in modern times by Americans in a praiseworthy attempt to preserve the romantic flavor of the old days. Unfortunately, an insufficient knowledge of the syntax and etymology of the Spanish language has resulted in some improper combinations. Such names, for instance, as Monte Vista (Mountain or Forest View), Loma Vista (Hill View), Río Vista (River View), etc., grate upon the ears of a Spaniard, who would never combine two nouns in this way. The correct forms for these names would be Vista del Monte (View of the Mountain), Vista de la Loma (View of the Hill), Vista del Río (View[10] of the River), etc. Between this class of modern Spanish names, more or less faulty in construction, given by “Spaniards from Kansas,” as has been humorously said, and the real old names of the Spanish epoch about which a genuine halo of romance still clings, there is an immense gulf.

In the numerous quotations used in this book, the language of the original has generally been retained, with no attempt to change the form of expression. In spite of the most conscientious efforts to avoid them, unreliability of sources may cause some errors to find their way into these pages; for these the author hopes not to be held responsible.

First comes the name of California herself, the sin par (peerless one), as Don Quixote says of his Dulcinea. This name, strange to say, was a matter of confusion and conjecture for many years, until, in 1862, Edward Everett Hale accidentally hit upon the explanation since accepted by historians.

Several theories, all more or less fanciful and far-fetched, were based upon the supposed construction of the word from the Latin calida fornax (hot oven), in reference either to the hot, dry climate of Lower California, or to the “sweathouses” in use among the Indians. Such theories not only presuppose a knowledge of Latin not likely to exist among the hardy men who first landed upon our western shores but also indicate a labored method of naming places quite contrary to their custom of seizing upon some direct and obvious circumstance upon which to base their[14] choice. In all the length and breadth of California few, if any, instances exist where the Spaniards invented a name produced from the Latin or Greek in this far-fetched way. They saw a big bird, so they named the river where they saw it El Río del Pájaro (the River of the Bird), or they suffered from starvation in a certain canyon, so they called it La Cañada del Hambre (the Canyon of Hunger), or they reached a place on a certain saint’s day, and so they named it for that saint. They were practical men and their methods were simple.

In any case, since Mr. Hale has provided us with a more reasonable explanation, all such theories may be passed over as unworthy of consideration. While engaged in the study of Spanish literature, he was fortunate enough to run across a copy of an old novel, published in Toledo sometime between 1510 and 1521, in which the word California occurred as the name of a fabulous island, rich in minerals and precious stones, and said to be the home of a tribe of Amazons. This novel, entitled Las Sergas de Esplandián (The Adventures of Esplandián), was written by the author, García Ordonez de Montalvo, as a sequel[15] to the famous novel of chivalry, Amadís of Gaul, of which he was the translator. The two works were printed in the same volume. Montalvo’s romance, although of small literary value, had a considerable vogue among Spanish readers of the day, and that its pages were probably familiar to the early explorers in America is proved by the fact that Bernal Díaz, one of the companions of Cortés, often mentions the Amadís, to which the story of Esplandián was attached. The passage containing the name that has since become famous in all the high-ways and by-ways of the world runs as follows: “Know that on the right hand of the Indies there is an island called California, very near to the terrestrial paradise, which was peopled by black women, without any men among them, for they were accustomed to live after the manner of Amazons. They were of strong and hardened bodies, of ardent courage and of great force. The island was the strongest in the world, from its steep rocks and great cliffs. Their arms were all of gold and so were the caparisons of the wild beasts they rode.”

It was during the period when this novel was at the height of its popularity that Cortés wrote[16] to the King of Spain concerning information he had of “an island of Amazons, or women only, abounding in pearls and gold, lying ten days journey from Colima.” After having sent one expedition to explore the unknown waters in that direction, in 1535 or thereabout, an expedition that ended in disaster, he went himself and planted a colony at a point, probably La Paz, on the coast of Lower California. In his diary of this expedition, Bernal Díaz speaks of California as a “bay,” and it is probable that the name was first applied to some definite point on the coast, afterward becoming the designation of the whole region. The name also occurs in Preciado’s diary of Ulloa’s voyage down the coast in 1539, making it reasonable to suppose that it was adopted in the period between 1535 and 1539, whether by Cortés or some other person can not be ascertained.

Bancroft expresses the opinion that the followers of Cortés may have used the name in derision, to express their disappointment in finding a desert, barren land in lieu of the rich country of their expectations, but it seems far more in keeping with the sanguine nature of the Spaniards that their imaginations should lead them to draw a[17] parallel between the rich island of the novel, with its treasures of gold and silver, and the new land, of whose wealth in pearls and precious metals some positive proof, as well as many exaggerated tales, had reached them.

An argument that seems to clinch the matter of the origin of the name is the extreme improbability that two different persons, on opposite sides of the world, should have invented exactly the same word, at about the same period, especially such an unusual one as California.

As for the etymology of the word itself, it is as yet an unsolved problem. The suggestion that it is compounded of the Greek root kali (beautiful), and the Latin fornix (vaulted arch), thus making its definition “beautiful sky,” may be the true explanation, but even if that be so, Cortés or his followers took it at second hand from Montalvo and were not its original inventors.

Professor George Davidson, in a monograph on the Origin and the Meaning of the Name California, states that incidental mention had been made as early as 1849 of the name as occurring in Montalvo’s novel by George Ticknor, in his History of Spanish Literature, but Mr. Ticknor[18] refers to it simply as literature, without any thought of connecting it with the name of the state. This connection was undoubtedly first thought of by Mr. Hale and was discussed in his paper read before the Historical Society of Massachusetts in 1862; therefore the honor of the discovery of the origin of the state’s name must in justice be awarded to him. Professor Davidson, in an elaborate discussion of the possible etymology of the word, expresses the opinion that it may be a combination of two Greek words, kallos (beauty), and ornis (bird), in reference to the following passage in the book: “In this island are many griffins, which can be found in no other part of the world.” Its etymology, however, is a matter for further investigation. The one fact that seems certain is its origin in the name of the fabulous island of the novel.

It may well suffice for the fortunate heritors of the splendid principality now known as California that this charming name became affixed to it permanently, rather than the less “tuneful” one of New Albion, which Sir Francis Drake applied to it, and under which cognomen it appears on some English maps of the date.

Like many other places in California, San Diego (St. James), has had more than one christening. The first was at the hands of Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, who discovered the harbor in 1542, and named it San Miguel (St. Michael). Cabrillo was a Portuguese in the Spanish service, who was sent to explore the coast in 1542 by Viceroy Mendoza. “He sailed from Natividad with two vessels, made a careful survey, applied names that for the most part have not been retained, and described the coast somewhat accurately as far as Monterey. He discovered ‘a land-locked and very good harbor,’ probably San Diego, which he named San Miguel. ‘The next day he sent a boat farther into the port, which was large. A very great gale blew from the west-southwest, and south-southwest, but the port being good, they felt nothing.’ On the return from the north the[22] party stopped at La Posesión, where Cabrillo died on January third, from the effects of a fall and exposure. No traces of his last resting-place, almost certainly on San Miguel near Cuyler’s harbor, have been found; and the drifting sands have perhaps made such a discovery doubtful. To this bold mariner, the first to discover her coasts, if to any one, California may with propriety erect a monument.”—(Bancroft’s History of California.)

MISSION OF SAN DIEGO DE ALCALÁ, FOUNDED IN 1769.

“The first one of the chain of missions founded by the illustrious Junípero Serra.”

Then, in 1602, came Sebastián Vizcaíno, who changed the name from San Miguel to San Diego. He was “sent to make the discovery and demarcation of the ports and bays of the Southern Sea (Pacific Ocean),” and to occupy for Spain the California isles, as they were then thought to be. From the diary of Vizcaíno’s voyage we get the following account of his arrival at San Diego: “The next day, Sunday, the tenth of the said month (November), we arrived at a port, the best that there can be in all the Southern Sea, for, besides being guarded from all winds, and having a good bottom, it is in latitude 33½. It has very good water and wood, many fish of all sorts, of which we caught a great many with the net and[25] hooks. There is good hunting of rabbits, hares, deer, and many large quail, ducks and other birds. On the twelfth of the said month, which was the day of the glorious San Diego, the admiral, the priests, the officers, and almost all the people, went on shore. A hut was built, thus enabling the feast of the Señor San Diego to be celebrated.”

A party sent out to get wood “saw upon a hill a band of 100 Indians, with bows and arrows, and many feathers upon their heads, and with a great shouting they called out to us.” By a bestowal of presents, friendly relations were established. The account continues: “They had pots in which they cooked their food, and the Indian women were dressed in the skins of animals. The name of San Diego was given to this port.” Thus, it was the bay that first received the name, years afterwards given to the mission, then to the town. During the stay of Vizcaíno’s party the Indians came often to their camp with marten skins and other articles. On November 20, having taken on food and water, the party set sail, the Indians shouting a vociferous farewell from the beach (quedaban en la playa, dando boces.)

A long period of neglect of more than 160 years then ensued. The Indians continued to carry on their wretched hand-to-mouth existence, trapping wild beasts for their food and scanty clothing, fishing in the teeming streams, and keeping up their constant inter-tribal quarrels unmolested by the white man. Several generations grew up and passed away without a reminder of the strange people who had once been seen upon their shores, except perhaps an occasional white sail of some Philippine galleon seen flitting like a ghost on its southward trip along the coast.

Then the Spaniards, alarmed by reports of the encroachments of the Russians on the north, waked up from their long sleep, and determined to establish a chain of missions along the California coast. Father Junípero Serra was appointed president of these missions, and the first one of the chain was founded by him at San Diego in 1769. The name was originally applied to the “Old Town,” some distance from the present city. The founding party encountered great difficulties, partly through their fearful sufferings from scurvy, and partly from the turbulent and thievish nature of the Indians in that[27] vicinity, with whom they had several lively fights, and who stole everything they could lay their hands on, even to the sheets from the beds of the sick. During one of these attacks, the mission buildings were burned and one of the padres, Fray Luís Jaime, suffered a cruel death, but all difficulties were finally overcome by the strong hand of Father Serra, and the mission was placed on a firm basis. Its partially ruined buildings still remain at a place about six miles from the present city.

To return to the matter of the name, San Diego is doubly rich in possessing two titular saints, the bay having been undoubtedly named by Vizcaíno in honor of St. James, the patron saint of Spain, whereas the town takes its name from the mission, which perpetuates the memory of a canonized Spanish monk, San Diego de Alcalá. The story of St. James, the patron of Spain, runs as follows: “As one of Christ’s disciples, a nobleman’s son who chose to abandon his wealth and follow Jesus, he was persecuted by the Jews, and finally beheaded. When dragged before Herod Agrippa, his gentleness touched the soul of one of his tormentors, who begged to die with him.[28] James gave him a kiss, saying ‘Pax Vobiscum’ (peace be with you), and from this arose the kiss of peace which has been used in the church since that time. The legend has it that his body was conducted by angels to Spain, where a magnificent church was built for its reception, and that his spirit returned to earth and took an active part in the military affairs of the country. He was said to have appeared at the head of the Spanish armies on thirty-eight different occasions, most notably in 939, when King Ramírez determined not to submit longer to the tribute of one hundred virgins annually paid to the Moors, and defied them to a battle. After the Spaniards had suffered one repulse, the spirit of St. James appeared at their head on a milk-white charger, and led them to a victory in which sixty thousand Moors were left dead on the field. From that day ‘Santiago!’ has been the Spanish war-cry.”—(From Clara Erskine Clement’s Stories of the Saints.)

It happens, rather curiously, that in the Spanish language St. James appears under several different forms, Santiago, San Diego and San Tiago. The immediate patron of our southernmost city, San Diego de Alcalá, was a humble Capuchin[29] brother in a monastery of Alcalá. It is said that the infante Don Carlos was healed of a severe wound through the intercession of this saint, and that on this account Philip II promoted his canonization.

May the spirit of the “glorious San Diego” shed some of his tender humanity upon the city of which he is the protector!

Coronado Beach, the long spit of land forming the outer shore of the harbor of San Diego, “derived its name from the Coronado Islands near it. These islands were originally named by the Spaniards in honor of Coronado. When the improvement of the sand spit opposite San Diego City and facing the Coronado Islands was made in 1885, the name of Coronado Beach was bestowed upon it.”—(Charles B. Turrill, San Francisco.)

In all the history of Spain in western America there is nothing more romantic than the story of the famous explorer, Francisco Vásquez de Coronado,[30] who, with the delightful childlike faith of his race, marched through Texas and Kansas in search of the fabulous city of Gran Quivira, “where every one had his dishes made of wrought plate, and the jugs and bowls were of gold,” and then marched back again! Imagine our hard-headed Puritan ancestors setting forth on such a quest!

MISSION OF SAN ANTONIO DE PALA, FOUNDED IN 1816.

“Many a romantic tale has been told about the ‘bells of Pala’!”

San Luís Rey de Francia (St. Louis King of France), is the name of the mission situated in a charming little valley about forty miles north of San Diego and three miles from the sea. It was founded June 13, 1798, by Padres Lasuén, Santiago and Peyri, and its ruins may still be seen upon the spot. A partial restoration has been made of these buildings and they are now used by the Franciscans. The exact circumstances of its naming have not come to light, but we know of its patron saint that his holiness was such that even Voltaire said of him: “It is scarcely given to man to push virtue further.” Born at Poissy in 1215, the son of Louis VIII and Blanche of[33] Castile, he became noted for his saintliness, and twice led an army of Crusaders in the “holy war.”

Pala, often misspelled palo, through an accidental resemblance to the Spanish word palo (stick or tree), is situated some fifteen miles or more to the northeast of San Luís Rey, and is the site of the sub-mission of San Antonio de Pala, founded in 1816 by Padre Peyri as a branch of San Luís Rey. This mission was unique in having a bell-tower built apart from the church, and many romantic stories have been told about the “bells of Pala.” It was located in the center of a populous Indian community, and it happens, rather curiously, that the word itself has a significance both in Spanish and Indian, meaning in Spanish “spade” and in Indian “water.” The Reverend George Doyle, pastor at the mission of San Antonio de Pala, writes the following in regard to this name: “The word ‘Pala’ is an Indian word, meaning, in the Cupanian Mission Indian language, ‘water,’ probably due to the[34] fact that the San Luís Rey River passes through it. The proper title of the mission chapel here is San Antonio de Padua, but as there is another San Antonio de Padua mission chapel in the north, to distinguish between the two some one in the misty past changed the proper title of the Saint, and so we have ‘de Pala’ instead of ‘de Padua.’ Some writers say Pala is Spanish, but this is not true, for the little valley in no way resembles a spade, and the Palanian Indians were here long before the Franciscan padres brought civilization, Christianity and the Spanish language.”

Pala, in this case, is almost certainly Indian, and originates in a legend of the Luiseños. According to this legend, one of the natives of the Temécula tribe went forth on his travels, stopping at many places and giving names to them. One of these places was a canyon, “where he drank water and called it pala, water.”—(The Religion of the Luiseño Indians, by Constance Goddard Dubois, in the Univ. of Cal. Publ. of Arch. and Tech.)

San Juan Capistrano (St. John Capistrano), was at one time sadly mutilated by having its first part clipped off, appearing on the map as Capistrano, but upon representations made by Zoeth S. Eldredge it was restored to its full form by the Post Office Department. A mission was founded at this place, which is near the coast about half-way between San Diego and Los Ángeles, by Padres Serra and Amurrio, November 1, 1776, the year of our own glorious memory. While on the other side of the continent bloody war raged, under the sunny skies of California the gentle padres were raising altars to the “Man of Peace.”

The buildings at this place were badly wrecked by an earthquake on December 8, 1812, yet the ruins still remain to attest to the fact that this was at one time regarded as the finest of all the mission structures.

Its patron saint, St. John Capistrano, was a Franciscan friar who lived at the time of the crusades, and took part in them. A colossal statue of him adorns the exterior of the Cathedral at[36] Vienna. It represents him as having a Turk under his feet, a standard in one hand, and a cross in the other.

There remain some names in the San Diego group of less importance, yet possessing many points of interest, which will be included in the following list, with an explanation of their meanings, and their history wherever it has been possible to ascertain it.

ARCHWAY AT CAPISTRANO.

“At one time regarded as the finest of all the mission structures.”

Agua Tibia (warm water, warm springs), is in San Diego County. For some reason difficult to divine, this perfectly simple name has been the cause of great confusion in the minds of a number of writers. In one case the almost incredibly absurd translation “shinbone water” has been given. It may be thought that this was intended as a bit of humor, but it is greatly to be feared that the writer mixed up the Spanish word tibia, which simply means “tepid, warm,” with the Latin name of one of the bones of the lower leg, the tibia. In another case the equally absurd[39] translation “flute water” has been given. Where such a meaning could have been obtained is beyond comprehension to any person possessing even a slight knowledge of the Spanish language. Agua Tibia is no more nor less than “warm water,” applied in this case to warm springs existing at that place. This extreme case is enlarged upon here as an example of the gross errors that have been freely handed out to an unsuspecting public in the matter of our place names. There are many more of the same sort, and the authors of this inexcusable stuff have been accepted and even quoted as authorities on the subject. Those of us who love our California, in other words all of us, can not fail to be pained by such a degradation of her romantic history.

Ballena (whale), is in San Diego County at the west end of Ballena Valley, and as it is a good many miles inland its name seems incongruous, until we learn from one of its residents that it was so-called in reference to a mountain in the valley whose outline along the top is exactly the shape of a humpbacked whale.

“This place has probably no connection with[40] Ballenas, a name applied to a bay in Lower California on account of its being a favorite resort of the Humpback whale.”—(Mr. Charles B. Turrill.)

Berenda, in Merced County, is a misspelling of Berrendo or Berrenda.

Berrendo (antelope). A writer whose knowledge of Spanish seems to be wholly a matter of the dictionary, confused by the fact that the definition given for berrendo is “having two colors,” has offered the fantastic translation of El Río de los Berrendos as “The River of two Colors.” Although the idea of such a river, like a piece of changeable silk, may be picturesque, the simple truth is that the word berrendo, although not so-defined in the dictionaries, is used in Spanish America to signify a deer of the antelope variety and frequently occurs in that sense in the diaries. Miguel Costansó, an engineer accompanying the Portolá expedition of 1769, says: “Hay en la tierra venados, verrendos (also spelled berrendos), muchos liebres, conejos, gatos monteses y ratas (there are in the land deer, antelope, many hares, rabbits, wild-cats and rats).” On August 4 this party reached a place forty leagues from San Diego which they called Berrendo because they caught[41] alive a deer which had been shot the day before by the soldiers and had a broken leg. Antelope Creek, in Tehama County, was originally named El Río de los Berrendos (The River of the Antelopes), undoubtedly because it was a drinking place frequented by those graceful creatures, and Antelope Valley, in the central part of the state, must have received its name in the same way.

El Cajón (the box), about twelve miles northeast of San Diego, perhaps received its name from a custom the Spaniards had of calling a deep canyon with high, box-like walls, un cajón (a box).

Caliente Creek (hot creek), is in the northern part of San Diego County.

Campo (a level field), also sometimes used in the sense of a camp, is the name of a place about forty miles east-southeast of San Diego, just above the Mexican border. Campo was an Indian settlement, and may have been so-called by the Spaniards simply in reference to the camp of Indians.

Cañada del Bautismo (glen of the baptism), so-called from the circumstance that two dying native children were there baptized by the padres,[42] as told in the diary of Miguel Costansó, of the Portolá expedition of 1769. Death, when it came to the children of the natives, was often regarded as cause for rejoicing by the missionaries, not, of course, through any lack of humanity on their part, but because the Indian parents more readily consented to baptism at such a time, and the padres regarded these as so many souls “snatched from the burning.”

Carriso (reed grass), is the name of a village and creek in San Diego County.

Chula Vista (pretty view), is the name of a town near the coast, a few miles southeast of San Diego. Chula is a word of Mexican origin, meaning pretty, graceful, attractive. “This name was probably first used by the promoters during the boom of 1887.”—(Mr. Charles B. Turrill.)

La Costa (the coast), a place on the shore north of San Diego.

Coyote Valley, situated just below the southern border of the San Jacinto Forest Reservation. Coyote, the name of the wolf of Western America, is an Aztec word, originally coyotl.

Cuyamaca is probably derived from the land grant of that name, which in turn took its name[43] from the Cuyamaca Mountain, which, according to the scientists, was so-called in reference to the clouds and rain gathering around its summit. Mr. T. T. Waterman, instructor in Anthropology at the University of California, says the word is derived from two Indian words, kwe (rain), and amak (yonder), and consequently means “rain yonder.” The popular translation of it as “woman’s breast” is probably not based on fact. There was an Indian village of that name some miles northwest of San Diego.

Descanso (rest), is the name of a place northeast of San Diego, so-called by a government surveying party for the reason that they stopped here each day for rest.

Dulzura (sweetness), is the name of a place but a few miles north of the Mexican border line. What there was of “sweetness” in the history of this desolate mining camp can not be discovered.

Encinitas (little oaks), is a place on the coast about twenty miles northwest of San Diego.

Escondido (hidden), a place lying about fifteen miles from the coast, to the northeast of San Diego. It is said to have been so-named on account of its location in the valley. A place at[44] another point was called Escondido by the Spaniards because of the difficulty they experienced in finding the water for which they were anxiously searching, and it may be that in this case the origin of the name was the same.

La Jolla, a word of doubtful origin, said by some persons to mean a “pool,” by others to be from hoya, a hollow surrounded by hills, and by still others to be a possible corruption of joya, a “jewel.” The suggestion has been made that La Jolla was named from caves situated there which contain pools, but until some further information turns up this name must remain among the unsolved problems. There is always the possibility also that La Jolla means none of these things but is a corruption of some Indian word with a totally different meaning. More than one place in the state masquerades under an apparently Spanish name which is in reality an Indian word corrupted into some Spanish word to which it bore an accidental resemblance in sound. Cortina (curtain) is an example of this sort of corruption, it being derived from the Indian Ko-tina.

Laguna del Corral (lagoon of the yard). Corral is a word much in use to signify a space of ground[45] enclosed by a fence, often for the detention of animals. In one of the diaries an Indian corral is thus spoken of: “Near the place in which we camped there was a populous Indian village; the inhabitants lived without other protection than a light shelter of branches in the form of an enclosure; for this reason the soldiers gave to the whole place the name of the Ranchería del Corral (the village of the yard).” There are other corrals and corralitos (little yards) in the state.

Linda Vista (charming or pretty view), is the name of a place ten or twelve miles due north of San Diego.

Point Loma (hill point). Loma means “hill,” hence Point Loma, the very end of the little peninsula enclosing San Diego bay, is a high promontory.

De Luz (a surname), that of a pioneer family. The literal meaning of the word luz is “light.”

Del Mar (of or on the sea), the name of a place on the shore about eighteen miles north of San Diego.

La Mesa (literally “the table”), used very commonly to mean “a high, flat table-land.” La Mesa, incorrectly printed on some of the maps as[46] one word, Lamesa, lies a few miles to the northeast of San Diego.

Mesa Grande (literally “big table”), big table-land, is some distance to the northeast of San Diego.

El Nido (the nest), is southeast of San Diego, near the border.

Potrero (pasture ground), is just above the border line. There are many Potreros scattered over the state.

La Presa (the dam or dike). La Presa is a few miles east of San Diego, on the Sweetwater River, no doubt called Agua Dulce by the Spaniards.

Los Rosales (the rose-bushes), a spot located in the narratives of the Spaniards at about seventeen leagues from San Diego, and two leagues from Santa Margarita. Nothing in the new land brought to the explorers sweeter memories of their distant home than “the roses of Castile” which grew so luxuriantly along their pathway as to bring forth frequent expressions of delight from the padres. This particular place we find mentioned in the diary of Miguel Costansó, as follows: “We gave it the name of Cañada de los Rosales (glen of the rose-bushes), on account of[47] the great number of rose-bushes we saw.”—(Translation edited by Frederick J. Teggart, Curator of the Academy of Pacific Coast History.)

Temécula, the name of a once important Indian village in the Temécula Valley, about thirty-five miles south of Riverside. Its inhabitants suffered the usual fate of the native when the white man discovers the value of the land, and were compelled to leave their valley in 1875, and remove to Pichanga Canyon, in a desert region.

Tía Juana (literally Aunt Jane). Travelers on the way to Mexico who stop for customs examination at this border town are no doubt surprised by its peculiar name. This is an example of the corruption, through its resemblance in sound, of an Indian word, Tiwana, into Tía Juana, Spanish for “Aunt Jane.” Tiwana is said to mean “by the sea,” which may or may not be the correct translation.

Los Ángeles (the angels). In the diary of Miguel Costansó, date of August 2, 1769, we read: “To the north-northeast one could see another water-course or river bed, which formed a wide ravine, but it was dry. This water-course joined that of the river, and gave clear indications of heavy floods during the rainy season, as it had many branches of trees and debris on its sides. We halted at this place, which was named La Porciúncula. Here we felt three successive earthquakes during the afternoon and night.”—(Translation edited by Frederick J. Teggart.)

This was the stream upon which the city of Los Ángeles was subsequently built and whose name became a part of her title. Porciúncula was the name of a town and parish near Assisi which became the abode of St. Francis de Assisi after the Benedictine monks had presented him, about 1211, with the little chapel which he called, in a[52] jocular way, La Porciúncula (the small portion). By order of Pius V, in 1556 the erection of a new edifice over the Porciúncula chapel was begun. Under the bay of the choir is still preserved the cell in which St. Francis died, while a little behind the sacristy is the spot where the saint, during a temptation, is said to have rolled in a brier-bush, which was then changed into thornless roses.—(Catholic Encyclopedia.) In this story there is a curious interweaving of the history of the names of our two rival cities, St. Francis in the north and Los Ángeles de Porciúncula in the south.

Continuing their journey on the following day, the Portolá party reached the Indian ranchería (village) of Yangna, the site chosen for the pueblo established at a later date. Father Crespi writes of it thus: “We followed the road to the west, and the good pasture land followed us; at about half a league of travel we encountered the village of this part; on seeing us they came out on the road, and when we drew near they began to howl, as though they were wolves; we saluted them, they wished to give us some seeds, and as we had nothing at hand in which to carry them, we did not accept them; seeing this, they threw some[53] handfuls on the ground and the rest in the air.”

August 2 being the feast day of Nuestra Señora de los Ángeles, as the Virgin Mary is often called by the Spaniards, this name was given to the place.

The actual founding of the pueblo did not occur until September 4, 1781, when Governor Neve issued the order for its establishment upon the site of the Indian village Yangna. It is said that the Porciúncula River, henceforth to be known as the Los Ángeles, at that time ran to the east of its present course. The name of the little stream was added to that of the pueblo, so that the true, complete title of the splendid city which has grown up on the spot where the Indian once raised his wolf-like howl is Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles de Porciúncula (Our Lady the Queen of the Angels of Porciúncula).

The social beginnings of Los Ángeles were humble indeed, the first settlers being persons of mixed race, and the first houses mere hovels, made of adobe, with flat roofs covered with asphalt from the springs west of the town.

La Brea (the asphalt), has been retained as the appropriate designation of the ranch containing the famous asphaltum beds near Los Ángeles. Ever since the days of the Tertiary Age, the quaking, sticky surface of these beds has acted as a “death trap” for unwary animals, and the remains of the unfortunate creatures have been securely preserved down to our times, furnishing indisputable evidence of the strange life that once existed on our shores. Fossils of a large number of pre-historic and later animals have been taken out, aggregating nearly a million specimens of bird and animal life, many of them hitherto unknown to science. Among them are the saber-tooth tiger, gigantic wolves, bears, horses, bison, deer, an extinct species of coyote, camels, elephants, and giant sloths. Remains are also found of mice, rabbits, squirrels, several species of insects, and a large number of birds, such as ducks, geese, pelicans, eagles and condors.

Among the most remarkable of these fossils are the saber-tooth tiger and the great wolf.[55] Specimens of the wolf have been found which are among the largest known in either living or extinct species. This wolf differs from existing species in having a larger and heavier skull and jaws, and in its massive teeth, a conformation that must have given it great crushing power. The structure of the skeleton shows it to have been probably less swift, but more powerful than the modern wolf, and the great number of bones found indicate that it was exceedingly common in that age. One bed of bones was uncovered in which the number of saber-tooth and wolf skulls together averaged twenty per cubic yard. Altogether, the disappearance of these great, ferocious beasts from the California forests need cause no keen regret.

Next to the large wolf the most common is the saber-tooth tiger, of which one complete skeleton and a large number of bones have been found. The skeleton shows the animal to have been of about the size of a large African lion, and its most remarkable characteristic was the extraordinary length of the upper canine teeth, which were like long, thin sabers, with finely serrated edges. These teeth were awkwardly placed for ordinary[56] use, and it is thought by scientists that they were used for a downward stab through the thick necks of bulky creatures, such as the giant sloth. There is also an unusual development of the claws, possibly to make up for the loss of grasping power in the jaws, resulting from the interference of the long saber teeth. It appears from the state of many of the fossils that these teeth were peculiarly liable to fracture, and accidents of this sort may have led to the extinction of the species, the animal thus perishing through the over-development of one of its characteristics.

Fossils of the extinct horse and bison are common, and a smaller number are found of camels, deer, goats, and the mammoth. The bison were heavy-horned and somewhat larger than the existing species of buffalo. The camel, of which an almost complete specimen has very recently been taken out by Professor R. C. Stoner, of the University of California, was much larger than the present day species. Since the above was put in type, a human skeleton has been taken from the vicinity of the La Brea bed. Whether this skeleton belongs with the La Brea deposits, and what its comparative age in relation to other human[57] remains may be, are matters now being investigated by scientists.

The preponderance of meat-eating animals in the La Brea beds has attracted the attention of scientists, who believe that these creatures were lured to the spot in large numbers by the struggles and cries of their unfortunate prey caught in the sticky mass of the tar. In this way, a single sloth, or other creature, may have been the means of bringing retribution upon a whole pack of wolves.—(Notes taken from an article in the Sunset Magazine of October, 1908, entitled The Death Trap of the Ages, by John C. Merriam, Professor of Paleontology in the University of California.)

The manner in which this great aggregation of animals came to a tragic end in that long-past age is exemplified in the way that birds and other small animals are still occasionally caught in the treacherous asphalt and there perish miserably, adding their bones to those of their unhappy predecessors.

The La Brea beds furnish one of the richest fields for paleontological research to be found anywhere in the world; and it may be said, that with her great Sequoias in the north, and her[58] reservoir of pre-historic remains in the south, California stands as a link between a past age and the present.

The tarry deposit itself has its own place in history, for it appears that the first settlers of Los Ángeles were alive to the practical value of this supply of asphaltum lying ready to their hands, and used it in roofing their houses. Even the Indians, little as is the credit usually given them for skill in the arts and crafts, recognized the possibilities of this peculiar substance, and used it in calking their canoes.

The story of Los Ojitos (literally “little eyes”), but here used in the sense of “little springs,” situated about two leagues from Santa Ana, indicates that the pleasures of social intercourse were not altogether lacking among the California Indians. In the diary of Miguel Costansó, of the date of their arrival at this place, he writes: “We found no water for the animals, but there was sufficient for the people in some little springs[59] or small pools, in a narrow canyon close to a native village. The Indians of this village were holding a feast and dance, to which they had invited their relatives of the Río de los Temblores (River of the Earthquakes, or Santa Ana).”—(Translation edited by Frederick J. Teggart.) During this time the travelers experienced a series of earthquakes lasting several days.

Ojo de agua was commonly used by the Spaniards to mean a spring, but during the eighteenth century it was frequently used in America in the sense of a small stream of water rather than a spring.

On the day, Friday, July 28, 1769, of the arrival of the Portolá expedition at the stream now called the Santa Ana, which takes its rise in the San Bernardino Mountains, and empties into the ocean at a point southeast of Los Ángeles, four severe earthquakes occurred. Speaking of this circumstance in his diary, Father Crespi says: “To this spot was given El Dulce Nombre de Jesús de los Temblores (The Sweet Name of Jesus of the[60] Earthquakes), because of having experienced here a frightful earthquake, which was repeated four times during the day. The first, which was the most violent, happened at one o’clock of the afternoon, and the last about four o’clock. One of the gentiles (unbaptized Indians), who happened to be in the camp, and who, without doubt, exercised among them the office of priest, no less terrified at the event than we, began, with horrible cries and great demonstrations, to entreat Heaven, turning to all points of the compass. This river is known to the soldiers as the Santa Ana.” This was one of the rare cases where the usual method of naming was reversed, and the soldiers chose the name of the saint. St. Anna was the mother of the Virgin and her name signifies “gracious.”

In the account of Captain Pedro Fages, of the same expedition, the natives on this stream are described as having light complexions and hair, and a good appearance, differing in these particulars from the other inhabitants of that region, who were said to be dark, dirty, under-sized and slovenly. This is not the only occasion when the Spaniards reported finding Indians of light complexions and hair in California. One account[61] speaks of a red-haired tribe not far north of San Francisco, and still another of “white Indians” at Monterey, but, judging by the light of our subsequent knowledge of these aborigines, the writers of these reports must have indulged in exaggeration.

On the southern bank of the Santa Ana, not far from the coast, is the town of the same name, and further inland its waters have made to bloom in the desert the famous orange orchards of Riverside.

Santa Mónica, situated at the innermost point of the great curve in the coast line just west of Los Ángeles, was named in honor of a saintly lady whose story is here quoted from Clara Erskine Clement’s Stories of the Saints: “She was the mother of St. Augustine, and was a Christian, while his father was a heathen. Mónica was sorely troubled at the dissipated life of her young son; she wept and prayed for him, and at last sought the advice and aid of the Bishop of Carthage, who dismissed her with these words. ‘Go in[62] peace; the son of so many tears will not perish.’ At length she had the joy of beholding the baptism of St. Augustine by the Bishop of Milan.”

Santa Mónica is venerated as the great patroness of the Augustinian nuns, and might well be placed at the head of the world-wide order of “Anxious Mothers.”

Santa Catalina, the beautiful island off the coast of Southern California, was named by Vizcaíno in honor of St. Catherine, because its discovery occurred on the eve of her feast day, November 24, 1602. In the diary of the voyage we get an interesting description of the island and its aboriginal inhabitants: “We continued our journey along the coast until November 24, when, on the eve of the glorious Santa Catalina, we discovered three large islands; we took the one in the middle, which is more than twenty-five leagues in circumference, on November 27, and before dropping anchor in a good cove which was found, a great number of Indians came out in canoes of[63] cedar-wood and pine, made of planking well-joined and calked, and with eight oars each, and fourteen or fifteen Indians, who looked like galley-slaves. They drew near and came on board our vessels without any fear whatever. We dropped anchor and went on shore. There were on the beach a great number of Indians, and the women received us with roasted sardines and a fruit cooked in the manner of sweet potatoes.”

Mass was celebrated there in the presence of 150 Indians. The people were very friendly and the women led the white men by the hand into their houses. The diary continues: “These people go dressed in the skins of seals; the women are modest but thievish. The Indians received us with embraces and brought water in some very well-made jars, and in others like flasks, that were highly varnished on the outside. They have acorns and some very large skins, with long wool, apparently of bears, which serve them for blankets.”

The travelers found here an idol, “in the manner of the devil, without a head, but with two horns, a dog at the feet, and many children painted around it.” The Indians readily gave up this idol and accepted the cross in its stead.

St. Catherine, patroness of this island, was one of the most notable female martyrs of the Roman Catholic church. We are told that she was of royal blood, being the daughter of a half-brother of Constantine the Great. She was converted to Christianity, and became noted for her unusual sanctity. She was both beautiful and intellectual, and possessed the gift of eloquence in such a high degree that she was able to confound fifty of the most learned men appointed by Maximin to dispute matters of religion with her. The same Maximin, enraged by her refusal of his offers of love, ordered that she be tortured “by wheels flying in different directions, to tear her to pieces. When they had bound her to these, an angel came and consumed the wheels in fire, and the fragments flew around and killed the executioners and 3000 people. Maximin finally caused her to be beheaded, when angels came and bore her body to the top of Mt. Sinai. In the eighth century a monastery was built over her burial place.”—(Stories of the Saints.) Santa Catalina is the patroness of education, science, philosophy, eloquence, and of all colleges, and her island has good reason to be satisfied with the name chosen by Vizcaíno.

Of Las Ánimas (the souls), which lay between San Gabriel and the country of the Amajaba (Mojave) Indians, we find the story in Fray Joaquín Pasqual Nuez’s diary of the expedition made in 1819 by Lieutenant Gabriel Moraga, to punish the marauding Amajabas, who had murdered a number of Christian natives. This name was also used as the title of a land grant just south of Gilroy.

The Moraga party arrived at a point “about a league and a half from Our Lady of Guadalupe of Guapiabit. We found the place where the Amajabas killed four Christians of this mission (San Gabriel), three from San Fernando, and some gentiles (unbaptized Indians). We found the skeletons and skulls roasted, and, at about a gun-shot from there we pitched camp. The next day, after mass, we caused the bones to be carried in procession, the cross in front, Padre Nuez chanting funeral services, to the spot where they had been burned. There we erected a cross, at the foot of which we caused the bones to be buried[66] in a deep hole, and then we blessed the sepulchre. We named the spot Las Ánimas Benditas (The Blessed Souls).” May they rest in peace!

San Gabriel, the quaint little town lying nine miles east of Los Ángeles, is the site of the Mission San Gabriel Arcángel (St. Gabriel Archangel), founded September 8, 1771, by Padres Cambón and Somera. This mission was placed in a fertile, well-wooded spot, in the midst of a large Indian population, who, under the instruction of the padres, became experts in many arts, such as sewing, weaving, soap-making, cobbling, etc. Their flocks and herds increased to such an extent that they covered the country for many miles around.

The patron saint, San Gabriel, was the second in rank of the archangels who stand before the Lord. Whenever he is mentioned in the Bible, it is as a messenger bearing important tidings, and he is especially venerated as having carried to the Virgin the message that she was to become the mother of Christ.

MISSION OF SAN GABRIEL ARCÁNGEL, FOUNDED IN 1771, SHOWING INDIAN HUTS IN THE FOREGROUND.

“Its flocks and herds once covered the country for many miles around.”

It was in the valley of San Fernando (St. Ferdinand), a short distance northwest of Los Ángeles, that the mission pertaining to the latter place was established, September 8, 1797, by Padres Lasuén and Dumetz. The Camulos Rancho, the home of Ramona, the heroine of Mrs. Helen Hunt Jackson’s romance, was once included in the lands of this mission.

St. Ferdinand, King of Spain, in whose honor this place was named, was a notable warrior, as well as a saint, and he succeeded in expelling the Moors from Toledo, Córdova and Seville. He is said also to have been a patron of the arts, and to have been the founder of the cathedral at Burgos, celebrated for the beauty of its architecture. But more than for such attainments, he is remembered for his tenderness toward the poor and lowly of his people. When urged to put a tax upon them in order to recruit his army, he replied: “God, in whose cause I fight, will supply my need. I fear more the curse of one poor old woman than a whole army of Moors.”—(Stories of the Saints.)

Temescal (sweathouse), in Riverside County, although a place of no great importance in itself, is interesting in that its name recalls one of the curious customs widely prevalent among the natives of the Southwest. The word itself is of Aztec origin, and was brought to California by the Franciscans.

The temescal is thus described by Dr. A. L. Kroeber, in the University of California Publications in Archaeology and Ethnology: “At the Banning Reservation a sweathouse is still in use. From the outside its appearance is that of a small mound. The ground has been excavated to the depth of a foot or a foot and a half, over a space of about twelve by seven or eight feet. In the center of this area two heavy posts are set up three or four feet apart. These are connected at the top by a log laid in their forks. Upon this log, and in the two forks, are laid some fifty or more logs and sticks of various dimensions, their ends sloping down to the edge of the excavation. It is probable that brush covers these timbers.[71] The whole is thoroughly covered with earth. There is no smoke hole. The entrance is on one of the long sides, directly facing the space between the two center posts, and only a few feet from them. The fireplace is between the entrance and the posts. It is just possible to stand upright in the center of the house. In Northern California, the so-called sweathouse is of larger dimensions, and was preëminently a ceremonial or assembly chamber.”

Dr. L. H. Bunnell, in his history of the discovery of the Yosemite valley, gives us some interesting details of the use of the sweathouse among the Indians of that region: “The remains of these structures were sometimes mistaken for tumuli, being constructed of bark, reeds or grass, covered with mud. It (the sweathouse), was used as a curative for disease, and as a convenience for cleansing the skin, when necessity demands it, although the Indian race is not noted for cleanliness. I have seen a half-dozen or more enter one of these rudely constructed sweathouses through the small aperture left for the purpose. Hot stones are taken in, the aperture is closed until suffocation would seem impending, when they[72] would crawl out, reeking with perspiration, and with a shout, spring like acrobats into the cold waters of the stream. As a remedial agent for disease, the same course is pursued, though varied at times by the burning and inhalation of resinous boughs and herbs. In the process of cleansing the skin from impurities, hot air alone is generally used. If an Indian had passed the usual period of mourning for a relative, and the adhesive pitch too tenaciously clung to his no longer sorrowful countenance, he would enter and re-enter the heated house until the cleansing had become complete. The mourning pitch is composed of the charred bones and ashes of the dead relative or friend. These remains of the funeral pyre, with the charcoal, are pulverized and mixed with the resin of the pine; this hideous mixture is usually retained upon the face of the mourner until it wears off. If it has been well-compounded, it may last nearly a year; although the young, either from a super-abundance of vitality, excessive reparative powers of the skin, or from powers of will, seldom mourn so long. When the bare surface exceeds that covered by the pitch, it is not a scandalous disrespect in the young to remove it[73] entirely, but a mother will seldom remove pitch or garment until both are nearly worn out.”

This heroic treatment, while possibly efficacious in the simple ailments by which the Indians were most often afflicted, usually resulted in a great increase of mortality in the epidemics of smallpox following upon the footsteps of the white man. One traveler speaks of a severe sort of intermittent fever, to which the natives were subject, and of which so many died that hundreds of bodies were found strewn about the country. Having observed that the whites, even when attacked by this fever, rarely died of it, he was inclined to ascribe the mortality among the natives to their great cure-all, the temescal.

A number of places in the state bore this name, among them a small town lying between the sites now occupied by the flourishing cities of Oakland and Berkeley. Its citizens became discontented with the undignified character of the name, and changed it to Alden.

San Bernardino is the name of a county in the southeastern part of California, whose broad expanse is mainly made up of volcanic mountains, desert plains, and valleys without timber or water.

The name was first given to the snow-capped peak, 11,600 feet high, lying about twenty miles east of the city of San Bernardino, which is situated sixty miles east of Los Ángeles, in the fruit and alfalfa region. The name of this town is one of the most regrettable examples of corruption that have occurred in the state, having passed from its original sweetly flowing syllables through the successive stages of San Berdino, Berdino, until finally reaching the acme of vulgarity as Berdoo, by which appellation it is known to its immediate neighbors. If ideas of romance, of pleasant-sounding words, and of fidelity to history make no appeal to our fellow-Californians, let them read again the quotation from Stevenson given above, and learn that a romantic nomenclature may sometimes be a valuable financial asset.

San Bernardino (St. Bernardinus), the patron saint of the places bearing his name, is particularly remembered as the founder of the charitable institution known in Spanish as Monte de Piedad (hill of pity), and in French as Mont de Piété, municipal pawnshops where money was loaned on pledges to the poor. These pawnshops are still conducted in many Spanish towns, in America as well as in Europe.

Abalone Point, some miles to the southeast of San Pedro bay, was no doubt so-named from the abundance of the great sea snails called abalone, whose iridescent shells, the abandoned dwellings of the dead animals, almost comparable in beauty to the mother-of-pearl, once covered the beaches of the California coast with a glittering carpet. The word “once” is used advisedly, for, with our usual easy-going American negligence we have permitted these creatures of the sea, valuable for their edible meat as well as for their exquisitely colored shells, to be nearly destroyed[76] by Chinese and Japanese fisheries. That the flesh of the abalone formed a useful part of the food supply of the Indians is evidenced by the large number of shells to be found in the mounds along the shore. In the living state the abalone clings to the rocks on the shore, and its grip is so tenacious that more than one unfortunate person, caught by the foot or hand between the shell and the rock, has been held there while death crept slowly upon him in the shape of the rising tide. There is another Abalone Point on the northern coast.

Agua Caliente (literally “hot water”), generally used in reference to hot springs. Of these there are many in the state, one on the Indian Reservation southeast of Riverside. Agua Caliente was originally a land grant.

Alamitos (little cottonwoods), from álamo, a tree of the poplar family indigenous to California. There are several places bearing this name in the state, one a short distance northeast of Santa Ana.

Aliso (alder tree), is the name of a place on the Santa Fé Railroad, south of Los Ángeles, near the shore, and was probably named for[77] the Rancho Cañada de los Alisos. It is probably modern.

Azusa is the name of a place in Los Ángeles County, twenty miles east of Los Ángeles, and was originally applied to the land grant there. It is an Indian place name of a lodge, or ranchería, the original form being Asuksa-gna, the gna an ending which indicates place.

Bandini (a surname), is the name of a place a short distance southeast of Los Ángeles, on the Santa Fé Railroad. The founder of this family was José Bandini, a mariner of Spanish birth, who came to California with war supplies, and finally settled at San Diego. His son, Juan Bandini, was a notable character in the history of the state. He held several public offices, took part in revolutions and colonization schemes, and finally espoused the cause of the United States. Bancroft gives the following resumé of his character: “Juan Bandini must be regarded as one of the most prominent men of his time in California. He was a man of fair abilities and education, of generous impulses, of jovial temperament, a most interesting man socially, famous for his gentlemanly manners, of good courage in the midst of[78] personal misfortunes, and always well-liked and respected; indeed his record as a citizen was an excellent one. In his struggles against fate and the stupidity of his compatriots he became absurdly diplomatic and tricky as a politician. He was an eloquent speaker and fluent writer.” Members of the Bandini family still occupy positions of respect and influence in the state and have made some important additions to its historical literature.

Bolsa (pocket), a term much in use with the Spaniards to signify a shut-in place. Bolsa is in Orange County, twelve miles north by west of Tres Pinos, and was probably named from the land grant, Rancho de las Bolsas.

Cabezón (big head), is the name of a place southeast of Colton. It was probably named for a large-headed Indian chief who lived there at one time and who received this name in pursuance of an Indian custom of fitting names to physical peculiarities. This name is improperly spelled on some maps as Cabazon.

Cahuilla, the name of an Indian tribe, probably “Spanishized” in its spelling from Ka-we-a. The valley and village of this name are situated in the[79] San Jacinto Forest Reserve, southeast of Riverside, and received their name from a tribe who lived, in 1776, on the northern slopes of the San Jacinto Mountains. The word Cahuilla is of uncertain derivation.

Calabazas (pumpkins), is northwest of Los Ángeles. This is possibly a corruption of an Indian word, Calahuasa, the name of a former Chumash village near the mission of Santa Inez. There is another possibility that this name may have been given to the place by the Spaniards in reference to the wild gourd which grows abundantly there and whose fruit may have been considered by them to bear some resemblance to pumpkins, but this is of course mere conjecture.

Casa Blanca (white house), is a short distance west of Riverside, on the Santa Fé Railroad, so-called from a large white ranch house once in conspicuous view from the railroad station.

Casco (skull), shell or outside part of anything. El Casco is situated about twelve miles east of Riverside. Its application here has not been ascertained.

Conejo (rabbit), is the name of a number of places in the state, one of them in the Santa[80] Mónica Mountains, another in the Central Valley, on the Santa Fé road.

Cucamonga, is an Indian name, derived from a village in San Bernardino County, forty-two miles by rail east of Los Ángeles. It was originally applied to the land grant at that place.

Duarte, a surname.

Las Flores (the flowers). At this place there was once a large Indian village, called in the native language ushmai, the place of roses, from ushla, rose.

Garvanza (chick-pea).

Hermosa (beautiful), is the name of a town in San Bernardino County, and of a beach in Los Ángeles County.

Indio, the Spanish word for “Indian,” is the name of a place in Riverside County, near Colton.

La Joya (the jewel).

Laguna (lagoon).

León (lion).

La Mirada (the view).

Los Molinos (the mills, or mill-stones), a name applied to a place east of San Gabriel by the Moraga party of 1819, who went out from the mission on a punitive expedition against the[81] Amajaba (Mojave) Indians. Padre Nuez, who accompanied the party, says: “On the return we passed by a place where there was plenty of water, below a hill of red stone, very suitable for mill-stones.” The same name, probably for similar reasons, was applied to other places in the state, among them one in Sonoma County, and Mill Creek in Tehama County, originally called El Río de los Molinos (The River of the Mill-stones).

Montalvo (a surname), the name of a place in Ventura County, near Ventura. This name is interesting as being the same as that borne by the author of Las Sergas de Esplandián, in which the fabulous island of California plays a leading part.

Murietta (a surname), the same as that of the noted bandit, Joaquín Murietta, who once terrorized California with his depredations. The town of Murietta, however, was not named in honor of this gentleman of unsavory memory, but for Mr. J. Murietta, who is still living in Southern California.

Los Nietos (literally “the grandchildren”), but in this case a surname, that of the Nieto family. Los Nietos was a land grant taken up by Manuel Nieto and José María Verdugo in 1784.

Pasadena, said to be derived from the Chippewa Indian language. The full name is said to be Weoquan Pasadena, and the meaning to be “Crown of the Valley.” Let no man believe in the absurd story that it means “Pass of Eden.”

Prado (meadow). “The Prado” is also the name of a famous promenade in the city of Madrid.

Puente (bridge), in Los Ángeles County, was taken from the name of the land grant, Rancho de la Puente.

Pulgas Creek (fleas creek).

Redondo Beach (round beach), a well-known seaside resort near Los Ángeles, is usually supposed to have received its name from the curved line of the shore there, but the fact that a land grant occupying that identical spot was called Sausal Redondo (round willow-grove), from a clump of willows growing there accounts for its name.

Rivera (river, stream). Rivera was also the name of a pioneer family.

Rodéo de las Aguas (gathering of the waters), a name once given to the present site of La Brea Rancho, near Los Ángeles, perhaps because there is at that point a natural amphitheatre which[83] receives the greater portion of the waters flowing from the neighboring mountains and the Cahuenga Pass.

San Clemente (St. Clement), the name of the island fifteen miles south of Santa Catalina. The saint for whom this island was named “was condemned to be cast into the sea bound to an anchor. But when the Christians prayed, the waters were driven back for three miles, and they saw a ruined temple which the sea had covered, and in it was found the body of the saint, with the anchor round his neck. For many years, at the anniversary of his death, the sea retreated for seven days, and pilgrimages were made to this submarine tomb.”—(Stories of the Saints.)

San Jacinto (St. Hyacinth), was a Silesian nobleman who became a monk, and was noted for his intellectual superiority, as well as for his piety. San Jacinto is the name of a town in Riverside County, thirty miles southeast of Riverside, in the fruit region, and of the range of mountains in the same county.

San Juan Point (St. John Point).

San Matéo Point (St. Matthew Point).

San Onofre (St. Onophrius), was a hermit saint[84] whose chief claim to sanctity seems to have been that he deprived himself of all the comforts of life and lived for sixty years in the desert, “during which time he never uttered a word except in prayer, nor saw a human face.”

San Pedro (St. Peter), is on San Pedro bay, twenty-six miles south of Los Ángeles. St. Peter, the fisherman apostle and companion of St. Paul, is usually represented as the custodian of the keys of Heaven and Hell, one key being of gold and the other of iron. “There is a legend that the Gentiles shaved his head in mockery, and that from this originated the tonsure of the priests.” Peter suffered martyrdom by crucifixion, “but traditions disagree in regard to the place where he suffered.” The name Peter is said to signify “a rock.” “Thou art Peter, on this rock have I founded My church.”—(Matthew, 16, 18.)

Saticoy was the name of a former Chumash Indian village on the lower part of Santa Paula River, in Ventura County, about eight miles from the sea. The present town of Saticoy is on the Santa Clara River, in Ventura County, near Ventura.

Serra (a surname), probably given in honor of the celebrated founder of the California missions.

El Toro (the bull).

Trabuco Canyon (literally blunderbuss canyon), from trabuco, a short, wide-mouthed gun formerly used by the Spaniards, although this may not be the true derivation of the name in this case. One writer has translated this name as “land much tumbled about,” but where he obtained such a meaning remains an impenetrable mystery. Trabuco may be a surname here.

Valle Verde (green valley), incorrectly spelled on the map as Val Verde.

Valle Vista (valley view), is in Riverside County, five miles northwest of San Jacinto. This name is modern and incorrect in construction.

Verdugo was named for the Verdugo family, the owners of the Rancho San Rafael, northeast of Los Ángeles and near the base of the Verdugo mountains. José María Verdugo was one of the grantees of the Nietos grant in 1784.

Vicente Point (Point Vincent). This point was named in 1793 by George Vancouver, the English explorer, in honor of Friar Vicente Santa María, “one of the reverend fathers of the mission of Buena Ventura.”