Title: Harper's Round Table, December 22, 1896

Author: Various

Release date: August 25, 2019 [eBook #60172]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Annie R. McGuire

Copyright, 1896, by Harper & Brothers. All Rights Reserved.

| published weekly. | NEW YORK, TUESDAY, DECEMBER 22, 1896. | five cents a copy. |

| vol. xviii.—no. 895. | two dollars a year. |

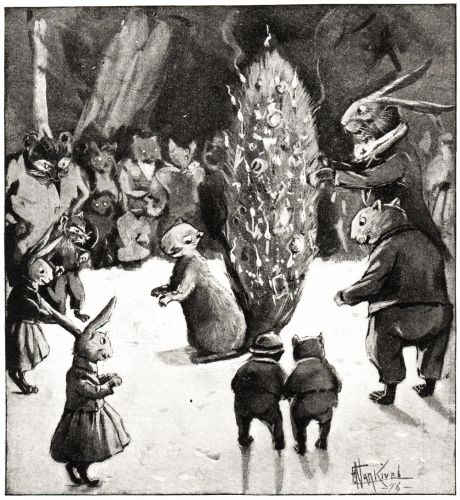

Two days before Christmas John Henry sat on the top rail of the fence which separated the seven-acre lot from the oat-field. There were five rails in the fence, on account of two cows addicted to jumping being kept in the seven-acre lot, and consequently John Henry was perched at quite a dizzy height from the ground. His mother would have been exceedingly nervous had she seen him there. He was her only child; his two older brothers had died in infancy; he had himself been very delicate, and it had been hard work to rear him. The neighbors said that Martha Anne Lewis had brought up John Henry wrapped in cotton-wool under a glass shade, and that she believed him to be both sugar and salt as far as sun and rain were concerned. "Never lets him go out in the hot sun without an umbrella," said they, "and never lets him out at all on a rainy day—always keeps him at home, flattening his nose against the window-pane."

Poor John Henry's mother was afraid to have him climb trees or coast down hill, and he might never have enjoyed these boyish sports had it not been for his father. When he was quite small, his father took him out in the pine woods and taught him how to climb a tall tree.

"Don't you be afraid, sonny. A boy can't live in this world and not be picked on unless he can climb."

John Henry went to the top of the tree in triumph, and when his mother turned pale at the recital, his father only laughed.

"I'd have caught him if he'd fallen, Martha Anne," he said; "and John Henry has got to climb a tree, unless you want to set him up for a girl and done with it."

However, Mrs. Lewis stipulated that John Henry should not climb unless his father was with him, and also that he should not go coasting without him. The result was that until John Henry was twelve he had had very few boy-mates. He went to the district school, but that was only a quarter of a mile from his home, and he did not have to carry his dinner, and he always came straight home, because his mother was so anxious if he was late.

"Better humor your mother, sonny, and not stay to play with the boys, she gets so worried," his father told him.

So John Henry always trudged faithfully home, in spite of cajoling shouts, and sometimes taunts about being tied to mother's apron-strings. However, the taunts were rather cautiously given; John Henry, mother's boy though he was, had still a pretty spirit of his own, and his small fists were harder than they looked. Once or twice there had been a scuffle, in which he had not been worsted. His mother had chided and wept over him on his return, and held anxious consultations with the teachers and the other boys' mothers, but John Henry had gained his firm footing in school, in spite of his pink face, his smooth hair, his little ruffled shirts, and the cake and sugared doughnuts which he brought to eat at recess. None of the other boys brought such luncheons; indeed, the most of them were dependent upon spruce gum and the cores of their friends' apples, and none of them wore such fine clothes.

It was quite a grief to Mrs. Lewis that she could not exercise as much taste upon a son's personal adornment as she could have done upon a daughter's, but she did all she was able. John Henry wore ruffled shirts, and carried hem-stitched pocket-handkerchiefs, his mittens were knitted in fancy stitches, and he had little slippers with roses embroidered on the toes to wear in the house. She also feather-stitched his blue-jean overalls.

John Henry's father, who was a farmer, insisted that his son should learn to work on the farm, and his mother, though she would have preferred to have had him in the house with her making quilts and pin-cushions, had to consent. Every day John Henry was arrayed in overalls, and did his task in field and garden; but his mother feather-stitched the overalls with white linen thread, though all the neighbors laughed, and John Henry was privately ashamed of them. However, his father bade him humor poor mother, and he never objected to the decoration. John Henry wore the overalls now, for he had been working with his father all the morning. There was no school all the next week, on account of Christmas holidays. It was only a half-hour before noon—John Henry's father had sent him home, lest his mother should think he was working too long, and the boy had sat down on the fence to take an observation on the way. John Henry was rather given to pauses for reflection and observation upon his little way of life.

Although it was late in December, the day was quite mild; there was a warm haze in the horizon distances, and the wind blew in soft puffs from the south. John Henry had taken his jacket off—it lay on the ground beside the fence. He shrugged his blue-jean knees up to his chin, clasped his hands around them, and stared ahead with blue reflective eyes. He did not see a boy coming across the field; he did not even hear him whistle, though it was a loud pipe of "Marching through Georgia." He did not notice him until he had reached the fence and hailed with a gruff "Hullo!" Then he looked down and saw Jim Mills.

"Hullo!" responded John Henry.

Jim Mills was carrying a sack of potatoes; he let it slip to the ground, and leaned against the fence with a sigh.

"Heavy?" inquired John Henry.

"Try it an' see."

"Where did you bring it from?"

"Thatcher's. Thought I'd come across lots, 'cause it was shorter. Where you been?"

"Been workin' in the wood-lot."

Jim Mills looked mournfully at the potato-sack. "I've got to be goin'," said he. "Mother wants these for dinner."

John Henry jumped down from the fence and gave the sack a manful tug from the ground. "I'll carry it as far as my house," said he.

"You can't."

"Can, too."

The two boys moved on across the old plough ridges of the field, John Henry a little in the rear, swung sideways by the potato-bag like a ship by its anchor.

"Going to the tree Tuesday night?" he panted, presently.

"Ketch me!" responded Jim Mills, surlily.

"Why ain't you going?"

"What would I be going for, I'd like to know?"

"There's going to be a Christmas tree, an' you'll have something."

"What'll I have?" demanded Jim Mills, fiercely.

He turned around in the cart path and faced John Henry. He was a thin boy, very small for his age, with a fringe of pale hair blowing under his old cap, over big gray eyes sunken in pathetic hollows. Many people thought that Jim Mills looked as if he did not have enough to eat.

"What d'yer s'pose I had last year?" asked he.

John Henry shook his head.

"Well, I'll tell you. I had a candy-bag and an orange and a girl's book from the teacher. She said she was sorry there wasn't enough boys' books to go round. When I got home I gave the candy-bag to the baby, and the orange to little Hattie and 'Melia, and 'Liza Ann she had the book. I ain't going to any more Christmas trees."

"Maybe you'll get something more this year," ventured John Henry, feebly.

"Where'll I get it? Tell me that, will you? Father an' mother can't give me anything. There's nobody but the teacher. Reckon I'll get another girl's book from her, an' then I'll have the candy-bag an' the orange, same as all the others, out of the school money. What would you think, John Henry Lewis, if that was all you was goin' to have?"

John Henry shook his head vaguely.

"Guess you wouldn't go to the Christmas tree any more than some other folks," said Jim Mills. "There you've got your father and your mother, and your uncle Joe and your aunt Jane, and your aunt Louisa and your grandfather and grandmother Lewis and your grandmother Atkins, to bring presents to the tree for you. How'd you feel if you had to go there and hark for your name to be called, and hear it: 'John Henry Lewis'—then you march out before 'em all and git a little candy-bag; 'John Henry Lewis'—then you march out and get an orange; 'John Henry Lewis'—then you march out and get a girl's book, and all of them things that everybody else has? Guess you'd be ashamed to go to Christmas trees as much as me. If your folks be poor and can't have things, I guess you don't want to tell of it before everybody."

Jim Mills turned about and went on with a defiant stride; John Henry followed, tugging the potato-sack. When the boys reached the house his mother called out of the window to set it down directly, he would lame his shoulders, and Jim Mills flushed all over his little pinched face.

"Told you it was too heavy for you," he muttered.

"It's as light as a feather, mother," called John Henry.

He ran around to the wood-shed and got a little wheelbarrow and loaded the potato-sack into that.

"There! you can carry it easier this way," he said; and Jim Mills trundled off, without any thanks save an acquiescent grunt. Jim Mills had so few favors shown him that sometimes they seemed to awaken within him an indignant surprise, instead of gratitude.

John Henry was so abstracted during dinner that his mother feared he was ill, and wished him to take some tincture of rhubarb. After dinner he went out in the barn, and curled himself up in the hay-mow to think. During the next two days he seemed to be in a brown study. Monday, the day before Christmas, Jim Mills[Pg 179] brought the wheelbarrow home, and John Henry beckoned him into the barn.

"Look here, Jim; you'd better go to that tree to-morrow night."

"What for, I'd like to know?"

"Oh, 'cause you'd better."

"Why had I better? I ain't going to tramp half a mile to that old school-house to get a candy-bag and an orange and a girl's book."

"Say, Jim, you go."

"What for?"

"Oh, something," replied John Henry, mysteriously and evasively.

Jim Mills's gray eyes took on a sudden sharpness. "What d'yer mean?"

"Oh, nothing. I rather guess you'll get something more this time, though."

"Say what you heard, John Henry Lewis!" Jim Mills questioned, eagerly.

"I didn't say I'd heard anything. You just better go to the Christmas tree, though; if you don't, you'll be sorry."

"You're fooling?"

"No, I ain't fooling!"

Finally Jim Mills agreed to go to the Christmas tree; in fact, John Henry made him promise solemnly, though he would not give his reason. However, Jim Mills went home in a state of bewildered expectation and elation. He was finally convinced that somebody was going to hang something fine on the Christmas tree for him, that John Henry knew it, and had promised not to tell. The tree was to be in the district school-house. All Tuesday afternoon John Henry, with some other boys and girls, worked hard decorating the school-house with evergreen. The tree had been set up in the morning, and people had begun to bring the presents; the teacher and some of the older girls were tying them on. Now and then John Henry made a détour in that direction, and peeped furtively. Before he went home he made quite sure that all the presents which he expected were there. He counted them over as he trudged home over the moonlit snow-crust. A deep snow had fallen on Sunday, and so averted the danger of a green Christmas. The moon was full, and considerably above the horizon, though it was still early. John Henry hurried, for he had much to do.

Supper was all ready when he reached home, and he ate it so hastily that his mother was afraid he would have indigestion. After supper he went up to his room and put on his best clothes, which his mother had laid out on the bed for him. Then he watched his chance—standing at the head of the stairs, and making sure that the doors below were shut—of stealing softly down and out of the front door.

It was about an hour before the time set for the Christmas festivities. He sped along through the moonlight. Twice he saw some one coming far down the road, and slunk to the cover of a bush, like a rabbit. One man went crunching past without a pause, but the other stopped when he neared the bush, and stared about him incredulously.

"I swan, I thought I see somebody ahead here," John Henry heard him say. He hugged close to the shadow of the bush until the squeaking crunch of the man's footsteps were out of hearing, then he came out and ran for the school-house, which was not far distant.

The windows were quite dark, and the door was locked. John Henry, however, was not dependent upon a door; he raised a window, and climbed in easily enough. The little interior was full of the spicy fragrance of evergreen, which had also a subtle festive suggestiveness. John Henry stole across to the desk, took a match from his pocket, and lighted a lamp, and then the tree blazed out. It was a fine tall tree, festooned with garlands of pop-corn, and grafted, as it were, into splendid and various fruit bearing. John Henry was not long in the school-house. He had brought a lead-pencil and rubber, and had noted the exact hanging places of his presents. It was barely ten minutes before the windows were again dark and John Henry was hurrying home.

His mother, who was very busy putting on a new brown cashmere dress, and his father, who was shaving, had not missed him. He stole in quietly, and sat down by the sitting-room stove. He was elated, but he had some misgivings. He was quite sure of his good motives, and yet there was a little sense of guilt.

When at length he started again, with his father and mother, he was very quiet. His mother asked him two or three times on the way if he did not feel well, and pulled his scarf more closely around his neck.

The district school-house was packed that evening; all the scholars and their families had come. Jim Mills was already there when John Henry entered, and rolled his eyes about at him with a curious expression of mingled hope and doubt.

Poor Jim Mills turned pale when the distribution of gifts began, and listened intently, every nerve strained, for his own name. He had not long to wait. He went down the aisle, his knees shaking, and received—not an orange, not a candy-bag, not the girl's book, of which he had still a bitter suspicion, but a parcel which at the first touch he knew, with a bewilderment of rapture, to contain skates. He had scarcely reached his seat before his name was called again, and forth he went for the second time, and was given a jack-knife with many blades. Then he went up to receive a top, then a boy's book, then another boy's book, then a pair of beautiful red mittens, then a sled. Jim Mills started up at the sound of his name and traversed the school-room until everybody stared, and the teacher began to look puzzled and anxious. She consulted with the committee-man who was distributing the presents, and his wife, who had been helping her that afternoon. Then she went to John Henry's father and mother, and one of his aunts who was there, and they all whispered together. Finally she bent over Jim Mills and whispered to him, and he immediately crooked his arm around his face, leaned forward upon his desk, and began to cry. He was a nervous boy; he had not eaten much that day, and the fall from such an unwonted height of joyful possession was a hard one.

"You must tell me the truth, Jim Mills," the teacher whispered, sharply.

"I—didn't," responded Jim Mills, with a painful cry, as if she had struck him.

"If you did come in here while we were gone and mark John Henry Lewis's presents over for yourself, tell me at once, if you do not want to be very severely punished," said the teacher, quite aloud.

Jim Mills did not repeat his denial; he only gave a great heaving sob. The scholars stood up in their seats to see.

"What a wicked boy!" exclaimed a woman near John Henry.

"He ought to be put in jail," returned another.

"He didn't do it!" John Henry cried out, wildly.

"He must have," said the first woman.

"Yes; you're a real good boy to stand up for him, but he must have," agreed the second woman.

"I tell you he didn't!" almost screamed John Henry; but they paid no more attention. He called the teacher, waving his arms frantically, but she was still busy with Jim Mills, and did not hear or see him. He tried to get up the aisle to her, but it was now blocked. He could not reach his father and mother for the same reason.

Finally John Henry Lewis made a desperate plunge down the aisle, and into the middle of the floor beside the tree. He raised his hand, and everybody stared at him. He was very pale, and his voice almost failed him, but he persisted in the first speech of his life.

"I did it," said he. "He mustn't be blamed. He didn't know anything about it. I told him he'd better come to-night, 'cause he'd get something nice, but that was all he knew about it. All he had last Christmas was an orange and a candy-bag and a girl's book, and he wasn't coming again. I had all the presents and he didn't have anything, and so I swapped. He ain't the one to be blamed; I am."

John Henry, pretty little mother's boy that he was, stood before them all, tingling with the rare shame of a generous action, meeting the astonished faces with the courage of one who invites punishment for guilt.

There was a pause—some one said afterwards that there were five minutes during which you might have heard a pin drop—then a woman caught her breath with something like a sob, and the teacher spoke.

"You may go to your seat, John Henry," said she.

After the Christmas tree that night there was great speculation as to whether Jim Mills would be allowed to keep John Henry Lewis's presents, and as to what John Henry's folks would say to him.

It was ascertained beyond doubt that Jim Mills did keep the presents, and it was reported that all John Henry's father said to him was that in future he mustn't lay his plans to do anything like that without telling his folks about it. As for John Henry's mother, she and his grandmother Atkins bought him a little silver watch for a New-Year's present, because they felt uneasy about letting him sacrifice quite so much. His grandmother, who was superstitious, said that John Henry had always been delicate, and she was afraid it was a bad sign.

Here's Christmas at the door again!

There's never a day so dear,

Nor one we are half so glad to see,

In the course of the whole round year.

It isn't that Santa Claus comes back,

And his hands with gifts are full;

It isn't that we have holidays,

When we need not go to school.

But the air is thrilled with happiness,

The crowds go up and down,

And people laugh and shout for joy

When Christmas comes to town.

There's nobody left to stand outside,

The world is bright with cheer,

For Christmas-time is the merriest time

In the whole of the big round year.

We try to love our enemies now,

And our friends we love the more,

That strife and anger fade away

When Christmas taps at the door.

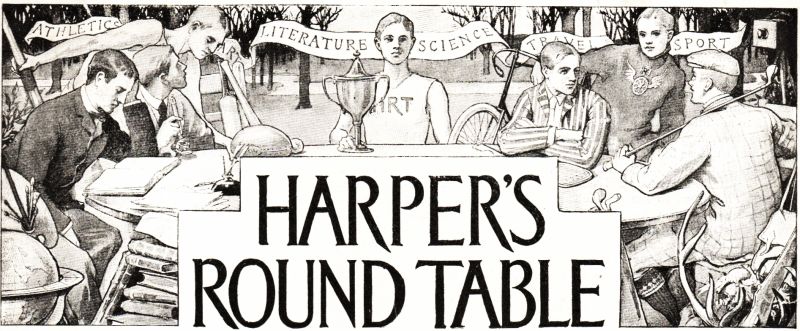

CLEMENT C. MOORE.

CLEMENT C. MOORE.

The author of the famous poem that recounts in such graphic language "The Visit of St. Nicholas" was born in the city of New York, July 15, 1779. His boyhood was passed at the country-seat of his father, called Chelsea, then far remote from the city, but now a very thickly settled portion of it, and embracing a large tract in the vicinity of Ninth Avenue and Twenty-third Street.

Dr. Moore received his early education in Latin and Greek from his father, the venerable Bishop of New York, and in 1798 he graduated from Columbia College. He devoted himself to the study of the Hebrew language, and the result of his labors appeared in the form of a Hebrew and English Lexicon, which was published in 1809, and he was thus the pioneer in the work of Hebrew lexicography. In 1821 Dr. Moore was made Professor of Biblical Learning in the General Theological Seminary of the Episcopal Church. From his magnificent estate he donated to the Episcopal Church the tract on Ninth Avenue between Twentieth and Twenty-first streets, and the Theological Seminary there erected is a lasting monument to his liberality and devotion to the sacred cause.

In the intervals between the time devoted to more serious studies his principal amusement was writing short poems for the amusement of his children, and among them was "The Visit of St. Nicholas," which was written for them as a Christmas gift about 1840. The idea, he states, was derived from an ancient legend, which was related to him by an old Dutchman who lived near his father's home, and told him the story when a boy.

In those days every young lady was supposed to have an "album," and a relative who was visiting the family quickly transferred the verses to hers. They were first published, much to the surprise of the author, in a newspaper printed in Troy. They attracted immediate attention, and were copied and recopied in newspapers and periodicals all over the country. An illustrated edition, in book form, was published about 1850, and since then School Readers have made them familiar to generation after generation of children. They have been translated into foreign languages, and a learned editor informed us of his delight and surprise when travelling in Germany to hear them recited by a little girl in her own native tongue.

After a long life of honor and usefulness, Dr. Moore died, at his summer residence in New York, July 10, 1863. For him may be claimed the peculiar distinction of being the author of the two extremes of literature—learned works on ancient languages for profound scholars, and Christmas verses for little children. The learned works, upon which he spent years of constant labor, have been superseded by works of still greater research, but the man is yet to be born who can write anything to supersede the little poem that has made Santa Claus and his tiny reindeer a living reality to thousands of children throughout our broad land.

REDUCED FAC-SIMILE OF THE MANUSCRIPT OF DR. MOORE'S

FAMOUS POEM.

REDUCED FAC-SIMILE OF THE MANUSCRIPT OF DR. MOORE'S

FAMOUS POEM.

The little Mystery was lying off the pier at Martinez's. Night had covered sail-boat and row-boat alike, and while all Potosi gathered towards the front celebrating Christmas eve with the rockets and the fire-crackers that are not once thought of on the Fourth of July, Mr. Martinez and Bascom were silently carrying bags of gold on board the Mystery. As the sails ran up in the snapping cold, the mournful cry of her ropes was the only sound on the Back Bay, and it smote Bascom; and Mr. Martinez's grasp and his whispered cautions to Captain Tony, and the solemn gold that he had carried, weighed upon his heart as they put out.

Everything had been arranged on the deck for mounting the one which was best preserved of the six mysterious old cannon that he had found the summer before sunk in Potomoc Bay. It had been left covered by tarpaulins in a row-boat off Captain Tony's point, where they could get it as they passed. They ran the schooner across from Mr. Martinez's to the point, and neither of them spoke along the way. When they reached the boat, Bascom sprang over into it and lifted off the tarpaulins. There was nothing underneath.

"The cannon's gone," he whispered. "What does it mean?"

"Somebody playin' a joke to spoil our fun," said the Captain, and the darkness hid the worried frown upon his face. "Yo' mus' go ashore an' look for it; bud doan' be long."

"Looks like it's too funny for a joke," said Bascom, "less'n it's one of ole Captain Aristide's. I never heard of his playin' one, only he was along here to-day when I was a-polishin' the gun, an' he seemed mighty interested. It kind o' shivered me, but I went on sweet an' innocent about our keepin' Christmas, firin' in the channel."

"Aristide?" repeated Captain Tony, and he crossed his arms on the tiller and pulled his hat down over his eyes, and thought, while Bascom rowed ashore. Captain Aristide Lorat was known by every one to be the craftiest man along the coast. His neighbors had never guessed that in his free and gallant youth he had been a pirate neither more nor less. He was too old now to enjoy the personal risk of such enterprises, and he gave his direct attention to a prosaic carrying trade; but his old preferences survived in the form of a few boats which did whatever smuggling or wrecking came in their way. They were seldom seen in Pontomoc Bay, and had never been recognized in their true character nor connected with Captain Lorat, and yet Captain Tony did not like to think that old Aristide had been nosing in their affairs. For it was something unusual that was taking the Mystery out on Christmas eve.

Mr. Martinez, the owner of the great canning-factory for which Captain Tony and Bascom sailed, was the chief of a quiet organization of Cubans who were wealthy enough to make their patriotism of substantial disadvantage to Spain. Just now, in one of the frequent insurrections, there had been an unexpected call on the society for aid. A Cuban boat was secretly coasting off Horn Island, waiting their messenger, for this was at a time when the United States was not much inclined towards sympathy. Martinez had two reasons for sending Captain Tony out to it. Tony was infallibly prudent and brave, and he was trustworthy, both from the integrity of character which made him dislike the mission, and from an indebtedness to his employer which forbade his refusing it. Mr. Martinez had given them the Mystery.

"They made a clean job," whispered Bascom, coming back. "They've taken that and the two next best out'n the shed where I was polishin' them. It must have been Captain Aristide. Has he any grudge agin us?"

"None dat I know of," the Captain said; "an' we can't stop an' study 'boud it now. It is of mo' impo'tance dat we do ouah wo'k dan dat we fire guns, even to say dat it is done." Captain Tony's regret at taking Bascom out on a holiday had suggested carrying the best cannon along and firing it, for Bascom had been putting all his savings into ammunition and fireworks for Christmas. Mr. Martinez approved, thinking a water celebration would help to explain their going, and they were to fire him a reassurance when they went through Potosi Channel on their way to the oyster-beds when their mission had been carried out.

The actual fact of the case was that Captain Lorat needed no more than the knowledge that a boat was going out. Other bits of knowledge gained from other sources only required this to piece them to a whole. He decided it would be better not to let Bascom have a gun on board, and while the Mystery was taking her cargo at Martinez's pier, he had all of them that looked as if they might be used loaded upon a schooner that had come into the bay since dark.

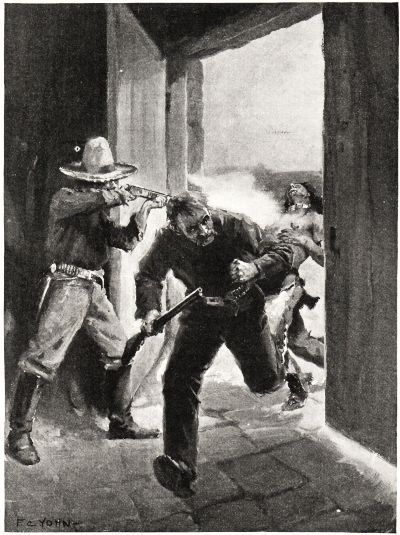

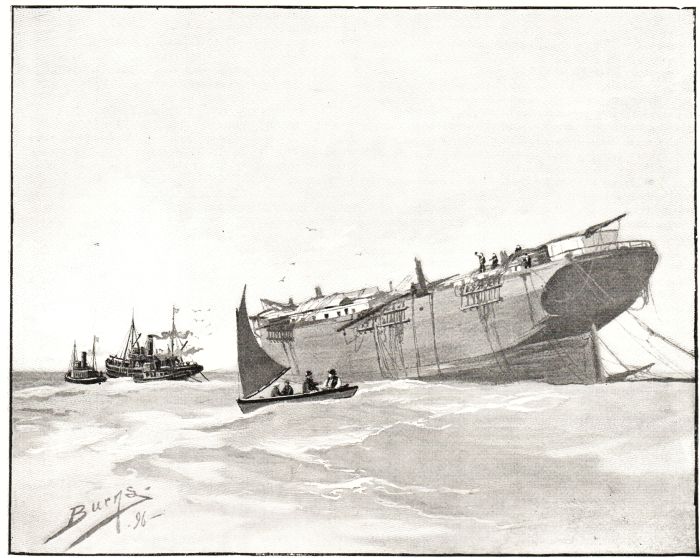

ONE OF THE MEN JUMPED ON BOARD AND GRAPPLED WITH THE

CAPTAIN.

ONE OF THE MEN JUMPED ON BOARD AND GRAPPLED WITH THE

CAPTAIN.

Toward three in the morning Bascom found his eyelids growing so heavy that he could scarcely keep from drowsing against the mast in the snug warm lee of the sail. The Mystery was just about to round the Horn when a row-boat load of men swished past her bows. Bascom drew himself together and sprang swiftly to the rail. One of the men was already climbing up the side, but he jumped on board and grappled with the Captain. There was a volley of shots, and the Captain dodged into the cabin, where the gold was stowed. The men swarmed up over the deck. For a moment Bascom had thought they were the Cubans, but now he caught up one of his rockets, lighted it, and held it steady while it rose. The Cuban boat must surely be waiting round the point of the island, and it would see the signal. A man leaped round the mast and knocked him down, but as Bascom rolled over to the rail he saw the rocket singing up to break in scintillating brightness through the night. He wriggled like a cat to the stern and dropped down the hatchway. He pulled the hatches shut, but there was a rush of feet along the deck, and the blade of the anchor came crashing through the cabin-top. Bascom threw himself into a bunk, and before the Captain, who was reloading in a corner, could close his revolver and lift it, the roof was torn from over them; three men poured in, seized the Captain and Bascom, bound them both, and carried off the gold. The lantern hung battered, but its light was not out, and the prisoners looked at each other in despair.

"Reckon I give it to dem better dan I got," he said, "bud I'm t'inkin' 'boud how we can catch dem again an' take ouah money back."

"I'm kind of expectin' comp'ny," said Bascom. "Them Cubans is dumber'n I take 'em for if they don't mosey up to see what my rocket meant. I fired one just as you dodged in the cabin."

"Dere is one question," Captain Tony said. "Get yo'se'f close an' tuhn a little so I can take a bite at dat rope. Yo' signal may have attrac' de government cruiser dat's lyin' off Ship Islan'."

"Oh!" said Bascom. "Well, we got a lot of time before they can steam over." He rolled himself against the Captain, who craned his neck forward and worked with his strong creole teeth at the knots. He was still pulling at them when feet were heard scrambling to the deck again, and two men looked in at the shattered hatch. They spoke to Captain Tony in Spanish, of which Bascom only recognized the pass-word that Mr. Martinez had given them.

"Dey come to yo' rocket," the Captain translated while the men unbound them, "an' dey was in time to see de boat put off from de Mystery, so de Cuban schooner has gone after dem, sendin' dese two men in a skiff here."

"Which way've the scalawags gone?" inquired Bascom, jumping to his feet.

"De way dey had to," answered the Captain, hurrying to the deck. "Dey reach deir schooner, an' as de Cubans was comin' from outside, dey had to put in. We'll be ovah-haulin' dem; dese men say de Cuban boat is as good at chasin' as she is at showing her heels. We goin' along too. Reckon yo' has to tek de tiller," he added, and he stood by, with his arm wrapped in a piece of canvas for a sling, and laid the course. Ahead of them they could just see the Cuban boat plying back and forth with a long tack and a short tack, and the Mystery turned eastward. The Cuban boat could not trust herself far inland where she did not know the channels, and the smugglers would take their first opportunity to make a sudden run east into one of the[Pg 183] bayous; and Captain Tony determined that the Mystery should cut them off. It was a hare-and-hounds chase, and the hours passed among the stars while the three boats doubled and redoubled at top speed, gaining on one tack, losing on the next. Pale clouds began to drift across the sky, and there was a taste of morning in the wind. The Captain slapped Bascom on the back. "Yo' boy," he chuckled, "dat Cuban boat is de stuff! She's run dem down so fine dat dey's headin' 'cross de shoals, an' dey boun' to stay dere an' wait faw us, by my reckonin'."

Bascom giggled, but the Captain whistled in a new tone. "W'at in de name of reason!" he exclaimed; "dey tu'nin' back across de Cuban's course? Oh ho!"

A cloud of smoke went up, and there was a great rumbling hoarse report such as had not been heard in those waters since the war. "Dey firin'!" the Captain gasped. The sound vibrated among the waves and sank away, and the smoke cleared. The Cuban was not hurt. She turned like a girl courtesying, and a sharper shot came caracoling on the waves, this time from her.

"De mad folly!" shouted the Captain. "Dey wan' to raise de dead, let alone all de cruisers on de coas'!"

Bascom danced at the tiller. He was quivering with his first thrill of war—not only war between the Cubans and the smugglers, but soon with the United States. Over their shoulders he could see the faint line of a cruiser's smoke against the west. The Captain was looking very grave. "Dis'll be de darkes' day de Mystery seen yet," he said. "I 'ain't nevah liked dis job, me, bud it look like we couldn' refuse."

"One thing for the firing," said Bascom, "it's Christmas mornin'."

"Christmas gift," said the Captain, grimly. "Reckon de smugglers is sayin' it! Dey los' a mas' by dat las' shot."

"Christmas—" ejaculated Bascom, and stopped short as the whistle of the wind in the rigging was drowned again by a terrific explosion that shook the sea. As they peered out under the smoke, something dropped like a spent ball on the deck. The Captain picked it up, and after a moment's scrutiny passed it over to Bascom. It was an unmistakable fragment from the muzzle of one of Bascom's guns. The peculiar alloy that was neither brass nor bronze, and that had puzzled every one when the guns were raised, left no opening for doubt.

"Golly," said Bascom, "rather bust than shoot agin its frien's!" He stroked the powder-smelling piece against his cheek and almost kissed it for delight.

The Captain noted the growing trail of smoke in the west and spoke to the two Cubans. One of them pointed at the smugglers' schooner. She was settling fast, and the men on board of her were raising a white flag. The Mystery and the Cuban boat answered the signal, and the three Captains met on board the Mystery to make terms.

The smuggler Captain was a tall, pleasant-faced American of Scotch descent, with a wounded cheek and big fierce-looking mustaches. "I've got the best of myself so bad," he declared, "that you can say what you want, but it'll not be to your advantage to leave my schooner standing on the edge of the bar to tell tales; so what I propose is this: I'll give you back your scads without any more fuss if you'll tow what's left of her into Davis Bayou out of sight and give us permission to skip."

The Cuban Captain declined to do this, and it was finally decided that while the Mystery beat back and forth in the sound, the Cuban should tow the smugglers out of danger and then make good her own escape.

Bascom went across in the tender with the other skiffs to get his guns. "Your boss is grit, ain't he?" said the smuggler Captain as they pulled through the white foam on the bar. "I reckoned on an ordinary skeery creole, but the way things has turned out, it's good I reckoned wrong."

"It would have been gooder for you if you hadn't reckoned on my guns," said Bascom, getting aboard the wreck, among a demoralized crew, and laying his hand on the only piece he saw. "What's gone with the first one? How did you know about 'em, anyhow?"

The Captain preluded his answer with a fair volley of imprecations. "And I wish the fiends had taken 'em before they ever fouled my deck," he finished. "I didn't count on firin' 'em; I jus' took 'em to keep you from makin' a noise, but I brought along your ammunition for prudence an' knowin' it would come handy some day, an' when I was close put I jus' let 'em holler. First one broke loose an' jumped into the water, shootin' at kingdom come, an' the nex' busted an' busted us, so I wish you joy of firin' this third."

"Joy?" said Bascom; "well, I rather guess!" It was the one he had planned for from the first, and which had been stolen from the row-boat. "You wasn't allowing that guns what's seen enough of life to know what side they're on would turn agin their frien's, was you? Just you listen an' you'll hear this one speakin' calm and pleasant when she gets on board the Mystery. And I'll give you this pointer," he added, from the boat to which the gun had been lowered, "next time you want to borrow something of mine, jus' remember that my things mos'ly has peculiar workin's, an' I can manage 'em best."

Half or three-quarters of an hour later, when every trace of the wreck was out of sight, and the sails of the Cuban boat were flitting innocently between Horn Island and the shore on the way east, the United States cruiser shone near at hand, trim and slender and dauntless in the sunrise.

"Well," said Captain Tony, as they watched her despatch an officer towards them in a boat, "it's jus' to brass it out now. We've got to do it faw Mr. Martinez. He'll be in mighty bad troubl' if our tale don't satisfy dat young chap comin' dere. Bud if it do, it's good enough faw ev'ybody else—even ole Aristide, although it will disturb him mo' dan he will say—if what we t'ink is true. Dis insurrection an' secret-service business may be all hones' faw de peopl' dat belongs to it, bud it cost me an' yo' an' de little Mystery mo' in small feelin' dan it pay, an' I say dis is de las' time faw enemy or frien'."

"Me too," cried Bascom, "an' the old gun thinks the same. They was dead down on this from the start, an' I reckon that's the word what they've waited so patient to get a chance to say."

The ship's boat drew alongside, and the officer came aboard to inquire, with the commander's compliments, why a little battered schooner was idling among the shoals in a norther, firing cannon.

Bascom and the Captain saluted together. "Christmas gifts," they cried.

"Usses had dese curious ole gun," the Captain explained, "w'at we raised out of de water las' yeah, an' dis boy has been waitin' evah since faw Christmas mornin' to fire 'em. An' I t'ought me dat it would be mo' safe to come out heah an' try dem before firin' in Potosi Channel, as was his wish. An' indeed it has prove dat I was right, for one of dem stepped right off into de water dat it come from, an' de nex' it busted, as you see," and he pointed to the cabin-top and to the bits of cannon that Bascom had gathered for keep-sakes from the sinking boat.

"Usses has been havin' a reg'lar party," Bascom added. "You are our most 'ristocratic callers, but you isn't our first. They'll be takin' the word of the guns clear to Mobile an' as far as you go, whichever way that is."

"Then this is one of the forgotten guns that were raised in Pontomoc Bay last summer?" the Lieutenant said. "I've heard of them." He examined the piece like a toy. He was a young man with straightforward clear eyes that commanded the same frankness they expressed, and had been very uncomfortable to meet until this open subject was reached. The Lieutenant saw Bascom's face light up with responsive enthusiasm, and he ran on: "It may have belonged to one of the old discoverers. Why, I can just see the old chaps that manned it when the ship went down, standing on tiptoe round it, with their swords clanking and their queer old clothes flapping in this very wind perhaps! You know I believe they would like it if we had the old veteran fire a salute."

"Usses would like that too," the Captain said.

Bascom had no answer. He looked across to the ship where the stars and stripes that had fought their way from so much ancient bravery were riding high in the gold sun-light and the wind. He looked until his eyes grew dim and the figure of the Lieutenant priming the cannon became[Pg 184] blurred so that all the shadowy old crew seemed to have marshalled themselves aboard the Mystery to man their gun. "Christmas gift," he murmured, and his heart came up into his throat. Then the voice of the gun rolled out, mellow and husky and peaceful after centuries of sleep.

The recoil went from stem to stern like a great thrill of joy. The smoke swept away on the wind, and the Lieutenant touched Bascom on the shoulder. There was an interval of silence, and then the man-of-war saluted the little Mystery.

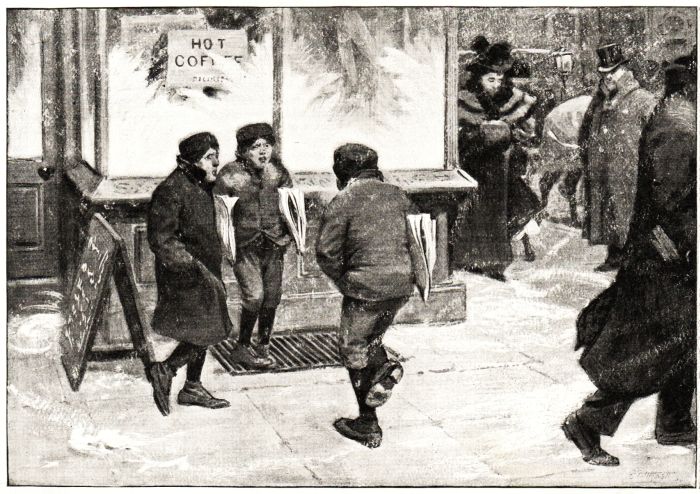

No one was stirring in the inn except a sleepy, draggle-headed pot-boy, lazily sweeping out the tap-room. Although I was very hungry, I determined on a ramble along the water-front before breakfast, and I headed down the street.

I remembered very well where I had landed from the Minetta, and that upon the occasion of her entering the harbor I had been surprised at the number of vessels at the wharves; but now they seemed to be trebled. A maze of masts and rigging arose above the tree-tops, but the scene lacked the life and movement of loading and unloading.

The vessels appeared slovenly and unkempt, their yards at all angles, and their shrouds sagging. Close to me, with a long bowsprit extending almost into the front yard of one of the white houses that clustered at the southern bend of the harbor, was a great three-masted ship. Her cut was different from most of those that I had seen, but what held my eye was this: her foremast had been spliced neatly with wrappings of great rope, and three or four jagged breaks showed in her topsides and bulwarks. She was lying close to a great warehouse that prevented a view of the open bay, and I walked down the pier. The great vessel had quarter-galleries, like a man-of-war, and above her rudder-post I read the words, "Northumberland of Liverpool"; then I remembered hearing the night before that this vessel had come in under the lee of the Young Eagle, and had been one of the richest fruits of her first cruise.

When I reached the pier-head I walked out on the string-piece, and climbing on the top of a pile of lumber, I looked out across the smooth water. A quarter of a mile from shore lay the tidiest-looking craft that I ever clapped my eyes on. She was not very small, but sat low in the water. A backward rake to her masts gave her a jaunty appearance, and the tall spars that lifted high above her deck looked as slender as whipstocks. Her jib-boom was of tremendous length, but at that time I did not know enough either to criticise or to appreciate her altogether at a glance.

It was setting out to be a scorching day. The smell of sperm-oil and pine timber came from beneath and about me, and so still was it that the sound of a man rowing a dory over against the farther shore sounded plainly. I could hear every thump in the thole-pins. The clicking of a block and tackle broke out, and a musical high-toned bell hurriedly struck the hour from the little brig. That she was the Young Eagle I had no doubt, and it flashed across me that maybe I had gotten myself in somewhat of a predicament, and that maybe it would be better for me to find Captain Temple and inform him that, while I did know something of small arms, I was in truth nothing of a sailor.

I took the paper out of my pocket, and saw that there[Pg 185] was no reference made to performing the duties of seamanship, but that I had been enlisted to instruct the crew in a branch with which I felt myself perfectly familiar.

My old friend Plummer had promised to help me learn the ropes, and so I determined to go ahead without any explaining.

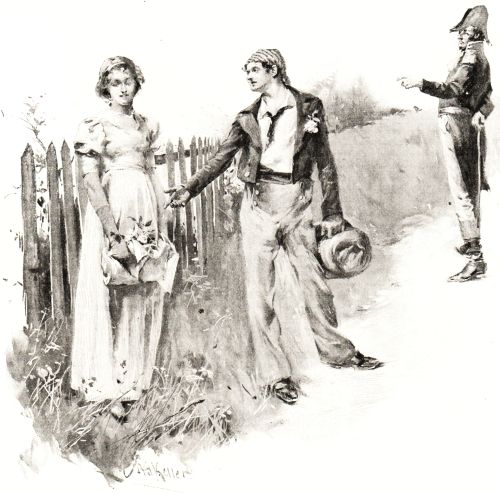

Thinking that it would be best to report to my commander at the inn and await his orders, I turned my footsteps back into the town. And as I walked the path along the tree-lined street, why I should fall to thinking of Mary Tanner I do not know. I took a squint down at myself in my sailor finery, and rather admired the way the wide bell-shaped trousers flapped about my ankles. The wish grew upon me that Mary could see me as I was. Thus, with my head down, I hastened on, and did not perceive that an open gate swung across the way until I had run afoul of it, bows on.

As I leaned over to rub my shin I heard a laugh, and looking up, there, not ten feet from me, was the very person who had been in my mind—Mary Tanner herself! The power is given to women to control the expressions of their feelings in a manner that fails men altogether. At least I might say we are more clumsy at it. I was so astounded that I could not speak a word, and stood there on one leg like a startled sand-piper. She spoke first.

"Well, where did you come from?" she laughed, gathering up her apron in one hand. It had been filled with roses she had been clipping from a bush.

If the time had been longer since I had seen her, I think I might have been tempted to reply from China or some distant port, as her laughter galled me sharply. But as it was, I answered her somewhat falteringly, to be sure,

"From up there," pointing with my fingers toward the north.

"How did you get away from Gaston?" she asked.

At the mention of the old man's name I could not help but give a glance over my shoulder, at which Mary laughed and asked another question.

"Where did you get those outlandish clothes?"

"I'm a sailor," I replied, giving a hitch to my trousers.

"Oh no, you're not," said Mary, throwing back her head. "You're a boy."

"I wish you a good-morning, Mistress Tanner," I replied, making an effort to pull off the tight-fitting Portugee cap, and only succeeding in giving my hair a tweaking. "Good-morning, Mistress Tanner; time has not improved your manners."

I walked away, angry. It is no evidence of superior wisdom on my part to here make an observation; but six months of a town life will change a woman and teach her more than five years spent on a hill-side farm, and this is no falsehood. I had gone but a few rods when I heard my name called, and, looking back, I saw Mary leaning over the fence and beckoning to me with a rose in her fingers. Affecting a great deal of leisure, I retraced my steps.

"Are you really going to sea?" she asked.

Now although I could see how great the change had been that had come over her, this was spoken after the old manner; and despite the feeling that things were not exactly as they had been, I felt more at my ease.

"I'm one of the crew of the Young Eagle," I replied, and I must confess it, proudly.

"My!" was all Mary vouchsafed to this, but I noticed that her eyes brightened and that she flushed. The rose she had been holding fell from her hand, and I bent over and picked it up. As I offered to return it, she looked at me slyly.

"Why don't you keep it?" she asked.

"Because you have not given it to me."

"Then I will give you another."

As I took the flower she extended, an entirely new sensation thrilled me, and though this part of our short interview may be interesting or not, I am glad to set it down fully.

"Oh, I've got some news to tell," said Mary, looking at me archly.

"What is it?" I inquired. "Good news?"

"Yes; I may be rich some day, John."

"Rich!" I exclaimed. "How is that, pray tell me?"

"You see, my grandfather who lives in Canada was a[Pg 186] Tory," Mary answered. "His name is Middleton—one of the Irish Middletons—and when he left New London my mother would not go with him, for my father was an American soldier. Now my grandfather wishes me to come to him."

"Oh, are you going?" I asked, with my heart beating loudly.

"Well, I won't go now," Mary replied. "You see, my father is very ill here at my uncle's." A shade of sadness came into her voice. "He wants me to go," she continued, "but I won't leave him for any grandfather, no matter how rich he is."

"If you went, perhaps I would never see you again," I said faintly.

"Why," she answered, opening her eyes wide, "you could come and see me."

"When?"

"When you got command of your own ship." She smiled as she spoke.

"I'll have one some day," I spoke up bravely. "And that is what I'll do."

But an interruption came to this little dialogue.

"Look up the street," cried Mary, suddenly pointing.

I did so, and my heart fell. Here came the frightful old Gaston, shambling along, with his arms dangling in front of him; his clothes and head-gear were fit to make a ghost grin. But as if he had been a schoolmaster and I a truant schoolboy, I dodged through the gate and hid behind the rose-bush. For years I could not think of this action without chagrin, but now I could laugh at it.

"You had better not let him catch you," Mary observed, joining me, and we peered about the corner of the rose-bush until after Gaston had passed. That he was in quest of me there was no doubt, and I cannot help thinking that my evident fear amused Mary Tanner, for she stood there smiling at me, and pulling at a green branch over her head (oh, I can well recall how she looked!); but the scene was interrupted by the approach of a slight, quick-stepping man, who rattled a walking-stick along the fence-pickets as he came nearer.

"Here's Captain Temple," I said, straightening up. "Now you'll see whether I'm a sailor or not."

When the Captain was opposite the gate I stepped from behind the rose-bush and saluted.

"Heigh, oh!" he exclaimed, looking longer at Mary than he did at me. (She was a tall girl, and appeared older than her years.) "Heigh, oh, I'm just in time to rescue you, my lad. 'Tis plain you're a prize to beauty! Ay, and would fly her colors too," he added, pointing to the rose, which I had thrust in my bosom. As he spoke the officer bowed gallantly, and Mary dropped him a courtesy.

"Sorry, lad," Captain Temple went on, "but I may have use for you. Can you read and write?"

"Ay, ay, sir; French and English, and Latin too," I answered.

"Ecod! a scholar, eh?" was the return. "Scholars make bad sailors. But Bullard has gone to New London, and I would have somebody come to McCulough's office and help me with the papers. So bid good-by to your sweetheart, and come along—come along. We'll get under way to-morrow mayhap, or the day after."

"GOOD-BY, MARY," I SAID, EXTENDING MY HAND, "DON'T FORGET

ME."

"GOOD-BY, MARY," I SAID, EXTENDING MY HAND, "DON'T FORGET

ME."

"Good-by, Mary," said I, extending my hand. "Don't forget me."

"Good-by," she said simply, and thus we parted.

I was filled with the idea, as we went down the street, that I would run across Gaston; but I determined that if this happened, I should not show the fear of him that I had a few moments since. But we met no one except some villagers driving their cows to pasture, and approaching the wharves once more, we entered one of the warehouses, and found awaiting there a crowd of seamen. They all touched their hats as Captain Temple and I came to the doorway. A red-faced man with a great bulbous nose and snuff-powdered coat greeted us.

"You're late, Captain," he grumbled; "and look at the gentry that have been awaiting you. There may be some seamen amongst them, but I'll wager we've got some hog-butchers and tailors here, at any rate."

He might properly have added pirates in his category, for some of the men were as rough-looking cut-throats as any one might wish to see.

"Here, act as shipping-clerk, lad," said Captain Temple, shoving a great ledger toward me. "And set things down right and ship-shape, too, in plain English. Never mind the spelling—just so one can read it."

Luckily it happened that the page before was but half filled, and I saw at a rapid glance the mode of procedure. I recognized also Bullard's handwriting. And now began the examination that to me was most interesting.

Temple looked at every man, as he presented himself, slowly from top to toe, and I noticed that many of them gave a shake to their shoulders when he lowered his eyes, as if a chill had passed over them. The questions were very simple, consisting in asking the man's name, age, previous occupation, and the vessel that he had last sailed in, and if satisfactory, he was told to get his dunnage and present himself at the pier some time before noon.

"We have no idlers on board this ship," said the Captain, addressing the crowd. "If you're not doing one thing, you're doing something else. I want both-handed men about me."

In about two hours the work was finished, and Captain Temple, looking over the ledger, paid me a compliment upon my writing, and expressed the opinion that evidently I was an old hand; in which I did not contradict him. Before noon arrived, however, I was almost famished, but I had found no time to search for anything to eat.

It had got noised about the lower part of the town that the remaining part of the crew of the Young Eagle were to debark at that hour, and quite a crowd had gathered along the shore to see them off. I had managed to run up to the inn and to secure my small bundle, and had hastened back again.

Already a boat-load had gone off to the ship, and as I clambered down the rough ladder, the crowd and those in the second boat were indulging in much rough playfulness. It was a very mixed assembly, and there appeared to be no deep feelings shown in any of the farewells. Just as we shoved off, I heard my name called—that is, my first name. "John! John!" said a voice, and looking up, I saw Mary Tanner standing at the edge of the pier. She waved her hand to me, and then, with a quick glance about her, kissed it.

My return to this, which I kept repeating for fully a minute, was not conspicuous, because half of the men gathered in the stern-sheets were doing the same thing and indulging in mock-lamentations. Three or four silent ones, perhaps, felt more deeply than the others.

As we came alongside the brig, I noticed that her free-board was not more than six feet amidships, but that her bulwarks were fully the height of a man's shoulder. Her sides shone as if they had been varnished, and the brass-work along her rails gleamed like gold. But when I set my foot on deck, it was then that I was astonished. I have seen many privateers and vessels of the regular navy since that day, but never have I seen such a clean sweep of deck and such fine planking in my life. All the loose running-gear was flemished down neatly, many of the belaying-pins were of brass, and her broadside of six guns was very heavy for her tonnage.

Amidships, carefully lashed and blocked, was a long twelve-pounder. The others were eighteen-pound carronades. Two brass swivels she carried besides these—one on her forecastle, and one forward of the wheel on the quarter-deck. She was built upon a plan different from most of the vessels of that time, but now become more adopted in America. Instead of having her greatest breadth well forward, it was farther aft, and she was cut away like a knife-blade. I have never seen her equal in going close-hauled; or, in fact, in any point of sailing.

Now, as I stood there with my bundle in my hand, I longed for some one to ask questions of, and then I remembered that if we sailed on the morrow, Plummer would be left behind. Most of the men coming off shore had carried their hammocks with them, and where I was to get mine I did not know. But as Captain Temple had been so kind[Pg 187] to me on shore, I thought nothing of going to him, and considered that it would be the best way out of the difficulty, so I stepped up to where he was standing near the binnacle. He looked at me as if he had never seen me before; in fact, he appeared a totally different man.

"Well!" he said, sternly. "Coming aft in this fashion! If you wish to speak to me, wait at the mast."

"I have no hammock, sir," I began.

"Sleep on the deck, then," he returned. "Go forward."

He spoke to me much as one might address a dog, but there was nothing for me to do but to obey like one, and I went down the hatchway to the berth-deck. How so many men were going to sleep in that crowded space I could not see. They were so close that as they moved about they touched one another, and so low were the deck-beams that the tallest could not stand erect, and even I brought up against one with a tremendous whack that set starry skies before me. To my relief, I perceived that I was not the only greenhorn, and that there were a few others who knew even less than I did of what was expected of them.

A gawky country lad, who had been standing there gorming about open-mouthed, approached me.

"Tell me, please," he said, "where are our beds. Where are we going to sleep?"

I explained that the long bundles some of the men carried, and that they were taking up to stow in the nettings on the deck, were hammocks, and that he would probably have one served to him. He thanked me kindly, and probably looked upon me as being a very knowing, able seaman.

The men were joking and cursing roughly, and before we had been on board ten minutes a fight had started between two half-drunken sailors, which occasioned only merriment amongst the lookers-on, until a great, thick-set figure, that I afterwards learned was Edmundson, the third lieutenant, ran down the companion-ladder, and sent both of the fighters to the deck with two blows of his great fist.

"If you're after sore heads, you can get them!" he cried. "But avast this quarrelling." No one said a word; even the fighters stopped cursing.

I was mad for something to eat, for, as I have told, I had had nothing since the night before; but soon the word was passed through the forecastle that there would be no grub until the evening, at which there were many mutterings and more strange oaths. During the afternoon the crew was divided into watches, and the men were given their numbers and stations, but so far as I could see no provision was made for their comfort in any manner; no regular messes had been organized, and at six o'clock, when we were fed, we sat about in groups on the deck, and ate with our knives and fingers from the rough tubs; but the feed was wholesome, and there was plenty of it. I did full justice to a very healthy appetite.

Before dark Mr. Bullard came on board. As he walked forward I managed to catch his eye, and saluted.

"Ah, here's our sailor fencing-master," he half laughed.

"Might I have a word with you, sir?" I inquired.

"What is it?" he said, frowning.

"There are two country lads on board that have no hammocks; they know little of shipboard, but are willing. Can you not help them out, sir?"

I did not tell him that one of the country lads was myself. He muttered a curse, and here I found out that asking favors of ship's officers generally makes them cross. But he turned and spoke to an old seaman standing near by.

"Willmot, get two hammocks and give them to this lad," he ordered.

I followed the old sailor to the forward hold, and a few minutes afterwards presented a new hammock to the lank countryman, and kept the other myself; following the example of the other seamen, we marked our names on them in plain, black lettering.

The countryman, whose name was Amos Craig, and I found a hook forward and agreed to swing together. It was near the hatchway, but we took it because the air would be better, and it was already foul from much breathing. I did not turn in early, being in the first watch, which we kept as if we were at sea; but that night, as I looked out toward the lights of the town and realized how great a change the life before was from that I had been leading, I was half tempted to slip overboard and make a swim for it, for I felt that all this did not mean liberty. I had yet to learn that there is freedom in faithful and loyal service.

I had been much surprised by the difference in the manners shown by Captain Temple ashore from those on shipboard. This change, however, is the natural sequence of absolute authority, and the relief occasioned by being able to throw off responsibility. In after-years I felt it much the same with me, but in the writing of this tale, as I cannot claim that I have the power of adding adornment, I also intend to be as free from moralizing as I can. So, to return to what happened. As I leaned over the rail, I made up my mind to accept anything that came, and make the best of it, and to do my duty according to the best of my powers.

Half of the watch on deck were lying sprawled out and snoring against the bulwarks, keeping carefully out of the moonlight, for the reason, as I afterwards learned, that sleeping in the glare of the moon addles men's brains; but this may be mere superstition.

Up and down the quarter-deck a restless figure paced in quick, nervous strides. A sailor, with his heavy hair done in a long queue down his back, and two small gold rings in his ears, approached me and nudged me with his knee.

"Old Never-sleep is on the rampage," he said, directing his thumb over his shoulder. "We'll catch it to-morrow, you can wager on that, messmate. I've cruised with him, and I know his tricks!"

"Is he a good officer?"

"Ay, good for those who work for him, but he'll hound a shirker till you can see his bones. Some men on this 'ere craft will wish themselves overboard before this cruise is over. Jump when he speaks, that's my advice!"

Then the man went on to ask me questions. I dodged them as best I could by asking others, and as he liked to talk, I picked up not a little worth remembering. I found that Captain Temple had various nicknames that described his qualifications and characteristics to a nicety. Every skipper, no matter what his age, is called "old" on shipboard. Temple, I should judge, had not turned four-and-thirty, although he was slightly grizzled and his face was weather-seamed. "Anger-eyes" they called him on account of his keenness of vision. "Old Gimlet-ears," because it was rumored that he could hear in the cabin what went on in the forecastle. "Kill Devil," for the reason that he feared not to fight the powers of hell if they were arrayed against him. But chief of all, "Old Never-sleep," for a very evident reason. He apparently stood all watches when there was aught to be gained by vigilance.

The quartermaster on deck stepped aft as the sailor and I were talking, and spoke to Captain Temple.

"Make it so," were the words I caught from the Captain's lips.

Immediately the musical high-toned bell struck the hour. On the voyage of the Minetta I had learned to tell time after the manner at sea, and I knew that the other watch was coming on. In ten minutes I was below in my hammock.

So great a number of people composed the Young Eagle's company that the men were swinging double in the close-crowded space—that is, one hammock was underneath the other, the upper lashed high against the beams, and the lower sagging so that its occupant could touch the deck with his hand.

I had never heard such a chorus of snoring and muttering in my life, and it took me a few minutes to become accustomed to the reeking air. But at last I dozed off into a fitful rest of ever-changing dreams, and was awakened by the rolling of a drum and a confused sound of stirring, cursing, and piping. Now began a day in which I had to face some trials, I assure you, and call upon many resources that I did not know that I possessed.

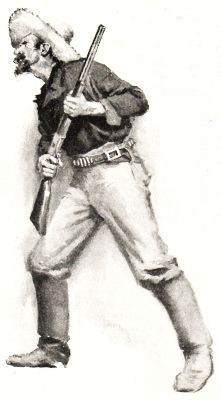

LAWSON ON THE WATCH.

LAWSON ON THE WATCH.

To begin with, it was not an investment of gold or silver, in land or bonds, or any of those things for which men vainly toil and strive, in constant peril of their souls. Of all that, I know nothing. I am simply to tell how Lawson, a volunteer soldier, defended the Cienega Ranch during the long hours of a summer day against a band of Mescalero Apaches, red-handed, thirsting for plunder, and bent upon his destruction.

I have said that Lawson was a volunteer soldier. If I rightly understood him, he was born in Ohio. At any rate, he served in the Ohio infantry, and enlisted for the war, with a thousand others, in the early fall of 1861. By rights he ought to have been drilled and properly set up and disciplined in some sort of camp of instruction in Kentucky or southern Ohio, but there was not thought to be time for that, so great was the need for men, and so he had to acquire his manual of arms and other military fundamentals in the field from day to day as he went along. Now this is not the best way nor the way laid down in the books, but it was the only way for Lawson, and whatever may be said against it, it is thorough and to the last degree effective.

In the raw early spring of 1862, Lawson's regiment, still rusty in its ployments and facings, and having as yet no abiding knowledge of the goose step, began its campaigning in West Tennessee. He was at Donelson and Shiloh, and later got his first lessons in digging and the use of the head-log at the siege of Corinth. After that was over, he marched about, hither and yon, as his Generals wished—but somewhat aimlessly as he thought—in northern Mississippi. This sort of thing was kept up all through the fall and winter until the spring came, and the Army of the Tennessee set out to do something at Vicksburg. He did his share of digging and fighting in the hot trenches there, and then, just as the cool fall breezes were beginning to blow, he betook himself with Sherman to the relief of his beleaguered comrades at Chattanooga, arriving just in time to share in Corse's gallant but unfruitful assault upon the north end of Missionary Ridge. Always a private, he missed none of the marching or fighting or digging of the Atlanta campaign, and closed the year '64 with the long sweet-potato walk to Savannah and the sea. Then he waded and toiled up through the miry Carolinas, adding not a little to his military stature and to his stock of technical war knowledge in the way of corduroying and trestle bridges, and at Bentonville finished, as he had begun, a private, full of dearly bought experience, fuller still of malaria, an expert in all the arts of defence, a resolute and resourceful soldier, who had been tried on many an emergent occasion, and who had stood shoulder to shoulder with the boys whenever they lined up at the sound of the long-roll or rushed to the parapet to repel the assaults of the enemy.

At last, when the whole thing was over, and he had been paid off and discharged, and had spent the greater part of the little that was coming to him in seeing the great world that lay between Pittsburg and Columbus, Lawson fared back to the peaceful Maumee Valley, with his chills and fever and his slender resources, only to find himself a sort of living vacancy in the body-politic. Look where he would, there seemed to be no place open for an old soldier like him in the changed order of things that somehow seemed to prevail in the little community which he called his home. He was in no sense a "hustler," he had no trade but war, no capital save his strong arms and an honest heart, and no powerful friends to push him in any direction, and so, after many disappointments, it came about that he drifted down to Cincinnati, and there enlisted in the regular army. He had served side by side with the regulars for four long years, and they were now the only folk with whose goings and comings he was familiar; and for the first time since his discharge he felt at home among the lean infantrymen as he ate his bacon and beans in the company kitchen, and took his turn at guard, as he had been used to do, or discussed the characters of his Generals with the old men who had served under them when they were Lieutenants in Mexico, in the hazy days before the war, when men's minds were at peace and soldiering a trade worth thinking of.

The days rolled into weeks and months. There was little to do, there were many to do it, and he was content, ay, happy—happier than he had been at any time, that he could remember, since the winter quarters at Chattanooga, after the blockade was broken and fresh beef and soft bread were issued every day. But this was altogether too good a thing to last, and the end came one day when a big detachment of ex-deserters and bounty-jumpers were assigned to the Fourteenth, and the good times were gone forever. To Lawson it was an enigma, and he gave it up, but it came about in this way: When the great volunteer armies were disbanded and sent to their homes, there remained on hand a residuum of deserters and men without souls, who had been bought with a price, but who belonged to no regiment, and so were kept in pay when the rest were mustered out and discharged. Of a sudden it occurred to the powers that this unpromising material might be put to some use in filling the depleted ranks of the regular army.

But fire and water will not mix, and if honest dough-boys be shaken together with such sons of Belial the regimental traditions will suffer, and discipline will surely come to naught. And so it happened that the old Fourteeth had to undergo all the pangs of dyspepsia before it could make way with the indigestible mass that had thus been cast upon it. There is no telling what dire happening would have come to the regiment had this state of things been allowed to continue indefinitely. A period was put to it at last, however, by a telegram, which came to the commanding officer at dead of night, transferring the Fourteenth to Arizona. Then it was that the deserters and bounty-jumpers held council of the situation, and being of one mind as to the unpleasing outlook, took wing and troubled the service no more, and the old Fourteenth, weaker in numbers but stronger in men than it had been since Fredericksburg, was landed at Yuma, where it was appointed to garrison the abandoned posts and protect the overland mail from the depredations of the Apaches, who had been working their will of late upon the unprotected settlements in southeastern Arizona. Here, taking his chances with the rest, and doing his full share of escort and fatigue, Lawson served "honestly and faithfully," as it ran in his discharge papers, until his term expired and he was a free man again. And then it was that he went up to keep the mail station at the Cienega.

The Cienega, or, to give the place its fall name, the Cienega de las Pimas, was a low-lying, swampy valley through which a small stream ran, alternately rising and sinking after the manner of creeks and rivers in Arizona. To the west, twenty-eight miles away, was the pueblo of Tucson, a cathedral town, once the capital of the territory. To the east, twenty-two miles distant, was the middle crossing[Pg 189] of the San Pedro. To the north there was nothing; while to the south were the Whetstone Mountains, then old Camp Wallen, the Patagonia Mine, and Old Mexico. The Cienega itself was flat, infested with all manner of poisonous vermin, submerged in the rainy season, and miry and impassable, in a military sense, at all times. It was also malarial, and to the last degree unlovely to the eye. A few dead cottonwood-trees, upon which the owls creaked at sunset, rose stiffly here and there out of the general dead level of sacaton grass and chaparral, while the tarantula and centipede and the ubiquitous rattlesnake reserved to their unhallowed uses the moist, impenetrable depths below. The station had been located just where it was because it broke into two fairly equal parts the long fifty-mile drive from Tucson to the crossings of the San Pedro. Wagon trains and occasional parties of prospectors or travellers camped at the Cienega on their way to the White Mountains, or to the Apache Pass and New Mexico, and from their small needs in the way of refreshment for man and beast Lawson and his partner eked out an extremely moderate existence. At very rare intervals a troop of regular cavalry passed that way, and the ranchmen ministered to its needs in the way of long forage to the extent of twenty dollars or more. These were red-letter days for Lawson—a very gold-mine, indeed—and led him to hope that, sometime in the uncertain future, he might be able to leave the Cienega forever, and go back to Ohio, where green grass and tall trees grew, where churches and kindred were, and where he might, perhaps, take a new start in life in a land beyond the dim eastern mountains, where pistols were not, and where civilization flourished throughout the year. This was a dream that came to Lawson in the night when a big escort camped at the Cienega and he could eat and sleep in peace.

No one who knows Arizona need be told that the Apaches were particularly bad in the early seventies. No place outside the towns or beyond the lines of the garrisoned forts was safe from their incursions. Depredations were of daily occurrence, and were only desisted from when there were no white men left to kill and no horses or cattle to steal and carry away. A single traveller journeyed south of the Gila and east of the Santa Cruz, not simply at his peril, but to certain, inevitable death. It was the same with two, or three; if four travelled together, one had a running chance to escape if the marauding party was less than ten, or if the attack came within an hour of darkness. On the whole, the best local judgment, both civil and military, was that five persons, alert, fully armed, and, above all, judiciously scattered along the trail, were the smallest company that could venture into the country ranged over by the Mescalero or Chiricahui Indians with any chance of getting out alive. The roads were dotted with the graves of those who had paid, with their lives, the awful penalty of being too venturesome, and the isolated ranches were heavily barred and otherwise defended against the common enemy. The Cienega was no exception to the rule; indeed, on account of its perilous situation, it had one or two defensive features which less-exposed ranches lacked, and which I shall presently describe. Partly because it was located near the junction of several large north and south Indian trails, and partly because of the ease with which it could be approached from the dense chaparral, it was always surrounded by hostile Apaches, and its occupants went in and out under their constant observation.

The ranch building proper, for there was but one, stood on the east bank of the muddy creek, just above where the old overland stage-road had managed to find a practicable crossing. As the trail left the ford, it wound sharply up the slope and passed between the ranch building and a huge outcrop of volcanic rocks which stood directly opposite the main entrance to the inner court, or corral. This pile of rocks had been regarded as having some defensive value when the ranch was built, apparently with the idea that, in the event of an attack, it might serve as a kind of outwork which could be defended for several hours before the garrison would be compelled to fall back to the shelter of the ranch proper. It was also so situated that, in case of siege, a small party could sally out of the main building and find cover behind the rocks long enough to enable its defenders to get a supply of water from the creek.

The enclosure, which was rectangular in plan, measured about sixty feet on each front or side. The middle of the front wall, facing the north, was pierced by a sally-port, or entranceway, about fifteen feet in width, which was closed by a heavy oaken gate. In conformity to the style of domestic architecture prevailing in all Spanish-American countries, where life and property are less safe than they are in the lands more favored of Heaven where the Anglo-Saxon dwells, this gateway was the only means by which[Pg 190] an entrance could be effected, as the other walls were without openings of any kind save those which looked upon the inner court. The rudely constructed interior can be quickly described. On the east side of the entrance was a large living-room some twenty feet square; on the west were several smaller rooms for horse-gear and the storage of grain. The other three sides were roofed, but not otherwise enclosed, and were used as stables.

At the southeast corner, opposite the living-room, Lawson had built a circular flanking tower, which projected a little more than three feet beyond the outer walls, and from this corner tower, which was loopholed, the east and south sides of the enclosure could be raked or flanked. It was a novel construction, and Mexican cargadors, wrapped in their serapes of manta, sat squat on their haunches and soberly regarded it for hours, wondering at the Gringo's strange conceit in building. Curious travellers casually observed it in passing, and thought it a spring-house, or perhaps a place where whiskey and other precious valuables could be safely deposited; but none, even the most inquisitive, suspected its real purpose or gave it a moment's serious thought. We shall presently see, however, how useful it proved to be.

The living-room was simple and plain to the last degree. In the first place, there was a fireplace of adobe, at which all the cooking was done; there were two rude bunks, in which Lawson and his partner slept, and there was a rough table, made out of a discarded hardtack box, which stood under the window overlooking the interior court. These, with a half-dozen stout chairs with rawhide seats, completed the scanty array of furniture. Each man wore a pistol and a thimble-belt always, and was never far from a repeating Winchester rifle. At the head of each bed, ready for instant use, stood a perfect arsenal of weapons of all dates and calibres. Some were modern, and likely to be of service in an emergency, the rest were antiquated and obsolete, mere bric-à-brac indeed, and were kept because, as Lawson put it, "they might come in handy sometime."

So, as the matter stood, the garrison—that is, Lawson and his partner Green, an ex-Confederate from the Army of Northern Virginia—had thought the thing all over, and settled in their minds that, in the event of an attack, they would proceed in about this wise. If the attack came from the north, which was by all odds the most exposed and dangerous quarter, they would first hold the rock outwork to the last extremity. It was agreed between them that their principal danger would consist in an attempt on the part of the Indians to scale the walls, either to make a lodgement on the roof or to set it on fire. Now if such an attempt happened to be made on the east or south side, which was commanded by the flanking tower, the garrison would be heard from, and serious injury might be inflicted upon the assailants—enough, perhaps, to hold them in check until the mail-drivers, who passed daily in either direction, could carry the alarm to the regular cavalry posts at Tucson and the Apache Pass. It should be said, however, that so much of the partners' ingenious plan of defence as depended upon the arrival of a mail-rider was, at best, a feeble reliance, as they were more likely to be killed than not in the event of an attack; but feeble as it was, it was all that seemed to stand between the occupants of the ranch and a lingering death by torture, should the Apaches conclude to make a descent in force upon the Cienega; and thus matters stood there just before sunrise on the morning of the 21st of July, 1870.

AS GREEN SPED THROUGH HE FELT THE HOT BREATH OF HIS

PARTNER'S WINCHESTER.

AS GREEN SPED THROUGH HE FELT THE HOT BREATH OF HIS

PARTNER'S WINCHESTER.