Cover art

Title: Jack the Englishman

Author: H. Louisa Bedford

Illustrator: Walter Paget

Release date: November 12, 2019 [eBook #60676]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

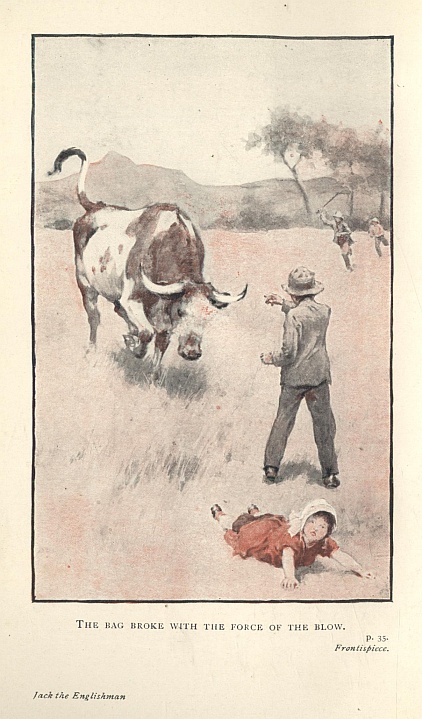

THE BAG BROKE WITH THE FORCE OF THE BLOW. p. 35.

BY

H. LOUISA BEDFORD

AUTHOR OF

"HER ONLY SON, ISAAC" "MRS. MERRIMAN'S GODCHILD," ETC.

ILLUSTRATED BY WAL PAGET

LONDON

SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING

CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE

NEW YORK AND TORONTO: THE MACMILLAN CO.

Printed in Great Britain by Wyman & Sons Ltd.,

London, Reading and Fakenham.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

I. HIS TITLE

II. A CHUM

III. NEW NEIGHBOURS

IV. A BUSH BROTHER

V. A CHURCH OFFICIAL

VI. MINISTERING CHILDREN

VII. A BISHOP'S VISIT

VIII. TWO LEAVE-TAKINGS

IX. A SURPRISE VISIT

X. A BUSH TOUR

XI. A NARROW ESCAPE

XII. GOING HOME

XIII. TWO VENTURES OF HOPE

JACK, THE ENGLISHMAN

It was a beautiful spring afternoon in the northern hill districts of Tasmania. The sky was of a bird's egg blue, which even Italy cannot rival, and the bold outline of hills which bounded the horizon, bush clad to the top, showed a still deeper azure blue in an atmosphere which, clear as the heaven above, had never a suggestion of hardness. Removed some half-mile from the little township of Wallaroo lay a farm homestead nestling against the side of the hill, protected behind by a belt of trees from the keen, strong mountain winds, and surrounded by a rough wood paling; but the broad verandah in the front lay open to the sunshine, and even in winter could often be used as the family dining-room. The garden below it was a mass of flowers for at least six months in the year, and there was scarcely a month when there was a total absence of them.

The house, one-storied and built of wood like all the houses in the country districts, was in the middle of the home paddock; the drive up to it little more than a cart track across the field, which was divided from the farm road which skirted it by a fence of tree trunks, rough hewn and laid one on the top of the other. A strong gate guarded the entrance, and on it sat Jack, the Englishman, his bare, brown feet clinging to one of the lower bars, his firmly set head thrown back a little on his broad shoulders as he rolled out "Rule Britannia" from his lusty lungs. Many and various were the games he had played in the paddock this afternoon, but pretending things by yourself palls after a time, and Jack had sought his favourite perch upon the gate and employed the spare interval in practising the song which father had taught him on the occasion of his last visit. He must have it quite perfect by the time father came again. It was that father, an English naval captain, from whom Jack claimed his title of "Jack, the Englishman," by which he was universally known in the little township, and yet the little boy, in his seven years of life, had known no other home than his grandfather's pretty homestead.

"But o' course, if father's English, I must be English too. You can't be different from your father," Jack had said so often that the neighbours first laughed, and then accepted him at his own valuation, and gave him the nickname of which he was so proud.

About the mother who had died when he was born, Jack never troubled his little head; two figures loomed large upon his childish horizon, Aunt Betty and father. Aunts and mothers stood about on a level in Jack's mind; it never suggested itself to him to be envious of the boys who had mothers instead of aunts, for Aunt Betty wrapped him round with a love so tender and wholesome, that the want of a mother had never made itself felt, but father stood first of all in his childish affection.

It was more than eight years since Lieutenant Stephens had come out from England in the man-o'-war which was to represent the English navy in Australian waters, and at Adelaide he had met Mary Treherne, a pretty Tasmanian girl, still in her teens, who was visiting relations there. It was a case of love at first sight with the young couple, who were married after a very short engagement. Then, whilst her husband's ship was sent cruising to northern seas, Mary came back to her parents, and there had given birth to her little son, dying, poor child, before her devoted husband could get back to her. Since then Lieutenant Stephens had received his promotion to Captain, and had occupied some naval post in the Australian Commonwealth, but his boy, at Betty Treherne's urgent request, had been left at the farm, where he led as happy and healthful an existence as a child could have. The eras in his life were his father's visits, which were often long months apart, and as each arrival was a living joy, so each departure was grief so sore that it took all little Jack's manhood not to cry his heart out.

"Some day—some day," he had said wistfully on the last occasion, "when I'm a big boy you'll take me with you," and his father had nodded acquiescence.

"It's not quite impossible that when I'm called back to England, I may take you over with me and put you to school there, but that is in the far future."

"How far?" Jack asked eagerly.

"That's more than I can tell; years hence very likely."

But even that distant hope relieved the tension of the big knot in Jack's throat, and made him smile bravely as father climbed to the top of the crazy coach that was to carry him to the station some eight miles away.

From that time forward, Jack insisted that Aunt Betty should measure him every month to see if he had grown a little.

"Why are you in such a hurry to grow up?" she asked, smiling at him one day. "You won't seem like my little boy any more when you get into trousers."

"But I shall be father's big boy," was the quick rejoinder, "and he'll take me with him to England when he goes. Did he tell you?"

Aunt Betty drew a hard breath, and paled a little.

"That can't be for years and years," she said decidedly.

"He said when I'm big, so I want to grow big in a hurry," went on Jack, all unconscious how his frank outspokenness cut his aunt like a knife. Then he turned and saw tears in her pretty eyes, and flew to kiss them away.

"But why are you crying, Aunt Betty? I've not been a naughty boy," he said, reminiscent that on the occasion of his one and only lie, the enormity of his sin had been brought home to him by the fact that Aunt Betty had cried.

She stooped and kissed him now with a little smile.

"I shan't like the day when you go away with father."

"But o' course you'll come along with us," he said, as a kind of happy afterthought, and there they both left it.

And now Aunt Betty's clear voice came calling down the paddock.

"Jack, Jack, it's time you came in to get tidy for tea," but Jack's head was bent a little forward, his eyes were intently fixed upon a man's figure that came walking swiftly and strongly up the green lane from the township, and with a shrill whoop of triumph he sprang from his perch, and went bounding towards the newcomer.

"Aunt Betty, Aunt Betty," he flung back over his shoulder, "it's father, father come to see me," and the next minute he was folded close to the captain's breast, and lifted on to his shoulder, a little boy all grubby with his play, but as happy and joyful as any child in the island.

And across the paddock came Aunt Betty, fresh as the spring day in her blue print gown, and advancing more slowly behind came Mr. and Mrs. Treherne.

"A surprise visit, Father Jack, but none the less a welcome one," said Mr. Treherne. He was a typical Tasmanian farmer with his rough clothes and slouch hat, but a kindly contentment shone out of his true blue eyes, and he had an almost patriarchal simplicity of manner. He bore a high name in all the country-side for uprightness of character, and was any neighbour in trouble Treherne was the man to turn to for counsel and help. And his wife was a help-meet indeed, a bustling active little woman, who made light of reverses and much of every joy. The loss of her eldest daughter had been the sharpest of her sorrows, and the gradual drifting of her four sons to different parts of the colony where competition was keener and money made faster than in "sleepy hollow," as Tasmania is nicknamed by the bustling Australians. There was only one left now to help father with the farm, Ted and Betty out of a family of seven!

But still Mrs. Treherne asserted confidently that the joys of life far outweighed its sorrows. Perfectly happy in her own married life, her heart had gone out in tenderest pity to the young Lieutenant so early left a widower, and a deep bond of affection existed between the two. She took one of his hands between her own, and beamed welcome upon him.

"It's good luck that brings you again so soon."

"It's a matter of business that I've come to talk over with you all, but it can wait until after supper. I'm as hungry as a hunter. I came straight on from Burnie without waiting to get a meal."

"If you had wired, you should have had a clean son to welcome you," said Betty. "Climb down, Jack, and come with me and be scrubbed. Don't wait for us, mother. The tea is all ready to come in."

Jack chattered away in wildest excitement whilst Aunt Betty scrubbed and combed, but Betty's heart was thumping painfully, and she answered the boy at random, wondering greatly if the business Father Jack talked about implied a visit to England, and whether he would want to take his little son with him.

"He has the right! of course he has the right," she thought. "Aunts are only useful to fill up gaps," and her arms closed round little Jack with a yearning hug.

"There! now you're a son to be proud of, such a nice clean little boy smelling of starch and soap," she said merrily, with a final adjustment of the tie of his white sailor suit, and they went down to tea hand in hand, to tea laid in the verandah, with a glimpse in the west of the sun sinking towards its setting in a sky barred with green and purple and gold.

Little Jack sat by his father, listening to every word he said, and directly tea was ended climbed again on to his knee and imperatively demanded a story. It was the regular routine when Father Jack paid a visit.

"And what is it to be?" asked the captain

"Why, Jack, the Giant Killer, or Jack and the Beanstalk. I love the stories about Jacks best of all, because Aunt Betty says the Jacks are the people who do things, and she says you and all the brave sailors are called Jack Tars, and that I'm to grow up big and brave like you, father."

The Captain's arm tightened round his son.

"It's very kind of Aunt Betty to say such good things about the Jacks of the world. We must try and deserve them, you and I. Well, now, I'm going to tell you a sort of new version of Jack, the Giant Killer."

"What's a new version?" asked Jack, distrustfully.

"The same sort of story told in a different way, and mine is a true story."

"Is it written down in a book? Has it got pictures?"

"Not yet; I expect it will get written down some day when it's finished."

"It isn't finished," cried Jack in real disappointment.

"Wait and listen—There was once a man——"

"Oh, it's all wrong," said Jack impatiently. "It's a boy in the real story."

"Didn't I tell you mine was a new version? Now listen and don't interrupt——"

Mr. Treherne leant back in his chair, listening with a smile to the argument between father and son as he smoked his pipe; Mrs. Treherne had gone off into the house, whilst Betty, after setting the table afresh for Ted who would be late that evening as he was bringing home a mob of cattle, seated herself in the shadow, where she could watch the Captain and Jack without interruption.

"There was once a man," began the Captain over again, "who looked round the world, and noticed what a lot of giants had been conquered, and wondered within himself what was left for him to do."

"No giants he could kill?" asked Jack excitedly, "Were those others all deaded?"

"Not deaded; they were caught and held in bondage, made to serve their masters, which was ever so much better than killing them."

"What were their names?"

"Water was the name of one of them."

Jack stirred uneasily. "Now you're greening me, father"—the term was Uncle Ted's.

The Captain laughed. "Didn't I tell you this was a true story? Water was so big a giant that for years and years men looked at it, and did not try to do much with it. The great big seas——"

"I know them," cried Jack. "Aunt Betty shows them to me on the map, and we go long voyages in the puff-puff steamers nearly every day!"

"Ah! I was just coming to that. At first men hollowed out boats out of tree trunks, and rowed about in them, timidly keeping close to the shore, and then, as the years rolled on, they grew braver, and said: 'There's another giant that will help us in our fight with water. Let us try and catch the wind.' So they built bigger boats, with sails to them which caught the wind and moved the ships along without any rowing, and for many, many years men were very proud of their two great captive giants, water and wind, and they discovered many new countries with their wind-driven ships, and were happy. But very often the wind failed them, grew sulky, and would not blow, and then the ship lay quiet in the midst of the ocean; or the wind was angry, and blew too strong—giants are dangerous when they lose their temper—and many a stately ship was upset by the fury of the wind, and sent to the bottom. Then men began to think very seriously what giant they could conquer that would help them to make the wind more obedient to their will, so they called in fire to their aid. Fire, properly applied, turned water into steam, and men found that not only ships, but nearly everything in the world could be worked through the help of steam."

Jack was getting wildly interested in the new version. "Oh, but I know," he said, clapping his hands. "There's trains, and there's steam rollers; I love it when they come up here, and there's an engine comes along and goes from farm to farm for the threshing, and that's jolly fun for the threshers all come to dinner, and——"

"Yes, I see you know a lot about these captive giants after all," said the Captain, bringing him back to the point.

"Go on, please; it's just like a game," said Jack. "Perhaps I'll find out some more."

"I can't go on much longer. It would take me all night to tell you of all the giants we keep hard at work. Three are enough to think of at a time. Tell me their names again for fear you should forget."

"Water—one. Wind—two, and Fire, that makes steam—three," said Jack, counting them off, as he rehearsed them on his father's fingers. "Just one more, daddy dear," a phrase he reserved for very big requests.

"One more then, and away you go to bed, for I see Aunt Betty looking at her watch. The last giant that the man of the story very much wishes to conquer, and has not done it yet, is air. He wants to travel in the air faster than any train or steamship will take you by land or water."

"Like my new toy, the one grandmother sent for on my birthday seven. She sent for it all the way to Melbourne, an 'airyplane' she calls it, but it only goes just across the room, and then comes flop."

"That's just it; at present flying in the air too often ends in flop, and this man I'm talking of wants to help to discover something that will make flying in the air safer and surer. There are lots of men all over the world trying to do the same thing. All the giants I have told you of are too big and strong for one man to grapple with by himself, but many men joined together will do it, and the man of the story has been working at it by himself for years, and at last—at last he thinks he has discovered something that will be of service to airmen and to his country, and he's going over to England to test it—to see if his discovery is really as good as he believes it to be."

Little Jack sat grave and very quiet, pondering deeply.

"What's the man's name, father? The man you're telling about."

"Jack, a Jack who will be well content if he can help to do something big in conquering the giant Air. It's your father who is the man of the story. I promised it should be a true one."

Jack's answer seemed a little irrelevant. He slipped from his father's knee and took his hand, trying with all his might to pull him up from his chair. "Come, father, come quick and see how big I've grown. Aunt Betty measures me every month, and says I'm quite a big boy for my age."

Wondering at the sudden change of subject, the Captain humoured his little son, and allowed himself to be dragged to the hall where, against the doorpost of one of the rooms, Jack's height was duly marked with a red pencil.

"Aunt Betty's right. You're quite a big boy for only seven years old."

"I knewed it," cried Jack, in rapturous exultation, "so you'll take me along with you, dear, and we'll hit at that old giant Air together. Oh, I'm so glad, so glad to be big."

"Not so fast, sonny," said the Captain, gently gathering him again into his arms. "You're a big boy for seven years old, but you're altogether too young for me to take you to England yet."

Jack's face went white as the sailor suit he wore, and his great round eyes filled to the brim with tears, but by vigorous blinking he prevented them from falling down his cheeks.

"You said—perhaps when I was big you'd take me with you."

"And that will be some years hence when I'll come back to fetch you, please God."

"Me and Aunt Betty, too," said Jack, with a little catch in his throat, "'cause she'll cry if I leave her."

"Jack, it's bedtime, and you will never go to sleep if you get so excited," said Aunt Betty decidedly, feeling all future plans swamped into nothingness by the greatness of the news Father Jack had come to tell.

"Look here, I'll carry you pig-a-back," said the Captain, dropping on to all fours. "Climb up and hold fast, for the pig feels frisky to-night, and I can't quite tell what may happen." So Jack went off to his cot in Aunt Betty's room in triumph and screams of laughter, but the laughter gave way to tears when bathed and night-gowned he knelt by Aunt Betty's side to say his prayers. The list of people God was asked to bless was quite a long one, including various friends of Jack's in the township, but last of all to-night came his father's name.

"God bless Father Jack, and make Little Jack a good boy and very big, please, dear God, so as he'll soon have father to fetch him home."

And then, with choking sobs, Jack sprang to his feet and into bed.

"Tuck me in tight, Aunt Betty, and don't kiss me, please. I'll tuck my head under the clothes, and don't tell father I'm crying. It's only little boys who cry, he says, and I want to be big, ever so big. I'll grow now, shan't I? Now I've asked God about it."

Aunt Betty's only answer was a reassuring pat on his back as she tucked the bedclothes round him. Truth to tell she was crying a little too.

"You've sprung it upon us rather suddenly, Jack."

Betty and her brother-in-law sat in the verandah in the glory of the Tasmanian night. The stars shone out like lamps from the dark vault above with a brilliancy unknown in our cloudier atmosphere; a wonderful silence rested on the land, except that at long intervals a wind came sighing from the bush-clad hills, precursor of the strong breeze, sometimes reaching the force of a gale, that often springs up with the rising of the sun.

Jack removed his pipe and let it die out before he answered Betty.

"To you I expect it may seem a fad, the result of a sudden impulse, but really I've been working towards this end ever since aviation has been mooted, spending all my spare time and thought upon the perfecting of a notion too entirely technical to explain to anyone who does not understand aeroplanes. Finally I sent over my invention to an expert in the Admiralty, with the result that I've received my recall, and am to work it out. There is no question that at this juncture, when all nations are hurrying to get their air fleet afloat, we are singularly behindhand, and I feel the best service I can give my country is to help, in however small a degree, to retrieve our mistake."

"You don't really think England is in peril, do you?"

"The unready man is always in peril, and England is singularly unready for any emergency at the present time. I believe with some men the call of country is the strongest passion in their blood. For a moment the thought of leaving the little lad staggered me, for, of course, he's altogether too young to think of taking him with me. Nobody would mother him as you are doing, Betty. I would like him to be with you for some years longer yet, if you agree to continue taking charge of him."

"But of course," said Betty, with a little catch in her throat. "He is my greatest joy in life. I dread the time when I must let him go."

"Thank you; I want to leave him here as long as possible until it becomes a question of education. Of course I would like if he shows any inclination that way that he should follow in my footsteps, either serve in the navy or in the air fleet."

Betty gave a little gasp. "But the peril, Jack! Think of the lives that have been already sacrificed."

Jack shrugged his shoulders. "By the time the boy is old enough to think of a profession, I don't suppose aviation will be much more dangerous than any other calling that is distinctly combative in character, and if it is, I hope my son will be brave enough to face it. However, what Jack will be or do when he grows up is too far a cry to discuss seriously."

"And meanwhile what do you want me to do with him?"

"Just what you are doing now. Bring him up to fear God and honour the King."

"And when education presses? I can teach him to read and write and a little arithmetic, but when he ought to go further? Am I to send him away to a boarding school?"

"I think not, Betty. I would almost rather you let him go to the State school here, and kept him under your own eye. I don't believe association during school hours with all and sundry will hurt him whilst he has you to come back to, and the teaching at some of these schools is far more practical and useful than at many a preparatory school at home. What can you tell me of the master here?"

"He's rather above the average, and if he finds a boy interested in his work is often willing to give him a helping hand. For one thing, I don't believe Jack will ever want to be much off the place out of school hours. He's a manly little chap, and loves being about with Ted or father on the farm. I wish sometimes he had some chum of his own, a little brother, or what would be almost as good—a little sister. His play is too solitary."

"I'm afraid it's out of your power or mine to cure that," said the Captain, rather sadly, his thoughts going back to the pretty wife who had been his for so short a time.

When little Jack appeared at breakfast the following morning there was no sign of the previous night's emotion, but he was quite inseparable from his father that day, never leaving his side for an instant if he could help it. He was much graver than usual, intent upon watching the Captain's every movement, even adjusting his own little shoulders to exactly the same angle as his father's, and adopting a suspicion of roll in his walk.

The Captain was to leave by the evening coach, and Betty catching the wistful look in little Jack's eyes suggested that he should be the one to escort the Captain down the green lane to the hotel in the township from which the coach started. Jack, holding his father's hand tight gripped in his own, scarcely uttered a word as they walked off together. He held his head high and swallowed the uncomfortable knot in his throat. Not again would he disgrace his manhood by breaking into tears.

"I'll be real big when you come next time," he ventured at last. "Will it be soon?"

"As soon as I can make it, Jackie. Meanwhile you'll be good and do as Aunt Betty tells you."

"Yes, sometimes. I can't always," said Jack truthfully.

"Well, as often as you can. And little or big you'll not forget you're Jack, the Englishman, who'll speak the truth and be brave and ready to fight for your country if need be."

"Yes," said Jack, squaring his shoulders a little.

"And I'll write to you from every port—Aunt Betty will show you on the map the ports my ship will touch at—and when I get home I shall write to you every week."

That promise brought a smile to Jack's twitching lips.

"Oh, but that's splendid! A letter all my own every week," he said, beginning to jump about with excitement at the prospect.

"Will it have my name written upon the envelope?"

"Why, yes. How else should the postman know whom it's for? You'll have to write to me, you know."

That proposition did not sound quite so delightful, and Jack's forehead puckered a little. He remembered the daily tussle over his copy-book.

"I don't write very well just yet," he said.

"That will have to be amended, for a letter I must have every week. Aunt Betty will guide your hand at first, and very soon I hope you will be able to write me a sentence or two all your own, without Aunt Betty's help."

"But what'll I say in a letter?" asked Jack, still distrustful of his own powers.

"Just what you would say to me if you were talking as you're talking now; how you get on with your lessons. If you're a good boy or a bad one, who you meet, what picnics you have; anything you like. What interests you will surely interest me."

The thought that father would still talk to him when he was away kept Jack steady through the parting, that, and the fact that a young horse only partially broken in was harnessed to the steady goer who for months past had been one of the hinder pair of the four-horse coach, played all manner of pranks at starting; at first declining to budge at all; then, when the superior force of the three others made movement necessary, setting his four legs together and letting himself be dragged along for a few paces, finally breaking into a wild gallop which was checked by his more sober mates, until at last finding himself over-matched he dropped into the quick trot of the other three, fretting and foaming at the mouth, nevertheless, at his enforced obedience. It was a primitive method of horse-breaking, but effectual. And so Jack's farewells to his father were diversified by watching the antics of the unbroken colt, and joining a little in the laughter of the ring of spectators that had gathered round to see the fun. But when the final start was made Jack was conscious of the smarting of unshed tears, rubbed his eyes vigorously with his sturdy fists and set off home at a smart trot, standing still sometimes and curvetting a little in imitation of the colt that needed breaking in.

Betty, who stood waiting for him at the gate of the paddock, ready to comfort and console, saw him gambolling along like a frisky horse, and felt her sympathy a little wasted. Children's sorrows are proverbially evanescent, but she was hardly prepared for Jack to return in such apparently rollicking spirits from the parting with his father of indefinite duration. And when he came up to her it was of the horse and its capering that he told her, mimicking its action in his own little person: holding back, pelting forwards, trying to rear, interspersed with vicious side kicks, and finally a wild gallop which sobered into a trot.

"That's 'zackly how he went," he said, waiting breathless for Aunt Betty to catch him up.

Betty was extremely astonished that Jack made no mention of his father, but later she understood. Tea was over, and before Jack went to bed Betty allowed him a quarter of an hour's play at any game he chose.

"Would you like to be the frisky horse again, and I will drive you," she asked, willing to humour his latest whim.

"No, I'll get my slate and write, only you must help me."

This was indeed an unexpected development for Jack, and left Betty speechless. Jack was quick at reading and quite good at counting, but writing was his particular bug-bear.

She lifted him on to her lap, and he bent eagerly over the slate on his knees.

"Now, what do you want to write," Betty asked, taking his right hand in her own firm, strong one.

"A letter—a letter to father. He's going to write to me every week. How do you begin? He says I must write every week, same as he does."

"All right! 'My dear Father'—That's the way to begin."

By the time the "r" was reached Jack lifted a flushed face.

"It's awful hard work; I'll never do it."

"Oh, yes we will. We'll write it to-morrow in your copybook. Very soon it will come quite easy."

And the wish to conquer made Jack comparatively patient at his writing the following morning. Lessons over, he turned out into the paddock as usual to play, but somehow all zest for play had deserted him. The effort to prove himself a man the day before had a reaction. Every game, played alone, lost its flavour. Hitherto Jack had never been conscious of the need of a playmate. His whole being had been so absorbed in his father that the looking forward to his visits, the saving up everything to show him and to tell him, had satisfied him; but to-day, with that father gone, he floated about like a rudderless boat, fretful and lonely, not able to voice his vague longing for something to happen! He opened the gate and looked down the lane. On the opposite side of the lane was a tenantless house; the half-acre in which it stood had never been brought into proper cultivation as a garden, but the flowers and shrubs which had been planted haphazard about it had grown now into tangled confusion, and Jack, when tired of his own premises, had often run down there, where, crawling on all-fours through the long grass and shrubs, he had imagined himself lost in the bush, and great was his joy when Aunt Betty, not finding him in the home paddock, would come wandering down the lane, saying in a clear, distinct tone:

"Now where can that little boy have gone? I'm afraid, I'm dreadfully afraid, he's lost in the bush! I wonder if it's possible he can have strayed in here."

Then her bright head would be thrust over the gate, and each time Jack was discovered cowering from sight there would be a fresh burst of rapture on the part of the much-distressed aunt and roars of delighted laughter from Jack. It was a most favourite game, but he did not wish to play it to-day.

Yet he resented it a little that a bullock-wagon was drawn to one side of the road, the wagon piled high with furniture, which was being lifted piece by piece into the house. His happy hunting-ground was to be his no longer, for evidently the house was to be occupied by a fresh tenant. Dancing to and fro with the men who were unlading the dray was a little girl, her face entirely hidden by a large sun-bonnet, and the rest of her little person enveloped in a blue overall, below which came a pair of sturdy brown legs, scarcely distinguishable from the tan shoes and socks below.

Jack's resentment at the thought of losing his playground yielded to excitement at the prospect of a playmate so close at hand, and he crept cautiously along his side of the lane to obtain a nearer view of the new-comer, finally taking a seat against the fence just opposite the house. It was a minute or two before the little girl discovered him. When she did she crossed the dividing road and stood just far enough from him to make a quick retreat to her own premises if a nearer inspection was unfavourable. It was almost a baby face that peered out from the bonnet: round apple cheeks, big serious eyes, and a halo of dark curls that framed the forehead. Her eyes met Jack's for a moment, then dropped in a sudden attack of shyness, and she showed signs of running away without speaking.

"Wait a bit," said Jack. "Can't you tell us your name?"

The child drew a step nearer. "What's yours?" she said, answering Jack's question by another.

"I'm Jack, father's called Jack, too."

"I'm Eva, but mummy calls me puss. Is that your place?" with a nod towards Jack's home.

"Yes, you can come and look at it if you like," and Jack held out a grubby hand.

Eva paused, looked up the lane and down it.

"Mummy only lets me play with nice little boys," she said.

"All right," said Jack, rising and turning back to go home. That he was rejected on the score of not being nice enough to play with puzzled him rather than annoyed.

There was a hasty scuttle after him as Eva ran to catch him up.

"Stop, boy! I think you's nice! You's got booful blue eyes!"

Jack turned, laughing merrily. "You're a funny little kiddie. Do you want to come, then?"

Eva nodded gravely, thrusting a confident hand in his.

"You're old, a lot older than me," she said, admiring the agility with which Jack climbed the top of the gate and pulled back the iron fastening to let her through.

"I'm seven, big for my age, Aunt Betty says, but I want to be a lot bigger before I'm done with."

"I'm six next bufday," Eva announced. "I had a bufday last week."

"Then you're six now."

Eva shook her head vigorously. "Next bufday, mummy says."

"Oh, you're only five," said Jack dejectedly. A baby of five was really too young to play with.

"Can you play horses?"

"Yus," suddenly smiling into Jack's face.

"And cricket?"

"Kick it, a ball like this," throwing out her little foot. "Yus."

"Let's see how you run. I'll give you quite a long start, and we'll see which can get to the house first."

Eva's stout legs acquitted themselves so well that Jack's esteem and respect grew by leaps and bounds.

"You'll do quite well for a chum, after all," he said as he panted up to her. "Come along and see Aunt Betty."

Aunt Betty's whereabouts were not difficult to discover. Her song rose clear and full as a magpie as she busied herself in the dairy which adjoined the house. The sound of Jack's voice made her turn from her milk-pans to the doorway which framed him and his little companion.

"Why, Jack, who is the little girl?" she asked.

"Her name is Eva, and I've just settled she shall be my chum," was the decided answer.

But Eva, frightened at finding herself quite away from her own people, threw herself on the doorstep and hid her face in a fit of sobbing.

"I won't be nobody's chum! Take me home to mummy," she said.

Betty's arms closed round her consolingly.

"So I will directly Jack can tell me where mummy lives," said Betty. "Come along, Jack, and show me where to take her."

A resolute-looking little woman faced Betty as she crossed the threshold of the door of the new neighbour. Betty carefully deposited Eva on one of the boxes which littered the floor and explained her presence.

"It was kind of you to bring her back. Pussie has a sad trick of poking in her nose where she's not wanted," said Eva's mother; but the child, restored to confidence, raised indignant protest.

"Boy does want me; he wants me for a chum, mummy, and I think he's nice! Just look at him."

Betty watched the grave little face soften into a smile as the eyes rested first on Eva and then on Jack, who stood shyly in the doorway.

"We are neighbours, then," she said, ignoring Eva's words. She was clearly a woman who would commit herself to no promise that she might not be able to keep.

"My father, Mr. Treherne, owns the farm close by. Jack is his little grandson," said Betty simply, "and I'm his only daughter."

"And my name is Kenyon. Come along, Eva; we'll leave all this alone until after tea, and when you're in bed I must straighten things a bit," said Mrs. Kenyon as Betty turned to go.

The voice was tired, and an English voice. The speaker, still young, for she certainly was well under thirty, inspired Betty with the feeling that she had had a hard fight with the world.

"Won't you come back to supper with us? I know mother will be glad to see you, and it's hard to get things comfortable on the first night in a new house."

"Comfortable!" echoed Mrs. Kenyon, with a note of scorn in her voice. "It will be days before we can be that. The house has been standing empty for a long time apparently, and needs soap and water in every corner of it. I should like to send it to the wash, but as that can't be done I must wash it myself, every inch of it. I took it because it was cheap!"

"Will you come, then," said Betty again.

"I beg your pardon. You'll think English manners defective, but I'm so tired I can hardly think of what I'm saying. No, there is so much to be done I think I will stay here, thanking you all the same for asking us." So Betty said no more, and taking Jack's hand walked quickly down the road. Jack chattered all the way about Eva.

"D'you think she'll be my chum, Aunt Betty?"

"We'll wait and see, Jackie, and don't be in too great a hurry. She'll want you all the more if you don't seem too keen to have her," answered Betty, smiling, giving the little boy his first lesson in worldly wisdom.

But the thought of the tired face haunted kind Betty as she sat down to supper. She told her mother something of the new neighbour.

"She's such a decided, determined look and manner, mother. She's been pretty, and she's rather pretty still, only her face has grown hard, as if she'd had a lot of trouble. She's young to be a widow."

"What makes you think she's a widow? She did not tell you so."

"There's no sign of a man about the place; she clearly has to fend for herself, and to English people it's hard work. They're not brought up to be useful!"

Mrs. Treherne laughed. "She's English, then."

"Yes, she said so, and she's proud and independent; but I think when Jack is in bed I'll risk the chance of a snub, and go and see what I can do for her."

An hour later Betty stood again before Mrs. Kenyon's door. From the inner room came a sound of singing, and through the half-opened door Betty caught a glimpse of a little bed that stood in the corner, over which Mrs. Kenyon bent tenderly soothing Eva to sleep with her soft lullaby.

"She has one tender spot in her heart, anyway," thought Betty, giving a little cough to proclaim her presence. Mrs. Kenyon turned and came toward her on tip-toe, drawing the door of her bedroom gently to behind her.

"Eva was excited and would not go to sleep. I don't generally spoil her like that, but she's off now as sound as a top."

"I've come to help you for an hour or two if you will have me."

Mrs. Kenyon's bright eyes scanned Betty from head to foot.

"It's not everyone that I could accept help from, but I'll be glad of it from you."

So the two worked side by side with a will and with scarcely a word exchanged between them. They shifted boxes, placed furniture in temporary safety against the walls, but to Betty fell the lion's share of the lifting.

"I don't know how you do it; you're as strong as a man," said Mrs. Kenyon, subsiding into a chair for a moment's rest.

"We're made so out here; for one thing we are accustomed to use our muscles from the moment we can walk. We don't—have our shoes buttoned up for us," with a sly glance at her companion.

Mrs. Kenyon gave a short laugh. "Nor have I since I came out here. Since I married I learned the way to clean them. That's six years ago, and for three years I've made the child's living and my own. It has not been a bed of roses. I tried various methods, was lady-help and so on; but now I'm a dressmaker, and that not only pays better, but leaves me free to keep a little home of my own. I hope the people in the township need a dressmaker."

"Indeed they do if you are willing to work in the house. The only woman we can get is engaged weeks beforehand, and then as often as not fails one at the last minute. If you are good I believe you will hardly have a day free."

"That's good hearing, but they must accept Eva with me. I can't leave her, you see. Turn her into the garden and she is as independent as a puppy. I think I am good at sewing! As a girl at home I made most of my own gowns and was often asked the name of my dressmaker. I decided to come here as someone I met told me there was a good opening."

Betty's eyes rested thoughtfully on the speaker The dusk gave her courage to express her thought.

"I almost wonder you did not go home. You're not really fitted for a fight with life."

Mrs. Kenyon's chin lifted. "I chose my lot and will abide by it."

Betty knew she had been guilty of an impertinence in trying to probe beneath the surface, and rose to go.

"You'll go to bed now; you won't try to do anything more when I'm gone," she pleaded.

"No, I'll go to bed chiefly because I must."

"And to-morrow won't be a busy day with me; you'll let me come again?"

"Surely yes, and thank you for your kindness. It's been more than manual help; you've heartened me up; you're so splendidly happy. Your very step has happiness in it. It must be because you're so strong."

But there Mrs. Kenyon erred, for Betty's happiness lay rather in the fact that quite unconsciously she brought happiness to all about her.

The next morning Jack, sent on a message to the township, sauntered leisurely past the opposite side of the lane from Eva's home, casting one furtive glance to see if she were anywhere in sight, and then conscious of a rosy face flattened against the gate, went on with his eyes held steadily in front of him. Of course if a little girl did not want to be a big boy's chum—Jack was too young to finish the sentiment, but a lump of disappointment rose to his throat and a sudden impulse made him take to his heels and fly, casting never a backward look.

He was not long gone, for Aunt Betty's orders had been peremptory. She was pressed for time and there must be no loitering by the way. He saw that Eva had pushed open the gate and was wandering down the lane towards the entrance to the paddock, a bright spot of colour in her little red overall. The green road extended beyond Mr. Treherne's land to another farm some distance further on, and from the far end of it Jack saw a young bullock trotting in Eva's direction. Quite used to animals and wholly unafraid of them this usually would not have been worthy of remark, but he recognised this animal as dangerous and perfectly unamenable to training. Only yesterday he had stood by, an excited spectator, whilst his grandfather and uncle had been assisting their neighbour in his efforts to bring the bullock into subjection, but it had proved so wild and vicious that it had been driven into a paddock by itself until its owner could decide what to do with it.

"Best get rid of it," Mr. Treherne advised, "get rid of it before it gets you into trouble. The creature is not safe."

And Mr. Marks, his neighbour, slept upon the advice and waked in the morning determined to act upon it, so he and his son after much difficulty had succeeded in roping the bullock's horns and between them were going to lead it down to the township to the butcher, but as the farmer opened the gate which led into the lane he relaxed his hold for a moment and the bullock broke away and was advancing with rapid trot and lowered horns towards the tempting spot of colour in front of it.

All this Jack took in at a glance and his one thought was Eva's danger. There was yet some little distance between her and the angry beast, and he ran rapidly towards her shouting as he ran.

"Run, Eva, run back home; the bullock isn't safe."

The child, startled by the call, looked round, saw the animal bearing down upon her and with a howl of terror turned to fly, but her foot tripped in a rut and she fell face downwards to the ground, roaring lustily. There was no time to pick her up and console her so, little Jack sped past her determined to put his small person between her and the enemy. Behind he saw the farmer and his son in hot pursuit. A moment's delay and the danger would be averted, but Jack was far too young to argue out the matter in cool blood.

All he felt was the necessity of preventing the bullock from reaching Eva, and the spirit inherited from his father made him try to shield her. But the bullock was dashing towards him with lowered horns and wild eyes, and Jack with the instinct of self-preservation raised his arms and threw the parcel he carried straight at its forehead; the bag broke with the force of the blow and the flour it contained came pothering out, blinding and confusing the angry animal. For a moment it stayed its onward course, tossing its head to rid itself of the intolerable dust, and that moment saved the situation, for Farmer Marks, who had taken a short cut across another paddock, came bounding over the fence with his stock-whip in hand and with a tremendous shout and resounding crack of his whip, caused the bullock to turn back and plunge madly towards the field from which it had escaped. It was driven into a far corner, and the gate by which it had escaped was made doubly fast.

"And this afternoon it must be dealt with if I have to put a bullet into it," said the farmer to his son, "but upon my word it was a near shave with the little lad. I never saw a pluckier stand in my life."

Then he hastened back to see what had happened to Jack, and was considerably concerned to see Mrs. Kenyon kneeling on the road by his side, and a grave fear filled him lest, after all, the beast should have gored the boy; but nothing more serious had occurred than that Jack, having nerved himself up to the effort of turning the animal from its course, had suffered from nervous collapse and fainted. Eva, the danger over, had picked herself up and come trotting towards him, had caught sight of his closed eyes and white face and had rushed screaming to the house to fetch her mother, crying that a great big bull had rushed at Jack and he was deaded, deaded in the road, which alarming information had brought Mrs. Kenyon at full speed to the rescue. And there Farmer Marks found her chafing the boy's hands and trying to restore consciousness.

"I'll carry him to your place where you can took after him better," he said, stooping to lift the boy with rough tenderness, and as he carried him he told the story of Jack's plucky defence of the child that was smaller than he.

"You may blame me," he said, "as I should have blamed myself to my dying day if anything had happened to either of them, but after all the thing was an accident. I was acting on Treherne's advice and taking the creature to be put out of harm's way. That it broke from me so suddenly was scarcely my fault. I can only assure you it won't happen again."

"I'm much too thankful a woman to blame anyone," said Mrs. Kenyon, her bright eyes dimmed with tears. "He's coming to, I think; leave him to me, and will you let the Trehernes know that he is here and safe?"

Jack's eyes opened and he looked round him with a puzzled air.

"What's happened? Where's Aunt Betty? I'm all wet," he said.

"It's only a little water I sprinkled on your face," answered Mrs. Kenyon, seized with an insane desire to laugh.

Then, moved by a passion of emotion that swept over her like a flood, she took the little boy in her arms and covered him with kisses.

Jack struggled for freedom, not best pleased with this outburst of affection from a stranger.

"I think, please, now I'll get up and go home to Aunt Betty," he said, but as he spoke the door opened and Aunt Betty with a halo of ruffled hair fringing her forehead came towards him, an undefined fear written in her eyes.

"Jack, Jack, my darling!" was all she said.

Jack held out his arms to her, his face all quivering with the relief of her presence, and to his own great annoyance began to cry. The shock to his system was finding a natural outlet, and he was the only person that regretted the tears.

He was far from feeling a hero as Betty took him home, for Aunt Betty was always a little vexed with him when he cried.

"I didn't mean to cry; I didn't really. My head aches and I feel rather sick. You don't think me a baby, Aunt Betty?"

Betty's smile was radiant with secret exultation and pride.

"Not a baby a bit, Jack, but a jolly brave little nipper who can be trusted to look after any little girl left to his care. Eva will be chums with you after this you may be quite sure, and Eva's mother will feel sure that she will come to no harm with you."

She felt Jack fully deserved this amount of praise, but at the farm very little more was said about the adventure.

"I should hate him to be made into a sort of hero though he is one," she said to Jack's grandmother. "There is not one little boy in a hundred that would have kept his head and known what to do."

So Jack went about the rest of the day a little whiter and quieter than usual, but when night came, and Aunt Betty had tucked him into bed after hearing him say his prayers, he showed some reluctance to let her go, and for once she humoured him and sat down by him for a few minutes.

"It seems—as if something were rushing at me," he said, half ashamed to voice his imaginings.

"There's nothing rushing at you really. It's a trick your tired head is playing on you," said Betty soothingly.

"A great big head with horns and eyes that burn," went on Jack, "a giant's head."

Betty laughed, such a happy contented laugh. "If a giant at all, Jack, it was like one of the giants father told you about. You frightened the big head more than it frightened you. Such a funny thing to do! to throw a bag of flour at the bullock; throwing dust in its eyes with a vengeance, and by the time it got over its surprise it turned round and thought better of it and went back again."

It all sounded so simple and wholesome, that Jack joined in Aunt Betty's laughter.

"It was just because I had nothing else to throw. Do you think father would say I'd frightened a giant."

"He might," said Betty guardedly, "but I know what I must say, that you must go to sleep as quickly as you can. You are a very tired little boy to-night. Good night, dear boy. I'll leave the door open so that if that naughty head does not stop aching you can give me a call."

"He's not a bit himself to-night; he's just a bundle of nerves. I do hope it won't make him timid in future," she said a little anxiously as she rejoined the family in the verandah.

"Not a bit of it," said her father, taking his pipe from his mouth. "I can tell you from practical experience it's not a pleasant feeling to see a creature with horns making a dead set at you. No wonder the child is upset, but in the morning he'll forget all about it."

And Mr. Treherne was right. The only lasting effect of little Jack's adventure was a grave sense of responsibility when he and Eva were together, for she was a girl to be protected and cared for.

It was soon an established fact that the children spent most of their days together, an intimacy that at first was rather a trouble to Mrs. Kenyon, who felt that from mere force of circumstance she could make no adequate return for the kindness shown to her little girl at the farm. Her days were of necessity spent almost entirely from home, as her expectation of obtaining work was fully justified. For half the day, either morning or afternoon, Eva would go with her, but the other half was almost invariably spent with Jack, who was always lurking near the gate in readiness to carry off his playmate. It was in vain for Betty to assure her that this was a satisfactory arrangement for both parties, that before Eva's coming Jack's life had been a lonely one.

"It's delightful for the children, but for your people it must be very often a terrible nuisance; I must think of some way of making things equal, or it cannot go on," said Mrs. Kenyon, not many weeks after her coming.

The opportunity presented itself on the first occasion when Betty brought a message from her mother, asking if Mrs. Kenyon could reserve the next week's work for them.

"Our sewing is all behindhand, and neither mother nor I have anything fit to put on, but if you will devise, fit, and cut out, and we all sit at work together, I think a week will see us through the worst of it."

"It just happens that I'm free next week, and I'll come gladly—as a friend, you understand; exchange is no robbery. Think of all you do for Eva," and Mrs. Kenyon's head lifted with the odd little gesture that Betty was beginning to interpret as a sign that her decision on any subject was final. Neither did Betty try at the present time to combat it.

But she was not pleased about it.

"She's too poor to afford to be so independent, mother," she said, when she went home.

"My dear, let her have her way. We can make it up to her in many forms, which she will not detect. Meanwhile one respects that passionate desire for independence."

"Do you? Carried too far I think it becomes almost a vice. It blocks real friendship. I should like to know Mrs. Kenyon's story. I'm sure she has one."

"When she wishes you to know it she will tell you," said Betty's mother placidly.

The children meanwhile did everything together, or to speak more accurately, whatever Jack did, Eva, his faithful satellite, tried to copy. Happiest of all was she when, tired with play, Jack would sit and tell her stories in which his father played ever a prominent part, and his title in these stories was always "Father Jack, the Giant Killer," a name which Eva received with bursts of laughter.

"I shan't tell you any more if you laugh like that," said Jack one day.

Eva stuffed the corner of her pinafore into her mouth to stay her unseemly merriment.

"But you don't say all that when you see him. You don't say 'Good morning, father Jack, the Giant Killer.'"

"O' course I don't," said Jack with displeased dignity, "but this is a story about the giants father fights. He really fights giants."

Eva's eyes rounded in alarm. "Does he k-kill them like your story says?"

"No, he catches 'em and makes 'em do what he wants. What do you think he's catching now?"

"Goannas," said Eva quickly, whose special terror were the large lizards called iguanas which occasionally invaded the garden, or that she and Jack found about the farm and which Jack drove away with adorable courage.

Jack gave a contemptuous laugh. "What silly things girls are! This is a true story I'm telling you. Father catches the air, at least he rides up in it in a thing called an airy-plane, and he makes the air help to carry him along."

It was neither a very lucid nor accurate description of his father's methods, but it filled his hearer with awe and wonder.

"Not really!"

"But yes," reiterated Jack, "and when I'm old enough, I'll ride in an airy-plane too. Come along; I've told you plenty of stories for to-day. Let's come and play airy-planes," so round and round the paddock scampered the children, with arms outspread like wings, arms which flapped occasionally as the speed became greater to the accompaniment of a whirring sound intended feebly to imitate the buzz of a motor bicycle.

"Faster, faster," cried Jack breathlessly. "Airy-planes flies at an awful rate," but Eva's fat legs were failing her and her arms fell to her side with a little gasp like the wheeze of exhausted bellows.

"Can't—run—no—more," she said, throwing herself on the grass, and Jack after one more triumphant circle threw himself by her side.

Leaning over the gate with his arms folded on the top was a man, who had stood there unperceived, watching the children's play with quiet amusement. Now as it came to an end he laughed aloud, a kindly genial laugh.

"That was really a fine exhibition," he said unlatching the gate and coming towards them, "and deserves a round of applause," and suiting the action to the word he clapped his hands together with all his might.

Jack sprang to his feet, surveying the stranger with frankly questioning eyes, but Eva, too exhausted to speak, sat where she was.

"Did you know what we were playing at? asked Jack.

"I must confess I heard you naming it. You were pretending to be aeroplanes, weren't you? but it was so excellent an imitation that I think I could have guessed. But isn't it rather a tiring game for a little girl like this?"

"I don't know; Eva likes to do what I do, don't you, Eva?"

Eva sat bolt upright and nodded.

"Your little sister, I expect, and a good deal younger than you?"

"Not sister; we're chums, that's all, but it's just as good. She's five, and I'm seven, but I'm big for my age, aren't I?"

The stranger laughed, and seating himself on the grass, drew Jack down beside him.

"Quite big; I thought you might be eight. Having told me this much I must hear a little more. I'm getting interested. May I hear your name?"

"Jack—Jack Stephens; but here they always call me Jack, the Englishman, 'cause father's a captain in the English Navy."

"Ah! I felt somehow that we should be friends. Shake hands, Jack, the Englishman, for I'm an Englishman, too. I've not been long in the colony," and Jack's small hand was almost lost in the palm of his new friend.

"And what does the little girl call herself? I think she has found breath enough to tell me."

Eva lifted a round face dimpled with smiles to the questioner. His deep resonant voice and kindly smile inspired confidence.

"Eva," she said.

"And the rest? You must be something besides Eva," but Eva stood staring at him, not quite understanding the form in which he had put his question. Jack gave her a little nudge. "Tell him, Eva, that your mother is Mrs. Kenyon."

A quick change passed over the face of the listener; the humour of it resolved itself into an earnest gravity.

"Kenyon!" he repeated quickly. "It's a name I know something of. Do father and mother live anywhere near here, Eva? I would rather like to go and see them, if I might."

"Haven't no father," said Eva, with a quick shake of the head. "Never had no father. Mother lives close by."

"Well, come along, Eva. Just take me to see mother. Perhaps she can tell me something of the Kenyon I am seeking. Are you called Eva after mother?"

Eva laughed and shook her head. "No; mother has a hard name to say. I can't always say it just right. Cla—Cla——"

"—rissa," said the strange man, supplying the missing syllables. "Is mother's Christian name Clarissa?"

Eva clapped her hands, jumping up and down with excitement.

"Oh, Jack, he's like the conjurer what tells you things he doesn't ought to know. Isn't it clever of him to find out mummy's name?" But Jack was intently watching the stranger's face, wondering greatly why it twitched as if he were in pain.

"P'raps he's got the toothache," was his solution of the difficulty, not knowing that heartache was the trouble.

"Take me to mummy," said the stranger again, holding out his hand.

"We've telled you both our names; you've not telled us yours."

"That will come later; for the present it's enough for you to know that I'm a bush brother."

The children exchanged bewildered glances; the explanation threw no light upon the stranger.

"We don't know what that means," said Jack, politely.

"That, too, I must tell you at some other time; but now I must get Eva to take me home—home to mummy, home to Clarissa Kenyon."

Greatly wondering, the trio moved towards the gate; but there Jack halted. Some instinct told him that just now he was not wanted, and much as he wished to know the end of this strange story, he determined to go home and wait till he saw Eva again.

He was a little piqued that his new acquaintance was apparently too much absorbed in his own thoughts to take any notice of his leaving, but Eva glanced back with a little nod.

"I'll be back directly dinner's over, Jack. Does you always walk as fast as this?" she went on, glancing up at her companion, whose long stride necessitated a quick trot on her part.

"When I'm in a hurry, Eva; and I'm in a hurry now," and then, dropping the little hot hand he held, he broke into a run, for coming down the lane towards them came Eva's mother, returning from a morning's work to dinner.

And then a strange thing happened, for Eva, who stood stock still with legs set rather far apart, saw mummy give a start backwards as if half frightened by something, then heard her break into a little cry, and the next moment she was caught into the stranger's arms and held tightly to his breast. She did not like such rough treatment! Eva was certain she did not like it, for mummy, who never cried, was sobbing with all her might, great big sobs as if she were angry or hurt. So Eva fled forward, anxious to defend, hammering with all the might of her young fists upon the assailant's legs.

"Let go, let go, you wicked, wicked man," she said. "Don't you see you are hurting my mummy and making her cry? Let go, I say," and the man did let go, smiling down at the child with eyes that were full of tears.

"You can ask mummy for yourself if I've hurt or made her glad," he said very gently.

"Hush, Eva, hush," said Mrs. Kenyon, taking her little daughter by the hand. "You don't understand that I'm crying because I'm glad—gladder than I've been for many a year, so glad that it makes me cry; and all because my brother, your Uncle Tom, has come to see me; and how he got here and how he has found me out remains yet to tell. Come in, come in, my Tom. Let us get into the shelter of the house and let me look at you and make quite sure that it is in very deed my brother Tom who talks to me. But your voice rings true, your dear, kind voice that I had thought never to hear again."

She struggled to the seat in the verandah and pulled him down beside, gazing into his face with hungry eyes. It was bliss enough to look at him after the long lapse of years, to hold his hand between her own, which would hardly cover one of his.

"You always had such big hands, Tom, such big, kind hands that seem to carry help and consolation in their very touch. Oh, how I've wanted you sometimes since—he died."

She did not name her husband, but Tom knew well enough she referred to the father little Eva could not remember.

"But you could have had me for the asking," he said gently.

"I know, I know, but pride would not let me. How could I appeal to you for help when father and Walter—that elder brother of mine—told me that in marrying George I made my final choice between them and him? And you were away, away in Canada, and George just about to return to the colony. We were madly in love, he and I, so I married him and came out with him. I don't say life was easy, Tom; I don't know whether I did right or wrong in marrying George, but I do know this—that from that day to this I never regretted it. He was the dearest and best of men, and we were devoted to each other. I own that when he got ill he suffered agonies of self-reproach in having allowed me to come out with him, but if I had life over again I should have chosen him before all living men. You see father had decided on another match. George, as he lay dying, tried to make me promise to go home, but I told him I never would do it, that I was strong enough and young enough to support myself and the child."

"Young enough, but scarcely strong enough, I take it," said Tom, slipping his arm round the slight frame.

She crept up closer to him. "I don't feel young," she said. "The buffeting of life has made me feel old and cold. If I could forgive father the part he played——"

"Ah, hush," said her brother, "surely you will forgive him, as God will forgive us all. Father died a few months ago."

Clarissa drew herself away, stiffening into stony silence, her hands folded in her lap. Dead! her father dead, and she not a moment since speaking angry, unforgiving words of one who had passed into the presence of the Great White Throne! It was forgiveness for herself that she craved for now, forgiveness for all the hard thoughts she had harboured against him since they parted in such hot anger, forgiveness that in her pride she had made no effort to break through the barrier of silence built up between them. Never a line had she either written to home or received from it since that hasty flight of between six and seven years ago.

Eva, feeling that matters had passed beyond her childish ken, had slipped away into the back garden, and was solacing her loneliness with a game with the new kitten that they had given her up at the farm, so the brother and sister were left alone. Tom understood something of the conflict that was passing in his sister's mind and wisely held his peace. He left her to the teaching of the still small voice which was making itself heard in her heart with gentle insistence.

"I suppose he never forgave me," she said at last.

"I did not hear him mention your name until his last illness. Then, when his mind wandered, your name was often on his lips, showing that you still held your place in his heart. He left you an annuity of £150 a year. Walter tried his level best to track you to tell you about it, but up to this time his search was quite unsuccessful. We wrote to the post-office authorities, but they did not help us; we gave your name to the leading firm of lawyers in Launceston and Hobart, we advertised in the local papers, but nothing came of any of our enquiries. Then I decided to come and work as a bush parson in the colonies for some years before settling down in an English parish, and I thought it not unlikely that I might find some clue to your whereabouts, and all in a moment I found you by the most unlikely means in the world. I stood watching two little children playing in a field near by, went in and made friends with them, and discovered in one of them my own little niece, who brought me straight home to mummy. Some people may call it a happy chance, but I prefer to regard it as a direct Providence."

"What made you come here at all?"

"The fact that your own parson broke down, as you know, quite suddenly, and was ordered away for rest; the bishop knew I was at work somewhere in this neighbourhood, and wrote to ask me if I could combine my peregrinations in the bush with Sunday services in this and the other churches connected with this parish until such time as he can find a locum. He is terribly short-handed at present. I'm very thankful to be able to give my services free of charge, for while the bulk of the property goes with the estate to Walter, my father has left me a sufficient income to make me independent of any stipend from the Church. If I take an English living at some future period it will be one with a simply nominal income that a man without private means could not accept. At present I find my nomadic life so absorbingly interesting that I have no immediate intention of returning home."

"And you will work near here? How wonderful and delightful! What a change one short half-hour has made in life's outlook. Poor father! Did he leave me that annuity out of pity, do you think? No, you need not be afraid that I shall refuse it. My pride is broken down. It seems a poor thing to have let it stand between him and me, and now—I can't even say I'm sorry."

"I forget the exact wording of the will, but I think it said 'lest she should come to want.'"

Clarissa flushed a little. "I have not wanted, but it's been a hard struggle, and if my health had failed"—her voice broke for a moment. "But now, with £150 a year at my back, the worst fear, the one that has kept me awake at nights sometimes, that the child would suffer, is entirely taken away. One can live the simple life out here, none despising you."

"And you think I shall be content to leave it at that?"

"You will have to be content," and his sister slipped her hand into his. "If I needed help at any time I know you will be glad to give it, but I chose my own life in marrying my George, and I'll abide by it. I've no wish to return to England, and what will keep me here in comfort would be grinding poverty at home."

"Walter will never consent to your remaining out here."

Clarissa smiled a little sadly. "He may protest a little, but in his inmost heart he'll not be sorry to leave things as they are. We shall get on quite nicely fifteen thousand miles apart."

A little head peeped round the corner, and a piteous voice made piteous appeal.

"Mummy, I'm not naughty. Mayn't I have my dinner, please? Bush brother can stay if he wants to."

Neither game nor story was needed for the children's amusement that afternoon. They sat side by side on the grass with their heads very close together discussing the exciting event of the morning, the strange man's visit and his puzzling profession; at least Jack was extremely puzzled and not at all satisfied by Eva's explanation.

"He's mummy's brother, don't you see? and my uncle. That's what he means when he says he's a bush brother."

Jack shook his head incredulously. "Mummy's brother and bush brother can't mean the same," he said.

"Pr'aps he calls himself 'bush' 'cause he's got a beard," Eva suggested.

"That's silly! A bush has got nothing to do with a beard."

"Yes, it has," said Eva nodding her head, "birds build in bushes and they build in beards."

Jack fairly screamed with laughter. "Who's stuffed you up with that nonsense?"

"It's not nonsense," said Eva, almost in tears. "It's in a book mummy gave me, and there's a picture of the man and a verse about him too, so it must be true. Mummy teached me the verse."

"Say it, then," said Jack, mockingly, and Eva folded her arms behind her plump little person, knitting her brows in the effort to quicken memory.

"There was an old man with a beard,

Who said 'It's just as I feared,

Two owls and a wren, four larks and a hen

Have all built their nests in my beard.'

"THERE!"

Only capital letters could express the triumph of the final exclamation, but Jack laughed louder and longer than ever.

"But it isn't true," he said.

"O' course it's true. It's in a book, and there's the picture. Mummy shall show you," reiterated Eva, stamping her foot.

The quarrel promised to be a pretty one, when, all unperceived, the man whose beard was under discussion had come into the garden and stood by them. Eva ran towards him, putting her hand in his.

"Uncle Tom, tell him, please. He won't b'lieve me."

"It's all about beards," said Jack. "Eva says birds build in 'em same as they do in bushes, and o' course they don't. It's just nonsense."

"No bird has tried to build in mine at present," said Uncle Tom, stroking his thoughtfully. "What made you think of such a funny thing, Eva?"

It took a minute or two to unravel the thread of the children's discussion, and Uncle Tom sat chuckling to himself as they talked.

"The simplest way of putting the matter straight will be to tell you what I mean by calling myself a bush brother, won't it?"

"Yes," said the children in chorus.

"It's neither being mummy's brother nor the beard I grow that gives me the title——"

Jack gave Eva a nudge.

"But it's the calling that I've chosen for the present. There were a few parsons in England——"

"Oh! it's parsons who are called bush brothers, is it?" asked Jack, a little disappointed at so commonplace an explanation.

"No, not all parsons, but just a few of us who have undertaken a particular kind of work. We heard of Englishmen who had emigrated to the colonies and settled in places very far away from their fellows, who year after year lived out their lonely lives never getting a chance to have their little children baptized, or their sick people visited, whose Sundays were just spent like other days because they had no services to go to, so a few of us banded ourselves together in a sort of brotherhood——"

"What's that mean?" Jack asked.

"A society or company that binds itself together to do the same work, and the work we brothers put before us was to come out to the colonies for a few years and make it our special business to find out all the lonely settlers in the bush and visit them, and try to gather them together for little services. Now you see why we call ourselves bush brothers: because our work lies, not in townships and places such as this, although I am going to be here on Sundays for a little while whilst your clergyman is away on sick leave, but we wander from place to place, to all the most distant homesteads, some of them buried miles and miles away in the bush."

"Does you walk?" asked Eva in her matter-of-fact fashion.

"Sometimes I walk and sometimes, when I know the distance is too great, I hire a horse and ride, and sometimes the way is hard to find, and I get lost. I was lost for two whole days not long ago, and had to camp out at night without either food or shelter. I was glad, I can tell you, when I struck the track again and found myself not far from a farm where they showed me the greatest kindness. I spent a Sunday there, and the farmer and his sons gathered together a few other people not far away, and we had service in a barn, and I baptized three little children that had been born since last a parson had visited them. I stayed there for a week, and gave the children lessons every day, and they were so pleased and eager to learn, poor mites. They did not even know the stories about Jesus when He was a baby. It's not often I find children as ignorant as that, but many of them get very little teaching about the Bible. Very often there is not a Bible in the house. I don't always have tiny congregations. Last Sunday I was miles away up there," pointing to the bush-clad hills which bounded the horizon, "where there are some large lumber works, and quite a lot of men are at work there. So I spent the few days before in making friends with them, and asking them to meet me at service on Sunday, and we had quite a fine service in the open air, and you should have heard the singing. It was glorious."

"I'd like it ever so much better than going to the wooden church down here," said Jack.

Uncle Tom laughed genially. "Aren't you fond of going to church, then?"

"Not very; you've got to sit so quiet. I like the singing though, and it's not so dull now Eva comes too."

"Well, well; we'll see if you can't learn to like it better. Meanwhile, let's have a game before I pay my respects to your grandfather and grandmother."

"Cricket?" cried Jack joyfully.

"Capital! it's ever so long since I played a game of cricket."

Betty, as fresh as the morning in her trim white gown, came out to join the party in the garden, and Jack hastened to introduce her to his new friend.

"Here's Aunt Betty; she'll play too, if you ask her. She's a splendid field, and will catch you out first ball unless you're careful."

Betty and Uncle Tom laughed as they shook hands.

"I've already made friends with your nephew, Miss Treherne, and was coming to call on the rest of you this afternoon, when the children beguiled me by the way. Will you really honour us by joining in our game, though I ask it in fear and trembling after hearing of your prowess?"

"Jack gives me the credit for doing everything better than anyone else, a reputation I find it impossible to sustain, but I love to play."

A very spirited game followed, which ended finally in Betty's catching out the parson, to Jack's unspeakable triumph.

"And after your warning, too," he said, throwing down the bat in comic despair. "And now I must pay my call, and then Eva and I must trot home. My sister said she would be back at six o'clock, and we must be there to meet her."

"I'm so glad you've come; it will be so lovely for Mrs. Kenyon to have one of her own relations with her. I think she has been very lonely."

Uncle Tom turned to the kindling, sympathetic face.

"She would have been desolate indeed without the kindness she has received from you and yours. It was an unhappy chance that separated us, but such separation will be impossible again," said Tom Chance, and that was all the explanation that he felt it needful to offer or that Betty wished to hear.

When Tom and Eva returned at last to the cottage, the sound that greeted them as they entered was vigorous scrubbing, interspersed with fitful singing, and Tom pushed open the door of the inner room to see his sister on her knees scrubbing the floor with might and main, until the boards shone again with whiteness. He put his arms round her and swung her to her feet.

"How dare you do it, Birdie? What shall I say to you for setting to work like that at the end of a long day's sewing?"

The joy of hearing her old pet name, and feeling the masterful touch of his strong hands, brought tears to Clarissa's eyes, but a laugh to her lips.

"It's so good to hear you talk," she said, bending back her face to kiss him, "but I was bound to do it to get the room all fresh and clean for you to-night, for of course you'll come here to your prophet's chamber, just a bed and a chair and candlestick.

"Betty looked in half-an-hour ago, and wanted to do the scrubbing, but I would not let her. That joy was mine, I told her."

"Ah, I saw her slip away as I sat chatting with the old people, but I did not know she was off to lend you a hand."

"Lend a hand! she seems blessed with a dozen pairs, and they are always busy in helping other people, notably me. Had I a sister, she should be made on Betty's model. You must not think that I live in a muddle like this, but a visitor—and such a visitor—has upset the equilibrium of my establishment. Tea is laid out in the verandah. Just give me a moment to tidy my hair and wash my hands, and you will see I've not been unmindful of your creature comforts."

And truly, the meal prepared looked dainty and appetizing.

"I should say the catering of this household runs to extravagance," said her brother, smiling at her.

"Yes, for to-night, it's a case of fatted calf, and besides, I feel money at my back."

In clearing away afterwards, Tom showed himself as handy as any woman. Washing up plates and dishes he declared his speciality!

"But how did you learn it all?" asked Clarissa, pausing in her task of drying the things Tom handed her.