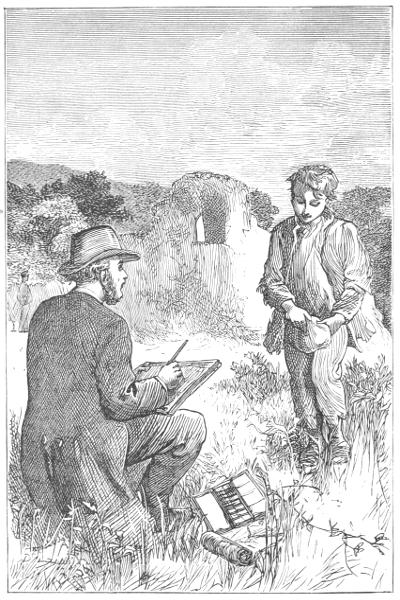

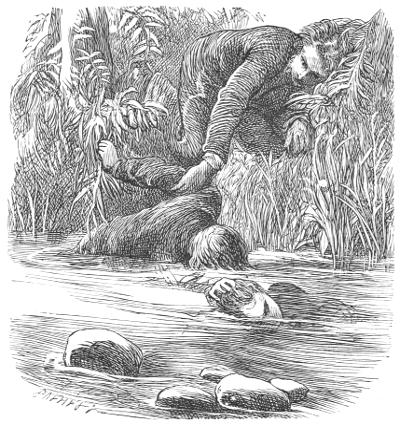

MR. EWART AND MARK.

Title: The Young Pilgrim: A Tale Illustrative of "The Pilgrim's Progress"

Author: A. L. O. E.

Release date: January 31, 2020 [eBook #61280]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Richard Hulse and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

THE

Young Pilgrim.

A Tale

ILLUSTRATIVE OF “THE PILGRIM’S PROGRESS.”

BY

A. L. O. E.,

AUTHOR OF “THE SHEPHERD OF BETHLEHEM,”

“THE SILVER CASKET,” ETC.

With Illustrations.

London:

T. NELSON AND SONS, PATERNOSTER ROW.

EDINBURGH; AND NEW YORK.

1887.

It may perhaps be necessary to give a brief explanation of the object of this little work. It has been written as a Child’s Companion to the Pilgrim’s Progress. That invaluable work is frequently put into youthful hands long before the mind can unravel the deep allegory which it contains; and thus its precious lessons are lost, and it is only perused as an amusing tale.

I would offer my humble work as a kind of translation, the term which was applied to it by a little boy to whom I was reading it in manuscript—a translation of ideas beyond youthful comprehension into the common language of daily life. I would tell the child, through the medium of a simple tale, that Bunyan’s dream is a solemn reality, that the feet of the young may tread the pilgrim’s path, and press on to the pilgrim’s reward.

I earnestly wish that I had been able more completely to carry out the object set before me; but difficulties have arisen from the very nature of my work. I have been obliged to make mine a very free translation, full both of imperfections and omissions. This is more especially the case where subjects are treated of in the Pilgrim’s Progress which concern the deeper experience of the soul. Of fearful inward struggles and temptations, such as befell the author of that work, the gloom and horrors of the Valley of the Shadow of Death, the little ones who early set out on pilgrimage usually know but little. They find the stepping-stones across the Slough of Despond, and are rarely seized by Giant Despair. It would be worse than useless to represent the Christian pilgrimage as more gloomy and painful than children are likely to find it.

There are other valuable parts of the Pilgrim’s Progress, such as the sojourn in the House Beautiful, which is believed by many to represent Christian communion, which could hardly be enlarged upon in a design like mine; while the present altered appearance of Vanity Fair has compelled me to wander still further from my original, if I would draw a picture that could be recognized[7] at the present day, and be useful to the rising generation.

Such as it is, I earnestly pray the Lord of pilgrims to vouchsafe his blessing on my little work. To point out to His dear children the holy guiding light which marks the strait gate and the narrow path of life, and bid them God speed on their way, is an office which I most earnestly desire, yet of which I feel myself unworthy. I may at least hope to lead my young readers to a nobler instructor, to induce them to peruse with greater interest and deeper profit the pages of the Pilgrim’s Progress, and to apply to their own characters and their own lives the precious truths conveyed in that allegory.

A. L. O. E.

| I. | THE PILGRIM’S CALL, | 13 |

| II. | DIFFICULTIES ON SETTING OUT, | 25 |

| III. | MAN’S WAY OF WORKS, | 33 |

| IV. | GOD’S GIFT OF GRACE, | 44 |

| V. | A GLIMPSE OF THE CROSS, | 52 |

| VI. | THE PILGRIM IN HIS HOME, | 62 |

| VII. | THE ARBOUR ON THE HILL, | 68 |

| VIII. | DANGERS, DIFFICULTIES, AND DOUBTS, | 79 |

| IX. | THE ARMOUR AND THE BATTLE, | 90 |

| X. | SHADOW AND SUNSHINE, | 102 |

| XI. | THE TOUCHSTONE OF TRIAL, | 111 |

| XII. | PILGRIMS CONVERSE BY THE WAY, | 122 |

| XIII. | DISTANT GLIMPSE OF VANITY FAIR, | 132 |

| XIV. | VEXATIONS OF VANITY FAIR, | 143 |

| XV. | CITIZENS OF VANITY FAIR, | 151 |

| XVI. | NEW AND OLD COMPANIONS, | 159 |

| XVII. | LIFE IN THE GREAT CITY, | 167 |

| XVIII. | FOGS AND MISTS, | 181 |

| XIX. | DISAPPOINTMENT, | 189 |

| XX. | THE PERILOUS MINE, | 197 |

| [10]XXI. | GREEN PASTURES AND STILL WATERS, | 206 |

| XXII. | A FEW STEPS ASIDE, | 215 |

| XXIII. | REGRETS, BUT NOT DESPAIR, | 230 |

| XXIV. | A NEW DANGER, | 239 |

| XXV. | THE LAKE AMONG THE ROCKS, | 253 |

| XXVI. | COMING TO THE RIVER, | 264 |

| XXVII. | THE CLOSE OF THE PILGRIMAGE, | 271 |

| XXVIII. | CONCLUSION, | 280 |

| MR. EWART AND MARK, | Frontispiece |

| AT THE GATE, | 14 |

| MARK AND HIS MOTHER, | 29 |

| HERDING SHEEP, | 39 |

| AT THE CHURCH, | 57 |

| MARK’S KINDNESS, | 67 |

| MARK’S INDIGNATION AT DECEIT, | 76 |

| MARK RESTORING THE LOST BIBLE, | 86 |

| MARK DISCOVERED BY LORD FONTONORE, | 105 |

| CHARLES’S STRUGGLE, | 117 |

| CHARLES AND HIS MOTHER’S PORTRAIT, | 140 |

| CLEMENTINA AT THE PIANO, | 149 |

| RETURNING FROM CHURCH, | 162 |

| THE PARTING WITH MR. EWART, | 169 |

| THE CONVERSATION IN THE PARK, | 179 |

| DRESSED FOR THE BALL, | 188 |

| CLEMENTINA AND ERNEST, | 192 |

| CHARLES AND FITZWIGRAM, | 204 |

| MR. STAINES AND THE TUTOR, | 218 |

| THE DISMISSAL, | 228 |

| THE CONFESSION AND ENTREATY, | 233 |

| THE NEW TUTOR, | 242 |

| THE APOLOGY, | 251 |

| THE RESCUE, | 260 |

| JACK RECEIVING THE BIBLE, | 276 |

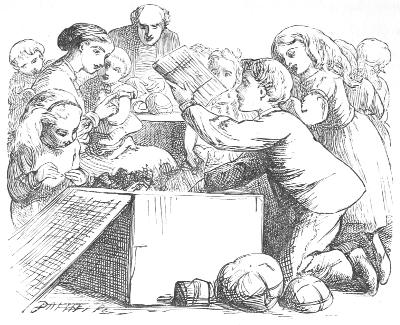

| THE WELCOME BOX, | 284 |

| THE NEW BOOK, | 285 |

“I dreamed, and, behold, I saw a man clothed with rags standing in a certain place, with his face from his own house, a book in his hand, and a great burden upon his back.”—Pilgrim’s Progress.

“Is this the way to the ruins of St. Frediswed’s shrine?” said a clergyman to a boy of about twelve years of age, who stood leaning against the gate of a field.

“They are just here, sir,” replied the peasant, proceeding to open the gate.

“Just wait a moment,” cried a bright-haired boy who accompanied the clergyman; “that is your way, this is mine,” and he vaulted lightly over the gate.

“So these are the famous ruins!” he exclaimed as he alighted on the opposite side; “I don’t think much of them, Mr. Ewart. A few yards of stone wall, half[14] covered with moss, and an abundance of nettles is all I can see.”

AT THE GATE.

“And yet this once was a famous resort for pilgrims.”

“Pilgrims,—what were they?” inquired the boy.

“In olden times, when the Romanist religion prevailed in England, it was thought an act of piety to visit certain places that were considered particularly holy; and those who undertook journeys for this purpose received the name of pilgrims. Many travelled thousands of miles to kneel at the tomb of our Lord in Jerusalem, and those who could not go so far believed that by visiting[15] certain famous shrines here, they could win the pardon of their sins. Hundreds of misguided people, in this strange, superstitious hope, visited the abbey by whose ruins we now stand; and I have heard that a knight, who had committed some great crime, walked hither barefoot, with a cross in his hand, a distance of several leagues.”

“A knight barefoot! how strange!” cried young Lord Fontonore; “but then he believed that it would save him from his sins.”

“Save him from his sins!” thought the peasant boy, who, with his full earnest eyes fixed upon Mr. Ewart, had been drinking in every word that he uttered; “save him from his sins! I should not have thought it strange had he crawled the whole way on his knees!”

“Are there any pilgrims now?” inquired Fontonore.

“In Romanist countries there are still many pilgrimages made by those who know not, as we do, the one only way by which sinners can be accounted righteous before a pure God. But in one sense, Charles, we all should be pilgrims, travellers in the narrow path that leads to salvation, passing on in our journey from earth to heaven, with the cross not in our hands but in our hearts; pilgrims, not to the tomb of a crucified Saviour, but to the throne of that Saviour in glory!”

Charles listened with reverence, as he always did when his tutor spoke of religion, but his attention was nothing[16] compared to that of the peasant, who for the first time listened to conversation on a subject which had lately been filling all his thoughts. He longed to speak, to ask questions of the clergyman, but a feeling of awe kept him back; he only hoped that the gentleman would continue to talk, and felt vexed when he was interrupted by three children who ran up to the stranger to ask for alms.

“Begging is a bad trade, my friends,” said Mr. Ewart gravely, “I never like to encourage it in the young.”

“We’re so hungry,” said the youngest of the party.

“Mother’s dead, and father’s broke his leg!” cried another.

“We want to get him a little food,” whined the third.

“Do you live near?” asked Mr. Ewart.

“Yes sir, very near.”

“I will go and see your father,” said the clergyman.

The little rogues, who were accustomed to idle about the ruin to gain pence from visitors by a tale of pretended woe, looked at each other in some perplexity at the offer, for though they liked money well enough, they were by no means prepared for a visit. At last Jack, the eldest, said with impudent assurance, “Father’s not there, he’s taken to the hospital, there’s only mother at home.”

“Mother! you said just now that your mother was dead.”

“I meant—” stammered the boy, quite taken by surprise; but the clergyman would not suffer him to proceed.

“Do not add another untruth, poor child, to those which you have just uttered. Do you not know that there is One above the heavens who hears the words of your lips, reads the thoughts of your hearts—One who will judge, and can punish?”

Ashamed and abashed, the three children made a hasty retreat. As soon as they were beyond sight and hearing of the strangers, Jack turned round and made a mocking face in their direction, and Madge exclaimed in an insolent tone, “We weren’t going to stop for his sermon.”

“There’s Mark there that would take it in every word, and thank him for it at the end,” said Jack.

“Oh, Mark’s so odd!” cried Ben; “he’s never like anybody else. No one would guess him for our brother!”

These words were more true than Ben’s usually were, for the bright-haired young noble himself scarcely offered a greater contrast to the ragged, dirty children, than they with their round rustic faces, marked by little expression but stupidity on that of Ben, sullen obstinacy on Madge’s, and forward impudence on Jack’s, did to the expansive brow and deep thoughtful eye of the boy whom they had spoken of as Mark.

“Yes,” said Jack, “he could never even pluck a wild-flower, but he must be pulling it to bits to look at all its parts. It was not enough to him that the stars shine to[18] give us light, he must prick out their places on an old bit of paper, as if it mattered to him which way they were stuck. But of all his fancies he’s got the worst one now; I think he’s going quite crazed.”

“What’s he taken into his head?” said Madge.

“You remember the bag which the lady dropped at the stile, when she was going to the church by the wood?”

Madge nodded assent, and her brother continued: “What fun we had in carrying off and opening that bag, and dividing the things that were in it! Father had the best of the fun of it though, for he took the purse with the money.”

“I know,” cried Ben, “and mother had the handkerchief with lace round the edge, and E. S. marked in the corner. We—more’s the shame!—had nothing but some pence, and the keys; and Mark, as the biggest, had the book.”

“Ah! the book!” cried Jack; “that’s what has put him out of his wits!”

“No one grudged it him, I’m sure,” said Ben, “precious little any of us would have made out of it. But Mark takes so to reading, it’s so odd; and it sets him a thinking, a thinking: well, I can’t tell what folk like us have to do with reading and thinking!”

“Nor I!” cried both Madge and Jack.

“I shouldn’t wonder,” said the latter, as stretched on[19] the grass he amused himself with shying stones at the sparrows, “I shouldn’t wonder if his odd ways had something to do with that red mark on his shoulder!”

“What, that strange mark, like a cross, which made us call him the Red-cross Knight, after the ballad which mother used to sing us?”

“Yes; I never saw a mark like that afore, either from blow or burn.”

“Mother don’t like to hear it talked of,” said Madge.

“Well, whatever has put all this nonsense into his head, father will soon knock it out of him when he comes back!” cried Jack. “He’s left off begging,—he won’t ask for a penny, and he used to get more than we three together, ’cause ladies said he looked so interesting; and he’ll not so much as take an egg from a nest,—he’s turned quite good for nothing!”

Leaving the three children to pursue their conversation, we will return to him who was the subject of it. That which had made them scoff had made him reflect,—he could not get rid of those solemn words, “There is One above the heavens who hears the words of your lips, reads the thoughts of your hearts—One who will judge, and can punish!” They reminded him of what he had read in his book, The soul that sinneth it shall die; he knew himself to be a sinner, and he trembled.

Little dreaming what was passing in the mind of the peasant, Mr. Ewart examined the ruin without noticing[20] him further, and Mark still leant on the gate, a silent, attentive listener.

“I think, Charles,” said the tutor, “that I should like to make a sketch of this spot, I have brought my paint-box and drawing block with me, and if I could only procure a little water—”

“Please may I bring you some, sir?” said Mark.

The offer was accepted, and the boy went off at once, still turning in his mind the conversation that had passed.

“‘Pilgrims in the narrow path that leadeth to salvation,’—I wish that I knew what he meant. Is that a path only for holy men like him, or can it be that it is open to me? Salvation! that is safety, safety from punishment, safety from the anger of the terrible God. Oh, what can I do to be saved!”

In a few minutes Mark returned with some fresh water which he brought in an old broken jar. He set it down by the spot where Mr. Ewart was seated.

“Thanks, my good lad,” said the clergyman, placing a silver piece in his hand.

“Good,” repeated Mark to himself; “he little knows to whom he is speaking.”

“It would be tedious to you, Charles, to remain beside me while I am sketching,” said Mr. Ewart; “you will enjoy a little rambling about; only return to me in an hour.”

“I will explore!” replied the young lord gaily;[21] “there is no saying what curiosities I may find to remind me of the pilgrims of former days.”

And now the clergyman sat alone, engaged with his paper and brush, while Mark watched him from a little distance, and communed with his own heart.

“He said that he knew the one, only way by which sinners could be accounted righteous—righteous! that must mean good—before a holy God! He knows the way; oh, that he would tell it to me! I have half a mind to go up to him now; it would be a good time when he is all by himself.” Mark made one step forward, then paused. “I dare not, he would think it so strange. He could not understand what I feel. He has never stolen, nor told lies, nor sworn; he would despise a poor sinner like me. And yet,” added the youth with a sigh, “he would hardly sit there, looking so quiet and happy, if he knew how anxious a poor boy is to hear of the way of salvation, which he says that he knows. I will go nearer; perhaps he may speak first.”

Mr. Ewart had begun a bold, clever sketch,—stones and moss, trees and grass were rapidly appearing on the paper, but he wanted some living object to give interest to the picture. Naturally his eye fell upon Mark, in his tattered jacket and straw hat, but he forgot his sketch as he looked closer at the boy, and met his sad, anxious gaze.

“You are unhappy, I fear,” he said, laying down his pencil.

Mark cast down his eyes, and said nothing.

“You are in need, or you are ill, or you are in want of a friend,” said the clergyman with kind sympathy in his manner.

“Oh, sir, it is not that—” began Mark, and stopped.

“Come nearer to me, and tell me frankly, my boy, what is weighing on your heart. It is the duty, it is the privilege of the minister of Christ to speak comfort to those who require comfort.”

“Can you tell me,” cried Mark, with a great effort, “the way for sinners—to be saved?”

“The Saviour is the Way, the Truth, and the Life, the Gate by which alone we enter into salvation. Believe on the Lord Jesus Christ and thou shalt be saved. The just shall live by faith.”

“What is faith?” said Mark, gathering courage from the gentleness with which he was addressed.

“Faith is to believe all that the Bible tells us of the Lord, His glory, His goodness, His death for our sins, to believe all the promises made in His Word, to rest in them, hope in them, make them our stay, and love Him who first loved us. Have you a Bible, my friend?”

“I have.”

“And do you read it?”

“Very often,” replied Mark.

“Search the Scriptures, for they are the surest guide; search them with faith and prayer, and the Lord will[23] not leave you in darkness, but guide you by his counsel here, and afterward receive you to glory.”

Mr. Ewart did not touch his pencil again that day, his sketch lay forgotten upon the grass. He was giving his hour to a nobler employment, the employment worthy of angels, the employment which the Son of God Himself undertook upon earth. He was seeking the sheep lost in the wilderness, he was guiding a sinner to the truth.

“I hope that I have not kept you waiting,” exclaimed Charles, as he came bounding back to his tutor; “the carriage has come for us from the inn; it looks as if we should have rain, we must make haste home.”

Mr. Ewart, who felt strongly interested in Mark, now asked him for his name and address, and noted down both in his pocket-book. He promised that, if possible, he would come soon and see him again.

“Keep to your good resolutions,” said the clergyman, as he walked towards the carriage, accompanied by Charles; “and remember that though the just shall live by faith, it is such faith as must necessarily produce repentance, love, and a holy life.”

Mr. Ewart stepped into the carriage, the young lord sprang in after him, the servant closed the door and they drove off. Mark stood watching the splendid equipage as it rolled along the road, till it was at last lost to his sight.

“I am glad that I have seen him—I am so glad that he spoke to me—I will never forget what he said! Yes, I will keep to my good resolutions; from this hour I will be a pilgrim to heaven, I will enter at once by the strait gate, and walk in the narrow way that leadeth unto life!”

“They drew nigh to a very miry slough, that was in the midst of the plain; and they being heedless, did both fall suddenly into the bog. The name of the slough was Despond.”—Pilgrim’s Progress.

Evening had closed in with rain and storm, and all the children had returned to the cottage of their mother. A dirty, uncomfortable abode it looked, most unlike those beautiful little homes of the peasant which we see so often in dear old England, with the ivy-covered porch, and the clean-washed floor, the kettle singing merrily above the cheerful fire, the neat rows of plates ranged on the shelf, the prints upon the wall, and the large Bible in the corner.

No; this was a cheerless-looking place, quite as much from idleness and neglect as from poverty. The holes in the window were stuffed with rags, the little garden in front held nothing but weeds, the brick floor appeared as though it had never been clean, and everything lay about in confusion. An untidy-looking woman, with[26] her shoes down at heel, and her hair hanging loose about her ears, had placed the evening meal on the table; and round it now sat the four children, busy with their supper, but not so busy as to prevent a constant buzz of talking from going on all the time that they ate.

“I say, Mark,” cried Jack, “what did the parson pay you for listening to him for an hour?”

“How much did you get out of him?” said Madge.

“Any money?” asked Ann Dowley, looking up eagerly.

Mark laid sixpence on the table.

“I daresay that you might have got more,” said Ben.

“I did get more—but not money.”

“What, food, or clothes, or—”

“Not food, nor clothes, but good words, which were better to me than gold.”

This announcement was received with a roar of laughter, which did not, however, disconcert Mark.

“Look you,” he said, as soon as they were sufficiently quiet to hear him, “look you if what I said be not true. You only care for things that belong to this life, but it is no more to be compared to the life that is to come than a candle to the sun, or a leaf to the forest! Why, where shall we all be a hundred years hence?”

“In our graves, to be sure,” said Ben.

“That is only our bodies—our poor, weak bodies; but our souls, that think, and hope, and fear, where will they be then?”

“We don’t want to look on so far,” observed Jack.

“But it may not be far,” exclaimed Mark. “Thousands of children die younger than we, there are many, many small graves in the churchyard; death may be near to us, it may be close at hand, and where will our souls be then?”

“I don’t know,” said Madge; “I don’t want to think,” subjoined her elder brother; their mother only heaved a deep sigh.

“Is it not something,” continued Mark, “to hear of the way to a place where our souls may be happy when our bodies are dust? Is it not something to look forward to a glorious heaven, where millions and millions of years may be spent amongst joys far greater than we can think, and yet never bring us nearer to the end of our happiness and glory?”

“Oh, these are all dreams,” laughed Jack, “that come from reading in that book.”

“They are not dreams!” exclaimed Mark, with earnestness, “they are more real than anything on earth. Everything is changing here, nothing is sure; flowers bloom one day and are withered the next; now there is sunshine, and now there is gloom; you see a man strong and healthy, and the next thing you hear of[28] him perhaps is his death! All things are changing and passing away, just like a dream when we awake; but heaven and its delights are sure, quite sure; the rocks may be moved—but it never can be changed; the sun may be darkened—it is all bright for ever!”

“Oh that we might reach it!” exclaimed Ann Dowley, the tears rising into her eyes. Her sons looked at her in wonder, for they had never known their mother utter such a sentence before. To them Mark’s enthusiasm seemed folly and madness, and they could not hide their surprise at the effect which it produced upon one so much older than themselves.

Ann Dowley had been brought up to better things, and had received an education very superior to the station in which she had been placed by her marriage. For many years she had been a servant in respectable families, and though all was now changed—how miserably changed!—she could not forget much that she had once seen and heard. She was not ignorant, though low and coarse-minded, and it was perhaps from this circumstance that her family were decidedly more intelligent than country children of their age usually are. Ann could read well, but her only stock of books consisted of some dirty novels, broken-backed and torn—she would have done well to have used them to light the fire. She was one who had never cared much for religion, who had not sought the Creator in the days of[29] her youth; but she was unhappy now, united to a husband whom she dreaded, and could not respect—whose absence for a season was an actual relief; she was poor, and she doubly felt the sting of poverty from having once been accustomed to comfort—and Mark’s description of peace, happiness, and joy, touched a chord in her heart that had been silent for long.

MARK AND HIS MOTHER.

“You too desire to reach heaven!” cried Mark, with animation sparkling in his eyes; “oh, mother, we will be pilgrims together, struggle on together in the narrow way, and be happy for ever and ever!”

The three younger children, who had no taste for conversation such as this, having finished their meal slunk into the back room, to gamble away farthings as they had learned to do from their father. Ann sat down by the fire opposite to Mark, a more gentle expression than usual upon her face, and pushing back the hair from her brow, listened, leaning on her hand.

“I will tell you, mother, what the clergyman told me—I wish that I could remember every word. He said that God would guide us by his counsel here, and afterward receive us to glory. And he spoke of that glory, that dazzling, endless glory! Oh, mother, how wretched and dark seems this earth when we think of the blessedness to come!”

“But that blessedness may not be for us,” said Ann.

“He said that it was for those who had faith, who believed in the Lord Jesus Christ.”

“I believe,” said the woman, “I never doubted the Bible; I used to read it when I was a child.”

“We will read mine together now, mother.”

“And what more did the clergyman tell you?”

“He told me that the faith which brings us to heaven will be sure to produce—” Mark paused to recall the exact words—“repentance, love, and a holy life.”

“A holy life!” repeated Ann, slowly. Painful thoughts crossed her mind of many things constantly[31] done that ought not to be done, habits hard to be parted with as a right hand or a right eye; holiness seemed something as far beyond her reach as the moon which was now rising in the cloudy sky; she folded her hands with a gloomy smile, and said, “If that be needful, we may as well leave all these fine hopes to those who have some chance of winning what they wish!”

“The way is not shut to us.”

“I tell you that it is,” said the woman, impatiently; for the little gleam of hope that had dawned on her soul had given place to sullen despair. “To be holy you must be truthful and honest—we are placed in a situation where we cannot be truthful, we cannot be honest, we cannot serve God! It is all very well for the rich and the happy; the narrow way to them may be all strewed with flowers, but to us it is closed—and for ever!” She clenched her hand with a gesture of despair.

“But, mother—”

“Talk no more,” she said, rising from her seat; “do you think that your father would stand having a saint for his wife, or his son! We have gone so far that we cannot turn back, we cannot begin life again like children—never speak to me again on these matters!” and, so saying, Ann quitted the room, further than ever from the strait gate that leadeth unto life, more determined to pursue her own unhappy career.

The heart of Mark sank within him. Here was disappointment to the young pilgrim at the very outset: fear, doubt, and difficulty enclosed him round, and hope was but as a dim, distant light before him. But help seemed given to the lonely boy, more lonely amid his unholy companions than if he had indeed stood by himself in the world. He looked out on the pure, pale moon in the heavens: the dark clouds were driving across her path, sometimes seeming to blot her from the sky; then a faint, hazy light would appear from behind them; then a slender, brilliant rim would be seen; and at last the full orb would shine out in glory, making even the clouds look bright!

“See how these clouds chase each other, and crowd round the moon, as if they would block up her way!” thought Mark. “They are like the trials before me now, but bravely she keeps on her path through all and I must not—I will not despair!”

“Now as Christian was walking solitarily by himself, he espied one afar off come crossing over the field to meet him; and their hap was to meet just as they were crossing the way of each other. The gentleman’s name that met him was Mr. Worldly Wiseman.”—Pilgrim’s Progress.

The bright morning dawned upon Holyby, the storm had spent itself during the night, and nothing remained to mark that it had been but the greater freshness of the air, clearness of the sky, and the heavy moisture on the grass that sparkled in the sun.

As the young pilgrim sat under an elm-tree, eating the crust which served him for a breakfast, and meditating on the events and the resolutions of the last day, Farmer Joyce came riding along the road, mounted on a heavy horse which often did service in the plough, and drew up as he reached the boy.

“I say, Mark Dowley,” he called in a loud, hearty voice, “you are just the lad I was looking for!”

“Did you want me?” said Mark, raising his eyes.

“Do you know Mr. Ewart?” cried the farmer; and on Mark’s shaking his head, continued, “why, he was talking to me about you yesterday—a clergyman, a tall man with a stoop—he who is tutor to Lord Fontonore.”

“Oh, yes!” cried Mark, springing up, “but I did not know his name. What could he be saying of me?”

“He stopped at my farm on his drive home yesterday, and asked me if I knew a lad called Mark Dowley, and what sort of character he bore. Says I,” continued the farmer, with a broad smile on his jovial face, “I know nothing against that boy in particular, but he comes of a precious bad lot!”

“And what did he reply?” cried Mark, eagerly.

“Oh, a great deal that I can’t undertake to repeat, about taking you out of temptation, and putting you in an honest way; so the upshot of it is that I agreed to give you a chance, and employ you myself to take care of my sheep, to see if anything respectable can be made of you.”

“How good in him—how kind!” exclaimed Mark.

“It seems that you got round him—that you found his weak side, young rogue! You had been talking to him of piety and repentance, and wanting to get to heaven. But I’ll give you a word of advice, my man, better than twenty sermons. You see I’m thriving and prosperous enough, and well respected, though I should not say so, and I never wronged a man in my life. If[35] you would be the same, just mind what I say, keep the commandments, do your duty, work hard, owe nothing, and steer clear of the gin-shop, and depend upon it you’ll be happy now, and be sure of heaven at the last.”

“Mr. Ewart said that by faith—”

“Faith!” exclaimed the farmer, not very reverently; “don’t trouble yourself with things quite above you—things which you cannot understand. It is all very well for a parson like him—a very worthy man in his way, I believe, but with many odd, fanciful notions. My religion is a very simple one, suited to a plain man like me; I do what is right, and I expect to be rewarded; I go on in a straightforward, honest, industrious way, and I feel safer than any talking and canting can make one. Now you mind what you have heard, Mark Dowley, and come up to my farm in an hour or two. I hope I’ll have a good account to give of you to the parson; and the young lord, he too seemed to take quite an interest in you.”

“Did he?” said Mark, somewhat surprised.

“Yes, it’s odd enough, with such riches as he has, one would have thought that he had something else to think of than a beggar boy. Why, he has as many thousands a-year as there are sheaves in that field!”

“He had a splendid carriage and horses.”

“Carriage! he might have ten for the matter of that. They say he has the finest estate in the county of York;[36] but I can’t stay here idling all day,” added the farmer; “you come up to my place as I said, and remember all you’ve heard to-day. I have promised to give you a trial; but mark me, my lad, if I catch you at any of your old practices, that moment you leave my service. So, honesty is the best policy, as the good old proverb says.” With that he struck his horse with the cudgel which he carried in his hand, and went off at a slow, heavy trot.

“There is a great deal of sense in what he has said,” thought Mark, as he turned in the direction of Anne’s cottage to tell her of his new engagement. “‘Keep the commandments, work hard, and steer clear of the gin-shop, and you’ll be sure of heaven at the last!’ These are very plain directions any way, and I’m resolved to follow them from this hour. Some of my difficulties seem clearing away; by watching the sheep all the day long I shall be kept from a good many of my temptations. I shall have less of the company of my brothers, I shall earn my bread in an honest way, and yet have plenty of time for thought. ‘Keep the commandments,’ let me think what they are;” and he went over the ten in his mind, as he learned them from his Bible. “I think that I may manage to keep them pretty strictly, but there are words in the Word of God which will come to my thoughts. A new commandment I give you, that ye love one another: and, He that hateth his[37] brother is a murderer;—how can I love those who dislike me?—’tis impossible; I don’t believe that any one could.”

The first thing that met the eyes of Mark on his entering the cottage put all his good resolutions to flight. Jack and Ben were seated on the brick floor, busy in patching up a small broken box, and as they wanted something to cut up for a lid, they had torn off the cover from his beautiful Bible, and thrown the book itself under the table! Mark darted forward with an oath—alas! his lips had been too long accustomed to such language for the habit of using it to be easily broken, though he never swore except when taken by surprise, as in this instance. He snatched up first the cover, and then the book, and with fiery indignation flashing in his eyes, exclaimed, “I’ll teach you how to treat my Bible so!”

“Your Bible!” exclaimed Ben, with a mocking laugh; “Mark thinks it no harm to steal a good book, but it’s desperate wicked to pull off its cover!”

“Oh, that’s what the parson was teaching him!” cried Jack. Provoked beyond endurance, Mark struck him.

“So it’s that you’re after!” exclaimed Jack, springing up like a wild cat, and repaying the blow with interest. He was but little younger than Mark, and of much stronger make, therefore at least his match in a struggle. The boys were at once engaged in fierce[38] fight, while Ben sat looking on at the unholy strife, laughing, and shouting, and clapping his hands, and hallooing to Jack to “give it him!”

“What are you about there, you bad boys?” exclaimed Ann, running from the inner room at the noise of the scuffle. Jack had always been her favourite son, and without waiting to know who had the right in the dispute, she grasped Mark by the hair, threw him violently back, and, giving him a blow with her clenched hand, cried, “Get away with you, sneaking coward that you are, to fight a boy younger than yourself!”

“You always take his part, but he’ll live to be your torment yet!” exclaimed Mark, forgetting all else in the blind fury of his passion.

“He’ll do better than you, with all your canting,” cried Ann. The words in a moment recalled Mark to himself; what had he been doing? what had he been saying? he, the pilgrim to heaven; he, the servant of God! With a bitterness of spirit more painful than any wrong which could have been inflicted upon him by another, he took up the Bible which had been dropped in the struggle, and left the cottage without uttering a word.

HERDING SHEEP.

Mortifying were Mark’s reflections through that day, as he sat tending his sheep. “Keep the commandments!” he sadly murmured to himself; “how many have I broken in five minutes! I took God’s name in vain—a terrible sin. It is written, Above all things[39] swear not. I did not honour my mother, I spoke insolently to her. I broke the sixth commandment by hating my brother; I struck him; I felt as though I could have knocked him down and trampled upon him! How can I reach heaven by keeping the commandments? I could as well get up to those clouds by climbing a tree. Well, but I’ll try once again, and not give up[40] yet. There is no one to provoke me, no one to tempt me here; I can be righteous at least when I am by myself.”

So Mark sat long, and read in his Bible, mended it as well as he could, and thought of Mr. Ewart and his words. Presently his mind turned to Lord Fontonore, the fair, bright-haired boy who possessed so much wealth, who was placed in a position so different from his own.

“He must be a happy boy indeed!” thought Mark, “with food in abundance, every want supplied, not knowing what it is to wish for a pleasure and not have it at once supplied. He must be out of the way of temptation too, always under the eye of that kind, holy man, who never would give a rough word, I am sure, but would always be leading him right. It is very hard that there are such differences in the world, that good things are so very unevenly divided. I wish that I had but one quarter of his wealth; he could spare it, no doubt, and never feel the loss.” Without thinking what he was doing, Mark turned over a leaf of the Bible which lay open upon his knee. Thou shalt not covet, were the first words that met his gaze; Mark sighed heavily, and closed the book.

“So, even when I am alone, I am sinning still; coveting, repining, murmuring against God’s will, with no more power to stand upright for one hour than this weed which I have plucked up by the roots. And yet the soul that sinneth it shall die. I cannot get rid of these[41] terrible words. I will not think on this subject any more, it only makes me more wretched than I was. Oh! I never knew, till I tried it to-day, how hard, how impossible it is to be righteous before a holy God!”

So, tempted to banish the thought of religion altogether from his mind, because he felt the law to be too holy to be kept unbroken, yet dreading the punishment for breaking it, Mark tried to turn his attention to other things. He watched the sheep as they grazed, plucked wild-flowers and examined them, and amused himself as best he might.

The day was very hot, there was little shade in the field, and Mark grew heated and thirsty. He wished that there were a stream running through the meadow, his mouth felt so parched and dry.

On one side of the field there was a brick wall, dividing it from the garden belonging to Farmer Joyce. On the top of this grew a bunch of wild wall-flower, and Mark, who was particularly fond of flowers, amused himself by devising means to reach it. There was a small tree growing not very far from the spot, by climbing which, and swinging himself over on the wall, he thought that he might succeed in obtaining the prize. It would be difficult, but Mark rather liked difficulties of this sort, and anything at that time seemed pleasanter than thinking.

After one or two unsuccessful attempts, the boy found[42] himself perched upon the wall; but the flower within his reach was forgotten. He looked down from his height on the garden below, with its long lines of fruit-bushes, now stripped and bare, beds of onions, rows of beans, broad tracts of potatoes, all the picture of neatness and order. But what most attracted the eye of the boy was a splendid peach-tree, growing on the wall just below him, its boughs loaded with rich tempting fruit. One large peach, the deep red of whose downy covering showed it to be so ripe that one might wonder that it did not fall from the branch by its own weight, lay just within reach of his hand. The sight of that fruit, that delicious fruit, made Mark feel more thirsty than ever. He should have turned away, he should have sprung from the wall; but he lingered and looked, and looking desired, then stretched out his hand to grasp. Alas for his resolutions! alas for his pilgrim zeal! Could so small a temptation have power to overcome them?

Yet let the disadvantages of Mark’s education be remembered: he had been brought up with those to whom robbing an orchard seemed rather a diversion than a sin. His first ardour for virtue had been chilled by failure; and who that has tried what he vainly attempted does not know the effect of that chill? With a hesitating hand Mark plucked the ripe peach; he did not recollect that it was a similar sin which once[43] plunged the whole earth into misery—that it was tasting forbidden fruit which brought sin and death into the world. He raised it to his lips, when a sudden shout from the field almost caused him to drop from the wall.

“Holloa there, you young thief! Are you at it already? Robbing me the very first day! Come down, or I’ll bring you to the ground with a vengeance!” It was the angry voice of the farmer.

Mark dropped from his height much faster than he had mounted, and stood before his employer with his face flushed to crimson, and too much ashamed to lift up his eyes.

“Get you gone,” continued the farmer, “for a hypocrite and a rogue; you need try none of your canting on me. Not one hour longer shall you remain in my employ; you’re on the high road to the gallows.”

Mark turned away in silence, with an almost bursting heart, and feelings that bordered on despair. With what an account of himself was he to return to his home, to meet the scoffs and jests which he had too well deserved? What discredit would his conduct bring on his religion! How his profane companions would triumph in his fall! The kind and pitying clergyman would regard him as a hypocrite—would feel disappointed in him. Bitter was the thought. All his firm resolves had snapped like thread in the flame, and his hopes of winning heaven had vanished.

“Ye cannot be justified by the works of the law; for by the deeds of the law no man living can be rid of his burden.”—Pilgrim’s Progress.

“What ails you my young friend?—has anything painful happened?” said a kindly voice, and a hand was gently laid upon the shoulder of Mark, who was lying on the grass amidst the ruins of the old Abbey, his face leaning on his arms, and turned towards the earth, while short convulsive sobs shook his frame.

“Oh, sir!” exclaimed Mark, as a momentary glance enabled him to recognize Mr. Ewart.

“Let me know the cause of your sorrow,” said the clergyman, seating himself on a large stone beside him. “Rise, and speak to me with freedom.”

Mark rose, but turned his glowing face aside; he was ashamed to look at his companion.

“Sit down there,” said Mr. Ewart, feeling for the boy’s evident confusion and distress; “perhaps you are not yet aware that I have endeavoured to serve you—to procure you a situation with Farmer Joyce?”

“I have had it, and lost it,” replied Mark abruptly.

“Indeed, I am sorry to hear that. I trust that no fault has occasioned your removal.”

“I stole his fruit,” said Mark, determined at least to hide nothing from his benefactor; “he turned me off, and he called me a hypocrite. I am bad enough,” continued the boy, in an agitated tone; “no one but myself knows how bad; but I am not a hypocrite—I am not!”

“God forbid!” said Mr. Ewart; “but how did all this happen?”

“I was thirsty, it tempted me, and I took it. I broke all my resolutions, and now he cast me off, and you will cast me off, and the pure holy God, He will cast me off too! I shall never be worthy of heaven!”

“Did you think that you could ever be worthy of heaven?” said the clergyman, and paused for a reply. Then receiving none from Mark, he continued—“Not you, nor I, nor the holiest man that ever lived, One excepted, who was not only man, but God, was ever worthy of the kingdom of heaven.”

Mark looked at him in silent surprise.

“We are all sinners, Mark; all polluted with guilt. Not one day passes in which our actions, our words, or our thoughts, would not make us lose all title to eternal life. The Bible says, ‘There is not one that doeth good, no, not one.’ Every living soul is included under sin.”

“How can this be?” said Mark, who had looked upon the speaker as one above all temptation or stain.

“Since Adam, our first parent, sinned and fell, all his children have been born into the world with a nature tainted and full of wickedness. Even as every object lifted up from the earth, if unsupported, will fall to the ground, so we, without God’s grace, naturally fall into sin.”

“Then can no one go to heaven?” said Mark.

“Blessed be God, mercy has found a means by which even sinners can be saved! Sin is the burden which weighs us to the dust, which prevents us from rising to glory. The Lord Jesus came from heaven that He might free us from sin, take our burden from us, and bear it Himself; and so we have hope of salvation through Him.”

“I wish that I understood this better,” said Mark.

“I will tell you what happened to a friend of my own, which may help you to understand our position towards God, and the reason of the hope that is in us. I went some years ago with a wealthy nobleman to visit a prison at some distance. Many improvements have been made in prisons since then, at that time they were indeed most fearful abodes. In one damp dark cell, small and confined, where light scarcely struggled in through the narrow grating to show the horrors of the place, where the moisture trickled down the green[47] stained walls, and the air felt heavy and unwholesome; in this miserable den we found an unhappy prisoner, who had been confined there for many weary years. He had been placed there for a debt which he was unable to pay, and he had no prospect of ever getting free. Can you see in this man’s case no likeness to your own? Look on sin as a debt, a heavy debt, that you owe: do you not feel that you have no power to pay it?”

“None,” replied Mark gloomily; “none.”

“I had the will to help the poor man,” continued Mr. Ewart, “but Providence had not afforded me the means. I had no more ability to set him free from prison than I have to rid you of the burden of your sin.”

“But the wealthy nobleman,” suggested Mark.

“He had both power and will. He paid the debt at once, and the prisoner was released. Never shall I forget the poor man’s cry of delight, as the heavy iron-studded door was thrown open for his passage, and he bounded into the bright sunshine again!”

“And what became of him afterwards?” asked the boy.

“He entered the service of his generous benefactor, and became the most faithful, the most attached of servants. He remained in that place till he died; he seemed to think that he could never do enough for him who had restored him to freedom.”

“Where is the friend to pay my debt?” sighed Mark.

“It has been paid already,” said the clergyman.

“Paid! Oh, when, and by whom?”

“It was paid when the Saviour died upon the cross—it was paid by the eternal Son of God. He entered for us the prison of this world, He paid our debt with His own precious blood, He opened the gates of eternal life; through His merits, for His sake, we are pardoned and saved, if we have faith, true faith in that Saviour!”

“This is wonderful,” said Mark, thoughtfully, as though he could yet scarcely grasp the idea. “And this faith must produce a holy life; but here is the place where I went wrong—I thought men were saved because they were holy.”

“They are holy because they are saved! Here was indeed your mistake, my friend. The poor debtor was not set free because he had served his benefactor, but he served him because he was set free! A tree does not live because it has fruit, however abundant that fruit may be; but it produces fruit because it has life, and good actions are the fruit of our faith!”

“But are we safe whether we be holy or not?”

“Without holiness no man shall see the Lord. Every tree that beareth not good fruit is hewn down and cast into the fire.”

“But I feel as if I could not be holy,” cried Mark. “I tried this day to walk straight on in the narrow[49] path of obedience to God—I tried, but I miserably failed. I gained nothing at all by trying.”

“You gained the knowledge of your own weakness, my boy; you will trust less to your resolutions in future, and so God will bring good out of evil. And now let me ask you one question, Mark Dowley. When you determined to set out on your Christian pilgrimage, did you pray for the help and guidance of God’s Spirit?”

Mark, in a low voice, answered, “No!”

“And can you wonder then that you failed? could you have expected to succeed? As well might you look for ripe fruit where the sun never shines, or for green grass to spring where the dew never falls, or for sails to be filled and the vessel move on when there is not a breath of air. Sun, dew, and wind are given by God alone, and so is the Holy Spirit, without which it is impossible to please Him.”

“And how can I have the Spirit?” said Mark.

“Ask for it, never doubting but that it shall be sent, for this is the promise of the Lord: Ask and ye shall receive, seek and ye shall find, knock and it shall be opened unto you. If ye, being evil, know how to give good gifts unto your children, how much more shall your Father which is in heaven give the Holy Spirit to them that ask him?”

“And what will the Spirit do for me?”

“Strengthen you, increase your courage and your[50] faith, make your heart pure and holy. The fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, long-suffering, gentleness, goodness, faith, meekness, temperance. Having these you are rich indeed, and may press on your way rejoicing to the kingdom of your Father in heaven.”

“But how shall I pray?” exclaimed Mark. “I am afraid to address the Most High God, poor miserable sinner that I am.”

“When the blessed Saviour dwelt upon earth, multitudes flocked around him. The poor diseased leper fell at his feet, he was not despised because he was unclean; parents brought their children to the Lord, they were not sent away because they were feeble; the thief asked for mercy on the cross, he was not rejected because he was a sinner. The same gentle Saviour who listened to them is ready to listen to you; the same merciful Lord who granted their prayers is ready to give an answer to yours. Pour out your whole heart, as you would to a friend; tell Him your wants, your weakness, your woe, and you never will seek Him in vain!”

There was silence for a few minutes, during which Mark remained buried in deep, earnest thought. The clergyman silently lifted up his heart to heaven for a blessing upon the words that had been spoken; then, rising from his seat, he said, “I do not give up all hope, Mark Dowley, of procuring a situation for you yet; though, of course, after what has occurred, I shall find[51] it more difficult to do so. And one word before we part. You are now standing before the gate of mercy, a helpless, burdened, but not hopeless sinner. There is One ready, One willing to open to you, if you knock by sincere humble prayer. Go, then, without delay, seek ye the Lord while he may be found, call ye upon him while he is near.”

Mark watched the receding figure of the clergyman with a heart too full to express thanks. As soon as Mr. Ewart was out of sight, once more the boy threw himself down on the grass, but no longer in a spirit of despair. Trying to realize the truth, that he was indeed in the presence of the Saviour of whom he had heard—that the same eye which regarded the penitent thief with compassion was now regarding him from heaven—he prayed, with the energy of one whose all is at stake, for pardon, for grace, for the Spirit of God! He rose with a feeling of comfort and relief, though the burden on his heart was not yet removed. He believed that the Lord was gracious and long-suffering, that Jesus came into the world to save sinners; he had knocked at the strait gate, which gives entrance into life, and mercy had opened it unto him!

“Upon that place stood a Cross, and a little below, in the bottom, a Sepulchre. So I saw in my dream, that just as Christian came up with the Cross, his burden loosed from off his shoulders, and fell from off his back.”—Pilgrim’s Progress.

“Well, this has been a pretty end to your fine pilgrimage!” cried Jack, as Mark, resolved to tell the truth, whatever it might cost him, finished the account of his rupture with the farmer.

“The end!” said Mark; “my pilgrimage is scarcely begun.”

“It’s a sort of backward travelling, I should say,” laughed Jack. “You begin with quarrelling and stealing; I wonder what you’ll come to at last?”

Mark was naturally of a quick and ardent spirit, only too ready to avenge insult, whether with his tongue or his hand. But at this moment his pride was subdued, he felt less inclined for angry retort; the young pilgrim was more on his guard; his first fall had taught him to walk carefully. Without replying, therefore, to the[53] taunt of Jack, or continuing the subject at all, he turned to Ann Dowley, and asked her if she could lend him a needle and thread.

“What do you want with them?” asked Ann.

“Why, I am afraid that I shall be but a poor hand at the work, but I thought that I might manage to patch up one or two of these great holes, and make my dress look a little more respectable.”

“And why do you wish to look respectable?” asked Madge, glancing at him through the uncombed, unwashed locks that hung loosely over her brow; “we get more when we look ragged.”

“To-morrow is Sunday,” Mark briefly replied, “and I am going to church.”

“To church!” exclaimed every other voice in the cottage, in a tone of as much surprise as if he had said that he was going to prison. Except Ann, in better days, not one of the party had ever crossed the threshold of a church.

“Well, if ever!” exclaimed Jack; “why on earth do you go there?”

“I go because I think it right to do so, and because I think that it will help me on my way.”

“And what will you do when you get there?” laughed Ben.

“I shall listen, learn, and pray.”

Ann, who, by dint of searching in a most disorderly[54] box, filled with a variety of odds and ends, had drawn forth first thread and then needle, stretched out her hand towards Mark. “Give me your jacket, I will mend it,” said she.

“Oh, thank you, how kind!” he cried, pulling it off, pleased with an offer as unexpected as it was unusual.

“I think,” said Madge, “that the shirt wants mending worse than the jacket; under that hole on the shoulder I can see the red mark quite plainly.”

“Be silent, and don’t talk nonsense!” cried Ann, impatiently.

The children glanced at each other, and were silent.

“Are you going to the near church by the wood?” said Ann.

“No,” replied Mark; “I have two reasons for going to Marshdale, though it is six or seven miles off. I would rather not go where—where I am known; and judging from the direction in which his carriage was driven, I think that I should have a better chance at Marshdale of hearing Mr. Ewart.”

“Hearing whom?” exclaimed Ann, almost dropping her work, whilst the blood rushed up to her face.

“Mr. Ewart, the clergyman who has been so kind, the tutor to Lord Fontonore.”

“Lord Fontonore! does he live here?” cried Ann, almost trembling with excitement as she spoke.

“I do not know exactly where he lives. I should[55] think it some way off, as the carriage was put up at the inn. Did you ever see the clergyman, mother?”

“He used to visit at my last place,” replied Ann, looking distressed.

“I think I’ve heard father talk about Lord Fontonore,” said Madge.

“No, you never did,” cried Ann, abruptly.

“But I’m sure of it,” muttered Madge in a sullen tone.

“If you know the clergyman, that’s good luck for us,” said Ben. “I daresay that he’ll give us money if we get up a good story about you; only he’s precious sharp at finding one out. He wanted to pay us a visit.”

“Don’t bring him here; for any sake don’t bring him here!” exclaimed Ann, looking quite alarmed. “You don’t know the mischief, the ruin you would bring. I never wish to set eyes upon that man.”

“I can imagine her feelings of pain,” thought Mark, “by my own to-day, when I first saw the clergyman. There is something in the very look of a good man which seems like a reproach to us when we are so different.”

The next morning, as Mark was dressing for church, he happily noticed, before he put on his jacket, the word Pilgrim chalked in large letters upon the back.

“This is a piece of Jack’s mischief,” he said to himself. “I am glad that it is something that can easily be set right—more glad still that I saw it in time. I will[56] take no notice of this piece of ill-nature. I must learn to bear and forbear.”

Mark endured in silence the taunts and jests of the children on his setting out on his long walk to church. He felt irritated and annoyed, but he had prayed for patience; and the consciousness that he was at least trying to do what was right seemed to give him a greater command over his temper. He was heartily glad, however, when he got out of hearing of mocking words and bursts of laughter, and soon had a sense even of pleasure as he walked over the sunny green fields.

At length Marshdale church came in view. An ancient building it was, with a low, ivy-covered tower, and a small arched porch before the entrance. It stood in a churchyard, which was embosomed in trees, and a large yew-tree, that had stood for many an age, threw its shadow over the lowly graves beneath.

A stream of people was slowly wending along the narrow gravel walk, while the bell rang a summons to prayer. There was the aged widow, leaning on her crutch, bending her feeble steps, perhaps for the last time, to the place where she had worshipped from a child; there the hardy peasant, in his clean smock-frock, leading his rosy-cheeked boy; and there walked the lady, leaning on her husband’s arm, with a flock of little ones before her.

Mark stood beneath the yew-tree, half afraid to venture[57] further, watching the people as they went in. There were some others standing there also, perhaps waiting because a little early for the service, perhaps only idling near that door which they did not mean to enter. They were making observations on some one approaching.

“What a fine boy he looks! You might know him for a lord! Does he stay long in the neighbourhood?”

“Only for a few weeks longer, I believe; he has a prodigious estate somewhere, I hear, and generally lives there with his uncle.”

AT THE CHURCH.

As the speaker concluded, young Lord Fontonore passed before them, and his bright eye caught sight of[58] Mark Dowley. Leaving the path which led to the door, he was instantly at the side of the poor boy.

“You are coming into church, I hope?” said he earnestly; then continued, without stopping for a reply, “Mr. Ewart is to preach; you must not stay outside.” Mark bowed his head, and followed into the church.

How heavenly to the weary-hearted boy sounded the music of the hymn, the many voices blended together in praise to the Saviour. God made him think of the harmony of heaven! Rude voices, unkind looks, quarrelling, falsehood, fierce temptations—all seemed to him shut out from that place, and a feeling of peace stole over his spirit, like a calm after a storm. He sat in a retired corner of the church, unnoticed and unobserved: it was as though the weary pilgrim had paused on the hot, dusty highway of life, to bathe his bruised feet in some cooling stream, and refresh himself by the wayside.

Presently Mr. Ewart ascended the pulpit with the Word of God in his hand. Mark fixed his earnest eyes upon the face of the preacher, and never removed them during the whole of the sermon. His was deep, solemn attention, such as befits a child of earth when listening to a message from Heaven.

The subject of the Christian minister’s address was the sin of God’s people in the wilderness, and the means by which mercy saved the guilty and dying. He described the scene so vividly that Mark could almost fancy that[59] he saw Israel’s hosts encamping in the desert around the tabernacle, over which hung a pillar of cloud, denoting the Lord’s presence with his people. God had freed them from bondage, had saved them from their foes, had guided them, fed them, blessed them above all nations, and yet they rebelled and murmured against Him. Again and again they had broken His law, insulted His servant, and doubted His love; and at last the long-merited punishment came. Fiery serpents were sent into the camp, serpents whose bite was death, and the miserable sinners lay groaning and dying beneath the reptiles’ venomous fangs.

“And are such serpents not amongst us still?” said the preacher; “is not sin the viper that clings to the soul, and brings it to misery and death! What ruins the drunkard’s character and name, brings poverty and shame to his door? The fiery serpent of sin! What brings destruction on the murderer and the thief? The fiery serpent of sin! What fixes its poison even in the young child, what has wounded every soul that is born into the world? The fiery serpent of sin!”

Then the minister proceeded to tell how, at God’s command, Moses raised on high a serpent made of brass, and whoever had faith to look on that serpent, recovered from his wound, and was healed. He described the trembling mothers of Israel lifting their children on high to look on the type of salvation; and the dying fixing[60] upon it their dim, failing eyes, and finding life returning as they gazed!

“And has no such remedy been found for man, sinking under the punishment of sin? Thanks to redeeming love, that remedy has been found; for as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so hath the Son of Man been lifted up, that whoso believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life! Behold the Saviour uplifted on the cross, His brow crowned with thorns, blood flowing from His side, and the wounds in His pierced hands and feet! Why did He endure the torment and the shame, rude blows from the hands that His own power had formed—fierce taunts from the lips to which He had given breath. It was that He might redeem us from sin and from death—it was that the blessed Jesus might have power to say, Look unto Me and be ye saved, all ends of the earth.

“We were sentenced to misery, sentenced to death; the justice of God had pronounced the fearful words—The soul that sinneth it shall die! One came forward who knew no sin, to bear the punishment due unto sin; our sentence is blotted out by His blood; the sword of justice has been sheathed in His breast; and now there is no condemnation to them that are in Christ Jesus; their ransom is paid, their transgressions are forgiven for the sake of Him who loved and gave Himself for them. Oh, come to the Saviour, ye weary and heavy laden—come[61] to the Saviour, ye burdened with sin, dread no longer the wrath of an offended God; look to Him and be ye saved, all ye ends of the earth!”

Mark had entered that church thoughtful and anxious, he left it with a heart overflowing with joy. It was as though sudden light had flashed upon darkness; he felt as the cripple must have felt when given sudden strength, he sprang from the dust, and went walking, and leaping, and praising God. “No condemnation!” he kept repeating to himself, “no condemnation to the penitent sinner! All washed away—all sin blotted out for ever by the blood of the crucified Lord! Oh, now can I understand that blessed verse in Isaiah, ‘Though your sins be as scarlet, they shall be white as snow; though they be red like crimson, they shall be as wool.’ ‘Praise the Lord, O my soul! and all that is within me, praise His holy name!’”

That hour was rich in blessings to the young pilgrim, and as he walked towards home, with a light step and lighter heart, it was his delight to count them over. He rejoiced in the free forgiveness of sins, which now for the first time he fully realized. He rejoiced that he might now appear before God, not clothed in the rags of his own imperfect works, but the spotless righteousness of his Redeemer. He rejoiced that the Lord had sealed him for His own, and given him sweet assurance of His pardon and His love. Oh, who can rejoice as the Christian rejoices when he looks to the cross and is healed!

“I saw then in my dream that he went on thus, even until he came to the bottom, where he saw, a little out of the way, three men fast asleep, with fetters upon their heels.”—Pilgrim’s Progress.

The poor despised boy returned hungry and tired to a home where he was certain to meet with unkindness, where he knew that he would scarcely find the necessaries of life, and yet he returned with feelings that a monarch might have envied. The love of God was so shed abroad in his heart, that the sunshine seemed brighter, the earth looked more lovely; he felt certain that his Lord would provide for him here, that every sorrow was leading to joy. He thought of the happiness of the man once possessed, when he sat clothed and in his right mind at the feet of the Saviour: it was there that the pilgrim was resting now, it was there that he had laid his burden down. The fruit of the Spirit is peace and joy, such joy as is the foretaste of heaven.

And the love of God must lead to love towards man. Mark could feel kindly towards all his fellow-creatures[63] His fervent desire was to do them some good, and let them share the happiness that he experienced. He thought of the rude inmates of his home, but without an emotion of anger; in that first hour of joy for pardoned sin there seemed no room in his heart for anything but love and compassion for those who were still in their blindness.

As Mark drew near to his cottage, he came to a piece of ground overgrown with thistles, which belonged to Farmer Joyce. He was surprised to find there Jack, Madge, and Ben pulling up the thistles most busily, with an energy which they seldom showed in anything but begging.

“Come and work with us,” said Ben; “this ground must be all cleared to-day.”

“And why to-day?” said Mark.

“Because Farmer Joyce told us this morning that when it was cleared he would give us half-a-crown.”

“You can work to-morrow.”

“Ah, but to-morrow is the fair-day, and that is why we are so anxious for the money.”

“I will gladly rise early to help you to-morrow, but this day, Ben, we ought not to work. The Lord has commanded us to keep the Sabbath holy, and we never shall be losers by obeying Him.”

“Here’s the pilgrim come to preach,” cried Madge in a mocking tone.

“I tell you what,” said Jack, stopping a moment in his work, “you’d better mind your own business and be off; I don’t know what you have to do with us.”

“What I have to do with you!” exclaimed Mark. “Am I not your brother, the son of your mother? Am I not ready and willing to help you, and to rise early if I am ever so much tired?”

There was such a bright, kindly look on the pale, weary face, that even Jack could not possibly be offended.

“Now, just listen for a moment,” continued Mark; “suppose that as I was coming along I had spied under the bushes there a lion asleep that I knew would soon wake, and prowl in search of his prey, should I do right in going home and taking care of myself, barring our door so that no lion could come in, and never telling you of the danger at all?”

Madge glanced half-frightened towards the bushes, but Jack replied, “I should say that you were a cowardly fellow if you did.”

“What! leave us to be torn in pieces, and never give us warning of the lion?” cried Ben.

“I should be a cowardly fellow indeed, and a most unfeeling brother. And shall I not tell you of your danger, when the Evil One, who is as a roaring lion, is laying wait for your precious souls. As long as you are in sin you are in danger. Oh, that you would turn to God and be safe!”

“God will not punish poor children like us,” said Madge, “just for working a little when we are so poor.”

“The Evil One whispers the very same thing to us as he did to Eve, ‘Thou shalt not surely die;’ but she found, as we shall find, that though God is merciful, He is also just, and keeps His word.”

“There will be time enough to trouble ourselves about these things,” said Ben.

“Take care of yourself, and leave us in peace!” exclaimed Jack; “we are not going to be taught by you!” and turning his back upon Mark, he began to work more vigorously than ever.

Mark walked up to the cottage with a slow, weary step, silently praying for those who would not listen to him. “God can touch their hearts though I cannot,” thought he. “He who had mercy on me may have mercy on them.”

Never had the cottage looked more untidy or uncomfortable, or Ann’s face worn an expression more gloomy and ill-tempered.

“Mother,” cried Mark cheerfully, “have you something to give me, my long walk has made me so hungry?”

“We’ve had dinner long ago.”

“But have you nothing left for me?”

“You should have been here in proper time. It’s all gone.”

Exhausted in body, and wounded by unkindness,[66] Mark needed indeed the cordial of religion to prevent his spirit from sinking. But he thought of his Lord, and his sufferings upon earth. “My Saviour knew what it was to be weary and a-hungered—He knew what it was to be despised and rejected. If He drained the cup of sorrow, shall I refuse to taste it! If this trial were not good for me, it would not be sent.” So Mark sat down patiently in a corner of the room, and thought over the sermon to cheer him.

His attention was soon attracted by Ann’s giving two or three heavy sighs, as if she were in pain; and looking up, he saw a frown of suffering on her face, as she bent down and touched her ankle with her hand.

“Have you hurt yourself, dear mother?” said he.

“Yes; I think that I sprained my ankle this morning. Dear me, how it has swelled!”

“I am so sorry!” cried Mark, instantly rising. “You should put up your foot, and not tire it by moving about. There,” said he, sitting down at her feet, “rest it on my knee, and I will rub it gently. Is it not more easy now?”

Ann only replied by a sigh, but she let him go on, and patiently he sat there, chafing her ankle with his thin, weary fingers. He could scarcely prevent himself from falling asleep.

“That is very comfortable,” said the woman at last; “certainly it’s more than any of the others would do for their mother; they never so much as asked me how I did.[67] You’re worth all the three, Mark,” she added bitterly, “and little cause have you to show kindness to me. Just go to that cupboard—it hurts me to move—you’ll find there some bread and cheese left.”

MARK’S KINDNESS.

Mark joyfully obeyed, and never was a feast more delicious than that humble meal. Never was a grace pronounced more from the depths of a grateful heart than that uttered by the poor peasant boy.

“Now, about the midway to the top of the hill was a pleasant arbour made by the Lord of the hill for the refreshment of weary travellers.”—Pilgrim’s Progress.

Several days passed with but few events to mark them. Mark did everything for Ann to save her from exertion, and under his care her ankle became better. He also endeavoured to keep the cottage more tidy, and clear the little garden from weeds, remembering that “cleanliness is next to godliness,” and that if any man will not work, neither should he eat.

One morning Madge burst into the cottage where Mark and Ann were sitting together. “He is coming!” she exclaimed in a breathless voice; “he is coming—he is just at the gate!”

“Who?” cried Ann and Mark at once.

“The parson—the—”

“Not Mr. Ewart!” exclaimed Ann, starting up in terror.

“Yes it is—the tall man dressed in black.”

In a moment the woman rushed to the back room as fast as her ankle would let her. “I’ll keep quiet here,” she said. “If he asks for me, say that I have just gone to the miller’s.”

“Mother’s precious afraid of a parson,” said Madge, as a low knock was heard at the door.

With pleasure Mark opened to his benefactor.

“Good morning,” said Mr. Ewart, as he crossed the threshold. “I have not forgotten my promise to you, my friend. I hope that I have obtained a place for you as errand-boy to a grocer. Being myself only a temporary resident in these parts, I do not know much of your future master, except that he appears to keep a respectable shop, and is very regular in attendance at church; but I hear that he bears a high character. Mr. Lowe, if you suit him, agrees to give you board and lodging; and if he finds you upon trial useful and active, he will add a little salary at the end of the year.”

“I am very thankful to you, sir,” said Mark, his eyes expressing much more than his lips could. “I trust that you never will have cause to be sorry for your kindness.”

“Is your mother within?” said Mr. Ewart.

Mark bit his lip, and knew not what to reply, divided between fear of much displeasing his parent, and that of telling a falsehood to his benefactor.

“She’s gone to the miller’s,” said Madge boldly.

But the clergyman turned away from the wicked little girl, whose word he never thought of trusting, and repeated his question to Mark, whose hesitation he could not avoid seeing.

“She is within, sir,” said the boy, after a little pause; then continued with a painful effort, as he could not but feel that Ann’s conduct appeared rude and ungrateful to one whom above all men he was anxious to please; “but she would rather not see you to-day.”

“Very well, I have seen you; you will tell her what I have arranged.” Mark ventured to glance at the speaker, and saw, with a feeling of relief, that Mr. Ewart’s face did not look at all angry.

It was more than could be said for Ann’s, as, after the clergyman’s departure, she came out of her hiding-place again. Her face was flushed, her manner excited; and, in a fit of ungovernable passion, she twice struck the unresisting boy.

“Lord Jesus, this I suffer for thee!” thought Mark; and this reflection took the bitterness from the trial. He was only thankful that he had been enabled to keep to the truth, and not swerve from the narrow path.

On the following day Mark went to his new master, who lived in a neighbouring town. He found out the shop of Mr. Lowe without difficulty; and there was something of comfort and respectability in the appearance[71] of the establishment that was very encouraging to the boy. To his unaccustomed eye the ranges of shining brown canisters, each neatly labelled with its contents; the white sugar-loaves, with prices ticketed in the window; the large cards, with advertisements of sauces and soap, and the Malaga raisins, spread temptingly to view, spake of endless plenty and abundance.

Mark carried a note which Mr. Ewart had given to him, and, entering the shop, placed it modestly on the counter before Mr. Lowe.

The grocer was rather an elderly man, with a bald head, and mild expression of face. He opened the note slowly, then looked at Mark over his spectacles, read the contents, then took another survey of the boy. Mark’s heart beat fast, he was so anxious not to be rejected.

“So,” said Mr. Lowe, in a slow, soft voice, as if he measured every word that he spoke, “so you are the lad that is to come here upon trial, recommended by the Reverend Mr. Ewart. He says that you’ve not been well brought up; that’s bad, very bad—but that he hopes that your own principles are good. Mr. Ewart is a pious man, a very zealous minister, and I am glad to aid him in works of charity like this. If you’re pious, all’s right, there’s nothing like that; I will have none about me but those who are decidedly pious!”

Mr. Lowe looked as though he expected a reply, which[72] puzzled Mark exceedingly, as he had no idea of turning piety to worldly advantage, or professing religion to help him to a place. He stood uneasily twisting his cap in his hand, and was much relieved when, a customer coming in, Lowe handed him over to his shopman.

Radley, the assistant, was a neat-looking little man, very precise and formal in his manner, at least in the presence of his master. There was certainly an occasional twinkle in his eye, which made Mark, who was very observant, suspect that he was rather fonder of fun than might beseem the shopman of the solemn Mr. Lowe; but his manner, in general, was a sort of copy of his master’s, and he borrowed his language and phrases.

And now, fairly received into the service of the grocer, Mark seemed to have entered upon a life of comparative comfort. Mr. Lowe was neither tyrannical nor harsh, nor was Radley disposed to bully the errand-boy. Mark’s obliging manner, great intelligence, and readiness to work, made him rather a favourite with both, and the common comforts of life which he now enjoyed appeared as luxuries to him.

“I have been climbing a steep hill of difficulty,” thought he, “and now I have reached a place of rest. How good is the Lord, to provide for me thus, with those who are his servants!”

That those with whom Mark lived were indeed God’s servants, he at first never thought of doubting. Was[73] there not a missionary-box placed upon the counter—was not Mr. Lowe ever speaking of religion—was he not foremost in every good work of charity—did he not most constantly attend church?

But there were several things which soon made the boy waver a little in his opinion. He could not help observing that his employer took care to lose no grain of praise for anything that he did. Instead of his left hand not knowing the good deeds of his right, it was no fault of his if all the world did not know them. Then, his manner a little varied with the character of his customers. With clergymen, or with those whom he considered religious, his voice became still softer, his manner more meek. Mark could not help suspecting that he was not quite sincere. The boy reproached himself, however, for daring to judge another, and that one so much more advanced in the Christian life than himself. He thought that it must be his own inexperience in religion that made him doubt its reality in Lowe.