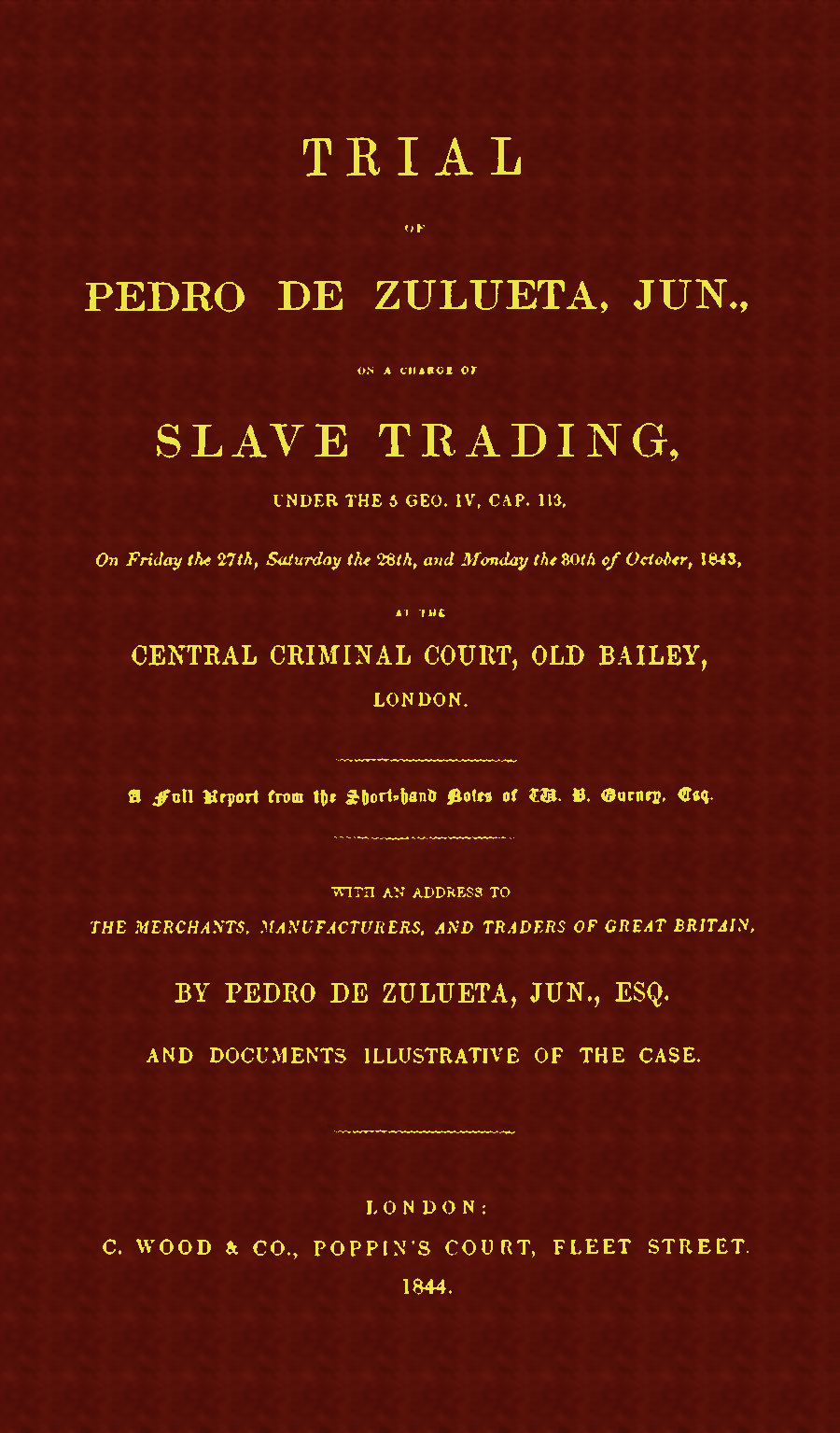

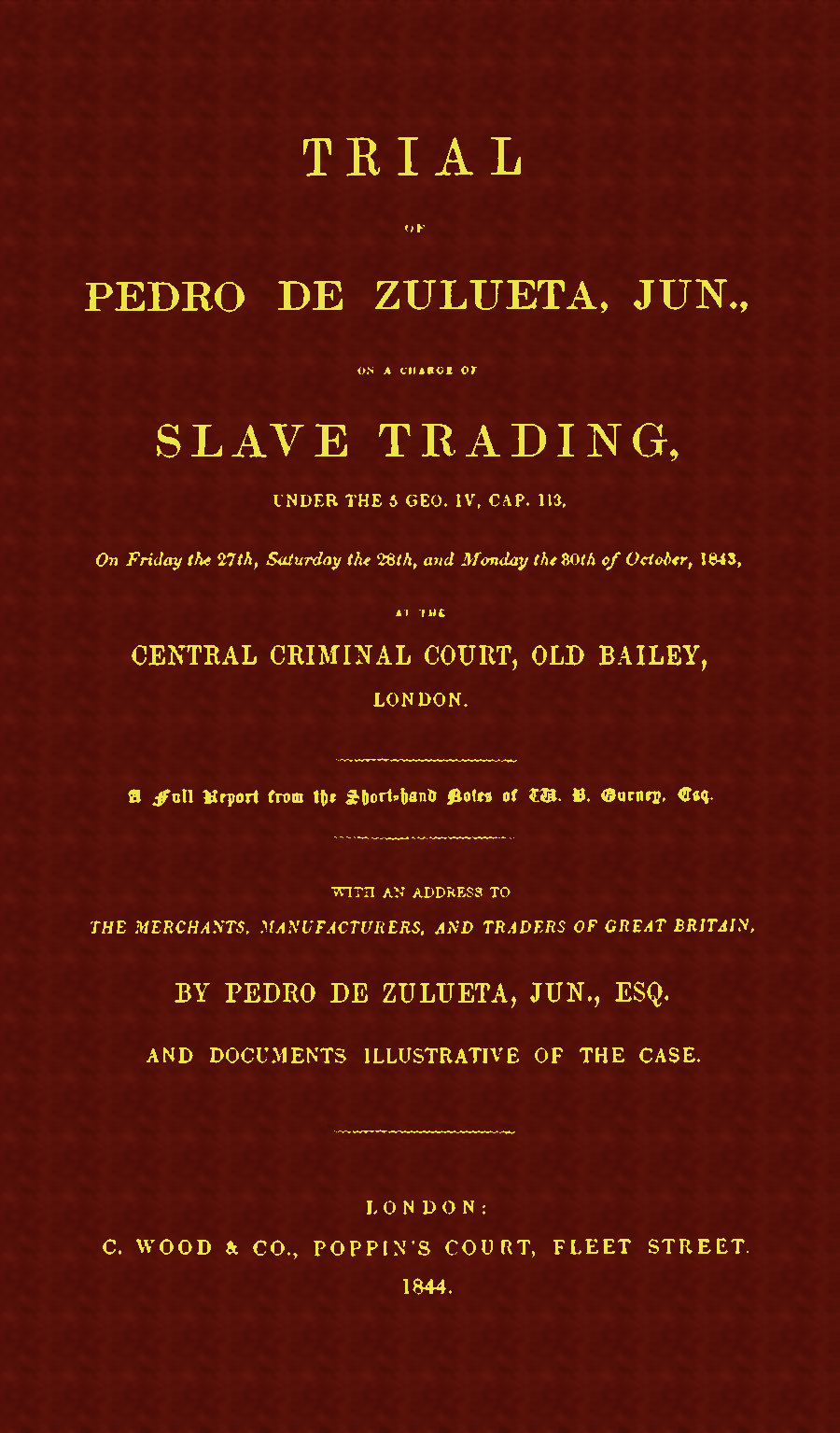

Title: Trial of Pedro de Zulueta, jun., on a Charge of Slave Trading, under 5 Geo. IV, cap. 113, on Friday the 27th, Saturday the 28th, and Monday the 30th of October, 1843, at the Central Criminal Court, Old Bailey, London

Author: Pedro de Zulueta

William Brodie Gurney

Release date: September 30, 2020 [eBook #63348]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by hekula03, Harry Lamé and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Please see the Transcriber’s Notes at the end of this text.

The cover image has been created for this text, and is in the public domain.

TRIAL

OF PEDRO DE ZULUETA, JUN.,

ON A CHARGE OF

SLAVE TRADING.

A Full Report from the Short-hand Notes of W. B. Gurney, Esq.

WITH AN ADDRESS TO

THE MERCHANTS, MANUFACTURERS, AND TRADERS OF GREAT BRITAIN,

BY PEDRO DE ZULUETA, JUN., ESQ.

AND DOCUMENTS ILLUSTRATIVE OF THE CASE.

LONDON:

C. WOOD & CO., POPPIN’S COURT, FLEET STREET.

1844.

LONDON

C. WOOD & CO., PRINTERS, POPPIN’S COURT, FLEET STREET.

[v]

| Page | ||

|---|---|---|

| Address to the Merchants, Manufacturers, and Traders of Great Britain | ix | |

| Opinions of Legal Authorities | lxxiii | |

| Documents illustrative of the case:— | ||

| Letter from R. R. Gibbons, Esq. to Messrs. Zulueta & Co., and Summary of Dr. Madden’s Report | 1 | |

| Copy of a Letter from Messrs. Zulueta & Co. to Lord Viscount Sandon | 5 | |

| Evidence of H. W. Macaulay, Esq. before the Select Committee on West Coast of Africa, forwarded to Messrs. Zulueta by order of the Chairman | 7 | |

| Evidence of Captain Henry Worsley Hill, R.N., ibid | 80 | |

| Additional Evidence of Captain H. W. Hill, ibid | 102 | |

| Evidence of Captain the Honourable Joseph Denman, R.N., taken before the Select Committee on West Coast of Africa | 107 | |

| Evidence of Pedro de Zulueta, Jun., Esq., taken before the Select Committee on West Coast of Africa | 167 | |

| Report from the Select Committee on the West Coast of Africa | 187 | |

| Proceedings instituted against Pedro de Zulueta, Jun., Esq.—Arrest Aug. 23, 1843 | 209 | |

| Application to take Bail (from the Anti-Slavery Reporter) | 210 | |

| Indictment for Felony | 211 | |

| Indictment for Conspiracy | 214 | |

| [vi]Proceedings in the Central Criminal Court, August 24, 1843 (from the Anti-Slavery Reporter) | 219 | |

| Affidavit of Defendant and Mr. Edward Lawford in support of Application for Writ of Certiorari | 219 | |

| Motion to postpone the Trial of the Indictment | 222 | |

| Trial of Pedro de Zulueta, Jun., Esq. | ||

| First day, Central Criminal Court, | Friday, Oct. 27, 1843 | 235 |

| Second day, | Saturday, Oct. 28 | 316 |

| Third day, | Monday, Oct. 30 | 391 |

[vii]

TO

THE MERCHANTS,

MANUFACTURERS,

AND

TRADERS OF GREAT BRITAIN.

The case, which will be laid before you in the following pages, must be admitted to be one of an unprecedented character.

A merchant, to all practical purposes a British merchant, the junior member of a firm of unquestioned respectability, in which his father and brother are active partners with himself, which has been established for upwards of seventy years in Spain, and of twenty in the City of London, during which period they have maintained, both as merchants and as individuals in private life, the character which will be found in the following pages to have been given them upon oath by several of the most eminent of their fellow-merchants—this individual finds himself suddenly arrested, in the manner hereafter described, within the precincts of his own private office, which is situated in the most conspicuous spot in the City of London, whilst in the pursuit of his ordinary business, upon a bench-warrant, as it is said (but which was never shown to, or has been since seen by him), a true bill having been found against him by the Grand Jury of the County of Middlesex. The charge will be found in the two indictments inserted in pages 211 and 214, the former for felony, under the Act of 5 Geo. IV, cap. 113, entitled “An Act to[x] amend and consolidate the Laws relating to the Abolition of the Slave Trade;” the latter for conspiracy, to do that which the former indictment describes as done, viz. “manning,” &c. &c., “and shipping certain goods on board a certain vessel, called the Augusta, for the purpose of dealing in slaves;” and the penalty, amounting, in fact, to a person in the rank and station of the accused and of his family, to a forfeiture of life, and those objects which are dearer than life itself. He is carried in custody to the police-station on Garlick Hill, where shortly afterwards, a London attorney, whose name he had never before heard, appears and prefers a charge of slave dealing. The prisoner is immediately conveyed to the Central Criminal Court, then sitting at the Old Bailey; there the two indictments are read to him pro formâ, for they leave him in utter ignorance of who the prosecutor is, or upon what depositions the Grand Jury had found the bill, although his defence, to be effectual, must be directed against them: they remain to this moment an undisclosed mystery, and no one is answerable for the accuracy of those statements, whilst who the prosecutor was, was only disclosed by the counsel for the prosecution at the trial, before the examination of the witnesses began.

The prisoner’s application to the Central Criminal Court to be admitted to bail was strenuously opposed by the prosecuting attorney in person, when the Court, yielding to the representation of the probable result of the refusal upon the members of an honourable family thus violently taken by surprise and distracted, granted the application on terms indeed which the Court itself deemed excessive, but which were the only terms to which the attorney’s consent could be obtained. It was found impossible, on account of the lateness of the hour, to meet with one of the two individuals who had been approved of by the attorney; and under these circumstances the Court consented to receive one security alone for 2,000l., and the prisoner’s own[xi] recognizance for 6,000l. Thus it happened, that he who had left his home, his wife, and his children in the morning, with as assured a conscience as any of you can do, returned about ten o’clock in the evening a prisoner, with the possibility of a sentence of transportation hanging over his head, as ignorant of his accuser, or of the facts deposed to against him, as if he had fallen into the hands of the Inquisition.

The whole transaction, embracing the purchase and dispatch of the vessel Augusta, named in the indictment, had formed part of the subject of an examination, for which the house of Zulueta & Co. tendered themselves in the person of Pedro de Zulueta, before a Select Committee appointed in March, 1842, by the House of Commons, to inquire into the State of the British Possessions on the West Coast of Africa, and which was sitting in July and August, 1842, and the Report of whose proceedings had then been nearly a year before the public. Before that Committee, among several other witnesses, two officers of the navy (whose names may be seen on the back of the indictments), who had been in command of British cruizers on the African coast, and another individual, who it seems has discharged the duties of a Judge at Sierra Leone, appeared and were examined. Their examinations were published in the Report, and from thence are inserted in the following pages; but it should be observed that the last-mentioned of these three individuals did not appear in the prosecution, his evidence being inserted here only from the anxiety that a complete case should be placed before you.

As it is in the power of every reader to verify the correctness of any observations that may be made upon the merits of the evidence given by these individuals before the Committee, it cannot be improper to call attention to the temper which evidently pervades it, not for the purpose of invective, but because it is a circumstance of very great practical application to the matter in[xii] hand. It is impossible not to be struck upon its perusal with the absolute recklessness of statement, both as to fact and theory. The most formidable conclusions are built upon the most slender foundations. Facts and theories are so mixed up together, that it is only after much sifting that it turns out that what was stated as fact was no more than a theory in the speaker’s mind; and these theories, too, embracing all questions, whether of commerce, of fiscal science, policy, legislation, international law, education, morals, and religion: after which, the character of individuals, or that of a commercial house, is no doubt a matter about which much circumspection cannot be expected to be exercised. The fate of Africa, the immense interests of British commerce, of the commerce of the world; the interpretation of existing laws, under which property, life, honour, may be forfeited; their modification and adjustment; public opinion with its powerful influence, so dangerous when misled, so difficult to be set right; all these awfully important matters seem to hang upon the lips of those two officers of the navy—and they do not seem to feel any hesitation in disposing of such momentous interests. Can it be expected that they would stop and consider before they make a statement regarding private individuals, even though they may happen to be, to say the least of it, accounted by the first men of this city, and in others of the first cities of the world, honourable by birth, profession, and personal character? The crime of which they would be guilty, were mere assertion to be taken as positive proof, is according to the witnesses so heinous, that it exceeds in their estimation almost every other, not only in the law of man, but in the law of God; and yet it is to be imputed upon their construction of some rumours which they themselves, it is quite possible, indeed very probable, may quite unconsciously have helped to mould into a shape by their readiness to accumulate this miscalled evidence. Whether this representation of the[xiii] general character of the evidence given before the Committee by these individuals is, or is not, correct, may be seen at once by a reference to it in the following pages.

The first information, which any of the members of the house of Zulueta & Co. had of even the existence of the Committee, was the receipt of a letter (see p. 1) accompanying a copy of a lengthy Report, by a Dr. Madden, on the Coast of Africa, which called forth a reply (see p. 5) addressed by Zulueta & Co. to the Chairman of the Committee—a reply, which, in truth, contains the whole of their case, and to which they may well look back with just pride, since the keenest appetite for the discovery of guilt has not been able to detect one single circumstance contradictory of one tittle of its contents. Neither the examination before the Committee in 1842, nor the trial in 1843, circumstances which could not be foreseen or anticipated, have elicited one single fact at variance with the statements of that letter, impossible as it was to have contemplated at the time it was written, that its accuracy would be subject to so severe a test as either the examination before the Committee, which took place two months afterwards, or the trial, which did not occur till after the lapse of more than a year.

After that letter was sent, it became known to the house of Zulueta & Co. that further statements, unfavourable to their character as merchants, had been made before the Committee; and in consequence of a verbal representation of the unfairness of such mode of accusation, copies of the examinations of two of the witnesses were sent to them. The individual who now addresses you, then offered himself, at the request of his partners, to be examined, the selection of himself being made for no other reason than that he was thought more capable of making himself understood.

It was thus therefore that I, Pedro de Zulueta the younger, appeared before the Committee, and, as will be seen by the minutes of my evidence, entered into an examination[xiv] of every statement which was brought before me as having been made by the witnesses concerning my house, contradicted several of them, explained others, and volunteered a description of the nature of the dealings of my firm with the two others (whose names had been flung at us) from the time of the establishment of Zulueta & Co. in London, twenty years ago. I also underwent a cross-examination, of which one very remarkable feature was, that Captain Denman himself, one of the witnesses against me both at this examination and at the trial, was sitting close to several members of the Committee, and was seen by me to whisper repeatedly into the ear of more than one member, what, it is not unnatural to suppose, may have been directions for the more effectual discovery of the truth.

I can hardly restrain the expression of my feelings when I consider now the use which has been made of the unreserved frankness, the unguarded, because unsuspecting, candour of the statements made by me before that Committee. The thought never occurred to me, that evidence, professedly taken for the benefit of the public service, required any thing more than substantive truth, and a general bearing upon the points in question; nor could I ever have conceived that it would be scanned with critical severity, in order to take advantage to my detriment of the worst construction that might be put upon this or that verbal slip, so as to place my very existence at stake upon it. I considered myself as doing nothing more than (whilst attempting to eradicate from the minds of the Committee any unfavourable impression, which might have been made upon them by incorrect statements against the character of my house) affording information for placing the legislation on the subjects before the consideration of the Committee on a more satisfactory basis—not by indulging in assertion of crude theories, or in vague declamations, but by the simple statement of a practical case—anxious to show in the instance of my house[xv] the situation in which a firm of acknowledged honour and respectability, whose private character, and the prominent political position of one of its members in another country, renders them at least very unlikely abettors of the slave trade—may yet be placed, because, living in England, they happen to have a mercantile intercourse with persons residing in places where this trade is unhappily one of the existing evils, and in which therefore those persons may be more or less implicated, inasmuch as it is well known that no trade whatever can be carried on with a country where the slave trade exists without its being, in some measure, of more or less direct assistance to this illicit traffic. And as the assertion which had been made against some of our correspondents tended, if true, to place this position of merchants in England in a very striking light, I did think that whilst the statements made might be true (and to disprove them could not be in my power nor in the power of any man in my situation) the proper and fair course was not to controvert the matter at all; but, taking the statements for granted, practically to direct the attention of the Committee to the position in which British merchants are left upon the very case itself, which was made out by the bitterest impugners of the character of British commerce.

I appeal to every man who reads my evidence before the Committee—without a previous determination to find out some one upon whom an experiment of the power of the Act of 5 Geo. IV may be tried, and a corroboration of the theory respecting the alleged existence of British slave trading—whether upon any other hypothesis, but that of conscious innocence or of consummate effrontery, my answers to the questions put by the Committee can be possibly reconciled with common sense or common prudence, much less be consistent with that deep skilfulness and far-seeing intelligence, which have been so lavishly attributed to me and to my partners for the purposes of my destruction.

[xvi]

Not for an instant, even when those outraged feelings, which have not been spared, possessed greatest sway over my mind, has the thought occurred to me, that at the time of my examination the object of any one member of the Committee, or even of Captain Denman himself (for I have alluded to the fact of his being present), could be the collecting materials for a secret accusation before a Grand Jury; and I wish very distinctly to protest against any such inference being drawn from my remarks, not for the sake of the members of the Committee, who are above being injured by insinuations, but for my own sake, who alone could be injured by the supposition. I am conscious of having appeared before several men whose names are, and have been ever since I can recollect having heard them, associated in my mind with nothing but what is honourable and high principled: I received from some of them complimentary expressions upon the apparent candour and openness, the straightforward character of the evidence given; and I cannot help believing that my statements were considered moreover valuable, as tending to show the inexpediency, the gross injustice, of encouraging on the one hand trade with countries in which slave trade prevails, and yet, on the other hand, attempting to make the natural and well-known tendency of all trade to mix itself with the general state of society of the country into which it is carried, the evidence of some peculiar criminal knowledge in the parties necessarily nearest in contact with those countries, and visiting that knowledge upon them, after the community have derived profit and advantage from the transaction, although it is well known that the parties so to be sacrificed have it not in their power to guard any but themselves from being directly instrumental to the deviation of the trade into channels rendered illegal by Act of Parliament. I venture to assert, that the prominent feature of my evidence was felt by the Committee to be its unconnectedness with any party[xvii] or theory; and this feature stamped it with the character of truth which, if fairly and honestly stated, must at times militate against one theory or another.

This is an offence to all who thrive upon theories, and in exactly the proportion of their affected or unreasonable belief of them. An instinctive alarm takes possession of such minds, and as they themselves cannot conceive that other people may have no theory of their own to serve upon that particular subject, which to them, and therefore in their opinion to all, must be paramount, they are disposed to imagine one theory of their own, which they at once fix upon the party thus offending against the assumed mental necessity of universal theorism. If the writer is not much mistaken, the irritation which is produced by this process of the mind, still more if self-interest is at the bottom, will materially help to reveal the moving-spring of the proceedings which are recorded in the following pages.

Be this as it may, one thing is altogether unquestionable (and indeed there has been no attempt to disguise the fact, and to it I beg to call the attention of every man in Great Britain)—it is this: Pedro de Zulueta could never have been placed in the position in which he was (charged with felony under the finding of the Grand Jury), with the remotest chance of a conviction, if he had not voluntarily offered himself for examination before a Committee of the British House of Commons—the way being this—a London attorney lays hold of the printed Report of the proceedings; every part of the evidence given by Pedro de Zulueta, that was destructive of the hypothesis of his being a well-knowing and wilful abettor of an alleged slave trading speculation in 1840, is disconnected from those passages in which he had stated that, in 1842, when he was speaking (after hearing and reading a mass of evidence given for the first time before that Committee), he had heard statements about his correspondents being participators in the slave[xviii] trade which might be true, which were not, he felt, material to himself, and which, as he had not the means of disproving, he then stated that he must then believe; and then using this intelligible admission, made in 1842, the only one that could be found at all available, as the only presumptive proof of guilty knowledge in 1840. Nothing could be done or attempted against the house of Zulueta & Co., much less against the individual who was attacked, without this management, this distortion of the evidence—for some knowledge of some kind must be made out in 1840, and although the fallacy was transparent, it might and unfortunately did serve for the purpose of the attack at the heart, and might still serve for the next, but not the sole object, of the prosecution. It is true, that the whole of the evidence given by me was read at the trial, for so the law requires it; but that same law, as was observed, also permits that those parts of a man’s statements which make in his favour should not be believed or taken for any thing, whilst such admissions as might be made to appear criminatory of himself are received as evidence against him. By such a process of distortion alone could a case be made out against my house, or fixed upon myself, who was totally unknown to the so-called witnesses as they themselves admitted, and who did not personally appear in any part of the transactions excepting at my own examination before the Committee. If the facts are not so, let it be at once explained what other circumstance marked me out for prosecution. Let the reader of the following pages, after perusing the trial carefully, attempt to solve the problem for himself of how (apart from the fact of my appearing, and of the application which is made of my statements before the Committee of the House of Commons) the firm of Zulueta & Co. came to be prosecuted in my person to the exclusion of others. Let every other part of the evidence given before and at the trial, of matter of fact, by the witnesses on the transaction of the Augusta be considered,[xix] and where is one single fact that can connect Zulueta & Co. with the alleged, and only alleged, designs of the parties by whose orders they had acted in that transaction—an acting in itself admitted to be innocent? And if the reader does not find any other solution of the difficulty, it is clearly demonstrated that Pedro de Zulueta has been prosecuted upon partial statements from his own evidence, given before a Committee of the House of Commons, where he appeared voluntarily, where he was encouraged to explain transactions of business, and neither refused nor even hesitated to answer one single question that was put to him, as conducive to a great public object; but without the slightest intimation of the ulterior object to which it has been perverted.

For the purpose not certainly of clearing up the question, but of sophisticating a very plain case, it will perhaps be asked, whether, if a man should avow himself before a Committee of the House of Commons to have been guilty of a crime, or to have partaken in it, is it meant to be contended that his candour is to be the safeguard of his guilt? One short answer is, that the remark is inapplicable to the case; for no such avowal has been even contended to have been made, but on the contrary a distinct and repeated general and circumstantial disavowal was made. Whether my declarations did or did not amount to such degree of information in my mind, at the time of giving my evidence, as presumed a knowledge two years before, that would be brought under the description of the guilty knowledge described in legal phraseology, in an Act of Parliament, very obscure as is generally admitted, and never before put in practice, this was the utmost that the ingenuity of the prosecution could make out of my evidence—and this cannot be called an avowal of crime. The question is not, whether a crime avowed before a Committee of the House of Commons should or should not be prosecuted,[xx] using the avowal as one of the means of conviction—a question, which even so put is argued, I believe, on both sides by eminent lawyers—but whether in my case, such as it is, I have not a right to complain of the grossest and most unparalleled breach of good faith—whether the use made of my evidence is not one against which the conscience of every man revolts—whether it is likely to facilitate the public service, or to increase the respect due to the British Legislature at home and abroad, or to their proceedings—even if in other respects the course adopted is free from legal objections, which I believe is at least doubtful.

The fact itself is unquestionable, and I must repeatedly assert it—that the materials for my prosecution were collected from my own evidence as laid before the public, in the printed Report of the Committee, for whose information it was given—that in collecting these materials the statements, although formally read as they were made, were virtually vitiated—that, although the whole was read, only that part which was thought susceptible of some adverse construction was avowed to be of any necessary weight; and statements, such as they were, which had been made in 1842, after information that was at any rate only furnished in that year, were applied for the purpose of raising a presumption of guilty knowledge in 1840.

I have insisted so much upon this point, because it is very material that it should be borne in mind throughout the perusal of the following pages. I do not hesitate to believe that the unsophisticated sense of the people of this country will revolt at the fact of a Committee of the House of Commons having been turned into a trap wherein to take a man—a snare to his good faith—the more effectual, because the members who happen to compose the Committee stand high for honour and integrity in the land, and therefore their very names seemed to afford a guarantee that the fairest construction would be put upon the words of a respectable[xxi] individual, who appeared voluntarily before them, without assuming from the outset that he is a self-convicted felon, who comes before them for no other purpose than to deceive, and who must be listened to only in order to see if he does not betray himself into some acknowledgment of his crimes, of which advantage is to be taken to secure the ends of justice, which he craftily endeavours to defeat. It may suit those who want such a monster of craft and subtlety in order to justify the monstrous proceedings, which have been deemed necessary to support a mischievous and unfounded theory that British capital is employed in the slave trade—it may suit them, to make me out to be this desideratum in their system; but, without laying claim to any more extended or more favourable notoriety than that which is on record, I venture to say that the attempt must fall to the ground, by the weight of its intrinsic absurdity, before the common sense of the people of this country.

But what the Committee thought of the evidence, after hearing at length the very individuals who appeared against me at the Old Bailey, and after hearing my own evidence, which formed the chief weapon against me in that Court, will be found in their own Report, printed in the following pages. Every reader may judge for himself, whether, in point of fact, it is not an anticipated condemnation of such proceedings as have been inflicted upon me—a verdict of not guilty, not only upon the transactions of the Augusta, but upon the whole of Zulueta & Co.’s agency for the houses mentioned, in my evidence, if the representation given by me of the transaction be substantially correct. In page 203 the following words will be found:—“In the first place, it is fair to state that we have no evidence, or reason to believe, that any British merchant, concerned in the trade with the West Coast of Africa, either owns or equips any vessel engaged in the slave trade, or has any share in the risk or profits of any slave trade venture”—a declaration this, the correctness[xxii] of which every one conversant with the characteristic features of British commerce must acknowledge. Have any facts been elicited subsequent to this Report, and previously to the prosecution being instituted—any new evidence, which was not before the Committee of the House of Commons? This is a question which happily every reader of the following pages may settle for himself. Let him, as he peruses the evidence, at each stage of it ask himself the question—Was this before the Committee of the House of Commons? That it was, must be the answer upon every point. Not one statement was elicited from a single witness which had not been before the Committee. There was indeed an unworthy attempt to create a false impression about some casks and shackles having been left on board, even after the most unsparing of the witnesses for the prosecution had acquitted the vessel of even the shadow of a suspicion of containing the least implement available for a slaving equipment. How the attempt was foiled by their own witness afterwards will be seen; and I will not say a word more about an attempt upon which the very existence of a fellow-creature perhaps might hang, leaving it to be visited with the feeling of abhorrence which it must excite in every reader. Apart from this, there was before the Committee much more against me than there was before the Court, as may be seen by a comparison of the evidence as given before the one with that given before the other; because the nature of legal proceedings keeps the witness, even if otherwise disposed, within the limits of matter of fact—limits, which before the Court they did attempt to transgress, as may be seen very prominently in the case of the chief of them, but from which before the Committee it was in their power to wander, and they did accordingly so wander at every moment. Is it not fair to infer, that it was not to serve the purposes of justice, but at the very best that of some fancied expediency, that this prosecution was undertaken—a prosecution demonstrated to have been[xxiii] undertaken against the recorded sense and opinion of the Select Committee of the House of Commons? Suppose, for a moment, that by some quibble of law, by the forced interpretation of an Act of Parliament, admitted to be sufficiently obscure—not to speak of attempts to pervert evidence, or of the effort to carry off the victory, which constitutes the very essence of all legal conflict between individuals, and which of itself renders the right of private prosecution of public wrongs the destruction of civil liberty and of individual security—suppose, that by such means, what to the deliberate judgment of the Committee of the House of Commons did not appear to deserve even animadversion, might have been made out before an Old Bailey Jury to be such evidence of guilt, as to have procured an adverse verdict—is this the kind of justice which the people of this country would have approved? Impossible! I cannot believe it: the idea cannot be for a moment entertained.

But this is not all. We have seen what the Committee of the House of Commons decided. The Government—the proper, and the only proper agents, in a prosecution of this kind, upon whom, if sufficient ground existed, it was a bounden duty to have taken it in hand—seem to have treated the matter in the same manner as the Committee. All the documents which have been received in evidence, and some which were offered and were not received by the Court—that, in short, which forms all the evidence against the accused at the trial, and more, were in possession of Government before the last Administration went out (the proceedings before the Committee alone excepted)—that Administration did not take up the prosecution. The law-officers of the present Administration have had them also, and moreover the proceedings before the Committee, one of the members of which was a leading member of the preceding Government—they have not taken up the prosecution. A print in the favour and confidence,[xxiv] as it seems, of the parties to the late proceedings, has stated, that the actual law-officers of the Government were consulted and decided against their being undertaken; that again, when the bill was found by the Grand Jury, the prosecution was offered to them, but that they declined to be parties to it. These statements are followed up by remarks upon the apathy and indifference of the Government, which can only serve to render the testimony borne to the fact the more unexceptionable, because unwilling; for, otherwise, they afford only a lamentable specimen of how much mischief is done to a cause, the sole merit of which must consist in its being one purely of humanity, by its being used for the purposes of political warfare. This indeed is to trade with the cause of the slave.

The fact remains unshaken, that neither the Attorney-General of the present nor of the late Administration has prosecuted by himself or by others, and therefore the Queen’s name was as much usurped under the cover of the forms of the Court, as that of the public, whose name is invoked in support of these proceedings. I will venture to say, that no one who has really looked into them for himself, and is possessed of all the facts from the examination before the Committee of the House of Commons, can think with other feelings than those of shame and indignation, that they can take place in England—feelings, the more strong, because such proceedings are pretended to be undertaken in order to serve a cause with which, if they are identified, they will only serve to disgrace it. I cannot but believe that all this is felt by the majority (I know it is felt by very many) of the members of a society, whose zeal may be imposed upon at times, but the majority of whom must have that real benevolence of heart and soundness of judgment, which will make them wish for no other principle of action than that contained in the well-expressed sentiments of a noble lord—“That a good, however eminent, should not be[xxv] attained otherwise than by lawful means[1]:” it may be added, that by no other can it be permanently attained.

[1] Lord Aberdeen’s Letter to the Lords of the Admiralty, 20th May, 1842.

The Society, to which I am alluding, was not more eager to start or to adopt the prosecution than the Committee of the House of Commons disposed to find a ground for its being undertaken, or than the last and the present Administration; indeed, the Society volunteered a disavowal of any connexion with the proceedings at their commencement, and did not express even an approval of them. In this, their organ only represented faintly the sentiments more strongly and decidedly repeated to myself by many members of that Society in a tone of unequivocal reprobation, and viewing the proceedings as calculated only to injure the cause which they had at heart. That such has been a very generally prevailing impression is fully attested by the plaintive remarks of the organs of the prosecution, and the libellous stimulants which, whilst the proceedings for the trial were in progress, they thought it necessary to apply. It is, indeed, but too true that a society, proposing to itself the accomplishment of some great moral and benevolent object, is most specially bound to confine itself to the use of such means only as are of as unexceptionable and even as benevolent a character as the end. Crime is, indeed, a just object of abhorrence; but a society, like the Anti-Slavery Society, is specially bound to guard themselves against the danger of encouraging one species of crime in their attempt to put down another; every one of the means they employ or sanction must be of as unquestionable purity as the end they profess to aim at: expediency, as distinct from justice, must be jealously guarded against, apt as it is to insinuate itself into all human proceedings, and never more subtilely than under the cloak of zeal in a good, cause: the smallest degree of evil to be[xxvi] done must stand as an insurmountable barrier to the accomplishment of the most undoubted good. It is in the power of man to destroy the very end in view, whilst he thinks he is advancing it; but he cannot alter the law of Providence, which dooms to certain defeat, even amidst the tokens of apparent triumph, whomsoever dares to modify for himself the moral code of the universe: the moment that violent hands are laid upon it, in order to smooth down a difficulty in the way of action, the very end itself becomes contaminated. All this is evident enough, and approves itself to the enlightened conscience. A society, as a body, taken in the abstract, may be supposed less likely to be led away by such apparently short cuts when presenting themselves in their path; but these societies are, in practice, managed by individuals of whom the least scrupulous are sure to appear as the most zealous and most efficient—they are the most busy and the most forward—and, hence, the additional necessity for caution on the part of the more conscientious, inasmuch as the names of the good are too often the cover of the deeds of the bad, whose power consists exclusively in the moral weight attached to the acts which the good are made to appear as having sanctioned.

It would have been well for the credit of the Anti-Slavery Society, therefore, if the London Committee had retained the position in which they placed themselves by their own act of disavowal; instead of which, after being taunted by one or two prints, which have, pending the proceedings, used every exertion in their limited power to stimulate the passions of those whose good sense it was necessary to mislead, the London Committee have passed and published the following resolution:—

“At a meeting of the Committee of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, held at No. 27, New Broad Street, London, on Friday, December 8, 1843, Josiah Forster in the Chair,—The conduct of Sir George Stephen, in[xxvii] the prosecution of Pedro de Zulueta, Jun., in October last, being taken into consideration, the following resolution was unanimously adopted—

“That this Committee feel it to be due alike to Sir George Stephen himself, and the public interests of justice and humanity, to express their high sense of his philanthropic and public spirited conduct, in carrying on, upon his own responsibility, the prosecution of Pedro de Zulueta, Jun., and another, for slave trading; a course in which the decision of the Grand Jury, and the declared opinion of the Judge, have fully sustained him, and by which it may be hoped a salutary check will be given to the notorious implication of British capital and commerce in that nefarious traffic. Josiah Forster, Chairman.”

Here, after using that description of the charge, which is calculated to convey a false notion of what was, and could alone, even by the worst construction and perversion, be imputed, as if the charge had been dealing in slaves, they express a high sense of the philanthropic and public spirited conduct of the prosecutor—necessarily including the inquisitorial proceeding before the Grand Jury—the mode of apprehension of the accused—the resistance to his being released on even large bail, and to his having time given him to prepare his defence—the shrinking from appearing as a witness in public, and stating there what he, the prosecutor, had been ready to swear before the Grand Jury—the bringing up of a witness to raise an appearance of the existence of facts, the very contrary of which had been deposed to before the Committee of the House of Commons by the leading witness for the prosecution in Court—all this forms that conduct, which must have been taken into the consideration of a committee of a benevolent society, and which in discharge of a duty of both justice and humanity that committee have pronounced as both philanthropic and public spirited.

[xxviii]

The resolution proceeds to state, that in the course adopted by the prosecutor he has been fully supported by the decision of the Grand Jury and the declared opinion of the Judge. It is impossible to estimate what value to attach to the finding of a Grand Jury without knowing upon what evidence their finding was based. In the present case, one fact is beyond all dispute, viz. that Sir George Stephen appeared before the Grand Jury as the first witness, his name standing as such on the back of the indictment, and that he did not present himself in the witness-box at the public trial, although in Court from the beginning to the close of it—from which it results, that the Grand Jury had before them a witness, giving to them in private, evidence which he did not think proper to give in public. Must not the inference be permitted, that the Grand Jury would have thrown out the bill, as the Petty Jury threw out the indictment, unless some evidence, which was not offered to the latter, had been given to the former by a witness, and that too, unfortunately, by a witness who seems to have preferred the secret inquisitorial form, which still remains in British law, to the open and public path which was before him, and which is the proper boast of British justice?

Regarding the support derived from the expressions of Judge Maule, when applied to by Serjeant Bompas for an order for the payment of the expenses of the prosecution, it is not for me to speak; but that it does not extend to a sanction, in point of propriety, to the part taken by the prosecutor, nor to the manner in which he has discharged it, is very obvious.

This, however, is not the point to which I wish now to refer. The object of this publication, and of the preceding and following remarks, is not any vindication of myself, nor a crimination of the motives of any one beyond what the statement of facts may carry in itself; my vindication I consider ample in the exhibition of the facts themselves—in[xxix] the verdict of the Jurors, after hearing a trial of two days duration, after a long and elaborate charge delivered when a clear day had elapsed subsequent to the defence—a verdict, which was not agreed to without consideration, which was pronounced by the foreman in the emphatic manner which the crowded Court witnessed, which was received by the spectators, consisting of some of the most respectable merchants, bankers, and professional men of the City of London, who had sat daily and patient witnesses of the proceedings, in a manner which has been noticed by the public press, and echoed by the leading journals of London, of Liverpool, and of other important mercantile cities of Europe.

The chief object proposed in this publication, and in these observations, is to place before my brother-merchants, in a connected form, the whole of the facts, which form my case, or rather the case of the firm of Zulueta & Co., from the first communication which preceded my examination before the Committee of the House of Commons, to the close of the proceedings at the Old Bailey, in order that the merchants of England may judge for themselves, and reflect upon the position in which they are placed, as resulting from the principle and doctrines which the proceedings contained in the following pages have disclosed to emanate from an Act of Parliament which has been passed these twenty years, but which has been for the first time tried upon my case. It may be said, that by merchants in general it is hardly known: we all know that dealing in slaves is prohibited, under severe penalties, by the law of England—we know that it is repugnant to the prevailing tone of education, to the opinions and feelings of our people—we know that, at all events, as it is carried on and can only be carried on, it is at variance with the spirit of Christianity, and therefore no man need read an Act of Parliament to abstain from having any, the slightest, concern in or with such a traffic; but even if these considerations were not enough—which England surely will not[xxx] suffer to be supposed of her own merchants—even if these considerations did not go to the extent of precluding British merchants from laying out their capital on slave adventures, whether for themselves or others’ account, common prudence, in which respectable merchants in this country cannot be said to be deficient, does at once warn a man not to trust his funds to the issue of speculations which afford no security, over which he can exercise no control—so much so, that it is hardly possible to conceive in what shape, looking at all like business, British capital could be lent for the purpose or on the security of a slave trade adventure. All this has contributed to maintain merchants in utter ignorance of the provisions of this Act of Parliament, or of the use which might be made of its legal phraseology: but now, when a merchant, not at all suspected by his fellows—for that is on record—has been, to the astonishment of every one, dragged from his office to the police-station, and to the Old Bailey dock (more especially when this is done in spite of the resolution of the House of Commons’ Committee, in spite of the opinion of the law officers of the Crown) by a London attorney, it is time to look at the exposition of the law and the practical application of its provisions, which so extraordinary a proceeding has elicited; the more so, as it has been stated that “higher game is in view,” and that the prosecutor is still occupied in analysing the evidence given before the Committee; and when the Anti-Slavery Committee adopt and publish a resolution, in which it is stated, in reference to the late prosecution, that by it “it may be hoped a salutary check will be given to the notorious implication of British capital and commerce in that nefarious traffic, the slave trade.” At any other time the absolute folly of the assertion would have suffered it to remain unnoticed; experience has shown, however, that there is somewhere the means, and that the will does exist, of doing mischief to an appalling degree.

[xxxi]

As explaining the practical operation of the law, then, I shall look upon the summing up of the learned Judge, not with a critical eye, in order to decide whether the law has been well or ill administered—this is the province of a professional man, into which it would be preposterous for me to enter. Upon the propriety or impropriety of the Judge’s acts and opinions, or even of his exposition of the law and its requirements, I must be understood as maintaining a complete reserve. For the present purpose, and for every practical purpose that can affect others, the law must be taken as laid down by his Lordship. As to its meaning, the evidence which is required under the Act to bring an individual to trial, the degree of evidence which will send a case to the Jury, that upon which a case in answer shall be demanded of the accused—until it is otherwise declared by competent authority—until then, those who really wish to obey the law must look upon the late administration of it as that which is to be expected, and the extent and applicability of the Act of Parliament to be that which is exhibited in the late proceedings.

The first consideration which presents itself is the nature and definition of the offence. In the outset of his summing up, the learned Judge stating the nature of the charge, alluding to the vessel which the prisoner is alleged to have employed, lays down, “that it was not necessary to be proved that the ship in question (the Augusta) was intended to be used for the conveyance of slaves from the coast of Africa. If there was a slave adventure—if there was an adventure, of which the object was that slaves should be brought from the coast of Africa, that there should be slave trading there—and if this vessel was dispatched and employed for the purpose of accomplishing that object, although it was intended to accomplish that object otherwise than by bringing home the slaves in that vessel—that is within the Act of Parliament. So, if the goods were loaded for the[xxxii] purpose of accomplishing the slave trade ... the crime charged in this indictment would be committed, the allegations in the indictment would be supported, and the prohibition of the Act of Parliament would be violated.”

Such is the nature of the offence. If there is a slave adventure in the port of destination of the vessel and goods which you dispatch, for the purpose of accomplishing which they may be said to have been intended, the prohibition is violated; but as, in the case of the vessel and the goods in question, no attempt was even made to prove the existence of any such adventure, but only a general slaving character of the port of destination, it follows that not even the existence of such particular slave adventure is necessary to be proved in order to support an indictment under the Act, but it is enough if a general slaving character of the trade at the port of destination is proved, in order to lay the ground of an indictment. Let this general slave trading character be discovered by any one of a port in Africa, to which you may have sent goods—and of course, if a port not in Africa is (as may very well be) largely concerned in the trade, the case is not very much altered—and you stand open to a charge under the Act, for the crime has been committed. It is as when a man is found murdered in the street—the crime has been committed—the only thing is to find out the criminal. How this is done under the Act of Parliament on the slave trade is the next thing to be seen.

“The employment, the dispatch of the vessel,” says the learned Judge, “is no conclusive proof of the guilt, till going further, and showing that the party doing so did it for the illegal purpose charged.” But then, for the purpose of beginning the inquiry, without which there would have been no beginning of it, the foundation must be laid in the employment of the vessel by the person accused. If slave trading is intended, and the vessel be sent for the purpose, the important consideration then is, whether the person[xxxiii] employing the vessel is cognizant of the intention. We have seen the large meaning of the terms slave trading. It is not like wine trade—dealing in wine: it is not dealing in slaves, but dealing in Manchester and Birmingham goods, adapted and purposely manufactured for the African markets, so long as it is found that slave traders, that is, as heretofore the term has been understood, dealers in slaves—resort to the port for which they are shipped. Of course the crime having been committed by some one, that is, by the person who intended that slave traders should use them for slave purposes—and no other will be supposed as possible—the existence of the law punishing such an intention demands that an inquiry should be made. For this purpose the commission-agent in England, who employed the vessel, must be laid hold of—not that in that one act there is a conclusive proof of guilt, until it be further shown that he was cognizant of and intended the illegal object, but because an inquiry is imperative under the Act. With whom the right and duty of making it rests it matters not—any one that may be so disposed from a philanthropic and public-spirited motive. It is not enough that a Parliamentary inquiry has been made already—it is not enough that the law-officers of the Crown see no reason to institute a further inquiry—it matters not, if the case has been lying in all its details before the public, the ends of public justice are never satisfied until the so-called inquiry takes the shape of a bill before the Grand Jury—the inquisition of the country. There certain depositions are secretly made upon oath, which you shall never see; and upon this mild and fair procedure you will have your very life, and the life of every one dear to you placed in jeopardy, for I believe that there is nothing in the mercantile profession which is likely to prepare a man, and a man’s family, for his being treated as a felon. It is indeed true, that in the evidence before the Committee of[xxxiv] the House of Commons merchants are treated by some of the witnesses in a tone and manner becoming only those times in which merchants were tolerated for the sake of the money that might be extorted from them, but otherwise were considered as a caste whose instinct was money-making by all means, right or wrong, and against whom every crime might be presumed; but, whatever may be in the heart of some, and whatever may rise to their lips, against a profession which England honours and distinguishes, a distinct avowal dare not be made such as will justify the insinuation that there is absolutely nothing in carrying a merchant, considered respectable, from his private office to a felon’s den, without his knowing his accuser, or upon what he is charged, which ought to shake his mind or that of his family.

But, then, unless you are proved to have been cognizant of the intended purpose, you will be acquitted. The nature of the offence has been explained and laid down to embrace a very wide compass. If there existed a slave adventure at the port of destination of a vessel, to accomplish which that vessel carried goods, the offence has been committed. The penalty, to whomsoever committed it, is by the Act only short of the greatest imposed by the law. You employed the vessel—this is not conclusive of guilt, until it is shown further that there was slave trading intended, and that you were cognizant of the intention. Let us see how both things are to be proved and brought home to you. Heretofore the way between your office and the Old Bailey is one which there is no merchant, trading with countries wherein the slave trade is allowed to exist, may not be dragged through without risk or responsibility by any ruffian in London. Now, perhaps, though not exactly at the earliest stage that may be desirable for the safety of the innocent and the repose of honourable families—still now, perhaps, the requirements[xxxv] of the law in regard to proof are commensurate with the facility afforded on the outset, and with the terrible penalty which follows a conviction.

The Judge proceeds upon this part of the evidence as follows: “It appears from the evidence, that the Gallinas is a place described by some witnesses of great experience—two captains in the navy, and Colonel Nichol, who was the governor of a district in the neighbourhood” (about 1,500 miles from it, see his evidence), “whose employment was mainly to watch the slave coast, of which the Gallinas forms a part, and to contribute to the putting down the slave trade—that the Gallinas is a place of slave trading, and of no other trade at all.” His Lordship continues as follows: “It is said, and I think with great probability, that the Gallinas is not generally known as a slave trading place, in fact, it seems very little known at all; it seems to be a place where any other description of felons may resort to concert their schemes and hide their stolen goods, and which, of course, they do not make public, and which is not likely to be known by honest and true people. Except those employed as police or otherwise in aid of justice, as these captains were, of course it would not be spoken of at all. There might be slave traders in London knowing it very well, but they would be perfectly silent probably, and hardly mention it by name even in speaking one to another. It is very probable, therefore, that the place was not very well known; that when these persons spoke of the Gallinas, they might say the Gallinas on the coast of Africa; and a person might be very conversant with the geography of Africa in an honest way, who had not been active in putting down the slave trade, and yet might not know where it was, except that it was on the coast of Africa.”

It is impossible more correctly to state, in stronger language, or more clearly, the possibility of the place of destination[xxxvi] of a vessel being a slave trading place, and that exclusively, without in the least diminishing the great probability of its being unknown to the party in England who ships goods for that place as a commission-agent, by order and for account of somebody else abroad. Thus, the great probability of my statement before the Committee of the House of Commons of the ignorance of the character of the trade carried on at Gallinas was completely vouched for, and the observation, that those who knew were not likely to tell, and not likely to as much as name the place, was forcible in my favour, since the house had entered and cleared the Augusta for Gallinas, and not for Africa, as ships with destinations for the West Coast are generally dispatched, and as the Augusta might most certainly have been, had the house even suspected an improper object which required concealment. It is singular that, in the explanations prepared for instructing counsel, the case is stated in nearly the same terms as to the ignorance of the character of the place, as those used by Judge Maule. Merchants easily understand this, because it is the case more or less with every one. In shipping goods by foreign order and for foreign account to distant ports in all parts of the world, with which there is hardly any communication, and with which the shipper himself has none, and need not have any for the purpose of such a transaction, it most frequently happens, that the nature of the trade carried on at that particular port is very imperfectly or rather not at all known. In the multitude and the rapidity of operations which must be disposed of almost without thinking, the inquiry (not being either interesting or profitable, and of course quite unnecessary) is not made, or indeed as much as thought of, especially when heretofore, I believe, it will be acknowledged that it has not been considered that the nature of the trade carried on at any place could involve the mere shipper, without a connexion[xxxvii] or any interest in that place, in the slightest responsibility.

But what follows? The character of the place is thus settled: “That it is itself a slave trading place appears to be very evident from the case on the part of the prosecution. Probably those honest persons, those honestly dealing persons, who know best about it, are those who have been called upon by their public duty to ascertain it. Such persons have been called, and they give it this character and description, and they state that it is distinguished from other parts of the coast of Africa; for on other parts of that coast, it is said, slaves are sold as one article of export, but that other things, such as palm-oil—I believe that is the principal thing—and ivory, and wood, and other things, are sold in immense quantities on the coast of Africa; but that that is not the case at the Gallinas. They might be carrying out goods to other parts of Africa, intending to bring home palm-oil, or slaves, as might be most profitable; they might intend to bring home an honest commodity, and not have to do with this dishonest and perilous commodity; but it appears difficult to conceive what a person, carrying a cargo of goods to the Gallinas, could intend to do with it, unless he intended to have those goods employed in the slave trade. The prisoner might say they were to be employed by others in the slave trade; that would be plain and simple: it is wrong, but it is a plain and simple account of that which was intended to be done. It is a place, as it appears, without any trade; and if there be an obvious plain interest in a person carrying goods to that place, it appears to me that it may be taken that they were for the purpose of the slave trade. If that be the plain and obvious inference, it appears to me that might be the inference very properly drawn by Colonel Nichol, that this was a slave adventure, unless the contrary were proved.” Here the character of the place seems the[xxxviii] only point upon which the observations of the learned Judge bear; and that character having been laid down as very probably indeed unknown to any one but the dealer in slaves, and the police employed against them, they do not seem to touch the prisoner. But at the same time an answer is suggested which the prisoner might give about what was intended, thus seeming to imply, that he ought to be furnished with evidence in answer, capable of accounting for what was intended, without which the full weight of an inference by one of the witnesses must remain, so far attaching to him the knowledge that he must necessarily be supposed to entertain of what was intended by others. I had said before the Committee, in the evidence read in Court, that the house knew nothing of what was to be done with the goods. Therefore, this not being admitted, it seems to follow that the law, as laid down by Judge Maule, requires some plain and simple account of what was intended to be done with the goods from the commission-agent in England who ships them by order and for account of a merchant residing abroad. It had before been laid down, that to ship the goods for slave trade purposes is an offence under the Act, if the shipper was cognizant of the intent: it is now said, that the port is an exclusively slave trading port, and it is not suggested that this was probably unknown, as it had before been said, to any but the dealer in slaves and the police employed against them, nor any account taken of the statement of the accused before the House of Commons, which had been read in Court, disclaiming the very possibility, as a mere shipping-agent, of any knowledge of what was to be done with the goods: the only answer suggested is one which may give a plain and simple account of what the merchant abroad intended to do with the goods at such a port. It seems to follow, therefore, that the mere shipping-agent in England is bound by the Act to be provided with such an account; and if he does not give it, the inference, to be drawn as to the object of the[xxxix] shipment from the character of the port, will not only attach to the adventure, but will cut deeper, since if you are bound to have and to produce a knowledge, and you do not produce it, it seems that the account is to be held not to be producible.

The notion that the Act of Parliament must be understood, not only as punishing a proved guilty knowledge, but as demanding from the accused party proof of an innocent knowledge of the plans and objects of a foreign merchant residing abroad, in respect of a transaction, in which the former has had no other share than that of a simple shipping agency in England, by order and for account of the latter, pervades the whole of the proceedings, and shows itself more clearly in the remarks that follow. “It is possible,” continues the Judge, “that this might be an adventure, not slave trading; if so, nothing can be more simple than to prove it: Martinez & Co. might prove that it is an honest adventure. If it was a dishonest adventure, it could not be expected that Martinez & Co. should be called to give evidence at all; but if it were an innocent adventure, it would be very easy for them to be called. It is true that persons are to be convicted, not by evidence they did not produce, but by evidence produced against them—not on suspicion, but on conviction; but where such evidence is offered of the trade being slave trading, as is offered here, namely, that the vessel was loaded with goods” (in itself, as the learned Judge had formerly stated, not conclusive of guilt)—“that a cargo of goods was dispatched” (to which the same former observation applies) “to a place, where slave trading is the only known object for which vessels ever go” (known to slave traders and the police employed against them, as was also aptly remarked by his Lordship; although one of these, Captain Denman, seems to have known of 800 tons, according to his evidence (see p. 329); and upwards of 1,000 tons, according to his official dispatch to the Governor[xl] of Sierra Leone, dated 12th December, 1840[2], as having been landed at Gallinas, without being able to say that the object was slave trading)—“a slave-mart and nothing but a slave-mart—you have a case, though it is an answerable case; but if the answer, which if it exist could be easily given, is not given, it may very fairly be inferred that the vessel was proceeding on a slaving voyage, a voyage either for the purpose of bringing home slaves, or of landing those goods for the purchase of slaves.”

[2] Vide “Report. West Coast of Africa. Part II, Appendix,” &c. p. 460.

The learned Judge is still upon the point of the nature of the adventure, as indicated by the nature of the trade said to prevail at Gallinas; and as in the former observations, since the name of Gallinas has been laid down as probably conveying no information to any but slave dealers and the slave police, the prisoner seems to remain untouched. But then it is laid down that an answer, which of course somewhere must exist, could be easily given by the accused. How so? but that the law, this special Act of Parliament, must be so understood as to require the simple shipping-agent in England to prepare himself with a full knowledge of the plans and the objects of the foreign merchant abroad, who orders certain goods to be purchased and shipped for his account. The learned Judge has not lost sight that in the universal practice of law, a conviction is only justifiable by evidence produced—that is, produced against, not by that which the accused party does not produce: but he feels it his duty, under the Act of Parliament he was expounding, to warn the Jury that the case is not so to be treated; for the operation of that Act, when to be applied to a commission-agent in this country, shipping goods to a place about which such evidence is offered as that it is a slave-mart, and a slave-mart only, even although the knowledge of that fact has been previously stated to be most probably[xli] confined to dealers in slaves, and the police employed against them, upon whose testimony alone it stood before the Court—in such a case, when dealing with the 5th Geo. IV, the onus probandi lies with the accused. In the course of mercantile transactions, the commission-agent, who buys and ships goods by order and for account of a foreign merchant residing abroad, and to a port with which the former has no intercourse of trade whatever, would not be supposed nor could be expected to possess any further knowledge than that necessary to complete, in England, his own part of the transaction; but not so for the purposes of the Act in question. The reasoning seems to be this: here is a law which makes a certain knowledge guilty, if the object of the party abroad, originating the transaction be in deed and in fact a guilty one. In order to give force and strength to the operation of this law, it must be so laid down as to render necessary some knowledge of either an innocent or of a guilty nature, in the party residing in England, of the plans and objects of the party abroad by whose order and for whose account he has shipped goods to the port indicated to him. This or that knowledge must exist in the agent: he must be called upon to produce even the very foreign merchant himself, over whom the Court can give the accused no control, over whom he himself is not shown to possess any, and whose testimony after all could not be trusted; since that of the accused, as recorded before the Committee, is not. If in this, or in some other way, he does not prove knowledge of an innocent object, the object must be taken to be a guilty one; and as the law must be understood to require a knowledge, and he shows no innocent knowledge, the inference remains of a guilty knowledge: from which it seems evident that shipping agency business cannot be safely undertaken, as has been heretofore done, at least for merchants residing in countries in which slave dealing still exists, not only in Africa, but Cuba, Brazils, the United States, and other places. But[xlii] merchants in England are required to master the whole object and plan of their correspondents abroad; and that the sincerity of his endeavours will be measured only by the result, is what common prudence will teach a man to expect from the machinery which is set on foot in order to apply to this Act of Parliament that notable remark, that who wills the end wills the means.

And thus, after having laid down that the Act requires a proof of innocence in the party accused, a knowledge of something innocent intended—which, if not given, must leave the inference of guilty knowledge, inasmuch as no knowledge, ignorance of the object, cannot be taken as an answer—the accused, if he cannot produce his correspondent, or if he did not possess himself at the time of making the shipment, of a plain and simple account of his plans, is left to the mercy of such inferences as may be drawn; and upon this view of the requirements of the Act of Parliament he is to be considered as withholding something which cannot be supposed to be favourable to him. This inference will not be counterbalanced—it cannot be when once admitted; it must either be destroyed by the plain and simple account of what the merchant abroad intended, or its edge will be blunted by nothing else. The accused’s character may be “of the very highest,” perfectly unassailable; the position he occupies in the mercantile profession may be very high, the profession itself in this country being reckoned on a level for honour and principle with the highest; and men of unblameable character, of considerable standing and independence, conscientious and upright, moving in society where good taste and right feeling prevail, are not likely to put their property, their character, their consciences, in jeopardy, especially by partaking in transactions to which their habits and feelings, and those of persons around them, stand opposed, and all that for very paltry advantage. It is pointed out by the learned Judge, that although a very[xliii] grave charge, and of a very highly penal nature, still the slave trade—the dealing in slaves—“is a trade, which till a recent period was lawful for persons in this country, and many persons of very good character certainly did engage in that trade, and a great number of persons justified it. I suppose,” he continues, “those same persons would now say it is not to be engaged in, because it is a prohibited thing—it is a regulation of trade enforced by very severe penalties made by this country—but that the dealing in slaves is in itself a lawful, right, good, and proper thing, which ought not to be prohibited. Those persons would now consider slave trading as a thing prohibited only by positive regulations. There is no one who does not at once perceive that practical distinction between them. There is no person who, in point of feeling and opinion, does not perceive the difference there is between a thing which is prohibited by positive law, and that kind of thing, against which, if there were no law at all against it, the plain natural sense and conscience of mankind would revolt. This trading in slaves, in the opinion of a great many persons, is itself an abomination, a thing which ought to be considered with the greatest horror, whether prohibited or not; but those who think it was right when it was not prohibited, probably do not think it so very bad if it be committed now, since it has been prohibited by law, only that it is to be avoided on account of the penalty to which it subjects the individuals engaged in it. This has some bearing on the question of how far considerations of character would have weight with respect to such an offence.” The opinion entertained by the individual in question against the slave trade may be as strong as the strongest for any thing that appears, who has stated without its having been contradicted, that neither himself nor his family have ever been suspected of having the smallest interest in slave dealing, or in slave property, about which he has stated how[xliv] his fathers have proceeded: an individual, who may, perhaps, have a very strong opinion as to the moral and religious duty of obedience to positive enactments by competent authority, and who said something to that effect in the evidence before the Committee of the House of Commons, which had been read in Court.

This as to the character of the party. As to the inducement, when it is alleged that the smallness of the agency commission charged shows that the transaction was considered to be one in the ordinary course of shipping business, that consideration is pressed down by the weight of the radical defect in not having given a plain and simple account of what was intended by the foreign merchant. “It is alleged,” says the Judge, “that the profit on this transaction would be extremely small. I do not think that the petty gain of this one transaction is the matter, for it appears that Pedro Martinez & Co. do a great deal of business, and it is possible that whenever persons have a large and valuable business to conduct, there is some small portion that the correspondent and agent would willingly get rid of if he could; but he is not allowed to pick and choose, but he must take the whole.” In short, a London merchant, of the character which has been described, is to be supposed as not at all unlikely to commit a felony, if the alternative be to lose a valuable connexion.

And thus, whilst the most unimpeachable character is not a proof to any extent against the suspicion of a felonious knowledge and intent, and whilst the token of innocence afforded by the charge of the ordinary rates allowed in legitimate business is not considered of weight—as a compensation in some other way is possible, and the disposition to barter conscience and duty for money is such a thing as people who conduct a large business are not quite unlikely to lend themselves to if they are not allowed to pick—so, likewise, the supposed extent of the connexion of the merchant is[xlv] no bar to their being supposed anxious to retain one more under felonious conditions. Neither the superiority of his knowledge and education, nor his skilfulness, are likely to make him either apprehensive or disinclined to the commission of a crime, whilst these qualities render him obnoxious to the remark, “that it may very generally be taken, that people know what they are about, unless they can show there was some particular concealment, some hinderance to their knowledge;” “unless they,” so accused, “can show,” that they did not know (not if those who accuse them have shown that they did know), then all the qualities of character, station, extent of business, education, are against the accused; and unless the accused can show, that he had a knowledge of something innocent having been intended by the foreign merchant, any peculiar circumstances of the case, which may appear to be of a favourable nature to the accused, must be considered only in that light which may diminish the improbability of his having had a guilty knowledge. Thus, as the employment of the British flag for the purpose of dealing in slaves stares every body in the face, and was a very strong feature in the present case, not only against any knowledge on the part of the charterer of the vessel and shipper of the goods in England, but even against there having been any guilty intent in the merchant abroad, who had the choice of other flags equally secure and less easy of detection and punishment, the favourable inference hence arising must be neutralised. “If Jennings” (the master of the vessel) “was an adventurer, if he were, as suggested, a very clever and intelligent person, and very conversant with every thing to be done on this occasion, a competent master of the vessel, supposing the slave trade to be intended, a thing which requires qualities one is sorry to see exercised so ill—a great deal of courage, sagacity, and presence of mind, and an unscrupulous readiness to employ them for the commission of this felony, not to be found in everybody—a[xlvi] man of such a description would be the paramount object of a slave trader, whose aim would be, whoever the owner may be, to elude all search, so to manage the thing as that the cruizers of any country shall not stop him. Probably, if the adventure succeeds, it must succeed by such means, so that one sees a perfectly good reason why, consistently with this being a slave trading voyage, it may have been English owned.” Not a word appears in the proceedings against the character of this man, neither does it seem intended by the learned Judge to impugn it, simply to say that if the man did possess the qualities of cleverness and courage attributed to him, these qualities being very serviceable for wicked purposes, it is to be inferred that they were intended to be applied to a slave trade adventure, since no plain and simple account of a lawful intent on the part of the foreign merchant has been given by the charterer in England, with whom the law is to be supposed to make a knowledge imperative. The prosecutor knew, although it was not before the Court, that this man had been tried for the very identical offence in this matter of the Augusta at Sierra Leone, and had been acquitted; for the chief witness in this prosecution, in which, be it observed, Jennings is coupled with me (see the indictment, page 211), was the prosecutor in the proceedings against him before the criminal court of that colony; and he himself stated before the Committee of the House of Commons (see Lieutenant Hill’s evidence, page 84), that Jennings had been acquitted. And here, by the way, let it be noticed, that Jennings is at this moment under a prosecution in London for the very crime for which he was tried at Sierra Leone and there acquitted, the chief and really the only witness, upon whose sworn depositions before the Grand Jury here the bill against Jennings has been found, being the very same person who instituted the prosecution at Sierra Leone, which terminated in the acquittal of Jennings. And thus, while the individual so acting is at this moment on his way to take[xlvii] possession of his appointment as governor of the Gold Coast, the unfortunate man, who he knows cannot be tried a second time, is in prison.