Title: The Mislaid Uncle

Author: Evelyn Raymond

Illustrator: Frank T. Merrill

Release date: March 23, 2021 [eBook #64911]

Language: English

Credits: D A Alexander, David E. Brown, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by the Library of Congress)

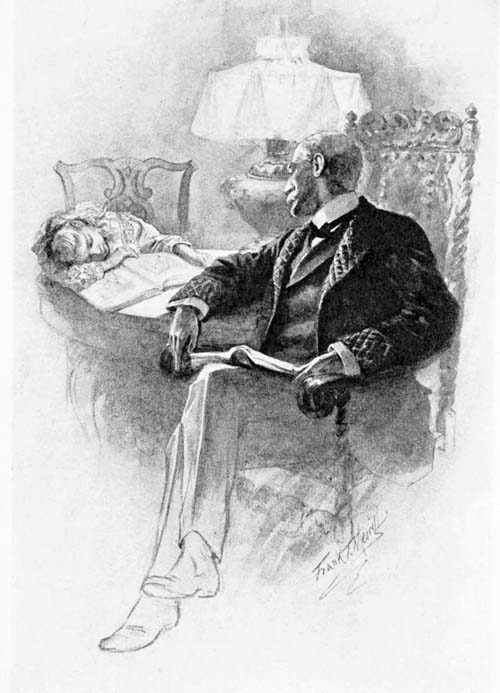

THE LITTLE FACE DROPPED UPON THE OPEN PAGE.

by EVELYN RAYMOND

NEW YORK

THOMAS Y· CROWELL & CO·

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1903,

By Thomas Y. Crowell & Company.

Published September, 1903.

| Chapter | Page | |

| I. | Diverse Ways | 1 |

| II. | A Human Express Parcel | 14 |

| III. | Arrival | 34 |

| IV. | A Multitude of Josephs | 46 |

| V. | A Wild March Morning | 63 |

| VI. | Memories and Melodies | 80 |

| VII. | The Boy from Next Door | 95 |

| VIII. | After the Frolic | 111 |

| IX. | Neighborly Amenities | 123 |

| X. | Tom, Dick, Harry, and the Baby | 138 |

| XI. | The Disposal of the Parcel | 150 |

THE MISLAID UNCLE.

Three people were together in a very pleasant little parlor, in a land where the sun shines nearly all the time. They were Doctor Mack, whose long, full name was Alexander MacDonald; mamma, who was Mrs. John Smith; and Josephine, who was Mrs. Smith’s little girl with a pretty big name of her own.

Doctor Mack called Mrs. Smith “Cousin Helen,” and was very good to her. Indeed, ever since papa John Smith had had to go away and leave his wife and child to house-keep by themselves the busy doctor-cousin had done many things for them, and mamma was accustomed to go to him for advice about[2] all little business matters. It was because she needed his advice once more that she had summoned him to the cottage now; even though he was busier than ever, since he was making ready to leave San Diego that very day for the long voyage to the Philippine Islands.

Evidently the advice that had so promptly been given was not agreeable; for when Josephine looked up from the floor where she was dressing Rudanthy, mamma was crying softly, and Doctor Mack was saying in his gravest take-your-medicine-right-away kind of a voice that there was “nothing else to do.”

“Oh, my poor darling! She is so young, so innocent. I cannot, I cannot!” wailed the mother.

“She is the most self-reliant, independent young lady of her age that I ever knew,” returned the doctor.

Josephine realized that they were talking about her, but didn’t see why that should make her mother sad. It must be all the cousin-doctor’s fault. She had never liked him since he had come a few weeks before, and scratched[3] her arm and made it sore. “Vaccinated” it, mamma had said, to keep her from being ill sometime. Which had been very puzzling to the little girl, because “sometime” might never come, while the arm-scratching had made her miserable for the present. She now asked, in fresh perplexity:

“Am I ‘poor,’ mamma?”

“At this moment I feel that you are very poor indeed, my baby,” answered the lady.

Josephine glanced about the familiar room, in which nothing seemed changed except her mother’s face. That had suddenly grown pale and sad, and even wrinkled, for there was a deep, deep crease between its brows.

“That’s funny. Where are my rags?” asked the child.

Mamma smiled; but the doctor laughed outright, and said:

“There is more than one way of being poor, little missy. Come and show me your arm.”

Josephine shivered as she obeyed. However, there was nothing to fear now, for the[4] arm was well healed, and the gentleman patted it approvingly, adding:

“You are a good little girl, Josephine.”

“Yes, Doctor Mack, I try to be.”

“Yet you don’t love me, do you?”

“Not—not so—so very much,” answered the truthful child, painfully conscious of her own rudeness.

“Not so well as Rudanthy,” he persisted.

“Oh, nothing like!”

“Josephine,” reproved mamma; then caught her daughter in her arms, and began to lament over her. “My darling! my darling! How can I part from you?”

Before any reply could be made to this strange question, the door-bell rang, and there came in another of those blue-coated messenger boys, who had been coming at intervals all that day and yesterday. He brought a telegram which mamma opened with trembling fingers. When she had read it, she passed it to Doctor Mack, who also read it; after which he folded and returned it to the lady, saying:

“Well, Cousin Helen, you must make your[5] decision at once. The steamer starts this afternoon. If you sail by her there’s no time to be lost. If you go, I will delay my own preparations to help you off.”

For one moment more Mrs. Smith stood silent, pressing her hands to her throbbing temples, and gazing at Josephine as if she could not take her eyes from the sweet, childish face. Then she turned toward the kind doctor and said, quite calmly:

“Yes, Cousin Aleck, I will go.”

He went away quickly, and mamma rang the bell for big Bridget, who came reluctantly, wiping her eyes on her apron. But her mistress was not crying now, and announced:

“Bridget, I am starting for Chili by this afternoon’s steamer. Josephine is going to Baltimore by the six o’clock overland. There isn’t a moment to waste. Please bring the empty trunks from the storeroom and pack them while I attend to other matters, though I will help you as I can. Put my clothes into the large trunk and Josephine’s into the small one. There, there, good soul, don’t begin to[6] cry again. I need all my own will to get through this awful day; and please make haste.”

During the busy hours which followed both mamma and Bridget seemed to have forgotten the little girl, save, now and then, to answer her questions; and one of these was:

“What’s Chili, Bridget?”

“Sure, it’s a kind of pickle-sauce, darlin’.”

“Haven’t we got some of it in the cupboard?”

“Slathers, my colleen.”

“Chili is a country, my daughter,” corrected mamma, looking up from the letter she was writing so hurriedly that her pen went scratch, scratch.

“Is it red, mamma?”

“Hush, little one. Don’t be botherin’ the mistress the now. Here’s Rudanthy’s best clothes. Put ’em on, and have her ready for the start.”

“Is Rudanthy going a journey, too, Bridget?”

“‘Over the seas and far away’—or over the land; what differ?”

When the doll had been arrayed in its finery mamma had finished her writing, and, rising[7] from her desk, called the child to her. Then she took her on her lap and said, very earnestly:

“Josephine, you are eight years old.”

“Yes, mamma. This very last birthday that ever was.”

“That is old enough to be brave and helpful.”

“Oh, quite, mamma. I didn’t cry when Doctor Mack vaccinated me, and I sewed a button on my apron all myself.”

“For a time I am obliged to go away from you, my—my precious!”

Josephine put up her hand and stroked her mother’s cheek, begging:

“Don’t cry, mamma, and please, please don’t go away.”

The lady’s answer was a question:

“Do you love papa, darling?”

“Why, mamma! How funny to ask! Course I do, dearly, dearly.”

“Poor papa is ill. Very ill, I fear. He is alone in a far, strange country. He needs me to take care of him. He has sent for me, and I am going to him. But I cannot take you.[8] For many reasons—the climate, the uncertainty—I am going to send you East to your Uncle Joe’s; the uncle for whom you were named, your father’s twin brother. Do you understand me, dear?”

“Yes, mamma. You are going to papa, and I am going to Uncle Joe. Who is going with me there?”

“Nobody, darling. There is nobody who can go. We have no relatives here, except our doctor-cousin, and he is too busy. So we are going to send you by express. It is a safe way, though a lonely one, and— Oh, my darling, my darling; how can I! how can I!”

Ever since papa had gone, so long ago, Josephine had had to comfort mamma. She did so now, smoothing the tear-wet cheek with her fat little hand, and chattering away about the things Bridget had put in her trunk.

“But she mustn’t pack Rudanthy. I can’t have her all smothered up. I will take Rudanthy in my arms. She is so little and so sweet.”

“So little and so sweet!” echoed the mother’s[9] heart, sadly; and it was well for all that Doctor Mack returned just then. For he was so brisk and business-like, he had so many directions to give, he was so cheerful and even gay, that, despite her own forebodings, Mrs. Smith caught something of his spirit, and completed her preparations for departure calmly and promptly.

Toward nightfall it was all over: the parting that had been so bitter to the mother and so little understood by the child. Mamma was standing on the deck of the outward moving steamer, straining her eyes backward over the blue Pacific toward the pretty harbor of San Diego, almost believing she could still see a little scarlet-clad figure waving a cheerful farewell from the vanishing wharf. But Josephine, duly ticketed and labelled, was already curled up on the cushions of her section in the sleeper, and staring out of window at the sights which sped by.

“The same old ocean, but so big, so big! Mamma says it is peacock-blue, like the wadded kimono she bought at the Japanese store. Isn’t it queer that the world should fly[10] past us like this! That’s what it means in the jogaphy about the earth turning round, I suppose. If it doesn’t stop pretty soon I shall get dreadful dizzy and, maybe, go to sleep. But how could I? I’m an express parcel now. Cousin-Doctor Mack said so, and dear mamma. Parcels don’t go to sleep ever, do they, Rudanthy?”

But Rudanthy herself, lying flat in her mistress’ lap, had closed her own waxen lids and made no answer. The only one she could have made, indeed, would have been “Papa,” or “Mamma,” and that wouldn’t have been a “truly” answer, anyway.

Besides, just then a big man, shining with brass buttons and a brass-banded cap, came along and demanded:

“Tickets, please.”

Josephine clutched Rudanthy and woke that indolent creature rather suddenly.

“Dolly, dolly, sit up! The shiny-blue man is hollering at the people dreadful loud. Maybe it’s wrong for dolls to go to sleep in these railway things.”

“WHERE’S YOUR FOLKS?”

[11]The shiny-blue man stopped right at Josephine’s seat, and demanded fiercely, or it sounded fierce to the little girl:

“Sissy, where’s your folks?”

“Please, I haven’t got any,” she answered politely.

“Who do you belong to, then?” asked he.

“I’m Mrs. John Smith’s little girl, Josephine,” she explained.

“Hmm. Well, where’s Mrs. John Smith?” he persisted.

“She’s gone away,” said she, wishing he, too, would go away.

“Indeed. Tell me where to find her. You’re small enough, but there should be somebody else in this section.”

“I guess you can’t find her. She’s sailing and sailing on a steamer to my papa, who’s sick and needs her more ’n I do.”

“Hello! this is odd!” said the conductor, and passed on. But not before he added the caution:

“You stay right exactly where you are, sissy, till I come back. I’ll find out your party and have you looked after.”

[12]Josephine tried to obey to the very letter. She did not even lay aside the doll she had clasped to her breast, nor turn her head to look out of the window. The enchanting, fairy-like landscape might fly by and by her in its bewildering way; she dared gaze upon it no more.

After a while there were lights in the coach, and these made Josephine’s eyes blink faster and faster. They blinked so fast, in fact, that she never knew when they ceased doing so, or anything that went on about her, till she felt herself lifted in somebody’s arms, and raised her heavy lids, to see the shiny-blue man’s face close above her own, and to hear his voice saying:

“Poor little kid! Make her berth up with double blankets, Bob, and keep an eye on it through the night. My! Think of a baby like this making a three-thousand-mile journey alone. My own little ones—Pshaw! What made me remember them just now?”

Then Josephine felt a scratchy mustache upon her check, and a hard thing which might have been a brass button jam itself into her[13] temple. Next she was put down into the softest little bed in the world, the wheels went to singing “Chug-chug-chug,” in the drowsiest sort of lullaby, and that was all she knew for a long time.

But something roused her, suddenly, and she stretched out her hand to clasp, yet failed to find, her own familiar bed-fellow. Missing this she sat up in her berth and shrieked aloud:

“Rudanthy! Ru-dan-thy! RUDANTHY!”

“Hush, sissy! Don’t make such a noise. You’re disturbing a whole car full of people,” said somebody near her.

Josephine suppressed her cries, but could not stifle the mighty sob which shook her. She looked up into the face of the black porter, Bob, studied it attentively, found it not unkind, and regained her self-possession.

“My name is not sissy. It’s Josephine Smith. I want my dolly. I cannot go to sleep without her. Her name is Rudanthy. Fetch me Rudanthy, boy.”

Bob was the most familiar object she had yet seen. He might have come from the big hotel where she and mamma had taken their meals. Her mother’s cottage had been close by, and sometimes of a morning a waiter had brought[15] their breakfast across to them. That waiter was a favorite, and in this dimness she fancied he had appeared before her.

“Do you live at the ‘Florence,’ boy?” she asked.

“No, missy, but my brother does,” he answered.

“Ah! Fetch me Rudanthy, please.”

After much rummaging, and some annoyance to a lady who now occupied the upper berth, the doll was found and restored. But by this time Josephine was wide awake and disposed to ask questions.

“What’s all the curtains hung in a row for, Bob?”

“To hide the berths, missy. I guess you’d better not talk now.”

“No, I won’t. What you doing now, Bob?” she continued.

“Making up the section across from yours, missy. Best go to sleep,” advised the man.

“Oh, I’m not a bit sleepy. Are you?” was her next demand.

“Umm,” came the unsatisfactory response.

[16]“What you say? You mustn’t mumble. Mamma never allows me to mumble. I always speak outright,” was Josephine’s next comment.

“Reckon that’s true enough,” murmured the porter, under his breath.

“What, Bob? I didn’t hear,” from the little girl.

“No matter, I’ll tell you in the morning,” he whispered.

“I’d rather know now.”

No response coming to this, she went on:

“Bob! Please to mind me, boy. I—want—to—hear—now,” very distinctly and emphatically. Josephine had been accustomed to having her wishes attended to immediately. That was about all mamma and big Bridget seemed to live for.

The lady in the berth above leaned over the edge and said, in a shrill whisper:

“Little girl, keep still.”

“Yes, lady.”

Bob finished the opposite section, and a woman in a red kimono came from the dressing-room[17] and slipped behind the curtain. Josephine knew a red kimono. It belonged to Mrs. Dutton, the minister’s wife, and Mrs. Dutton often stayed at mamma’s cottage. Could this be Mrs. Dutton?

The child was out of bed, across the narrow aisle, swaying with the motion of the car, pulling the curtains apart, and clutching wildly at a figure in the lower berth.

“Mrs. Dutton. Oh! Mrs. Dutton! Here’s Josephine.”

“Ugh! Ouch! Eh! What?”

“Oh! ’Xcuse me. I thought you were Mrs. Dutton.”

“Well, I’m not. Go away. Draw that curtain again. Go back to your folks. Your mother should know better than to let you roam about the sleeper at night.”

“My mother knows—everything!” said Josephine, loyally. “I’m dreadful sorry you’re not Mrs. Dutton, ’cause she’d have tooken off my coat and things. My coat is new. My mamma wouldn’t like me to sleep in it. But the buttons stick. I can’t undo it.”

[18]“Go to your mother, child. I don’t wish to be annoyed.”

“I can’t, ’cause she’s over seas, big Bridget says, to that red-pickle country. I s’pose I’ll have to, then. Good-night. I hope you’ll rest well.”

The lady in the red kimono did not feel as if she would. She was always nervous in a sleeping-car, anyway; and what did the child mean by “over seas in the red-pickle country”? Was it possible she was travelling alone? Were there people in the world so foolish as to allow such a thing?

After a few moments of much thinking, the lady rose, carefully adjusted her kimono, and stepped to Josephine’s berth. The child lay holding the curtains apart, much to the disgust of the person overhead, and gazing at the lamp above. Her cheeks were wet, her free hand clutched Rudanthy, and the expression of her face was one that no woman could see and not pity.

“My dear little girl, don’t cry. I’ve come to take off your cloak. Please sit up a minute.”

[19]“Oh, that’s nice! Thank you. I—I—if mamma”—

“I’ll try to do what mamma would. There. It’s unfastened. Such a pretty coat it is, too. Haven’t you a little gown of some sort to put on?”

“All my things are in the satchel. Big Bridget put them there. She told me—I forget what she did tell me. Bob tucked the satchel away.”

“I’ll find it.”

By this time the upper berth lady was again looking over its edge and airing her views on the subject:

“The idea! If I’d known I was going to be pushed off up here and that chit of a child put in below I’d have made a row.”

“I believe you,” said Red Kimono, calmly. “Yet I suppose this lower bed must have been taken and paid for in the little one’s name.”

“’Xcuse me, Mrs. Kimono. I’m not a little one. I’m quite, quite big. I’m Josephine.”

“And is there nobody on this train belonging to you, Miss Josie?” asked Mrs. Red Kimono.

[20]“Josephine. My mamma doesn’t like nicknames. There’s nobody but the expressman. And everybody. Doctor Mack said to my mamma that everybody would take care of me. I heard him. It is the truth. Doctor Mack is a grown-up gentleman. Gentlemen never tell wrong stories. Do they?” asked the little girl.

“They ought not, surely. And we ought not to be talking now. It is in the middle of the night, and all the tired people want to sleep. Are you comfortable? Then curl down here with Rudanthy and shut your eyes. If you happen to wake again, and feel lonely, just come across to my berth and creep in with me. There’s room in it for two when one of the two is so small. Good-night. I’ll see you in the morning.”

Red Kimono ceased whispering, pressed a kiss on the round cheek, and disappeared. She was also travelling alone, but felt not half so lonely since she had comforted the little child, who was again asleep, but smiling this time, and who awoke only when a lady in a[21] plain gray costume pulled the curtains apart and touched her lightly on the shoulder. This was “Red Kimono” in her day attire.

“Time to get up, Josephine. Breakfast is ready and your section-mate will want the place fixed up. May I take you to the dressing-room?”

“Our colleen’s one of them good-natured kind that wakes up wide to-once and laughin’,” had been big Bridget’s boast even when her charge was but an infant, nor had the little girl outgrown her very sensible babyish custom. She responded to the stranger’s greeting with a merry smile and “Good morning!” and was instantly ready for whatever was to come.

She was full of wonder over the cramped little apartment which all the women travellers used in succession as a lavatory, and it may be that this wonder made her submit without hindrance to the rather clumsy brushing of her curls which Red Kimono attempted.

“’Xcuse me, that isn’t the way mamma or big Bridget does. They put me in the bath, first off; then my hair, and then my clothes.[22] Haven’t you got any little girls to your house, Red Kimono?” inquired the young traveller.

“No, dear, I haven’t even a house;” answered the lady, rather sadly. “But your own dear mamma would have to forego the bath on a railway sleeper, so let’s make haste and give the other people their rightful use of this place.”

By this time several women had collected in the narrow passage leading to the dressing-room, and were watching through the crack of its door till Josephine’s toilet should be completed and their own chance could come.

“What makes all them folks out there look so cross, dear Red Kimono?”

“Selfishness, dearie. And hunger. First come best fed, on a railway dining-car, I fancy. There. You look quite fresh and nice. Let us go at once.”

As they passed down the aisle where Bob was swiftly and deftly making the sections ready for the day’s occupancy, Josephine was inclined to pause and watch him, but was[23] hurried onward by her new friend, who advised:

“Don’t loiter, Josephine. If we don’t get to table promptly we’ll miss our seats. Hurry, please.”

“Are you one of the selfish-hungry ones, Mrs. Red Kimono?”

The lady flushed, and was about to make an indignant reply, but reflected that indignation would be wasted on such a little person as this.

“It may be that I am, child. Certainly I am hungry, and so should you be. I don’t remember seeing you at supper last night.”

“I had my supper with Doctor Mack before we started. Oh, he was nice to me that time. He gave me turkey and mince-pie, and—and everything that was on the bill of fare that I wanted, so’s I wouldn’t cry. He said I’d be sick, but he didn’t mind that so long as I didn’t cry. He hates crying people, Doctor Mack does. He likes mamma ’cause she’s so brave. Once my papa was a soldier, and he’s a Company F man now; but most he’s a ’lectrickeller,[24] and has to go away to the funny pickle place to earn the money for mamma and me. So then she and me never cry once. We just keep on laughing like we didn’t mind, even if we do hate to say good-by to papa for so long a while. I said I wouldn’t cry, not on all this car ride; never, not at all. I—maybe I forgot, though. Did I cry last night, Mrs. Red Kimono?”

“Possibly, just a little; not worth mentioning. Here, dear, climb into this chair,” was the lady’s hasty reply.

“What a cute table! Just like hotel ones, only littler. It’s dreadful wobbly, though. It makes my head feel funny. I—oh! I’m—I guess—I’m sick!”

The lady shivered quite as visibly as poor Josephine. The dining-car was the last one of the long train, and swayed from side to side in a very unpleasant manner. The motion did not improve anybody’s appetite, and the grown-up traveller was now vexed with herself for befriending the childish one.

“She was nothing to me. Why should I[25] break over my fixed rules of looking out for number one and minding my own business? Well, I’ll get through this meal somehow, and then rid my hands of the matter. I’m not the only woman in our car. Let some of the others take a chance. The idea! sending a little thing like that to travel alone. It’s preposterous—perfectly preposterous.”

Unconsciously she finished her thought aloud, and Josephine heard her, and asked:

“What does it mean, that big word, Mrs. Kimono?”

“It means—my name is—isn’t—no matter. Are you better? Can you eat? It’s small wonder you were upset after the supper that foolish doctor gave you. What is your breakfast at home?”

“Oatmeal and fruit. Sometimes, if I’m good, some meat and potato.”

“I will order it for you.”

“Thank you, but I can order for myself. Mamma always allows me to. She wishes me to be myself, not anybody else,” returned the child.

“Oh, indeed! Then do so.”

[26]Josephine recognized from the lady’s tone that she had given offence, though didn’t know why. Now, it was another of her wise mother’s rules that her little daughter should punish herself when any punishment was needed. Opinions didn’t always agree upon the subject, yet, as a rule, the conscientious child could be trusted to deal with her own faults more sternly than anybody else would do. She realized that here was a case in point, and, though the steak and potatoes which Red Kimono ordered for herself looked very tempting, asked only for oatmeal and milk, “without any sugar, if you please, boy.”

The lady frowned inquiringly.

“Are you still ill, Josephine?”

“No, Mrs. Kimono.”

“Aren’t you hungry?”

“Dreadful.” Indeed, the hunger was evident enough.

“Then why don’t you take some heartier food? If you’re bashful— Yet you’re certainly not that. If you’re hungry, child, for goodness sake eat.”

[27]“It’s for goodness sake I can’t. I daren’t. It wouldn’t be right. Maybe I can eat my dinner. Maybe.”

Tears were very near the big brown eyes, but the sweet little face was turned resolutely away from the table toward the window and the sights outside. One spoonful of unsweetened, flavorless meal was gulped down, and the trembling lips remarked:

“It’s all begun again, hasn’t it?”

“What’s begun, Josephine?”

“The all-out-doors to go by and by us, like it did last night.”

“It is we who are going by the ‘all-out-doors,’ dear. The train moves, the landscape stands still. Were you never on the cars before?” inquired the lady.

“Never, not in all my whole life.”

“Indeed! But that’s not been such a long time, after all.”

Another brave effort at the plain breakfast, and the answer came:

“It’s pretty long to me. It seems—forever since yesterday!”

[28]The lady could not endure the sight of Josephine’s evident distress and softly slipped a morsel of juicy steak upon the oatmeal saucer. With gaze still averted the spoon came down into the dish, picked up the morsel, and conveyed it to the reluctant mouth. The red lips closed, smacked, opened, and the child faced about. With her napkin to hide the movement she carefully replaced the morsel on the empty plate beside the saucer and said, reproachfully:

“You oughtn’t to done that, Mrs. Kimono. Don’t you s’pose it’s bad enough to be just starved, almost, and not be tempted? That’s like big Bridget; and my mamma has to speak right sharp to her, she has. Quite often, too. Once it was pudding, and I—I ate it. Then I had to do myself sorry all over again. Please ’xcuse me.”

“You strange child! Yes, I will excuse you. I’m leaving table myself. You mustn’t attempt to go back through the train to our car alone. Eh? What? Beg pardon?” she said, turning around.

[29]An official in uniform was respectfully addressing the lady:

“Pardon, madam, but I think this must be my little ‘Parcel.’ I’ve been looking for her. Did you have your breakfast, little girl?”

“Yes, thank you,” she answered.

“I hope you enjoyed it.”

“I didn’t much,” was her frank reply to this kind wish.

“Why, wasn’t it right? Here, waiter! I want you to take this young lady under your special care. See that she has the best of everything, and is served promptly, no matter who else waits. It’s a point of honor with the service, madam,” he explained to the wondering lady beside them.

“The service? Beg pardon, but I don’t understand. The child seemed to be alone and I tried to look after her a bit.”

“Thank you for doing so, I’m sure. The Express Service, I refer to. I’m the train agent between San Diego and Chicago; she is under my care. There the agent of the other line takes her in charge. She’s billed[30] through to Baltimore and no expense is to be spared by anybody concerned, that she makes the trip in safety and the greatest possible comfort. We flatter ourselves, madam, that our company can fix the thing as it should be. She’s not the first little human ‘parcel’ we’ve handled successfully. Is there anything you’d like, Miss”—

He paused, pulled a notebook from his pocket, discovered her name, and concluded:

“Miss Josephine Smith?”

“Smith, Josephine Smith, singular!” murmured Mrs. Kimono, under her breath. “But not so singular after all. Smith is not an uncommon name, nor Baltimore the only city where Smiths reside.”

Meanwhile the express agent had taken Josephine’s hand in his, and was carefully guiding her back through the many carriages to the one where she belonged. His statement that Doctor Mack had put her into his care made her consider him an old friend, and loosened her tongue accordingly.

Porter Bob received her with a smile, and[31] asked if he had arranged her half of the section to her pleasure; pointed out that Rudanthy’s attire had been duly brushed, and begged her not to hesitate about ringing for him whenever she needed him.

By this time Mrs. Upper Berth, as the child mentally called her, had returned from her own breakfast and proved to be “not half so cross as you sounded, are you?”

To which the lady replied with a laugh and the assurance that tired people were apt to be a “little crisp,” then added:

“But I’ve heard all about you now, my dear; and I’m glad to have as section-mate such a dainty little ‘parcel.’ I’m sure we’ll be the best of friends before we reach our parting-place at Chicago.”

So they proved to be. So, indeed, did everybody in the car. “Little Parcel” was made so much of by the grown-up travellers that she might have been spoiled had the journey continued longer than it did. But at Chicago a change was made. The express agent put her into a carriage, and whisked her away to[32] another station, another train, and a new, strange set of people. Not a face with which she had become familiar during the first stage of her long journey was visible. Even Bob had disappeared, and in his stead was a gray-haired porter who grumbled at each of the demands, such as it had become natural for her to make upon the friendly Bob.

There was no Red Kimono in the section opposite; not even a be-spectacled Upper Berth lady to make whimsical comments on her neighbors; and the new agent to whom she had been transferred looked cross, as if he were in a dreadful hurry and hated to be bothered. Altogether things were changed for the worse, and Josephine’s heart would perhaps have broken if it hadn’t been for the dear companionship of Rudanthy, who smiled and slept in a placid waxen manner that was restfully familiar.

Besides, all journeys have an end; and the six days’ trip of the little San Diegan came to its own before the door of a stately mansion, gay with the red brick and white marble which[33] mark most Baltimore homes, and the ring of an electric bell that the expressman touched:

“A ‘parcel’ for Joseph Smith. Billed from San Diego, Cal. Live here, eh?”

It was a colored man in livery who replied:

“Yes, suh. Mister Joseph Smith, he done live here, suh.”

“Sign, please. That is, if you can write.”

“Course I can write. I allays signs parcels for Mister Smith, suh. Where’s the parcel at, suh?” returned the liveried negro.

“Sign. I’ll fetch it,” came the prompt answer.

Old Peter signed, being the trusted and trustworthy servant of his master, and returned the book to the agent’s hands, who himself returned to the carriage, lifted out Josephine and Rudanthy, conveyed them up the glistening steps, and left them to their fate.

Peter stared, but said nothing. Not even when the agent ran back from the carriage with a little satchel and a strap full of shawls and picture-books. The hack rolled away, the keen March wind chilled the young Californian, who stood, doll in hand, respectfully waiting admission to the warm hall beyond the door. Finally, since the servant seemed to have been stricken speechless, she found her own voice, and said:

“Please, boy, I’d like to see my Uncle Joe.”

“Your—Uncle—Joe, little miss?”

“That’s what I said. I must come in. I’m very cold. If this is Baltimore, that the folks on the cars said was pretty, I guess they didn’t know what they were talking about. I want to come in, please.”

[35]The old man found his wits returning. This was the queerest “parcel” for which he had ever signed a receipt in an express-book, and he knew there was some mistake. Yet he couldn’t withstand the pleading brown eyes under the scarlet hat, even if he hadn’t been “raised” to a habit of hospitality.

“Suah, little lady. Come right in. ’Tis dreadful cold out to-day. I ’most froze goin’ to market, an’ I’se right down ashamed of myself leavin’ comp’ny waitin’ this way. Step right in the drawin’-room, little missy, and tell me who ’tis you’d like to see.”

Picking up the luggage that had been deposited on the topmost of the gleaming marble steps, which, even in winter, unlike his neighbors, the master of the house disdained to hide beneath a wooden casing, the negro led the way into the luxurious parlor. To Josephine, fresh from the chill of the cloudy, windy day without, the whole place seemed aglow. A rosy light came through the red-curtained windows, shone from the open grate, repeated itself in the deep crimson carpet that was so delightfully soft and warm.

[36]“Sit down by the fire, little lady. There. That’s nice. Put your dolly right here. Maybe she’s cold, too. Now, then, suah you’se fixed so fine you can tell me who ’tis you’ve come to see,” said the man.

“What is your name, boy?” inquired Josephine.

“Peter, missy. My name’s Peter.”

“Well, then, Peter, don’t be stupid. Or are you deaf, maybe?” she asked.

“Land, no, missy. I’se got my hearin’ fust class,” he replied, somewhat indignantly.

“I have come to see my Uncle Joe. I wish to see him now. Please tell him,” she commanded.

The negro scratched his gray wool and reflected. He had been born and raised in the service of the family where he still “officiated,” and knew its history thoroughly. His present master was the only son of an only son, and there had never been a daughter. No, nor wife, at least to this household. There were cousins in plenty, with whom Mr. Joseph Smith was not on good terms. There were[37] property interests dividing them, and Mr. Joseph kept his vast wealth for his own use alone. Some thought he should have shared it with others, but he did not so think and lived his quiet life, with a trio of colored men-servants. His house was one of the best appointed on the wide avenue, but, also, one of the quietest. It was the first time that old Peter had ever heard a child’s voice in that great room, and its clear tones seemed to confuse him.

“I want to see my Uncle Joe. I want to see him right away. Go, boy, and call him,” Josephine explained.

This was command, and Peter was used to obey, so he replied:

“All right, little missy, I’ll go see. Has you got your card? Who shall I say ’tis?”

Josephine reflected. Once mamma had had some dear little visiting cards engraved with her small daughter’s name, and the child remembered with regret that if they had been packed with her “things” at all, it must have been in the trunk, which the expressman said[38] would arrive by and by from the railway station. She could merely say:

“Uncles don’t need cards when their folks come to see them. I’ve come from mamma. She’s gone to the pickley land to see papa. Just tell him Josephine. What’s that stuff out there?”

She ran to the window, pulled the lace curtains apart, and peered out. The air was now full of great white flakes that whirled and skurried about as if in the wildest sort of play.

“What is it, Peter? Quick, what is it?” she demanded.

“Huh! Don’t you know snow when you see it, little missy? Where you lived at all your born days?” he cried, surprised.

“Oh, just snow. Course I’ve seen it, coming here on the cars. It was on the ground, though, not in the air and the sky. I’ve lived with mamma. Now I’ve come to live with Uncle Joe. Why don’t you tell him? If a lady called to see my mamma do you s’pose big Bridget wouldn’t say so?”

“I’se goin’,” he said, and went.

[39]But he was gone so long, and the expected uncle was so slow to welcome her, that even that beautiful room began to look dismal to the little stranger. The violent storm which had sprung up with such suddenness, darkened the air, and a terrible homesickness threatened to bring on a burst of tears. Then, all at once, Josephine remembered what Doctor Mack had said:

“Don’t be a weeper, little lady, whatever else you are. Be a smiler, like my Cousin Helen, your mamma. You’re pretty small to tackle the world alone, but just do it with a laugh and it will laugh back upon you.”

Not all of which she understood, though she recalled every one of the impressive words, but the “laughing part” was plain enough.

“Course, Rudanthy. No Uncle Joe would be glad to get a crying little girl to his house. I’ll take off my coat and yours, darling. You are pretty tired, I guess. I wonder where they’ll let us sleep, that black boy and my uncle. I hope the room will have a pretty fire in it, like this one. Don’t you?”

[40]Rudanthy did not answer, but as Josephine laid her flat upon the carpet, to remove her travelling cloak, she immediately closed her waxen lids, and her little mother took this for assent.

“Oh, you sweetest thing! How I do love you!”

There followed a close hug of the faithful doll, which was witnessed by a trio of colored men from a rear door, where they stood, open-eyed and mouthed, wondering what in the world the master would say when he returned and found this little trespasser upon his hearth-stone.

When Rudanthy had been embraced, to the detriment of her jute ringlets and her mistress’ comfort, Josephine curled down on the rug before the grate to put the doll asleep, observing:

“You’re so cold, Rudanthy. Colder than I am, even. Your precious hands are like ice. You must lie right here close to the fire, ’tween me and it. By-and-by Uncle Joe will come and then—My! Won’t he be surprised?[41] That Peter boy is so dreadful stupid, like’s not he’ll forget to say a single word about us. Never mind. He’s my papa’s twin brother. Do you know what twins are, Rudanthy? I do. Big Bridget’s sister’s got a pair of them. They’re two of a kind, though sometimes one of them is the other kind. I mean, you know, sometimes one twin isn’t a brother, it’s a sister. That’s what big Bridget’s sister’s was. Oh, dear. I’m tired. I’m hungry. I liked it better on that nice first railway car where everybody took care of me and gave me sweeties. It’s terrible still here. I—I’m afraid I’m going to sleep.”

In another moment the fear of the weary little traveller had become a fact. Rudanthy was already slumbering; and, alas! that was to prove the last of her many naps. But Josephine was unconscious of the grief awaiting her own awakening; and, fortunately, too young to know what a different welcome should have been accorded herself by the relative she had come so far to visit.

Peter peeped in, from time to time, found[42] all peaceful, and retired in thankfulness for the temporary lull. He was trembling in his shoes against the hour when the master should return and find him so unfaithful to his trust as to have admitted that curly-haired intruder upon their dignified privacy. Yet he encouraged himself with the reflection:

“Well, no need crossin’ no bridges till you meet up with ’em, and this bridge ain’t a crossin’ till Massa Joe’s key turns in that lock. Reckon I was guided to pick out that fine duck for dinner this night, I do. S’posin’, now, the market had been poor? Huh! Every trouble sets better on a full stummick ’an a empty. Massa Joe’s powerful fond of duck, lessen it’s spoiled in the cookin’. I’ll go warn that ’Pollo to be mighty careful it done to a turn.”

Peter departed kitchen ward, where he tarried gossipping over the small guest above stairs and the probable outcome of her advent.

“Nobody what’s a Christian goin’ to turn a little gell outen their doors such an evenin’ as this,” said Apollo, deftly basting the fowl in the pan.

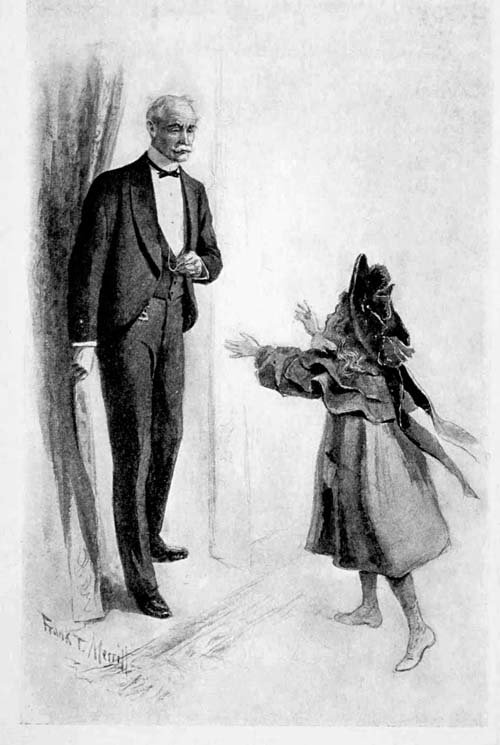

“I’M JOSEPHINE!”

[43]“Mebbe not, mebbe not. But I reckon we can’t, none of us, callate on whatever Massa Joe’s goin’ to do about anything till he does it. He’s off to a board meeting, this evening, and I hope he sets on it comfortable. When them boards are too hard, like, he comes home mighty ’rascible. Keep a right smart watch on that bird, ’Pollo, won’t you? whiles I go lay the table.”

But here another question arose to puzzle the old man. Should he, or should he not, prepare that table for the unexpected guest? There was nobody more particular than Mr. Smith that all his orders should be obeyed to the letter. Each evening he wished his dinner to be served after one prescribed fashion, and any infraction of his rules brought a reprimand to Peter.

However, in this case he determined to risk a little for hospitality’s sake, reflecting that if the master were displeased he could whisk off the extra plate before it was discovered.

“Massa Joe’s just as like to scold if I don’t[44] put it on as if I do. Never allays account for what’ll please him best. Depends on how he takes it.”

Busy in his dining-room he did not hear the cab roll over the snowy street and stop at the door, nor the turn of the key in the lock. Nor, lost in his own thoughts, did the master of the house summon a servant to help him off with his coat and overshoes. He repaired immediately to his library, arranged a few papers, went to his dressing-room and attired himself for dinner, with the carefulness to which he had been trained from childhood, and afterward strolled leisurely toward the great parlor, turned on the electric light, and paused upon its threshold amazed, exclaiming:

“What is this? What in the world is—this?”

The sudden radiance which touched her eyelids, rather than his startled exclamation, roused small Josephine from her restful nap. She sat up, rubbed her eyes, which brightened with a radiance beyond that of electricity, and sprang to her feet. With outstretched arms[45] she flung herself upon the astonished gentleman, crying:

“Oh, you beautiful, beautiful man! You darling, precious Uncle Joe! I’m Josephine! I’ve come!”

“So I perceive!” responded the master of the house, when he could rally from this onslaught of affection. “I’m sure I’m very pleased to welcome you. I—when—how did you arrive?”

“I’m a ’xpress ‘parcel,’” she answered, laughing, for she had learned before this that she had made her long journey in rather an unusual fashion. “Mamma had to go away on the peacock-blue ocean; and Doctor Mack couldn’t bother with me, ’cause he’s going to the folks that eat almonds together and give presents; and there wasn’t anybody else ’xcept big Bridget, and she’d spent all her money, and mamma said you wouldn’t want a ‘wild Irish girl’ to plague you. Would you?”

“I’m not fond of being plagued by anybody,”[47] said the gentleman, rather dryly. He was puzzled as much by her odd talk as her unexpected appearance, and wondered if children so young were ever lunatics. The better to consider the matter he sat down in the nearest chair, and instantly Josephine was upon his knee. The sensation this gave him was most peculiar. He didn’t remember that he had ever taken any child on his lap, yet permitted this one to remain there, because he didn’t know what better to do. He had heard that one should treat a lunatic as if all vagaries were real. Opposition only made an insane person worse. What worse could this little crazy creature, with the lovely face and dreadful manners, do to a finical old bachelor in evening clothes than crush the creases out of his trouser knees?

The lap was not as comfortable as Doctor Mack’s, and far, far from as cosey as mamma’s. Uncle Joe’s long legs had a downward slant to them that made Josephine’s perch upon them rather uncertain. After sliding toward the floor once or twice, and hitching up again, she[48] slipped to her feet and leaned affectionately against his shoulder, saying:

“That’s better. I guess you’re not used to holding little girls, are you, Uncle Joe?”

“No, Josephine. What is your other name?” said he.

“Smith. Just like yours. You’re my papa’s dear twin, you know.”

“Oh, am I?” he asked.

“Course. Didn’t you know that? How funny. That’s because you haven’t mamma to remind you, I s’pose. Mamma remembers everything. Mamma never is naughty. Mamma knows everything. Mamma is dear, dear, dear. And, oh, I want her, I want her!”

Josephine’s arms went round the gentleman’s neck, and her tears fell freely upon his spotless shirt-front. She had been very brave, she had done what she promised Doctor Mack, and kept a “laughing front” as long as she could; but now here, in the home of her papa’s twin, with her “own folks,” her self-control gave way, and she cried as she had never cried before in all her short and happy life.

[49]Mr. Smith was hopelessly distressed. He didn’t know what to say or do, and this proved most fortunate for both of them. For whatever he might have said would have puzzled his visitor as greatly as she was puzzling him. Happily for both, the deluge of tears was soon over, and Josephine lifted a face on which the smiles seemed all the brighter because of the moisture that still bedewed it.

“Please ’xcuse me, Uncle Joe. I didn’t mean to cry once, but it—it’s so lovely to have you at last. It was a long, long way on the railway, uncle. Rudanthy got terribly tired,” explained the visitor.

“Did she? Who is Rudanthy?”

“You, my uncle, yet don’t know Rudanthy, that has been mine ever since I was? Mamma says she has to change heads now and then, and once in awhile she buys her a new pair of feet or hands; but it’s the same darling dolly, whether her head’s new or old. I’ll fetch her. It’s time she waked up, anyway.”

Josephine sped to the rug before the grate,[50] stooped to lift her playmate, paused, and uttered a terrified cry.

“Uncle! Uncle Joe, come here quick—quick!”

Smiling at his own acquiescence, the gentleman obeyed her demand, and stooped over her as she also bent above the object on the rug. All that was left of poor Rudanthy—who had travelled three thousand miles to be melted into a shapeless mass before the first hearth-fire which received her.

Josephine did not cry now. This was a trouble too deep for tears.

“What ails her, Uncle Joe? I never, never saw her look like that. Her nose and her lips and her checks are all flattened out, and her eyes—her eyes are just round glass balls. Her lovely curls”— The little hands flew to the top of the speaker’s own head, but found no change there. Yet she looked up rather anxiously into the face above her. “Do you s’pose I’d have got to look that dreadful way if I hadn’t waked up when I did, Uncle Joe?”

“No, Josephine. No, indeed. Your unhappy[51] Rudanthy was a waxen young person who was indiscreet enough to lie down before an open fire. You seem to be real flesh and blood, and might easily scorch, yet would hardly melt. Next time you take a nap, however, I’d advise you to lie on a lounge or a bed.”

“I will. I wouldn’t like to look like her. But what shall I do? I don’t know a store here,” she wailed.

“I do. I might be able to find you a new doll, if you won’t cry,” came the answer which surprised himself.

“Oh, I shan’t cry any more. Never any more—if I can help it. That’s a promise. But I shouldn’t want a new doll. I only want a head. Poor Rudanthy! Do you s’pose she suffered much?” was the next anxious question.

“It’s not likely. But let Rudanthy lie yonder on the cool window sill. I want to talk with you. I want you to answer a few questions. Sit down by me, please. Is this comfortable?”

Josephine sank into the midst of the cushions[52] he piled for her on the wide sofa and sighed luxuriously, answering:

“It’s lovely. This is the nicest place I ever, ever saw.”

“Thank you. Now, child, tell me something about other places you remember, and, also, please tell me your name.”

Josephine was surprised. What a very short memory this uncle had, to be sure. It wouldn’t be polite to say so, though, and it was an easy question to answer.

“My name is Josephine Smith. I’m named after you, you know, ’cause you’re my papa’s twin. I’m sent to you because”—and she went on to explain the reasons, so far as she understood them, of her long journey and her presence in his house. She brought her coat and showed him, neatly sewed inside its flap, a square of glazed holland on which was written her name, to whom consigned, and the express company by which she had been “specially shipped and delivered.”

It was all plain and straightforward. This was the very house designated on the tag, and[53] he was Joseph Smith; but it was, also, a riddle too deep for him to guess.

“I see, I see. Well, since you are here we must make the best of it. I think there’s a mistake, but I dare say the morning will set it all right. Meanwhile, it’s snowing too fast to make any inquiries to-night. It is about dinner time, for me. Have you had your dinner?” asked the host.

“I had one on the train. That seems a great while ago,” said the guest.

“I beg pardon, but I think there is a little smut upon your pretty nose. After a railway journey travellers usually like to wash up, and so on. I don’t know much about little girls, yet”—he rather timidly suggested.

“I should be so glad. Just see my hands, Uncle Joe!” and she extended a pair of plump palms which sadly needed soap and water.

“I’m not your”—he began, meaning to set her right concerning their relationship; then thought better of it. What would a child do who had come to visit an unknown uncle and found herself in the home of a stranger?[54] Weep, most likely. He didn’t want that. He’d had enough of tears, as witness one spoiled shirt-front. He began also to change his mind regarding the little one’s manners. She had evidently lived with gentlefolks and when some one came to claim her in the morning he would wish them to understand that she had been treated courteously.

So he rang for Peter, who appeared as suddenly as if he had come from the hall without.

“Been listening at the doorway, boy? Take care. Go up to the guest room, turn on the heat and light, and see that there are plenty of fresh towels. Take this young lady’s things with you. She will probably spend the night here. I hope you have a decent dinner provided.”

“Fine, Massa Joe. Just supreme. Yes, suh. Certainly, suh,” answered the servant.

“Uncle Joe, is there a bathroom in this house?” asked she.

“Three of them, Josephine.”

“May I use one? I haven’t had a bath since I was in San Diego, and I’m—mamma would[55] not allow me at table, I guess; I’m dreadful dirty.”

If Josephine had tried to find the shortest way to Mr. Smith’s heart she could not have chosen more wisely.

“To be sure, to be sure. Peter, make a bath ready next the guest room. Will an hour give you time enough, little lady?”

“I don’t want so long. I’m so glad I learned to dress myself, aren’t you? ’Cause all the women to this house seem to be men, don’t they?”

“Yes, child. Poor, unfortunate house!”

“It’s a beautiful house, Uncle Joe; and you needn’t care any more. I’ve come, now. I, Josephine. I’ll take care of you. Good-by. When you see me again I’ll be looking lovely, ’cause I’ll put on the new white wool dress that mamma embroidered with forget-me-nots.”

“Vanity!” thought Mr. Smith, regretfully, which shows that he didn’t as yet understand his little visitor, whose “lovely” referred to her clothes alone, and not at all to herself.

[56]The dinner hour at 1000 Bismarck Avenue was precisely half-past six. Even for the most notable of the few guests entertained by the master of the house he rarely delayed more than five minutes, and on no occasion had it been served a moment earlier. The old-fashioned hall clock had ticked the hour for generations of Smiths “from Virginia,” and was regulated nowadays by the tower timepiece at Mt. Royal station. It was fortunate for Josephine that just as the minute hand dropped to its place, midway between the six and seven on the dial, she came tripping down the wide stair, radiant from her bath and the comfort of fresh clothing, and eager to be again with the handsome Uncle Joe, who was waiting for her at the stair’s foot with some impatience.

Her promptness pleased him, and the uncommon vision of her childish loveliness pleased him even more. He had believed that he disliked children, but was now inclined to change his opinion.

“I’m glad you are punctual, Miss Josephine, else I’d have had to begin my dinner without[57] you. I never put back meals for anybody,” he remarked.

“Would you? Don’t you? Then I’m glad, too. Isn’t the frock pretty? My mamma worked all these flowers with her own little white hands. I love it. I had to kiss them before I could put it on,” she said, again lifting her skirt and touching it with her lips.

“I suppose you love your mamma very dearly. What is she like?”

He was leading her along the hall toward the dining-room, and Peter, standing within its entrance, congratulated himself that he had laid the table for two. He glanced at his master’s face, found it good-natured and interested, and took his own cue therefrom.

“She is like—she is like the most beautiful thing in the world, dear Uncle Joe. Don’t you remember?” asked the astonished child.

“Well, no, not exactly.”

“That’s a pity, and you my papa’s twin. Papa hasn’t nice gray hair like yours, though, and there isn’t any shiny bare place on top of his head. I mean there wasn’t when he went[58] away last year. His hair was dark, like mamma’s, and his mustache was brown and curly. I think he isn’t as big as you, Uncle Joe, and his clothes are gray, with buttony fixings on them. He has a beautiful sash around his waist, sometimes, and lovely shoulder trimmings. He’s an officer, my papa is, in Company F. That’s for ’musement, mamma says. For the business, he’s a ’lectrickeller. Is this my place? Thank you, Peter.”

Mr. Smith handed his little visitor to her chair, which the old butler had pulled back for her, with the same courtly manner he would have shown the pastor’s wife. Indeed, if he had been asked he would have admitted that he found the present guest the more interesting of the two.

Peter made ready to serve the soup, but a look from the strange child restrained him. She added a word to the look:

“Why, boy, you forgot. Uncle Joe hasn’t said the grace yet.”

Now, Mr. Smith was a faithful and devout church member, but was in the habit of omitting[59] this little ceremony at his solitary meals. He was disconcerted for the moment, but presently bowed his head and repeated the formula to which he had been accustomed in his youth. It proved to be the same that the little girl was used to hearing from her own parents’ lips, and she believed it to be the ordinary habit of every household. She did not dream that she had instituted a new order of things, and unfolded her napkin with a smile, saying:

“Now, I’m dreadful hungry, Uncle Joe. Are you?”

“I believe I am, little one.”

Peter served with much dignity and flourish; but Josephine had dined at hotel tables often enough to accept his attentions as a matter of course. Her quiet behavior, her daintiness, and her chatter, amused and delighted her host. He found himself in a much better humor than when he returned through the storm from an unsatisfactory board meeting, and was grateful for the mischance which had brought him such pleasant company.

As for old Peter, his dark face glowed with[60] enthusiasm. He was deeply religious, and now believed that this unknown child had been sent by heaven itself to gladden their big, empty house. He didn’t understand how his master could be “uncle” to anybody, yet, since that master accepted the fact so genially, he was only too glad to do likewise.

It was a fine and stately dinner, and as course after course was served, Josephine’s wonder grew, till she had to inquire:

“Is it like this always, to your home, Uncle Joe?”

“What do you mean?” he asked.

“Such a birthday table, and no folks, ’xcept you and me.”

“It is the same, usually, unless Peter fails to find a good market. Have you finished? No more cream or cake?” he explained and questioned.

“No, thank you. I’m never asked to take two helpings. Only on the car I had three, sometimes, though I didn’t eat them. Mamma wouldn’t have liked it.”

[61]“And do you always remember what ‘mamma’ wishes?”

“No. I’m a terrible forgetter. But I try. Somehow it’s easier now I can’t see her,” she answered.

“Quite natural. Suppose we go into the library for a little while. I want to consult the directory.”

She clasped his hand, looked up confidingly, but felt as if she should fall asleep on the way thither. She wondered if it ever came bedtime in that house, and how many hours had passed since she entered it.

“There, Miss Josephine, I think you’ll find that chair a comfortable one,” said the host, when they had reached the library, rich with all that is desirable in such a room. “Do you like pictures?”

“Oh, I love them!”

“That’s good. So do I. I’ll get you some.”

But Mr. Smith was not used to the “loves” of little girls, and his selection was made rather because he wanted to see how she would handle[62] a book than because he thought about the subject chosen. A volume of Dore’s grotesque drawings happened to be in most shabby condition, and he reflected that she “couldn’t hurt that much, anyway, for it’s to be rebound.”

Afterward he opened the directory for himself, and Josephine thought it a dull-looking book. For some time both were interested and silent; then Uncle Joe cried out with startling suddenness:

“Three thousand Smiths in this little city; and seventy-five of them are Josephs! Well, my child, you’re mighty rich in ‘uncles’!”

Josephine was half-asleep. A woman would have thought about her fatigue and sent her early to bed. “Uncle Joe” thought of nothing now save the array of common and uncommon names in the city directory. He counted and recounted the “Smiths,” “Smyths,” and “Smythes,” and jotted down his figures in a notebook. He copied, also, any address of any Smith whose residence was in a locality which he considered suitable for relatives of his small guest. He became so absorbed in this study that an hour had passed before he remembered her, and the extraordinary quiet of her lively tongue.

Josephine had dozed and waked, dozed and waked, and dreamed many dreams during that hour of silence. Her tired little brain was all[64] confused with the weird pictures of tortured men gazing at her from the trunks of gnarled trees, and thoughts of a myriad of uncles, each wearing eyeglasses, and sitting with glistening bald head beneath a brilliant light. The light dazzled her, the dreams terrified her, and the little face that dropped at length upon the open page of the great folio was drawn and distressed.

“For goodness sake! I suppose she’s sleepy. I believe that children do go to bed early. At least they should. If I’m to be a correct sort of ‘uncle,’ even for one night, I must get her there. I wonder how!” considered the gentleman.

The first thing was to wake her, and he attempted it, saying:

“Josephine! Josephine!”

The child stirred uneasily, but slumbered on.

“Uncle Joe” laid his hand upon her shoulder rather gingerly. He was much more afraid of her than she could ever be of him.

“Miss Josephine! If you please, wake up.”

[65]She responded with a suddenness that startled him.

“Why—where am I? Oh! I know. Did I go to sleep, Uncle Joe?”

“I should judge that you did. Would you like to go to bed?”

“If you please, uncle.”

He smiled faintly at the odd situation in which he found himself, playing nurse to a little girl. A boy would have been less disconcerting, for he had been a boy himself, once, and remembered his childhood. But he had never been a little girl, had never lived in a house with a little girl, and didn’t know how little girls expected to be treated. He volunteered one question:

“If somebody takes you to your room, could you—could you do the rest for yourself, Josephine?”

“Why, course. I began when I was eight years old. That was my last birthday that ever was. Big Bridget was not to wait on me any more after that, mamma said. But she did. She loved it. Mamma, even, loved it,[66] too. And nobody need go upstairs with me. I know the way. I remember it all. If— May I say my prayers by you, Uncle Joe? Mamma”—

One glance about the strange room, one thought of the absent mother, and the little girl’s lip quivered. Then came a second thought, and she remembered her promise. She was never to cry again, if she could help it. By winking very fast and thinking about other things than mamma and home she would be able to help it.

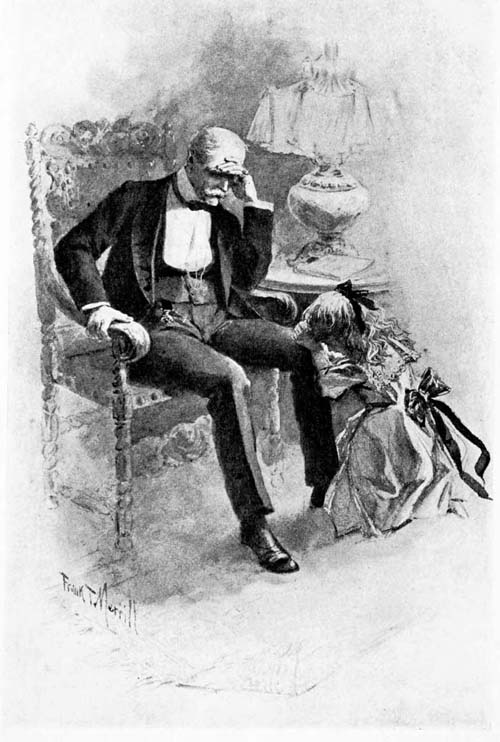

Before he touched her shoulder to wake her, Mr. Smith had rung for Peter, who now stood waiting orders in the parting of the portière, and beheld a sight such as he had never dreamed to see in that great, lonely house: Josephine kneeling reverently beside his master’s knee, saying aloud the Lord’s Prayer and the familiar “Now I lay me.”

Then she rose, flung her arms about the gentleman’s neck, saw the moisture in his eyes, and asked in surprise:

“NOW I LAY ME.”

“Do you feel bad, Uncle Joe? Aren’t you[67] happy, Uncle Joe? Can’t I help you, you dear, dear man?”

The “dear” man’s arms went round the little figure, and he drew it close to his lonely heart with a jealous wish that he might always keep it there. All at once he felt that he hated that other unknown, rightful uncle to whom this charming “parcel” belonged, and almost he wished that no such person might ever be found. Then he unclasped her clinging arms and—actually kissed her!

“You are helping me very greatly, Josephine. You are a dear child. Peter will see that your room is all right for the night. Tell him anything you need and he’ll get it for you. Good-night, little girl.”

“Good-night, Uncle Joe. Dear Uncle Joe. I think—I think you are just too sweet for words! I hope you’ll rest well. Good-night.”

She vanished through the curtains, looking back and kissing her finger-tips to him, and smiling trustingly upon him to the last. But the old man sat long looking after her before he turned again to his books, reflecting:

[68]“Strange! Only a few hours of a child’s presence in this silent place, yet it seems transfigured. ‘An angel’s visit,’ maybe. To show me that, after all, I am something softer and more human than the crusty old bachelor I thought myself. What would her mother say, that absent, perfect ‘mamma,’ if she knew into what strange hands her darling had fallen? Of course, my first duty to-morrow is to hunt up this mislaid uncle of little Josephine’s and restore her to him. But—Well, it’s my duty, and of course I shall do it.”

The great bed in the guest room was big enough, Josephine thought, to have held mamma herself, and even big Bridget without crowding. It was far softer than her own little white cot in the San Diegan cottage, and plunged in its great depths the small traveller instantly fell asleep. She did not hear Peter come in and lower the light, and knew nothing more, indeed, till morning. Then she roused with a confused feeling, not quite realizing where she was or what had happened to her. For a few moments she lay still, expecting[69] mamma’s or big Bridget’s face to appear beneath the silken curtains which draped the bed’s head; then she remembered everything, and that in a house without women she was bound to do all things for herself.

“But it’s dreadful dark everywhere. I guess I don’t like such thick curtains as Uncle Joe has. Mamma’s are thin white ones and it’s always sunshiny at home—’xcept when it isn’t. That’s only when the rains come, and that’s most always the nicest of all. Then we have a dear little fire in the grate, and mamma reads to me, and big Bridget bakes and cooks the best things. We write letters to papa, and mamma sings and plays, and—it’s just lovely! Never mind, Josephine. You’ll be back there soon’s papa gets well again, and Uncle Joe was sort of cryey round his eyes last night. Mamma said I was to be like his own little daughter to him and take care of him and never make him any trouble. So I will.”

There was no prouder child in that city that morning than the little stranger within its[70] gates. She prepared her bath without aid, brushed her hair and dressed herself entirely. It was true that her curls did not look much as they did after mamma’s loving fingers had handled them, and the less said about those on the back of her head the better. Nor were the buttons in the right places to match the buttonholes, and the result was that the little frock which had always been so tidy hung at a curious angle from its wearer’s shoulders.

But who’d mind a trifle like that, in a beginner?

Not Uncle Joe, who saw only the fair front of his visitor, as she ran down the hall to meet him, emerging from his own chamber. Indeed, he was not now in a mood to observe anything save himself, though he answered Josephine’s gay “Good morning” with another rather grimly spoken.

The child paused, astonished. There were no longer tears in his eyes, but he looked as if a “good cry” would be relief. His face was distorted with pain, and every time he put one of his feet to the floor he winced as if it hurt[71] him. He seemed as dim and glum as the day outside, and that was dreary beyond anything the little Californian had ever seen. The snow had fallen steadily all the night, and the avenue was almost impassable. A few milk-carts forced their way along, and a man in a gray uniform, with a leather bag over his shoulder, was wading up each flight of steps to the doorways above them and handing in the morning mail.

“Aren’t you well, Uncle Joe? Didn’t you rest well?” she inquired solicitously.

“No, I’ve got that wretched old gout again,” he snapped.

“What’s that?”

“It’s a horrible, useless, nerve-racking ‘misery’ in my foot. It’s being out in that storm yesterday, and this senseless heap of snow on the ground. March is supposed to be spring, but this beastly climate doesn’t know what spring means. Ugh!” he groaned.

“Doesn’t it?” she asked, amazed by this statement.

“Hum, child. There’s no need of your repeating[72] everything I say in another question. I’m always cross when I’m gouty. Don’t heed me. Just enjoy yourself the best you can, for I don’t see how I’m to hunt up your uncle for you in such weather.”

Josephine thought he was talking queerly, but said nothing; only followed him slowly to the breakfast room, which Peter had done his best to make cheerful.

Mr. Smith sat down at table and began to open the pile of letters which lay beside his plate. Then he unfolded his newspaper, looked at a few items, and sipped his coffee. He had forgotten Josephine, though she had not forgotten him, and sat waiting until such time as it should please him to ask the blessing.

For the sake of her patient yet eager face, Peter took an unheard-of liberty: he nudged his master’s shoulder.

“Hey? What? Peter!” angrily demanded Mr. Smith.

“Yes, suh. Certainly, suh. But I reckon little missy won’t eat withouten it.”

It was almost as disagreeable to the gentleman[73] to be reminded of his duty, and that, too, by a servant, as to suffer his present physical pangs. But he swallowed the lesson with the remainder of his coffee, and bowed his head, resolving that never again while that brown-eyed child sat opposite him should such a reminder be necessary.

As before, with the conclusion of the simple grace, Josephine’s tongue and appetite were released from guard, and she commented:

“This is an awful funny Baltimore, isn’t it?”

“I don’t know. Do you always state a thing and then ask it?” returned Uncle Joe, crisply.

“I ’xpect I do ask a heap of questions. Mamma has to correct me sometimes. But I can’t help it, can I? How shall I know things I don’t know if I don’t ask folks that do know, you know?”

“You’ll be a very knowing young person if you keep on,” said he.

“Oh! I want to be. I want to know every single thing there is in the whole world. Papa used to say there was a ‘why’ always, and I like to find out the ‘whys.’”

[74]“I believe you. Peter, another chop, please.”

“With your foot, Massa Joe?” remonstrated the butler.

“No. With my roll and fresh cup of coffee,” was the retort.

“Excuse me, Massa Joe, but you told me last time that next time I was to remember you ’bout the doctor saying ‘no meat with the gout.’”

“Doctors know little. I’m hungry. If I’ve got to suffer I might as well be hung for a sheep as a lamb. I’ve already eaten two chops. Another, Peter, and a juicy one.”

The order was obeyed, though the old negro knew that soon he would be reprimanded as much for yielding to his master’s whim as he had already been for opposing it.

“Doctor Mack knows everything,” said Josephine.

“Huh! Everybody belonging to you is perfect, I conclude,” said the host, with some sarcasm.

“I don’t like him, though. Not very well. He gives me medicine sometimes, though[75] mamma says I don’t need it. I’m glad he’s gone to eat those philopenas. Aren’t you?”

“I don’t care a rap where he goes,” answered Uncle Joe testily.

Josephine opened her eyes to their widest. This old man in the soiled green dressing-gown, unshaven, frowning and wincing in a horrible manner, was like another person to the handsome gentleman with whom she had dined overnight. He was not half so agreeable, and— Well, mamma often said that nobody in this world had a right to be “cross” and make themselves unpleasant to other people. She was sorry for poor Uncle Joe, and remembered that he had not had the advantage of mamma’s society and wisdom.

“Uncle Joe, you look just like one of them picture-men that was shut up in a tree trunk. You know. You showed them to me last night. I wish you wouldn’t make up such a face,” she observed.

Mr. Smith’s mouth flew open in sheer amazement, while Peter tossed his hands aloft and rolled his eyes till the whites alone were visible.[76] In all his service he had never heard anybody dare to speak so plainly to his master, whose temper was none of the mildest. He dreaded what would follow, and was more astonished than ever when it proved to be a quiet:

“Humph! Children and fools speak truth, ’tis said. You’re a sharp-eyed, unflattering little lady, Miss Josephine; but I’ll try to control my ugly visage for your benefit.”

The tone in which this was said, rather than the words themselves, was a reproof to the child, who immediately left her place, ran to her uncle’s side, and laid her hand pleadingly upon his arm.

“Please forgive me, poor Uncle Joe. I guess that was saucy. I—I didn’t think. That’s a way I have. I say things first, and think them afterward. I guess it isn’t a nice way. I’ll try to get over that. My! won’t that be fun? You trying not to make up faces, and I trying not to say wrong things. I’ll tell you. Have you got a little box anywhere?”

“Yes, I presume so. Go eat your breakfast, child. Why?”

[77]“’Cause. Did you know there was heathens?” she asked gravely.

“I’ve heard so. I’ve met a few.”

“You have? How delightful!” came the swift exclamation.

“I didn’t find it so. Why, I say?” he inquired.

“Each of us that forgot and broke over must put a penny, a cent, I mean, in the box. It must be shut tight, and the cover gum-mucilaged down. You must make a hole in the cover with your penknife, and when you screw up your face, just for nothing, you put a penny in. I’ll watch and tell you. Then I’ll put one in when I say wrong things. I’ve a lot of money in my satchel. Mamma and Doctor Mack each gave me some to buy things on the way. But there wasn’t anything to buy, and I can use it all, only for Rudanthy’s new head. Can we go buy that to-day, Uncle Joe?”

“No. Nobody knows when I’ll get out again, if this weather holds. The idea of a snowstorm like this in March. In March!” angrily.

[78]“Yes, suh,” responded Peter respectfully, since some reply seemed expected.

“Here, boy. Carry my mail to the library. Get a good heat on. Fetch that old soft shawl I put over my foot when it’s bad, and, for goodness sake, keep that child out of the way and contented, somehow.”

Josephine had gone to the window, pulled the draperies apart, and was looking out on a very different world from any she had ever seen. White was every object on which her eye rested, save the red fronts of the houses, and even these were festooned with snowy wreaths wherever such could find a resting place. The scene impressed and almost frightened her; but when, presently, it stopped snowing, and a boy ran out from a neighboring house, dragging a red sled through the drifts, her spirits rose. It had been one long, long week since she had exchanged a single word with any child, and this was an opportunity to be improved. She darted from the room, sped to the hall door, which stood ajar for Lafayette’s[79] convenience in clearing off the steps, and dashed outward.

Her feet sank deep into the cold, soft stuff, but she didn’t even notice that, as she cried, eagerly:

“Little boy! Oh, little boy! Come here quick! I want somebody to play with me.”

A moment’s pause of surprise, that a child should issue from “old Mr. Smith’s,” and the answer came cheerily back:

“Wish I could; but I’m going sledding.”

“I’ll go with you! I never went a-sledding in all my”—

The sentence was never finished, for somebody jerked her forcibly back within doors just as a great express wagon crawled to a pause before the entrance.

“My trunk! my trunk! My darling little blue trunk!”

“Massa Joe says for you to go right straight back to the library, missy. He says you done get the pneumony, cuttin’ up that way in the snow, and you not raised in it. He says not to let that boy in here. I—I’s sorry to disoblige any little lady what’s a-visitin’ of us, but”—

“It’s my trunk, Peter. Don’t you hear?”

“Yes, missy. But Lafayette, that’s his business, hauling luggage. I’se the butler, I is.”

Josephine retreated a few paces from the door. She had lived in the open air, but had never felt it pinch her nose as this did. Her feet, also, were cold, and growing wet from the[81] snow which was melting on them. But Peter was attending to that. He was wiping them carefully with his red handkerchief, and Josephine lifted first one, then the other, in silent obedience to his touch. But her interest was wholly in the trunk, which had now been deposited in the vestibule, and from which Lafayette was carefully removing all particles of snow before he carried it up over the carpeted stair.

Mr. Smith limped to the library door and looked out. He had meant to send word that the trunk should be retained at the railway station for the present, or until he should find out to whom Josephine had really been “consigned,” and asked, in vexation:

“Come already, has it? Humph! If it had been something I wanted in a hurry, they’d have taken their own time about delivering it. Said they couldn’t handle goods in a storm, and such nonsense. I don’t see, Peter, as it need be taken upstairs. Have it put in the storeroom, where it will be handier to get at when she leaves.”

[82]Both Peter and Josephine heard him with amazement.

“What is that, Uncle Joe? That ‘when I leave.’ Have I—have I been so—so saucy and forgetful that—that you can’t let me stay?”

“No, no, child. I merely meant— There, don’t look so distressed. You are here for the day, anyway, because none of us can go trudging about in such weather. I’ll telephone for— There. No matter. It’s right. It’s all right. Don’t, for goodness sake, cry. Anything, anything but that. Ugh! my foot. I must get out of this draught,” he almost yelled.

Josephine was very grave. She walked quietly to Uncle Joe’s side, and clasped the hand which did not hold a cane with both her own.

“It’s dreadful funny, seems to me. Aren’t we going to stay in this house all the time? I wish—I’m sorry I spoke about the box and the heatheny money. But if you don’t mind, I must, I must, get into my trunk. The key is in my satchel in my room. Mamma put it there with the clean clothes I wore last night.[83] She said they would last till the trunk came; but that as soon as ever it did I must open it and take out a little box was in it for you. The very, very moment. I must mind my mamma, mustn’t I?”

“Yes, child, I suppose so,” he slowly returned.

Mr. Smith was now in his reclining chair, with his inflamed foot stretched out in momentary comfort. He spoke gently, rather sadly, in fact, as he added:

“My child, you may open your trunk. I will never counsel you to do anything against your mother’s wishes. She seems to be a sensible woman. But there has been a mistake which I cannot understand. I am Joseph Smith. I have lived in this house for many years, and it is the street and number which is written on the tag you showed me. Do you understand me, so far?”

“Course. Why not?”

“Very well. I’m sorry to tell you that I have no twin brother, no ‘sister Helen,’ and no niece anywhere in this world. I have many[84] cousins whom I distrust, and who don’t like me because I happen to be richer than they. That’s why I live here alone, with my colored ‘boys.’ In short, though I am Joseph Smith, of number 1000 Bismarck Avenue, I am not this same Joseph Smith to whom your mamma sent you. To-morrow we will try to find this other Joseph Smith, your mislaid uncle. Even to-day I will send for somebody who will search for him in my stead. Until he is found you will be safe with me, and I shall be very happy to have you for my guest. Do you still understand? Can you follow what I say?”

“Course,” she instantly responded.

But after this brief reply Josephine dropped down upon the rug and gazed so long and so silently into the fire that her host was impelled to put an end to her reflections by asking:

“Well, little girl, of what are you thinking?”

“How nice it would be to have two Uncle Joes.”

“Thank you. That’s quite complimentary to me. But I’m afraid that the other one might[85] prove much dearer than I. Then I should be jealous,” he returned, smiling a little.

Josephine looked up brightly.

“I know what that means. I had a kitten, Spot, and a dog, Keno; and whenever I petted Spot Keno would put his tail between his legs and go off under the sofa and look just—mis’able. Mamma said it was jealousy made him do it. Would you go off under a table if the other Uncle Joe got petted? Oh! I mean—you know. Would you?”

Though this was not so very lucid, Mr. Smith appeared to comprehend her meaning. Just then, too, a severe twinge made him contort his features and utter a groan.