Title: Søren Hjorth: Inventor of the Dynamo-electric Principle

Author: Sigurd Smith

Translator: F. Sodemann

Release date: August 11, 2021 [eBook #66046]

Language: English

Credits: Charlene Taylor, Craig Kirkwood, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

SØREN HJORTH

INVENTOR OF THE

DYNAMO-ELECTRIC PRINCIPLE

BY

SIGURD SMITH

C. E., M. I. F.

PUBLISHED BY »ELEKTROTEKNISK FORENING« AT THE

EXPENSE OF THE CARLSBERG FOUNDATION

KØBENHAVN

Printed by J. Jorgensen & Co. (M. A. Hannover)

1912

This pamphlet is published simultaneously

in English and in Danish,

and is distributed among interested

institutions all over the world.

Translated by F. SODEMANN, C. E., M. I. F.

Handsworth, Birmingham,

Feb. 6th, 1851.

... After this wonderful force

has been discovered by Your Excellency,

it has been my pride and interest that

also the utilization thereof should be

originated by a Dane....

(Fragment of a letter from Hjorth

to H. C. Ørsted.)

Since the Life and Works of Søren Hjorth, the Dane was published in the Danish technical journal the »Elektroteknikeren«, in 1907, a statement concerning Hjorth’s rights of priority to the invention of the dynamo-electric principle has been sent to the leading foreign technical periodicals, viz. »Elektrotechnische Zeitschrift«, »L’éclairage électrique«, and »Electrical Engineering«. As this statement still stands uncontradicted, it seems reasonable to consider Hjorth’s priority rights to this principle to be generally acknowledged, even in the great centres of civilization. Therefore I highly appreciated the courtesy of Mr. Hjorth’s heirs, after the death of his step-daughter, Miss D. Ancker, in the autumn of 1908, in offering me an opportunity to peruse the large collection of letters, rough-copies, drawings, and sketch-books left by Hjorth, which threw new light on his interesting life and work. Where it was previously necessary to resort to guesswork alone, we are now able to base our statements on established facts and to follow Hjorth’s train of ideas almost from his first, to his last invention, and to see where he has right and where he failed.

In the following pages, an account will be given of the results of these recent researches in connection with what was previously known about Hjorth.

Charlottenlund 1911.

Sigurd Smith.

[1]

SØREN HJORTH.

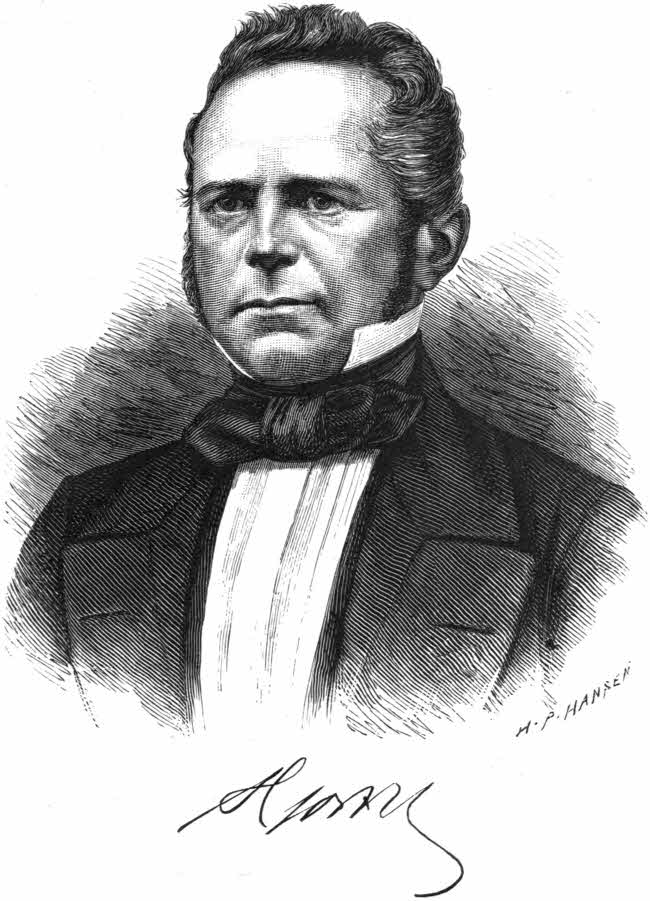

Søren Hjorth was born on the 13th of October, 1801. He spent his childhood at Vesterbygaard, an estate rented by his father, Jens Hjorth, in Jordløse Parish, north of Tissø. His mother’s maiden name was Margrethe Lassen. Of their numerous children only two, besides Søren, survived childhood.

The parents became early aware that their son possessed great mechanical genius. He received his first education from the parish school-master. After Hjorth was confirmed, his father leased the beautiful estate Dragsholm, in Odsherred County, where he remained for many years, and after the death of his first wife, he married baroness Zytphen-Adeler.

Though he did not have an opportunity of learning much in his childhood, Hjorth succeeded in his youth in passing an examination which admitted him to the Bar. Later on he became the steward of Bonderup Estate, near Korsør, but in this position he did not feel satisfied, and in 1828 he became a volunteer in the State Treasury, in Copenhagen. In 1836, he advanced to the position of Clerk of the Exchequer and secretary.[2] Although Hjorth’s occupation, during the last 30 years of his life, was mainly that of a civil engineer, he always continued to be addressed as Secretary Hjorth, and by this title he is still remembered by some of his surviving contemporaries.

Hjorth’s interests while at the Treasury were not concentrated solely on his work there. Mechanical problems always fascinated him. It is told that, during this period, he made all kinds of experiments at Dragsholm, and, among other things, he constructed a thrashing-machine. In 1832 he constructed a rotary steam-engine, which was made by Schiødt, a mechanic residing at St. Annae Plads, and, upon Hjorth’s application, it was bought by the King for 500 rixdollars in notes. The King donated it to the newly founded Polytechnic Institute, this being the place where it might best be utilized and »where this original domestic invention might most suitably be placed«. The same year, Hjorth described in »Ursin’s Magazines for Artists and Artisans« a steam-car, invented by him and adapted to be propelled by means of the rotary steam-engine. So Hjorth once more made a petition to the Government for a subvention of 2000 to 2500 rixdollars to assist in the practical manufacture of this car. The decision on this application was postponed, however, at the suggestion of Professors Ørsted, Zeiss and Forchhammer, because Hjorth had not yet finished the installation of the boiler for the first steam-engine at the Polytechnic Institute. Hjorth did not succeed in making the engine work, as it was not made with sufficient accuracy. The sum for which the car was to be made, was never granted, as petitioned for, although Hjorth had given up using his rotary engine for it; and the car itself was probably never built.

[3]

At that time, the use of steam-cars on the country roads attracted great attention in England, and many different constructions appeared. In 1834 Hjorth, aided by subventions from the »Rejersen Foundation« and the Government, went to England, in order to acquaint himself with the use of these steam-cars on high-roads and railroads. During these years he very actively investigated the use of steam-power, especially as a means of propulsion for vehicles and ships. With admirable interest and diligence he studied the steam propelled road-carriage, and for a long time he considered that to be the future means of conveyance. Although he did not succeed in getting his own steam-carriage put to practical use, he made many experiments on a steam car, and I am told by one of his passengers that on the level streets of Copenhagen and Frederiksberg all went very well, but the carriage could not climb Valby hill.

During these years, Hjorth also attended the lectures at the Polytechnic Institute, and he was especially interested in Ørsted’s lectures on the physics of the globe, and on electricity and magnetism.

Notwithstanding his unsuccessful experiments with the rotary steam-engine, Professors Ørsted, Zeiss and Forchhammer had to give him a warm recommendation, when he made a petition to the Ministry in order to get his expenses refunded by the Government. They mentioned his indefatigable zeal, his great diligence, and the considerable expense borne by him in the pursuit of his researches. The numerous and expensive experiments absorbed all the money Hjorth could procure: not only his salary was spent, but also such funds as he was able to raise among his friends.

[4]

In 1839 Hjorth made a journey to England, France and Belgium. By that time, he seems to have come to the conclusion that steam-carriages running on rails, are preferable to steam-carriages running on the high-road, at any rate he mainly studied locomotives and railroading during this journey.

After his return to Denmark, he spent some years as manager of Marschall’s piano factory, though still at work with his railroad schemes, and in 1840 he happened to find a man named Schram, a book-keeper, who shared his interests and was able to assist him in the realisation of his ideas. In 1840, these two men published a detailed calculation of the probable revenues and expenses of a railroad between Copenhagen and Roskilde. This project, however, did not arouse any interest, and people were mostly inclined to smile at the idea, and it appeared impossible to induce competent men to take, any interest in the scheme, much less to invest money therein.

Then, in 1841, they applied to the young »Industrial Association« which body referred the case to its special committee of commerce. Even this committee did not seem much inclined to listen to Hjorth’s and Schram’s proposition, but their undefatigable energy finally succeeded in persuading the committee of commerce to convoke a large meeting to be held on the 24th of March. Here it was decided to make an application to the Government for the surveying of the proposed railroad line and, to the surprise of many, the petition was granted. Hjorth, possessing distinctive agitatory faculties, showed great activity, delivering lectures and exhibiting models, and[5] tried thereby to excite interest in his schemes. His contemporaries describe him as a sociable man of a winning and lovable disposition and possessing a certain persuasive power. He was well liked by his friends as well as by his many casual acquaintances. In 1841 both Hjorth and Schram were elected members of the Board of Representatives of the Industrial Association, and from 1841 to 1843 Hjorth was the vice-president of the association. Now there began to be some sympathy for their cause, and the Board of Representatives of the Industrial Association showed a willingness to follow the sub-committee elected, consisting of the two motionists and Lector, (later Professor) Wilkens of the Polytechnic Institute. The strenuous efforts of this sub-committee resulted in the Industrial Association submitting, in January 1843, an application for a franchise to form a stock-company for the purpose of building a railroad from Copenhagen, by way of Roskilde, to a sea-port on the western coast of Sealand. This franchise, was granted, for a period of 100 years, and on the 16th of April 1844 the Industrial Association issued a public invitation to take stock in a company whose stock capital was to be 1 1/2 million rixdollars, a very considerable sum for those times. As early as in the beginning of May, most of the stock was taken—mainly in Hamburg. While the confidence in a scheme of this kind was but slight in Denmark, the speculation in railroad stocks was nearly culminating at the stock-exchanges of Germany and England; as a matter of fact, it became near being a swindle. The Sealand Railroad Company was founded on the 2nd of July 1844, and Hjorth became its first technical director, while Schram became its first general manager. The Industrial Association received 15000 rixdollars[6] for the franchise, and from this sum it paid 3000 to Hjorth and Schram.

In 1843, Hjorth was unanimously elected president of the Industrial Association. In 1845, he had to resign this office, but as it appeared very difficult to concentrate the votes in favour of a new president and vice-president, »Secretary Hjorth, to meet the general demand, accepted the vice-presidency«, which office he then held for a year.

In the meantime, the railroad company had finished the construction of its first piece of road, from Copenhagen to Roskilde, and this was opened for traffic on the 27th of June 1847, some days before the time limit fixed. Even at that time it was decided, owing to Hjorth’s influence, to extend the road to Korsør. The cause of the delay in commencing this work was the railroad crisis which had just broken out in Germany and England, making it impossible to obtain money for the construction of railroads. This road, therefore, was not constructed until the government, in 1852, guaranteed an interest of 4% on the capital invested.

Hjorth retained his position for about 4 years, and concerning this period he writes: »All the great difficulties and obstacles to be surmounted during the construction of the road influenced my health to such a degree that I broke down and was forced to abandon my position as technical director of the railroad before the expiration of my term of office, in order that I might take a water-cure at Klampenborg«. After he had, to some extent, regained his health there, and another board of directors had been elected, he made a travel to England which turned out to be of such great importance that we will describe it more fully in the following.

[7]

After Faraday, in 1831, had discovered how an electric current might be produced by means of a magnet, many people busied themselves by trying to put this invention into practical use, and numerous attempts were made to construct electro-magnetic and magneto-electric machines for useful purposes.

No wonder that these efforts attracted Hjorth’s attention, and, as early as 1842, he had drafted an electro-magnetic machine, consisting of a stationary circle of magnets, whose poles were directed against the poles of a moveable circle of magnets. In 1843 this sketch was deposited with the Royal Scientific Society, but the sketch itself, as well as the explanation belonging to it, are very incomplete.

In the month of April, 1848, Hjorth made a petition to the government for a subvention of 200 rixdollars, in order that he might go to England to get an electro-magnetic machine[1] designed by him, made there. Hjorth had noticed that, in a piece of iron encircled by an electric current, the magnetism only to a certain extent would increase, with the strength of current, there being a point of saturation for the iron. When this point has been reached, it will be of no use to increase the intensity of the current, since the magnetism will not increase any further. On the basis of this observation, Hjorth had constructed his machine, but he had confided the[8] details thereof only to Professors Ørsted and Forchhammer. In the report on Hjorth’s petition made by these two professors to the Board of Trade, they, curiously enough, take exception to the above-mentioned observation by Hjorth, while its correctness will now be acknowledged by any electrician. These professors, however, advised that Hjorth’s petition should be granted, using this liberal argument, worded by Ørsted: »Regarding the petitioner’s new electro-magnetic machine, we must state that we find it quite ingenious, and although we are not convinced that it will produce remarkable effects, we should consider it useful to have a working model executed. Having during so many years worked for this case, the petitioner might perhaps, by the execution of such a model, be enabled to make some further invention, which would bring him nearer to the goal. Indefatigable zeal has often accomplished its purpose, where science had to declare the means at first used, to be entirely inadequate, but where, by continued work, entirely different means, previously unknown to the inventor, were found. Inasmuch as the sum of 200 rixdollars asked for is so small, we find it advisable to grant the subvention. Still we cannot refrain from remarking that the petitioner’s machine may just as well be made here as at any other place«.

Thus the discoverer of electro-magnetism cleared the road which was to lead to the most beautiful application of electro-magnetism, that application which, before all others, has been of radically reforming importance during the last half century, thereby throwing double splendor on Ørsted’s name.

Soon after his arrival at London, in the summer of 1848, through a firm which he knew from an earlier[9] period of his life, Hjorth made the acquaintance of a nephew of Bramah, the renowned mechanician and inventor of the Bramah-lock. Hjorth’s invention was then laid before a friend of Bramah’s, a civil engineer named Gregory, who had made the study of magnetism his specialty. Gregory at once persuaded Bramah to bear the expense of making a machine, and of securing patents in England and several other countries, on condition that the expected profits should be divided between him and Hjorth. Later on, B. Taylor and Normann Innis were taken in as partners, paying together £1000, and then Charles Stovin (£600) and Robert Broad, of the Henley Iron Works (£500). Two machines were now made, according to Hjorth’s directions, by the firm of Robinson & Sons, Pimlico, London. One of these is shown in Fig. 1, and is apparently quite an ingenious imitation of the steam-engines of those days. C is a movable, A a fixed electro-magnet. Their peculiar shape, involving several conical pins fitting into corresponding cavities, was thought to be advantageous for the distribution of the[10] effect of the magnetic force over a longer stroke. The »piston« C, reciprocating up and down, drives a crank shaft having two opposite cranks. To either of the cranks there is a corresponding group of magnets. An eccentric fixed on the shaft, moves a »slide valve«, alternately closing the circuit of one or the other of the two groups of magnets. When the one piston is at its lowest position, the circuit of the other group of magnets is closed, and its piston is attracted, until it reaches its bottom position; then the current is shifted, and the other piston attracted, etc. In order to avoid the formation of sparks at the circuit breaker, an ingenious device was provided, closing the current of one group of magnets, immediately before that of the other one was broken. The first machine was made with a 4 inch stroke, the next one with 13 1/2 inch stroke. The magnetic attraction per square inch of the piston, had about the same magnitude as the pressure per square inch in the low pressure steam-engines of those days. The patent application was filed in London as early as in October 1848, and it was granted on the 26th of April 1849[2]. On the 21st of September, the same year, Hjorth obtained a fifteen year monopoly in the kingdom of Denmark, to manufacture machines, utilizing electro-magnetism as motive power in the above described manner.

The larger of the machines here referred to was shown in action to several technical experts, and created considerable sensation, especially on account of the great length of stroke attained—13 1/2 inches—and the uniform motion of the machine. The machine is mentioned in »Mining Journal«, for the 5th of May, and 16th of[11] June 1849, and an extract of these articles is published in the »Flyveposten« for the 3rd of July the same year.

Hjorth was invited to show the machine at the Royal Society, and at the annual meeting of the Society of Civil Engineers, of which he was a member. It was exhibited at the Universal Exhibition in London, in 1851. In the catalogue it was highly commended, and it received the only prize-medal awarded to electrical machines.

There was, however, one essential obstacle to the practical use of this machine, namely the lack of means for cheaply producing electricity in the quantities required by the electromotor. Wet batteries were expensive to use, and if the machine were to become useful in practice, a powerful »dry battery« would be a necessity. Most of the then known machines producing electricity, were fitted with permanent steel magnets, and as the point of magnetic saturation of steel is low, these machines were unable to produce any considerable quantities of electric energy. Hjorth therefore imposed upon himself the task of building a dry battery. His sketch-book from 1851 is full of new schemes for such batteries and improvements on those already existing (Woolrich’s, Elkington’s and Paine’s). From this it appears, among other things, that he was fully aware that, when the spools suddenly entered or left the field, difficulties would arise in the commutation, and he therefore improved the machine by bending the field magnets, obtaining thereby a gradually increasing and decreasing field, the same thing which is, nowadays, attained by using pointed or obliquely cut pole-shoes.—It would be very tempting to study more closely these sketch-books with their neatly colored drawings, showing[12] how many different ideas have been fostered by him, before the actual production of the first dynamo, in 1854. Most of the descriptions and notes have been written in the English language, which he used almost as readily as his native tongue. On the 1st of May, 1851, Hjorth writes in his sketch-book, beside a sketch of a machine having copper discs for armature conductors and cast iron electro-magnets: »By passing the current on the said way round the Electromagnets, these will of course be excited in proportion to the strength of the same, and the more they are excited, the more will the discs be influenced by the magnets, a mutual action thus taking place«.

So it appears that Hjorth, as early as on the 1st of May 1851, with perfect clearness, has pronounced the dynamo-electric principle.

Under the date of June 24th, 1851, we find sketched out another beautiful idea for the construction of a dynamo. It must be regretted that this machine has not been executed, as it would certainly have proved superior to his dynamo of 1855, which has many points in common with this project. Fig. 2 shows a reproduction of this page of the sketch-book. There is no descriptive text to this sketch, only at one side of the drawing, these very significant words are written: »Magneto-Electric arrangement with mutual action«. All the six powerful held magnets are of cast iron, and they are wound so as to be magnetized by the current, produced by the dynamo itself[3].

[13]

In November, 1851, Hjorth returned to Copenhagen, and here he continued what he had commenced in England. In May, 1852, he deposited with the »Society of Sciences« some papers, signed by Professors Scharling and Forchhammer in December, 1851. These papers contain two descriptions, written in English, and two drawings of »dry batteries«. These consist of 3 or 4 circular rows of vertical steel rod magnets, placed one above the other, and disposed round a vertical shaft, carrying 2 or 3 circular rows of armatures. Each armature consists of a piece of soft iron, and is wound with a strip of copper, in a special manner. There are, in each row, as many armatures as magnets. The hollow shaft, as well as the magnets, which are fitted with shoes of soft iron, are wound, and encircled by the current produced in the armatures. With regard to the magnetic arrangement, this machine comes very near to the one patented by Brett in 1848, and it will be noticed that it cannot be said to be constructed according to the dynamo principle, as the »mutual« action plays no important part, the magnets being permanent steel magnets, hardly adapted to receive much extra magnetism by the current of the machine. Hjorth points out, as the novel feature of these machines, the division of the steel magnets into many small ones, with an armature corresponding to each magnet. Hereby he claims, for the same weight of the steel magnets, a larger capacity of the machine than if he had used fewer, but larger[14] steel magnets[4]. The machine is fitted with a commutator for direct current.—In March, 1854, the sketch-book contains another sketch of a dynamo, with clear indication of the dynamo principle, approximately as it was patented on the 14th of October the same year[5]. This sketch is reproduced in Fig. 3. The machine has two permanent cast iron magnets and two electro-magnets. The armature cores are fitted with oblique pole-shoes. The description is very brief and contains the same as the patent specification.

In 1853 Hjorth negotiated with a certain Dr. Watson, who had constructed a »dry battery« by means of which Hjorth had meant to drive his electro-magnetic machine. The object of their negotiations was to buy out Hjorth’s above-named partners, and to form a new company for the purpose of exploiting the above-mentioned two machines. The partnership, however, was not realized, and in spring of 1854, Hjorth himself commenced to have a 3 HP battery built in Copenhagen. The machine was fitted with cast iron magnets, and in all probability it was similar to the project of March 1854, and agreed with the patent of October, the same year.

This patent specification reads as follows: »The main feature of this battery consists in applying one, two, or several permanent magnets A, of cast iron, and shaped as shewn in the drawing (Figs. 4 and 5), in connection with an equal number or more electro-magnets B, shaped as indicated[15] in drawing, in such a manner that the currents induced in the coils of the revolving armatures are allowed to pass round the electro-magnets; consequently, the more the electro-magnets are excited in the said manner, the more will the armatures C be excited, and the more electricity of course induced in the respective coilings; and while a mutual and accelerating force is produced in this manner between the electro-magnets and the armatures, an additional or secondary current is at the same time induced in the coiling of the electro-magnets by the motion of the armatures, the said current flowing in the same direction as that of the primary current, after having passed the commutator. The direction of the[16] current induced in the coils of the armatures will, of course, be reversed according to the change of the respective polarities, and the commutator D is therefore applied for the purpose of causing the current to flow constantly in one direction«. Then follows a description of the commutator of the dynamo. Finally the pole-shoes, or false poles, provided on the magnets as well as on the armatures, are mentioned. He points out that the false poles have on the side of attraction, a long straight edge, as distant from the centre as possible, while on the side of separation, either one has a sharp point, nearer to the axis of revolution, »all with a view to avoid reactionary currents, and at the same time to facilitate the motion of the armature«. »While steel magnets also may be applied instead of cast-iron magnets, the permanent magnets may be coiled like the electro-magnets, which also will serve to make them more permanent«.

From the above-named sketch-book notations, and the patent specification, it will be seen that Hjorth, during the years 1851-54, has repeatedly pronounced the dynamo principle with perfect clearness, and that he has utilized it in several projects.

It is worth noting that Hjorth’s so-called »permanent« magnets are of cast iron. This shows that Hjorth has known of remanence, or permanence. He has known that cast iron always possesses some slight magnetism, either induced by the earth magnetism or as a remnant—remnant magnetism—left over from its being magnetized in a coil. It has heretofore been assumed that Siemens was the first to call attention to this property of iron, in his paper in the transactions of the Royal Society, of the 14th of February, 1867.—Thus Hjorth used this[17] weak remanent magnetism in the large cast iron magnets to produce the initial current in the dynamo, which then excites itself.—At the end of the patent specification, Hjorth points out that the remanent magnets may also be coiled (compare Fig. 2), and thereby he comes closer to the later dynamo constructions.

Hjorth is quite right, according to the patent specification, in giving the pole-shoes such a shape that the armature is gradually demagnetized, and in stating that the object of this is thereby to avoid reactionary currents, and consequently the formation of sparks; while he is mistaken in believing to be able to facilitate the motion of the armature by giving the pole-shoes a certain special shape, because in that case, the machine would be a perpetuum mobile.

Together with the above-mentioned dynamo, Hjorth had an electromotor made in Copenhagen, essentially similar to the one exhibited in 1851. When in the autumn 1854 the machines were finished, Hjorth was called back to England, in order to continue the work on his inventions. It is not known whether the machines were sent to England or not; at any rate they aroused some interest there, and he had a new and larger dynamo built by Messrs Malcolm & Campbell; of Liverpool, 7 India Buildings, at the expense of Malcolm and others. This machine was patented in 1855[6], and is shown in Fig. 6, which is reproduced from a photograph. Here, too, the dynamo principle has been followed, but each electro-magnet is composed of one solid and one tubular electro-magnet, the latter enclosing the former, the two together forming a so-called »cup magnet«, a construction which[18] has also been used by later inventors. Hjorth describes the action of the battery as follows: »The permanent magnets acting on the armatures, brought in succession between their poles, induce a current in the coils of the armatures, which current, after having been caused by the commutator to flow in one direction, passes round the electro-magnets, charging the same and acting on the armatures. By the mutual action between the electro-magnets and the armatures, an accelerating force is obtained, which in the result produces electricity greater in quantity and intensity than has heretofore been obtained by any similar means.« At the same time, Hjorth allowed the dynamo patent of 1854 to lapse, it being merely a provisional patent.

Together with the dynamo patent of 1854, Hjorth secured a provisional patent on an improved electromotor[7], and together with the dynamo patent of 1855, he obtained the complete patent on the above mentioned electromotor, as well as on another construction thereof[8]. The former consisted of hollow, horizontal electro-magnets (cylinders), being of a special shape inside, adapting them to give to an electro-magnetic piston, reciprocating within them, a long and steady stroke. By means of a crank, the stroke was transformed into a rotary motion. The other electro-motor consisted of wheels, with protruding teeth, which were set in rotary motion by the teeth being attracted into hollow electro-magnets.

In May, 1856, Hjorth returned from England, disappointed. It will be noted that through the electro-motor Hjorth was led to occupy himself with the dynamo machine.[19] The dynamo was built in order to produce motive power for the motor. All the time he was working on these two inventions, it was his firm belief that if he could make the dynamo drive the electro-motor, he would be able to attain a substantial saving in power, get much more power out of the electro-motor than was consumed in driving the dynamo. The machines would, as it were, run automatically. He could not understand, why Dr. Watson was sceptical with regard to this manner of battery action. He intended to install his machines in ships and locomotives, which would then be propelled with a minimum consumption of power. In short, the combination of dynamo and electro-motor imagined by Hjorth was to be a perpetuum mobile. It has certainly been the great disappointment of his journey to England, that this scheme failed.

On reading about this mistake, one is inclined to base the judgment of Hjorth upon assumptions belonging to the present time. But this would be a great injustice to him. The axiom that the quantity of energy in nature is unalterable, and consequently a perpetuum mobile an impossibility, has, as it were, been imbued by our own generation with the mother’s milk. Not so with Hjorth. Not until the forties of the last century, did Mayer, Joule and Colding, the City Engineer of Copenhagen, set forth their theories about the permanency of energy, and about the convertibility of heat into mechanical activity, and of the latter into heat again. These theories, however, were very slowly accepted, even by scientists. It is, therefore, no wonder that a man like Hjorth, having no special scientific training, could not easily digest the new theory and Hjorth did not have any instinctive sensation of having entered upon a hopeless and impossible[20] track. On the contrary, he imagined the new wonderful form of energy to conceal unestimable possibilities which he had only to wrest from nature.

Though Hjorth was thus ship-wrecked on his favourite idea, he nevertheless discovered new land, fertile for coming generations. His intrepid zeal guided him, as Ørsted had anticipated, in spite of his lack of scientific education, on to the road leading to the splendid results of this day.

None of Hjorth’s original partners participated in the manufacture of his latest machines, and possibly this was due to his above-mentioned erroneous idea. Only one of his English friends, Wm. Macredie, of Melbourne, maintained his attachment to Hjorth and his confidence in him to the last. He was always very interested in Hjorth’s schemes, and, besides, he shared his religious creed.

Hjorth was very anxious as to his future. When he returned from England, he stood quite destitute and felt depressed by poverty. His health was not of the best, and his formerly so neat hand-writing had become unsteady. He received, shortly after his return, a communication from his English partners that they wished to have the dynamo patented in Denmark and France, which showed that they had faith in this machine, but nevertheless these were hard times for Hjorth.

The dynamo remained for some time with Malcolm, in Liverpool, and negotiations for its sale were several times entered into, but were without results. It was tested on several occasions, but these tests proved that it could not yield as much as might be expected from its size. The uncoiled magnets, which were originally of cast iron, were replaced by more powerful steel magnets.[21] Upon the whole, this dynamo had a rather eventful existence, for first every other magnet pole was removed (see Fig. 6), and then it was proposed to rewind the magnets. In May, 1857, it was donated to the Polytechnic Institute, Regent Street, in London. Among the papers left by Hjorth, there are a daguerreotype and a photograph of this machine, (from which the accompanying Fig. 6 is reproduced).

Notwithstanding a thorough search of the London museums, it has been impossible to trace this machine, which is said to have been seen in London during the nineties.

Hjorth was now compelled to find a new means of earning his livelihood, and to make new connections. In 1857, he became the representative of Cyclop’s Steel Manufactory, Charles Cammell, of Sheffield, and in 1859, he applied for and obtained a licence as a translator of English in Copenhagen. Finally he had a kind of engineering and patent office, assisting strangers in obtaining monopolies, and doing work for new railroads, bridges etc. In the beginning of the sixties he caused a research to be made concerning the use of coals from Hornholm and Silkeborg, and the use of peat for briquettes. In April, 1860, he applied to the government for a position, enabling him to work for the building of new railroads in Denmark, and at the same time he referred to his previous merits in that direction. As he had not, within a year thereafter, received any position, he made a petition for a yearly pension, in case such a position could not be given to him. As »the idea of building the Sealand railroad, as well as the general location of this road, is mainly due to Secretary Hjorth ... and further more, no small share in the completion of the undertaking[22] is due to him«, it was proposed, on the budget for 1861-62, to grant a pension to Hjorth. That year and the following ones, until his death, he received 500 rixdollars.

During these years, Hjorth lived at 10 Nørrebrogade. In 1845, he married Vilhelmine Ancker, née Hansen (born on the 27th of March, 1805), the widow of the farmer Diderick Ancker, of »Lille Egede«, and thereby he became the step-father of two daughters. This marriage was childless.

This carefully dressed little man[9] in top-hat and high-heeled shoes, was well known, and very well liked in many circles. He was always amiable and willing to help, and it is known that he has, at great personal sacrifice, assisted young artisans who were in hard luck. In society he attracted attention by his power of fascination and by his universal knowledge. On Sundays he was regularly seen directing his steps to St. John’s church, where, for many years, he was a member of Rev. Frimodt’s congregation.

During the period of depression above described, Hjorth could naturally not very well afford to occupy himself with experiments, nor had he much time. Still, in 1857, he secured permission to undertake, at the navy yard, some experiments concerning the carrying capacity of a magnet at varying distances between the pole and the armature, and at the same time he sketched out the construction of an electro-motor, especially well adapted to utilize the magnetic attraction. This electro-motor was built in Copenhagen with funds granted by the »Classenske Fideicommis«. When it was finished,[23] Hjorth applied for the money needed to make it double acting.

In autumn 1860, Hjorth was in Paris, and there he worked for his electrical inventions.

In 1866, Wilde published his machine, in which the current needed to magnetize the electro-magnets was produced by a permanent magnet. This is exactly the principle, underlying the dynamos built by Hjorth in 1854 and 1855. Hjorth’s good friend, Wm. Macredie, Melbourne, sent Hjorth a clipping from an English periodical mentioning Wilde’s machine, and called his attention to the identity.

It is to be regretted that Hjorth’s answer is not known, as his copy-book for 1866 has been lost.

Considering the data at hand when Hjorth’s biography was published in 1907, one might be inclined to believe that Hjorth had invented the dynamo principle and then dropped it at once, going back to steel magnets. It is, however, clearly evidenced, by the papers left by Hjorth, that this has not been the case, but that Hjorth has used the dynamo principle, in various, more or less pure, forms, in practically all his projects from 1851 to 1870.

As previously mentioned, Hjorth had been disappointed in his attempts to produce energy through an electrical transmission of power, but this did not cause him to relinquish the idea of producing energy by electric means. He took this up again in a new form in his old age. In order to have this idea carried out in practice, Hjorth had a machine built, a description and drawing of which is to be found in a pamphlet published later on in French and Danish. From this it appears that the machine was not originally built according to the dynamo principle. Hjorth found no advantage in using the expensive[24] electro-magnets, as it was his main object to prove that, by his special arrangement of armatures and magnets, he could reduce the power required to produce a certain amount of electrical energy. The machine, in its manner of construction, reminds one to some extent, of Hjorth’s project of 1851. Two or three rings, or wheels, of armature coils A (see Fig. 7) revolve between three or four circular rows of magnets M. This decreased consumption of power was to be attained by offsetting the armature wheels somewhat relatively to one another, for instance so that when one armature of the topmost wheel was opposite one magnet pole, an armature of the next armature wheel would be spaced one quarter of a pole distance from a pole, and an armature of the lowest wheel would be one half pole distance from a pole. As it is well known, this idea is entirely erroneous, it being contrary to the axiom of the constancy of energy.

The machine was built into a casing, and was sent to the Paris exhibition of 1867. Hjorth was always very careful not to give any information about his inventions to anybody. At the end of April, he went to Paris himself. The machine had suffered some injury on the journey, and had to be repaired in Paris, and therefore[25] it made its appearance rather late. Still he succeeded in having it submitted to the judgment of the jury, and a test of electrolytic deposition was made, which proved entirely successful.

In Paris he met a certain business-man who, later on, requested to enter into partnership with Hjorth. This man was an adventurer, whose ambition was to become a Knight of Danebrog. It is only to be regretted that this person obtained so great a power over Hjorth, and understood how to deceive him. The previously mentioned pamphlet, edited by the partner, and named »Batterie magnéto-électrique de Søren Hjorth«, is a document of the poorest kind.

Through his partner, Hjorth was introduced to various electricians and men of science, among others the renowned Samuel B. Morse, who recommended Hjorth’s machine, but took exception to his idea concerning the production of energy.

The electrician who repaired Hjorth’s machine, introduced him to the president of the French Société d’Encouragement, who had proposed a competition for electrical machines, and had offered a prize of 3000 fr. for a machine, complying with the conditions given. Hjorth’s machine was sent to the society, but he did not succeed in obtaining the prize, which was awarded to the subsequently so famous »Alliance« machine. On the 7th of July, Hjorth, probably prompted by his partner, obtained an audience of Emperor Napoleon III. After he had demonstrated his invention, and shown the letter from Professor Morse, the Emperor asked him what he could do for him, and Hjorth answered that his highest desire was to have a larger machine built, and he requested the Emperor’s protection and assistance, in order to accomplish[26] this. The Emperor ordered an examination of the machine to be made. The well-known Professor Jamin was retained as an expert, and Hjorth demonstrated the machine before him. On the following day it was examined, in the presence of Hjorth and his partner, by Jamin and other men of science. They subsequently had the machine sent to the exposition, where they measured the voltage and intensity of current, and expressed their satisfaction, as to the results attained. Nevertheless Hjorth was disappointed to receive, the next day, through the representative of the Emperor, General Favé, a communication that the subvention applied for could not be granted.

At the exposition, a great sensation was created by a dynamo exhibited by Ladd. This machine had two electro-magnets and two armatures, the current being directed from the smaller armature round the electro-magnets and taken from the larger armature to the exterior circuit, lights for instance. Thus the machine was evidently built according to the dynamo principle.

In order to claim his right of priority to this principle, Hjorth went to the prominent authority on physics, Count Th. du Moncel, who later on became the editor of »La lumière électrique«. As Hjorth himself did not know French, the interview probably took place through his partner. About this, Moncel writes in the above mentioned periodical, in 1883, that Hjorth’s representative was not very conversant with electrical matters; therefore he was unable to express himself clearly, and consequently Hjorth’s rights of priority were not acknowledged.

Having received the Emperor’s refusal, Hjorth went home, broken down by illness and disappointments.

[27]

In 1868-69 Hjorth, due to the interest taken in his case by the manufacturer Mr. Kähler, succeeded in having a small machine built in this gentleman’s shop in Korsør. At the same time, a larger machine was made in Copenhagen, the necessary funds being contributed by several country gentlemen and merchants interested in the case. Finally, in December, 1868, a body of prominent men addressed the government, petitioning a subvention of 15,000 rixdollars to be given to Hjorth, in order to enable him to build a new and larger machine. As the Ministry was not inclined to grant a sum of this size, it proposed to grant 1000 rixdollars, in order to have the existing machines examined by Professor Hummel and other experts. This proposition was accepted by Hjorth, and a commission was formed, consisting of Professor Hummel, assisted by Professor Holten, Instructor Lorenz and Winstrup, a mechanic. As early as December, 1868, Professor Hummel, together with head-master Ibsen from Sorø, had visited dyer Gülich of Christianshavn, where one of the machines was located, and they made a few tests, which Hummel himself did not consider to be of any importance. The experiments were to be made in April, 1869, after an assistant had made a preliminary experiment, but then Kähler reported that he had taken the machine apart, in order to make an alteration therein, and that this would take a couple of months. It appears, from a letter from Hjorth to the Ministry of the Interior, that Hjorth had arrived at the conclusion that he must resort to the use of electro-magnets, to a certain extent, at least, on account of »the steel, by continued use, losing part of its magnetic power, which necessitates its being re-magnetized«, and partly because »it appears that electro-magnets[28] may be made to yield a considerably larger magnetic power than steel magnets, by means of the electrical current induced thereby«. As this change to the dynamo principle was estimated to cost 400 rixdollars, Hjorth was informed, in April 1869, that this amount would be paid out of the sum, granted for the experiments, when the smaller machine had been re-built.

Hjorth’s answer to this was a petition that the 400 rixdollars might be spent on any battery, which he might build. Hereafter the case died out. His petition was not answered until in April 1870, and the answer was a refusal.—At that time Hjorth was in delicate health, and his energy had been broken, and a few month’s afterwards he died, on the 28th of August, 1870. He was survived by his wife, who died on the 30th of September 1885.

This indefatigable worker did not succeed in seeing or reaping the harvest of his work for the utilization of electricity,—perhaps his aim had been too high. At a period when in all countries stone was added to stone in the foundation now supporting electrical engineering, we Danes have also made our contribution. Hjorth did not possess the profound knowledge nor the sharper insight necessary in order to avoid errors, but his perseverance, his industry, and his sacrifices, ought to be acknowledged, and his name ought to be venerated on account of his contributions to the development of electric machinery.

[29]

After Hjorth’s death, few knew that he had discovered the dynamo principle. If Hjorth himself had understood the importance of this discovery, and the magnitude of the revolutions to be caused thereby, he would undoubtedly have endeavoured to propagate the knowledge thereof. It was not until 1879, when Colonel Bolton read a paper before the Society of Telegraph Engineers in London, that Hjorth’s patent No. 2198, of 1854, was again brought out of oblivion, and accompanied by these words: »This appears to involve the principle which was later on taken up by others«. Count du Moncel, who had received Hjorth’s representative in 1867, when reading these words, was reminded of the case. Thereafter he has given Hjorth a fair redress in the above-cited article in the valuable periodical »La lumière électrique«, edited by him, the heading being »The Actual Inventor of the Principle of the Dynamo-Electric Machine«.

Among the few printed sources of information concerning Søren Hjorth and his inventions, the following may also be mentioned:

C. Nyrop: Industriforeningen i København, 1838-1888.

Du Moncel: L’éclairage électrique, 1884, page 102.

Electrician, July 8th, 1882.

La lumière électrique, 1883, VIII, page 58.

The most important source is the papers, left by Hjorth, which comprise a considerable collection of drawings, letters, and rough copies of letters written by him. These documents furnish full information, not only of Hjorth’s inventions, but also of his entire reasoning and manner of being. Probably the most interesting of all are his note-books and sketch-books, wherein he used to note down his ideas in English, and which are accompanied by neatly made, coloured sketches. These papers were not accessible to the public until the autumn of 1908, and they are now preserved in the archives and library of the Polytechnic Institute in Copenhagen.

Important contributions to Hjorth’s history have also been obtained from the State Archives, the Archives of the Society of Science, the Archives of the Polytechnic Institute and from the papers left by H. C. Ørsted.

[1] According to the usual terminology of those times, an »electro-magnetic« machine means a machine driven by electricity, an electromotor, while, on the other hand, a »magneto electric battery«, or a »dry battery« is a machine for producing electricity.

[2] Specification of Patent No. 12295, 1848.

[3] After the publication of my first treatise in the »Elektroteknikeren«, for February 1907, various parties have objected that Hjorth, in his dynamos, did not use the dynamo principle in its purest form, as he had one large, unwound, cast iron magnet. On the contrary, the above-mentioned leaf of his sketch-book shows that Hjorth, as early as in 1851, has used the dynamo principle in its purest from—exactly the same as used by Siemens in 1867—as all the field magnets have been wound cast iron magnets, and the initial current is induced by the remnant magnetism of these magnets. S. S.

[4] This is correct, as long as he uses armatures with but a single winding, because, in that case, the number of armature windings is proportional to the number of steel magnets. Whereas Hjorth is mistaken, when in 1867 he makes the same statement about a machine, where nothing prevents the armature from being fitted with a great number of windings.

[5] Specification of Patent No. 2198, 1854.

[6] Specification of Patent No. 806, 1855.

[7] Specification of Patent No. 2199, 1854.

[8] Specifications of Patents No. 807 and 808, 1855.

[9] Hjorth’s English passport, from 1855, contains this information: Height: 5 feet 7 inches, Complexion: fresh, Eyes and Hair: grey.

Footnotes have been moved to the end of the text and relabeled consecutively through the document.

Illustrations have been moved to paragraph breaks near where they are mentioned.

Punctuation has been made consistent.

Variations in spelling and hyphenation were retained as they appear in the original publication, except that obvious typographical errors have been corrected.