Ruth of the U. S. A.

Ruth crouched beside Gerry, and shot through the wreckage at the circling German plane

Title: Ruth of the U. S. A.

Author: Edwin Balmer

Illustrator: Harold Harrington Betts

Release date: June 12, 2022 [eBook #68296]

Language: English

Original publication: United States: A. C. McClurg & Co

Credits: Roger Frank and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

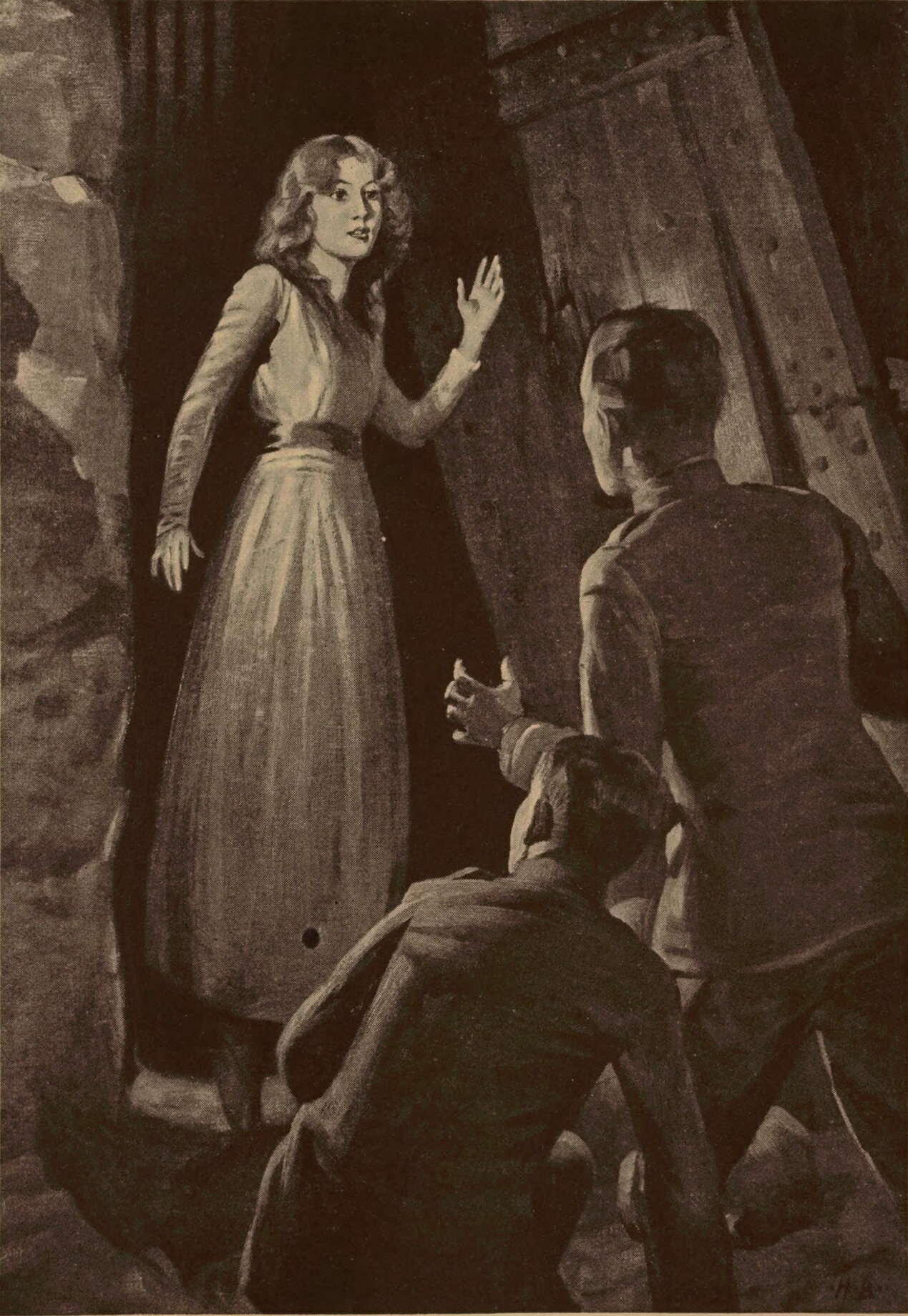

Ruth crouched beside Gerry, and shot through the wreckage at the circling German plane

It was the day for great destinies. Germany was starving; yet German armies, stronger and better prepared than ever before, were about to annihilate the British and the French. Austria, crumbling, was secretly suing for peace; yet Austria was awaiting only the melting of snow in the mountain passes before striking for Venice and Padua. Russia was reorganizing to fight again on the side of the allies; Russia, prostrate, had become a mere reservoir of manpower for the Hohenzollerns. The U-boats were beaten; the U-boats were sweeping the seas. America had half a million men in France; America had only “symbolical battalions” parading in Paris.

A thousand lies balanced a thousand denials; the pointer of credulity swung toward the lies again; and so it swung and swung with everything uncertain but the one fact which seemed, on this day, perfectly plain—American effort had collapsed. America not only had failed to aid her allies during the nine months since she had entered the war; she seemed to have ceased even to care for herself. Complete proof of this was that for five days now industries had been shut down, offices were empty, furnaces cold.

Upon that particular Tuesday morning, the fifth day of this halt, a girl named Ruth Alden awoke in an underheated room at an Ontario Street boarding house—awoke, merely one of the millions of the inconsiderable in Chicago as yet forbidden any extraordinary transaction either to her credit or to her debit in the mighty accounts of the world war. If it be true that tremendous fates approaching cast their shadows before, she was unconscious of such shadows as she arose that morning. To be sure, she reminded herself when she was dressing that this was the day that Gerry Hull was arriving home from France; and she thought about him a good deal; but this was only as thousands of other romance-starved girls of twenty-two or thereabouts, who also were getting up by gaslight in underheated rooms at that January dawn, were thinking about Gerry Hull. That was, Ruth would like, if she could, to welcome him home to his own people and to thank him that day, in the name of his city and of his country, for what he had done. But this was to her then merely a wild, unrealizable fantasy.

What was actual and immediately before her was that Mr. Sam Hilton—the younger of the Hilton brothers, for whom she was office manager—had a real estate deal on at his office. He was to be there at eight o’clock, whether the office was heated or not, and she also was to be there to draw deeds and releases and so on; for someone named Cady who was over draft age, but had himself accepted by an engineer regiment, was sacrificing a fine factory property for a quick sale and Sam Hilton, who was in class one but still hoped somehow to avoid being called, was snapping up the bargain.

So Ruth hurried downtown much as usual upon that cold morning; and she felt only a little more conscious contempt for Sam Hilton—and for herself—as she sat beside him from eight until after nine, with her great coat on and with her hands pulled up in her sleeves to keep them warm while he schemed and reschemed to make a certain feature of his deal with the patriotic Cady more favorable to himself. He had tossed the morning paper upon his desk in front of him with the columns folded up which displayed Gerry Hull’s picture in his uniform and which told about Gerry Hull’s arriving that morning and about his service in France. Thus Ruth knew that Sam Hilton had been reading about Lieutenant Hull also; and, indeed, Hilton referred to him when he had made the last correction upon the contract and was in good humor and ready to put business aside for a few minutes and be personal.

“Gerry Hull’s come home today from France, I see. Some fighter, that boy!” he exclaimed with admiration. “Ain’t he?”

Ruth gazed at Hilton with wonder. She could have understood a man like Sam Hilton if he refused to read at all about Gerry Hull; or she could have understood if, reading, Sam Hilton denied admiration. But how could a young man know about Lieutenant Hull and admire him and feel no personal reproach at himself staying safe and satisfied and out of “it”?

“Some flier!” he was going on with his enthusiastic praise. “How many Huns has he got—fourteen?”

Ruth knew the exact number; but she did not tell him. “Lieutenant Hull is here under orders and upon special duty,” she said. “They sent him home or he wouldn’t be away from the front now.” The blood warmed in her face as she delivered this rebuke gently to Sam Hilton. He stared at her and the color deepened, staining her clear, delicate temples and forehead. “They had to send him here to stir us up.”

“What’s the matter with us?” Sam Hilton questioned with honest lack of concern. Her way of mentioning Gerry Hull had not hit him at all; and he was not seeking any answer to his question. He was watching Ruth flush and thinking that she was mighty pretty with as much color as she had now. He liked her in that coat, too; for the collar of dark fur, though not of good quality, made her youthful face even more “high class” looking than usual. Sam Hilton spent a great deal of money on his own clothes without ever achieving the coveted “class” in his appearance; while this girl, who worked for him and who had only one outfit that he ever saw, always looked right. She came of good people, he knew—little town people and not rich, since she had to work and send money home; but they were “refined.”

Ruth’s bearing and general appearance had pretty well assured Sam of this—the graceful way she stood straight and held up her head, the oval contour of her face as well as the pretty, proud little nose and chin, sweet and yet self-reliant like her eyes which were blue and direct and thoughtful looking below brown brows. Her hair was lighter than her brows and she had a great deal of it; a little wavy and a marvelous amber in color and in quality. It seemed to take in the sunlight like amber when she moved past the window and to let the light become a part of it. Her hands which she thrust from her sleeves now and clasped in front of her, were small and well shaped, though strong and capable too. She had altogether so many “refined” characteristics that it was only to make absolutely certain about her and her family that Sam had paid someone ten dollars to verify the information about herself which she had supplied when he had employed her. This information, fully verified, was that her father, who was dead, had been an attorney at Onarga, Illinois, where her mother was living with three younger sisters, the oldest fourteen. Mrs. Alden took sewing; and since Ruth sent home fifteen dollars a week out of her twenty-five, the family got along. This fifteen dollars a week, totaling seven hundred and eighty a year which the family would continue to need and would expect from Ruth or from whomever married her, bothered Sam Hilton. But he thought this morning that she was worth wasting that much for as he watched her small hands clasping, watched the light upon her hair and the flush sort of fluttering—now fading, now deepening—on her smooth cheek. Having banished business from his mind, he was thinking about her so intently that it did not occur to him that she could be thinking of anyone else. Sam Hilton could not easily imagine anyone flushing thus merely because she was dreaming of a boy whom she had never met and could never meet and who certainly wouldn’t know or care anything about her.

“He was hurt a couple of weeks ago,” she said, “or probably he wouldn’t have left at all.”

That jolted Sam Hilton. It did not bring him any rebuke; it simply made him angry that this girl had been dreaming all that time about Gerry Hull instead of about himself.

“Was the Lady Agnes hurt too?” he asked.

“Hurt? No.”

“Well, she’s come with him.” Sam leaned forward and referred to the folded newspaper. “‘Lady Agnes Ertyle, the daughter of the late Earl of Durran who was killed at Ypres in 1915, whose two brothers fell, one at Jutland on the Invincible and the other at Cambrai,’” he read aloud, “‘is also in the party.’” He skipped down the column condensing the following paragraphs: “She’s to stay at his mamma’s house on Astor Street while in Chicago. She’s twenty-one; her picture was printed yesterday. Did you see it?”

This was a direct question; and Ruth had to answer, “Yes.”

“He’s satisfied with her, I should say; but maybe he’s come home to look further,” Sam said with his heaviest sarcasm. He straightened, satisfied that he had brought Ruth back to earth. “Now I’m going over to see Cady; he’ll sign this as it is, I think.” Sam put the draft of the contract in his pocket. “He leaves town this noon, so he has to. I’ll be all clear by twelve. You’re clear for the day now. Have lunch with me, Miss Alden?”

Ruth refused him quietly. He often asked her for lunch and she always refused; so he was used to it.

“All right. You’re free for the day,” he repeated generously and, without more ceremony, he hurried off to Cady.

Ruth waited until he had time to leave the building before she closed the office and went down the stairs. She stepped out to the street, only one girl among thousands that morning dismissed from bleak offices—one of thousands to whom it seemed ignominious that day, when all the war was going so badly and when Gerry Hull was arriving from France, to go right back to one’s room and do nothing more for the war than to knit until it was time to go to bed and sleep to arise next morning to come down to make out more deeds and contracts for men like Sam Hilton.

Had it been a month or two earlier, Ruth again would have made the rounds of the headquarters where girls gave themselves for real war work; but now she knew that further effort would be fruitless. Everyone in Chicago, who possessed authority to select girls for work in France, knew her registration card by heart—her name, her age, the fact that she had a high-school education. They were familiar with the occupations in which she claimed experience—office assistant; cooking; care of children (had she not taken care of her sisters?); first aid; can drive motor car; operate typewriter. Everyone knew that her health was excellent; her sight and hearing perfect. She would go “anywhere”; she would start “at any time.” But everyone also knew that answer which truth had obliged her to write to the challenge, “What persons dependent upon you, if any?” So everyone knew that though Ruth Alden would give herself to any work, someone had to find, above her expenses, seven hundred and eighty dollars a year for her family.

Accordingly she could think of nothing better to do this morning than to join the throng of those who were going to Michigan Avenue and to the building where the British and French party, with which Gerry Hull was traveling, would be welcomed to the city. Ruth had no idea of being admitted to the building; she merely stood in the crowd upon the walk; but close to where she stood, a limousine halted. A window of the car was down; and suddenly Ruth saw Gerry Hull right before her. She knew him at once from his picture; he was tall and active looking, even though sitting quiet in the car; he was bending forward a bit and the sudden, slight motions of his straight, lithe shoulders and the quick turn of his head as he gazed out, told of the vigor and impetuousness which—Ruth knew—were his.

He had a clear, dark skin; his hair and brows were dark; his eyes, blue and observant and interested. He had the firm, determined chin of a fighter; his mouth was pleasant and likable. He was younger looking than his pictures had made him appear; not younger than his age, which Ruth knew was twenty-four. Indeed, he looked older than four and twenty; yet one could not say that he looked two years older or five or ten; the maturity which war had brought Gerry Hull was not the sort which one could reckon in years. It made one—at least it made Ruth—pulse all at once with amazing feeling for him, with a strange mixture of anger that such a boy must have experienced that which had so seared his soul, and of pride in him that he had sought the experience. He was a little excited now at being home again, Ruth thought, in this city where his grandfather had made his fortune, where his father had died and where he, himself, had spent his boyhood; he turned to point out something to the girl who was seated beside him; so Ruth gazed at her and recognized her, too. She was Lady Agnes Ertyle, young and slight and very lovely with her brown hair and gray eyes and fair, English complexion and straight, pure features. She had something too of that maturity, not of years, which Gerry Hull had; she was a little tired and not excited as was he. But for all that, she was beautiful and very young and not at all a strange creation in spite of her title and in spite of all that her family—her father and her brothers and she herself—had done in Belgium and in France. Indeed, she was only a girl of twenty-two or three. So Ruth quite forgot herself in the feeling of rebuke which this view of Gerry Hull and Lady Agnes brought to her. They were not much older or intrinsically different from herself and they had already done so much; and she—nothing!

She was so close to them that they had to observe her; and the English girl nodded to her friendlily and a little surprised. Gerry Hull seemed not surprised; but he did not nod; he just gazed back at her.

“What ought I be doing?” Ruth heard her voice appealing to them.

Lady Agnes Ertyle attempted no reply to this extraordinary query; but Gerry Hull’s eyes were studying her and he seemed, in some way, to understand her perplexity and dismay.

“Anyone can trust you to find out!” he replied to her aloud, yet as if in comment to himself rather than in answer to her. The car moved and left Ruth with that—with Gerry Hull’s assurance to himself that she could be trusted to discover what she should do. She did not completely understand what he meant; for she did not know what he had been thinking when she suddenly thought out aloud before him and surprised him into doing the same. Nevertheless this brief encounter stirred and stimulated her; she could not meekly return to her room after this; so, when the crowd broke up, she went over to State Street.

The wide, wind-swept way, busy and bleak below the towering sheer of the great department stores, the hotels and office buildings on either hand seemed to Ruth never so sordid and self-concerned as upon this morning. Here and there a flag flapped from a rope stretched across the street or from a pole pointing obliquely to the sky; but these merely acknowledged formal recognition of a state of war; they were not symbols of any evident performance of act of defense. The people who passed either entirely ignored these flags or noticed them dully, without the slightest show of feeling. Many of these people, as Ruth knew, must have sons or brothers in the training camps; a few might possess sons in the regiments already across the water; but if Ruth observed any of these, she was unable to distinguish them this morning from the throng of the indifferent going about their private and petty preoccupations with complete engrossment. Likewise was she powerless to discriminate those—not few in number—who mingled freely in the groups passing under the flags but who gazed up, not with true indifference, but with hotly hostile reactions.

The great majority even of the so-called Germans in Chicago were loyal to America, Ruth knew; but from the many hundred thousand who, before the American declaration of war, had sympathized with and supported the cause of the Fatherland, there were thousands now who had become only more fervent and reckless in their allegiance to Germany since the United States had joined its enemies—thousands who put the advantage of the Fatherland above every individual consideration and who, unable to espouse their cause now openly, took to clandestine schemes of ugly and treacherous conception. Thought of them came to Ruth as she passed two men speaking in low tones to each other, speaking in English but with marked Teutonic accent; they stared at her sharply and with a different scrutiny from that which men ordinarily gave when estimating Ruth’s face and figure. One of them seemed about to speak to her; but, glancing at the other people on the walk, he instantly reconsidered and passed by with his companion. Ruth flushed and hurried on down the street until suddenly she realized that one of the men who had stared at her, had passed her and was walking ahead of her, glancing back.

She halted, then, a little excited and undecided what was best to do. The man went on, evidently not venturing the boldness of stopping, too; and while Ruth remained undecided, a street beggar seized the opportunity of offering her his wares.

This man was a cripple who, in spite of the severe cold of the morning, was seated on the walk with his crutches before him; he pretended to be a pencil vendor and displayed in his mittened hand an open box half full of pencils; and he had a pile of unopened boxes at his side. He had taken station at that particular spot on State Street where most people must pass on their way to and from the chief department stores; but his trade evidently had been so slack this morning that he felt need of more aggressive mendicancy. He scrambled a few yards up the walk to where Ruth had halted and, gazing up at her, he jerked the edge of her coat.

“Buy a pencil, lady?”

Ruth looked down at the man, who was very cold and ill-dressed and pitiful; she took a dime from her purse and proffered it to him. He gazed up at her gratefully and with keen, questioning eyes; and, instead of taking a pencil from his open box, he picked up one of the unopened boxes which he had carried with him.

“Take a box, lady,” he pleaded, squirming with a painful effort which struck a pang of pity through Ruth; it made her think, not alone of his crippled agony, but the pain of the thousands—of the millions from the battle fields.

Ruth returned her dime to her purse and took out a dollar bill; the beggar thrust the mittened fingers of his left hand between his teeth, jerked off the ragged mitten and grabbed the dollar bill.

“That pays for two boxes,” he said, gazing again up at Ruth keenly.

“I’ll take two,” Ruth said, accepting the sale which the man had forced rather than deciding it herself.

He selected two boxes from the pile at his side and, glancing at her face sharply once more, he handed her the boxes and thanked her. She thrust the boxes into her muff and hurried on.

When she realized the strangeness of this transaction a few moments later, it seemed to have been wholly due to the beggar’s having taken advantage of her excitement after meeting Gerry Hull and her uneasiness at being followed by the German. She had no use for two boxes of cheap pencils and she could not afford to give a dollar to a street cripple who probably was an impostor. She felt that she had acted quite crazily; now she had to take a North State Street car to return to her room.

She had been saving, out of her money which she kept for herself, a ridiculous little fund to enable her perhaps to take advantage of a chance to “do” something some day; now because Lieutenant Hull had spoken kindly to her, she had flung away a dollar. She tried to keep her thought from her foolishness; and she succeeded in this readily by reviewing all the slight incident of her meeting with Gerry Hull. She had known something about him ever since she was a little girl, and pictures of him—a little boy with his grandfather—and articles about his grandfather and about him, too, appeared in the Chicago newspaper which her father read. Ruth could recall her father telling her about the great Andrew Hull, how he had come to Chicago as a poor boy and had made himself one of the greatest men in the industrial life of the nation; how he owned land and city buildings and great factories and railroads; and the reason that the newspapers so often printed the picture of the little boy was because some day he would own them all.

And Ruth knew that this had come true; and that the little boy, whose bold, likeable face had looked out upon her from the pictures; the tall, handsome, athletic and reckless youth who had gone to school in the East and, later, in England had become the possessor of great power and wealth in Chicago but instead of being at all spoiled by it, he was a clean, brave young man—a soldier having offered himself and having fought in the most perilous of all services and having fought well; a soldier who was a little flushed and excited about being home again among his people and who had spoken friendlily to her.

Ruth reached her room, only remembering the pencil boxes when she dropped them from her muff upon her table. The solid sound they made—not rattling as pencils should—caused her to tear the pasted paper from about one box. She had bought not even pencils but only boxes packed with paper. Now she had the cover off and was staring at the contents. A new fifty dollar bank note was on top. Underneath that was another; below that, another—others. They made a packet enclosed in a strip such as banks use and this was denominated $1,000.00. There were twenty fifty-dollar notes in this packet.

Ruth lifted it out; she rubbed her eyes and lifted out another packet labeled one thousand dollars made up of ten bills of one hundred dollars each; on the bottom were five one hundred dollar notes, not fastened together. The box held nothing else.

Her pulses pounded and beat in her head; her hands touching the money went hot, went cold. This money was real; but her obtaining it must be a mistake. The box must have been the beggar’s bank which he had kept beside him; therefore his money had no meaning for her. But now the cripple’s insistence upon halting her, his keen observation of her, his slowness at last to make the sale, stirred swift instincts of doubt. She seized and tore open the other box which she had bought.

No pencils in it; nor money. It held printed or engraved papers, folded and refolded tightly. One huge paper was on top, displaying bright red stamps and a ribbon and seals. This was an official government document; a passport to France! The picture of the holder was pasted upon a corner, stamped with the seal of the United States; and it was her picture! In strange clothes; but herself!

For the instant, as things swam before her in her excitement, there came to Ruth the Cinderella wonder which a girl, who has been really a little child once, can never quite cease to believe—the wonder of a wish by magic made true. The pencils in the beggar’s boxes had been changed by her purchase of them to money for her and a passport to France. And for this magic, Gerry Hull was in some way responsible. She had appealed to him; he had spoken to her and thenceforth all things she touched turned to fairy gold—or better than gold; American bank notes and a passport to France!

Then the moment of Ruth, the little girl and the dreamer, was gone; and Ruth, the business woman competent to earn twenty-five dollars a week, examined what she held in her hand. As she made out the papers more clearly, her heart only beat faster and harder; her hands went moist and trembled and her breath was pent in by presence of the great challenge which had come to her, which was not fairy at all but very real and mortal and which put at stake her life and honor but which offered her something to “do” beyond even her dreams. For the picture upon the passport was not of her but only of a girl very much like her; the name, as inscribed in the body of the passport and as written in hand across the picture and under the seal of the United States, was not her own but of someone named Cynthia Gail; and along with the passport was an unattached paper covered with small, distinct handwriting of a man relating who Cynthia Gail was and what the recipient of this money and this passport was expected to do. This paper like the passport was complete and untorn. There was besides a page of correspondence paper, of good quality, written upon both sides in the large, free handwriting of a girl—the same hand which had signed the photograph and the passport, “Cynthia Gail.”

Ruth read these papers and she went to her door and locked it, she went to her window and peered cautiously out. If anyone had followed her, he was not now in evidence. The old, dilapidated street was deserted as usual at this time and on such a day except for a delivery truck speeding past, a woman or two on the way to the car line, and a few pallid children venturing out in the cold. Listening for sounds below, Ruth heard no unusual movements; so she drew far back from the window with the money and with the passport and with the explanatory paper and the letter which she laid before her and examined most carefully again.

The man who had formed the small, distinct characters covering the paper of instructions had written in English; but while he was quite familiar with English script, it was evident that he had written with the deliberate pains of a person who realizes the need of differentiating his letters from the formation natural to him. That formation, clearly, was German script. Like everyone else, Ruth knew German families; and, like many other American girls who had been in high schools before the outbreak of the war, she had chosen German for a modern language course. Indeed, she had learned German well enough so that when confronted by the question on her War Registration card, What foreign languages do you read well? she had written, German.

She had no difficulty, therefore, in recognizing from the too broad tops of the a’s, the too pointed c’s and the loops which twice crossed the t’s that the writer had been educated first to write German. He had failed nowhere to carefully and accurately write the English form of the letters for which the German form was very different, such as k and r and s; it was only in the characters where the two scripts were similar that his care had been less.

You are (he had written) the daughter of Charles Farwell Gail, a dry-goods merchant of Decatur, Illinois. Your father and mother—ages 48 and 45—are living; you have one older brother, Charles, now twenty-six years old who quarreled with his father four years ago and went away and has not been heard from. The family believe that he entered the war in some capacity years ago; if so, he probably was killed for he was of reckless disposition. You do not write to him, of course; but in your letters home you refer to being always on watch for word from Charles. You were twenty-four years old on November 17. You have no sisters but one younger brother, Frank, 12 on the tenth of May, who is a boy scout; inform him of all boy-scout matters in your letters. Your other immediate family is a sister of your mother now living with your parents; she is a widow, Mrs. Howard Grange, maiden name Cynthia Gifford. You were named for her; she has a chronic ailment—diabetes. You write to her; you always inquire of her condition in letters to your parents. Your closest girl friend is Cora Tresdale, La Salle, Illinois, who was your roommate at Wellesley College, Wellesley, Mass.; you were both class of 1915; you write to her occasionally. You recently have been much interested in 2nd Lieutenant George A. Byrne, from Decatur, now at Camp Grant; he saw you in Chicago this past Saturday. Probably you are engaged to him; in any case, your status with him will be better defined by letter which will arrive for you at the Hotel Champlain, this city, Room 347.

It is essential that you at once go to hotel and continue your identity there. Immediately answer by telegram any important inquiry for you; immediately answer all letters. Buy a typewriter of traveling design and do all correspondence on that, saying that you are taking it up for convenience. Your signature is on passport; herewith also a portion of letter with your writing. So far as known, you do not sign nicknames, except to your father to whom you are “Thia.” Mail arriving for you, or to arrive at hotel, together with possessions in room will inform you of your affairs more fully. So far as now known you have no intimate friends in Chicago; you are to start Thursday evening for Hoboken where you report Saturday morning to Mrs. Donald G. Gresham for work in the devastated districts in France, where you will observe all desired matters, particularly in regard to number, dispositions, personnel, equipment and morale of arriving American forces; reporting. If and when it proves impractical to forward proper reports, you will make report in person, via Switzerland; apply for passport to Lucerne.

With this, the connected writing abruptly ended; there was no signature and no notation except at the bottom of the sheet was an asterisk referring to an asterisk before the first mention of “mother.” This note supplied, “Mother’s maiden name, Julia Trowbridge Gifford,” and also the street address in Decatur. Below that was the significant addenda:

Cynthia Gail killed in Sunday night wreck; identification now extremely improbable; but watch papers for news. No suspicion yet at home or hotel; but you must appear at once and answer any inquiry.

This last command, which was a repetition, was emphatically underlined. The page of the letter in Cynthia Gail’s handwriting was addressed to her mother and was largely a list of clothing—chemises, waists, stockings, and other articles—which she had bought in Chicago and charged to her father’s account at two department stores. A paragraph confided to her mother her feeling of insignificance at the little part she might play in the war, though it had seemed so big before she started away:

Yet no one knows what lies before one; even I may be given my great moment to grasp!

The letter was unfinished; Cynthia Gail evidently had been carrying it with her to complete and mail later when she was killed.

Ruth placed it under her pillow with the other paper and the passport and the money; she unlocked her door and went out, locking it behind her; descending to the first floor, she obtained the yesterday’s paper and brought it back to her room. She found readily the account of a wreck on Sunday evening when a train had crashed through a street car. It had proved very difficult to identify certain of the victims; and one had not been identified at all; she had been described only as a young girl, well dressed, fur toque, blue coat with dark fur collar.

The magic of this money and the passport had faded quite away; the chain of vital, mortal occurrences which had brought them to Ruth Alden was becoming evident.

There had been, first of all, an American girl named Cynthia Gail of Decatur, Illinois, young like Ruth but without responsibilities, loyal and ardent to play her part in the war. She had applied for overseas work; the government therefore had investigated her, approved her and issued her a passport and permitted her to make all arrangements for the journey to France and for work there. She had left her home in Decatur and had come alone, probably, to Chicago, arriving not later than Saturday. She apparently had been alone in the city on Sunday evening after Lieutenant George Byrne had returned to Camp Grant; also it was fairly certain that she had no intimate friends in Chicago as she had been stopping at a hotel. On Sunday evening she had been on the car which was struck by the train.

This much was positive; the next circumstances had more of conjecture; but Ruth could reason them out.

Someone among those who first went to the wreck found Cynthia Gail dead and found her passport upon her. This person might have been a German agent who was observing her; much more probably he was simply a German sympathizer who was sufficiently intelligent to appreciate at once the value of his find. At any rate, someone removed the passport and letter and other possessions which would identify Cynthia Gail; and that someone either acted promptly for himself and for Germany or brought his discoveries to others who acted very energetically. For they must immediately have got in touch with people in Decatur who supplied them with the information on the page of instructions; and they also must have made investigation of Cynthia Gail’s doings in Chicago.

The Germans thereupon found that they possessed not merely a passport but a most valuable post and an identity to use for their own purposes. If they could at once substitute one of their own people for Cynthia Gail—before inquiry for Cynthia Gail would be made or knowledge of her loss arise—this substitute would be able to proceed to France without serious suspicion; she would be able to move about with considerable freedom, probably, in the districts of France where Americans were holding the lines and could gather and forward information of all sorts of the greatest value to the Germans. They simply must find a German girl near enough like Cynthia Gail and clever and courageous enough to forge her signature, assume her place in her family, and in general play her rôle.

It was plain that the Germans who obtained the passport knew of some German girl upon whom they could depend; but they could not—or did not dare to attempt to—communicate directly with her. Ruth knew vaguely that hundreds of Germans, suspected of hostile activities, silently had disappeared. She knew that the American secret service constantly was causing the arrest of others and keeping many more under observation. It was certain, therefore, that communication between enemy agents in Chicago must have been becoming difficult and dangerous; moreover, Ruth had read that it was a principle of the German spy organization to keep its agents ignorant of the activities of others in the same organization; so it seemed quite probable that the people who had possession of Cynthia Gail’s passport knew that there was a German girl in the city who might play Cynthia’s part but that they could not locate her. Yet they were obliged to find her, and to do it quickly, so that she could take up the rôle of Cynthia Gail before inquiries would be made.

What better way of finding a girl in Chicago than posting yourself as a beggar on State Street between the great stores? It was indeed almost certain that if the girl they sought was anywhere in the city, sooner or later she would pass that spot. Obviously the two Germans who had mixed with the crowd on State Street also had been searching for their German confederate; they had mistaken Ruth for her; and one of them had somehow signaled the beggar to accost her.

This had come to Ruth, therefore, not because she was chosen by fate; it simply had happened to her, instead of to another of the hundreds of girls who had passed down State Street that morning, because she chanced to possess a certain sort of hair and eyes, shape of nose and chin, and way of carrying her head not unique at all but, in fact, very like two other girls—one who had been loyal and eager as she, but who now lay dead and another girl who had been sought by enemy agents for their work, but who had not been found and who, probably, would not now be found by them.

For, after giving the boxes to Ruth, the German who played the beggar would not search further; that delivery of the passport and the orders to her was proof that he believed she was the girl he sought. She had only to follow the orders given and she would be accepted by other German agents as one of themselves! She would pretend to them that she was going as a German spy into France in order that she could go, an American spy, into Germany! For that was what her orders read.

“You will report in person via Switzerland!” they said.

What a tremendous thing had been given her to do! What risks to run; what plans to make; what stratagems to scheme and to outwit! Upon her—her who an hour ago had been among the most futile and inconsiderable in all the world of war—now might hang the fate of the great moment if she did not fail, if she dared to do without regard to herself to the uttermost! She must do it alone, if she was to do it at all! She could not tell anyone! For the Germans who had entrusted this to her might be watching her. If she went to the American Secret Service, the Germans almost surely would know; and that would end any chance of their continuing to believe her their agent. No; if she was to do it, she must do it of herself; and she was going to do it!

This money, which she recounted, freed her at once from all bonds here. She speculated, of course, about whose it had been. She was almost sure it had not been Cynthia Gail’s; for a young girl upon an honest errand would not have carried so great an amount in cash. No; Ruth had heard of the lavishness with which the Germans spent money in America and of the extravagant enterprises they hazarded in the hope of serving their cause in some way; and she was certain that this had been German money and that its association with the passport had not begun until the passport fell into hostile hands. The money, consequently, was Ruth’s spoil from the enemy; she would send home two thousand dollars to free her from her obligation to her family for more than two years while she would keep the remainder for her personal expenses.

The passport too was recovered from the enemy; yet it had belonged to that girl, very like Ruth, who lay dead and unrecognized since this had been taken from her. There came to Ruth, accordingly, one of those weak, peacetime shocks of horror at the idea of leaving that girl to be put away in a nameless grave. As if one more nameless grave, amid the myriads of the war, made a difference!

Ruth gazed into the eyes of the girl of the picture; and that girl’s words, which had seemed only a commonplace of the letter, spoke articulate with living hope. “Even I may be given my great moment to grasp!”

What could she care for a name on her grave?

“You can’t be thinking of so small and silly a thing for me!” the girl of the picture seemed to say. “When you and I may save perhaps a thousand, ten thousand, a million men! I left home to serve; you know my dreams, for you have dreamed them too; and, more than you, I had opportunity offered to do. And instead, almost before I had started, I was killed stupidly and, it seemed for nothing. It almost happened that—instead of serving—I was about to become the means of betrayal of our armies. But you came to save me from that; you came to do for me, and for yourself, more than either of us dreamed to do. Be sure of me, as I would be sure of you in my place! Save me, with you, for our great moment! Carry me on!”

Ruth put the picture down. “We’ll go on together!” she made her compact with the soul of Cynthia Gail.

She was glad that, before acting upon her decision, she had no time to dwell upon the consequences. She must accept her rôle at once or forever forsake it. Indeed, she might already be too late. She went to her washbowl and bathed; she redid her hair, more like the girl in the picture. The dress which she had been wearing was her best for the street so she put it on again. She put on her hat and coat; she separated two hundred dollars from the rest of the money and put it in her purse; the balance, together with the passport and the page of Cynthia Gail’s letter, she secured in her knitting bag. The sheet of orders with the information about Cynthia Gail gave her hesitation. She reread it again carefully; and she was almost certain that she could remember everything; but, being informed of so little, she must be certain to have that exact. So she reached for her leaflet of instructions for knitting helmets, socks, and sweaters, and she wrote upon the margin, in almost imperceptible strokes, shorthand curls and dashes, condensing the related facts about Cynthia Gail. She put this in her bag, destroyed the original and, taking up her bag, she went out.

Every few moments as she proceeded down the dun and drab street, in nowise changed from the half hour before, she pressed the bag against her side to feel the hardness of the packets pinned in the bottom; she needed this feelable proof to assure her that this last half hour had not been all her fantasy but that truly the wand of war, which she had seen to lift so many out of the drudge of mean, mercenary tasks, had touched her too.

She hailed a taxicab as soon as she was out of sight of the boarding house and directed it to the best downtown store where she bought, with part of the two hundred dollars, such a fur toque and such a blue coat with a fur collar as she supposed Cynthia Gail might have possessed. She had qualms while she was paying for them; she seemed to be spending a beggar’s money, given her by mistake. She wore the new toque and the coat, instructing that her old garments be sent, without name, to the war-relief shop.

Out upon the street again, the fact that she had spent the money brought her only exultation; it had begun to commit her by deed, as well as by determination and had begun to muster her in among those bound to abandon all advantage—her security, her life—in the great cause of her country. It had seemed to her, before, the highest and most wonderful cause for which a people had ever aroused; and now, as she could begin to think herself serving that cause, what might happen to her had become the tiniest and meanest consideration.

She took another taxicab for the Hotel Champlain. She knew this for a handsome and fashionable hotel on the north side near the lake; she had never been in such a hotel as a guest. Now she must remember that she had had a room there since last week and she had been away from it since Sunday night, visiting, and she had kept the room rather than go to the trouble of giving it up. When she approached the hotel, she leaned forward in her seat and glanced at herself in the little glass fixed in one side of the cab. She saw that she was not trembling outwardly and that she had good color—too much rather than too little; and she looked well in the new, expensive coat and toque.

When the cab stopped and the hotel doorman came out, she gave him money to pay the driver and she went at once into the hotel, passing many people who were sitting about or standing.

The room-clerk at the desk looked up at her, as a room-clerk gazes at a good looking and well-dressed girl who is a guest.

“Key, please,” she said quietly. She had to risk her voice without knowing how Cynthia Gail had spoken. That was one thing which the Germans had forgotten to ascertain—or had been unable to discover—for her. But the clerk noticed nothing strange.

“Yes, Miss Gail,” he recognized her, and he turned to take the key out of box 347. “Mail too, Miss Gail?”

“Please.”

He handed Ruth three letters, two postmarked Decatur and one Rockford, and also the yellow envelope of a telegram. He turned back to the box and fumbled for a card.

“There was a gentleman here for you ’bout half an hour ago, Miss Gail,” the clerk recollected. “He waited a while but I guess he’s gone. He left this card for you.”

Ruth was holding the letters and also the telegram unopened; she had not cared to inquire into their contents when in view of others. It was far safer to wait until she could be alone before investigating matters which might further confuse her. So she was very glad that the man who had been “here for her” was not present at that instant; certainly she required all the advantage which delay and the mail and the contents of Cynthia Gail’s room could give her.

She had thought, of course, of the possibility of someone awaiting her; and she had recognized three contingencies in that case. A man who called for her might be a friend or a relative of Cynthia Gail; this, though difficult enough, would be easiest and least dangerous of all. The man might be a United States agent aware that Cynthia Gail was dead, that her passport had fallen into hostile hands; he therefore would have come to take her as an enemy spy with a stolen passport. The man might be a German agent sent there to aid her or give her further orders or information, if the Germans still were satisfied that they had put the passport into proper hands; if they were not—that is, if they had learned that the beggar had made a mistake—then the man might be a German who had come to lure her away to recover the passport and punish her.

The man’s card, with his name—Mr. Hubert Lennon, engraved in the middle—told nothing more about him.

“I will be in my room,” Ruth said to the clerk, when she glanced up from the card. “If Mr. Lennon returns or anyone else calls, telephone me.”

She moved toward the elevator as quickly as possible; but the room-clerk’s eyes already were attracted toward a number of men entering from the street.

“He’s not gone, Miss Gail! Here he is now!” the clerk called.

Ruth pretended not to hear; but no elevator happened to be waiting into which she could escape.

“Here’s the gentleman for you!” a bellboy announced to Ruth so that she had to turn and face then and there the gentleman who had been waiting for her.

The man who advanced from the group which had just entered the hotel, appeared to be about thirty years old; he was tall and sparely built and stooped very slightly as though in youth he had outgrown his strength and had never quite caught up. He had a prominent nose and a chin which, at first glance, seemed forceful; but that impression altered at once to a feeling that here was a man of whom something might have been made but had not. He was not at all dissolute or unpleasant looking; his mouth was sensitive, almost shy, with only lines of amiability about it; his eyes, which looked smaller than they really were because of the thick lenses of his glasses, were gray and good natured and observant. His hair was black and turning gray—prematurely beyond doubt. It was chiefly the grayness of his hair, indeed, which made Ruth suppose him as old as thirty. He wore a dark overcoat and gray suit—good clothes, so good that one noticed them last—the kind of clothes which Sam Hilton always thought he was buying and never procured. He pulled off a heavy glove to offer a big, boyish hand.

“How do you do, Cy—Miss Gail?” he greeted her. He was quite sure of her but doubtful as to use of her given name.

“Hubert Lennon!” Ruth exclaimed, giving her hand to his grasp—a nice, pleased, and friendly grasp. She had ventured that, whoever he was, he had known Cynthia Gail long ago but had not seen her recently; not for several years, perhaps, when she was so young a girl that everyone called her Cynthia. Her venture went well.

She was able to learn from him, without his suspecting that she had not known, that she had an engagement with him for the afternoon; they were to go somewhere—she could not well inquire where—for some event of distinct importance for which she was supposed to be “ready.”

“I’m not ready, I’m sorry to say,” Ruth seized swiftly the chance for fleeing to refuge in “her” room. “I’ve just come in, you know. But I’ll dress as quickly as I can.”

“I’ll be right here,” he agreed.

She stepped into a waiting elevator and drew back into the corner; two men, who talked together, followed her in and the car started upwards. If the Germans had sent someone to the hotel to observe her when she appeared to take the place of Cynthia Gail, that person pretty clearly was not Hubert Lennon, Ruth thought; but she could not be sure of these two men. They were usual looking, middle-aged men of the successful type who gazed at her more than casually; neither of them called a floor until after Ruth asked for the third; then the other said, “Fourth,” sharply while the man who remained silent left the elevator after Ruth. She was conscious that he came behind her while she followed the room numbers along the hallway until she found the door of 347; he passed her while she was opening it. She entered and, putting the key on the inside, she locked herself in, pressing close to the panel to hear whether the man returned. But she heard only a rapping at a door farther on; the man’s voice saying, “I, Adele;” then a woman’s and a child’s voices.

“Nerves!” Ruth reproached herself. “You have to begin better than this.”

She was in a large and well-furnished bedroom; the bed and bureau and dressing table were set in a sort of alcove, half partitioned off from the end of the room where was a lounge with a lamp and a writing desk. These were hotel furniture, of course; the other articles—the pretty, dainty toilet things upon the dressing table, the dresses and the suit upon the hangers in the closet, the nightdress and kimono upon the hooks, the boots on the rack, the waists, stockings, undergarments, and all the other girl’s things laid in the drawers—were now, of necessity, Ruth’s. There was a new steamer trunk upon a low stand beyond the bed; the trunk had been closed after being unpacked and the key had been left in it. A small, brown traveling bag—also new—stood on the floor beside it. Upon the table, beside a couple of books and magazines, was a pile of department-store packages—evidently Cynthia Gail’s purchases which she had listed in her letter to her mother. The articles, having been bought on Saturday, had been delivered on Monday and therefore had merely been placed in the room.

Ruth could give these no present concern; she could waste no time upon examination of the clothes in the closet or in the drawers. She bent at once before the mirror of the dressing table where Cynthia Gail had stuck in two kodak pictures and two cards at the edge of the glass. The pictures were both of the same young man—a tall, straight, and strongly built boy in officer’s uniform; probably Lieutenant Byrne, Ruth thought; at least he was not Hubert Lennon; and the cards in the glass betrayed nothing about him, either; both, plainly, were “reminder” cards, one having “Sunday, 4:30!” written triumphantly across it, the other, “Mrs. Malcolm Corliss, Superior 9979.”

Ruth knew—who in Chicago did not know?—of Mrs. Malcolm Corliss, particularly since America entered the war. Ruth knew that the Superior number was a telephone probably in Mrs. Corliss’ big home on the Lake Shore Drive. Ruth picked up the leather portfolio lying upon the dressing table; opening it, she faced four portrait photographs; an alert, able and kindly looking man of about fifty; a woman a few years younger, not very unlike Ruth’s own mother and with similarly sweet eyes and a similar abundance of beautiful hair. These photographs had been but recently taken. The third was several years old and was of a handsome, vigorous, defiant looking boy of twenty-one or two; the fourth was of a cunning, bold little youth of twelve in boy-scout uniform. Ruth had no doubt that these were Cynthia Gail’s family; she was very glad to have that sight of them; yet they told her nothing of use in the immediate emergency. Her hand fell to the drawer of the dresser where, a moment ago, Ruth had seen a pile of letters; she recognized that she must examine everything; yet it was easier for her to open first the letters which had never become quite Cynthia Gail’s—the three letters and the dispatch which the clerk had given Ruth.

She opened the telegram first and found it was from her father. She was thinking of herself, not as Ruth Alden, but as actually being Cynthia Gail now. It was a great advantage to be able to fancy and to dream; she was Cynthia Gail; she must be Cynthia henceforth or she could not continue what she was doing even here alone by herself; and surely she could not keep up before others unless, in every relation, she thought of herself as that other girl.

Letter received; it’s like you, but by all means go ahead; I’ll back you. Love.

That told nothing except that she had, in some recent letter, suggested an evidently adventurous deviation from her first plan.

The first letter from Decatur which Cynthia Gail now opened was from her mother—a sweet, concerned motherly letter of the sort which that girl, who had been Ruth Alden, well knew and which made her cry a little. It told absolutely nothing about anyone whom Cynthia might meet in Chicago except the one line, “I’m very glad that Mrs. Malcolm Corliss has telephoned to you.” The second letter from Decatur, written a day earlier than the other, was from her father; from this Cynthia gained chiefly the information—which the Germans had not supplied her—that her father had accompanied her to Chicago, established her at the hotel and then been called back home by business. He had been “sorry to leave her alone” but of course she was meeting small risks compared to those she was to run. The letter from Rockford, which had arrived only that morning, was from George—that meant George Byrne. She had been engaged to him, it appeared; but they had quarreled on Sunday; he felt wholly to blame for it now; he was very, very sorry; he loved her and could not give her up. Would she not write him, please, as soon as she could bring herself to?

The letter was all about themselves—just of her and of him. No one else at all was mentioned. The letters in the drawer—eight in number—were all from him; they mentioned, incidentally, many people but all apparently of Decatur; there was no reference of any sort to anyone named Hubert or Lennon.

She returned the letters to their place in the drawer and laid with them those newly received. The mail, if it gave her small help, at least had failed to present any immediately difficult problem of its own. There was apparently no anxiety at home about her; she safely could delay responding until later in the afternoon; but she could not much longer delay rejoining Hubert Lennon or sending him some excuse; and offering excuse, when knowing nothing about the engagement to which she was committed, was perhaps more dangerous than boldly appearing where she was expected. The Germans had told her that they believed she had no close friends in Chicago; and, so far as she had added to that original information, it seemed confirmed.

The telephone bell rang and gave her a jump; it was not the suddenness of the sound, but the sign that even there when she was alone a call might make demand which she could not satisfy. She calmed herself with an effort before lifting the receiver and replying.

“Cynthia?” a woman’s voice asked.

“Yes,” she said.

“It’s a large afternoon affair, dear,” the voice said easily. “But quite wartime. I’d wear the yellow dress.”

“Thank you, I will,” Cynthia said, and the woman hung up.

That shocked Cynthia back to Ruth again; she stood in the center of the room, turning about slowly and with muscles pulling with queer, jerky little tugs. The message had purported to be a friendly telephone call from some woman who knew her intimately; but Ruth quickly estimated that that was merely what the message was meant to appear. For if the woman really were so intimate a friend of Cynthia Gail, she would not have made so short and casual a conversation with a girl whom she could not have seen or communicated with since Sunday. No; it was plain that the Germans again were aiding her; plain that they had learned—perhaps from Hubert Lennon waiting for her in the hotel lobby—about her afternoon engagement; plain, too, that they were ordering her to go.

A new and beautiful yellow dress, suitable for afternoon wear, was among the garments in the closet; there was an underskirt and stockings and everything else. Ruth was Cynthia again as she slipped quickly out of her street dress, took off shoes and stockings and redressed completely. She found a hat which evidently was to be worn with the yellow dress. So completely was she Cynthia now, as she bent for a final look in the glass, that she did not think that she looked better than Ruth Alden ever had; she wondered, instead, whether she looked as well as she should. She found no coat which seemed distinctly for the afternoon; so she put on the coat which she had bought. She carried her knitting bag with her as before—it was quite an advantage to have a receptacle as capacious as a knitting bag which she could keep with her no matter where she went. Descending to the ground floor, she found about the same number and about the same sort of people passing back and forth or lounging in the lobby. Hubert Lennon was there and he placed himself beside her as she surrendered her room key.

“You’re perfectly corking, Cynthia!” he admired her, evidently having decided during his wait that he could say her name.

Color—the delicate rose blush in her clear skin which Sam Hilton so greatly liked—deepened on her cheek.

“All ready now, Hubert,” she said; her use of his name greatly pleased him and he grasped her arm, unnecessarily, to guide her out.

“Just a minute,” she hesitated as she approached the telegraph desk. “I’ve a wire to send to father.”

The plan had popped out with the impulse which had formed it; she had had no idea the moment before of telegraphing to Charles Gail. But now the ecstasy of the daring game—the game beginning here in small perils, perhaps, but also perhaps in great; the game which was swiftly to lead, if she could make it lead, across the sea and through France into Switzerland and then into the land of the enemy upon the Rhine—had caught her; and she knew instinctively how to reply to that as yet uncomprehended telegram from her father.

She reached for the dispatch blanks before she remembered that, though her handwriting would not be delivered in Decatur, still here she would be leaving a record in writing which was not like Cynthia Gail’s. So she merely took up the pen in her gloved fingers and gave it to Hubert Lennon who had not yet put his gloves on.

“You write for me, please,” she requested. “Mr. Charles F. Gail,” she directed and gave the home street number in Decatur. “Thanks for your wire telling me to go ahead. I knew you’d back me. Love. Thia.”

“What?” Lennon said at the last word.

“Just sign it ‘Thia.’”

He did so; she charged the dispatch to her room and they went out. The color was still warm in her face. If one of the men in the lobby was a German stationed to observe how she did and if he had seen her start the mistake of writing the telegram, he had seen also an instant recovery, she thought.

A large, luxurious limousine, driven by a chauffeur in private livery, moved up as they came to the curb. When they settled side by side on the soft cushions, the driver started away to the north without requiring instructions.

“You were fifteen years old when I last had a ride with you,” Hubert obligingly informed her.

That was nine years ago, in nineteen nine, Cynthia made the mental note; she had become twenty-four years old instead of twenty-two, since the morning.

“But I knew you right away,” he went on. “Aunt Emilie would have come for you but you see when she telephoned and found you weren’t in at half-past one, she knew she couldn’t call for you and get to Mrs. Corliss’ on time. And she’s a stickler for being on time.”

So it was to Mrs. Corliss’ they were going—to her great home on the drive. The car was keeping on northward along the snow-banked boulevard with the white and arctic lake away to the right and, on the left, the great grounds of Mrs. Potter Palmer’s home.

“She’d have sent a maid for you,” Hubert explained, “but I said it was stupid silly to send a maid after a girl who’s going into the war zone.”

“I’m glad you came instead for another ride with me,” Cynthia said.

He reddened with pleasure. In whatever circles he moved, it was plain he received no great attention from girls.

“I tried to get into army and navy both, Cynthia,” he blurted, apropos of nothing except that he seemed to feel that he owed explanation to her as to why he was not in uniform. “But they turned me down—eyes. Even the Canadians turned me down. But Aunt Emilie’s giving an ambulance; and they’re going to let me drive it. They get under fire sometimes, I hear. On the French front.”

“They’re often under fire,” Cynthia assured. “A lot of ambulance men have been killed and wounded; so that’s no slacker service.”

“Not if you can’t get in anything better,” he said, “but mighty little beside what Gerry Hull’s been doing.”

She startled a little. He had spoken Gerry Hull’s name with far less familiarity than Sam Hilton had uttered it that morning; but Hubert Lennon’s was with the familiarity of one who knows personally the man mentioned.

“You’ve seen him since he’s back?” Cynthia asked. It came to her suddenly that they—he and she—were going to meet Gerry Hull!

The car was slowing before the turn in the driveway for Mrs. Corliss’ city home; a number of cars were ahead and others took line behind for the porte cochère where guests were entering the house.

“Yes; I know him pretty well,” Hubert said with a sort of pitiful pride. He was sensitive to the fact that, when he had spoken of Gerry Hull, her interest in him had so quickened; but he was quite unresentful of it. “I’ll see that he knows you, Cynthia,” he promised.

She sat quiet, trying to think what to say to Hubert Lennon after this; but he did not want the talk brought back to himself. He spoke only of his friend until the man opened the door of the car; the house door was opened at the same moment; and Cynthia, gathering her coat about her and clutching close to her knitting bag, stepped out of the car and into the hall, warm and scented with hot-house flowers, murmurous with the voices and movement of many people in the big rooms beyond. A man servant directed her to a room where maids were in attendance and where she laid off her coat. She had never in her life been at any affair larger than a wedding or a reception to a congressman at Onarga; so it was a good deal all at once to find oneself a guest of Mrs. Corliss’, for it was plain that this reception was by no means a public affair but that the guests all had been carefully selected; it was more to be present carrying a knitting bag (fortunately many others brought knitting bags) in which were twenty-three hundred dollars and a passport to France; and something more yet to meet Gerry Hull—or rather, have him meet you. For when she came out to the hall again, Hubert was waiting for her.

“I can’t find Aunt Emilie just now, Cynthia,” he said. “But I’ve Gerry. There’s no sense in getting into that jam. We’ll go to the conservatory; and Gerry’ll come there. This way, Cynthia. Quick!”

She followed him about the fringes of the groups pressing into the great front room where a stringed orchestra was starting the first, glorious notes of the Marseillaise; and suddenly a man’s voice, in all the power and beauty of the opera singer and with the passion of a Frenchman singing for his people, burst out with the battle song:

It lifted her as nothing had ever before. “Go, children of your country; the day of glory is here! Against us the bloody standard of tyranny is raised!...”

She had sung that marvelous hymn of the French since she was a child; before she had understood it at all, the leap and lilt of the verse had thrilled her. It had become to her next an historical song of freedom; when the war started—and America was not in—the song had ceased to resound from the past. The victory of the French upon the Marne, the pursuit to the Aisne; then the stand at Verdun gave it living, vibrant voice. Still it had been a voice calling to others—a voice which Ruth might hear but to which she might not reply. But now, as it called to her: “Aux armes!... Marchons! Marchons!...” she was to march with it!

The wonder of that made her a little dizzy and set her pulse fluttering in her throat. The song was finished and she was amid the long fronds of palms, the hanging vines, and the red of winter roses in the conservatory. She looked about and discovered Hubert Lennon guiding Gerry Hull to her.

“Cynthia, this is Gerry Hull; Gerry, this is Cynthia Gail.”

He was in his uniform which he had worn in the French service; he had applied to be transferred from his old escadrille to an American squadron, Ruth knew; but the transfer was not yet effected. The ribbons of his decorations—the Croix de Guerre, the Médaille Militaire, the Cross of the Legion of Honor—ran in a little, brilliant row across the left breast of his jacket. It bothered him as her eyes went to them. He would not have sought the display—she thought—of wearing his decorations here at home; but since he was appearing in a formal—almost an official function—he had no choice about it. And she recognized instantly that he had not followed his friend out of the “jam” of the other rooms to meet her in order to hear more praise of himself from her.

He was, indeed, far more interested in her than in himself. “Why, I’ve met you before, Miss Gail,” he said, and evidently was puzzling to place her.

Ruth went warm with pleasure. “I spoke to you on the street—when your car stopped on Michigan Avenue this morning,” she confessed. She had not been Cynthia Gail, then; but he could not know that.

“Of course! And I said some stuffy sort of thing to you, didn’t I?”

“I didn’t think it—stuffy,” Ruth denied, utilizing his word. There were seats where they were; and suddenly it occurred to her, when he glanced at them, that he was remaining standing because she was, and that he would like to sit down, and delay there with her. She gasped a little at this realization; and she seated herself upon a gaily painted bench. He looked about before he sat down.

“Hello; I say, where’s Hub?”

Lennon had disappeared; and Ruth knew why. She had forgotten him in the excitement of meeting Gerry Hull; so he had felt himself in the way and had immediately withdrawn. But she could do nothing to mend that matter now; she turned to Gerry Hull, who was on the bench beside her.

He had more quickly banished any concern over his friend’s disappearance and was observing Ruth with so frank an interest that, instead of gazing away from her when she looked about at him, his eyes for an instant rested upon hers; his were meditative, almost wistful eyes for that moment. They made her think, suddenly, of the little boy whose picture with his grandfather she used to see in her father’s newspaper—an alert, energetic little boy, yet with a look of wonder in his eyes why so much fuss was made about him.

“I seem to’ve been saying no end of stuffy things since I’ve been back, Miss Gail; they appeared to be what I was expected to say. But I’m about at the finish of ’em. I’m to say something here this afternoon; and I’m going to say exactly what I think. Wouldn’t you?”

“Of course I would,” Ruth said.

“Then you forgive me?”

“For what?”

“Posing like such a self-righteous chump in a cab that you felt you ought to ask me what you should do!”

“You haven’t been posing,” Ruth denied for him again. “Why, when I saw you, what amazed me was that—” she stopped suddenly as she saw color come to his face.

“That I wasn’t striking an attitude? Look here, I’m—or I was—one man in fifty thousand in the foreign legion; and one in thousands who’ve been in the air a bit. I’d no idea what I was getting into when they told me to come home here or I’d—” he stopped and shifted the subject from himself with abrupt finality. “You’re going to France, Hub tells me. You’ve been there in peacetime, of course—Paris surely.”

Ruth nodded. She had not thought that, as Cynthia, she must have been abroad until he was so certain of it.

“Did you ever go about old Paris and just poke around, Miss Gail?”

“In those quaint, crooked little streets which change their names every time they twist?”

“The Rue des Saints Pères, the Rue Pavée—that name rather takes one back, doesn’t it? Some time ago it must have been when in Paris a citizen could describe where he lived by saying it was on ‘the paved street.’”

“Yet it was only in the fifteenth century that wolves used to come in winter into Paris.”

“To scare François Villon into his Lodgings for a Night?” Gerry said. “So you know that story of Stevenson’s, too?”

“Yes.”

“I suppose, though, you had to stay at the Continental, or the Regina, or some hotel like that, didn’t you? I did at first, when my tutor used to take me. You’d have been with your parents, of course——”

“Of course,” Ruth said.

“But have you planned where you’ll stay now? You’ll choose your own billets, I believe.”

Ruth appealed to her memories of Du Maurier and Victor Hugo; she had read, long ago, Trilby and Les Misérables, of course, and Notre-Dame de Paris; and she knew a good bit about old Paris.

“The Latin Quarter’s cheapest, I suppose.”

“And any amount the most sport!”

She got along very well; or he was not at all critical. He was relaxing with her from the strain of being upon exhibition; and he seemed to be having a very good time. The joy of this made her bold to plan with him all sorts of explorations of Paris when they would meet over there with a day off. She looked away and closed her eyes for a second, half expecting that when she opened them the sound of music, and the roses, and palms, and conservatory, and Gerry Hull must have vanished; but he was there when she glanced back. And she noticed agreeable and pleasing things about him—the way his dark hair brushed back above his temples, the character in his strong, well-formed hands.

She looked away, half expecting the sound of the music, and the roses, and palms, and Gerry Hull would vanish

Lady Agnes came out looking for him; and he called her over:

“Oh, Agnes, here we are!”

So Ruth met Lady Agnes, too; but Lady Agnes took him away, laughingly scolding him for having left her so long alone among all those American people. Ruth did not follow; and while she lingered beside the bench where he had sat with her, she warned herself that Gerry Hull had paid her attention as a man of his breeding would have paid any girl whom he had been brought out to meet. Then the blood, warm within her, insisted that he had not disliked her; he had even liked her for herself.

The approach of an elderly woman in a gray dress returned Ruth to the realities and the risks of the fraud she had been playing to win Gerry Hull’s liking. For the woman gazed at her questioningly and swiftly came up.

Ruth arose. Was this Hubert Lennon’s “Aunt Emilie?” she wondered. Had she recently seen the real Cynthia so that she was aware that Ruth was not she?

No; the woman was calling her Cynthia; and with the careful enunciation of the syllables, Ruth recognized the voice as that which had addressed her over the telephone when she was in her room at the hotel.

“Cynthia, you are doing well—excellently!” This could refer only to the fact that she had met Gerry Hull already and had not displeased him. “Develop this opportunity to the utmost; you may find him of greatest possible use when you are in France!”

The woman immediately moved away and left the conservatory. No one could have observed her speaking to Ruth except, perhaps, Hubert Lennon, who now had reappeared and, finding Ruth alone, offered his escort shyly. If he had noticed and if he wondered what acquaintance Cynthia had happened upon here, he did not inquire.

“We’d better go into the other rooms,” he suggested. “They’re starting speeches.”

She accompanied him, abstractedly. Whatever question she had held as to whether the Germans held her under surveillance had been answered; but it was evident that so far, at least, her appearance in the part of Cynthia Gail had satisfied them—indeed, more than satisfied. What beset Ruth at this moment was the fact that she now knew the identity of an unsuspected enemy among the guests in this house; but she could not accuse that woman without at the same time involving herself. It presented a nice problem in values; Ruth must be quite confident that she possessed the will and the ability to aid her side to greater extent than this woman could harm it; or she must expose the enemy even at the cost of betraying herself.

She looked for the woman while Hubert led her through the first large room in the front of the big house, where scores of guests who had been standing or moving about were beginning to find places in the rows of chairs which servants were setting up. Hubert took Ruth to a small, nervously intent lady with glistening black hair and brows, who was seated and half turned about emphatically conversing with the people behind her.

“Aunt Emilie, here’s Cynthia,” Hubert said loudly to win her attention; she looked up, scrutinized Ruth and smiled.

“I had to help Mrs. Corliss receive, dear; or I’d have called for you myself. So glad Hubert has you here.”

Ruth took the hand which she outstretched and was drawn down beside her. Aunt Emilie (Ruth knew no name for her in relation to herself and therefore used none in her reply) continued to hold Ruth’s hand affectionately for several moments and patted it with approval when at last she let it go. Years ago she had been a close friend of Cynthia Gail’s mother, it developed; Julia Gail had written her that Cynthia was in Chicago on her way to France; Aunt Emilie had asked Mrs. Corliss to telephone to Cynthia on Saturday inviting her here; Aunt Emilie herself had telephoned on Sunday and Monday to the hotel to find Cynthia, but vainly each time.

“Where in the world were you all that time, my dear child?”

A man’s voice suddenly rose above the murmur in the room. The man was standing upon a little platform toward which the chairs were faced and with him were an officer in the uniform of the French Alpine chasseurs, Lady Agnes Ertyle, and Gerry Hull. For an instant the start of the speaking was to Ruth only a happy interruption postponing the problem of explanations to “Aunt Emilie”; but the next minute Ruth had forgotten all about that small matter. Gerry Hull, from his place on the platform, was looking for her.

The French officer, having been introduced, had commenced to address his audience in emphatic, exalted English; the others upon the platform had sat down. Gerry Hull’s glance, which had been going about the room studying the people present, had steadied to the look of a search for some special one; his eyes found Ruth and rested. She was that special one. He looked away soon; but his eyes had ceased to search and again, when Ruth glanced directly at him, she found him observing her.

She leaned forward a little and tried not to look toward him or to think about him too much; but that was hard to do. She had recognized that, when Hubert Lennon had summoned Gerry Hull out to the conservatory, something had been troubling him and he had been on the brink of a decision. He had met her during the moments when he must decide and, in a way, he had referred the decision to her. “They’re going to make me say something here this afternoon; and this time I’m going to say exactly what I think. Wouldn’t you?”

She had told him that she would, without knowing at all what it was about. Now it seemed to her that, as his time for speaking approached, he was finding his determination more difficult.

The French officer was making an extravagant address, praising everyone here and all Americans for coming into the war to save France and civilization; he was complimenting every American deed, proclaiming gratitude in the name of his country for the aid which America had given; and, while he was speaking thus excessively, Ruth was aware that Gerry Hull was watching her most intently; and when she glanced up at him she saw him draw up straighter in his chair and sit there, looking away, with lips tight shut. The French officer finished and, after the applause, Lady Agnes Ertyle was introduced and she spoke earnestly and simply, telling a little of the work of Americans in Belgium and in France, of the great value of American contributions and moral support; she added her praise and thanks for American aid.

It seemed to Ruth that once Gerry Hull was about to interrupt. But he did not; no one else appeared to notice his agitation; everyone was applauding the pretty English girl who had spoken so gracefully and was sitting down. The gentleman who was making the introductions was beginning to relate who Gerry Hull was and what he had done, when Gerry suddenly stood up. Everyone saw him and clapped wildly; the introducer halted and turned; he smiled and sat down, leaving him standing alone before his friends.

Men here and there were rising while they applauded and called his name; other men, women, and girls got to their feet. Hubert Lennon, on Ruth’s left, was one of the first to stand up; his aunt was standing. So Ruth arose then, too; everyone throughout the great rooms was standing now in honor of Gerry Hull. He gazed about and went white a little; he was looking again for someone lost in all the standing throng; he was looking for Ruth! He saw her and studied her queerly again for a moment. She sat down; others began settling back and the rooms became still.

“I beg your pardon,” Ruth heard Gerry Hull’s voice apologizing first to the man who had tried to introduce him. “I beg the pardon of you all for what I’m going to say. It’s not a word of what I’m supposed to say, I know; it’ll be just what I think and feel.

“We’re not doing our part, people!” he burst out passionately without more preparation. “We’re still taking protection behind England and France, as we’ve done since the start of the war! We ought to be there in force now! God knows, we ought to have been there in force three years ago! But instead of being on the battle line with them in force even with theirs, our position is so pitiable that we make our allies feel grateful for a few score of destroyers and a couple of army divisions holding down quiet sectors in Lorraine. That’s because our allies have become so used to expecting nothing—or next to nothing—of America that anything at all which we do fills them with such sincere amazement that they compliment and overwhelm us with thanks of the sort you have heard.”