Title: Sasha the serf, and other stories of Russian life

Author: Anonymous

Release date: July 29, 2022 [eBook #68643]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: Blackie & Son

Credits: Al Haines

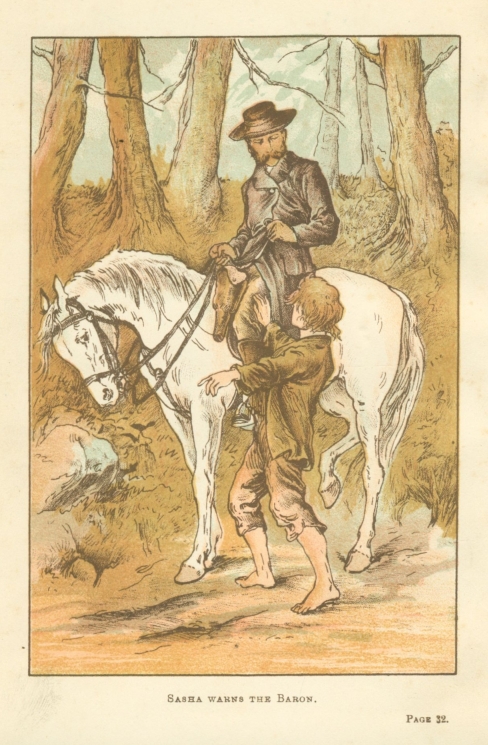

Sasha warns the Baron. Page 32

AND

OTHER STORIES OF RUSSIAN LIFE.

LONDON:

BLACKIE & SON, 49 OLD BAILEY, E.C.;

GLASGOW, EDINBURGH, AND DUBLIN.

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER I.

It was towards the close of a September day. Old Gregor and his grandson Sasha were returning home through the forest with their bundles of wood, the old man stooping low under the weight of the heavier pieces he carried, while the boy dragged his great bunch of twigs and splints by a rope drawn over his shoulder. Where the trees grew thick the air was already quite gloomy, but in the open spaces they could see the sky and tell how near it was to sunset.

Both were silent, for they were tired, and it is not easy to talk and carry a heavy load at the same time. But presently something gray appeared through the trees at the foot of a low hill; it was the rock where they always rested on their way home. Old Gregor laid down his bundle there, and wiped his face on the sleeve of his brown jacket, but Sasha sprang upon the rock and began to balance himself upon one foot, as was his habit whenever he tried to think about anything.

"Grandfather," he said at last, "why should all this forest belong to the baron, and none of it to you?"

Gregor looked at him sharply for a moment before he answered.

"It was his father's and his grandfather's: it has been the property of the family for many a hundred years, and we never had any."

"I know that, grandfather," said Sasha. "But why did it come so at first?"

Gregor shook his head. "You might as well ask how the world was made." Then, seeing that the boy looked troubled, he added in a kinder tone, "Sasha, what put such a thought into your head?"

"Why, the forest itself!" replied the boy. "The baron lets us have the top branches and little twigs, but he takes all the great logs and trunks, and sells them for money. I know all the trees, and he does not; I can find my way in the woods anywhere, and there's many a tree that would say to me, if it could talk, 'I'd rather belong to you, Sasha, than to the baron, because I know you, and I don't know him.'"

"Ay, and the moon would say the same to you, boy, and the sun and the stars, maybe. You might as well want to own them—and you don't even belong to yourself!"

Gregor's words seemed harsh and fierce, but his voice was very sad. The boy looked at him and knew not what to say, but his heart beat violently. All at once he heard a rustle among the dead leaves, and a sound as if of footsteps approaching. The old man took hold of his grandson's arm, and made a sign for him to be silent. The sound came nearer and nearer, and presently they could distinguish some dusky object moving towards them through the trees.

"Is it a robber?" whispered the boy.

"It is not a man, unless he uses his knees for hind feet. I see his head; it is a bear. Keep quiet, boy! make no noise: take this stick, but hold it at your side as I do mine. If he comes close, look him firmly in the face; and if I tell you to strike, hit him on the end of the nose."

It was indeed a full-grown bear, marching slowly on his great flat feet. He was not more than thirty yards distant when he saw them, and stopped. Both kept their eyes fixed upon his head, but did not move. Then he came a few paces nearer, and Sasha tried hard not to show that he was trembling inwardly, more, however, from excitement than fear. The bear gazed steadily at them for what seemed a long time, and there was an expression of anger, but also of stupid bewilderment, in his eyes. Finally he gave a sniff and a grunt, tossed up his nose, and walked slowly on, stopping once or twice to turn and look back before he disappeared from view. Sasha lifted his stick and shook it at him. He felt that he should never again be much afraid of bears.

"Now, boy," said his grandfather, "you have learned how to face danger. I have been as near to a loaded cannon as to that bear, and the wind of the ball threw me upon my face: but I was up the next moment, and then the gunner went down! Our colonel saw it, and I remember what he said—ay, every word! He would have kept his promise, but we carried him from the field next day, and that was the end of the matter. It was in France that it happened."

"Grandfather," asked the boy suddenly, "are there forests in France, and do they belong to barons?"

"Pick up your faggot, boy, and come along!" said Gregor. "It will be dark before we get to the village, and the potatoes are cooked by this time."

The mention of the potatoes revived all Sasha's forgotten hunger, and he obeyed in silence. After walking for a mile as rapidly as their loads would permit them, they issued from the forest, and saw the wooden houses of the village on a green knoll, in the last gleams of sunset. The church, with its three little copper-covered domes, stood on the highest point. Next to it the priest's house and garden, and then began the broad street, lined with square log-cabins and adjoining stables, sloping down to a large pond, at the foot of which was a mill. Beyond the water there was a great stretch of grazing meadow, then long rolling fields of rye and barley, extending to the woods which bounded the view in every direction. The village was situated within a few miles of the great main highway running from Warsaw to Moscow, and the waters of the lake fed the stream which flowed into one of the branches of the river Dnieper.

The whole region, including the village and nearly all the people in it, belonged to the estate of Baron Popoff, the roofs of whose residence were just visible to the southward, on a hill overlooking the road to Moscow. The former castle had been entirely destroyed during the retreat of Bonaparte's army, and the baron's grandfather suffered so many losses at the time, that he was only able to build a large and very plain modern house; but the people continued to call it the "Castle" or "Palace," just as before.

Although the baron sold every year great quantities of timber, grain, hemp and wool from his estates, he always seemed to be in want of money. The servants who went with him every year to St. Petersburg were very discreet, and said little about their master's habits of life; but the people understood, somehow, that he often lost large sums by gambling. This gave them a good deal of uneasiness, for if he should be obliged to part with the estate, they would all be transferred with it to a new owner—and this might be one who had other estates in a different part of the country, to which he could send them if he was so minded.

At the time of which we are writing twenty-two millions of the Russian people were serfs. Their labour, even their property, belonged to the owner of the land upon which they lived. The latter had not the power to sell them to another, as was formerly the case in the Southern States of America, but he could remove them from one estate to another if he had several. Baron Popoff was a haughty and indifferent master, but not a cruel one; the people of the village had belonged to his family for several generations, and were accustomed to their condition. At least, they saw no way of changing it, except by a change of masters, which was more likely to be a misfortune than a benefit.

It was nearly dark when old Gregor and his grandson threw down their loads and entered the house. The supper was already waiting, for Sasha's sister, little Minka, had been up to the church door to see whether they were coming. In one corner of the room a tiny lamp was burning before a picture of the Virgin Mary and Child Jesus, all covered with gilded brass except the hands and faces, which were nearly black, partly from the smoke, and partly because the common Russian people imagine that the Hebrews were a very dark-skinned race. Sasha's father, Ivan, had also lighted a long pine-splint, and the room looked very cheerful. The boiled potatoes were smoking in a great wooden bowl, beside which stood a dish of salt, another of melted fat, and a loaf of black bread. They had neither plates, knives nor forks, only some coarse wooden spoons, and all ate out of the bowl, after the salt had been sprinkled and the fat poured over the potatoes. For drink there was an earthen pitcher of quass, a kind of thin and rather sour beer.

Old Gregor sat on one side of the table, and his son Ivan with Anna, his wife, opposite. There were five children, the eldest being Alexander (whom we know by his nickname "Sasha," which is the Russian for "Aleck" or "Sandy"), then Minka, Peter, Waska, and Sergius. Sasha was about thirteen years old, rather small for his age, and hardly to be called a handsome boy. Only there was something very pleasant in his large gray eyes, and his long, thick flaxen hair shone almost like silver when the sun fell upon it. However, he never thought about his looks. When he went to the village bath-house, on a Saturday evening, to take his steam-bath with the rest, the men would sometimes say, after examining his joints and muscles, "You are going to be strong, Sasha!"—and that was as much as he cared to know about himself.

The boy was burning with desire to tell the adventure with the bear, but he did not like to speak before his grandfather, and there was something in the latter's eye which made him feel that he was watching him. Gregor first lighted his pipe, and then, in the coolest manner possible—as if it were something that happened every day—related the story.

"Pity I hadn't your gun with me, Ivan," he said at the close; "what with the meat, the fat, and the skin, we should have had thirty roubles."

The children were quite noisy with excitement. Little Peter said, "What for did you let him go, Sasha? I'd have killed him, and carried him home!" Then all laughed so heartily that Peter began to cry, and was soon packed into a box in the corner, where he was soon as fast asleep as ever was the proverbial door-nail.

"Take the gun with you to-morrow, father." said Ivan.

"It's too much with my load of wood," answered the old man. "The old hunting-knife is all I want. Sasha will stand by me with a club: I don't think he'll be afraid next time."

Sasha was about to exclaim, "I was not afraid the first time!" but before he spoke it flashed across his mind that he did tremble a little; but he consoled himself a little that it was not from fear.

By this time it was dark outside. Two pine-splints had burned out, one after the other, and only the little lamp before the shrine enabled those present to see each other. The old people went to bed in their narrow rooms, which were hardly better than closets; and Sasha, spreading a coarse sack of straw on the floor, lay down, covering himself with his sheepskin coat, and in five minutes was so sound asleep that he might have been dragged about by the heels without being awakened.

CHAPTER II.

Next day in the forest old Gregor worked more rapidly than usual. He spoke very little, in spite of Sasha's eagerness to talk, and kept the boy so busy that all the wood was gathered up and made into bundles two or three hours before the usual time.

They were in a partially cleared spot, near the top of some rising ground. The old man looked at the sky, nodded his head, and said with a satisfied air, "We have plenty of time left for ourselves, Sasha; come with me, and I'll show you something."

Gregor then set out in a direction opposite from home, and the boy, who expected nothing less than the finding of another bear, seized a tough straight club, and followed him. They went for nearly a mile over rolling ground through the forest, and then descended into a narrow glen, at the foot of which ran a rapid stream. Very soon rocks began to appear on both sides, and the glen became a chasm where there was barely room to walk. It was a cold, gloomy, strange place; Sasha had never seen anything like it. He felt a singular creeping of the flesh, but not for the world would he have turned back.

The path ceased, and there was a waterfall in front filling up the whole chasm. Gregor pulled off his boots and stepped into the stream, which reached nearly to his knees; he gave his hand to Sasha, who could hardly have walked alone against the force of the current. They reached the foot of the fall, the spray of which was whirled into their faces. Then Gregor turned suddenly to the left, passed through the thin edge of the falling water, and Sasha, pulled after him, found himself in a low arched vault of rock, into which the light shone down from another opening. They crawled upwards on hands and knees, and came out into a great circular hole, like a kettle, through the middle of which ran the stream. There was no other way of getting into it, for the rocks leaned inward as they rose, making the bottom considerably wider than the top.

On one side, under the middle of the rocky arch, stood a square black stone about five feet high, with a circle of seven smaller stones resembling seats around it. Sasha was dumb with surprise at finding himself in such a wonderful spot.

But old Gregor made the sign of the cross, and muttered something which seemed to be like a prayer. Then he went to the black stone, and put his hand upon it.

"Sasha," he said, "this is one of the places where the old Russian people came many thousand years ago, before ever the name of Christ was heard of. They were dreadful heathens in those days, and this place was what served them for a church. A black stone had to be the altar, because they had a black god, who was never satisfied unless they fed him with human flesh."

"Where is the black god now?" asked Sasha.

"They say he has turned into an evil spirit, and is hiding somewhere in the wilderness; but I cannot say for the truth of it. His name was Perun. Most men do not care to say it, but I have the courage, because I've been a soldier and have an honest conscience. Are you afraid to stand here?" asked Gregor inquiringly.

"Not if you are not, grandfather," answered Sasha, bravely but respectfully.

"If your heart were bad and false, Sasha, you would have reason to be afraid; but as I know it is not, you can come here without fear of danger."

Sasha obeyed. The old man opened the boy's coarse shirt and laid his hand upon his heart; then he made him do the same to himself, so that the heart of each beat directly against the hand of the other.

"Now, boy," said Gregor, after a pause, "I am going to trust you, and if you say a word you do not mean, or think otherwise than you speak, I shall feel it in the motion of your heart. Do you know the difference between a serf and a free-man? Would you rather live like your father, having nothing that he can call his own, or would you live like the Baron Popoff, with wealth, and houses, and lands, and forests, and people, that no one could take from you, except, perhaps, the emperor?"

Sasha's heart gave a great thump before he could open his mouth. The old man smiled, and he said to himself, "I was right." Then he continued: "I should be a free man now, if our colonel had lived. Your father had not wit and courage enough to try, but you can do it, Sasha, if you think of nothing else and work for nothing else. I will help you all I can; but you must begin at once. Will you?"

"Yes, grandfather, yes!" exclaimed Sasha eagerly.

"Promise me that you will say nothing to any living person; that you will obey me and remember all I say to you while I live, and be none the less faithful to the purpose when I am dead!"

Sasha promised everything at once. After a moment's silence Gregor took his hand from the boy's breast, and said:

"Yes, you truly mean it. The people of old used to say that if any one broke a promise made before this stone, the black heathen god would have power over him."

"Perhaps the bear was the black god," suggested Sasha.

"Perhaps he was. Look him in the face, as you did yesterday, remember your promise, and he can't harm you."

As they walked back slowly through the forest Gregor began to talk, and the boy kept close beside him, listening eagerly to every word.

"The first thing, Sasha," said he, "is to get knowledge. You must learn, somehow, to read and write, and count figures. I must tell you all I know, about everything in the world, but that's very little; and it is so mixed up in my head that I don't rightly know where to begin. It's a blessing I have not forgotten much; what I picked up I held on to, and now I see the reason why. There's nothing you can't use, if you wait long enough."

"Tell me about France!" cried Sasha.

"France and Germany too! I was two or three years, off and on, in those foreign parts, and I could talk smartly in the speech of both—Allez! Sortez! Donnez moi du vin!"

Gregor stopped and straightened his bent back; his eyes flashed, and he laughed long and heartily.

"Allez! Sortez! Donnez moi du vin!" repeated Sasha.

Gregor caught up the boy in his arms and kissed him.

"The very thing, Sasha!" he cried. "I'll teach you both tongues,—and all about the strange habits of the people, their houses, and churches, and which way the battle went, and what queer harness they have on their horses, and a talking bird I once saw, and a man that kept a bottle full of lightning in his room, and—"

So his tongue ran on. It was a great delight to him to recall his memories of more than thirty years, and he was constantly surprised to find how many little things that seemed forgotten came back to his mind. Sasha's breath came quick as he listened; his whole body felt warm and nimble, and it suddenly seemed to him possible to learn anything and everything. Before reaching home he had fixed twenty or thirty French words in his memory. There they were, hard and tight; he knew he should never forget them.

From that day began a new life for both. Old Gregor's method of instruction would simply have confused a pupil less ignorant and eager to be taught; but Sasha was so sure that knowledge would in some way help him to become a free man, that he seized upon everything he heard. In a few months he knew as much German and French as his grandfather, and when they were alone they always spoke, as much as possible, in one or the other language. But the boy's greatest desire was to learn how to read. During the following winter he made himself useful to the priest in various ways, and finally succeeded in getting from him the letters of the alphabet and learning how to put them together. Of course he could not keep secret all that he did; it was enough that no one guessed his object in doing it.

One day in the spring, just after the baron had returned with his wife from St. Petersburg, Sasha was sent on an errand to the castle. He was bare-headed and bare-footed; his shirt and wide trousers were very coarse, but clean, and his hair floated over his shoulders like a mass of shining silk. When he reached the castle the baron and baroness, with a strange lady, were sitting in the balcony. The latter said, in French, "There's a nice-looking boy!"

Sasha was so glad to find that he understood, and so delighted with the remark, that he looked up suddenly and blushed.

"I really believe he understands what I said," exclaimed the lady.

The baron laughed. "Do you suppose my young serfs are educated like princes?" he asked.

"If he were so intelligent as that, how long could I keep him?"

Sasha bent down his head, and kicked the loose pebbles with his feet to hide his excitement. The blood was humming in his ears: the baron had said the same thing as his grandfather had said—to get knowledge was the only way to get freedom!

CHAPTER III.

The summer passed away, and the second autumn came. Gregor had told all he knew; told it twice, three times; and Sasha, more eager than ever, began to grow impatient for something more. He had secured a little reading-book, such as is used for children, and studied it until he knew the exact place of every letter in it, but there was no one to give the poor boy another volume, or to teach him any further.

One afternoon, as he was returning alone from a neighbouring village by a country road which branched off from the main highway, he saw three men sitting on the bank under the edge of a thicket. They were strangers, and they seemed to him to be foreigners. Two were of middle age, with harsh, evil faces; the third was young, and had an anxious frightened look. They were talking earnestly, but before he could distinguish the words, one of them saw him, made a sign to the others, and then he was very sure that they suddenly changed their language; for it was German he now heard.

He felt proud of his own knowledge, and his first thought was to say "Good-day!" in German. Then he remembered his grandfather's counsel, "Never display your knowledge until there is a good reason for it," and gave his greeting in Russian. The young man nodded his head in return; the others took no notice of him. But in passing he understood these sentences:—

"He will carry a great deal of money.... There's no danger—he will be alone.... Grain and hemp both sold to-day.... It will be already dark."

Just beyond the thicket the road made a sharp turn and entered the woods. Sasha never afterwards could quite explain the impulse which led him to dart under the trees as soon as he was out of sight, to get in the rear of the thicket, crawl silently nearer on his hands and knees, and then lie down flat within hearing of the men's voices. For a moment he was overcome with a horrible fear. They were silent, and his heart beat so loudly that he thought they could no more help noticing it than the sound of a blacksmith's hammer.

Presently one of them spoke, this time in Russian.

"There is a hill from which you can see both roads," he said, "but he'll hardly take the highway."

"Are you sure his groom was not in the town along with him?" asked another.

"It's all as I say—rely upon that!" was the answer. "For all his titles he's no more than another man, and we are three!"

In talking further they mentioned the name of the town; it was the place only a few miles distant where the grain, hemp, and other products of the estate were sold to traders—and this was the day of the sale! The plot of the robbers flashed into Sasha's mind; and if he had had any remaining doubts, they were soon removed by his hearing the name of Baron Popoff mentioned. The latter was to be waylaid, plundered, killed if he resisted. Then the eldest of the three men said, as he got up from the bank where they had been sitting:

"We must be on the way. Better be too early than too late."

"But it's a terrible thing," remarked the youngest.

"You can't turn back now!" said the other angrily.

Sasha waited until he could no longer hear their footsteps. Then he started up, and, keeping away from the road they had taken, ran through the woods and thickets in the direction of the town. His only thought was, to reach the hill the robbers had mentioned, from which both roads could be seen. He knew it well; there was a bridle-path, shorter than the main highway, and the baron would probably take it, as he was on horseback. The hill divided the two roads; it was covered with young birch-trees, which grew very thickly on the summit and almost choked up the path. But there was a long spur of thicket, he remembered, running out on the ridge, and whoever stood at the end of it could almost look into the town.

Sasha was so excited that he took a track almost as short as a bird flies. He tore through bushes and brambles without thinking of the scratches they gave him; he leaped across gullies, and ran at full speed over open fields; he was faint, and bruised, and breathless, but he never paused until the farthest point of the thicket on the hill was reached. It was then about an hour before sunset, and only one or two travellers on foot were to be seen upon the highway. The town was half a mile off, but he could plainly see where the bridle-track issued from a little lane between the houses. Carefully concealing himself under a thick alder-bush, he kept his eyes fixed upon that point.

He was obliged to wait for what seemed a long, long time. The sun was just setting when, finally, a horseman made his appearance, and Sasha knew by the large white horse that it must be the baron. The rider looked at his watch, and then began to canter along the level towards the hill. There was no time to lose; so, without pausing a moment to think, Sasha sprang from his hiding-place, and darted down the grassy slope at full speed, crying:

"Lord Baron! Lord Baron!"

The rider, at first, did not seem to heed. He cantered on, and it required all Sasha's remaining strength to reach the path in advance of him. Then he dropped upon his knees, lifted up his hands, and cried once more:

"Stop, Lord Baron!"

The baron reined up his horse just in time to avoid trampling on the boy. Sasha sprang to his feet, seized the bridle, and gasped, "The robbers! the robbers!"

"Who are you?—and what does this mean?" asked the baron in a stern voice.

But Sasha was too much in earnest to feel afraid of the great lord. "I am Sasha, the son of Ivan, the son of Gregor," he replied; and then related as rapidly as he could all that he had seen and heard.

The baron looked at his pistols.

"Ha!" he cried, "the caps have been taken off! You may have done me good service, boy. Wait here: it is not enough to escape the rascals; we must capture them!"

He turned his horse, and galloped back at full speed towards the town. Sasha watched him, thinking only that he was saved at last. It was growing dark when the boy's quick ear caught the sound of footsteps in the opposite direction. He turned and saw the three men approaching rapidly. With a deadly sense of terror he started and ran towards the town.

"Kill the little spy!" shouted behind him a voice which he well knew.

Sasha cried aloud for help as he ran, but no help came. He was already weak and exhausted from the exertion he had made, and he heard the robbers coming nearer and nearer. All at once it seemed to him that his cries were answered; but at the same moment a heavy blow came down upon his head and shoulder. He fell to the ground, and knew no more.

CHAPTER IV.

When Sasha came to his senses it seemed to him that he must have been dead for a long time. First of all, he had to think who he was; and this was not so easy as you may suppose, for he found himself lying in bed in a room he had never seen before. It was broad daylight, and the sun shone upon one of his hands, which was so white and thin that it did not seem to belong to him. Then he lifted it, and was amazed to find how little strength there was in his arm. But he brought it to his head at last—and there was another surprise. All his long silken hair was gone! He was so weak and bewildered that he groaned aloud, and the tears ran down his cheeks.

There was a noise in the room, and presently old Gregor, his grandfather, bent over him as he lay in bed.

"Grandfather," said the boy—and how feeble his voice sounded—"am I your Sasha still?"

The old man, crying for joy, dropped on his knees and uttered a short prayer. "Now you will get well!" he cried; "but you mustn't talk; the doctor said you were not to talk."

"But where am I, grandfather?" asked Sasha.

"In the palace! And the baron's own doctor comes every day to see you; and they allow me to stay here and nurse you—it will be a week to-morrow!"

"What's the matter—what has happened?"

"Don't talk, for the love of heaven!" said Gregor; "you saved the baron from being robbed and killed; and the principal robber struck your head and broke your arm; and the baron and the people came just at the right time; and one of them was shot, and the other two are in prison. O, my boy, remember the altar of the black god Perun; be obedient to me; shut your eyes and keep quiet!"

But Sasha could not shut his eyes. Little by little his memory came back, and a sense of what he had done filled his mind and made him happy. He felt a dull ache in his left arm, and found that it was so tightly bandaged he could not move it, as he lay quite still, while his grandfather sat and watched him with sparkling eyes. After a time the door opened and a strange gentleman came in; it was the doctor. The old man rose and conversed with him in whispers. Then Sasha found that a spoon was held to his lips; he mechanically swallowed something that had a strange, pleasant taste, and almost immediately fell asleep.

In a day or two he was strong enough to sit up in bed, and was allowed to talk. Then the baron and the baroness came with the lady who was their guest, to see him. They were all eager to learn the particulars of the occurrence, especially how Sasha had discovered the plot of the robbers. He began at the beginning, and had got as far as the latter's change of language on seeing him, when he stopped in great confusion, and looked at his grandfather.

Gregor neither spoke nor moved, but his eyes seemed to say plainly, "Tell everything."

Sasha then related the whole story to the end. The baroness came to the bedside, stooped down, kissed him, and said, "You have saved your lord!"

But the other lady, who had been watching him very closely and curiously, suddenly exclaimed:

"Why, it's the same nice-looking young serf that I saw before; and when I spoke of him in French he blushed. I was sure he understood me! Don't you understand me now, my boy?"

She asked the question in French, and Sasha answered in the same language, "Yes, madam."

The lady clapped her hands with delight; but the baron asked very sternly:

"Where did you learn so many languages?"

"From me!" answered Gregor, instantly. "The boy likes to know things, and I've always thought—saving your opinion, my lord—that when God gives anyone a strong wish for knowledge he means it to be answered. So I opened to him all there is in this foolish old head of mine while we were together in the forest; and it was such a pleasure for him to take that it came to be a pleasure for me to give. You understand, my lady?"

"Yes," said the baroness, "I understand that without Sasha's knowledge of German my husband would probably have been murdered."

"That's not so certain," replied the baron. "But some celebrated man has said, 'All's well that ends well.' The boy did his duty like a full-grown man, and I'll take care of him."

Therewith they went out of the room, and Sasha immediately asked in some anxiety, "Grandfather, you meant that I should tell?"

"Yes, my boy," said Gregor readily, "for the youngest robber has already confessed that they spoke in German, and thought themselves safe while you were passing. They are vagabonds from the borders of Poland, and knew a little of three or four tongues. It is all right, Sasha; the baron is satisfied, and means to help you. Your chance has come sooner than I expected. I must have a little time to think about it; my head is like a stiff joint, hard to bend when I want to use it. It's a piece of good luck to me that you can't get out of bed for a week to come!"

He laughed as he left the bedside and took his seat on the broad stone bench beside the fireplace. Sasha kept silent, for he knew that the old man's brain was hard at work. He tried to do a little thinking himself, but it made him feel weak and giddy; in fact, the blow upon his head would have killed a more delicate boy.

His strength came back so rapidly, however, that in a week he was able to walk about with his arm in a sling. He was still pale, and looked so strange in his short hair that on his first visit home his mother burst into tears on seeing him. Then Minka, Peter, Sergius, and Waska lifted up their voices and cried; and Ivan, who was at first angry with them, finally cried also, without knowing why he did it. All this made Sasha feel very uncomfortable, and he was on the point of saying, "I won't do it again!" when Old Gregor made silence in the house. He had looked through the window and seen some of the neighbours coming; so the whole family became cheerful again as rapidly as they could.

By this time Gregor had made up his mind. Sasha knew that he could not change it if he would, and he was therefore very glad to find how well his grandfather's notions agreed with his own. While he was waiting for the baron to speak again he was not losing time; for the strange lady who was visiting at the castle took quite a friendly interest in teaching him French and German, and giving him Russian books which were not too difficult to read. He was so eager to satisfy her that he really made astonishing progress.

When the robbers were tried before the judge he was called upon to give testimony against them. One of the three having been killed, the youngest one was not afraid to confess, and his story and Sasha's agreed perfectly. The boy described the unwillingness of the former to undertake the crime; even the baron said a word in his favour, and the judge at last sentenced him to be banished to Siberia for only ten years, while the older robber was sent there for life.

That evening the baron asked Sasha, "Would you like to be one of my house-servants, boy?"

Just as his grandfather had advised him, Sasha answered, "It is not for me to choose, my lord; but I think I can serve you much more to your profit if you will let me try to become a merchant."

"A merchant!" exclaimed the baron.

"Not all at once," said Sasha. "I could be of use now as a boy to help carry and sell things, because I can count, and speak a little in other tongues. I could make myself so useful to some merchant that he would give me a chance to learn the whole business in time. Then I should earn much money, and could pay you for the privilege."

The baron had often envied noblemen of his acquaintance, some of whose serfs were rich manufacturers or merchants, and paid them large annual sums for the privilege of living for themselves. Here seemed to be a chance for him to gain something in the same way. The boy spoke so confidently, and looked in his face with such straightforward eyes, that he felt obliged to consider the proposition seriously.

"How will you get to St. Petersburg?" he asked.

"When you go, my lord," said Sasha, "I could sit on the box at the coachman's feet. I will help him with the horses, and it shall cost you nothing. When I get there I know I shall find a place."

The baron then said, "You may go."

CHAPTER V.

Here, as a boy not yet fifteen, Sasha begins his career as a man. The task he has undertaken demands the industry, the patience, and the devotion of his life; but he has been prepared for it by a sound if a somewhat hard experience. I hope the boys who read this feel satisfied already that he is going to succeed; yet I know also that they like to be certain, and to have some little information as to how it came about. So I will allow fifteen years to pass, and we will now look upon Sasha as a man of about thirty years of age.

He has an office and warehouse on the great main street of St. Petersburg, which is called the Nevsky Prospekt, that is, the Perspective of the Neva, because when you look down it you see the blue waters of the river Neva at the end. Over the door there is a large sign-board with the name "Alexander Ivanovitch."[1] He employs a number of clerks and salesmen, and has a servant who would go through fire and water to help or serve him. I must relate how he found this man, and why the latter is so faithful.

[1] Ivanovitch means "the son of Ivan." Russian family names are formed in this manner, and therefore the son has a different name from the father, unless their baptismal names are the same.

On one of his journeys of business, five years before, Sasha visited the town of Perm, on the western side of the Ural Mountains. It is on the main highway to Siberia, and criminals are continually passing either on the way thither in chains, or returning in rags when their time of banishment has expired. One evening Sasha found by the roadside, in the outskirts of the town, a miserable looking wretch who seemed to be at the point of death. He felt the man's pulse, lifted up his head and looked in his face, and was startled at recognizing the younger of the three robbers who had attacked Baron Popoff. He had him taken to the inn, tended, and restored, and after being convinced of his earnest desire to lead a better life gave him employment. The robber was not naturally a bad man, but very ignorant and superstitious. It seemed to him both a miracle and a warning that he should have been saved by Sasha, and he fully believed that his soul would be lost if he should ever act dishonestly towards him.

Keeping his heart steadily upon the great purpose of his life, Sasha rose from one step to another until he became an independent and wealthy merchant, far wealthier, indeed, than the baron supposed. He paid the latter a handsome sum for his time, and sent only small presents of money to his parents, for he knew how few and simple their wants were. He felt a thousand times more keenly than old Gregor what it was to be a serf. The old man was still living, but very feeble and helpless, and Sasha often grew wild at the thought that he might die before knowing freedom.

His plan of action had been long fixed, and now the hour had come when he determined to try it. He had for years kept a strict watch over the baron's life in St. Petersburg, knew the amount of his increasing debts and the embarrassment they occasioned him, and could very nearly calculate the hour when ruin would overtake him. He was not disappointed, therefore, one morning at receiving an urgent summons to wait upon his master.

"Sasha," said the latter, laying his hand upon the shoulder of his serf with a familiarity he had never displayed before, "you are an honest, faithful fellow. I need a few thousand roubles for a month or two; can you get the money for me?"

"I have heard, my lord," answered Sasha, "that you are in difficulty. I knew why you sent for me, and I come to offer you a way out of all your troubles. Your debts amount to more than a hundred thousand roubles: would you like to be relieved of them?"

"Would I not!—but how?" exclaimed the baron.

"I will pay them, my lord; but you will do one thing for me in return."

"You, you!"

"I," Sasha quietly answered, "I will free you, and you will free me!"

"Ha!" the baron cried, springing to his feet. His pride was touched. He was fond of boasting that he also had a serf who was a rich merchant, and the fact had many a time helped his credit when he wanted to borrow money. Unconsciously he shook his head.

"You have not the money," he said.

Sasha, who understood what was passing through the mind of the baron, suffered so much from his cruel uncertainty that he turned deadly pale.

"I am well known," he answered, "and can procure the money in an hour. How much is my serfdom worth to you? My annual payment is hardly one-tenth of the usurious interest which your debt wrings from you: I offer to release you from all trouble, and thus add not less than eight thousand roubles a year to your income. And my freedom, which you can now sell back to me at such a price, may be mine without buying in a few years more!"

The emperor, Alexander II. (who was assassinated in 1881), had at that time just succeeded to the throne, and his intention to emancipate the serfs was already suspected by the people. Sasha knew that he was running a great risk in what he said; but his clasped hands, his trembling voice, his eyes filled with tears, affected the baron more powerfully than his words.

There was a long silence. The master turned away to the window, and weighed the offer rapidly in his mind; the serf waited in breathless anxiety in the centre of the room.

Suddenly the baron turned and struck his clenched fist on the table. Then he stretched out his hand and said:

"Alexander Ivanovitch, I am glad to make your acquaintance as a friend; I am no longer your master."

Sasha took the hand of the baron and kissed it, and his tears fell thick and fast.

"Dear Lord Baron," he cried, "give me also the freedom of my father and grandfather, and I will add a payment of five thousand roubles a year for ten years to come!"

"And your ancestors for five hundred years back," the baron answered laughing. "I don't know their names, but they can all be thrown into the deed in one lump."

Before another day passed it was done. Sasha and the other living members of his family were free, and his ancestors also would have been free if they had not been dead. With the parchment signed and sealed in his pocket he took a carriage and post-horses and travelled day and night until he reached his native village. No one knew the stranger in his rich merchant's dress; his father and brothers were at work, and his mother had gone to see a neighbour:—old Gregor was alone in the house. He was leaning back in a rude arm-chair, with a sheep-skin over his knees; his eyes were closed, his mouth slightly open, and his face so haggard and sunken that Sasha immediately thought he was dead.

He knelt down beside the chair, and placed his hand on the old man's heart, to see if it still beat. Presently came a broken voice, saying:

"The black god—the truth, my boy!" and Gregor feebly stretched a hand towards Sasha's breast. The latter tore open his dress, and spread the cold, horny fingers over his own heart, the warmth of which seemed to kindle a fresh life in the old man. He at last opened his eyes.

"Little Sasha!" said he; "little Sasha will keep his word."

"Grandfather," exclaimed Sasha, "I have kept it."

"It's a man—a brave looking man," said Gregor; "but he has the voice of my boy Sasha; and he has, yes, I know he has, his hand upon my heart."

Sasha could no longer restrain himself.

"And the boy is a freeman, grandfather," he exclaimed; "we are all free: here is the baron's deed, which says so, with the seal of the empire upon it. Look, grandfather, look!—do you understand, you are free!"

Gregor was lifted to his feet as if by an unseen hand. At that moment Sasha's father and mother, and brothers entered the house. The old man did not heed their cries of astonishment; clasping the parchment to his breast, he looked upward and exclaimed in a piercing voice:

"Free at last! all free! I will carry the news to God!"

Then, before any one—not even Sasha—could step forward to assist him, he reeled and fell on the floor—dead. His prayer had been granted.

I've seen many a brave man in my time, sure enough," said old Ivan Starikoff, removing his short pipe to puff out a volume of smoke from beneath his long white moustache.

"Many and many a one have I seen; for, thank heaven, the children of holy Russia are never wanting in that way, but all of them put together wouldn't make one such man as our old colonel, Count Pavel Petrovitch Severin. It was not only that he faced danger like a man—all the others did that—but he never seemed to know that there was any danger at all. It was as good as a reinforcement of ten battalions to have him among us in the thick of a fight, and to see his grand, tall figure drawn up to its full height, and his firm face and keen gray eyes turned straight upon the smoke of the enemy's line, as if defying them to hurt him. And when the very earth was shaking with the cannonade, and balls were flying thick as hail, and the hot, stifling smoke closed us in like the shadow of death, with a flash and a roar breaking through it every now and then, and the whole air filled with the rush of the shot, like the wind sweeping through a forest in autumn,—then Petrovitch would light a cigarette and hum a snatch of a song, as coolly as if he were at a dinner party in Moscow. And it really seemed as if the bullets ran away from him, instead of his running away from them; for he never got shot. But if he saw any of us beginning to waver he would call out cheerily:

"Never fear, lads, remember what the old song says!" for in those days we had an old camp-song that we were fond of singing, and the chorus of it was this:—

"Then fear not swords that brightly shine,

Nor towers that grimly frown;

For God shall march before our line,

And hew our foemen down."

"He said this so often, that at last he got the nickname among us of "Don't Fear," and he deserved it, if ever man did. Why, Father Nickolai Pavlovitch himself (the Emperor Nicholas) gave him the cross of St. George[1] with his own hand at the siege of Varna, in the year '28. You see, our battery had been terribly cut up by the Turkish fire, so at last there was only about half a dozen of us left on our feet. It was as hot work as I was ever in,—shot pelting, earthworks crumbling, gabions crashing, guns and gun-carriages tumbling over one another, men falling on every side like leaves, till all at once a shot went slap through our flag-staff, and down came the colours!

[1] The highest Russian decoration.

"Quick as lightning Pavel Petrovitch was upon the parapet, caught the flag as it fell, and held it right in the face of all the Turkish guns, while I and another man spliced the pole with our belts. You may think how the unbelievers let fly at him when they saw him standing there on the top of the breast-work, just as if he'd been set up for a mark; and all at once I saw one fellow (an Albanian by his dress, and you know what deadly shots they are) creep along to the very angle of the wall and take steady aim at him!

"I made a spring to drag the colonel down (I was his servant, you know, and whoever hurt him hurt me); but before I could reach him I saw the flash of the Albanian's piece, and Pavel Petrovitch's cap went spinning into the air with a hole right through it just above the forehead. And what do you think the colonel did? Why, he just snapped his fingers at the fellow, and called out to him, in some jibber-jabber tongue only fit to talk to a Turk in:

"'Can't you aim better than that, you fool? If I were your officer I'd give you thirty lashes for wasting the government ammunition!'

"Well, as I said before, he got the St. George, and of course everybody congratulated him, and there was a great shaking of hands, and giving of good wishes, and drinking his health in mavro tchai—that's a horrid mess of eggs, and scraped cheese, and sour milk, and Moldavian wine, which these Danube fellows have the impudence to call 'black tea,' as if it was anything like the good old tea we Russians drink at home! (I've always thought, for my part, that tea ought to grow in Russia; for it's a shame that these Chinese idolators should have such grand stuff all to themselves.)

"Well, just in the height of the talk Pavel Petrovitch takes the cross off his neck, and holds it out in his hand—just so—and says:

"'Well, gentlemen, you say I'm the coolest man in the regiment, but perhaps everybody wouldn't agree with you. Now, just to show that I want nothing but fair play, if I ever meet my match in that way I'll give him this cross of mine!'

"Now among the officers who stood near him was a young fellow who had lately joined—a quiet, modest lad, quite a boy to look at, with light curly hair and a face as smooth as any lady's. But when he heard what the colonel said he looked up suddenly, and there came a flash from his clear blue eyes like the sun striking a bayonet. And then I thought to myself:

"'It won't be an easy thing to match Pavel Petrovitch; but if it can be done, here is the man to do it!'

"I think that campaign was the hardest I ever served in. Before I was enlisted I had often heard it said that the Turks had no winter; but I had always thought that this was only a 'yarn,' though, indeed, it would be only a just judgment upon the unbelievers to lose the finest part of the whole year. But when down there I found it true, sure enough. Instead of a good, honest, cracking frost to freshen everything up, as our proverb says:

'Na zimni Kholod

Vsiaki molod'—

(in winter's cold every one is young), it was all chill, sneaking rain, wetting us through and through, and making the hill-sides so slippery that we could hardly climb them, and turning all the low grounds into a regular lake of mud, through which it was a terrible job to drag our cannon. Many a time in after days, when I've heard spruce young cadets at home, who had never smelt powder in their lives, talking big about 'glorious war,' and all that, I've said to myself, 'Aha, my fine fellows! if you had been where I have been, marching for days and nights over ankles in mud, with nothing to eat but stale black bread, so hard that you had to soak it before you could get it down; and if you'd had to drink water through which hundreds of horses had just been trampling; and to scramble up and down hills under a roasting sun, with your feet so swollen and sore that every step was like a knife going into you; and to lie all night in the rain, longing for the sun to rise that you might dry yourself a bit—perhaps then you wouldn't talk quite so loud about 'glorious war'!"

"However, we drove the Turks across the Balkans at last, and got down to Yamboli, a little town at the foot of the mountains which commands the high-road to Adrianople. And there the unbelievers made a stand, and fought right well. I will say that of them; for they knew that if Adrianople was lost all was over. But God fought for us, and we beat them; though indeed, with half our men sick, and our clothes all in rags, and our arms rusted, and our powder mixed with sand by those rogues of army-contractors, it was a wonder that we could fight at all.

"Towards afternoon, just as the enemy were beginning to give way, I saw Pavel Petrovitch (who was a general by this time) looking very hard at a mortar-battery about a hundred yards to our right; and all at once he struck his knee forcibly with his hand, and shouted:

"'What do the fellows mean by firing like that? They might as well pelt the Turks with potatoes! I'll soon settle them! Here, Ivan!' Away he went, and I after him; and he burst into the battery like a storm, and roared out:

"'Where's the blockhead who commands this battery?'

"A young officer stepped forward and saluted; and who should this be but the light-haired youth with the blue eyes whom I had noticed that night at Varna.

"'Well, you won't command it to-morrow, my fine fellow, for I'll have you turned out this very day. Do you know that not a single shell that you have thrown away since I've been watching you has exploded at all?'

"'With your excellency's leave,' said the young fellow, respectfully, but pretty firmly too, 'the fault is none of mine. These fuses are ill-made, and will not burn down to the powder.'

"'Fuses!' exclaimed the general. 'Don't talk to me of fuses; I'm too old for that rubbish! Isn't it enough for you to bungle your work, but you must tell me a falsehood into the bargain?'

"At the word 'falsehood' the young officer's face seemed to turn red-hot all in a moment, and I saw his hand clench as if he would drive his fingers through the flesh. He made one stride to the heap of bomb-shells, and taking one up in his arms struck a match on it.

"'Now,' said he quietly, 'your excellency can judge for yourself. I'm going to light this fuse; if your excellency will please to stand by and watch it burn you will see whether I have told you a falsehood or not.'

"The general started, as well he might. Not that he was afraid—you may be pretty sure of that—but to hear this quiet, bashful lad, who looked as if he had nothing in him, coolly propose to hold a lighted shell in his arms to see if it would go off, and ask him to stand by and watch it, was enough to startle anybody. However, he wasn't one to think twice about accepting a challenge; so he folded his arms and stood there like a statue. The young officer lighted the fuse, and it began to burn.

"As for me and the other men, you may fancy what we felt like. Of course we couldn't run while our officers were standing their ground; but we knew that if the shell did go off, it would blow every man of us to bits, and it was not pleasant to have to stand still and wait for it. I saw the men set their teeth hard as the flame caught the fuse; and as for me, I wished with all my heart and soul that if there were any good fuses in the heap this might turn out to be one of the bad ones. But no, it burned away merrily enough, and came down, and down, and down nearer and nearer to the powder. The young officer never moved a muscle, but stood looking steadily at the general, and the general at him. At last the red spark got close to the metal of the shell, and then I shut my eyes and prayed God to receive my soul.

"Just at that moment I heard the man next me give a quick gasp, as if he had just come up from a plunge under water; and I opened my eyes again just in time to see the fuse go out, and the young officer letting the shell drop at the general's feet without a word.

"For a moment the general stood stock-still, looking as if he didn't quite know whether to knock the young fellow down or to hug him in his arms like a son; but at last he held out his hand to him and said:

"'Well, it's a true proverb, that every one meets his match some day, and I've met mine today, there's no denying it. There's the Cross of St. George for you, my boy, and right well you deserve it, for if I'm 'the coolest man in my regiment,' you're the coolest in all Russia!'

"And so said all the rest when the story got abroad; and the commander-in-chief himself, the great Count Diebitsch, sent for the lad, and said a few kind words to him that made his face flush up like a young girl's. But in after days he became one of the best officers the Russian army ever had; and I've seen him with my own eyes complimented by the emperor himself in presence of the whole army. And from that day forth the whole lot of us, officers and men alike, never spoke of him by any other name but Khladnokrovni—'the cold-blooded one.'"

Katinka was tired, and lonely too. All day long, and for many days together, she had plied her distaff busily, drawing out the thread finer and finer from the great bunches of flax, which she herself had gathered and dried, till the birch-bark basket at her feet was almost filled with firm, well-shaped "twists," and the sticks in the great earthen pipkin, upon which the thread must be wound, grew fewer and fewer.

The tips of her fingers were sore, and it was dull work with no one to speak to except her faithful cat, Dimitri, who was never content when he saw his mistress working, unless he had a ball of thread for himself; and as she looked about her cheerless little room, so lonely now, she thought of the days when a kind mother had been near to lighten every duty; and joyous, merry children had been her companions in all childish sports. She hated the tiresome flax now, but then the happiest days were spent in the great flax-fields, playing at "hide-and-seek" up and down the paths the reapers made. And when the summer showers came pelting down, how she would catch her little sister Lisa, and run home with her on her back, while neighbour Voscovitch's children laughed and shouted after her as she ran. Ah, those were happy days! But now mother and sister were gone! Only she and her father were left in the little home, and she had to work so hard! She did wish that her life was different; that she was not poor lonely Katinka the peasant maid any more. Oh! why could she not be like the rich Lady Feodorovna instead, whose father, Count Vassilivitch, owned nearly all the houses and lands from Tver to Torjok, and had more than three hundred serfs on his estate.

Now Katinka's father, Ivan Rassaloff, was only an istvostchick (a drosky or cab driver), and owned nothing but a rickety old drosky,[1] and Todcloff, a sturdy little Cossack pony, and drove travellers here and there for a few kopecks a trip. But he saved money, and Katinka helped him to earn more; and one of these days, when they could sell the beautiful lace flounce on which she had been working during all her odd moments for three years, and which was nearly finished, they would be rich indeed. Besides, the isba (cottage) was not really so bad, and it was all their own; and then there was always Dimitri to talk to, who surely seemed to understand everything she said. So a smile chased away the gathering frown, and this time she looked round the room quite contentedly.

[1] Or droitzschka, a four-wheeled pleasure carriage.

Shall I tell you what the isba was like, that you may know how the poor people live in Russia? It was built of balks (great beams or rafters), laid horizontally one above the other, the ends crossing at each corner of the building; and it had a pointed roof, somewhat like that of a Swiss châlet. Inside the chinks were filled with moss and lime, to keep out the cold. It contained only one room; but a great canvas curtain hung from the roof, which by night divided the room in two, but by day was drawn aside.

There was a deal table, holding some earthenware pipkins, jars, and a samorar, or tea-urn—for even the poorest peasants have an urn, and drink tea at least three times a day; a deal settee, on which lay the winter store of flax; Katinka's distaff, and the curious candlestick which the Russian peasants use. This is a tall wooden upright fastened into a sort of trough, or hollowed log of birchwood, to keep it erect. To the top an iron cross-bar is attached (which can be raised or lowered at will), having at the end a small bowl containing oil and a floating wick, which burns brightly for several hours, and is easily lowered and refilled; while the wooden trough below catches the oil which drops.

But the most curious thing in the room was the stove. It was made of sheet-iron, and very large, with a door at one end, into which whole logs of wood could be put at once. It was oblong, and flat on the top, like a great black trunk; and on this flat top, with the fire smouldering away beneath him, Ivan always slept at night in the winter; and sometimes, when it was very cold, Katinka would bring her sheep-skin blanket and sleep there too! Not one Russian isba in fifty contains a bed; when there is a large family, father, mother, and little children all crowd upon the top of the stove in winter, and in summer they roll themselves up in their blankets and sleep outside by the door!

The lamp was lighted and shone brightly on Katinka, who made quite a pretty picture as she rested a while from her work to speak to Dimitri. She wore a white chemise with very full, long sleeves, and over it a sarafane of red linen with a short boddice and shoulder-straps of dark blue. On her head she had tied a gay-coloured kerchief, to keep the dust of the flax from her glossy black hair, which hung in a single heavy braid far down her back. One of these days, if she should marry, she would have to divide it in two braids, and wear a kerchief always.

Her shoes were braided, in a kind of basket-work, of strips of birch-bark, very pliant and comfortable, though rather clumsy in appearance.

All the day Katinka had been thinking of something which her father had told her in the morning about their neighbour, Nicholas Paloffsky, and his poor, motherless little ones. The mother had been very ill, for a long, long time, and Nicholas had spent all he could earn in buying medicines and good food for her, but they could not save her life. Then, when she died Nicholas was both father and mother to the little ones for months; but at last he too fell ill, and now there was no one to assist him.

Besides, he did not own his isba, and if the rent were not paid the very next day the starosta, or landlord, would turn him and his little ones out-of-doors, bitter winter though it was!

That was fearful! What could she do to help him? Suddenly there flashed across her mind a thought of her beautiful lace flounce, on which she had worked till she loved every thread of it, and in whose meshes she had woven many a bright fancy about the spending of the silver roubles that would be hers when she sold it. She had intended to buy a scarlet cusackau, or jacket, with gold embroidery, and a new drosky for her father, so that his passengers might give him a few more kopecks for a ride. But other plans came to her mind now.

Just then Ivan came home hungry; and as she hastened to prepare his supper of tea and black bread and raw carrots, and a kind of mushroom stewed in oil, she almost forgot of her neighbour Nicholas while waiting on her father, who was always so glad to come home to her and his snug, warm room.

But to-night, for a wonder, he was cross. All day he had waited in the cold, bleak public-square of Torjok, beating his arms and feet to keep himself warm; and occasionally, I fear, beating his patient little pony for the same reason. Not a "fare" had come near him, except a fat priest, in a purple silk gown and broad-brimmed hat, with long, flowing hair and beard, a gold-mounted staff in his hand, and a silver crucifix hanging from his girdle, who on reaching the church to which he bade Ivan drive quickly, gave him his blessing—and nothing more! So Ivan's pockets were empty, and the pony must go without his supper, unless Katinka had some dried fish for him.

Katinka, who had a tender heart for all animals, carried a great bowlful of fish out to Todeloff, who nibbled it eagerly; for ponies in Russia, especially those that are brought from Iceland, consider dried fish a great delicacy, and in winter often live on it for weeks together. Then she gave him a "good-night" kiss on the little white spot on his nose, and he seemed to whisper, "Now I don't mind the beatings I had to-day!"

When she returned to the house her father was already wrapped up in a sheepskin blanket on top of the stove, and snoring lustily; so she lowered the curtain and crept softly into her little corner behind it. But she could not sleep, for her mind was disturbed by thoughts of neighbour Nicholas, whose little ones perhaps were hungry; and at last she arose, filled and lighted the tall lamp, then unrolled her precious flounce, and worked steadily at it till, when morning came, only one little sprig remained to be done, and her doubts as to what she should do were dispelled in the bright sunlight.

After breakfast, which she made ready as briskly as though she had slept soundly all night, she said:

"Father, let me be your first fare to-day, and perhaps I may bring you good luck. Will you drive me to the Lady Feodorovna's?"

"What in the world are you going to do there, Katinka?" said her father, wonderingly.

"To ask if she will buy my lace," said Katinka. "She has so many beautiful lace dresses, surely she will find a place on one for my flounce."

"Ha!" said Ivan; "then we will have a feast. You shall make a cake of white flour and honey, and we will not eat "black-brod" for a month! But what will we do with so much money, my child?"

Katinka hesitated for a moment; then said, shyly:

"Pay Nicholas Paloffsky's rent, and send the Torjok doctor to cure him. May I, father?" she added, entreatingly, forgetting that the money would be her own.

"Hum-m-m!" said Ivan; "we shall see. But go now and prepare for your drive, for Todeloff does not like to be kept waiting."

Katinka was soon ready. With her sheepskin jacket, hat and boots, she did not fear the cold; and mounting the drosky, they drove rapidly towards Count Vassilivitch's beautiful home, not fearing to leave their little isba unattended, for the neighbours were all honest, and besides, there was nothing to steal! A drive of four versts (about three miles) brought them to their journey's end, and Katinka's heart beat anxiously as the old drosky rattled up through the courtyard to the grand hall door; but she went bravely up to the fine porter, and asked to see Lady Feodorovna.

"Bosja moia!" (bless me); "what do you want with my lady?" asked the gorgeous Russ who, in crimson and gold livery, serf though he was, looked scornfully down on free Katinka in her poor little sheepskin jacket.

I think Katinka would scarcely have found courage to answer him; but luckily the lady crossed the hall just then, and seeing Katinka, kindly beckoned her to enter, leading the way to her own private apartment.

"What do you wish with me?" she asked kindly. But Katinka was too bewildered by the splendour on every side to answer as she should.

Truly it appeared like fairyland to the young peasant maid. The room was long and very lofty; the ceiling, one great beautiful picture; the floor had no carpet, but was inlaid with different kinds of wood in many curious patterns; the walls were covered with blue flowered silk, on which mirrors and lovely pictures were hung alternately; while beautiful statues and luxurious couches covered with blue damask added to the elegance and comfort of the room.

There was no big, clumsy stove to be seen—for in the houses of the rich, in a recess in each room, is a kind of oven, in which a great wood fire is allowed to smoulder all day—but a delicious feeling of warmth prevailed, and a soft, sweet perfume floated on the air.

At last Katinka's eyes rested on the fair lady in her soft, fleecy gown of white (for even in winter Russian ladies wear the thinnest summer dresses in the house), and she said softly:

"I think this heaven, and surely you are like an angel!"

"Not an angel," said Lady Feodorovna, smiling, "but perhaps a good fairy. Have you a wish, pretty maid?"

"Indeed, yes," replied Katinka. "I wish, wish, wish (for you must always make a wish to a fairy three times) you would buy my lace flounce. See!"—and she unrolled it hurriedly from out the clean linen cloth in which it was wrapped. "It is fair and white, though I have worked on it for three years, and it is all finished but one little sprig. I could not wait for that; I want the money so much. Will you buy it?"

"What is the price?" asked the lady, who saw that it was indeed a beautiful piece of work.

"Ninety roubles" (about fifteen pounds), said Katinka almost in a whisper, as if she feared to name so great a sum aloud, though she knew the lace was worth it.

"Why, what will you do with so many roubles?" asked the lady, not curiously, but in such a good fairy way that Katinka said:

"Surely I need not fear to tell you. But it is a long story. Will you kindly listen to it all?"

"Yes, gladly; sit here," and the Lady Feodorovna pointed to one of the beautiful blue couches, on the extreme edge of which Katinka sat down timidly, making a very funny picture in her gray sheepskin jacket and scarlet gown. "Now tell me, first, your name."

"Katinka Rassaloff, barishna (lady), daughter of Ivan, peasants from beyond Torjok. Beside us lives a good man, Nicholas Paloffsky, who is ill, and so poor. He has four little children, and many a day I have divided my supper with them, and yet I fear they are often hungry. The baby cries all day, for there is no mother to take care of it, and the cries trouble the poor father, who can do nothing to help. Besides, unless the rent is paid to-morrow they must leave their isba. Think of that, lady; no home in this bitter winter weather! no shelter for the baby! Ah! buy my lace, that I may help them!" replied Katinka earnestly.

Without speaking, Lady Feodorovna rose and went to a beautiful cabinet, unlocked the door with a tiny gold key which was suspended by a chain to her girdle, took out a roll of silver roubles, and laid them in Katinka's lap.

"There," said she, "are one hundred roubles. Are you content?"

Katinka took the soft white hand in hers and kissed it, while such a happy smile lighted up her face that the "good fairy" needed no other answer.

"Hasten home, Katinka," she said; "perhaps you may see me soon again."

Katinka curtsied deeply, then almost flew out of the great hall-door, so startling the grand porter, who had his mouth wide open ready to scold her, that he could not get it shut in time to say a word, but opened his eyes instead to keep it company, and stood looking after her till she was seated in the drosky. Then Ivan "flicked" Todeloff, who kicked up his heels and rattled out of the courtyard in fine style. When they were out of sight the porter found he could say "bosja moia" again, so he said it; and feeling much relieved, was gradually getting back to his usual dignified manner, when his lady came tripping down the stairs, wrapped in a beautiful long sable mantle, bidding him order her sledge, and one for her maid, to be brought to the door at once.

When the sledges were brought Lady Feodorovna entered hers, and drew the soft white bear-skin robe around her, while her maid threw over her fur hood a fine, fleecy scarf of white wool. Then the maid put numberless packages, small and great, into the foot of the other sledge, leaving only just room to put herself in afterwards.

While they are waiting there I must tell you what Lady Feodorovna's sledge was like. It was built something like an open brougham, except that the back was higher, with a carved wooden ornament on the top; there was no "dash-board," but the runners came far up in a curve at the front, and where they joined was another splendid ornament of wood, gilded and surmounted by a gilt eagle with outspread wings.

The body of the sledge was of rose-wood, and in the front was a beautiful painting of Cupid, the "love-god," and his mother. The other sledge, which had a silver swan at the front, was not quite so fine, although the shape was the same.

There were no horses to draw these sledges, but behind each stood a servant in fur jacket, cap and boots, with a pair of skates hung over his shoulder.

"I wish to go to the isba of Paloffsky, the peasant, beyond Torjok; we will go the shorter way, by the river," said Lady Feodorovna. "Hasten!"

Then the servants each gave a great push, and the sledges started off so quickly and lightly down the slope to the river that they could scarcely keep up with them. When they reached the banks of the Blankow, which flowed past the count's grounds and was frozen over for miles, the servants stooped and put on their skates, binding them by long straps over their feet, and round and round their ankles. Then they started down the river, and oh, how they flew! while the sledges, with their gorgeous birds, fairly sparkled in the sunlight.

Sooner almost than I can tell it they had reached their journey's end; the skates were unstrapped, and the sledges drawn up the bank to the door of the little isba, which Lady Feodorovna entered, followed by the maid with the parcels.

A sad picture met their eyes. Poor Nicholas sat on a bench by the stove, wrapped in his sheepskin blanket, looking so pale, and thin that he scarcely seemed alive; on his knees lay the hungry baby, biting his little fist because he had nothing else to bite; while on the floor beside him sat a little three-year-old fellow crying bitterly, whom a sad little sister was vainly trying to comfort.

Nicholas looked up as the door opened, but did not speak as the strange lady advanced, and bade her maid open the packages and put their contents on the table. How the children stared! The little one stopped crying, and crept up to the table, followed shyly by his sister. Then the maid put a dainty white bread-roll in each little hand. Then she took the baby gently from off the poor, tired father's knee, and gave it spoonful after spoonful of sweet, pure milk, till its little pinched cheeks seemed fairly to grow full and rosy, and it gave a satisfied little "coo-o," that would have done your hearts good to hear. Meanwhile Lady Feodorovna went up to Nicholas, and said softly:

"Look at your little ones! they are happy now! Can you not rouse up and drink this good bowl of soup? It is warm yet, and will do you good. Drink, and then I will tell you some good news."

Nicholas took the bowl which she held towards him, but his hand trembled so that it would have fallen if she had not herself held it to his lips. As he tasted the warm nourishing soup new life seemed to come to him, and he grasped the bowl eagerly, drinking till the last drop was gone; then, looking up with a grateful smile he said simply, "Ah! we were so hungry, my little ones and I! Thanks, barishna."

"Now for my good news," said the lady. "Here is the money for your rent; and here are ten roubles more, for clothes for your little ones. The food there is sufficient for to-day; to-morrow I will send you more. Do not thank me," she added, as Nicholas tried to speak; "you must thank Katinka Kassaloff for it all."

Just then a great noise was heard outside, and little Todeloff came prancing merrily up to the door, shaking his head and rattling the little bells on his douga (the great wooden arch that all Russian horses have attached to their collars) as proudly as if he had the finest drosky in all St. Petersburg behind him.

Katinka jumped quickly down, and entering the little isba stood fairly speechless at seeing Lady Feodorovna, whom she had left so shortly before in her own beautiful home.

"Ah, Katinka! I have stolen a march on you," said the good fairy. "There is nothing you can do here."

"Is there not?" said Katinka. "See! here is the starosta's receipt for a year's rent, and there," turning towards the door as a venerable old man entered, "is the Torjok doctor, who has come to make neighbour Nicholas well."

I must tell you what the doctor was like. He wore a long fur coat with wide sleeves, fur boots, and a great pair of fur gloves, so that he looked almost like a bear standing up. He wore queer blue spectacles, and from under a little black velvet cap long, silky, white hair fell over his shoulders, and his white beard nearly reached to his waist.

The doctor walked up to Nicholas, put his hands on his knees, stooped, and looked gravely at him; then rising, turned sharply to Katinka and said.

"There is no sick one here! Why did you bring me so far for nothing? But it is two roubles all the same."

"Here are the roubles," said Katinka, "and I am very glad we do not want you;" which was not at all polite of her.

Then, too, Ivan had driven off in search of passengers, so the poor doctor had to walk nearly a verst (three quarters of a mile) through the snow, back to Torjok, which made him growl like a real bear all the way.

Katinka went shyly up to Nicholas, who was frowning crossly at her, and said:

"Are you angry with me? Do not frown so, I beg. Well, frown if you will! the children do not, and I did it all for them; I love them!" and she caught up baby Demetrius and buried her face in his curly hair to hide a tear that would come; for she felt grieved that Nicholas did not thank her, even with a smile, for what she had done.

When she looked up Lady Feodorovna and her maid were gone, and Nicholas stood before her holding little Noviska by one hand, while two-year-old Todleben clung to his knee.

"Katinka," said Nicholas gently, "now I can thank you with all my heart, though I cannot find words to speak my thanks. Let the children kiss you for it all; that is best."

Katinka kissed the children heartily, then she put down the baby and opened the door, but Nicholas's face was sober then, though his eyes still smiled as he said:

"Come back to tea, Katinka, and bring your father with you, and our young neighbour Alexis, who often is hungry, and we will have a feast of all these good things."

"Horro sha" (very well), said Katinka, then she quickly ran home.

Dimitri met her at the door, crying piteously.

"Poor Pussy!" said Katinka; "you have had nothing to eat all day! What a shame!"

"Miauw!" said Dimitri to that.

"Never mind, Pussy; you shall have all my supper, and father's too, for we are invited out to tea, so must not eat anything now."

"Miauw, miauw!" said pussy again to that, and scampered away to his bowl to be all ready for his fish, and milk, and sour cabbage soup, that he knew was coming.

Then Katinka hastened to brush her pretty hair, and put on her best sarafane (dress), with the scarlet embroidered boddice and straps, and was all ready when her father came in, to tell him of their invitation, and help him to make his toilet.

"I must have my hair cut," said Ivan, seating himself on a bench, while Katinka tied a band round his head, fastening it over his forehead, then got a great pair of shears and cut his hair straight round by the band. Then like a good little Russian daughter as she was, Katinka took a little bit of tallow candle and rubbed it on her father's head to keep it smooth, belted down his gray flannel blouse, and handed him his sheepskin jacket, with a hint that it was high time for them to be off.

When the guests entered his isba Nicholas kissed Ivan—for that is always the custom between Russian men who are friends—then he called to Alexis:

"Heads up, my boy, and help me with the supper."

Alexis, who was turning somersaults in his joy, came right side up with a spring, and soon the feast was on the table, and the four wooden benches drawn up around it.

Ivan and Nicholas had each a bench for himself, Alexis sat beside Katinka, while Noviska and Todleben were placed on the remaining bench.

Katinka had wrapped baby Demetrius up in his little lambskin blanket, and laid him on the top of the stove, where he fell fast asleep while she was patting his soft cheek.

What appetites they all had! and how quickly the good things disappeared! wine-soup and grouse; cheese-cakes and honey; white rolls and sweet cream-cakes vanished almost as if by magic, till at last there was only a bowl of cream left. Alexis—who had acted as waiter, removing all the empty dishes in turn—placed this in the middle of the table, giving to each one a birch-wood spoon and refilling the glasses with tea; then he sat down by Katinka again at the plain uncovered table.