GEORGE ALLEN,

SUNNYSIDE, ORPINGTON, KENT.

1876.

[1]

Title: Fors Clavigera (Volume 6 of 8)

Letters to the workmen and labourers of Great Britain

Author: John Ruskin

Release date: March 1, 2023 [eBook #70181]

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: George Allen

Credits: Jeroen Hellingman and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net/ for Project Gutenberg (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

[1]

November 28th, 1875.

(In the house of a friend who, being ashamed of me and my words, requests that this Fors may not be dated from it.)

‘Live and learn.’ I trust it may yet be permitted me to fulfil the adage a few years longer, for I find it takes a great deal of living to get a little deal of learning. (Query, meaning of ‘deal’?—substantive of verb deal—as at whist?—no Johnson by me, and shall be sure to forget to look when I have.) But I have learned something this morning,—the use of the holes in the bottom of a fireshovel, to wit. I recollect, now, often and often, seeing my mother sift the cinders; but, alas, she never taught me to do it. Did not think, perhaps, that I should ever have occasion, as a Bishop, to occupy myself in that manner; nor understand,—poor sweet mother,—how advisable it might be to have some sort of holes in my shovel-hat, for sifting cinders of human soul. [2]

Howsoever, I have found out the art, this morning, in the actual ashes; thinking all the time how it was possible for people to live in this weather, who had no cinders to sift. My hostess’s white cat, Lily, woke me at half-past five by piteous mewing at my window; and being let in, and having expressed her thanks by getting between my legs over and over again as I was shaving, has at last curled herself up in my bed, and gone to sleep,—looking as fat as a little pillow, only whiter; but what are the cats to do, to-day, who have no one to let them in at the windows, no beds to curl up into, and nothing but skin and bones to curl?

‘It can’t be helped, you know;—meantime, let Lily enjoy her bed, and be thankful, (if possible, in a more convenient manner). And do you enjoy your fire, and be thankful,’ say the pious public: and subscribe, no doubt, at their Rector’s request, for an early dole of Christmas coals. Alas, my pious public, all this temporary doling and coaling is worse than useless. It drags out some old women’s lives a month or two longer,—makes, here and there, a hearth savoury with smell of dinner, that little knew of such frankincense; but, for true help to the poor, you might as well light a lucifer match to warm their fingers; and for the good to your own hearts,—I tell you solemnly, all your comfort in, such charity is simply, Christ’s dipped sop, given to you for signal to somebody else than Christ, that it is his hour to find the windows of your soul open—to the Night, [3]whence very doleful creatures, of other temper and colour than Lily, are mewing to get in.

Indeed, my pious public, you cannot, at present, by any coal or blanket subscription, do more than blind yourselves to the plain order “Give to him that asketh thee; and from him that would borrow of thee, turn not thou away.”

To him that asketh us, say the public,—but then—everybody would ask us.

Yes, you pitiful public,—pretty nearly everybody would: that is indeed the state of national dignity, and independence, and gushing prosperity, you have brought your England into; a population mostly of beggars, (at heart); or, worse, bagmen, not merely bearing the bag—but nothing else but bags;—sloppy star-fishy, seven-suckered stomachs of indiscriminate covetousness, ready to beg, borrow, gamble, swindle, or write anything a publisher will pay for.

Nevertheless your order is precise, and clear; ‘Give to him that asketh thee’—even to the half of your last cloak—says St. Martin; even to the whole of it, says Christ: ‘whosoever of you forsaketh not all that he hath, cannot be my disciple.’

‘And you yourself, who have a house among the lakes, and rooms at Oxford, and pictures, and books, and a Dives dinner every day, how about all that?’

Yes, you may well ask,—and I answer very distinctly and frankly, that if once I am convinced (and it is [4]not by any means unlikely I should be so) that to put all these things into the hands of others, and live, myself, in a cell at Assisi, or a shepherd’s cottage in Cumberland, would be right, and wise, under the conditions of human life and thought with which I have to deal—very assuredly I will do so.

Nor is it, I repeat, unlikely that such conviction may soon happen to me; for I begin to question very strictly with myself, how it is that St. George’s work does not prosper better in my hands.

Here is the half-decade of years, past, since I began the writing of Fors, as a byework, to quiet my conscience, that I might be happy in what I supposed to be my own proper life of Art-teaching, at Oxford and elsewhere; and, through my own happiness, rightly help others.

But Atropos has ruled it quite otherwise. During these five years, very signal distress has visited me, conclusively removing all possibilities of cheerful action; separating and sealing a great space of former life into one wide field of Machpelah; and leaving the rest sunless. Also, everything I have set hand to has been unprosperous; much of it even calamitous;—disappointment, coupled with heavy money loss, happening in almost every quarter to me, and casting discredit on all I attempt; while, in things partly under the influence and fortune of others, and therefore more or less successful,—the schools at Oxford especially, which owe the greater part of their efficiency to the fostering zeal of Dr. Acland, [5]and the steady teaching of Mr. Macdonald,—I have not been able, for my own share, to accomplish the tenth part of what I planned.

Under which conditions, I proceed in my endeavour to remodel the world, with more zeal, by much, than at the beginning of the year 1871.

For these following reasons.

First, that I would give anything to be quit of the whole business; and therefore that I am certain it is not ambition, nor love of power, nor anything but absolute and mere compassion, that drags me on. That shoemaker, whom his son left lying dead with his head in the fireplace the other day,1—I wish he and his son had never been born;—but as the like of them will be born, and must so die, so long as things remain as they are, there’s no choice for me but to do all I know to change them, since others won’t.

Secondly. I observe that when all things, in early life, appeared to be going well for me, they were by no means going well, in the deep of them, but quite materially and rapidly otherwise. Whence I conclude that though things appear at present adverse to my work and me, they may not at all be adverse in the deep of them, but quite otherwise.

Thirdly. Though in my own fortune, unprosperous, and in my own thoughts and labour, failing, I find more and more every day that I have helped many persons [6]unknown to me; that others, in spite of my failures, begin to understand me, and are ready to follow; and that a certain power is indeed already in my hands, woven widely into the threads of many human lives; which power, if I now laid down, that line (which I have always kept the murmur of in my ears, for warning, since first I read it thirty years ago,)—

“Che fece per viltate’l gran rifiuto,”2

would be finally and fatally true of me.

Fourthly, not only is that saying of Bacon’s of great comfort to me, “therefore extreme lovers of their country, or masters, were never fortunate; neither can they be, for when a man placeth his thoughts without himself, he goeth not his own way,”3 for truly I have always loved my masters, Turner, Tintoret, and Carlyle, to the exclusion of my own thoughts; and my country more than my own garden: but also, I do not find in the reading of history that any victory worth having was ever won without cost; and I observe that too open and early prosperity is rarely the way to it.

But lastly, and chiefly. If there be any truth in the vital doctrines of Christianity whatsoever,—and [7]assuredly there is more than most of us recognise, or than any of us believe,—the offences committed in this century by all the nations of Christendom against the law of Christ have been so great, and insolent, that they cannot but be punished by the withdrawal of spiritual guidance from them, and the especial paralysis of efforts intelligently made for their good. In times of more ignorant sinning, they were punished by plagues of the body; but now, by plagues of the soul, and widely infectious insanities, making every true physician of souls helpless, and every false effort triumphant. Nor are we without great and terrible signs of supernatural calamity, no less in grievous changes and deterioration of climate, than in forms of mental disease,4 claiming distinctly to be necromantic, and, as far as I have examined the evidence relating to them, actually manifesting themselves as such. For observe you, my friends, countrymen, and brothers—Either, at this actual moment of your merry Christmas-time, that has truly come to pass, in falling London, which your greatest Englishman wrote of falling Rome, “the sheeted dead, do squeak and gibber in your English streets,”—Or, such a system of loathsome imposture and cretinous [8]blasphemy is current among all classes of England and America, as makes the superstition of all past ages divine truth in comparison!

One of these things is so—gay friends;—have it which way you will: one or other of these, to me, alike appalling; and in your principal street of London society, you have a picture of highly dressed harlots gambling, of naked ones, called Andromeda and Francesca of Rimini, and of Christ led to be crucified, exhibited, for your better entertainment, in the same room; and at the end of the same street, an exhibition of jugglery, professedly imitating, for money, what a large number of you believe to be the efforts of the returned Dead to convince you of your Immortality.

Meantime, at the other end—no, at the very centre of your great Babylon, a son leaves his father dead, with his head, instead of a fire, in the fireplace, and goes out himself to his day’s darg.

‘We are very sorry;—What can we do? How can we help it? London is so big, and living is so very expensive, you know.’

Miserables,—who makes London big, but you, coming to look at the harlotries in it, painted and other? Who makes living expensive, but you, who drink, and eat,5 and dress, all you can; and never in your lives did one stroke of work to get your living,—never [9]drew a bucket of water, never sowed a grain of corn, never spun a yard of thread;—but you devour, and swill, and waste, to your fill, and think yourselves good, and fine, and better creatures of God, I doubt not, than the poor starved wretch of a shoemaker, who shod whom he could, while you gave him food enough to keep him in strength to stitch.

We, of the so-called ‘educated’ classes, who take it upon us to be the better and upper part of the world, cannot possibly understand our relations to the rest better than we may where actual life may be seen in front of its Shakespearean image, from the stalls of a theatre. I never stand up to rest myself, and look round the house, without renewal of wonder how the crowd in the pit, and shilling gallery, allow us of the boxes and stalls to keep our places! Think of it;—those fellows behind there have housed us and fed us; their wives have washed our clothes, and kept us tidy;—they have bought us the best places,—brought us through the cold to them; and there they sit behind us, patiently, seeing and hearing what they may. There they pack themselves, squeezed and distant, behind our chairs;—we, their elect toys and pet puppets, oiled, and varnished, and incensed, lounge in front, placidly, or for the greater part, wearily and sickly contemplative. Here we are again, all of us, this Christmas! Behold the artist in tumbling, and in painting with white and red,—our object of worship, and applause: here sit we [10]at our ease, the dressed dolls of the place, with little more in our heads, most of us, than may be contained inside of a wig of flax and a nose of wax; stuck up by these poor little prentices, clerks, and orange-sucking mobility, Kit, and his mother, and the baby—behind us, in the chief places of this our evening synagogue. What for? ‘They did not stick you up’ say you,—you paid for your stalls with your own money. Where did you get your money? Some of you—if any Reverend gentlemen, as I hope, are among us,—by selling the Gospel; others by selling Justice; others by selling their Blood—(and no man has any right to sell aught of these three things, any more than a woman her body,)—the rest, if not by swindling, by simple taxation of the labour of the shilling gallery,—or of the yet poorer or better persons who have not so much, or will not spend so much, as the shilling to get there? How else should you, or could you, get your money,—simpletons?

Not that it is essentially your fault, poor feathered moths,—any more than the dead shoemaker’s. That blasphemous blockheadism of Mr. Greg’s,6 and the like of him, that you can swill salvation into other people’s bodies out of your own champagne-bottles, is the main root of all your national miseries. Indeed you are willing enough to believe that devil’s-gospel, you rich ones; or [11]most of you would have detected the horror of it before now; but yet the chief wrong lies with the assertors of it,—and once and again I tell you, the words of Christ are true,—and not their’s; and that the day has come for fasting, and prayer, not for feasting; but, above all, for labour—personal and direct labour—on the Earth that bears you, and buries—as best it can.

9th December.—I heard yesterday that the son of the best English portrait-painter we have had since Gainsborough, had learnt farming; that his father had paid two hundred pounds a year to obtain that instruction for him; and that the boy is gone, in high spirits, to farm—in Jamaica! So far, so good. Nature and facts are beginning to assert themselves to the British mind. But very dimly.

For, first, observe, the father should have paid nothing for that boy’s farming education. As soon as he could hold a hoe, the little fellow should have been set to do all he could for his living, under a good farmer for master; and as he became able to do more, taught more, until he knew all that his master knew,—winning, all the while he was receiving that natural education, his bread by the sweat of his brow.

‘But there are no farmers who teach—none who take care of their boys, or men.’

Miserables again, whose fault is that? The landlords choose to make the farmers middlemen between the peasants and themselves—grinders, not of corn, but of [12]flesh,—for their rent. And of course you dare not put your children under them to be taught.

Read Gotthelf’s ‘Ulric the Farm Servant’ on this matter. It is one of his great novels,—great as Walter Scott’s, in the truth and vitality of it, only inferior in power of design. I would translate it all in Fors, if I had time; and indeed hope to make it soon one of my school series, of which, and other promised matters, or delayed ones, I must now take some order, and give some account, in this opening letter of the year, as far as I can, only, before leaving the young farmer among the Blacks, please observe that he goes there because you have all made Artificial Blacks of yourselves, and unmelodious Christys,—nothing but the whites of your eyes showing through the unclean skins of you, here, in Merry England, where there was once green ground to farm instead of ashes.

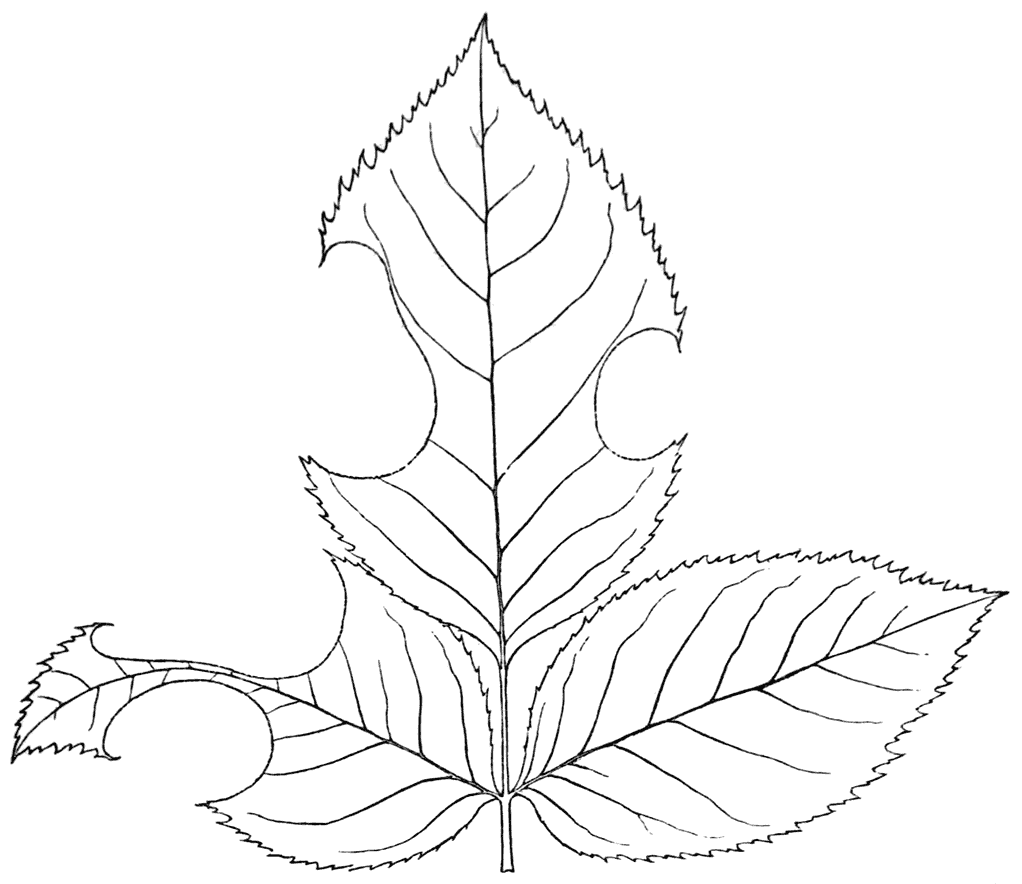

And first,—here’s the woodcut, long promised, of a rose-leaf cut by the leaf-cutting bee, true in size and shape; a sound contribution to Natural History, so far as it reaches. Much I had to say of it, but am not in humour to-day. Happily, the letter from a valued Companion, Art. III. in Notes, may well take place of any talk of mine.7

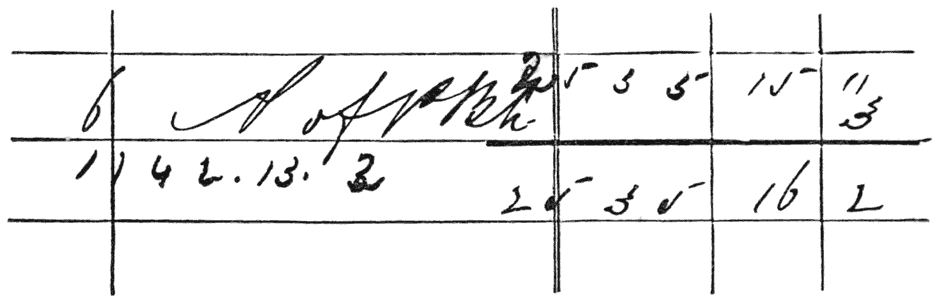

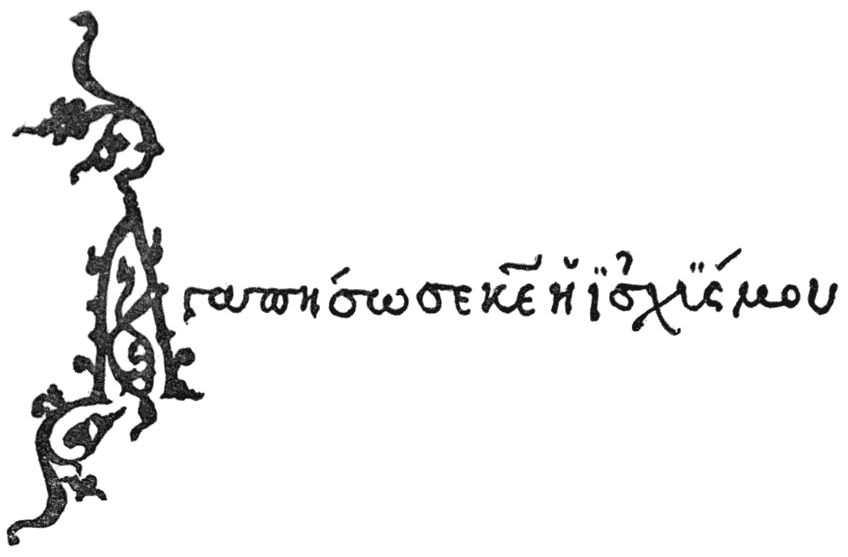

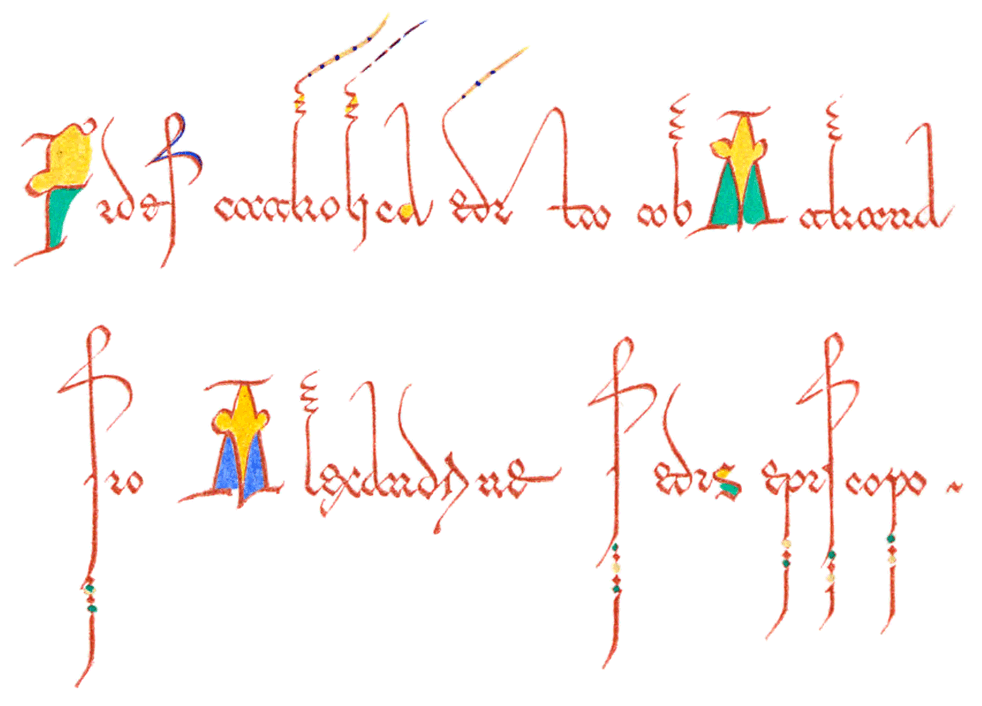

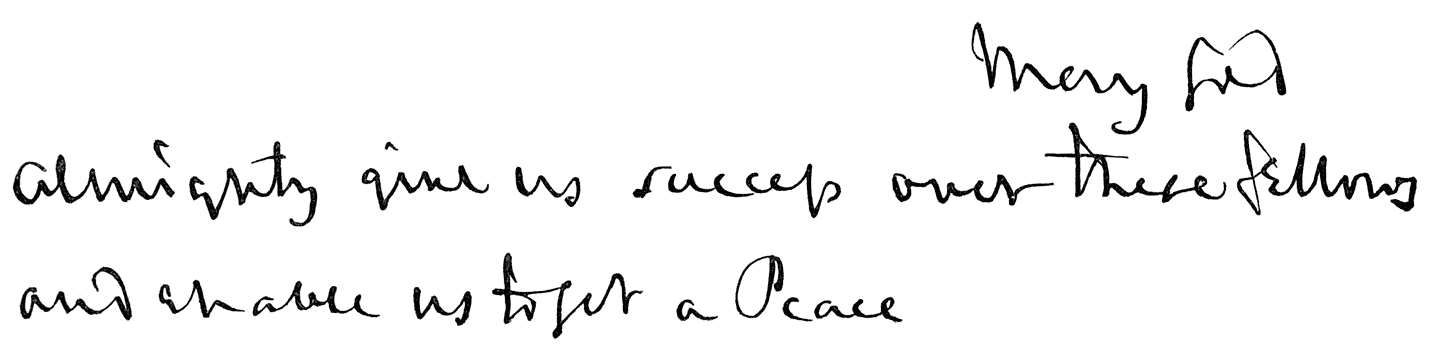

Secondly, I promised a first lesson in writing, of which, [13]therefore, (that we may see what is our present knowledge on the subject, and what farther we may safely ask Theuth8 to teach,) I have had engraved two examples, one of writing in the most authoritative manner, used for modern service, and the other of writing by a practised scribe of the fourteenth century. To make the comparison fair, we must take the religious, and therefore most careful, scripture of both dates; so, for example of modern sacred scripture, I take the casting up of a column in my banker’s book; and for the ancient, a letter A, with a few following words, out of a Greek Psalter, which [14]is of admirable and characteristic, but not (by any honest copyist,) inimitable execution.

Here then, first, is modern writing; in facsimile of which I have thought it worth while to employ Mr. Burgess’s utmost skill; for it seems to me a fact of profound significance that all the expedients we have invented for saving time, by steam and machinery, (not to speak of the art of printing,) leave us yet so hurried, and flurried, that we cannot produce any lovelier calligraphy than this, even to certify the gratifying existence of a balance of eleven hundred and forty-two pounds, thirteen shillings, and twopence, while the old writer, though required, eventually, to produce the utmost possible number of entire psalters with his own hand, yet has time for the execution of every initial letter of them in the manner here exhibited.

Respecting which, you are to observe that this is pure writing; not painting or drawing, but the expression of form by lines such as a pen can easily produce, (or a brush used with the point, in the manner of a pen;) and with a certain habitual currency and fluent [15]habit of finger, yet not dashing or flourishing, but with perfect command of direction in advance, and moment of pause, at any point.

You may at first, and very naturally, suppose, good reader, that it will not advance your power of English writing to copy a Greek sentence. But, with your pardon, the first need, for all beautiful writing, is that your hand should be, in the true and virtuous sense, free; that is to say, able to move in any direction it is ordered, and not cramped to a given slope, or to any given form of letter. And also, whether you can learn Greek or not, it is well, (and perfectly easy,) to learn the Greek alphabet, that if by chance a questionable word occur in your Testament, or in scientific books, you may be able to read it, and even look it out in a dictionary. And this particular manner of Greek writing I wish you to notice, because it is such as Victor [16]Carpaccio represents St. Jerome reading in his study; and I shall be able to illustrate by it some points of Byzantine character of extreme historical interest.

Copy, therefore, this letter A, and the following words, in as perfect facsimile as you can, again and again, not being content till a tracing from the original fits your copy to the thickness of its penstroke. And even by the time next Fors comes out, you will begin to know how to use a pen. Also, you may at spare times practise copying any clearly-printed type, only without the difference of thickness in parts of letters; the best writing for practical purposes is that which most resembles print, connected only, for speed, by the current line.

Next, for some elementary practice of the same kind in the more difficult art of Reading.

A young student, belonging to the working classes, who has been reading books a little too difficult or too grand for him, asking me what he shall read next, I have told him, ‘Waverley’—with extreme care.

It is true that, in grandeur and difficulty, I have not a whit really lowered his standard; for it is an achievement as far beyond him, at present, to understand ‘Waverley,’ as to understand the ‘Odyssey;’ but the road, though as steep and high-reaching as any he has travelled, is smoother for him. What further directions I am now going to give him, will be good for all young men of active minds who care to make such activity serviceable. [17]

Read your ‘Waverley,’ I repeat, with extreme care: and of every important person in the story, consider first what the virtues are; then what the faults inevitable to them by nature and breeding; then what the faults they might have avoided; then what the results to them of their faults and virtues, under the appointment of fate.

Do this after reading each chapter; and write down the lessons which it seems to you that Scott intended in it; and what he means you to admire, what to despise.

Secondly,—supposing you to be, in any the smallest real measure, a Christian,—begin the history of Abraham, as preparatory to that of the first Law-giver whom you have in some understanding to obey. And the history of Abraham must be led up to, by reading carefully from Genesis ix. 20th, forward, and learning the main traditions which the subsequent chapters contain.

And observe, it does not matter in the least to you, at present, how far these traditions are true. Your business is only to know what is said in Genesis. That does not matter to you, you think? Much less does it matter what Mr. Smith or Mr. Robinson said last night at that public meeting; or whether Mr. Black, or his brother, shot Mrs. White; or anything else whatever, small or great, that you will find said or related in the morning papers. But to know what is said in Genesis will enable you to understand, in some sort, the [18]effect of that saying on men’s minds, through at least two thousand years of the World’s History. Which, if you mean to be a scholar and gentleman, you must make some effort to do.

And this is the way to set about it. You see the tenth chapter of Genesis names to you the children, and children’s children, of Noah, from whom the nations of the world (it says) came, and by whom the lands of the world (it says) were divided.

You must learn them by rote, in order. You know already, I suppose, the three names, Shem, Ham, and Japheth; begin with Shem, and learn the names of his sons, thus:

| Shem. | |||||||||

| Elam. | Asshur. | Arphaxad. | Lud. | Aram. | |||||

| Salah. | |||||||||

| Eber. | |||||||||

| Peleg. | |||||||||

| (In his days was the earth divided.) | |||||||||

| Reu. | |||||||||

| Serug. | |||||||||

| Nahor. | |||||||||

| Terah. | |||||||||

| Abram. | |||||||||

[19]

Now, you see that makes a pretty ornamental letter T, with a little joint in the middle of its stalk.

And this letter T you must always be able to write, out of your head, without a moment’s hesitation. However stupid you may be at learning by rote, thus much can always be done by dint of sheer patient repetition. Read the centre column straight down, over and again, for an hour together, and you will find it at last begin to stick in your head. Then, as soon as it is fast there, say it over and over again when it is dark, or when you are out walking, till you can’t make a mistake in it.

Then observe farther that Peleg, in whose days the earth was divided, had a brother named Joktan, who had thirteen children. Of these, you need not mind the names of ten; but the odd three are important to you. Sheba, Ophir, and Havilah. You have perhaps heard of these before; and assuredly, if you go on reading Fors, you will hear of them again.

And these thirteen children of Joktan, you see, had their dwelling “from Mesha, as thou goest unto Sephar, a mount of the East.” I don’t know anything about Mesha and Sephar, yet; but I may: in the meantime, learn the sentence, and recollect that these people are fixed somewhere, at any rate, because they are to be Masters of Gold, which is fixed in Eastern, or Western, mountains; but that the children of the other brother, Peleg, can go wherever they like, [20]and often where they shouldn’t,—for “in his days was the earth divided.” Recollect also that the children of both brothers, or, in brief, the great Indian gold-possessing race, and the sacred race of prophets and kings of the higher spiritual world, are in the 21st verse of this chapter called “all the children of Eber.” If you learn so much as this well, it’s enough for this month: but I may as well at once give you the forms you have to learn for the other two sons.

| Ham. | ||||||||

| Cush. | Mizraim. | Phut. | Canaan. | |||||

| Nimrod. | Sidon, his first-born, and Heth. | |||||||

The seventh verse is to be noted as giving the gold-masters of Africa, under two of the same names as those of Asia, but must not be learned for fear of confusion. The form above given must be amplified and commented on variously, but is best learned first in its simplicity.

| Japheth. | |||||||||||||

| Gomer. | Magog. | Madai. | Javan. | Tubal. | Meshech. | Tiras. | |||||||

| Elisha. | |||||||||||||

| Tarshish. | |||||||||||||

| Kittim. | |||||||||||||

| Dodanim. | |||||||||||||

[21]

I leave this blunt-stalked and flat-headed letter T, also, in its simplicity, and we will take up the needful detail in next Fors.

Together with which, (all the sheets being now printed, and only my editorial preface wanting,) I doubt not will be published the first volume of the classical series of books which I purpose editing for St. George’s library;—Xenophon’s Economist, namely, done into English for us by two of my Oxford pupils; this volume, I hope, soon to be followed by Gotthelf’s Ulric the Farm-servant, either in French or English, as the Second Fors, faithfully observant of copyright and other dues, may decide; meantime, our first historical work, relating the chief decision of Atropos respecting the fate of England after the Conquest, is being written for me by a friend, and Fellow of my college of Corpus Christi, whose help I accept, in St. George’s name,—all the more joyfully, because he is our head gardener, no less than our master-historian.

And for the standard theological writings which are ultimately to be the foundation of this body of secular literature, I have chosen seven authors, whose lives and works, so far as the one can be traced or the other certified, shall be, with the best help I can obtain from the good scholars of Oxford, prepared one by one in perfect editions for the St. George’s schools. These seven books will contain, in as many volumes as may be needful, the lives and writings of [22]the men who have taught the purest theological truth hitherto known to the Jews, Greeks, Latins, Italians, and English; namely, Moses, David, Hesiod, Virgil, Dante, Chaucer, and, for seventh, summing the whole with vision of judgment, St. John the Divine.

The Hesiod I purpose, if my life is spared, to translate myself (into prose), and to give in complete form. Of Virgil I shall only take the two first Georgics, and the sixth book of the Æneid, but with the Douglas translation;9 adding the two first books of Livy, for completion of the image of Roman life. Of Chaucer, I take the authentic poems, except the Canterbury Tales; together with, be they authentic or not, the Dream, and the fragment of the translation of the Romance of the Rose, adding some French chivalrous literature of the same date. I shall so order this work, that, in such measure as it may be possible to me, it shall be in a constantly progressive relation to the granted years of my life. The plan of it I give now, and will explain in full detail, that my scholars may carry it out, if I cannot. [23]

And now let my general readers observe, finally, about all reading,—You must read, for the nourishment of your mind, precisely under the moral laws which, regulate your eating for the nourishment of the body. That is to say, you must not eat for the pleasure of eating, nor read, for the pleasure of reading. But, if you manage yourself rightly, you will intensely enjoy your dinner, and your book. If you have any sense, you can easily follow out this analogy: I have not time at present to do it for you; only be sure it holds, to the minutest particular, with this difference only, that the vices and virtues of reading are more harmful on the one side, and higher on the other, as the soul is more precious than the body. Gluttonous reading is a worse vice than gluttonous eating; filthy and foul reading, a much more loathsome habit than filthy eating. Epicurism in books is much more difficult of attainment than epicurism in meat, but plain and virtuous feeding the most entirely pleasurable.

And now, one step of farther thought will enable you to settle a great many questions with one answer.

As you may neither eat, nor read, for the pleasure of eating or reading, so you may do nothing else for the pleasure of it, but for the use. The moral difference between a man and a beast is, that the one acts primarily for use, the other for pleasure. And all acting for pleasure before use, or instead of use, is, in one word, ‘Fornication.’ That is the accurate meaning [24]of the words ‘harlotry,’ or ‘fornication,’ as used in the Bible, wherever they occur spoken of nations, and especially in all the passages relating to the great or spiritual Babylon.

And the Law of God concerning man is, that if he acts for use—that is to say, as God’s servant;—he shall be rewarded with such pleasure as no heart can conceive nor tongue tell; only it is revealed by the Spirit, as that Holy Ghost of life and health possesses us; but if we act for pleasure instead of use, we shall be punished by such misery as no heart can conceive nor tongue tell; but which can only be revealed by the adverse spirit, whose is the power of death. And that—I assure you—is absolute, inevitable, daily and hourly Fact for us, to the simplicity of which I to-day invite your scholarly and literary attention. [25]

The St. George’s Company is now distinctly in existence; formed of about twenty accepted Companions, to whose number I am daily adding, and to whom the entire property of the Company legally belongs, and who have the right at any moment to depose the Master, and dispose of the property in any manner they may think fit. Unless I believed myself capable of choosing persons for Companions who might be safely entrusted with this power I should not have endeavoured to form the society at all. Every one of these Companions has a right to know the names and addresses of the rest, which the Master of the Company must furnish him with; and of course the roll of the names, which will be kept in Corpus Christi College, is their legal certificate. I do not choose to begin this book at the end of the year, but at the beginning of the next term it will be done; and as our lawyer’s paper, revised, is now—15th December—in my hands, and approved, the 1st of January will see us securely constituted. I give below the initials of the Companions accepted before the 10th of this month, thinking that my doing so will be pleasing to some of them, and right, for all.

Initials of Companions accepted before 10th December, 1875. I only give two letters, which are I think as much indication as is at present desirable:— [26]

|

|

This ‘Fors’ is already so much beyond its usual limits, and it introduces subject-matter so grave, that I do not feel inclined to go into further business details this month; the rather because in the February ‘Fors,’ with the accounts of the Company, I must begin what the Master of the Company will be always compelled to furnish—statement of his own personal current expenditure. And this will require some explanation too long for to-day. I defer also the Wakefield correspondence, for I have just got fresh information about the destruction of Wakefield chapel, and have an election petition to examine:

I. Our notes for the year 1876 may, I think, best begin with the two pieces of news which follow; and which, by order of Atropos, also followed each other in the column of the ‘Morning Advertiser,’ from which I print them.

For, though I am by this time known to object to Advertisement in general, I beg the public to observe that my objection is only to bought or bribed Advertisement (especially if it be Advertisement of one’s self). But that I hold myself, and this book of mine, for nothing better than Morning, Noon, and [27]Evening Advertisers, of what things appear verily noteworthy in the midst of us. Whereof I commend the circumstances of the death, beneath related, very particularly to the attention of the Bishops of London and York.

Shocking Death from Starvation.—Last night Mr. Bedford, the Westminster coroner, held an inquest at the Board-room, Dean Street, Soho, on the body of Thomas Gladstone, aged 58, of 43, King Street, Seven Dials, a shoemaker, who was found dead on Thursday last.

William Gladstone, a lad of 15, identified the body as that of his father, with whom he and three other children lived. Deceased had been ailing for some time past, and was quite unable to do any work. The recent cold weather had such an effect upon him that he was compelled to remain in his room on Wednesday last, and at three the next morning witness found him sitting up in bed complaining of cold, and that he was dying. Witness went to sleep, and on awaking at eight that morning he found deceased with his head in the fireplace. Thinking he was only asleep, witness went to work, and on returning two hours later he was still in the same position, and it was then found that he was dead.

Coroner.—Why did you not send for a doctor?

Witness.—I didn’t know he wanted one until he was dead, and we found out amongst us that he was dead.

Jane Gladstone, the widow, said she had been living apart from her husband for some months, and first heard of his death at 2.30 on Thursday afternoon, and upon going to his room found him dead lying upon a mattress on the floor. He was always ailing, and suffered from consumption, for which he had received advice at St. George’s Hospital. They had had seven children, and for some time prior to the separation they had been in the greatest distress; and on the birth of her last child, on December 7, 1874, [28]they applied at the St. James’s workhouse for relief, and received two loaves and 2 lb. of meat per week for a month, and at the end of that time one of the relieving officers stopped the relief, saying that they were both able to work. They told the relieving officer that they had no work, and had seven children to keep, but he still refused to relieve them.

By the Coroner.—They did not ask again for relief, as deceased said “he had made up his mind that, after the way he had been turned away like a dog, he would sooner starve,” and she herself would also rather do so. Deceased was quite unable to earn sufficient to maintain the family, and their support fell mainly upon her, but it was such a hard life that she got situations for two of the boys, got a girl into a school, and leaving the other three boys with deceased, took the baby and separated from him. He was in great want at that time.

The Coroner.—Then why did you not go to the workhouse and represent his case to them?

Witness.—What was the good when we had been refused twice?

Mr. Green, the coroner’s officer, said that he believed the witness had been in receipt of two loaves a week from the St. James’s workhouse, but had not called lately for the loaves.

The Coroner said he hardly thought that so poor a woman would refuse or neglect to apply for so valuable a contribution to the needs of a family as two loaves of bread; and some of the jury said that Mr. Green must be mistaken, and that such a statement should be made upon oath if at all. The officer, however, was not sworn.

John Collins, of 43, King Street, said that about eleven o’clock on Thursday morning he met a gentleman on the stairs, who said that he had been up to the room of deceased to take him some work to do, but that the room door was locked, and a child had called out, “Father is dead, and you can’t come in.” Witness at [29]once went for the police, who came, and broke open the door. Upon going into the room witness found a piece of paper (produced) in which was written, “Harry, get a pint of milk for the three of you; father is dead. Tell your schoolmaster you can’t come to school any more. Cut your own bread, but don’t use the butter.” He believed that the eldest boy had returned home at ten o’clock in the morning, and finding two of the boys at school had left the note for them.

Police-constable Crabb, 18 C R., deposed to breaking open the door and finding deceased dead on the floor, with a little child crouching by him shivering with cold.

Dr. Howard Clarke, of 19, Lisle Street, Leicester Square, and Gerrard Street, Soho, said that he was called to see the deceased, and found him lying upon the floor of his room dead and cold, with nothing on him but stockings and a shirt, the room being nearly destitute of furniture. The place was in a most filthy condition, and deceased himself was so shockingly dirty and neglected, and so overrun with vermin, that he (witness) was compelled to wash his hands five times during the post-mortem examination. By the side of the corpse sat a little child about four years old, who cried piteously, “Oh, don’t take me away; poor father’s dead!” There was nothing in the shape of food but a morsel of butter, some arrowroot, and a piece of bread, and the room was cold and cheerless in the extreme. Upon making a post-mortem he found the brain congested, and the whole of the organs of the body more or less diseased. The unfortunate man must have suffered fearfully. The body was extremely emaciated, and there was not a particle of food or drop of liquid in the stomach or intestines. Death had resulted probably from a complication of ailments, but there was no doubt whatever that such death had been much accelerated by want of the common necessaries of life.

The Coroner.—Starvation, in short? [30]

Witness.—Precisely so. I never in all my experience saw a greater case of destitution.

The Coroner.—Then I must ask the jury to adjourn the case. Here is a very serious charge against workhouse officials, and a man dying clearly from starvation, and it is due alike to the family of the deceased, the parish officials, and the public at large, that the case should be sifted to the very bottom, and the real cause of this death elucidated.

Adjourned accordingly.

Shocking Discovery.—A painful sensation was, says the ‘Sheffield Telegraph,’ caused in the neighbourhood of Castleford, near Pontefract, on Friday evening, by the report made to a police-constable stationed at Allerton Bywater that a woman and child had been found dead in bed in Lock Lane, Castleford, under most mysterious circumstances, and that two small children were also found nearly starved to death beside the two dead bodies. The report, however, turned out to be correct. The circumstances surrounding the mystery have now been cleared up. An inquest, held on Saturday at Allerton Bywater, before Dr. Grabham, of Pontefract, reveals the following:—It appears on Sunday, the 28th ult., John Wilson, miner, husband of Emma Wilson, aged thirty-six years (one of the deceased), and father of Fred, aged eighteen months (the other deceased), left home to proceed to his employment at Street House Colliery, and would remain away all the week. Mrs. Wilson was seen going into her house on Monday evening, but was not seen again alive. There were besides the woman three children of very tender years in the house. The neighbours missed the woman and children from Monday night, but finding the blinds were drawn down, concluded that the family had gone to the husband. On Friday evening a neighbour, named Ann Foggett, rapped at the door, and hearing the faint bark of a dog, which was found to be fastened up in a [31]cupboard, continued to knock at the door, and ultimately heard the voice of a child. The door was subsequently burst open, and on proceeding upstairs the sight was horrifying. On the bed lay the mother and infant child dead, beside whom were two other small children in their night dresses. They, too, were nigh death’s door, having been without proper food and clothing evidently since their mother’s death, which must have occurred on the Monday night. Beside the corpse of the mother lay a knife and portions of a loaf of bread, which had been no doubt taken to her by the children to be supplied with some, but being unable to get an answer from her, they had nibbled the middle of the loaf clean away. A post-mortem examination showed that the mother had died from heart disease, and the child on the following day from starvation. The jury returned a verdict to that effect.—Morning Advertiser, December 7th, 1875.

II. The following is sent me by a correspondent. Italics mine throughout. The passage about threshing is highly curious; compare my account of the threshers at Thun. Poor Gilbert had been doubtless set to thresh, like Milton’s fiend, by himself, and had no creambowl afterwards.

24th October, 1800.

Gilbert Burns to James Currie, M.D.

The evils peculiar to the lower ranks of life derive their power to wound us from the suggestions of false pride, and the contagion of luxury, rather than from the refinement of our taste. There is little labour which custom will not make easy to a man in health, if he is not ashamed of his employment, or does not begin to compare his situation with those who go about at their ease. But the man of enlarged mind feels the respect due to him as a man; he has learnt that no employment is dishonourable in itself; that, while he performs aright the duties of the station in which God has placed him, he is as great as a [32]king in the eyes of Him whom he is principally desirous to please. For the man of taste, who is constantly obliged to labour, must of necessity be religious. If you teach him only to reason, you may make him an atheist, a demagogue, or any vile thing; but if you teach him to feel, his feelings can only find their proper and natural relief in devotion and religious resignation. I can say from my own experience that there is no sort of farm labour inconsistent with the most refined and pleasurable state of the mind, that I am acquainted with, threshing alone excepted. That, indeed, I have always considered insupportable drudgery, and think the man who invented the threshing-machine ought to have a statue among the benefactors of his country.

Perhaps the thing of most importance in the education of the common people is to prevent the intrusion of artificial wants. I bless the memory of my father for almost everything in the dispositions of my mind and the habits of my life, which I can approve of, and for none more than the pains he took to impress my mind with the sentiment that nothing was more unworthy the character of a man than that his happiness should in the least depend on what he should eat and drink.

To this hour I never indulge in the use of any delicacy but I feel a degree of reproach and alarm for the degradation of the human character. If I spent my halfpence in sweetmeats, every mouthful I swallowed was accompanied with shame and remorse. … Whenever vulgar minds begin to shake off the dogmas of the religion in which they have been educated, the progress is quick and immediate to downright infidelity, and nothing but refinement of mind can enable them to distinguish between the pure essence of religion and the gross systems which men have been perpetually connecting it with. Higher salaries for village schoolmasters, high English reading-classes, village libraries,—if once such high education were to become general, the [33]low delights of the public-house, and other scenes of riot, would be neglected; while industry, order, and cleanliness, and every virtue which taste and independence of mind could recommend, would prevail and flourish. Thus possessed of a virtuous and enlightened populace, with delight I should consider my country at the head of all the nations of the earth, ancient or modern.—From the ‘Life of Robert Burns.’

III. The following letter is, as I above said, from a valued, and, at present, my most valued,—Companion;—a poor person, suffering much and constant pain, confined to her room, and seeing from her window only a piece of brick wall and a little space of sky. The bit about the spider is the most delightful thing to me that has ever yet come of my teaching:—

I have told the only two children I have seen this summer, about the bees, and both were deeply interested, almost awe-stricken by the wonderful work. How could they do it without scissors? One, an intelligent boy of six years, is the well-cared-for child of well-to-do parents. He came into my room when I was sorting some of the cut leaves, and I gave him a very cleanly-cut specimen, saying, “What do you think cut this, Willie?” “It was somebody very clever, wasn’t it?” he asked. “Very clever indeed,” I said. “Then it was Miss Mildred!”—his governess. “No, not Miss Mildred,” I replied. He stood silent by the side of the bed for a minute, looking intently at the leaf in his hand, and evidently puzzling out some idea of his own; and I waited for it—a child’s own thoughts are lovely;—then my little visitor turned eagerly to me: “I know,—I know who did it: it was God.”

My second pupil is a girl of twelve years. She was a veritable “little ragamuffin” when—ten months back—we took her, [34]motherless, and most miserably destitute, into our home, in the hope of training her for service; and my sister is persistently labouring—with pleasing success, and disheartening failure—to mould her into an honest woman, while I try to supplement her efforts by giving the child—Harriett—lessons according to ‘Fors.’ But I regret to say it is only partially done, for I am but a learner myself, and sorely hindered by illness: still the purpose is always in my mind, and I do what I can.

Taking advantage of every trifle that will help to give Harriett a love for innocent out-of-door life, we told her—as soon as we could show her some of the cut leaves—of the work of the cutter bees, much to her delight. “And then she forgot all about them,” many persons would assert confidently, if they heard this story.

Not so, for some weeks after she told me with great pride that she had two of “the bees’ leaves,” thinking they were probably only eaten by caterpillars. I asked to see them; and then, how she obtained them. She had found them in a glass of withered flowers sent out of the parlour, and carefully dried them—(she had seen me press leaves); and she added, “all the girls” in her class in the Sunday-school “did want them.” I wondered why the leaves were taken there, until I discovered that she keeps them in her Testament.

So far the possibility; may I now give a proof of the utility of such teaching? When Harriett first came to us, she had an appetite for the horrible that quite frightened me, but it is gradually, I hope, dying out, thanks to the substitution of child-like pleasures. Imagine a child of eleven years coolly asking—as Harriett did a few days after she came—“If you please, has anybody been hanged, or anything, this week?” and she added, before I could reply, and looking quite wistfully at a newspaper lying near, “I should love to hear about it, please.” I could have cried, for I believe there are many lovable [35]young ladies in this town who are fretting out weary lives, to whom work would be salvation, and who can tell the number of such children all about them, who have not a soul to care how they live, or if they die.

Harriett used to catch and kill flies for pleasure, and would have so treated any living insect she saw; but she now holds bees in great respect, and also, I hope, some other insect workers, for one day she was much pleased to find one of the small spotted spiders, which had during the night spun its web across the fire-grate. She asked me many questions about it, (I permit her to do so on principle, at certain times, as a part of her education); she said it was “a shame” to break “such beautiful work,” and left it as long as she could; and then, (entirely of her own accord) she carefully slipped her dusting brush under web and spider, and so put the “pretty little dear” outside the window, with the gentle remark, “There, now you can make another.” Was not this hopeful? This child had lived all her life in one of the low, crowded courts in the centre of the town, and her ignorance of all green life was inconceivable. For instance, to give her a country walk I sent her last March with a parcel to a village near the town, and when she came back—having walked a mile through field-paths—she said she did not think there were “such a many trees and birds in the world.” And on that memorable day she first saw the lambs in the field—within two miles of the house where she was born. Yet she has the purest love for flowers, and goes into very real ecstasies over the commonest weeds and grasses, and is nursing with great pride and affection some roots of daisy, buttercup, and clover which she has brought from the fields, and planted in the little yard at the back of our house; and every new leaf they put forth is wonderful and lovely to her, though of course her ideas of “gardening” are as yet most elementary, and will be for some time, apparently. But it is really helpful to me to see her happiness [36]over it, and also when my friends send me a handful of cut flowers—we have no garden; and the eagerness with which she learns even their names, for it makes me feel more hopeful about the future of our working classes than some of your correspondents.

The despairing letter from Yorkshire in last ‘Fors’—on their incapacity to enjoy wholesome amusements—has prompted me, as I am writing to you, to tell you this as an antidote to the pain that letter must have given you. For if we can do nothing for this generation, cannot we make sure that the next shall be wiser? Have not young ladies a mighty power in their own hands here, if they but use it for good, and especially those who are Sabbath-school teachers? Suppose each one who has a garden felt it to be her duty to make all her scholars as familiar with all the life in it as she is herself, and every one who can take a country walk her duty to take her girls with her—two or three at a time—until they know and love every plant within reach; would not teacher and pupils learn with this much more that would also be invaluable?10 And if our Sunday-school children were not left to killing flies and stoning cats and dogs during the week, would there be so many brutal murders and violent assaults? The little English heathen I have named has attended a Sunday-school for about six years, and the Sunday-school teachers of this town are—most of them—noble men and women, who devoutly labour year after year “all for love, and nothing for reward.” But even good people too often look on the degradation of the lower classes as a matter of course, and despise them for ignorance they cannot help. Here the sneer of “those low shoemakers” is for ever on the lip, yet few ask how they became so much lower than ourselves; still I have very pleasing proof of what may be done even for adults by a little wise guidance, but I must not enter into that subject. Pray forgive me for writing so [37]much: I have been too deeply interested, and now feel quite ashamed of the length of this.

Again thanking you most earnestly for all you have taught me to see and to do,

I remain, very faithfully yours.

IV. What the young ladies, old ladies, and middle aged-ladies are practically doing with the blessed fields and mountains of their native land, the next letter very accurately shows. For the sake of fine dresses they let their fathers and brothers invest in any Devil’s business they can steal the poor’s labour by, or destroy the poor’s gardens by; pre-eminently, and of all Devil’s businesses, in rushing from place to place, as the Gennesaret swine. And see here what comes of it.

A gentleman told me the other night that trade, chiefly in cotton from India, was going back to Venice. One can’t help being sorry—not for our sake, but Venice’s—when one sees what commercial prosperity means now.

There was a lovely picture of Cox’s of Dollwydellan (I don’t think it’s spelt right) at the Club. All the artists paint the Slidr valley; and do you know what is being done to it? It’s far worse than a railway to Ambleside or Grasmere, because those places are overrun already; but Dollwydellan is such a quiet out-of-the-way corner, and no one in the world will be any the better for a railway there. I went about two months ago, when I was getting better from my first illness; but all my pleasure in the place was spoiled by the railway they are making from Betwys. It is really melancholy to see the havoc it makes. Of course no one cares, and they crash, and cut, and destroy, like utter barbarians, as they are. Through the sweetest, wildest little glens, the line is cleared—rocks are blasted for it, trees lie cut—anything and everything is sacrificed—and for what? The tourists will see nothing if they [38]go in the train; the few people who go down to Betwys or Llanwrst to market, will perhaps go oftener, and so spend more money in the end, and Dollwydellan will get some more people to lodge there in the summer, and prices will go up.11 In the little village, a hideous ‘traction engine’ snorted and puffed out clouds of black smoke, in the mornings, and then set off crunching up and down the roads, to carry coals for the works, I think; but I never in my life saw anything more incongruous than that great black monster getting its pipes filled at a little spring in the village, while the lads all stood gaping round. The poor little clergyman told us his village had got sadly corrupted since the navvies came into it; and when he pointed out to us a pretty old stone bridge that was being pulled down for the railway, he said, “Yes, I shall miss that, very much;” but he would not allow that things so orthodox as railways could be bad on the whole. I never intended, when I began, to trouble you with all this, but Cox’s picture set me off, and it really is a great wrong that any set of men can take possession of one of the few peaceful spots left in England, and hash it up like that. Fancy driving along the road up the Slidr valleys and seeing on boards a notice, to “beware when the horn was blowing,” and every now and then hearing a great blasting, smoke, and rocks crashing down. Well, you know just as well as I how horrible it all is. Only I can’t think why people sit still, and let the beautiful places be destroyed.

The owners of that property,—I forget their name, but they had monuments in the little old church,—never live there, [39]having another ‘place’ in Scotland,—so of course they don’t care.12

V. A fragment to illustrate the probable advantage of sulphurous air, and articles, in the country.

I did not think to tell you, when speaking of the fatality of broken limbs in our little dressmaker and her family, that when in St. Thomas’s Hospital with a broken thigh, the doctors said in all probability the tenderness of her bones was owing to the manufacture of sulphur by her mother’s grandfather. Dr. Simon knows her family through operating on the brother of our dressmaker, and often gave them kindly words at the hospital.

I am, dear Sir,

Yours faithfully.

[41]

2 Inferno, III. 60. I fear that few modern readers of Dante understand the dreadful meaning of this hellish outer district, or suburb, full of the refuse or worthless scum of Humanity—such numbers that “non haverei creduto, che morte tanta n’ havesse disfatta,”—who are stung to bloody torture by insects, and whose blood and tears together—the best that human souls can give—are sucked up, on the hell-ground, by worms. ↑

4 I leave this passage as it was written: though as it passes through the press, it is ordered by Atropos that I should hear a piece of evidence on this matter no less clear as to the present ministry of such powers as that which led Peter out of prison, than all the former, or nearly all, former evidence examined by me was of the presence of the legion which ruled among the Tombs of Gennesaret. ↑

6 Quoted in last Fors, p. 341, lines 18–22, from ‘Contemporary Review.’ Observe that it is blasphemy, definitively and calmly uttered, first against Nature, and secondly against Christ. ↑

7 The most valuable notes of the kind correspondent who sent me this leaf, with many others, and a perfect series of nests, must be reserved till spring-time: my mind is not free for them, now. ↑

“A Bishop by the altar stood,

A noble Lord of Douglas blood,

With mitre sheen, and rocquet white,

Yet showed his meek and thoughtful eye

But little pride of prelacy;

More pleased that, in a barbarous age,

He gave rude Scotland Virgil’s page,

Than that beneath his rule he held

The bishopric of fair Dunkeld.”

11 Yes, my dear, shares down; and—it is some poor comfort for you and me to know that. For as I correct this sheet for press, I hear from the proprietor of the chief slate quarry in the neighbourhood, that the poor idiots of shareholders have been beguiled into tunnelling four miles under Welsh hills—to carry slates! and even those from the chief quarry in question, they cannot carry, for the proprietors are under contract to send them by an existing line. ↑

There were more, and more harmful misprints in last ‘Fors’ than usual, owing to my having driven my printers to despair, after they had made all the haste they could, by late dubitation concerning the relative ages of Shem, Ham, and Japheth, which forced me to cut out a sentence about them, and displace corrected type. But I must submit to all and sundry such chances of error, for, to prevent them, would involve a complete final reading of the whole, with one’s eye and mind on the look-out for letters and stops all along, for which I rarely allow myself time, and which, had I a month to spare, would yet be a piece of work ill spent, in merely catching three t’s instead of two in a “lettter.” The name of the Welsh valley is wrong, too; but I won’t venture on correction of that, which I feel to be hopeless; the reader must, however, be kind enough to transfer the ‘and,’ now the sixth word in the upper line of the [42]note at page 38, and make it the fourth word, instead; to put a note of interrogation at the end of clause in the fourth line of page 35, and to insert an s, changing ‘death’ into ‘deaths’ in the third line of page 27;—the death in Sheffield being that commended to the Episcopic attention of York, and that in London to the Episcopic attention of London.

And this commendation, the reader will I hope perceive to be made in sequel to much former talk concerning Bishops, Soldiers, Lawyers, and Squires;—which, perhaps, he imagined me to have spoken jestingly; or it may be, in witlessness; or it may be, in voluble incipient insanity. Admitting myself in no small degree open to such suspicion, I am now about to re-word some matters which madness would gambol from; and I beg the reader to observe that any former gambolling on my part, awkward or untimely as it may have seemed, has been quite as serious, and intentionally progressive, as Morgiana’s dance round the captain of the Forty Thieves.

If, then, the reader will look at the analysis of Episcopacy in ‘Sesame and Lilies,’ the first volume of all my works; next at the chapter on Episcopacy in ‘Time and Tide;’ and lastly, refer to what he can gather in the past series of ‘Fors,’ he will find the united gist of all to be, that Bishops cannot take, much less give, account of men’s souls unless they first take and give account of their bodies: and that, [43]therefore, all existing poverty and crime in their dioceses, discoverable by human observation, must be, when they are Bishops indeed, clearly known to, and describable by them, or their subordinates. Of whom the number, and discipline in St. George’s Company, if by God’s grace it ever take the form I intend, will be founded on the institution of the same by the first Bishop, or more correctly Archbishop, whom the Christian church professes to obey. For what can possibly be the use of printing the Ten Commandments which he delivered, in gold,—framing them above the cathedral altar,—pronouncing them in a prelatically sonorous voice,—and arranging the responsive supplications of the audience to the tune of an organ of the best manufacture, if the commanding Bishops institute no inquiry whatever into the physical power of—say this starving shoemaker in Seven Dials,—to obey such a command as ‘thou shalt not covet’ in the article of meat; or of his son to honour in any available measure either the father or mother, of whom the one has departed to seek her separate living, and the other is lying dead with his head in the fireplace.

Therefore, as I have just said, our Bishops in St. George’s Company will be constituted in order founded on that appointed by the first Bishop of Israel, namely, that their Primate, or Supreme Watchman, shall appoint under him “out of all the people, able men, such as [44]fear God, men of truth, hating covetousness, and place such over them to be rulers (or, at the least, observers) of thousands, rulers of hundreds, rulers of fifties, and rulers of tens;”1 and that of these episcopic centurions, captains of fifty, and captains of ten, there will be required clear account of the individual persons they are set over;—even a baby being considered as a decimal quantity not to be left out of their account by the decimal Bishops,—in which episcopacy, however, it is not improbable that a queenly power may be associated, with Norman caps for mitres, and for symbol of authority, instead of the crosier, (or crook, for disentangling lost sheep of souls from among the brambles,) the broom, for sweeping diligently till they find lost silver of souls among the dust.

You think I jest, still, do you? Anything but that; only if I took off the Harlequin’s mask for a moment, you would say I was simply mad. Be it so, however, for this time.

I simply and most utterly mean, that, so far as my best judgment can reach, the present Bishops of the English Church, (with only one exception, known to me,—the Bishop of Natal,) have forfeited and fallen from their Bishoprics by transgression; and betrayal of their Lord, first by simony, and secondly, and chiefly, by lying for God with one mouth, and contending for their own personal interests as a professional body, as [45]if these were the cause of Christ. And that in the assembly and Church of future England, there must be, (and shall be so far as this present body of believers in God and His law now called together in the name of St. Michael and St. George are concerned,) set up and consecrated other Bishops; and under them, lower ministering officers and true “Dogs of the Lord,” who, with stricter inquisition than ever Dominican, shall take knowledge—not of creeds, but of every man’s way and means of life; and shall be either able to avouch his conduct as honourable and just, or bound to impeach it as shameful and iniquitous, and this down to minute details;—above all, or before all, particulars of revenue, every companion, retainer, or associate in the Company’s work being bound to keep such accounts that the position of his affairs may be completely known to the Bishops at any moment: and all bankruptcies or treacheries in money matters thus rendered impossible. Not that direct inquisition will be often necessary; for when the true nature of Theft, with the other particulars of the Moral Law, are rightly taught in our schools, grown-up men will no more think of stealing in business than in burglary. It is merely through the quite bestial ignorance of the Moral Law in which the English Bishops have contentedly allowed their flocks to be brought up, that any of the modern English conditions of trade are possible.

Of course, for such work, I must be able to find [46]what Jethro of Midian assumes could be found at once in Israel, these “men of truth, hating covetousness,” and all my friends laugh me to scorn for thinking to find any such.

Naturally, in a Christian country, it will be difficult enough; but I know there are still that kind of people among Midianites, Caffres, Red Indians, and the destitute, afflicted, and tormented, in dens and caves of the earth, where God has kept them safe from missionaries:—and, as I above said, even out of the rotten mob of money-begotten traitors calling itself a ‘people’ in England, I do believe I shall be able to extricate, by slow degrees, some faithful and true persons, hating covetousness, and fearing God.

And you will please to observe that this hate and fear are flat opposites one to the other; so that if a man fear or reverence God, he must hate covetousness; and if he fear or reverence covetousness, he must hate God; and there is no intermediate way whatsoever. Nor is it possible for any man, wilfully rich, to be a God-fearing person; but only for those who are involuntarily rich, and are making all the haste they prudently and piously can, to be poor; for money is a strange kind of seed; scattered, it is poison; but set, it is bread: so that a man whom God has appointed to be a sower must bear as lightly as he may the burden of gold and of possessions, till he find the proper places to sow them in. But persons desiring to be rich, and accumulating [47]riches, always hate God, and never fear Him; the idol they do fear—(for many of them are sincerely religious) is an imaginary, or mind-sculptured God of their own making, to their own liking; a God who allows usury, delights in strife and contention, and is very particular about everybody’s going to his synagogues on Sunday.

Indeed, when Adam Smith formally, in the name of the philosophers of Scotland and England, set up this opposite God, on the hill of cursing against blessing, Ebal against Gerizim; and declared that all men ‘naturally’ desired their neighbours’ goods; and that in the name of Covetousness, all the nations of the earth should be blessed,—it is true, that the half-bred and half-witted Scotchman had not gift enough in him to carve so much as his own calf’s head on a whinstone with his own hand; much less to produce a well molten and forged piece of gold, for old Scottish faith to break its tables of ten commandments at sight of. But, in leaving to every artless and ignorant boor among us the power of breeding, in imagination, each his own particular calf, and placidly worshipping that privately fatted animal; or, perhaps,—made out of the purest fat of it in molten Tallow instead of molten Gold,—images, which may be in any inventive moment, misshapen anew to his mind, Economical Theology has granted its disciples more perfect and fitting privilege.

From all taint or compliance with such idolatry, the [48]Companions of St. George have vowed to withdraw themselves; writing, and signing their submission to, the First and great Commandment, so called by Christ,—and the Second which is like unto it.

And since on these two hang all the Law and the Prophets, in signing these two promises they virtually vow obedience to all the Law of which Christ then spoke; and belief of all the Prophets of which Christ then spoke. What that law is; who those prophets are;—whether they only prophesied ‘until John,’ or whether St. Paul’s command to all Christians living, “Follow after charity, and desire spiritual gifts, but rather that ye may prophesy,”—is an important little commandment following the two great ones, I cannot tell you in a single letter, even if I altogether knew myself. Partly I do know;—and can teach you, if you will work. No one can teach you anything worth learning but through manual labour; the very bread of life can only be got out of the chaff of it by “rubbing it in your hands.”

You vow, then, that you will at least strive to keep both of these commandments—as far as, what some would call the corruption, but what in honest people is the weakness, of flesh, permits. If you cannot watch an hour, because you don’t love Christ enough to care about His agony, that is your weakness; but if you first sell Him, and then kiss Him, that is your corruption. I don’t know if I can keep either you or myself [49]awake; but at least we may put a stop to our selling and kissing. Be sure that you are serving Christ, till you are tired and can do no more, for that time: and then, even if you have not breath enough left to say “Master, Master” with,—He will not mind.

Begin therefore ‘to-day,’—(which you may, in passing, note to be your present leader’s signal-word or watch-word),—to do good work for Him—whether you live or die,—(see first promise asked of you, Letter II., page 21, explained in Letter VII., page 19, etc.,)—and see that every stroke of this work—be it weak or strong, shall therefore be done in love of God and your neighbour, and in hatred of covetousness. Which that you may hate accurately, wisely, and well, it is needful that you should thoroughly know, when you see it, or feel it. What covetousness is, therefore, let me beg you at once clearly to understand, by meditating on these following definitions.

Avarice means the desire to collect money, not goods. A ‘miser’ or ‘miserable person’ desires to collect goods only for the sake of turning them into money. If you can read French or German, read Molière’s l’Avare, and then get Gotthelf’s ‘Bernese Stories,’ and read ‘Schnitzfritz,’ with great care.

Avarice is a quite natural passion, and, within due limits, healthy. The addition of coin to coin, and of cipher to cipher, is a quite proper pleasure of human life, under due rule; the two stories I ask you to read [50]are examples of its disease; which arises mainly in strong and stupid minds, when by evil fortune they have never been led to think or feel.

Frugality. The disposition to save or spare what we have got, without any desire to gain more. It is constantly, of course, associated with avarice; but quite as frequently with generosity, and is often merely an extreme degree of housewifely habit. Study the character of Alison Wilson in ‘Old Mortality.’

Covetousness. The desire of possessing more than we have, of any good thing whatsoever of which we have already enough for our uses, (adding house to house, and field to field). It is much connected with pride; but more with restlessness of mind and desire of novelty; much seen in children who tire of their toys and want new ones. The pleasure in having things ‘for one’s very own’ is a very subtle element in it. When I gave away my Loire series of Turner drawings to Oxford, I thought I was rational enough to enjoy them as much in the University gallery as in my own study. But not at all! I find I can’t bear to look at them in the gallery, because they are ‘mine’ no more.

Now, you observe, that your creed of St. George says you believe in the nobleness of human nature—that is to say, that all our natural instincts are honourable. Only it is not always easy to say which of them are natural and which not. [51]

For instance, Adam Smith says that it is ‘natural’ for every person to covet his neighbour’s goods, and want to change his own for them; wherein is the origin of Trade, and Universal Salvation.

But God says, ‘Thou shalt not covet thy neighbour’s goods;’ and God, who made you, does in that written law express to you His knowledge of your inner heart, and instruct you in the medicine for it. Therefore on due consideration, you will find assuredly it is quite unnatural in you to covet your neighbour’s goods.

Consider, first, of the most precious, the wife. It is natural for you to think your own the best and prettiest of women; not at all to want to change her for somebody else’s wife. If you like somebody else’s better than yours, and this somebody else likes yours better than his, and you both want to change, you are both in a non-natural condition, and entirely out of the sphere of happy human love.

Again. It is natural for you to think your own house and garden the nicest house and garden that ever were. If, as should always be, they were your father’s before you, and he and you have both taken proper care of them, they are a treasure to you which no money could buy,—the leaving them is always pain,—the return to them, a new thrill and wakening to life. They are a home and place of root to you, as if you were founded on the ground like its walls, or grew into it like its flowers. You would no more [52]willingly transplant yourself elsewhere than the espalier pear-tree of your own graffing would pull itself out by the roots to climb another trellis. That is the natural mind of a man. “Thou shalt not covet thy neighbour’s house.” You are in an entirely non-natural state if you do, and, properly speaking, never had a house in your life.

“Nor his man-servant, nor his maid-servant.” It is a ‘natural’ thing for masters to get proud of those who serve them; and a ‘natural’ thing for servants to get proud of the masters they serve. (You see above how Bacon connects the love of the master with the love of the country.) Nay, if the service has been true, if the master has indeed asked for what was good for himself, and the servant has done what was good for his master, they cannot choose but like each other; to have a new servant, or a new master, would be a mere horror to both of them. I have got two Davids, and a Kate, that I wouldn’t change for anybody else’s servants in the world; and I believe the only quarrel they have with me is that I don’t give them enough to do for me:—this very morning, I must stop writing, presently, to find the stoutest of the Davids some business, or he will be miserable all day.

“Nor his ox, nor his ass.” If you have petted both of your own, properly, from calf and foal, neither these, nor anything else of yours, will you desire to change [53]for “anything that is his.” Do you really think I would change my pen for your’s, or my inkstand, or my arm-chair, or my Gainsborough little girl, or my Turner pass of St. Gothard? I would see you—— very uncomfortable—first. And that is the natural state of a human being who has taken anything like proper pains to make himself comfortable in God’s good world, and get some of the right good, and true wealth of it.

For, you observe farther, the commandment is only that thou shalt not covet thy neighbour’s goods. It does not say that you are not to covet any goods. How could you covet your neighbour’s, if both your neighbour and you were forbidden to have any? Very far the contrary; in the first piece of genealogic geography I have given you to learn, the first descriptive sentence of the land of Havilah is,—“where there is gold;” and it goes on to say, “And the gold of that land is of the best: there is bdellium, and the onyx stone.” In the Vulgate, ‘dellium’ and ‘lapis onichinus.’ In the Septuagint, ‘anthrax,’ and the ‘prase-stone.’

Now, my evangelical friends, here is this book which you call “Word of God,” and idolatrously print for your little children’s reading and your own, as if your eternal lives depended on every word of it. And here, of the very beginning of the world—and the beginning of property—it professes to tell you something. [54]But what? Have you the smallest idea what ‘dellium’ is? Might it not as well be bellium, or gellium, or pellium, or mellium, for all you know about it? Or do you know what an onyx is? or an anthrax? or a prase? Is not the whole verse pure and absolute gibberish and gabble to you; and do you expect God will thank you for talking gibberish and gabble to your children, and telling them—that is His Word? Partly, however, the verse is only senseless to you, because you have never had the sense to look at the stones which God has made. But in still greater measure, it is necessarily senseless, because it is not the word of God, but an imperfectly written tradition, which, however, being a most venerable and precious tradition, you do well to make your children read, provided also you take pains to explain to them so much sense as there is in it, and yourselves do reverently obey so much law as there is in it. Towards which intelligence and obedience, we will now take a step or two farther from the point of pause in last Fors.

Remember that the three sons of Noah are, respectively,

| Shem, | the father of the Imaginative and Contemplative races. |

| Japheth, | the,, father,, of,, the,, Practical and Constructive. |

| Ham, | the,, father,, of,, the,, Carnal and Destructive. |

The sons of Shem are the perceivers of Splendour;[55]—they see what is best in visible things, and reach forward to the invisible.

The sons of Japheth are the perceivers of Justice and Duty; and deal securely with all that is under their hand.

The sons of Ham are the perceivers of Evil or Nakedness; and are slaves therefore for ever—‘servants of servants’: when in power, therefore, either helpless or tyrannous.

It is best to remember among the nations descending from the three great sires, the Persians, as the sons of Shem; Greeks, as the sons of Japheth; Assyrians, as the sons of Ham. The Jewish captivity to the Assyrian then takes its perfect meaning.

This month, therefore, take the first descendant of Ham—Cush; and learn the following verses of Gen. x.:—

“And Cush begat Nimrod; he began to be a mighty one in the earth.

“He was a mighty hunter before the Lord.

“And the beginning of his kingdom was Babel in the land of Shinar.

“Out of that land went forth Asshur, and builded Nineveh.”

These verses will become in future a centre of thought to you, whereupon you may gather, as on one root-germ, what you farther learn of the influence of hunting on [56]the minds of men; and of the sources of Assyrian power, and causes of the Assyrian ruin in Birs Nemroud, out of which you have had those hunting-pieces brought to the narrow passage in the British Museum.

For further subject of thought, this month, read of Carey’s Dante, the 31st canto of the ‘Inferno,’ with extreme care; and for your current writing lesson, copy these lines of Italics, which I have printed in as close resemblance as I can to the Italics of the Aldine edition of 1502.

| P | ero che come in su la cerchia tonda |

| Monte reggion di torri si corona, | |

| Cosi la proda che’l pozzo circonda | |

| T | orregiavan di mezza la persona |

| Gli orribili giganti; cui minaccia | |

| Giove del cielo anchora, quando tona. |