Footnotes have been collected at the end of each act,

and are linked for ease of reference.

Minor errors, attributable to the printer, have been corrected. Please

see the transcriber’s note at the end of this text

for details regarding the handling of any other textual issues encountered

during its preparation.

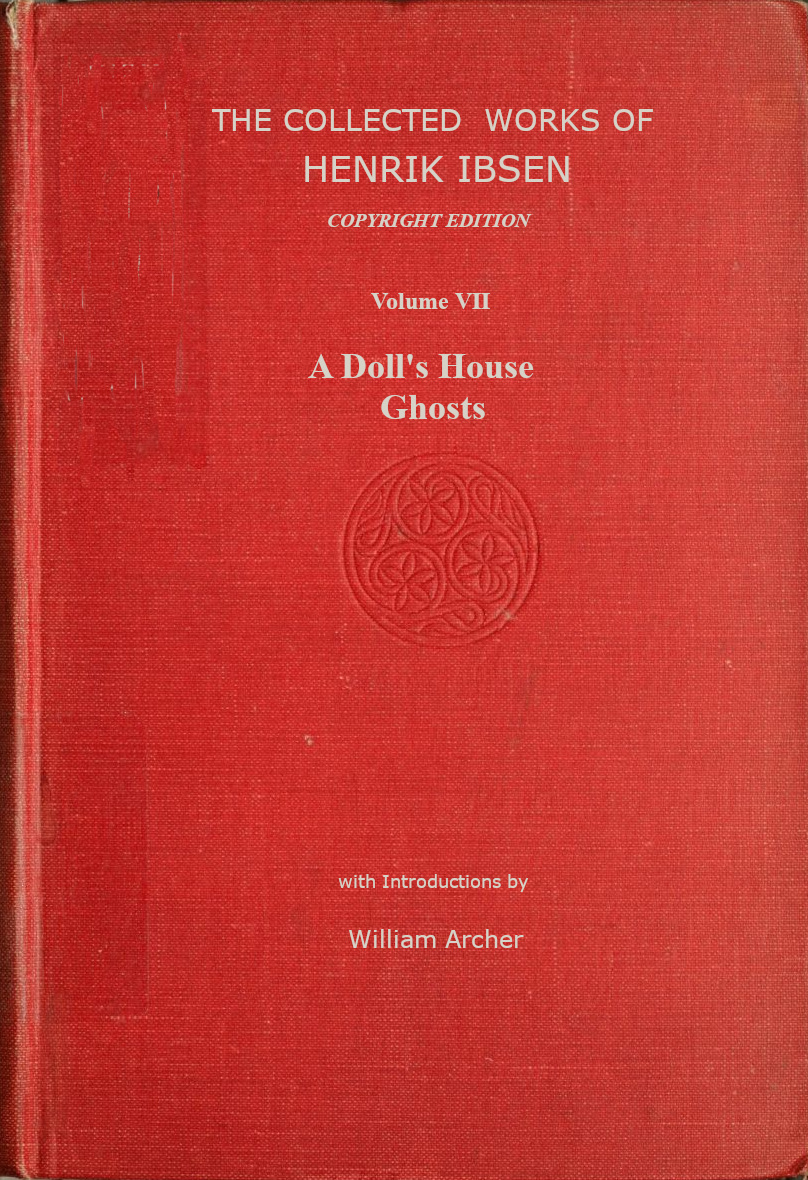

The front cover, which had only an embossed decoration, has been augmented

with information from the title page, and, as such, is added to the

public domain.

Any corrections are indicated using an underline

highlight. Placing the cursor over the correction will produce the

original text in a small popup.

Any corrections are indicated as hyperlinks, which will navigate the

reader to the corresponding entry in the corrections table in the

note at the end of the text.

THE COLLECTED WORKS OF

HENRIK IBSEN

THE COLLECTED WORKS OF

HENRIK IBSEN

Copyright Edition. Complete in 11 Volumes.

Crown 8vo, price 4s. each.

ENTIRELY REVISED AND EDITED BY

WILLIAM ARCHER

| Vol. I. |

Lady Inger, The Feast at Solhoug, Love’s Comedy |

| Vol. II. |

The Vikings, The Pretenders |

| Vol. III. |

Brand |

| Vol. IV. |

Peer Gynt |

| Vol. V. |

Emperor and Galilean (2 parts) |

| Vol. VI. |

The League of Youth, Pillars of Society |

| Vol. VII. |

A Doll’s House, Ghosts |

| Vol. VIII. |

An Enemy of the People, The Wild Duck |

| Vol. IX. |

Rosmersholm, The Lady from the Sea |

| Vol. X. |

Hedda Gabler, The Master Builder |

| Vol. XI. |

Little Eyolf, John Gabriel Borkman, When We Dead Awaken |

London: WILLIAM HEINEMANN.

21 Bedford Street, W.C.

THE COLLECTED WORKS OF

HENRIK IBSEN

VOLUME VII

A DOLL’S HOUSE

GHOSTS

WITH INTRODUCTIONS BY

WILLIAM ARCHER

LONDON

WILLIAM HEINEMANN

1909

Collected Edition first printed 1906

Second Impression 1909

Copyright 1906 by William Heinemann

CONTENTS

| |

PAGE |

| |

| Introduction to “A Doll’s House” |

vii |

| |

| Introduction to “Ghosts” |

xvii |

| |

| “A Doll’s House” |

1 |

| Translated by William Archer |

|

| “Ghosts” |

157 |

| Translated by William Archer |

|

vii

A DOLL’S HOUSE.

INTRODUCTION.

On June 27, 1879, Ibsen wrote from Rome to Marcus

Grönvold: “It is now rather hot in Rome, so in about

a week we are going to Amalfi, which, being close to

the sea, is cooler, and offers opportunity for bathing.

I intend to complete there a new dramatic work on

which I am now engaged.” From Amalfi, on September

20, he wrote to John Paulsen: “A new

dramatic work, which I have just completed, has

occupied so much of my time during these last months

that I have had absolutely none to spare for answering

letters.” This “new dramatic work” was Et

Dukkehjem, which was published in Copenhagen,

December 4, 1879. Dr. George Brandes has given

some account of the episode in real life which suggested

to Ibsen the plot of this play; but the real Nora,

it appears, committed forgery, not to save her husband’s

life, but to redecorate her house. The impulse

received from this incident must have been trifling. It

is much more to the purpose to remember that the

character and situation of Nora had been clearly foreshadowed,

ten years earlier, in the figure of Selma in

The League of Youth.

It is with A Doll’s House that Ibsen enters upon

viiihis kingdom as a world-poet. He had done greater

work in the past, and he was to do greater work in

the future; but this was the play which was destined

to carry his name beyond the limits of Scandinavia,

and even of Germany, to the remotest regions of civilisation.

Here the Fates were not altogether kind to

him. The fact that for many years he was known to

thousands of people solely as the author of A Doll’s

House, and its successor, Ghosts, was largely responsible

for the extravagant misconceptions of his genius and

character which prevailed during the last decade of

the nineteenth century, and are not yet entirely

extinct. In these plays he seemed to be delivering

a direct assault on marriage, from the standpoint of

feminine individualism; wherefore he was taken to

be a preacher and pamphleteer rather than a poet. In

these plays, and in these only, he made physical disease

a considerable factor in the action; whence it was

concluded that he had a morbid predilection for

“nauseous” subjects. In these plays he laid special

and perhaps disproportionate stress on the influence

of heredity; whence he was believed to be possessed

by a monomania on the point. In these plays, finally,

he was trying to act the essentially uncongenial part

of the prosaic realist. The effort broke down at many

points, and the poet reasserted himself; but these

flaws in the prosaic texture were regarded as mere

bewildering errors and eccentricities. In short, he

was introduced to the world at large through two

plays which showed his power, indeed, almost in perfection,

but left the higher and subtler qualities of

his genius for the most part unrepresented. Hence

the grotesquely distorted vision of him which for so

long haunted the minds even of intelligent people.

ixHence, for example, the amazing opinion, given forth

as a truism by more than one critic of great ability,

that the author of Peer Gynt was devoid of humour.

Within a little more than a fortnight of its publication

A Doll’s House was presented at the Royal

Theatre, Copenhagen, where Fru Hennings, as Nora,

made the great success of her career. The play was

soon being acted, as well as read, all over Scandinavia.

Nora’s startling “declaration of independence”

afforded such an inexhaustible theme for heated discussion,

that at last it had to be formally barred at

social gatherings, just as, in Paris twenty years later,

the Dreyfus Case was proclaimed a prohibited topic.

The popularity of Pillars of Society in Germany had

paved the way for its successor, which spread far and

wide over the German stage in the spring of 1880,

and has ever since held its place in the repertory of

the leading theatres. As his works were at that

time wholly unprotected in Germany, Ibsen could not

prevent managers from altering the end of the play to

suit their taste and fancy. He was thus driven, under

protest, to write an alternative ending, in which, at the

last moment, the thought of her children restrained

Nora from leaving home. He preferred, as he said,

“to commit the outrage himself, rather than leave

his work to the tender mercies of adapters.” The

patched-up ending soon dropped out of use and out of

memory. Ibsen’s own account of the matter will be

found in his Correspondence, Letter 142.

It took ten years for the play to pass beyond

the limits of Scandinavia and Germany. Madame

Modjeska, it is true, presented a version of it in

Louisville, Kentucky, in 1883, but it attracted no

attention. In the following year Messrs. Henry

xArthur Jones and Henry Herman produced at the

Prince of Wales’s Theatre, London, a play entitled

Breaking a Butterfly, which was described as being

“founded on Ibsen’s Norah” but bore only a remote

resemblance to the original. In this production Mr.

Beerbohm Tree took the part of Dunkley, a melodramatic

villain who filled the place of Krogstad. In

1885, again, an adventurous amateur club gave a quaint

performance of Miss Lord’s translation of the play

at a hall in Argyle Street, London. Not until June 7,

1889, was a A Doll’s House competently, and even

brilliantly, presented to the English public, by Mr.

Charles Charrington and Miss Janet Achurch, at the

Novelty Theatre, London, afterwards re-named the

Great Queen Street Theatre. It was this production

that really made Ibsen known to the English-speaking

peoples. In other words, it marked his second great

stride towards world-wide, as distinct from merely

national, renown—if we reckon as the first stride the

success of Pillars of Society in Germany. Mr. and

Mrs. Charrington took A Doll’s House with them on

a long Australian tour; Miss Beatrice Cameron

(Mrs. Richard Mansfield) was encouraged by the success

of the London production to present the play in

New York, whence it soon spread to other American

cities; while in London itself it was frequently

revived and vehemently discussed. The Ibsen controversy,

indeed, did not break out in its full virulence

until 1891, when Ghosts and Hedda Gabler were produced

in London; but from the date of the Novelty

production onwards, Ibsen was generally recognised

as a potent factor in the intellectual and artistic life

of the day.

A French adaptation of Et Dukkehjem was produced

xiin Brussels in March 1889, but attracted little

attention. Not until 1894 was the play introduced to

the Parisian public, at the Gymnase, with Madame

Réjane as Nora. This actress has since played the

part frequently, not only in Paris but in London and

in America. In Italian the play was first produced

in 1889, and soon passed into the repertory of Eleonora

Duse, who appeared as Nora in London in 1893. Few

heroines in modern drama have been played by so

many actresses of the first rank. To those already

enumerated must be added Hedwig Niemann-Raabe

and Agnes Sorma in Germany, and Minnie Maddern-Fiske

in America; and, even so, the list is far from

complete. There is probably no country in the world,

possessing a theatre on the European model, in which

A Doll’s House has not been more or less frequently

acted.

Undoubtedly the great attraction of the part of

Nora to the average actress was the tarantella scene.

This was a theatrical effect, of an obvious, unmistakable

kind. It might have been—though I am not

aware that it ever actually was—made the subject of

a picture-poster. But this, as it seems to me, was

Ibsen’s last concession to the ideal of technique which

he had acquired, in the old Bergen days, from his

French masters. I have elsewhere[1] analysed A

Doll’s House at some length, from the technical point

of view, suggesting that it marks a distinct, and one

might almost say a sudden, revolution in the poet’s

understanding of the methods and aims of his art.

There is pretty good reason to suppose, as it seems to

me, that he altered the plan of the play while it

was actually in process of composition. He seems

xiioriginally to have schemed a “happy ending,” like

that of The League of Youth or Pillars of Society.

No doubt it is convenient, even for the purposes of

the play as it stands, that all fear of hostile action on

Krogstad’s part should be dissipated before Nora and

Helmer settle down to their final explanation; but is

the convenience sufficiently great to account for the

invention, to that end alone, of Mrs. Linden’s relation

to, and influence over, Krogstad? I very much question

it. I think the “happy ending” which is actually

reached when Krogstad returns the forged document

was, in Ibsen’s original conception, intended to be

equivalent to the stopping of the Indian Girl, and the

return of Olaf, in Pillars of Society—that is to say,

it was to be the end of the drama properly so

called, and the rest was to be a more or less

conventional winding-up, a confession of faults on

both sides, accompanied by mutual congratulations

on the blowing-over of the threatened storm. This

is the end which, as we see, every one expected: the

end which adapters, in Germany, England, and elsewhere,

insisted on giving to the play. There was just

a shade of excuse for these gentlemen, inasmuch as

the poet himself seemed to have elaborately prepared

the way for them; and I suggest that the fact of his

having done so shows that the play, in embryo, passed

through the phase of technical development represented

by Pillars of Society—the phase to which its

amenders would have forced it to return. Ibsen, on

the other hand, when he proceeded from planning in

outline to creation in detail, found his characters outgrow

his plot. When the action, in the theatrical

sense, was over, they were only on the threshold of

the essential drama; and in that drama, compressed

xiiiinto the final scene of the play, Ibsen found his true

power and his true mission.

How impossible, in his subsequent work, would be

such figures as Mrs. Linden, the confidant, and Krogstad,

the villain! They are not quite the ordinary

confidant and villain, for Ibsen is always Ibsen, and

his power of vitalisation is extraordinary. Yet we

clearly feel them to belong to a different order of art

from that of his later plays. How impossible, too, in

the poet’s after years, would have been the little

tricks of ironic coincidence and picturesque contrast

which abound in A Doll’s House! The festal atmosphere

of the whole play, the Christmas-tree, the

tarantella, the masquerade ball, with its distant sounds

of music—all the shimmer and tinsel of the background

against which Nora’s soul-torture and Rank’s despair

are thrown into relief belong to the system of external,

artificial antithesis beloved by romantic playwrights

from Lope de Vega onward, and carried to its limit

by Victor Hugo. The same artificiality is apparent

in minor details. “Oh, what a wonderful thing it is

to live to be happy!” cries Nora, and instantly “The

hall-door bell rings” and Krogstad’s shadow falls

across the threshold. So, too, for his second entrance,

an elaborate effect of contrast is arranged, between

Nora’s gleeful romp with her children and the

sinister figure which stands unannounced in their

midst. It would be too much to call these things

absolutely unnatural, but the very precision of the coincidence

is eloquent of pre-arrangement. At any rate,

they belong to an order of effects which in future

Ibsen sedulously eschews. The one apparent exception

to this rule which I can remember occurs in The

Master Builder, where Solness’s remark, “Presently the

xivyounger generation will come knocking at my door,”

gives the cue for Hilda’s knock and entrance. But

here an interesting distinction is to be noted.

Throughout The Master Builder the poet subtly indicates

the operation of mysterious, unseen agencies—the

“helpers and servers” of whom Solness speaks,

as well as the Power with which he held converse

at the crisis in his life—guiding, or at any rate

tampering with, the destinies of the characters.

This being so, it is evident that the effect of pre-arrangement

produced by Hilda’s appearing exactly

on the given cue was deliberately aimed at. Like so

many other details in the play, it might be a mere

coincidence, or it might be a result of inscrutable

design—we were purposely left in doubt. But the

suggestion of pre-arrangement which helped to create

the atmosphere of the The Master Builder was wholly

out of place in A Doll’s House. In the later play it

was a subtle stroke of art; in the earlier it was the

effect of imperfectly dissembled artifice.

My conjecture of an actual modification of Ibsen’s

design during the progress of the play may possibly

be mistaken. There can be no doubt, on the other

hand, that Ibsen’s full originality first reveals itself

in the latter half of the third act. This is proved by

the very protests, nay, the actual rebellion, which the

last scene called forth. Up to that point he had been

doing, approximately, what theatrical orthodoxy

demanded of him. But when Nora, having put off

her masquerade dress, returned to make up her

account with Helmer, and with marriage as Helmer

understood it, the poet flew in the face of orthodoxy,

and its professors cried out in bewilderment and

wrath. But it was just at this point that, in practice,

xvthe real grip and thrill of the drama were found to

come in. The tarantella scene never, in my experience—and

I have seen five or six great actresses in the

part—produced an effect in any degree commensurate

with the effort involved. But when Nora and Helmer

faced each other, one on each side of the table, and set

to work to ravel out the skein of their illusions, then

one felt oneself face to face with a new thing in

drama—an order of experience, at once intellectual

and emotional, not hitherto attained in the theatre.

This every one felt, I think, who was in any way

accessible to that order of experience. For my own

part, I shall never forget how surprised I was on first

seeing the play, to find this scene, in its naked simplicity,

far more exciting and moving than all the

artfully-arranged situations of the earlier acts. To

the same effect, from another point of view, we have

the testimony of Fru Hennings, the first actress who

ever played the part of Nora. In an interview published

soon after Ibsen’s death, she spoke of the

delight it was to her, in her youth, to embody the

Nora of the first and second acts, the “lark,” the

“squirrel,” the irresponsible, butterfly Nora. “When

I now play the part,” she went on, “the first acts

leave me indifferent. Not until the third act am I

really interested—but then, intensely.” To call the

first and second acts positively uninteresting would of

course be a gross exaggeration. What one really

means is that their workmanship is still a little derivative

and immature, and that not until the third

act does the poet reveal the full originality and

individuality of his genius.

xvii

GHOSTS.

INTRODUCTION.

The winter of 1879-80 Ibsen spent in Munich, and

the greater part of the summer of 1880 at Berchtesgaden.

November 1880 saw him back in Rome, and

he passed the summer of 1881 at Sorrento. There,

fourteen years earlier, he had written the last acts of

Peer Gynt; there he now wrote, or at any rate completed,

Gengangere. It was published in December

1881, after he had returned to Rome. On December 22

he wrote to Ludwig Passarge, one of his German

translators, “My new play has now appeared, and has

occasioned a terrible uproar in the Scandinavian press;

every day I receive letters and newspaper articles

decrying or praising it.... I consider it utterly impossible

that any German theatre will accept the play

at present. I hardly believe that they will dare to

play it in the Scandinavian countries for some time to

come.” How rightly he judged we shall see anon.

In the newspapers there was far more obloquy than

praise. Two men, however, stood by him from the

first: Björnson, from whom he had been practically

estranged ever since The League of Youth, and George

Brandes. The latter published an article in which he

xviiideclared (I quote from memory) that the play might

or might not be Ibsen’s greatest work, but that it was

certainly his noblest deed. It was, doubtless, in

acknowledgment of this article that Ibsen wrote to

Brandes on January 3, 1882: “Yesterday I had the

great pleasure of receiving your brilliantly clear and

so warmly appreciative review of Ghosts.... All

who read your article must, it seems to me, have their

eyes opened to what I meant by my new book—assuming,

that is, that they have any wish to see. For I

cannot get rid of the impression that a very large

number of the false interpretations which have appeared

in the newspapers are the work of people who

know better. In Norway, however, I am willing to

believe that the stultification has in most cases been

unintentional; and the reason is not far to seek. In

that country a great many of the critics are theologians,

more or less disguised; and these gentlemen

are, as a rule, quite unable to write rationally about

creative literature. That enfeeblement of judgment

which, at least in the case of the average man, is an

inevitable consequence of prolonged occupation with

theological studies, betrays itself more especially in

the judging of human character, human actions, and

human motives. Practical business judgment, on the

other hand, does not suffer so much from studies of

this order. Therefore the reverend gentlemen are

very often excellent members of local boards; but

they are unquestionably our worst critics.” This

passage is interesting as showing clearly the point of

view from which Ibsen conceived the character of

Manders. In the next paragraph of the same letter

he discusses the attitude of “the so-called Liberal

press”; but as the paragraph contains the germ of

xixAn Enemy of the People, it may most fittingly be

quoted in the introduction to that play.

Three days later (January 6) Ibsen wrote to Schandorph,

the Danish novelist: “I was quite prepared

for the hubbub. If certain of our Scandinavian reviewers

have no talent for anything else, they have an

unquestionable talent for thoroughly misunderstanding

and misinterpreting those authors whose books

they undertake to judge.... They endeavour to

make me responsible for the opinions which certain of

the personages of my drama express. And yet there

is not in the whole book a single opinion, a single

utterance, which can be laid to the account of the

author. I took good care to avoid this. The very

method, the order of technique which imposes its

form upon the play, forbids the author to appear in

the speeches of his characters. My object was to make

the reader feel that he was going through a piece of

real experience; and nothing could more effectually

prevent such an impression than the intrusion of the

author’s private opinions into the dialogue. Do they

imagine at home that I am so inexpert in the theory

of drama as not to know this? Of course I know it,

and act accordingly. In no other play that I have

written is the author so external to the action, so

entirely absent from it, as in this last one.”

“They say,” he continued, “that the book preaches

Nihilism. Not at all. It is not concerned to preach

anything whatsoever. It merely points to the ferment

of Nihilism going on under the surface, at home

as elsewhere. A Pastor Manders will always goad

one or other Mrs. Alving to revolt. And just because

she is a woman, she will, when once she has begun, go

to the utmost extremes.”

xxTowards the end of January Ibsen wrote from

Rome to Olaf Skavlan: “These last weeks have

brought me a wealth of experiences, lessons, and discoveries.

I, of course, foresaw that my new play

would call forth a howl from the camp of the stagnationists;

and for this I care no more than for the

barking of a pack of chained dogs. But the pusillanimity

which I have observed among the so-called

Liberals has given me cause for reflection. The very

day after my play was published the Dagblad rushed

out a hurriedly-written article, evidently designed to

purge itself of all suspicion of complicity in my work.

This was entirely unnecessary. I myself am responsible

for what I write, I and no one else. I cannot

possibly embarrass any party, for to no party do

I belong. I stand like a solitary franc-tireur at the

outposts, and fight for my own hand. The only man

in Norway who has stood up freely, frankly, and

courageously for me is Björnson. It is just like him.

He has in truth a great, kingly soul, and I shall never

forget his action in this matter.”

One more quotation completes the history of these

stirring January days, as written by Ibsen himself. It

occurs in a letter to a Danish journalist, Otto Borchsenius.

“It may well be,” the poet writes, “that the

play is in several respects rather daring. But it seemed

to me that the time had come for moving some

boundary-posts. And this was an undertaking for

which a man of the older generation, like myself, was

better fitted than the many younger authors who might

desire to do something of the kind. I was prepared

for a storm; but such storms one must not shrink

from encountering. That would be cowardice.”

It happened that, just in these days, the present

xxiwriter had frequent opportunities of conversing with

Ibsen, and of hearing from his own lips almost all the

views expressed in the above extracts. He was

especially emphatic, I remember, in protesting against

the notion that the opinions expressed by Mrs. Alving

or Oswald were to be attributed to himself. He

insisted, on the contrary, that Mrs. Alving’s views

were merely typical of the moral chaos inevitably

produced by re-action from the narrow conventionalism

represented by Manders.

With one consent, the leading theatres of the three

Scandinavian capitals declined to have anything to do

with the play. It was more than eighteen months old

before it found its way to the stage at all. In August

1883 it was acted for the first time at Helsingborg,

Sweden, by a travelling company under the direction

of an eminent Swedish actor, August Lindberg, who

himself played Oswald. He took it on tour round

the principal cities of Scandinavia, playing it, among

the rest, at a minor theatre in Christiania. It

happened that the boards of the Christiania Theatre

were at the same time occupied by a French farce;

and public demonstrations of protest were made

against the managerial policy which gave Tête de

Linotte the preference over Gengangere. Gradually

the prejudice against the play broke down. Already

in the autumn of 1883 it was produced at the Royal

(Dramatiska) Theatre in Stockholm. When the new

National Theatre was opened in Christiania in 1899,

Gengangere found an early place in its repertory; and

even the Royal Theatre in Copenhagen has since

opened its doors to the tragedy.

Not until April 1886 was Gespenster acted in

Germany, and then only at a private performance, at

xxiithe Stadttheater, Augsburg, the poet himself being

present. In the following winter it was acted at the

famous Court Theatre at Meiningen, again in the

presence of the poet. The first (private) performance

in Berlin took place on January 9, 1887, at the

Residenz Theater; and when the Freie Bühne,

founded on the model of the Paris Théâtre Libre,

began its operations two years later (September 29,

1889), Gespenster was the first play that it produced.

The Freie Bühne gave the initial impulse to the

whole modern movement which has given Germany a

new dramatic literature; and the leaders of the

movement, whether authors or critics, were one and

all ardent disciples of Ibsen, who regarded Gespenster

as his typical masterpiece. In Germany, then, the

play certainly did, in Ibsen’s own words, “move

some boundary-posts.” The Prussian censorship,

presently withdrew its veto, and on November 27,

1894, the two leading literary theatres of Berlin, the

Deutsches Theater and the Lessing Theater, gave

simultaneous performances of the tragedy. Everywhere

in Germany and Austria it is now freely performed;

but it is naturally one of the least popular

of Ibsen’s plays.

It was with Les Revenants that Ibsen made his

first appearance on the French stage. The play was

produced by the Théâtre Libre (at the Théâtre des

Menus-Plaisirs) on May 29, 1890. Here, again, it

became the watchword of the new school of authors

and critics, and aroused a good deal of opposition

among the old school. But the most hostile French

criticisms were moderation itself compared with the

torrents of abuse which were poured upon Ghosts by

the journalists of London when, on March 13, 1891,

xxiiithe Independent Theatre, under the direction of Mr.

J. T. Grein, gave a private performance of the play

at the Royalty Theatre, Soho. I have elsewhere[2]

placed upon record some of the amazing feats of

vituperation achieved of the critics, and will not here

recall them. It is sufficient to say that if the play

had been a tenth part as nauseous as the epithets

hurled at it and its author, the Censor’s veto would

have been amply justified. That veto is still (1906)

in force. England enjoys the proud distinction of

being the one country in the world where Ghosts may

not be publicly acted.

In the United States, the first performance of the

play in English took place at the Berkeley Lyceum,

New York City, on January 5, 1894. The production

was described by Mr. W. D. Howells as “a great

theatrical event—the very greatest I have ever known.”

Other leading men of letters were equally impressed

by it. Five years later, a second production took

place at the Carnegie Lyceum; and an adventurous

manager has even taken the play on tour in the United

States. The Italian version of the tragedy, Gli Spettri,

has ever since 1892 taken a prominent place in the

repertory of the great actors Zaccone and Novelli,

who have acted it, not only throughout Italy, but in

Austria, Germany, Russia, Spain, and South America.

In an interview, published immediately after Ibsen’s

death, Björnstjerne Björnson, questioned as to what

he held to be his brother-poet’s greatest work, replied,

without a moment’s hesitation, Gengangere. This

xxivdictum can scarcely, I think, be accepted without

some qualification. Even confining our attention to

the modern plays, and leaving out of comparison The

Pretenders, Brand, and Peer Gynt, we can scarcely call

Ghosts Ibsen’s richest or most human play, and certainly

not his profoundest or most poetical. If some

omnipotent Censorship decreed the annihilation of all

his works save one, few people, I imagine, would vote

that that one should be Ghosts. Even if half a dozen

works were to be saved from the wreck, I doubt

whether I, for my part, would include Ghosts in the

list. It is, in my judgment, a little bare, hard, austere.

It is the first work in which Ibsen applies his new

technical method—evolved, as I have suggested, during

the composition of A Doll’s House—and he applies it

with something of fanaticism. He is under the sway

of a prosaic ideal—confessed in the phrase, “My

object was to make the reader feel that he was going

through a piece of real experience”—and he is putting

some constraint upon the poet within him. The

action moves a little stiffly, and all in one rhythm.

It lacks variety and suppleness. Moreover, the play

affords some slight excuse for the criticism which

persists in regarding Ibsen as a preacher rather than

as a creator—an author who cares more for ideas and

doctrines than for human beings. Though Mrs.

Alving, Engstrand and Regina are rounded and

breathing characters, it cannot be denied that

Manders strikes one as a clerical type rather than

an individual, while even Oswald might not quite

unfairly be described as simply and solely his father’s

son, an object-lesson in heredity. We cannot be said

to know him, individually and intimately, as we know

Helmer or Stockmann, Hialmar Ekdal or Gregers

xxvWerle. Then, again, there are one or two curious

flaws in the play. The question whether Oswald’s

“case” is one which actually presents itself in the

medical books seems to me of very trifling moment.

It is typically true, even if it be not true in detail.

The suddenness of the catastrophe may possibly be

exaggerated, its premonitions and even its essential

nature may be misdescribed. On the other hand, I

conceive it probable that the poet had documents to

found upon, which may be unknown to his critics. I

have never taken any pains to satisfy myself upon

the point, which seems to me quite immaterial. There

is not the slightest doubt that the life-history of a

Captain Alving may, and often does, entail upon

posterity consequences quite as tragic as those which

ensue in Oswald’s case, and far more wide-spreading.

That being so, the artistic justification of the poets

presentment of the case is certainly not dependent on

its absolute scientific accuracy. The flaws above

alluded to are of another nature. One of them is

the prominence given to the fact that the Asylum is

uninsured. No doubt there is some symbolical purport

in the circumstance; but I cannot think that it is

either sufficiently clear or sufficiently important to

justify the emphasis thrown upon it at the end of the

second act. Another dubious point is Oswald’s argument

in the first act as to the expensiveness of

marriage as compared with free union. Since the

parties to free union, as he describes it, accept all

the responsibilities of marriage, and only pretermit

the ceremony, the difference of expense, one would

suppose, must be neither more nor less than the actual

marriage fee. I have never seen this remark of

Oswald’s adequately explained, either as a matter of

xxvieconomic fact, or as a trait of character. Another

blemish, of somewhat greater moment, is the inconceivable

facility with which, in the third act, Manders

suffers himself to be victimised by Engstrand. All

these little things, taken together, detract, as it seems

to me, from the artistic completeness of the play, and

impair its claim to rank as the poet’s masterpiece.

Even in prose drama, his greatest and most consummate

achievements were yet to come.

Must we, then, wholly dissent from Björnson’s

judgment? I think not. In a historical, if not in

an æsthetic, sense, Ghosts may well rank as Ibsen’s

greatest work. It was the play which first gave the

full measure of his technical and spiritual originality

and daring. It has done far more than any other of

his plays to “move boundary-posts.” It has advanced

the frontiers of dramatic art and implanted new

ideals, both technical and intellectual, in the minds of

a whole generation of playwrights. It ranks with

Hernani and La Dame aux Camélias among the epoch-making

plays of the nineteenth century, while in point

of essential originality it towers above them. We

cannot, I think, get nearer to the truth than George

Brandes did in the above-quoted phrase from his

first notice of the play, describing it as not, perhaps,

the poet’s greatest work, but certainly his noblest

deed. In another essay, Brandes has pointed to it,

with equal justice, as marking Ibsen’s final breach

with his early—one might almost say his hereditary—romanticism.

He here becomes, at last, “the most

modern of the moderns.” “This, I am convinced,”

says the Danish critic, “is his imperishable glory, and

will give lasting life to his works.”

W. A.

1

A DOLL’S HOUSE

2

CHARACTERS.

- Torvald Helmer.

- Nora, his wife.

- Doctor Rank.

- Mrs. Linden.[3]

- Nils Krogstad.

- The Helmers’ Three Children.

- Anna,[4] their nurse.

- A Maid-servant (Ellen).

- A Porter.

The action passes in Helmer’s house (a flat) in Christiania.

3

A DOLL’S HOUSE.

ACT FIRST.

A room, comfortably and tastefully, but not expensively,

furnished. In the back, on the right, a door leads

to the hall; on the left another door leads to

Helmer’s study. Between the two doors a

pianoforte. In the middle of the left wall a door,

and nearer the front a window. Near the window

a round table with arm-chairs and a small

sofa. In the right wall, somewhat to the back,

a door, and against the same wall, further forward,

a porcelain stove; in front of it a couple

of arm-chairs and a rocking-chair. Between the

stove and the side-door a small table. Engravings

on the walls. A what-not with china and bric-à-brac.

A small bookcase filled with handsomely

bound books. Carpet. A fire in the stove. It is

a winter day.

A bell rings in the hall outside. Presently the outer

door of the flat is heard to open. Then Nora

enters, humming gaily. She is in outdoor dress,

and carries several parcels, which she lays on the

right-hand table. She leaves the door into the

hall open, and a Porter is seen outside, carrying

a Christmas-tree and a basket, which he

gives to the Maid-servant who has opened the

door.

Hide the Christmas-tree carefully, Ellen; the

children must on no account see it before this

evening, when it’s lighted up. [To the Porter,

taking out her purse.] How much?

Fifty öre.[5]

There is a crown. No, keep the change.

[The Porter thanks her and goes. Nora

shuts the door. She continues smiling in

quiet glee as she takes off her outdoor

things. Taking from her pocket a bag of

macaroons, she eats one or two. Then she

goes on tip-toe to her husband’s door and

listens.

Yes; he is at home.

[She begins humming again, crossing to the

table on the right.

[In his room.] Is that my lark twittering there?

[Busy opening some of her parcels.] Yes, it is.

Is it the squirrel frisking around?

Yes!

When did the squirrel get home?

Just this minute. [Hides the bag of macaroons

in her pocket and wipes her mouth.] Come here,

Torvald, and see what I’ve been buying.

Don’t interrupt me. [A little later he opens the

door and looks in, pen in hand.] Buying, did you

say? What! All that? Has my little spendthrift

been making the money fly again?

Why, Torvald, surely we can afford to launch

out a little now. It’s the first Christmas we

haven’t had to pinch.

Come come; we can’t afford to squander money.

Oh yes, Torvald, do let us squander a little,

now—just the least little bit! You know you’ll

soon be earning heaps of money.

Yes, from New Year’s Day. But there’s a

whole quarter before my first salary is due.

Never mind; we can borrow in the meantime.

Nora! [He goes up to her and takes her playfully

by the ear.] Still my little featherbrain!

Supposing I borrowed a thousand crowns to-day,

and you made ducks and drakes of them during

Christmas week, and then on New Year’s Eve a

6tile blew off the roof and knocked my brains

out——

[Laying her hand on his mouth.] Hush! How

can you talk so horridly?

But supposing it were to happen—what then?

If anything so dreadful happened, it would be

all the same to me whether I was in debt or not.

But what about the creditors?

They! Who cares for them? They’re only

strangers.

Nora, Nora! What a woman you are! But

seriously, Nora, you know my principles on these

points. No debts! No borrowing! Home life

ceases to be free and beautiful as soon as it is

founded on borrowing and debt. We two have

held out bravely till now, and we are not going

to give in at the last.

[Going to the fireplace.] Very well—as you

please, Torvald.

[Following her.] Come come; my little lark

mustn’t droop her wings like that. What? Is

my squirrel in the sulks? [Takes out his purse.]

Nora, what do you think I have here?

[Turning round quickly.] Money!

There! [Gives her some notes.] Of course I

know all sorts of things are wanted at Christmas.

[Counting.] Ten, twenty, thirty, forty. Oh,

thank you, thank you, Torvald! This will go a

long way.

I should hope so.

Yes, indeed; a long way! But come here, and

let me show you all I’ve been buying. And so

cheap! Look, here’s a new suit for Ivar, and a

little sword. Here are a horse and a trumpet for

Bob. And here are a doll and a cradle for Emmy.

They’re only common; but they’re good enough

for her to pull to pieces. And dress-stuffs and

kerchiefs for the servants. I ought to have got

something better for old Anna.

And what’s in that other parcel?

[Crying out.] No, Torvald, you’re not to see

that until this evening!

Oh! Ah! But now tell me, you little spendthrift,

have you thought of anything for yourself?

For myself! Oh, I don’t want anything.

Nonsense! Just tell me something sensible you

would like to have.

No, really I don’t know of anything——Well,

listen, Torvald——

Well?

[Playing with his coat-buttons, without looking him

in the face.] If you really want to give me something,

you might, you know—you might——

Well? Out with it!

[Quickly.] You might give me money, Torvald.

Only just what you think you can spare; then I can

buy something with it later on.

But, Nora——

Oh, please do, dear Torvald, please do! I should

hang the money in lovely gilt paper on the

Christmas-tree. Wouldn’t that be fun?

What do they call the birds that are always

making the money fly?

Yes, I know—spendthrifts,[6] of course. But

please do as I ask you, Torvald. Then I shall

have time to think what I want most. Isn’t that

very sensible, now?

[Smiling.] Certainly; that is to say, if you

really kept the money I gave you, and really

spent it on something for yourself. But it all

goes in housekeeping, and for all manner of useless

things, and then I have to pay up again.

But, Torvald——

Can you deny it, Nora dear? [He puts his arm

round her.] It’s a sweet little lark, but it gets

through a lot of money. No one would believe

how much it costs a man to keep such a little

bird as you.

For shame! How can you say so? Why, I save

as much as ever I can.

[Laughing.] Very true—as much as you can—but

that’s precisely nothing.

[Hums and smiles with covert glee.] H’m! If

you only knew, Torvald, what expenses we larks

and squirrels have.

You’re a strange little being! Just like your

father—always on the look-out for all the money

10you can lay your hands on; but the moment you

have it, it seems to slip through your fingers; you

never know what becomes of it. Well, one must

take you as you are. It’s in the blood. Yes,

Nora, that sort of thing is hereditary.

I wish I had inherited many of papa’s qualities.

And I don’t wish you anything but just what

you are—my own, sweet little song-bird. But I

say—it strikes me you look so—so—what shall I

call it?—so suspicious to-day——

Do I?

You do, indeed. Look me full in the face.

[Looking at him.] Well?

[Threatening with his finger.] Hasn’t the little

sweet-tooth been playing pranks to-day?

No; how can you think such a thing!

Didn’t she just look in at the confectioner’s?

No, Torvald; really——

Not to sip a little jelly?

No; certainly not.

Hasn’t she even nibbled a macaroon or two?

No, Torvald, indeed, indeed!

Well, well, well; of course I’m only joking.

[Goes to the table on the right.] I shouldn’t think

of doing what you disapprove of.

No, I’m sure of that; and, besides, you’ve given

me your word——[Going towards her.] Well,

keep your little Christmas secrets to yourself,

Nora darling. The Christmas-tree will bring

them all to light, I daresay.

Have you remembered to invite Doctor Rank?

No. But it’s not necessary; he’ll come as a

matter of course. Besides, I shall ask him when

he looks in to-day. I’ve ordered some capital

wine. Nora, you can’t think how I look forward

to this evening.

And I too. How the children will enjoy themselves,

Torvald!

Ah, it’s glorious to feel that one has an assured

12position and ample means. Isn’t it delightful to

think of?

Oh, it’s wonderful!

Do you remember last Christmas? For three

whole weeks beforehand you shut yourself up

every evening till long past midnight to make

flowers for the Christmas-tree, and all sorts of

other marvels that were to have astonished us. I

was never so bored in my life.

I didn’t bore myself at all.

[Smiling.] But it came to little enough in the

end, Nora.

Oh, are you going to tease me about that again?

How could I help the cat getting in and pulling

it all to pieces?

To be sure you couldn’t, my poor little Nora.

You did your best to give us all pleasure, and

that’s the main point. But, all the same, it’s a

good thing the hard times are over.

Oh, isn’t it wonderful?

Now I needn’t sit here boring myself all alone;

and you needn’t tire your blessed eyes and your

delicate little fingers——

[Clapping her hands.] No, I needn’t, need I,

Torvald? Oh, how wonderful it is to think of!of!

[Takes his arm.] And now I’ll tell you how I

think we ought to manage, Torvald. As soon as

Christmas is over—-[The hall-door bell rings.]

Oh, there’s a ring! [Arranging the room.] That’s

somebody come to call. How tiresome!

I’m “not at home” to callers; remember that.

[In the doorway.] A lady to see you, ma’am.

Show her in.

[To Helmer.] And the doctor has just come,

sir.

Has he gone into my study?

Yes, sir.

[Helmer goes into his study. Ellen

ushers in Mrs. Linden, in travelling

costume, and goes out, closing the door.

[Embarrassed and hesitating.] How do you do,

Nora?

[Doubtfully.] How do you do?

I see you don’t recognise me.me.

No, I don’t think—oh yes!—I believe——[Suddenly

brightening.] What, Christina! Is it

really you?

Yes; really I!

Christina! And to think I didn’t know you!

But how could I——[More softly.] How

changed you are, Christina!

Yes, no doubt. In nine or ten years——

Is it really so long since we met? Yes, so it is.

Oh, the last eight years have been a happy time,

I can tell you. And now you have come to town?

All that long journey in mid-winter! How brave

of you!

I arrived by this morning’s steamer.

To have a merry Christmas, of course. Oh,

how delightful! Yes, we will have a merry

Christmas. Do take your things off. Aren’t you

frozen? [Helping her.] There; now we’ll sit

cosily by the fire. No, you take the arm-chair; I

shall sit in this rocking-chair. [Seizes her hands.]

Yes, now I can see the dear old face again. It

was only at the first glance——But you’re a

little paler, Christina—and perhaps a little thinner.

And much, much older, Nora.

Yes, perhaps a little older—not much—ever so

little. [She suddenly checks herself; seriously.] Oh,

what a thoughtless wretch I am! Here I sit

chattering on, and——Dear, dear Christina, can

you forgive me!

What do you mean, Nora?

[Softly.] Poor Christina! I forgot: you are a

widow.

Yes; my husband died three years ago.

I know, I know; I saw it in the papers. Oh,

believe me, Christina, I did mean to write to you;

but I kept putting it off, and something always

came in the way.

I can quite understand that, Nora dear.

No, Christina; it was horrid of me. Oh, you

poor darling! how much you must have gone

through!—And he left you nothing?

Nothing.

And no children?

None.

Nothing, nothing at all?

Not even a sorrow or a longing to dwell upon.

[Looking at her incredulously.] My dear Christina,

how is that possible?

[Smiling sadly and stroking her hair.] Oh, it

happens so sometimes, Nora.

So utterly alone! How dreadful that must be!

I have three of the loveliest children. I can’t show

them to you just now; they’re out with their

nurse. But now you must tell me everything.

No, no; I want you to tell me——

No, you must begin; I won’t be egotistical

to-day. To-day I’ll think only of you. Oh! but I

must tell you one thing—perhaps you’ve heard

of our great stroke of fortune?

No. What is it?

Only think! my husband has been made

manager of the Joint Stock Bank.

Your husband! Oh, how fortunate!

Yes; isn’t it? A lawyer’s position is so uncertain,

you see, especially when he won’t touch

any business that’s the least bit—shady, as of course

Torvald never would; and there I quite agree

with him. Oh! you can imagine how glad we

are. He is to enter on his new position at the

New Year, and then he’ll have a large salary, and

percentages. In future we shall be able to live

quite differently—just as we please, in fact. Oh,

Christina, I feel so lighthearted and happy! It’s

delightful to have lots of money, and no need to

worry about things, isn’t it?

Yes; at any rate it must be delightful to have

what you need.

No, not only what you need, but heaps of

money—heaps!

[Smiling.] Nora, Nora, haven’t you learnt

reason yet? In our schooldays you were a

shocking little spendthrift.

[Quietly smiling.] Yes; that’s what Torvald

says I am still. [Holding up her forefinger.] But

“Nora, Nora” is not so silly as you all think.

Oh! I haven’t had the chance to be much of a

spendthrift. We have both had to work.

You too?

Yes, light fancy work: crochet, and embroidery,

and things of that sort; [Carelessly] and other

work too. You know, of course, that Torvald left

the Government service when we were married.

He had little chance of promotion, and of course

he required to make more money. But in the first

year after our marriage he overworked himself

terribly. He had to undertake all sorts of extra

work, you know, and to slave early and late. He

couldn’t stand it, and fell dangerously ill. Then

the doctors declared he must go to the South.

You spent a whole year in Italy, didn’t you?

Yes, we did. It wasn’t easy to manage, I can

tell you. It was just after Ivar’s birth. But of

course we had to go. Oh, it was a wonderful,

delicious journey! And it saved Torvald’s life.

But it cost a frightful lot of money, Christina.

So I should think.

Twelve hundred dollars! Four thousand eight

hundred crowns![7] Isn’t that a lot of money?

How lucky you had the money to spend!

We got it from father, you must know.

Ah, I see. He died just about that time,

didn’t he?

Yes, Christina, just then. And only think! I

couldn’t go and nurse him! I was expecting little

Ivar’s birth daily; and then I had my poor sick

Torvald to attend to. Dear, kind old father! I

never saw him again, Christina. Oh! that’s the

hardest thing I have had to bear since my

marriage.

I know how fond you were of him. But then

you went to Italy?

Yes; you see, we had the money, and the

doctors said we must lose no time. We started a

month later.

And your husband came back completely cured.

Sound as a bell.

But—the doctor?

What do you mean?

I thought as I came in your servant announced

the doctor——

Oh, yes; Doctor Rank. But he doesn’t come

professionally. He is our best friend, and never

lets a day pass without looking in. No, Torvald

hasn’t had an hour’s illness since that time. And

the children are so healthy and well, and so am

I. [Jumps up and claps her hands.] Oh, Christina,

Christina, what a wonderful thing it is to live and

to be happy!—Oh, but it’s really too horrid of

me! Here am I talking about nothing but my

own concerns. [Seats herself upon a footstool close

to Christina, and lays her arms on her friend’s lap.]

Oh, don’t be angry with me! Now tell me, is it

really true that you didn’t love your husband?

What made you marry him, then?

My mother was still alive, you see, bedridden

and helpless; and then I had my two younger

brothers to think of. I didn’t think it would be

right for me to refuse him.

Perhaps it wouldn’t have been. I suppose he

was rich then?

Very well off, I believe. But his business was

uncertain. It fell to pieces at his death, and there

was nothing left.

And then——?

Then I had to fight my way by keeping a shop, a

little school, anything I could turn my hand to.

The last three years have been one long struggle

21for me. But now it is over, Nora. My poor

mother no longer needs me; she is at rest. And

the boys are in business, and can look after

themselves.

How free your life must feel!

No, Nora; only inexpressibly empty. No one

to live for! [Stands up restlessly.] That’s why I

could not bear to stay any longer in that out-of-the

way corner. Here it must be easier to find something

to take one up—to occupy one’s thoughts.

If I could only get some settled employment—some

office work.

But, Christina, that’s such drudgery, and you

look worn out already. It would be ever so much

better for you to go to some watering-place and

rest.

[Going to the window.] I have no father to give

me the money, Nora.

[Rising.] Oh, don’t be vexed with me.

[Going to her.] My dear Nora, don’t you be vexed

with me. The worst of a position like mine is

that it makes one so bitter. You have no one to

work for, yet you have to be always on the strain.

You must live; and so you become selfish. When

I heard of the happy change in your fortunes—can

you believe it?—I was glad for my own sake

more than for yours.

How do you mean? Ah, I see! You think

Torvald can perhaps do something for you.

Yes; I thought so.

And so he shall, Christina. Just you leave it all

to me. I shall lead up to it beautifully!—I shall

think of some delightful plan to put him in a good

humour! Oh, I should so love to help you.

How good of you, Nora, to stand by me so

warmly! Doubly good in you, who know so little

of the troubles and burdens of life.

I? I know so little of——?

[Smiling.] Oh, well—a little fancy-work, and

so forth.—You’re a child, Nora.

[Tosses her head and paces the room.] Oh, come,

you mustn’t be so patronising!

No?

You’re like the rest. You all think I’m fit for

nothing really serious——

Well, well——

You think I’ve had no troubles in this weary

world.

My dear Nora, you’ve just told me all your

troubles.

Pooh—those trifles! [Softly.] I haven’t told

you the great thing.

The great thing? What do you mean?

I know you look down upon me, Christina; but

you have no right to. You are proud of having

worked so hard and so long for your mother.

I am sure I don’t look down upon any one; but

it’s true I am both proud and glad when I remember

that I was able to keep my mother’s last days free

from care.

And you’re proud to think of what you have

done for your brothers, too.

Have I not the right to be?

Yes indeed. But now let me tell you,

Christina—I, too, have something to be proud

and glad of.

I don’t doubt it. But what do you mean?

Hush! Not so loud. Only think, if Torvald

were to hear! He mustn’t—not for worlds! No

one must know about it, Christina—no one but

you.

Why, what can it be?

Come over here. [Draws her down beside her on

the sofa.] Yes, Christina—I, too, have something

to be proud and glad of. I saved Torvald’s life.

Saved his life? How?

I told you about our going to Italy. Torvald

would have died but for that.

Well—and your father gave you the money.

[Smiling.] Yes, so Torvald and every one

believes; but——

But——?

Papa didn’t give us one penny. It was I that

found the money.

You? All that money?

Twelve hundred dollars. Four thousand eight

hundred crowns. What do you say to that?

My dear Nora, how did you manage it? Did

you win it in the lottery?

[Contemptuously] In the lottery? Pooh! Any

one could have done that!

Then wherever did you get it from?

[Hums and smiles mysteriously.] H’m; tra-la-la-la!

Of course you couldn’t borrow it.

No? Why not?

Why, a wife can’t borrow without her husband’s

consent.

[Tossing her head.] Oh! when the wife has

some idea of business, and knows how to set

about things——

But, Nora, I don’t understand——

Well, you needn’t. I never said I borrowed the

money. There are many ways I may have got it.

26[Throws herself back on the sofa.] I may have got it

from some admirer. When one is so—attractive

as I am——

You’re too silly, Nora.

Now I’m sure you’re dying of curiosity,

Christina——

Listen to me, Nora dear: haven’t you been a

little rash?

[Sitting upright again.] Is it rash to save one’s

husband’s life?

I think it was rash of you, without his knowledge——

But it would have been fatal for him to know!

Can’t you understand that? He wasn’t even to

suspect how ill he was. The doctors came to me

privately and told me his life was in danger—that

nothing could save him but a winter in the

South. Do you think I didn’t try diplomacy first?

I told him how I longed to have a trip abroad, like

other young wives; I wept and prayed; I said he

ought to think of my condition, and not to thwart

me; and then I hinted that he could borrow the

money. But then, Christina, he got almost angry.

He said I was frivolous, and that it was his duty

as a husband not to yield to my whims and fancies—so

he called them. Very well, thought I, but

saved you must be; and then I found the way to

do it.

And did your husband never learn from your

father that the money was not from him?

No; never. Papa died at that very time. I

meant to have told him all about it, and begged

him to say nothing. But he was so ill—unhappily,

it wasn’t necessary.

And you have never confessed to your husband?

Good heavens! What can you be thinking of?

Tell him, when he has such a loathing of debt!

And besides—how painful and humiliating it

would be for Torvald, with his manly self-respect,

to know that he owed anything to me! It would

utterly upset the relation between us; our

beautiful, happy home would never again be what

it is.

Will you never tell him?

[Thoughtfully, half-smiling.] Yes, some time

perhaps—many, many years hence, when I’m—not

so pretty. You mustn’t laugh at me! Of

course I mean when Torvald is not so much in

love with me as he is now; when it doesn’t amuse

him any longer to see me dancing about, and

dressing up and acting. Then it might be well

to have something in reserve. [Breaking off.]

Nonsense! nonsense! That time will never come.

Now, what do you say to my grand secret,

Christina? Am I fit for nothing now? You

28may believe it has cost me a lot of anxiety. It has

been no joke to meet my engagements punctually.

You must know, Christina, that in business there

are things called instalments, and quarterly

interest, that are terribly hard to provide for.

So I’ve had to pinch a little here and there,

wherever I could. I couldn’t save much out of

the housekeeping, for of course Torvald had to

live well. And I couldn’t let the children go

about badly dressed; all I got for them, I spent on

them, the blessed darlings!

Poor Nora! So it had to come out of your own

pocket-money.

Yes, of coursecourse. After all, the whole thing was

my doing. When Torvald gave me money for

clothes, and so on, I never spent more than half

of it; I always bought the simplest and cheapest

things. It’s a mercy that everything suits me so

well—Torvald never had any suspicions. But it

was often very hard, Christina dear. For it’s nice

to be beautifully dressed—now, isn’t it?

Indeed it is.

Well, and besides that, I made money in other

ways. Last winter I was so lucky—I got a heap

of copying to do. I shut myself up every evening

and wrote far into the night. Oh, sometimes I

was so tired, so tired. And yet it was splendid to

work in that way and earn money. I almost felt

as if I was a man.

Then how much have you been able to pay off?

Well, I can’t precisely say. It’s difficult to keep

that sort of business clear. I only know that I’ve

paid everything I could scrape together. Sometimes

I really didn’t know where to turn. [Smiles.]

Then I used to sit here and pretend that a rich

old gentleman was in love with me——

What! What gentleman?

Oh, nobody!—that he was dead now, and

that when his will was opened, there stood in

large letters: “Pay over at once everything of

which I die possessed to that charming person,

Mrs. Nora Helmer.”

But, my dear Nora—what gentleman do you

mean?

Oh dear, can’t you understand? There wasn’t

any old gentleman: it was only what I used to

dream and dream when I was at my wits’ end for

money. But it doesn’t matter now—the tiresome

old creature may stay where he is for me. I care

nothing for him or his will; for now my troubles

are over. [Springing up.] Oh, Christina, how

glorious it is to think of! Free from all anxiety!

Free, quite free. To be able to play and romp

about with the children; to have things tasteful

and pretty in the house, exactly as Torvald likes

30it! And then the spring will soon be here, with

the great blue sky. Perhaps then we shall have

a little holiday. Perhaps I shall see the sea

again. Oh, what a wonderful thing it is to live

and to be happy!

[The hall-door bell rings.

[Rising.] There’s a ring. Perhaps I had better

go.

No; do stay. No one will come here. It’s

sure to be some one for Torvald.

[In the doorway.] If you please, ma’am, there’s

a gentleman to speak to Mr. Helmer.

Who is the gentleman?

[In the doorway.] It is I, Mrs. Helmer.

[Mrs. Linden starts and turns away to the

window.

[Goes a step towards him, anxiously, speaking low.]

You? What is it? What do you want with my

husband?

Bank business—in a way. I hold a small post

in the Joint Stock Bank, and your husband is to

be our new chief, I hear.

Then it is——?

Only tiresome business, Mrs. Helmer; nothing

more.

Then will you please go to his study.

[Krogstad goes. She bows indifferently

while she closes the door into the hall.

Then she goes to the stove and looks to

the fire.

Nora—who was that man?

A Mr. Krogstad—a lawyer.

Then it was really he?

Do you know him?

I used to know him—many years ago. He was

in a lawyer’s office in our town.

Yes, so he was.

How he has changed!

I believe his marriage was unhappy.

And he is a widower now?

With a lot of children. There! Now it will

burn up.

[She closes the stove, and pushes the rocking-chair

a little aside.

His business is not of the most creditable, they

say?

Isn’t it? I daresay not. I don’t know. But

don’t let us think of business—it’s so tiresome.

Dr. Rank comes out of Helmer’s room.

[Still in the doorway.] No, no; I’m in your way.

I shall go and have a chat with your wife. [Shuts

the door and sees Mrs. Linden.] Oh, I beg your

pardon. I’m in the way here too.

No, not in the least. [Introduces them.] Doctor

Rank—Mrs. Linden.

Oh, indeed; I’ve often heard Mrs. Linden’s

name; I think I passed you on the stairs as I

came up.

Yes; I go so very slowly. Stairs try me so

much.

Ah—you are not very strong?

Only overworked.

Nothing more? Then no doubt you’ve come to

town to find rest in a round of dissipation?

I have come to look for employment.

Is that an approved remedy for overwork?

One must live, Doctor Rank.

Yes, that seems to be the general opinion.

Come, Doctor Rank—you want to live yourself.

To be sure I do. However wretched I may be,

I want to drag on as long as possible. All my

patients, too, have the same mania. And it’s the

same with people whose complaint is moral.

At this very moment Helmer is talking to just

such a moral incurable——

[Softly.] Ah!

Whom do you mean?

Oh, a fellow named Krogstad, a man you know

nothing about—corrupt to the very core of his

34character. But even he began by announcing, as

a matter of vast importance, that he must live.

Indeed? And what did he want with Torvald?

I haven’t an idea; I only gathered that it was

some bank business.

I didn’t know that Krog—that this Mr.

Krogstad had anything to do with the Bank?

Yes. He has got some sort of place there.

[To Mrs. Linden.] I don’t know whether, in your

part of the country, you have people who go

grubbing and sniffing around in search of moral

rottenness—and then, when they have found a

“case,” don’t rest till they have got their man into

some good position, where they can keep a watch

upon him. Men with a clean bill of health they

leave out in the cold.

Well, I suppose the—delicate characters require

most care.

[Shrugs his shoulders.] There we have it! It’s

that notion that makes society a hospital.

[Nora, deep in her own thoughts, breaks into

half-stifled laughter and claps her hands.

Why do you laugh at that? Have you any idea

what “society” is?

What do I care for your tiresome society? I

was laughing at something else—something excessively

amusing. Tell me, Doctor Rank, are all

the employees at the Bank dependent on Torvald

now?

Is that what strikes you as excessively amusing?

[Smiles and hums.] Never mind, never mind!

[Walks about the room.] Yes, it is funny to think

that we—that Torvald has such power over so

many people. [Takes the bag from her pocket.]

Doctor Rank, will you have a macaroon?

What!—macaroons! I thought they were

contraband here.

Yes; but Christina brought me these.

Mrs. Linden.

What! I——?

Oh, well! Don’t be frightened. You couldn’t

possibly know that Torvald had forbidden them.

The fact is, he’s afraid of me spoiling my teeth.

But, oh bother, just for once!—That’s for you,

Doctor Rank! [Puts a macaroon into his mouth.]

And you too, Christina. And I’ll have one while

we’re about it—only a tiny one, or at most two.

[Walks about again.] Oh dear, I am happy! There’s

only one thing in the world I really want.

Well; what’s that?

There’s something I should so like to say—in

Torvald’s hearing.

Then why don’t you say it?

Because I daren’t, it’s so ugly.

Ugly?Ugly?

In that case you’d better not. But to us you

might——What is it you would so like to say

in Helmer’s hearing?

I should so love to say “Damn it all!”[8]

Are you out of your mind?

Good gracious, Nora——!

Say it—there he is!

[Hides the macaroons.] Hush—sh—sh

Helmer comes out of his room, hat in hand,

with his overcoat on his arm.

[Going to him.] Well, Torvald dear, have you

got rid of him?

Yes; he has just gone.

Let me introduce you—this is Christina, who

has come to town——

Christina? Pardon me, I don’t know——

Mrs. Linden, Torvald dear—Christina Linden.

[To Mrs. Linden.] Indeed! A school-friend

of my wife’s, no doubt?

Yes; we knew each other as girls.

And only think! she has taken this long

journey on purpose to speak to you.

To speak to me!

Well, not quite——

You see, Christina is tremendously clever at

office-work, and she’s so anxious to work under a

38first-rate man of business in order to learn still

more——

[To Mrs. Linden.] Very sensible indeed.

And when she heard you were appointed

manager—it was telegraphed, you know—she

started off at once, and——Torvald, dear, for

my sake, you must do something for Christina.

Now can’t you?

It’s not impossible. I presume Mrs. Linden is

a widow?

Yes.

And you have already had some experience of

business?

A good deal.

Well, then, it’s very likely I may be able to

find a place for you.

[Clapping her hands.] There now! There now!

You have come at a fortunate moment, Mrs.

Linden.

Oh, how can I thank you——?

[Smiling.] There is no occasion. [Puts on his

overcoat.] But for the present you must excuse

me——

Wait; I am going with you.

[Fetches his fur coat from the hall and

warms it at the fire.

Don’t be long, Torvald dear.

Only an hour; not more.

Are you going too, Christina?

[Putting on her walking things.] Yes; I must set

about looking for lodgings.

Then perhaps we can go together?

[Helping her.] What a pity we haven’t a spare

room for you; but it’s impossible——

I shouldn’t think of troubling you. Good-bye,

dear Nora, and thank you for all your

kindness.

Good-bye for the present. Of course you’ll

come back this evening. And you, too, Doctor

40Rank. What! If you’re well enough? Of

course you’ll be well enough. Only wrap up

warmly. [They go out, talking, into the hall. Outside

on the stairs are heard children’s voices.] There

they are! There they are! [She runs to the outer

door and opens it. The nurse Anna, enters the hall

with the children.] Come in! Come in! [Stoops

down and kisses the children.] Oh, my sweet

darlings! Do you see them, Christina? Aren’t

they lovely?

Don’t let us stand here chattering in the

draught.

Come, Mrs. Linden; only mothers can stand

such a temperature.

[Dr. Rank, Helmer, and Mrs. Linden

go down the stairs; Anna enters the

room with the children; Nora also,

shutting the door.

How fresh and bright you look! And what

red cheeks you’ve got! Like apples and roses.

[The children chatter to her during what follows.]

Have you had great fun? That’s splendid! Oh,

really! You’ve been giving Emmy and Bob a

ride on your sledge!—both at once, only think!

Why, you’re quite a man, Ivar. Oh, give her to

me a little, Anna. My sweet little dolly! [Takes

the smallest from the nurse and dances with her.]

Yes, yes; mother will dance with Bob too.

What! Did you have a game of snowballs?

Oh, I wish I’d been there. No; leave them,

Anna; I’ll take their things off. Oh, yes, let

41me do it; it’s such fun. Go to the nursery;

you look frozen. You’ll find some hot coffee on

the stove.

[The Nurse goes into the room on the left.

Nora takes off the children’s things and

throws them down anywhere, while the

children talk all together.

Really! A big dog ran after you? But he didn’t

bite you? No; dogs don’t bite dear little dolly

children. Don’t peep into those parcels, Ivar.

What is it? Wouldn’t you like to know? Take

care—it’ll bite! What? Shall we have a game?

What shall we play at? Hide-and-seek? Yes,

let’s play hide-and-seek. Bob shall hide first.

Am I to? Yes, let me hide first.

[She and the children play, with laughter

and shouting, in the room and the

adjacent one to the right. At last Nora

hides under the table; the children come

rushing in, look for her, but cannot find

her, hear her half-choked laughter, rush

to the table, lift up the cover and see her.

Loud shouts. She creeps out, as though

to frighten them. Fresh shouts. Meanwhile

there has been a knock at the door

leading into the hall. No one has heard

it. Now the door is half opened and

Krogstad appears. He waits a little;

the game is renewed.

I beg your pardon, Mrs. Helmer——

[With a suppressed cry, turns round and half jumps

up.] Ah! What do you want?

Excuse me; the outer door was ajar—somebody

must have forgotten to shut it——

[Standing up.] My husband is not at home,

Mr. Krogstad.

I know it.

Then what do you want here?

To say a few words to you.

To me? [To the children, softly.] Go in to

Anna. What? No, the strange man won’t hurt

mamma. When he’s gone we’ll go on playing.

[She leads the children into the left-hand room, and

shuts the door behind them. Uneasy, in suspense.]

It is to me you wish to speak?

Yes, to you.

To-day? But it’s not the first yet——

No, to-day is Christmas Eve. It will depend

upon yourself whether you have a merry

Christmas.

What do you want? I’m not ready to-day——

Never mind that just now. I have come about

another matter. You have a minute to spare?

Oh, yes, I suppose so; although——

Good. I was sitting in the restaurant opposite,

and I saw your husband go down the street——

Well?

——with a lady

What then?

May I ask if the lady was a Mrs. Linden?

Yes.

Who has just come to town?

Yes. To-day.

I believe she is an intimate friend of yours?

Certainly. But I don’t understand——

I used to know her too.

I know you did.

Ah! You know all about it. I thought as

much. Now, frankly, is Mrs. Linden to have a

place in the Bank?

How dare you catechise me in this way, Mr. Krogstad—you,

a subordinate of my husband’s?

But since you ask, you shall know. Yes, Mrs. Linden

is to be employed. And it is I who

recommended her, Mr. Krogstad. Now you

know.

Then my guess was right.

[Walking up and down.] You see one has a wee

bit of influence, after all. It doesn’t follow

because one’s only a woman——When people

are in a subordinate position, Mr. Krogstad, they

ought really to be careful how they offend anybody

who—h’m——

——who has influence?

Exactly.

[Taking another tone.] Mrs. Helmer, will you

have the kindness to employ your influence on my

behalf?

What? How do you mean?

Will you be so good as to see that I retain my

subordinate position in the Bank?

What do you mean? Who wants to take it

from you?

Oh, you needn’t pretend ignorance. I can very

well understand that it cannot be pleasant for

your friend to meet me; and I can also understand

now for whose sake I am to be hounded

out.

But I assure you——

Come come now, once for all: there is time

yet, and I advise you to use your influence to

prevent it.

But, Mr. Krogstad, I have no influence—absolutely

none.

None? I thought you said a moment ago——

Of course not in that sense. I! How can you

imagine that I should have any such influence

over my husband?

Oh, I know your husband from our college

days. I don’t think he is any more inflexible than

other husbands.

If you talk disrespectfully of my husband, I