This index treats exclusively of the pages in this volume containing legends and exposition

of legends, pages 1–253. Its purpose is: first, to correlate certain facts in respect

to legendary features, as will be seen, for instance, in the headings beginning with

“Treasure”; secondly, to give geographic names connected with the legends; thirdly,

to list the names of informants and contributors of legends as well as of authors

and publications referred to in the legends. The index is not intended to supplant

the table of contents provided at the beginning of the volume.

Adams, Ephraim Douglass, British Diplomatic Correspondence Concerning the Republic of Texas, .

Adkins, “Uncle” Ben, .

Agreda, Maria de Jesus de, , .

Aguayo Expedition, , .

Aijados, The Seven Hills of, .

Aimard, Gustave, The Freebooters, ., .

Ainsworth, Roy, .

Alamo, , , , .

Allston, Theodosia Burr, –.

Alpine, .

Amazons, mythical wealth of, .

Andamarca, .

Antonette’s Leap, ff.

Apaches, , , .

Arapahoes, , .

Arbuckle Mountains, .

Arizona, , .

Atahualpa, .

Atascosa County, .

Aury, Luis de, , .

Austin, , , , , .

Austin, Stephen F., , , , , , .

Aztec(s), , , , .

Babb, Stanley E., .

Baffle Point, .

Baker, D. W. C, Texas Scrap Book, .

Balboa, .

Bancroft, H. H., .; History of the North Mexican States and Texas, ., .

Bandelier, Adolphe F., The Gilded Man, ., ., ., .

Bandera County, .

Bandera Pass, .

Barber, J., “The White Steed of the Prairies,” .

Barker, E. C., , .; Barker, Potts, and Ramsdell, A School History of Texas, .

Barnes, Charles Merritt, Combats and Conquests of Immortal Heroes, .

Bass, Sam, ff.

Bay Ridge, .

Beaumont, .

Beaver, Tony, mythical strong man of West Virginia, .

Beazley, Julia, .

Beeville, .

Bell County, , .

Belton, , .

Benalcazar, Sebastian de, .

Benavides, Fray Alonso de, Memorial, , , .

Benditas Animas, Arroyo de las, .

Bertillion, L. D., , , , .

Big Bend, , –, ff., .

Binkley, William Campbell, “The Last Stage of Texan Military Operations Against Mexico,

3,” .

“Black Stephen,” .

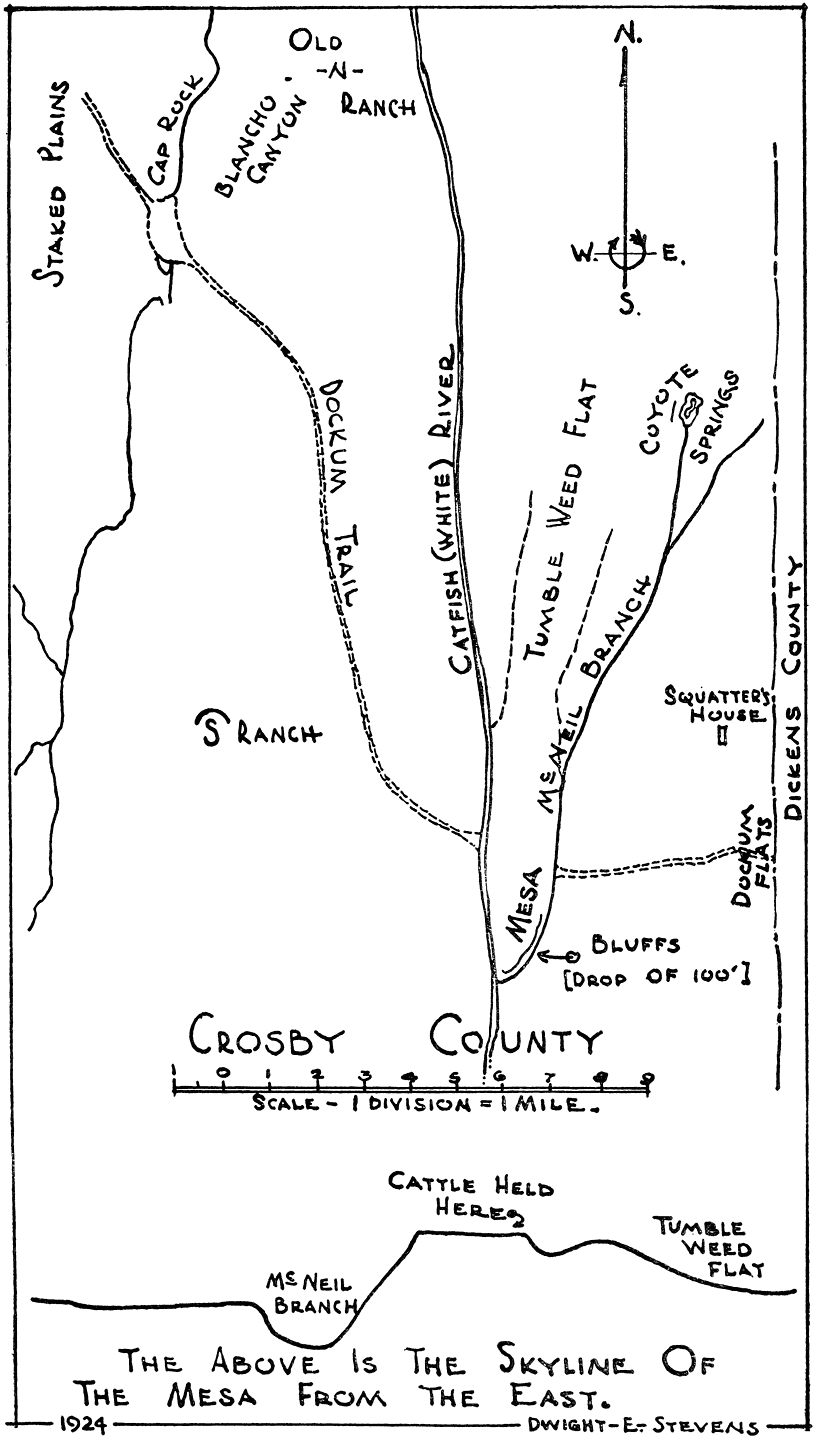

Blanco Canyon, .

Blanco River, , .

Blue Bonnet, ff.

Blue Lady. See “Mysterious Woman in Blue,” in table of contents.

Bogota, .

Bolivar peninsula, .

Bolton, H. E., Athanase de Mézières, ., ., .;

Spanish Explorations in the Southwest, ., ., .;

“The Spanish Occupation of Texas,” ., .;

Texas in the Middle Eighteenth Century, ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., .;

“The Founding of the Missions on the San Gabriel River, 5–1749,” .

Bonner, J. S. (K. Lamity), The Three Adventurers, .

Boone’s Ferry, , , .

Bosque, Genardo del, .

Bowie, James, , ff., .

Bowie, John, .

Bowie, Rezin P., , , , .

[272]

Bowie Mine, ., ff., , –, , , .

Bradley, Matt, Border Wars of Texas, .

Brazoria County, , , , , .

Brazos River, , , , , , , –, , ff., –.

Brewster County, ., , , , .

Brown, John Henry, History of Texas, ., ., , ., .

Brown, Josephine, .

Buckley, Eleanor Claire, “The Aguayo Expedition into Texas and Louisiana,” ., .

Buckner’s Creek, , , .

Bugess Lake, .

Bunyan, Paul, mythical strong man of lumber camps, .

Burall, Poncho, .

Burleson, General, , , , , , .

Burns City, .

Burton, the elder, .

Burton, West, , , , .

Caldwell County, .

California, , , .

Callan, Austin, .

Callihan, W. C., .

Cameron County, , .

Campbell’s Bayou, .

Campeachy, .

Canadian River, , .

Caney River, , .

Cannon. See Treasure.

Carancaguas, .

Carothers, Mrs. H. W., .

Carrizo Springs, .

Casa Blanca, , , , , –, .

Casa del Santa Anna. See Santa Anna.

Casa del Sol, .

Casas Grandes, .

Casis, Lilia M., “Letter of Fray Damian Manzanet,” etc., .

Catfish, or Blanco, River, .

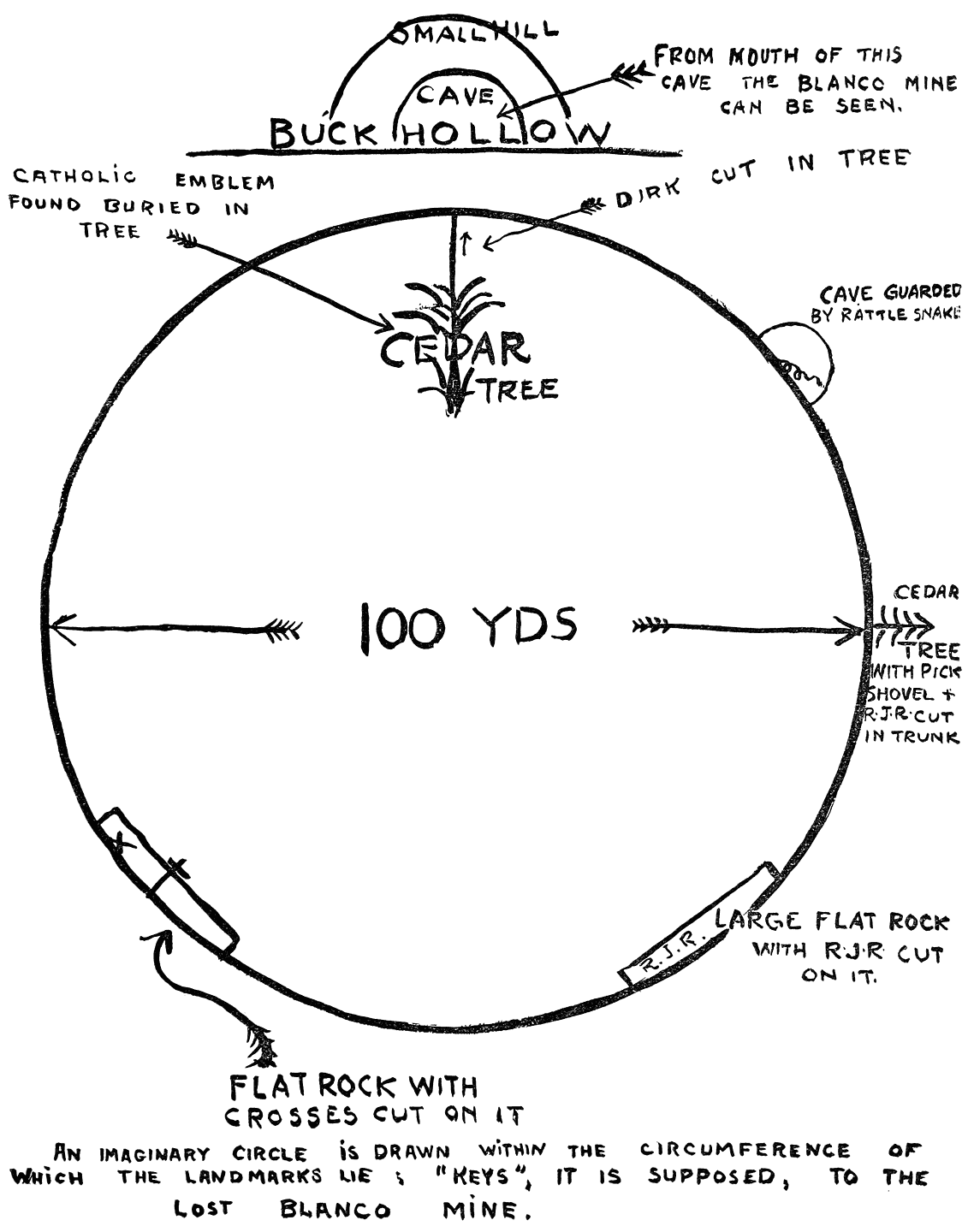

Cave(s), , ff. See also under Treasure.

Cheetwah, –.

Cerro de la Plata, , .

Chapman, Charles E., The Founding of Spanish California, .

Charts. See Treasure, location of indicated by.

Cherokees, , .

Cheyennes, , .

Chisos Mountains, .

Chocolate Bayou, , .

Chuzas, Mountains, Las, , , .

Cibola, Seven Cities of, , , .

Ciudad Encantada de los Cesares, La, .

Clark, A., Jr., “Legend of the Great River,” .

Clear Fork Creek, near Lockhart, .

Coleman County, .

Colombia. See El Dorado.

Colonists of Texas, The first American, , , , .

Colorado, mine hunters go to, .

Colorado, Texas, alleged Spanish fort at, .

Colorado River, , , , , , , , , , , , , –, , .

Columbia, Texas, .

Comanche(s), , ., , , , –, , , , .

Concan, .

Concho River, .

Conquistadores, , .

Cook, Lorene, .

Cooke County, , , .

Coronado’s Expedition, , , , .

Corpus Christi, , , .

Cortez, , , .

Coryell County, .

Cox Bay, ;

Cox Creek, .

Craddock, John R., , , .

Crosby County, .

Croton Creek, .

Cubanacan, Palace of, in Cuba, .

Cundinamarca, .

Custer, General, .

Cuzco, .

Dallas News, .

Dallas Semi-Weekly Farm News, .

Dallas Times Herald, .

Darden, Mrs. F., .

Darter, W. A., .

Davis, Mollie E. Moore, Under the Man-Fig, , .

Davis Mountains, , .

Dead Horse Canyon, .

Death Bell, The, .

Deep Eddy, .

Del Rio, , .

Democratic Review, The, .

Denison, .

Devil, fight of, with Strap Buckner, –.

Devil’s River, .

Devil’s Water Hole, .

Dewees, W. B., Letters from an Early Settler of Texas, .

Dexter, , .

Dienst, Alex., , .

Dimmit County, .

Dobie, Bertha McKee, , , .

Dobie, J. Frank, , , , , , , , , , , , , .

[273]

Dockum Flats, .

Double Mountain Fork of the Brazos, , .

Dryden, Texas, .

Dubose, E. M., , , , .

Duffy, Judge Hugh, .

Dunn, W. E., .;

“The Apache Mission of the San Sabá River,” ., .;

“Missionary Activities among the Eastern Apaches Previous to the Founding of the San

Sabá Mission,” .

Dyer, J. O., The Early History of Galveston, ., .

Eagle Lake, –.

Eagle Lake Headlight, .

Eagle Springs, .

East Bay, .

East Texas, , .

Eckert, Flora, .

Eddins, A. W., , .

Edward, David B., History of Texas, .

Edwards, Hayden, .

El Dorado, , , , , , . See Bandelier, The Gilded Man.

El Paso, , , , , .

Ellis, Frank, .

Enchanted Rock, –.

Espada, mission of, .

Estill, Julia, , .

Falls County, .

Fannin, .

Farmer, Grenade, .

Flint Creek, .

Flores, Manuel, .

Fort, Old Spanish, near Ringgold, , .

Fort Bend, .

Fort Brown, .

Fort Davis, .

Fort Ewell, , .

Fort Lancaster, .

Fort Merrill, , .

Fort Planticlan, , .

Fort Ramirez, , –.

Fort Stockton, , , , .

Fort Worth, .

Fortin, El, .

Fournel, Henri, Coup d’ oeil … sur le Texas, .

Fredericksburg, .

Freeport, .

Freeport Facts, , .

Frio County, .

Frio River, , , , –.

Frontier Times, ., ., .

Fulmore, Z. T., History and Geography of Texas as Told in County Names, .

Gainesville, , .

Galveston, , , 211 n., , .

Galveston Bay, –, .

Galveston News, , , ., , , , , , .

Galveston Island, , , , .

Galveston Weekly Journal, ., .

Gambrell, Tom, .

Garrison, George P., Texas, .

Gay, J. Leeper, , .

Gillespie County, .

Girardeau, Claude M., “The Arms of God,” .

Goddard, Pliny Earle, .

Goliad, , .

Gran Moxo, .

Gran Paytiti, .

Gran Quivira, , , .

Grayson County, .

Gregg, Josiah, Commerce of the Prairies, .

Grey, Zane, The Last of the Plainsmen, ., .

Grolier Society, The Book of Knowledge, .

Guadalupe Mountains, –, .

Guadalupe River, .

Gulf of Mexico, 142, , , .

Gulf Messenger, The, .

Gunter, Lillian, .

Gumman Gro, .

Hamilton’s Valley, .

Hardeman County, .

Hardy, Mrs. Jack, .

Harris County, .

Haskell County, .

Hatcher, Mrs. Mattie Austin, , ., , .

Hays, Jack, ., .

Heimsath, Charles H., .

Henderson County, .

Higgins, W., .

Hodge, F. W., ., , .

Honey Creek, shaft of mine opened by Miranda on, , .

Hörmann, Father, Die Tochter Tehuans, .

Hornaday, W. D., “Lost Gold Mines of Texas,” etc., .

Horns, superstitions concerning, –.

Horn worshipers, ff.

Hough, Emerson, North of , .

Houston, General, .

Houston Chronicle, ., .

Houston Morning Star, .

Houston Post, .

Hudgins, Charles D., The Maid of San Jacinto, .

Hunnington, Colonel, –.

Hunter, J. Marvin, ;

Pioneer History of Bandera County, .

[274]

Hunter, John Warren, “The Hunt for the Bowie Mine in Menard,” .;

A Brief History of the Bowie or Almagres Mine, , , , –;

“The Schnively Expedition,” .

Hunter’s Frontier Magazine, , .

Hyacinth, origin of, .

Iguanas, La Mina de Las. See Bowie Mine.

Incas, .

Indian(s) as actors in legends of Texas, , –, , , , , , , , , , , , , , –, –, –, –, –, , , , –, –, –, –, –, –, –, –, , –, , –, –, , , –, –.

Indian(s) as transmitters of legends of Texas, , , , , , .

Indian Bluff, .

Indian influence on Spanish treasure seekers, , , , .

Indianola, .

Irving, Washington, , .

Jackson County, .

James, Jesse, .

Janvier, Thomas A., Legends of the City of Mexico, .

Jacques, Mary J., Texan Ranch Life, .

Jim Wells County, .

Jourdanton, .

Jumano Indians, . See Xumanos.

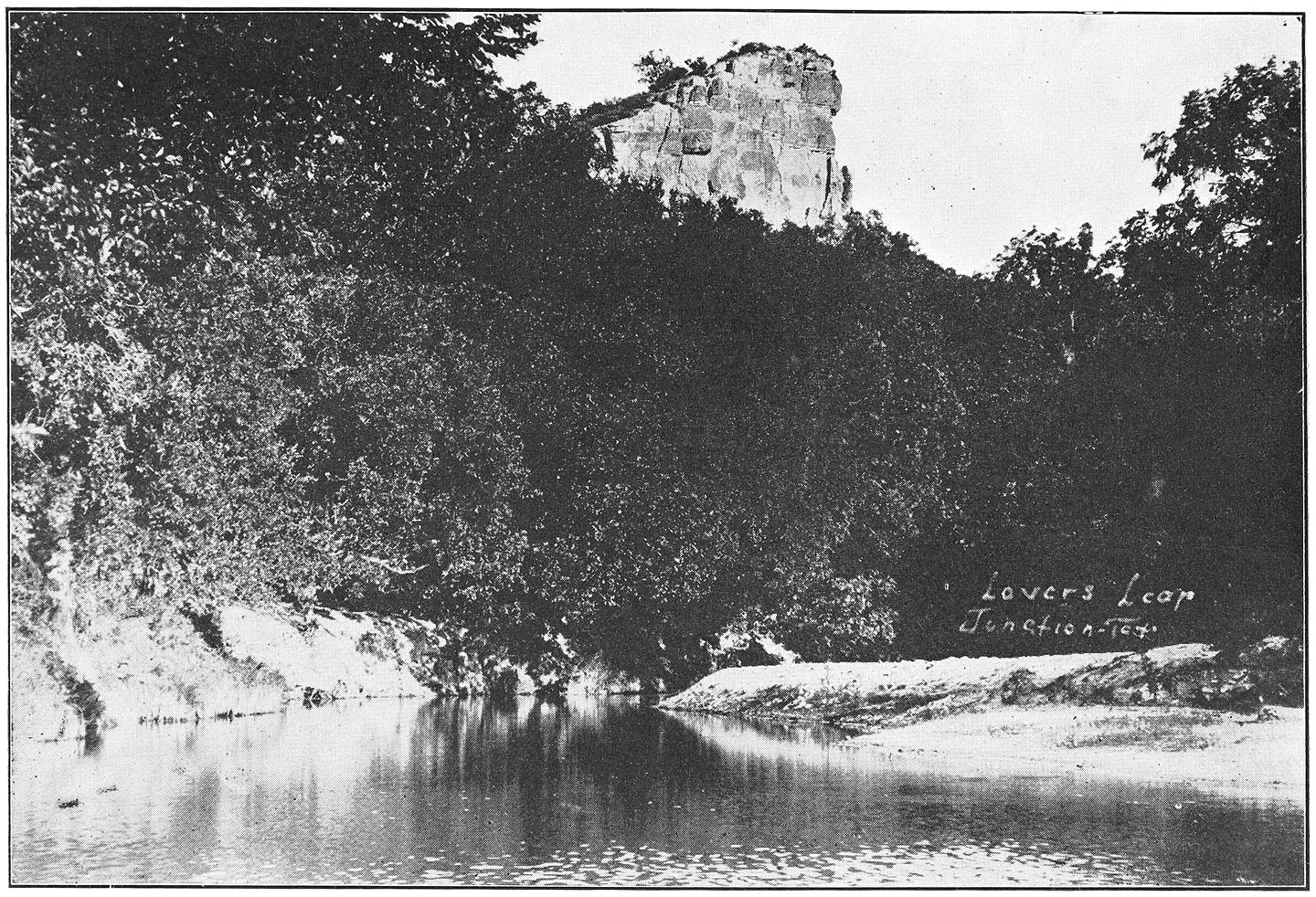

Junction, ff.

Kendall, George Wilkins, Narrative of the Texan Santa Fe Expedition, .

Kennedy, William Esquire, Texas, etc., .

Kenney, of McMullen County, .

Kenney, M. M., cited, –, .

Kidd, Captain, .

Kimble County, , .

Kincaid, Edgar, , .

Kincaid, J. M., .

King County, .

Kingsland, .

Kiowa Peak, , .

Knox, J. Armory. See Sweet, Alex E.

Kress, Mrs. Margaret Kenney, .

Lafitte, Jean, ff.

Lagarto, , .

La Grange, , .

Laguna de Oro, .

Lamb, Biographical Dictionary of the United States, .

Lampasas River, .

La Nana Creek, , .

Landa, Louis, .

Lane, Edith C., .

Langerock, Hubert, “Paul Bunyan,” .

Lanier, Sidney, “The Revenge of Hamish,” .

La Porte, .

Laredo, , .

Laredo Crossing, , , , .

La Salle, , .

La Salle County, , .

Las Amarillas. See Bowie Mine.

Las Animas, purported fort, .

Lavaca County, .

Lavaca River, , .

Leakey, .

Leon County, .

Leon River, .

Letts, F. D., .

Lewis, John, .

Lily, water, –.

Lipans, ., –, –.

Littlejohn, E. G., , , , .

Little River, .

Live Oak County, , , , .

Liverpool, , .

Llano County, , .

Llano hills, bullion and mines in, , –, –, –.

Llano River, , , –, , , –, , .

Llano Valley, .

Lockhart, , , .

Loma Alta, .

Loma de Siete Piedras, –.

Looscan, Adele B., .

Los Almagres, , , –, , .

See Bowie Mine.

Lost “Bad Lands,” .

Lost Canyon, ff.

Lost gold, brook of, ;

hole of, –.

See Mines, lost.

Lost mines. See Mines.

Lost Mountains, .

Lost plateau, .

Louisiana, , , , –.

Lovers, in legend, ff.

Lover’s (Lovers’) Leap, Waco, ;

Denison, ;

Kimble County, –;

Santa Anna, –;

Mount Bonnell, –.

Lover’s (Lovers’) Retreat, –.

Lubbock, Francis Richard, Six Decades in Texas, .

Lummis, Chas. F., The Enchanted Burro, ., .

Maddrey, Etta, .

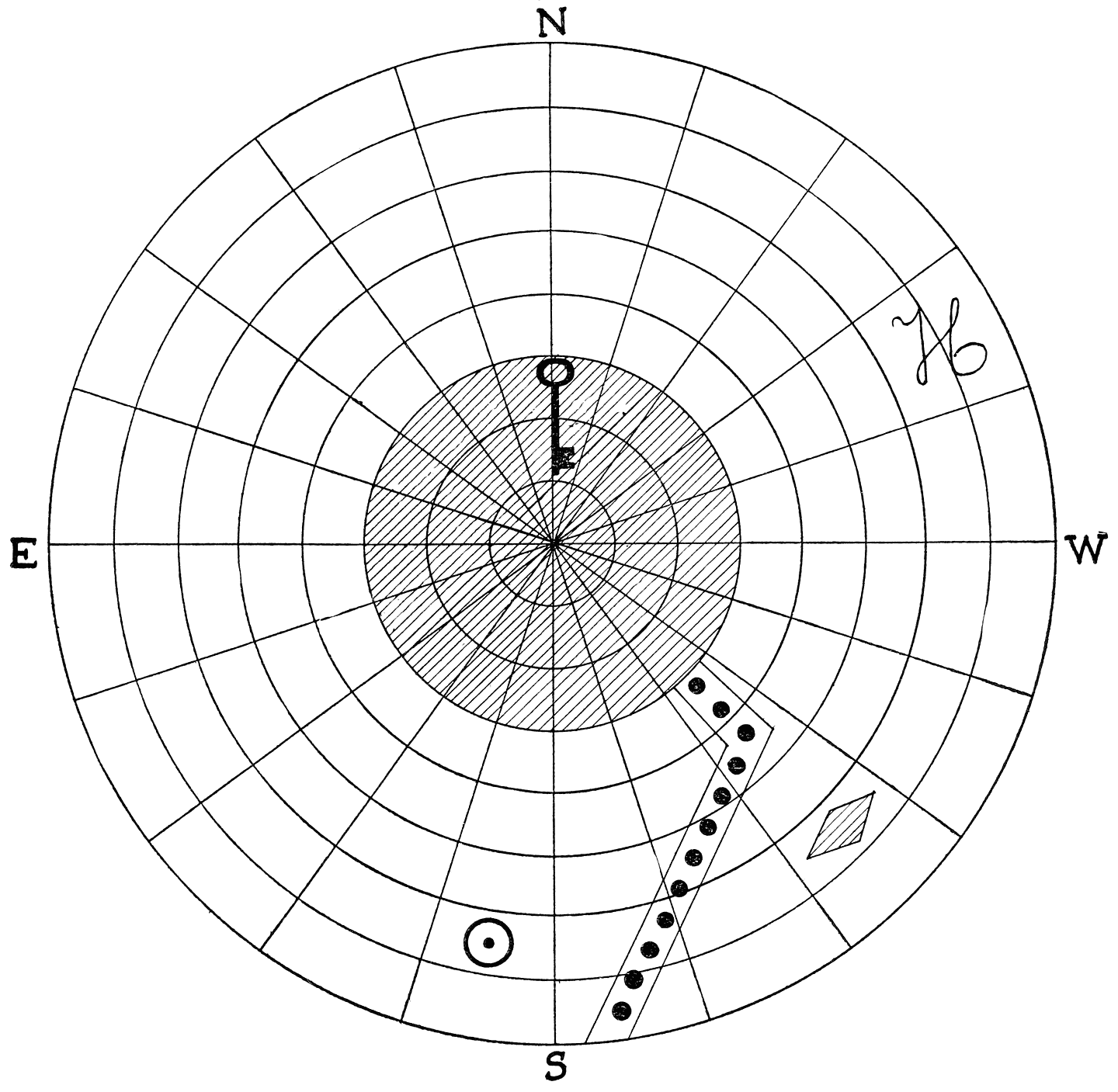

Magic Circle, The, –.

Maletas. See Treasure.

Maravillas Canyon, .

[275]

Margil, Father, –.

Marryat, Captain, Narrative of the Travels, etc., ., ., .

Martin, Roscoe, .

Mason, Texas, .

Matagorda County, .

Matagorda Peninsula, .

McConnell, H. H., Five Years a Cavalryman, .

McCulloch County, .

McDaniel, H. F., his part in The Coming Empire or Two Thousand Miles in Texas on Horseback, –.

McKinney Examiner, .

McLean, Judge W. P., , .

McMullen County, , –, , .

McNeil Branch, .

McNeill, cave at, .

Medicine Mounds, –.

Memphis Enquirer, .

Menard, mission and presidio near, , , , , .

Mescalero Apache(s), , , .

Metheglin Creek, Bell County, .

Mexicans, a source of stories of buried treasure and lost mines in Texas, , , , , –, , –, , , –, , , , , , –, –, –, , , –, , –, –, , , , .

Mexican(s) as source of other than buried treasure legends, , , .

Mexican War, , , .

Mexico, , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , ff., , .

Mexico, City of, , , .

Milam County, , –.

Mine(s) lost:

Los Almagres or Bowie, , ., –, , –, , , ;

“Nigger Gold Mine,” , –, ;

gold in Guadalupe Mountains, sometimes known as “Lost Sublett Mine,” –;

near Corpus Christi, perhaps the Casa Blanca, , , ;

coal, on upper Trinity, ;

gold, on Little Llano, ;

silver and lead, Packsaddle Mountain, –;

silver, Las Chuzas, –,

near Casa Blanca, ;

silver and lead near head of Frio, –;

quicksilver, Sabinal, –;

lead, Sabinal, ;

“Lost Cabin,” ;

copper, in Haskell County, , ;

lead, on Salt Fork of Brazos, , –;

gold, near Enchanted Rock, .

Mines, lost, indicated by: rust-eaten pick, , ;

furnace, ;

marked tree, ;

“Magic Circle,” –;

burnt rocks, ;

way-bill, ;

rainbow path, .

Mineral or gold rod, , , , .

Minter, Billy, .

Miranda, Bernardo de, reports of on the San Saba mines, –.

“Miranda’s Expedition to Los Almagres and Plans for Developing the Mines,” .

“Monkey,” gold. See Mineral rod.

Monroe, Marshall, “The Mission de Los Olmos,” .

Montague, Margaret Prescott, “Up Eel River,” .

Montague County, , , .

Monterrey, , , .

Montezuma, , ;

capital of, ;

cave of, , –.

Moors in Spain, treasure legends among, .

Moro, in legend of treasure, ff.

Morris, J. W., , .

Morphis, J. M., History of Texas, .

Mount Bonnell, ff.

Mount Franklin, .

Muiscas, .

Murphy, John, , .

Music, mysterious, ff; ff.

Music Bend, in San Bernard River, –.

Nacogdoches, , , , , , , , .

Narcissus, .

Navidad River, , ff.

Naylor, Dick, “The Llano Treasure Cave,” .

Neches River, , –, .

Negro element in Texan folk-tales, , –, –, –, , , , , , ff.

New International Encyclopedia, The, .

New Mexico, , , , , , , , , , .

New Orleans, , , , .

New Orleans Picayune, ., .

New York Mirror, .

New York World, .

Nigger Gold Mine, , –.

Nolan River, .

Northwest Texas, .

Notley, W. D., .

Nueces County, , .

Nueces Canyon, , .

Nueces River, , , , , , , , , , .

Nuestra Señora de la Luz, .

Nutt, Bob, , .

Obregon, Don Ignacio, .

Odessa, .

Oklahoma, , , , .

Oklahoma Historical Society, Chronicles of Oklahoma, .

[276]

Orcoquiza, tribe of Indians, .

O’Reilly, Edward, .

O’Reilly, Tex., .

Packsaddle Mountain, , , .

Page, Sidney, “Mineral Resources of the Llano-Burnet Region,” .

Palo Alto, .

Palo Pinto, , .

Palo Pinto County, , .

Panhandle, , .

Parker, Mrs. Laura Bryan, .

Payne, L. D., Jr., , , , .

“Peak of Gold,” .

Pecos Bill, mythical strong man in Southwest, .

Pecos River, , , .

Peña Creek, .

Pendleton, George C., .

Peru, .

Petronita, .

Philadelphia Times, .

Pizarro, , .

Platas. See Treasure, buried, location of indicated by.

Pleasanton, .

Poetry Society of Texas, A Book of the Year, .

Point Isabel, .

Point Sesenta, .

Polly’s Peak, , .

Port Neches, .

Potosi, silver mines of, , .

Prairie-Lea Lockhart road, .

Prescott, Conquest of Mexico, .;

Conquest of Peru, .

Priestley, H. I., José de Galvez, .

Pueblos del Rey Coronado, .

Quanah, .

Quesada, , .

Quintana, .

Raht, Carl, The Romance of Davis Mountains, ., .

Ramireña Creek, , –.

Ranger(s), Texas, –, , , , , , , , , –, .

Ratchford, Fannie, , .

Reagan Canyon, .

Realitos, .

Red River, , , , , , , .

Reed’s Lake, .

Refugio, , , .

Reid, Mrs. Bruce, .

Reid, Samuel C., Jr., The Scouting Expedition of McCulloch’s Texas Rangers, .

Republic of Fredonia, .

Resaca de la Palma, , .

Richmond Telescope, .

Rio Grande, , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , ., , , .

Ripas, –.

Roberts, Captain Dan W., Rangers and Sovereignty, .

Robertson, George L., .

Rock Crossing on the Nueces, , .

Rockdale, .

Rock Pens, The, –, , , .

Rogers, Bell County, .

Roma, , .

Rose, Cherokee, legend of, .

Rose, Victor M., Some Historical Facts in Regard to the Settlement of Victoria, Texas, ., .

Round Rock, , .

Round Top Mountain, .

Russell Hills, , .

Sabinal, , , , .

Sabinal River, .

Saint Louis, , , , .

Salt Fork of the Brazos, , , .

San Antonio, Texas, expedition to from Coahuila, ;

chart business in, ;

Bowie’s enterprises from, , –;

Mexican Army’s movements around, , ;

treasure buried by Mexicans going to, , , , , , , , , , .

San Antonio Express, ., ., , .

San Antonio-Laredo Road, , .

San Antonio River, , .

San Augustine, .

San Bernard River, , , , , .

San Caja Mountain, , , –, , , .

San Gabriel, town of, .

San Gabriel Mission, , , –.

San Gabriel River, , , .

San Jacinto, buried treasure legends around, ;

Mexican treasure taken at battle of, ;

retreat from, , .

San Jacinto Bay, .

San José, Mission, , .

San Juan, Mission of, , .

San Luis Pass, .

San Marcos, .

San Marcos River, –, .

San Pedro Springs, .

San Saba, mission and presidio of, , ., , , , , ., .

San Saba Mines, –, .

See Bowie, also Mines, Lost.

San Saba River, , , , , , ., , .

Sanderson, , .

“Sands,” The, , .

Sandy, The, Lavaca County, ;

Llano County, .

[277]

Santa Anna, Mexican General, , , , , , , .

Santa Anna, Texas, .

Santa Anna Mountains, –, .

Santana, .

Santa Fe, .

Santa Fe Expedition, .

Santiago, .

Schmitt, Edmond J. P., cited, .

Seaview Bend, .

Shannon, Mrs. A. F., , , .

Shea, John Gilmary, The Catholic Church in Colonial Days, .

Sherrill, R. E., .

Shipman, Daniel, Frontier Life, .

Sioux, , .

Sjolander, John P., .

Skaggs, N. R., .

Skinner, Charles M., Myths and Legends of Our New Possessions, .;

Myths and Legends of Our Own Land, ., .

Smith, Buckingham, Documentos para la historia de la Florida, .

Smith, John, .

Smith, R. R., .

Smith, Victor, .

Smithwick, Noah, The Evolution of a State, .

Snively (Schnively), Colonel Jacob, , –.

See also .

Snyder, Captain, .

Sonora Mountains, .

“South Sea,” .

Southey, Robert, “The Inchcape Rock,” .

Southwest, influence of Spanish upon Americans of, , , ;

overthrow of Spanish by Indians of, ;

how the blue bonnet came to, .

Southwest Texas, , , , .

Southwestern Historical Quarterly, ., ., ., , .

See also Texas State Historical Association Quarterly.

Sowell, A. J., Early Settlers and Indian Fighters of Texas, .

Spanish, , , , ;

influence of on imaginations of Texas pioneers, ;

treasure and mines in Texas attributed to, –, , , , –, , , –, , –, –, , –.

Spence, Lewis, Myths and Legends, .

Spillane, James, .

Spratt, Dr. J. F., .

Spratt, J. S., .

Squatter, The Headless, –.

Stallion, The Pacing White, ff.

Stampede Mesa, –.

Sterling, Captain William, .

Staples, Pete, , –.

Stevens, Walter B., Through Texas, .

Stoddard, William O., The Lost Gold of the Montezumas, A Story of the Alamo, .

Stonewall County, .

Sturmberg, Robert, History of San Antonio and the Early Days of Texas, ., .

Sublett, “Old Ben,” his mine, –.

Sugar Loaf, mound, .

Supernatural appearances and occurrences;

dragon, ;

ghostly sounds, , ;

ghostly lights, , , –, –;

ghostly goat, ;

phantom trees, , ;

skeleton of supernatural height and powers, ;

ghost dog, , ;

bull as guardian of treasure, ;

La Vaca de Lumbre, .;

goblin, .;

gate that would not shut, ;

ghosts of murdered men, , , , ;

phantom steers, , ;

“Woman of the Western Star,” –;

appearances of the devil in his own form, in form of bull, in form of wild cat, , –, , –;

the face of Cheetwah on Mount Franklin, ;

appearances of Maria de Jesus de Agreda, –;

phantom music, –, –;

phantoms appearing near Music Bend in the San Bernard River –;

phantom woman of salt marshes, ;

“Padre’s beacons,” ;

fulfillment of a curse, , ;

supernatural dying of trees, ;

ghost of boatman and his boat, –;

phantom warriors, ;

phantom lover, –, , .;

phantom horror of the Neches, –;

ghost of Lafitte, –;

white wigwam of the Great Spirit, ;

origin of the blue bonnet, ff.;

transformation of maiden into water lily, ;

miraculous origin of stream or spring, –, –;

ringing of bells without hands, ;

supernatural destruction, , –, ;

miraculous preservation, ;

magic wand, ;

ghostly footprints, .

Supernatural strength:

of Paul Bunyan, ;

of Tony Beaver, ;

of Pecos Bill, ;

of Strap Buckner, , –;

of the White Steed of the Prairies, –.

Sutherland, Mary A., The Story of Corpus Christi, ., ., , .

Swan Lake, .

[278]

Sweet, Alex. E., and Knox, J. Armory, On A Mexican Mustang Through Texas, .

Swisher, Bella French, .

Taovayas, .

Tawaponies, –.

Taylor, N. A., .

Taylor, Mrs. V. M., .

Tejas, , .

Temple, .

Terrell County, .

Terreros, Don Pedro, .

Texas Magazine, The, ., , .

Texas pioneers, influence of Spanish genius upon, , , .

Texas Pioneer Magazine, ., .

Texas State Historical Association Quarterly, ., ., ., ., ., .

See also Southwestern Historical Quarterly.

Tezcuco, lake of, Spanish treasure lost in, .

Thoburn, Joseph B., .

Thomas, Mrs. W. H., .

Thomas, Wright, , .

Thorndale, , , .

Thrall, H. S., A History of Texas, ., .

Three Forks, , .

Tilden, , , .

Townsend, E. E., .

Treasure:

maleta(s) filled with, , , ;

cannon(s) stuffed with, , –;

cave(s) stored with, , , , , , , –;

chest(s) of, , , , , , , ., ;

cowhides of, ;

sacks of, ;

vault of, –;

dugouts of, ;

jackloads of, , , , , –, , , –;

mule loads of, , ;

wagon loads of, , , ;

cart loads of, , , .

Treasure, concealed by:

Texas bandits, , ;

Mexican army, detachment of, , , , , , –;

Mexican bandits, , , , , ;

Mexican adventurers, , , , ;

Mexican wagon train, ;

ranchmen or sheepmen, , , ;

Spaniards, , , , , , , , , ;

“three men,” ;

Steinheimer, –;

murderer, ;

Indians, , , ;

pirates, ff.

Treasure, buried, dreams connected with, –, –, –.

Treasure, buried, that has been found, , , , , , , , , , , , , , .

Treasure, buried, guarded by:

dragon, ;

rattlesnakes, ;

white panther, ;

white lion, ;

ghost of murdered man, , , ;

dog, , –;

spirits, , ;

bull, ;

giant skeleton, ;

horror, .

Treasure, buried, location of indicated by:

chart(s), , , , , , ;

way-bill, –, ;

plata, , , ;

fortune teller, , –, ;

mineral, or “gold,” rod, , ;

lights, , , –, –;

white object, , ;

“plat rock,” ;

map, , , ;

medium, ;

Lafitte’s ghost, –;

parchment, .

See also, Mines, lost.

Treasure, buried, marked by:

rock or rocks, , , , , , ;

rock pens, –, ;

knolls or knobs, , , ;

chain, –;

tree or trees, , , , , , , , , , ;

animals drawn on trees and stones, ;

line of hills, .

Treasure, buried, superstitions connected with, , , , , , , , –, –, –.

Treasure hunters:

“documentary evidence” furnished to, ;

charts supplied to by Mexicans, ;

enthusiasm of, –;

ruins of smelter in Llano country reported by, ;

evidence furnished to by early historians, ;

as preservers of historical sites, .

Trinity Bay, .

Trinity (Trinidad) River, , .

Tyler County, .

Underwood, J. T., .

Vaca, Cabeza de, .

Valentine, Texas, .

Velasco, , , , , .

Victoria, . , .

Villa, Pancho, .

Villareal, Captain, .

Von Blittersdorf, Louise, .

Waco, , –.

Waco(s), –.

Wade’s Switch, .

Walker, Tom L., .

Way-bill, –, .

Webb, J. O., ., .

Webb, W. P., , .

Webber, Charles W., The Gold Mines of the Gila, ., .;

Old Hicks, the Guide, ., .

Welch, Mike, , .

West, Mrs., , , .

West Texas, , .

Western Story Magazine, .

White Creek, .

[279]

Whitehurst, A., “Reminiscences of the Schnively Expedition of 7,” .

Whitley, Mr., of McMullen County, , , , , , .

Wichita Falls, .

Wichita River, .

Wilbarger, J. W., Indian Depredations in Texas, .

Wild man or woman, ff.

Williams, Dr. Sid, .

Williams, T. W., .

Williamson County, , , , , .

Wilson, Eugene, “Mysterious Music on the San Bernard,” , .

Wilson, Frank H., .

Winkler, E. W., , .

Winters, J. Washington, .

Wissler, Clark, North American Indians of the Plains, .

Woldert, Albert, “The Last of the Cherokees in Texas,” .

Wooten, Comprehensive History of Texas, .

Wright, Robert M., Dodge City, the Cowboy Capital, .

Wright, Mrs. S. J., San Antonio de Bexar, ., .

Xumanos, .

Yaqui(s), .

Yoakum, History of Texas, ., .

Ysleta, , .

Zahm, J. A. (Mozans), Through South America’s Southland, ., .;

The Quest of El Dorado, ., .

Zazala, Adina De, History and Legends of the Alamo and Other Missions, , .

[281]