Title: Whilst father was fighting

Author: Eleanora H. Stooke

Illustrator: Albert George Morrow

Release date: June 6, 2023 [eBook #70920]

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: The Religious Tract Society

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

CHAPTER

III. BOB AND STRAY MAKE AN ENEMY

"Are you asleep, Jackie?"

Bob Middleton, closed the door of the attic which served as a bedroom for himself and his little five-year-old brother as he spoke, and stepped softly to the bedside.

No, Jackie was not asleep. He had sprung up in bed at the sound of Bob's voice, and now cried chokingly—

"Oh, Bobbie, Bobbie!"

"Why, what is the matter, old chap?" Bob, inquired. The question was needless, for he knew his little brother was crying from fear—fear of being alone in the dark. "I hoped I should find you asleep," he went on without waiting for a reply; "it was an hour ago that Aunt Martha put you to bed, and you promised you'd try to go to sleep right away."

"I did try," was the plaintive answer, followed by the anxious inquiry—"Are you coming to bed now?"

"No," said Bob, "I've only come up for a few minutes. Aunt Martha said I mustn't stay long, for she's several errands for me to do yet." He went to the window—it was low in the sloping roof—and pulled up the blind. "There, now!" he cried, "isn't that better? The moon's like a big lamp in the sky, and the stare are shining ever so brightly."

"I can see them," Jackie said, with a sobbing breath. "I wanted Aunt Martha to pull up the blind, but she wouldn't, and—and she said if I got out of bed she'd give me the stick. I hope she won't whip me again, Bobbie; she does whip so hard."

Bob set his teeth and was silent for a minute. Mrs. Mead, their Aunt Martha, was not always kind to Jackie. She was not always kind to him either, but that he felt did not matter. He and his little brother— Jackie was five years younger—had been living with Mrs. Mead for ten months, ever since the beginning of the war with Germany, when their father, a reservist, had rejoined the colours. Their previous home had been in a village some miles from Bristol, where their father had been employed on a farm.

Their mother had died when Jackie had been born, so there had been no one but Aunt Martha to take charge of them when the call to arms had taken their father from them. Mrs. Mead, who was a childless widow, kept a greengrocer's shop in a dingy street in Bristol; and, as she took lodgers, she had no room to spare her little nephews but an attic. From the boys' attic, which was at the back of the house, was a view of the river and the backs of the houses on the opposite bank—not a very cheering view for eyes accustomed to pretty wooded scenery.

"Well," Bob said, "I must be going. Don't cry any more, Jackie. There's nothing to be afraid of up here, and it's quite light now I've drawn up the blind. You can lie and watch the moon and stars. I daresay father's watching them too, out in the trenches—"

"Oh, I want father!" Jackie broke in, "I want father!"

Bob wanted his father quite as much as his little brother did; but he owned a brave heart, and, though it was very heavy, he answered cheerfully—

"I daresay he'll be home on leave soon. Here, let me cover you up!"

He tucked the bedclothes around Jackie, then hurried out of the room, leaving the door ajar. As he ran down the steep, narrow stairs he met a little old woman toiling up, followed by an ugly brown dog. He guessed who she was. There were two attics in the house, and the previous day he had heard his aunt remark that she had let the front attic to an old-age pensioner—a Mrs. Winter. No doubt this little old woman was Mrs. Winter.

"There's a dog following you!" he called out, stopping and looking after her.

"Yes," she said, glancing back at him with a smile, "he's my dog. Stray he's called. Oh, dear me, who's that crying?"

"My little brother," Bob replied; "he doesn't like being left alone— he's afraid."

He hurried on. Mrs. Winter, having reached the top stair, hesitated a minute, then, instead of going into her own attic, walked into the other, Stray at her heels.

Jackie was sitting up in bed, crying loudly. He became suddenly silent when he saw Mrs. Winter.

"Good evening!" she began. "I'm Mrs. Winter. I've come to live in the front attic, and should like to be friends with you and your brother. Now, suppose you tell me your name?"

"Jackie," the little boy answered; "I'm five," he informed her, "and Bob's ten."

Mrs. Winter took a chair by his side. He could see her face plainly in the moonlight. Such a pleasant face it was, although it was old, with bright brown eyes like a bird's and the happiest expression.

"I met your brother on the stairs," Mrs. Winter remarked, "he told me you were afraid because you were left alone. But we're never really alone you know, my dear. Jesus is always with us. Do you know about Jesus, Jackie?"

"Oh, yes," said Jackie; "I go to Sunday school. Jesus is in Heaven."

Mrs. Winter nodded. "Yes, Jesus is in Heaven," she agreed, "and He's here too. He's everywhere. No—" as Jackie glanced around the room— "we can't see Him; nevertheless He's here, and you can speak to Him whenever you like and be quite sure He'll hear you. Don't you know that when you pray you are talking to Jesus? He loves you, and wants you to love Him. Oh, He is such a good friend to have, Jackie! I wonder, now, if you said your prayers to-night?"

"No," the little boy answered; "I forgot."

"Ah! I'm not surprised you felt lonely and frightened. I tell you what, we'll pray together—just you and me. You can kneel upon the bed, and I'll kneel beside it."

They did so, whilst Mrs. Winter offered up a prayer. It was a very simple prayer, which asked Jesus to watch over Jackie and make him feel His presence so that he might not be afraid, and the little boy quite understood it.

"I like her," he said to himself, after Mrs. Winter had bidden him "good-night" and gone away, accompanied by her dog; "she's a very nice old woman. It was kind of her to come to see me. Oh, I do hope she'll come again!"

JACKIE quite meant to keep awake till Bob came to bed, but he fell asleep soon after Mrs. Winter had left him. When he awoke the bright morning sunshine was shining into the attic, and Bob was in the midst of dressing. He told him of Mrs. Winter's visit.

"It was kind of her to come," Bob said, pleased because Jackie seemed to be. "Did you like her? Yes? That's all right, then! She's going to pay Aunt Martha two shillings a week for the other attic and 'do for herself'—that means clean her own room and cook her own food. Come, tumble out of bed, Jackie, or you'll be late for breakfast!"

Quarter of an hour later the two boys went downstairs together to the kitchen, where an untidy maid-of-all-work was preparing to cook bacon for breakfast.

"I'll lay the table for you, Lizzie," Bob told her, and set about doing so, Jackie helping him.

In a short while their aunt appeared upon the scene. She was a short, stout woman, with a bustling manner and a nagging tongue.

"Past seven o'clock and breakfast not yet ready!" she began; "you must have been idling, Lizzie, for I called you in good time! Be careful what you're doing, Jackie! There, now, you careless child, you've spilt the milk—and milk such a price, too! Sit down and be quiet, for goodness sake!"

"He's helping me lay the breakfast things," Bob explained, as Mrs. Mead pushed Jackie roughly aside; "it's only a little drop of milk he's spilt, but I'll go without, then it won't matter."

Mrs. Mead made no response. She was a woman of uncertain temper, and this morning she was in an ill-humour because the lodger who rented her best rooms had given her notice yesterday to leave. She let two sets of rooms; but her lodgers did for themselves, like Mrs. Winter, so they were not much trouble to her.

Breakfast was eaten almost in silence; then Bob was sent to open the shop, and at half-past eight the boys started for school. Jackie attended an infant's school not far from home, but Bob had further to go.

When Jackie came out of school at twelve o'clock almost the first person he saw was Mrs. Winter, who was taking her dog for a walk. He stopped and looked at her, thereby attracting her attention. She did not recognise him at first glance, for he looked very different from the little boy with the tear-stained face and tear-blurred eyes she had seen last night. To-day Jackie's face was all smiles, and his eyes were as blue and clear as the summer's sky.

Her second glance, however, told her who he was, and she exclaimed—

"Why, it's Jackie! How do you do, dear? I'm so glad to meet you, and so's Stray. Come here, Stray, and make friends with Jackie!"

Jackie loved dogs, so he patted and made much of Stray; and Stray, who loved to be noticed, was delighted.

"I suppose you're going home now, Jackie?" Mrs. Winter said inquiringly.

"No," the little boy answered, "I'm going to meet Bobbie. You come too!" He slipped his hand into the old woman's as he spoke, and they walked on together, Stray running on ahead.

Jackie was very interested in Stray, and asked many questions about him. He learnt that he was a come-by-chance.

"I found him in the street one wet night, when he was a puppy," Mrs. Winter explained; "he was shivering with cold, and I think he'd have died if I hadn't taken him home with me. Next day I tried to find his owner, but I couldn't, so I kept him. He's about six years old now."

"Older than me!" exclaimed Jackie, adding, "Oh! I think he's a dear dog!"

"He is," agreed Mrs. Winter; "he's no beauty, but he's as good as gold, and so loving and faithful! I always feel thankful God sent him to me."

"I thought you said you found him?" said Jackie.

"So I did," replied Mrs. Winter smiling; "but I'm sure God put him in my way so that I might befriend him. God is love, you know, and for certain He loves every creature He made. It tells us in the Bible that He cares for the sparrows, and I'm as sure He cares for Stray as I'm sure He cares for you and me."

This was a new idea to Jackie, so he pondered it in silence. Presently Mrs. Winter said—

"Isn't this your brother coming towards us?"

Yes, it was Bob. He looked surprised when he saw Jackie's companions; then a smile lit up his face, and shone in his eyes, which were as clear and blue as his little brother's.

"It was ever so kind of you to go in and talk to Jackie last night, Mrs. Winter!" were the first words he said. "You see," he went on, "Aunt Martha puts him to bed early, and he lies awake getting more and more frightened the darker it gets, and—"

"Oh, he shan't do that any longer if I can help it!" Mrs. Winter broke in. "I'll ask Mrs. Mead if I may sit with him till he falls asleep, shall I?"

"Oh, if you only would!" Bob cried gratefully. "You'd like that, wouldn't you?" he asked Jackie.

"It would be lovely," the little boy answered; "I shouldn't mind its being dark then."

Mrs. Mead was secretly pleased when her new lodger offered to relieve her of the task of putting Jackie to bed every night, and consented at once.

"I used to be a children's nurse," Mrs. Winter told her, "so I understand little people and love them. You will not object to my staying with Jackie for a bit after he's in bed?"

"Oh, no!" Mrs. Mead answered. "I'm afraid you were disturbed by his crying last night. I couldn't let Bob stop with him because I wanted his help—he runs errands for me in the evenings, you see."

As a matter of fact, Mrs. Mead was working Bob much too hard, sending him here, there, and everywhere to fetch and carry loads of vegetables a great deal too heavy for his strength. He had been very high-spirited and the picture of health when he had come to Bristol; but he was daily growing thinner, and paler, and more and more depressed. It took a load of anxiety from his mind, however, to know that no longer whilst he was at work for his aunt in the evenings would Jackie be crying and fretting in the dark.

"Don't you feel tremendously grateful to Mrs. Winter?" he asked Jackie one day, about a week after the new lodger's arrival.

"Oh, yes!" the little boy replied, "I do, Bobbie. She's a dear, and Stray's a dear, too! I love them both! It was kind of God to send them here!"

"How do you know He did?" questioned Bob.

"Because Mrs. Winter told me so," was the prompt response.

"How does she know, Jackie?"

Jackie shook his head.

"She didn't tell me," he said; "but I'll ask her. She did say it, so of course it's true."

THE first time Mrs. Mead called on her new lodger to receive her rent, which had to be paid weekly, she looked around the attic approvingly, so dainty and clean was everything; then she raised her eyebrows in surprise, for seated at the little round table near the window was Jackie, a picture of contentment, his head bent over a picture book Mrs. Winter had lent him.

"Why, Jackie, how comes it you are here?" Mrs. Mead inquired. Without waiting for a reply she turned to Mrs. Winter, and said—"I hope he doesn't worry you; you must send him away if he does."

"Oh, he doesn't!" Mrs. Winter assured her. "I love having him with me, and he didn't know what to do with himself as there's no school to-day."

"Such a mistake giving children a whole holiday on Saturday!" Mrs. Mead grumbled, "I'm sure they don't need it; though I admit I'm glad to have Bob at home to run errands, as Saturday is always my busiest day."

Mrs. Winter paid her rent, and had her rent-book receipted. Then Mrs. Mead observed Stray, who was lying on a mat before the fireplace.

"He seems a well-behaved, quiet dog," she remarked, "and you keep him very clean; his coat looks in good condition, as though it was brushed pretty often."

"It is, every day," Mrs. Winter replied smiling.

"I brushed and combed him this morning," Jackie informed his aunt eagerly; "and, afterwards, he jumped up and licked my face, so he must like me, mustn't he?"

Mrs. Mead nodded.

"It must cost you something to feed him, Mrs. Winter," she said. "I'll tell Lizzie to save our scraps for him in future."

Every day after that a plate of scraps was sent up to Mrs. Winter's attic from the kitchen, so that now Stray was better fed than he had ever been in his life before.

Swiftly passed the summer days, then came August when the schools were closed for a month. It was really no holiday for Bob, because his aunt kept him running errands and allowed him no time to himself. Only on Sundays did he get any rest.

Mrs. Mead always took her nephews to church with her on Sunday mornings. During the remainder of the day she did not trouble about them, as long as they kept out of her way; so when one Sunday afternoon, on their return from Sunday school, Mrs. Winter asked them to take tea with her they accepted her invitation at once.

Jackie was now quite at home in Mrs. Winter's attic; but Bob had never been there before. They had their tea at the little round table near the window. It was a very frugal repast of bread not very thickly buttered, and weak tea; but both Bob and Jackie enjoyed it a great deal more than they had ever enjoyed a Sunday tea with Aunt Martha. Bob thought Mrs. Winter the nicest old woman he had ever known. He told her about their old home in the country, and talked to her of his father; then began to ask questions.

"Has your husband been dead long, Mrs. Winter?" he inquired.

"Nigh twenty years, my dear," she answered; "he was a sailor—a good, God-fearing man. His ship went down with all hands in a storm."

"Oh, then he was drowned!" Bob exclaimed, looking at her sympathetically. "Haven't you any children?" was his next question.

"I had one, a little boy; but when he was about the age of Jackie I had to part with him—God took him to Himself," Mrs. Winter replied. There was a look of pain on her face for a minute, then it gave place to a brighter look. "I'm fond of boys for my own boy's sake," she added smiling, "so you two will always find a welcome here whenever you may care to come."

That first Sunday tea in Mrs. Winter's attic was followed by others, and the friendship between the old woman and the brothers grew apace. Stray had taken a great liking to Bob; so Mrs. Winter was very glad to let Bob take him out sometimes, whilst the boy was delighted to have the dog for company when he was running errands for Aunt Martha.

One evening, at the end of August, Bob, who had been sent late to deliver a heavy load of potatoes at a house a long distance from Mrs. Mead's shop, was returning with his empty basket, accompanied by Stray, when he saw a crowd around the entrance of a big building which he knew to be a hospital for wounded soldiers, and paused to inquire what was doing.

"There's going to be a concert to-night for the patients," someone told him, "and a great lady is going to sing—people are waiting to see her."

"A great lady?" said Bob inquiringly. "Who?"

"Lady Margaret Browning," was the reply, "she's an earl's daughter. Her husband, Captain Browning, is in France where the fighting is."

"Oh, then he's a soldier!" Bob exclaimed, adding proudly, "So's my father!"

A young lady passing, leaning on the arm of an elderly gentleman, caught the ring of affectionate pride in Bob's voice, and looked back over her shoulder at the boy with a smile so full of goodwill and understanding that she won his heart completely. She was wearing a long, dark cloak, and a hood was pulled over her head, but the hem of a white silk gown showed under the cloak. Bob only noticed that she was young, and that her face, with its large grey eyes, was the sweetest he had ever seen. He watched her disappear, with her companion in the crowd, and was about to go on his way himself when he caught sight of something sparkling on the pavement not a yard from him, and picked it up. It proved to be a small brooch, shaped like a sword, the hilt of which was set with bright red stones. He moved under a lamp to examine it.

"Hulloa, youngster!" said a voice behind him at that moment, "what's that you've got there?"

It was a big boy called Tom Smith who had addressed him, whose father kept a pawnshop a few doors from Mrs. Mead's shop. Bob disliked Tom because he was a bully, but he was not afraid of him.

"It's something I've found," he answered. "No!" as the other boy would have taken it from him—"I'm not going to part with it!"

Tom laughed.

"'Finding's keeping'!" he quoted. "You might let me look at it, though!"

Bob did so. Tom looked at it in silence for a minute, then said—

"I see. It's only one of those cheap brooches you can buy anywhere for sixpence-halfpenny. Like to sell it I'll give you a shilling for it."

Bob was shrewd enough to know that if Tom really valued the brooch at only sixpence-halfpenny he would not offer to buy it for as much again nearly as it was worth, so he said he intended to keep it.

"Oh, you do, do you?" Tom cried angrily, with a threatening look. "I'll see about that!"

He tried to snatch the brooch from Bob, but failed. The next moment Stray, all his teeth showing, had flown at him.

"Call him off!" he shouted, "call him off! He's got me by the leg!"

But Stray had only got him by the leg of his trousers fortunately. He dropped his hold the instant Bob bade him do so, and followed Bob quietly when he walked away.

Tom Smith was now in a furious passion.

"I'll be even with you for this!" he yelled after Bob, "with you and that ugly brute of a dog, too! Mark my words—I'll be even with you both!"

BOB hurried home, the brooch he had found safe in the breast-pocket of his coat. He did not show it to his aunt, as she was gossiping in the shop with a neighbour. She broke off in her conversation to tell him she had no further errands for him that night, and ordered him to take his supper and go to bed.

In the kitchen Lizzie had his supper ready. He showed her the brooch, allowing her to examine it in her own hand.

"'Tis lovely!" the girl exclaimed; "I believe those red stones are rubies! How they do sparkle, to be sure!"

"Yes, don't they?" said Bob. "That's how I came to find the brooch. I saw the stones sparkling."

"I've heard that rubies are just as valuable as diamonds," Lizzie told him; "if so, this brooch must be worth a pretty penny."

"What do you call a pretty penny, Lizzie?"

"Pounds, maybe."

"Oh! then that's why Tom Smith wanted to take it away from me!"

Bob told Lizzie all that had passed between Tom and him. She was most indignant.

"A sixpenny-halfpenny brooch, indeed!" she cried. "Oh, I'm glad Stray gave him a good fright! Where is Stray, by the way? Gone upstairs to his missus, I suppose?"

"Yes," Bob replied, adding anxiously, "I hope Tom Smith will never do him any harm—he's such a cruel boy, you know."

Lizzie handed him back the brooch, advising him to take great care of it.

"It may be advertised for," she said; "if so, there's sure to be a reward offered, and you'll get it. Mind you keep it safe!"

"Oh, I will," he assured her; "no fear about that!"

Bob was very tired when by-and-bye he said "good-night" to Lizzie and went upstairs. He made sure that Jackie was asleep, then paid a call on Mrs. Winter. The old woman was seated at her little round table, reading her Bible by the light of a candle. She nodded to a chair, and bade her visitor take it; then, as he obeyed, said, in a tone of concern—

"You look quite done up, my dear!"

"I'm dreadfully tired," Bob admitted, with a weary sigh. "And my legs do ache so—it's growing pains Aunt Martha says. Look here what I've found!" He laid the ruby brooch in front of her as he spoke.

Mrs. Winter looked at it, gave a start, and changed colour. She did not speak, but sat quite still with her eyes fixed on the glittering jewel, whilst Bob explained where and how he had found it, and how Tom Smith had tried to take it from him.

"Do you think it is valuable, Mrs. Winter?" he questioned.

"Oh, yes, undoubtedly!" she answered. Then she took the brooch in her hand and examined it. "How strange if it should be the same!" she murmured to herself.

"What do you mean?" Bob inquired in surprise.

"I've seen a brooch exactly like this one before," she replied; "it belonged to a young lady I knew—I'd been her nurse when she was a little girl. The brooch was given to her by the gentleman she afterwards married; he was in the Army, and a very nice gentleman he was. They went out to India almost directly after they were married, and she died there, leaving him with a little baby girl. Poor Miss Peggy! She used to love her 'Nana,' as she always called me. How well I remember the last time I saw her—not long before my husband died that was, and just before she went to India. 'Nana,' she said, 'don't you forget me! We shall meet again some day!' And so we shall, Bob, when I get to Heaven—I shall find Miss Peggy there safe with Jesus."

There was a minute's silence after that. Mrs. Winter was the one who broke it.

"It's too late to take any steps about finding the owner of this to-night," she remarked, laying the brooch on the table; "but to-morrow you ought to go to the police-station and give notice that you've found it. I think that would be the right thing to do."

"Then I'll do it," agreed Bob promptly; "I'll go to the police-station directly after breakfast, if all's well."

"Do, my dear. And mind you put the brooch in a safe place to-night."

"I wonder if you would keep it for me, Mrs. Winter? Yes? Oh, thank you! Oh, I do wish you'd go to the police-station with me!"

Mrs. Winter considered a minute. "Very well," she agreed, "I will. See, I'll put the brooch away in my desk; it will be safe there."

She placed the brooch under some papers and locked the desk carefully.

"Thank you!" said Bob. "How kind you are to Jackie and me, Mrs. Winter!" he exclaimed. "Jackie says you told him God sent you here—that you know He did, but how can you know it?"

"Because when I was on the look-out for a bed-sitting-room I prayed to Him for guidance and help," Mrs. Winter said simply; "then I heard of this attic, and that was the answer to my prayer, was it not? So I took the attic. It suits me very well. My dear, I always tell God about everything; it makes things so much easier and takes a weight of care from one. This—" laying her hand on her Bible—"tells us to 'Be careful for nothing; but in everything by prayer and supplication with thanksgiving let your requests be known unto God.' Oh, yes, God sent me here sure enough!"

"Jackie and I didn't want to come here at all," Bob admitted; "but we've liked it ever so much better since you came."

Mrs. Winter's face glowed with pleasure on hearing this, and her bright dark eyes had a wonderfully tender light in them.

"My dear," she exclaimed affectionately, "how glad I am! It makes me so happy to think I've been able to brighten your lives ever so little. You and Jackie have become very dear to me. If I had to leave here I should miss you boys dreadfully!"

"And we should miss you dreadfully!" replied Bob gravely. "Aunt Martha says you're a very good, quiet lodger, and she hopes you'll stay," he continued, "so why should you talk of leaving if this attic suits you? You did say it suited you, you know."

"So I did, and I meant it. I don't want to leave, and I am sure Stray does not."

"Good old Stray!" exclaimed Bob. "If it hadn't been for him I should certainly have had the brooch stolen from me, for Tom Smith's ever so much stronger and bigger than I am!"

"Tom Smith must be a very wicked boy, Bob."

Bob nodded. "I expect," he said, "he guessed the brooch was real gold, and if he could have got it he'd have pretended it was he, and not I, who'd found it. It would have been only my word against his."

THE following morning, when Bob went down to breakfast, he found that his aunt had heard of his find from Lizzie, and was displeased because he had not shown it to her.

"I daresay it's a trumpery thing," she said, "but you ought to have let me see it. If you've left it upstairs fetch it at once."

Bob explained that Mrs. Winter was keeping it for him, and had promised to go with him to the police-station about it. On hearing this Mrs. Mead became very angry.

"Mrs. Winter takes too much upon herself!" she cried. "Tell her to give you the brooch at once! And tell her, too, that I hope in future she'll kindly mind her own business! As though I'm not to be trusted to do what's right!"

Bob fetched the brooch from Mrs. Winter, but did not give her his aunt's rude message.

Mrs. Mead made no remark as she examined the brooch. She held it first one way, then another, to make the stones sparkle, then put it in her pocket.

"What are you going to do with it, Aunt Martha?" inquired Bob.

"Keep it safe for you," she replied. "It's very pretty, and I think it's gold; but I can't tell about the stones—whether they're rubies or only red glass. If they're rubies the brooch will be advertised for and there'll be a reward for the finder. Say nothing about it to anyone for the time."

"Then you don't think I ought to take it to the police-station?"

"Not at present. Wait a while and see what happens."

Nothing happened in connection with the brooch that day. But the day following Bob noticed a printed bill in a shop window, which advertised the loss of a brooch exactly answering the description of the one he had found and said that anyone finding it and bringing it to Lady Margaret Browning, at a certain hotel on Clifton Down, would receive a reward of five pounds. He hurried home immediately and told Mrs. Mead what he had seen.

"Five pounds!" she exclaimed, "Humph! that's not so bad!"

"Not so bad!" Bob echoed. "I call it splendid! Oh, do let me have the brooch and I'll take it to Lady Margaret Browning at once!"

"Not so fast!" his aunt replied. "You must wait till after dinner, then I'll go with you. I can leave Lizzie to look after the shop for once, and I daresay Mrs. Winter will not mind taking charge of Jackie."

Mrs. Mead was in high good humour now. Matters were arranged as she wished, and so, about four o'clock in the afternoon, she and Bob arrived at the hotel mentioned on the bill. Mrs. Mead inquired for Lady Margaret Browning, and explained that they had come to return her lost brooch to her. They were immediately shown into a sitting-room where a young lady was seated at a writing-table.

"Oh!" she cried, on hearing her visitors' errand, "how glad I am! Yes—" as Mrs. Mead produced the brooch and handed it to her—"that is it! Oh, how delighted my father will be! It was my mother's—I lost my mother when I was a baby—and father gave it to me on my twenty-first birthday. Please sit down, both of you!"

She had risen at their entrance, but now took her chair again, whilst Bob and his aunt seated themselves side by side on a sofa. Bob, to his great surprise, had recognised Lady Margaret Browning as the young lady who had smiled at him so sweetly outside the soldier's hospital when he had been so proud to say that his father was a soldier. And she was a great lady—an earl's daughter!

"Surely I have seen you before?" she said, looking at him earnestly.

"Yes, miss," answered Bob, blushing.

"Say 'my lady,' Bob," whispered his aunt hastily.

"Oh, never mind!" said Lady Margaret. Then a flash of recognition crossed her face. "Ah, I remember you now," she cried, "and the way you spoke of your father! Is he at one of the fronts?"

"Yes, my lady," Bob replied; "in France."

Lady Margaret looked very interested. She was evidently going to ask Bob more questions about his father, but before she could do so Mrs. Mead interrupted the conversation to explain that she was making a home for her two motherless nephews during her brother's absence.

"Poor little fellows!" Lady Margaret said softly. Then she asked Bob his name and his age. "He looks pale and thin," she remarked to Mrs. Mead after the boy had answered her.

"He grows so fast—that's the reason," Mrs. Mead replied, adding, "And he works hard at school."

"But it's holiday time now, isn't it?" questioned Lady Margaret.

"Oh, yes!" Bob assented, "only—" He broke off and was silent.

He had been about to say that he worked hard in the school holidays, carrying heavy loads of vegetables, but a frowning glance from his aunt had stopped him.

Lady Margaret now rang the bell and ordered tea for her visitors. Bob was too shy to take much, but his aunt drank several cups of tea, and made a good meal on the dainties offered her. There was a cake which was not cut, and that Lady Margaret made into a parcel and gave to Bob to take home to his little brother. He was so pleased that he could scarcely find words with which to thank her, and when Lady. Margaret put five one-pound notes into his hand, the reward for the return of the brooch, he was absolutely speechless.

"Good-bye, Bob," she said, kindly; "I'm going to London to-morrow; but I hope to come here again before long, and if I do I shall try to see you. I should like to hear more about your father. I'm sure he must be a very good father, or you wouldn't love him so much, and be so proud of him. May God bless him and keep him!"

"Good-bye, my lady," the boy replied, looking at her gratefully. "Oh, I do hope I shall see you again! And Jackie would like to see you too!"

"And I should like to see Jackie!" she said, smiling. "Will you please give me your address?" she asked Mrs. Mead.

Mrs. Mead did so. But on the way home she told Bob she thought it most unlikely he would see anything more of Lady Margaret, who would most probably go away and never think of him again.

"Oh, I hope not!" the boy exclaimed. "I liked her so much! And didn't she speak nicely about father? I thought it so kind of her to say, 'May God bless him and keep him!' And the way she spoke, so softly and solemnly! Oh, Aunt Martha, it sounded like a prayer!"

BOB was eager to tell Mrs. Winter about his visit to the grand hotel on Clifton Down, which had seemed to him quite a palace, and all that Lady Margaret Browning had said to him; but he had no opportunity of doing so till the next day when, late in the evening, he went upstairs for the night. Then he had half an hour's talk with her in her attic. She heard all he had to tell with the greatest interest, and remarked smilingly that she supposed he felt himself a rich man now he was the owner of five pounds.

"Oh, yes!" he agreed; "it's a lot of money, isn't it? But the worst of it is Aunt Martha doesn't want me to spend it. She's going to keep it for me till father comes back. I should like to give Jackie a present; but she won't agree to my spending even a few shillings?"

"I think, perhaps she's right," said Mrs. Winter, "If you broke the five pounds you'd probably spend more than would be wise. Think how surprised and delighted your father will be to find you with five whole pounds, Bob!"

"Yes! He shall have them all, Mrs. Winter!" Mrs. Winter nodded.

"Now," she said, "I've something to tell you. I've been talking to-day to someone who knows about Lady Margaret Browning, and I've found out that she's the daughter of that young lady I was telling you about, the 'Miss Peggy' I loved so much. So you see I had seen the ruby brooch before."

"Oh, how strange!" Bob cried, in amazement.

"Yes, isn't it? Miss Peggy's husband wasn't an earl when she married him; he only became one on the death of an uncle a few years since. Oh, how I'd love to see Miss Peggy's daughter!"

"Perhaps you will some day," Bob replied quickly, "for I do believe she means to come and see Jackie and me, though Aunt Martha says she'll go away and not think of me again."

"She'll think of you again if she's anything like her mother," Mrs. Winter told him, "and from what you say, I think she may be. It was just like her mother to ask God's blessing on your father. 'The blessing of the Lord, it maketh rich, and He addeth no sorrow with it.' That's something worth having, isn't it?"

Next morning at breakfast Bob told his aunt that Mrs. Winter had been nurse to Lady Margaret Browning's mother, and she was greatly surprised.

"Well, I never!" she exclaimed, "who'd have thought it! And Mrs. Winter so poor too!"

"Do you think she's very poor?" asked Bob anxiously.

His aunt nodded.

"She told me herself she's only a few shillings a week more than her old-age pension to live on," she said; "it's hard lines for her, because I hear from outsiders that her husband left her a few hundreds—she lent the money to a relative who lost it in his business. If I was she I'd apply to Lady Margaret Browning for help."

"Oh, I don't think she'd like to!" Bob answered quickly, for he realised his kind old friend was not the sort of person to ask charity.

Nevertheless, he quite made up his mind that when he saw Lady Margaret Browning again—he believed he would see her again—that he would tell her all about her dead mother's old nurse.

Bob was kept busy by his aunt that morning, running errands. He was toiling along with a heavy basket filled with vegetables and fruit when he came around a corner upon Tom Smith. He would have passed without speaking, but Tom stood in front of him and stopped him.

"Hulloa; youngster!" was the bully's greeting, followed by the question: "What about that brooch?"

"Well, what about it?" said Bob coldly. Tom gave him a shrewd look. "I suppose you saw the printed bills in the shop windows?" he said inquiringly. "Well—" as Bob nodded—"did you get the reward?"

"Yes, of course."

"And what about me in the matter?" Tom asked, much to Bob's amazement. "You know I saw the brooch on the ground at the same time as you did," he went on untruthfully, "but you were quicker than me and picked it up first."

"I don't know anything of the sort!" Bob cried indignantly. "How can you tell such a wicked story?"

"It's not a wicked story and I dare you to say so! It's true! And my word's as good as yours, I hope! You ought to halve that five pounds with me, or, at any rate, give me something out of it."

"I'm not going to give you anything!"

"You're not?"

"No."

Tom took a step nearer to Bob, and made a threatening gesture as though he would strike him. Bob looked him steadily in the eyes, and did not flinch. The bully hesitated a minute, then a cruel expression crossed his face.

"If you don't give me a share of that five pounds I'll make you wish you had!" he declared. "Come, now, a pound will satisfy me. No? Ten shillings then?"

"I won't give you a farthing," Bob told him, "for I am positive you never saw the brooch before I'd picked it up. Let me pass. I can't stop talking any longer! Do you hear? Let me pass!"

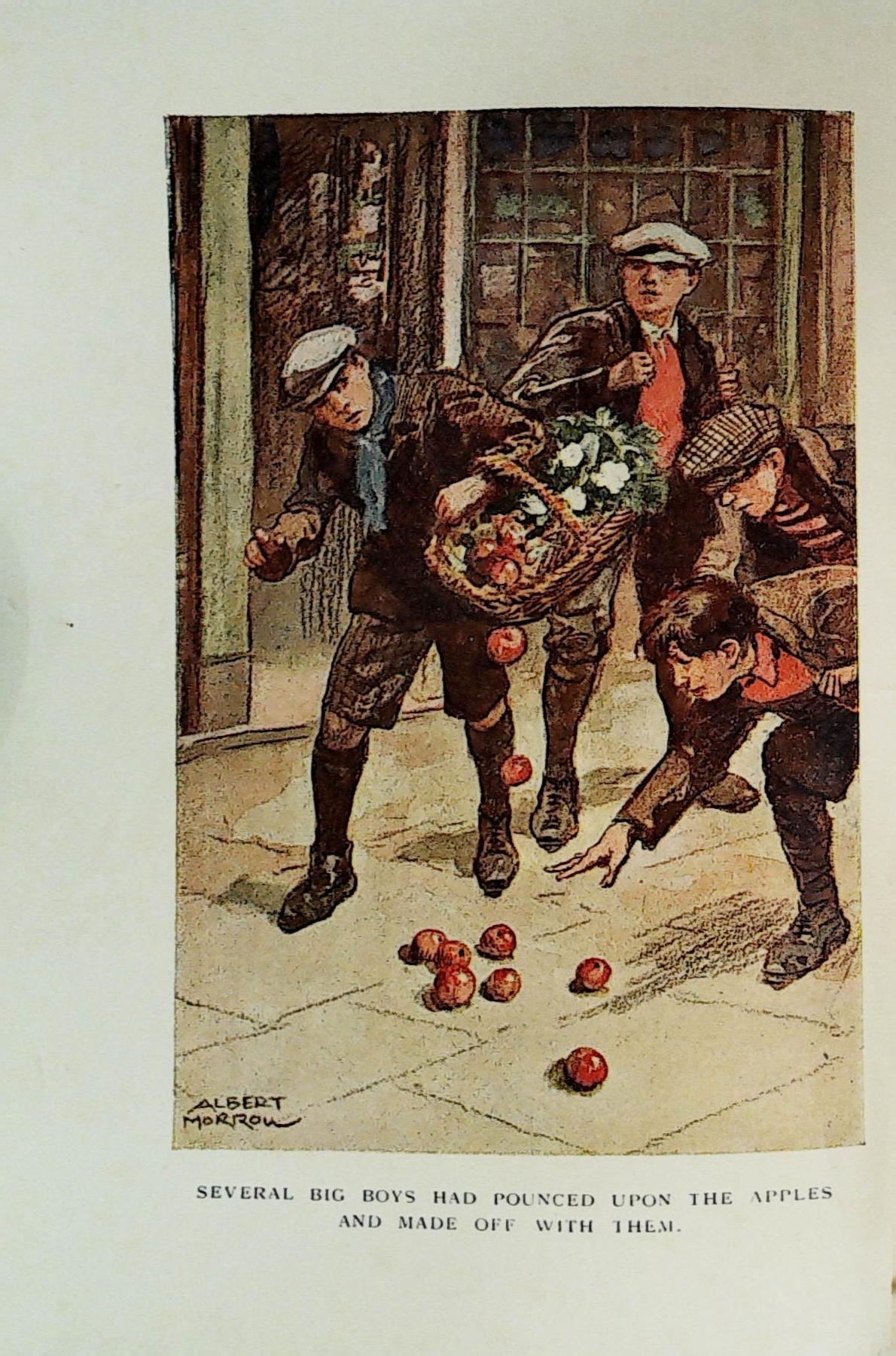

Instead of doing so Tom gave Bob a violent push which made him stagger and upset some apples from his basket. In a minute several big boys, friends of Tom Smith's, who had been standing by, listening and watching, had pounced upon the apples and made off with them. Bob stood aghast with dismay, whilst Tom broke into a roar of laughter and quickly followed his friends.

"Whatever will Aunt Martha say?" thought poor Bob. "And they are eating apples, too, not cheap cooking ones!"

Unfortunately for Bob Mrs. Mead was not in a good humour when he returned home with the tale that some boys had stolen the apples from him, and she was too angry to listen when he attempted to explain all that had happened.

"You're not to be trusted!" she said severely. "Why, those apples were worth twopence each! Early apples are always dear, especially dessert ones. What's that you say, that a boy you'd been talking to was to blame and not you? What business had you dawdling away your time talking to any one, pray? Don't try to make any more excuses, and get out of my sight!"

Bob obeyed. He went upstairs, but found the attics empty. No doubt Mrs. Winter and Jackie and Stray had gone for a walk. He seated himself on the edge of his bed to wait for their return, his heart hot with indignation and the feeling that he had been unjustly treated. By-and-bye, being very tired, he took off his dusty boots, and lay down on the bed to rest. In a few minutes he was asleep.

Bob had been asleep for nearly an hour when he was awakened by voices in the other attic. He sat up, rubbing his eyes, and called—

"Jackie! Jackie!"

"Oh, come here, Bobbie!" was the answer. "Stray's hurted!"

Bob bounded off the bed and rushed into Mrs. Winter's attic. Jackie was there, in tears, and Mrs. Winter, who was kneeling on the floor beside Stray. The dog was allowing his mistress to examine a nasty cut behind one of his ears.

"Oh, Bobbie," Jackie cried, "Stray's hurted drefful! A bad boy did it. He threw a stone and hit him."

"The brute!" exclaimed Bob furiously. "The cowardly brute! It must have been Tom Smith! Oh, poor Stray!—poor Stray!"

HAPPILY Stray proved not to be seriously hurt, and in a few days his wound was healing nicely. Jackie, though he had seen the stone thrown, could only give a very hazy description of the thrower, who, it seemed, had run away the instant he had seen he had hit the dog. Bob would have gone to Tom Smith in hot haste and accused him of having done the cruel deed, but Mrs. Winter had prevented his doing so, by pointing out that they had no proof that Tom was the culprit.

Bob felt sure that Tom Smith was the stone-thrower nevertheless. He did not see him again till after the school holidays, when, one morning on his way to school, he passed him in the street.

"What about that dog of yours now?" Tom shouted after him with a jeering laugh, thus showing that Bob had not misjudged him.

Bob wheeled around sharply, his heart hot with indignation; and went back, his eyes ablaze with anger.

"Look here," he said, "I want a word with you. The dog's not mine, he belongs to one of my aunt's lodgers—but that doesn't matter to you. What I've got to say is this, if you ever throw a stone at him again, I'll go to the police about you and get you punished."

"Do you think I'm afraid of the police?" sneered Tom.

"Yes, I do," Bob answered. "I saw you slink away the other night— you were bullying a boy younger than yourself—when you saw a policeman coming. There's a law to stop people who are cruel to dumb animals. I've heard about it from my father, who can't bear to see animals of any kind badly treated. You're a big coward, Tom Smith, that's what you are!"

"Take care what you say!" shouted Tom, turning crimson. "You're a cheeky youngster! As for your father, he's only a common Tommy!"

"A common Tommy!" echoed Bob, adding quickly, "Anyway, he's a brave man, and he wouldn't hurt a poor dog like you did."

"If you're not careful what you say, I'll give you something you won't like!" Tom threatened.

"You'd better not!" Bob retorted.

And Tom decided that he had better not, for after looking at Bob uncertainly for a minute, he muttered something under his breath, turned sharply on his heel, and moved on.

"I don't think he'll dare do any harm to Stray again," thought Bob; "he saw I meant it when I said I'd go to the police about him."

Mrs. Mead had forgiven Bob by this time for the loss of her apples, and was using him as an errand boy out of school hours as she had done before. Sometimes when he went to bed he was so weary and his limbs ached so much that he could not; get to sleep till the early hours of the morning, and this began to tell on his health. Then, at the end of October, he caught a bad cold on the chest and had to be in bed several days.

During those days it was Mrs. Winter who nursed him. Lizzie brought him his food, and Mrs. Mead came to see how he was night and morning; but it was his kind old neighbour who poulticed his chest, and gave him his cough mixture regularly, and sat with him whilst his little brother was at school, telling him stories, or talking to him of her young days and the children she had had in her care.

"I loved them all," she said, as she was keeping him company one afternoon, "but not one quite so well as Miss Peggy. The little dear was an orphan, just three years old, when I went to be her nurse, and her aunt, who was her guardian, left her entirely to my care. It was I who taught her to love Jesus—to know Him as her Saviour Who died for her. Ah, she loved Him and trusted Him with all her heart, did Miss Peggy! 'I feel He's near me, Nana!' she used to say."

"It's a great thing to feel that," Bob remarked thoughtfully, adding, "Jackie is not half so afraid of the dark now you've made him understand that Jesus is there."

"Bless his dear little heart, no!" Mrs. Winter agreed, with her sunniest smile.

Bob was struck by the brightness of her expression. "I think you're the happiest person I ever knew," he said; "you're so cheerful that it does one good to be with you. Mrs. Winter, I should like to ask you a question—if you won't be offended?"

"Oh, I am sure I shall not be offended!"

"Then—are you very poor?"

"Yes, as far as money goes, and poorer I shall be if food continues to rise in price. But God will provide for me, my dear, don't you fear! See how He's providing for Stray now! I was wondering how I should be able to get food for the dog that day your aunt promised to save the scraps of the house for him. Don't you think God put that kind thought into her heart? I do!"

Stray was generally with his mistress when she visited Bob. He was to-day, lying on the shabby strip of carpet by the bedside. He looked up and wagged his tail every time his name was mentioned. Mrs. Winter stooped and patted him.

"He misses his walks with you, Bob," she said; "I don't take him far enough to satisfy him. I tell you what I think I'll do this afternoon as the weather's fine and sunny. I'll meet Jackie as he comes out of school, and take Stray with me."

"Oh, I wish you would!" Bob cried eagerly. "Jackie didn't come straight home yesterday, and I couldn't think what had become of him. I made up my mind he had met with some accident—been knocked down by a motor-car, perhaps, and killed! He had only been playing with other little boys he told me, and he promised he'd come straight home to-day; but it would be kind of you to meet him."

"Oh, I will!" Mrs. Winter broke in. "I'll take him for a little walk; but we won't be long."

"Oh, I shall know he's all right if he's with you," Bob replied. "Aunt Martha says I'm silly to be nervous about him, and I daresay I am; but almost the last words father said to me were, 'Look after Jackie, Bob!' and I don't think I could face father again if anything happened to him. It's nearly four o'clock, isn't it, Mrs. Winter?"

"It's twenty to four," she answered, rising. "I'll go at once. Come, Stray!"

The dog followed her from the room. A few minutes later Bob heard him scamper down the stairs, barking excitedly, and his mistress trying to quieten him.

"They'll be in time," the boy said to himself; "what Jackie and I'd do without Mrs. Winter now I really don't know!"

JACKIE was delighted on coming out of school to find Mrs. Winter and Stray waiting for him; and when the old woman spoke of a walk, and asked him to go with her, his blue eyes shone with pleasure.

"Oh, yes, please, do let me!" he answered quickly. Then the blue eyes clouded suddenly; and he said with a sigh, "No, thank you, Mrs. Winter."

"Why not, my dear?" she inquired in surprise.

"Because I promised Bob I'd go straight home," he replied.

"Oh, yes! I had forgotten! But Bob knows I'm here to meet you, and he wishes you to come with me; so it's all right."

"Oh, how jolly! Let's go and look at the shops, shall we?"

Mrs. Winter nodded smilingly. A ten minutes' walk brought them to one of the busiest streets in the city, where there were most attractive shops. Jackie liked toyshops best, next to them the sweet shops; and, oh, how Mrs. Winter wished that she had a few pence she could spare to buy a present for her little companion!

"I'm sorry I've no money to spend, Jackie," she said regretfully, by-and-bye.

"So'm I," the little boy replied; "we'd buy something for Bobbie if you had, wouldn't we? But, never mind, we can tell him about all the beautiful things—he'll like to hear about them."

"Fortunately there's no charge for looking," Mrs. Winter remarked, as they stopped before a toyshop. "Do you see that big Teddy-bear, Jackie?"

"I like horses better than Teddy-bears," he told her, "I like that horse there." He pointed to a toy worth a couple of shillings. "Bobbie was going to buy it for me, only Aunt Martha wouldn't let him have the money. He says when father comes home perhaps I may have it—if it's not sold before then."

"If it is, I daresay there are others in the shop you will like as well. Come, my dear, it's nearly five o'clock—time we turned homewards now."

The last shop they stopped to look at was a sweet shop. Jackie's eyes fastened themselves on some sugar mice—white ones and pink ones.

"I wonder if they're 'spensive," he said wistfully.

"They're marked a penny each," Mrs. Winter answered. Oh, surely she could spare one penny? Yes, if she drank her tea without milk for a couple of days. She took her purse from her pocket, opened it, and the next moment a penny was in her little companion's hand.

"Buy yourself a mouse, my dear!" she said kindly.

"Oh, thank you, thank you!" Jackie answered. He had flushed with pleasure, but his blue eyes were lifted to her face wonderingly. "You said you hadn't any money to spend," he reminded her.

"I know I did, and I thought I hadn't," she replied, "but I've suddenly remembered that I can do without this penny. Now, are you going to have a white mouse or a pink one?"

"I've seen white mice," the little boy remarked thoughtfully, "but never pink ones. I wonder if there are really pink mice—the pink ones lock very pretty, don't they? I think I'll have a pink one."

He went into the shop and made his purchase, whilst Mrs. Winter waited outside. The girl who took his order offered him the mouse without putting it in paper.

"I want it wrapped up; please," he said, "I'm not going to eat it— not now anyway."

"Paper's so dear on account of the war that we've got to be careful of it," she told him. Nevertheless she put the pink mouse into a little paper bag. "There, my dear," she said, handing him his purchase, "will that do?"

"Oh, yes, thank you!" smiled Jackie. He took the bag and gave her his penny.

"Good afternoon!" she nodded.

"Good afternoon, miss!" the little boy answered politely, as he left the shop.

He rejoined Mrs. Winter, and ten minutes later they reached home. As they entered the house by the side door Mrs. Mead came into the passage from the shop. She had a newspaper in her hand.

"I've been up with Bob," she said, addressing Mrs. Winter, "and have taken him news of his father. It's in the newspaper—indeed, it's in every newspaper, I hear. My brother's proved himself a real hero, Mrs. Winter; he's done a very brave deed—gone out under fire again and again and brought in several men who were wounded. Now, what do you think of that?"

"I think it was splendid of him!" Mrs. Winter declared. "Oh, how proud you must feel of him, Mrs. Mead! And he is quite safe himself? Yes? Oh, thank God! Jackie, you don't understand, darling!" She stooped and kissed the little boy who stood by listening, looking very puzzled.

"How fond you are of children!" exclaimed Mrs. Mead. "I've bought two newspapers," she went on, "and I've given one to Bob—he'll let you see it, I daresay. The other I want to keep to show folks. Run upstairs to Bob, Jackie, he'll explain to you about father! I'll send your tea upstairs. You shall have cake and jam, as it's a red-letter day, I'm sure. And why not invite Mrs. Winter to tea with you? You won't have to wait for tea till your kettle boils if you wouldn't mind having it with the boys for once in a way, Mrs. Winter."

"Mind?" cried Mrs. Winter. "Oh, I should like it! You are kind, Mrs. Mead."

Mrs. Mead looked pleased but surprised. She did not know how very bare was the corner cupboard in which her attic lodger kept her stores.

"Well, and aren't you kind to the children?" she said. "See, what you've done for Bob! I couldn't have spared the time to look after him as you've done. Don't talk of being kind!"

Mrs. Mead bustled away, whilst Mrs. Winter went upstairs; Jackie had run on. When the old woman had taken off her bonnet and cloak she hastened to the boys' attic, and found Bob posted up in bed. He had made Jackie understand what their father had done.

"And he might have been killed himself," he was saying as Mrs. Winter entered the room, "but God kept him safe. Oh, if he had been killed—"

"'Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends,'" Mrs. Winter interposed softly.

Bob looked at her with a simply radiant smile.

"Oh," he cried, "I do feel so proud of father! Hasn't he done splendidly? I wonder what Tom Smith will call him now! A common Tommy, indeed!"

By-and-bye Lizzie appeared with the tea things. She cleared the dressing-table, which was made of two wooden boxes, and laid the meal there; and Jackie put his pink mouse in the centre—not to be eaten, but to be looked at.

"There," she said, "now you've got everything—bread and butter, and jam, and cake, and a real good cup of tea—and all you've to do is to enjoy it."

"It's quite a feast," Mrs. Winter replied, adding, "Thank you, Lizzie."

Lizzie departed smiling; but in a few minutes she returned, something wrapped in newspaper in her hand.

"Here's a nice meaty bone which the first-floor lodger didn't want," she said; "it's for Stray. Missus said he was to have it."

So Stray, too, had a share in the attic feast.

WHEN Bob recovered from his cold he expected that his aunt would want his services every evening again; but she had been obliged to engage a man during his illness, and had decided to keep the man on. She was beginning to realise that she had really worked the boy too hard; she had not meant to be unkind to him.

"Lady Margaret Browning was right, you do look pale and thin, Bob," she told him; "you might be half-starved by the look of you. But, though everything's so dear, I don't stint you in food, and I can't understand why you should look as if I do!"

"I think I shall be all right if I don't have such heavy loads to carry," Bob answered; "they used to do me up, and when I got to bed I couldn't sleep—I ached so."

Mrs. Mead looked at him uneasily. His thin white face seemed to reproach her, and she regretted that she had not been kinder to her brother's children. Seeing how they had grown to love her attic lodger, she knew that she, too, might have won their love had she tried to do so.

"Well, Bob," she said, and there was a gentler note in her voice than the boy had ever heard in it before, "take things easy for a while. What you've to do now is to pick up your strength and get rid of your cough."

The first day of Bob's return to school he encountered Tom Smith as he was coming home in the afternoon. The bully stopped him.

"Wait a minute," he said, "I want to speak to you."

"Well?" Bob said inquiringly.

"I've been reading about your father in the newspaper," Tom informed him; "if it's true what the newspaper says he's done—"

"Of course it's true!" interrupted Bob, adding, "I told you he was a brave man!"

"Yes, you did," Tom assented, "I suppose you're mighty proud of him?"

"That I am!"

"So you ought to be!"

Bob was astounded. That his enemy, who had sneered at his father for being a common Tommy, should say this!

"I expect he'll get a medal or something?" Tom suggested, after a brief silence.

"I don't know," Bob replied. Such an idea had not occurred to him before, and he thrilled with delight at the mere thought of it.

"You know he might have been killed," Tom reminded him; "he must have known that, yet he went out under fire again and again."

"Yes," Bob agreed; "but you see, the men he went to help were wounded and couldn't help themselves. I've heard him say often that there's no call to be afraid of anything or anyone whilst we're doing what's right, because then God's with us. He just did what he thought was right, I expect, and—well, that was how it happened!"

There was another silence, during which the two boys regarded each other rather doubtfully. Tom was the one to break it.

"Look here," he said, "I'm sorry I called your father a common Tommy. He's a real hero and no mistake! If he comes home I hope you won't tell him—" He paused momentarily, then continued: "Didn't you say he couldn't bear to see animals of any kind badly treated? Yes? Well, look here, don't tell him I stoned that old woman's dog. I'll promise never to do it again, if you won't tell him."

Bob gave the promise readily, astonished; and at the same time very relieved, for he had been most anxious about Stray, fearing Tom might do him some further injury.

"He's a capital dog," he said, "and very gentle really. He'd never have flown at you if you hadn't—"

"Oh, I understand all about that!" interrupted Tom hastily. "What's his mistress called?" he inquired.

"Mrs. Winter—she's a real good sort. She lives at my aunt's, you know; rents one of the attics, so Jackie and I know her well."

"I suppose she's very poor if she lives in an attic," remarked Tom; "what makes her keep a dog, I wonder?"

Bob explained that Mrs. Winter had found Stray, and, seeing that Tom appeared interested, told him the story as Mrs. Winter had told it to Jackie and Jackie had repeated it to him.

"What a queer old soul she must be!" Tom exclaimed, laughing heartily but not ill-naturedly, "to think God sent the dog to her, I mean! Such a funny idea! Is she quite right here?" He tapped his forehead meaningly.

"Right in her head? Oh, yes!" Bob answered, adding, "And so you'd find, if you talked to her!"

No more passed between the boys then; but one fine Saturday afternoon, a few weeks later, Tom Smith waylaid Bob and Jackie, as they were returning from a walk accompanied by Stray, and tried to make friends with the dog. At first Stray treated Tom with suspicion and would not be touched by him; but at last he realised that the boy had only friendly intentions towards him now, and allowed him to pat him.

"He's wearing a very shabby collar," observed Tom; "the leather's nearly worn out where the fastening is. It won't last much longer."

"I'm afraid it won't," answered Bob; "I don't know what Mrs. Winter will do about it, because I'm sure she can't afford Stray a new collar."

"A big dog like that ought to have a really strong collar made of the very best leather," Tom said, "but leather's gone up in price a lot because of the war. A new collar would cost a good bit. What are you staring at, youngster?" he asked, addressing Jackie, who was looking at him very seriously.

"At you," the little boy answered promptly. "You're Tom Smith, aren't you, the boy who threw the stone at Stray and hurted him? Did you really do it on purpose—to hurt him? Oh, how could you have been so cruel!"

"Look here, don't let's say any more about it," Tom said, reddening. "I shan't do it again; Bob knows that. Do you like sweets?"

He produced a small packet of sweets as he spoke, and would have pressed it into Jackie's hand, but the little boy's good will was not to be bought.

"No, thank you," Jackie said, "unless you are sorry that you hurted Stray. Are you?"

"Of course I am!"

Jackie glanced at Bob, who gave him a nod; then he accepted the sweets, and after that Tom Smith walked home with them.

"I really don't know what's come over him," Bob remarked to Mrs. Winter, when discussing Tom's changed behaviour with her that evening; "and wasn't it strange of him to make me promise not to tell father that he'd hurt poor Stray?"

"He evidently has a great admiration for your father," Mrs. Winter answered, "and would not care to have his bad opinion. There must be good in the boy or he would not feel like that."

"I don't mean to have much to do with him though," Bob said decidedly; "I can't—after what's gone by. To-day he seemed as though he wanted to be friendly, but—oh, I couldn't have Tom Smith for a friend!"

"BOBBIE," said Jackie, "I wonder if Mrs. Winter will ask us to tea to-day?"

"I don't know," his brother answered; "I don't expect so."

It was Sunday afternoon, and the boys were returning from Sunday school. They had not been invited to take tea with Mrs. Winter for several weeks. At first Bob had been puzzled to know the reason, but he was beginning to fear that it was because their kind old friend was not in the position to entertain guests. He knew that food had become very expensive, and suspected Mrs. Winter had all she could do to provide necessaries for herself.

"Don't you think she wants to have us?" Jackie inquired wistfully.

"Oh, yes!" Bob assured him, adding quickly, "Don't speak about it to her, Jackie, whatever you do!"

"Why not?" questioned Jackie.

"It might hurt her," Bob replied, sighing.

Jackie looked puzzled, but he said no more. That afternoon the boys had tea with their aunt in the kitchen. Lizzie had gone to her home, which was in Bristol.

During the meal Mrs. Mead remarked—

"I suppose Mrs. Winter's grown tired of your company, as she doesn't ask you to tea with her now. I'm afraid you wore out your welcome."

"Oh, no!" cried Bob. Then, as Mrs. Mead laughed, he flushed and said: "I think she can't afford to have us to tea any longer, Aunt Martha."

Mrs. Mead became serious in a minute.

"I wonder if she can be as poor as that?" she said thoughtfully. "She may be. She had no fire the other day when I went up for her rent, and the weather was bitter. Poor old soul! I know what I'll do; I'll ask her to supper. I owe her something for her kindness to you boys."

So Mrs. Winter was asked to supper, and came—Stray too. Afterwards she sat by the fire for half an hour, and that night she went to bed warm, which she had not done before for several weeks.

The next day, on their return from school in the afternoon, Bob and Jackie learnt that their aunt had had a visitor.

"I never thought to see her again," she said, her face expressive of gratification, "and I was never more surprised in my life than when she threw back her veil—she came in a motor-car—and I recognised Lady Margaret Browning."

"Oh!" cried Bob excitedly. Then he drew a deep sigh of disappointment.

"I'm so sorry Jackie and I weren't here," he said regretfully. "Did she come in, Aunt Martha?"

"That she did, and we had a nice chat together. She'd read about your father in the newspaper, and spoke so nicely about him. I felt proud to think he was my brother. It seems her father has a big house on his estate in Somersetshire, which he's turned into a soldiers' hospital, and she's helping nurse the patients. She's going back there in a few days. But she said she should call again; she's staying with friends at Clifton for a little change, because she's been working too hard nursing."

"Did you tell her about Mrs. Winter; that Mrs. Winter used to be her mother's nurse, I mean?" Bob asked eagerly.

Mrs. Mead shook her head.

"I quite forgot all about the old woman," she admitted, "But, if I'd remembered she wouldn't have been able to see her," she added, "for Mrs. Winter's been out with her dog all the afternoon."

When Mrs. Winter returned Bob went to her attic and told her of Lady Margaret Browning's visit. She would have liked to have had a peep at her, she said, to see if she was like "Miss Peggy"; then she drew Bob's attention to Stray and the collar he was wearing—not his old, shabby one, but another made of strong leather and ornamented with brass studs.

"What a handsome collar!" Bob exclaimed. "Why, it must have cost shillings!"

"I expect it did," Mrs. Winter agreed, "and it's all but new. It's a present. Oh, Bob, I've had such a fright this afternoon! Do you notice that Stray is wet? Well, he's been in the river!"

"Did he fall in?" asked Bob.

Mrs. Winter shook her head.

"Oh, no!" she replied, "he jumped in; but I'll tell you what happened. We'd been for a walk and gone further than I'd meant to, so we came home by the back lane as it was the shorter way. A lot of children were playing in the lane, some of them close to the river. Suddenly I heard a splash and a scream, and some one shouted there was a little girl in the river. Then there was another splash. Stray had seen what had happened, and had gone to the child's rescue!"

"Oh, dear, brave Stray!" Bob cried, putting his arms around the dog, wet though he still was, and hugging him, "And he saved the little girl?"

"Yes. He caught her by her skirt and swam with her to the bank, where I took her from him. She was not hurt in the least, only frightened. Someone had run for her parents, and you can imagine their joy at finding her safe. They could not make enough of Stray, and insisted I should bring him into their house so that they might give him something to eat. Then, whilst Stray was eating a plateful of nice scraps, and the little girl's mother had taken her upstairs to change her clothing, the father left me a minute and returned with this handsome, brass-studded collar, which he said he thought would just fit Stray, and begged me to accept it. I didn't quite like taking it, but he explained that it hadn't been pawned—oh, I forgot to say that the little girl's parents were the people at the pawnshop!"

"Then the little girl is Tom Smith's sister!" exclaimed Bob excitedly.

Mrs. Winter assented.

"Mr. Smith said he'd bought the collar from someone whose dog had died," she continued, "and that I needn't mind taking it, and that he'd feel hurt if I didn't. So then I accepted it, of course, and very glad I am Stray has it. Mr. Smith took off the plate with my name on it from the old collar, and put it on the new one."

"I see," Bob said, examining the collar. "I suppose you didn't see anything of Tom at the Smith's?"

"Yes, he came in whilst I was there, and his father told him what had happened. 'Your sister would have been drowned but for the dog!' he said. Then I told them that I didn't usually go home by the back lane, and I felt sure God had sent me that way to-day, and they must thank Him for sparing them the life they loved. I think they will, Bob."

"I should think so, too!" Bob agreed. He caressed Stray again. "Dear old fellow!" he murmured. "Good, brave, old dog!"

LADY MARGARET BROWNING kept her word and called again. This time she came rather later in the afternoon, shortly before the boys returned from school, and Mrs. Mead remembered to tell her that her mother's old nurse occupied one of the attics.

"Oh, I've heard my father mention her!" she cried; "he was speaking of her only the other day, and wondering if she was still living. My mother loved her ever so dearly. Oh, please, please let me see her!"

So it came about that when the boys arrived home, on going straight upstairs to Mrs. Winter's attic, as they usually did to fetch Stray for a walk before tea, they found Lady Margaret Browning there. She was seated close to Mrs. Winter, and the two were talking of "Miss Peggy." Stray, standing with his head resting on her knee, was looking up into her face approvingly.

"Come in, both of you!" Mrs. Winter said, as the boys stood hesitating in the doorway; and they obeyed, Jackie following his brother shyly.

Lady Margaret rose and shook hands with Bob, then she kissed Jackie, and, seating herself again, drew the little fellow close to her and kept her arm around him whilst she talked to the others.

Jackie stood very still, every now and again glancing up into the sweet, fair face of Mrs. Winter's visitor, which, each time he did so, smiled tenderly at him. So this was the lady who had given Bob so much money in return for her brooch. Yes, she was wearing the brooch now. As his eyes noted it she put up her hand and touched it.

"I've had the fastener made safer," she said to Mrs. Winter. "Oh, I was so delighted to get it back! I shall always feel thankful to Bob for having found it."

"I'm so glad I did," said Bob, adding quickly, "I don't mean because of the reward."

"Aunt Martha's kept all the money!" Jackie stated abruptly.

"She's going to keep it for me till father comes back, then I'm going to give it to him," Bob explained; "but I'd have liked to have spent a little of it. I wanted to give Jackie a toy horse, and Mrs. Winter something."

"I take the will for the deed, Bob," smiled Mrs. Winter.

By-and-bye, Lady Margaret rose to leave, and Bob accompanied her downstairs. Mrs. Mead bustled out of the shop into the passage on hearing them talking. Lady Margaret, who had come on foot, asked if Bob might go with her as far as the street where she meant to take a tram.

"Certainly, my lady," Mrs. Mead replied; "he'll be proud and pleased, I'm sure."

Bob was indeed proud and pleased as he walked along by Lady Margaret's side. She asked him many questions about Mrs. Winter, and he told her all he knew about her, and how wonderfully kind she had been to Jackie and him.

"Aunt Martha didn't understand about Jackie," he explained; "she thought he was naughty because he always cried when she put him to bed. It was not that—he was frightened. But now he isn't frightened any more because Mrs. Winter's taught him Jesus is with him. If it's ever so dark he doesn't cry now."

"Oh, Bob, how glad you must be!" Lady Margaret said earnestly. "I hope Jackie will always remember Jesus is with him. We all need to remember that, don't we, because life is so dark sometimes? Then it is such a comfort to know there is One in the darkness to cling to, and that out weakness may become strength through Him."

They had reached the tramline now, after having passed through several back streets, but there was no tram in sight. Lady Margaret glanced at her watch, then said—

"See, here is a nice toyshop! Tell me what sort of horse you meant to give Jackie, I should like to buy one for him."

"Oh, how kind of you, my lady!" cried Bob. "Oh, thank you, thank you!"

He followed her into the shop. Quickly the purchase was made, wrapped in brown paper, and placed in Bob's arms. By that time a tram was coming, and they had to hurry from the shop. A minute later Bob was standing alone on the pavement, and Lady Margaret Browning had gone.

Jackie was almost overwhelmed with Joy and gratitude when he saw the present Lady Margaret Browning had sent him by his brother.

"Oh, Bobbie!" was all he said at first, but the sight of his glowing face, as he knelt on the kitchen floor examining the toy, told of the feelings he could find no words to express. "Well, now, this is certainly very kind of Lady Margaret," remarked Mrs. Mead, who was standing by; "she must have taken a fancy to you, Jackie. Bob, do you know she thinks your father will have the Military Cross—he's almost sure to, she says."

So it was no great surprise when a few days later news came that the boys' father had indeed won the medal, and many were the warm congratulations Mrs. Mead and her young nephews received.

"Your father deserves it," Tom Smith said to Bob heartily; "I want you to tell me more about him—I like hearing of people who do brave things. I say—" he reddened as he spoke—"I suppose you've heard that Stray saved my little sister from drowning?"

"Yes. And I've seen the collar your father gave him; it's a beauty."

Tom nodded. He was silent a minute, then he said—

"Look here, I told a lie about that ruby brooch, I never saw it till you had it in your hand after you'd picked it up. I'm sorry now I behaved as I did about it. Do you believe me?"

"Yes," Bob answered, much astonished. "Say no more about it!" he added, observing that Tom really looked ashamed of himself.

"All right!" Tom agreed, "I'm sure I don't want to!" He paused hesitatingly, then asked: "Can't we be friends?"

"Perhaps, if you stop bullying and telling lies," Bob replied doubtfully.

"Oh, well," Tom said, his countenance brightening, "I'll see what I can do!"

"OH, Bobbie, look! Oh, quick! look, look!" Jackie clutched his brother's arm as he spoke, and pointed excitedly after a handsome motor brougham which had just passed them, and was now disappearing around a corner of the street. The boys were on their way home from morning school.

"Oh, you didn't see!" the little boy cried, in a tone of disappointment, "and Stray was looking out of the window, too! Oh, I wonder if he saw us? And Mrs. Winter!"

"You don't mean to say that Mrs. Winter and Stray are in that beautiful motor-car?" cried Bob incredulously. "Haven't you made a mistake, Jackie?"

"Oh, no, I haven't!" Jackie protested. "Oh, I do wish you'd seen them! Where can they be going?"

"Let's hurry home and find out."

Arrived at home they went direct to the kitchen, and questioned Lizzie. The girl was looking pleased and excited.

"Oh, so you met the car!" she said; "it belongs to some grand folks living on Clifton Down, friends of Lady Margaret Browning's."

"The friends she's staying with?" inquired Bob.

Lizzie nodded. "The chauffeur brought a note for Mrs. Winter, and said he was to wait," the explained, "I took the note up to her and waited while she read it. It put her in a bit of a fluster. She told me Lady Margaret Browning wanted her to spend the day with her and bring Stray with her, and the car had been sent to fetch them. So she's gone, and Stray too—looking just as though he'd been used to ride in a car all his life! Now, you may depend something will come of this. Missus will soon be losing her attic lodger, I expect."

"Why should you think that?" asked Bob quickly.

"Never you mind!" replied Lizzie, mysteriously. "If I'm right we all ought to be glad, so don't you begin to pull a long face. Mrs. Winter's been very poor, but I'm beginning to hope she's seen her poorest days. We shall see!"

When the boys met their aunt at dinner they found that she, too, expected to lose her attic lodger before long.

"I shall be sorry when she goes," she remarked, "for she's paid her rent regularly and been kind to you boys. A real good woman she is, and I wish her well."

The shop was closed, and Jackie was in bed and asleep that night before Mrs. Winter and Stray came home. They returned in the motor brougham, and were met by Mrs. Mead in the passage.

"Come into the kitchen and have a warm by the fire before you go upstairs, Mrs. Winter," she said. "I hope you have spent a pleasant day."

"Yes, thank you," Mrs. Winter answered; "a very pleasant day."

She took the chair Mrs. Mead offered her by the fire, whilst Stray went to Bob, who put an arm around his neck and hugged him.

"I've missed you, old chap!" the boy whispered. "Was he good, Mrs. Winter?" he asked.

"As good as gold!" Mrs. Winter replied. "Oh, I've had such a happy time with Lady Margaret and her father!" she continued; "her father came last night to fetch her home. They made so much of me—treated me quite like a friend! If only Miss Peggy had been there, but—oh, God knows best! And Lady Margaret's so like her mother! I told her father so—he liked hearing it. I couldn't think of him as a great nobleman! To me he will always be just Miss Peggy's husband!"

She paused a minute, smiling, then went on—

"Oh, he was wonderfully kind! He had a long talk with me alone, and said he was sorry to hear I was not very well off; and then he offered me a cottage, rent free, on his estate in Somersetshire, and the wherewithal to live there—"

"Oh, dear!" broke in Bob. "Oh, I know I ought to be glad, but—oh, I suppose I'm dreadfully selfish! I don't want you to go away!"

"You'd like to keep me here?" Mrs. Winter asked eagerly. "Oh, my dear!" she exclaimed as he nodded, "how sweet it is to think that!— to know I should be missed if I went!"

"If?" said Mrs. Mead inquiringly. "I suppose there's no doubt about it? Of course you're going?"

Mrs. Winter shook her head.

"No," she said. "No. I told Miss Peggy's husband I was too old to live in a cottage alone, and that I liked to be where other people—especially young people—were about, and that I'd become quite attached to my attic home. I said I wished to remain here, and if he'd be so generous as to help me with a little money, I should have nothing in the world left to wish for. And that's what he's going to do. I've explained all this because you've been so kind, Mrs. Mead—"

"Kind? Me?" interrupted Mrs. Mead in astonishment. "What have I done?"

"Helped me feed Stray for one thing," Mrs. Winter replied, "and let me come here sometimes and warm myself when I've had no fire upstairs for another. I wouldn't wish a better landlady than you."

"And I'm sure I wouldn't wish a better lodger than you!" said Mrs. Mead heartily; "I doubt if you're doing the best for yourself, but I'm very glad you're going to stay on. But a dear little cottage in the country all to yourself! Have you considered—"

"I've considered everything!" Mrs. Winter interposed, her bright, dark eyes shining happily; "and I'm sure I've decided for the best."

Bob said nothing; but he drew a deep sigh of intense relief, and by-and-bye slipped upstairs to tell Jackie, if he should be awake, that there was no fear of Mrs. Winter's going away. But Jackie was sleeping peacefully, so he did not disturb him, and went to bed too.

Both boys were asleep when some while later Mrs. Winter, carrying a lighted candle, opened the door noiselessly and peeped into the room. She tip-toed to the bed, and stood for a minute or two looking tenderly and lovingly at the sleepers, whilst she breathed a hope, which was actually a prayer, that God would permit her to continue to care for them until their father came home.

THE END.