Title: Salome's burden

or, the shadow on the homes

Author: Eleanora H. Stooke

Illustrator: C. Howard

Release date: November 17, 2023 [eBook #72157]

Language: English

Original publication: London: S. W. Partridge & Co., Ltd

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

SALOME'S FRESH, SWEET VOICE RANG CLEARLY

THROUGH THE DIM CHURCH.

OR

THE SHADOW ON THE HOMES

BY

ELEANORA H. STOOKE

AUTHOR OF

"MOUSIE; OR, COUSIN ROBERT'S TREASURE,"

"A LITTLE TOWN MOUSE," "SIR RICHARD'S GRANDSON,"

"LITTLE MAID MARIGOLD." ETC.

WITH FOUR ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON

S. W. PARTRIDGE & CO., LTD.

E.C. 4.

Made in Great Britain

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER

Salome's Burden.

Salome's Trouble.

IT was summer time. The day had been oppressively hot; but now, as the sun disappeared like a ball of fire beyond the broad Atlantic, a cool breeze sprang up, and the inhabitants of the fishing village of Yelton came to their cottage doors and gossiped with each other, as they enjoyed the fresh evening air.

Yelton was a small, straggling village on the north coast of Cornwall. It owned but two houses of importance—the Vicarage, a roomy old dwelling, which stood in its own grounds close to the church; and "Greystone," a substantial modern residence on a slight eminence beyond the village, overlooking the sea. The fishermen's cottages were thatched, and picturesque in appearance, having little gardens in front where hardy flowers flourished; these gardens were a-bloom with roses and carnations on this peaceful June evening, and the showiest of them all was one which, though nearer the sea than the others, yet presented the neatest appearance of the lot. This was Salome Petherick's garden, and Salome was a cripple girl of fourteen, who lived with her father, Josiah Petherick, in the cottage at the end of the village, close to the sea.

Salome had been lame from birth, and could not walk at all without her crutches; with their help, however, she could move about nimbly enough. Many a happy hour did she spend in her garden whilst Josiah was out in his fishing boat. She was contented then, as she always was when her father was on the broad sea, for she felt he was in God's keeping, and away from the drink, which, alas! was becoming the curse of his life. Josiah Petherick was a brave man physically, but he was a moral coward. He would risk his life at any hour—indeed, he had often done so—for the sake of a fellow-creature in peril. He was fearless on the sea, though it had robbed him of relations and friends in the past, and if help was wanted for any dangerous enterprise, he was always the first to be called upon; but, nevertheless, there was no greater coward in Yelton, than Josiah Petherick on occasions. He had lost his wife, to whom he had been much attached, five years previously; and, left alone with his only child, poor little lame Salome, who had been anything but a congenial companion for him, he had sought amusement for his leisure hours at the "Crab and Cockle," as the village inn was called, and there had acquired the habit of drinking to excess.

As Salome stood leaning on her crutches at the garden gate on this beautiful summer evening, her face wore a very serious expression, for she knew her father was at the "Crab and Cockle," and longed for, yet dreaded, his return. She was a small, slight girl, brown-haired and brown-eyed, with a clear, brunette complexion, which was somewhat sun-burnt, for she spent most of her spare time in the open air. Having passed the requisite standard, she had left school, and now did all the work of her father's cottage unaided, besides attending to her flowers; and Josiah Petherick was wont to declare that no man in Yelton had a more capable housekeeper. The neighbours marvelled that it was so, for they had not thought the lame girl, who had been decidedly cross-grained and selfish during her mother's lifetime, would grow up so helpful; but Mrs. Petherick's death had wrought a great change in Salome, who had promised faithfully "to look after poor father" in the years to come. Salome had endeavoured to be as good as her word; but her influence over her father had not proved strong enough to keep him in the straight path; and many an evening saw him ramble home from the "Crab and Cockle" in a condition of helpless intoxication.

"Enjoying the cool breeze, Salome?"

Salome, whose wistful, brown eyes had been turned in the direction of a row of cottages at some distance, outside one of which hung a sign-board representing on its varnished surface a gigantic crab and a minute cockle, started at the sound of a voice addressing her, but smiled brightly as she saw Mr. Amyatt, the vicar of the parish. He was an elderly man, with iron-grey hair, stooping shoulders, and a thin, clean-shaven face.

Ten years previously, he had accepted the living of Yelton, when, broken down in health, he had been forced to resign his arduous duties in the large manufacturing town where he had laboured long and faithfully. And the fisher-folk had grown to love and respect him, though he never overlooked their failings or hesitated to reprove their faults.

"I am waiting for father," Salome answered frankly. "His supper is ready for him, and I am afraid it will spoil if he does not come soon. It is a beautiful evening, is it not, sir?"

"Very beautiful. I have been on the beach for the last two hours. How well your carnations are doing, Salome. Ah, they always flourish best by the sea."

"Please let me give you some," the little girl said eagerly. "Oh, I don't mind picking them in the least. I should like you to have them." And moving about with agility on her crutches, she gathered some of the choicest blooms and presented them to Mr. Amyatt.

"Thank you, Salome. They are lovely. I have none to be compared to them in the Vicarage gardens. You are a born gardener. But what is amiss, child?"

"Nothing, sir; at least, nothing more than usual. I am anxious about father." She paused for a moment, a painful blush spreading over her face, then continued, "He spends more time than ever at the 'Crab and Cockle;' he's rarely home of an evening now, and when he returns, he's sometimes so—so violent! He used not to be that."

The Vicar looked grave and sorry, He pondered the situation in silence for a few minutes ere he responded, "You must have patience, Salome; and do not reproach him, my dear. Reproaches never do any good, and it's worse than useless remonstrating with a man who is not sober."

"But what can I do, sir?" she cried distressfully. "Oh, you cannot imagine what a trouble it is to me!"

"I think I can; but you must not lose heart. Prayer and patience work wonders. Ask God to show your father his sin in its true light—"

"I have asked Him so often," Salome interposed, "and father gets worse instead of better. It's not as though he had an unhappy home. Oh, Mr. Amyatt, it's so dreadful for me! I never have a moment's peace of mind unless I know father is out fishing. He isn't a bad father, he doesn't mean to be unkind; but when he's been drinking, he doesn't mind what he says or does."

"Poor child," said the Vicar softly, glancing at her with great compassion.

"Do you think, if you spoke to him—" Salome began in a hesitating manner.

"I have already done so several times; but though he listened to me respectfully, I saw my words made no impression on him. I will, however, try to find a favourable opportunity for remonstrating with him again. Cheer up, my dear child. You have a very heavy cross to bear, but you have not to carry it alone, you know. God will help you, if you will let Him."

"Yes," Salome agreed, her face brightening. "I try to remember that, but, though indeed I do love God, sometimes He seems so far away."

"He is ever near, Salome. 'The eternal God is thy refuge, and underneath are the everlasting arms.' The everlasting arms are of unfailing strength and tenderness. See! Is not that your father coming?"

Salome assented, and watched the approaching figure with anxious scrutiny.

Josiah Petherick was a tall, strong man, in the prime of life, a picture of robust health and strength; he was brown-haired and brown-eyed, like his daughter, and his complexion was tanned to a fine brick-red hue. He liked the Vicar, though he considered him rather too quick in interfering in other people's affairs, so he smiled good-humouredly when he found him with Salome at the garden gate.

"Good evening, Petherick," said Mr. Amyatt briskly, his keen eyes noticing that, though Josiah had doubtless been drinking, he was very far from being intoxicated at present; "you perceive I've been robbing your garden," and he held up the carnation blooms.

"'Tis my little maid's garden, sir," was the response, "an' I know well you're welcome to take what flowers you please. What a hot day it's been, to be sure!"

"Yes; but pleasanter out of doors than in the bar of the 'Crab and Cockle,' I expect," Mr. Amyatt answered meaningly.

"'Tis thirsty weather," Josiah said with a smile; "don't you find it so, sir?"

"Yes, indeed I do! But I don't take beer to quench my thirst. Beer's heating, and makes you hotter and thirstier, too. If you were a teetotaler like me, you wouldn't feel the heat quite so much."

"That's as it may be, sir. I can't argue the point; but I hold that a glass of good, sound beer don't hurt anyone."

Salome had retired into the cottage, remarking which fact, the Vicar seized the opportunity and spoke plainly.

"Look here, Petherick," he said, "if you'd lived my life, you'd be a teetotaler like me—at least, I hope you would. The big town in which I worked so long owed most of its vice and misery to drink. I was in daily contact there with men and women lower than brute beasts on account of the drink you uphold—men and women who would sell their own and their children's clothes, and allow their offspring to go hungry and almost naked, that they might obtain the vile poison for which they were bartering their immortal souls. I made up my mind there, that drink was our nation's greatest curse; and here, in this quiet village, I see no reason to make me change my opinion, and allow that a glass of 'good, sound beer,' as you call your favourite beverage, doesn't hurt anyone. Your one glass leads to more, and the result? You become unlike yourself, rough and threatening in your manner, unkind to your little daughter whom I am certain you dearly love, and whose chief aim in life is to make your home a happy one. I wish you would make up your mind, Petherick, never to enter the doors of the 'Crab and Cockle' again."

"Why, sir, to hear you talk one would think I was drunk," Josiah cried, aggrievedly.

"You are not that at this minute, I admit, but you have been drinking; and if you don't pull up in time, and turn over a new leaf, you'll go from bad to worse. Now, I've had my say, and have finished. Your supper's waiting, I know, so I'll bid you good evening."

"Good evening, sir," Josiah responded rather shamefacedly, for in his heart, he acknowledged every word Mr. Amyatt had spoken to be truth.

He watched the Vicar out of sight, then entered the cottage and sat down at the kitchen table to his supper of fried eggs and bacon.

"I hope the eggs are not spoilt," Salome remarked. "But they've been cooked nearly half-an-hour, and I'm afraid they're rather hard, for I had to keep them warm in the oven."

"Never mind, my dear," he returned. "If they're hard it's my fault, I ought to have been here before. By the way, I've brought you a piece of news."

"Have you, father?" she said with a smile.

"Yes. Greystone is taken by a rich gentleman from London, and he and his family are expected to arrive to-night. The house has been furnished in grand style, so I'm told."

"Did you hear the gentleman's name?" Salome asked, looking interested, for Greystone had been untenanted for some time. The house had been built by a speculative builder, but it had not proved a good speculation, as, beautifully situated though it was, it was very lonely. "I wonder if Mr. Amyatt knew," she added reflectively, as her father shook his head.

"Mr. Amyatt is a very nice man in his way," Josiah remarked, "an' I shall never forget how kind he was when your poor mother died, but he don't know how to mind his own business. If he likes to be a teetotaler, let him be one. If I enjoy my drops o' beer 'long with my friends at the 'Crab an' Cockle,' that's naught to do with him." And having finished his supper, he pushed away his plate, rose from the table, and strode out into the garden.

Salome stayed to wash up the supper things, then went into the garden too, but by that time her father was nowhere to be seen. Hurrying to the gate, she caught sight of his stalwart figure disappearing in the distance, and knew that he was making his way to the inn again. She stood leaning against the garden gate, sore at heart, until a chill mist from the sea crept upwards and surrounded her; then she retreated into the cottage and waited patiently, listening to the ticking of the tall, eight-day clock in the kitchen. She knew her father would not return till the doors of the inn were shut for the night.

At last she heard the click of the garden gate, and a minute later Josiah Petherick stumbled up the path, and, leaving the cottage door unlocked, crawled upstairs to his bedroom, muttering to himself as he went. Salome waited till everything was still, then she rose, locked the door, and swung herself, step by step, by the aid of her crutches, up the stairs.

Before going to her own room, she peeped cautiously into her father's, which was flooded with moonlight, the blind being up; and a sob broke from her lips at the sight which met her eyes. The man had thrown himself, fully dressed as he was, upon the bed, and had already sunk into a heavy, drunken slumber. Salome stood looking at him, the tears running down her cheeks, mingled love and indignation in her aching heart. Then the love overcame all else, and she sank on her knees by her father's side, and prayed earnestly for him who was unfit to pray for himself, whilst the words the Vicar had spoken to her that evening—

"'The eternal God is thy refuge,

and underneath are the everlasting arms.'"

—recurred to her memory, and fell like balm upon her sorrowful spirit. And she felt that she did not bear her trouble alone.

New Acquaintances.

WHEN Josiah Petherick came downstairs to breakfast on the following morning, his face wore a furtive, sullen expression, as though he expected to be taken to task for his behaviour of the night before. On previous occasions, Salome had, by tears and sorrowing words, reproached him for his unmanly conduct; but this morning she was perfectly composed, and the meal was eaten almost in silence. Afterwards, Josiah informed his little daughter that he should probably be away all day mackerel fishing, and went off in the direction of the beach. There was a fresh breeze blowing, and he looked forward to a successful day's work.

Salome moved about the cottage with a very heavy heart. On account of her affliction, it took her longer than it would have most people to get over her household duties, so that it was past noon before she had everything ship-shape, and was at leisure. Then she put on a pink sun-bonnet, and went into the garden to look at her flowers, pulling weeds here and there, until the sounds of shrill cries made her hurry to the garden gate to ascertain what was going on outside.

Salome stood gazing in astonishment at the scene which met her eyes. A boy of about six years old was lying on the ground, kicking and shrieking with passion, whilst a young woman was bending over him, trying to induce him to get up. At a short distance, a pretty little girl, apparently about Salome's own age, was looking on, and laughing, as though greatly amused.

"Gerald, get up! Do get up, there's a good boy!" implored the young woman. "Dear, dear, what a temper you're in. You 're simply ruining that nice new sailor's suit of yours, lying there in the dust. Oh, Margaret—" and she turned to the little girl—"do try to induce your brother to be reasonable."

"I couldn't do that, Miss Conway," was the laughing response, "for Gerald never was reasonable yet. Look at him now, his face crimson with passion. He's like a mad thing, and deserves to be whipped. He—"

She stopped suddenly, noticing Salome at the garden gate. The boy, catching sight of the lame girl at that moment too, abruptly ceased his cries, and, as though ashamed of himself, rose to his feet, and stood staring at her. He was a fine, handsome little fellow, with dark-blue eyes and fair curly hair; but, as Salome afterwards learnt, he was a spoilt child, and as disagreeable as spoilt children always are. His sister, who was like him in appearance, was a bright-looking little girl; and her laughing face softened into sympathy as her eyes rested on Salome's crutches.

"I am afraid my brother's naughty temper has shocked you," she said. "He likes to have his own way, and wanted to spend a longer time on the beach instead of going home. We have been on the beach all the morning with Miss Conway—this lady, who is our governess. What a pretty garden you have. We noticed it as we passed just now—didn't we, Miss Conway?"

Miss Conway assented, smiling very kindly at Salome.

"I had no idea flowers would flourish so close to the sea," she remarked. "It is to be hoped the Greystone gardens will prove equally productive."

"Oh, are you—do you live at Greystone?" Salome questioned, much interested in the strangers.

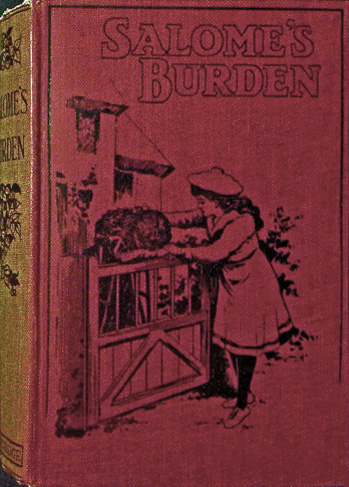

"Yes," nodded the little girl, "we arrived last night. My father, Mr. Fowler, has taken the house on a three years' lease. My mother is very delicate; she has been very ill, and the doctors say the north coast of Cornwall will suit her."

"Let me see your garden," said the little boy imperatively, coming close to the gate, and peering between the bars.

"You should say 'please,' Gerald," his governess reminded him reprovingly.

Salome invited them all to enter, and when they had admired the flowers, Miss Conway asked if she might rest a few minutes on the seat under the porch. She was a delicate-looking young woman, and the tussle she had had with her unruly pupil had upset her. Gerald, however, was quite contented now, watching a bee labouring from flower to flower with its load of honey. His sister, Margaret, sat down by the governess' side, whilst Salome, leaning on her crutches, watched them shyly. There was a little flush of excitement on her cheeks, for it was an unusual experience for her to converse with strangers.

"Who lives here with you, my dear?" Miss Conway inquired.

"Only my father, miss. Mother died five years ago. Father's a fisherman; his name's Josiah Petherick, and I'm called Salome."

"What a quaint, pretty name," Margaret exclaimed. "And you have you no sisters or brothers?"

Salome shook her head.

"Have you—have you always been lame?" Miss Conway questioned.

"Yes, miss, always. I can't get about without my crutches."

"How dreadful!" Margaret cried with ready sympathy. "Oh, I am, sorry for you."

Salome looked gratefully at the speaker, and smiled as she made answer, "You see, miss, I'm accustomed to being a cripple. Often and often I've wished my legs were straight and strong like other people's, but as they are not, I must just make the best of them. Mr. Amyatt says—"

"Who is Mr. Amyatt?" Miss Conway interposed.

"Our Vicar, miss. He lives in that big house near the church. He's such a good, kind gentleman, you'll be sure to like him."

"Well, what does he say?" Miss Conway inquired with a smile.

"That God made me lame for some good purpose. I think myself He did it because I should stay at home, and keep house for father," Salome said simply. "Perhaps if I was able to get about like other people, I might neglect father, and be tempted—"

She had been about to say "be tempted to leave him," but had stopped suddenly, remembering that the strangers knew nothing of her father; and she earnestly hoped they would never understand how miserable he made her at times.

"As it is," she proceeded, "I do all the housework—I can take as long as I please about it, you know—and I attend to my flowers besides."

"And have you always lived here?" Margaret asked.

"Yes, miss, I was born in this cottage."

"Doesn't the sea make you mournful in the winter?"

"Oh, no! It's grand then, sometimes. The waves look like great mountains of foam. This is a very wild coast."

"So I have heard," Miss Conway replied. "I should like to see a storm, if no ship was in danger. I suppose you never saw a wreck?"

"Yes," said Salome with a shudder; "only last autumn a coasting vessel ran ashore on the rocks, and the crew was lost. You will notice in the churchyard many graves of people who have been drowned."

"We have always lived in London until now," Margaret explained, "so we shall find life in the country a great change. I don't know that I shall dislike it during the summer, and Gerald is simply delighted with the beach; I expect he'll insist on going there every day, so you'll often see us passing here. Gerald generally gets his own way, doesn't he, Miss Conway?"

"Yes," the governess admitted gravely, looking rather serious.

"My mother spoils him," Margaret continued. "Oh, you needn't look at me like that, Miss Conway, for you know it's true."

At that moment Gerald ran up to them. He was in high good-humour, for he was charmed with Salome's garden; but his face clouded immediately when Miss Conway remarked it was time for them to go home.

"No, no," he pouted, "don't go yet, Miss Conway. Stay a little longer."

"But if we do, we shall be late for luncheon, and then your father will be displeased."

"You shall have this rose to take home with you," Salome said, in order to propitiate the child, and prevent a disturbance. She gathered, as she spoke, a beautiful pink moss-rose, and offered it to him. "Wouldn't you like to give it to your mother?" she suggested, as he accepted her gift with evident pleasure.

"No," Gerald rejoined, "I shan't give it to mother, I shall keep it for myself."

His sister laughed at this selfish speech; but the governess' face saddened as she took her younger pupil by the hand, and after a kind good-bye to Salome, led him away.

"May I come and see you again?" Margaret asked as she lingered at the gate.

"Oh, please do, miss," was the eager reply. "I should be so glad if you would. I really am very lonely sometimes."

"So am I," the other little girl confessed with a sigh; and for the first time Salome noticed a look of discontent on her pretty face. The expression was gone in a minute, however, and with a smiling farewell Margaret Fowler hastened after her governess and Gerald.

These new acquaintances gave Salome plenty of food for thought; and when her father returned in the afternoon she greeted him cheerfully, and told him that the family had arrived at Greystone. He was in good spirits, having caught a nice lot of mackerel; and acting on his daughter's suggestion, he selected some of the finest, and started for Greystone to see if he could not sell them there. Meanwhile, Salome laid the tea cloth, and got the kettle boiling. In the course of half-an-hour her father returned, having sold his fish.

"I saw the cook," he informed Salome, "and she said any time I have choice fish to sell, she can do business with me. It seems she manages everything in the kitchen; she told me the mistress doesn't know what there's to be for dinner till it's brought to table."

"How strange!" Salome cried. "But I forgot, Mrs. Fowler has been ill, so perhaps she is too great an invalid to attend to anything herself."

"I don't know about that, I'm sure. It's likely to be better for us, Salome, now Greystone is occupied. Why, you're quite a business woman, my dear! I should never have thought of taking those mackerel up there, but for you. I should have let Sam Putt have the lot, as usual."

Sam Putt was the owner of a pony and cart. He lived in the village, and often purchased fish, which he conveyed to a neighbouring town for sale, hawking it from door to door.

Josiah continued to converse amicably during tea-time; and afterwards he went into the garden, and turned up a patch of ground in readiness for the reception of winter greens. To Salome's intense relief, he did not go to the "Crab and Cockle" that evening; but, instead, as soon as he had finished his gardening, suggested taking her for a sail.

"Oh, father, how delightful!" she cried, her face flushing with pleasure. "Oh, I haven't been on the water for weeks! It will be such a treat!"

So father and daughter spent the long summer evening on the sea, much to the contentment of both; and the sun had set before they returned to Yelton.

Salome chatted merrily as, their boat safely moored, she followed her father up the shingly beach; but on reaching their garden gate, Josiah paused, glancing towards the swinging sign-board outside the "Crab and Cockle," still visible in the gathering dusk.

In a moment, Salome read his thoughts, and cried involuntarily, "Oh, father, not to-night! Not to-night!"

"What do you mean, child?" he asked with a decided show of displeasure in face and tone.

"I mean, I want you to stay at home with me to-night, father! Do, dear father, to please me! I—I can't bear to see you as—as you are sometimes when you come back from the 'Crab and Cockle'! Oh, father, if you would only give up the drink how happy we should be!"

"How foolishly you talk!" he cried irritably. "It is not seemly for a child to dictate to her father!"

"Oh, father, I mean no harm! You know I love you dearly! It's supper time. Aren't you hungry? I'm sure I am."

Josiah admitted he was, too, and followed his daughter into the cottage. He did not leave it again that night, for his good angel proved too strong for him; and when he kissed his little daughter at bedtime, his manner was unusually gentle, whilst the words he uttered sent her to rest with a very happy heart: "God bless you, child! I don't know what I should be but for you, Salome. You grow more like your dear mother every day you live."

The Fowlers at Home.

"PULL down the blind, Margaret. The sun is streaming right into my eyes."

The speaker, Mrs. Fowler, was lying on a sofa in the handsomely furnished drawing-room at Greystone. She was a young-looking, very pretty woman, with fair hair and blue eyes; and she was most fashionably dressed. One would have thought her possessed of everything that heart could desire, but the lines of her face were discontented ones, and the tone of her voice was decidedly fretful. The only occupant of the room besides herself was her little daughter, who put down the book she had been reading, and going to the window, obediently lowered the blind.

"There," she said, "that's better, isn't it? I won't pull the blind down altogether, mother, for that would keep out the fresh air, and you know the doctors said the sea breeze would be your best tonic. I do think this is a lovely place, don't you?"

Mrs. Fowler agreed indifferently; and her little daughter continued, "Such a beautiful view we have right over the sea. And doesn't the village look pretty, and the old grey church? There are such a quantity of jackdaws in the tower. Mother, do you know, from my bedroom window, I can see the cottage where that poor lame girl lives? When you are strong enough, I'll take you to visit Salome."

"I don't want to see her, Margaret. I don't like looking at deformed people, and I cannot think why you should feel so much interest in this Salome."

"I have seen her several times now, and I like her so much. The Vicar has told me a lot about her, too. She lost her mother five years ago, poor girl!"

Margaret paused, and glanced a trifle wistfully at the daintily-clad figure on the sofa, wondering if she was lame like Salome, whether her mother would cease to care for her altogether. Mrs. Fowler never evinced much affection for her daughter, whatever her feelings may have been, though she was pleased that she was growing up a pretty little girl, and took an interest in dressing her becomingly. But Gerald was her favourite of the two children, and upon him she lavished most of her love. She was fond of her husband, though she stood in awe of him. He was kind and attentive to her, but often grew impatient at the persistent way in which she indulged their little son.

Mrs. Fowler had led a gay life in London for many years; but latterly, she had been in very indifferent health, and after an attack of severe illness, which had left her nerves in a shattered condition, Mr. Fowler had insisted on shutting up their house in town, and settling in the country. He had accordingly taken Greystone, and dismissing their old servants had engaged new ones, who received their orders from himself instead of from their mistress.

During the first few weeks of her residence at Greystone, Mrs. Fowler had indeed been too ill to superintend the household; and though she was now better, she was far from strong, and was glad not to be troubled about anything. Margaret was very sorry for her mother, whose sufferings were apparent to everyone, for she started at the slightest unexpected sound, and the least worry brought on the most distressing headache.

"Would you like me to read to you, mother?" the little girl inquired.

"No, thank you, Margaret. What is the time?"

"Half-past three."

"Where is Gerald?"

"Miss Conway has taken him down to the beach; she promised him this morning he should go, if he was good and attentive during lesson time. He likes talking to the fishermen."

"Dear child! I hope they will not teach him to use bad language, though I expect they are a rough set."

"I don't think so, mother. Mr. Amyatt says they are mostly sober, God-fearing men; of course, there are exceptions—Salome Petherick's father, for instance, often gets intoxicated, and it is a terrible trouble to her."

"Does she complain of him to you?" Mrs. Fowler queried.

"Oh, no, mother! It was Mr. Amyatt who told me. We were talking of Salome, and he said her father was very violent at times, quite cruel to her, in fact. Do you know, I think father's right, and that it's best to have nothing whatever to do with drink."

Lately, since the Fowlers had left London, Mr. Fowler had laid down a rule that no intoxicating liquors of any description were to be brought into the house. He had become a teetotaler himself, for very good reasons, and had insisted on the members of his household following suit. No one had objected to this except Mrs. Fowler, and now she answered her little daughter in a tone of irritability.

"Don't talk nonsense, child! I believe a glass of wine would do me good at this minute, and steady my nerves, only your father won't allow it! I haven't patience to speak of this new fad of his without getting cross. There, don't look at me so reproachfully. Of course what your father does is right in your eyes! Here, feel my pulse, child, and you'll know what a wreck I am!"

Margaret complied, and laid her cool fingers on her mother's wrist. The pulse was weak and fluttering, and the little girl's heart filled with sympathy.

"Poor mother," she said tenderly, kissing Mrs. Fowler's flushed cheek, and noticing her eyes were full of tears. "Shall I ring and order tea? It's rather early, but no doubt a nice cup of tea would do you good."

"No, no! It's much too hot for tea!" And Mrs. Fowler made a gesture indicative of distaste, then broke into a flood of tears.

Margaret soothed her mother as best she could; and presently, much to her satisfaction, the invalid grew composed and fell asleep. She was subject to these hysterical outbursts, and as Margaret bent anxiously over her, she noted how thin she had become, how hectic was the flush on her cheeks, and how dark-rimmed were her eyes.

"She does indeed look very ill," the little girl thought sadly. "I wonder if she is right, and that some wine would do her good, and make her stronger; if so, it seems hard she should not have it. I'll go and speak to father at once."

To think was to act with Margaret. She stole noiselessly out of the drawing-room, and went in search of her father. He was not in the house, but a servant informed her he was in the garden, and there she found him, reclining in a swing-chair, beneath the shade of a lilac tree. He threw aside the magazine he was reading as she approached, and greeted her with a welcoming smile.

Mr. Fowler was a tall, dark man, several years older than his wife; his face was a strong one, and determined in expression, but his keen, deep-set eyes were wont to look kindly, and he certainly had the appearance of a person to be trusted.

"Is anything wrong, my dear?" he inquired quickly, noticing that she looked depressed. "Where is your mother?"

"Asleep in the drawing-room, father. She has had one of her crying fits again, and that exhausted her, I think. She seems very poorly, and low-spirited, doesn't she?"

"Yes; but she is better—decidedly better than she was a few weeks ago. I have every hope that, ere many months have passed, she will be quite well again. There is no cause for you to look so anxious, child."

"But she is so weak and nervous!" Margaret cried distressfully. "I was wondering if she had some wine—"

The little girl paused, startled by the look of anger which flashed across her father's face. He made a movement as though to rise from the chair, then changed his intention, and curtly bade her finish what she had been about to say.

"It was only that I was wondering if she had some wine, whether it might not do her good," Margaret proceeded timidly. "She told me herself she thought it would, and if so—you know, father, you used to take wine yourself, and—"

"Did your mother send you to me on this mission?" he interrupted sternly.

"No. I came of my own accord."

"I am glad to hear that. But I cannot give my consent to your mother's taking wine, or stimulants of any kind; they would be harmful for her, the doctors agree upon that point. You have reminded me that I once drank wine myself, Margaret. I bitterly regret ever having done so."

"Why?" she asked wonderingly, impressed by the solemnity of his tone. Then her thoughts flew to Salome Petherick's father, and she cried, "But, father, you never drank too much!"

"I was never tempted to drink to excess, for I had no craving for stimulants. It is small credit to me that I was always a sober man; but people are differently constituted, and my example may have caused others to contract habits of intemperance. The Vicar here is a teetotaler from principle. He tells me that the force of example is stronger than any amount of preaching. Lately, I have had cause to consider this matter very seriously, and I am determined that never, with my permission, shall any intoxicating liquors be brought inside my doors. The servants understand this: I should instantly dismiss one who set my rule at defiance. As to your mother—" he paused a moment in hesitation, the expression of his countenance troubled, then continued—"she is weak, and still very far from well, but, in her heart of hearts, she knows I am right. Do not tell her you have broached this subject to me. Come, let us go and see if she is still asleep."

"You are not angry with me, father?" Margaret asked, as she followed him into the house.

"No, no! I am not, indeed!"

Mrs. Fowler awoke with a start as her husband and little daughter entered the drawing-room. Mr. Fowler immediately rang for tea, and when it was brought, Margaret poured it out. At first, Mrs. Fowler would not touch it, but finally, to please the others, drank a cupful, and felt refreshed. A few minutes later, Mr. Amyatt was shown into the room, and she brightened up and grew quite animated. Margaret and her father exchanged pleased glances, delighted at the interest the invalid was evincing in the conversation.

"I think I shall soon be well enough to go to church on Sundays," Mrs. Fowler informed the Vicar. "My husband tells me you have a very good choir."

"Yes, that is so," Mr. Amyatt replied. "We are decidedly primitive in our ways at Yelton, and have several women in our choir, notably Salome Petherick, the lame girl with whom your daughter has already become acquainted."

"Oh, yes. Margaret has been telling me about her. She sings in the choir, does she?"

"Yes. She has a beautiful voice, as clear and fresh as a bird's! I train the choir myself, for our organist comes from N—, a neighbouring town, several miles distant."

"By the way," said Mrs. Fowler with a smiling glance at Margaret, "my little girl is very desirous of learning to play the organ, and her governess would teach her, if you would allow her to practise on the organ in the church. Would there be any objection to that plan, Mr. Amyatt?"

"None whatever," was the prompt reply.

"Oh, thank you!" Margaret cried delightedly.

"You will have to employ Gerald to blow for you," Mr. Fowler remarked with a smile.

"I am sure he will not do that!" the little girl exclaimed. "He is far too disobliging."

"Margaret, how hard you are on your brother," Mrs. Fowler said reproachfully.

"Am I? I don't mean to be. Oh, here he is!"

Gerald came into the room with his hat on his head, but meeting his father's eyes, removed it instantly. After he had shaken hands with the Vicar, his mother called him to her, pushed back his fair locks from his forehead, and made him sit by her side on the sofa whilst she plied him with sweet cakes. He was her darling, and she indulged him to his bent. When the governess entered the room, having removed her hat and gloves, there were no sweet cakes left. Mr. Fowler rang the bell for more, and upon the parlour-maid bringing a fresh supply, declined to allow Gerald to partake of them, at which the spoilt boy pouted and sulked, and his mother threw reproachful glances at her husband.

Mr. Amyatt watched the scene in silence, wondering how anyone could allow affection to overcome judgment, as Mrs. Fowler had evidently done, as far as her little son was concerned, and marvelling that Mr. Fowler did not order the disagreeable child out of the room. When the Vicar rose to go, his host accompanied him as far as the garden gate, and they stood there talking some while before, at last, the Vicar said good-bye, and started down the hill towards the village.

The Fowlers had now been several weeks in residence at Greystone, but, up to the present, Mr. Amyatt had been their only visitor. Mrs. Fowler had not been outside the grounds surrounding the house yet, but talked of going down to the beach the first day she felt strong enough to attempt the walk. The children, however, had made several acquaintances among the fisher-folk, and a great liking had sprung up between Margaret and Salome Petherick, for, though one was a rich man's daughter and the other only a poor fisherman's child, they found they had much in common, and, wide apart though they were to outward appearances, they bade fair to become real friends.

"Abide with Me."

THE Fowlers had been six weeks at Greystone, when, one evening towards the end of July, Mrs. Fowler, who was daily improving in health, accompanied Margaret and Miss Conway to the church, and wandered about the ancient building, reading the inscriptions on the monuments, whilst her little daughter had her music lesson. By-and-by she strolled into the graveyard, and, seating herself on the low wall which surrounded it, gazed far out over the blue expanse of ocean, which was dotted with fishing boats and larger crafts, on this calm summer evening.

The churchyard at Yelton was beautifully situated, commanding a view of the whole village straggling nearly down to the beach, whilst on the eminence beyond the church was Greystone, against a background of green foliage.

"Everything is very lovely," Mrs. Fowler said to herself, "and the air is certainly most invigorating. I feel almost well to-night. Who comes here? Why, this must be Salome Petherick!"

It was the lame girl who had entered the churchyard, and was now approaching the spot where Mrs. Fowler sat. She paused at the sight of the figure on the wall, and a look of admiration stole into her soft, brown eyes. She had never seen such a pretty lady before, or anyone so daintily and becomingly dressed.

Mrs. Fowler, who had shrunk with the nervous unreasonableness of a sick person from being brought into contact with the cripple girl, now that she was actually face to face with her, was interested and sympathetic at once. She smiled at Salome and addressed her cordially.

"I think you must be Salome Petherick?" she said. "Yes, I am sure you are!"

"Yes, ma'am," was the reply, accompanied by a shy glance of pleasure.

"My little girl has spoken of you so often that I seem to know you quite well," Mrs. Fowler remarked. "Come and sit down on the wall by my side, I want to talk to you."

Then as Salome complied willingly, she continued, "Does it not tire you to climb here every evening, as they tell me you do, to listen to the organ? The church is a good step from where you live. That is your home, is it not?" and she indicated the cottage nearest to the sea.

"Yes," Salome assented, "it does tire me a little to come up the hill, but I love to hear music. After Miss Margaret has had her organ lesson, Miss Conway generally plays something herself."

"Does she? Then I hope she will do so to-night. But my little daughter is still at the organ, so we will remain where we are until she has finished. Meanwhile we will talk. They tell me you live with your father, and that he is often away fishing. You must lead a lonely life."

"Yes, ma'am, indeed it is very lonely sometimes," Salome acknowledged, "but I don't mind that much. I have plenty to do, keeping the cottage clean and tidy, and preparing father's meals, mending his clothes, and seeing to the flowers in the garden."

"How busy you must be. And you have lost your mother, poor child."

Salome pointed to a green mound at a little distance, whilst her brown eyes filled with tears.

"She was such a good mother," she said softly, "oh, such a very good mother! And I was such a fretful, tiresome child. I used to grieve her so often, and I can't bear to think of it now."

She paused, but, encouraged by the sympathy on her companion's face, she continued, "She used to be so patient with me when I was naughty and grumbled because I was not able to run about and play like other children. And, until she lay dying, I never thought how sorry I must have made her, and what a selfish girl I'd been. Then, I would have given anything if I'd been different, but it was too late." And the repentant tears streamed down Salome's cheeks.

"Don't grieve," said Mrs. Fowler, a little huskily, for she was much touched at the other's evident remorse.

"I am sure Miss Margaret never treated you, ma'am, as I used to treat my mother!" Salome exclaimed.

Mrs. Fowler was silent as she acknowledged to herself that Margaret had always been patient and considerate when she had been an exacting invalid.

"I suppose your father is out in his fishing boat?" she asked by way of changing the conversation.

"No, ma'am," Salome replied, the look of grief deepening on her face.

"Let us go into the church and hear Miss Conway play," Mrs. Fowler said, rising as she spoke. "I hear Margaret's lesson is at an end. Ah, here comes the Vicar. How do you do, Mr. Amyatt?"

"I am glad to see you are better, Mrs. Fowler," the Vicar exclaimed. "What, you here, Salome? Don't go away; I want Mrs. Fowler to hear you sing."

Salome smiled, and blushed. She followed the others into the church and seated herself in a pew near the door, whilst the Vicar pointed out beauties in the architecture of the building to his companion, which she had failed to notice. Miss Conway was at the organ, playing "The Heavens are telling," and when the last notes died away the Vicar beckoned to Salome, who swung herself up the aisle on her crutches, and, at his request, consented to sing.

"I will play the accompaniment," Miss Conway said, smiling encouragingly at the lame girl, who felt a little shy at being called upon to sing alone. "What shall it be?" she inquired.

"Whatever you please, miss," Salome answered.

"Oh, no! You must choose," the Vicar declared decidedly.

"Then I will sing 'Abide with Me.'"

Mrs. Fowler and Margaret considerately withdrew to a side seat so that the sight of them should not embarrass the singer, and Mr. Amyatt followed them. Salome stood a little behind Miss Conway, who softly played the accompaniment of the hymn:

"Abide with me; fast falls the eventide;

The darkness deepens; Lord, with me abide;

When other helpers fail, and comforts flee,

Help of the helpless, O abide with me."

Salome's fresh, sweet voice rang clearly through the dim church, and its tender tones touched the hearts of her audience. She was very fond of "Abide with Me," for it had been her mother's favourite hymn, and to-night she sang her best.

"Heaven's morning breaks, and earth's vain shadows flee;

In life, in death, O Lord, abide with me."

The beautiful voice died lingeringly away, and for a few minutes there was a complete silence. Then Mrs. Fowler rose, and coming eagerly forward, took Salome by the hand, whilst she thanked her for giving her such a "rare treat" as she called it.

Margaret was delighted to see what a favourable impression her lame friend had evidently made upon her mother, and great was her surprise when, on their all adjourning to the churchyard, Mrs. Fowler asked Salome to come and see them at Greystone.

"I think you would be able to get as far as that, don't you?" she said with a winning smile. "I should like you to come and sing to me. Will you, one evening?"

"Oh, yes," Salome replied. She had never been inside the doors of Greystone in her life, though she had often desired to see what the house was like, having been told it was a fine place.

"Then that is settled. I shall expect you."

Mrs. Fowler nodded and turned away, followed by Miss Conway, and Margaret who looked back to wave her hand in farewell as she disappeared through the churchyard gate. The Vicar accompanied them thus far, then turned back to speak a few words to Salome. The village lad who had been employed to blow the organ had taken a short cut homewards over the low wall.

"You sang remarkably well to-night," Mr. Amyatt said, "I felt quite proud of my pupil. You showed excellent taste, too, in the hymn you chose. It was most suitable for the occasion. I wonder if you know the circumstances under which that hymn came to be written?"

"No," Salome rejoined, shaking her head, "I don't know, sir."

"Then I will tell you. It was composed more than fifty years ago by a sick clergyman of the name of Lyte, at a little fishing town called Brixham, in South Devon. He had become so seriously ill that the doctors had ordered him abroad for his health's sake, and, after service on the Sunday evening, prior to his leaving England, he went down to the sea-shore, sad at heart, for he was convinced that he had spoken to his parishioners, who were very dear to him, for the last time. He was sorrowful and low-spirited, but, by-and-by, the remembrance that his Saviour was ever near to help and sustain him brought him consolation. After watching the sunset, he went home, and immediately wrote the beautiful hymn you sang to-night."

Salome had listened with deep interest, and she exclaimed earnestly: "Oh, Mr. Amyatt, I am glad you have told me this. I shall love 'Abide with Me' better than ever now."

The Vicar smiled, then pointed towards the sea, over which a soft summer mist was creeping.

"It is time for you to go home," he reminded her. "Where is your father this evening?"

"At the 'Crab and Cockle,' sir."

He shook his head sadly, but refrained from questioning her further. He saw she was thinner than she had been a few months previously, and wondered if she was sufficiently well fed, or if Josiah Petherick expended the money he should have spent on his home, on the friends he met at the inn. As he watched the little girl swinging herself slowly down the hill by the aid of her crutches, he felt very grieved and troubled on her account.

"What a curse this drink is!" he thought. "And it's a curse that creeps in everywhere, too."

In the village that afternoon, he had been told that Mr. Fowler had summarily dismissed a groom who had been discovered with a bottle of beer in the stable, and he had listened to various comments upon the strict notions of the master of Greystone. Most of the villagers were inclined to think that the man's fault in disobeying his master's rule that no intoxicating liquor should be brought on the premises might have been overlooked, as it was his first offence, whilst some few argued that Mr. Fowler had acted rightly.

As Salome passed the "Crab and Cockle" on her way home, she heard sounds of hilarity within, and recognised her father's voice singing a rollicking sea song. She sighed, remembering how, during his wife's lifetime, Josiah had been a member of the church choir; it appeared unseemly to her that a voice which once had been raised to the praise and glory of God should lend itself to the entertainment of a set of half-drunken men in the bar of a public-house. As she paused, involuntarily listening, a whiff of foul air, laden with the mingled odour of smoke and beer, was wafted before her nostrils from the open doorway, and she moved on with a sickening sense of shame and disgust, her heart heavy as lead, her eyes smarting with tears. Oh, hers was a hard life, she thought bitterly.

Arrived at home, she laid a frugal supper of bread and cheese, and soon afterwards her father reeled up the garden path and into the kitchen. Sitting down at the table, he helped himself to bread and cheese in silence, and commenced eating, whilst his little daughter took her accustomed place opposite to him.

"Where've you been?" he questioned. "I saw you pass the inn."

She told him how she had spent the evening, explaining that she had sung at the Vicar's request, and that Mrs. Fowler had invited her to Greystone.

"I won't let you go there!" he cried. "I hate those new people! What did Mr. Fowler do yesterday, but dismiss as honest a chap as ever lived, at a moment's notice, just because he'd got a bottle o' beer in the stable! An' the man wasn't drunk either! No, you shan't go nigh folks as treats their servants like that."

"Oh, father!" Salome exclaimed, disappointedly. She was wise enough, however, not to pursue the subject. After a brief silence, she asked, with some timidity, "Father, have you any money? Because, when Silas Moyle left the bread this afternoon, he said he couldn't supply us with any more unless you paid him what you owe."

Silas Moyle was the one baker of the place, and the owner of the village shop, in which his wife served. Josiah Petherick had formerly paid ready money for everything, but latterly he had been spending at the "Crab and Cockle" what should have gone into Silas Moyle's pocket. This was an additional trouble to Salome, but her father did not appear to care. He was enraged, though, when he heard what the baker had said, and, as his creditor was not present to bear the brunt of his indignation, Salome had to stand it instead. She turned white when he swore at her, and sat perfectly still whilst he abused her roundly, but when he called her extravagant she began to protest.

"Father, that's not fair of you! I'm as careful as ever I can be. We're obliged to have bread! Won't you see Silas yourself? Perhaps he'll continue to supply us, if you can arrange to pay him part of what we owe. Of course, he wants his money."

"He's another of your teetotal humbugs!" sneered the angry man.

"He isn't a humbug at all!" Salome retorted hotly, her indignation and sense of justice overcoming her fear of her father; "but he did say he wasn't minded to wait for his money when it was being squandered with that drunken crew at the 'Crab and Cockle.' Oh, father, it was terrible for me to hear that, and I couldn't contradict him!"

With a fierce oath, Josiah pushed back his chair and rose from the table, declaring things had come to a pretty pass when his own daughter, a mere child, thought fit to discuss him with outsiders.

Salome broke into passionate weeping at this, whereupon he flung himself out of the kitchen, and the next minute she heard his footsteps in the garden.

"He's gone to the 'Crab and Cockle' again," thought the unhappy little girl. "Oh, how could he swear at me like that? Oh, how shall I bear it!" Presently she arose, put away the supper things and then sat down by the open window to wait, as she knew she would have to do, until the inn door was closed for the night, and her father would return. By-and-by, the soft lap, lap of the sea had a soothing effect upon her troubled spirit, the peacefulness of the summer night stole into her soul, and she murmured to herself the words of consolation she had sung an hour or so before in the dim, old church:

"When other helpers fail, and comforts flee,

Help of the helpless, O abide with me."

Salome's Humiliation.

JOSIAH PETHERICK sat on the beach mending his fishing nets in the shade of a tall rock. It was intensely hot, and there was scarcely a ripple on the glassy sea, whilst the sky was a broad canopy of blue. Josiah was thinking deeply. That morning, consequent on the information his daughter had given him on the previous evening, he had been to interview Silas Moyle, and had induced the baker to allow him further credit. Never in his life before had Josiah found himself in such a humiliating position, and he felt it all the more because it was entirely his own fault. He had always prided himself on being able to pay his way, and now he was not in the position to do so.

Glancing up from his work presently, the fisherman saw three figures come down to the beach—a lady, a gentleman, and a small boy clad in a sailor's suit and broad-brimmed straw hat. He knew them to be Mr. and Mrs. Fowler and their little son. He had often held lengthy conversations with Gerald, who was always delighted to talk with anyone who could tell him about the manifold wonders of the sea, but he had never spoken to either of the boy's parents. Despite his disapproval of the strict teetotal principles of the master of Greystone, he regarded that gentleman with considerable interest, and when Mr. Fowler strolled up to him, and inquired from whom a boat might be hired, he answered him civilly, "You can have a boat from me, if you like, sir; but there's no wind for sailing to-day."

"Perhaps you would row us around those high rocks yonder. My wife has a fancy to see what lies beyond that point."

Josiah assented willingly, seeing an opportunity of earning a few shillings; and so it came to pass that he spent a very pleasant and lucrative morning, returning home to dinner in the best of spirits.

"The new folks at Greystone have a liking for boating," he informed Salome; "and see here," tossing a half-crown as he spoke upon the table, "give that to Silas Moyle when he calls with the bread this afternoon."

The lame girl's face brightened as she took up the coin, and looked at her father questioningly.

"I saw Mr. and Mrs. Fowler and Master Gerald pass here on their way to the beach," she said. "Did you take them out in your boat, father?"

"Yes. They treated me very fairly, I must admit that, an' Mrs. Fowler—she seems a nice lady—spoke of you."

"Did she?"

"She said you had a lovely voice, an' that she was looking forward to hear you sing again. I say, Salome, I shouldn't like to disappoint her, so if she really wants you to go and see her, you may—" and Josiah, mindful of all he had said on the preceding night, avoided meeting his little daughter's eyes as he made this concession.

"Oh, thank you, dear father," she cried. "I should like to go to Greystone so much."

"That little Master Gerald is a tiresome monkey," Josiah remarked. "He wouldn't sit still in the boat at first, though his mother kept on with him. At last his father spoke, an' after that, there was no need to tell him to be quiet again. Mr. Fowler looks a man as would have his own way."

"Master Gerald is very disobedient, I know," Salome said, "and sometimes his governess has great trouble with him. Miss Margaret says her mother spoils him."

"Then, 'tis a good job he's got a father who doesn't."

After dinner, Josiah went on with his interrupted work of mending his fishing nets, whilst Salome tidied up the cottage and waited for Silas Moyle.

The baker looked gratified as he took the half-crown the lame girl tendered him, for he had not expected to be paid even a small part of his account.

"That's right," he said, as he pocketed the money; "it appears I did some good by speaking yesterday. Look here, my dear, you must try to keep that father of yours up to the mark. Can't you make him stay at home of an evening?"

The little girl shook her head, and looked distressed as she replied, "I'm afraid not, Mr. Moyle."

"He's not at the 'Crab and Cockle' now, I s'pose?"

"No, he's on the beach mending his nets; and this morning he took Mr. and Mrs. Fowler and their little boy for a row in his boat."

"It's a pity Mr. Fowler can't get your father to his way of thinking—about drink, I mean. I say the new folks at Greystone set an example that many in Yelton might follow with advantage. Theirs is a teetotal household, I'm told."

"So I've heard," Salome responded.

Silas Moyle nodded kindly, and took himself off, whilst Salome locked up the cottage and joined her father on the beach. She told him the baker had been pleased to receive the half-crown, and then tactfully changed the subject. Josiah and his daughter were always excellent friends when the former had not been drinking.

"Look!" Salome exclaimed suddenly, "There's Master Gerald. Why, he seems to be alone. He sees us."

The child came running towards them, laughing as he stumbled over the rough shingles, his face aglow with excitement, his broad-brimmed sailor's hat at the back of his head, revealing the fair curls which clustered thickly around his brow.

"I've run away," he cried merrily. "I wanted Miss Conway to bring me down to the beach, but she would not—the disagreeable thing! She said it was too hot, and I must stay in the garden. So I came by myself."

"Doesn't Miss Conway know where you are?" Salome inquired.

"No one knows," he replied proudly. "I can take care of myself."

"I'm not so sure of that, young gentleman," Josiah remarked, with a chuckle of amusement at Gerald's air of importance.

"It was naughty of you to run away," Salome told him in a tone of reproof.

The child made a grimace at her, and ran off towards some rocks which the receding tide had left uncovered.

"He's a pretty handful," Josiah exclaimed, shaking his head.

"I expect someone will be here looking for him soon," said Salome. "I hope so, for his mother will be anxious if she does not know where he is, and she is not strong."

But nobody came in search of Gerald, who at last disappeared from sight beyond the rocks. In spite of her father's assurance that the boy could come to no harm, the little girl grew uneasy about him; and, by-and-by, rose and went to make certain he was safe. She found him lying flat on the wet beach, gazing into a pool between two rocks at some beautiful anemones; and tried to induce him to retrace his footsteps, but all to no purpose. In vain she told him that his mother would be worried about him, and that his father would be angry. The wayward child would pay no attention to her.

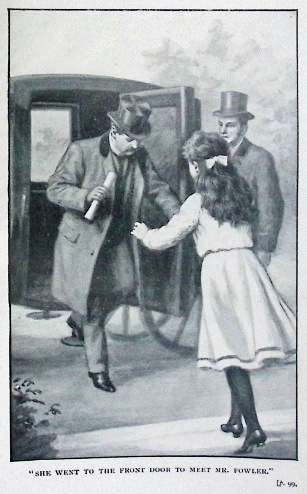

"What's it to do with you?" he demanded rudely. "Mind your own business, if you please."

As he absolutely refused to return, Salome left him with the intention of persuading her father to interfere; but, to her dismay, she found Josiah had deserted his nets, and as the key of the cottage door was in her pocket, she knew he had not gone home. In all probability he had betaken himself to the "Crab and Cockle" to obtain a drink. Whilst she was hesitating how to act, much to her surprise, Gerald appeared around the rocks and joined her. He was tired of the beach, he declared, and wanted to see her flowers, so she allowed him to accompany her home. And thus it was that the young tyrant was discovered in Salome's garden half-an-hour later by his much-tried governess.

Poor Miss Conway! She almost wept with joy on finding Gerald in safety, and insisted on his return to Greystone immediately. She led him away in triumph, paying no attention to his request that he might be allowed to remain a little longer.

Josiah did not return for his tea, so after waiting some time, Salome had hers, and then seated herself under the porch with her knitting. There Margaret Fowler found her as the evening was drawing in.

"Mother has sent me to thank you for taking such good care of Gerald this afternoon," Margaret said as she complied with the lame girl's invitation to sit down opposite to her. "He is a very tiresome, disobedient boy, for father had told him never to go down on the beach by himself. He is not to be trusted. Father has punished him for his naughtiness by ordering him to bed. It was quite a shock to poor Miss Conway when she found Gerald was nowhere on the premises."

"I noticed she looked pale," Salome said. "I am afraid Master Gerald is very troublesome."

"Troublesome! I should think he is. It was kind of you to look after him, Salome. I have a message from my mother to know if you can come to see us to-morrow. Do try to come."

"Oh, I should like to!" Salome cried, her eyes sparkling with excitement.

"Then, will you manage to be at Greystone by five o'clock?"

"Yes, miss, if all's well. Oh, please thank Mrs. Fowler for asking me!"

"Mother wants to hear you sing again. She has taken quite a fancy to you, and I am so glad."

"I think your mother is the prettiest, sweetest lady I ever saw," the lame girl said earnestly. "How dearly you must love her, Miss Margaret."

"Yes," Margaret answered soberly, "but I do not think she cares for me much. Gerald is her favourite, you know. Oh, I'm not jealous of him, but I can't help seeing that though he teases and worries her, and I do all I can to please her, she loves him much better than she has ever loved me."

Salome was surprised, and pained by the look of sadness on her companion's face.

"Perhaps your mother shows her affection more to Master Gerald because he's so much younger than you," she suggested. "I cannot believe she loves him better really."

Margaret made no reply to this, but by-and-by she said, "We have had several fusses at home these last few days. Did you hear that father dismissed one of the men-servants for bringing beer into the stable?"

"Yes, I heard about it. I think Mr. Fowler was quite right," Salome declared decidedly.

"Do you? I'm glad to hear you say that. Father always means to do right, I am sure. He is a teetotaler himself, you know, and so are we all, for that matter."

At this point in the conversation the garden gate clicked, and Josiah strode up the path and hurried past the little girls into the cottage. His bronzed face was crimson; and he walked somewhat unsteadily; but he was sufficiently sober to realise that his wisest plan was to take no notice of his little daughter's visitor.

Pitying Salome from the depths of her heart, Margaret rose, saying it was time for her to go home. The lame girl followed her silently to the garden gate, where they stood for a few minutes talking.

"You'll be sure to come to-morrow, won't you?" Margaret said earnestly.

"Yes, miss," was the grave reply, "if I possibly can; I hope nothing will prevent it, but—you see how it is with him sometimes," and she pointed towards the cottage.

"Yes," Margaret admitted. "Oh, I'm so sorry! He must be a terrible trial for you. May God help you, Salome."

"He does help me," the lame girl replied, "I couldn't bear it alone. Oh, how I wish my father was a teetotaler like yours."

"I wish so, too."

"I had hoped you would never find out about my poor father being a drinker, but I might have known that sooner or later you would learn the truth. Oh, miss, don't, please don't think, he's altogether a bad man. He isn't! When he's sober, there's not a kinder or better man in the world. But when the drink gets hold of him, he isn't himself at all." And Salome laid her head on the top rail of the gate and sobbed heartbrokenly.

"Oh, don't cry so!" Margaret said imploringly, her own eyes full of tears. "Oh, perhaps he'll give up the drink some day."

"I don't know, miss, I'm afraid he won't. He gets worse instead of better. The Vicar has spoken to him, but that's done no good. He has only come home for supper now; afterwards he'll go back to the 'Crab and Cockle.' But there, I mustn't cry any more, or he'll notice it!"

SALOME LAID HER HEAD ON THE TOP RAIL OF THE GATE

AND SOBBED HEART-BROKENLY.

"Good-bye, Salome! Mind you come to-morrow."

"Oh, yes! I hope I shall. Oh, miss, I feel so ashamed that you should have seen my father to-night!"

"There's nothing for you to be ashamed about. I think you're the pluckiest girl I know. Good night!" And Margaret ran off with a nod and a smile.

She slackened her speed soon, however; and as she went up the hill beyond the church towards her home, paused now and again to look back the way she had come, and admire the beautiful view. At the entrance to the grounds of Greystone she met her father, and together they walked towards the house, whilst she told him of Josiah Petherick's condition that evening.

"Oh, father, you are right to be a teetotaler!" she cried. "Drink is an awful thing!"

"It is indeed, my dear," he replied with a deep sigh. "I found Petherick a well-informed, civil-spoken man, in fact I was favourably impressed with him this morning, and he talked of his little daughter as though he really loved her. Drink can slay affection, though," he concluded sorrowfully.

"It's dreadful it should, father!"

"When drink once gets hold of people, it makes them slaves, and kills their finest feelings. I am very sorry for that poor Salome!"

"So am I. She is so brave, too, and sticks up for her father all she can. Oh, I think he ought to give up the drink for her sake. I wonder—I wonder if it would be any good for you to speak to him!" And Margaret looked wistfully and pleadingly into her father's face.

"I will consider the matter," he rejoined thoughtfully.

"Oh, father!" she cried, picturing afresh Salome's grief and humiliation, "What should I do, if I had such a trouble as that poor lame girl has to bear?"

Mr. Fowler started, and a look of intense pain and trouble momentarily crossed his countenance, but he answered quietly, "In that case, I hope you would ask God to support and comfort you."

"As Salome does. I could not be patient like she is, though."

"I trust you would, my dear child."

"Well, I am not likely to be tried," and Margaret regarded her father with a look of affectionate pride. She wondered at the sadness of the smile with which he returned her glance; and his answer, gravely spoken, puzzled her not a little.

"We cannot tell how much our patience and our love may be tried," he said, "nor what trials the future may hold for us. We can only pray that God will help and strengthen us in our time of need."

Perfectly Happy.

"OH, I do hope she will come! It's nearly five o'clock, and she's not in sight yet. I wish I had thought of watching from my bedroom window, I could have seen then when she left the cottage."

The speaker, Margaret Fowler, started up from her seat beneath the lilac tree, and ran across the lawn in the direction of the gate which led from the grounds of Greystone into the road. Beneath the lilac tree sat Mrs. Fowler in a comfortably padded wicker chair, with a small table laden with papers and magazines at her side. She glanced after her little daughter with a slightly amused smile, then remonstrated with Gerald, who was playing near by, for making a noise.

"You will give me a headache, if you keep on doing that," she said, as he cannoned two croquet balls against each other. "Pray, be quiet!"

Gerald chose not to obey. He continued his game, utterly regardless of his mother's command.

"Do stop, Gerald!" she exclaimed. "I really cannot bear that noise any longer. Oh, where is Miss Conway? Why isn't she here to look after you? Gerald, to oblige me, find some other amusement, there's a dear boy!"

"Why do you not obey your mother, sir?" demanded a stern voice. And suddenly the little boy dropped the croquet-mallet from his hand, and turned to face his father.

"That's right, Gerald!" Mrs. Fowler said hastily. "He hasn't been doing anything wrong, Henry," she continued, glancing apprehensively at her husband, "only—you know how absurdly nervous I am—I can't bear any sharp, sudden noise. It's foolish of me, I know."

Gerald now ran after his sister, and Mr. Fowler stood with his hand on the back of his wife's chair, looking, down at her with grave attention.

"You should make the boy obey you, my dear," he said. "Has not your visitor arrived yet?"

"No. Margaret has gone to the gate to see if she is coming. I thought we would have tea out here, for it is cooler and pleasanter in the garden than in the house, and it will be more informal. I should like you to hear this lame girl sing, Henry! I think I never heard a voice which touched me so deeply as hers. But you are not listening—"

"I beg your pardon, my dear. I confess my thoughts were wandering. The fact is, to-morrow I shall have to go up to town for a few days, and I would far rather remain at home. But I am obliged to go."

"You can leave with an easy mind," his wife told him reassuringly. "I am really quite strong now, and capable of managing the household, I believe I shall be better for something to do. By the way, you cannot think how much I enjoyed my drive this morning to N—" mentioning the nearest town. "I wanted some trifles from a draper's, and the shops were much better than I expected. Oh! Here come the children. They are bringing Salome with them."

Mrs. Fowler rose and greeted the lame girl very cordially, placing her in a chair next to her own. Salome was looking her best, neatly attired in a clean cotton frock. There was a flush born of excitement on her cheeks, and her brown eyes shone with a happy light as she gave herself up to the enjoyment of the present hour.

Tea was served beneath the lilac tree, such a luxuriant tea as Salome had never partaken of before, and everyone appeared determined that she should make a good meal—Gerald pointing out to her the most delectable of the dainties which he pressed her to eat, for in the depths of his selfish little heart, there was a warm spot for the lame girl who had so often given him flowers from her garden when he had certainly not deserved them.

Salome was inclined to be a trifle shy at first of Mr. Fowler. From what she had heard of him she had imagined he must be an exceedingly stern, strict sort of man, but he talked to her so kindly and pleasantly that she soon grew at ease with him, and answered all the questions he put to her unreservedly. She told him she had only been a member of the choir during the last six months, and explained that she had not known she possessed a really good voice until the Vicar had informed her that such was the fact.

"I always loved singing, even when I was a tiny thing," she said, "but I never thought of joining the choir till one day when Mr. Amyatt suggested it. He was passing our cottage, and heard me singing, and he came right in and said he would like me to come up to the Vicarage and let him try my voice. Father said I might go, so I did, and the next Sunday, I sang with the choir in church for the first time."

"You must not sing too much," Mr. Fowler remarked, "for you are very young, and might permanently injure your voice if you strained it now. You must nurse it a bit."

"That's what Mr. Amyatt says," Salome replied with a smile, "and I'm very careful."

"It is a great gift to have a beautiful voice." Mr. Fowler looked with kindly interest at his little guest as he spoke; then his eyes wandered to the crutches which she had placed on the ground beside her chair, and she caught the swift glance of sympathy which crossed his face, and from that moment, he stood high in her estimation.

"God is very merciful," he added softly, as though speaking to himself; "we are too apt to forget that He never sends a cross without its compensation."

Salome was perfectly happy sitting there under the lilac tree, though she felt all the while as though she must be in a wonderful dream. Mrs. Fowler, in her light summer dress, with her fair hair and her lovely blue eyes, looked like a queen, she thought. Salome was more and more impressed with her grace and charm on every fresh occasion on which she saw her. How proud Miss Margaret must be of her mother! And how happy Miss Margaret must be in such a beautiful home, with kind parents, and everything that heart could desire! And yet, what was the meaning of that wistful look on her face; and why was Mr. Fowler's countenance so grave, and almost stern in expression at times? Salome's eyes were remarkably shrewd. She noticed how attentive Mr. Fowler was to his wife, almost seeming to anticipate her wishes and read her thoughts; and she was surprised when he was called away for a few minutes to see that Mrs. Fowler talked with greater freedom in his absence, as though his presence put a restraint upon her.

As soon as all had finished tea, Margaret took Salome around the gardens, and afterwards led the way into the house. She showed Salome her own room, the walls of which were crowded with pictures and knickknacks. The lame girl had never seen such a pretty bedroom before as this one, with its little white-curtained bed, and white-enamelled furniture. Then Margaret opened a velvet-lined jewel case, and took out a small, gold brooch in the shape of a shell, which she insisted upon fastening into the neck of her visitor's gown.

"It is for you," she said, "I bought it with my own money, so you need not mind taking it. I told mother I was going to give it to you. I want you to wear it for my sake, Salome."

"Oh, Miss Margaret, how kind of you! Thank you so much. But ought I to take it? Are you sure Mrs. Fowler—"

"Oh, yes!" Margaret interposed eagerly. "Mother would like you to have it. She said she thought it would be a very suitable gift for you. It is pretty, isn't it?"

"It is lovely!" was the enthusiastic reply. "I shall value it always, Miss Margaret, for your sake," and there were tears of pleasure and gratitude in Salome's brown eyes as she spoke.

"I am so very glad you like it," Margaret said earnestly; "but now, come downstairs to the drawing-room."

Greystone appeared quite a palatial residence to the simple village girl, accustomed to her cottage home. She noticed how soft and thick were the carpets, how handsome was the furniture; and how everything in connection with the house had been done with a view to comfort. A sense of awe crept over her, as she cast one swift glance around the spacious drawing-room. Miss Conway was at the piano, but she ceased playing as the little girls entered; and Mrs. Fowler, who was standing by the open window conversing with her husband, turned towards them immediately and requested Salome to sing.

So Salome stood, leaning upon her crutches, in the centre of the room, and lilted, without accompaniment, a simple little song she had often heard from her dead mother's lips. It was a lullaby, and she sang it so sweetly and unaffectedly that her listeners were delighted, and Mr. Fowler was surprised at the beauty of the voice which had had so little training. She gave them several other quaint west-country ballads; and then, at Mrs. Fowler's request, sang, "Abide with Me."

"I like that best," Margaret said, as she drew Salome down on a sofa by her side. "Why, how you're trembling! And your hands are quite cold!"

"Poor child! We have made her nervous, I fear," Mr. Fowler remarked. "Used your mother to sing, my dear?"

"Yes, sir, sometimes, and father used to sing in the choir, but he doesn't now. If you please," she proceeded, glancing from one to the other hesitatingly, "I think I ought to go home. Father promised to meet me outside the gate at seven o'clock, and it must be that now."

"It is a little after seven," Mr. Fowler replied, glancing at his watch.

"Then I think I must go, sir."

"You must come again soon," Mrs. Fowler said eagerly. "Thank you so much, my dear, for singing to us. You have given us very great pleasure."

"I am very glad," Salome rejoined simply and earnestly, "and I should like to tell you how much I have enjoyed myself; and thank you for all your kindness to me."

True to his promise, Josiah Petherick was waiting for his little daughter in the road outside the entrance to Greystone. He was perfectly sober, and as Salome caught sight of his stalwart figure, her face lit up with pleasure.

"Well, have you had an enjoyable time?" he inquired, smilingly.