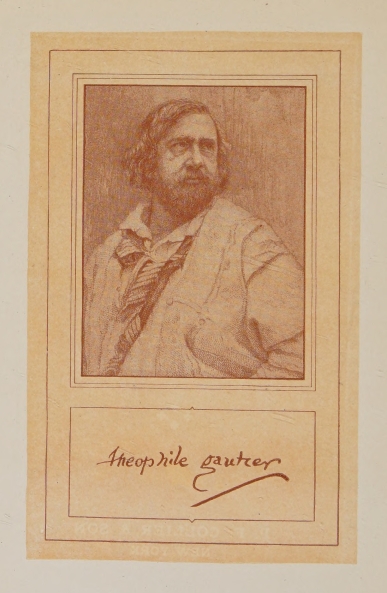

Theophile Gautier

Title: Great short stories, Volume II (of 3)

Ghost stories

Author: Various

Editor: William Patten

Release date: October 10, 2024 [eBook #74549]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: P. F. Collier

Credits: Al Haines

Edited by William Patten

A NEW COLLECTION

OF FAMOUS EXAMPLES

FROM THE LITERATURES

OF FRANCE,

ENGLAND AND AMERICA

VOLUME II

GHOST

STORIES

P. F. COLLIER & SON

NEW YORK

COPYRIGHT, 1906

BY P. F. COLLIER & SON

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LA MORTE AMOREUSE By Theophile Gautier

THE RED ROOM By H. G. Wells

THE PHANTOM 'RICKSHAW By Rudyard Kipling

THE ROLL-CALL OF THE REEF By A. T. Quiller-Couch

THE HOUSE AND THE BRAIN By Lord Edward Bulwer-Lytton

THE DREAM-WOMAN By Wilkie Collins

GREEN BRANCHES By Fiona Macleod

A BEWITCHED SHIP By W. Clark Russell

THE SIGNAL-MAN By Charles Dickens

THE FOUR-FIFTEEN EXPRESS By Amelia B. Edwards

OUR LAST WALK By Hugh Conway

THRAWN JANET By Robert Louis Stevenson

A CHRISTMAS CAROL By Charles Dickens

THE SPECTRE BRIDEGROOM By Washington Irving

THE MYSTERIOUS SKETCH By Erckmann-Chatrian

MR. HIGGINBOTHAM'S CATASTROPHE By Nathaniel Hawthorne

THE WHITE OLD MAID By Nathaniel Hawthorne

WANDERING WILLIE'S TALE By Sir Walter Scott

BY THEOPHILE GAUTIER

Theophile Gautier (born 1811, died 1872) began life as a painter, turned to poetry and finally adopted prose forms for the expression of his ideas. Always an enthusiastic apostle of romanticism, he lived in an atmosphere of Oriental splendor. His style is unusually rich and sensuous, and has exerted a considerable influence on the present generation of writers.

LA MORTE AMOREUSE

THÉOPHILE GAUTIER

Have I ever loved, you ask me, my brother? Yes, I have loved! The story is dread and marvelous, and, for all my threescore years, I scarce dare stir the ashes of that memory. To you I can refuse nothing; to a heart less steeled than yours this tale could never be told by me. For these things were so strange that I can scarce believe they came into my own existence. Three long years was I the puppet of a delusion of the devil. Three long years was I a parish priest by day, while by night, in dreams (God grant they were but dreams!), I led the life of a child of this world, of a lost soul! For one kind glance at a woman's face was my spirit to be doomed; but at length, with God to aid and my patron saint, it was given to me to drive away the evil spirit that possessed me.

I lived a double life, by night and by day. All day long was I a pure priest of the Lord, concerned only with prayer and holy things; but no sooner did I close my eyes in sleep than I was a young knight, a lover of women, of horses, of hounds, a drinker, a dicer, a blasphemer, and, when I woke at dawn, meseemed that I was fallen on sleep, and did but dream that I was a priest. For those years of dreaming certain memories yet remain with me; memories of words and things that will not down. Ay, though I have never left the walls of my vicarage, he who heard me would rather take me for one that had lived in the world and left it, to die in religion, and end in the breast of God his tumultuous days, than for a priest grown old in a forgotten curé, deep in a wood, and far from the things of this earth.

Yes, I have loved as never man loved, with a wild love and a terrible, so that I marvel my heart did not burst in twain. Oh, the nights of long ago!

From my earliest childhood had I felt the call to be a priest. This was the end of all my studies, and, till I was twenty-four, my days were one long training. My theological course achieved, I took the lesser orders, and at length, at the end of Holy Week, was to be the hour of my ordination.

I had never entered the world; my world was the college close. Vaguely I knew that woman existed, but of woman I never thought. My heart was wholly pure. Even my old and infirm mother I saw but twice a year; of other worldly relations I had none.

I had no regrets and no hesitation in taking the irrevocable vow; nay, I was full of an impatient joy. Never did a young bridegroom so eagerly count the hours of his wedding. In my broken sleep I dreamed of saying the Mass. To be a priest seemed to me the noblest thing in the world, and I would have disdained the estate of poet or of king. To be a priest! My ambition saw nothing higher.

All this I tell you that you may know how little I deserve that which befell me; that you may know how inexplicable was the fascination by which I was overcome.

The great day came, and I walked to church as if I were winged or trod on air. I felt an angelic beatitude, and marveled at the gloomy and thoughtful faces of my companions, for we were many. The night I had passed in prayer. I was all but entranced in ecstasy. The bishop, a venerable old man, was in my eyes like God the Father bowed above His own eternity, and I seemed to see heaven open beyond the arches of the minster.

You know the ceremony: the Benediction, the Communion in both kinds, the anointing of the palms of the hands with consecrated oil, and finally the celebration of the Holy Rite, offered up in company with the bishop. On these things I will not linger, but oh, how true is the word of Job, that he is foolish who maketh not a covenant with his eyes! I chanced to raise my head and saw before me, so near that it seemed I could touch her, though in reality she was at some distance, and on the farther side of the railing, a young dame royally clad, and of incomparable beauty.

It was as if scales had fallen from my eyes; and I felt like a blind man who suddenly recovers his sight. The bishop, so splendid a moment ago, seemed to fade; through all the church was darkness, and the candles paled in their sconces of gold, like stars at dawn. Against the gloom that lovely thing shone out like a heavenly revelation, seeming herself to be the fountain of light, and to give it rather than receive it. I cast down my eyes, vowing that I would not raise them again; my attention was failing, and I scarce knew what I did. The moment afterward, I opened my eyes, for through my eyelids I saw her glittering in a bright penumbra, as when one has stared at the sun. Ah! how beautiful she was! The greatest painters, when they have sought in heaven for ideal beauty, and have brought to earth the portrait of our Lady, come never near the glory of this vision! Pen of poet, or palette of painter, can give no idea of her. She was tall, with the carriage of a goddess; her fair hair flowed about her brows in rivers of gold. Like a crowned queen she stood there, with her broad white brow, and dark eyebrows; with her eyes that had the brightness and life of the green sea, and at one glance made or marred the destiny of a man. They were astonishingly clear and brilliant, shooting rays like arrows, which I could actually see winging straight for my heart. I know not if the flame that lighted them came from heaven or hell, but from one or other assuredly it came.

Angel or devil, or both; this woman was no child of Eve, the mother of us all. White teeth shone in her smile, little dimples came and went with each movement of her mouth, among the roses of her cheeks. There was a lustre as of agate on the smooth and shining skin of her half-clad shoulders, and chains of great pearls no whiter than her neck fell over her breast. From time to time she lifted her head in snake-like motion, and set the silvery ruffles of her raiment quivering. She wore a flame-colored velvet robe, and from the ermine lining of her sleeves her delicate hands came and went as transparent as the fingers of the dawn. As I gazed on her, I felt within me as it were the opening of gates that had ever been barred; I saw sudden vistas of an unknown future; all life seemed altered, new thoughts wakened in my heart. A horrible pain took possession of me; each minute seemed at once a moment and an age. The ceremony went on and on, and I was being carried far from the world, at whose gates my new desires were beating. I said "Yes," when I wished to say "No," when my whole soul protested against the words my tongue was uttering. A hidden force seemed to drag them from me. This it is perhaps which makes so many young girls walk to the altar with the firm resolve to refuse the husband who is forced on them, and this is why not one of them does what she intends. This is why so many poor novices take the veil, though they are determined to tear it into shreds, rather than pronounce the vows. None dares cause so great a scandal before so many observers, nor thus betray such general expectation. The will of all imposes itself on you; the gaze of all weighs upon you like a cope of lead. And again, all is so clearly arranged in advance, so evidently irrevocable, that the intention of refusal is crushed, and disappears.

The expression of the unknown beauty changed as the ceremony advanced. Tender and caressing at first, it became contemptuous and disdainful. With an effort that might have moved a mountain, I strove to cry out that I would never be a priest; it was in vain; my tongue clave to the roof of my mouth; I could not refuse even by a sign. Though wide awake, I seemed to be in one of those nightmares, wherein for your life you can not utter the word on which your life depends. She appeared to understand the torture which I endured, and cast on me a glance of divine pity and divine promise. "Be mine," she seemed to say, "and I shall make thee happier than God and heaven, and His angels will be jealous of thee. Tear that shroud of death wherein thou art swathed, for I am beauty, and I am youth, and I am life; come to me and we shall be love. What can Jehovah offer thee in exchange for thy youth? Our life will flow like a dream in the eternity of a kiss. Spill but the wine from that chalice, and thou are free, and I will carry thee to the unknown isles, and thou shalt sleep on my breast in a bed of gold beneath a canopy of silver, for I love thee and would fain take thee from thy God, before whom so many noble hearts pour forth the incense of their love, which dies before it reaches the heaven where He dwells." These words I seemed to hear singing in the sweetest of tunes, for there was a music in her look, and the words which her eyes sent to me resounded in my heart as if they had been whispered in my soul. I was ready to foreswear God, and yet I went duly through each rite of the ceremony. She cast me a second glance, so full of entreaty and despair, that I felt more swords pierce my breast than stabbed the heart of our Lady of Sorrows.

It was over, and I was a priest.

Then never did human face declare so keen a sorrow: the girl who sees her betrothed fall dead at her side, the mother by the empty cradle of her child, Eve at the gate of Paradise, the miser who seeks his treasure and finds a stone, even they look less sorely smitten, less inconsolable.

The blood left her fair face pale, white as marble she seemed; her lovely arms fell powerless, her feet failed beneath her, and she leaned against a pillar of the church. For me, I staggered to the door, with a white, wet face, breathless, with all the weight of all the dome upon my head. As I was crossing the threshold, a hand seized mine, a woman's hand. I had never felt before a woman's hand in mine. It was cold as the skin of a serpent, yet it burned me like a brand. "Miserable man, what hast thou done?" she whispered, and was lost in the crowd.

The old bishop paused, and gazed severely at me, who was a piteous spectacle, now red, now pale, giddy, and faint. One of my fellows had compassion on me, and led me home. I could not have found the way alone. At the corner of a street, while the young priest's head was turned, a black page, strangely clad, came up to me, and gave me, as he passed, a little leathern case, with corners of wrought gold, signing me to hide it. I thrust it into my sleeve, and there kept it till I was alone in my cell. Then I opened the clasp; there were but these words written: "Clarimonde, at the Palazzo Concini." So little of a worldling was I, that I had never heard of Clarimonde, despite her fame, nay, nor knew where the Palazzo Concini might be. I made a myriad guesses, each wilder than the other; but, truth to tell, so I did but see her again, I recked little whether Clarimonde were a noble lady, or no better than one of the wicked.

This love, thus born in an hour, had struck root too deep for me to dream of casting it from my heart. This woman had made me utterly her own, a glance had been enough to change me, her will had passed upon me; I lived not for myself, but in her and for her.

Many mad things did I, kissing my hand where hers had touched it, repeating her name for hours: Clarimonde, Clarimonde! I had but to close my eyes, and I saw her as distinctly as if she had been present. Then I murmured to myself the words that beneath the church porch she had spoken: "Miserable man, what hast thou done?" I felt all the horror of that strait wherein I was, and the dead and terrible aspect of the life that I had chosen was now revealed. To be a priest! Never to love, to know youth nor sex, to turn from beauty, to close the eyes, to crawl in the chill shade of a cloister or a church; to see none but deathly men, to watch by the nameless corpses of folk unknown, to wear a cassock like my own mourning for myself, my own raiment for my coffin's pall.

Then life arose in me like a lake in flood, my blood coursed in my veins, my youth burst forth in a moment; like the aloe, which flowers but once in a hundred years, and breaks into blossom with a sound of thunder!

How was I again to have sight of Clarimonde? I had no excuse for leaving the seminary, for I knew nobody in town, and indeed was only waiting till I should be appointed to my parish. I tried to remove the bars of the window, but to descend without a ladder was impossible. Then, again, I could only escape by night, when I should be lost in the labyrinth of streets. These difficulties, which would have been nothing to others, were enormous to a poor priest like me, now first fallen in love, without experience, or money, or knowledge of the world.

Ah, had I not been a priest I might have seen her every day, I might have been her lover, her husband, I said to myself in the blindness of my heart. In place of being swathed in a cassock I might have worn silk and velvet, chains of gold, a sword and feather like all the fair young knights. My locks would not be tonsured, but would fall in perfumed curls about my neck. But one hour spent before an altar, and some gabbled words, had cut me off from the company of the living. With my own hand I had sealed the stone upon my tomb, and turned the key in the lock of my prison!

I walked to the window. The sky was heavenly blue, the trees had clothed them in the raiment of spring, all nature smiled with mockery in her smile. The square was full of people coming and going: young exquisites, young beauties, two by two, were walking in the direction of the gardens. Workmen sang drinking songs as they passed; on all sides were a life, a movement, a gaiety that did but increase my sorrow and my solitude. A young mother, on the steps of the gate, was playing with her child, kissing its little rosy mouth, with a thousand of the caresses, the childlike and the divine caresses that are the secret of mothers. Hard by the father, with folded arms above a happy heart, smiled sweetly as he watched them. I could not endure the sight. I shut the window, and threw myself on the bed in a horrible jealousy and hatred, so that I gnawed my fingers and my coverlet like a starved wild beast.

How many days I lay thus I know not, but at last, as I turned in a spasm of rage, I saw the Abbé Sérapion curiously considering me. I bowed my head in shame, and hid my face with my hands. "Romuald, my friend," said he, "some strange thing hath befallen thee. Satan hath desired to have thee, that he may sift thee like wheat; he goeth about thee to devour thee like a raging lion. Beware and make thyself a breastplate of prayer, a shield of the mortifying of the flesh. Fight, and thou shalt overcome. Be not afraid with any discouragement, for the firmest hearts and the most surely guarded have known hours like these. Pray, fast, meditate, and the evil spirit will pass away from thee."

Then Sérapion told me that the priest of C—— was dead, that the bishop had appointed me to this charge, and that I must be ready by the morrow. I nodded assent, and the Abbé departed. I opened my missal and strove to read in it, but the lines waved confusedly, and the volume slipped unheeded from my hands.

Next day Sérapion came for me; two mules were waiting for us at the gate with our slender baggage, and we mounted as well as we might. As we traversed the streets I looked for Clarimonde, in each balcony, at every window; but it was too early, and the city was yet asleep. When we had passed the gates, and were climbing the height, I turned back for a last glance at the place that was the home of Clarimonde. The shadow of a cloud lay on the city, the red roofs and the blue were mingled in a mist, whence rose here and there white puffs of smoke. By some strange optical effect, one house stood up, golden in a ray of light, far above the roofs that were mingled in the mist. A league away though it was, it seemed quite close to us—all was plain to see, turrets, balconies, parapets, the very weathercocks.

"What is that palace we see yonder in the sunlight?" said I to Sérapion.

He shaded his eyes with his hand, looked, and answered:

"That is the old palace which Prince Concini has given to Clarimonde the harlot. Therein dreadful things are done."

Even at that moment, whether it were real or a vision I know not now, methought I saw a white and slender shape come across the terrace, glance, and disappear. It was Clarimonde!

Ah, did she know how in that hour, at the height of the rugged way which led me from her, even at the crest of the path I should never tread again, I was watching her, eager and restless, watching the palace where she dwelt, and which a freak of light and shadow seemed to bring near me, as if inviting me to enter and be lord of all? Doubtless she knew it, so closely bound was her heart to mine; and this it was which had urged her, in the raiment of the night, to climb the palace terrace in the frosty dews of dawn.

The shadow slipped over the palace, and, anon, there was but a motionless sea of roofs, marked merely by a billowy undulation of forms. Sérapion pricked on his mule, mine also quickened, and a winding of the road hid from me forever the city of S——, where I was to return no more. At the end of three days' journey through melancholy fields, we saw the weathercock of my parish church peeping above the trees. Some winding lanes, bordered by cottages and gardens, brought us to the building, which was of no great splendor. A porch with a few moldings, and two or three pillars rudely carved in sandstone, a tiled roof with counter-forts of the same stone as the pillars—that was all. To the left was the graveyard, deep in tall grasses, with an iron cross in the centre. The priest's house was to the right, in the shadow of the church. Simplicity could not be more simple, nor cleanliness less lovely. Some chickens were pecking at a few grains of oats on the ground as we entered. The sight of a priest's frock seemed too familiar to alarm them, and they scarcely moved to let us pass. Then we heard a hoarse and wheezy bark, and an old dog ran up to greet us. He was the dog of the late priest—dim-eyed, gray, with every sign of a dog's extreme old age. I patted him gently, and he walked along by my side with an air of inexpressible satisfaction. An elderly woman, my predecessor's housekeeper, came in her turn to greet us; and when she learned that I meant to keep her in my service, to keep the dog and the chickens, with all the furniture that her master had left her at his death—above all, when the Abbé Sérapion paid what she asked on the spot—her joy knew no bounds.

When I had been duly installed, Sérapion returned to the college, and I was left alone. Unsupported, uncomforted as I was, the thought of Clarimonde again beset me, nor could I drive her memory away for all my efforts. One evening, as I walked among the box-lined paths of my little garden, I fancied that I saw among the trees the form of a woman, who followed all my movements, and whose green eyes glistened through the leaves. Green as the sea shone her eyes, but it was no more than a vision, for when I crossed to the other side of the alley nothing did I find but the print of a little foot on the sand—a foot like the foot of a child. Now the garden was girt with high walls, and, for all my search, I could find no living thing within them. I have never been able to explain this incident, which, after all, was nothing to the strange adventures that were to follow.

Thus did I live for a whole year, fulfilling every duty of the priesthood—preaching, praying, fasting, visiting the sick, denying myself necessaries that I might give to the poor. But within me all was dry and barren—the fountains of grace were sealed. I knew not the happiness which goes with the consciousness of a holy mission fulfilled. My heart was otherwhere; the words of Clarimonde dwelt on my lips like the ballad burden a man repeats against his will. Oh, my brother, consider this! For the lifting up of mine eyes to behold a woman have I been harried these many years, and my life hath been troubled forever.

I shall not hold you longer with the story of these defeats and these victories and the fresh defeats of my soul; let me come to the beginning of the new life.

One night there was a violent knocking at my gate. The old housekeeper went to open it, and the appearance of a man richly clad in an outlandish fashion, tawny of hue, armed with a long dagger, stood before her in the light of her lantern. She was terrified, but he soothed her, saying that he needs must see me instantly concerning a matter of my ministry. Barbara brought him upstairs to the room where I was about going to bed. There the man told me that his mistress, a lady of high degree, was on the point of death, and desired to see a priest. I answered that I was ready to follow him, and taking with me such matters as are needful for extreme unction, I went down hastily. At the door were two horses, black as night, their breath rising in white clouds of vapor. The man held my stirrup while I mounted; then he laid one hand on the pommel and vaulted on the other horse. Gripping his beast with his knees, he gave him his head, and we started with the speed of an arrow, my horse keeping pace with his own. We seemed in running to devour the way; the earth flitted gray beneath us, the black trees fled in the darkness like an army in rout. A forest we crossed, so gloomy and so frozen cold that I felt in all my veins a shudder of superstitious dread. The sparks struck from the flints by our coursers' feet followed after us like a trail of fire, and whoever saw us must have deemed us two ghosts riding the nightmare. Will-o'-the-wisps glittered across our path, the night birds clamored in the forest deeps, and now and again shone out the burning eyes of wild-cats.

The manes of the horses tossed more wildly on the wind, the sweat ran down their sides, their breath came thick and loud. But whenever they slackened, the groom called on them with a cry like nothing that ever came from a human throat, and again they ran their furious course. At last the tempest of their flight reached its goal; suddenly there stood before us a great dark mass, with shining points of flame. Our horses' hoofs clattered louder on a drawbridge, and we thundered through the dark depths of a vaulted entrance which gaped between two monstrous towers. Within the castle all was confusion—servants with burning torches ran hither and thither through the courts; on the staircases lights rose and fell. I beheld a medley of vast buildings, columns, arches, parapet and balcony—a bewildering world of royal or of fairy palaces. The negro page who had given me the tablets of Clarimonde, and whom I recognized at a glance, helped me to alight. A seneschal in black velvet, with a golden chain about his neck, and an ivory wand in his hand, came forward to meet me, great tears rolling down his cheeks to his snowy beard.

"Too late," he said; "too late, sir priest! But if thou hast not come in time to save the soul, watch, I pray thee, with the unhappy body of the dead."

He took me by the arm; he led me to the hall, where the corpse was lying, and I wept as bitterly as he, deeming that the dead was Clarimonde, the well and wildly loved. There stood a prie-dieu by the bed; a blue flame flickering from a cup of bronze cast all about the chamber a doubtful light, and here and there set the shadows fluttering. In a chiseled vase on the table was one white rose faded, a single petal clinging to the stem; the rest had fallen like fragrant tears and lay beside the vase. A broken mask, a fan, masquerading gear of every kind were huddled on the chairs, and showed that death had come, unlooked for and unheralded, to that splendid house. Not daring to cast mine eyes upon the bed, I kneeled, and fervently began to repeat the Psalms, thanking God that between this woman and me He had set the tomb, so that now her name might come like a thing enskied and sainted in my prayers.

By degrees this ardor slackened, and I fell a-dreaming. This chamber, after all, had none of the air of a chamber of death. In place of the fetid, corpse-laden atmosphere that I was wont to breathe in these vigils, there floated gently through the warmth a vapor of Orient essences, a perfume of women and of love. The pale glimmer of the lamp seemed rather the twilight of pleasure than the yellow burning of the taper that watches by the dead. I began to think of the rare hazard that brought me to Clarimonde in the moment when I had lost her forever, and a sigh came from my breast. Then meseemed that one answered with a sigh behind me, and I turned unconsciously. 'Twas but an echo, but, as I turned, mine eyes fell on that which they had shunned—the bed where Clarimonde lay in state. The flowered and crimson curtains, bound up with loops of gold, left the dead woman plain to view, lying at her length, with hands folded on her breast. She was covered with a linen veil, very white and glistening, the more by reason of the dark purple hangings, and so fine was the shroud that her fair body shone through it, with those beautiful soft waving lines, as of the swan's neck, that not even death could harden. Fair she was as a statue of alabaster carved by some skilled man for the tomb of a queen; fair as a young maid asleep beneath new-fallen snow.

I could endure no longer. The air as of a bower of love, the scent of the faded rose intoxicated me, and I strode through the chamber, stopping at each turn to gaze at the beautiful dead beneath the transparent shroud. Strange thoughts haunted my brain. I fancied that she was not really gone, that it was but a device to draw me within her castle gates, and to tell me all her love.

Nay, one moment methought I saw her foot stir beneath its white swathings, and break the stiff lines of the shroud.

"Is she really Clarimonde?" I asked myself presently. "What proof have I? The black page may have entered the household of some other lady. Mad must I be thus to disquiet myself."

But the beating of my own heart answered me, "It is she! It is she!"

I drew near the bed, and looked with fresh attention at that which thus perplexed me. Shall I confess it? The perfection of her beauty, though shadowed and sanctified by death, troubled my heart, and that long rest of hers was wondrous like a living woman's sleep. I forgot that I had come there to watch by a corpse, and I dreamed that I was a young bridegroom entering the chamber of the veiled, half-hidden bride. Broken with sorrow, wild with joy, shuddering with dread and desire, I stooped toward the dead and raised a corner of the sheet. Gently I raised it, holding my breath as though I feared to waken her. My blood coursed so vehemently that I heard it rushing and surging through the veins of my temples. My brow was dank with drops of sweat, as if I had lifted no film of linen, but a weighty gravestone of marble.

There lay Clarimonde, even as I had seen her on the day of mine ordination; even so delightful was she, and death in Clarimonde seemed but a wilful charm. The pallor of her cheeks, her dead lips fading rose, her long downcast eyelids, with their brown lashes, breaking the marble of her cheek, all gave her an air of melancholy, and of purity, of pensive patience that had an inexpressible winning magic. Her long loose hair, the small blue flowers yet scattered through it, pillowed her head, and veiled the splendor of her shoulders. Her fair hands, clear and pure as the consecrated wafer, were crossed in an attitude of holy rest and silent prayer, that suffered not the exquisite roundness and ivory polish of her pearled arms to prove, even in death, too triumphant a lure of men.

Long did I wait and watch her silently, and still the more I gazed, the less I could deem that life had left forever her beautiful body. I knew not if it were an illusion, or a reflection from the lamp, but it was as if the blood began to flow again beneath that dead white of her flesh, and yet she lay eternally, immovably still. I touched her arm; it was cold, but no colder than her hand had been on the day when it met mine beneath the church porch. I fell into my old attitude, stooping my face above her face, while down upon her rained the warm dew of my tears. Oh, bitterness of impotence and of despair; oh, wild agony of that death watch!

The night crept on, and as I felt that the eternal separation drew near, I could not deny myself the sad last delight of one kiss on the dead lips that held all my love.

Oh, miracle! A light breath mingled with my breath, and the mouth of Clarimonde answered to the touch of mine! Her eyes opened, and softly shone. She sighed, she uncrossed her arms, and, folding them about my neck in a ravished ecstasy:

"Ah, Romuald, it is thou!" she said in a voice as sweet and languishing as the last tremblings of a lyre. "Ah, Romuald, what makest thou here? So long have I waited for thee that I am dead. Yet now we are betrothed, now I may see thee, and visit thee. Farewell, Romuald, farewell! I love thee. It is all that I had to tell thee, and I give thee again that life which thou gavest me with thy kiss. Soon shall we meet again."

Her head sank down, but still her arms clung to me as if they would hold me forever. A wild gust of wind burst open the window and broke into the room. The last leaf of the white rose fluttered like a bird's wing on the stem, and then fell and flew through the open casement, bearing with it the soul of Clarimonde.

The lamp went out, and I fell fainting on the breast of the beautiful corpse.

When I came to myself I was lying on my own bed in the little chamber of the priest's house; my hand had slipped from beneath the coverlet, the old dog was licking it. Barbara hobbled and trembled about the room, opening and shutting drawers, and shaking powders into glasses. The old woman gave a cry of delight when she saw me open my eyes. The dog yelped and wagged his tail, but I was too weak to utter a word or make the slightest movement. Later, I learned that for three days I had lain thus, with no sign of life but a scarce perceptible breathing. These three days do not count in my life; I know not where my spirit went wandering all that time, whereof I keep not the slightest memory. Barbara told me that the same bronzed man who had come for me at night brought me back in a closed litter next morning, and instantly went his way. So soon as I could recall my thoughts, I reviewed each incident of that fatal night. At first I deemed that I had been duped by art magic, but presently actual, palpable circumstances destroyed that belief. I could not suppose that I had been dreaming, for Barbara, no less than myself, had seen the man with the two coal-black steeds, and she described them accurately. Yet no one knew of any castle in the neighborhood at all like that in which I had found Clarimonde again.

One morning Sérapion entered my room; he had come with all haste in answer to Barbara's message about my illness. Though this declared his affection for me, none the more did his visit give me pleasure. There was something inquisitive and piercing to my mind in the very glance of Sérapion, and I felt like a criminal in his presence. He it was who first discovered my secret disquiet, and I bore him a grudge for being so clear-sighted.

While he was asking about my health, in accents of honeyed hypocrisy, his eyes, as yellow as a lion's, were sounding the depths of my soul. Presently—"The famous harlot Clarimonde is dead," says he, in a piercing tone, "dead at the close of an eight days' revel. It was a feast of Belshazzar or of Cleopatra. Good God, what an age is ours! The guests were served by dusky slaves who spoke no tongue known among men, and who seemed like spirits from the pit. The livery of the least of them might have beseemed an emperor on a coronation day. Wild tales are told of this same Clarimonde, and all her loves have perished miserably or by violence. They say she was a ghost, a female vampire, but I believe she was the devil himself."

He paused, watching me, who could not master a sudden movement at the name of Clarimonde.

"Satan's claw is long," said Sérapion, with a stern glance, "and tombs ere now have given up their dead. Threefold should be the seal upon the grave of Clarimonde, for this is not, men say, the first time she hath died. God be with thee, Romuald!"

So speaking, Sérapion departed with slow steps, and I saw him no more as at that time.

Time passed and I was well again. Nay, I deemed that the fears of Sérapion and my own terrors were too great, till, one night, I dreamed a dream.

Scarce had I tasted the first drops of the cup of sleep when I heard the curtains of my bed open and the rings ring. I raised myself suddenly on my arm and saw the shadow of a woman standing by me.

Straightway I knew her for Clarimonde.

She held in her hand a little lamp, such as are placed in tombs, and the light touched her slim fingers to a rosy hue, that faded away in the milk-white of her arms. She was clad with naught on but the linen shroud that veiled her when she lay in state; the folds were clasped about her breast, as it were in pudency, by a hand all too small. So white she was that her shroud and her body were blended in the pallid glow of the lamp.

Swathed thus in the fine tissue that betrayed every line of her figure, she seemed a marble image of some lady at the bath rather than a living woman. Dead or living, statue or woman, spirit or flesh, her beauty was the same; only the glitter of her dull sea-green eyes was dulled—only the mouth, so red of old, wore but a tender tint of rose, like the white rose of her cheeks. The little blue flowers that I had seen in her hair were sere now, and all but bloomless; yet so winning was she, so winning that, despite the strangeness of the adventure and her inexplicable invasion of my chamber, I was not afraid for one moment.

She placed the lamp on the table, and sat down by my bed-foot. Then, in those soft and silver accents which I never heard from any lips but hers—"Long have I made thee wait for me," she said, "and thou must have deemed that I had forgotten thee quite. But lo! I come from far, very far—even from that land whence no traveler has returned. There is no sunlight nor moon in the country whence I wander, only shadow and space. There the foot finds no rest, nor the wandering wing any way; yet here am I; behold me, for Love can conquer Death. Ah, what sad faces and terrible eyes have I seen in my voyaging, and in what labor hath my soul been to find my body and to make her home therein again! How hard to lift was the stone that they had laid on me for a covering! Lo, my hands are sorely wounded in that toil! Kiss them, my love, and heal them." And she laid her chill palms, on my mouth, that I kissed many times, she smiling on me with an inexpressible sweetness of delight.

To my shame be it spoken, I had wholly forgotten the counsels of the Abbé Sérapion, and the sacred character of my ministry. I fell unresisting at the first attack. Nay, I did not even try to bid the tempter avaunt, but succumbed without a struggle before the sweet freshness of Clarimonde's fair body. Poor child! for all that is come and gone, I can scarce believe that she was indeed a devil; surely there was naught of the devil in her aspect. Never hath Satan better concealed his claws and his horns!

She was crouching on the side of my bed, her heels drawn up beneath her in an attitude of careless and provoking grace. Once and again she would pass her little hands among my locks, and curl them, as if to try what style best suited my face. It is worth noting that I felt no astonishment at an adventure so marvelous—nay, as in a dream the strangest events fail to surprise us, even so the whole encounter seemed to me perfectly natural.

"I loved thee long before I saw thee, Romuald, my love, and I sought for thee everywhere. Thou wert my dream, and I beheld thee in the church at that fatal hour. 'It is he,' I whispered to myself, and cast on thee a glance fulfilled of all the love wherewith I had loved, and did love, and shall love thee; a glance that would have ruined the soul of a cardinal or brought a king with all his court to my feet.

"But thou wert not moved, and before my love thou didst place the love of God.

"Ah, 'tis of God that I am jealous—God whom thou hast loved and lovest more than me.

"Miserable woman that I am! Never shall I have all thy heart for myself alone—for me, whom thou didst awaken with one kiss; for me, Clarimonde, the dead; for me, who for thy sake have broken the portals of the grave, and am come to offer to thee a life that hath been taken up again for this one end to make thee happy."

So she spoke; and every word was broken in on by maddening caresses, till my brain swam, and I feared not to console her by this awful blasphemy, namely—That my love of her passed my love of God!

Then the fire of her eyes was rekindled, and they blazed as it had been the chrysoprase stone.

"Verily thou lovest me with a love like thy love of God," she cried, making her fair arms a girdle for my body. "Then thou shalt come with me, and whithersoever I go wilt thou follow. Thou wilt leave thine ugly black robes, thou wilt be of all knights the proudest and the most envied. The acknowledged lover of Clarimonde shalt thou be, of her who refused a Pope! Ah, happy life, oh, golden days that shall be ours! When do we mount and ride, mon gentilhomme?"

"To-morrow," I cried in my madness.

"To-morrow," she answered, "I shall have time to change this robe of mine that is somewhat scant, nor fit for voyaging. Also must I speak with my retainers, that think me dead in good earnest, and lament me, as well they may. Money, carriages, change of raiment, all shall be ready for thee; at this hour to-morrow will I seek thee. Good-by, sweetheart."

She touched my brow with her lips, the lamp faded into darkness, the curtains closed, a sleep like lead came down on me, sleep without a dream.

I wakened late, troubled by the memory of my dream, which at length I made myself believe was but a vision of the night. Yet it was not without dread that I sought rest again, praying Heaven to guard the purity of my slumber.

Anon I fell again into a deep sleep, and my dream began again. The curtains opened, and there stood Clarimonde, not pale in her pale shroud, nor with the violets of death upon her cheek; but gay, bright, splendid, in a traveling robe of green velvet with trappings of gold, and kilted up on one side to show a satin undercoat. Her fair, curled locks fell in great masses from under a large black beaver hat, with strange white plumes; in her hand she held a little riding-whip, topped with a golden whistle. With this she touched me gently, saying:

"Awake, fair sleeper! Is it thus you prepare for your voyage? I had thought to find you alert. Rise, quickly; we have no time to lose!"

I leaped out of bed.

"Come, dress, and let us be gone," she said, showing me a packet she had brought. "Our horses are fretting and champing at the gate. We should be ten leagues from here."

I arrayed myself in haste, while she instructed me, handed me the various articles of a knight's attire, and laughed at my clumsiness. She dressed my hair, and when all was done, gave me a little Venice pocket-mirror in a silver frame, crying:

"What think you of yourself now? Will you take me for your valet de chambre?"

I did not know my own face in the glass, and was no more like myself than a statue is like the uncut stone. I was beautiful, and I was vain of the change. The gold embroidered gallant attire made me another man, and I marveled at the magic of a few ells of cloth, fashioned to certain device. The character of my clothes became my own, and in ten minutes I was sufficiently conceited.

Clarimonde watched me with a kind of maternal fondness as I walked up and down the room, proving my new raiment as it were; then:

"Come," she cried; "enough of this child's play! Up and away, my Romuald! We have far to go; we shall never arrive."

She took my hand and led me forth. The gates opened at her touch; the dog did not waken as we passed.

At the gate we found the groom with three horses like those he had led before: Tennets of Spain, the children of the wind. Swift as the wind they sped; and the moon that had risen to light us at our going, spun down the sky behind us like a wheel broken loose from the axle; we seemed to see her on our right, leaping from tree to tree as she strove to follow our course. Presently we came on a plain, where a carriage with four horses waited for us; and the postilion drove them to a mad gallop. My arm was round the waist of Clarimonde, her head lay on my shoulder, her breast touched my arm. Never had I known such delight. All that I had been was forgotten, like the months before birth, so great was the power of the devil over my heart.

From that date mine became a double life; within me were two men that knew each other not—the priest who dreamed that by night he was a noble, the noble who dreamed that by night he was a priest. I could not divide dreams from waking, nor tell where truth ended and illusion began. Two spirals, blended but touching not, might be a parable of my confused existence. Yet, strange as it was, I believe I never was insane. The experience of either life dwells distinct and separate in my memory. Only there was this inexplicable fact—the feeling of one personality existed in both these two different men. Of this I have never found an explanation, whether I was for the moment the curé of the village of ——, or whether I was Signor Romualdo, the avowed lover of Clarimonde.

Certain it is that I was, or believed myself to be, in Venice—in a great palace on the Grand Canal, full of frescoes, statues, and rich in two Titians of his best period—a palace fit for a king. We had each our gondola, our liveried men, our music, our poet, for Clarimonde loved life in the great style, and in her nature was a touch of Cleopatra. Custom could not stale her infinite variety; to love her was to love a score of mistresses, and you were faithless to her with herself, so strangely she could wear the beauty of any woman that caught your fancy. She returned my love a hundred-fold. She scorned the gifts of young patricians and of the elders of the Council of Ten. She refused the hand of a Foscari. Gold enough she had, she desired only love; a young fresh love herself had wakened—a love that found in her its first mistress and its last.

As for me, in the midst of a life of the wildest pleasure, I should have been happy but for the nightly horror of the dream wherein I was a curé, fasting and mortifying myself in penance for the sins of the day. Custom made my life with her familiar, and it was rarely that I remembered (and that never with fear) the words of the Abbé Sérapion.

For some time Clarimonde had not been herself, her health failing, her complexion growing paler day by day. The physicians were of no avail, and she grew cold and dead as on the wondrous night in the nameless castle. Sadly she smiled on my distress, with the fatal smile of those who know that their death is near. One morning I sat on her bed, breakfasting at a small table hard by; as it chanced in cutting a fruit I gashed my finger deeply; the blood came in purple streams; and spurted up on Clarimonde. Her eyes brightened, her face took on a savage joy and greed such as I had never seen. She leaped from the bed like a cat, seized my wounded hand, and sucked the blood with unspeakable pleasure, slowly, gently like a connoisseur tasting some rare wine.

In her half-closed eyes the round pupil grew long in shape. Again and again she stopped to kiss my hand, and then pressed her lips once more on the wound, to squeeze out the red drops.

When she saw that the blood was stanched, she rose; her eyes brilliant and humid, her face as rosy as a dawn of May, her hand warm and moist; in short, more lovely than of old, and in perfect health.

"I shall not die! I shall not die!" she exclaimed, wild with delight, as she embraced me. "I shall yet love thee long; for my life is in thine, and all that is in me comes from thee. Some drops of thy rich and noble blood, more precious than all the elixirs in the world, have given me back my life."

This event, and the strange doubts it inspired, haunted me long. When the night and sleep brought me back to my priest's home, I beheld Sérapion, more anxious than ever, more careful and troubled. He gazed on me steadfastly, and said:

"Not content with losing thy soul, thou art also desirous of ruining thy body. Unhappy young man, in what a net hast thou fallen!"

The tone of his voice struck cold on me; but a thousand new cares made me forget his words. Yet, one night I saw in a mirror that Clarimonde was pouring a powder into the spiced wine-cup she mingled after supper. I took the cup, pretending to drink, but really casting the potion away beneath the table. Then I went to bed, intent on watching and seeing what should come to pass. Nor did I wait long. Clarimonde entered, cast off her night attire, and lay down by my side. When she was assured that I slept, she uncovered my arm, drew a golden pin from her hair, and then fell a-murmuring thus:

"One drop, one little crimson drop, one ruby on the tip of my needle! Since thou lovest me yet, I must not die. Sleep, my god, my child, my all; I shall not harm thee; of thy life I will but take what is needful for mine. Alas! poor love; alas! fair purple blood that I must drink! Ah, fair arm, so round, so white, never will I dare to prick that pretty violet vein."

So speaking, she wept, and the tears fell hot on my arm. At length she came to a resolve, pricked me with the needle, and sucked the blood that flowed. But a few drops did she taste, for fear of exhausting me, then she anointed the tiny wound, and fastened a little bandage about my arm.

I could no longer doubt it, Sérapion had spoken sooth. Yet must I needs love Clarimonde, and would willingly have given her all the blood in my veins that then were rich enough. Nor was I afraid, the woman in her was more than surety for the vampire. I could have pricked my own arm and said, "Drink; let my love become part of thy being with my blood." I never spoke a word of the narcotic that she had poured out for me, never a word of the needle; we lived together in perfect union of hearts.

It was my scruples as a priest that disquieted me. How could I touch the Host with hands polluted in such debauches, real or dreamed of? At night I struggled against sleep, holding mine eyelids open, standing erect against walls; but mine eyes were filled with the sand of sleep, and the wave carried me even where it would, down to the siren shores.

Sérapion reproached me often. One day he came and said: "To drive away the devil that possesses thee there is but one art; great ills demand harsh remedies. I know where Clarimonde is buried; we must unearth her, and the sight of the worms and the dust of death will make thee thyself again."

So weary was I of my double life, so eager to know whether the priest or the noble was the true man, which the dream, that I accepted his plan, being determined to slay one or the other of the beings that dwelt within me; ay, or to slay them both, for such a life as mine could not endure.

The Abbé Sérapion took a lantern, a pick, a crowbar, and at midnight we set out for the graveyard. After throwing the light of the lantern on several tombs, we reached a stone half-hidden by tall weeds, and covered with ivy, moss, and lichen. Thereon we read these words graven:

ICI GIT CLARIMONDE

QUI PUT DE SON VIVANTE

LA PLUS BELLE DU MONDE

"'Tis here!" said Sérapion, who, laying down his lantern, thrust the crowbar in a cleft of the stone, and began to raise it. Slowly it gave place, and he set to work with the pick-ax. For me, I watched him dark and silent as the night, while his face, when he raised it, ran with sweat, and his laboring breath came like the death-rattle in his throat. Methought the deed was a sacrilege, and I would fain have seen the lightning leap from the cloud, and strike Sérapion to ashes.

The owls of the graveyard, attracted by the light, flocked and flapped about the lantern with their wings; their hooting sounded wofully; the foxes barked their answer far away; a thousand evil sounds broke from the stillness.

At length the pick of Sérapion smote the coffin-lid; the four planks answered sullenly, as the void of nothingness replied to the touch. Sérapion raised the coffin-lid, and there I saw Clarimonde, pale as marble, her hands joined, the long white shroud flowing unbroken to her feet.

On her pale mouth shone one rosy drop, and Sérapion, breaking forth in fury, cried:

"Ah, there thou liest, devil, harlot, vampire, thou that drainest the blood of men!"

With this he sprinkled holy water over my lady, whose fair body straightway crumbled into earth, a dreadful mingling of dust and the ashes of bones half-burned.

"There lies thy leman, Sir Romuald," he said; "go now and dally at the Lido with thy beauty."

I bowed my head; within me all was ruin. Back to my poor priest's house I went; and Romuald, the lover of Clarimonde, said farewell to the priest, with whom so long and so strangely he had companioned.

But, next night, I saw Clarimonde.

"Wretched man that thou art," she cried, as of old under the church porch, "what hast thou done? Why hast thou hearkened to that foolish priest? Wert thou not happy, or what ill had I done thee that thou must violate my tomb, and lay bare the wretchedness of the grave? Henceforth is the link between our souls and bodies broken. Farewell! Thou shalt desire me."

Then she fled away into air, like smoke, and I saw her no more.

Alas! it was truth she spoke; more than once have I sorrowed for her—nay, I long for her still. Dearly purchased hath my salvation been, and the love of God hath not been too much to replace the love of her.

Behold, brother, all the story of my youth.

Let not thine eyes look ever upon a woman; walk always with glance downcast; for, be ye chaste and be ye cold as ye may, one minute may damn you to all eternity.

(Translation by Andrew Lang.)

BY H. G. WELLS

Herbert George Wells (born 1866), on his graduation in 1888 from the Royal College of Science, took up the serious side of science as a career, publishing in 1892-93 a textbook on biology. An editorial connection (with "The Saturday Review" in 1894-96) turned his attention to the literary possibilities of his favorite study, and in 1895 he began a series of novels in which by an extraordinary prescience of imagination he developed the suggestions of modern science into marvelous embodiments of newly discovered principles and powers which are shown to result in profound changes in both the social and individual character of man.

THE RED ROOM

By H. G. WELLS

"I can assure you," said I, "that it will take a very tangible ghost to frighten me." And I stood up before the fire with my glass in my hand.

"It is your own choosing," said the man with the withered arm, and glanced at me askance.

"Eight-and-twenty years," said I, "I have lived, and never a ghost have I seen as yet."

The old woman sat staring hard into the fire, her pale eyes wide open. "Ay," she broke in, "and eight-and-twenty years you have lived, and never seen the likes of this house, I reckon. There's a many things to see, when one's still but eight-and-twenty." She swayed her head slowly from side to side. "A many things to see and sorrow for."

I half suspected these old people were trying to enhance the spectral terrors of their house by this droning insistence. I put down my empty glass on the table, and, looking about the room, caught a glimpse of myself, abbreviated and broadened to an impossible sturdiness, in the queer old mirror beside the china cupboard. "Well," I said, "if I see anything to-night, I shall be so much the wiser. For I come to the business with an open mind."

"It's your own choosing," said the man with the withered arm once more.

I heard the faint sound of a stick and a shambling step on the flags in the passage outside. The door creaked on its hinges as a second old man entered, more bent, more wrinkled, more aged even than the first. He supported himself by the help of a crutch, his eyes were covered by a shade, and his lower lip, half averted, hung pale and pink from his decaying yellow teeth. He made straight for an armchair on the opposite side of the table, sat down clumsily, and began to cough. The man with the withered hand gave the new-comer a short glance of positive dislike; the old woman took no notice of his arrival, but remained with her eyes fixed steadily on the fire.

"I said—it's your own choosing," said the man with the withered hand, when the coughing had ceased for a while.

"It's my own choosing," I answered.

The man with the shade became aware of my presence for the first time, and threw his head back for a moment, and sidewise, to see me. I caught a momentary glimpse of his eyes, small and bright and inflamed. Then he began to cough and splutter again.

"Why don't you drink?" said the man with the withered arm, pushing the beer toward him. The man with the shade poured out a glassful with a shaking hand, that splashed half as much again on the deal table. A monstrous shadow of him crouched upon the wall, and mocked his action as he poured and drank. I must confess I had scarcely expected these grotesque custodians. There is, to my mind, something inhuman in senility, something crouching and atavistic; the human qualities seem to drop from old people insensibly day by day. The three of them made me feel uncomfortable with their gaunt silences, their bent carriage, their evident unfriendliness to me and to one another. And that night, perhaps, I was in the mood for uncomfortable impressions. I resolved to get away from their vague foreshadowings of the evil things upstairs.

"If," said I, "you will show me to this haunted room of yours, I will make myself comfortable there."

The old man with the cough jerked his head back so suddenly that it startled me, and shot another glance of his red eyes at me from out of the darkness under the shade, but no one answered me. I waited a minute, glancing from one to the other. The old woman stared like a dead body, glaring into the fire with lack-lustre eyes.

"If," I said, a little louder, "if you will show me to this haunted room of yours, I will relieve you from the task of entertaining me."

"There's a candle on the slab outside the door," said the man with the withered hand, looking at my feet as he addressed me. "But if you go to the Red Room to-night—"

"This night of all nights!" said the old woman, softly.

"—You go alone."

"Very well," I answered, shortly, "and which way do I go?"

"You go along the passage for a bit," said he, nodding his head on his shoulder at the door, "until you come to a spiral staircase; and on the second landing is a door covered with green baize. Go through that, and down the long corridor to the end, and the Red Room is on your left up the steps."

"Have I got that right?" I said, and repeated his directions.

He corrected me in one particular.

"And you are really going?" said the man with the shade, looking at me again for the third time with that queer, unnatural tilting of the face.

"This night of all nights!" whispered the old woman.

"It is what I came for," I said, and moved toward the door. As I did so, the old man with the shade rose and staggered round the table, so as to be closer to the others and to the fire. At the door I turned and looked at them, and saw they were all close together, dark against the firelight, staring at me over their shoulders, with an intent expression on their ancient faces.

"Good-night," I said, setting the door open.

"It's your own choosing," said the man with the withered arm.

I left the door wide open until the candle was well alight, and then I shut them in, and walked down the chilly, echoing passage.

I must confess that the oddness of these three old pensioners in whose charge her ladyship had left the castle, and the deep-toned, old-fashioned furniture of the housekeeper's room, in which they foregathered, had affected me curiously in spite of my effort to keep myself at a matter-of-fact phase. They seemed to belong to another age, an older age, an age when things spiritual were indeed to be feared, when common sense was uncommon, an age when omens and witches were credible, and ghosts beyond denying. Their very existence, thought I, is spectral; the cut of their clothing, fashions born in dead brains; the ornaments and conveniences in the room about them even are ghostly—the thoughts of vanished men, which still haunt rather than participate in the world of to-day. And the passage I was in, long and shadowy, with a film of moisture glistening on the wall, was as gaunt and cold as a thing that is dead and rigid. But with an effort I sent such thoughts to the right-about. The long, drafty subterranean passage was chilly and dusty, and my candle flared and made the shadows cower and quiver. The echoes rang up and down the spiral staircase, and a shadow came sweeping up after me, and another fled before me into the darkness overhead. I came to the wide landing and stopped there for a moment listening to a rustling that I fancied I heard creeping behind me, and then, satisfied of the absolute silence, pushed open the unwilling baize-covered door and stood in the silent corridor.

The effect was scarcely what I expected, for the moonlight, coming in by the great window on the grand staircase, picked out everything in vivid black shadow or reticulated silvery illumination. Everything seemed in its proper position; the house might have been deserted on the yesterday instead of twelve months ago. There were candles in the sockets of the sconces, and whatever dust had gathered on the carpets or upon the polished flooring was distributed so evenly as to be invisible in my candlelight. A waiting stillness was over everything. I was about to advance, and stopped abruptly. A bronze group stood upon the landing hidden from me by a corner of the wall; but its shadow fell with marvelous distinctness upon the white paneling, and gave me the impression of some one crouching to waylay me. The thing jumped upon my attention suddenly. I stood rigid for half a moment, perhaps. Then, with my hand in the pocket that held the revolver, I advanced, only to discover a Ganymede and Eagle, glistening in the moonlight. That incident for a time restored my nerve, and a dim porcelain Chinaman on a buhl table, whose head rocked as I passed, scarcely startled me.

The door of the Red Room and the steps up to it were in a shadowy corner. I moved my candle from side to side in order to see clearly the nature of the recess in which I stood, before opening the door. Here it was, thought I, that my predecessor was found, and the memory of that story gave me a sudden twinge of apprehension. I glanced over my shoulder at the black Ganymede in the moonlight, and opened the door of the Red Room rather hastily, with my face half turned to the pallid silence of the corridor.

I entered, closed the door behind me at once, turned the key I found in the lock within, and stood with the candle held aloft surveying the scene of my vigil, the great Red Room of Lorraine Castle, in which the young Duke had died; or rather in which he had begun his dying, for he had opened the door and fallen headlong down the steps I had just ascended. That had been the end of his vigil, of his gallant attempt to conquer the ghostly tradition of the place, and never, I thought, had apoplexy better served the ends of superstition. There were other and older stories that clung to the room, back to the half-incredible beginning of it all, the tale of a timid wife and the tragic end that came to her husband's jest of frightening her. And looking round that huge shadowy room with its black window bays, its recesses and alcoves, its dusty brown-red hangings and dark gigantic furniture, one could well understand the legends that had sprouted in its black corners, its germinating darknesses. My candle was a little tongue of light in the vastness of the chamber; its rays failed to pierce to the opposite end of the room, and left an ocean of dull red mystery and suggestion, sentinel shadows and watching darknesses beyond its island of light. And the stillness of desolation brooded over it all.

I must confess some impalpable quality of that ancient room disturbed me. I tried to fight the feeling down. I resolved to make a systematic examination of the place, and so, by leaving nothing to the imagination, dispel the fanciful suggestions of the obscurity before they obtained a hold upon me. After satisfying myself of the fastening of the door, I began to walk round the room, peering round each article of furniture, tucking up the valances of the bed and opening its curtains wide. In one place there was a distinct echo to my footsteps, the noises I made seemed so little that they enhanced rather than broke the silence of the place. I pulled up the blinds and examined the fastenings of the several windows. Attracted by the fall of a particle of dust, I leaned forward and looked up the blackness of the wide chimney. Then, trying to preserve my scientific attitude of mind, I walked round and began tapping the oak paneling for any secret opening, but I desisted before reaching the alcove. I saw my face in a mirror—white.

There were two big mirrors in the room, each with a pair of sconces bearing candles, and on the mantelshelf, too, were candles in china candlesticks. All these I lit one after the other. The fire was laid—an unexpected consideration from the old housekeeper—and I lit it, to keep down any disposition to shiver, and when it was burning well I stood round with my back to it and regarded the room again. I had pulled up a chintz-covered armchair and a table to form a kind of barricade before me. On this lay my revolver, ready to hand. My precise examination had done me a little good, but I still found the remoter darkness of the place and its perfect stillness too stimulating for the imagination. The echoing of the stir and crackling of the fire was no sort of comfort to me. The shadow in the alcove at the end of the room began to display that undefinable quality of a presence, that odd suggestion of a lurking living thing that comes so easily in silence and solitude. And to reassure myself, I walked with a candle into it and satisfied myself that there was nothing tangible there. I stood that candle upon the floor of the alcove and left it in that position.

By this time I was in a state of considerable nervous tension, although to my reason there was no adequate cause for my condition. My mind, however, was perfectly clear. I postulated quite unreservedly that nothing supernatural could happen, and to pass the time I began stringing some rhymes together, Ingoldsby fashion, concerning the original legend of the place. A few I spoke aloud, but the echoes were not pleasant. For the same reason I also abandoned, after a time, a conversation with myself upon the impossibility of ghosts and haunting. My mind reverted to the three old and distorted people downstairs, and I tried to keep it upon that topic.

The sombre reds and grays of the room troubled me; even with its seven candles the place was merely dim. The light in the alcove flaring in a draft, and the fire flickering, kept the shadows and penumbra perpetually shifting and stirring in a noiseless flighty dance. Casting about for a remedy, I recalled the wax candles I had seen in the corridor, and, with a slight effort, carrying a candle and leaving the door open, I walked out into the moonlight, and presently returned with as many as ten. These I put in the various knick-knacks of china with which the room was sparsely adorned, and lit and placed them where the shadows had lain deepest, some on the floor, some in the window recesses, arranging and rearranging them until at last my seventeen candles were so placed that not an inch of the room but had the direct light of at least one of them. It occurred to me that when the ghost came I could warn him not to trip over them. The room was now quite brightly illuminated. There was something very cheering and reassuring in these little silent streaming flames, and to notice their steady diminution of length offered me an occupation and gave me a reassuring sense of the passage of time.

Even with that, however, the brooding expectation of the vigil weighed heavily enough upon me. I stood watching the minute hand of my watch creep towards midnight.

Then something happened in the alcove. I did not see the candle go out, I simply turned and saw that the darkness was there, as one might start and see the unexpected presence of a stranger. The black shadow had sprung back to its place. "By Jove," said I aloud, recovering from my surprise, "that draft's a strong one;" and taking the matchbox from the table, I walked across the room in a leisurely manner to relight the corner again. My first match would not strike, and as I succeeded with the second, something seemed to blink on the wall before me. I turned my head involuntarily and saw that the two candles on the little table by the fireplace were extinguished. I rose at once to my feet.

"Odd," I said. "Did I do that myself in a flash of absent-mindedness?"

I walked back, relit one, and as I did so I saw the candle in the right sconce of one of the mirrors wink and go right out, and almost immediately its companion followed it. The flames vanished as if the wick had been suddenly nipped between a finger and thumb, leaving the wick neither glowing nor smoking, but black. While I stood gaping the candle at the foot of the bed went out, and the shadows seemed to take another step toward me.

"This won't do!" said I, and first one and then another candle on the mantelshelf followed.

"What's up?" I cried, with a queer high note getting into my voice somehow. At that the candle on the corner of the wardrobe went out, and the one I had relit in the alcove followed.

"Steady on!" I said, "those candles are wanted," speaking with a half-hysterical facetiousness, and scratching away at a match the while, "for the mantel candlesticks." My hands trembled so much that twice I missed the rough paper of the matchbox. As the mantel emerged from darkness again, two candles in the remoter end of the room were eclipsed. But with the same match I also relit the larger mirror candles, and those on the floor near the doorway, so that for the moment I seemed to gain on the extinctions. But then in a noiseless volley there vanished four lights at once in different corners of the room, and I struck another match in quivering haste, and stood hesitating whither to take it.

As I stood undecided, an invisible hand seemed to sweep out the two candles on the table. With a cry of terror I dashed at the alcove, then into the corner and then into the window, relighting three as two more vanished by the fireplace, and then, perceiving a better way, I dropped matches on the iron-bound deedbox in the corner, and caught up the bedroom candlestick. With this I avoided the delay of striking matches, but for all that the steady process of extinction went on, and the shadows I feared and fought against returned, and crept in upon me, first a step gained on this side of me, then on that. I was now almost frantic with the horror of the coming darkness, and my self-possession deserted me. I leaped panting from candle to candle in a vain struggle against that remorseless advance.

I bruised myself in the thigh against the table, I sent a chair headlong, I stumbled and fell and whisked the cloth from the table in my fall. My candle rolled away from me and I snatched another as I rose. Abruptly this was blown out as I swung it off the table by the wind of my sudden movement, and immediately the two remaining candles followed. But there was light still in the room, a red light, that streamed across the ceiling and staved off the shadows from me. The fire! Of course I could still thrust my candle between the bars and relight it!

I turned to where the flames were still dancing between the glowing coals and splashing red reflections upon the furniture; made two steps toward the grate, and incontinently the flames dwindled and vanished, the glow vanished, the reflections rushed together and disappeared, and as I thrust the candle between the bars darkness closed upon me like the shutting of an eye, wrapped about me in a stifling embrace, sealed my vision, and crushed the last vestiges of self-possession from my brain. And it was not only palpable darkness, but intolerable terror. The candle fell from my hands. I flung out my arms in a vain effort to thrust that ponderous blackness away from me, and lifting up my voice, screamed with all my might, once, twice, thrice. Then I think I must have staggered to my feet. I know I thought suddenly of the moonlit corridor, and with my head bowed and my arms over my face, made a stumbling run for the door.

But I had forgotten the exact position of the door, and I struck myself heavily against the corner of the bed. I staggered back, turned, and was either struck or struck myself against some other bulky furnishing. I have a vague memory of battering myself thus to and fro in the darkness, of a heavy blow at last upon my forehead, of a horrible sensation of falling that lasted an age, of my last frantic effort to keep my footing, and then I remember no more.

I opened my eyes in daylight. My head was roughly bandaged, and the man with the withered hand was watching my face. I looked about me trying to remember what had happened, and for a space I could not recollect. I rolled my eyes into the corner and saw the old woman, no longer abstracted, no longer terrible, pouring out some drops of medicine from a little blue phial into a glass. "Where am I?" I said. "I seem to remember you, and yet I can not remember who you are."

They told me then, and I heard of the haunted Red Room as one who hears a tale. "We found you at dawn," said he, "and there was blood on your forehead and lips."

I wondered that I had ever disliked him. The three of them in the daylight seemed commonplace old folk enough. The man with the green shade had his head bent as one who sleeps.

It was very slowly I recovered the memory of my experience. "You believe now," said the old man with the withered hand, "that the room is haunted?" He spoke no longer as one who greets an intruder, but as one who condoles with a friend.

"Yes," said I, "the room is haunted."

"And you have seen it. And we who have been here all our lives have never set eyes upon it. Because we have never dared. Tell us, is it truly the old earl who—"

"No," said I, "it is not."

"I told you so," said the old lady, with the glass in her hand. "It is his poor young countess who was frightened—"

"It is not," I said. "There is neither ghost of earl nor ghost of countess in that room; there is no ghost there at all, but worse, far worse, something impalpable—"

"Well?" they said.

"The worst of all the things that haunt poor mortal men," said I; "and that is, in all its nakedness—'Fear!' Fear that will not have light nor sound, that will not bear with reason, that deafens and darkens and overwhelms. It followed me through the corridor, it fought against me in the room—"

I stopped abruptly. There was an interval of silence. My hand went up to my bandages. "The candles went out one after another, and I fled—"

Then the man with the shade lifted his face sideways to see me and spoke.

"That is it," said he. "I knew that was it. A Power of Darkness. To put such a curse upon a home! It lurks there always. You can feel it even in the daytime, even of a bright summer's day, in the hangings, in the curtains, keeping behind you however you face about. In the dusk it creeps in the corridor and follows you, so that you dare not turn. It is even as you say. Fear itself is in that room. Black Fear... And there it will be ... so long as this house of sin endures."

BY RUDYARD KIPLING

Joseph Rudyard Kipling was born in Bombay in 1865. The grandson of a clergyman, both on his father's and mother's side, he was educated in England and served his apprenticeship as a writer on the newspapers in India. No man ever tried harder to convey to his reader the sensation and very pulse of life that he himself felt than did Kipling in his early work, of which "The Phantom 'Rickshaw" is a well-known example. Though he is undoubtedly one of the great writers of short stories, we are still too near him to be able to clearly appreciate his great talents.

THE PHANTOM 'RICKSHAW

By RUDYARD KIPLING

My doctor tells me that I need rest and change of air. It is not improbable that I shall get both ere long—rest that neither the red-coated messenger nor the midday gun can break, and change of air far beyond that which any homeward-bound steamer can give me. In the meantime, I am resolved to stay where I am; and, in flat defiance of my doctor's orders, to take all the world into my confidence. You shall learn for yourselves the precise nature of my malady; and shall, too, judge for yourselves whether any man born of woman on this weary earth was ever so tormented as I.

Speaking now as a condemned criminal might speak ere the drop-bolts are drawn, my story, wild and hideously improbable as it may appear, demands at least attention. That it will ever receive credence I utterly disbelieve. Two months ago I should have scouted as mad or drunk the man who had dared tell me the like. Two months ago I was the happiest man in India. To-day, from Peshawur to the sea, there is no one more wretched. My doctor and I are the only two who know this. His explanation is, that my brain, digestion, and eyesight are all slightly affected; giving rise to my frequent and persistent "delusions." Delusions, indeed! I call him a fool; but he attends me still with the same unwearied smile, the same bland professional manner, the same neatly trimmed red whiskers, till I begin to suspect that I am an ungrateful, evil-tempered invalid. But you shall judge for yourselves.

Three years ago it was my fortune—my great misfortune—to sail from Gravesend to Bombay, on return from long leave, with one Agnes Keith-Wessington, wife of an officer on the Bombay side. It does not in the least concern you to know what manner of woman she was. Be content with the knowledge that, ere the voyage had ended, both she and I were desperately and unreasonably in love with each other. Heaven knows that I can make the admission now without one particle of vanity. In matters of this sort there is always one who gives and another who accepts. From the first day of our ill-omened attachment, I was conscious that Agnes's passion was a stronger, a more dominant, and—if I may use the expression—a purer sentiment than mine. Whether she recognized the fact then, I do not know. Afterward it was bitterly plain to both of us.

Arrived at Bombay in the spring of the year, we went our respective ways, to meet no more for the next three or four months, when my leave and her love took us both to Simla. There we spent the season together; and there my fire of straw burned itself out to a pitiful end with the closing year. I attempt no excuse. I make no apology. Mrs. Wessington had given up much for my sake, and was prepared to give up all. From my own lips, in August, 1882, she learned that I was sick of her presence, tired of her company, and weary of the sound of her voice. Ninety-nine women out of a hundred would have wearied of me as I wearied of them; seventy-five of that number would have promptly avenged themselves by active and obtrusive flirtation with other men. Mrs. Wessington was the hundredth. On her neither my openly expressed aversion nor the cutting brutalities with which I garnished our interviews had the least effect.

"Jack, darling!" was her one eternal cuckoo cry, "I'm sure it's all a mistake—a hideous mistake; and we'll be good friends again some day. Please forgive me, Jack dear."

I was the offender, and I knew it. That knowledge transformed my pity into passive endurance, and, eventually, into blind hate—the same instinct, I suppose, which prompts a man to savagely stamp on the spider he has but half killed. And with this hate in my bosom the season of 1882 came to an end.