Title: The flying carpet

Editor: Cynthia Asquith

Release date: January 28, 2025 [eBook #75229]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1925

Credits: Richard Tonsing, Tim Lindell, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

Transcriber’s Note:

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

![[Colophon]](images/i_colophon.jpg)

| PAGE | ||

|---|---|---|

| THOMAS HARDY | ||

| A POPULAR PERSONAGE AT HOME | 9 | |

| ADELAIDE PHILLPOTTS | ||

| THOMAS HENRY TITT | 11 | |

| THEOPHANIA | 160 | |

| JOHN LEA | ||

| THE TWO SAILORS | 108 | |

| THE SIMPLE WAY | 198 | |

| ALFRED NOYES | ||

| INVITATION TO THE VOYAGE | 16 | |

| DESMOND MacCARTHY | ||

| I WISH I WERE A DOG | 18 | |

| A. A. MILNE | ||

| WHEN WE WERE VERY, VERY YOUNG | 32 | |

| DAVID CECIL | ||

| THE SHADOW LAND | 35 | |

| CYNTHIA ASQUITH | ||

| THE BARGAIN SHOP | 38 | |

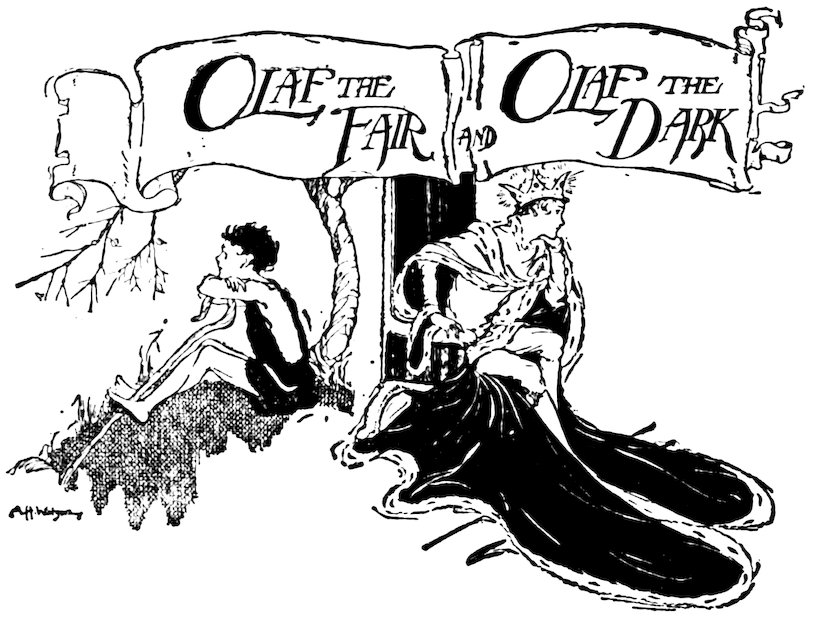

| OLAF THE FAIR AND OLAF THE DARK | 184 | |

| HENRY NEWBOLT | ||

| THE JOYOUS BALLAD OF THE PARSON AND THE BADGER | 54 | |

| VICE-VERSA: ANY FATHER TO ANY DAUGHTER | 118 | |

| SERMON TIME | 183 | |

| FINIS | 200 | |

| A. PEMBURY | ||

| THE SPARK | 158 | |

| THE RHYME OF CAPTAIN GALE | 182 | |

| G. K. CHESTERTON | ||

| TO ENID | 57 | |

| CHARLES WHIBLEY | ||

| SCENES IN THE LIFE OF A PRINCESS | 60 | |

| J. M. BARRIE | ||

| NEIL AND TINTINNABULUM | 65 | |

| HERBERT ASQUITH | ||

| STORIES | 15 | |

| THE DREAM | 96 | |

| EGGS | 107 | |

| ELIZABETH LOWNDES | ||

| MR. SNOOGLES | 99 | |

| HUGH LOFTING | ||

| DR. DOLITTLE MEETS A LONDONER IN PARIS | 110 | |

| MARGARET KENNEDY | ||

| KITTEEN | 120 | |

| CLEMENCE DANE | ||

| GILBERT | 122 | |

| HILAIRE BELLOC | ||

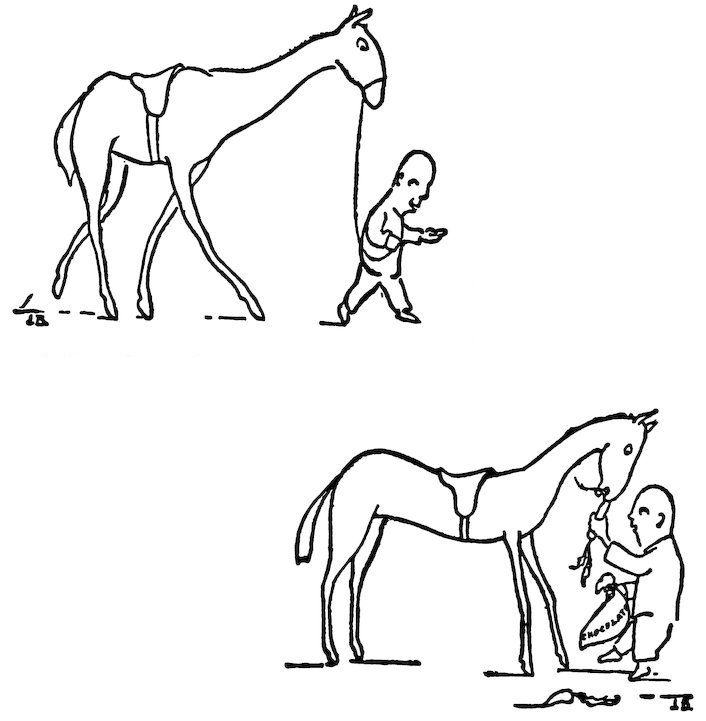

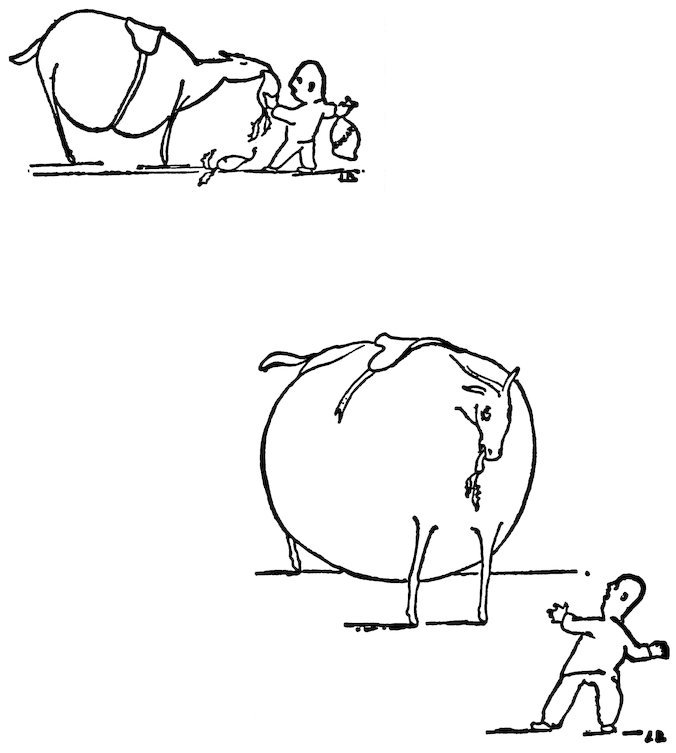

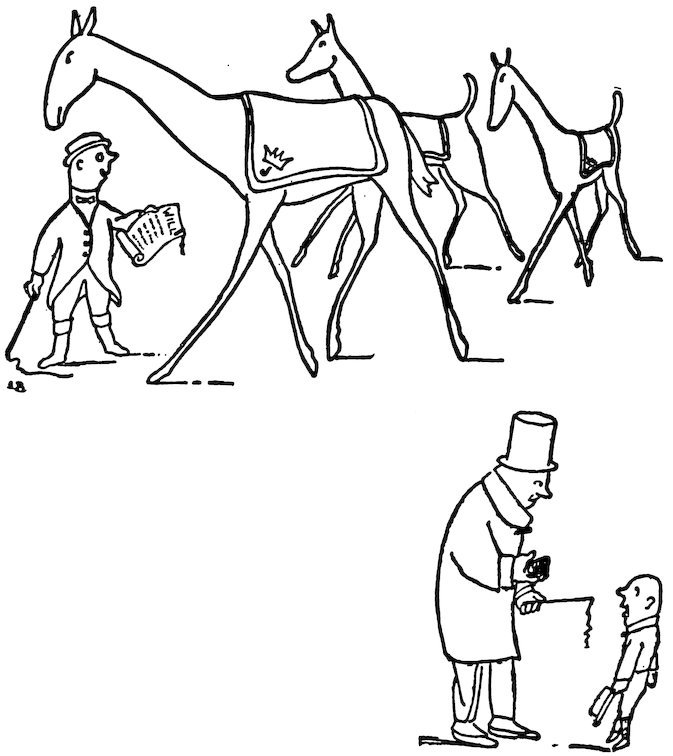

| JACK AND HIS PONY, TOM | 129 | |

| TOM AND HIS PONY, JACK | 131 | |

| WALTER DE LA MARE | ||

| PIGTAILS, LTD. | 133 | |

| SIR WALTER RALEIGH | ||

| THE PERFECT HOST | 157 | |

| EDWARD MARSH | ||

| THE WEASEL IN THE STOREROOM | 167 | |

| W. H. DAVIES | ||

| LOVE THE JEALOUS | 168 | |

| DENIS MACKAIL | ||

| THE MAGIC MEDICINE | 170 | |

In the South West of London stands a cathedral, which, from outside, looks like a child’s castle of bricks. But when you go inside you see nothing at first but a large emptiness—a ceiling somewhere up in the clouds supported by huge marble columns. There is always a smell of incense in the air, and there is a little painted figure before which, night and day, burn three rows of candles. Sometimes, on Saints’ Days, other rows of candles are lighted before other painted figures—St. Andrew, St. Patrick, St. George—making centres of bright light in the dimness of the great interior.

Near this cathedral are blocks of tenement buildings where families dwell, one on top of the other, like books in a bookcase. These buildings are full of children: boys and girls and babies.

On the top floor of one of these blocks lived Thomas Henry Titt, aged twelve. Thomas Henry’s father kept a shop round the corner where you saw sausages and onions frying in the window. His mother was dead. He had an elder sister who mended his clothes and helped their father in the shop. Thomas was known 12as Tom-Tit; and he looked rather like a bird, for he had thin arms and legs, sharp little eyes, a crest of bright hair, and a pointed nose.

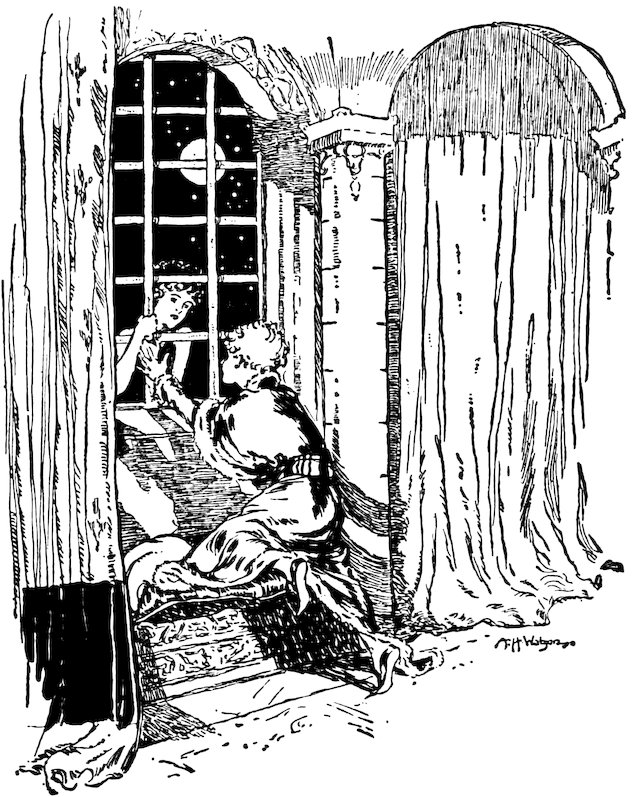

Like every imaginative child, Tom-Tit had a secret: a passion for the sea, which he had never seen. His ocean was in his mind’s eye, and he hoped as no one ever hoped before that one day he might behold the reality of his dream. In the darkness of night Tom-Tit, alone in his attic, lying awake on his mattress, gazed out upon a heaving cornflower-blue coloured ocean—as blue as the flowers which the woman sold at the end of his street. And this ocean was full of shining fishes. There was no land in sight—ever.

Thomas Henry Titt loved the candles that burned before the painted figure in the cathedral. In the winter, when he was small, he had often held his little frozen hands to the warmth of them, when nobody was looking. But as he grew older the candles began to have for him a deeper significance. During evening service he would creep into a corner by one of the pillars, listening to the organ and watching the kneeling people in the distance near the shining altar. Then, when the music stopped and the people were gone, he would steal out and patter along to the rows of candles. There his heart would light up, even as they, and he would thrill with a strange, unaccountable happiness.

Gradually Tom-Tit began to connect these candles with his desire for the sea. The two facts became one in his mind. It was as if, by the light of the former, he could see the blue waves of the other.

Underneath the rows of burning candles was a rack full of new ones. Tom often saw people drop a coin into a box, take one, fix it upon a spike among the rest, and light it. And a longing overcame him to possess for his own one of these new candles. Perhaps, at the bottom of his mind, was the idea that if he took 13it home and lighted it, it would bring him nearer to his ultimate ambition—to see the sea. He determined to realise his desire.

Then came a winter day when Tom-Tit’s head ached, shivers ran up and down his spine, and he felt very ill. Therefore his sister bade him stay in bed, and he did so until she had left the house with her father. But then, despite his fever, the craving to possess that candle overcame obedience. So, gripping a penny, he rose, staggered downstairs, and out into the road. The cold air cooled his body and numbed his pains. He slipped unnoticed into the cathedral and leaned for a moment against the wall, for his head was swimming and he could not see. Then he recovered, and his eyes sparkled as he beheld the candles flickering like golden flowers before the wooden figure at the end of the aisle. The surrounding air was a golden haze. The smell of incense was sweet.

He tottered to the box of new candles, dropped in his penny, and took one. Then he dragged himself home, feeling worse and worse at every step, but gloriously glad within, because of the candle in his pocket.

All day he lay on his bed, too ill to sit up, nursing his treasure. “I shall be well to-night,” he thought, “and when it’s dark I’ll light it.”

In the evening his father and sister returned, found him in a state of high fever, and sent for the doctor. He, when he saw Tom-Tit, said that he would come back in the morning and remove him to the hospital if he were not better.

He gave Tom a sleeping draught before he left.

When his father and sister had gone to bed, Thomas Henry, feeling drowsy and less hurt with pain, pulled out his candle half melted already by the heat of his hands, lit it, and set it on a chair by his side. Then he lay gazing at it, until the whole world was but a golden flame with a blue root.

14Then a wonderful thing happened. He did not see the candle any more. His first idea was that the wind must have blown it out, for a great wind was blowing. Where could he be? He opened his eyes, which must have been closed, and lo! he was in a little wooden boat on a cornflower-blue sea! The boat was rocking from side to side like the baby’s cradle on the floor below—a mechanical rock, rock, rock, rock, from side to side. He scooped up a handful of the sea, and, just as he had expected, it was bright blue. He could see blue shining fishes swimming round the boat, so he caught them in his fingers where they wriggled about and made blue reflections until he threw them back again into the blue water.

And all the time, though he could not see it, the candle was burning at his side—burning lower, and lower, and lower.

From horizon to horizon the cobalt ocean stretched around him—not a speck of land anywhere. He was perfectly happy there staring down through the blue fathoms and feeling the wind blow. He had never been so happy in his life before.

Then the candle went out.

In the morning they found a little pool of grease on the chair—and Tom-Tit was dead.

But this is not really a sad story, because Thomas Henry did what many thousands of people never do, even though they live to be a hundred and three—he realised his ambition. He saw the sea. And he was not disillusioned; for the sea that he saw was just as beautiful as the sea which he imagined: the reality matched the dream.

1. Robert Louis Stevenson.

There were five in the family and Dicky, nearly nine, was the youngest but one. Dicky’s father was a country doctor, and, like many country doctors, he led rather a hard life. The sick people he visited lived miles apart, and many were too poor to pay him properly.

Dr. Brook was a tall, pale man with grizzled hair turning to grey. He was clever, and he had a quick, short way of talking. He seemed to make up his mind about everything in a moment, and if you asked him a question, he answered as though it ought not to have been necessary to explain.

Dicky would have been surprised to hear that his father was a kind man, but kind he was. He hated attending upon well-to-do people who had nothing much the matter with them, though he knew he must visit them to make enough money to bring up his own children properly.

He would remember this while he was driving miles out of his way to see some poor cottager, and so, when he arrived at the cottage, he was usually in a bad temper. On the other hand, when he was calling on old Mrs. Varden at The Grange, who was sound as a bell and would probably live to be ninety, he was always thinking of those who really wanted looking after. Then, instead of smiling sympathetically, while she told him how queer she had felt in the middle of the night three weeks ago, or how well her nephews were doing, he would stand in front of the 19fire in her cosy sitting-room, look up at the ceiling with a stern expression, and rattle the keys in his pocket in a manner which said plainly, “How much longer shall I have to listen to this stuff?” So, although everybody thought Dr. Brook “a very clever doctor,” few people were fond of him.

All day he went bumping and rushing along the country lanes and roads in his shabby, muddy car, which he never had time to clean properly; and when he got home his day’s work was not over. In the evening he turned schoolmaster and taught his children.

Dicky’s mother had died when his brother Peregrin was born. Ella, the eldest of the children, a grown-up girl, kept house and taught Dicky and Peregrin in the morning. She was very like her father in many ways, only her cleverness had turned to music. She played the violin beautifully, and she was dying to get away from home and become a famous musician. Dr. Brook knew this and was very sorry for her; but he could not let her go till Dicky and Peregrin went to school. She had to be a governess till then. The other two boys had done very well. They had both got scholarships, and little Peregrin was as sharp as a needle.

Altogether the doctor had to admit he was very blessed in his children. But there was Dicky! Dicky was a dunce, there was no doubt about it—at least, so Ella reported. And when Dicky showed his smudgy exercise-books to his father in the evenings, his father thought it only too true.

Dicky dreaded the evening every day. He did not much mind his sister Ella’s crossness. He was used to it. But there was something awful about the weary quiet way his father used to ask, “Do you understand now?” Dicky had then to say “Yes,” and presently his father would find out he hadn’t understood at all. There would be a still longer pause, and at last his father would sigh, “Unhappy boy, what will become of you!”

20This was far worse than being slapped by Ella, though her ring sometimes really did hurt. His father would then repeat what he had said before, twice, very slowly, as though he were dropping the words drop by drop into a medicine glass, looking at Dicky all the time, till Dicky’s lips began to quiver and his eyes to fill, when his father would say hastily, pulling out his watch, “There, there. It’s time for bed. Run along. Kiss me.” Then Dicky’s one desire was to get out of the room before bursting into tears. He did not mind if it happened outside the door or upstairs. Indeed, it was rather a comfort to cry, especially if he could only get hold of Jasper, the black spaniel, to hug and talk to while he was crying. But he was terrified at breaking down before his father. He somehow felt if he did, he might never stop sobbing, or that something else dreadful would happen. One evening it did happen.

The day had been altogether a bad day. Dicky had got up that morning feeling as if his head was rather smaller and lighter than usual. It felt about the size of an apple. Ella had had a fat letter that morning from her bosom friend, at the Royal College of Music in London. Lessons were always worse on the days she heard from her, and that morning it was true also, for once in a way, that Dicky had really not been “trying.” He had begun by making thirty-four mistakes in his French dictation—and he was rather glad. During arithmetic he had amused himself by imagining that the numbers had different characters, and that some of them were very pleased to find themselves side by side in the sums. The result was that all his sums were wrong, and he had exasperated Ella by telling her that it was the fault of number 8, who was a quarrelsome widow and wore spectacles.

When left alone to do his Latin Prose, while Ella went to her bedroom to practise furiously on the fiddle, he had spent the time in teasing a beetle by hemming it in between canals of ink on the schoolroom table. He liked the beetle, but he enjoyed imagining 21its disgust and perplexity, and he enjoyed feeling that he could, but wouldn’t, drown it. When Ella came back and found that he had only written one Latin word, “Jam” (already), on the paper, she tore the exercise book from him and said that he could do what he liked: she would tell his father and never teach him again—never, never, never.

“SHE WOULD NEVER TEACH HIM AGAIN—NEVER, NEVER”

But the evening was a long way off, and Dicky walked into the garden, in a gloomy sort of way rather proud of himself. He found, however, he could not amuse himself, so he devoted himself to amusing Jasper, chasing him in circles about the lawn and throwing sticks for him to fetch. When the dog had had 22enough, and lay down on the grass with his paws out in front of him like a lion, Dicky did not know what to do next. He went down himself on all fours and kissed Jasper, who responded, between quick pants, with a hasty slobber of his pink quivering tongue, as though he were snapping at a fly. Ah, if only he were as happy as Jasper! Dicky suddenly remembered that an old gentleman had once given him a sort of blessing, saying, “May you be as happy as a good dog.” What an easy time Jasper had! Of course he got into trouble if he rolled in things, but if Dicky were in his shoes—or perhaps he ought to say on his paws—he wouldn’t want to. (Jasper certainly had a very odd taste in scent.) Examinations, scholarships—those awful things meant nothing to him. Dicky thought he could have easily managed to be a good dog. And since he wanted to stop thinking about himself, he began to play a favourite game of imagining what Jasper said to other dogs about his home and the family. How he would boast to them of the excellent rabbit-hunting in the copse near by, of the good bones he had and the warm fires; and how he would tell them about jumping on Dick’s bed in the morning and how perfectly Dick and he understood each other. But the worst of it was that unless one were tired and a little sleepy, one could not go on with that game very long. It soon began to seem silly. It was not a good morning game.

Ella was very grim at lunch and only spoke to Peregrin. After luncheon Dicky felt very inclined to work—anything to stop thinking. He said something about learning grammar, but Ella took all the books away and locked them up. She said he could do whatever he liked. This had never happened before and it frightened him.

He went for a walk by himself. The sky was grey and the hedges were dripping and his feet felt heavy. He actually tried to remember what cases the different prepositions governed in Latin, 23as he walked along, in the hope of surprising his father in the evening; but the fear that he might be repeating them to himself all wrong made him hopeless. It was never safe to learn without the book. Only once, when a red stoat ambled with arched back across the lane, did he forget himself. A stoat, too, must have a jolly life, he thought, even if it ended by being nailed up on a door by a keeper. He stayed out till it was dark and past tea time.

His father’s hat and coat were not in the hall when he returned, so Dicky knew he had not yet come back. Upstairs he could hear the wailing of Ella’s violin. He went up and knocked at her door. She did not say “Come in,” or stop bowing away or frowning at the music on the stand in front of her. “If you’re hungry get milk in the kitchen,” she said, her chin still on the fiddle, “and—shut the door.”

Dicky did so, and stood for a minute outside it. Then he went slowly to the schoolroom and sat down at the table. Peregrin was already in bed, and there was nothing to do but to wait.

Time passed very slowly, and if Dicky had not known that he was dreading something, he would have thought he must be ill. He did, indeed, feel very queer. At last he heard the front door slam and the tramp of his father’s stride in the hall. The same instant the sound of the violin stopped and Ella walked rapidly along the passage; and before Dicky knew what he was doing he had started to run after her. At the head of the stairs he stopped himself, and peeping over the bannisters he saw that his father had hesitated in the middle of pulling off his coat, and was staring at Ella, who was talking vehemently in front of him. Dicky heard her raised voice saying, “It is hopeless. Father, I won’t; I really can’t. He....” His father finished getting out of his coat without a word; then they both went into the study. The door closed behind them, and Dicky crept back to the schoolroom.

24Presently, he heard Ella calling him to come down. A few minutes before, his legs had carried him to the top of the stairs without his wanting it, now they refused to move. “Father wants you in the study at once,” she shouted, and she continued to call, “Dick, Dick, Dick, Dick.” There was a long pause and Ella herself stood in the doorway.

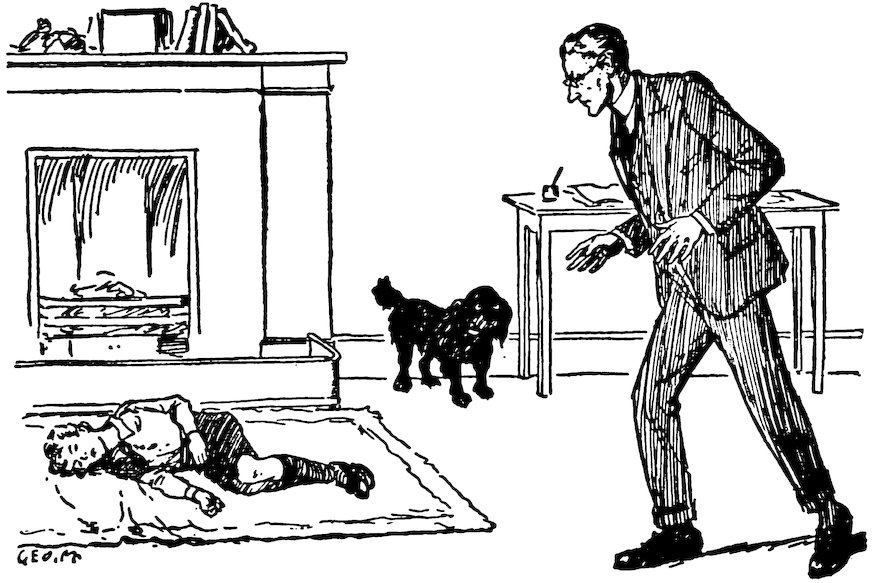

“Father is coming to whip you,” she said, and walked off to her room.

But he did not come. Dicky waited with beating heart, but he did not come. He waited till he almost forgot he was waiting, and yet his father did not come. And when at last he heard soft shuffling steps coming along the passage, his heart almost stopped. To his astonishment he saw in the darkness beyond the door two small round orange lamps shining about a foot from the ground. It was only Jasper, who padded quietly into the room and lay down on the hearthrug with a quiet sigh of satisfaction. Having settled himself in the shape of a large foot-stool, Jasper did not lift his nose again, but he turned up his eyes at Dicky—they were brown eyes now, exquisitely humble and kind—and wagged his stumpy tail. Dicky had flung himself on the floor beside the dog and embraced him. Were these the terrible sobs which would never leave off? No, presently they did stop; and gradually Dicky even forgot that he was waiting for something awful. The occasional dab of the dog’s cold nose on his hot cheeks was comforting, and so it was to curl all round him. Dicky felt almost as though he were a dog himself when he was curled up like that.

“Do you know, Jasper, if I were a dog, I should be a very clever dog? Much, much cleverer than you,” he whispered with his face buried in the black fur. His head felt swollen and confused. “A re-markable dog,” he repeated, “I should be a very re-markable dog.”

Downstairs Dr. Brook was sitting close up to the fire and 25staring gloomily into it. He had forgotten that he held a short switch in his hand, and that it still hung down between his knees. He was thinking in pictures and the pictures were not of Dicky. He had forgotten Dicky; he had even forgotten himself. They say the whole of life passes before a drowning man’s eyes. The doctor ever since he sat down had felt like a man drowning in a sea of troubles. If not the whole of his own life, still, much of it, had passed before his eyes. Only when at last he was eating his cold solitary dinner in the dining-room, did he remember again that Dicky had been naughty that morning, and that Dicky was probably incurably stupid. But even if he were it did not seem now to matter much, or to matter in a different way. Ella, too, he thought, must go to her College of Music; things could somehow be managed. The doctor sat a very long time over his dinner.

But upstairs still stranger things were happening to Dick. First he felt hot and large, then cold and small. He kept on shivering. Was this silky hair his own or Jasper’s? And where was he? He was apparently in a wet, grey place. What he touched with his hands and feet felt rough and gritty. Suddenly he saw a brown stoat with an arched back ambling rapidly in front of him—it was as big as a fox. Yes, he was on a road—the very road he had walked along that very afternoon, only now the wet hedges were ever so much higher. And before Dicky knew what he was doing he was dashing after the stoat, right into the quickset hedge after it. What was he doing? He smelt a queer strong smell which excited him; and he pushed and struggled through the roots and thorns, following the smell. He seemed, too, to be wearing a very odd cap with long flaps, which kept catching in the brambles and dragging him back. This did not hurt, but it was a nuisance, and he had constantly to shake his head. He traced the smell of stoat to a rabbit hole and thrust his head down it. Hullo! Dicky had no idea rabbits smelt so deliciously, as nice as pineapples 26or peaches! Dicky had wanted to kill the stoat, but he would have liked to eat the rabbit. He tried to make the hole larger, by tearing away the earth with his hands, but, although he got on much faster than he expected, he soon saw that was no use; and dragging himself violently backwards out of the hedge, he found himself in the road again with nothing to do.

Yes, there was nothing, absolutely nothing to do. The sensation was a strange one, for he couldn’t even think of anything. He just stood there snuffing the wet wind. Then suddenly he found himself trotting towards home. He had not gone very far when he was aware of another smell which he somehow recognised instantly as “The Sacred Smell.” He knew what it was, though he had never smelt it properly before. It reminded him of a feeling he had sometimes had in church—how long ago that seemed!—and partly of a feeling he had had when once an old general in scarlet and covered with medals had patted him on the head. Only this time The Sacred Smell was mixed with other smells; with smells of horse, leather, onions and smoke. This, Dicky knew, was not as it should be, and he was distinctly alarmed. However, he thought he had better stand still. It was always better, something whispered to him, not to run away from The Sacred Smell—unless the danger was terrific.

Of course, having smelt The Sacred Smell, he was not at all surprised to see next a huge pair of muddy boots coming towards him, and a pair of huge knees in dirty trousers moving up and down. When they were a short distance off, they stopped; and Dicky, looking up, saw what he had expected; an unshaven, dark-skinned Man in a cap, with a spotted handkerchief knotted round his neck. The Man made a squeaking noise with his pursed-up lips, such as rats make, and slapped his thigh once or twice. Dicky knew what this meant, but even when the Man called in a croaking voice, “E-e-e-’ere good boy,” Dicky still thought it was 27best not to move. He stood and turned his face instead to the hedge, looking, no doubt, as absent-minded and miserable as he felt. (It was odd, but now when Dicky felt wretched and miserable that feeling was strongest, not just under the middle of his ribs, but at the end of his spine where his legs began; there now was the seat of anguish.) The Man took a step or two nearer, then another step. Still Dicky did not stir. Suddenly the Man dashed forward and made a grab at him. Dicky ducked, started aside and bumped right into the road-bank. He saw the Man’s hand outstretched above him, and he knew there was now only one thing to do: to roll right over on to his back, in order to show he wouldn’t resist and hoped for mercy. The Man stroked Dicky’s head and made soothing noises; and then, suddenly, put an arm under him, lifting him up and holding him tight to his side.

“THE MAN DASHED FORWARD AND MADE A GRAB AT HIM”

28Dicky felt perfectly miserable, but what could he do? He knew it would be folly to try to escape, and that it would be wiser to wait for an opportunity. The Man tucked him with a jerk still more firmly under his arm, and started to walk slowly on. He walked on for more than an hour, till they came to a gorse common, where a caravan was standing with empty shafts and a pair of steps behind. Gripping Dicky tighter than ever the Man gave a whistle, and a Woman came out of the caravan.

“Where did you find him, Joe?” said the Woman, looking at Dicky.

“’Long road,” said the Man, jerking his head backwards.

“You ain’t been and thrown away his collar, ’ave you, Joe?”

“’Adn’t any,” said the Man. Dicky was very dazed, but he did think they were talking about him in an odd way.

“Better take ’im where he belongs,” said the Woman. “The cops won’t believe as such as ’e is ours. He looks well cared for. Might get five bob.”

Dicky did not try to tell them where he lived; he felt somehow it would be no use to try.

Instead of answering the Man just threw him into the caravan and shut the door. Although it was nearly dark, Dicky found he could see surprisingly well. Presently a tin bowl full of scraps of meat and bones was thrust in. Dicky would have been revolted by such a mess a short time ago, but now, though he was too scared to feel hungry, he could not resist putting his face close to it and giving a sniff. It really smelt uncommonly good. He put out the tip of his tongue and touched a brown-looking, ragged bit of gristle. Yes, it was good. Then all of a sudden he understood what must have happened. He had changed into a dog! Into a black spaniel!

He dashed at the door, shouting at the top of his voice, “Let me out! Let me out!” Alas, the only word which sounded 29at all like what he wanted to say was, “Out.” “Out, out, out, out,” he kept barking, hoping that the Man and Woman would understand. They took no notice; but he could not stop. “Out, out, out,” he barked. He shook the door by jumping at it; he tore at the wood with his nails. There was a latch just within his reach when he sprang up, but his paws—yes, it was only too true, his hands were round, black and feathery—could not lift it. “Out, out, out.” No answer. At last he gave it up, and lay down on the floor, feeling very tired. It occurred to him presently that he might think better while gnawing a bone. So he went to the bowl and pulled out the largest. It was a slight comfort to him. With his head on one side and his teeth sliding along the bone, he found he could think a little more calmly. How was he to let them know that he was not a real dog, but a boy called Dicky Brook? He tried again to talk. After a lot of practice he succeeded in making a sound rather like “Brrr-ook,” but it was also too sadly like the noise Jasper made when he was too lazy to bark or had been told to stop barking. Dicky was afraid they would never understand. But surely a very clever dog could make people understand somehow?

At last the door opened and the Man appeared, black against the starry sky. He stumbled over Dicky, swore and lit a stinking lamp-flame the size of the blade of a pocket knife. He was followed by the Woman. Outside Dicky could see the red glow of the fire which had cooked their dinner. Now was his chance. What should he do to astonish them? That was the first thing to do, to astonish them till they began to understand. But all Dicky could think of was a doggy thing after all: he sat up and begged. The Woman grinned at him, but the Man, who was pulling off his great boots, flung one at him, which Dicky dodged. He at once sat up on his hind-legs again, this time joining his paws and holding them up high in front of him.

30“Bli’my Joe, look at the dawg!” exclaimed the Woman. “It’s saying its prayers!”

The Man, too, stared in astonishment.

“I don’t like it,” said the Woman.

Dicky felt greatly encouraged. At home he was fond of turning somersaults. Now, down went his head and over went his hind-legs. It was not a good somersault (he was too short in the legs for somersaults now) but it was one. The Man gave a shout of laughter, and his face lit up with joy and cunning.

“S’truth, it’s a performing dawg! I ain’t taking ’im back, no fear. He’ll make our fortunes.”

At these words Dicky saw he had made a terrible mistake. If he was a dog, he had better not be a re-markable dog.

“HE COULD NOT FALL ANY FURTHER”

31The door was still open, and through it he dashed, taking the steps at a leap. Now he was falling, falling, falling. What a height! Oh, would he never reach the bottom? Stars were flying above him like bees. The awful thing was that he was beginning to fall slowly, while a huge arm with a hand at the end of it was stretching out, longer and longer, after him. He was not even falling slowly now; he was floating. He tried to force himself down through the air, but though there was nothing to keep him up he could not fall any further. Suddenly the arm gripped him. In an agony of terror he yelled: “I’m not a dog.” He heard his own voice, and, to his amazement, he saw his father’s face close to his; it was his father’s arm lifting him from the hearthrug. He felt a hand cool on his forehead. “Dick, you’re feverish. My little Dick.” His father’s voice had never sounded like that before, and he felt himself being carried—deliciously safe—to bed.

“After all,” he said to himself, as he snuggled down, “I’m glad I’m not a dog.”

WILDER YET THE SHADOWS WHIRL

Once upon a time there lived a man called Anselm, who used several times an hour to stamp his foot and cry out: “I must be rich! I must be rich!” He was married to the most beautiful woman he had ever seen, and, since he had enough to eat and a weatherproof house, and had neither aches nor pains, he should have been happy for 365 days in each year. But his unceasing longing for great wealth spoilt everything, and even on fine days he went about looking as discontented as though he were hungry.

As for his wife, Jasmine, she had long red-gold hair and great green eyes set wide apart in her flower-like face, and she possessed a mirror in which she could see her shimmering loveliness. So she ought to have been very happy and very grateful. She was so beautiful that when she walked abroad, men would lean far out of their windows to watch her pass and then wonder why their own wives and daughters should look so much like suet puddings.

But, though you will scarcely believe it, Jasmine was quite 39as discontented as her husband, and pouted and sighed through the days.

For she, too, was consumed by this perpetual craving for riches. Whether she had caught this uncomfortable sort of illness from her husband, or whether she had given it to him, I do not know, but there they were both wasting their youth, their beauty, and their love for one another, in foolish, petulant longing.

Whenever Jasmine saw other women clad in rich raiment and adorned with jewels, envy would blight her loveliness as frost blights a flower.

“Of what use is my beauty if I cannot adorn it?” she cried. “I must have pearls—ropes of pearls, crowns of glittering diamonds, emeralds, rubies, and sapphires!”

“Yes,” said Anselm, “and I must have a hundred horses, a thousand slaves, and fountains that spout forth wines!”

One day, as Jasmine walked sadly through a deep, dark forest she suddenly saw a very strange looking house moving slowly towards her. The roof of the house was most beautifully thatched with brightly-coloured feathers, and across its face in rainbow letters ran the queer inscription:

“Money for sale?” read the wondering Jasmine. “What can this mean? Some foolish jest, no doubt.”

Three times the house sped round her; then it quivered and stood still. She stared at the glass door that held a myriad reflections of herself. As though her gaze had power to push, it slowly opened. She now saw into a vast hall, and heard 40a gentle but compelling voice say: “Come in.” Trembling, Jasmine walked through the door. The light was dim and flickering as though from a fire, but no fireplace could be seen. Across the whole length of the hall ran a counter, such as you see in large shops, and behind this counter there rose up a wall made of rows of boxes piled high the one upon the other, and on these boxes were rainbow letters and figures. Between the boxes and the counter there stood a tall, sweetly-smiling woman, whose face, though unrecognisable, seemed somehow familiar to Jasmine.

“I was expecting you, beautiful Jasmine,” spoke the stranger in a voice that was soft but decided, like the fall of snow. “You would buy money, would you not?”

“Can one buy money?” faltered Jasmine. “Save with money, and, alas! I have none.”

“Though you were penniless, yet from me you could purchase boundless wealth,” replied the stranger. “Behold, a purse,” she continued, holding up a red-tasselled bag, “which, spend as you may, will always contain one thousand golden guineas. This purse is yours if in exchange you will give me one part of yourself.”

“A part of myself?” gasped the astonished Jasmine. “What would you have? My hair?”

“No,” smiled the woman. “Lovely as are your tresses, in time they would grow again, and no one may own unlimited wealth and pay no price therefor. Your beauty shall remain untouched. It is your Sense of Humour that I require.”

“My Sense of Humour?” laughed Jasmine. “Is that all? Just that part of me which makes me laugh? Humour? What was it my mother used to call Humour? I remember—she said it was Man’s consolation sent to him by God in sign of peace. God’s rainbow in our minds. But with boundless wealth what need of consolation shall I have? Besides, I have often been told 41I had but little Sense of Humour. The more gladly will I give it to you. The purse, I pray,” and Jasmine held out both her trembling hands.

“Stay a while,” said the solemn, smiling woman. “I must warn you of two conditions. First, I would have you know, the money this purse yields can be spent only upon yourself. Would you still have it?”

“Yes! Yes! Yes!” clamoured Jasmine.

“I must also tell you that should you ever repent of your bargain and wish to buy back the precious sense you sell, it will, alas, not be in my power to help you. I can never buy back from the person to whom I have sold. The only chance of recovering your Sense of Humour is, that another customer, unasked by you, should buy it back with a similar purse, and I warn you that it may be hard to find anyone willing to give up boundless wealth for the sake of your laughter.”

“What matter?” exclaimed Jasmine. “Never, never shall I wish to return my purse.”

“You are determined?” asked the strange saleswoman.

“Yes, yes, yes!”

“Hold out your arms, then.”

Eagerly Jasmine stretched out her arms.

The smiling woman touched her on both her funny-bones, drew forth her Sense of Humour, laid it away in a box, on which she wrote Jasmine’s name, and the date, and then placed it on a shelf between two other boxes.

“Now it is mine, until redeemed by the return of a purse, fellow to this that I give thee,” said the woman, handing the tasselled red bag to Jasmine. “And while it is in my careful keeping, this despised sense of yours will grow and grow. Farewell, Jasmine. Leave me now and go forth into a bleak world.”

42Clasping the marvellous purse to her heart, Jasmine fled from the house and hastened through the deep, dark forest till she reached the city. At once she went to the great jewel-merchants, against whose windows she had often pressed her face in wistful longing.

“I want the biggest pearl necklace you have got,” she cried, breathlessly bursting into the gorgeous showroom.

“I’m afraid goods of such value can only be supplied in exchange for ready money,” said the merchant with an uncivil smile.

“How much?” asked Jasmine.

43“Seven thousand guineas.”

Jasmine opened the purse and holding it upside down, shook it. Glittering guineas poured out in a golden stream, but the purse remained just as full as before.

As the clinking coins bounded and rolled the merchant’s eyes grew rounder and rounder, and he had to shout for six small black slaves to come to help him to count the money, now lying scattered all over his shop. With the lowest bow he had ever bowed he handed the long rope of glistening pearls to Jasmine. Feverishly she clasped them round her throat, where they scarcely showed against the whiteness of her skin. They reached down to her knees.

“Now some emerald ear-rings, a crown of diamonds, ten ruby bracelets for each arm, and all the opals you possess!” ordered Jasmine, scattering guineas as she spoke, and putting on all the jewels as fast as they were produced.

At last she went away, hung with jewels as a Christmas tree is hung with ornaments. Proud as a peacock she strutted through the streets, and everyone laughed at the absurd sight of so many gaudy ornaments crowded on to one ordinary-sized woman. She heard titters and wondered what might be the cause of the laughter.

She now went to the grandest Fashion House in the city, ordered one thousand costly garments, and came out wearing the richest raiment she had found in stock. Next she bought a most magnificent coach, made of mother o’ pearl, and sixteen piebald horses to draw it; and then she engaged an enormous coachman with a face gilt to match his golden livery.

On her way home she stopped at seven merchants to buy all manner of rare and costly foods, and before long the great coach was crammed with dainties. In it were piled every fruit and vegetable that happened to be then out of season, bottles of wonderful wine, jars of caviare, pots of roseleaf jam, tiny birds in aspic, 44and sugar plums of every colour. Last of all—because it looked so grand and expensive—she bought an immense wedding-cake, sixteen stories high. The confectioners laughed. They seemed to think it funny that she should buy the wedding-cake. She wondered why they were amused.

When Anselm saw his wife stagger into the room, swaying beneath the weight of so many gaudy jewels, thinking them to be all sham and worn in jest, he burst into a great roar of laughter.

Annoyed at his merriment, Jasmine told him breathlessly of the marvellous purse. Her husband laughed and laughed, partly at her story, partly at her absurd appearance. He laughed until he got hiccoughs.

“Oh, how funny! How funny! What has come over you?” he cried, rolling on the floor.

“This is no jest, Anselm, I swear; it is the solemn truth. Just look inside and you will see all the golden coins.”

Incredulously Anselm peered into the bulging purse. He rubbed his eyes. Slowly his unbelief gave way to amazed joy.

“Praise be to God!” he cried at last. “We’re rich, rich, rich beyond the dreams of man. Give it to me that I may go and buy gorgeous apparel, fine horses, and rarest wines.” Feverishly he snatched the purse from his wife’s hand.

“What’s this?” he cried. “I knew it was some trickery. Your precious purse is as empty as an egg that has been eaten.” And in truth, the tasselled bag now dangled from his hand flat and light as a leaf.

“Oh!” screamed Jasmine, in dismay, “give it back to me!” No sooner had she touched the purse than once more it became rounded and heavy with the weight of a thousand guineas.

“Praise be to God!” she sighed. “I remember now. The woman from whom I bought it warned me that the guineas were only for my own use.”

45“Tut, tut, that’s very troublesome,” said Anselm ruefully. “But what matter? You will be able to buy gifts for me. It will come to the same thing. But, wife, what mean you when you say you bought the purse? With what can one buy money?”

Jasmine told him of the weird house, the mysterious saleswoman and the strange bargain she had driven.

“Your Sense of Humour?” cried Anselm. “Your Sense of Humour! Well, she didn’t get much for her money, did she? Ha! ha! ha!”

With grave eyes Jasmine stared at her husband, offended at his display of merriment.

Then she said: “You little guess what a banquet I have prepared for you. Come now and I will show you how I have ransacked the city for its choicest dainties. Let us now feast.” Together they entered the dining-hall and at sight of the gorgeous banquet spread before them Anselm smacked his lips and promised himself great delight.

But bitter disappointment awaited him. For, no sooner did he touch the iced grape-fruit with which he intended to begin his feast, than, behold, it shrivelled in his hand, and became an empty rind. With an oath he stretched out his hand to grasp a goblet of purple wine. It broke in his hand, and of the rich vintage nothing remained but a stain on the damask tablecloth.

“Alas!” cried Jasmine. “It seems that with the magic gold I may buy nothing for your use!”

In truth, everything that poor Anselm touched, before it reached his eager lips, disappeared like a bubble that has burst. In nothing that had been purchased with the magic gold could he share. For him, all the rich viands were spread in vain, and finally, he was obliged to fall back on their accustomed fare of bread and cheese and last Friday’s mutton.

“’Tis funny to watch one’s wife quaffing the wines one 46dreams of and to be on prison-fare oneself,” laughed Anselm, trying to make the best of things.

“Funny?” asked his wife. “Why is it funny? I think it is very sad. These humming birds and this sparkling juice of the grape are most delicious.”

To keep up his spirits Anselm, who was famed for his wit, cracked many jokes, but no smile ever lifted the corners of Jasmine’s perfect mouth; no twinkle appeared in the depth of her great green eyes. Discouraged at last, Anselm fell into silent sulks, whilst his wife continued to eat and drink, until a stitch came in both her sides.

Days passed. Every evening, Jasmine, clad in new raiment and gorgeous jewels, regaled herself with rich dainties.

“Alas, husband!” she cried one night, “I have no pleasure in feasting that you cannot share.”

“In truth, this is no life!” angrily exclaimed Anselm. “To sit at a banquet one may not taste with a wife who cannot see one’s jokes. I can bear it no longer. Why should not I seek this strange woman and make the same bargain? If husband and wife may not share their jokes, they must at least share their dinner. Tell me quickly where I may find this ‘Bargain House.’”

Jasmine told her husband the way through the deep, dark forest, and early the next morning he set forth in search of the mysterious building. An hour’s walking brought him within sight of just such a house as his wife had described. It moved nearer, sped three times around him and then stood still. As he stared at it, the door slowly opened, the gentle, commanding voice bade him enter, and there stood the tall, smiling woman of his wife’s description.

“Good morning, Anselm,” she said, in the voice that was soft like the fall of snow. “Would you have a purse that shall always bear a thousand guineas?”

47“Indeed I would!” cried Anselm. “Have you one for me?”

“Yes, if you consent to my terms.”

“What is it that you want? My Sense of Humour? Of what use is it to me now? I will gladly part with it.”

“No,” said the woman. “’Tis not your Sense of Humour I require of you, it is your Sense of Beauty.”

“Take what you will from me,” cried Anselm. “I care not so I have one of those wondrous purses.”

“Listen first, Anselm,” said the woman, and solemnly, as she had warned Jasmine, so she warned him that the magic money could be spent on none save himself, and that the sense he sold could be bought back only by the owner of such another purse.

“Remember, you can never reclaim it yourself,” she repeated.

“I care not! I care not!” exclaimed Anselm. “Quick, the purse!”

“Come hither,” said the woman, “and close your eyes.” Gently she touched him on both eyelids, and drew forth his Sense of Beauty. Then she handed him a red-tasselled bag exactly the same as Jasmine’s and as heavy with golden guineas.

“Now farewell, Anselm. Go forth into a bleak world.”

Wild with joy and excitement, Anselm dashed from the Bargain House and hastened through the deep, dark forest to that part of the city where dwelt the grandest merchants. Here he bought gorgeous apparel, costly wines, and magnificent horses. Astride the finest of the horses, a gleaming chestnut, said to be the swiftest steed alive, he then rode home through the forest. As he went, he met an old man clad in wretched rags, who looked very hungry and tired. Feeling pleased with life Anselm plunged his hand into the magic purse, and, drawing forth a golden guinea, flung it at the poor man, who joyfully stooped to pick it up. But 48no sooner had his hand touched the coin than it vanished. Anselm remembered the woman’s warning.

“ANSELM DREW FORTH A GOLDEN GUINEA”

“Sorry, my good fellow,” he said, shamefacedly handing the beggar two coppers—all that he could find in his old purse.

“Thanks, noble master. Now I can buy bread for my supper. I never thought to eat to-night.”

“For one who sups on dry bread you look strangely cheerful,” said Anselm. “At what can you rejoice?”

“’Tis the beauty of the sunset, master. It seems to warm my heart. Never have I seen one like to it in glory. Who could look and not be comforted?”

And, in truth, a radiant smile lit up the old man’s suffering 49face as he gazed on the flaming splendours of the western sky. Anselm turned and looked where the beggar pointed, but he could see nothing that seemed worth the turning of the head, and with a shrug of the shoulders he rode home.

Now Jasmine, rejoicing that Anselm would share her feasting, arrayed herself that she might look her fairest for their banquet. She brushed her red-gold hair until it shone, and gazed at herself in the mirror until her beauty glowed. Then she attired herself in a dress of dragon-flies’ wings, covered all over with hearts made of tiny little diamonds like dewdrops.

“Never, never have I looked so fair. When Anselm sees me he will love me more than ever. How joyfully we shall feast together, and how glad am I that he will no longer want me to laugh at the things he says! I shall love him far more without his Sense of Humour.”

Her heart beat as she heard footsteps hastening up the stairs. Radiant with excitement in burst Anselm. “I’m rich!” he cried. “Rich! rich! Rejoice with me, Jasmine.”

Grey disappointment crushed into Jasmine’s heart, for not one word did her husband say of her especial beauty or her wonderful dress.

“There’s nothing like wealth!” he cried. “How did we ever endure our poverty? And fancy, I met a beggar-man, who said he was cheerful because he looked at the sunset! Ha! ha! ha!”

“Why do you laugh, Anselm? Have you then not sold your Sense of Humour? How came you then by that purse?”

“No. I may still laugh. I have but parted with my Sense of Beauty.”

“Your Sense of Beauty?” echoed Jasmine, icy fear entering her heart. “Is that why your eyes no longer seek my face?”

“Why ever do you look so doleful?” laughed Anselm. “Let us hasten down and feast. My lips thirst for the wines I have bought.”

50Trembling, Jasmine pleaded: “Look on my face, husband, the face you have so often called your glory. What think you of my face to-night?”

“Your face? Let me look. It seems all right: two eyes, one nose, one mouth. Yes, it seems just as other faces are.”

It was with a sad heart poor Jasmine sat at the feast that night. Loving her husband, she rejoiced to see him revel, but that he should no longer gaze at her with the admiration which had been her delight was pain past bearing. Anselm enjoyed his feasting, but the wine made jokes rise in his mind, to flutter from his lips, and it vexed him that no smile ever widened his wife’s mouth, set for ever in still solemnity.

Days, weeks, months passed. Anselm and Jasmine now lived in a gorgeous palace. They were clad in the finest raiment and they feasted like emperors, but in their hearts all was becoming as dust and ashes.

“Ah me!” sighed Jasmine. “I know now why it was that I longed for wealth. It was that I might add to my beauty and see even more admiration in my beloved’s eyes. Of what use to me are my gorgeous gowns, my jewels, my flower-like face, since Anselm no longer delights to see me.”

And for Anselm the pleasures of feasting and luxurious living soon palled. His wife could not laugh at his jokes, and in the wide world there was nothing for him to admire. Neither sunsets, nor courage, nor self-sacrifice. He could see no beauty in any face, thought or action. Lost to him were the delights of Poetry and all the loveliness of Nature.

“What is there in life,” he cried, “but feasting and laughter? If only Jasmine could join with me in mocking at the absurdities of Man!”

Desperately he strove to restore laughter to his mirthless wife. He engaged a thousand jesters and promised a fortune to 51him who should make her laugh. Everything human beings consider funny was shown to her. Orange peel was plentifully scattered outside the palace windows, and aged men encouraged to walk past, that they might step on the orange peel and fall. Then, by means of huge bellows purposely placed, their hats were blown from off their heads, in the hope that Jasmine would smile to see the poor old fellows vainly chasing their own headgear. But all in vain. Nothing amused Jasmine, neither physical misfortune nor the finest wit. Her mouth remained set. Daily Anselm laughed louder and longer, but into his laughter an ugly bitterness had come. It was now the laughter of mockery, no longer softened by admiration.

During that summer a child was born to Jasmine. For years she had longed for a baby, but now that the funny little creature squirmed in her arms, yawning, and making faces, she thought it merely ugly and turned from it in disgust.

A few months later the coachman’s wife gave birth to a baby, and Jasmine went to visit her. She found her by the fire, nursing a red, hairless, wrinkled daughter that seemed to Jasmine the ugliest morsel in all the world. In speechless horror she stared at it. Opening wide its shapeless mouth, the baby stretched its tiny arms and gave a great yawn. With a joyful laugh, the mother clutched it to her heart. “Oh, you darling, darling!” she cried. “Could anyone not love anything so funny?”

“Is Love then born of Laughter?” cried poor Jasmine, and, full of bitter envy, she rushed from the room.

That same year a terrible war was waged and thousands of soldiers went forth to die. One day, Jasmine gazed out of the window. Brave music was playing, and with colours flying, a gallant host of youths marched past, their weeping mothers and sweethearts waving farewell.

“A disgusting sight, is it not?” said Anselm. “All these 52boys striding off to be killed simply because their foolish kings have quarrelled!”

“Yes,” replied Jasmine, her eyes full of tears. “But beautiful, too.”

“Beautiful?” jeered her husband with a harsh, discordant laugh. “You fool! What beauty can there be in senseless sacrifice?” And, as now often happened, these two fell into loud and bitter wrangling.

Thus daily life became more and more unbearable to Anselm and Jasmine. In spite of all their wealth, boredom pressed heavily upon them. Since she could not laugh, and he could not admire, to both the world seemed full of senseless suffering.

“I can no longer bear this life,” said Jasmine, one day. “Of what use is the beauty to which Anselm is blind? I will seek the Bargain House and buy back the Sense he sold. He will still have his purse with which to buy the luxuries he loves.” And forth she went into the deep, dark forest.

An hour later, Anselm exclaimed:

“I can no longer bear this life. I will buy back Jasmine’s humour that at least we may together mock at this senseless life. She will still have her purse to buy the fineries she loves.” And forth he went into the deep, dark forest.

That evening Jasmine returned without her magic purse, rejoicing that her husband would once more delight in her beauty. She went to say good night to her little son, who lay in his cot, struggling to draw his tiny toes up into his mouth. The window was open. Suddenly he stretched forth his arms towards the shining moon. It looked so good to suck; he longed to grasp it. He struggled and bubbled and clutched, his crinkled face growing crimson with effort. How funny he looked! Suddenly, Jasmine found herself laughing—laughing—laughing until her whole body shook, and happy peals broke through her astonished lips. “Oh, 53you darling, darling little joke,” she cried, joyfully kissing her child.

At that moment in rushed Anselm, and stood transfixed at the dazzling beauty of his wife.

“Jasmine, Jasmine,” he cried, “what has happened. Why are you so dazzlingly beautiful?”

“Because I have no longer a magic purse. I have bought you back your Sense, husband.”

“You too?” cried Anselm; “and I have bought back your laughter.”

“Then we are both poor! Oh, how funny!” cried Jasmine, her laughter growing louder and louder as they fell into one another’s arms.

Thus Anselm and Jasmine parted with their magic purses, and had to work for their daily bread, but they lived happily ever afterwards in a world that was blessedly beautiful and blessedly funny.

“HE CLIMBED A FIR-TREE HIGH”

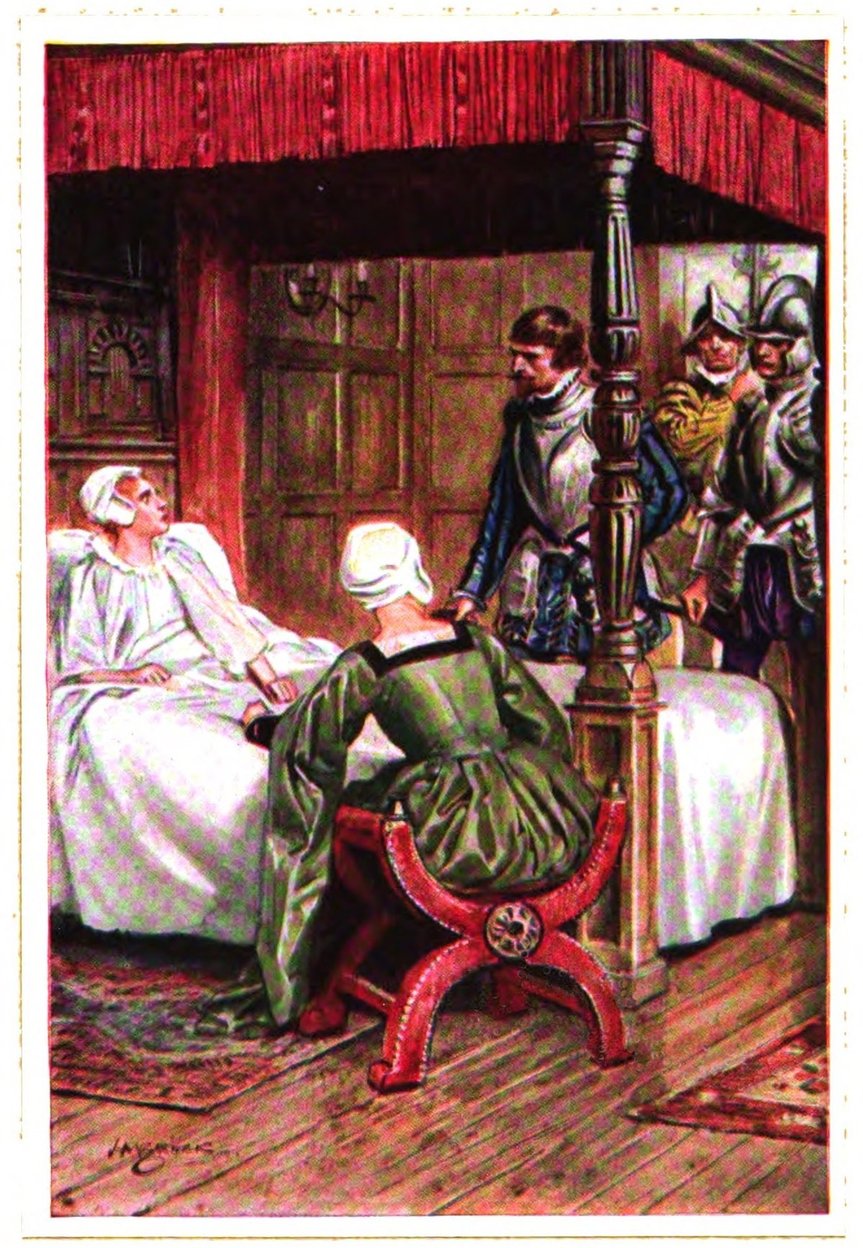

When Queen Mary was persuaded, falsely, that her throne could be made safe only by the death of her sister, then but eighteen years old, the Princess Elizabeth lay sick at Ashridge. One spring morning, as she tossed abed, ’twixt sleeping and waking, in the weariness of fever, she heard in the courtyard beneath her window the tramp of men, the clatter of horses’ hoofs. Her affrighted servants brought her word that a guard of two hundred and fifty horsemen attended the Lords, who came with messages from the Queen, a guard larger than enough to keep watch over so frail a Princess. The house being thus begirt, Lord Thame and his companions, thrust their way into the presence of the Princess. To her demand that if not for courtesy, yet for modesty’s sake, they should put off the delivery of their message till the morrow, they answered that their commission was to bring her to London, alive or dead.

“A sore commission,” said the Princess, but a commission not to be gainsaid. And the Queen’s doctors showed her little pity. She might be removed, said they, not without danger, yet without death.

61So on the morrow, the sad cavalcade set forth. The Princess, that she might be the more darkly shielded from the public gaze, was borne in the Queen’s own litter, which she presently bade to be opened, and thus she made her progress to Whitehall in the full view of the people. It was a tedious and a painful journey. From Ashridge, by St. Alban’s, she came to South Mymms, where again she rested her weary body, and not until four suns had set did she reach the inhospitable Court of Mary, her Queen and her sister.

When she came to Whitehall, she was still a prisoner. It was as though she carried her dungeon with her. Whitehall was less kind even than the white high road, where at least she had found solace in the pity of the humble folk, who wept as she passed, and offered prayers for her safety. Fourteen days she spent in unfriended seclusion, with “no comfort but her innocence, no companion but her book.” Not for her the freedom of the open air, the chatter of tongues, the laughter of friends. Her oft-repeated request to see her sister fell upon the deaf ears of her jailers. A princess of less courage would have quailed before the ill-omened silence which enwrapped her. And how could she hope to regain the Queen’s affection, so long as the cunning servants of the Emperor and the King of France, Renard and Noailles, were there to distil the poison of hate and dread in Queen Mary’s ear?

Knowing well that her foes were the Queen’s friends, her friends the Queen’s foes, she was still of a stout heart. When Gardiner, the Bishop of Winchester, resolute to entrap her, urged her to confess and to submit herself to the Queen’s Majesty, “submission,” said she proudly, “confessed a crime, and pardon belonged to a delinquent.” For her part she had no crime to 62confess, and she asked no pardon. So for her temerity she was told that two hundred Northern Whitecoats should guard her lodging that night, and that in the morn she should be secretly conveyed to the Tower, without her household, there to be kept a close prisoner.

It was a Palm Sunday when she set forth, under a guard, to that place of ill-omen, the Tower of London. Hers was no triumphal progress; neither palm nor willow was carried in her honour. And well might she dread the journey, which she was forced to make. Within the dark walls of the Tower her mother had laid her fair head down upon the block; and what cause had she to hope for a happier destiny? As she left Whitehall, to her a place of durance, she looked up to the window of the Queen’s bedchamber, hoping there to see some mark of favour, some signal of affection. The hope was vain, and in cold despair she came to the Stairs, where the barges awaited her. When she reached the Tower, she was bidden to enter at the Traitor’s Gate, which at first she refused, and then stepping short so that her foot fell into the water, she spake these words to her obdurate jailer:

“Here landeth as true a subject, being prisoner, as ever landed at these stairs, since Julius Cæsar laid the first foundations of the Tower.”

The Constable, a wry-faced ruffian, lurched forth savagely to receive her, and in a harsh voice told her that he would show her her lodging. Then she, being faint, “sat down,” we are told, “upon a fair stone, at which time there fell a great shower of rain: the heavens themselves did seem to weep at such inhuman usage.”

SCENES IN THE LIFE OF A PRINCESS

“They answered that their commission was to bring her to London, alive or dead.”

63Presently she was locked and bolted in the Tower; her own servants were taken from her; to open her casement, that she might enjoy the fresh air of heaven, to walk in the garden—these were pleasures denied her. One sole thing was constantly demanded of her, that she should confess herself a rebel and submit herself to the Queen. Nobly did she refuse, and was left to silence and her own proud thoughts.

She changed her prison, and kept unchanged her high courage. From the Tower she was carried to Woodstock. But what mattered it where the dungeon lay? The locks and bolts were no more easily burst asunder at Woodstock than at the Tower. And then of a sudden her keeper was bidden to bring her to Hampton Court, not as a free Princess, but as a guarded malefactor. At Colnbrook, where on the way she sojourned at the sign of the George, certain gentlemen, devoted to her service, came to do her homage. Instantly, at the Queen’s command, they were sent about their business, and the Princess was bidden to enter Hampton Court, without an escort, and by the back gate, like the humblest menial. Again for many days she was left solitary and in silence, when she was summoned one night into the presence of the Queen, her sister, whose heavy hand she had felt unceasingly, whose face she had not seen for two long years. The Queen, sitting on her chair of State, took up her promise of loyalty sharply and shortly.

“Then you will not confess yourself,” said she, “to be a delinquent, I see, but stand peremptorily upon your truth and innocence; I pray God they may so fall out.”

To which the Princess replied: “If not, I neither require favour nor pardon at your Majesty’s hands.”

“Well,” said the Queen, “then you stand so stiffly upon your faith and loyalty, that you suppose yourself to have been wrongfully punished and imprisoned.”

64“I cannot,” replied the Princess, “nor must not say so to you.”

“Why then belike,” retorted the Queen, “you will report it to others.”

“Not so,” said the Princess. “I have borne and must bear the burden myself.”

The two sisters never met again, but the Princess’s courage in facing her fate was not in vain. Thenceforth she was eased of her imprisonment, and went to Ashridge in free custody, where she remained at her pleasure, until Queen Mary’s death.

In 1558 the Queen died, and the Princess Elizabeth, justified of her patience and her courage, was proclaimed Queen of England. In the loyal enthusiasm of her subjects, who had long since acclaimed her in their hearts, the years of solitude and imprisonment were forgotten. To the Tower, which she had left a captive, she returned a monarch, and passed in triumph through her City of London to Westminster. Everywhere she was welcomed by pageants and loyal discourse, until she came to the famous Abbey where she was crowned, to the contentment of her loyal lieges and to the honour and glory of her realm.

In writing a story a safe plan must be to imitate your favourite author. Until he was nine, when he abandoned the calling, Neil was my favourite author, and I therefore decide to follow his method of dividing the story into short chapters so as to make it look longer.

When he was nine I took him to his preparatory, he prancing in the glories of the unknown until the hour came for me to go, “the hour between the dog and the wolf,” and then he was afraid. I said that in the holidays all would be just as it had been before, but the newly-wise one shook his head; and on my return home, when I wandered out unmanned to look at his tool-shed, I found these smashing words in his writing pinned to the door:

I went white as I saw that Neil already understood life better than I did.

Soon again he was on the wing. Here is interesting autobiographical matter I culled years later from the fly-leaf of his Cæsar: “Aetat 12, height 4 ft. 11, biceps 8¼, kicks the beam at 6-2.”

The reference is to a great occasion when Neil stripped at his preparatory (clandestinely) for a Belt with the word “Bruiser” on it. I am reluctant to boast about him (this is untrue), yet 66must mention that he won the belt, with which (such are the ups and downs of life) he was that same evening gently belted by his preceptor.

It is but fair to Neil to add that he cut a glittering figure in those circles: captain of the footer, and twenty-six against Juddy’s.

“And even then,” his telegram to me said, “I was only bowled off my pads.”

A rural cricket match in buttercup time with boys at play, seen and heard through the trees; it is surely the loveliest scene in England and the most disarming sound. From the ranks of the unseen dead, for ever passing along our country lanes on their eternal journey, the Englishman falls out for a moment to look over the gate of the cricket field and smile. Let Neil’s 26 against Juddy’s, the first and perhaps the only time he is to meet the stars on equal terms, be our last sight of him as a child. He is walking back bat in hand to the pavilion, an old railway carriage. An unearthly glory has swept over the cricket ground. He tries to look unaware of it; you know the expression and the bursting heart. Our smiling Englishman who cannot open the gate waits to make sure that this boy raises his cap in the one right way (without quite touching it, you remember), and then rejoins his comrades. Neil gathers up the glory and tacks it over his bed. “The End,” as he used to say in his letters.

I never know him quite so well again. He seems henceforth to be running to me on a road that is moving still more rapidly in the opposite direction.

The scene has changed. Stilled is the crow of Neil, for he is now but one of the lowliest at a great public school, where he reverberates but little. The scug Neil fearfully running errands 67for his fag-master is another melancholy reminder of the brevity of human greatness.

Lately a Colossus he was now infinitely less than nothing. What shook him was not the bump as he fell, but the general indifference to his having fallen. He lay there like a bird in the grass winded by a blunt-headed arrow, and was cold to his own touch. The Bruiser Belt and his score against Juddy’s had accompanied him to school on their own legs, one might say, so confident were they of a welcome from his mantelshelf, but after an hour he hid them beneath the carpet. Hidden by him all over that once alluring room, as in disgrace, were many other sweet trifles that went to the making of the flame that had been Neil; his laugh was secreted, say in the drawer of his desk; his pranks were stuffed into his hat-box, his fell ambitions were folded away between two pairs of trousers, and now and then a tear would mix with the soapy water as he washed his cheerless face.

In that dreadful month or more I am dug up by his needs and come again into prominence, gloating because he calls for me, sometimes unable to do more than stand afar off on the playing field, so that he may at least see me nigh though we cannot touch. The thrill of being the one needed, which I had never thought to know again. I have leant over a bridge, and enviously watching the gaiety of two attractive boys, now broken to the ways of school, have wished he was one of them, till I heard their language and wondered whether this was part of the necessary cost.

Leaden-footed Neil in the groves that were to become so joyous to him. He had to refashion himself on a harsher model, and he set his teeth and won, blaming me a little for not having broken to him the ugly world we can make it. One by one his hidden parts peeped out from their holes and ran to him, once more to make his wings; stronger wings than of yore, though some drops of dew had to be shaken off.

68By that time my visits were being suffered rather than acclaimed. It was done with an exquisite politeness certainly, but before I was out of sight he had dived into some hilarious rumpus. Gladly for his sake I knew my place.

His first distinct success was as a gargler.

“WE GENERALLY GARGLE A SONG”

“You remember how I used to hate gargling at home,” says an early letter, “and you forced me to do it. Jolly good thing 69you did force me.” His first “jolly” at that school. At once I began to count them.

“Everyone has to gargle just now,” he continues, “and we all do it at the same time, and it must sound awfully rum to people passing along the street. We generally gargle a song, and there was a competition in ‘Home, sweet Home’ among the scugs at m’ tutor’s, and the judge said I gargled it longest.”

Soon afterwards he had the exultation of being recognised as an entity by one of the masters.

“I was walking with Dolman mi.,” his letter says, “and we met a new beak called Tiverley and he pretended to fence with me and said ‘Whose incomparable little noodle are you?’” This, apparently, was all that happened, but Neil adds with obvious elation, “It was awfully decent of him.” (Hail to thee, Tiverley, may “a house” anon be thy portion for heartening a new boy in the dwindling belief that he exists.)

Dolman mi. evidently had no run on this occasion, but he is older and more famous than Neil (which makes the thing the more flattering). It is a school whither many royal scions are sent, and when camera men go down to photograph the new one, Dolman mi. usually takes his place. He has already been presented to newspaper readers as the heir to three thrones. Of course it is the older boys who select, scrape and colour him (if necessary) for this purpose, but they must see something in him that the smaller boys don’t see.

Neil’s next step was almost a bound forward; he got a tanning from the head of the house. This also he took in the proper spirit, boasting indeed of the vigour with which Beverley had laid on. (Thee, also, Beverley, I salute, as the Immensity who raised Neil from the ranks of the lowly, the untanned.)

Quite the amiable, sensible little schoolboy, readers may be saying, but that Neil was amiable or sensible I indignantly deny. 70He was merely waiting; that shapely but enquiring nose of his was only considering how best to strike once more for leadership. So when the time came he was ready; and he has been striking ever since, indeed, there is nothing that I think he so much resembles as a clock that has got out of hand.

All the other small boys in his house had the same opportunity, but they missed it. It was provided by some learned man (name already tossed to oblivion) who delivered unto them a lecture entitled Help One Another. The others behaved in the usual way, cheered the lecturer heartily when he took a drink of water, said “Silly old owl!” as they went out and at once forgot his Message. Not so Neil. With the clearness of vision that always comes to him when anything to his own advantage is toward, he saw that the time and the place and the loved one (himself) had arrived together. Portents in the sky revealed to him that his métier at school was to Help Others. There would be something sublime about it had he not also seen with the same vividness that he must make a pecuniary charge of threepence. He decided astutely to begin with W. W. Daly.

As we write these words an extraordinary change comes over our narrative. In the dead silence that follows this announcement to our readers you may hear, if you listen intently, a scurrying of feet, which is nothing less than Neil being chased out of the story. The situation is one probably unparalleled in fiction.

Elated by your curiosity we now leave Neil for a moment (say, searching with his foot for a clean shirt among a pile of clothing on the floor), mount to the next landing and enter the second room on the left, the tenant of which immediately dives beneath his table under the impression that we are a fag-master shouting 71“Boy.” We drag him out and present him to you as W. W. Daly. He is five feet one, biceps 7¾, and would probably kick the beam at about 6½ stone. He is not yet celebrated for anything except for being able to stick pins into his arm up to the head; otherwise a creature of small account who, but for Neil’s patronage, would never have risen to the distinction of being written about, except perhaps by his mother.

W. W.’s first contact with school was made dark by a strange infirmity, an incapacity to remember the Latin equivalent for the word “bell.” Many Latin words were as familiar to him as his socks (perhaps even more so, for he often wears the socks of others), and those words he would give you on demand with the brightness of a boy eager to oblige; but daily did his tutor insist (like one who will have nothing for breakfast but eggs and bacon) on having “bell” alone. Daily was W. W. floored.

It is now that Neil appears with his sunny offer of Help. He took up the case so warmly that he entirely neglected his own studies, which is one of his failings. True he charged threepence (which we shall henceforth write as 3d., as it is so sure to come often into these chronicles), but this detracts little from his grandeur, for the mere apparatus required cost him what he calls a bob.

His first procedure was to affix to the bell-pull a card bearing in bold letters the device “Tintinnabulum.” This seems simple but was complicated by there being no bell in W. W.’s room. Neil bought a bell (W. W. being “stony”), and round the walls he constructed a gigantic contrivance of wire and empty ginger-beer bottles, culminating at one end in the bell and at the other end in W. W.’s foot as he lay abed. The calculation, a well-founded one, was that if the sleeper tossed restlessly the bell would ring and he would awake. He was then, as instructed by Neil, first, to lie still but as alert as if visited by a ghost, and to think hard for the word. If, however, it still eluded him he was to turn 72upon it the electric torch, kept beneath his pillow for this purpose and borrowed at 1d. per week from Dolman mi., spot the tricky “Tintinnabulum” in its lair and say the word over to himself a number of times before returning to his slumbers, something attempted, something done to earn a night’s repose.

All this did W. W. conscientiously do, and if there was delay in bringing Tintinnabulum to heel the fault was not that of Neil, but of inferior youths who used to substitute cards inscribed “Honorificabilitudinitatibus,” “Porringer,” “Xylobalsamum,” “Beelzebobulus,” and other likely words.

Eventually he achieved; a hard-won ribbon for his benefactor whom we are about to call Neil for the last time.

There was a feeling among those who had betted on the result that it should be celebrated in no uncertain manner, and a dinner with speeches not being feasible (though undoubtedly he would have liked it), he was re-christened Tintinnabulum, and the name stuck.

So Tintinnabulum let it be henceforth in these wandering pages. Neil the disinherited may be pictured pattering back to me on his naked soles and knocking me up in the night.

“Neil,” I cry (in dressing gown and a candle), “what has happened? Have you run away from school?”

“Rather not,” says the plaintive ghost, shivering closer to the fire, “I was kicked out.”

“By your tutor?” I ask blanching.

“No, by Tintinnabulum. He is becoming such a swell among the juniors that he despises me and the old times. And now he has kicked me out.”

“Drink this hot milk, Neil, and tell me more. What are those articles you are hugging beneath your pyjamas?”

“They are the Bruiser Belt and the score against Juddy’s. He threw them out after me.”

73“Don’t take it so much to heart, Neil. I’ll find an honoured place for them here, and you and I will have many a cosy talk by the fire about Tintinnabulum.”

“I don’t want to talk about him,” he says, his hands so cold that he spills the milk, “I would rather talk about the days before there was him.”

Well, perhaps that was what I meant.

Cruel Tintinnabulum.

Soon after the events described in our last chapter I knew from Tintinnabulum’s letters that he was again Helping. They were nevertheless communications so guarded as to be wrapped in mystery.

His letters from school tend at all times to be more full of instruction for my guidance than of information about where he stands in his form. I notice that he worries less than did an older generation about how I am to dress when I visit him, but he is as pressing as ever that the postal order should be despatched at once, and firmly refuses to write at all unless I enclose stamped envelopes. On important occasions he even writes my letters for me, requesting me to copy them carefully and not to put in any words of my own, as when for some reason they have to be shown to his tutor. He then writes, “Begin ‘Dear T.’ (not ‘Dearest T.’), and end ‘Yours affec.’ (not ‘Yours affectionately’).”

The mysterious letters that preceded the holidays were concerned with W. W. Daly, whom I was bidden (almost ordered) to invite to our home for that lengthy period, “as his mother is to be away at that time on frightfully important business in which I have a hand.”

74I was instructed to write “Dear Mrs. Daly (not “dearest”), I understand that you are to be away on important business during the holidays, and so I have the pleasure to ask you to allow your son to spend the holidays with me and my boy who is a general favourite and very diligent. Come, come, I will take no refusal, and I am, Yours affec.”

I did as I was told, but as I now heard of the lady for the first time I thought it wisest not to sign my letter to her “Yours affec.” Thus did I fall a victim to Tintinnabulum’s wiles.

What could this frightfully important business of Mrs. Daly’s be in which he “had a hand”?

“ON IMPORTANT OCCASIONS HE EVEN WRITES MY LETTERS FOR ME.”

75You may say (when you hear of his dark design) that I should at once have insisted on an explanation, but explanations are barred in the sport that he and I play, which is the greatest of all parlour games, the Game of Trying to Know Each Other without asking questions. It is strictly a game for two, who, I suppose, should in perfect conditions be husband and wife; it is played silently and it never lasts less than a life-time. In panegyrics on love (a word never mentioned between us two players), the game is usually held to have ended in a draw when they understand each other so well that before the one speaks or acts the other knows what he or she is going to say or do. This, however, is a position never truly reached in the game, and if it were reached, such a state of coma for the players could only be relieved by a cane in the hand of the stronger, or by the other bolting, to show him that there was one thing about her which he had still to learn.

No, no, these doited lovers when they think the haven is in sight have set sail only. Tintinnabulum and I have made a hundred moves, but we are well aware that we don’t know each other yet; at least, I don’t know Tintinnabulum, I won’t swear that he does not think that he at last knows me. So when he brought W. W. home with him for the holidays it was for me to find out without inquiry how he had been helping Mrs. Daly (and for what sum). He knew that I was cogitating, I could see his impertinent face regarding me demurely, as if we were at a chess board and his last move had puzzled me, which indeed was the situation.