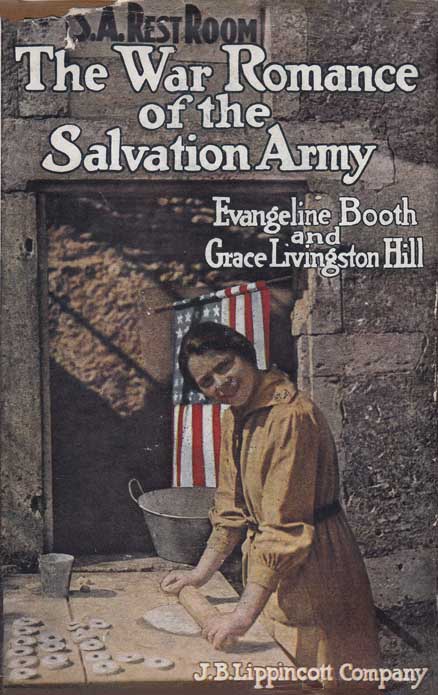

Title: The War Romance of the Salvation Army

Author: Evangeline Booth

Grace Livingston Hill

Release date: April 1, 2005 [eBook #7811]

Most recently updated: March 22, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Curtis A. Weyant and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team

by

and

In presenting the narrative of some of the doings of the Salvation Army during the world’s great conflict for liberty, I am but answering the insistent call of a most generous and appreciative public.

When moved to activity by the apparent need, there was never a thought that our humble services would awaken the widespread admiration that has developed. In fact, we did not expect anything further than appreciative recognition from those immediately benefited, and the knowledge that our people have proved so useful is an abundant compensation for all toil and sacrifice, for service is our watchword, and there is no reward equal to that of doing the most good to the most people in the most need. When our National Armies were being gathered for overseas work, the likelihood of a great need was self-evident, and the most logical and most natural thing for the Salvation Army to do was to hold itself in readiness for action. That we were straitened in our circumstances is well understood, more so by us than by anybody else. The story as told in these pages is necessarily incomplete, for the obvious reason that the work is yet in progress. We entered France ahead of our Expeditionary Forces, and it is my purpose to continue my people’s ministries until the last of our troops return. At the present moment the number of our workers overseas equals that of any day yet experienced.

Because of the pressure that this service brings, together with the unmentioned executive cares incident to the vast work of the Salvation Army in these United States, I felt compelled to requisition some competent person to aid me in the literary work associated with the production of a concrete story. In this I was most fortunate, for a writer of established worth and national fame in the person of Mrs. Grace Livingston Hill came to my assistance; and having for many days had the privilege of working with her in the sifting process, gathering from the mass of matter that had accumulated and which was being daily added to, with every confidence I am able to commend her patience and toil. How well she has done her work the book will bear its own testimony.

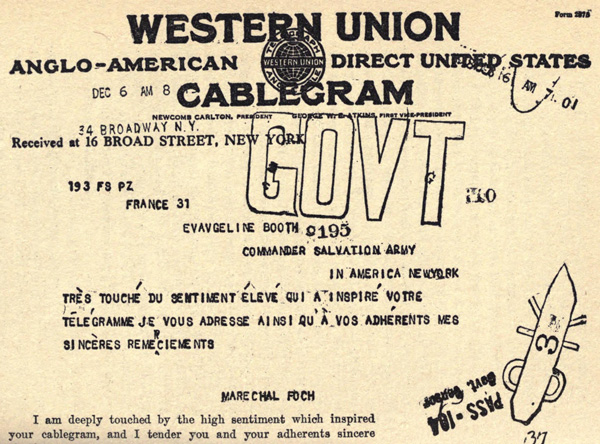

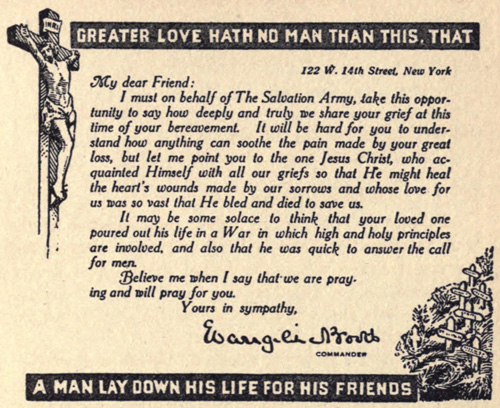

This foreword would be incomplete were I to fail in acknowledging in a very definite way the lavish expressions of gratitude that have abounded on the part of “The Boys” themselves. This is our reward, and is a very great encouragement to us to continue a growing and more permanent effort for their welfare, which is comprehended in our plans for the future. The official support given has been of the highest and most generous character. Marshal Foch himself most kindly cabled me, and General Pershing has upon several occasions inspired us with commendatory words of the greatest worth.

Our beloved President has been pleased to reflect the people’s pleasure and his own personal gratification upon what the Salvation Army has accomplished with the troops, which good-will we shall ever regard as one of our greatest honors.

The lavish eulogy and sincere affection bestowed by the nation upon the organization I can only account for by the simple fact that our ministering members have been in spirit and reality with the men.

True to our first light, first teaching, and first practices, we have always put ourselves close beside the man irrespective of whether his condition is fair or foul; whether his surroundings are peaceful or perilous; whether his prospects are promising or threatening. As a people we have felt that to be of true service to others we must be close enough to them to lift part of their load and thus carry out that grand injunction of the Apostle Paul, “Bear ye one another’s burdens and so fulfill the law of Christ.”

The Salvation Army upon the battlefields of France has but worked along the same lines as in the great cities of the nations. We are, with our every gift to serve, close up to those in need; and so, as Lieut.-Colonel Roosevelt put it, “Whatever the lot of the men, the Salvation Army is found with them.”

We never permit any superiority of position, or breeding, or even grace to make a gap between us and any who may be less fortunate. To help another, you must be near enough to catch the heart-beat. And so a large measure of our success in the war is accounted for by the fact that we have been with them. With a hundred thousand Salvationists on all fronts, and tens and tens of thousands of Salvationists at their ministering posts in the homelands as well as overseas, from the time that each of the Allied countries entered the war the Salvation Army has been with the fighting- men.

With them in the thatched cottage on the hillside, and in the humble dwelling in the great towns of the homelands, when they faced the great ordeal of wishing good-bye to mothers and fathers and wives and children.

With them in the blood-soaked furrows of old fields; with them in the desolation of No Man’s Land; and with them amid the indescribable miseries and gory horrors of the battlefield. With them with the sweetest ministry, trained in the art of service, white-souled, brave, tender-hearted men and women could render.

[Evangeline Booth]

National Headquarters Salvation Army, New York City.

April, 1919.

The war is over. The world’s greatest tragedy is arrested. The awful pull at men’s heart-strings relaxed. The inhuman monster that leapt out of the darkness and laid blood-hands upon every home of a peace-blest earth has been overthrown. Autocracy and diabolical tyranny lie defeated and crushed behind the long rows of white crosses that stand like sign-posts pointing heavenward, all the way from the English Channel to the Adriatic, linking the two by an inseverable chain.

While the nations were in the throes of the conflict, I was constrained to speak and write of the Salvation Army’s activities in the frightful struggle. Now that all is over and I reflect upon the price the nations have paid I realize much hesitancy in so doing.

When I think of England-where almost every man you meet is but a piece of a man! France—one great graveyard! Its towns and cities a wilderness of waste! The allied countries—Italy, and deathless little Belgium, and Serbia—well-nigh exterminated in the desperate, gory struggle! When I think upon it—the price America has paid! The price her heroic sons have paid! They that come down the gangways of the returning boats on crutches! They that are carried down on stretchers! They that sail into New York Harbor, young and fair, but never again to see the Statue of Liberty! The price that dear mothers and fathers have paid! The price that the tens of thousands of little children have paid! The price they that sleep in the lands they made free have paid! When I think upon all this, it is with no little reluctance that I now write of the small part taken by the Salvation Army in the world’s titanic sacrifice for liberty, but which part we shall ever regard as our life’s crowning honor.

Expressions of surprise from officers of all ranks as well as the private soldier have vied with those of gratitude concerning the efficiency of this service, but no thought of having accomplished any achievement higher than their simplest duty is entertained by the Salvationists themselves; for uniformly they feel that they have but striven to measure up to the high standards of service maintained by the Salvation Army, which standards ask of its officers all over the world that no effort shall be left unprosecuted, no sacrifice unrendered, which will help to meet the need at their door.

And it is such high standards of devoted service to our fellow, linked with the practical nature of the movement’s operations, the deeply religious character of its members, its intelligent system of government, uniting, and thus augmenting, all its activities; with the immense advantage of the military training provided by the organization, that give to its officers a potency and adaptability that have for the greater period of our brief lifetime made us an influential factor in seasons of civic and national disaster.

When that beautiful city of the Golden Gate, San Francisco, was laid low by earthquake and fire, the Salvationists were the first upon the ground with blankets, and clothes, and food, gathering frightened little children, looking after old age, and rescuing many from the burning and falling buildings.

At the time of the wild rush to the Klondike, the Salvation Army was, with its sweet, pure women—the only women amidst tens of thousands of men— upon the mountain-side of the Chilcoot Pass saving the lives of the gold- seekers, and telling those shattered by disappointment of treasure that “doth not perish.”

At the time of the Jamestown, the Galveston, and the Dayton floods the Salvation Army officer, with his boat laden with sandwiches and warm wraps, was the first upon the rising waters, ministering to marooned and starving families gathered upon the housetops.

In the direful disaster that swept over the beautiful city of Halifax, the Mayor of that city stated: “I do not know what I should have done the first two or three days following the explosion, when everyone was panic- stricken without the ready, intelligent, and unbroken day-and-night efforts of the Salvation Army.”

On numerous other similar occasions we have relieved distress and sorrow by our almost instantaneous service. Hence when our honored President decided that our National Emblem, heralder of the inalienable rights of man, should cross the seas and wave for the freedom of the peoples of the earth, automatically the Salvation Army moved with it, and our officers passed to the varying posts of helpfulness which the emergency demanded.

Now on all sides I am confronted with the question: What is the secret of the Salvation Army’s success in the war?

Permit me to suggests three reasons which, in my judgment, account for it:

First, when the war-bolt fell, when the clarion call sounded, it found the Salvation Army ready!

Ready not only with our material machinery, but with that precious piece of human mechanism which is indispensable to all great and high achievement—the right calibre of man, and the right calibre of woman. Men and women equipped by a careful training for the work they would have to do.

We were not many in number, I admit. In France our numbers have been regrettably few. But this is because I have felt it was better to fall short in quantity than to run the risk in falling short in quality. Quality is its own multiplication table. Quality without quantity will spread, whereas quantity without quality will shrink. Therefore, I would not send any officers to France except such as had been fully equipped in our training schools.

Few have even a remote idea of the extensive training given to all Salvation Army officers by our military system of education, covering all the tactics of that particular warfare to which they have consecrated their lives—the service of humanity.

We have in the Salvation Army thirty-nine Training Schools in which our own men and women, both for our missionary and home fields, receive an intelligent tuition and practical training in the minutest details of their service. They are trained in the finest and most intricate of all the arts, the art of dealing ably with human life.

It is a wonderful art which transfigures a sheet of cold grey canvas into a throbbing vitality, and on its inanimate spread visualizes a living picture from which one feels they can never turn their eyes away.

It is a wonderful art which takes a rugged, knotted block of marble, standing upon a coarse wooden bench, and cuts out of its uncomely crudeness—as I saw it done—the face of my father, with its every feature illumined with prophetic light, so true to life that I felt that to my touch it surely must respond.

But even such arts as these crumble; they are as dust under our feet compared with that much greater art, the art of dealing ably with human life in all its varying conditions and phases.

It is in this art that we seek by a most careful culture and training to perfect our officers.

They are trained in those expert measures which enable them to handle satisfactorily those that cannot handle themselves, those that have lost their grip on things, and that if unaided go down under the high, rough tides. Trained to meet emergencies of every character—to leap into the breach, to span the gulf, and to do it without waiting to be told how.

Trained to press at every cost for the desired and decided-upon end.

Trained to obey orders willingly, and gladly, and wholly—not in part.

Trained to give no quarter to the enemy, no matter what the character, nor in what form he may present himself, and to never consider what personal advantage may be derived.

Trained in the art of the winsome, attractive coquetries of the round, brown doughnut and all its kindred.

Trained, if needs be, to seal their services with their life’s blood.

One of our women officers, on being told by the colonel of the regiment she would be killed if she persisted in serving her doughnuts and cocoa to the men while under heavy fire, and that she must get back to safety, replied: “Colonel, we can die with the men, but we cannot leave them.”

When, therefore, I gathered the little companies together for their last charge before they sailed for France, I would tell them that while I was unable to arm them with many of the advantages of the more wealthy denominations; that while I could give them only a very few assistants owing to the great demand upon our forces; and that while I could promise them nothing beyond their bare expenses, yet I knew that without fear I could rely upon them for an unsurpassed devotion to the God-inspired standards of the emblem of this, the world’s greatest Republic, the Stars and Stripes, now in the van for the freedom of the peoples of the earth. That I could rely upon them for unsurpassed devotion to the brave men who laid their lives upon the altar of their country’s protection, and that I could rely upon them for an unsurpassed devotion to that other banner, the Banner of Calvary, the significance of which has not changed in nineteen centuries, and by the standards of which, alone, all the world’s wrongs can be redressed, and by the standards of which alone men can be liberated from all their bondage. And they have not failed.

A further reason for the success of the Salvation Army in the war is, it found us accustomed to hardship.

We are a people who have thrived on adversity. Opposition, persecution, privation, abuse, hunger, cold and want were with us at the starting-post, and have journeyed with us all along the course.

We went to the battlefields no strangers to suffering. The biting cold winds that swept the fields of Flanders were not the first to lash our faces. The sunless cellars, with their mouldy walls and water-seeped floors, where our women sought refuge from shell-fire through the hours of the night, contributed no new or untried experience. In such cellars as these, in their home cities, under the flicker of a tallow candle, they have ministered to the sick and comforted the dying.

Wet feet, lack of deep, being often without food, finding things different from what we had planned, hoped and expected, were frequent experiences with us. All such things we Salvationists encounter in our daily toils for others amid the indescribable miseries and inestimable sorrows, the sins and the tragedies of the underworlds of our great cities—the underneath of those great cities which upon the surface thunder with enterprise and glitter with brilliance.

We are not easily affrighted by frowns of fortune. We do not change our course because of contrary currents, nor put into harbor because of head- winds. Almost all our progress has been made in the teeth of the storm. We have always had to “tack,” but as it is “the set of the sails, and not the gales” that decides the ports we reach, the competency of our seamanship is determined by the fact that we “get there.”

Our service in France was not, therefore, an experiment, but an organized, tested, and proved system. We were enacting no new rôle. We were all through the Boer War. Our officers were with the besieged troops in Mafeking and Ladysmith. They were with Lord Kitchener in his victorious march through Africa. It was this grand soldier who afterwards wrote to my father, General William Booth, the Founder of our movement, saying: “Your men have given us an example both of how to live as good soldiers and how to die as heroes.” And so it was quite natural that our men and women, with that fearlessness which characterizes our members, should take up positions under fire in France.

In fact, our officers would have considered themselves unfaithful to Salvation Army traditions and history, and untrue to those who had gone before, if they had deserted any post, or shirked any duty, because cloaked with the shadows of death.

This explains why their dear forms loomed up in the fog and the rain, in the hours of the night, on the roads, under shell fire, serving coffee and doughnuts.

This is how it was they were with them on the long dreary marches, with a smile and a song and a word of cheer.

This is how it is the Salvation Army has no “closing hours.” “Taps” sound for us when the need is relieved.

Three of our women officers in the Toul Sector had slept for three weeks in a hay-stack, in an open field, to be near the men of an ammunition train taking supplies to the front under cover of darkness. The boys had watched their continued, devoted service for them—the many nights without sleep—and noticing the shabby uniform of the little officer in charge, collected among themselves 1600 francs, and offered it to her for a new one, and some other comforts, the spokesman saying: “This is just to show you how grateful we are to you.” The officer was deeply touched, but told them she could not think of accepting it for herself. “I am quite accustomed to hard toils,” she said. “I have only done what all my comrades are doing—my duty,” and offered to compromise by putting the money into a general fund for the benefit of all—to buy more doughnuts and more coffee for the boys.

Salvation Army teaching and practice is: Choose your purpose, then set your face as flint toward that purpose, permitting no enemy that can oppose, and no sacrifice that can be asked, to turn you from it.

Again, a reason for our success in the war is, our practical religion.

That is, our religion is practicable. Or, I would rather say, our Christianity is practicable. Few realize this as the secret of our success, and some who do realize it will not admit it, but this is what it really is.

We do worship; both in spirit and form, in public and in private. We rely upon prayer as the only line of communication between the creature and his Creator, the only wing upon which the soul’s requirements and hungerings can be wafted to the Fount of all spiritual supply. Through our street, as well as our indoor meetings, perhaps oftener than any other people, we come to the masses with the divine benediction of prayer; and it would be difficult to find the Salvationist’s home that does not regard the family altar as its most precious and priceless treasure.

We do preach. We preach God the Creator of earth and heaven, unerring in His wisdom, infinite in His love and omnipotent in His power. We preach Jesus Christ, God’s only begotten Son, dying on Calvary for a world’s transgressions, able to save to the uttermost “all those who come unto God by Him.” We preach God the Holy Ghost, sanctifier and comforter of the souls of men, making white the life, and kindling lights in every dark landing-place. We preach the Bible, authentic in its statements, immaculate in its teaching, and glorious in its promises. We preach grace, limitless grace, grace enough for all men, and grace enough for each. We preach Hell, the irrevocable doom of the soul that rejects the Saviour. We preach Heaven, the home of the righteous, the reward of the good, the crowning of them that endure to the end.

Even as we preach, so we practice Christianity. We reduce theory to action. We apply faith to deeds. We confess and present Jesus Christ in things that can be done. It is this that has carried our flag into sixty- three countries and colonies, and despite the bitterest opposition has given us the financial support of twenty-one national governments. It is this that has brought us up from a little handful of humble workers to an organization with 21,000 officers and workers, preaching the gospel in thirty-nine tongues. It is this that has multiplied the one bandsman and a despised big drum to an army of 27,000 musicians, and it is this-our practice of religion-that has placed Christ in deeds.

Arthur E. Copping gives as the reason for the movement’s success-“the simple, thorough-going, uncompromising, seven-days-a-week character of its Christianity.” It is this every-day-use religion which has made us of infinite service in the places of toil, breakage, and suffering; this every-day-use religion which has made us the only resource for thousands in misery and vice; this every-day-use religion which has insured our success to an extent that has induced civic authorities, Judges, Mayors, Governors, and even National Governments-such as India with its Criminal Tribes-to turn to us with the problems of the poor and the wicked.

While the Salvationist is not of the generally understood ascetic or monastic type, yet his spirit and deeds are of the very essence of saintliness.

As man has arrested the lazy cloud sleeping on the brow of the hill, and has brought it down to enlighten our darkness, to carry our mail-bags, to haul our luggage, and to flash our messages, so, I would say with all reverence, that the Salvation Army in a very particular way has again brought down Jesus Christ from the high, high thrones, golden pathways, and wing-spread angels of Glory, to the common mud walks of earth, and has presented Him again in the flesh to a storm-torn world, touching and healing the wounds, the bruises, and the bleeding sores of humanity.

That was a wonderful sermon Christ preached on the Mount, but was it more wonderful than the ministry of the wounded man fallen by the roadside, or the drying of the tears from the pale, worn face of the widow of Nain? Or more wonderful than when He said, Let them come—let them come—mothers and the little children—and blessed them?

It has only been this same Christ, this Christ in deeds, when our women have washed the blood from the faces of the wounded, and taken the caked mud from their feet; when under fire, through the hours of the night, they have made the doughnuts; when instead of sleeping they have written the letters home to soldiers’ loved ones, when they have lifted the heavy pails of water and struggled with them over the shell-wrecked roads that the dying soldiers might drink; when they have sewn the torn uniforms; when they have strewn with the first spring flowers the graves of those who died for liberty. Only Christ in deeds when our men went unarmed into the horrors of the Argonne Forest to gather the dying boys in their arms and to comfort them with love, human and divine.

That valiant champion of justice and truth; that faithful, able and brilliant defender of American standards, the late Honorable Theodore Roosevelt, told me personally a few days before he went into the hospital that his son wrote him of how our officer, fifty-three years of age, despite his orders, went unarmed over the top, in the whirl-wind of the charge, amidst the shriek of shell and tear of shrapnel, and picked up the American boy left for dead in No Man’s Land, carrying him on hie back over the shell-torn fields to safety.

It is this Christ in deeds that has made the doughnut to take the place of the “cup of cold water” given in His name. It is this Christ in deeds that has brought from our humble ranks the modern Florence Nightingales and taken to the gory horrors of the battlefields the white, uplifting influences of pure womanhood. It is this Christ in deeds that made Sir Arthur Stanley say, when thanking our General for $10,000 donated for more ambulances: “I thank you for the money, but much more for the men; they are quite the best in our service.”

It is this Christ who has given to our humblest service a sheen-something of a glory-which the troops have caught, and which will make these simple deeds to hold tenaciously to history, and to outlive the effacing fingers of time-even to defy the very dissolution of death.

As Premier Clemenceau said: “We must love. We must believe. This is the secret of life. If we fail to learn this lesson, we exist without living: we die in ignorance of the reality of life.”

A senator, after several months spent in France, stated: “It is my opinion that the secret of the success of this organization is their complete abandonment to their cause, the service of the man.”

Of the many beautiful tributes paid to us by a most gracious public, and by the noblest-hearted and most kindly and gallant army that ever stood up in uniform, perhaps the most correct is this: Complete abandonment to the service of the man.

This, in large measure, is the cause of our success all over the world.

When you come to think of it, the Salvation Army is a remarkable arrangement. It is remarkable in its construction. It is a great empire. An empire geographically unlike any other. It is an empire without a frontier. It is an empire made up of geographical fragments, parted from each other by vast stretches of railroad and immense sweeps of sea. It is an empire composed of a tangle of races, tongues, and colors, of types of civilization and enlightened barbarism such as never before in all human history gathered together under one flag.

It is an army, with its titles rambling into all languages, a soldiery spreading over all lands, a banner upon which the sun never goes down-with its head in the heart of a cluster of islands set in the grey, wind-blown Northern seas, while its territories are scattered over every sea and under every sky.

The world has wondered what has been the controlling force holding this strange empire together. What is the electro-magnetism governing its furthest atom as though it were at your elbow? What is the magic sceptre that compels this diversity of peoples to act as one man? What is the master passion uniting these multifarious pulsations into one heart-beat?

Has it been a sworn-to signature attached to bond or paper? No; these can all too readily be designated “scraps” and be rent in twain. Has it been self-interest and worldly fame? No, for all selfish gain has had to be sacrificed upon the threshold of the contract. Has it been the bond of kinship, or blood, or speech? No, for under this banner the British master has become the servant of the Hindoo, and the American has gone to lay down his life upon the veldts of Africa. Has it been the bond of that almost supernatural force, glorious patriotism? No, not even this, for while we “know no man after the flesh,” we recognize our brother in all the families of the earth, and our General infused into the breasts of his followers the sacred conviction that the Salvationist’s country is the world.

What was it? What is it? Those ties created by a spiritual ideal. Our love for God demonstrated by our sacrifice for man.

My father, in a private audience with the late King Edward, said: “Your Majesty, some men’s passion is gold; some men’s passion is art; some men’s passion is fame; my passion is man!”

This was in our Founder’s breast the white flame which ignited like sparks in the hearts of all his followers.

Man is our life’s passion.

It is for man we have laid our lives upon the altar. It is for man we have entered into a contract with our God which signs away our claim to any and all selfish ends. It is for man we have sworn to our own hurt, and—my God thou knowest-when the hurt came, hard and hot and fast, it was for man we held tenaciously to the bargain.

After the torpedoing of the Aboukir two sailors found themselves clinging to a spar which was not sufficiently buoyant to keep them both afloat. Harry, a Salvationist, grasped the situation and said to his mate: “Tom, for me to die will mean to go home to mother. I don’t think it’s quite the same for you, so you hold to the spar and I will go down; but promise me if you are picked up you will make my God your God and my people your people.” Tom was rescued and told to a weeping audience in a Salvation Army hall the act of self-sacrifice which had saved his life, and testified to keeping his promise to the boy who had died for him.

When the Empress of Ireland went down with a hundred and thirty Salvation Army officers on board, one hundred and nine officers were drowned, and not one body that was picked up had on a life-belt. The few survivors told how the Salvationists, finding there were not enough life- preservers for all, took off their own belts and strapped them upon even strong men, saying, “I can die better than you can;” and from the deck of that sinking boat they flung their battle-cry around the world— Others!

Man! Sometimes I think God has given us special eyesight with which to look upon him, We look through the exterior, look through the shell, look through the coat, and find the man. We look through the ofttimes repulsive wrappings, through the dark, objectionable coating collected upon the downward travel of misspent years, through the artificial veneer of empty seeming-through to the man.

He that was made after God’s image.

He that is greater than firmaments, greater than suns, greater than worlds.

Man, for whom worlds were created, for whom Heavens were canopied, for whom suns were set ablaze. He in whose being there gleams that immortal spark we call the soul. And when this war came, it was natural for us to look to the man-the man under the shabby clothes, enlisting in the great armies of freedom; the man going down the street under the spick and span uniform; the man behind the gun, standing in the jaws of death hurling back world autocracy; the man, the son of liberty, discharging his obligations to them that are bound; the man, each one of them, although so young, who when the fates of the world swung in the balances proved to be the man of the hour; the man, each one of them, fighting not only for today but for tomorrow, and deciding the world’s future; the man who gladly died that freedom might not be dead; the man dear to a hundred million throbbing hearts; the man God loved so much that to save him He gave His only Son to the unparalleled sacrifice of Calvary, with its measureless ocean of torment heaving up against His Heart in one foaming, wrathful, omnipotent surge.

Wherein is price? What constitutes cost, when the question is The Man?

I wish I could give you a picture of Commander Evangeline Booth as I saw her first, who has been the Source, the Inspiration, the Guide of this story.

I went to the first conference about this book in curiosity and some doubt, not knowing whether it was my work; not altogether sure whether I cared to attempt it. She took my hand and spoke to me. I looked in her face and saw the shining glory of her great spirit through those wonderful, beautiful, wise, keen eyes, and all doubts vanished. I studied the sincerity and beauty of her vivid face as we talked together, and heard the thrilling tale she was giving me to tell because she could not take the time from living it to write it, and I trembled lest she would not find me worthy for so great a task. I knew that I was being honored beyond women to have been selected as an instrument through whom the great story of the Salvation Army in the War might go forth to the world. That I wanted to do it more than any work that had ever come to my hand, I was certain at once; and that my whole soul was enmeshed in the wonder of it. It gripped me from the start. I was over-joyed to find that we were in absolute sympathy from the first.

One sentence from that earliest talk we had together stands clear in my memory, and it has perhaps unconsciously shaped the theme which I hope will be found running through all the book:

“Our people,” said she, flinging out her hands in a lovely embracing movement, as if she saw before her at that moment those devoted workers of hers who follow where she leads unquestioningly, and stay not for fire or foe, or weariness, or peril of any sort:

“Our people know that Christ is a living presence, that they can reach out and feel He is near: that is why they can live so splendidly and die so heroically!”

As she spoke a light shone in her face that reminded me of the light that we read was on Moses’ face after he had spent those days in the mountain with God; and somewhere back in my soul something was repeating the words: “And they took knowledge of them that they had been with Jesus.”

That seems to me to be the whole secret of the wonderful lives and wonderful work of the Salvation Army. They have become acquainted with Jesus Christ, whom to know is life eternal; they feel His presence constantly with them and they live their lives “as seeing Him who is invisible.” They are a living miracle for the confounding of all who doubt that there is a God whom mortals may know face to face while they are yet upon the earth.

The one thing that these people seem to feel is really worth while is bringing other people to know their Christ. All other things in life are merely subservient to this, or tributary to it. All their education, culture and refinement, their amazing organization, their rare business ability, are just so many tools that they use for the uplift of others. In fact, the word “others” appears here and there, printed on small white cards and tacked up over a desk, or in a hallway near the elevator, anywhere, everywhere all over the great building of the New York Headquarters, a quiet, unobtrusive, yet startling reminder of a world of real things in the midst of the busy rush of life.

Yet they do not obtrude their religion. Rather it is a secret joy that shines unaware through their eyes, and seems to flood their whole being with happiness so that others can but see. It is there, ready, when the time comes to give comfort, or advice, or to tell the message of the gospel in clear ringing sentences in one of their meetings; but it speaks as well through a smile, or a ripple of song, or a bright funny story, or something good to eat when one is hungry, as it does through actual preaching. It is the living Christ, as if He were on earth again living in them. And when one comes to know them well one knows that He is!

“Go straight for the salvation of souls: never rest satisfied unless this end is achieved!” is part of the commission that the Commander gives to her envoys. It is worth while stopping to think what would be the effect on the world if every one who has named the name of Christ should accept that commission and go forth to fulfill it.

And you who have been accustomed to drop your pennies in the tambourine of the Salvation Army lassies at the street corners, and look upon her as a representative of a lower class who are doing good “in their way,” prepare to realize that you have made a mistake. The Salvation Army is not an organization composed of a lot of ignorant, illiterate, reformed criminals picked out of the slums. There may be among them many of that class who by the army’s efforts have been saved from a life of sin and shame, and lifted up to be useful citizens; but great numbers of them, the leaders and officers, are refined, educated men and women who have put Christ and His Kingdom first in their hearts and lives. Their young people will compare in every way with the best of the young people of any of our religious denominations.

After the privilege of close association with them for some time I have come to feel that the most noticeable and lovely thing about the girls is the way they wear their womanhood, as if it were a flower, or a rare jewel. One of these girls, who, by the way, had been nine months in France, all of it under shell fire, said to me:

“I used to wish I had been born a boy, they are not hampered so much as women are; but after I went to France and saw what a good woman meant to those boys in the trenches I changed my mind, and I’m glad I was born a woman. It means a great deal to be a woman.”

And so there is no coquetry about these girls, no little personal vanity such as girls who are thinking of themselves often have. They take great care to be neat and sweet and serviceable, but as they are not thinking of themselves, but only how they may serve, they are blest with that loveliest of all adorning, a meek and quiet spirit and a joy of living and content that only forgetfulness of self and communion with Jesus Christ can bring.

I feel as if I would like to thank every one of them, men and women and young girls, who have so kindly and generously and wholeheartedly given me of their time and experiences and put at my disposal their correspondence to enrich this story, and have helped me to go over the ground of the great American drives in the war and see what they saw, hear what they heard, and feel as they felt. It has been one of the greatest experiences of my life.

And she, their God-given leader, that wonderful woman whose wise hand guides every detail of this marvellous organization in America, and whose well furnished mind is ever thinking out new ways to serve her Master, Christ; what shall I say of her whom I have come to know and love so well?

Her exceptional ability as a public speaker is of the widest fame, while comparatively few, beyond those of her most trusted Officers, are brought into admiring touch with her brilliant executive powers. All these, however, unite in most unstinted praise and declare that functioning in this sphere, the Commander even excels her platform triumphs. But one must know her well and watch her every day to understand her depth of insight into character, her wideness of vision, her skill of making adverse circumstances serve her ends. Born with an innate genius for leadership, swallowed up in her work, wholly consecrated to God and His service, she looks upon men, as it were, with the eyes of the God she loves, and sees the best in everybody. She sees their faults also, but she sees the good, and is able to take that good and put it to account, while helping them out of their faults. Those whom she has so helped would kiss the hem of her garment as she passes. It is easy to see why she is a leader of men. It is easy to see who has made the Army here in America. It is easy to see who has inspired the brave men and wonderful women who went to France and labored.

She would not have me say these things of her, for she is humble, as such a great leader should be, knowing all her gifts and attainments to be but the glory of her Lord; and this is her book. Only in this chapter can I speak and say what I will, for it is not my book. But here, too, I waive my privilege and bow to my Commander.

[Grace Livingston Hill]

Into the heavy shadows that swathe the feet of the tall buildings in West Fourteenth Street, New York, late in the evening there slipped a dark form. It was so carefully wrapped in a black cloak that it was difficult to tell among the other shadows whether it was man or woman, and immediately it became a part of the darkness that hovered close to the entrances along the way. It slid almost imperceptibly from shadow to shadow until it crouched flatly against the wall by the steps of an open door out of which streamed a wide band of light that flung itself across the pavement.

Down the street came two girls in poke bonnets and hurried in at the open door. The figure drew back and was motionless as they passed, then with a swift furtive glance in either direction a head came cautiously out from the shadow and darted a look after the two lassies, watched till they were out of sight, and a form slid into the doorway, winding about the turning like a serpent, as if the way were well planned, and slipped out of sight in a dark corner under the stairway.

Half an hour or perhaps an hour passed, and one or two hurrying forms came in at the door and sped up the stairs from some errand of mercy; then the night watchman came and fastened the door and went away again, out somewhere through a back room.

The interloper was instantly on the alert, darting out of its hiding place, and slipping noiselessly up the stairs as quietly as the shadow it imitated; pausing to listen with anxious mien, stepping as a cloud might have stepped with no creak of stairway or sound of going at all.

Up, up, up and up again, it darted, till it came to the very top, pausing to look sharply at a gleam of light under a door of some student not yet asleep.

From under the dark cloak slid a hand with something in it. Silently it worked, swiftly, pouring a few drops here, a few drops there, of some colorless, odorless matter, smearing a spot on the stair railing, another across from it on the wall, a little on the floor beyond, a touch on the window seat at the end of the hall, some more on down the stairs.

On rubbered feet the fiend crept down; halting, listening, ever working rapidly, from floor to floor and back to the entrance way again. At last with a cautious glance around, a pause to rub a match skilfully over the woolen cloak, and to light a fuse in a hidden corner, he vanished out upon the street like the passing of a wraith, and was gone in the darkness.

Down in the dark corner the little spark brooded and smouldered. The watchman passed that way but it gave no sign. All was still in the great building, as the smouldering spark crept on and on over its little thread of existence to the climax.

But suddenly, it sprang to life! A flame leaped up like a great tongue licking its lips before the feast it was about to devour; and then it sprang as if it were human, to another spot not far away; and then to another, and on, and on up the stair rail, across to the wall, leaping, roaring, almost shouting as if in fiendish glee. It flew to the top of the house and down again in a leap and the whole building was enveloped in a sheet of flame!

Some one gave the cry of Fire! The night watchman darted to his box and sent in the alarm. Frightened girls in night attire crowded to their doors and gasping fell back for an instant in horror; then bravely obedient to their training dashed forth into the flame. Young men on other floors without a thought for themselves dropped into order automatically and worked like madmen to save everyone. The fire engines throbbed up almost immediately, but the building was doomed from the start and went like tinder. Only the fire drill in which they had constant almost daily practice saved those brave girls and boys from an awful death. Out upon the fire escapes in the bitter winter wind the girls crept down to safety, and one by one the young men followed. The young man who was fire sergeant counted his men and found them all present but one cadet. He darted back to find him, and that moment with a last roar of triumph the flames gave a final leap and the building collapsed, burying in a fiery grave two fine young heroes. Afterward they said the building had been “smeared” or it never could have gone in a breath as it did. The miracle was that no more lives were lost.

So that was how the burning of the Salvation Army Training School occurred.

The significant fact in the affair was that there had been sleeping in that building directly over the place where the fire started several of the lassies who were to sail for France in a day or two with the largest party of war workers that had yet been sent out. Their trunks were packed, and they were all ready to go. The object was all too evident.

There was also proof that the intention had been to destroy as well the great fireproof Salvation Army National Headquarters building adjoining the Training School.

A few days later a detective taking lunch in a small German restaurant on a side street overheard a conversation:

“Well, if we can’t burn them out we’ll blow up the building, and get that damn Commander, anyhow!”

Yet when this was told her the Commander declined the bodyguard offered her by the Civic Authorities, to go with her even to her country home and protect her while the war lasted! She is naturally a soldier.

The Commander had stayed late at the Headquarters one evening to finish some important bit of work, and had given orders that she should not be interrupted. The great building was almost empty save for the night watchman, the elevator man, and one or two others.

She was hard at work when her secretary appeared with an air of reluctance to tell her that the elevator man said there were three ladies waiting downstairs to see her on some very important business. He had told them that she could not be disturbed but they insisted that they must see her, that she would wish it if she knew their business. He had come up to find out what he should answer them.

The Commander said she knew nothing about them and could not be interrupted now. They must be told to come again the next day.

The elevator man returned in a few minutes to say that the ladies insisted, and said they had a great gift for the Salvation Army, but must see the Commander at once and alone or the gift would be lost.

Quickly interested the Commander gave orders that they should be brought up to her office, but just as they were about to enter, the secretary came in again with great excitement, begging that she would not see the visitors, as one of the men from downstairs had ’phoned up to her that he did not like the appearance of the strangers; they seemed to be trying to talk in high strained voices, and they had very large feet. Maybe they were not women at all.

The Commander laughed at the idea, but finally yielded when another of her staff entered and begged her not to see strangers alone so late at night; and the callers were informed that they would have to return in the morning if they wished an interview.

Immediately they became anything but ladylike in their manner, declaring that the Salvation Army did not deserve a gift and should have nothing from them. The elevator man’s suspicions were aroused. The ladies were attired in long automobile cloaks, and close caps with large veils, and he studied them carefully as he carried them down to the street floor once more, following them to the outer door. He was surprised to find that no automobile awaited them outside. As they turned to walk down the street, he was sure he caught a glimpse of a trouser leg from beneath one of the long cloaks, and with a stride he covered the space between the door and his elevator where was a telephone, and called up the police station. In a few moments more the three “ladies” found themselves in custody, and proved to be three men well armed.

But when the Commander was told the truth about them she surprisingly said: “I’m sorry I didn’t see them. I’m sure they would have done me no harm and I might have done them some good.”

But if she is courageous, she is also wise as a serpent, and knows when to keep her own counsel.

During the early days of the war when there were many important matters to be decided and the Commander was needed everywhere, she came straight from a conference in Washington to a large hotel in one of the great western cities where she had an appointment to speak that night. At the revolving door of the hotel stood a portly servitor in house uniform who was most kind and noticeably attentive to her whenever she entered or went out, and was constantly giving her some pointed little attention to draw her notice. Finally, she stopped for a moment to thank him, and he immediately became most flattering, telling her he knew all about the Salvation Army, that he had a brother in its ranks, was deeply interested in their work in France, and most proud of what they were doing. He told her he had lived in Washington and said he supposed she often went there. She replied pleasantly that she had but just come from there, but some keen intuition began to warn this wise-hearted woman and when the next question, though spoken most casually, was: “Where are the Salvation Army workers now in France?” she replied evasively:

“Oh, wherever they are most needed,” and passed on with a friend.

“I believe that man is a spy!” she said to her friend with conviction in her voice.

“Nonsense!” the friend replied; “you are growing nervous. That man has been in this hotel for several years.”

But that very night the man, with five others, was arrested, and proved to be a spy hunting information about the location of the American troops in France.

Now these incidents do not belong in just this spot in the book, but they are placed here of intention that the reader may have a certain viewpoint from which to take the story. For well does the world of evil realize what a strong force of opponents to their dark deeds is found in this great Christian organization. Sometimes one is able the better to judge a man, his character and strength, when one knows who are his enemies.

It was the beginning of the dark days of 1917.

The Commander sat in her quiet office, that office through which, except on occasions like this when she locked the doors for a few minutes’ special work, there marched an unbroken procession of men and affairs, affecting both souls and nations.

Before her on the broad desk lay the notes of a new address which she was preparing to deliver that evening, but her eyes were looking out of the wide window, across the clustering roofs of the great city to the white horizon line, and afar over the great water to the terrible scene of the Strife of Nations.

For a long time her thoughts had been turning that way, for she had many beloved comrades in that fight, both warring and ministering to the fighters, and she had often longed to go herself, had not her work held her here. But now at last the call had come! America had entered the great war, and in a few days her sons would be marching from all over the land and embarking for over the seas to fling their young lives into that inferno; and behind them would stalk, as always in the wake of War, Pain and Sorrow and Sin! Especially Sin. She shuddered as she thought of it all. The many subtle temptations to one who is lonely and in a foreign land.

Her eyes left the far horizon and hovered over the huddling roofs that represented so many hundreds of thousands of homes. So many mothers to give up their sons; so many wives to be bereft; so many men and boys to be sent forth to suffer and be tried; so many hearts already overburdened to be bowed beneath a heavier load! Oh, her people! Her beloved people, whose sorrows and burdens and sins she bore in her heart and carried to the feet of the Master every day! And now this war!

And those young men, hardly more than children, some of them! With her quick insight and deep knowledge of the world, she visualized the way of fire down which they must walk, and her soul was stricken with the thought of it! It was her work and the work of her chosen Army to help and save, but what could she do in such a momentous crisis as this? She had no money for new work. Opportunities had opened up so fast. The Treasury was already overtaxed with the needs on this side of the water. There were enterprises started that could not be given up without losing precious souls who were on the way toward becoming redeemed men and women, fit citizens of this world and the next. There was no surplus, ever! The multifarious efforts to meet the needs of the poorest of the cities’ poor, alone, kept everyone on the strain. There seemed no possibility of doing more. Besides, how could they spare the workers to meet the new demand without taking them from places where they were greatly needed at home? And other perplexities darkened the way. There were those sitting in high places of authority who had strongly advised the Salvation Army to remain at home and go on with their street meetings, telling them that the battlefield was no place for them, they would only be in the way. They were not adapted to a thing like war. But well she knew the capacity of the Salvation Army to adapt itself to whatever need or circumstance presented. The same standard they had borne into the most wretched places of earth in times of peace would do in times of war.

Out there across the waters the Salvation Brothers and Sisters were ministering to the British armies at the front, and now that the American army was going, too, duty seemed very clear; the call was most imperative!

The written pages on her desk loudly demanded attention and the Commander tried to bring her thoughts back to them once more, but again and again the call sounded in her heart.

She lifted her eyes to the wall across the room from her desk where hung the life-like portrait of her Christian-Warrior father, the grand old keen-eyed, wise-hearted General, founder of the movement. Like her father she knew they must go. There was no question about it. No hindrance should stop them. They must go! The warrior blood ran in her veins. In this the world’s greatest calamity they must fulfill the mission for which he lived and died.

“Go!” Those pictured eyes seemed to speak to her, just as they used to command her when he was here: “You must go and bear the standard of the Cross to the front. Those boys are going over there, many of them to die, and some are telling them that if they make the supreme sacrifice in this their country’s hour of need it will be all right with them when they go into the world beyond. But when they get over there under shell fire they will know that it is not so, and they will need Christ, the only atonement for sin. You must go and take the Christ to them.”

Then the Commander bowed her head, accepting the commission; and there in the quiet room perhaps the Master Himself stood beside her and gave her his charge—just as she would later charge those whom she would send across the water—telling her that He was depending upon the Salvation Army to bear His standard to the war.

Perhaps it was at this same high conference with her Lord that she settled it in her heart that Lieutenant-Colonel William S. Barker was to be the pioneer to blaze the way for the work in France.

However that may be he was an out-and-out Salvationist, of long and varied experience. He was chosen equally for his proved consecration to service, for his unselfishness, for his exceptional and remarkable natural courage by which he was afraid of nothing, and for his unwavering persistence in plans once made in spite of all difficulties. The Commander once said of him: “If you want to see him at his best you must put him face to face with a stone wall and tell him he must get on the other side of it. No matter what the cost or toil, whether hated or loved, he would get there!”

Thus carefully, prayerfully, were each one of the other workers selected; each new selection born from the struggle of her soul in prayer to God that there might be no mistakes, no unwise choices, no messengers sent forth who went for their own ends and not for the glory of God. Here lies the secret which makes the world wonder to-day why the Salvation Army workers are called “the real thing” by the soldiers. They were hand-picked by their leader on the mount, face to face with God.

She took no casual comer, even with offers of money to back them, and there were some of immense wealth who pleaded to be of the little band. She sent only those whom she knew and had tried. Many of them had been born and reared in the Salvation Army, with Christlike fathers and mothers who had made their homes a little piece of heaven below. All of them were consecrated, and none went without the urgent answering call in their own hearts.

It was early in June, 1917, when Colonel Barker sailed to France with his commission to look the field over and report upon any and every opportunity for the Salvation Army to serve the American troops.

In order to pave his way before reaching France, Colonel Barker secured a letter of introduction from Secretary-to-the-President Tumulty, to the American Ambassador in France, Honorable William G. Sharp.

In connection with this letter a curious and interesting incident occurred. When Colonel Barker entered the Secretary’s office, he noticed him sitting at the other end of the room talking with a gentleman. He was about to take a seat near the door when Mr. Tumulty beckoned to him to come to the desk. When he was seated, without looking directly at the other gentleman, the Colonel began to state his mission to Mr. Tumulty. Before he had finished the stranger spoke up to Mr. Tumulty: “Give the Colonel what he wants and make it a good one!” And lo! he was not a stranger, but a man whose reform had made no small sensation in New York circles several years before, a former attorney who through his wicked life had been despaired of and forsaken by his wealthy relatives, who had sunk to the lowest depths of sin and poverty and been rescued by the Salvation Army.

Continuing to Mr. Tumulty, he said: “You know what the Salvation Army has done for me; now do what you can for the Salvation Army.”

Mr. Tumulty gave him a most kind letter of introduction to the American Ambassador.

On his arrival in Liverpool Colonel Barker availed himself of the opportunity to see the very splendid work being done by the Salvation Army with the British troops, both in France and in England, visiting many Salvation Army huts and hostels. He also put the Commander’s plans for France before General Bramwell Booth in London.

As early as possible Colonel Barker presented his letter of introduction to the American Ambassador, who in turn provided him with a letter of introduction to General Pershing which insured a cordial reception by him. Mr. Sharp informed Colonel Barker that he understood the policy of the American army was to grant a monopoly of all welfare work to the Y.M.C.A. He feared the Salvation Army would not be welcome, but assured him that anything he could properly do to assist the Salvation Army would be most gladly done. In this connection he stated that he had known of and been interested in the work of the Salvation Army for many years, that several men of his acquaintance had been converted through their activities and been reformed from dissolute, worthless characters to kind husbands and fathers and good business men; and that he believed in the Salvation Army work as a consequence.

On many occasions during the subsequent months, Mr. Sharp was never too busy to see the Salvation Army representatives, and has rendered valuable assistance in facilitating the forwarding of additional workers by his influence with the State Department.

It appeared that among military officers a kind feeling existed toward the Salvation Army, though it was generally thought that there was no opening for their service. Their conception of the Salvation Army was that of street corner meetings and public charity. The officers at that time could not see that the soldiers needed charity or that they would be interested in religion. They could see how a reading-room, game-room and entertainments might be helpful, but anything further than that they did not consider necessary.

Colonel Barker presented his letter of introduction to General Pershing, and on behalf of Commander Booth offered the services of the Salvation Army in any form which might be desired.

General Pershing, who received the Colonel with exceptional cordiality, suggested that he go out to the camps, look the field over, and report to him. Calling in his chief of staff he gave instructions that a side car should be placed at Colonel Barker’s disposal to go out to the camps; and also that a letter of introduction to the General commanding the First Division should be given to him, asking that everything should be done to help him.

The first destination was Gondrecourt, where the First Division Headquarters was established.

The advance guard of the American Expeditionary Forces had landed in France, and other detachments were arriving almost daily. They were received by the French with open arms and a big parade as soon as they landed. Flowers were tossed in their path and garlands were flung about them. They were lauded and praised on every hand. On the crest of this wave of enthusiasm they could have swept joyously into battle and never lost their smiles.

But instead of going to the front at once they were billeted in little French villages and introduced to French rain and French mud.

When one discovers that the houses are built of stone, stuck together mainly by this mud of the country, and remembers how many years they have stood, one gets a passing idea of the nature of this mud about which the soldiers have written home so often. It is more like Portland cement than anything else, and it is most penetrative and hard to get rid of; it gets in the hair, down the neck, into the shoes and it sticks. If the soldier wears hip-boots in the trenches he must take them off every little while and empty the mud out of them which somehow manages to get into even hip-boots. It is said that one reason the soldiers were obliged to wear the wrapped leggings was, not that they would keep the water out, but that they would strain the mud and at least keep the feet comparatively clean.

There were sixteen of these camps at this time and probably twelve or thirteen thousand soldiers were already established in them.

There was no great cantonment as at the camps on this side of the water, nor yet a city of tents, as one might have expected. The forming of a camp meant the taking over of all available buildings in the little French peasant villages. The space was measured up by the town mayor and the battalion leader and the proper number of men assigned to each building. In this way a single division covered a territory of about thirty kilometers. This system made a camp of any size available in very short order and also fooled the Huns, who were on the lookout for American camps.

These villages were the usual farming villages, typical of eastern France. They are not like American villages, but a collection of farm yards, the houses huddled together years ago for protection against roving bands of marauders. The farmer, instead of living upon his land, lives in the village, and there he has his barn for his cattle, his manure pile is at his front door, the drainage from it seeps back under the house at will, his chickens and pigs running around the streets.

These houses were built some five or eight hundred years ago, some a thousand or twelve hundred years. One house in the town aroused much curiosity because it was called the “new” house. It looked just like all the others. One who was curious asked why it should have received this appellative and was told because it was the last one that was built—only two hundred and fifty years ago.

There is a narrow hall or court running through these houses which is all that separates the family from the horses and pigs and cows which abide under the same roof.

The whole place smells alike. There is no heat anywhere, save from a fireplace in the kitchen. There is a community bakehouse.

The soldiers were quartered in the barns and outhouses, the officers were quartered in the homes of these French peasants. There were no comforts for either soldier or officer. It rained almost continuously and at night it was cold. No dining-rooms could be provided where the men could eat and they lined up on the street, got their chow and ate it standing in the rain or under whatever cover they could find. Few of them could understand any French, and all the conditions surrounding their presence in France were most trying to them. They were drilled from morning to night. They were covered with mud. The great fight in which they had come to participate was still afar off. No wonder their hearts grew heavy with a great longing for home. Gloom sat upon their faces and depression grew with every passing hour.

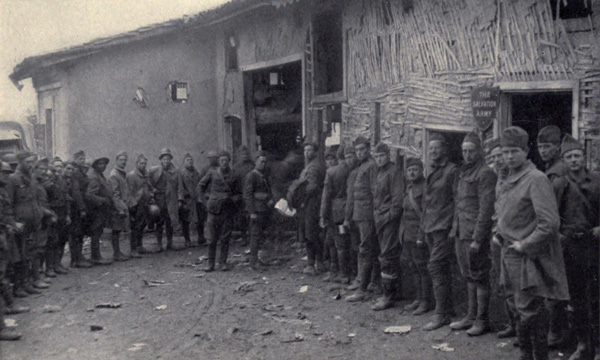

Into these villages one after another came the little military side-car with its pioneer Salvationists, investigating conditions and inquiring the greatest immediate need of the men.

All the soldiers were homesick, and wherever the little car stopped the Salvation Army uniform attracted immediate and friendly attention. The boys expressed the liveliest interest in the possibility of the Salvation Army being with them in France. These troops composed the regular army and were old-timers. They showed at once their respect for and their belief in the Salvation Army. One poor fellow, when he saw the uniform, exclaimed: “The Salvation Army! I believe they’ll be waiting for us when we get to hell to try and save us!”

It appeared that the pay of the American soldier was so much greater than that of the French soldier that he had too much money at his disposal; and this money was a menace both to him and to the French population. If some means could be provided for transferring the soldier’s money home, it would help out in the one direction which was most important at that time.

It will be remembered that the French habit of drinking wine was ever before the American soldier, and with 165 francs a month in his pocket, he became an object of interest to the French tradespeople, who encouraged him to spend his money in drink, and who also raised the price on other commodities to a point where the French population found it made living for them most difficult.

The Salvation Army authorities in New York were all prepared to meet this need. The Organization has one thousand posts throughout the United States commanded by officers who would become responsible to get the soldier’s money to his family or relatives in the United States. A simple money-order blank issued in France could be sent to the National Headquarters of the Salvation Army in New York and from there to the officer commanding the corps in any part of the United States, who would deliver the money in person.

In this way the friends and relatives of the soldier in France would be comforted in the knowledge that the Salvation Army was in touch with their boy; and if need existed in the family at home it would be discovered through the visit of the Salvation Army officer in the homeland and immediate steps taken to alleviate it.

Perhaps this has done more than anything else to bring the blessing of parents and relatives upon the organization, for tens of thousands of dollars that would have been spent in gambling and drink have been sent home to widowed mothers and young wives.

This suggestion appealed very strongly to the military general, who said that if the Salvation Army got into operation it could count upon any assistance which he could give it, and if they conducted meetings he would see that his regimental band was instructed to attend these meetings and furnish the music.

Several chaplains, both Protestant and Catholic, expressed themselves as being glad to welcome the Salvation Army among them.

Among the Regular Army officers there was rather a pessimistic attitude. It was in nowise hostile, but rather doubtful.

One general said that he did not see that the Salvation Army could do any good. His idea of the Salvation Army being associated altogether with the slums and men who were down and out. But on the other hand, he said that he did not see that the Salvation Army could do any harm, even if they did not do any good, and as far as he was concerned he was agreeable to their coming in to work in the First Division; and he would so report to General Pershing.

St. Nazaire, the base, was being used for the reception of the troops as they reached the shores of France. Here was a new situation. The men had been cooped up on transports for several days and on their landing at St. Nazaire they were placed in a rest camp with the opportunity to visit the city. Here they were a prey to immoral women and the officer commanding the base was greatly concerned about the matter and eagerly welcomed the idea of having the Salvation Army establish good women in St. Nazaire who would cope with the problem.

The report given to General Pershing resulted in an official authorization permitting the Salvation Army to open their work with the American Expeditionary Forces, and a suggestion that they go at once to the American Training Area and see what they could do to alleviate the terrible epidemic of homesickness that had broken out among the soldiers.

In the meantime, back in New York, the Commander had not been idle. Daily before the throne she had laid the great concerns of her Army, and daily she had been preparing her first little company of workers to go when the need should call.

There was no money as yet, but the Commander was not to be daunted, and so when the report came from over the water, she borrowed from the banks twenty-five thousand dollars.

She called the little company of pioneer workers together in a quiet place before they left and gave them such a charge as would make an angel search his heart. Before the Most High God she called upon them to tell her if any of them had in his or her heart any motive or ambition in going other than to serve the Lord Christ. She looked down into the eyes of the young maidens and bade them put utterly away from them the arts and coquetries of youth, and remember that they were sent forth to help and save and love the souls of men as God loved them; and that self must be forgotten, or their work would be in vain. She commanded them if even at this last hour any faltered or felt himself unfit for the God-given task, that he would tell her even then before it was too late. She begged them to remember that they held in their hands the honor of the Salvation Army, and the glory of Jesus Christ their Saviour as they went out to serve the troops. They were to be living examples of Christ’s love, and they were to be willing to lay down their lives if need be for His sake.

There were tears in the eyes of some of those strong men that day as they listened, and the look of exaltation on the faces of the women was like a reflection from above. So must have looked the disciples of old when Jesus gave them the commission to go into all the world and preach the gospel. They were filled with His Spirit, and there was a look of utter joy and self-forgetfulness as they knelt with their leader to pray, in words which carried them all to the very feet of God and laid their lives a willing sacrifice to Him who had done so much for them. Still kneeling, with bowed heads, they sang, and their words were but a prayer. It is a way these wonderful people have of bursting into song upon their knees with their eyes closed and faces illumined by a light of another world, their whole souls in the words they are singing—“singing as unto the Lord!” It reminds one of the days of old when the children of Israel did everything with songs and prayers and rejoicing, and the whole of life was carried on as if in the visible presence of God, instead of utterly ignoring Him as most of us do now.

The song this time was just a few lines of consecration:

“Oh, for a heart whiter than snow!

Saviour Divine, to whom else can I go?

Thou who hast died, loving me so,

Give me a heart that is whiter than snow!”

The dramatic beauty of the scene, the sweet, holy abandonment of that prayer-song with its tender, appealing melody, would have held a throng of thousands in awed wonder. But there was no audience, unless, perchance, the angels gathered around the little company, rejoicing that in this world of sin and war there were these who had so given themselves to God; but from that glory-touched room there presently went forth men and women with the spirit in their hearts that was to thrill like an electric wire every life with which it came in contact, and show the whole world what God can do with lives that are wholly surrendered to Him.

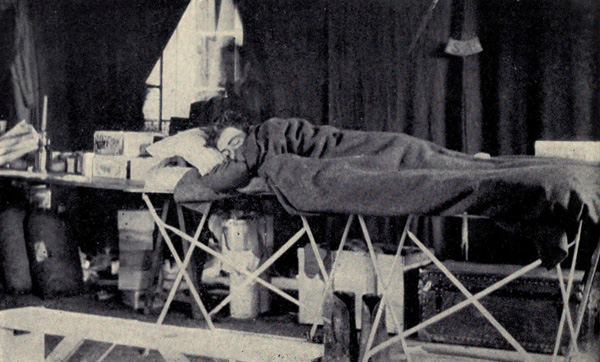

She called the little company of workers together and gave them such a charge as would make an angel search his heart

It was a bright, sunny afternoon, August 12th, when this first party of American Salvation Army workers set sail for France.

No doubt there was many a smile of contempt from the bystanders as they saw the little group of blue uniforms with the gold-lettered scarlet hatbands, and noticed the four poke bonnets among the number. What did the tambourine lassies know of real warfare? To those who reckoned the Salvation Army in terms of bands on the street corner, and shivering forms guarding Christmas kettles, it must have seemed the utmost audacity for this “play army” to go to the front.

When they arrived at Bordeaux on August 21st they went at once to Paris to be fitted out with French uniforms, as General Pershing had given them all the rank of military privates, and ordered that they should wear the regulation khaki uniforms with the addition of the red Salvation Army shield on the hats, red epaulets, and with skirts for the women.

A cabled message had reached France from the Commander saying that funds to the extent of twenty-five thousand dollars had been arranged for, and would be supplied as needed, and that a party of eleven officers were being dispatched at once. After that matters began to move rapidly.

A portable tent, 25 feet by 100 feet, was purchased and shipped to Demange;—and a touring car was bought with part of the money advanced.

Purchasing an automobile in France is not a matter merely of money. It is a matter for Governmental sanction, long delay, red tape—amazing good luck.

At the start the whole Salvation Army transportation system consisted of this one first huge limousine, heartlessly overdriven and overworked. For many weeks it was Colonel Barker’s office and bedroom. It carried all of the Salvation Army workers to and from their stations, hauled all of the supplies on its roof, inside, on its fenders, and later also on a trailer. It ran day and night almost without end, two drivers alternating. It was a sort of super-car, still in the service, to which Salvationists still refer with an affectionate amazement when they consider its terrific accomplishments. It hauled all of the lumber for the first huts and a not uncommon sight was to see it tearing along the road at forty miles an hour, loaded inside and on top with supplies, several passengers clinging to its fenders, and a load of lumber or trunks trailing behind. For a long time Colonel Barker had no home aside from this car. He slept wherever it happened to be for the night—often in it, while still driven. One night he and a Salvation Army officer were lost in a strange woods in the car until four in the morning. They were without lights and there were no real roads.

Later, of course, after long waiting, other trucks were bought and to-day there are about fifty automobiles in this service. Chauffeurs had to be developed out of men who had never driven before. They were even taken from huts and detailed to this work.

In this first touring car Colonel Barker with one of the newly arrived adjutants for driver, started to Demange.

Twenty kilometers outside of Paris the car had a breakdown. The two clambered out and reconnoitered for help. There was nothing for it but to take the car back to Paris. A man was found on the road who was willing to take it in tow, but they had no rope for a tow line. Over in the field by the roadside the sharp eyes of the adjutant discovered some old rusty wire. He pulled it out from the tangle of long grass, and behold it was a part of old barbed-wire entanglements!

In great surprise they followed it up behind the camouflage and found themselves in the old trenches of 1914. They walked in the trenches and entered some of the dugouts where the soldiers had lived in the memorable days of the Marne fight. As they looked a little farther up the hillside they were startled to see great pieces of heavy field artillery, their long barrels sticking out from pits and pointing at them. They went closer to examine, and found the guns were made of wood painted black. The barrels were perfectly made, even to the breech blocks mounted on wheels, the tires of which were made of tin. They were a perfect imitation of a heavy ordnance piece in every detail. Curious, wondering what it could mean, the two explorers looked about them and saw an old Frenchman coming toward them. He proved to be the keeper of the place, and he told them the story. These were the guns that saved Paris in 1914.

The Boche had been coming on twenty kilometers one day, nineteen the next, fourteen the next, and were daily drawing nearer to the great city. They were so confident that they had even announced the day they would sweep through the gates of Paris. The French had no guns heavy enough to stop that mad rush, and so they mounted these guns of wood, cut away the woods all about them and for three hundred meters in front, and waited with their pitifully thin, ill-equipped line to defend the trenches.

Then the German airplanes came and took pictures of them, and returned to their lines to make plans for the next day; but when the pictures were developed and enlarged they saw to their horror that the French had brought heavy guns to their front and were preparing to blow them out of France. They decided to delay their advance and wait until they could bring up artillery heavier than the French had, and while they waited the Germans broke into the French wine cellars and stole the “vin blanche” and “vin rouge.” The French call this “light” wine and say it takes the place of water, which is only fit for washing; but it proved to be too heavy for the Germans that day. They drank freely, not even waiting to unseal the bottles of rare old vintage, but knocked the necks off the bottles against the stone walls and drank. They were all drunk and in no condition to conquer France when their artillery came up, and so the wooden French guns and the French wine saved Paris.