SCENE—The Pit during Pantomime Time.

The Overture is beginning.

An Over-heated Matron (to her Husband). Well, they don't give you much room in 'ere, I must say. Still, we done better than I expected, after all that crushing. I thought my ribs was gone once—but it was on'y the umbrella's. You pretty comfortable where you are, eh. Father?

Father. Oh, I'm right enough, I am.

Jimmy (their Son; a small boy, with a piping voice). If Father is, it's more nor what I am. I can't see, Mother, I can't!

His Mother. Lor' bless the boy! there ain't nothen to see yet; you'll see well enough when the Curting goes up. (Curtain rises on opening scene). Look, JIMMY, ain't that nice, now? All them himps dancin' round, and real fire comin' out of the pot—which I 'ope it's quite safe—and there's a beautiful fairy just come on, dressed so grand, too!

Jimmy. I can't see no fairy—nor yet no himps—no nothen! [He whimpers.

His Mother (annoyed). Was there ever such a aggravating boy to take anywheres! Set quiet, do, and don't fidget, and look at the hactin'!

Jimmy. I tell yer I can't see no hactin', Mother. It ain't my fault—it's this lady in front o' me, with the 'at.

Mother (perceiving the justice of his complaints). Father, the pore boy says he can't see where he is, 'cause of a lady's hat in front.

Father. Well, I can't 'elp the 'at, can I? He must put up with it, that's all!

Mother. No—but I thought, if you wouldn't mind changing places with him—you're taller than him, and it wouldn't be in your way 'arf so much.

Father. It's always the way with you—never satisfied, you ain't! Well, pass the boy across—I'm for a quiet life, I am. (Changing seats.) Will this do for you?

[He settles down immediately behind a very large, and furry, and feathery hat, which he dodges for some time, with the result of obtaining an occasional glimpse of a pair of legs on the stage.

Father (suddenly). D—— the 'at!

Mother. You can't wonder at the boy not seeing! P'raps the lady wouldn't might taking it off, if you asked her?

Father. Ah! (He touches The Owner of the Hat on the shoulder.) Excuse me, Mum, but might I take the liberty of asking you to kindly remove your 'at? [The Owner of the Hat deigns no reply.

Father (more insistently). Would you 'ave any objection to oblige me by taking off your 'at, Mum? (Same result.) I don't know if you 'eard me, Mum, but I've asked you twice, civil enough, to take that 'at of yours off. I'm a playin' 'Ide and Seek be'ind it 'ere!

[No answer.

The Mother. People didn't ought to be allowed in the Pit with sech 'ats! Callin' 'erself a lady—and settin' there in a great 'at and feathers like a 'Ighlander's, and never answering no more nor a stuffed himage!

Father (to the Husband of The Owner of the Hat). Will you tell your good lady to take her 'at off, Sir, please?

The Owner of the Hat (to her Husband). Don't you do nothing of the sort, SAM, or you'll 'ear of it!

The Mother. Some people are perlite, I must say. Parties might beyave as ladies when they come in the Pit! It's a pity her 'usband can't teach her better manners!

The Father. 'Im teach her! 'E knows better. 'E's got a Tartar there, 'e 'as!

The Owner of the Hat. SAM, are you going to set by and hear me insulted like this?

Her Husband (turning round tremulously). I—I'll trouble you to drop making these personal allusions to my wife's 'at, Sir. It's puffickly impossible to listen to what's going on on the stage, with all these remarks be'ind!

The Father. Not more nor it is to see what's going on on the stage with that 'at in front! I paid 'arf-a-crown to see the Pantermime, I did; not to 'ave a view of your wife's 'at!... 'Ere, MARIA, blowed if I can stand this 'ere game any longer. JIMMY must change places again, and if he can't see, he must stand up on the seat, that's all!

[JIMMY is transferred to his original place, and mounts upon the seat.

A Pittite behind Jimmy (touching up JIMMY's Father with an umbrella). Will you tell your little boy to set down, please, and not block the view like this?

Jimmy's Father. If you can indooce that lady in front to take off her 'at, I will—but not before. Stay where you are, JIMMY, my boy.

The Pittite behind. Well, I must stand myself then, that's all. I mean to see, somehow! [He rises.

People behind him (sternly). Set down there, will yer?

[He resumes his seat expostulating.

Jimmy. Father, the gentleman behind is a pinching of my legs!

Jimmy's Father. Will you stop pinching my little boy's legs! He ain't doing you no 'arm—is he?

The Pinching Pittite. Let him sit down, then!

Jimmy's Father. Let the lady take her 'at off!

Murmurs behind. Order, there! Set down! Put that boy down! Take orf that 'at! Silence in front, there! Turn 'em out! Shame!... &c., &c.

The Husband of the O. of the H. (in a whisper to his Wife). Take off the blessed 'at, and have done with it, do!

The O. of the H. What—now? I'd sooner die in the 'at!

[An Attendant is called.

The Attendant. Order, there, Gentlemen, please—unless you want to get turned out! No standing allowed on the seats—you're disturbing the performance 'ere, you know!

[JIMMY is made to sit down, and weeps silently; the hubbub gradually subsides—and The Owner of the Hat triumphs—for the moment.

Jimmy's Mother. Never mind, my boy, you shall have Mother's seat in a minute. I dessay, if all was known, the lady 'as reasons for keeping her 'at on, pore thing!

The Father. Ah, I never thought o' that. So she may. Very likely her 'at won't come off—not without her 'air!

The Mother. Ah, well, we musn't be 'ard on her, if that's so.

The O. of the H. (removing the obstruction). I 'ope you're satisfied now, I'm sure?

The Father (handsomely). Better late nor never, Mum, and we take it kind of you. Though, why you shouldn't ha' done it at fust, I dunno; for you look a deal 'ansomer without the 'at than, what you did in it—don't she, MARIA?

The O. of the H. (mollified). SAM, ask the gentleman behind if his boy would like a ginger-nut.

[This olive-branch is accepted; compliments pass; cordiality is restored, and the Pantomime proceeds without further disturbance.

The Committee waited impatiently the arrival of the Great and Good Man. It was their duty to obtain a donation—an ample one—from the Millionnaire whose charity was renowned far and wide, from one end of the world to the other. At length he appeared before them.

"What can I do for you?" he asked, with a smile that absolutely shone with benevolence.

"You know, Sir, that the claims of the poor in the Winter are numerous, and difficult to meet?"

"Certainly I do," returned the Man of Wealth, "and hope that you are about to ask me for a subscription."

"Indeed we were," cried the spokesman of the Committee, his eyes filling with grateful tears. "May I put you down for five pounds?"

"Five pounds!" echoed the Millionnaire, impatiently, "What is five pounds?—five thousand is much more like the figure! Now, I will give you five thousand pounds on one condition."

"Name it!" cried the Deputation in a breath.

"The simplest thing in the world," continued the Millionnaire. "I will give you five thousand pounds on the condition that you get ninety-nine other fellows to do the same. Nay, you shall thank me when all is collected. I can wait till then."

The above words were spoken more than thirty years ago. Since then the Deputation have been waiting for the other fellows—and so has the Millionnaire!

PROFESSOR VIRCHOW seems by no means Koch-sure about the tuberculosis remedy. Indeed Professor KOCH finds that there is not only "much virtue in an 'if,'" but much "if" in a VIRCHOW! He is inclined to sing with SWINBURNE:—

"Come down, and redeem us from VIRCHOW."

Friend of Ireland:—

"Wordy Knife-Grinder! Whither are you going?

Dark is your way—your wheel looks out of order—

Mitchelstown palls, and there seems no more spell in

O'BRIEN's breeches!

"Wordy Knife-Grinder, little think the proud ones,

Who in their speeches prate about their Union-

Ism, what hard work 'tis to keep a Party

Tightly together!

"Tell me, Knife-Grinder, what your little game is.

Do you mean playing straight with me and others?

Or would you jocky Erin like a confounded

Saxon attorney?

"Give us a glimpse of that same Memorandum!

Pledge yourself clear to what needs no explaining!

Prove that your plan is not quite a sham, sly-whittled

Down into nullity!

[pg 51]"Ere I depart (if go I must, TIM HEALY)

Give me a pledge that I'm not sold for nothing.

Tell us in plain round words, without evasion, the

True Hawarden story."

Knife-Grinder.

"Story! God bless yer! I have none to tell, Sir!

Never tell stories, I; 'tis my sole business

This Wheel to turn with treadle and cry, 'Knives and

Scissors to grind O!'

"Constabulary? Question of Land Purchase?

Number of Irish Members due in justice?

Never said aught about 'em; don't intend to—

Not for the present.

"I shall be glad to do what honour urgeth;

Grind on alone, if you will give me carte-blanche,

Make room for JUSTIN, and forbear to meddle

With politics, Sir!"

Friend of Ireland.

"I give thee carte-blanche? I will see thee blowed first—

Fraud! whom no frank appeal can move to frankness—

Sophist, evasive, garrulous, word-web-spinning

Subtle Old Spider!!!"

[Kicks the Knife-Grinder, overturns his Wheel, and exit in a fury of patriotic enthusiasm and forcible language.

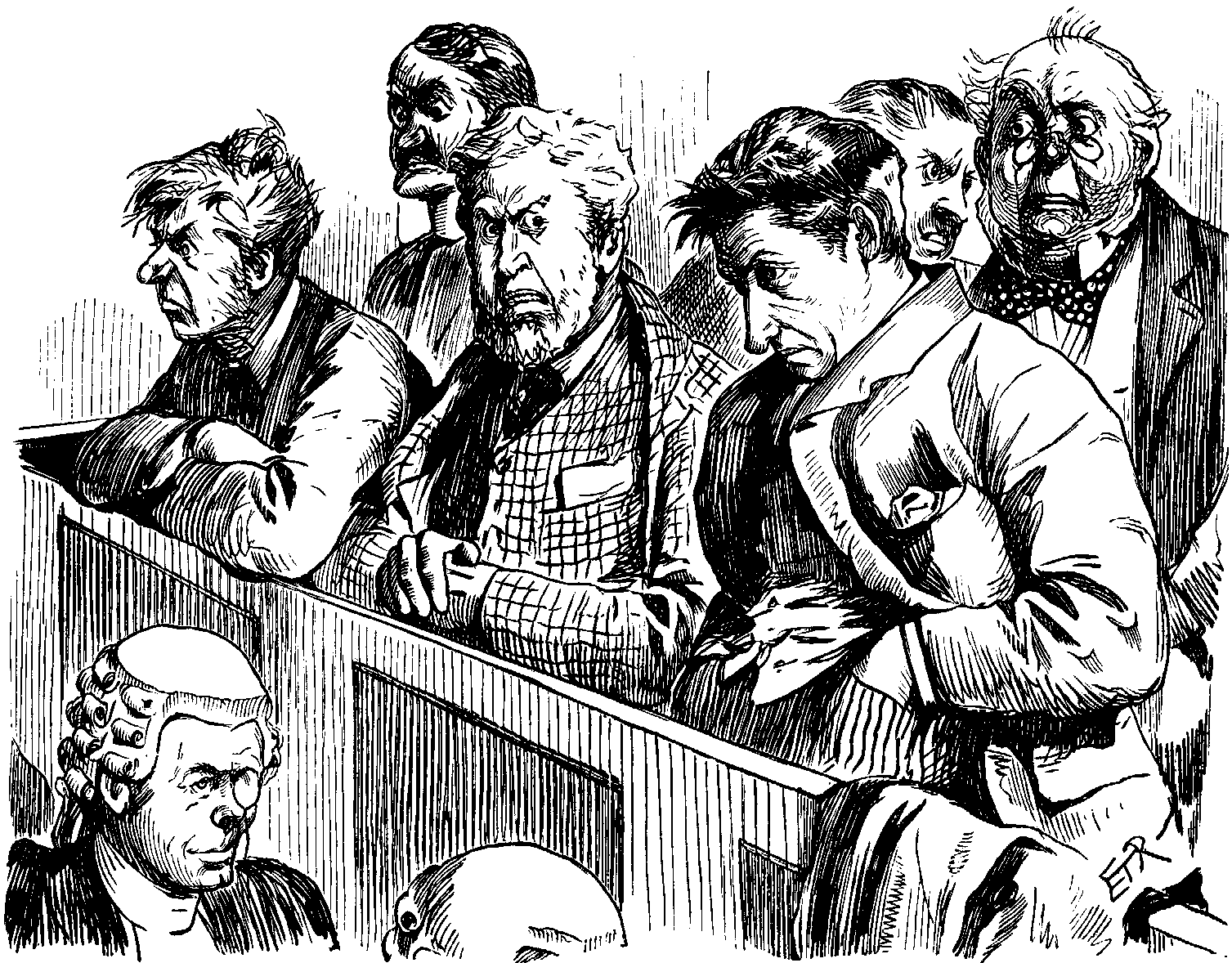

Though in some quarters a better feeling was reported to have prevailed, still, according to latest accounts, the outlook can scarcely be regarded as satisfactory. A meeting of the Amalgamated Engineering Tram-Drivers' Mutual Stand-Shoulder-to-Shoulder Strangulation Society was held on Glasgow Green yesterday afternoon, at which, amid a good deal of boisterous interruption, several delegates addressed the assembled audience and recounted their recent experiences up to date. There were still 1700 of the Company's old hands out of work, and though, thanks to the profound enthusiasm, "their just cause" had excited amidst the Trade Societies in the South, by which, owing to subscriptions from no less important bodies than the Bootmakers' Benevolent Grandmothers' Association, and Superannuated Undertakers' Orphan Society, they had been able to stay out and defy the Company, receiving all the while, every man of them, a stipend of 3s. 9d. a-week, still they had almost come to the end of their resources, and all that they had in hand towards next week's fund for distribution, was £1 13s. 7-1/2d., received in coppers from the Deputy-Chairman of the Metropolitan Boys' Boot-blacking Brigade, accompanied with an intimation that that help must be regarded as the last that can be counted on from that quarter. Under these circumstances it became a question whether it was not almost time to consider some terms of compromise.

In the above sense one of the speakers addressed the meeting, but he was speedily followed by another, who insisted that, "come what might," they would stick to their latest terms, which were, a three-hours' day—(loud cheers)—and time-and-three-quarters for any work expected after three o'clock in the afternoon. (Prolonged cheering.)

A Delegate here rose, and said it was all very well their cheering, but could they get it? (A Voice, "We'll try!") For his part, the speaker continued, he had had enough of trying. With wife and children starving at home, he had only one course open to him, and that was, to knock under to the Company and their ten-hours' day, if they would have him. (Groans, amid which the Speaker had his hat knocked over his eyes, and was kicked out of the assembly.)

The discussion was then continued, much in the same vein, and eventually culminated in a free fight, in which the Chairman got his head broken, on declaring that a Motion further limiting the working day to two hours and a half, was lost by a narrow majority.

Yesterday afternoon the Directors' Mutual Anti-Labour Protection Company met at their Central Offices for the despatch of their usual business. The ordinary Report was read, which announced that though the affairs of three great Railway Companies had "gone" literally "to the dogs," still, the Directors of each had to be congratulated on showing a firm front, in refusing to acknowledge even the existence of their employés. The usual congratulatory Motions were put, pro formâ, and passed, and, amid a general manifestation of gloomy satisfaction, the meeting was further adjourned.

Rudyard Kipling has hit on a picturesque plan;

He describes in strong language "the savage in Man."

Whilst amongst the conventions he raids and he ravages.

We'd like just a leetle more "Man" in his savages.

Jones (who has just told his best Story, and been rewarded with a gentle smile). "UPON MY WORD, WOMEN HAVEN'T GOT THE REAL SENSE OF HUMOUR! WHY, WHEN I HEARD THAT STORY FOR THE FIRST TIME, ONLY LAST WEEK, I SIMPLY ROARED!"

Miss Smith. "SO DID I—ONLY IT WAS LAST YEAR!"

We sent our Musical Box (Cox being unable to accompany him on the piano or any other instrument, by reason of the severe weather) to hear STAVENHAGEN at St. James's Hall, Thursday last, the 22nd. Our Musical B. was nearly turned out of the hall, he was in such ecstasies of delight over a Beethovenly concerto, which "bangs Banagher," he said, subsequently translating the expression by explaining, "that is, beats BEETHOVEN." Our M.B. wept over a cadenza composed by the performer, and was only restored by the appearance—her first—of Madame STAVENHAGEN, who gave somebody's grand scena far better, probably, than that somebody could have given it himself, set as it was to fine descriptive music by the clever STAVENHAGEN, which delighted all hearers, especially those who were Liszt-eners. "Altogether," writes our Musical Box, "a very big success. Music is thirsty work. I am now about to do a symphony in B. and S."

A poet in the Forum asks the question,

"Is Verse in Danger?" 'Tis a wild suggestion!

Is Verse in Danger? Nay, that's not the curse;

Danger (of utter boredom) is in Verse!

"ODD MAN OUT."—On Saturday last, the last among the theatrical advertisements in the Daily Telegraph was the mysterious one, "MR. CHARLES SUGDEN AT LIBERTY," and then followed his address. "At Liberty!" What does it mean? Has he been—it is a little difficult to choose the right word, but let us say immured—has he been immured in some cell?—for it does sound like a "sell" of another sort—and has he at last effected a sensational escape? No doubt CHARLES, our friend, will be able to offer the public a satisfactory explanation when he re-appears on the Stage which suffers from his absence.

What is to be admired in ENERY HAUTHOR JONES is not so much his work but his pluck,—for has he not, in the first place, overcome the prudery of the Lord Chamberlain's Licensing Department, and, in the second place, has he not introduced on the boards of the Haymarket a good old-fashioned Melodrama, brought "up to date," and disguised in a Comedy wrapper? Walk in, Ladies and Gentlemen, and see The Dancing Girl, a Comedy-Drama shall we call it, or, generically, a Play? wherein the prominent figures are a wicked Duke,—vice the "wicked Baronet," now shelved, as nothing under the ducal rank will suit us nowadays, bless you!—a Provincial Puritan family, an honest bumpkin lover, a devil of a dancing woman who lives a double-shuffling sort of life, an angel of a lame girl,—who, of course, can't cut capers but goes in for coronets,—a sly, unprincipled, and calculating kind of angel she is too, but an audience that loves Melodrama is above indulging in uncharitable analysis of motive,—a town swell in the country, a more or less unscrupulous land-agent, and a genuine, honest "heavy father," of the ancient type, with a good old-fashioned melodramatic father's curse ready at the right moment, the last relic of a bygone period of the transpontine Melodrama, which will bring tears to the eyes of many an elderly playgoer on hearing the old familiar formula, in the old familiar situation, reproduced on the stage of the modern Haymarket as if through the medium of a phonophone.

At all events, Drusilla Ives, alias "the Dancing Girl "—though as to where she dances, how she dances, and when she dances, we are left pretty well in the dark, as she only gives so slight a taste of her quality that it seemed like a very amateurish imitation of Miss KATE VAUGHAN in her best day,—Drusilla Ives is the mistress, neither pure nor simple, of the Duke of Guisebury,—a title which is evidently artfully intended by the, at present, "Only JONES" to be a compound of the French "Guise" and the English "Bury,"—who from his way of going on and playing old gooseberry with his property, might have been thus styled with advantage: and so henceforth let us think and speak of him as His Grace or His Disgrace the Duke of Gooseberry.

This Duke of Gooseberry visits, "quite unbeknown,"—being, for this occasion only, the Duke of Disguisebury,—his own property, the Island of St. Endellion, just to see, we suppose, what sort of people the Quaker family may be from which his mistress, the Dancing Quakeress (and how funny she used to be at the Music Halls and at the Gaiety!), has sprung. For some reason or other, the Dancing Quakeress has gone to stay a few weeks with her family in the country, and while this hypocritical Daughter of HERODIAS is with her Quaker belongings at prayers in the Meeting House, the spirit moveth her to come out, and to come out uncommonly strong, as, within a yard or so of the building, she laughs and talks loudly with Gooseberry, and then in a light-hearted way she treats the Dook to some amateur imitations of ELLEN TERRY, finishing up with a reminiscence of KATE VAUGHAN; all of which al fresco entertainment is given for the benefit of the aforesaid Gooseberry within sound of the sermon and within sight of the Meeting House windows. Suddenly her rustic Quaker lover, a kind of Ham Peggotty, lounges out of the Conventicle, which, as these persons seem to leave and enter just when it suits them, ought rather to be called a Chapel-of-Ease,—and, like the clown that he is, says in effect, "I'm a-looking at yer! I've caught yer at it!" Dismay of Dook and Dancer!! then Curtain on a most emphatically effective situation.

The Second Act is far away the best of the lot, damaged, however, by vain repetitions of words and actions. To the house where Miss Dancing Girl is openly living under the protection of Gooseberry, the Duke's worthy Steward actually brings his virtuous and ingenuous young daughter! If ever there were a pair of artful, contriving, scheming humbugs, it is this worthy couple. Because the Duke saved her from being run over by his own horses, therefore she considers herself at liberty to limp after him, and round him, and about him, on every possible occasion, to say sharp, priggish things to him, to make love to him, and in the Third Act so craftily to manage as to spot him just as he is about to drink off a phial of poison, which operation, being preceded by a soliloquy of strong theatrical flavour and considerable length, gives the lame girl a fair chance of hobbling down the stairs and arresting the thus "spotted Nobleman's" arm at the critical moment. Curtain, and a really fine dramatic situation. "Which nobody can deny."

It is in this same Third Act that the fine old crusted melodramatic curse is uncorked, and a good imperial quart of wrath is poured out on his dancing daughter's head by the heavy father, who, in his country suit, forces his way into the gilded halls of the Duke's mansion, past the flunkeys, the head butler, and all the rest of the usual pampered menials. An audience that can accept this old-fashioned cheap-novel kind of clap-trap, and witness, without surprise, the marvellous departure of all the guests, supperless, for no assigned cause, or explicable reason, not even an alarm of fire having been given, will swallow a considerable amount.

The Fourth Act is an anticlimax, and shows up the faulty construction of the drama. Of course the news comes that the Dancing Girl is dead, and this information is brought by a Sainte Nitouche of a "Sister" of some Theatrical Order (not admitted after half-past seven), whose very appearance is a suggestio falsi. Equally, of course, a letter is found, which, as exculpating Gooseberry, induces the old cuss of a Puritan father to shake hands with the converted "Spotted Nobleman"; but, be it remembered, the Dook is still his landlord, and the value of the property is going up considerably. Then it appears that the old humbug of an agent has sagaciously speculated in the improvement of the island, and poor Gooseberry feels under such an obligation to that sly puss of an agent's daughter, that, in a melancholy sort of way, he offers her his hand, which she, the artful little hussy of a Becky Sharp, with considerable affectation of coyness, accepts, and down goes the Curtain upon as unsatisfactory and commonplace a termination to a good Melodrama as any [pg 53] Philistine of the Philistines could possibly wish. It would have been a human tragedy indeed had poor Gooseberry poisoned himself, and the girl whose life he had saved had arrived just too late, only to die of a broken heart. But that "is quite another story."

The piece is well played all round, especially by the men. Mr. TREE is excellent, except in the ultra-melodramatic parts, where he is too noisy. The very best thing he does is the perfect finish of the Second Act, when, without a word, he sits in the chair before the fire lost in dismal thought. This is admirable: as perfect in its dramatic force as it is true to nature. It is without exception the best thing in the whole piece. Mr. F. KERR as Reginald Slingsby, achieves a success unequalled since Mr. BANCROFT played the parvenu swell Hawtree. It should be borne in mind that Mr. KERR only recently played admirably the poor stuttering shabby lover in The Struggle for Life. Il ira loin, ce bon M. KERR. Miss JULIA NEILSON looks the part to the life: when she has ceased to give occasional imitations of Miss ELLEN TERRY, and can really play the part as well as she looks it, then nothing more could be possibly desired. All the others as good as need be, or can be.

["No game was ever yet invented which held the female mind in thrall save by indirect means. Where would croquet have been, so far as the Ladies were concerned, without its Curates, or lawn-tennis without its 'Greek gods' ... If men played for nothing, they would find it dull enough."—JAMES PAYN]

'Tis mighty well for Menfolk at Womankind to gibe,

And swear they do not care for games without some lure or bribe,

But e'en in JAMES PAYN's armour there seems some weakish joints;

He does not care for "glorious Whist" unless for "sixpenny points!"

Whist! Whist! Whist! It charms the Bogey, Man:

Whist! Whist! Whist! He'll play it when he can.

But "pointless Whist," as PAYN admits, is not at all his plan;

You must have "money on" to please the Bogey, Man!

Now, Ladies like to play "for love," a fault male hucksters blame,

But only sordid souls deny that is the true "grand game."

Man's vulgarer ambition's not just to play well and win;

His eye is ever on the stakes, his interest on the "tin."

Whist! Whist! Whist! That blatant Bogey, Man!

Whist! Whist! Whist! He'll flout us when he can.

"Indirect means" though, after all, are portions of his plan;

For all his brag he loves the "swag," the Bogey, Man!

[Mr. CHAMBERLAIN presided lately at a Deaf-and-Dumb Meeting.]

JOSEPH reflecteth:—

Deaf-mutes make the best audience, I see;

They gave me no rude flood of gibes to stem.

True, they were deaf, and so could not hear me,

But they were dumb, so I could not hear them!

MADAME ROLAND RE-EDITED (from a sham-Japanese point of view).—O LIBERTY! what strange (decorative) things are done in thy name!

["It is impossible for warrant-officers in the Navy not to see that they are placed at a disadvantage as compared with non-commissioned officers in the Army, and it must be very difficult to persuade them that the two cases are so essentially different as to afford no real ground for grievance."—The "Times," on "An Earnest Appeal on Behalf of the Rank and File of the Navy."]

Jack Tar to Tommy Atkins, loquitur:—

TOMMY ATKINS, TOMMY ATKINS, penmen write pertikler fine

Of the Wooden Walls of England, and likeways the Thin Red Line;

But for those as form that Line, mate, or for those as man them Walls,

Scribes don't seem so precious anxious to kick up their lyric squalls.

Not a bit of it, my hearty; for one reason—it don't pay;

There is small demand, my TOMMY, for a DIBDIN in our day.

Oh, I know that arter dinner your M.P.'s can up and quote

Tasty tit-bits from old CHARLEY, which they all reel off by rote;

But if there is a cherub up aloft to watch poor JACK,

That there cherub ain't a poet,—bards are on another tack.

TOMMY ATKINS, TOMMY ATKINS, BULL is sweet on "loyal toasts,"

And he spends his millions freely on his squadrons and his hosts,

But there isn't much on't, messmate, not so fur as I can see,

Whether 'tis rant or rhino, that gets spent on you and me.

Still the Times has took our case up,—werry handsome o' the Times!—

I have heard it charged with prejudice, class-hate, and similar crimes,

But it shows it's got fair sperret and a buzzum as can feel

When it backs us with a "Leader" arter printing our "Appeal."

You are better off, my TOMMY, than the Navy Rank and File,

You may chance to get promotion,—arter waiting a good while—

But the tip-top of Tar luck's to be a Warrant Officer;

We ain't like to get no further, if we even get as fur.

'Tain't encouraging, my hearty. As for me, I'm old and grey,

'Tis too late now for promotion if it chanced to come my way;

And my knowledge, and my patter, and my manners—well I guess

They mayn't be percisely fitted for a dandy ward-room mess.

But the Navy of the Future, TOMMY ATKINS, is our care,

We have gone through many changes, and for others must prepare.

It will make the Navy popular, more prospect of advance;

And what I say is, TOMMY,—let the young uns have a chance!

Some I know will cry "Impossible," and slate the scheme like fun.

Most good things are "impossible," my TOMMY,—till they're done!

Quarter-decks won't fill from fokesels, not to any great extent;

But, give good men a better chance! I guess that's all that's meant.

As the Times says, werry sensible and kind-like, prejudice,

Though strong at first, dies quickly, melts away like thaw-struck ice;

If every brave French soldier, with a knapsack on his back,

May find a Marshal's baton at the bottom of that pack,

Why should not a true British Tar, with pluck, and luck, and wit,

Find at last a "Luff's" commission hidden somewheres in his kit?

10 P.M.—Slip out of Opera and take somebody else's overcoat from cloak-room when nobody is looking, jump into a four-wheeler, and drive to station. Am recognised, and a special train is called out. Give them the slip, and get into a horse-box of third-class omnibus-train just about to start.

10.15 P.M. to 2.30 A.M.—Still in horse-box.

2.45 AM.—Stop at a big town. Hurry out. Stopped for ticket. Throw off disguise of somebody else's overcoat, and declare myself. Guard called out to escort me. When they are looking the other way, hide under refreshment-counter, and get out of station unobserved on all-fours. Am collared by a policeman. Again have to declare myself. Give policeman twenty marks, bind him to silence, and borrow his official cloak. Find out Burgomaster's address. Hammer at his front door till I have stirred up the whole household.

4 A.M. to 5 A.M.—Find out the Archbishop. Bang at his front door till he puts his head out of window, and wants to know "What on earth's the matter?" Hide round the corner. Repeat same business, with more or less success, at the residence of the Chief Justice, then at that of the Clerk of the Peace, and at those of any other officials I can call to mind, winding up by a regular good row at that of the General in Command. Trumpeter comes out. Take bugle from him, and give the call. General in Command rubs his eyes sleepily, and says he'll be down presently.

5 A.M.—Hurry back to station. Catch early cattle-train going back to Berlin. Jump on engine, and declare myself. Wire approach down line, and tear away with the cattle, at seventy miles an hour, getting back to Berlin just in time for breakfast. Fancy I woke them up! Altogether, a very enjoyable outing.

Jonathan (who has been reading the Articles on "The Negro Question in the United States," in the English "Times") loq:—

It may be ez you're right, JOHN,

And both my hands are full;

You know ez I can fight, JOHN,

(I've wiped out "Sitting Bull").

Ole Uncle S. sez he, "I guess

We see our fix," sez he.

"The 'Thunderer's' paw lays down the law,

Accordin' to J.B.

To square it's left to me!"

Blood ain't so cool as ink, JOHN;

Big words are easy wrote;

The "coons"—well, you don't think, JOHN,

I'll let 'em cut my throat.

Ole Uncle S. sez he, "I guess

Ghost-dance must stop," sez he.

"Suppose the 'braves' and black ex-slaves

Hed b'longed to ole J.B.

Insted of unto me?"

Ten art'cles in your Times, JOHN,

Hev giv me good advice.

I mind th' old Slavery crimes, JOHN.

I don't need tellin' twice.

Ole Uncle S. sez he, "I guess,

I only guess," sez he,

"Seven million blacks on his folks' backs

Would kind o' rile J.B.

Ez much ez it riles me!"

The Red Man,—well, I s'pose, JOHN,

We'll hev to wipe him aout.

Sech pizonous trash ez those, JOHN,

The world kin do without.

Ole Uncle S. sez he, "I guess

Injuns must go," sez he.

"COOPER's Red Man won't fit our plan,

Though he once witched J.B.

As once he fetched e'en me!"

The Black Man! Ah, that's wuss, JOHN.

The chaps wuz right, ay joost,

Who said the Slavery cuss, JOHN,

Wud yet come home to roost.

Ole Uncle S. sez he, "I guess

The problem set," sez he,

"By that derned Nig. is black and big,

And fairly puzzles me,

Ez it wud do J.B."

Your Times would right our wrongs, JOHN,

—Always wuz sweet on us!—

But on dilemma's prongs, JOHN,

To fix me don't you fuss.

Ole Uncle S. sez he, "I guess,

Though physic's good," sez he,

"It doesn't foller that he can swaller

Prescriptions signed J.B.

Put up by you for me!"

Thet swaggerin' black buck Nig., JOHN,

Is jest a grown-up kid;

Ez happy as a —— pig, JOHN,

When doin' wut he's bid.

Ole Uncle S. sez he, "I guess

He's hateful when he's free.

Equal with him, that dark-skinn'd limb?

No; that will not suit me,

More than it wud J.B.!"

Emigrate the whole lot, JOHN?

Well, that's a tallish task!

In Afric's centre hot, JOHN,

Send 'em to breed and bask?

Ole Uncle S. sez he, "I guess

I'd be right glad," sez he,

"But—will they go? 'Tain't done, you know,

As easy as J.B.

Wud settle it—for me!"

Rouge—there I see my way, JOHN.

But Noir—thet's hard to front!

It wun't be no child's play, JOHN,

Seven million Nigs to shunt.

Ole Uncle S. sez he, "I guess

We've a hard row," sez he,

"To hoe just now, but thet, somehow,

I fancy, friend J.B.,

Your Times may leave to me!"

[Left considering it.

[Mr. SANTLEY, who has been long absent in Australia, reappeared at St. James's Hall on Jan. 19, and was received with great enthusiasm.]

Back from your Australian trip!

Punch, my CHARLES, your fist must grip.

You have lighted on a time

When we're all chill, choke, and grime.

'Twere no marvel, O great baritone,

Did you find your voice had nary tone.

But there's none like you can sing

"To Anthea," "The Erl-King."

SCHUBERT, GOUNOD, English HATTON,

Equally your Fine Art's pat on.

Punch can never praise you scantly.

À votre santé, good CHARLES SANTLEY!

[At the Anti-Gambling Demonstration recently held in Exeter Hall, Sir RICHARD WEBSTER, the Attorney-General, said that it was supposed by many that it was impossible to enjoy athletic pursuits without becoming interested in a pecuniary sense. He should therefore like to add, not for the purpose of holding himself up as an example, that, during his entire interest in sports of all kinds, he had never made a bet.]

Ah! these are days when Recklessness, bereft of ready cash,

Will strive to remedy the void by speculative splash;

It is a salutary sight for Bankruptcy and Debt—

Our good Attorney-General who never made a bet.

His interest in manly sports, an interest immense,

Was ne'er degraded to a mere "pecuniary sense;"

His boyhood's love of marbles leaves him nothing to regret—

Our good Attorney-General who never made a bet.

Next, when a youth, the cricket-bat he first began to wield,

And "Heads or Tails?" re-echoed for the Innings through the field.

He sternly scorned to toss the coin, howe'er his friends might fret—

Our good Attorney-General who never made a bet.

And when, an Undergraduate, he swiftly skimmed his mile,

And comrades staked with confidence on him their little pile,

He'd beg them not on his account in gambling ways to get—

This good Attorney-General who never made a bet.

To play for money ruins whist: and seldom can his Club

Persuade him to put counters (coins for Zulus!) on the rub;

He has been known for lozenges to dabble with piquet;

He wasn't Chief Attorney then, nor was it quite a bet.

His wise profession's ornament, he looks on all such games

Far otherwise than RUSSELL does, than LOCKWOOD, HALL, or JAMES;

For pure platonic love of play he stands, unequalled yet—

Our good Attorney-General who never made a bet.

St. Stephen's, too, thinks much of him; but ah! his soul it pains

To know that Speculation o'er the lobby sometimes reigns;

He's chided OLD MORALITY and RANDOLPH and the set,

Beseeching them on bended knees to never make a bet.

We all are fond of him, in short, the Boxes with the Gods;

That he's a first-rate fellow we would gladly lay the odds.

But no!—himself would veto that. We must not wound our pet

Precise Attorney-General who never made a bet.

All have heard of "a Manuscript found in a Bottle,"

But here is a waif with romance yet more fraught:

A newly-found treatise by old ARISTOTLE

Is flotsam indeed from the Ocean of Thought.

Oh, happy discoverer, lucky Museum!

Not this time the foreigner scores off JOHN BULL.

Teuton pundits would lift, for such luck, their Te Deum!

No SHAPIRA, Punch hopes, such a triumph to dull!

May it all turn out right! Further details won't tire us.

We may get some straight-tips from that Coptic papyrus!

Well, I begins to agree with them as says, and says it too as if they ment it, that noboddy can reelly tell what is reel grand injiyment till they trys it, and trys it farely, and gives it a good chance. I remembers how I used to try and like Crikkit, when I was much yunger than I am now, and stuck to it in spite of several black eyes when I stood pint, and shouts of, "Now then, Butter-Fingers!" when I stood leg, till a serten werry fast Bowler sent me away from the wicket with two black and blew legs, and then I guv it up. I guv up Foot Ball for simler reesuns, and have never attemted not nothink in the Hathlettick line ewer since, my sumwat rapid increase in size and wait a hading me in that wise resolooshun.

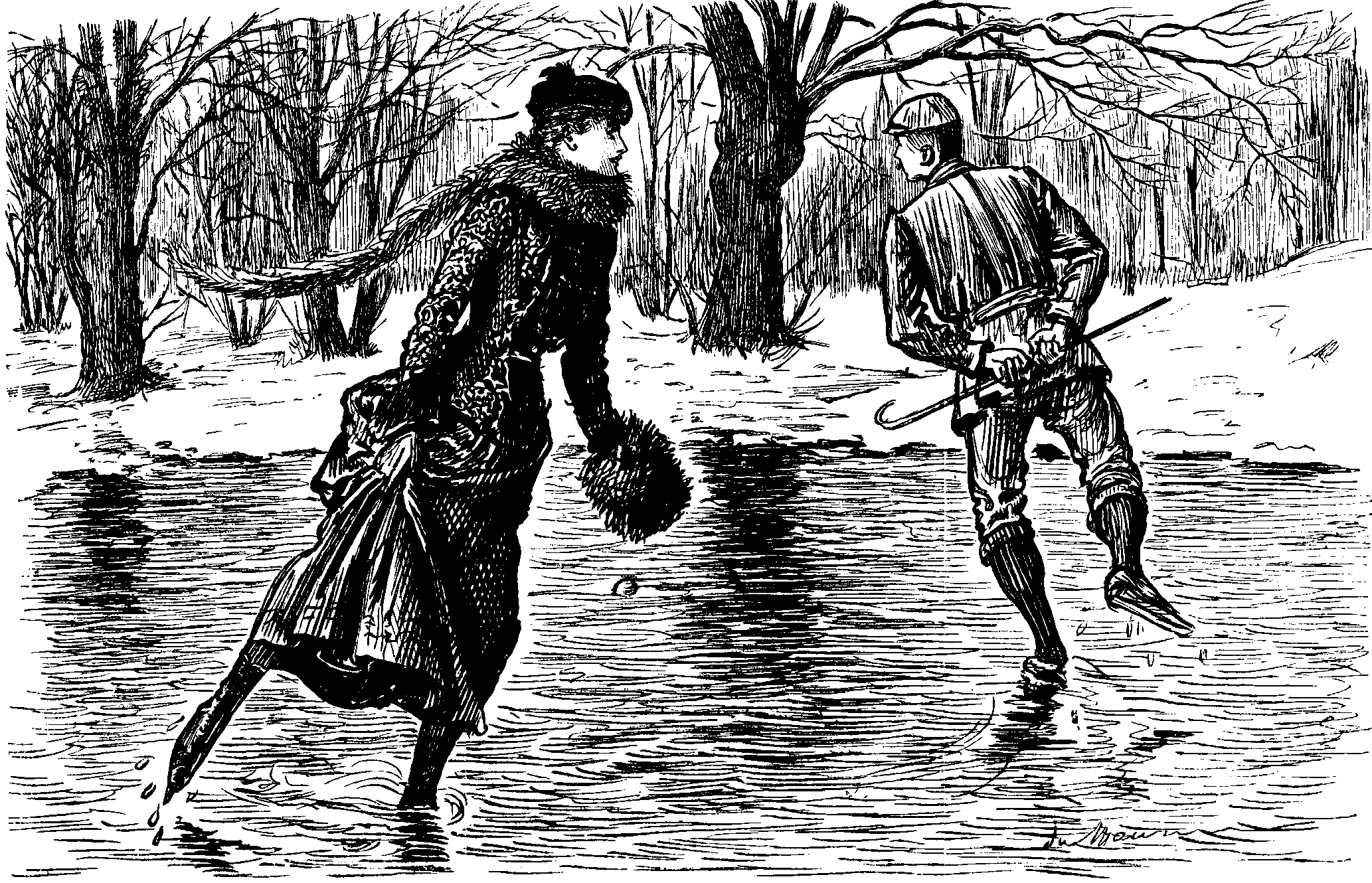

But sumhow it appened, dooring the hawful whether we has all bin a shivering threw for this long time, that I found my atenshun direckted to the strange fack that, whilst amost ewerybody was busily engaged in a cussin and swarin at the bitter cold and the dirty slippery sno, ewerybody else seemed to be injying of theirselves like wun-a-clock. Now it so appened that when waiting one day upon the young swell I have before spoken of, at the "Grand 'Otel," he was jined by another swell, who told him what a glorius day's skating he had been avin in Hide Park! and how he ment to go agen to-morrer, "if the luvly frost wood but continue!"

So my cureosety was naterally egsited, and nex day off I gos to Hide Park, and there I seed the xplanation of what had serprised me so much. For there was hunderds and hunderds of not only spectably drest Gents, but also of reel-looking Ladys, a skatin away like fun, and a larfing away and injying theirselves jest as if it had bin a nice Summer's day. Presently I append to find myself a standing jest by a nice respectabel looking man, with a nice, cumferal-looking chair, and seweral pares of Skates; and presently he says to me, quite permiscus-like, "They all seems to be a injying theirselves, don't they, Sir?" which they most suttenly did; and then he says to me, says he, "Do you skate, Sir?" to which my natral pride made me reply, "Not much!" "Will you have a pair on. Sir," says he, "jest for a trial?" "Is there any fear of a axident?" says I. "Oh no. Sir," says he, "not if you follers my hinstrucshuns." So I acshally sets myself down in his chair, and lets him put me on a pair of Skates! The first differculty was, how to get up, which I found as I coudn't manage at all without his asistance; for, strange to say, both of my feet insisted on going quite contrary ways. Howewer, by grarsping on him quite tite round his waste, I at last manidged to go along three or four slides, and then I returned to the chair, and sat down again; and he was kind enuff to compliment me, and to say that he thort I was a gitting on fust-rate, and, if I woud only cum ewery day for about a week or so, he had no dowt but he shood see me a skating a figger of hate like the best on 'em!

Hencouraged by his truthfool remarks, I at larst wentured to let go of him and try a few slides by myself, and shood no dowt have suckseeded hadmerably, but my bootifal stick to which I was a trustin to elp me from falling, slided rite away from me in a most unnatral manner, and down I came on my onerabel seat, with such a smasher as seemed to shake all my foreteen stun into a cocked-hat, to speak, hallegorically, and there I lay, elpless and opeless, and wundring how on airth I shood ever get up again. But my trusty frend and guide was soon at my side, as the Poet says, but all his united force, with that of too boys who came to his assistance, and larfed all the wile, as rude boys will, coud not get me on my feet agen 'till my too skates was taken off, and I agen found myself on terror fermer on my friend's chair. It took me longer to recover myself than I shood have thort posserbel, but at larst I was enabled to crawl away, but not 'till my frend had supplied me with jest a nice nip of brandy, which he said he kept andy in case of any such surprisin axidents as had appened to me.

So what with paying for the use of the skates, and the use of the Brandy, and the use of the too boys, and the use of a handsum Cab to take me to the "Grand," that was rayther a deer ten minutes skating, and as it was reelly and trewly my fust attemt at that poplar and xciting passtime, I think I may safely affirm—as I have alreddy done to my better harf—whose langwidge, when I related my hadwentur, is scarcely worth repeating, as it was most certenly not complementary—that it shall be my larst. ROBERT.

They tell me thou art cold, my sweet—

A fact that scarcely odd is.

Gales half so cruel never beat

Against poor human bodies.

Cupid's attire is far too light

To weather Thirty Fahrenheit.

How can a glow the soul entrance,

When frostbite nips the finger,

And blushes quit the countenance

To nigh the nostril linger!

Warmth were a miracle, in sight

And grip of Thirty Fahrenheit.

Chill! chill to me, my Paradise!!

I'll not complain or curse on.

One cannot well be otherwise

To any mortal person.

Mere icebergs ambulant, we fight

Ferocious Thirty Fahrenheit.

Cold art thou? Not so cold as I—

Nought living could be colder.

I'm far too cold to sob or sigh,

Still less in passion smoulder.

I'm turning fast to something quite

As numb as Thirty Fahrenheit.

INFORMATION REQUIRED.—"Sir, I see a Volume advertised entitled, Unspoken Sermons. I should be glad to know where these are preached, as that's the place for yours truly, ONE WHO SNORES."

NEW BOOK OF IRISH LIFE.—The Bedad's Sons. By the Author of the tale of Indian Life, The Begum's Daughters.

House of Commons, Thursday, January 22.—Both Houses met to-day after Christmas Recess. No QUEEN's Speech; no moving and seconding of Address; no Royal Commission and procession of SPEAKER to Lords. All seems strange, and spirits generally a little depressed. Only ROBERT FOWLER rises superior to circumstances of hour. Blustering about the Lobby "like Boreas," says CAUSTON.

"Only not so rude," says HARRY LAWSON, jealous for the reputation of Metropolitan Members, even though some sit on the Benches opposite. With folded hands thrust behind coat-tails, rollicking stride, thunderous voice, and blooming countenance, Sir ROBERT positively pervades the Lobby. Personally receives POPE HENNESSY; shakes hands with everybody; and finally halting for a moment under the electric-lit archway leading into House, presents interesting and attractive picture of the Glorified Alderman.

Scotch Members take possession of Commons to-night. LORD ADVOCATE brings in Bill, providing new machinery for private legislation; the Scotch Members with one accord fall upon proposal, and tear it to ribbons. Meanwhile other Members troop off to Lords, where spectacle is provided which beats the pantomimes into fits. Two new Peers to take their seats; procession formed in back room outside; enters from below Bar. First comes Black Rod, with nothing black about him; then Garter King-at-Arms, a herculean personage, fully five feet high, with a dangerous gleam in his eye, and the Royal Arms of England quartered in scarlet and blue and gold on his manly back. Behind, in red cloaks slashed with ermine, the new Baron and his escort of two brother Peers. There being no room for them to advance in due procession, they fall into single file, make their way to the Woolsack, where sits that pink of chivalry, that mould of fashion, that perfection of form, the LORD HIGH CHANCELLOR.

New Peer drops on one knee, presents bundle of paper to LORD CHANCELLOR. L.C., coyly turning his head on one side, gingerly takes roll, hands it to Attendant. New Peer gets up; procession bundles back to table; here Gentleman in wig and gown gabbles something from long document. New Peer writes his name in a book (probably promising subscription towards expenses of performance.) Garter King-at-Arms getting to the front trots off with comically short strides for so great a dignity; New Peer and escort follow, Black Rod solemnly bringing up rear. Garter King makes for Cross Benches by the door; passes along one, the rest following, as if playing game of Follow-my-leader. Garter King suddenly making off to the right, walks up Gangway to row of empty Benches. Stops at the topmost row but one, and passes along. New Peer wants to follow him. Garter King prods him in chest with small stick, and tells him to go on to the Bench above. This he does, with escort. Meanwhile, Black Rod left out in the cold. Garter King motions to three Peers to be seated; tells them to put on their cocked-hats; counts ten; nods to them; they rise to feet, uplift cocked-hats in direction of LORD CHANCELLOR on Woolsack. He raises his in return of salute. Three Peers sit down again. Garter King counts ten; nods; up they get again, salute LORD CHANCELLOR; sit down once more. "One—two—three—four—ten," Garter King mumbles to himself. Once more they rise; salute LORD CHANCELLOR; then Garter King leading the way, they march back to Woolsack.

Garter King now introduces new Member to LORD CHANCELLOR. L.C. starts as if he had never seen him before; then extends right [pg 60] hand; New Peer shakes it, procession reformed, walks out behind Bar. A few minutes later, another comes in, all the business done over again. Impressive, but a little monotonous, and as soon as possible after its conclusion Noble Lords go home.

Business done.—In Commons, Private Bill Legislation Bill read a Second Time.

Friday.—WM. O'BRIEN, standing with tear-stained face on pier at Boulogne waving wet handkerchief across the main, has drawn away JUSTIN McCARTHY, who can't be back till Monday. PARNELL was to have come down to-day, and, making believe to be still Leader of United Irishmen, asked OLD MORALITY to set aside day for discussion of his Motion on operation of Crimes Act. BRER FOX accordingly looked in shortly after SPEAKER took the Chair.

"Seen BRER RABBIT anywhere about, TOBY?" he asked.

So I up and told him about McCARTHY's new journey to Boulogne.

"Oh, indeed," said BRER FOX; "if that's the case, I think I won't trouble House to-night. Got an engagement elsewhere; think I'll go and keep it. Not used to hanging about here, as you know; awful bore to me; but as long as BRER RABBIT comes here, I must be on spot to vindicate my position. So I'll say ta-ta. No—never mind ringing for fire-escape; can walk down the steps to-day."

Thus there being no Irish Leader on the premises, and hardly any Irish Members, had a rare chance for attending to British business. CHANNING brought on question of working Overtime on the Railways; moved Resolution invoking interference of Board of Trade. Question a little awkward for Government. Couldn't afford to offend Railway Directors, yet wouldn't do to flout numerous body of working-men, chiefly voters. Proposed to shelve business by appointment of Select Committee. Opposition not going to let them off so easily. Debate kept up all night, winding up with critical Division; Government majority only 17.

"And this," said OLD MORALITY, with injured look, "after PLUNKET's brilliant oration on the time-tables of the London and North-Western Railway Company! If he'd only illustrated it with magic-lantern, things would have gone differently." But he was obstinate; said there would be difficulty in arranging the slides, and so rejected proposal.

Business done.—CHANNING's Resolution about Overtime on Railways negatived by 141 Votes against 124.

Sir,—As the recognised organ of the legal profession, will you permit me to address you? It is common knowledge that within the last few days the Right Honourable Sir JAMES HANNEN has been raised to a dignity greater than that he has been able to claim for the last eighteen years, when he has sat as President of the Probate, Divorce, and Admiralty Division of the High Court of Justice. On leaving the Court in which so many of us were known to him, he was kind enough to say, "Those eighteen years had been eighteen years of happiness to him, chiefly arising from the advantage he had had in having before him habitually practising in that Court Barristers who had felt that their part was just as important as his in the administration of Justice, and who had assisted him enormously. Without their assistance, his task would have been an arduous one, whereas it had been, as he had said, an agreeable one." As I personally have had the honour of appearing before his Lordship for many years, I think that it is only right that I should make some acknowledgment of this kind recognition of my services.

It is quite true that I have felt, as Sir JAMES HANNEN suggests, that my part (humble as it may have been) has been just as important as his in the administration of Justice. But it is gratifying to me beyond measure to learn that my invariable custom of bowing to his Lordship on the commencement and conclusion of each day's forensic duties—which has been the limit of my "habitual practice" in the Probate Division—should "have assisted him enormously." I can only say that, thanks to his unvarying kindness and courtesy, my daily recognition of his greetings from the Bench, instead of being an arduous task, has ever been an agreeable one. I have the honour to remain, Sir, your very obedient servant,

(Signed)

A. BRIEFLESS, JUNIOR.

Pump-Handle Court, January 24, 1891.

"PRO-DIGIOUS!"—In last Sunday's Observer we read that at St. Petersburg Madame MELBA, as Juliette, "was recalled thirty-one times before the proscenium." The italics are ours, rather! If this sort of thing is to be repeated during the Opera season here, and each gifted singer is recalled in proportion to his or her merits, the audience will not get away till the following morning. Juliette must have said, on the above-mentioned occasion, "Parting is such sweet sorrow, That I could say 'good-night' until to-morrow." And the usual chorus of operatic habitués will be, "We won't go home till morning. Till daylight doth appear!" with refrain, "For—she (or he)'s a jolly good singer," &c., ad infinitum, or "ad infi-next-nightum."

O Queen of Cities, with a crown of woe,

Scarred by the ruin of two thousand years,

By fraud and by barbarian force laid low,

Buried in dust, and watered with the tears

Of unregarded bondmen, toiling on,

Crushed in the shadow of their Parthenon;

Mother of heroes, Athens, nought availed

The Macedonian's triumph, or the chain

Of Rome; the conquering Osmanli failed,

His myriad hosts have trampled thee in vain.

They for thy deathless body raised the pyre,

And held the torch, but Heaven forbade the fire.

Then didst thou rise, and, shattering thy bands,

Burst in war's thunder on the Muslim horde,

Who shrank appalled before thee, while thy hands

Wielded again the imperishable sword,

The sword that smote the Persian when he came,

Countless as sand, thy virgin might to tame.

Mother of freemen, Athens, thou art free,

Free as the spirits of thy mighty dead;

And Freedom's northern daughter calls to thee,

"How shall I help thee, sister? Raise thy head,

O Athens, say what can I give thee now,

I who am free, to deck thy marble brow?"

Shot-dinted, but defiant of decay,

Stand my gaunt columns in a tragic line,

The shattered relics of a glorious day,

Mute guardians of the lost Athena's shrine.

The flame of hope, that faded to despair

Ere Hellas burst her chains, is imaged there.

Yet one there was who came to her for gain,

Ere yet the years of her despair were run;

And with harsh zeal defaced the ruined fane

Full in the blazing light of Hellas' sun.

Spoiling my home with sacrilegious hand,

He bore his captives to a foreign land.

Ilissus mourns his tutelary god,

Theseus in some far city doth recline:

Lost is the Horse of Night that erstwhile trod

My hall; the god-like shapes that once were mine

Call to me, "Mother save us ere we die,

Far from thy arms beneath a sunless sky."

How shall I answer? for my arms are fain

To clasp them fast upon the rock-bound steep,

Their ancient home. Shall Athens yearn in vain,

And all in vain must woful Hellas weep?

Must the indignant shade of PHIDIAS mourn

For his dear city, free but how forlorn?

How shall I answer? Nay, I turn to thee,

England, and pray thee, from thy northern throne

Step down and hearken, give them back to me,

O generous sister, give me back mine own.

Thy jewelled forehead needs no alien gem

Torn from a hapless sister's diadem.

NOTICE.—Rejected Communications or Contributions, whether MS., Printed Matter, Drawings, or Pictures of any description, will in no case be returned, not even when accompanied by a Stamped and Addressed Envelope, Cover, or Wrapper. To this rule there will be no exception.