A light canoe, a box of cigarettes,

Sunshine and shade;

A conscience free from love or money debts

To man or maid;

A book of verses, tender, quaint, or gay,

DOBSON or LANG;

Trim yew-girt gardens, echoing the day

When HERRICK sang;

A Thames-side Inn, a salad, and some fruit,

Beaune or Hochheimer;—

Are simple joys, but admirably suit

An idle rhymer.

Saturday, June 6, 11 P.M.—Home after our last turn. Fancy from several drinks had on the way, and the pace we had to put into that last mile and a half, that something's up. Turned into stall nice and comfortable, as usual.

Sunday.—Something is up with a vengeance. Hoorooh! We're on strike. I don't know the rights of it, nor don't care, as long as I have my bit of straw to roll in, and a good feed twice a day. I wonder, by the way, if the fellow who looks after my oats is "off." Past feeding time. Feel uneasy about it. Hang it all, I would rather work for my living, than be tied up here doing nothing without a feed! Ha! here he is, thank goodness, at last. However, better late than never. Capital fun this strike.

Monday.—Am sent out in a loyal omnibus. Hooted at and frightened with brickbats. Felt half inclined to shy. Halloa! what's this? Hit on the ribs with a paving-stone. Come, I won't stand this. Kick and back the 'bus on to the pavement. All the windows smashed by Company's men. Passengers get out. Somebody cuts the traces, and I allow myself to be led back to the stables. Don't care about this sort of fun. However, feed all right.

Tuesday.—Hear that the men want thirteen and sixpence a day and a seven hours' turn. Directors offer five and sixpence, and make the minimum seventeen hours. Go it, my hearties! Fight away! Who cares? You must feed me, that's quite certain. Still I don't care about being cooped up here all day. Nasty feeling of puffiness about the knees. Hang the strike!

Wednesday.—Puffiness worse. Vet. looks in and says I want exercise. Take a bolus and am walked for half an hour or so up and down some back-streets. Bless them!—that ain't no good.

Thursday.—Puffiness worse, of course. Bother it all, being shut up here! What wouldn't I give just for a sight of dear old Piccadilly! The fact is, if they don't soon let me have my run from King's Cross to Putney, I shall "bust up"—and that's a fact. I feel it.

Friday.—Ah, they may well come to terms! Another day of this, and I believe I should have been off the hooks "for ever and for aye." It's all very well for Capital and Labour to get at loggerheads, but, as DUCROW said, they must cut all their disputes short if they wish to save anything of their business, and look sharp, and "come to the 'osses."

Saturday, 13th.—Strike over! We shall have to be in harness again on Monday, and not a day too soon, in the interests of the men, the Directors, the Public; and, last, but by no means least, specially that of "the 'osses."

Punch sympathises with Canadian sorrow

For him known lovingly as "OLD TOMORROW."

Hail to "the Chieftain!" He lies mute to-day,

But Fame still speaks for him, and shall for aye.

"To-morrow—and to-morrow!" SHAKSPEARE sighs.

So runs the round of time! Man lives and dies.

But death comes not with mere surcease of breath

To such as him. "The road to dusty death"

Not "all his yesterdays." have lighted. Nay!

Canada's "OLD TO-MORROW" lives to-day

In unforgetting hearts, and nothing fears

The long to-morrow of the coming years.

Billsbury, Wednesday, May 28th.—Great doings here to-day. For weeks past all the Conservative Ladies of Billsbury have been hard at work, knitting, sewing, painting, embroidering, patching, quilting, crocheting, and Heaven knows what besides, for the Bazaar in aid of the Conservative Young Men's Club and Coffee-Room Sustentation Fund. You couldn't call at any house in Billsbury without being nearly smothered in heaps of fancy-work of every kind. When I was at the PENFOLDS' on Monday afternoon, the drawing-room was simply littered with bonnets and hats, none of them much larger than a crown piece, which Miss PENFOLD had been constructing. She tried several of them on, in order to get my opinion as to their merits. She looked very pretty in one of them, a cunning arrangement of forget-me-nots and tiny scraps of pink ribbon. Mother promised some time ago to open the Bazaar, though she assured me she had never done such a thing before, and added that I must be sure to see that the doors moved easily, as new doors were so apt to stick, and she didn't know what she should do if she had to struggle over the opening. I comforted her by telling her she would only have to say a few brief words on a platform, declaring the Bazaar open. For the last week I have had a letter from her by absolutely every post, sending draft speeches for my approval. After much consideration I selected one of these, which I returned to her. I heard from home that she was very busily occupied for some time in learning it by heart. When cook came for orders in the morning, she was forced to listen while Mother said over the speech to her. Cook was good enough to express a high opinion of its beauties.

Yesterday evening Mother arrived, with the usual enormous amount of luggage, including the inevitable Carlo. After dinner I heard her repeat the speech, which went off very well. This is it:—"Ladies and Gentlemen, I am so pleased to be here to-day, and to have the opportunity of helping the dear Conservative cause in Billsbury. I am sure you are all so anxious to buy as many of these lovely things as you can, and I therefore lose no time in declaring the Bazaar open." Simple, but efficient.

The opening to-day was fixed for 2:30, the Bazaar being held in the large room of the Assembly Rooms, which had been arranged to represent an Old English Village. At one o'clock Colonel and Mrs. CHORKLE, Alderman and Mrs. TOLLAND, and one or two others, lunched with us, and afterwards we all drove off together in a procession of carriages. I insisted on Carlo being left behind, locked up in Mother's bed-room, with a dish of bones to comfort him, and an old dress of Mother's to lie on. That old dress has been devoted to Carlo for the last two years, and no amount of persuasion will induce Carlo to take another instead. We tried him with a much better one a short time ago, but he was furious, tore it to ribbons and refused his food until his old disreputable dress had been restored to him.

The Bazaar proceedings began with a short prayer delivered by the Bishop of BRITISH GUIANA, an old Billsbury Grammar-School boy, who was appointed to the bishopric a month ago. Everybody is making a tremendous fuss about him here of course. As soon as the prayer was over, Colonel CHORKLE rose and made what he would call one of his "'appiest hefforts." The influence of lovely woman, Conservative principles, devotion to the Throne, the interests of the Conservative Young Men's Sustentation Fund, all mixed up together like a hasty pudding. Then came the moment for Mother. First, however, WILLIAMINA HENRIETTA SMITH CHORKLE had to be removed outside for causing a disturbance. Her father's speech so deeply affected this intelligent infant, who had come under the protection of her nurse, that she burst out into a loud yell and refused to be comforted. The Colonel's face was a study—a mixture of drum-head Courts-martial and Gatling guns. Mother got through with her little speech all right. As a matter of fact she read it straight off a sheet of paper, having finally decided that her memory was too treacherous. We both set to work and bought an incredible amount of things. After half an hour I found myself in possession of six bonnets made by Miss PENFOLD, three knitted waistcoats, four hand-painted screens, two tea-tables also hand-painted, a lady's work-basket, three fancy shawls, a set of glass studs and a double perambulator, which I won in a raffle. Mother got three dog-collars, a set of shaving materials (won in a raffle), two writing cases, five fans, two pictures by a local artist, four paper-knives, two carved cigar-boxes, a set of tea things, and five worked table-covers.

When we got back, we found that Carlo had nearly gnawed his way through the bed-room door, and was growling horribly at the boots and the chambermaid through the keyhole. Charming dog!

Professor GARNERS, in the New Review

Tells us that "Apes can talk." That's nothing new;

Reading much "Simian" literary rot,

One only wishes that our "Apes" could not!

"CAN'T SEE YOU NOW, I'M WASHING—MYSELF."

"CAN'T SEE YOU NOW, I'M WASHING—MYSELF."

"The Women are crying out for the protection of the Factory Acts, which has hitherto been denied them, and which the Home Secretary declines to pledge the Government to support."—Daily Telegraph, Friday, June 12th.

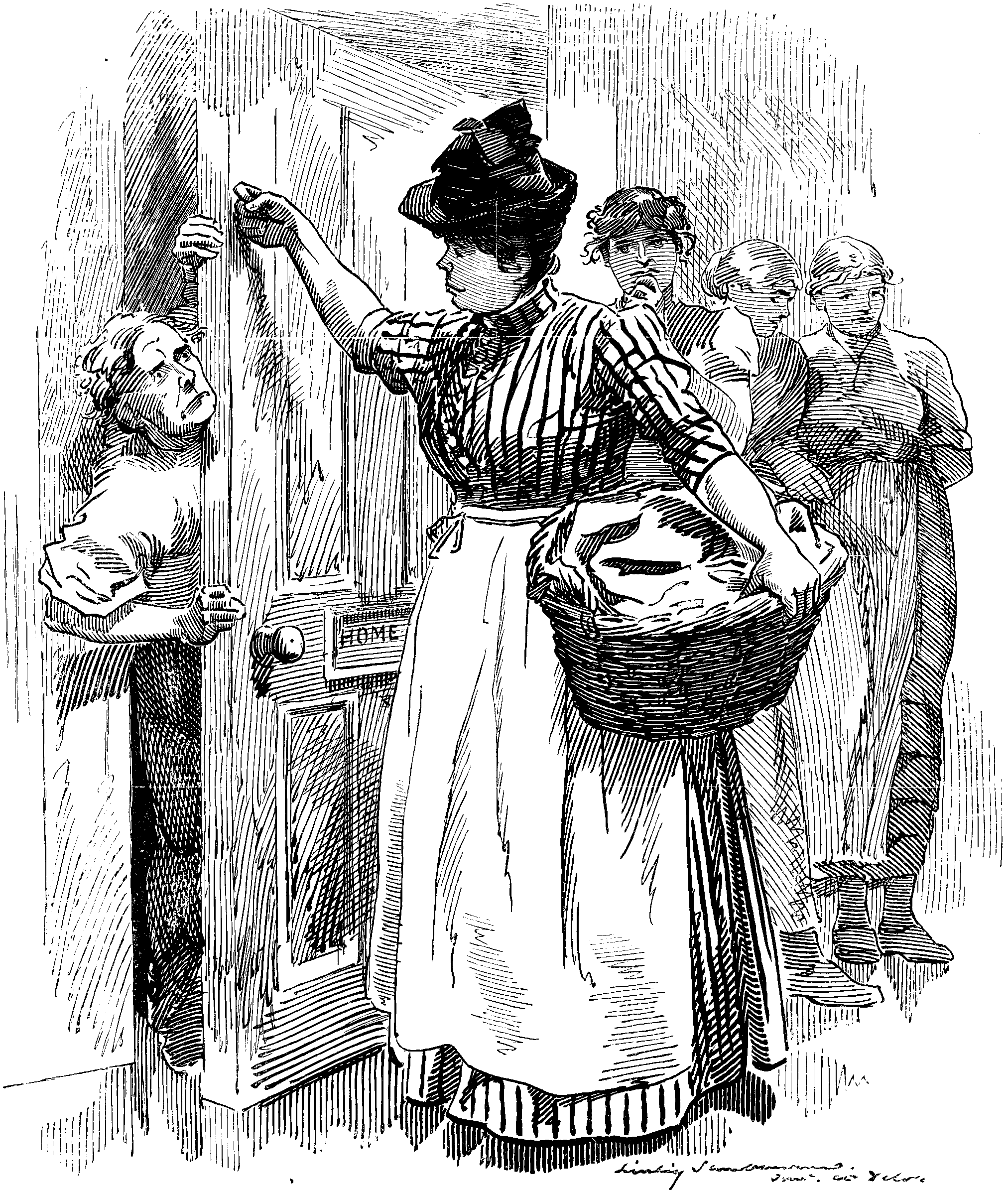

London Laundry-woman, to her Tub-mate, loquitur:—

They tell us the Tub is humanity's friend, and that Cleanliness is of closest kin

To all things good. By the newest gospel 'tis held that Dirt is the friend of Sin.

Well, I'm not so sure that the world's far wrong in that Worship of Washing that's all the rage;

But we, its priestesses, sure might claim a cleanly life and a decent wage!

[pg 291]Listen, BET, from your comfortless seat on the turned-up pail,—if you've got the time;

Isn't it queer that Society's cleansers must pass their lives amidst muck and grime?

Spotless flannels no doubt are nice—and snowy linen is "swell" and sweet,

But steaming reek is around our heads, and trickling foulness about our feet.

If the dainty ladies whose linen we lave, we laundress drudges, could look in here,

Wouldn't their feet shrink back with sickness, and wouldn't their faces go pale with fear?

White, well-ironed, all sheen and sweetness, that linen looks when it leaves our hands;

But they little think of the sodden squalor that marks the den where the laundress stands.

Scrub, scrub, scrub, at the reeking tub, for eighteen hours at a stretch, perchance,

Till our bowed backs ache, and our knuckles smart, and the lights through the steam like spectres dance;

Ankle-deep in the watery sludge, where the tile is loose or the drainage blocked!

Oh, I haven't a doubt that the dainty dames—if they only knew!—would be sorely shocked.

Typhoid! Terribly menacing word, the whisper of which would destroy our trade;

But dirt, and damp, and defective drainage will raise that ghost on a world afraid;

And at thirty years our strength is sapped by insidious siege of the stifling fume,

Or what if we linger a little longer? Scant rays of comfort such life illume.

Grievances, BET? Well, I make no doubt that the world of idlers is sorely sick

Of the moans and groans of the likes of us. When the whip, the needle, the spade, the pick,

Are all on strike for a higher wage, 'tis a worry, of course, to the well-to-do,

And a sleek Home-Sec, must "decline to pledge" support official to me and you.

Of course, of course! Who are we, my dear, to bother the big-wigs and stir their bile?

Why, it's all along of our "discontent," and the Agitator's insidious guile.

But Labour, BET, is agog just now to revise the old one-sided pacts,

And even a Laundress may have an eye to the benefit of the Factory Acts.

Those bad, bad 'Busmen, BET my girl, claim shorter hours, and a longer pay;

Just think of such for the Slaves of the Tub! Why should we women not have our say

In the Park o' Sunday, like DAN the Docker, or TOM the Tailor, or WILL the "Whip"?

The Tub and the Ironing-board appear to have got a chance—which they mustn't let slip:

An Object Lesson in Laundress Labour, may move the callous and shame the quiz.

We dream of "Washing as well it might be"; we'll show them "Washing as now it is."

We know it, BET, in the sodden wet and the choking fume; with the aching back,

The long, long hours, and the typhoid taint, the inverted pail and the hurried snack.

There may—who knows?—be hope for us yet, for you and me, BET! Just think o' that!

Oh, I know it is hard to believe it, my girl. The Sweater's strong, and appeal falls flat

On official ears; and fine-lady fears, and household hurry against us go;

But "evil is wrought by want of thought." says some poet, I think;—so we'll let them know!

Ah! snowy sheets and sweet lavender scent of the dear old days in my village home!

The breadths of linen a-bleach on the grass! How little I thought that to this I'd come

Grand ladies of old to their laundry looked, and the tubs were white, and the presses fair;

Now we cleansers clean in the midst of dirt, in a dank, dark den, with a noisome air.

Sometimes I dream till the clouds of steam take the shadowy form of a spectral thing,

A tyrant terror that threatens our lives, whilst we rub and scrub, whilst we rinse and wring.

Well, cheer up, BET, girl, stiffen your lip, and straighten your back. You have finished your grub,

So to work once more; if our champions score, we may find a new end to this Tale of a Tub!

Sunday.—Can scarcely believe the news! What, no omnibuses! A strike! What shall we do? Fortunately always go to church on foot, so no loss in that. Then subsequent parade in the Park—don't require an omnibus for that, either. At the end of the day, can say that, take one thing with another, state of affairs more comfortable than might have been anticipated.

Monday.—Dreaded continuance of strike, but found, practically, little inconvenience. Had to walk to the office, and enjoyed the promenade immensely. Had no idea that a stroll along the Embankment was so delightful. After all, one can exist without omnibuses—at least, for a time.

Tuesday.—Find that people who were at their wits' end at the mere suggestion of a strike, are becoming reconciled to the situation. Streets certainly pleasanter without the omnibuses. Great, lumbering conveyances, filling up the road, and stopping the traffic! London looks twice as well without them! Tradesmen, too, say that the shops are just as well attended now as when the two great Companies were in full swing.

Wednesday.—Can't see what the omnibus people (both sides—Directors and employés) are quarrelling about. No matter of mine, and the Public are only too glad for a chance of a good walk. Fifty per cent. better since I have been obliged to give up the morning 'bus. Asked to-day to contribute something in support of the strikers. Certainly not, the longer the strike lasts the worse for the Public.

Thursday.—Really the present state of affairs is delightful. I have to thank the deadlock for teaching me to patronise the river steamboats. Pleasant journey from Vauxhall to the Temple for a penny! No idea that the Thames was so pretty at Westminster. View of the Houses of Parliament and the Embankment capital.

Friday.—Strike continues. Well I do not complain. Hired a hansom and find that considering the cab takes you up to door, it is really cheaper in the long run. If you use an omnibus, you get jolted, and run a chance of smashing your hat. If it rains you get splashed and having to finish your journey on foot, you might just as well have walked the whole way.

Saturday.—Strike arranged to cease on Monday! This is too much! Just as we were getting comfortable, all the disgusting lumbering old omnibuses are to come back again! It ought not to be allowed. Asked to-day to contribute something in support of the strikers. Certainly, the longer the strike lasts the better for the Public.

First Slender Invalid. "I SAY, OLD MAN, WHAT A BEASTLY THING THIS INFLUENZA IS, EH? I'M JUST GETTING OVER IT."

His Wasting Friend. "AH! YOU'RE RIGHT, MY BOY! I'VE HAD IT TOO, AND THE WORST OF IT IS, IT PULLS A FELLOW DOWN SO FEARFULLY!!"

1891. The Leader of the House explains, in answer to a question, that no understanding exists between England and any Foreign country. No treaty is in contemplation, and never has been suggested on either side.

1892. The Government repeats that England is absolutely free from any international engagements. It must not be thought for a moment that a single battalion will be moved, or a solitary vessel dispatched abroad with warlike intentions.

1893. The Representative of the Cabinet once more denies the suggestion that, under any consideration whatever, will England bind herself to accept European responsibility. This has been said constantly for the last three years, and the Representative of the Cabinet is not only surprised but pained at these frequent and embarrassing interrogations.

1894. Once more, and for the last time, the PREMIER insists that whatever may happen abroad, England will be free from interference. It has been the policy of this great country for the last four years to steer clear of all embarrassing international complications. The other Great Powers are perfectly aware that, under no circumstances whatever, will our Army and Fleet be employed in taking part in the quarrels of our neighbours. The entire Cabinet are grieved at questions so frequently put to them—questions that are not only disquieting abroad, but a slur upon the intentions of men whose sole duty is the safety and peace of the British Empire.

1895. General European War—England in the midst of it!

SCENE—The Grounds. A string of Sightseers discovered passing slowly in front of a row of glazed cases containing small mechanical figures, which are set in motion in the usual manner.

A Gallant Swain. That's the kid in bed, yer see. Like to see it die, POLLY, eh? A penny does it.

Polly (with a giggle). Well, if it ain't too 'arrowing. (The penny is dropped in, and the mechanical mother is instantly agitated by the deepest maternal anxiety.) That's the mother kneeling by the bed, I suppose—she do pray natural. There's the child waking up—see, it's moving its 'ed. (The little doll raises itself in bed, and then falls back lifeless.) Ah, it's gone—look at the poor mother 'idin' her face.

The G.S. Well, it's all over. Come along and see something more cheerful.

Polly. Wait a bit—it isn't 'alf over yet. There's a angel got to come and carry her away fust—there, the door's opening, that'll be the angel come for it, I expect. (Disappointed.) No, it's only the doctor. (A jerky and obviously incompetent little medical practitioner puts his head in at the door, and on being motioned back by the bereaved mother, retires with more delicacy than might have been expected.) Well, he might ha' seen for himself if the child was dead! (The back of the bed disappears, disclosing a well-known picture of an angel flying upwards with a child.) I did think they'd have a real angel, and not only a picture of one, and anyone can see it's a different child—there's the child in bed just the same. I call that a take-in!

The G.S. I dunno what more you expect for a penny.

A Person on the Outskirts (eagerly to Friend). What happened? What is it? I couldn't make it out over all the people's shoulders.

His Friend. Dying child—not half bad either. You go and put in a penny, and you'll see it well enough.

The P. on the O. (indignantly). What, put in a penny for such rubbish? Not me!

[He hangs about till someone else provides the necessary coin.

A Softhearted Female. No, I couldn't stand there and look on. I never can bear them pathetic subjects. I felt just the same with that picture of the Sick Child at the Academy, you know. (Meditatively.) And you don't have to put a penny in for that, either.

First Woman. That's 'im in bed, with the bottle in his 'and. He likes to take his liquor comfortable, he do.

Second Woman. He's very neat and tidy, considering ain't he? I wonder what his delirium is like. 'Ere, ROSY, come and put your penny in as the gentleman give yer. (ROSY, aged six, sacrifices her penny, under protest.) Now, you look—you can't think what pretty things you'll see.

[The little wooden drunkard sits up, applies the bottle to his mouth, and sinks back contentedly; a demon, painted a pleasing blue, rises slowly by his bed-side: the drunkard takes a languid interest in him; the demon sinks.

A Gentleman with a bloated complexion (critically). 'Ooever did that—well, I dessay he's a very clever man, but—(compassionately)—he don't know much about 'orrors, he don't!

A Facetious Friend. You could ha' told him a thing or two, eh, JIM?

The Bloated Gentleman (contemptuously). Well, if I never 'ad them wuss than that!

[A small skeleton, in a shroud, looks in at the door.

The F.F. 'Ullo, 'ere's the King o' Terrors for yer! (ROSY shows signs of uneasiness; a blue demon comes out of a cupboard.) 'Ere's another of 'em—quite a little party he's 'aving!

A Gentleman, in a white tie (as the machinery stops). Well, a thing like this does more real good than many a temperance tract.

The Bloated G. Yer right there, Guv'nor—it's bin a lesson to me, I know that. 'Ere, will you come and 'ave a whiskey-sour along of me and my friend 'ere'?

A Daughter. But why won't you 'put a penny into this one, Father?

The Father (firmly). Because I don't approve of Capital Punishment, my dear.

A Cultivated Person. An execution—"put a penny in; bell tolls—gates open—scaffold shown with gallows. Executioner pulls bolt—black flag"—dear, dear—most degrading, shocking taste! (To his Friend.) Oh, of course, I'll wait, if you want to see it—not got a [pg 293] penny? Let me see—yes, I can lend you one. (He does; the penny is put in—nothing happens.) Out of order, I suppose—scandalous! and nobody to speak to about it—most discreditable! Stop—what's this? (A sort of woolly beat is audible inside the prison; the C.P. beams.) That's the bell tolling—it's all right, it's working! [It works.

Another Spectator. Very well done, that was—but they 'urried it over a little too quick. I scarcely saw the man 'ung at all!

His Companion. Put in another penny, and p'raps you'll see him cut down, old chap.

Susan Jane (to her Soldier.) Oh, ain't that pretty? I should like to know what my fortune is. [She feels in her pocket.

The Soldier (who disapproves of useless expenditure). Ain't you put in enough bloomin' pennies?

Susan Jane. This is the last. (Reads Directions.) Oh, you've got to set the finger on the dial to the question you want answered, and then put your penny in. What shall I ask her?

Soldier. Anyone would think you meant to go by the answer, to hear you talk!

Susan Jane. P'raps I do. (Coquettishly, as she sets the index to a printed question.) Now, you mustn't look. I won't 'ave you see what I ask!

Soldier (loftily). I don't want to look, I tell yer—it's nothing to me.

Susan Jane. But you are looking—I saw you. [A curious and deeply interested crowd collects around them.

Soldier. Honour bright, I ain't seen nothing. Are you going to be all night over this 'ere tomfoolery?

[SUSAN JANE puts in a penny, blushing and tittering; a faint musical tinkle is heard from the case, and the little fairies begin to revolve in a solemn and mystic fashion; growing excitement of crowd. A pasteboard bower falls aside, revealing a small disc on which a sentence is inscribed.

Person in Crowd (reading slowly over SUSAN JANE's shoulder). "Yus; 'e is treuly worthy of your love."

Crowd (delighted). That's worth a penny to know, ain't it, Miss? Your mind's easy now! It's the soldier she was meanin'. Ah,'e ought to feel satisfied too, after that! &c., &c. [Confusion of SUSAN JANE.

Soldier (as he departs with S.J.). Well, yer know, there's something in these things, when all's said!

A Pleased Pleasure-seeker. Ah, that's something like, that is! I've seen the 'Aunted Miser, and the Man with the 'Orrors, and a Execution, and a Dyin' Child—they do make you larf, yer know!

Second P.P. Yes, it's a pity the rest o'the Exhibition ain't more the same style, to my thinking!

A Captious Critic. Well, they don't seem to me to 'ave much to do with anything naval.

His Companion. Why, it comes under machinery, don't it? You're so bloomin' particular, you are! Wouldn't touch a glass o' beer 'ere, unless it was brewed with salt-water, I suppose! Well, come on, then—there's a bar 'andy!

[They adjourn for refreshment.

PROVERBS PRO OMNIBUS.—Directly the Chairman of the General Omnibus Company observed that if the men's demands were conceded the fares would have to be raised, there was a rush to be the first out with the old proverb about Penny wise and Pound foolish. However, "In for a penny" remains as heretofore, the employés having successfully gone "in for a Pound." Let them now "take care of the pence," and they may feel well assured that this particular POUND will be able to take care of himself. Well, farewell the tranquillity of the streets of last week! Henceforth not "chaos," but "'Bus 'os," has come again!

Dear MR. PUNCH,—I hear that some people are in a great state of mind lest some blessed Bill brought in by the Government, should "destroy Voluntary Schools." What howling bosh! Why, there are no Voluntary Schools! No, they're all Compulsory, confound 'em! or who'd attend 'em? Not Yours disgustedly,

MR. WELLER & CO., AND THE 'BUS STRIKE.—Mr. SUTHERST seems to occupy, as towards the 'Bus-drivers, a similar position to that filled by the eminent Mr. Solomon Pell, the general adviser, and man of business to the Elder Mr. Weller, and his professional coaching brethren. It is to be hoped that the Solomon Pell of the 'Bus-drivers has been treated as liberally as was the real Mr. Pell, the friend of the LORD CHANCELLOR, by Mr. Weller Senior, the Mottle-faced Man, and others.

The most interesting book, one of the Baron's Retainers ("blythe and gay,") has read this year is, The Life of Laurence Oliphant. If it were not written by a reputable person, and published by so eminently respectable a house as BLACKWOOD's, there would be difficulty about accepting it as a true story of the life of a man whom some of us knew, as lately living in London, wearing a frock coat, and even a tall hat of cylindrical shape. Such a mingling of shrewd business qualities and March madness as met in LAURENCE OLIPHANT is surely a new thing. A man of gentle birth, of high culture, of wide experience, of supreme ability, and, strangest of all, with a keen sense of humour—that such an one should voluntarily step down from high social position at the bidding of a vulgar, selfish, self-seeking, and, according to some hints dropped here and there, grossly immoral man, should, at beck of his fat forefinger, go forth to a strange land to live amid sordid circumstances, and with uncongenial company, to work as a common, farm-labourer, to peddle strawberries at a railway station, passes belief. With respect to Mr. HARRIS, one feels inclined to quote Betsy Prig's remark touching one who may, peradventure, have been a maternal relation. "I don't believe," said Betsy, "there's no sich a person." But there was, and, stranger still, there was a LAURENCE OLIPHANT to bend the knee to him. Not the least striking thing in a book of rare value is the manner in which Mrs. OLIPHANT has acquitted herself in a peculiarly difficult task. No man would have had the restraining patience necessary to deal with the HARRIS episodes as she has done.

The Assistant Reader has been refreshing himself with Lapsus Calami, by J.K.S., published by MACMILLAN and BOWES. It is a booklet of light verse, containing here and there some remarkably brilliant pieces of satire and parody. The first of two parodies of ROBERT BROWNING is unsurpassable for successful audacity. The last poem in the book is "An Election Address," written for, but apparently not used by, the present POSTMASTER-GENERAL, when he was Candidate for Cambridge University, in 1882. He says of himself, after confessing to a dislike for literature and science,—

"But I have fostered, guided, planned

Commercial enterprise; in me

Some ten or twelve directors, and

Six worthy chairmen you may see."

All the pieces are not so good as those cited—that would be too much to expect—but "get it," say

ANDREW LANGUAGE—no, LANG!—who the classics is pat in,

Suggests to our writers, as test of their "style,"

Just to turn their equivocal prose into Latin,

As DRYDEN did. Truly the plan makes one smile!

Reviewers find Novelists' nonsense much weary 'em.

Writers of twaddle

Take DRYDEN a model—

Turn your books into some great "dead language"—and bury 'em!

Will you, if you please, point out to me the way to the streets which, I am told, are paved with gold?

Where shall I find the employer of labour who, I have been told, will instantly get me occupation at a wage of 60 roubles the week?

Dear me! in this, then, your "White Chapel"? I was told it was a luxurious quarter, famous for its Palaces.

Surely this horrid den is not one of your model work-rooms? I was told that such things existed only in Russia!

And are these people who are scowling at and cursing me your typical working population? Why, I was told that I should find them dear brothers, waiting to welcome us with open arms.

And is this pittance you offer me all that you pay for making a coat? I was told that it was quite twelve times as much as this.

Ah! I'm afraid I have been told, and have given credit to, a great many things to which I never should have listened at all.

Lady Godiva de Rougepott. "I DON'T THINK ANY PAINTING LOOKS WELL IN THIS HORRID ELECTRIC LIGHT!"

Hostess (nettled). "DON'T YOU, DEAR? PERHAPS YOU WOULD PREFER TO REMAIN IN THE DRAWING-ROOM, WHERE THE LAMPS AND SHADES ARE!"

"To the bi-monthly exhibition of the Royal Horticultural Society the Marquis of SALISBURY sent a magnificent collection—of strawberries especially. Mr. W.H. SMITH showed specimens of the same luscious fruit, for which he received the thanks of the Society."—Daily Telegraph.

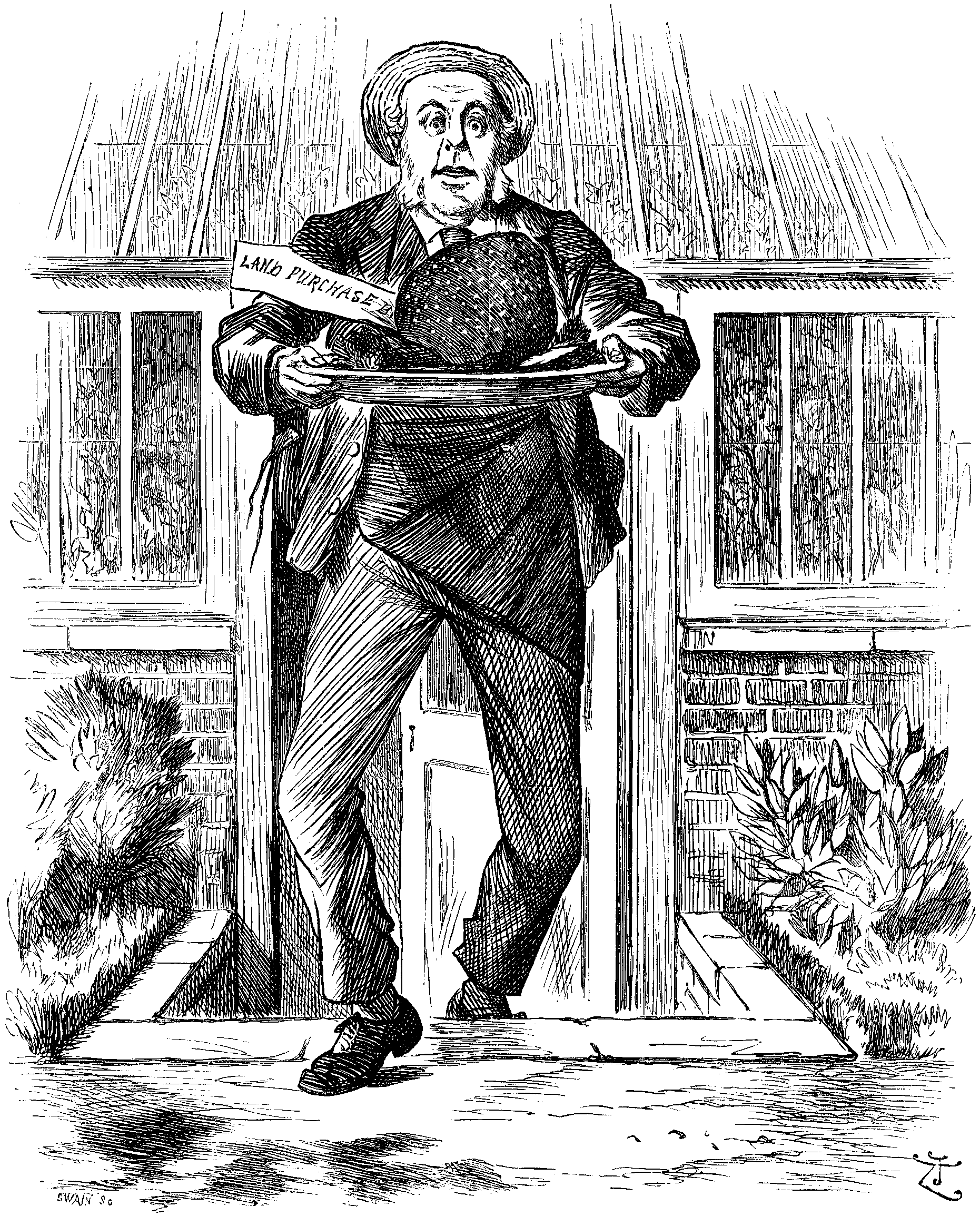

Head-Gardener SM-TH soliloquiseth:—

OHO! my beauty! If you don't get a fust prize, and "receive the thanks of the Society" I'm a cowcumber! "The Fruits of Early Industry and Economy." Title of a picture by that splendid sample of the industrious and the economical, GEORGE MORLAND, I believe. Yes, that's it. My Industry and G-SCH-N's Economy.

We are a moral family;

We are, we are, we are!

All the cardinal virtues bound in—ahem! no matter.

Talk of the Gigantic Gooseberry! What is that apocryphal monstrosity compared with this Brobdingnagian Berry? [Sings.

Bravo, my "British Queen"!

Long live my "British Queen"!

Brave "British Queen"!

Send it victorious,

First-Prizer glorious,

Fill Rads censorious

With envious spleen!

As you will, my Beauty! When did swaggering H-RC-RT's horticulture produce such goodly fruits? Or sour-mug'd M-RL-Y's? Or leary L-BBY's? Or Slawkenbergian M-ND-LLA's? Or even that of the Grand Old Grower, GL-DST-NE himself, with all his fluent patter about British Pomona, and the native Jam-pot?

I know the badly-beaten lot maintain that the plant is a "Sport" from an old purchase of their own. Bless you, they claim all the good stocks—always did. Who cares? My young floricultural friend, JOE of Birmingham, who knows a bit about fruits as well as concerning orchids, let me tell you,—JOE, I say, laughs their preposterous pretensions to scorn. Look at G-SCH-N's own particular plant there—a bit late, but very promising, and probably destined to take a prize before the season's over. Didn't JOE recommend the stock to GL-DST-NE years ago? And didn't the haughty Hawarden horticulturist turn up his nose at it as an "Unauthorised" intruder upon his own Prize Programme? And, more by token, didn't JOE get the hump in consequence, cut the old connection, and set up on his own account in the forcing-house line, with a friendly leaning to our firm? Aha! "Hinc illæ lachrymæ," as the Guv'nor would say. Hence, also, this Colossal Strawberry!

Thanks of the Society? I should rayther think so! They may chaff "OLD MORALITY" as much as they like—but morality pays, even in strawberry-growing; and my duty to my (British) Queen has brought about this triumph. Early Industry started it, and careful horticultural Economy brought it to its present pitch of perfection. Look at it! Size, shape, sweetness, scent, all superb! If the Season shouldn't produce another Prize-Winner, this alone ought to satisfy SOLLY. And if G-SCH-N's seedling, "Gratis," should turn out a triumph later on, why we shall score tremendously. Wish G-SCH-N would "sit up and snort" less, and smile more. Patience and plenty of sun! That's the tip for a horticulturist. Standing at the door and shying stones at your neighbour's glasshouses, won't make your own fruit ripen, if GEORGE JOKIM could only see it. As H-RT D-KE says, tu quoques are a nuisance, and want fumigating off the face of the earth. JOKIM and ARTHUR B-LF-R a bit too fond of 'em for my fancy. However, all the "you're anothers" on earth can't affect my Strawberry now, thanks be! The Fruit of the Season, though I say it who perhaps shouldn't.

(Sings.) From "Greenlands" sunny garden,

And vista'd vitreous panes,

We mean to rival Hawarden,

In glories and in gains.

I have produced, Sweet WILL-I-AM,

This Giant Strawber-ry,

In horticultural skill I am

A match for W.G.! [Left chortling.

THE VERY LAST ON THE 'BUS STRIKE.—After the comparative quiet of last week, the streets of London will now be as 'bussy as ever.

W.H. SM-TH (Head Gardener and Prize Exhibitor). "HAD TO NIP OFF A LOT OF BLOOMS TO GET HIM UP TO THIS SIZE!!"

"At the Bimonthly Exhibition of the Royal Horticultural Society ... Mr. W.H. SMITH showed specimens of the same luscious fruit"—strawberries—"for which he received the thanks of the Society."—Daily Telegraph, Wednesday, June 10.

PORTRAIT OF A LITERARY FRIEND, WHO, LIVING IN A MAIN THOROUGHFARE, WAS AN ARDENT SUPPORTER OF THE 'BUS STRIKE, SUBSCRIBED TO ITS FUNDS, ADD HOPED IT MIGHT LONG CONTINUE. HE SAYS HE HASN'T HAD SUCH A QUIET TIME WITH HIS BOOKS FOR YEARS. BUT ALAS! SINCE LAST SUNDAY HE HAS NOT SMILED AGAIN.

"The demand for 'Buses is immensely stimulated by their presence, and when they are no longer there, the people who thought them indispensable get on very well indeed without them.... Under the influence of penny fares, Londoners are rapidly forgetting how to walk."—The Times.

Ah! it's all very fine, my good Sir, whosomever you are as writes such,

But of decent poor folk and their needs it is plain as you do not know much.

Which I ain't quite so young as I was, nor as light, nor as smart on my feet,

And you may not know quite what it is to be out late o' night and dead beat,

Out Islington way, arter ten, with a bundle, a child, and a cage,

As canaries is skeery at night, and a seven mile walk, at my age,

All along of no 'Bus to be had, love or money, and cabs that there dear,

And a stitch in my side and short breath, ain't as nice as you fancy,—no fear!

Likeways look at my JOHN every morning, ah! rain, hail or shine, up to town,

With no trams running handy, and corns! As I sez to my friend Mrs. BROWN,

Bless the 'Buses, I sez, they're a boon to poor souls, as must travel at times,

And we can't all keep kerridges neither, wus luck! Penny Fares ain't no crimes,

If you arsk me, as did ought to know. Which my feelings I own it does rouge

To hear big-wigs a-sneering at 'Buses. There may be a bit of a scrouge,

And the smell of damp straw mixed with pep'mint ain't nice to a dalicot nose,

Likeways neat "Oh be Joyful's" a thing as with orange and snuff hardly goes.

But we ain't all rekerky nor rich, we can't all afford sixpence a mile,

And when we are old, late, and tired, or it's wet, we can't think about style.

The 'Bus is the poor body's kerridge, young feller—and as for your talk

About not never missing a lift, or forgetting—dear sakes!—how to walk,

And the nice quiet streets and all that; why it's clear you ain't been a poor clerk

With a precious small "screw," in wet weather. Ah! you wouldn't find it no lark

With thin boots and a 'ard 'acking cough, and three mile every day to and thro',

Or a puffy old woman like me, out at Witsuntide wisiting JOE,

(My young son in the greengrocer line); or a governess, peaky and pale,

As has just overslep herself slightly, and can't git by cab or by rail.

"Ugly lumbering wehicles?" Ah! and we're ugly and lumbering too,

A lot of us poor Penny 'Bus fares, as isn't high-born or true-blue.

But the 'Bus is our help. Wery like some do ride as had far better walk,

Whether tip-toppy swells or poor shop-girls. But all that is trumpery talk.

What I arsk is, why shouldn't the 'Buses be kept a bit reglar, like Cabs,

In the matter of fares and of distances? Oh, a old woman it crabs

To hear of Perprietors pinching pore fellers as drive or conduck,

While the "Pirates" play up merry mag with the poor helpless fare, as gets stuck

Betwixt Dividend-grinders and Strikers? It ought to be altered, I say.

Whilst they talk of what 'Bus-folk should earn, they forget the pore Publick—who pay!

My life is held to be a round of Pleasures;

All I can say is, they who thus would rate it,

For life's delights have most peculiar measures:

For though in plainest English they don't state it,

'Tis clear "no recreation" meets their views,

Or why that sneering cry, "Le Prince s'amuse?"

Or do they think a Prince, without repining,

Foundation-stones unceasingly is laying,

Rewarded with a glut of public dining,

The pangs of hunger ever to be staying,

Is recreation such as he would choose?

If so—I understand "Le Prince s'amuse!"

But how a world that notes his daily doings,

The everlasting round of weary function,—

The health-returnings, speeches, interviewings.

Can grudge him some relief, without compunction,

Seems quite to me "another pair of shoes!"

Dyspeptic is that cry, "Le Prince s'amuse!"

I must confess I was agreeably surprised at the treatment to which I was subjected by my capturers. Instead of being loaded with chains and confined in a cell beneath the castle's moat, I was given perfect liberty, and had quite a pleasant suite of rooms. I should scarcely have known that I was in durance had not one of the less refined of the brigands shown me a revolver, and playfully informed me that its contents were intended for me if I attempted to escape. The Chief was absolutely charming. He treated me in the most courteous manner, and ended his first interview with me by requesting "the honour of my company at dinner."

"You need not dress!" he observed, "although I like to put on a tail-coat myself. But I know that you have had some difficulty with my people about your luggage, and so I shall be only too delighted to excuse grande tenue."

The "difficulty" to which my host referred was the seizing of my portmanteau by the gang of thieves of which he was the acknowledged head. I suggested that I might possibly recover some of its contents.

"I am afraid not," returned the Chieftain. "You see my people are very methodical, and by this time I fear all the goods will have been sold. The motto of the Club is 'small profits and quick returns.' We find no difficulty in trading. As we carry on business on the most economical principles, we can quote prices even cheaper than the Stores."

And this I found to be the case. Although the brigands were very civil to me, I was unable to trace any of my property. However, as my host in the kindest manner had allowed me to dispense with ceremony, I ventured to appear at dinner-time in my ordinary tourist's dress.

"I am delighted to see you," said the Chief, speaking English for the first time, "as you are now my guest, I must confess that we are fellow countrymen."

"Indeed!" I replied, considerably astonished. "If you are really of British nationality, how is it that I find you a professional thief?"

"You are mistaken," returned the Chief. "I merely belong to a society for the redistribution of capital. You know we are all balloted for, and I was myself afraid that I might get pilled."

"Indeed!" I exclaimed, in a tone of surprise. "Surely your accomplishments—for I noticed, on my arrival, that you were a first-rate hand at lawn tennis, and played the flute—would have secured your admission?"

"Well," he returned with a smile, "I fancy they helped me with the Committee. But unhappily my antecedents were bad—I had made a fortune on the London Stock Exchange, and my books were scarcely as satisfactory as our bandit auditors could have desired them to be. However they took a kindly view of the case, and allowed me to pass through. But pardon me, I see your ransom has arrived. I am afraid I must say good bye. A pleasant journey."

And shaking me warmly by the hand, he helped me into the conveyance that was to take me back to home and freedom. I have never seen him since.

PARIS, June 15.—It is stated here, on no authority whatever, that when the CZAR was recently visiting the French Exhibition at Moscow, his Imperial Majesty was heard to remark, "This makes me desire to see the Boulevards again." A visit of the ruler of Russia to Paris during the Summer is therefore considered to be certain. An offensive and defensive Alliance between the two countries is said to be on the point of signature.

A few evenings ago, in a low café in Belleville, M. NOKASHIKOFF, who left St. Petersburg lately to escape his creditors, and who conceived the happy idea of raising a little money by walking to Paris in a sack composed of the French and Russian national flags stitched together, was entertained to supper by his Gallic admirers. The proceedings, especially towards midnight, were very enthusiastic. Throughout the festivities, constant cries of "Vive l'Alliance Franco-Russe!" were raised. This incident is said to have placed the immediate signature of the Treaty between the CZAR and President CARNOT beyond a doubt.

Last evening a foreigner, who by appearance would have been taken for a Muscovite, was walking along the asphalte, when he was surrounded by a crowd of persons crying "Vive la Russie!" The foreigner seemed both surprised and annoyed by these attentions, and at length began to use his fists and his boots liberally on the ringleaders of the mob. This treatment, however, seemed only to increase their Russophil ardour, and the stranger was soon hoisted on to the shoulders of some of his foremost admirers, struggling violently. On the arrival of a gendarme, he explained that he was an English book-maker, and that "this bloomin' mob of boot-lickers had taken him for a bloomin' Russian!" The crowd shortly afterwards dispersed. The completion of the formal alliance between France and Russia is considered less certain than it was a few days ago.

The Frenchman, M. TÊTE-BOIS, who recently attempted to walk on his head from Paris to Moscow, in order to show the sympathy felt in France for the Muscovite Empire, did not succeed in carrying out his design. He was stopped shortly after crossing the Russian frontier, imprisoned, and heavily ironed. After suffering in this way for a week, he was told that he must leave Russian territory within twenty-four hours, or else continue his journey to Siberia. On being appealed to, the CZAR graciously extended the time given for quitting Russia to forty-eight hours. This Imperial clemency has caused the widest feeling of gratitude and satisfaction in France, and the signature of the definitive Alliance between the two countries is confidently expected at an exceedingly early date.

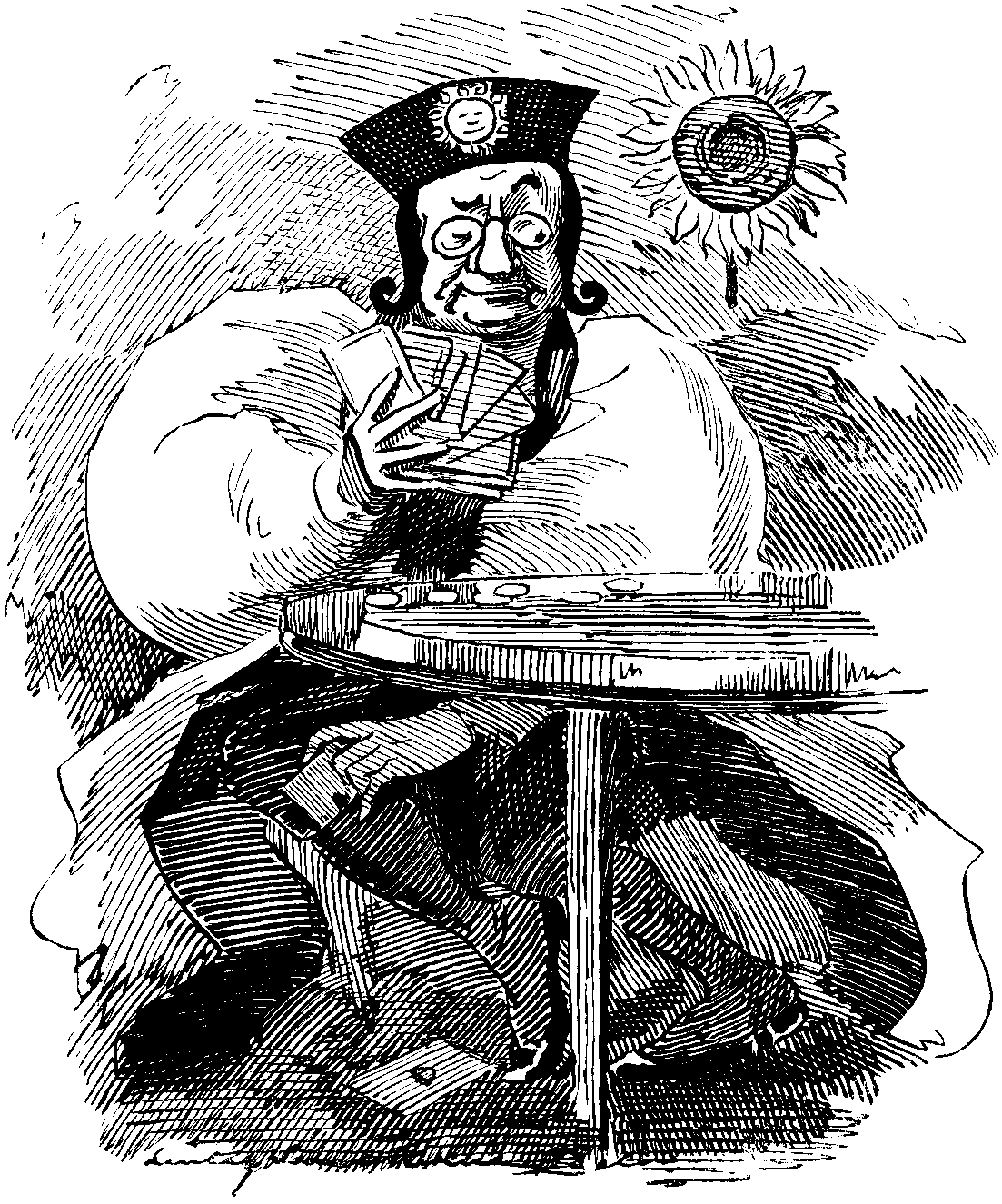

"THE LORD ARCHBISHOP OF NOVA SCOTIA, PRELATE OF THE ORDER OF THE SUN," CAUGHT CHEATING AT CARDS (HYPOTHETICALLY) BY THE LORD CHIEF JUSTICE, AND TAKEN, INSTANTANEOUSLY, BY OUR ARTIST.

House of Commons, Monday Night, June 8.—I knew DYKE first when (good many years ago now) as DIZZY's whip he hunted in couple with ROWLAND WINN; then always called HART DYKE. Like many other young men he has in interval lost his HART, and now known as Sir WILLIAM DYKE. Curious thing, as SARK reminds me, how absorbent is the name of WILLIAM. Quite probable that before Black-Eyed Susan's friend came prominently on the stage he had some other Christian name, sunk when he was promoted to shadow of yard-arm. Certainly there is an equally eminent man sitting opposite DYKE in House to-night, who like him is "Sir WILLIAM" to the present generation, and was VERNON HARCOURT to an elder one.

DYKE, under whatever name, done excellently well to-night. Holding comparatively minor appointment in Ministry, suddenly finds himself in charge of principal measure of Session. Handicapped, moreover, with recollections of time when he has uncompromisingly declared himself against the very principle he now embodies in Bill, and invites House to add to Statute Book.

That was first hedge for DYKE to take, and he went over in plucky style that threw the scorner off his trail. Didn't live in close communication with DIZZY through six long years for nothing. Not likely to forget what happened in very earliest days of Parliament of 1874, when DIZZY for first time found himself not only in office but in power. During election campaign DIZZY, speaking in the safety of Buckinghamshire, had made some wild statement about easing the chains of Ireland. Simply designed to gain Irish vote; forgotten as soon as spoken. But ROBERT MONTAGU—where, by the way, is ROBERT MONTAGU?—treasured these things up in his heart, and when DIZZY appeared in the House, Leader of triumphant majority, asked him what he was going to do about it?

"It is sometime since the observations referred to were made," said DIZZY, "and—er—a good deal has happened in the interval."

DYKE, recalling and admitting his former statements on Free Education, did not attempt to minimise their import. "But." he said, button-holing House as it were, and treating it quite confidentially, "the fact is we all change our minds." House laughed at this as it had laughed at DIZZY seventeen years ago, and DYKE, absolved and encouraged, went forward with his speech.

Not a brilliant oration in any way; neither exordium nor peroration, and the middle occasionally a little mixed. But a good sensible straightforward speech, and if DYKE had done no more than show that an important Ministerial measure could be explained within limit of an hour, he would not have lived in vain.

Business done.—Education Bill introduced.

Tuesday.—Nothing at first sight in personal appearance of HERBERT THOMAS KNATCHBULL-HUGESSEN that suggests a swan. Fancy I have heard something of these birds being addicted to the habit of breaking forth into song when convinced of approaching dissolution. That, I suppose, is how the swan was suggested to the mind when just now, KNATCHBULL-HUGESSEN rose from behind Ministers, and began to chant his threnody. Resolution on which Education Bill grafted brought up for report stage; agreed to, and HART DYKE about to bring in his Bill. Then from the back seat rose a sturdy yeoman figure, and a powerful voice was uplifted in denunciation of the Bill and of a Ministry that had betrayed the trust of the Conservative Party. It was, so the swan sang, a step on the road to Socialism. He feared it had come to pass that dangerous measures are more likely to emanate from the Treasury Bench than from the Front Bench opposite.

Liberals roared with delighted laughter and cheers; the Conservatives sat glum and ill-at-ease. OLD MORALITY's white teeth gleamed with a spasmodic smile. As for JOKIM he folded his arms, and bit his lips and frowned.

"What antiquated nonsense this is!" he muttered, "of course Free Education is not a Conservative principle. They all protested against it at the General Election. A year earlier I, who happened at the time to be numbered in the Liberal ranks, put my back [pg 300] against the wall, and, picturing the evils that would befall my country if its institutions were thus demoralised, I said I would die before I would lend a hand to free the schools. But you see, TOBY, I haven't died, and that changes the whole situation. Not only enables me to retain my place in Government bringing in Free Education, but permits me, as CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER, actually to find the means for carrying out the system. Can't understand a fellow like this KNATCHBULL-HUGESSEN sticking to his principles when it becomes expedient to swallow them. He's a disgrace to a family that counts BRABOURNE as its head."

"HUGESSEN's a good fellow," said ISAACSON; "wears well, but is politically a fossil. Now I'm a progressive Conservative, which I think you'll find, TOBY, my boy, to be about the time of day."

Business done.—Assisted Education Bill; firmly led up to table by HART DYKE.

Wednesday.—Lively fight round Deceased Wife's Sister Bill. Ascot in vain held forth its attractions; supporters of the Bill hoped opponents would go; opponents came down rather expecting HENEAGE's virtue would have given way, and Ascot would have claimed him as its own. But everybody there—MAKINS's men with long list of Amendments warranted to keep things going till half-past five, when progress must be reported, and chance of Bill for present Session lost. MAKINS himself in high oratorical feather. OSBORNE-AP-MORGAN, having made a proposition and subsequently withdrawn it, MAKINS, putting on severest judicial aspect, observed, "It is all very well for the Right Hon. and learned Gentleman to make a legal JONAH of himself and swallow his opinions."

"Bless us all!" cried ROWNTREE, looking on with blank amazement, "MAKINS evidently thinks that JONAH swallowed the whale." Bill seemed to shatter friendships and dissever old alliances. SQUIRE of MALWOOD naturally at home in the fray, but rather startling to find HOME SECRETARY running amuck at CHAMBERLAIN. MATTHEWS in his most hoity-toity mood; quivered with indignation; thumped the table; shook a forensic forefinger at the undesignedly offending JOSEPH, and, generally, went on the rampage. As for HENEAGE, he filled up any little pause in uproar by diving in and moving the Closure. Once, whilst GEDGE was opposing an Amendment hostile to Bill, HENEAGE dashed in with his Closure motion. GEDGE's face a study; mingled surprise, indignation, and ineffable regret mantled his mobile front.

"To think," he said afterwards, "that just when I was coming to HENEAGE's help with an argument founded on profound study and pointed with legal lore, he should suddenly jump up, lower his head, and, as it were, butt me in the stomach with the Closure. It is more than I can at the moment comprehend."

GEDGE so flurried that when Members returned, after Division on Closure, he being, in accordance with the rule, seated and wearing his hat, wanted to argue out the question with COURTNEY.

"I submit, Sir," he said, "that the Hon. Member, in moving the Closure, controverted Rule 186."

The Chairman: "I think the Hon. Member can scarcely have read the Rule."

Mr. GEDGE: "I have read the Rule, Sir. This is what it says—"

Chairman: "Order! Order!" and GEDGE subsided.

Then TOMLINSON fortuitously turning up on Treasury Bench, joined in conversation. But COURTNEY turned upon him with such a thunderous cry of "Order! Order!" that TOMLINSON visibly shrivelled up, and his sentence, like the unfinished window in ALLADIN's Tower, unfinished must remain.

Wrangling went on till a quarter past five, when TALBOT interposed, and with most funereal manner moved to report progress. HENEAGE almost mechanically lowered his head and had started to butt at TALBOT as he had upset GEDGE when he was providentially stopped and convinced that further struggle with obstruction was hopeless. So, Clause I. agreed to, Bill talked out. MAKINS, growing increasingly delightful, protested that a Bill that had been fifty years before the country, was not to be rushed through the House on a Wednesday afternoon. Argal, the more familiar the House is with the details of a measure, the more necessary is it to debate it.

Business done.—Marriage with a Deceased Wife's Sister. Banns again objected to.

Saturday, 1:25 A M.—Land Bill just through report stage. Nothing left now but Third Reading. "Well, KNOX," said WINDBAG SEXTON, "that will be our last opportunity, and we must make the most of it. In meantime I think we've done pretty well. I'm especially pleased with you. You're a boy of great promise. If anything happened to me—a stray tack in the bench, or a pin maliciously directed, and the wind-bag were to collapse—you'd do capitally, till I got it repaired."

WINDBAG JUNIOR blushed. As OLD MORALITY remarks, Ingenuous youth delights in the Approbation of Seasoned Seniority.

Business done.—Land at last—I mean Land Purchase Bill through at last.

SCENE—Tent in rear of a Battle-field. Political Officer in attendance upon Army, waiting for Military assistance.

Political Officer (impatiently). Now then, Orderly, have you not been able to secure a General for me?

Orderly (saluting). Beg pardon, Sir, but it's so difficult, since they have passed that new Royal Warrant, to know which is which.

Pol. Off. (more impatiently). Nonsense!—any General Officer will do. Ord. Very good, Sir.

[Exit. Political Officer stamps his foot irritably, when enter First General Officer, hurriedly.

First Gen. Off. Well, Sir, how can I assist you?

Pol. Off. (cordially). Glad to see you, General. Fact is, supposing we arrange a treaty, do you think it would be wise to surrender the fortress on the right side of the river, if we retain the redoubt near the wood as a basis of operations? You see—

First Gen. Off. (interrupting). Very sorry, but don't know anything about it.

Pol. Off. (annoyed). But aren't you a General?

First Gen. Off. Certainly. General-Surgeon. Ta, ta! [Exit.

Pol. Off. Well of all the—(Enter Second Gen. Off.) Well, Sir, what is it? Who are you?

Second Gen. Off. I am a General Officer, and I was told you required my poor services.

Pol. Off. So I do. The fact is, General, supposing we arrange a treaty, do you think it wise for us to surrender the fortress—

Second Gen. Off. (interrupting). Alas! my dear friend, I fear I can be of no help to you—it is entirely out of my line.

Pol. Off. (annoyed). But aren't you a General?

Second Gen. Off. Certainly. A General-Chaplain. Farewell, dear friend. [Exit.

Pol. Off. Well of all the—(Enter Third General Officer.) Well, Sir, who and what are you?

Third Gen. Off. (briskly). A General. Now then, look sharp! No time to lose. Hear you require me. How can I help you?

Pol. Off. (aside). Ah, this is the sort of man I want! (Aloud.) Well then, General, we are arranging a treaty, and I want your advice about retaining a fortress on the right of the river—

Third Gen. Off. (interrupting). Sorry. Can't help! Not my province. Good bye! [Exit.

Pol. Off. (shouting after him). But aren't you a General?

Third Gen. Off. (voice heard in the distance.) Yes. General-Postman!

[Scene closes in upon political official language unfit for publication.

MUSICAL NOTES.—Saturday Afternoon.—Albert Hall jubilant. M. PLANCON or PLANÇON—the production of the "c" depending on the state of his voice—was encored and "obliged again." So did Madame ALBANI, who was in superb voice. But her accompanist, M. CARRODUS, who had given us one violin obbligato, did not obbligato again, and so Madame sang, admirably of course, the ever-welcome "Home, Sweet Home." GIULIA RAVOGLI gave her great Orphéo song, and DRURIOLANUS, practising courtly attitudes, as one preparing to receive a German Emperor, smole beamingly on the gratified audience. At The Garden, Mireille, revived on Wednesday last, hasn't much life in her, but Miss EAMES charming.

NOTICE.—Rejected Communications or Contributions, whether MS., Printed Matter, Drawings, or Pictures of any description, will in no case be returned, not even when accompanied by a Stamped and Addressed Envelope, Cover, or Wrapper. To this rule there will be no exception.