The Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, Or The London Charivari, Vol. 103, Sep. 24, 1892, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Punch, Or The London Charivari, Vol. 103, Sep. 24, 1892 Author: Various Release Date: March 15, 2005 [EBook #15366] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH *** Produced by Malcolm Farmer, William Flis, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team.

DEAR CHARLIE,—Rum mix this 'ere world is, yer never know wot'll come next!

Don't emagine I've sent yer a sermon, and treacle this out as my text;

But really life's turn-ups are twisters. You lay out for larks, 'ealth, and tin,

But whenever you think it's "a moral," that crock, "Unexpected," romps in.

Who'd ha' thought of me jacking up suddent, and giving the Sawbones a turn?

Who'd ha' pictered me "Taking the Waters"? Ah! CHARLIE, 'twos hodds on the Urn

With Yours Truly, this time, I essure you. I fancied as Tot'nam-Court Road

Would he trying its 'and on my tombstone afore the green corn wos full growed.

Bad, CHARLIE? You bet! 'Twas screwmatics and liver, old Pill-box declared.

Knocked me slap orf my perch, fair 'eels uppards. I tell you I felt a bit scared,

And it left me a yaller-skinned skelinton, weak, and, wot's wus, stoney-broke.

If it hadn't a bin for my nunky, your pal might have jest done a croak.

Uncle NOBBS, a Cat's-butcher at Clapton, who's bin in luck's way, and struck ile,

Is dead nuts on Yours Truly. Old josser, and grumpy, but he's made his pile.

Saw me settin' about in the garden, jest like a old saffron-gill'd ghost

A-waiting for cock-crow to 'ook it, and hanxious to 'ear it—a'most.

Sez he, "Wy, the boy is a bone-bag! Wot's that? Converlescent? Oh, fudge!

He's a slipping his cable, and drifting out sea-wards, if I'm any judge.

I was ditto some twenty year back, BOB, and 'Arrygate fust set me up.

Wot saved the old dog, brother ROBERT, may probably suit the young pup.

"Carn't afford it? O'course yer carn't, JENNY; but—thanks be to 'orse-flesh—I can—"

Well, he tipped us a fifty-quid crisp 'un—and ROOSE sent me 'ere; he's my Man!

Three weeks' "treatment"! Well, threes into fifty means cutting a bit of a dash;

Good grub, nobby togs, local doctor, baths, waters, and everythink flash.

"'Appy 'ARRY!" sez you. But way-oh, CHARLIE! 'Arrygate isn't all jam.

Me jolly? Well, mate, if you arsk me, I carn't 'ardly say as I ham.

To spread myself out with the toppers is proper, no doubt, bonny boy;

But—I wish it wos Brighton, or Margit, or somewheres a chap could enjoy.

Oh, them "Waters," old man!!! S'elp me never! yer don't kow wot nastyness is

Till you've tried "Sulphur 'ot and strong," fasting. The Kissing Gin, taken a-fizz,

Isn't wus than ditch-water and sherbet; but Sulphur!!! It's eased my game leg;

But I go with my heart in my mouth, and I feel like a blooming bad hegg.

B-r-r-r-r! Beastliness isn't the word, CHARLIE. Language seems out of it, slap.

When I took my fust twelve ounces 'ot, from a gal with a snowy white cap,

And cheeks like a blush-rose for bloominess—well, I'm a gent, but, yah-hah!

I jest did a guy at the double, without even nodding ta-ta!

Where the Primrose Path leads to, my pippin, I'm cocksure can't 'ave a wus smell.

Like bad eggs, salt, and tenpenny nails biled in bilge water. Eugh! Old Pump Well?

Wy then let well alone, is my motter, or leastways, it would be, I'm sure,

But for BLACK—local doctor, a stunner!—who's got me in 'and for a cure.

I'm not nuts on baths took too reglar; but 'Arrygate baths ain't 'arf bad,

When you git a bit used to 'em, CHARLIE. I squirmed, though fust off, dear old lad!

They so soused, and so slapped, and so squirted me. Messing a feller about

Don't come nicer for calling it massage. But there, it's O.K. I've no doubt.

They squat you upon a low shelf, with a sort of a water-can "rose"

At the nape of yer neck, while a feller in front squirts yer down with a 'ose.

He slaps you as though you wos batter, he kneads you as if you wos dough,

And gives yer wot for on the spine, till you git in a doose of a glow.

Then you're popped in a big iron cage, where the 'ose plays upon you like fun;

A lawn, or a house a-fire, CHARLIE, could not be more thoroughly done.

Sez I, "I'm insured, dontcher know, mate; so don't waste the water, d'ye 'ear?"

But he didn't appear to arf twig. He seemed jest a bit thick in the clear.

Then the bars of yer cage bustes out like a lot of scent fountings a-play—

'Taint oder colong, though, by hodds; sulphur strong seems the local bokay.

They call this the "Needle Bath," CHARLIE. It give me the needle fust off;

'Cos the spray would git into my eyes, and the squelch made me sputter and cough.

Then they wrop you well up in 'ot towels, and leave yer five minutes to bake,

And that's the "Aix Douche," as they call it. I call it the funniest fake

In the way of a bath I 'ave met with; but, bless yer, it passes the time,

And I shan't want a tub for a fortnit when back in Old Babbylon's grime.

Dull 'ole, this 'ere 'Arrygate, CHARLIE! The only fair fun I can find

Is watching the poor sulphur-swiggers, a-gargling and going it blind.

Oh, the sniffs and sour faces, old fellow, the shudders and shivers, and sighs;

The white lips a-working like rabbits', the sheepish blue-funk in their eyes!

Old Pump Room's a hoctygon building, rum blend like of chapel and bar,

With a big stained-glass winder one side, hallygorical subject! So far

As I've yet made it out, it's a hangel a-stirring up somethink like suds.

"A-troubling the waters," I 'eard from a party in clerical duds.

You arsk, like you do at a bar, for the speeches of lotion you want.

Some say; you git used to the flaviour, and like it! Bet long hodds I shan't.

I've sampled the lot, my dear CHARLIE, Strong Sulphur and Mild, Cold and 'Ot;

And all I can say is, the jossers who say it ain't beastly talk rot.

You jest fox their faces! They enters, looks round, gives a shy sort of sniff,

Seem to contemplate doing a guy, brace their legs, keep their hupper lips stiff;

Take their tickets, walk up to the counter, assumin' a sham sort of bounce,

And ask, shame-faced like, for their gargle, 'as p'r'aps is a 'ot sixteen hounce.

When they git it, a-fume in a tumbler, a-smelling like hegg-chests gone wrong,

They squirm, ask the snowy-capped gurl, "Is this right?"—"Yes, Sir. Sixteen ounce, strong!"

Sez the minx with a cold kind o' smile. "Ah—h—h! percisely!" they smirks, and walks round,

With this "Yorkshire Stinko" in their 'ands—and their 'earts in their mouths I'll be bound.

Then—Gulp! Oh Gewillikins, CHARLIE! it gives yer the ditherums, it do.

Bad enough if you 'ave to wolf one, but it fair gives yer beans when 'tis two.

The wictims waltz round, looking white, wishing someone would just spill their wet,

And—there's 'ardly a glass "returned empty" but wot shows its 'eel-taps, you bet!

This is "Taking the Waters" at 'Arrygate! Well, I shall soon take my 'ook.

Speshal Scotch, at my favourite pub, from that sparkling young dona, NELL COOK,

Will do me a treat arter this, mate, and come most pertikler A 1.

'Ow I long to be back in "The Village," dear boy, with its bustle and fun!

Still, the air 'ere's as fresh as they make it, and gives yer a doose of a peck,

And DUNSING, the Boss at "The Crown," does yer proper. I came 'ere a wreck;

But sulphur, sound sleep, and cool breezes, prime prog, and good company tells;

So 'ere's bully for 'Arrygate, CHARLIE, in spite of rum baths and bad smells.

That Fifty is nearly played out, and my slap at the Ebor went wrong—

I'd a Yorkshire tyke's tip, too, old man; but I'm stoney, though still "going strong"

(As Lord Arthur remarks in the play), so no more at "The Crown" I must tarry,

But if 'Arrygate wants a good word—as to 'ealth—it shall 'ave it from

Newspaper Boy (suddenly, at window). "WANT AN OBSERVER, CAPTAIN?"

Mathilde (on Honeymoon Trip). "OH, FREDDIE, DEAR! NO! NO!! DO LET US BE QUITE ALONE!"

"Mayhap you have heard, that as dear as their lives,

All true-hearted Tars love their ships and their wives."

So DIBDIN declared, and he spoke for the Tar;

He knew Jack so well, both in peace and in war!

But hang it! times change, and 'tis sad to relate,

The old Dibdinish morals seem quite out of date;

Stick close to your ship, lads, like pitch till you die?—

That sounds nonsense to-day, and I'll tell ye for why.

The good old Foudroyant—how memory dwells on

Those brave fighting names!—was once flag-ship to NELSON.

But NELSON, you know, died a good while ago,

And his flag-ship has gone a bit shaky, and so

JOHN BULL, who's now full of low shopkeeping cares,

And thinks more of the Stocks than of naval affairs,

Regards not "Old Memories," that "eat off their head."

Turn old cracks out to grass? No, let's sell 'em instead!

A ship's like the high-mettled racer once sung

By that same dashing DIBDIN of patriot tongue,

Grown aged, used up, is he honoured? No, zounds!

"The high-mettled racer is sold to the hounds!"

And so with a barky of glorious name,

(It is business, of course—and a Thundering Shame!)

Worn out, she is nought but spars, timbers and logs,

And so, like the horse, should be sold—to the dogs!

As for the Foudroyant, the vessel was trim

When it fought with the French, for JOHN BULL, under Him,

The Star of the Nile. Yes, it carried his flag,

When it captured the Frenchman. There's no need to brag,

Or to say swagger things of a generous foe.

Besides, things have doosedly altered, you know.

We're no more like NELSON than I to a Merman;

We can sell his flag-ship for firewood, to the German!

Sounds nice, does it not? If that great one-armed Shade

Could look down on the bargain he'd—swear, I'm afraid

(If his death-purged bold spirit held yet ought of earth).

And I fancy 'twill move the gay Frenchman to mirth

To hear this last story of shop-keeping JOHN—

Or his huckster officials. The Frenchman, the Don,

The Dutchman, all foes we have licked,—may wax bold

When they hear that the brave old Foudroyant is—Sold!!!

Great TURNER has pictured the old Téméraire

Tugged to her last berth. Why the sun and the air

In that soul-stirring canvas, seem fired with the glory

Of such a brave ship, with so splendid a story!

Well, look on that picture, my lads, and on this!

And—no, do not crack out a curse like a hiss,

But with stout CONAN DOYLE—he has passion and grip!—

Demand that they give us back NELSON's old Ship!

British hands from protecting her who shall debar?

Ne'er ingratitude lurked in the heart of a Tar.

"(Sings DIBDIN) That Ship from the breakers to save"

Is the plainest of duties e'er put on the brave.

While a rag, or a timber, or spar, she can boast,

A place of prime honour on Albion's coast

Should be hers and the Victory's! Let us not say,

Like the fish-hucksters, "Memories are cheap, Sir, to-day!"

ECCLESIASTICAL TASTE.—A condiment not much in favour with High Churchmen just now, must be "Worcester Sauce." It is warranted to neutralise the very highest flavour.

Of "garnered leaves"

And "garnered sheaves"

Sing sentimental donkeys.

Perhaps e'er long

Their simple song

Will be of Garnered Monkeys!

"A railway from Joppa to Jerusalem" sounds like a Scriptural Line. In future, "going to Jericho" will not imply social banishment, as the party sent thither will be able to take a return-ticket.

Cheery Official. "ALL FIRST CLASS 'ERE, PLEASE?"

Degenerate Son of the Vikings (in a feeble voice). "FIRST CLASS? NOW DO I LOOK IT?"

My name and style are ELLIS ASHMEAD BART—

Ah! happy augury. Would I could

Leave it so. But 'twill not do.

Like soap of Monkey brand,

It will not wash clothes,

Or, in truth, ought else.

'Tis but an accident of rhythm

Born of the imperative mood that makes one

Start a poem of this kind on ten feet,

Howe'er it may thereafter crawl or soar.

What I really was about to remark was that

My name and style are ELLIS ASHMEAD BART-

LETT, Knight; late Civil Lord of Admiralty

You know me. I come from Sheffield; at least

I did on my return thence

Upon re-election.

A sad world this, my masters, as someone—

Was it my friend SHAKSPEARE?—

Says. The sadness arises upon reflection, not

That I'm a Knight, but that I am, so to speak,

A Knight of only two letters.

As thus—Kt. 'Tis but a glimmer of a night,

If I, though sore at heart, may dally with

The English tongue

And make a pensive pun.

Of course I expected different things from

The MARKISS.

What's the use, what's the purpose,

Of what avail, wherefore,

That a man should descend from the

Spacious times of ELIZABETH with nothing

In his hand other than a simple Knighthood?

Anyone could do that.

It might be done to anyone.

He, him, all, any, both, certain, few,

Many, much, none, one, other, another.

One another, several, some, such and whole.

Why, he made a Knight

At the same time,

In the same manner,

Of

MAPLE

BLUNDELL!

Look here, MARKISS, you know,

This won't do.

It may pass in a crowd, but not with

ELLIS ASHMEAD BART—

(There it is again. Evidently doesn't matter

About the feet)

LETT.

And yet MARKISS, mine,

I shall not despair.

You are somewhat out of it

At the present moment.

And I am not sure—

Not gorged with certainty—

That Mr. G. would be

Inclined to make amends.

He is old; he is agëd.

Prejudice lurks amid

His scant white locks,

And forbids the stretch-

Ing forth of generous hand in whose

Recesses coyly glint

The Bart. or K.C.B.

But you are not everyone;

Nor is he. Nor do both together

In the aggregate

Compose the great globe

And all that therein is.

I'll wait awhile, possessing my soul in

Patience.

Everything comes to the man who waits.

(Sometimes, 'tis true, 'tis the bobby

Who asks what he's loafing there for,

And bids him

Move on.

That is a chance the brave resolute soul

Faces.) The pity of it is

That you, MARKISS, having so much to give,

So little gave

To

Me.

Oh, MARKISS! MARKISS!

Had I but served my GLADSTONE

As I have served thee,

He would not have forsak—

But that's another story.

THE NEW HOPERA OF 'ADDON 'ALL.—The title finally decided upon for the SULLIVAN-GRUNDY Opera is Haddon Hall. Lovely for 'ARRY! "'Ave you seen 'Addon 'All?" Then the 'ARRY who 'as only 'eard a portion of it, will say, "I 'addn't 'eard 'all." As a Cockney title, it's perfect. Successful or not, Author and Composer will congratulate themselves that, to deserve, if not command success, they 'ad don all they knew. If successful, they'll replace the aspirates, and it will be some time before they recover the exact date when they Had-don Hauling in the coin. Prosit!

MISCARRIAGE OF JUSTICE.—Says the Pall Mall Gazette:—"For knocking over a man selling watercress, with fatal results, a Hammersmith cabman has been committed for trial for manslaughter." If this is true, the HOME SECRETARY should immediately interpose. The action of knocking a man over is hasty, and may be indefensible. But if the Hammersmith Cabman had just grounds for belief that the man was "selling watercresses with fatal results," he should rather be commended than committed for trial.

"KEEPING-UP THE CHRISTOPHER."—(A Note from an Old Friend).—"CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS" indeed! As years ago I told Sairey Gamp about her bothering Mrs. Harris, "I don't believe there's no sich a person." That's what I says, says I, about COLUMBUS, wich ain't like any other sort of "bus" as I see before my blessed eyes every day.

P.S.—Mr. EDWIN JOHNSON, him as wrote to the Times last Saturday, is of my opinion. Good Old JOHNSON!

"HONORIS CAUSÂ."—To Mr. GRANVILLE MONEY, son of the Rector of Weybridge, whose gallant rescue of a lady from drowning has recently been recorded, Mr. Punch grants the style and title of "Ready MONEY."

QUESTION AND ANSWER.—"Why don't I write Plays?" Why should I?

Not long ago I reminded you of CHEPSTOWE, the incomparable poet who was at one time supposed to have revolutionised the art of verse. Now he is forgotten, the rushlight which he never attempted to hide under the semblance of a bushel, has long since nickered its last, his boasts, his swelling literary port, his quarrels, his affectations—over all of them the dark waves of oblivion have passed and blotted them from the sand on which he had traced them. But in his day, as you remember, while yet he held his head high and strutted in his panoply, he was a man of no small consequence. Quite an army of satellites moved with him, and did his bidding. To one of them he would say, "Praise me this author," and straightway the fire of eulogy would begin. To another he would declare—and this was his more frequent course—"So-and-so has dared to hint a fault in one of us; he has hesitated an offensive dislike. Let him be scarified," and forthwith the painted and feathered young braves drew forth their axes and scalping-knives, and the work of slaughter went merrily forward. Youth, modesty, honest effort, genuine merit, a manifest desire to range apart from the loud storms of literary controversy, these were no protection to the selected victim. And of course the operations of the Chepstowe-ites, like the "plucking" imagined by Major Pendennis, were done in public. For they had their organ. Week by week in The Metropolitan Messenger they disburdened themselves, each one of his little load of spite and insolence and vanity, and with much loud shouting and blare of adulatory trumpets called the attention of the public to their heap of purchasable rubbish. There lived at this time a great writer, whose name and fame are still revered by all who love strong, nervous English, vivid description, and consummate literary art. He stood too high for attack. Only in one way could the herd of passionate prigs who waited on CHEPSTOWE do him an injury. They could attempt, and did, to imitate his style in their own weekly scribblings. Corruptio optimi pessima. There is no other phrase that describes so well the result of these imitative efforts. All the little tricks of the great man's humour were reproduced and defaced, the clear stream of his sentences was diverted into muddy channels, the airy creatures of his imagination were weighted with lead and made to perform hideous antics. Never had there been so riotous a jargon of distorted affectation and ponderous balderdash. Smartness—of a sort—these gentlemen, no doubt, possessed. It is easy to be accounted smart in a certain circle, if only you succeed in being insolent. Merit of this order the band could boast of plenteously.

One peculiarity, too, must be noted in The Metropolitan Messenger. It had a magnetic attraction for all the sour and sorry failures whose reputation and income, however greatly in excess of their deserts, had not equalled their expectation. The Cave of Adullam could not have been more abundantly stocked with discontent. It is the custom of the ratés everywhere to attempt to prevent, or, if that be impossible, to decry success in others, in order to exalt themselves. The "Metropolitans" followed the example of many unillustrious predecessors, though it must, in justice, be added, that they would have been shocked to hear anyone impute to them a want of originality in their curious methods. In the counsels of these literary bravos, WILLIAM GRUBLET held a high place. At the University, where he had pursued a dull and dingy career of modified respectability, not much was thought or spoken of GRUBLET. If he was asked what profession he proposed to adopt, he would wink knowingly, and reply, "Journalism." It sounded well—it gave an impression of influence, and future power, and, moreover, it committed him to nothing. It is just as easy to say "Journalism," in answer to the stock question, as it is to deliver yourself over, by anticipation, to the Bar, the Church, or the Stock Exchange. Hundreds of young men at both our ancient Universities look upon Journalism as the easiest and most attractive of all the professions. In the first place there are no Examinations to bar the way, and your ordinary Undergraduate loathes an Examination as a rat may be supposed to loathe a terrier. What can be easier—in imagination—than to dash off a leading article, a biting society sketch, a scathing review, to overturn ancient idols, to inaugurate movements, to plan out policies? All this GRUBLET was confident of being able to do, and he determined, on the strength of a few successful College Essays, and a reputation for smartness, acquired at the expense of his dwindling circle of intimates, to do it. He took his degree, and plunged into London. There, for a time, he was lost to public sight. But I know that he went through the usual contest. Rejected manuscripts poured back into his room. Polite, but unaccommodating Editors, found that they had no use for vapid imitations of ADDISON, or feeble parodies of CHARLES LAMB. Literary appreciations, that were to have sent the ball of fame spinning up the hill of criticism, grew frowsy and dog's-eared with many postages to and fro.

In this protracted struggle with fate and his own incompetence, the nature of GRUBLET, never a very amiable one, became fatally soured, and when he finally managed to secure a humble post on a newspaper, he was a disappointed man with rage in his heart against his successful rivals and against the Editors who, as he thought, had maliciously chilled his glowing aspirations. His vanity, however,—and he was always a very vain man—had suffered no diminution, and with the first balmy breezes of success his arrogance grew unbounded. Shortly afterwards, he chanced to come in the way of CHEPSTOWE; he impressed the poet favourably, and in the result he was selected for a place on the staff of The Metropolitan Messenger, then striving by every known method to battle its way into a circulation.

It was at this stage in his career that I met GRUBLET. He was pointed out to me as a young man of promise who had a trenchant style, and had lately written an article on "Provincialism in Literature," which had caused some stir by its bitter and uncompromising attacks upon certain well-known authors and journalists. I looked at the man with some interest. I saw a pale-faced, sandy-haired little creature with a shuffling, weak-kneed gait, who looked as if a touch from a moderately vigorous arm would have swept him altogether out of existence. His manner was affected and unpleasant, his conversation the most disagreeable I ever listened to. He was coarse, not with an ordinary coarseness, but with a kind of stale, fly-blown coarseness as of the viands in the window of a cheap restaurant. He assumed a great reverence for RABELAIS and ARISTOPHANES; he told shady stories, void of point and humour, which you were to suppose were modelled on the style of these two masters. And all the time he gave you to understand, with a blatant self-sufficiency, that he himself was one of the greatest and most formidable beings in existence. This was GRUBLET as I first knew him, and so he continued to the end.

The one thing this puny creature could never forgive was that any of his friends should pass him in the race. There was one whom GRUBLET—the older of the two—had at one time honoured with his patronage and approval. No sooner, however, had the younger gained a literary success, than the sour GRUBLET turned upon him, and rent him. "This fellow," said GRUBLET, "will get too uppish—I must show up his trash"; and accordingly he fulminated against his friend in the organ that he had by that time come to consider as his own. This baseless sense of proprietorship, in fact, it was that wrecked GRUBLET. In an evil moment for himself he tried to ride rough-shod over CHEPSTOWE, and that temporary genius dismissed him with a promptitude that should stand to his credit against many shortcomings. GRUBLET, I believe, still exists. Occasionally, in obscure prints, I seem to detect traces of his style. But no one now pays any attention to him. His claws are clipped, his teeth have been filed down. He shouts and struts, unregarded. For we live, of course, in milder and more reasonable days, and the GRUBLETS can no longer find a popular market for their wares.

Only one question remains. How in the world can even you, oh respected SWAGGER, have derived any pleasure from witnessing the performances that GRUBLET went through, after you had persuaded him that he was a man of some importance? I do not expect an answer, and remain as before,

IN BANCO.—The stability of the concern having been effectually proved by the way in which the Birkbeckers got out of the fire and out of the trying pan-ic, and the ease with which they were quite at home to the crowds of callers coming to inquire after their health, should earn for them the subsidiary title of the Birk-beck-and-call Bank.

Uncle Jack (Umpire). "LOVE ALL!"

Monsieur le Baron. "LOVE ALL? PARBLEU! JE CROIS BIEN! ZEY ARE ADORABLES, YOUR NIECES!"

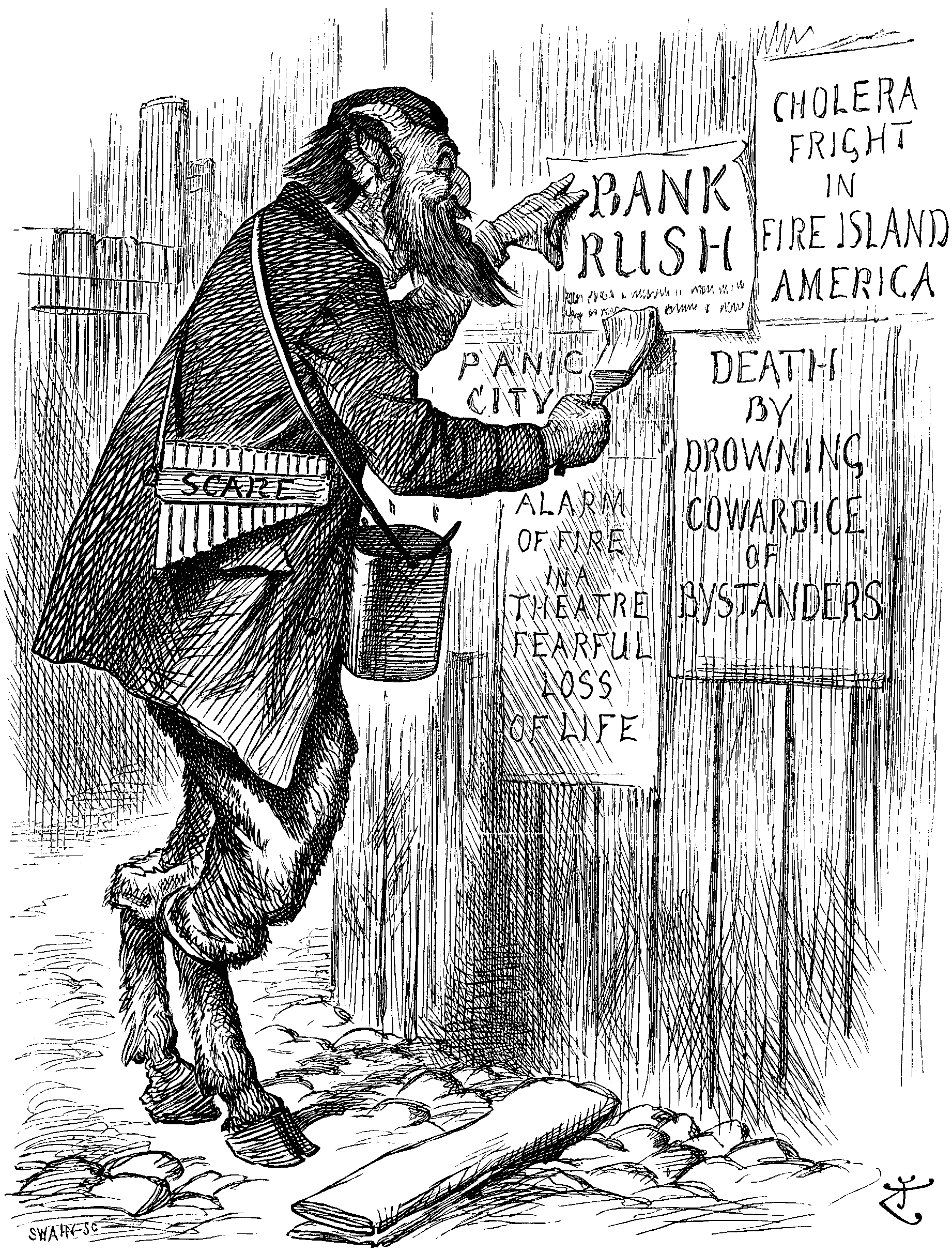

["We are presented just now with two spectacles, which may help us to take modest and diffident views of the progress of the species.... At home there is an utterly unreasonable and unaccountable financial panic among the depositors in the Birkbeck Bank, while in America the free and enlightened democracy of a portion of New York State has suddenly relapsed into primitive barbarism under the influence of fear of cholera."—The Times.]

What is he doing, our new god Pan,

Far from the reeds and the river?

Spreading mischief and scattering ban,

Screening 'neath "knickers" his shanks of a goat,

And setting the wildest rumours afloat,

To set the fool-mob a-shiver.

He frightened the shepherds, the old god Pan,1

Him of the reeds by the river;

Afeared of his faun-face, Arcadians ran;

Unsoothed by the pipes he so deftly could play,

The shepherds and travellers scurried away

From his face by forest or river.

And back to us, sure, comes the great god Pan,

With his pipes from the reeds by the river;

Starting a scare, as the goat-god can,

Making a Man a mere wind-swayed reed,

And moving the mob like a leaf indeed

By a chill wind set a-quiver.

He finds it sport, does our new god Pan

(As did he of the reeds by the river),

To take all the pith from the heart of a man,

To make him a sheep—though a tiger in spring,—

A cruel, remorseless, poor, cowardly thing,

With the whitest of cheeks—and liver!

"Who said I was dead?" laughs the new god Pan

(Laughs till his faun-cheeks quiver),

"I'm still at my work, on a new-fangled plan.

Scare is my business; I think I succeed,

When the Mob at my minstrelsy shakes like a reed,

And I mock, as the pale fools shiver."

Shrill, shrill, shrill, O Pan!

Your Panic-pipes, far from the river!

Deafening shrill, O Poster-Pan!

Turning a man to a timorous brute

With irrational fear. From your frantic flute

Good sense our souls deliver!

Men rush like the Gadaree swine, O Pan!

With contagious fear a-shiver,

They flock like Panurge's poor sheep, O Pan!

What, what shall the merest of manhood quicken

In geese gregarious, panic-stricken

Like frighted fish in the river.

You sneer at the shame of them, Poster-Pan,

Poltroons of the pigeon-liver.

Your placards gibbet them, Poster-Pan,

Who crowd like curs in the cowardly crush,

Who flock like sheep in the brainless rush

With fear or greed a-shiver.

You are half a beast, O new god Pan!

To laugh (as you laughed by the river)

Making a brute-beast out of a man:

The true gods sigh for the cost and pain

Of Civilisation, which seems but vain

When the prey of your Panic shiver!

Footnote 1: (return)Pan, the Arcadian forest and river-god, was held to startle travellers by his sudden and terror-striking appearances. Hence sudden fright, without any visible cause, was ascribed to Pan, and called a Panic fear.

[Sir GEORGE TREVELYAN, speaking to the Institute of Journalists, said that "No one was under the obligation of writing books, unless he was absolutely called to do so by a commanding genius."]

Oh! tell me quickly—not if Planet Mars

Is quite the best for journalistic pars,

Not if the cholera will play Old Harry,

Not why to-day young men don't and won't marry—

For these I do not care. Not to dissemble,

My pen is, as they say, "all of a tremble"—

The pen that once enthralled the myriad crowd,

The pen that critics one and all allowed

Wrote pleasantly and well, was often funny,

The pen that brought renown, and—better—money.

My pen is stilled. That happy time is o'er,

Like that old English King, I smile no more.

Now that Sir (Secretary) GEORGE has spoken,

My fortunes (and alas! my heart) are broken;

For though I may not lack all understanding,

My "genius" cannot claim to be "commanding."

FLOWERY, BUT NOT MEALY-MOUTHED.—To those who suggested that sending troops to compel the barbarous Long-Islanders to be humane would lose Democratic votes, Governor FLOWER is reported to have replied,—"I don't care a —— for votes. I am going to put law-breakers down, and the State in possession of its property." There was an old song, of which the refrain was, "I don't care a —— for the people, But what will the Governor say?" Now we know what the Governor says. 'Tis well said. Henceforth he will be known as The FLOWER of Speech.

That we hurry out of Town

To the sea,

To be properly done brown,

I'll agree;

But of being nicely done,

There's another way than one—

Viz., the rays, besides of sun,

£ s. d.!

Now, it may be very cheap

For the chap

Who is rich, to pay a heap

For a nap

On a sofa that is prone

To a prominence of bone,

Or a table undergrown,

With a flap;

But a man who has not much

Of the pelf

To distribute freely, such

As myself,

And who's ordered change and rest,

Doubts the change is for the best

When he has to lie undress'd

On a shelf!

No; to slumber on a slant

Till you're floor'd,

Is a luxury I can't

Well afford;

And I'm sad to a degree

That, in Everywhere-on-Sea,

"Board and Residence" should be

Mostly board!

"DISCOVERY OF A NEW SATELLITE TO JUPITER."—Well, why not? Why announce it as if a noted thief had been arrested? "Discovered! Aha! Then this to decide"—cries the Melodramatic Satellite. Poor Jupiter must be uncommonly tired of his old Satellites by this time! How pleased, how delighted, he must be to welcome a new one!

When anyone now in town requires a change from the De-lights of Home, let him go to See Lights of Home at the Adelphi. Great scene of the Wreck not so great perhaps as some previous sensational Adelphi effects. In such a piece as "the Lights," it is scarcely fair that "the Heavies" should have it nearly all to themselves, but so it is, and the two Light Comedy parts capitally played by Miss JECKS and Mr. LIONEL RIGNOLD, do not get much of a chance against the heartrending sorrows of Miss EVELYN MILLARD, and of Mrs. PATRICK CAMPBELL, the slighted, or sea-lighted heroine, known as "Dave's Daughter" (oh, how fond Mr. W.A. ELLIOTT must be of Dave Purvis, the weakest sentimentalist-accidental-lunatic-criminal that ever was let off scot-free at R.H. first entrance before the fall of the Curtain), and the undaunted heroism and unblushing villany of Messrs. CHARLES DALTON, COCKBUKN, KINGSTON & Co. The title might well have been, Good Lights of Home, and Wicked Livers all Abroad.

"TOP-DRESSING."—Said Mr. G. to a Welsh audience, "I might as well address the top of Snowdon on the subject of the Establishment, as address you on the matter." Flattery! The top of Snowdon, of course, represented the highest intelligence in Wales.

"I pity the poor Investors!" exclaimed Mrs. R. sympathetically, when she saw the heading of a paragraph in the Times—"Bursting of a Canal Bank."

A BIG BOOMING CHANCE LOST!—Miss LOTTIE COLLINS, according to the Standard's report of the proceedings on board the unfortunate Cepheus, said that, on seeing two jeering men rowing out from shore, holding up bread to the hungry passengers, she, "had she been a man, would have shot them." She wasn't a man, and so the two brutes escaped. But what another "Boom! te-ray,—Ta, ra, ra," &c., &c., this would have been for LA COLLINS!

NOT IMPROBABLE.—Lord ROSEBERY might have ended his diplomatic reply to Mr. THOMAS GIBSON BOWLES, M.F., who recently sent kind inquiries to the Foreign Office, as to the Pamirs and Behring Sea, Canadian Government, &c., &c., with a P.S. to the effect that "his correspondent probably considered him as a Jack (in office), and therefore a legitimate object to score off in the game of BOWLES."

The Prodigal Daughter; or, The Boyne-Water Jump, by DRURIOLANUS MAGNUS and PETTITT PARVUS, was produced with greatest success, last Saturday, at Old Drury. The general recommendation to the authors will be, as a matter of course, i.e., of race-course, given in the historic words of DUCROW, "Cut the cackle and come to the 'osses." When this advice is acted upon, The Prodigal Daughter, a very fine young woman, but not particularly prodigal, will produce receipts beyond all cacklelation.

FUTURE LEGISLATION FOR NEXT SESSION.—Mr. GLADSTONE will introduce a Bill to render criminal the keeping of heifers loose in a field.

BY A PARAGRAPHIC JOURNALIST.—Very natural that there should be "pars" about "Mars."

"SIGNAL FAILURES."—Most Railway Accidents.

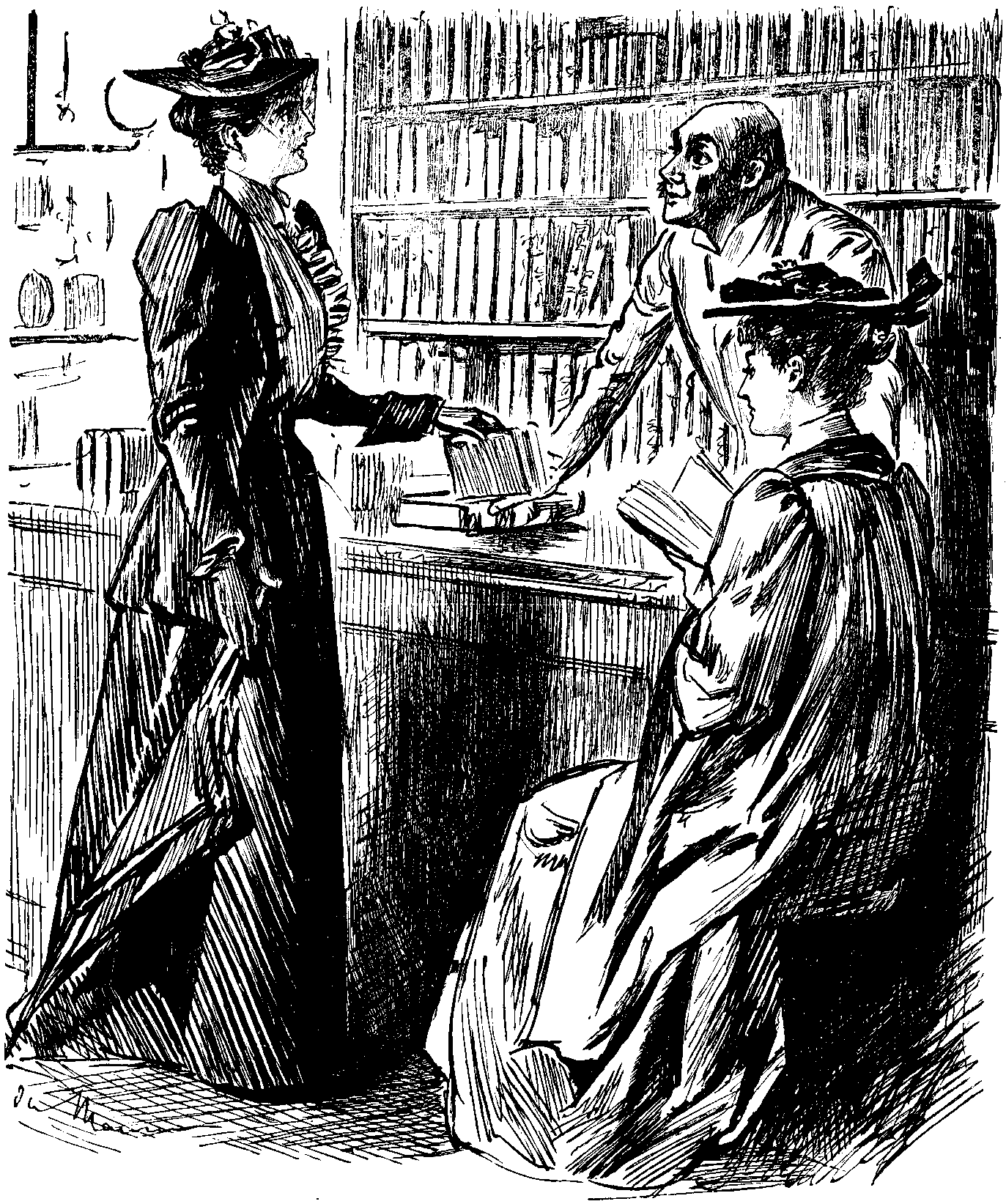

"HAVE YOU BROWNING'S WORKS?"

"NO, MISS. THEY'RE TOO DIFFICULT. PEOPLE DOWN HERE DON'T UNDERSTAND THEM."

"HAVE YOU PRAED?"

"PRAYED, MISS? OH YES; WE'VE TRIED THAT, BUT IT'S NO USE!"

The Castle that I sing, is not

The strong-hold près Marseilles,

Where Monte Christo brewed his plot

For DUMAS' magic tale:

It's one we all inhabit oft,

The residence of most,

And not peculiar to the soft,

Mediterranean coast.

The Castle "If"—If pigs had wings,

If wishes horses were,

If, rather more substantial things,

My Castles in the air;

If balances but grew on Banks,

If Brokers hated "bluff;"

If Editors refrained from thanks

And printed all my stuff.

If holidays were not a time

Beyond a chap's control,

When someone else prescribes how I'm

To bore my selfish soul;

If bags and boxes packed themselves

For one who packing loathes;

If babes, expensive little elves,

Were only born with clothes

If Bradshaw drove me to the train!

Were mal-de-mer a name!

If organ-grinders ground a strain

That never, never came;

If oysters stuck at eighteen pence;

If ladies loathed "The Stores;"

If Tax-collectors had the sense

To overlook my doors!

If sermons stopped themselves to suit

A congregation's pain;

If everyone who played the flute

Were sentenced to be slain;

If larks with truffles sang on trees,

If cooks were made in heaven;

And if, at sea-side spots, the seas

Shut up from nine till seven.

If I might photograph the fiend

Who mauls me with his lens,

If supercilious barbers leaned

Their heads for me to cleanse!

If weather blushed to wreck my plans,

If tops were never twirled;

If "Ifs and ands were pots and pans,"—

'Twould be a pleasant world!

SUMMARY OF RESULT FOR OLD CATHOLIC CONGRESS.—Lucernâ Lucellum.

DEAR MR. PUNCH,—I got so wet on the St. Leger day, that I've been in bed ever since—not because I had to wait till my things were dry—but because I caught a cold! What a day it was!—I am told that in addition to the St. Leger, Doncaster is chiefly celebrated for Butter Scotch—if so, I presume they don't make it out-of-doors, or it would have stood a good chance of being melted—(not in the mouth)—on Wednesday fortnight! But the excitement of the race fully made up for the liquid weather, and we all—(except the backers of Orme)—enjoyed ourselves. I was told that the Duke of WESTMINSTER had "left the Leger at Goodwood," which is simply absurd, as I not only saw it run for at Doncaster myself, but it is ridiculous to insinuate that the Duke went there, put the Leger in his pocket—(as if a Nobleman ever kept books)—walked off quietly to Goodwood and left it there deliberately!

I conclude it can only be an expression coined to discount—(another ledger term)—the victory of La Flèche,—to which not half enough attention has been drawn, solely (in my opinion) because La Flèche is of the gentler sex, and men don't like the "horse of the year" to be a mare.

I still maintain she was unlucky to lose the Derby, as she won the Oaks two days later in two seconds quicker time:—(which is an anachronism—as if you win once out of twice—how can it be two seconds?)

There was good sport at Yarmouth last week, though owing to the rain the course must have been on the soft (roe) side,—by the way you can get them now in bottles, and very good they are. I am glad to see that staunch supporter of the turf, Lord ELTHAM, winning races again—as his horses have been much out of form lately, at least so I am told, but I was not aware that horses were in a "form" at all, unless being "schooled" over hurdles.

I shall have a word or two to say on the Cesarewitch shortly—having had some private information calculated to break a ROTHSCHILD if followed—but for the moment will content myself with scanning the programme of the Leicester and Manchester Meetings.

There are two races which seem perhaps worth picking up—one at each place; and, while giving my selection for the Leicestershire race in the usual verse, I will just mention that I should have given Lord DUNRAVEN's Inverness for the Manchester race, but that I see his Lordship has sent it to America—rather foolish, now that winter is coming on; but perhaps he has another, and may be doing a kindness to some poor American Cousin! St. Angelo might win this race without an Inverness, though I presume he will appear in some sort of clothing.

On seeing an awkward, three-cornered affair,

Which I heard was a racer from Fingal,

And hearing him roaring, and whistling an air,

I said, he'll be beaten by Windgall.

P.S.—This is awful; but what a horse to have to rhyme to!

"SHUT UP!" AT BARMOUTH!—Mr. GLADSTONE having made up his mind not to utter another syllable during his holiday, selects as an appropriate resting-place, a charming sea-side spot where he stops himself, and where there is a "Bar" before the "mouth."

Dear MR. PUNCH,—So much is done by the organisers of the Primrose League in the shape of amusements for the people, that it seems strange "the other side" should not follow suit. Without having decided political opinions, I like both the Government and Her Majesty's Opposition to be on equal terms. Hence my suggestion. I see that, a few days ago, Mr. GLADSTONE, in speaking to an audience at Barmouth, made the following remarks. He said—He belonged to almost every part of the country. A Scotchman by blood, born in Lancashire, and resident in London, he had become closely attached to Wales by marriage, and had now become too old to get rid of that inclination. Surely these admissions conjure up the possibility of a really excellent entertainment. To show you what I mean, I jot down, in dramatic form, my notion of the manner in which the PREMIER's excellent idea should be worked out:—

SCENE—A large hall, with a platform. On the platform, Committee and Chairman. In front of the Chairman, large table, with cloth reaching to the floor. Water-bottle, and tumbler, and lamp.

Chairman. Ladies and Gentlemen, I have great pleasure in announcing that the Right Hon. W.E. GLADSTONE (cheers), will give his entertainment entitled "The Man of Many Characters" almost immediately. The PREMIER's train is a little late, but—ah, here come his fore-runners. (Enter two Servants in livery with a large basket-box, which they place under the table and then retire.) And now we may expect the PREMIER immediately.

[Enter Mr. GLADSTONE in evening dress hurriedly. He is received with thunders of applause.

Mr. Gladstone. Ladies and Gentlemen! (Great cheering.) I regret I have kept you waiting for some quarter of an hour. My excuse must be that I caused the train to be pulled up, because I noticed at a wayside station a crowd of villagers who, apparently, were desirous to hear me speak. You must forgive me, for it was for the good of the nation. (Cheers.) And now without preface, I will appear as my friend Farmer HODGE. (Loud applause, during which the PREMIER dives under the table and re-appears in character. Continued applause.) I be mighty glad to see ye. And now, I'll tell ye what I thinks about the Eight Hours' Bill. (Airs his opinions in "Zomerzetshire" for some twenty minutes. At the conclusion of his performance re-appears in evening dress-coat. Applause.) Thank you very much. But although Farmer HODGE is a very good fellow, I think SANDIE MACBAWBEE is even better. With your permission, I will appear as SANDIE MACBAWBEE. (Disappears under table, and re-appears in Highland Costume. Cheers.) Dinna fash yourselves! Ma gracious! It's ma opinion that you'll just hear a wee bit about Home Rule for Bonnie Scotland. Well, ye ken—(Airs his opinions upon his chosen subject in broad Scotch. After a quarter of an hour he re-appears, and receives the usual applause.) Thank you from the bottom of my heart. And now as I have shown you Scotland and England, I think you would be pleased with a glimpse of London. (Cheers.) You all like London, do you not? (Applause.) With your kind permission, I will re-appear as a noted character in the great tragic comedy of the world's Metropolis. (Dives down and comes up as a Costermonger. Prolonged applause.) What cheer! (Laughter.) Well, you blokes what are you grinning at? I am a chickaleary cove, that's what I am. But I know what would knock you! You would like to 'ear about 'Ome Rule. Eh? What cheer! 'Ere goes. (Reveals his Home-Rule scheme with a Cockney twang and dialect. Then disappears and re-appears in his customary evening dress.) Thank you most earnestly. (Loud cheers.) And now I am afraid I must bid you good-bye. But before leaving, I must confess to you that I have never had the honour of appearing before a juster, more intelligent, and more appreciative audience. [Bows and exit.

Voices. Encore! Encore! Encore!

Mr. Gladstone (returning). I am deeply touched by this sign of public confidence. I would willingly continue my character illustrations indefinitely, but, unfortunately, I am required in another part of the country to repeat the same performances. I have only just time to catch my special train. Thank you again and again.

[Exit hurriedly, after kissing his hand. The Footmen reappear, and take away the large box. Applause, and Curtain.

There, my dear Mr. Punch, is the rough idea. I feel sure it could be carried through with the greatest possible advantage.

It was a gorgeous entertainment, consisting chiefly of recitations and the "Intermezzo." Lady VIOLET MALVERN was the life and soul of the party. But there were lesser lights in a Baron FINOT, an old diplomatist, and a Major GARRETT, an officer in retreat. Then came ARMAND SEVARRO. He was an adventurer, and a friend of Baron FINOT, and had a solitary anecdote.

"I am going to be married to a young lady of the name of DOROTHY BLAIR, but cannot reveal the secret, because her mother is not well enough to hear the news."

Then ARMAND met Lady VIOLET.

"I dreamed years ago of going to the City of Manoa to find its queen. I have found her this evening."

"And she is—?" queried Lady VIOLET.

"You!" hissed the Brazilian (he was a Brazilian), and departed.

"What folly!" murmured Lady VIOLET, in the moonlight.

And many agreed with her.

DOROTHY was on the Thames. There came to her ARMAND.

"Will you never publish our contemplated marriage?" she asked.

"How can I, child?" he replied. "How can I reveal the secret when your mother is not well enough to hear the news?"

It was his solitary anecdote.

She sighed, and then came a steam-launch. It contained Lady VIOLET, the other characters, lunch, and (played off) the "Intermezzo."

Then ARMAND preferred to flirt with Lady VIOLET to DOROTHY.

"What nonsense!" thought DOROTHY.

And her thoughts found an echo in the breasts of the audience.

And the Right Hon. RICHARD MALVERN, having had supper, was jealous of his wife. He told Lady VIOLET that he considered ARMAND de trop. But he did it so amiably that it touched Lady VIOLET deeply.

"I will send ARMAND away," she replied. Then she told the Brazilian that it was his duty to stay away until his engagement was announced.

"But how can it be announced?" he replied, repeating his solitary anecdote. "I am engaged to a young lady, but I cannot reveal the secret, because her mother is not well enough to hear the news."

Then Lady VIOLET bade him, haughtily, adieu! He departed, but returned, accompanied by the "Intermezzo." Then—probably at the suggestion of the music—she hugged him. Then he left her.

"This is very wearisome," murmured Lady VIOLET.

And the audience agreed with her.

It being moonlight, Lady VIOLET walked on a terrace, and admired a dangerous weir. There was a shriek, and the Brazilian rushed in accompanied by the "Intermezzo."

"Fly with me to any part of the Desert that pleases you most."

"I would be most delighted," replied Lady VIOLET; "I would sacrifice myself to any extent, but I would not annoy my husband."

"Then let me kiss you with the aid of MASCAGNI," and he pressed his lips to her brow, to the accompaniment of the "Intermezzo."

"I have been to Manoa, and kissed its Queen," said the Brazilian, as he jumped into the weir, wearily. "It would have been better had I died before."

"Yes," thought Lady VIOLET, as she leisurely fainted, "it would indeed have been better had he died in the First Act than in the last. Then the piece would have been shorter, more satisfactory, and less expensive to produce. Nay, more—a solitary Act might have been one too many!" And yet again the audience, "all o'er-bored," entirely agreed with her!

☞ NOTICE.—Rejected Communications or Contributions, whether MS., Printed Matter, Drawings, or Pictures of any description, will in no case be returned, not even when accompanied by a Stamped and Addressed Envelope, Cover, or Wrapper. To this rule there will be no exception.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, Or The London Charivari, Vol.

103, Sep. 24, 1892, by Various

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH ***

***** This file should be named 15366-h.htm or 15366-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

https://www.gutenberg.org/1/5/3/6/15366/

Produced by Malcolm Farmer, William Flis, and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team.

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

https://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH F3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need, is critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation web page at https://www.pglaf.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Its 501(c)(3) letter is posted at

https://pglaf.org/fundraising. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at

809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email

business@pglaf.org. Email contact links and up to date contact

information can be found at the Foundation's web site and official

page at https://pglaf.org

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit https://pglaf.org

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including including checks, online payments and credit card

donations. To donate, please visit: https://pglaf.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For thirty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

https://www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.