The Project Gutenberg eBook, Poems, by William Ernest Henley This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Poems Author: William Ernest Henley Release Date: February 27, 2015 [eBook #1568] [This file was first posted on August 23, 1998] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-646-US (US-ASCII) ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK POEMS***

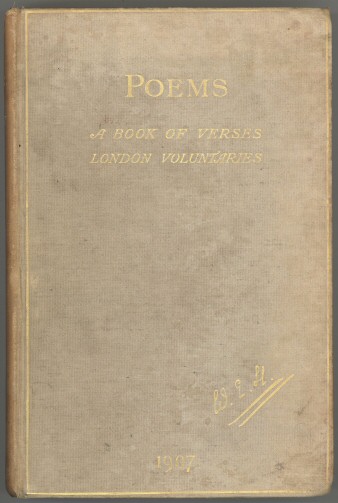

Transcribed from the 1907 David Nutt edition by Diarmuid Pigott with some additional material and proofing by David Price, email ccx074@pglaf.org

By

WILLIAM ERNEST HENLEY

The summer’s flower is to the summer sweet,

Though to itself it only live and die.SHAKESPEARE

Tenth Impression

LONDON

Published by DAVID NUTT

at the Sign of the Phœnix

in Long Acre

1907

1898 |

|

Second Edition printed March |

1898 |

Third Edition printed September |

1898 |

Fourth Edition printed January |

1900 |

Fifth Edition printed December |

1901 |

Sixth Impression printed August |

1903 |

Seventh Impression printed February |

1904 |

Eighth Impression printed May |

1905 |

Ninth Impresion printed April |

1906 |

Tenth Impression printed Nov. |

1907 |

Edinburgh: T. and A. Constable, Printers to His Majesty

Take, dear, my little sheaf of

songs,

For, old or new,

All that is good in them belongs

Only to you;

And, singing as when all was

young,

They will recall

Those others, lived but left unsung—

The bent of all.

W. E. H

April 1888

September 1897.

My friend and publisher, Mr. Alfred Nutt, asks me to introduce this re-issue of old work in a new shape. At his request, then, I have to say that nearly all the numbers contained in the present volume are reprinted from ‘A Book of Verses’ (1888) and ‘London Voluntaries’ (1892–3). From the first of these I have removed some copies of verse which seemed to me scarce worth keeping; and I have recovered for it certain others from those publications which had made room for them. I have corrected where I could, added such dates as I might, and, by re-arrangement and revision, done my best to give my book, such as it is, its final form. If any be displeased by the result, I can but submit that my verses are my own, and that this is how I would have them read.

The work of revision has reminded me that, small as is this book of mine, it is all in the matter of verse that I have to show for the years between 1872 and 1897. A principal reason is that, after spending the better part of my life in the pursuit of poetry, I found myself (about 1877) so utterly unmarketable that I had to own myself beaten in art, and to addict myself to journalism for the next ten years. Came the production by my old friend, Mr. H. B. Donkin, in his little collection of ‘Voluntaries’ (1888), compiled for that East-End Hospital to which he has devoted so much time and energy and skill, of those unrhyming rhythms in which I had tried to quintessentialize, as (I believe) one scarce can do in rhyme, my impressions of the Old Edinburgh Infirmary. They had long p. viiisince been rejected by every editor of standing in London—I had well-nigh said in the world; but as soon as Mr. Nutt had read them, he entreated me to look for more. I did as I was told; old dusty sheaves were dragged to light; the work of selection and correction was begun; I burned much; I found that, after all, the lyrical instinct had slept—not died; I ventured (in brief) ‘A Book of Verses.’ It was received with so much interest that I took heart once more, and wrote the numbers presently reprinted from ‘The National Observer’ in the collection first (1892) called ‘The Song of the Sword’ and afterwards (1893), ‘London voluntaries.’ If I have said nothing since, it is that I have nothing to say which is not, as yet, too personal—too personal and too a afflicting—for utterance.

For the matter of my book, it is there to speak for itself:—

‘Here’s a sigh to those who love me

And a smile to those who hate.’

I refer to it for the simple pleasure of reflecting that it has made me many friends and some enemies.

W. E. H.

Muswell Hill, 4th September 1897.

IN HOSPITAL |

||

|

PAGE |

|

I. |

Enter Patient |

|

II. |

Waiting |

|

III. |

Interior |

|

IV. |

Before |

|

V. |

Operation |

|

VI. |

After |

|

VII. |

Vigil |

|

VIII. |

Staff-Nurse: Old Style |

|

IX. |

Lady Probationer |

|

X. |

Staff-Nurse: New Style |

|

XI. |

Clinical |

|

XII. |

Etching |

|

XIII. |

Casualty |

|

XIV. |

Ave, Caeser! |

|

XV. |

‘The Chief’ |

|

XVI. |

House-Surgeon |

|

XVII. |

Interlude |

|

XVIII. |

Children: Private Ward |

|

XIX. |

Srcubber |

|

XX. |

Visitor |

|

XXI. |

Romance |

|

XXII. |

Pastoral |

|

XXIII. |

Music |

|

Suicide |

||

XXV. |

Apparition |

|

XXVI. |

Anterotics |

|

XXVII. |

Nocturn |

|

XXVIII. |

Discharged |

|

Envoy |

||

The Song of the Sword |

||

Arabian Nights’ Entertainments |

||

BRIC-À-BRAC |

||

Ballade of the Toyokuni Colour-Print |

||

Ballade of Youth and Age |

||

Ballade of Midsummer Days and Nights |

||

Ballade of Dead Actors |

||

Ballade Made in the Hot Weather |

||

Ballade of Truisms |

||

Double Ballade of Life and Death |

||

Double Ballade of the Nothingness of Things |

||

At Queensferry |

||

Orientale |

||

In Fisherrow |

||

Back-View |

||

Croquis |

||

Attadale, West Highlands |

||

From a Window in Princes Street |

||

In the Dials |

||

The gods are dead |

||

Let us be drunk |

||

When you are old |

||

Beside the idle summer sea |

||

We shall surely die |

||

What is to come |

||

ECHOES |

||

I. |

To my mother |

|

II. |

Life is bitter |

|

III. |

O, gather me the rose |

|

IV. |

Out of the night that covers me |

|

V. |

I am the Reaper |

|

VI. |

Praise the generous gods |

|

VII. |

Fill a glass with golden wine |

|

VIII. |

We’ll go no more a-roving |

|

IX. |

Madam Life’s a piece in bloom |

|

X. |

The sea is full of wandering foam |

|

XI. |

Thick is the darkness |

|

XII. |

To me at my fifth-floor window |

|

XIII. |

Bring her again, O western wind |

|

XIV. |

The wan sun westers, faint and slow |

|

XV. |

There is a wheel inside my head |

|

XVI. |

While the west is paling |

|

XVII. |

The sands are alive with sunshine |

|

XVIII. |

The nightingale has a lyre of gold |

|

XIX. |

Your heart has trembled to my tongue |

|

XX. |

The surges gushed and sounded |

|

XXI. |

We flash across the level |

|

XXII. |

The West a glimmering lake of light |

|

XXIII. |

The skies are strown with stars |

|

XXIV. |

The full sea rolls and thunders |

|

XXV. |

In the year that’s come and gone |

|

XXVI. |

In the placid summer midnight |

|

XXVII. |

She sauntered by the swinging seas |

|

Blithe dreams arise to greet us |

||

XXIX. |

A child |

|

XXX. |

Kate-A-Whimsies, John-a-Dreams |

|

XXXI. |

O, have you blessed, behind the stars |

|

XXXII. |

O, Falmouth is a fine town |

|

XXXIII. |

The ways are green |

|

XXXIV. |

Life in her creaking shoes |

|

XXXV. |

A late lark twitters from the quiet skies |

|

XXXVI. |

I gave my heart to a woman |

|

XXXVII. |

Or ever the knightly years were gone |

|

XXXVIII. |

On the way to Kew |

|

XXXIX. |

The past was goodly once |

|

XL. |

The spring, my dear |

|

XLI. |

The Spirit of Wine |

|

XLII. |

A Wink from Hesper |

|

XLIII. |

Friends. . . old friends |

|

XLIV. |

If it should come to be |

|

XLV. |

From the brake the Nightingale |

|

XLVI. |

In the waste hour |

|

XLVII. |

Crosses and troubles |

|

LONDON VOLUNTARIES |

||

I. |

Grave |

|

II. |

Andante con Moto |

|

III. |

Scherzando |

|

IV. |

Largo e Mesto |

|

V. |

Allegro Maëstoso |

|

RHYMES AND RHYTHMS |

||

Prologue |

||

I. |

Where forlorn sunsets flare and fade |

|

II. |

We are the Choice of the Will |

|

A desolate shore |

||

IV. |

It came with the threat of a waning moon |

|

V. |

Why, my heart, do we love her so? |

|

VI. |

One with the ruined sunset |

|

VII. |

There’s a regret |

|

VIII. |

Time and the Earth |

|

IX. |

As like the Woman as you can |

|

X. |

Midsummer midnight skies |

|

XI. |

Gulls in an aery morrice |

|

XII. |

Some starlit garden grey with dew |

|

XIII. |

Under a stagnant sky |

|

XIV. |

Fresh from his fastnesses |

|

XV. |

You played and sang a snatch of song |

|

XVI. |

Space and dread and the dark |

|

XVII. |

Tree, Old Tree of the Triple Crook |

|

XVIII. |

When you wake in your crib |

|

XIX. |

O, Time and Change |

|

XX. |

The shadow of Dawn |

|

XXI. |

When the wind storms by with a shout |

|

XXII. |

Trees and the menace of night |

|

XXIII. |

Here they trysted, here they strayed |

|

XXIV. |

Not to the staring Day |

|

XXV. |

What have I done for you |

|

Epilogue |

||

p. 2On ne saurait dire à quel point un homme, seul dans son

lit et malade, devient personnel.—Balzac.

The morning mists

still haunt the stony street;

The northern summer air is shrill and cold;

And lo, the Hospital, grey, quiet, old,

Where Life and Death like friendly chafferers meet.

Thro’ the loud spaciousness and draughty gloom

A small, strange child—so agèd yet so

young!—

Her little arm besplinted and beslung,

Precedes me gravely to the waiting-room.

I limp behind, my confidence all gone.

The grey-haired soldier-porter waves me on,

And on I crawl, and still my spirits fail:

A tragic meanness seems so to environ

These corridors and stairs of stone and iron,

Cold, naked, clean—half-workhouse and half-jail.

A square, squat room

(a cellar on promotion),

Drab to the soul, drab to the very daylight;

Plasters astray in unnatural-looking tinware;

Scissors and lint and apothecary’s jars.

Here, on a bench a skeleton would writhe

from,

Angry and sore, I wait to be admitted:

Wait till my heart is lead upon my stomach,

While at their ease two dressers do their

chores.

One has a probe—it feels to me a

crowbar.

A small boy sniffs and shudders after bluestone.

A poor old tramp explains his poor old ulcers.

Life is (I think) a blunder and a shame.

The gaunt brown walls

Look infinite in their decent meanness.

There is nothing of home in the noisy kettle,

The fulsome fire.

The

atmosphere

Suggests the trail of a ghostly druggist.

Dressings and lint on the long, lean table—

Whom are they for?

The

patients yawn,

Or lie as in training for shroud and coffin.

A nurse in the corridor scolds and wrangles.

It’s grim and strange.

Far

footfalls clank.

The bad burn waits with his head unbandaged.

My neighbour chokes in the clutch of chloral . . .

O, a gruesome world!

Behold me

waiting—waiting for the knife.

A little while, and at a leap I storm

The thick, sweet mystery of chloroform,

The drunken dark, the little death-in-life.

The gods are good to me: I have no wife,

No innocent child, to think of as I near

The fateful minute; nothing all-too dear

Unmans me for my bout of passive strife.

Yet am I tremulous and a trifle sick,

And, face to face with chance, I shrink a little:

My hopes are strong, my will is something weak.

Here comes the basket? Thank you. I am ready.

But, gentlemen my porters, life is brittle:

You carry Cæsar and his fortunes—steady!

You are carried in a

basket,

Like a carcase from the shambles,

To the theatre, a cockpit

Where they stretch you on a table.

Then they bid you close your eyelids,

And they mask you with a napkin,

And the anæsthetic reaches

Hot and subtle through your being.

And you gasp and reel and shudder

In a rushing, swaying rapture,

While the voices at your elbow

Fade—receding—fainter—farther.

Lights about you shower and tumble,

And your blood seems crystallising—

Edged and vibrant, yet within you

Racked and hurried back and forward.

p.

8Then the lights grow fast and furious,

And you hear a noise of waters,

And you wrestle, blind and dizzy,

In an agony of effort,

Till a sudden lull accepts you,

And you sound an utter darkness . . .

And awaken . . . with a struggle . . .

On a hushed, attentive audience.

Like as a flamelet

blanketed in smoke,

So through the anæsthetic shows my life;

So flashes and so fades my thought, at strife

With the strong stupor that I heave and choke

And sicken at, it is so foully sweet.

Faces look strange from space—and disappear.

Far voices, sudden loud, offend my ear—

And hush as sudden. Then my senses fleet:

All were a blank, save for this dull, new pain

That grinds my leg and foot; and brokenly

Time and the place glimpse on to me again;

And, unsurprised, out of uncertainty,

I wake—relapsing—somewhat faint and fain,

To an immense, complacent dreamery.

Lived on one’s

back,

In the long hours of repose,

Life is a practical nightmare—

Hideous asleep or awake.

Shoulders and loins

Ache - - - !

Ache, and the mattress,

Run into boulders and hummocks,

Glows like a kiln, while the bedclothes—

Tumbling, importunate, daft—

Ramble and roll, and the gas,

Screwed to its lowermost,

An inevitable atom of light,

Haunts, and a stertorous sleeper

Snores me to hate and despair.

All the old time

Surges malignant before me;

p. 11Old

voices, old kisses, old songs

Blossom derisive about me;

While the new days

Pass me in endless procession:

A pageant of shadows

Silently, leeringly wending

On . . . and still on . . . still on!

Far in the stillness a cat

Languishes loudly. A cinder

Falls, and the shadows

Lurch to the leap of the flame. The next man to me

Turns with a moan; and the snorer,

The drug like a rope at his throat,

Gasps, gurgles, snorts himself free, as the night-nurse,

Noiseless and strange,

Her bull’s eye half-lanterned in apron,

(Whispering me, ‘Are ye no sleepin’ yet?’),

Passes, list-slippered and peering,

Round . . . and is gone.

Sleep comes at last—

Sleep full of dreams and misgivings—

p. 12Broken

with brutal and sordid

Voices and sounds that impose on me,

Ere I can wake to it,

The unnatural, intolerable day.

The greater masters

of the commonplace,

Rembrandt and good Sir Walter—only these

Could paint her all to you: experienced ease

And antique liveliness and ponderous grace;

The sweet old roses of her sunken face;

The depth and malice of her sly, grey eyes;

The broad Scots tongue that flatters, scolds, defies;

The thick Scots wit that fells you like a mace.

These thirty years has she been nursing here,

Some of them under Syme, her hero

still.

Much is she worth, and even more is made of her.

Patients and students hold her very dear.

The doctors love her, tease her, use her skill.

They say ‘The Chief’ himself is half-afraid of

her.

Some three, or five,

or seven, and thirty years;

A Roman nose; a dimpling double-chin;

Dark eyes and shy that, ignorant of sin,

Are yet acquainted, it would seem, with tears;

A comely shape; a slim, high-coloured hand,

Graced, rather oddly, with a signet ring;

A bashful air, becoming everything;

A well-bred silence always at command.

Her plain print gown, prim cap, and bright steel chain

Look out of place on her, and I remain

Absorbed in her, as in a pleasant mystery.

Quick, skilful, quiet, soft in speech and touch . . .

‘Do you like nursing?’ ‘Yes, Sir, very

much.’

Somehow, I rather think she has a history.

Blue-eyed and bright

of face but waning fast

Into the sere of virginal decay,

I view her as she enters, day by day,

As a sweet sunset almost overpast.

Kindly and calm, patrician to the last,

Superbly falls her gown of sober gray,

And on her chignon’s elegant array

The plainest cap is somehow touched with caste.

She talks Beethoven; frowns

disapprobation

At Balzac’s name, sighs it at

‘poor George

Sand’s’;

Knows that she has exceeding pretty hands;

Speaks Latin with a right accentuation;

And gives at need (as one who understands)

Draught, counsel, diagnosis, exhortation.

Hist? . . .

Through the corridor’s echoes,

Louder and nearer

Comes a great shuffling of feet.

Quick, every one of you,

Strighten your quilts, and be decent!

Here’s the Professor.

In he comes first

With the bright look we know,

From the broad, white brows the kind eyes

Soothing yet nerving you. Here at his elbow,

White-capped, white-aproned, the Nurse,

Towel on arm and her inkstand

Fretful with quills.

Here in the ruck, anyhow,

p. 17Surging

along,

Louts, duffers, exquisites, students, and prigs—

Whiskers and foreheads, scarf-pins and spectacles—

Hustles the Class! And they ring themselves

Round the first bed, where the Chief

(His dressers and clerks at attention),

Bends in inspection already.

So shows the ring

Seen from behind round a conjurer

Doing his pitch in the street.

High shoulders, low shoulders, broad shoulders, narrow ones,

Round, square, and angular, serry and shove;

While from within a voice,

Gravely and weightily fluent,

Sounds; and then ceases; and suddenly

(Look at the stress of the shoulders!)

Out of a quiver of silence,

Over the hiss of the spray,

Comes a low cry, and the sound

Of breath quick intaken through teeth

Clenched in resolve. And the Master

Breaks from the crowd, and goes,

Wiping his hands,

p. 18To the

next bed, with his pupils

Flocking and whispering behind him.

Now one can see.

Case Number One

Sits (rather pale) with his bedclothes

Stripped up, and showing his foot

(Alas for God’s Image!)

Swaddled in wet, white lint

Brilliantly hideous with red.

Two and thirty is

the ploughman.

He’s a man of gallant inches,

And his hair is close and curly,

And his beard;

But his face is wan and sunken,

And his eyes are large and brilliant,

And his shoulder-blades are sharp,

And his knees.

He is weak of wits, religious,

Full of sentiment and yearning,

Gentle, faded—with a cough

And a snore.

When his wife (who was a widow,

And is many years his elder)

Fails to write, and that is always,

He desponds.

p.

20Let his melancholy wander,

And he’ll tell you pretty stories

Of the women that have wooed him

Long ago;

Or he’ll sing of bonnie lasses

Keeping sheep among the heather,

With a crackling, hackling click

In his voice.

As with varnish red

and glistening

Dripped his hair; his feet looked rigid;

Raised, he settled stiffly sideways:

You could see his hurts were spinal.

He had fallen from an engine,

And been dragged along the metals.

It was hopeless, and they knew it;

So they covered him, and left him.

As he lay, by fits half sentient,

Inarticulately moaning,

With his stockinged soles protruded

Stark and awkward from the blankets,

To his bed there came a woman,

Stood and looked and sighed a little,

And departed without speaking,

As himself a few hours after.

p.

22I was told it was his sweetheart.

They were on the eve of marriage.

She was quiet as a statue,

But her lip was grey and writhen.

From the

winter’s grey despair,

From the summer’s golden languor,

Death, the lover of Life,

Frees us for ever.

Inevitable, silent, unseen,

Everywhere always,

Shadow by night and as light in the day,

Signs she at last to her chosen;

And, as she waves them forth,

Sorrow and Joy

Lay by their looks and their voices,

Set down their hopes, and are made

One in the dim Forever.

Into the winter’s grey delight,

Into the summer’s golden dream,

Holy and high and impartial,

Death, the mother of Life,

Mingles all men for ever.

His brow spreads

large and placid, and his eye

Is deep and bright, with steady looks that still.

Soft lines of tranquil thought his face fulfill—

His face at once benign and proud and shy.

If envy scout, if ignorance deny,

His faultless patience, his unyielding will,

Beautiful gentleness and splendid skill,

Innumerable gratitudes reply.

His wise, rare smile is sweet with certainties,

And seems in all his patients to compel

Such love and faith as failure cannot quell.

We hold him for another Herakles,

Battling with custom, prejudice, disease,

As once the son of Zeus with Death and Hell.

Exceeding tall, but

built so well his height

Half-disappears in flow of chest and limb;

Moustache and whisker trooper-like in trim;

Frank-faced, frank-eyed, frank-hearted; always bright

And always punctual—morning, noon, and night;

Bland as a Jesuit, sober as a hymn;

Humorous, and yet without a touch of whim;

Gentle and amiable, yet full of fight.

His piety, though fresh and true in strain,

Has not yet whitewashed up his common mood

To the dead blank of his particular Schism.

Sweet, unaggressive, tolerant, most humane,

Wild artists like his kindly elderhood,

And cultivate his mild Philistinism.

O, the fun, the fun

and frolic

That The Wind that Shakes the Barley

Scatters through a penny-whistle

Tickled with artistic fingers!

Kate the scrubber (forty summers,

Stout but sportive) treads a measure,

Grinning, in herself a ballet,

Fixed as fate upon her audience.

Stumps are shaking, crutch-supported;

Splinted fingers tap the rhythm;

And a head all helmed with plasters

Wags a measured approbation.

Of their mattress-life oblivious,

All the patients, brisk and cheerful,

Are encouraging the dancer,

And applauding the musician.

p.

27Dim the gas-lights in the output

Of so many ardent smokers,

Full of shadow lurch the corners,

And the doctor peeps and passes.

There are, maybe, some suspicions

Of an alcoholic presence . . .

‘Tak’ a sup of this, my wumman!’ .

. .

New Year comes but once a twelvemonth.

Here in this dim,

dull, double-bedded room,

I play the father to a brace of boys,

Ailing but apt for every sort of noise,

Bedfast but brilliant yet with health and bloom.

Roden, the Irishman, is ‘sieven past,’

Blue-eyed, snub-nosed, chubby, and fair of face.

Willie’s but six, and seems to like the place,

A cheerful little collier to the last.

They eat, and laugh, and sing, and fight, all day;

All night they sleep like dormice. See them play

At Operations:—Roden, the Professor,

Saws, lectures, takes the artery up, and ties;

Willie, self-chloroformed, with half-shut eyes,

Holding the limb and moaning—Case and Dresser.

She’s tall and

gaunt, and in her hard, sad face

With flashes of the old fun’s animation

There lowers the fixed and peevish resignation

Bred of a past where troubles came apace.

She tells me that her husband, ere he died,

Saw seven of their children pass away,

And never knew the little lass at play

Out on the green, in whom he’s deified.

Her kin dispersed, her friends forgot and gone,

All simple faith her honest Irish mind,

Scolding her spoiled young saint, she labours on:

Telling her dreams, taking her patients’ part,

Trailing her coat sometimes: and you shall find

No rougher, quainter speech, nor kinder heart.

Her little face is

like a walnut shell

With wrinkling lines; her soft, white hair adorns

Her withered brows in quaint, straight curls, like horns;

And all about her clings an old, sweet smell.

Prim is her gown and quakerlike her shawl.

Well might her bonnets have been born on her.

Can you conceive a Fairy Godmother

The subject of a strong religious call?

In snow or shine, from bed to bed she runs,

All twinkling smiles and texts and pious tales,

Her mittened hands, that ever give or pray,

Bearing a sheaf of tracts, a bag of buns:

A wee old maid that sweeps the Bridegroom’s way,

Strong in a cheerful trust that never fails.

‘Talk of

pluck!’ pursued the Sailor,

Set at euchre on his elbow,

‘I was on the wharf at Charleston,

Just ashore from off the runner.

‘It was grey and dirty weather,

And I heard a drum go rolling,

Rub-a-dubbing in the distance,

Awful dour-like and defiant.

‘In and out among the cotton,

Mud, and chains, and stores, and anchors,

Tramped a squad of battered scarecrows—

Poor old Dixie’s bottom dollar!

‘Some had shoes, but all had rifles,

Them that wasn’t bald was beardless,

And the drum was rolling Dixie,

And they stepped to it like men, sir!

p.

32‘Rags and tatters, belts and bayonets,

On they swung, the drum a-rolling,

Mum and sour. It looked like fighting,

And they meant it too, by thunder!’

It’s the

Spring.

Earth has conceived, and her bosom,

Teeming with summer, is glad.

Vistas of change and adventure,

Thro’ the green land

The grey roads go beckoning and winding,

Peopled with wains, and melodious

With harness-bells jangling:

Jangling and twangling rough rhythms

To the slow march of the stately, great horses

Whistled and shouted along.

White fleets of cloud,

Argosies heavy with fruitfulness,

Sail the blue peacefully. Green flame the hedgerows.

Blackbirds are bugling, and white in wet winds

Sway the tall poplars.

p. 34Pageants

of colour and fragrance,

Pass the sweet meadows, and viewless

Walks the mild spirit of May,

Visibly blessing the world.

O, the brilliance of blossoming orchards!

O, the savour and thrill of the woods,

When their leafage is stirred

By the flight of the Angel of Rain!

Loud lows the steer; in the fallows

Rooks are alert; and the brooks

Gurgle and tinkle and trill. Thro’ the gloamings,

Under the rare, shy stars,

Boy and girl wander,

Dreaming in darkness and dew.

It’s the Spring.

A sprightliness feeble and squalid

Wakes in the ward, and I sicken,

Impotent, winter at heart.

Down the quiet

eve,

Thro’ my window with the sunset

Pipes to me a distant organ

Foolish ditties;

And, as when you change

Pictures in a magic lantern,

Books, beds, bottles, floor, and ceiling

Fade and vanish,

And I’m well once more . . .

August flares adust and torrid,

But my heart is full of April

Sap and sweetness.

In the quiet eve

I am loitering, longing, dreaming . . .

Dreaming, and a distant organ

Pipes me ditties.

p.

36I can see the shop,

I can smell the sprinkled pavement,

Where she serves—her chestnut chignon

Thrills my senses!

O, the sight and scent,

Wistful eve and perfumed pavement!

In the distance pipes an organ . . .

The sensation

Comes to me anew,

And my spirit for a moment

Thro’ the music breathes the blessèd

Airs of London.

Staring corpselike

at the ceiling,

See his harsh, unrazored features,

Ghastly brown against the pillow,

And his throat—so strangely bandaged!

Lack of work and lack of victuals,

A debauch of smuggled whisky,

And his children in the workhouse

Made the world so black a riddle

That he plunged for a solution;

And, although his knife was edgeless,

He was sinking fast towards one,

When they came, and found, and saved him.

Stupid now with shame and sorrow,

In the night I hear him sobbing.

But sometimes he talks a little.

He has told me all his troubles.

p.

38In his broad face, tanned and bloodless,

White and wild his eyeballs glisten;

And his smile, occult and tragic,

Yet so slavish, makes you shudder!

Thin-legged,

thin-chested, slight unspeakably,

Neat-footed and weak-fingered: in his face—

Lean, large-boned, curved of beak, and touched with race,

Bold-lipped, rich-tinted, mutable as the sea,

The brown eyes radiant with vivacity—

There shines a brilliant and romantic grace,

A spirit intense and rare, with trace on trace

Of passion and impudence and energy.

Valiant in velvet, light in ragged luck,

Most vain, most generous, sternly critical,

Buffoon and poet, lover and sensualist:

A deal of Ariel, just a streak of Puck,

Much Antony, of Hamlet most of all,

And something of the Shorter-Catechist.

Laughs the happy

April morn

Thro’ my grimy, little window,

And a shaft of sunshine pushes

Thro’ the shadows in the square.

Dogs are tracing thro’ the grass,

Crows are cawing round the chimneys,

In and out among the washing

Goes the West at hide-and-seek.

Loud and cheerful clangs the bell.

Here the nurses troop to breakfast.

Handsome, ugly, all are women . . .

O, the Spring—the Spring—the Spring!

At the barren heart

of midnight,

When the shadow shuts and opens

As the loud flames pulse and flutter,

I can hear a cistern leaking.

Dripping, dropping, in a rhythm,

Rough, unequal, half-melodious,

Like the measures aped from nature

In the infancy of music;

Like the buzzing of an insect,

Still, irrational, persistent . . .

I must listen, listen, listen

In a passion of attention;

Till it taps upon my heartstrings,

And my very life goes dripping,

Dropping, dripping, drip-drip-dropping,

In the drip-drop of the cistern.

Carry me out

Into the wind and the sunshine,

Into the beautiful world.

O, the wonder, the spell of the streets!

The stature and strength of the horses,

The rustle and echo of footfalls,

The flat roar and rattle of wheels!

A swift tram floats huge on us . . .

It’s a dream?

The smell of the mud in my nostrils

Blows brave—like a breath of the sea!

As of old,

Ambulant, undulant drapery,

Vaguery and strangely provocative,

Fluttersd and beckons. O, yonder—

Is it?—the gleam of a stocking!

Sudden, a spire

p. 43Wedged in

the mist! O, the houses,

The long lines of lofty, grey houses,

Cross-hatched with shadow and light!

These are the streets . . .

Each is an avenue leading

Whither I will!

Free . . . !

Dizzy, hysterical, faint,

I sit, and the carriage rolls on with me

Into the wonderful world.

The Old Infirmary, Edinburgh, 1873–75

Do you remember

That afternoon—that Sunday afternoon!—

When, as the kirks were ringing in,

And the grey city teemed

With Sabbath feelings and aspects,

Lewis—our Lewis then,

Now the whole world’s—and you,

Young, yet in shape most like an elder, came,

Laden with Balzacs

(Big, yellow books, quite impudently French),

The first of many times

To that transformed back-kitchen where I lay

So long, so many centuries—

Or years is it!—ago?

Dear Charles, since

then

We have been friends, Lewis and you

and I,

(How good it sounds, ‘Lewis and

you and I!’):

Such friends, I like to think,

p. 45That in us

three, Lewis and me and you,

Is something of that gallant dream

Which old Dumas—the generous,

the humane,

The seven-and-seventy times to be forgiven!—

Dreamed for a blessing to the race,

The immortal Musketeers.

Our Athos

rests—the wise, the kind,

The liberal and august, his fault atoned,

Rests in the crowded yard

There at the west of Princes Street. We three—

You, I, and Lewis!—still

afoot,

Are still together, and our lives,

In chime so long, may keep

(God bless the thought!)

Unjangled till the end.

W. E. H.

Chiswick, March 1888

(To Rudyard Kipling)

1890

p.

49The Sword

Singing—

The voice of the Sword from the heart of the Sword

Clanging imperious

Forth from Time’s battlements

His ancient and triumphing Song.

In the beginning,

Ere God inspired Himself

Into the clay thing

Thumbed to His image,

The vacant, the naked shell

Soon to be Man:

Thoughtful He pondered it,

Prone there and impotent,

p. 50Fragile,

inviting

Attack and discomfiture;

Then, with a smile—

As He heard in the Thunder

That laughed over Eden

The voice of the Trumpet,

The iron Beneficence,

Calling his dooms

To the Winds of the world—

Stooping, He drew

On the sand with His finger

A shape for a sign

Of his way to the eyes

That in wonder should waken,

For a proof of His will

To the breaking intelligence.

That was the birth of me:

I am the Sword.

Bleak and lean, grey and cruel,

Short-hilted, long shafted,

I froze into steel;

And the blood of my elder,

His hand on the hafts of me,

Sprang like a wave

p. 51In the

wind, as the sense

Of his strength grew to ecstasy;

Glowed like a coal

In the throat of the furnace;

As he knew me and named me

The War-Thing, the Comrade,

Father of honour

And giver of kingship,

The fame-smith, the song-master,

Bringer of women

On fire at his hands

For the pride of fulfilment,

Priest (saith the Lord)

Of his marriage with victory

Ho! then, the Trumpet,

Handmaid of heroes,

Calling the peers

To the place of espousals!

Ho! then, the splendour

And glare of my ministry,

Clothing the earth

With a livery of lightnings!

Ho! then, the music

Of battles in onset,

And ruining armours,

p. 52And

God’s gift returning

In fury to God!

Thrilling and keen

As the song of the winter stars,

Ho! then, the sound

Of my voice, the implacable

Angel of Destiny!—

I am the Sword.

Heroes, my children,

Follow, O, follow me!

Follow, exulting

In the great light that breaks

From the sacred Companionship!

Thrust through the fatuous,

Thrust through the fungous brood,

Spawned in my shadow

And gross with my gift!

Thrust through, and hearken

O, hark, to the Trumpet,

The Virgin of Battles,

Calling, still calling you

Into the Presence,

Sons of the Judgment,

Pure wafts of the Will!

p. 53Edged to

annihilate,

Hilted with government,

Follow, O, follow me,

Till the waste places

All the grey globe over

Ooze, as the honeycomb

Drips, with the sweetness

Distilled of my strength,

And, teeming in peace

Through the wrath of my coming,

They give back in beauty

The dread and the anguish

They had of me visitant!

Follow, O follow, then,

Heroes, my harvesters!

Where the tall grain is ripe

Thrust in your sickles!

Stripped and adust

In a stubble of empire,

Scything and binding

The full sheaves of sovranty:

Thus, O, thus gloriously,

Shall you fulfil yourselves!

Thus, O, thus mightily,

Show yourselves sons of mine—

p. 54Yea, and

win grace of me:

I am the Sword!

I am the feast-maker:

Hark, through a noise

Of the screaming of eagles,

Hark how the Trumpet,

The mistress of mistresses,

Calls, silver-throated

And stern, where the tables

Are spread, and the meal

Of the Lord is in hand!

Driving the darkness,

Even as the banners

And spears of the Morning;

Sifting the nations,

The slag from the metal,

The waste and the weak

From the fit and the strong;

Fighting the brute,

The abysmal Fecundity;

Checking the gross,

Multitudinous blunders,

The groping, the purblind

p. 55Excesses

in service

Of the Womb universal,

The absolute drudge;

Firing the charactry

Carved on the World,

The miraculous gem

In the seal-ring that burns

On the hand of the Master—

Yea! and authority

Flames through the dim,

Unappeasable Grisliness

Prone down the nethermost

Chasms of the Void!—

Clear singing, clean slicing;

Sweet spoken, soft finishing;

Making death beautiful,

Life but a coin

To be staked in the pastime

Whose playing is more

Than the transfer of being;

Arch-anarch, chief builder,

Prince and evangelist,

I am the Will of God:

I am the Sword.

p.

56The Sword

Singing—

The voice of the Sword from the heart of the Sword

Clanging majestical,

As from the starry-staired

Courts of the primal Supremacy,

His high, irresistible song.

(To Elizabeth Robins Pennell)

1893

Once on a time

There was a little boy: a master-mage

By virtue of a Book

Of magic—O, so magical it filled

His life with visionary pomps

Processional! And Powers

Passed with him where he passed. And Thrones

And Dominations, glaived and plumed and mailed,

Thronged in the criss-cross streets,

The palaces pell-mell with playing-fields,

Domes, cloisters, dungeons, caverns, tents, arcades,

Of the unseen, silent City, in his soul

Pavilioned jealously, and hid

As in the dusk, profound,

Green stillnesses of some enchanted mere.—

I shut mine eyes . . . And lo!

A flickering snatch of memory that floats

p. 60Upon the

face of a pool of darkness five

And thirty dead years deep,

Antic in girlish broideries

And skirts and silly shoes with straps

And a broad-ribanded leghorn, he walks

Plain in the shadow of a church

(St. Michael’s: in whose brazen call

To curfew his first wails of wrath were whelmed),

Sedate for all his haste

To be at home; and, nestled in his arm,

Inciting still to quiet and solitude,

Boarded in sober drab,

With small, square, agitating cuts

Let in a-top of the double-columned, close,

Quakerlike print, a Book! . . .

What but that blessed brief

Of what is gallantest and best

In all the full-shelved Libraries of Romance?

The Book of rocs,

Sandalwood, ivory, turbans, ambergris,

Cream-tarts, and lettered apes, and calendars,

And ghouls, and genies—O, so huge

They might have overed the tall Minster Tower

Hands down, as schoolboys take a post!

In truth, the Book of Camaralzaman,

p.

61Schemselnihar and Sindbad, Scheherezade

The peerless, Bedreddin, Badroulbadour,

Cairo and Serendib and Candahar,

And Caspian, and the dim, terrific bulk—

Ice-ribbed, fiend-visited, isled in spells and storms—

Of Kaf! . . . That centre of miracles,

The sole, unparalleled Arabian Nights!

Old friends I had a-many—kindly and

grim

Familiars, cronies quaint

And goblin! Never a Wood but housed

Some morrice of dainty dapperlings. No Brook

But had his nunnery

Of green-haired, silvry-curving sprites,

To cabin in his grots, and pace

His lilied margents. Every lone Hillside

Might open upon Elf-Land. Every Stalk

That curled about a Bean-stick was of the breed

Of that live ladder by whose delicate rungs

You climbed beyond the clouds, and found

The Farm-House where the Ogre, gorged

And drowsy, from his great oak chair,

Among the flitches and pewters at the fire,

Called for his Faëry Harp. And in it flew,

p. 62And,

perching on the kitchen table, sang

Jocund and jubilant, with a sound

Of those gay, golden-vowered madrigals

The shy thrush at mid-May

Flutes from wet orchards flushed with the triumphing dawn;

Or blackbirds rioting as they listened still,

In old-world woodlands rapt with an old-world spring,

For Pan’s own whistle, savage and rich and lewd,

And mocked him call for call!

I

could not pass

The half-door where the cobbler sat in view

Nor figure me the wizen Leprechaun,

In square-cut, faded reds and buckle-shoes,

Bent at his work in the hedge-side, and know

Just how he tapped his brogue, and twitched

His wax-end this and that way, both with wrists

And elbows. In the rich June fields,

Where the ripe clover drew the bees,

And the tall quakers trembled, and the West Wind

Lolled his half-holiday away

Beside me lolling and lounging through my own,

p.

63’Twas good to follow the Miller’s Youngest

Son

On his white horse along the leafy lanes;

For at his stirrup linked and ran,

Not cynical and trapesing, as he loped

From wall to wall above the espaliers,

But in the bravest tops

That market-town, a town of tops, could show:

Bold, subtle, adventurous, his tail

A banner flaunted in disdain

Of human stratagems and shifts:

King over All the Catlands, present and past

And future, that moustached

Artificer of fortunes, Puss-in-Boots!

Or Bluebeard’s Closet, with its plenishing

Of meat-hooks, sawdust, blood,

And wives that hung like fresh-dressed carcases—

Odd-fangled, most a butcher’s, part

A faëry chamber hazily seen

And hazily figured—on dark afternoons

And windy nights was visiting of the best.

Then, too, the pelt of hoofs

Out in the roaring darkness told

Of Herne the Hunter in his antlered helm

Galloping, as with despatches from the Pit,

Between his hell-born Hounds.

p. 64And Rip

Van Winkle . . . often I lurked to hear,

Outside the long, low timbered, tarry wall,

The mutter and rumble of the trolling bowls

Down the lean plank, before they fluttered the pins;

For, listening, I could help him play

His wonderful game,

In those blue, booming hills, with Mariners

Refreshed from kegs not coopered in this our world.

But what were these so near,

So neighbourly fancies to the spell that brought

The run of Ali Baba’s Cave

Just for the saying ‘Open Sesame,’

With gold to measure, peck by peck,

In round, brown wooden stoups

You borrowed at the chandler’s? . . . Or one time

Made you Aladdin’s friend at school,

Free of his Garden of Jewels, Ring and Lamp

In perfect trim? . . . Or Ladies, fair

For all the embrowning scars in their white breasts

Went labouring under some dread ordinance,

Which made them whip, and bitterly cry the while,

Strange Curs that cried as they,

Till there was never a Black Bitch of all

p. 65Your

consorting but might have gone

Spell-driven miserably for crimes

Done in the pride of womanhood and desire . . .

Or at the ghostliest altitudes of night,

While you lay wondering and acold,

Your sense was fearfully purged; and soon

Queen Labé, abominable and dear,

Rose from your side, opened the Box of Doom,

Scattered the yellow powder (which I saw

Like sulphur at the Docks in bulk),

And muttered certain words you could not hear;

And there! a living stream,

The brook you bathed in, with its weeds and flags

And cresses, glittered and sang

Out of the hearthrug over the nakedness,

Fair-scrubbed and decent, of your bedroom floor! . . .

I was—how many a time!—

That Second Calendar, Son of a King,

On whom ’twas vehemently enjoined,

Pausing at one mysterious door,

To pry no closer, but content his soul

With his kind Forty. Yet I could not rest

For idleness and ungovernable Fate.

p. 66And the

Black Horse, which fed on sesame

(That wonder-working word!),

Vouchsafed his back to me, and spread his vans,

And soaring, soaring on

From air to air, came charging to the ground

Sheer, like a lark from the midsummer clouds,

And, shaking me out of the saddle, where I sprawled

Flicked at me with his tail,

And left me blinded, miserable, distraught

(Even as I was in deed,

When doctors came, and odious things were done

On my poor tortured eyes

With lancets; or some evil acid stung

And wrung them like hot sand,

And desperately from room to room

Fumble I must my dark, disconsolate way),

To get to Bagdad how I might. But there

I met with Merry Ladies. O you three—

Safie, Amine, Zobëidé—when my heart

Forgets you all shall be forgot!

And so we supped, we and the rest,

On wine and roasted lamb, rose-water, dates,

Almonds, pistachios, citrons. And Haroun

Laughed out of his lordly beard

p. 67On Giaffar

and Mesrour (I knew the Three

For all their Mossoul habits). And outside

The Tigris, flowing swift

Like Severn bend for bend, twinkled and gleamed

With broken and wavering shapes of stranger stars;

The vast, blue night

Was murmurous with peris’ plumes

And the leathern wings of genies; words of power

Were whispering; and old fishermen,

Casting their nets with prayer, might draw to shore

Dead loveliness: or a prodigy in scales

Worth in the Caliph’s Kitchen pieces of gold:

Or copper vessels, stopped with lead,

Wherein some Squire of Eblis watched and railed,

In durance under potent charactry

Graven by the seal of Solomon the King . . .

Then, as the Book was glassed

In Life as in some olden mirror’s quaint,

Bewildering angles, so would Life

Flash light on light back on the Book; and both

Were changed. Once in a house decayed

From better days, harbouring an errant show

(For all its stories of dry-rot

p. 68Were

filled with gruesome visitants in wax,

Inhuman, hushed, ghastly with Painted Eyes),

I wandered; and no living soul

Was nearer than the pay-box; and I stared

Upon them staring—staring. Till at last,

Three sets of rafters from the streets,

I strayed upon a mildewed, rat-run room,

With the two Dancers, horrible and obscene,

Guarding the door: and there, in a bedroom-set,

Behind a fence of faded crimson cords,

With an aspect of frills

And dimities and dishonoured privacy

That made you hanker and hesitate to look,

A Woman with her litter of Babes—all slain,

All in their nightgowns, all with Painted Eyes

Staring—still staring; so that I turned and ran

As for my neck, but in the street

Took breath. The same, it seemed,

And yet not all the same, I was to find,

As I went up! For afterwards,

Whenas I went my round alone—

All day alone—in long, stern, silent streets,

Where I might stretch my hand and take

Whatever I would: still there were Shapes of Stone,

p.

69Motionless, lifelike, frightening—for the Wrath

Had smitten them; but they watched,

This by her melons and figs, that by his rings

And chains and watches, with the hideous gaze,

The Painted Eyes insufferable,

Now, of those grisly images; and I

Pursued my best-belovéd quest,

Thrilled with a novel and delicious fear.

So the night fell—with never a lamplighter;

And through the Palace of the King

I groped among the echoes, and I felt

That they were there,

Dreadfully there, the Painted staring Eyes,

Hall after hall . . . Till lo! from far

A Voice! And in a little while

Two tapers burning! And the Voice,

Heard in the wondrous Word of God, was—whose?

Whose but Zobëidé’s,

The lady of my heart, like me

A True Believer, and like me

An outcast thousands of leagues beyond the pale! . . .

Or, sailing to the Isles

Of Khaledan, I spied one evenfall

A black blotch in the sunset; and it grew

p. 70Swiftly .

. . and grew. Tearing their beards,

The sailors wept and prayed; but the grave ship,

Deep laden with spiceries and pearls, went mad,

Wrenched the long tiller out of the steersman’s hand,

And, turning broadside on,

As the most iron would, was haled and sucked

Nearer, and nearer yet;

And, all awash, with horrible lurching leaps

Rushed at that Portent, casting a shadow now

That swallowed sea and sky; and then,

Anchors and nails and bolts

Flew screaming out of her, and with clang on clang,

A noise of fifty stithies, caught at the sides

Of the Magnetic Mountain; and she lay,

A broken bundle of firewood, strown piecemeal

About the waters; and her crew

Passed shrieking, one by one; and I was left

To drown. All the long night I swam;

But in the morning, O, the smiling coast

Tufted with date-trees, meadowlike,

Skirted with shelving sands! And a great wave

Cast me ashore; and I was saved alive.

So, giving thanks to God, I dried my clothes,

And, faring inland, in a desert place

p. 71I stumbled

on an iron ring—

The fellow of fifty built into the Quays:

When, scenting a trap-door,

I dug, and dug; until my biggest blade

Stuck into wood. And then,

The flight of smooth-hewn, easy-falling stairs,

Sunk in the naked rock! The cool, clean vault,

So neat with niche on niche it might have been

Our beer-cellar but for the rows

Of brazen urns (like monstrous chemist’s jars)

Full to the wide, squat throats

With gold-dust, but a-top

A layer of pickled-walnut-looking things

I knew for olives! And far, O, far away,

The Princess of China languished! Far away

Was marriage, with a Vizier and a Chief

Of Eunuchs and the privilege

Of going out at night

To play—unkenned, majestical, secure—

Where the old, brown, friendly river shaped

Like Tigris shore for shore! Haply a Ghoul

Sat in the churchyard under a frightened moon,

A thighbone in his fist, and glared

At supper with a Lady: she who took

Her rice with tweezers grain by grain.

p. 72Or you

might stumble—there by the iron gates

Of the Pump Room—underneath the limes—

Upon Bedreddin in his shirt and drawers,

Just as the civil Genie laid him down.

Or those red-curtained panes,

Whence a tame cornet tenored it throatily

Of beer-pots and spittoons and new long pipes,

Might turn a caravansery’s, wherein

You found Noureddin Ali, loftily drunk,

And that fair Persian, bathed in tears,

You’d not have given away

For all the diamonds in the Vale Perilous

You had that dark and disleaved afternoon

Escaped on a roc’s claw,

Disguised like Sindbad—but in Christmas beef!

And all the blissful while

The schoolboy satchel at your hip

Was such a bulse of gems as should amaze

Grey-whiskered chapmen drawn

From over Caspian: yea, the Chief Jewellers

Of Tartary and the bazaars,

Seething with traffic, of enormous Ind.—

Thus cried, thus called aloud, to the child

heart

The magian East: thus the child eyes

p. 73Spelled

out the wizard message by the light

Of the sober, workaday hours

They saw, week in week out, pass, and still pass

In the sleepy Minster City, folded kind

In ancient Severn’s arm,

Amongst her water-meadows and her docks,

Whose floating populace of ships—

Galliots and luggers, light-heeled brigantines,

Bluff barques and rake-hell fore-and-afters—brought

To her very doorsteps and geraniums

The scents of the World’s End; the calls

That may not be gainsaid to rise and ride

Like fire on some high errand of the race;

The irresistible appeals

For comradeship that sound

Steadily from the irresistible sea.

Thus the East laughed and whispered, and the tale,

Telling itself anew

In terms of living, labouring life,

Took on the colours, busked it in the wear

Of life that lived and laboured; and Romance,

The Angel-Playmate, raining down

His golden influences

On all I saw, and all I dreamed and did,

p. 74Walked

with me arm in arm,

Or left me, as one bediademed with straws

And bits of glass, to gladden at my heart

Who had the gift to seek and feel and find

His fiery-hearted presence everywhere.

Even so dear Hesper, bringer of all good things,

Sends the same silver dews

Of happiness down her dim, delighted skies

On some poor collier-hamlet—(mound on mound

Of sifted squalor; here a soot-throated stalk

Sullenly smoking over a row

Of flat-faced hovels; black in the gritty air

A web of rails and wheels and beams; with strings

Of hurtling, tipping trams)—

As on the amorous nightingales

And roses of Shíraz, or the walls and towers

Of Samarcand—the Ineffable—whence you espy

The splendour of Ginnistan’s embattled spears,

Like listed lightnings.

Samarcand!

That name of names! That star-vaned belvedere

Builded against the Chambers of the South!

That outpost on the Infinite!

And behold!

Questing therefrom, you knew not what wild tide

p. 75Might

overtake you: for one fringe,

One suburb, is stablished on firm earth; but one

Floats founded vague

In lubberlands delectable—isles of palm

And lotus, fortunate mains, far-shimmering seas,

The promise of wistful hills—

The shining, shifting Sovranties of Dream.

1877–1888

To W. A.

Was I a Samurai

renowned,

Two-sworded, fierce, immense of bow?

A histrion angular and profound?

A priest? a porter?—Child, although

I have forgotten clean, I know

That in the shade of Fujisan,

What time the cherry-orchards blow,

I loved you once in old Japan.

As here you loiter, flowing-gowned

And hugely sashed, with pins a-row

Your quaint head as with flamelets crowned,

Demure, inviting—even so,

When merry maids in Miyako

To feel the sweet o’ the year began,

And green gardens to overflow,

I loved you once in old Japan.

p.

80Clear shine the hills; the rice-fields round

Two cranes are circling; sleepy and slow,

A blue canal the lake’s blue bound

Breaks at the bamboo bridge; and lo!

Touched with the sundown’s spirit and glow,

I see you turn, with flirted fan,

Against the plum-tree’s bloomy snow . . .

I loved you once in old Japan!

Envoy

Dear, ’twas a dozen lives ago;

But that I was a lucky man

The Toyokuni here will show:

I loved you—once—in old Japan.

I.

M.

Thomas Edward Brown

(1829–1896)

Spring at her height

on a morn at prime,

Sails that laugh from a flying squall,

Pomp of harmony, rapture of rhyme—

Youth is the sign of them, one and all.

Winter sunsets and leaves that fall,

An empty flagon, a folded page,

A tumble-down wheel, a tattered ball—

These are a type of the world of Age.

Bells that clash in a gaudy chime,

Swords that clatter in onsets tall,

The words that ring and the fames that climb—

Youth is the sign of them, one and all.

Hymnals old in a dusty stall,

A bald, blind bird in a crazy cage,

The scene of a faded festival—

These are a type of the world of Age.

p.

82Hours that strut as the heirs of time,

Deeds whose rumour’s a clarion-call,

Songs where the singers their souls sublime—

Youth is the sign of them, one and all.

A staff that rests in a nook of wall,

A reeling battle, a rusted gage,

The chant of a nearing funeral—

These are a type of the world of Age.

Envoy

Struggle and turmoil, revel and brawl—

Youth is the sign of them, one and all.

A smouldering hearth and a silent stage—

These are a type of the world of Age.

To W. H.

With a ripple of

leaves and a tinkle of streams

The full world rolls in a rhythm of praise,

And the winds are one with the clouds and beams—

Midsummer days! Midsummer days!

The dusk grows vast; in a purple haze,

While the West from a rapture of sunset rights,

Faint stars their exquisite lamps upraise—

Midsummer nights! O midsummer nights!

The wood’s green heart is a nest of

dreams,

The lush grass thickens and springs and sways,

The rathe wheat rustles, the landscape gleams—

Midsummer days! Midsummer days!

In the stilly fields, in the stilly ways,

All secret shadows and mystic lights,

Late lovers murmur and linger and gaze—

Midsummer nights! O midsummer nights!

p.

84There’s a music of bells from the trampling

teams,

Wild skylarks hover, the gorses blaze,

The rich, ripe rose as with incense steams—

Midsummer days! Midsummer days!

A soul from the honeysuckle strays,

And the nightingale as from prophet heights

Sings to the Earth of her million Mays—

Midsummer nights! O midsummer nights!

Envoy

And it’s O, for my dear and the charm

that stays—

Midsummer days! Midsummer days!

It’s O, for my Love and the dark that plights—

Midsummer nights! O midsummer nights!

I.

M.

Edward John Henley

(1861–1898)

Where are the

passions they essayed,

And where the tears they made to flow?

Where the wild humours they portrayed

For laughing worlds to see and know?

Othello’s wrath and Juliet’s woe?

Sir Peter’s whims and Timon’s gall?

And Millamant and Romeo?

Into the night go one and all.

Where are the braveries, fresh or frayed?

The plumes, the armours—friend and foe?

The cloth of gold, the rare brocade,

The mantles glittering to and fro?

The pomp, the pride, the royal show?

The cries of war and festival?

The youth, the grace, the charm, the glow?

Into the night go one and all.

p.

86The curtain falls, the play is played:

The Beggar packs beside the Beau;

The Monarch troops, and troops the Maid;

The Thunder huddles with the Snow.

Where are the revellers high and low?

The clashing swords? The lover’s call?

The dancers gleaming row on row?

Into the night go one and all.

Envoy

Prince, in one common

overthrow

The Hero tumbles with the Thrall:

As dust that drives, as straws that blow,

Into the night go one and all.

To C. M.

Fountains that frisk

and sprinkle

The moss they overspill;

Pools that the breezes crinkle;

The wheel beside the mill,

With its wet, weedy frill;

Wind-shadows in the wheat;

A water-cart in the street;

The fringe of foam that girds

An islet’s ferneries;

A green sky’s minor thirds—

To live, I think of these!

Of ice and glass the tinkle,

Pellucid, silver-shrill;

Peaches without a wrinkle;

Cherries and snow at will,

From china bowls that fill

The senses with a sweet

p.

88Incuriousness of heat;

A melon’s dripping sherds;

Cream-clotted strawberries;

Dusk dairies set with curds—

To live, I think of these!

Vale-lily and periwinkle;

Wet stone-crop on the sill;

The look of leaves a-twinkle

With windlets clear and still;

The feel of a forest rill

That wimples fresh and fleet

About one’s naked feet;

The muzzles of drinking herds;

Lush flags and bulrushes;

The chirp of rain-bound birds—

To live, I think of these!

Envoy

Dark aisles, new packs of cards,

Mermaidens’ tails, cool swards,

Dawn dews and starlit seas,

White marbles, whiter words—

To live, I think of these!

Gold or silver,

every day,

Dies to gray.

There are knots in every skein.

Hours of work and hours of play

Fade away

Into one immense Inane.

Shadow and substance, chaff and grain,

Are as vain

As the foam or as the spray.

Life goes crooning, faint and fain,

One refrain:

‘If it could be always May!’

Though the earth be green and gay,

Though, they

say,

Man the cup of heaven may drain;

Though, his little world to sway,

He display

Hoard on hoard of pith and brain:

Autumn brings a mist and rain

That

constrain

p. 90Him and

his to know decay,

Where undimmed the lights that wane

Would remain,

If it could be always May.

Yea, alas, must turn to Nay,

Flesh to

clay.

Chance and Time are ever twain.

Men may scoff, and men may pray,

But they pay

Every pleasure with a pain.

Life may soar, and Fortune deign

To explain

Where her prizes hide and stay;

But we lack the lusty train

We should

gain,

If it could be always May.

Envoy

Time, the pedagogue, his cane

Might retain,

But his charges all would stray

Truanting in every lane—

Jack with

Jane—

If it could be always May.

Fools may pine, and

sots may swill,

Cynics gibe, and prophets rail,

Moralists may scourge and drill,

Preachers prose, and fainthearts quail.

Let them whine, or threat, or wail!

Till the touch of Circumstance

Down to darkness sink the scale,

Fate’s a fiddler, Life’s a dance.

What if skies be wan and chill?

What if winds be harsh and stale?

Presently the east will thrill,

And the sad and shrunken sail,

Bellying with a kindly gale,

Bear you sunwards, while your chance

Sends you back the hopeful hail:—

‘Fate’s a fiddler, Life’s a dance.’

p.

92Idle shot or coming bill,

Hapless love or broken bail,

Gulp it (never chew your pill!),

And, if Burgundy should fail,

Try the humbler pot of ale!

Over all is heaven’s expanse.

Gold’s to find among the shale.

Fate’s a fiddler, Life’s a dance.

Dull Sir Joskin sleeps his fill,

Good Sir Galahad seeks the Grail,

Proud Sir Pertinax flaunts his frill,

Hard Sir Æger dints his mail;

And the while by hill and dale

Tristram’s braveries gleam and glance,

And his blithe horn tells its tale:—

‘Fate’s a fiddler, Life’s a dance.’

Araminta’s grand and shrill,

Delia’s passionate and frail,

Doris drives an earnest quill,

Athanasia takes the veil:

Wiser Phyllis o’er her pail,

At the heart of all romance

p. 93Reading,

sings to Strephon’s flail:—

‘Fate’s a fiddler, Life’s a dance.’

Every Jack must have his Jill

(Even Johnson had his Thrale!):

Forward, couples—with a will!

This, the world, is not a jail.

Hear the music, sprat and whale!

Hands across, retire, advance!

Though the doomsman’s on your trail,

Fate’s a fiddler, Life’s a dance.

Envoy

Boys and girls, at slug and snail

And their kindred look askance.

Pay your footing on the nail:

Fate’s a fiddler, Life’s a dance.

The big teetotum

twirls,

And epochs wax and wane

As chance subsides or swirls;

But of the loss and gain

The sum is always plain.

Read on the mighty pall,

The weed of funeral

That covers praise and blame,

The —isms and the —anities,

Magnificence and shame:—

‘O Vanity of Vanities!’

The Fates are subtile girls!

They give us chaff for grain.

And Time, the Thunderer, hurls,

Like bolted death, disdain

At all that heart and brain

Conceive, or great or small,

p. 95Upon this

earthly ball.

Would you be knight and dame?

Or woo the sweet humanities?

Or illustrate a name?

O Vanity of Vanities!

We sound the sea for pearls,

Or drown them in a drain;

We flute it with the merles,

Or tug and sweat and strain;

We grovel, or we reign;

We saunter, or we brawl;

We answer, or we call;

We search the stars for Fame,

Or sink her subterranities;

The legend’s still the same:—

‘O Vanity of Vanities!’

Here at the wine one birls,

There some one clanks a chain.

The flag that this man furls

That man to float is fain.

Pleasure gives place to pain:

These in the kennel crawl,

p. 96While

others take the wall.

She has a glorious aim,

He lives for the inanities.

What comes of every claim?

O Vanity of Vanities!

Alike are clods and earls.

For sot, and seer, and swain,

For emperors and for churls,

For antidote and bane,

There is but one refrain:

But one for king and thrall,

For David and for Saul,

For fleet of foot and lame,

For pieties and profanities,

The picture and the frame:—

‘O Vanity of Vanities!’

Life is a smoke that curls—

Curls in a flickering skein,

That winds and whisks and whirls

A figment thin and vain,

Into the vast Inane.

One end for hut and hall!

p. 97One end

for cell and stall!

Burned in one common flame

Are wisdoms and insanities.

For this alone we came:—

‘O Vanity of Vanities!’

Envoy

Prince, pride must have a fall.

What is the worth of all

Your state’s supreme urbanities?

Bad at the best’s the game.

Well might the Sage exclaim:—

‘O Vanity of Vanities!’

To W. G. S.

The blackbird sang,

the skies were clear and clean

We bowled along a road that curved a spine

Superbly sinuous and serpentine

Thro’ silent symphonies of summer green.

Sudden the Forth came on us—sad of mien,

No cloud to colour it, no breeze to line:

A sheet of dark, dull glass, without a sign

Of life or death, two spits of sand between.

Water and sky merged blank in mist together,

The Fort loomed spectral, and the Guardship’s spars

Traced vague, black shadows on the shimmery glaze:

We felt the dim, strange years, the grey, strange weather,

The still, strange land, unvexed of sun or stars,

Where Lancelot rides clanking thro’ the haze.

She’s an

enchanting little Israelite,

A world of hidden dimples!—Dusky-eyed,

A starry-glancing daughter of the Bride,

With hair escaped from some Arabian Night,

Her lip is red, her cheek is golden-white,

Her nose a scimitar; and, set aside

The bamboo hat she cocks with so much pride,

Her dress a dream of daintiness and delight.

And when she passes with the dreadful boys

And romping girls, the cockneys loud and crude,

My thought, to the Minories tied yet moved to range

The Land o’ the Sun, commingles with the noise

Of magian drums and scents of sandalwood

A touch Sidonian—modern—taking—strange!

A hard north-easter

fifty winters long

Has bronzed and shrivelled sere her face and neck;

Her locks are wild and grey, her teeth a wreck;

Her foot is vast, her bowed leg spare and strong.

A wide blue cloak, a squat and sturdy throng

Of curt blue coats, a mutch without a speck,

A white vest broidered black, her person deck,

Nor seems their picked, stern, old-world quaintness wrong.

Her great creel forehead-slung, she wanders nigh,

Easing the heavy strap with gnarled, brown fingers,

The spirit of traffic watchful in her eye,

Ever and anon imploring you to buy,

As looking down the street she onward lingers,

Reproachful, with a strange and doleful cry.

To D. F.

I watched you

saunter down the sand:

Serene and large, the golden weather

Flowed radiant round your peacock feather,

And glistered from your jewelled hand.

Your tawny hair, turned strand on strand

And bound with blue ribands together,

Streaked the rough tartan, green like heather,

That round your lissome shoulder spanned.

Your grace was quick my sense to seize:

The quaint looped hat, the twisted tresses,

The close-drawn scarf, and under these

The flowing, flapping draperies—

My thought an outline still caresses,

Enchanting, comic, Japanese!

To G. W.

The beach was

crowded. Pausing now and then,

He groped and fiddled doggedly along,

His worn face glaring on the thoughtless throng

The stony peevishness of sightless men.

He seemed scarce older than his clothes. Again,

Grotesquing thinly many an old sweet song,

So cracked his fiddle, his hand so frail and wrong,

You hardly could distinguish one in ten.

He stopped at last, and sat him on the sand,

And, grasping wearily his bread-winner,

Stared dim towards the blue immensity,

Then leaned his head upon his poor old hand.

He may have slept: he did not speak nor stir:

His gesture spoke a vast despondency.

To A. J.

A black and glassy

float, opaque and still,

The loch, at furthest ebb supine in sleep,

Reversing, mirrored in its luminous deep

The calm grey skies; the solemn spurs of hill;

Heather, and corn, and wisps of loitering haze;

The wee white cots, black-hatted, plumed with smoke;

The braes beyond—and when the ripple awoke,

They wavered with the jarred and wavering glaze.

The air was hushed and dreamy. Evermore

A noise of running water whispered near.

A straggling crow called high and thin. A bird

Trilled from the birch-leaves. Round the shingled shore,

Yellow with weed, there wandered, vague and clear,

Strange vowels, mysterious gutturals, idly heard.

To M. M. M‘B.

Above the Crags that

fade and gloom

Starts the bare knee of Arthur’s Seat;

Ridged high against the evening bloom,

The Old Town rises, street on street;

With lamps bejewelled, straight ahead,

Like rampired walls the houses lean,

All spired and domed and turreted,

Sheer to the valley’s darkling green;

Ranged in mysterious disarray,

The Castle, menacing and austere,

Looms through the lingering last of day;

And in the silver dusk you hear,

Reverberated from crag and scar,

Bold bugles blowing points of war.

To Garryowen

upon an organ ground

Two girls are jigging. Riotously they trip,

With eyes aflame, quick bosoms, hand on hip,

As in the tumult of a witches’ round.

Youngsters and youngsters round them prance and bound.

Two solemn babes twirl ponderously, and skip.

The artist’s teeth gleam from his bearded lip.

High from the kennel howls a tortured hound.

The music reels and hurtles, and the night

Is full of stinks and cries; a naphtha-light

Flares from a barrow; battered and obtused

With vices, wrinkles, life and work and rags,

Each with her inch of clay, two loitering hags

Look on dispassionate—critical—something

’mused.

The gods are

dead? Perhaps they are! Who knows?

Living at least in Lemprière undeleted,

The wise, the fair, the awful, the jocose,

Are one and all, I like to think, retreated

In some still land of lilacs and the rose.

Once higeh they sat, and high o’er

earthly shows

With sacrificial dance and song were greeted.

Once . . . long ago. But now, the story goes,

The gods are dead.

It must be true. The world, a world of

prose,

Full-crammed with facts, in science swathed and sheeted,

Nods in a stertorous after-dinner doze!

Plangent and sad, in every wind that blows

Who will may hear the sorry words repeated:—

‘The Gods are Dead!’

Let us be drunk, and

for a while forget,

Forget, and, ceasing even from regret,

Live without reason and despite of rhyme,

As in a dream preposterous and sublime,

Where place and hour and means for once are met.

Where is the use of effort? Love and

debt

And disappointment have us in a net.

Let us break out, and taste the morning prime . . .

Let us be drunk.

In vain our little hour we strut and fret,

And mouth our wretched parts as for a bet:

We cannot please the tragicaster Time.

To gain the crystal sphere, the silver dime,

Where Sympathy sits dimpling on us yet,

Let us be drunk!

When you are old,

and I am passed away—

Passed, and your face, your golden face, is gray—

I think, whate’er the end, this dream of mine,

Comforting you, a friendly star will shine

Down the dim slope where still you stumble and stray.

So may it be: that so dead Yesterday,

No sad-eyed ghost but generous and gay,

May serve you memories like almighty wine,

When you are old!

Dear Heart, it shall be so. Under the

sway

Of death the past’s enormous disarray

Lies hushed and dark. Yet though there come no sign,

Live on well pleased: immortal and divine

Love shall still tend you, as God’s angels may,

When you are old.

Beside the idle

summer sea

And in the vacant summer days,

Light Love came fluting down the ways,

Where you were loitering with me.

Who has not welcomed, even as we,

That jocund minstrel and his lays

Beside the idle summer sea

And in the vacant summer days?

We listened, we were fancy-free;

And lo! in terror and amaze

We stood alone—alone at gaze