The Project Gutenberg eBook, Essays in Little, by Andrew Lang, Edited by W. H. Davenport Adams This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Essays in Little Author: Andrew Lang Editor: W. H. Davenport Adams Release Date: December 29, 2007 [eBook #1594] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-646-US (US-ASCII) ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ESSAYS IN LITTLE***

Transcribed from the 1891 Henry and Co. edition by David Price, email ccx074@pglaf.org

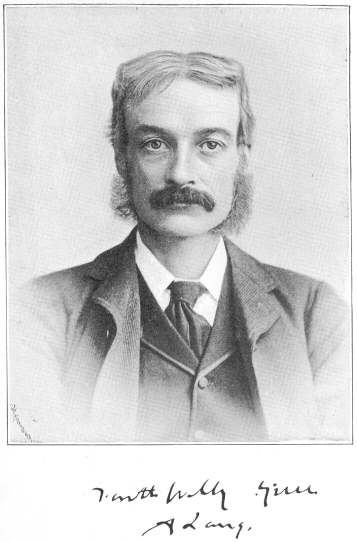

by

ANDREW LANG.

with portrait of the author.

london:

HENRY AND CO., BOUVERIE STREET, E.C.

1891.

Printed by Hazell, Watson, & Vincy, Ld., London and Aylesbury.

CONTENTS.

Preface

Alexandre Dumas

Mr. Stevenson’s works

Thomas Haynes Bayly

Théodore de Banville

Homer and the Study of Greek

The Last Fashionable Novel

Thackeray

Dickens

Adventures of Buccaneers

The Sagas

Charles Kingsley

Charles Lever: His books, adventures and misfortunes

The poems of Sir Walter Scott

John Bunyan

To a Young Journalist

Mr. Kipling’s stories

Of the following essays, five are new, and were written for this volume. They are the paper on Mr. R. L. Stevenson, the “Letter to a Young Journalist,” the study of Mr. Kipling, the note on Homer, and “The Last Fashionable Novel.” The article on the author of “Oh, no! we never mention Her,” appeared in the New York Sun, and was suggested by Mr. Dana, the editor of that journal. The papers on Thackeray and Dickens were published in Good Words, that on Dumas appeared in Scribner’s Magazine, that on M. Théodore de Banville in The New Quarterly Review. The other essays were originally written for a newspaper “Syndicate.” They have been re-cast, augmented, and, to a great extent, re-written.

A. L.

Alexandre Dumas is a writer, and his life is a topic, of which his devotees never weary. Indeed, one lifetime is not long enough wherein to tire of them. The long days and years of Hilpa and Shalum, in Addison—the antediluvian age, when a picnic lasted for half a century and a courtship for two hundred years, might have sufficed for an exhaustive study of Dumas. No such study have I to offer, in the brief seasons of our perishable days. I own that I have not read, and do not, in the circumstances, expect to read, all of Dumas, nor even the greater part of his thousand volumes. We only dip a cup in that sparkling spring, and drink, and go on,—we cannot hope to exhaust the fountain, nor to carry away with us the well itself. It is but a word of gratitude and delight that we can say to the heroic and indomitable master, only an ave of friendship that we can call across the bourne to the shade of the Porthos of fiction. That his works (his best works) should be even still more widely circulated than they are; that the young should read them, and learn frankness, kindness, generosity—should esteem the tender heart, and the gay, invincible wit; that the old should read them again, and find forgetfulness of trouble, and taste the anodyne of dreams, that is what we desire.

Dumas said of himself (“Mémoires,” v. 13) that when he was young he tried several times to read forbidden books—books that are sold sous le manteau. But he never got farther than the tenth page, in the

“scrofulous French novel

On gray paper with blunt type;”

he never made his way so far as

“the woful sixteenth print.”

“I had, thank God, a natural sentiment of delicacy; and thus, out of my six hundred volumes (in 1852) there are not four which the most scrupulous mother may not give to her daughter.” Much later, in 1864, when the Censure threatened one of his plays, he wrote to the Emperor: “Of my twelve hundred volumes there is not one which a girl in our most modest quarter, the Faubourg Saint-Germain, may not be allowed to read.” The mothers of the Faubourg, and mothers in general, may not take Dumas exactly at his word. There is a passage, for example, in the story of Miladi (“Les Trois Mousquetaires”) which a parent or guardian may well think undesirable reading for youth. But compare it with the original passage in the “Mémoires” of D’Artagnan! It has passed through a medium, as Dumas himself declared, of natural delicacy and good taste. His enormous popularity, the widest in the world of letters, owes absolutely nothing to prurience or curiosity. The air which he breathes is a healthy air, is the open air; and that by his own choice, for he had every temptation to seek another kind of vogue, and every opportunity.

Two anecdotes are told of Dumas’ books, one by M. Edmond About, the other by his own son, which show, in brief space, why this novelist is so beloved, and why he deserves our affection and esteem. M. Villaud, a railway engineer who had lived much in Italy, Russia, and Spain, was the person whose enthusiasm finally secured a statue for Dumas. He felt so much gratitude to the unknown friend of lonely nights in long exiles, that he could not be happy till his gratitude found a permanent expression. On returning to France he went to consult M. Victor Borie, who told him this tale about George Sand. M. Borie chanced to visit the famous novelist just before her death, and found Dumas’ novel, “Les Quarante Cinq” (one of the cycle about the Valois kings) lying on her table. He expressed his wonder that she was reading it for the first time.

“For the first time!—why, this is the fifth or sixth time I have read ‘Les Quarante Cinq,’ and the others. When I am ill, anxious, melancholy, tired, discouraged, nothing helps me against moral or physical troubles like a book of Dumas.” Again, M. About says that M. Sarcey was in the same class at school with a little Spanish boy. The child was homesick; he could not eat, he could not sleep; he was almost in a decline.

“You want to see your mother?” said young Sarcey.

“No: she is dead.”

“Your father, then?”

“No: he used to beat me.”

“Your brothers and sisters?”

“I have none.”

“Then why are you so eager to be back in Spain?”

“To finish a book I began in the holidays.”

“And what was its name?”

“‘Los Tres Mosqueteros’!”

He was homesick for “The Three Musketeers,” and they cured him easily.

That is what Dumas does. He gives courage and life to old age, he charms away the half-conscious nostalgie, the Heimweh, of childhood. We are all homesick, in the dark days and black towns, for the land of blue skies and brave adventures in forests, and in lonely inns, on the battle-field, in the prison, on the desert isle. And then Dumas comes, and, like Argive Helen, in Homer, he casts a drug into the wine, the drug nepenthe, “that puts all evil out of mind.” Does any one suppose that when George Sand was old and tired, and near her death, she would have found this anodyne, and this stimulant, in the novels of M. Tolstoï, M. Dostoiefsky, M. Zola, or any of the “scientific” observers whom we are actually requested to hail as the masters of a new art, the art of the future? Would they make her laugh, as Chicot does? make her forget, as Porthos, Athos, and Aramis do? take her away from the heavy, familiar time, as the enchanter Dumas takes us? No; let it be enough for these new authors to be industrious, keen, accurate, précieux, pitiful, charitable, veracious; but give us high spirits now and then, a light heart, a sharp sword, a fair wench, a good horse, or even that old Gascon rouncy of D’Artagnan’s. Like the good Lord James Douglas, we had liefer hear the lark sing over moor and down, with Chicot, than listen to the starved-mouse squeak in the bouge of Thérèse Raquin, with M. Zola. Not that there is not a place and an hour for him, and others like him; but they are not, if you please, to have the whole world to themselves, and all the time, and all the praise; they are not to turn the world into a dissecting-room, time into tedium, and the laurels of Scott and Dumas into crowns of nettles.

There is no complete life of Alexandre Dumas. The age has not produced the intellectual athlete who can gird himself up for that labour. One of the worst books that ever was written, if it can be said to be written, is, I think, the English attempt at a biography of Dumas. Style, grammar, taste, feeling, are all bad. The author does not so much write a life as draw up an indictment. The spirit of his work is grudging, sneering, contemptuous, and pitifully peddling. The great charge is that Dumas was a humbug, that he was not the author of his own books, that his books were written by “collaborators”—above all, by M. Maquet. There is no doubt that Dumas had a regular system of collaboration, which he never concealed. But whereas Dumas could turn out books that live, whoever his assistants were, could any of his assistants write books that live, without Dumas? One might as well call any barrister in good practice a thief and an impostor because he has juniors to “devil” for him, as make charges of this kind against Dumas. He once asked his son to help him; the younger Alexandre declined. “It is worth a thousand a year, and you have only to make objections,” the sire urged; but the son was not to be tempted. Some excellent novelists of to-day would be much better if they employed a friend to make objections. But, as a rule, the collaborator did much more. Dumas’ method, apparently, was first to talk the subject over with his aide-de-camp. This is an excellent practice, as ideas are knocked out, like sparks (an elderly illustration!), by the contact of minds. Then the young man probably made researches, put a rough sketch on paper, and supplied Dumas, as it were, with his “brief.” Then Dumas took the “brief” and wrote the novel. He gave it life, he gave it the spark (l’étincelle); and the story lived and moved.

It is true that he “took his own where he found it,” like Molère and that he took a good deal. In the gallery of an old country-house, on a wet day, I came once on the “Mémoires” of D’Artagnan, where they had lain since the family bought them in Queen Anne’s time. There were our old friends the Musketeers, and there were many of their adventures, told at great length and breadth. But how much more vivacious they are in Dumas! M. About repeats a story of Dumas and his ways of work. He met the great man at Marseilles, where, indeed, Alexandre chanced to be “on with the new love” before being completely “off with the old.” Dumas picked up M. About, literally lifted him in his embrace, and carried him off to see a play which he had written in three days. The play was a success; the supper was prolonged till three in the morning; M. About was almost asleep as he walked home, but Dumas was as fresh as if he had just got out of bed. “Go to sleep, old man,” he said: “I, who am only fifty-five, have three feuilletons to write, which must be posted to-morrow. If I have time I shall knock up a little piece for Montigny—the idea is running in my head.” So next morning M. About saw the three feuilletons made up for the post, and another packet addressed to M. Montigny: it was the play L’Invitation à la Valse, a chef-d’oeuvre! Well, the material had been prepared for Dumas. M. About saw one of his novels at Marseilles in the chrysalis. It was a stout copy-book full of paper, composed by a practised hand, on the master’s design. Dumas copied out each little leaf on a big leaf of paper, en y semant l’esprit à pleines mains. This was his method. As a rule, in collaboration, one man does the work while the other looks on. Is it likely that Dumas looked on? That was not the manner of Dumas. “Mirecourt and others,” M. About says, “have wept crocodile tears for the collaborators, the victims of his glory and his talent. But it is difficult to lament over the survivors (1884). The master neither took their money—for they are rich, nor their fame—for they are celebrated, nor their merit—for they had and still have plenty. And they never bewailed their fate: the reverse! The proudest congratulate themselves on having been at so good a school; and M. Auguste Maquet, the chief of them, speaks with real reverence and affection of his great friend.” And M. About writes “as one who had taken the master red-handed, and in the act of collaboration.” Dumas has a curious note on collaboration in his “Souvenirs Dramatiques.” Of the two men at work together, “one is always the dupe, and he is the man of talent.”

There is no biography of Dumas, but the small change of a biography exists in abundance. There are the many volumes of his “Mémoires,” there are all the tomes he wrote on his travels and adventures in Africa, Spain, Italy, Russia; the book he wrote on his beasts; the romance of Ange Pitou, partly autobiographical; and there are plenty of little studies by people who knew him. As to his “Mémoires,” as to all he wrote about himself, of course his imagination entered into the narrative. Like Scott, when he had a good story he liked to dress it up with a cocked hat and a sword. Did he perform all those astonishing and innumerable feats of strength, skill, courage, address, in revolutions, in voyages, in love, in war, in cookery? The narrative need not be taken “at the foot of the letter”; great as was his force and his courage, his fancy was greater still. There is no room for a biography of him here. His descent was noble on one side, with or without the bend sinister, which he said he would never have disclaimed, had it been his, but which he did not happen to inherit. On the other side he may have descended from kings; but, as in the case of “The Fair Cuban,” he must have added, “African, unfortunately.” Did his father perform these mythical feats of strength? did he lift up a horse between his legs while clutching a rafter with his hands? did he throw his regiment before him over a wall, as Guy Heavistone threw the mare which refused the leap (“Mémoires,” i. 122)? No doubt Dumas believed what he heard about this ancestor—in whom, perhaps, one may see a hint of the giant Porthos. In the Revolution and in the wars his father won the name of Monsieur de l’Humanité, because he made a bonfire of a guillotine; and of Horatius Cocles, because he held a pass as bravely as the Roman “in the brave days of old.”

This was a father to be proud of; and pluck, tenderness, generosity, strength, remained the favourite virtues of Dumas. These he preached and practised. They say he was generous before he was just; it is to be feared this was true, but he gave even more freely than he received. A regiment of seedy people sponged on him always; he could not listen to a tale of misery but he gave what he had, and sometimes left himself short of a dinner. He could not even turn a dog out of doors. At his Abbotsford, “Monte Cristo,” the gates were open to everybody but bailiffs. His dog asked other dogs to come and stay: twelve came, making thirteen in all. The old butler wanted to turn them adrift, and Dumas consented, and repented.

“Michel,” he said, “there are some expenses which a man’s social position and the character which he has had the ill-luck to receive from heaven force upon him. I don’t believe these dogs ruin me. Let them bide! But, in the interests of their own good luck, see they are not thirteen, an unfortunate number!”

“Monsieur, I’ll drive one of them away.”

“No, no, Michel; let a fourteenth come. These dogs cost me some three pounds a month,” said Dumas. “A dinner to five or six friends would cost thrice as much, and, when they went home, they would say my wine was good, but certainly that my books were bad.” In this fashion Dumas fared royally “to the dogs,” and his Abbotsford ruined him as certainly as that other unhappy palace ruined Sir Walter. He, too, had his miscellaneous kennel; he, too, gave while he had anything to give, and, when he had nothing else, gave the work of his pen. Dumas tells how his big dog, Mouton once flew at him and bit one of his hands, while the other held the throat of the brute. “Luckily my hand, though small, is powerful; what it once holds it holds long—money excepted.” He could not “haud a guid grip o’ the gear.” Neither Scott nor Dumas could shut his ears to a prayer or his pockets to a beggar, or his doors on whoever knocked at them.

“I might at least have asked him to dinner,” Scott was heard murmuring, when some insufferable bore at last left Abbotsford, after wasting his time and nearly wearing out his patience. Neither man preached socialism; both practised it on the Aristotelian principle: the goods of friends are common, and men are our friends.

* * * * *

The death of Dumas’ father, while the son was a child, left Madame Dumas in great poverty at Villers Cotterets. Dumas’ education was sadly to seek. Like most children destined to be bookish, he taught himself to read very young: in Buffon, the Bible, and books of mythology. He knew all about Jupiter—like David Copperfield’s Tom Jones, “a child’s Jupiter, an innocent creature”—all about every god, goddess, fawn, dryad, nymph—and he never forgot this useful information. Dear Lemprière, thou art superseded; but how much more delightful thou art than the fastidious Smith or the learned Preller! Dumas had one volume of the “Arabian Nights,” with Aladdin’s lamp therein, the sacred lamp which he was to keep burning with a flame so brilliant and so steady. It is pleasant to know that, in his boyhood, this great romancer loved Virgil. “Little as is my Latin, I have ever adored Virgil: his tenderness for exiles, his melancholy vision of death, his foreboding of an unknown God, have always moved me; the melody of his verses charmed me most, and they lull me still between asleep and awake.” School days did not last long: Madame Dumas got a little post—a licence to sell tobacco—and at fifteen Dumas entered a notary’s office, like his great Scotch forerunner. He was ignorant of his vocation for the stage—Racine and Corneille fatigued him prodigiously—till he saw Hamlet: Hamlet diluted by Ducis. He had never heard of Shakespeare, but here was something he could appreciate. Here was “a profound impression, full of inexplicable emotion, vague desires, fleeting lights, that, so far, lit up only a chaos.”

Oddly enough, his earliest literary essay was the translation of Bürger’s “Lenore.” Here, again, he encounters Scott; but Scott translated the ballad, and Dumas failed. Les mortes vont vite! the same refrain woke poetry in both the Frenchman and the Scotchman.

“Ha! ha! the Dead can ride with speed:

Dost fear to ride with me?”

So Dumas’ literary career began with a defeat, but it was always a beginning. He had just failed with “Lenore,” when Leuven asked him to collaborate in a play. He was utterly ignorant, he says; he had not succeeded in gallant efforts to read through “Gil Blas” and “Don Quixote.” “To my shame,” he writes, “the man has not been more fortunate with those masterpieces than the boy.” He had not yet heard of Scott, Cooper, Goethe; he had heard of Shakespeare only as a barbarian. Other plays the boy wrote—failures, of course—and then Dumas poached his way to Paris, shooting partridges on the road, and paying the hotel expenses by his success in the chase. He was introduced to the great Talma: what a moment for Talma, had he known it! He saw the theatres. He went home, but returned to Paris, drew a small prize in a lottery, and sat next a gentleman at the play, a gentleman who read the rarest of Elzevirs, “Le Pastissier Français,” and gave him a little lecture on Elzevirs in general. Soon this gentleman began to hiss the piece, and was turned out. He was Charles Nodier, and one of the anonymous authors of the play he was hissing! I own that this amusing chapter lacks verisimilitude. It reads as if Dumas had chanced to “get up” the subject of Elzevirs, and had fashioned his new knowledge into a little story. He could make a story out of anything—he “turned all to favour and to prettiness.” Could I translate the whole passage, and print it here, it would be longer than this article; but, ah, how much more entertaining! For whatever Dumas did he did with such life, spirit, wit, he told it with such vivacity, that his whole career is one long romance of the highest quality. Lassagne told him he must read—must read Goethe, Scott, Cooper, Froissart, Joinville, Brantôme. He read them to some purpose. He entered the service of the Duc d’Orléans as a clerk, for he wrote a clear hand, and, happily, wrote at astonishing speed. He is said to have written a short play in a cottage where he went to rest for an hour or two after shooting all the morning. The practice in a notary’s office stood him, as it stood Scott, in good stead. When a dog bit his hand he managed to write a volume without using his thumb. I have tried it, but forbear—in mercy to the printers. He performed wild feats of rapid caligraphy when a clerk under the Duc d’Orléans, and he wrote his plays in one “hand,” his novels in another. The “hand” used in his dramas he acquired when, in days of poverty, he used to write in bed. To this habit he also attributed the brutalité of his earlier pieces, but there seems to be no good reason why a man should write like a brute because it is in bed that he writes.

In those days of small things he fought his first duel, and made a study of Fear and Courage. His earliest impulse was to rush at danger; if he had to wait, he felt his courage oozing out at the tips of his fingers, like Bob Acres, but in the moment of peril he was himself again. In dreams he was a coward, because, as he argues, the natural man is a poltroon, and conscience, honour, all the spiritual and commanding part of our nature, goes to sleep in dreams. The animal terror asserts itself unchecked. It is a theory not without exceptions. In dreams one has plenty of conscience (at least that is my experience), though it usually takes the form of remorse. And in dreams one often affronts dangers which, in waking hours, one might probably avoid if one could.

* * * * *

Dumas’ first play, an unimportant vaudeville, was acted in 1825. His first novels were also published then; he took part of the risk, and only four copies were sold. He afterward used the ideas in more mature works, as Mr. Sheridan Le Fanu employed three or four times (with perfect candour and fairness) the most curious incident in “Uncle Silas.” Like Mr. Arthur Pendennis, Dumas at this time wrote poetry “up to” pictures and illustrations. It is easy, but seldom lucrative work. He translated a play of Schiller’s into French verse, chiefly to gain command of that vehicle, for his heart was fixed on dramatic success. Then came the visit of Kean and other English actors to Paris. He saw the true Hamlet, and, for the first time on any stage, “the play of real passions.” Emulation woke in him: a casual work of art led him to the story of Christina of Sweden, he wrote his play Christine (afterward reconstructed); he read it to Baron Taylor, who applauded; the Comédie Française accepted it, but a series of intrigues disappointed him, after all. His energy at this moment was extraordinary, for he was very poor, his mother had a stroke of paralysis, his bureau was always bullying and interfering with him. But nothing could snub this “force of nature,” and he immediately produced his Henri Trois, the first romantic drama of France. This had an instant and noisy success, and the first night of the play he spent at the theatre, and at the bedside of his unconscious mother. The poor lady could not even understand whence the flowers came that he laid on her couch, the flowers thrown to the young man—yesterday unknown, and to-day the most famous of contemporary names. All this tale of triumph, checkered by enmities and diversified by duels, Dumas tells with the vigour and wit of his novels. He is his own hero, and loses nothing in the process; but the other characters—Taylor, Nodier, the Duc d’Orléans, the spiteful press-men, the crabbed old officials—all live like the best of the persons in his tales. They call Dumas vain: he had reason to be vain, and no candid or generous reader will be shocked by his pleasant, frank, and artless enjoyment of himself and of his adventures. Oddly enough, they are small-minded and small-hearted people who are most shocked by what they call “vanity” in the great. Dumas’ delight in himself and his doings is only the flower of his vigorous existence, and in his “Mémoires,” at least, it is as happy and encouraging as his laugh, or the laugh of Porthos; it is a kind of radiance, in which others, too, may bask and enjoy themselves. And yet it is resented by tiny scribblers, frozen in their own chill self-conceit.

There is nothing incredible (if modern researches are accurate) in the stories he tells of his own success in Hypnotism, as it is called now, Mesmerism or Magnetism as it was called then. Who was likely to possess these powers, if not this good-humoured natural force? “I believe that, by aid of magnetism, a bad man might do much mischief. I doubt whether, by help of magnetism, a good man can do the slightest good,” he says, probably with perfect justice. His dramatic success fired Victor Hugo, and very pleasant it is to read Dumas’ warm-hearted praise of that great poet. Dumas had no jealousy—no more than Scott. As he believed in no success without talent, so he disbelieved in genius which wins no success. “Je ne crois pas au talent ignoré, au génie inconnu, moi.” Genius he saluted wherever he met it, but was incredulous about invisible and inaudible genius; and I own to sharing his scepticism. People who complain of Dumas’ vanity may be requested to observe that he seems just as “vain” of Hugo’s successes, or of Scribe’s, as of his own, and just as much delighted by them.

He was now struck, as he walked on the boulevard one day, by the first idea of Antony—an idea which, to be fair, seems rather absurd than tragic, to some tastes. “A lover, caught with a married woman, kills her to save her character, and dies on the scaffold.” Here is indeed a part to tear a cat in!

* * * * *

The performances of M. Dumas during the Revolution of 1830, are they not written in the Book of the Chronicles of Alexandre the Great? But they were not literary excellences which he then displayed, and we may leave this king-maker to hover, “like an eagle, above the storms of anarchy.”

Even to sketch his later biography is beyond our province. In 1830 he had forty years to run, and he filled the cup of the Hours to the brim with activity and adventure. His career was one of unparalleled production, punctuated by revolutions, voyages, exiles, and other intervals of repose. The tales he tells of his prowess in 1830, and with Garibaldi, seem credible to me, and are borne out, so far, by the narrative of M. Maxime Ducamp, who met him at Naples, in the Garibaldian camp. Like Mr. Jingle, in “Pickwick,” he “banged the field-piece, twanged the lyre,” and was potting at the foes of the republic with a double-barrelled gun, when he was not composing plays, romances, memoirs, criticisms. He has told the tale of his adventures with the Comédie Française, where the actors laughed at his Antony, and where Madame Mars and he quarrelled and made it up again. His plays often won an extravagant success; his novels—his great novels, that is—made all Europe his friend. He gained large sums of money, which flowed out of his fingers, though it is said by some that his Abbotsford, Monte Cristo, was no more a palace than the villa which a retired tradesman builds to shelter his old age. But the money disappeared as fast as if Monte Cristo had really been palatial, and worthy of the fantasy of a Nero. He got into debt, fled to Belgium, returned, founded the Mousquetaire, a literary paper of the strangest and most shiftless kind. In “Alexandre Dumas à la Maison d’Or,” M. Philibert Audebrand tells the tale of this Micawber of newspapers. Everything went into it, good or bad, and the name of Dumas was expected to make all current coin. For Dumas, unluckily, was as prodigal of his name as of his gold, and no reputation could bear the drafts he made on his celebrity. His son says, in the preface to Le Fils Naturel: “Tragedy, dramas, history, romance, comedy, travel, you cast all of them in the furnace and the mould of your brain, and you peopled the world of fiction with new creations. The newspaper, the book, the theatre, burst asunder, too narrow for your puissant shoulders; you fed France, Europe, America with your works; you made the wealth of publishers, translators, plagiarists; printers and copyists toiled after you in vain. In the fever of production you did not always try and prove the metal which you employed, and sometimes you tossed into the furnace whatever came to your hand. The fire made the selection: what was your own is bronze, what was not yours vanished in smoke.”

The simile is noble and worthy of the Cyclopean craftsman, Dumas. His great works endured; the plays which renewed the youth of the French stage, the novels which Thackeray loved to praise, these remain, and we trust they may always remain, to the delight of mankind and for the sorrow of prigs.

* * * * *

So much has been written of Dumas’ novels that criticism can hardly hope to say more that is both new and true about them. It is acknowledged that, in such a character as Henri III., Dumas made history live, as magically as Scott revived the past in his Louis XI., or Balfour of Burley. It is admitted that Dumas’ good tales are told with a vigour and life which rejoice the heart; that his narrative is never dull, never stands still, but moves with a freedom of adventure which perhaps has no parallel. He may fall short of the humour, the kindly wisdom, the genial greatness of Sir Walter at his best, and he has not that supernatural touch, that tragic grandeur, which Scott inherits from Homer and from Shakespeare. In another Homeric quality, χαρyη, as Homer himself calls it, in the “delight of battle” and the spirit of the fray, Scott and Dumas are alike masters. Their fights and the fights in the Icelandic sagas are the best that have ever been drawn by mortal man. When swords are aloft, in siege or on the greensward, or in the midnight chamber where an ambush is laid, Scott and Dumas are indeed themselves. The steel rings, the bucklers clash, the parry and lunge pass and answer too swift for the sight. If Dumas has not, as he certainly has not, the noble philosophy and kindly knowledge of the heart which are Scott’s, he is far more swift, more witty, more diverting. He is not prolix, his style is not involved, his dialogue is as rapid and keen as an assault at arms. His favourite virtues and graces, we repeat it, are loyalty, friendship, gaiety, generosity, courage, beauty, and strength. He is himself the friend of the big, stupid, excellent Porthos; of Athos, the noble and melancholy swordsman of sorrow; of D’Artagnan, the indomitable, the trusty, the inexhaustible in resource; but his heart is never on the side of the shifty Aramis, with all his beauty, dexterity, bravery, and brilliance. The brave Bussy, and the chivalrous, the doomed La Mole, are more dear to him; and if he embellishes their characters, giving them charms and virtues that never were theirs, history loses nothing, and romance and we are the gainers. In all he does, at his best, as in the “Chevalier d’Harmenthal,” he has movement, kindness, courage, and gaiety. His philosophy of life is that old philosophy of the sagas and of Homer. Let us enjoy the movement of the fray, the faces of fair women, the taste of good wine; let us welcome life like a mistress, let us welcome death like a friend, and with a jest—if death comes with honour.

Dumas is no pessimist. “Heaven has made but one drama for man—the world,” he writes, “and during these three thousand years mankind has been hissing it.” It is certain that, if a moral censorship could have prevented it, this great drama of mortal passions would never have been licensed, at all, never performed. But Dumas, for one, will not hiss it, but applauds with all his might—a charmed spectator, a fortunate actor in the eternal piece, where all the men and women are only players. You hear his manly laughter, you hear his mighty hands approving, you see the tears he sheds when he had “slain Porthos”—great tears like those of Pantagruel.

* * * * *

His may not be the best, nor the ultimate philosophy, but it is a philosophy, and one of which we may some day feel the want. I read the stilted criticisms, the pedantic carpings of some modern men who cannot write their own language, and I gather that Dumas is out of date. There is a new philosophy of doubts and delicacies, of dallyings and refinements, of half-hearted lookers-on, desiring and fearing some new order of the world. Dumas does not dally nor doubt: he takes his side, he rushes into the smoke, he strikes his foe; but there is never an unkind word on his lip, nor a grudging thought in his heart.

It may be said that Dumas is not a master of words and phrases, that he is not a raffiné of expression, nor a jeweller of style. When I read the maunderings, the stilted and staggering sentences, the hesitating phrases, the far-sought and dear-bought and worthless word-juggles; the sham scientific verbiage, the native pedantries of many modern so-called “stylists,” I rejoice that Dumas was not one of these. He told a plain tale, in the language suited to a plain tale, with abundance of wit and gaiety, as in the reflections of his Chicot, as in all his dialogues. But he did not gnaw the end of his pen in search of some word that nobody had ever used in this or that connection before. The right word came to him, the simple straightforward phrase. Epithet-hunting may be a pretty sport, and the bag of the epithet-hunter may contain some agreeable epigrams and rare specimens of style; but a plain tale of adventure, of love and war, needs none of this industry, and is even spoiled by inopportune diligence. Speed, directness, lucidity are the characteristics of Dumas’ style, and they are exactly the characteristics which his novels required. Scott often failed, his most loyal admirers may admit, in these essentials; but it is rarely that Dumas fails, when he is himself and at his best.

* * * * *

In spite of his heedless education, Dumas had true critical qualities, and most admired the best things. We have already seen how he writes about Shakespeare, Virgil, Goethe, Scott. But it may be less familiarly known that this burly man-of-all-work, ignorant as he was of Greek, had a true and keen appreciation of Homer. Dumas declares that he only thrice criticised his contemporaries in an unfavourable sense, and as one wishful to find fault. The victims were Casimir Delavigne, Scribe, and Ponsard. On each occasion Dumas declares that, after reflecting, he saw that he was moved by a little personal pique, not by a disinterested love of art. He makes his confession with a rare nobility of candour; and yet his review of Ponsard is worthy of him. M. Ponsard, who, like Dumas, was no scholar, wrote a play styled Ulysse, and borrowed from the Odyssey. Dumas follows Ponsard, Odyssey in hand, and while he proves that the dramatist failed to understand Homer, proves that he himself was, in essentials, a capable Homeric critic. Dumas understands that far-off heroic age. He lives in its life and sympathises with its temper. Homer and he are congenial; across the great gulf of time they exchange smiles and a salute.

“Oh! ancient Homer, dear and good and noble, I am minded now and again to leave all and translate thee—I, who have never a word of Greek—so empty and so dismal are the versions men make of thee, in verse or in prose.”

How Dumas came to divine Homer, as it were, through a language he knew not, who shall say? He did divine him by a natural sympathy of excellence, and his chapters on the “Ulysse” of Ponsard are worth a wilderness of notes by learned and most un-Homeric men. For, indeed, who can be less like the heroic minstrel than the academic philologist?

This universality deserves note. The Homeric student who takes up a volume of Dumas at random finds that he is not only Homeric naturally, but that he really knows his Homer. What did he nor know? His rapidity in reading must have been as remarkable as his pace with the pen. As M. Blaze de Bury says: “Instinct, experience, memory were all his; he sees at a glance, he compares in a flash, he understands without conscious effort, he forgets nothing that he has read.” The past and present are photographed imperishably on his brain, he knows the manners of all ages and all countries, the names of all the arms that men have used, all the garments they have worn, all the dishes they have tasted, all the terms of all professions, from swordsmanship to coach-building. Other authors have to wait, and hunt for facts; nothing stops Dumas: he knows and remembers everything. Hence his rapidity, his facility, his positive delight in labour: hence it came that he might be heard, like Dickens, laughing while he worked.

* * * * *

This is rather a eulogy than a criticism of Dumas. His faults are on the surface, visible to all men. He was not only rapid, he was hasty, he was inconsistent; his need of money as well as his love of work made him put his hand to dozens of perishable things. A beginner, entering the forest of Dumas’ books, may fail to see the trees for the wood. He may be counselled to select first the cycle of d’Artagnan—the “Musketeers,” “Twenty Years After,” and the “Vicomte de Bragelonne.” Mr. Stevenson’s delightful essay on the last may have sent many readers to it; I confess to preferring the youth of the “Musketeers” to their old age. Then there is the cycle of the Valois, whereof the “Dame de Monsereau” is the best—perhaps the best thing Dumas ever wrote. The “Tulipe Noire” is a novel girls may read, as Thackeray said, with confidence. The “Chevalier d’Harmenthal” is nearly (not quite) as good as “Quentin Durward.” “Monte Cristo” has the best beginning—and loses itself in the sands. The novels on the Revolution are not among the most alluring: the famed device “L. P. D.” (lilia pedibus destrue) has the bad luck to suggest “London Parcels Delivery.” That is an accident, but the Revolution is in itself too terrible and pitiful, and too near us (on both sides!) for fiction.

On Dumas’ faults it has been no pleasure to dwell. In a recent work I find the Jesuit Le Moyne quoted, saying about Charles V.: “What need that future ages should be made acquainted so religious an Emperor was not always chaste!” The same reticence allures one in regard to so delightful an author as Dumas. He who had enriched so many died poor; he who had told of conquering France, died during the Terrible Year. But he could forgive, could appreciate, the valour of an enemy. Of the Scotch at Waterloo he writes: “It was not enough to kill them: we had to push them down.” Dead, they still stood “shoulder to shoulder.” In the same generous temper an English cavalry officer wrote home, after Waterloo, that he would gladly have given the rest of his life to have served, on that day, in our infantry or in the French cavalry. These are the spirits that warm the heart, that make us all friends; and to the great, the brave, the generous Dumas we cry, across the years and across the tomb, our Ave atque vale!

Perhaps the first quality in Mr. Stevenson’s works, now so many and so various, which strikes a reader, is the buoyancy, the survival of the child in him. He has told the world often, in prose and verse, how vivid are his memories of his own infancy. This retention of childish recollections he shares, no doubt, with other people of genius: for example, with George Sand, whose legend of her own infancy is much more entertaining, and perhaps will endure longer, than her novels. Her youth, like Scott’s and like Mr. Stevenson’s, was passed all in fantasy: in playing at being some one else, in the invention of imaginary characters, who were living to her, in the fabrication of endless unwritten romances. Many persons, who do not astonish the world by their genius, have lived thus in their earliest youth. But, at a given moment, the fancy dies out of them: this often befalls imaginative boys in their first year at school. “Many are called, few chosen”; but it may be said with probable truth, that there has never been a man of genius in letters, whose boyhood was not thus fantastic, “an isle of dreams.” We know how Scott and De Quincey inhabited airy castles; and Gillies tells us, though Lockhart does not, that Scott, in manhood, was occasionally so lost in thought, that he knew not where he was nor what he was doing.

The peculiarity of Mr. Stevenson is not only to have been a fantastic child, and to retain, in maturity, that fantasy ripened into imagination: he has also kept up the habit of dramatising everything, of playing, half consciously, many parts, of making the world “an unsubstantial fairy place.” This turn of mind it is that causes his work occasionally to seem somewhat freakish. Thus, in the fogs and horrors of London, he plays at being an Arabian tale-teller, and his “New Arabian Nights” are a new kind of romanticism—Oriental, freakish, like the work of a changeling. Indeed, this curious genius, springing from a family of Scottish engineers, resembles nothing so much as one of the fairy children, whom the ladies of Queen Proserpina’s court used to leave in the cradles of Border keeps or of peasants’ cottages. Of the Scot he has little but the power of touching us with a sense of the supernatural, and a decided habit of moralising; for no Scot of genius has been more austere with Robert Burns. On the other hand, one element of Mr. Stevenson’s ethical disquisitions is derived from his dramatic habit. His optimism, his gay courage, his habit of accepting the world as very well worth living in and looking at, persuaded one of his critics that he was a hard-hearted young athlete of iron frame. Now, of the athlete he has nothing but his love of the open air: it is the eternal child that drives him to seek adventures and to sojourn among beach-combers and savages. Thus, an admiring but far from optimistic critic may doubt whether Mr. Stevenson’s content with the world is not “only his fun,” as Lamb said of Coleridge’s preaching; whether he is but playing at being the happy warrior in life; whether he is not acting that part, himself to himself. At least, it is a part fortunately conceived and admirably sustained: a difficult part too, whereas that of the pessimist is as easy as whining.

Mr. Stevenson’s work has been very much written about, as it has engaged and delighted readers of every age, station, and character. Boys, of course, have been specially addressed in the books of adventure, children in “A Child’s Garden of Verse,” young men and maidens in “Virginibus Puerisque,”—all ages in all the curiously varied series of volumes. “Kidnapped” was one of the last books which the late Lord Iddesleigh read; and I trust there is no harm in mentioning the pleasure which Mr. Matthew Arnold took in the same story. Critics of every sort have been kind to Mr. Stevenson, in spite of the fact that the few who first became acquainted with his genius praised it with all the warmth of which they were masters. Thus he has become a kind of classic in his own day, for an undisputed reputation makes a classic while it lasts. But was ever so much fame won by writings which might be called scrappy and desultory by the advocatus diaboli? It is a most miscellaneous literary baggage that Mr. Stevenson carries. First, a few magazine articles; then two little books of sentimental journeyings, which convince the reader that Mr. Stevenson is as good company to himself as his books are to others. Then came a volume or two of essays, literary and social, on books and life. By this time there could be no doubt that Mr. Stevenson had a style of his own, modelled to some extent on the essayists of the last century, but with touches of Thackeray; with original breaks and turns, with a delicate freakishness, in short, and a determined love of saying things as the newspapers do not say them. All this work undoubtedly smelt a trifle of the lamp, and was therefore dear to some, and an offence to others. For my part, I had delighted in the essays, from the first that appeared in Macmillan’s Magazine, shortly after the Franco-German war. In this little study, “Ordered South,” Mr. Stevenson was employing himself in extracting all the melancholy pleasure which the Riviera can give to a wearied body and a mind resisting the clouds of early malady,

“Alas, the worn and broken board,

How can it bear the painter’s dye!

The harp of strained and tuneless chord,

How to the minstrel’s skill reply!

To aching eyes each landscape lowers,

To feverish pulse each gale blows chill,

And Araby’s or Eden’s bowers

Were barren as this moorland hill,”—

wrote Scott, in an hour of malady and depression. But this was not the spirit of “Ordered South”: the younger soul rose against the tyranny of the body; and that familiar glamour which, in illness, robs Tintoretto of his glow, did not spoil the midland sea to Mr. Stevenson. His gallant and cheery stoicism were already with him; and so perfect, if a trifle overstudied, was his style, that one already foresaw a new and charming essayist.

But none of those early works, nor the delightful book on Edinburgh, prophesied of the story teller. Mr. Stevenson’s first published tales, the “New Arabian Nights,” originally appeared in a quaintly edited weekly paper, which nobody read, or nobody but the writers in its columns. They welcomed the strange romances with rejoicings: but perhaps there was only one of them who foresaw that Mr. Stevenson’s forte was to be fiction, not essay writing; that he was to appeal with success to the large public, and not to the tiny circle who surround the essayist. It did not seem likely that our incalculable public would make themselves at home in those fantastic purlieus which Mr. Stevenson’s fancy discovered near the Strand. The impossible Young Man with the Cream Tarts, the ghastly revels of the Suicide Club, the Oriental caprices of the Hansom Cabs—who could foresee that the public would taste them! It is true that Mr. Stevenson’s imagination made the President of the Club, and the cowardly member, Mr. Malthus, as real as they were terrible. His romance always goes hand in hand with reality; and Mr. Malthus is as much an actual man of skin and bone, as Silas Lapham is a man of flesh and blood. The world saw this, and applauded the “Noctes of Prince Floristan,” in a fairy London.

Yet, excellent and unique as these things were, Mr. Stevenson had not yet “found himself.” It would be more true to say that he had only discovered outlying skirts of his dominions. Has he ever hit on the road to the capital yet? and will he ever enter it laurelled, and in triumph? That is precisely what one may doubt, not as without hope. He is always making discoveries in his realm; it is less certain that he will enter its chief city in state. His next work was rather in the nature of annexation and invasion than a settling of his own realms. “Prince Otto” is not, to my mind, a ruler in his proper soil. The provinces of George Sand and of Mr. George Meredith have been taken captive. “Prince Otto” is fantastic indeed, but neither the fantasy nor the style is quite Mr. Stevenson’s. There are excellent passages, and the Scotch soldier of fortune is welcome, and the ladies abound in subtlety and wit. But the book, at least to myself, seems an extremely elaborate and skilful pastiche. I cannot believe in the persons. I vaguely smell a moral allegory (as in “Will of the Mill”). I do not clearly understand what it is all about. The scene is fairyland; but it is not the fairyland of Perrault. The ladies are beautiful and witty; but they are escaped from a novel of Mr. Meredith’s, and have no business here. The book is no more Mr. Stevenson’s than “The Tale of Two Cities” was Mr. Dickens’s.

It was probably by way of mere diversion and child’s play that Mr. Stevenson began “Treasure Island.” He is an amateur of boyish pleasures of masterpieces at a penny plain and twopence coloured. Probably he had looked at the stories of adventure in penny papers which only boys read, and he determined sportively to compete with their unknown authors. “Treasure Island” came out in such a periodical, with the emphatic woodcuts which adorn them. It is said that the puerile public was not greatly stirred. A story is a story, and they rather preferred the regular purveyors. The very faint archaism of the style may have alienated them. But, when “Treasure Island” appeared as a real book, then every one who had a smack of youth left was a boy again for some happy hours. Mr. Stevenson had entered into another province of his realm: the king had come to his own again.

They say the seamanship is inaccurate; I care no more than I do for the year 30. They say too many people are killed. They all died in fair fight, except a victim of John Silver’s. The conclusion is a little too like part of Poe’s most celebrated tale, but nobody has bellowed “Plagiarist!” Some people may not look over a fence: Mr. Stevenson, if he liked, might steal a horse,—the animal in this case is only a skeleton. A very sober student might add that the hero is impossibly clever; but, then, the hero is a boy, and this is a boy’s book. For the rest, the characters live. Only genius could have invented John Silver, that terribly smooth-spoken mariner. Nothing but genius could have drawn that simple yokel on the island, with his craving for cheese as a Christian dainty. The blustering Billy Bones is a little masterpiece: the blind Pew, with his tapping stick (there are three such blind tappers in Mr. Stevenson’s books), strikes terror into the boldest. Then, the treasure is thoroughly satisfactory in kind, and there is plenty of it. The landscape, as in the feverish, fog-smothered flat, is gallantly painted. And there are no interfering petticoats in the story.

As for the “Black Arrow,” I confess to sharing the disabilities of the “Critic on the Hearth,” to whom it is dedicated. “Kidnapped” is less a story than a fragment; but it is a noble fragment. Setting aside the wicked old uncle, who in his later behaviour is of the house of Ralph Nickleby, “Kidnapped” is all excellent—perhaps Mr. Stevenson’s masterpiece. Perhaps, too, only a Scotchman knows how good it is, and only a Lowland Scot knows how admirable a character is the dour, brave, conceited David Balfour. It is like being in Scotland again to come on “the green drive-road running wide through the heather,” where David “took his last look of Kirk Essendean, the trees about the manse, and the big rowans in the kirkyard, where his father and mother lay.” Perfectly Scotch, too, is the mouldering, empty house of the Miser, with the stamped leather on the walls. And the Miser is as good as a Scotch Trapbois, till he becomes homicidal, and then one fails to recognise him unless he is a little mad, like that other frantic uncle in “The Merry Men.” The scenes on the ship, with the boy who is murdered, are better—I think more real—than the scenes of piratical life in “The Master of Ballantrae.” The fight in the Round House, even if it were exaggerated, would be redeemed by the “Song of the Sword of Alan.” As to Alan Breck himself, with his valour and vanity, his good heart, his good conceit of himself, his fantastic loyalty, he is absolutely worthy of the hand that drew Callum Bey and the Dougal creature. It is just possible that we see, in “Kidnapped,” more signs of determined labour, more evidence of touches and retouches, than in “Rob Roy.” In nothing else which it attempts is it inferior; in mastery of landscape, as in the scene of the lonely rock in a dry and thirsty land, it is unsurpassed. If there are signs of laboured handling on Alan, there are none in the sketches of Cluny and of Rob Roy’s son, the piper. What a generous artist is Alan! “Robin Oig,” he said, when it was done, “ye are a great piper. I am not fit to blow in the same kingdom with you. Body of me! ye have mair music in your sporran than I have in my head.”

“Kidnapped,” we said, is a fragment. It ends anywhere, or nowhere, as if the pen had dropped from a weary hand. Thus, and for other reasons, one cannot pretend to set what is not really a whole against such a rounded whole as “Rob Roy,” or against “The Legend of Montrose.” Again, “Kidnapped” is a novel without a woman in it: not here is Di Vernon, not here is Helen McGregor. David Balfour is the pragmatic Lowlander; he does not bear comparison, excellent as he is, with Baillie Nicol Jarvie, the humorous Lowlander: he does not live in the memory like the immortal Baillie. It is as a series of scenes and sketches that “Kidnapped” is unmatched among Mr. Stevenson’s works.

In “The Master of Ballantrae” Mr. Stevenson makes a gallant effort to enter what I have ventured to call the capital of his kingdom. He does introduce a woman, and confronts the problems of love as well as of fraternal hatred. The “Master” is studied, is polished ad unguem; it is a whole in itself, it is a remarkably daring attempt to write the tragedy, as, in “Waverley,” Scott wrote the romance, of Scotland about the time of the Forty-Five. With such a predecessor and rival, Mr. Stevenson wisely leaves the pomps and battles of the Forty-Five, its chivalry and gallantry, alone. He shows us the seamy side: the intrigues, domestic and political; the needy Irish adventurer with the Prince, a person whom Scott had not studied. The book, if completely successful, would be Mr. Stevenson’s “Bride of Lammermoor.” To be frank, I do not think it completely successful—a victory all along the line. The obvious weak point is Secundra Dass, that Indian of unknown nationality; for surely his name marks him as no Hindoo. The Master could not have brought him, shivering like Jos Sedley’s black servant, to Scotland. As in America, this alien would have found it “too dam cold.” My power of belief (which verges on credulity) is staggered by the ghastly attempt to reanimate the buried Master. Here, at least to my taste, the freakish changeling has got the better of Mr. Stevenson, and has brought in an element out of keeping with the steady lurid tragedy of fraternal hatred. For all the rest, it were a hard judge that had anything but praise. The brilliant blackguardism of the Master; his touch of sentiment as he leaves Durisdeer for the last time, with a sad old song on his lips; his fascination; his ruthlessness; his irony;—all are perfect. It is not very easy to understand the Chevalier Bourke, that Barry Lyndon, with no head and with a good heart, that creature of a bewildered kindly conscience; but it is easy to like him. How admirable is his undeflected belief in and affection for the Master! How excellent and how Irish he is, when he buffoons himself out of his perils with the pirates! The scenes are brilliant and living, as when the Master throws the guinea through the Hall window, or as in the darkling duel in the garden. It needed an austere artistic conscience to make Henry, the younger brother, so unlovable with all his excellence, and to keep the lady so true, yet so much in shadow. This is the best woman among Mr. Stevenson’s few women; but even she is almost always reserved, veiled as it were.

The old Lord, again, is a portrait as lifelike as Scott could have drawn, and more delicately touched than Scott would have cared to draw it: a French companion picture to the Baron Bradwardine. The whole piece reads as if Mr. Stevenson had engaged in a struggle with himself as he wrote. The sky is never blue, the sun never shines: we weary for a “westland wind.” There is something “thrawn,” as the Scotch say, about the story; there is often a touch of this sinister kind in the author’s work. The language is extraordinarily artful, as in the mad lord’s words, “I have felt the hilt dirl on his breast-bone.” And yet, one is hardly thrilled as one expects to be, when, as Mackellar says, “the week-old corpse looked me for a moment in the face.”

Probably none of Mr. Stevenson’s many books has made his name so familiar as “Dr. Jekyll and Mr Hyde.” I read it first in manuscript, alone, at night; and, when the Butler and Mr. Urmson came to the Doctor’s door, I confess that I threw it down, and went hastily to bed. It is the most gruesome of all his writings, and so perfect that one can complain only of the slightly too obvious moral; and, again, that really Mr. Hyde was more of a gentleman than the unctuous Dr. Jekyll, with his “bedside manner.”

So here, not to speak of some admirable short stories like “Thrawn Janet,” is a brief catalogue—little more—of Mr. Stevenson’s literary baggage. It is all good, though variously good; yet the wise world asks for the masterpiece. It is said that Mr. Stevenson has not ventured on the delicate and dangerous ground of the novel, because he has not written a modern love story. But who has? There are love affairs in Dickens, but do we remember or care for them? Is it the love affairs that we remember in Scott? Thackeray may touch us with Clive’s and Jack Belsize’s misfortunes, with Esmond’s melancholy passion, and amuse us with Pen in so many toils, and interest us in the little heroine of the “Shabby Genteel Story.” But it is not by virtue of those episodes that Thackeray is so great. Love stories are best done by women, as in “Mr. Gilfil’s Love Story”; and, perhaps, in an ordinary way, by writers like Trollope. One may defy critics to name a great English author in fiction whose chief and distinguishing merit is in his pictures of the passion of Love. Still, they all give Love his due stroke in the battle, and perhaps Mr. Stevenson will do so some day. But I confess that, if he ever excels himself, I do not expect it to be in a love story.

Possibly it may be in a play. If he again attempt the drama, he has this in his favour, that he will not deal in supernumeraries. In his tales his minor characters are as carefully drawn as his chief personages. Consider, for example, the minister, Henderland, the man who is so fond of snuff, in “Kidnapped,” and, in the “Master of Ballantrae,” Sir William Johnson, the English Governor. They are the work of a mind as attentive to details, as ready to subordinate or obliterate details which are unessential. Thus Mr. Stevenson’s writings breathe equally of work in the study and of inspiration from adventure in the open air, and thus he wins every vote, and pleases every class of reader.

I cannot sing the old songs, nor indeed any others, but I can read them, in the neglected works of Thomas Haynes Bayly. The name of Bayly may be unfamiliar, but every one almost has heard his ditties chanted—every one much over forty, at all events. “I’ll hang my Harp on a Willow Tree,” and “I’d be a Butterfly,” and “Oh, no! we never mention Her,” are dimly dear to every friend of Mr. Richard Swiveller. If to be sung everywhere, to hear your verses uttered in harmony with all pianos and quoted by the world at large, be fame, Bayly had it. He was an unaffected poet. He wrote words to airs, and he is almost absolutely forgotten. To read him is to be carried back on the wings of music to the bowers of youth; and to the bowers of youth I have been wafted, and to the old booksellers. You do not find on every stall the poems of Bayly; but a copy in two volumes has been discovered, edited by Mr. Bayly’s widow (Bentley, 1844). They saw the light in the same year as the present critic, and perhaps they ceased to be very popular before he was breeched. Mr. Bayly, according to Mrs. Bayly, “ably penetrated the sources of the human heart,” like Shakespeare and Mr. Howells. He also “gave to minstrelsy the attributes of intellect and wit,” and “reclaimed even festive song from vulgarity,” in which, since the age of Anacreon, festive song has notoriously wallowed. The poet who did all this was born at Bath in Oct. 1797. His father was a genteel solicitor, and his great-grandmother was sister to Lord Delamere, while he had a remote baronet on the mother’s side. To trace the ancestral source of his genius was difficult, as in the case of Gifted Hopkins; but it was believed to flow from his maternal grandfather, Mr. Freeman, whom his friend, Lord Lavington, regarded as “one of the finest poets of his age.” Bayly was at school at Winchester, where he conducted a weekly college newspaper. His father, like Scott’s, would have made him a lawyer; but “the youth took a great dislike to it, for his ideas loved to dwell in the regions of fancy,” which are closed to attorneys. So he thought of being a clergyman, and was sent to St. Mary’s Hall, Oxford. There “he did not apply himself to the pursuit of academical honours,” but fell in love with a young lady whose brother he had tended in a fatal illness. But “they were both too wise to think of living upon love, and, after mutual tears and sighs, they parted never to meet again. The lady, though grieved, was not heartbroken, and soon became the wife of another.” They usually do. Mr. Bayly’s regret was more profound, and expressed itself in the touching ditty:

“Oh, no, we never mention her,

Her name is never heard,

My lips are now forbid to speak

That once familiar word;

From sport to sport they hurry me

To banish my regret,

And when they only worry me—

[I beg Mr. Bayly’s pardon]

“And when they win a smile from me,

They fancy I forget.“They bid me seek in change of scene

The charms that others see,

But were I in a foreign land

They’d find no change in me.

’Tis true that I behold no more

The valley where we met;

I do not see the hawthorn tree,

But how can I forget?”* * * * *

“They tell me she is happy now,

[And so she was, in fact.]

The gayest of the gay;

They hint that she’s forgotten me;

But heed not what they say.

Like me, perhaps, she struggles with

Each feeling of regret:

’Tis true she’s married Mr. Smith,

But, ah, does she forget!”

The temptation to parody is really too strong; the last lines, actually and in an authentic text, are:

“But if she loves as I have loved,

She never can forget.”

Bayly had now struck the note, the sweet, sentimental note, of the early, innocent, Victorian age. Jeames imitated him:

“R. Hangeline, R. Lady mine,

Dost thou remember Jeames!”

We should do the trick quite differently now, more like this:

“Love spake to me and said:

‘Oh, lips, be mute;

Let that one name be dead,

That memory flown and fled,

Untouched that lute!

Go forth,’ said Love, ‘with willow in thy hand,

And in thy hair

Dead blossoms wear,

Blown from the sunless land.“‘Go forth,’ said Love; ‘thou never more shalt see

Her shadow glimmer by the trysting tree;

But she is glad,

With roses crowned and clad,

Who hath forgotten thee!’

But I made answer: ‘Love!

Tell me no more thereof,

For she has drunk of that same cup as I.

Yea, though her eyes be dry,

She garners there for me

Tears salter than the sea,

Even till the day she die.’

So gave I Love the lie.”

I declare I nearly weep over these lines; for, though they are only Bayly’s sentiment hastily recast in a modern manner, there is something so very affecting, mouldy, and unwholesome about them, that they sound as if they had been “written up to” a sketch by a disciple of Mr. Rossetti’s.

In a mood much more manly and moral, Mr. Bayly wrote another poem to the young lady:

“May thy lot in life be happy, undisturbed by thoughts of me,

The God who shelters innocence thy guard and guide will be.

Thy heart will lose the chilling sense of hopeless love at last,

And the sunshine of the future chase the shadows of the past.”

It is as easy as prose to sing in this manner. For example:

“In fact, we need not be concerned; ‘at last’ comes very soon, and our Emilia quite forgets the memory of the moon, the moon that shone on her and us, the woods that heard our vows, the moaning of the waters, and the murmur of the boughs. She is happy with another, and by her we’re quite forgot; she never lets a thought of us bring shadow on her lot; and if we meet at dinner she’s too clever to repine, and mentions us to Mr. Smith as ‘An old flame of mine.’ And shall I grieve that it is thus? and would I have her weep, and lose her healthy appetite and break her healthy sleep? Not so, she’s not poetical, though ne’er shall I forget the fairy of my fancy whom I once thought I had met. The fairy of my fancy! It was fancy, most things are; her emotions were not steadfast as the shining of a star; but, ah, I love her image yet, as once it shone on me, and swayed me as the low moon sways the surging of the sea.”

Among other sports his anxious friends hurried the lovelorn Bayly to Scotland, where he wrote much verse, and then to Dublin, which completed his cure. “He seemed in the midst of the crowd the gayest of all, his laughter rang merry and loud at banquet and hall.” He thought no more of studying for the Church, but went back to Bath, met a Miss Hayes, was fascinated by Miss Hayes, “came, saw, but did not conquer at once,” says Mrs. Haynes Bayly (née Hayes) with widow’s pride. Her lovely name was Helena; and I deeply regret to add that, after an education at Oxford, Mr. Bayly, in his poems, accentuated the penultimate, which, of course, is short.

“Oh, think not, Helena, of leaving us yet,”

he carolled, when it would have been just as easy, and a hundred times more correct, to sing—

“Oh, Helena, think not of leaving us yet.”

Miss Hayes had lands in Ireland, alas! and Mr. Bayly insinuated that, like King Easter and King Wester in the ballad, her lovers courted her for her lands and her fee; but he, like King Honour,

“For her bonny face

And for her fair bodie.”

In 1825 (after being elected to the Athenæum) Mr. Bayly “at last found favour in the eyes of Miss Hayes.” He presented her with a little ruby heart, which she accepted, and they were married, and at first were well-to-do, Miss Hayes being the heiress of Benjamin Hayes, Esq., of Marble Hill, in county Cork. A friend of Mr. Bayly’s described him thus:

“I never have met on this chilling earth

So merry, so kind, so frank a youth,

In moments of pleasure a smile all mirth,

In moments of sorrow a heart of truth.

I have heard thee praised, I have seen thee led

By Fashion along her gay career;

While beautiful lips have often shed

Their flattering poison in thine ear.”

Yet he says that the poet was unspoiled. On his honeymoon, at Lord Ashdown’s, Mr. Bayly, flying from some fair sirens, retreated to a bower, and there wrote his world-famous “I’d be a Butterfly.”

“I’d be a butterfly, living a rover,

Dying when fair things are fading away.”

The place in which the deathless strains welled from the singer’s heart was henceforth known as “Butterfly Bower.” He now wrote a novel, “The Aylmers,” which has gone where the old moons go, and he became rather a literary lion, and made the acquaintance of Theodore Hook. The loss of a son caused him to write some devotional verses, which were not what he did best; and now he began to try comedies. One of them, Sold for a Song, succeeded very well. In the stage-coach between Wycombe Abbey and London he wrote a successful little lever de rideau called Perfection; and it was lucky that he opened this vein, for his wife’s Irish property got into an Irish bog of dishonesty and difficulty. Thirty-five pieces were contributed by him to the British stage. After a long illness, he died on April 22nd, 1829. He did not live, this butterfly minstrel, into the winter of human age.

Of his poems the inevitable criticism must be that he was a Tom Moore of much lower accomplishments. His business was to carol of the most vapid and obvious sentiment, and to string flowers, fruits, trees, breeze, sorrow, to-morrow, knights, coal-black steeds, regret, deception, and so forth, into fervid anapæstics. Perhaps his success lay in knowing exactly how little sense in poetry composers will endure and singers will accept. Why, “words for music” are almost invariably trash now, though the words of Elizabethan songs are better than any music, is a gloomy and difficult question. Like most poets, I myself detest the sister art, and don’t know anything about it. But any one can see that words like Bayly’s are and have long been much more popular with musical people than words like Shelley’s, Keats’s, Shakespeare’s, Fletcher’s, Lovelace’s, or Carew’s. The natural explanation is not flattering to musical people: at all events, the singing world doted on Bayly.

“She never blamed him—never,

But received him when he came

With a welcome sort of shiver,

And she tried to look the same.“But vainly she dissembled,

For whene’er she tried to smile,

A tear unbidden trembled

In her blue eye all the while.”

This was pleasant for “him”; but the point is that these are lines to an Indian air. Shelley, also, about the same time, wrote Lines to an Indian air; but we may “swear, and save our oath,” that the singers preferred Bayly’s. Tennyson and Coleridge could never equal the popularity of what follows. I shall ask the persevering reader to tell me where Bayly ends, and where parody begins:

“When the eye of beauty closes,

When the weary are at rest,

When the shade the sunset throws is

But a vapour in the west;

When the moonlight tips the billow

With a wreath of silver foam,

And the whisper of the willow

Breaks the slumber of the gnome,—

Night may come, but sleep will linger,

When the spirit, all forlorn,

Shuts its ear against the singer,

And the rustle of the corn

Round the sad old mansion sobbing

Bids the wakeful maid recall

Who it was that caused the throbbing

Of her bosom at the ball.”

Will this not do to sing just as well as the original? and is it not true that “almost any man you please could reel it off for days together”? Anything will do that speaks of forgetting people, and of being forsaken, and about the sunset, and the ivy, and the rose.

“Tell me no more that the tide of thine anguish

Is red as the heart’s blood and salt as the sea;

That the stars in their courses command thee to languish,

That the hand of enjoyment is loosened from thee!“Tell me no more that, forgotten, forsaken,

Thou roamest the wild wood, thou sigh’st on the shore.

Nay, rent is the pledge that of old we had taken,

And the words that have bound me, they bind thee no more!“Ere the sun had gone down on thy sorrow, the maidens

Were wreathing the orange’s bud in thy hair,

And the trumpets were tuning the musical cadence

That gave thee, a bride, to the baronet’s heir.“Farewell, may no thought pierce thy breast of thy treason;

Farewell, and be happy in Hubert’s embrace.

Be the belle of the ball, be the bride of the season,

With diamonds bedizened and languid in lace.”

This is mine, and I say, with modest pride, that it is quite as good as—

“Go, may’st thou be happy,

Though sadly we part,

In life’s early summer

Grief breaks not the heart.“The ills that assail us

As speedily pass

As shades o’er a mirror,

Which stain not the glass.”

Anybody could do it, we say, in what Edgar Poe calls “the mad pride of intellectuality,” and it certainly looks as if it could be done by anybody. For example, take Bayly as a moralist. His ideas are out of the centre. This is about his standard:

“CRUELTY.

“‘Break not the thread the spider

Is labouring to weave.’

I said, nor as I eyed her

Could dream she would deceive.“Her brow was pure and candid,

Her tender eyes above;

And I, if ever man did,

Fell hopelessly in love.“For who could deem that cruel

So fair a face might be?

That eyes so like a jewel

Were only paste for me?“I wove my thread, aspiring

Within her heart to climb;

I wove with zeal untiring

For ever such a time!“But, ah! that thread was broken

All by her fingers fair,

The vows and prayers I’ve spoken

Are vanished into air!”

Did Bayly write that ditty or did I? Upon my word, I can hardly tell. I am being hypnotised by Bayly. I lisp in numbers, and the numbers come like mad. I can hardly ask for a light without abounding in his artless vein. Easy, easy it seems; and yet it was Bayly after all, not you nor I, who wrote the classic—

“I’ll hang my harp on a willow tree,

And I’ll go to the war again,

For a peaceful home has no charm for me,

A battlefield no pain;

The lady I love will soon be a bride,

With a diadem on her brow.

Ah, why did she flatter my boyish pride?

She is going to leave me now!”

It is like listening, in the sad yellow evening, to the strains of a barrel organ, faint and sweet, and far away. A world of memories come jigging back—foolish fancies, dreams, desires, all beckoning and bobbing to the old tune:

“Oh had I but loved with a boyish love,

It would have been well for me.”

How does Bayly manage it? What is the trick of it, the obvious, simple, meretricious trick, which somehow, after all, let us mock as we will, Bayly could do, and we cannot? He really had a slim, serviceable, smirking, and sighing little talent of his own; and—well, we have not even that. Nobody forgets

“The lady I love will soon be a bride.”

Nobody remembers our cultivated epics and esoteric sonnets, oh brother minor poet, mon semblable, mon frère! Nor can we rival, though we publish our books on the largest paper, the buried popularity of

“Gaily the troubadour

Touched his guitar

When he was hastening

Home from the war,

Singing, “From Palestine

Hither I come,

Lady love! Lady love!

Welcome me home!”

Of course this is, historically, a very incorrect rendering of a Languedoc crusader; and the impression is not mediæval, but of the comic opera. Any one of us could get in more local colour for the money, and give the crusader a cithern or citole instead of a guitar. This is how we should do “Gaily the Troubadour” nowadays:—

“Sir Ralph he is hardy and mickle of might,

Ha, la belle blanche aubépine!

Soldans seven hath he slain in fight,

Honneur à la belle Isoline!“Sir Ralph he rideth in riven mail,

Ha, la belle blanche aubépine!

Beneath his nasal is his dark face pale,

Honneur à la belle Isoline!“His eyes they blaze as the burning coal,

Ha, la belle blanche aubépine!

He smiteth a stave on his gold citole,

Honneur à la belle Isoline!“From her mangonel she looketh forth,

Ha, la belle blanche aubépine!

‘Who is he spurreth so late to the north?’

Honneur à la belle Isoline!“Hark! for he speaketh a knightly name,

Ha, la belle blanche aubépine!

And her wan cheek glows as a burning flame,

Honneur à la belle Isoline!“For Sir Ralph he is hardy and mickle of might,

Ha, la belle blanche aubépine!

And his love shall ungirdle his sword to-night,

Honneur à la belle Isoline!”

Such is the romantic, esoteric, old French way of saying—

“Hark, ’tis the troubadour

Breathing her name

Under the battlement

Softly he came,

Singing, “From Palestine

Hither I come.

Lady love! Lady love!

Welcome me home!”

The moral of all this is that minor poetry has its fashions, and that the butterfly Bayly could versify very successfully in the fashion of a time simpler and less pedantic than our own. On the whole, minor poetry for minor poetry, this artless singer, piping his native drawing-room notes, gave a great deal of perfectly harmless, if highly uncultivated, enjoyment.

It must not be fancied that Mr. Bayly had only one string to his bow—or, rather, to his lyre. He wrote a great deal, to be sure, about the passion of love, which Count Tolstoï thinks we make too much of. He did not dream that the affairs of the heart should be regulated by the State—by the Permanent Secretary of the Marriage Office. That is what we are coming to, of course, unless the enthusiasts of “free love” and “go away as you please” failed with their little programme. No doubt there would be poetry if the State regulated or left wholly unregulated the affections of the future. Mr. Bayly, living in other times, among other manners, piped of the hard tyranny of a mother:

“We met, ’twas in a crowd, and I thought he would shun me.

He came, I could not breathe, for his eye was upon me.

He spoke, his words were cold, and his smile was unaltered,

I knew how much he felt, for his deep-toned voice faltered.

I wore my bridal robe, and I rivalled its whiteness;

Bright gems were in my hair,—how I hated their brightness!

He called me by my name as the bride of another.

Oh, thou hast been the cause of this anguish, my mother!”

In future, when the reformers of marriage have had their way, we shall read:

“The world may think me gay, for I bow to my fate;

But thou hast been the cause of my anguish, O State!”

For even when true love is regulated by the County Council or the village community, it will still persist in not running smooth.

Of these passions, then, Mr. Bayly could chant; but let us remember that he could also dally with old romance, that he wrote:

“The mistletoe hung in the castle hall,

The holly branch shone on the old oak wall.”

When the bride unluckily got into the ancient chest,

“It closed with a spring. And, dreadful doom,

The bride lay clasped in her living tomb,”

so that her lover “mourned for his fairy bride,” and never found out her premature casket. This was true romance as understood when Peel was consul. Mr. Bayly was rarely political; but he commemorated the heroes of Waterloo, our last victory worth mentioning:

“Yet mourn not for them, for in future tradition

Their fame shall abide as our tutelar star,

To instil by example the glorious ambition

Of falling, like them, in a glorious war.

Though tears may be seen in the bright eyes of beauty,

One consolation must ever remain:

Undaunted they trod in the pathway of duty,

Which led them to glory on Waterloo’s plain.”

Could there be a more simple Tyrtæus? and who that reads him will not be ambitious of falling in a glorious war? Bayly, indeed, is always simple. He is “simple, sensuous, and passionate,” and Milton asked no more from a poet.