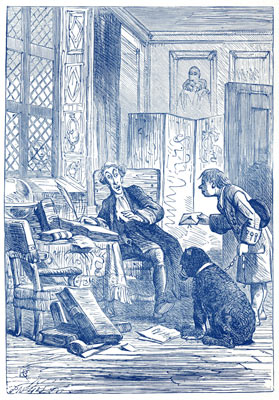

WHARTON'S ROGUISH PRESENT.

WHARTON'S ROGUISH PRESENT.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Wits and Beaux of Society, by

Grace Wharton and Philip Wharton

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Wits and Beaux of Society

Volume 1

Author: Grace Wharton and Philip Wharton

Release Date: March 19, 2006 [EBook #18020]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE WITS AND BEAUX OF SOCIETY ***

Produced by Bill Tozier, Barbara Tozier, Patricia A. Benoy

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

Dear Mr. Augustin Daly,

May I write your name on the dedication page of this new edition of an old and pleasant book in token of our common interest in the people and the periods of which it treats, and as a small proof of our friendship?

Sincerely yours,

JUSTIN HUNTLY M'CARTHY.

London, July, 1890.

p. xi Preface to the Present Edition

p. xxv Preface to the Second Edition

p. xxix Preface to the First Edition

GEORGE VILLIERS, SECOND DUKE OF BUCKINGHAM.

Signs of the Restoration.—Samuel Pepys in his Glory.—A Royal

Company.—Pepys 'ready to Weep.'—The Playmate of Charles

II.—George Villiers's Inheritance.—Two Gallant Young

Noblemen.—The Brave Francis Villiers.—After the Battle of

Worcester.—Disguising the King.—Villiers in Hiding.—He

appears as a Mountebank.—Buckingham's Habits.—A Daring

Adventure.—Cromwell's Saintly Daughter.—Villiers and the

Rabbi.—The Buckingham Pictures and Estates.—York

House.—Villiers returns to England.—Poor Mary

Fairfax.—Villiers in the Tower.—Abraham Cowley, the

Poet.—The Greatest Ornament of Whitehall.—Buckingham's Wit

and Beauty.—Flecknoe's Opinion of Him.—His Duel with the Earl

of Shrewsbury.—Villiers as a Poet.—As a Dramatist.—A Fearful

Censure!—Villiers's Influence in Parliament.—A Scene in the

Lords.—The Duke of Ormond in Danger.—Colonel Blood's

Outrages.—Wallingford House and Ham House.—'Madame

Ellen.'—The Cabal.—Villiers again in the Tower.—A

Change.—The Duke of York's Theatre.—Buckingham and the

Princess of Orange.—His last Hours.—His Religion.—Death of

Villiers.—The Duchess of Buckingham.

p. 1

COUNT DE GRAMMONT, ST. EVREMOND, AND LORD ROCHESTER.

De Grammont's Choice.—His Influence with Turenne.—The Church or

the Army?—An Adventure at Lyons.—A brilliant Idea.—De

Grammont's Generosity.—A Horse 'for the

Cards.'—Knight-Cicisbeism.—De Grammont's first Love.—His

Witty Attacks on Mazarin.—Anne Lucie de la Mothe

Houdancourt.—Beset with Snares.—De Grammont's Visits to

England.—Charles II.—The Court of Charles II.—Introduction

of Country-dances.—Norman Peculiarities.—St. Evremond, the

Handsome Norman.—The most Beautiful Woman in Europe.—Hortense

Mancini's Adventures.—Madame Mazarin's House at

Chelsea.—Anecdote of Lord Dorset.—Lord Rochester in his

Zenith.—His Courage and Wit[vi]—Rochester's Pranks in the

City.—Credulity, Past and Present—'Dr. Bendo,' and La Belle

Jennings.—La Triste Heritière.—Elizabeth, Countess of

Rochester.—Retribution and Reformation.—Conversion.—Beaux

without Wit.—Little Jermyn.—An Incomparable Beauty.—Anthony

Hamilton, De Grammont's Biographer.—The Three Courts.—'La

Belle Hamilton.'—Sir Peter Lely's Portrait of her.—The

Household Deity of Whitehall.—Who shall have the Calèche?—A

Chaplain in Livery.—De Grammont's Last Hours.—What might he

not have been? p. 41

On Wits and Beaux.—Scotland Yard in Charles II.'s day.—Orlando of

'The Tatler.'—Beau Fielding, Justice of the Peace.—Adonis in

Search of a Wife.—The Sham Widow.—Ways and Means.—Barbara

Villiers, Lady Castlemaine.—Quarrels with the King.—The

Beau's Second Marriage.—The Last Days of Fops and Beaux. p. 80

OF CERTAIN CLUBS AND CLUB-WITS UNDER ANNE.

The Origin of Clubs.—The Establishment of Coffee-houses.—The

October Club.—The Beef-steak Club.—Of certain other

Clubs.—The Kit-kat Club.—The Romance of the Bowl.—The Toasts

of the Kit-kat.—The Members of the Kit-kat.—A good Wit, and a

bad Architect.—'Well-natured Garth.'—The Poets of the

Kit-kat.—Charles Montagu, Earl of Halifax.—Chancellor

Somers.—Charles Sackville, Lord Dorset.—Less celebrated Wits.

p. 91

When and where was he born?—The Middle Temple.—Congreve finds his

Vocation.—Verses to Queen Mary.—The Tennis-court

Theatre.—Congreve abandons the Drama.—Jeremy Collier.—The

Immorality of the Stage.—Very improper Things.—Congreve's

Writings.—Jeremy's 'Short Views.'—Rival Theatres.—Dryden's

Funeral.—A Tub-Preacher.—Horoscopic Predictions.—Dryden's

Solicitude for his Son.—Congreve's Ambition.—Anecdote of

Voltaire and Congreve.—The Profession of Mæcenas.—Congreve's

Private Life.—'Malbrook's' Daughter.—Congreve's Death and

Burial. p. 106

The King of Bath.—Nash at Oxford.—'My Boy Dick.'—Offers of

Knighthood.—Doing Penance at York.—Days of Folly.—A very

Romantic Story.—Sickness and Civilization.—Nash descends upon

Bath.—Nash's Chef-d'œuvre.—The Ball.—Improvements in the

Pump-room, &c.—A Public Benefactor.—Life at Bath in Nash's

time.—A Compact with the Duke of Beaufort.—Gaming at

Bath.—Anecdotes of Nash.—'Miss Sylvia.'—A Generous

Act.—Nash's Sun setting.—A Panegyric.—Nash's Funeral.—His

Characteristics. p. 127

Wharton's Ancestors.—His Early Years.—Marriage at

Sixteen.—Wharton takes leave of his Tutor.—The Young Marquis

and the Old Pretender.—Frolics at Paris.—Zeal for the Orange

Cause.—A Jacobite Hero.—The Trial of Atterbury.—Wharton's

Defence of the Bishop.—Hypocritical Signs of [vii]Penitence.—Sir

Robert Walpole duped.—Very Trying.—The Duke of Wharton's

'Whens.'—Military Glory at Gibraltar.—'Uncle

Horace.'—Wharton to 'Uncle Horace.'—The Duke's

Impudence.—High Treason.—Wharton's Ready Wit.—Last

Extremities.—Sad Days in Paris.—His Last Journey to

Spain.—His Death in a Bernardine Convent. p. 148

George II. arriving from Hanover.—His Meeting with the

Queen.—Lady Suffolk.—Queen Caroline.—Sir Robert

Walpole.—Lord Hervey.—A Set of Fine Gentlemen.—An Eccentric

Race.—Carr, Lord Hervey.—A Fragile Boy.—Description of

George II.'s Family.—Anne Brett.—A Bitter Cup.—The Darling

of the Family.—Evenings at St. James's.—Frederick, Prince of

Wales.—Amelia Sophia Walmoden.—Poor Queen

Caroline!—Nocturnal Diversions of Maids of Honour.—Neighbour

George's Orange Chest.—Mary Lepel, Lady

Hervey.—Rivalry.—Hervey's Intimacy with Lady

Mary.—Relaxations of the Royal Household.—Bacon's Opinion of

Twickenham.—A Visit to Pope's Villa.—The Little

Nightingale.—The Essence of Small Talk.—Hervey's Affectation

and Effeminacy.—Pope's Quarrel with Hervey and Lady

Mary.—Hervey's Duel with Pulteney.—'The Death of Lord Hervey:

a Drama.'—Queen Caroline's last Drawing-room.—Her Illness and

Agony.—A Painful Scene.—The Truth discovered.—The Queen's

Dying Bequests.—The King's Temper.—Archbishop Potter is sent

for.—The Duty of Reconciliation.—The Death of Queen

Caroline.—A Change in Hervey's Life.—Lord Hervey's

Death.—Want of Christianity.—Memoirs of his Own Time. p. 170

PHILIP DORMER STANHOPE, FOURTH EARL OF CHESTERFIELD.

The King of Table Wits.—Early Years.—Hervey's Description of his

Person.—Resolutions and Pursuits.—Study of Oratory.—The

Duties of an Ambassador.—King George II.'s Opinion of his

Chroniclers.—Life in the Country.—Melusina, Countess of

Walsingham.—George II. and his Father's Will.—Dissolving

Views.—Madame du Bouchet.—The Broad-Bottomed

Administration.—Lord-Lieutenant of Ireland in Time of

Peril.—Reformation of the Calendar.—Chesterfield

House.—Exclusiveness.—Recommending 'Johnson's

Dictionary.'—'Old Samuel,' to Chesterfield.—Defensive

Pride.—The Glass of Fashion.—Lord Scarborough's Friendship

for Chesterfield.—The Death of Chesterfield's Son.—His

Interest in his Grandsons.—'I must go and Rehearse my

Funeral.'—Chesterfield's Will.—What is a Friend?—Les

Manières Nobles.—Letters to his Son. p. 210

An Eastern Allegory.—Who comes Here?—A Mad Freak and its

Consequences.—Making an Abbé of him.—The May-Fair of

Paris.—Scarron's Lament to Pellisson.—The Office of the

Queen's Patient.—'Give me a Simple Benefice.'—Scarron's

Description of Himself.—Improvidence and Servility.—The

Society at Scarron's.—The Witty Conversation.—Francoise

D'Aubigné's Début.—The Sad Story of La Belle

Indienne.—Matrimonial Considerations.—'Scarron's Wife will

live for ever.'—Petits Soupers.—Scarron's last Moments.—A

Lesson for Gay and Grave. p. 235

FRANÇOIS DUC DE LA ROCHEFOUCAULT AND THE DUC DE SAINT-SIMON.

Rank and Good Breeding.—The Hôtel de Rochefoucault.—Racine and

his Plays.—La Rochefoucault's Wit and Sensibility.—Saint-Simon's

Youth.—Looking out for a Wife.—Saint-Simon's Court Life.—The

History of Louise de la Vallière.—A mean Act of Louis

Quatorze.—All has passed away.—Saint-Simon's Memoirs of His

Own Time. p. 253

PAGE

(Frontispiece)

WHARTON'S ROGUISH PRESENT

14

VILLIERS IN DISGUISE—THE MEETING WITH HIS SISTER

74

DE GRAMMONT'S MEETING WITH LA BELLE HAMILTON

85

BEAU FIELDING AND THE SHAM WIDOW

172

A SCENE BEFORE KENSINGTON PALACE—GEORGE II. AND QUEEN CAROLINE

194

POPE AT HIS VILLA—DISTINGUISHED VISITORS

217

A ROYAL ROBBER

226

DR. JOHNSON AT LORD CHESTERFIELD'S

247

SCARRON AND THE WITS—FIRST APPEARANCE OF LA BELLE INDIENNE

When Grace and Philip Wharton found that they had pleased the world with their "Queens of Society," they very sensibly resolved to follow up their success with a companion work. Their first book had been all about women; the second book should be all about men. Accordingly they set to work selecting certain types that pleased them; they wrote a fresh collection of pleasant essays and presented the reading public with "Wits and Beaux of Society". The one book is as good as the other; there is not a pin to choose between them. There is the same bright easy, gossiping style, the same pleasing rapidity. There is nothing tedious, nothing dull anywhere. They do not profess to have anything to do with the graver processes of history—these entertaining volumes; they seek rather to amuse than to instruct, and they fulfil their purpose excellently. There is instruction in them, but it comes in by the way; one is conscious of being entertained, and it is only after the entertainment is over that one finds that a fair amount of information has been thrown in to boot. The Whartons have but old tales to tell, but they tell them very well, and that is the first part of their business.

Looking over these articles is like looking over the list of a good club. Men are companionable creatures; [xii]they love to get together and gossip. It is maintained, and with reason, that they are fonder of their own society than women are. Men delight to breakfast together, to take luncheon together, to dine together, to sup together. They rejoice in clubs devoted exclusively to their service, as much taboo to women as a trappist monastery. Women are not quite so clannish. There are not very many women's clubs in the world; it is not certain that those which do exist are very brilliant or very entertaining. Women seldom give supper parties, "all by themselves they" after the fashion of that "grande dame de par le monde" of whom we have spoken elsewhere. A woman's dinner-party may succeed now and then by way of a joke, but it is a joke that is not often repeated. Have we not lately seen how an institution with a graceful English name, started in London for women and women only, has just so far relaxed its rigid rule as to allow men upon its premises between certain hours, and this relaxation we are told has been conceded in consequence of the demand of numerous ladies. Well, well, if men can on the whole get on better without the society of women than women can without the society of men it is no doubt because they are rougher creatures, moulded of a coarser clay, and are more entertained by eating and drinking, smoking and the telling of tales than women are.

If all the men whom the Whartons labelled as wits and beaux of society could be gathered together they would make a most excellent club in the sense in which a club was understood in the last century. Johnson thought that he had praised a man highly when he called him a clubbable man, and so he had for those days which dreamed not of vast caravanserai calling [xiii]themselves clubs and having thousands of members on their roll, the majority of whom do not know more than perhaps ten of their fellow members from Adam. In the sense that Dr. Johnson meant, all these wits and beaux whom our Whartons have gathered together were eminently clubbable. If some such necromancer could come to us as he who in Tourguenieff's story conjures up the shade of Julius Cæsar; and if in an obliging way he could make these wits and beaux greet us: if such a spiritualistic society as that described by Mr. Stockton in one of his diverting stories could materialise them all for our benefit: then one might count with confidence upon some very delightful company and some very delightful talk. For the people whom the Whartons have been good enough to group together are people of the most fascinating variety. They have wit in common and goodfellowship, they were famous entertainers in their time; they add to the gaiety of nations still. The Whartons have given what would in America be called a "Stag Party". If we join it we shall find much entertainment thereat.

Do people read Theodore Hook much nowadays? Does the generation which loves to follow the trail with Allan Quatermain, and to ride with a Splendid Spur, does it call at all for the humours of the days of the Regency? Do those who have laughed over "The Wrong Box," ever laugh over Jack Brag? Do the students of Mr. Rudyard Kipling know anything of "Gilbert Gurney?" Somebody started the theory some time ago, that this was not a laughter-loving generation, that it lacked high spirits. It has been maintained that if a writer appeared now, with the rollicking good spirits, and reckless abandon of a Lever, he [xiv]would scarcely win a warm welcome. We may be permitted to doubt this conclusion; we are as fond of laughter as ever, as ready to laugh if somebody will set us going. Mr. Stevenson prefers of late to be thought grim in his fiction, but he has set the sides shaking, both over that "Wrong Box" which we spoke of, and in earlier days. We are ready to laugh with Stockton from overseas, with our own Anstey, with anybody who has the heart to be merry, and the wit to make his mirth communicable. But, it may be doubted if we read our Lever quite as much as a wise doctor, who happened also to be a wise man of letters, would recommend. And we may well fancy that such a doctor dealing with a patient for whom laughter was salutary—as for whom is it not salutary—would exhibit Theodore Hook in rather large doses.

Undoubtedly the fun is a little old fashioned, but it is none the worse for that. Those who share Mr. Hardcastle's tastes for old wine and old books will not like Theodore Hook any the less, because he does not happen to be at all "Fin de Siècle". He is like Berowne in the comedy, the merriest man—perhaps not always within the limits of becoming mirth—to spend an hour's talk withal. There is no better key to the age in which Hook glittered, than Hook's own stories. The London of that day—the London which is as dead and gone as Nineveh or Karnak or Troy—lives with extraordinary freshness in Theodore Hook's pages. And how entertaining those pages are. It is not always the greatest writers who are the most mirth provoking, but how much we owe to them. The man must have no mirth in him if he fail to be tickled by the best of Labiche's comedies, aye and the worst too, if such a term [xv]can be applied to any of the enchanting series; if he refuse to unbend over "A Day's Journey and a Life's Romance," if he cannot let himself go and enjoy himself over Gilbert Gurney's river adventure. If the revival of the Whartons' book were to serve no other purpose than to send some laughter loving souls to the heady well-spring of Theodore Hook's merriment, it would have done the mirthful a good turn and deserved well of its country.

There is scarcely a queerer, or scarcely a more pathetic figure in the world than that of Beau Brummell. He seems to belong to ancient history, he and his titanic foppishness and his smart clothes and his smart sayings. Yet is it but a little while since the last of his adorers, the most devoted of his disciples passed away from the earth. Over in Paris there lingered till the past year a certain man of letters who was very brilliant and very poor and very eccentric. So long as people study French literature, and care to investigate the amount of high artistic workmanship which goes into even its minor productions, so long the name of Barbey D'Aurevilly will have its niche—not a very large one, it is true—in the temple. The author of that strange and beautiful story "Le Chevalier des Touches," was a great devotee of Brummell's. He was himself the "last of the dandies". All the money he had—and he had very little of it—he spent in dandification. But he never moved with the times. His foppishness was the foppishness of his youth, and to the last he wandered through Paris clad in the splendour of the days when young men were "lions," and when the quarrel between classicism and romanticism was vital. He wrote a book about Beau Brummell and a very curious little book it is, with its [xvi]odd earnest defence of dandyism, with its courageous championship of the arts which men of letters so largely affect to despise.

Poor Beau Brummell. After having played his small part on life's stage, his thin shade still occasionally wanders across the boards of the theatre. Blanchard Jerrold wrote a play upon him, which was acted at the Lyceum Theatre in 1859, when Emery played the title role. Jerrold's play, which has for sub-title "The King of Calais," treats of that period in Brummell's life in which he had retired across the channel to live upon black-mail and to drift into that Consulship at Caen which he so queerly resigned, to end a poor madman, trying to shave his own peruke. Jerrold's is a grim play; either it or a version on the same lines of Brummell's fall is being played across the Atlantic at this very hour by Mr. Mansfield whose study of the final decay and idiotcy of the famous beau is said to rival the impressiveness of his Mr. Hyde. Beau Brummell is never likely to be quite forgotten. Folly often brings with it a kind of immortality. The fool who fired the Temple of Ephesus has secured his place in history with Aristides and Themistocles; the fop who gave a kind of epic dignity to neck-clothes, and who asked the famous "Who's your fat friend?" question, is remembered as a figure of that age which includes the name of Sheridan and the name of Burke.

Another and a no less famous Beau steps to salute us from the pages of the Whartons. Beau Nash is an old friend of ours in fiction, an old friend in the drama. Our dear old Harrison Ainsworth wrote a novel about him yesterday; to-day he figures in the pages of one of the most attractive of Mr. Lewis Wingfield's attractive [xvii]stories. He found his way on to the stage under the care of Douglas Jerrold whose comedy of manners was acted at the Haymarket in the midsummer of 1834. There is a charm about these Beaux, these odd blossoms of last century civilisation, the Brummells and the Nashes and the Fieldings, so "high fantastical" in their bearing, such living examples of the eternal verities contained in the clothes' philosophy of Herr Diogenes Teufelsdröckh of Weissnichtwo. Their wigs were more important than their wit; the pattern of their waistcoats more important than the composition of their hearts; all morals, all philosophy are absorbed for them in the engrossing question of the fit of their breeches. D'Artois is of their kin, French d'Artois who helped to ruin the Old Order and failed to re-create it as Charles the Tenth, d'Artois whom Mercier describes as being poured into his faultlessly fitting breeches by the careful and united efforts of no less than four valets de chambre. But the English dandies were better than the Frenchman, for they did harm only to themselves, while he helped to ruin his cause, his party, and his king.

As we turn the pages, we come to one name which immediately if whimsically suggests poetry. The man was, like Touchstone's Audrey, not poetical and yet a great poet has been pleased to address him, very much as Pindar might have addressed the Ancestral Hero of some mighty tyrant.

Ah, George Bubb Dodington Lord Melcombe—no,

Yours was the wrong way!—always understand,

Supposing that permissibly you planned

How statesmanship—your trade—in outward show

Might figure as inspired by simple zeal

For serving country, king, and commonweal,

[xviii](Though service tire to death the body, teaze

The soul from out an o'ertasked patriot-drudge)

And yet should prove zeal's outward show agrees

In all respects—right reason being judge—

With inward care that while the statesman spends

Body and soul thus freely for the sake

Of public good, his private welfare take

No harm by such devotedness.

Thus Robert Browning in Robert Browning's penultimate book, that "Parleyings with certain people of importance in their day" which fell somewhat coldly upon all save Browning fanatics, and which, when it seemed to show that the poet's hand had palsied, served only as the discordant prelude to the swan song of "Asolando," the last and almost the greatest of his glories. Perhaps only Browning would ever have thought of undertaking a poetical parley with Bubb Dodington. Dodington is now largely, and not undeservedly forgotten. His dinners and his dresses, his poems and his pamphlets, his plays and his passions—the wind has carried them all away. If Pope had not nicknamed him Bubo, if Foote had not caricatured him in "The Patron," if Churchill had not lampooned him in "The Rosciad," he would scarcely have earned in his own day the notoriety which the publication of his "Diary" had in a manner preserved to later days. If he was hardly worth a corner in the Whartons' picture-gallery he was certainly scarcely deserving of the attention of Browning. Even his ineptitude was hardly important enough to have twenty pages of Browning's genius wasted upon it, twenty pages ending with the sting about

The scoff

That greets your very name: folks see but one

Fool more, as well as knave, in Dodington.

Dodington has been occasionally classed with Lord Hervey but the classification is scarcely fair. With all his faults—and he had them in abundance—Lord Hervey was a better creature than Bubb Dodington. If he was effeminate, he had convictions and could stand by them. If Pope sneered at him as Sporus and called him a curd of asses' milk, he has left behind him some of the most brilliant memoirs ever penned. If he had some faults in common with Dodington he was endowed with virtues of which Dodington never dreamed.

The name of Lord Chesterfield is in the air just now. Within the last few months the curiosity of the world has been stimulated and satisfied by the publication of some hitherto unknown letters by Lord Chesterfield. The pleasure which the student of history has taken in this new find is just dimmed at this moment by the death of Lord Carnarvon, whose care and scholarship gave them to the worlds. They are indeed a precious possession. A very eminent French critic, M. Brunetière, has inveighed lately with much justice against the passion for raking together and bringing out all manner of unpublished writings. He complains, and complains with justice, that while the existing classics of literature are left imperfectly edited, if not ignored, the activity of students is devoted to burrowing out all manner of unimportant material, anything, everything, so long as it has not been known beforehand to the world. The French critic protests against the class of scholars who go into ecstacies over a newly discovered washing list of Pascal or a bill from Racine's perruquier. The complaint tells against us as well on our side of the Channel. We hear a great deal [xx]about newly discovered fragments by this great writer and that great writer, which are of no value whatever, except that they happen to be new. But no such stricture applies to the letters of Lord Chesterfield which the late Lord Carnarvon so recently gave to the world. They are a valuable addition to our knowledge of the last century, a valuable addition to our knowledge of the man who wrote them. And knowledge about Lord Chesterfield is always welcome. Few of the famous figures of the last century have been more misunderstood than he. The world is too ready to remember Johnson's biting letter; too ready to remember the cruel caricatures of Lord Hervey. Even the famous letters have been taken too much at Johnson's estimate, and Johnson's estimate was one-sided and unfair. A man would not learn the highest life from the Chesterfield letters; they have little in common with the ethics of an A Kempis, a Jean Paul Richter, or a John Stuart Mill. But they have their value in their way, and if they contain some utterances so unutterably foolish as those in which Lord Chesterfield expressed himself upon Greek literature, they contain some very excellent maxims for the management of social life. Nobody could become a penny the worse for the study of Chesterfield; many might become the better. They are not a whit more cynical than, indeed they are not so cynical as, those letters of Thackeray's to young Brown, which with all their cleverness make us understand what Mr. Henley means when in his "Views and Reviews" he describes him as a "writer of genius who was innately and irredeemably a Philistine". The letters of Lord Chesterfield would not do much to make a man a [xxi]hero, but there is little in literature more unheroic than the letters to Mr. Thomas Brown the younger.

It is curious to contrast the comparative enthusiasm with which the Whartons write about Horace Walpole with the invective of Lord Macaulay. To the great historian Walpole was the most eccentric, the most artificial, the most capricious of men, who played innumerable parts and over-acted them all, a creature to whom whatever was little seemed great and whatever was great seemed little. To Macaulay he was a gentleman-usher at heart, a Republican whose Republicanism like the courage of a bully or the love of a fribble was only strong and ardent when there was no occasion for it, a man who blended the faults of Grub Street with the faults of St. James's Street, and who united to the vanity, the jealousy and the irritability of a man of letters, the affected superciliousness and apathy of a man of ton. The Whartons over-praise Walpole where Lord Macaulay under-rates him; the truth lies between the two. He was not in the least an estimable or an admirable figure, but he wrote admirable, indeed incomparable letters to which the world is indebted beyond expression. If we can almost say that we know the London of the last century as well as the London of to-day it is largely to Horace Walpole's letters that our knowledge is due. They can hardly be over-praised, they can hardly be too often read by the lover of last century London. Horace Walpole affected to despise men of letters. It is his punishment that his fame depends upon his letters, those letters which, though their writer was all unaware of it, are genuine literature, and almost of the best.

We could linger over almost every page of the [xxii]Whartons' volumes, for every page is full of pleasant suggestions. The name of George Villiers, second Duke of Buckingham brings up at once a picture of perhaps the brilliantest and basest period in English history. It brings up too memories of a fiction that is even dearer than history, of that wonderful romance of Dumas the Elder's, which Mr. Louis Stevenson has placed among the half-dozen books that are dearest to his heart, the "Vicomte de Bragelonne". Who that has ever followed, breathless and enraptured, the final fortunes of that gallant quadrilateral of musketeers will forget the part which is played by George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, in that magnificent prose epic? There is little to be said for the real Villiers; he was a profligate and a scoundrel, and he did not show very heroically in his quarrel with the fiery young Ossory. It was one thing to practically murder Lord Shrewsbury; it was quite another thing to risk the wrath and the determined right hand of the Duke of Ormond's son. But the Villiers of Dumas' fancy is a fairer figure and a finer lover, and it is pleasant after reading the pages in which the authors of these essays trace the career of Dryden's epitome to turn to those volumes of the great Frenchman, to read the account of the duel with de Wardes and invoke a new blessing on the muse of fiction.

In some earlier volumes of the same great series we meet with yet another figure who has his image in the Wharton picture gallery. In that "crowded and sunny field of life"—the words are Mr. Stevenson's, and they apply to the whole musketeer epic—that "place busy as a city, bright as a theatre, thronged with memorable faces, and sounding with delightful speech," the Abbé Scarron plays his part. It was here that many of us [xxiii]met Scarron for the first time, and if we have got to know him better since, we still remember with a thrill of pleasure that first encounter when in the society of the matchless Count de la Fere and the marvellous Aramis we made our bow in company with the young Raoul to the crippled wit and his illustrious companions. The Whartons write brightly about Scarron, but their best merit to my mind is that they at once prompt a desire to go to that corner of the bookshelf where the eleven volumes of the adventures of the immortal musketeers repose, and taking down the first volume of "Vingt Ans Après" seek for the twenty-third chapter, where Scarron receives society in his residence in the Rue des Tournelles. There Scudery twirls his moustaches and trails his enormous rapier and the Coadjutor exhibits his silken "Fronde". There the velvet eyes of Mademoiselle d'Aubigné smile and the beauty of Madame de Chevreuse delights, and all the company make fun of Mazarin and recite the verses of Voiture.

There are others of these wits and beaux with whom we might like to linger; but our space is running short; it is time to say good-bye. Congreve the dramatist and gentleman, Rochefoucault the wit, Saint-Simon the king of memoir-writers, Rochester and St. Evremond and de Grammont, Selwyn and Sydney Smith and Sheridan each in turn appeals to us to tarry a little longer. But it is time to say good-bye to these shadows of the past with whom we have spent some pleasant hours. It is their duty now to offer some pleasant hours to others.

Justin Huntly M'Carthy.[xxiv]

In revising this Publication, it has scarcely been found necessary to recall a single opinion relative to the subject of the Work. The general impressions of characters adopted by the Authors have received little modification from any remarks elicited by the appearance of 'The Wits and Beaux of Society.'

It is scarcely to be expected that even our descendants will know much more of the Wits and Beaux of former days than we now do. The chests at Strawberry Hill are cleared of their contents; Horace Walpole's latest letters are before us; Pepys and Evelyn have thoroughly dramatized the days of Charles II.; Lord Hervey's Memoirs have laid bare the darkest secrets of the Court in which he figures; voluminous memoirs of the less historic characters among the Wits and Beaux have been published; still it is possible that some long-disregarded treasury of old letters, like that in the Gallery at Wotton, may come to light. From that precious deposit a housemaid—blotted for ever be her name from memory's page—was purloining sheets of yellow paper, with antiquated writing on them, to light her fires with, when the late William Upcott came to the rescue, [xxvi]and saved Evelyn's 'Diary' for a grateful world. It is just possible that such a discovery may again be made, and that the doings of George Villiers, or the exile life of Wharton, or the inmost thoughts of other Wits and Beaux may be made to appear in clearer lights than heretofore; but it is much more likely that the popular opinions about these witty, worthless men are substantially true.

All that has been collected, therefore, to form this work—and, as in the 'Queens of Society,' every known source has been consulted—assumes a sterling value as being collected; and, should hereafter fresh materials be disinterred from any old library closet in the homes of some one descendant of our heroes, advantage will be gladly taken to improve, correct, and complete the lives.

One thing must, in justice, be said: if they have been written freely, fearlessly, they have been written without passion or prejudice. The writers, though not quite of the stamp of persons who would never have 'dared to address' any of the subjects of their biography, 'save with courtesy and obeisance,' have no wish to 'trample on the graves' of such very amusing personages as the 'Wits and Beaux of Society.' They have even been lenient to their memory, hailing every good trait gladly, and pointing out with no unsparing hand redeeming virtues; and it cannot certainly be said, in this instance, that the good has been 'interred with the bones' of the personages herein described, although the evil men do, 'will live after them.'

But whilst a biographer is bound to give the fair as well as the dark side of his subject, he has still to remember that biography is a trust, and that it should not be an eulogium. It is his duty to reflect that in many instances it must be regarded even as a warning.

The moral conclusions of these lives of 'Wits and Beaux' [xxvii]are, it is admitted, just: vice is censured; folly rebuked; ungentlemanly conduct, even in a beau of the highest polish, exposed; irreligion finds no toleration under gentle names—heartlessness no palliation from its being the way of the world. There is here no separate code allowed for men who live in the world, and for those who live out of it. The task of pourtraying such characters as the 'Wits and Beaux of Society' is a responsible one, and does not involve the mere attempt to amuse, or the mere desire to abuse, but requires truth and discrimination; as embracing just or unjust views of such characters, it may do much harm or much good. Nevertheless, in spite of these obvious considerations there do exist worthy persons, even in the present day, so unreasonable as to take offence at the revival of old stories anent their defunct grandfathers, though those very stories were circulated by accredited writers employed by the families themselves. Some individuals are scandalized when a man who was habitually drunk, is called a drunkard; and ears polite cannot bear the application of plain names to well-known delinquencies.

There is something foolish, but respectably foolish, in this wish to shut out light which has been streaming for years over these old tombs and memories. The flowers that are cast on such graves cannot, however, cause us to forget the corruption within and underneath. In consideration, nevertheless, of a pardonable weakness, all expressions that can give pain, or which have been said to give pain, have been, in this Second Edition, omitted; and whenever a mis-statement has crept in, care has been taken to amend the error.[xxviii]

The success of the 'Queens of Society' will have pioneered the way for the 'Wits and Beaux:' with whom, during the holiday time of their lives, these fair ladies were so greatly associated. The 'Queens,' whether all wits or not, must have been the cause of wit in others; their influence over dandyism is notorious: their power to make or mar a man of fashion, almost historical. So far, a chronicle of the sayings and doings of the 'Wits' is worthy to serve as a pendant to that of the 'Queens:' happy would it be for society if the annals of the former could more closely resemble the biography of the latter. But it may not be so: men are subject to temptations, to failures, to delinquencies, to calamities, of which women can scarcely dream, and which they can only lament and pity.

Our 'Wits,' too—to separate them from the 'Beaux'—were men who often took an active part in the stirring events of their day: they assumed to be statesmen, though, too frequently, they were only politicians. They were brave and [xxx]loyal: indeed, in the time of the Stuarts, all the Wits were Cavaliers, as well as the Beaux. One hears of no repartee among Cromwell's followers; no dash, no merriment, in Fairfax's staff; eloquence, indeed, but no wit in the Parliamentarians; and, in truth, in the second Charles's time, the king might have headed the lists of the Wits himself—such a capital man as his Majesty is known to have been for a wet evening or a dull Sunday; such a famous teller of a story—such a perfect diner-out: no wonder that in his reign we had George Villiers, second Duke of Buckingham of that family, 'mankind's epitome,' who had every pretension to every accomplishment combined in himself. No wonder we could attract De Grammont and Saint Evremond to our court; and own, somewhat to our discredit be it allowed, Rochester and Beau Fielding. Every reign has had its wits, but those in Charles's time were so numerous as to distinguish the era by an especial brilliancy. Nor let it be supposed that these annals do not contain a moral application. They show how little the sparkling attributes herein pourtrayed conferred happiness; how far more the rare, though certainly real touches of genuine feeling and strong affection, which appear here and there even in the lives of the most thoughtless 'Wits and Beaux,' elevate the character in youth, or console the spirit in age. They prove how wise has been that change in society which now repudiates the 'Wit' as a distinct class; and requires general intelligences as a compensation for lost repartees, or long obsolete practical jokes.

'Men are not all evil:' so in the life of George Villiers, we find him kind-hearted, and free from hypocrisy. His old servants—and the fact speaks in extenuation of one of our wildest Wits and Beaux—loved him faithfully. De Grammont, we all own, has little to redeem him except his good-nature: Rochester's latest days were almost hallowed by his penitence. [xxxi]Chesterfield is saved by his kindness to the Irish, and his affection for his son. Horace Walpole had human affections, though a most inhuman pen: and Wharton was famous for his good-humour.

The periods most abounding in the Wit and the Beau have, of course, been those most exempt from wars, and rumours of wars. The Restoration; the early period of the Augustan age; the commencement of the Hanoverian dynasty,—have all been enlivened by Wits and Beaux, who came to light like mushrooms after a storm of rain, as soon as the political horizon was clear. We have Congreve, who affected to be the Beau as well as the Wit; Lord Hervey, more of the courtier than the Beau—a Wit by inheritance—a peer, assisted into a pre-eminent position by royal preference, and consequent prestige; and all these men were the offspring of the particular state of the times in which they figured: at earlier periods, they would have been deemed effeminate; in later ones, absurd.

Then the scene shifts: intellect had marched forward gigantically: the world is grown exacting, disputatious, critical, and such men as Horace Walpole and Brinsley Sheridan appear; the characteristics of wit which adorned that age being well diluted by the feebler talents of Selwyn and Hook.

Of these, and others, 'table traits,' and other traits, are here given: brief chronicles of their life's stage, over which a curtain has so long been dropped, are supplied carefully from well established sources: it is with characters, not with literary history, that we deal; and do our best to make the portraitures life-like, and to bring forward old memories, which, without the stamp of antiquity, might be suffered to pass into obscurity.

Your Wit and your Beau, be he French or English, is no mediæval personage: the aristocracy of the present day rank [xxxii]among his immediate descendants: he is a creature of a modern and an artificial age; and with his career are mingled many features of civilized life, manners, habits, and traces of family history which are still, it is believed, interesting to the majority of English readers, as they have long been to

Grace and Philip Wharton

October, 1860.

Signs of the Restoration.—Samuel Pepys in his Glory.—A Royal Company.—Pepys 'ready to Weep.'—The Playmate of Charles II.—George Villiers's Inheritance.—Two Gallant Young Noblemen.—The Brave Francis Villiers.—After the Battle of Worcester.—Disguising the King.—Villiers in Hiding.—He appears as a Mountebank.—Buckingham's Habits.—A Daring Adventure.—Cromwell's Saintly Daughter.—Villiers and the Rabbi.—The Buckingham Pictures and Estates.—York House.—Villiers returns to England.—Poor Mary Fairfax.—Villiers in the Tower.—Abraham Cowley, the Poet.—The Greatest Ornament of Whitehall.—Buckingham's Wit and Beauty.—Flecknoe's Opinion of Him.—His Duel with the Earl of Shrewsbury.—Villiers as a Poet.—As a Dramatist.—A Fearful Censure!—Villiers's Influence in Parliament.—A Scene in the Lords.—The Duke of Ormond in Danger.—Colonel Blood's Outrages.—Wallingford House and Ham House.—'Madame Ellen.'—The Cabal.—Villiers again in the Tower.—A Change.—The Duke of York's Theatre.—Buckingham and the Princess of Orange.—His last Hours.—His Religion.—Death of Villiers.—The Duchess of Buckingham.

Samuel Pepys, the weather-glass of his time, hails the first glimpse of the Restoration of Charles II. in his usual quaint terms and vulgar sycophancy.

'To Westminster Hall,' says he; 'where I heard how the Parliament had this day dissolved themselves, and did pass very cheerfully through the Hall, and the Speaker without his mace. The whole Hall was joyful thereat, as well as themselves; and now they begin to talk loud of the king.' And the evening was closed, he further tells us, with a large bonfire in the Exchange, and people called out, 'God bless King Charles!'

This was in March 1660; and during that spring Pepys was [2]noting down how he did not think it possible that my 'Lord Protector,' Richard Cromwell, should come into power again; how there were great hopes of the king's arrival; how Monk, the Restorer, was feasted at Mercers' Hall (Pepys's own especial); how it was resolved that a treaty be offered to the king, privately; how he resolved to go to sea with 'my lord:' and how, while they lay at Gravesend, the great affair which brought back Charles Stuart was virtually accomplished. Then, with various parentheses, inimitable in their way, Pepys carries on his narrative. He has left his father's 'cutting-room' to take care of itself; and finds his cabin little, though his bed is convenient, but is certain, as he rides at anchor with 'my lord,' in the ship, that the king 'must of necessity come in,' and the vessel sails round and anchors in Lee Roads. 'To the castles about Deal, where our fleet' (our fleet, the saucy son of a tailor!) 'lay and anchored; great was the shoot of guns from the castles, and ships, and our answers.' Glorious Samuel! in his element, to be sure.

Then the wind grew high: he began to be 'dizzy, and squeamish;' nevertheless employed 'Lord's Day' in looking through the lieutenant's glass at two good merchantmen, and the women in them; 'being pretty handsome;' then in the afternoon he first saw Calais, and was pleased, though it was at a great distance. All eyes were looking across the Channel just then—for the king was at Flushing; and, though the 'Fanatiques' still held their heads up high, and the Cavaliers also talked high on the other side, the cause that Pepys was bound to, still gained ground.

Then 'they begin to speak freely of King Charles;' churches in the City, Samuel declares, were setting up his arms; merchant-ships—more important in those days—were hanging out his colours. He hears, too, how the Mercers' Company were making a statue of his gracious Majesty to set up in the Exchange. Ah! Pepys's heart is merry: he has forty shillings (some shabby perquisite) given him by Captain Cowes of the 'Paragon;' and 'my lord' in the evening 'falls to singing' a song upon the Rump to the tune of the 'Blacksmith.'

The hopes of the Cavalier party are hourly increasing, and those of Pepys we may be sure also; for Pim, the tailor, spends a morning in his cabin 'putting a great many ribbons to a sail.' And the king is to be brought over suddenly, 'my lord' tells him: and indeed it looks like it, for the sailors are drinking Charles's health in the streets of Deal, on their knees; 'which, methinks,' says Pepys, 'is a little too much;' and 'methinks' so, worthy Master Pepys, also.

Then how the news of the Parliamentary vote of the king's declaration was received! Pepys becomes eloquent.

'He that can fancy a fleet (like ours) in her pride, with pendants loose, guns roaring, caps flying, and the loud "Vive le Roi!" echoed from one ship's company to another; he, and he only, can apprehend the joy this enclosed vote was received with, or the blessing he thought himself possessed of that bore it.'

Next, orders come for 'my lord' to sail forthwith to the king; and the painters and tailors set to work, Pepys superintending, 'cutting out some pieces of yellow cloth in the fashion of a crown and C. R.; and putting it upon a fine sheet'—and that is to supersede the States' arms, and is finished and set up. And the next day, on May 14, the Hague is seen plainly by us, 'my lord going up in his night-gown into the cuddy.'

And then they land at the Hague; some 'nasty Dutchmen' come on board to offer their boats, and get money, which Pepys does not like; and in time they find themselves in the Hague, 'a most neat place in all respects:' salute the Queen of Bohemia and the Prince of Orange—afterwards William III.—and find at their place of supper nothing but a 'sallet' and two or three bones of mutton provided for ten of us, 'which was very strange. Nevertheless, on they sail, having returned to the fleet, to Schevelling: and, on the 23rd of the month, go to meet the king; who, 'on getting into the boat, did kiss my lord with much affection.' And 'extraordinary press of good company,' and great mirth all day, announced the Restoration. Nevertheless Charles's clothes [4]had not been, till this time, Master Pepys is assured, worth forty shillings—and he, as a connoisseur, was scandalized at the fact.

And now, before we proceed, let us ask who worthy Samuel Pepys was, that he should pass such stringent comments on men and manners? His origin was lowly, although his family ancient; his father having followed, until the Restoration, the calling of a tailor. Pepys, vulgar as he was, had nevertheless received an university education; first entering Trinity College, Cambridge, as a sizar. To our wonder we find him marrying furtively and independently; and his wife, at fifteen, was glad with her husband to take up an abode in the house of a relative, Sir Edward Montagu, afterwards Earl of Sandwich, the 'my lord' under whose shadow Samuel Pepys dwelt in reverence. By this nobleman's influence Pepys for ever left the 'cutting-room;' he acted first as secretary, (always as toad-eater, one would fancy), then became a clerk in the Admiralty; and as such went, after the Restoration, to live in Seething Lane, in the parish of St. Olave, Hart Street—and in St. Olave his mortal part was ultimately deposited.

So much for Pepys. See him now, in his full-buttoned wig, and best cambric neckerchief, looking out for the king and his suit, who are coming on board the 'Nazeby.'

'Up, and made myself as fine as I could, with the linning stockings on, and wide canons that I bought the other day at the Hague.' So began he the day. 'All day nothing but lords and persons of honour on board, that we were exceeding full. Dined in great deal of state, the royalle company by themselves in the coache, which was a blessed sight to see.' This royal company consisted of Charles, the Dukes of York and Gloucester, his brothers, the Queen of Bohemia, the Princess Royal, the Prince of Orange, afterwards William III.—all of whose hands Pepys kissed, after dinner. The King and Duke of York changed the names of the ships. The 'Rumpers,' as Pepys calls the Parliamentarians, had given one the name of the 'Nazeby;' and that was now christened the 'Charles:' 'Richard' was changed into 'James.' The 'Speaker' into 'Mary,' the 'Lambert,' was 'Henrietta,' and so on. How [5]merry the king must have been whilst he thus turned the Roundheads, as it were, off the ocean; and how he walked here and there, up and down, (quite contrary to what Samuel Pepys 'expected,') and fell into discourse of his escape from Worcester, and made Samuel 'ready to weep' to hear of his travelling four days and three nights on foot, up to his knees in dirt, with 'nothing but a green coat and a pair of breeches on,' (worse and worse, thought Pepys,) and a pair of country shoes that made his feet sore; and how, at one place he was made to drink by the servants, to show he was not a Roundhead; and how, at another place—and Charles, the best teller of a story in his own dominions, may here have softened his tone—the master of the house, an innkeeper, as the king was standing by the fire, with his hands on the back of a chair, kneeled down and kissed his hand 'privately,' saying he could not ask him who he was, but bid 'God bless him, where he was going!'

Then, rallying after this touch of pathos, Charles took his hearers over to Fecamp, in France—thence to Rouen, where, he said, in his easy, irresistible way, 'I looked so poor that the people went into the rooms before I went away, to see if I had not stolen something or other.'

With what reverence and sympathy did our Pepys listen; but he was forced to hurry off to get Lord Berkeley a bed; and with 'much ado' (as one may believe) he did get 'him to bed with My Lord Middlesex;' so, after seeing these two peers of the realm in that dignified predicament—two in a bed—'to my cabin again,' where the company were still talking of the king's difficulties, and how his Majesty was fain to eat a piece of bread and cheese out of a poor body's pocket; and, at a Catholic house, how he lay a good while 'in the Priest's Hole, for privacy.'

In all these hairbreadth escapes—of which the king spoke with infinite humour and good feeling—one name was perpetually introduced:—George—George Villiers, Villers, as the royal narrator called him; for the name was so pronounced formerly. And well he might; for George Villiers had been his playmate, classfellow, nay, bedfellow sometimes, in priests' [6]holes; their names, their haunts, their hearts, were all assimilated; and misfortune had bound them closely to each other. To George Villiers let us now return; he is waiting for his royal master on the other side of the Channel—in England. And a strange character have we to deal with:—

'A man so various, that he seemed to be

Not one, but all mankind's epitome:

Stiff in opinions, always in the wrong,

Was everything by starts, and nothing long;

But, in the course of one revolving moon,

Was chemist, fiddler, statesman, and buffoon.'[1]

Such was George Villiers: the Alcibiades of that age. Let us trace one of the most romantic, and brilliant, and unsatisfactory lives that has ever been written.

George Villiers was born at Wallingford House, in the parish of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, on the 30th January, 1627. The Admiralty now stands on the site of the mansion in which he first saw the light. His father was George Villiers, the favourite of James I. and of Charles I.; his mother, the Lady Katherine Manners, daughter and heiress of Francis, Earl of Rutland. Scarcely was he a year old, when the assassination of his father, by Felton, threw the affairs of his family into confusion. His mother, after the Duke of Buckingham's death, gave birth to a son, Francis; who was subsequently, savagely killed by the Roundheads, near Kingston. Then the Duchess of Buckingham very shortly married again, and uniting herself to Randolph Macdonald, Earl of Antrim, became a rigid Catholic. She was therefore lost to her children, or rather, they were lost to her; for King Charles I., who had promised to be a 'husband to her, and a father to her children,' removed them from her charge, and educated them with the royal princes.

The youthful peer soon gave indications of genius; and all that a careful education could do, was directed to improve his natural capacity under private tutors. He went to Cambridge; and thence, under the care of a preceptor named Aylesbury, travelled into France. He was accompanied by his young, [7]handsome, fine-spirited brother, Francis; and this was the sunshine of his life. His father had indeed left him, as his biographer Brian Fairfax expresses it, 'the greatest name in England; his mother, the greatest estate of any subject.' With this inheritance there had also descended to him the wonderful beauty, the matchless grace, of his ill-fated father. Great abilities, courage, fascination of manners, were also his; but he had not been endowed with firmness of character, and was at once energetic and versatile. Even at this age, the qualities which became his ruin were clearly discoverable.

George Villiers was recalled to England by the troubles which drove the king to Oxford, and which converted that academical city into a garrison, its under-graduates into soldiers, its ancient halls into barrack-rooms. Villiers was on this occasion entered at Christ Church: the youth's best feelings were aroused, and his loyalty was engaged to one to whom his father owed so much. He was now a young man of twenty-one years of age—able to act for himself; and he went heart and soul into the cause of his sovereign. Never was there a gayer, a more prepossessing Cavalier. He could charm even a Roundhead. The harsh and Presbyterian-minded Bishop Burnet, has told us that 'he was a man of a noble presence; had a great liveliness of wit, and a peculiar faculty of turning everything into ridicule, with bold figures and natural descriptions.' How invaluable he must have been in the Common-rooms at Oxford, then turned into guard-rooms, his eye upon some unlucky volunteer Don, who had put off his clerkly costume for a buff jacket, and could not manage his drill. Irresistible as his exterior is declared to have been, the original mind of Villiers was even far more influential. De Grammont tells us, 'he was extremely handsome, but still thought himself much more so than he really was; although he had a great deal of discernment, yet his vanities made him mistake some civilities as intended for his person which were only bestowed on his wit and drollery.'

But this very vanity, so unpleasant in an old man, is only amusing in a younger wit. Whilst thus a gallant of the court and camp, the young nobleman proved himself to be no less brave than witty. Juvenile as he was, with a brother still [8]younger, they fought on the royalist side at Lichfield, in the storming of the Cathedral Close. For thus allowing their lives to be endangered, their mother blamed Lord Gerard, one of the Duke's guardians; whilst the Parliament seized the pretext of confiscating their estates, which were afterwards returned to them, on account of their being under age at the time of confiscation. The youths were then placed under the care of the Earl of Northumberland, by whose permission they travelled in France and Italy, where they appeared—their estates having been restored—with princely magnificence. Nevertheless, on hearing of the imprisonment of Charles I. in the Isle of Wight, the gallant youths returned to England and joined the army under the Earl of Holland, who was defeated near Nonsuch, in Surrey.

A sad episode in the annals of these eventful times is presented in the fate of the handsome, brave Francis Villiers. His murder, for one can call it by no other name, shows how keenly the personal feelings of the Roundheads were engaged in this national quarrel. Under most circumstances, Englishmen would have spared the youth, and respected the gallantry of the free young soldier, who, planting himself against an oak-tree which grew in the road, refused to ask for quarter, but defended himself against several assailants. But the name of Villiers was hateful in Puritan ears. 'Hew them down, root and branch!' was the sentiment that actuated the soldiery. His very loveliness exasperated their vengeance. At last, 'with nine wounds on his beautiful face and body,' says Fairfax, 'he was slain.' 'The oak-tree,' writes the devoted servant, 'is his monument,' and the letters of F. V. were cut in it in his day. His body was conveyed by water to York House, and was entombed with that of his father, in the Chapel of Henry VII.

His brother fled towards St. Neot's, where he encountered a strange kind of peril. Tobias Rustat attended him; and was with him in the rising in Kent for King Charles I., wherein the Duke was engaged; and they, being put to the flight, the Duke's helmet, by a brush under a tree, was turned upon his back, and tied so fast with a string under his throat, 'that without the pre[9]sent help of T. R.,' writes Fairfax, 'it had undoubtedly choked him, as I have credibly heard.'[2]

Whilst at St. Neot's, the house in which Villiers had taken refuge was surrounded with soldiers. He had a stout heart, and a dexterous hand; he took his resolution; rushed out upon his foes, killed the officer in command, galloped off and joined the Prince in the Downs.

The sad story of Charles I. was played out; but Villiers remained stanch, and was permitted to return and to accompany Prince Charles into Scotland. Then came the battle of Worcester in 1651: there Charles II. showed himself a worthy descendant of James IV. of Scotland. He resolved to conquer or die: with desperate gallantry the English Cavaliers and the Scotch Highlanders seconded the monarch's valiant onslaught on Cromwell's horse, and the invincible Life Guards were almost driven back by the shock. But they were not seconded; Charles II. had his horse twice shot under him, but, nothing daunted, he was the last to tear himself away from the field, and then only upon the solicitations of his friends.

Charles retired to Kidderminster that evening. The Duke of Buckingham, the gallant Lord Derby, Wilmot, afterwards Earl of Rochester, and some others, rode near him. They were followed by a small body of horse. Disconsolately they rode on northwards, a faithful band of sixty being resolved to escort his Majesty to Scotland. At length they halted on Kinver Heath, near Kidderminster: their guide having lost the way. In this extremity Lord Derby said that he had been received kindly at an old house in a secluded woody country, between Tong Castle and Brewood, on the borders of Staffordshire. It was named 'Boscobel,' he said; and that word has henceforth conjured up to the mind's eye the remembrance of a band of tired heroes, riding through woody glades to an ancient house, where shelter was given to the worn-out horses and scarcely less harassed riders.

But not so rapidly did they in reality proceed. A Catholic family, named Giffard, were living at White-Ladies, about twenty six miles from Worcester. This was only about half a mile from Boscobel: it had been a convent of Cistercian nuns, whose long white cloaks of old had once been seen, ghost-like, amid forest glades or on hillock green. The White-Ladies had other memories to grace it besides those of holy vestals, or of unholy Cavaliers. From the time of the Tudors, a respectable family named Somers had owned the White-Ladies, and inhabited it since its white-garbed tenants had been turned out, and the place secularized. 'Somers's House,' as it was called, (though more happily, the old name has been restored,) had received Queen Elizabeth on her progress. The richly cultivated old conventual gardens had supplied the Queen with some famous pears, and, in the fulness of her approval of the fruit, she had added them to the City arms. At that time one of these vaunted pear-trees stood securely in the market-place of Worcester.

At the White-Ladies, Charles rested for half an hour; and here he left his garters, waistcoat, and other garments, to avoid discovery, ere he proceeded. They were long kept as relics.

The mother of Lord Somers had been placed in this old house for security, for she was on the eve of giving birth to the future statesman, who was born in that sanctuary just at this time. His father at that very moment commanded a troop of horse in Cromwell's army, so that the risk the Cavaliers ran was imminent. The King's horse was led into the hall. Day was dawning; and the Cavaliers, as they entered the old conventual tenement, and saw the sunbeams on its walls, perceived their peril. A family of servants named Penderell held various offices there, and at Boscobel. William took care of Boscobel, George was a servant at White-Ladies; Humphrey was the miller to that house, Richard lived close by, at Hebbal Grange. He and William were called into the royal presence. Lord Derby then said to them, 'This is the King; have a care of him, and preserve him as thou didst me.'

Then the attendant courtiers began undressing the King. They took off his buff-coat, and put on him a 'noggon coarse [11]shirt,' and a green suit and another doublet—Richard Penderell's woodman's dress. Lord Wilmot cut his sovereign's hair with a knife, but Richard Penderell took up his shears and finished the work. 'Burn it,' said the king; but Richard kept the sacred locks. Then Charles covered his dark face with soot. Could anything have taken away the expression of his half-sleepy, half-merry eyes?

They departed, and half an hour afterwards Colonel Ashenhurst, with a troop of Roundhead horse, rode up to the White-Ladies. The King, meantime, had been conducted by Richard Penderell into a coppice-wood, with a bill-hook in his hands for defence and disguise. But his followers were overtaken near Newport; and here Buckingham, with Lords Talbot and Leviston, escaped; and henceforth, until Charles's wanderings were transferred from England to France, George Villiers was separated from the Prince. Accompanied by the Earls of Derby and Lauderdale, and by Lord Talbot, he proceeded northwards, in hopes of joining General Leslie and the Scotch horse. But their hopes were soon dashed: attacked by a body of Roundheads, Buckingham and Lord Leviston were compelled to leave the high road, to alight from their horses, and to make their way to Bloore Park, near Newport, where Villiers found a shelter. He was soon, however, necessitated to depart: he put on a labourer's dress; he deposited his George, a gift from Henrietta Maria, with a companion, and set off for Billstrop, in Nottinghamshire, one Matthews, a carpenter, acting as his guide; at Billstrop he was welcomed by Mr. Hawley, a Cavalier; and from that place he went to Brookesby, in Leicestershire, the original seat of the Villiers family, and the birthplace of his father. Here he was received by Lady Villiers—the widow, probably, of his father's brother, Sir William Villiers, one of those contented country squires who not only sought no distinction, but scarcely thanked James I. when he made him a baronet. Here might the hunted refugee see, on the open battlements of the church, the shields on which were exhibited united quarterings of his father's family with those of his mother; here, listen to old tales about his grandfather, good Sir George, who married a serving-woman in his deceased wife's [12]kitchen;[3] and that serving-woman became the leader of fashions in the court of James. Here he might ponder on the vicissitudes which marked the destiny of the house of Villiers, and wonder what should come next.

That the spirit of adventure was strong within him, is shown by his daring to go up to London, and disguising himself as a mountebank. He had a coat made, called a 'Jack Pudding Coat:' a little hat was stuck on his head, with a fox's tail in it, and cocks' feathers here and there. A wizard's mask one day, a daubing of flour another, completed the disguise it was then so usual to assume: witness the long traffic held at Exeter Change by the Duchess of Tyrconnel, Francis Jennings, in a white mask, selling laces, and French gew-gaws, a trader to all appearance, but really carrying on political intrigues; every one went to chat with the 'White Milliner,' as she was called, during the reign of William and Mary. The Duke next erected a stage at Charing Cross—in the very face of the stern Rumpers, who, with long faces, rode past the sinful man each day as they came ambling up from the Parliament House. A band of puppet-players and violins set up their shows; and music covers a multitude of incongruities. The ballad was then the great vehicle of personal attack, and Villiers's dawning taste for poetry was shown in the ditties which he now composed, and in which he sometimes assisted vocally. Whilst all the other Cavaliers were forced to fly, he thus bearded his enemies in their very homes: sometimes he talked to them face to face, and kept the sanctimonious citizens in talk, till they found themselves sinfully disposed to laugh. But this vagrant life had serious evils: it broke down all the restraints which civilised society naturally, and beneficially, imposes. The Duke of Buckingham, Butler, the author of Hudibras, writes, 'rises, eats, goes to bed by the Julian account, long after all others that go by the new style, and keeps the same hours with owls and the Antipodes. He is a great observer of the Tartar cus[13]toms, and never eats till the great cham, having dined, makes proclamation that all the world may go to dinner. He does not dwell in his house, but haunts it like an evil spirit, that walks all night, to disturb the family, and never appears by day. He lives perpetually benighted, runs out of his life, and loses his time as men do their ways in the dark: and as blind men are led by their dogs, so he is governed by some mean servant or other that relates to his pleasures. He is as inconstant as the moon which he lives under; and although he does nothing but advise with his pillow all day, he is as great a stranger to himself as he is to the rest of the world. His mind entertains all things that come and go; but like guests and strangers, they are not welcome if they stay long. This lays him open to all cheats, quacks, and impostors, who apply to every particular humour while it lasts, and afterwards vanish. He deforms nature, while he intends to adorn her, like Indians that hang jewels in their lips and noses. His ears are perpetually drilling with a fiddlestick, and endures pleasures with less patience than other men do their pains.'

The more effectually to support his character as a mountebank, Villiers sold mithridate and galbanum plasters: thousands of spectators and customers thronged every day to see and hear him. Possibly many guessed that beneath all the fantastic exterior some ulterior project was concealed; yet he remained untouched by the City Guards. Well did Dryden describe him:—

'Then all for women, painting, rhyming, drinking,

Beside ten thousand freaks that died in thinking.

Blest madman, who could every hour employ

With something new to wish or to enjoy.'

His elder sister, Lady Mary Villiers, had married the Duke of Richmond, one of the loyal adherents of Charles I. The duke was, therefore, in durance at Windsor, whilst the duchess was to be placed under strict surveillance at Whitehall.

Villiers resolved to see her. Hearing that she was to pass into Whitehall on a certain day, he set up his stage where she could not fail to perceive him. He had something important to say to her. As she drew near, he cried out to the mob that [14]he would give them a song on the Duchess of Richmond and the Duke of Buckingham: nothing could be more acceptable. 'The mob,' it is related, 'stopped the coach and the duchess ... Nay, so outrageous were the mob, that they forced the duchess, who was then the handsomest woman in England, to sit in the boot of the coach, and to hear him sing all his impertinent songs. Having left off singing, he told them it was no more than reason that he should present the duchess with some of the songs. So he alighted from his stage, covered all over with papers and ridiculous little pictures. Having come to the coach, he took off a black piece of taffeta, which he always wore over one of his eyes, when his sister discovered immediately who he was, yet had so much presence of mind as not to give the least sign of mistrust; nay, she gave him some very opprobrious language, but was very eager at snatching the papers he threw into her coach. Among them was a packet of letters, which she had no sooner got but she went forward, the duke, at the head of the mob, attending and hallooing her a good way out of the town.'

A still more daring adventure was contemplated also by this young, irresistible duke. Bridget Cromwell, the eldest daughter of Oliver, was, at that time, a bride of twenty-six years of age; having married, in 1647, the saintly Henry Ireton, Lord Deputy of Ireland. Bridget was the pattern heroine of the 'unco guid,' the quintessence of all propriety; the impersonation of sanctity; an ultra republican, who scarcely accorded to her father the modest title of Protector. She was esteemed by her party a 'personage of sublime growth:' 'humbled, not exalted,' according to Mrs. Hutchinson, by her elevation: 'nevertheless,' says that excellent lady, 'as my Lady Ireton was walking in the St. James's Park, the Lady Lambert, as proud as her husband, came by where she was, and as the present princess always hath precedency of the relict of the dead, so she put by my Lady Ireton, who, notwithstanding her piety and humility, was a little grieved at the affront.'

After this anecdote one cannot give much credence to this lady's humility: Bridget was, however, a woman of powerful intellect, weakened by her extreme, and, to use a now common [15]term, crochety opinions. Like most esprits forts, she was easily imposed upon. One day this paragon saw a mountebank dancing on a stage in the most exquisite style. His fine shape, too, caught the attention of one who assumed to be above all folly. It is sometimes fatal to one's peace to look out of a window; no one knows what sights may rivet or displease. Mistress Ireton was sitting at her window unconscious that any one with the hated and malignant name of 'Villiers' was before her. After some unholy admiration, she sent to speak to the mummer. The duke scarcely knew whether to trust himself in the power of the bloodthirsty Ireton's bride or not—yet his courage—his love of sport—prevailed. He visited her that evening: no longer, however, in his jack-pudding coat, but in a rich suit, disguised with a cloak over it. He wore still a plaster over one eye, and was much disposed to take it off, but prudence forbade; and thus he stood in the presence of the prim and saintly Bridget Ireton. The particulars of the interview rest on his statement, and they must not, therefore, be accepted implicitly. Mistress Ireton is said to have made advances to the handsome incognito. What a triumph to a man like Villiers, to have intrigued with my Lord Protector's sanctified daughter! But she inspired him with disgust. He saw in her the presumption and hypocrisy of her father; he hated her as Cromwell's daughter and Ireton's wife. He told her, therefore, that he was a Jew, and could not by his laws become the paramour of a Christian woman. The saintly Bridget stood amazed; she had imprudently let him into some of the most important secrets of her party. A Jew! It was dreadful! But how could a person of that persuasion be so strict, so strait-laced? She probably entertained all the horror of Jews which the Puritanical party cherished as a virtue; forgetting the lessons of toleration and liberality inculcated by Holy Writ. She sent, however, for a certain Jewish Rabbi to converse with the stranger. What was the Duke of Buckingham's surprise, on visiting her one evening, to see the learned doctor armed at all points with the Talmud, and thirsting for dispute, by the side of the saintly Bridget. He could noways meet such a body of controversy; but thought it best forthwith to set off for the [16]Downs. Before he departed he wrote, however, to Mistress Ireton, on the plea that she might wish to know to what tribe of Jews he belonged. So he sent her a note written with all his native wit and point.[4]

Buckingham now experienced all the miseries that a man of expensive pleasures with a sequestrated estate is likely to endure. One friend remained to watch over his interests in England. This was John Traylman, a servant of his late father's, who was left to guard the collection of pictures made by the late duke, and deposited in York House. That collection was, in the opinion of competent judges, the third in point of value in England, being only inferior to those of Charles I. and the Earl of Arundel.

It had been bought, with immense expense, partly by the duke's agents in Italy, the Mantua Gallery supplying a great portion—partly in France—partly in Flanders; and to Flanders a great portion was destined now to return. Secretly and laboriously did old Traylman pack up and send off these treasures to Antwerp, where now the gay youth whom the aged domestic had known from a child was in want and exile. The pictures were eagerly bought by a foreign collector named Duart. The proceeds gave poor Villiers bread; but the noble works of Titian and Leonardo da Vinci, and others, were lost for ever to England.

It must have been very irritating to Villiers to know that whilst he just existed abroad, the great estates enjoyed by his father were being subjected to pillage by Cromwell's soldiers, or sold for pitiful sums by the Commissioners appointed by the Parliament to break up and annihilate many of the old properties in England. Burleigh-on-the-Hill, the stately seat on which the first duke had lavished thousands, had been taken by the Roundheads. It was so large, and presented so long a line of buildings, that the Parliamentarians could not hold it without leaving in it a great garrison and stores of ammunition. It was therefore burnt, and the stables alone occupied; and those even were formed into a house of unusual size. York [17]House was doubtless marked out for the next destructive decree. There was something in the very history of this house which might be supposed to excite the wrath of the Roundheads. Queen Mary (whom we must not, after Miss Strickland's admirable life of her, call Bloody Queen Mary, but who will always be best known by that unpleasant title) had bestowed York House on the See of York, as a compensation for York House, at Whitehall, which Henry VIII. had taken from Wolsey. It had afterwards come into possession of the Keepers of the Great Seal. Lord Bacon was born in York House, his father having lived there; and the

'Greatest, wisest, meanest of mankind,'

built here an aviary which cost £300. When the Duke of Lennox wished to buy York House, Bacon thus wrote to him:—'For this you will pardon me: York House is the house where my father died, and where I first breathed; and there will I yield my last breath, if it so please God and the King.' It did not, however, please the King that he should; the house was borrowed only by the first Duke of Buckingham from the Archbishop of York, and then exchanged for another seat, on the plea that the duke would want it for the reception of foreign potentates, and for entertainments given to royalty.

The duke pulled it down: and the house, which was erected as a temporary structure, was so superb that even Pepys, twenty years after it had been left to bats and cobwebs, speaks of it in raptures, as of a place in which the great duke's soul was seen in every chamber. On the walls were shields on which the arms of Manners and of Villiers—peacocks and lions—were quartered. York House was never, however, finished; but as the lover of old haunts enters Buckingham Street in the Strand, he will perceive an ancient water-gate, beautifully proportioned, built by Inigo Jones—smoky, isolated, impaired—but still speaking volumes of remembrance of the glories of the assassinated duke, who had purposed to build the whole house in that style.

'Yorschaux,' as he called it—York House—the French ambassador had written word to his friends at home, 'is the [18]most richly fitted up of any that I saw.' The galleries and state rooms were graced by the display of the Roman marbles, both busts and statues, which the first duke had bought from Rubens; whilst in the gardens the Cain and Abel of John of Bologna, given by Philip IV. of Spain to King Charles, and by him bestowed on the elder George Villiers, made that fair pleasaunce famous. It was doomed—as were what were called the 'superstitious' pictures in the house—to destruction: henceforth all was in decay and neglect. 'I went to see York House and gardens,' Evelyn writes in 1655, 'belonging to the former greate Buckingham, but now much ruined through neglect.'

Traylman, doubtless, kept George Villiers the younger in full possession of all that was to happen to that deserted tenement in which the old man mourned for the departed, and thought of the absent.