The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Spinster Book, by Myrtle Reed This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Spinster Book Author: Myrtle Reed Release Date: March 29, 2006 [EBook #18071] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SPINSTER BOOK *** Produced by Susan Skinner and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS

New York and London

The Knickerbocker Press

1907

Copyright, 1901

BY

MYRTLE REED

Set up and electrotyped, September, 1901

Reprinted, November, 1901; April, 1902; August, 1902; April, 1903; July, 1903; September, 1903; June, 1904; October, 1904; June, 1905; September, 1905; March, 1906; September, 1906; November, 1906; July, 1907.

The Knickerbocker Press, New York

BY MYRTLE REED.

LOVE LETTERS OF A MUSICIAN.

LATER LOVE LETTERS OF A MUSICIAN.

THE SPINSTER BOOK.

LAVENDER AND OLD LACE.

PICKABACK SONGS.

THE SHADOW OF VICTORY.

THE MASTER'S VIOLIN.

THE BOOK OF CLEVER BEASTS.

AT THE SIGN OF THE JACK-O'-LANTERN.

A SPINNER IN THE SUN.

LOVE AFFAIRS OF LITERARY MEN.

If "the proper study of mankind is man," it is also the chief delight of woman. It is not surprising that men are conceited, since the thought of the entire population is centred upon them.

Women are wont to consider man in general as a simple creation. It is not until the individual comes into the field of the feminine telescope, and his peculiarities are thrown into high relief, that he is seen and judged at his true value.

When a girl once turns her attention from the species to the individual, her parlour becomes a sort of psychological laboratory in which she conducts various experiments; not, however, without the loss of friends. For men are impatient of the spirit of inquiry in woman.

How shall a girl acquire her knowledge of the phenomena of affection, if men are not[Pg 4] willing to be questioned upon the subject? What is more natural than to seek wisdom from the man a girl has just refused to marry? Why should she not ask if he has ever loved before, how long he has loved her, if he were not surprised when he found it out, and how he feels in her presence?

Yet a sensitive spinster is repeatedly astonished at finding her lover transformed into a fiend, without other provocation than this. He accuses her of being "a heartless coquette," of having "led him on,"—whatever that may mean,—and he does not care to have her for his sister, or even for his friend.

Occasionally a charitable man will open his heart for the benefit of the patient student. If he is of a scientific turn of mind, with a fondness for original research, he may even take a melancholy pleasure in the analysis.

Thus she learns that he thought he had loved, until he cared for her, but in the light of the new passion he sees clearly that the others were mere, idle flirtations. To her surprise, she also discovers that he has loved her a long time but has never dared to speak of it before, and that this feeling, compared[Pg 5] with the others, is as wine unto water. In her presence he is uplifted, exalted, and often afraid, for very love of her.

Next to a proposal, the most interesting thing in the world to a woman is this kind of analysis. If a man is clever at it, he may change a decided refusal to a timid promise to "think about it." The man who hesitates may be lost, but the woman who hesitates is surely won.

In the beginning, the student is often perplexed by the magnitude of the task which lies before her. Later, she comes to know that men, like cats, need only to be stroked in the right direction. The problem thus becomes a question of direction, which is seldom as simple as it looks.

Yet men, as a class, are easier to understand than women, because they are less emotional. It is emotion which complicates the personal equation with radicals and quadratics, and life which proceeds upon predestined lines soon becomes monotonous and loses its charm. The involved x in the equation continually postpones the definite result, which may often be surmised, but never achieved.[Pg 6]

Still, there is little doubt as to the proper method, for some of the radicals must necessarily appear in the result. Man's conceit is his social foundation and when the vulnerable spot is once found in the armour of Achilles, the overthrow of the strenuous Greek is near at hand.

There is nothing in the world as harmless and as utterly joyous as man's conceit. The woman who will not pander to it is ungracious indeed.

Man's interest in himself is purely altruistic and springs from an unselfish desire to please. He values physical symmetry because one's first impression of him is apt to be favourable. Manly accomplishments and evidences of good breeding are desirable for the same reason, and he likes to think his way of doing things is the best, regardless of actual effectiveness.

For instance, there seems to be no good reason why a man's way of sharpening a pencil is any better than a woman's. It is difficult to see just why it is advisable to cover the thumb with powdered graphite, and expose that useful member to possible amputation by a knife directed uncompromisingly[Pg 7] toward it, when the pencil might be pointed the other way, the risk of amputation avoided, and the shavings and pulverised graphite left safely to the action of gravitation and centrifugal force. Yet the entire race of men refuse to see the true value of the feminine method, and, indeed, any man would rather sharpen any woman's pencil than see her do it herself.

It pleases a man very much to be told that he "knows the world," even though his acquaintance be limited to the flesh and the devil—a gentleman, by the way, who is much misunderstood and whose faults are persistently exaggerated. But man's supreme conceit is in regard to his personal appearance. Let a single entry in a laboratory note-book suffice for proof.

Time, evening. Man is reading a story in a current magazine to the Girl he is calling upon.

Man. "Are you interested in this?"

Girl. "Certainly, but I can think of other things too, can't I?"

Man. "That depends on the 'other things.' What are they?"

Girl. (Calmly.) "I was just thinking that[Pg 8] you are an extremely handsome man, but of course you know that."

Man. (Crimsoning to his temples.) "You flatter me!" (Resumes reading.)

Girl. (Awaits developments.)

Man. (After a little.) "I didn't know you thought I was good-looking."

Girl. (Demurely.) "Didn't you?"

Man. (Clears his throat and continues the story.)

Man. (After a few minutes.) "Did you ever hear anybody else say that?"

Girl. "Say what?"

Man. "Why, that I was—that I was—well, good-looking, you know?"

Girl. "Oh, yes! Lots of people!"

Man. (After reading half a page.) "I don't think this is so very interesting, do you?"

Girl. "No, it isn't. It doesn't carry out the promise of its beginning."

Man. (Closes magazine and wanders aimlessly toward the mirror in the mantel.)

Man. "Which way do you like my hair; this way, or parted in the middle?"

Girl. "I don't know—this way, I guess. I've never seen it parted in the middle."[Pg 9]

Man. (Taking out pocket comb and rapidly parting his hair in the middle.) "There! Which way do you like it?"

Girl. (Judicially.) "I don't know. It's really a very hard question to decide."

Man. (Reminiscently.) "I've gone off my looks a good deal lately. I used to be a lot better looking than I am now."

Girl. (Softly.) "I'm glad I didn't know you then."

Man. (In apparent astonishment.) "Why?"

Girl. "Because I might not have been heart whole, as I am now."

(Long silence.)

Man. (With sudden enthusiasm.) "I'll tell you, though, I really do look well in evening dress."

Girl. "I haven't a doubt of it, even though I've never seen you wear it."

Man. (After brief meditation.) "Let's go and hear Melba next week, will you? I meant to ask you when I first came in, but we got to reading."

Girl. "I shall be charmed."

Next day, Girl gets a box of chocolates and a dozen American Beauties—in February at that.[Pg 10]

Tell a man he has a dimple and he will say "where?" in pleased surprise, meanwhile putting his finger straight into it. He has studied that dimple in the mirror too many times to be unmindful of its geography.

Let the woman dearest to a man say, tenderly: "You were so handsome to-night, dear—I was proud of you." See his face light up with noble, unselfish joy, because he has given such pleasure to others!

All the married men at evening receptions have gone because they "look so well in evening dress," and because "so few men can wear dress clothes really well." In truth, it does require distinction and grace of bearing, if a man would not be mistaken for a waiter.

Man's conceit is not love of himself but of his fellow-men. The man who is in love with himself need not fear that any woman will ever become a serious rival. Not unfrequently, when a man asks a woman to marry him, he means that he wants her to help him love himself, and if, blinded by her own feeling, she takes him for her captain, her pleasure craft becomes a pirate ship, the colours change[Pg 11] to a black flag with a sinister sign, and her inevitable destiny is the coral reef.

Palmistry does very well for a beginning if a man is inclined to be shy. It leads by gentle and almost imperceptible degrees to that most interesting of all subjects, himself, and to that tactful comment, dearest of all to the masculine heart; "You are not like other men!"

A man will spend an entire evening, utterly oblivious of the lapse of time, while a woman subjects him to careful analysis. But sympathy, rather than sarcasm, must be her guide—if she wants him to come again. A man will make a comrade of the woman who stimulates him to higher achievement, but he will love the one who makes herself a mirror for his conceit.

Men claim that women cannot keep a secret, but it is a common failing. A man will always tell some one person the thing which is told him in confidence. If he is married, he tells his wife. Then the exclusive bit of news is rapidly syndicated, and by gentle degrees, the secret is diffused through the community. This is the most pathetic thing in matrimony[Pg 12]—the regularity with which husbands relate the irregularities of their friends. Very little of the world's woe is caused by silence, however it may be in fiction and the drama.

In return for the generous confidence regarding other people's doings, the married man is made conversant with those things which his wife deems it right and proper for him to know. And he is not unhappy, for it isn't what he doesn't know that troubles a man, but what he knows he doesn't know.

The masculine nature is less capable of concealment than the feminine. Where men are frankly selfish, women are secretly so. Man's vices are few and comprehensive; woman's petty and innumerable. Any man who is not in the penitentiary has at most but three or four, while a woman will hide a dozen under her social mask and defy detection.

Women are said to be fickle, but are they more so than men? A man's ideal is as variable as the wind. What he thinks is his ideal of woman is usually a glorified image of the last girl he happened to admire. The man who has had a decided preference for blondes all his life, finally installs a brown-eyed deity[Pg 13] at his hearthstone. If he has been fond of petite and coquettish damsels, he marries some Diana moulded on large lines and unconcerned as to mice.

A man will ride, row, and swim with one girl and marry another who is afraid of horses, turns pale at the mention of a boat, and who would look forward to an interview with His Satanic Majesty with more ease and confidence than to a dip in the summer sea.

Theoretically, men admire "reasonable women," with the uncommon quality which is called "common sense," but it is the woman of caprice, the sweet, illogical despot of a thousand moods, who is most often and most tenderly loved. Man is by nature a discoverer. It is not beauty which holds him, but rather mystery and charm. To see the one woman through all the changing moods—to discern Portia through Carmen's witchery—is the thing above all others which captivates a man.

Deep in his heart, man cherishes the Dorcas ideal. The old, lingering notions of womanliness are not quite dispelled, but in this, as in[Pg 14] other things, nothing sickens a man of his pet theory like seeing it in operation.

It may be a charming sight to behold a girl stirring cheese in the chafing-dish, wearing an air of deep concern when it "bunnies" at the sides and requires still more skill. It may also be attractive to see white fingers weave wonders with fine linen and delicate silks, with pretty eagerness as to shade and stitch.

But in the after-years, when his divinity, redolent of the kitchen, meets him at the door, with hair dishevelled and fingers bandaged, it is subtly different from the chafing-dish days, and the crisp chops, generously black with charcoal, are not as good as her rarebits used to be. The memory of the silk and fine linen also fades somewhat, in the presence of darning which contains hard lumps and patches which immediately come off.

It has become the fashion to speak of woman as the eager hunter, and man as the timid, reluctant prey. The comic papers may have started it, but modern society certainly lends colour to the pretty theory. It is frequently attributed to Mr. Darwin, but he is at[Pg 15] times unjustly blamed by those who do not read his pleasing works.

The complexities in man's personal equation are caused by variants of three emotions; a mutable fondness for women, according to temperament and opportunity, a more uniform feeling toward money, and the universal, devastating desire—the old, old passion for food.

The first variant is but partially under the control of any particular woman, and the less she concerns herself with the second, the better it is for both, but she who stimulates and satisfies the third variant holds in her hands the golden key of happiness. No woman need envy the Sphinx her wisdom if she has learned the uses of silence and never asks a favour of a hungry man.

A woman makes her chief mistake when she judges a man by herself and attributes to him indirection and complexity of motive. When she wishes to attract a particular man, she goes at it indirectly. She makes friends of "his sisters, his cousins, and his aunts," and assumes an interest in his chum. She ignores him at first and thus arouses his curiosity.[Pg 16] Later, she condescends to smile upon him and he is mildly pleased, because he thinks he has been working for that very smile and has finally won it. In this manner he is lured toward the net.

When a girl systematically and effectively feeds a man, she is leading trumps. He insensibly associates her with his comfort and thus she becomes his necessity. When a man seeks a woman's society it is because he has need of her, not because he thinks she has need of him; and the parlour of the girl who realises it, is the envy of every unattached damsel on the street. If the wise one is an expert with the chafing-dish, she may frequently bag desirable game, while the foolish virgins who have no alcohol in their lamps are hunting eagerly for the trail.

Because she herself works indirectly, she thinks he intends a tender look at another girl for a carom shot, and frequently a far-sighted maiden can see the evidences of a consuming passion for herself in a man's devotion to someone else.

Men are not sufficiently diplomatic to bother with finesse of this kind. Other things being[Pg 17] equal, a man goes to see the girl he wants to see. It does not often occur to her that he may not want to see her, may be interested in someone else, or that he may have forgotten all about her.

There is a common feminine delusion to the effect that men need "encouragement" and there is no term which is more misused. A fool may need "encouragement," but the man who wants a girl will go after her, regardless of obstacles. As for him, if he is fed at her house, even irregularly, he may know that she looks with favour upon his suit.

The parents of both, the neighbours, and even the girl herself, usually know that a man is in love before he finds it out. Sometimes he has to be told. He has approached a stage of acute and immediate peril when he recognises what he calls "a platonic friendship."

Young men believe platonic friendship possible; old men know better—but when one man learns to profit by the experience of another, we may look for mosquitoes at Christmas and holly in June.

There is an exquisite danger attached to[Pg 18] friendships of this kind, and is it not danger, rather than variety, which is "the spice of life?" Relieved of the presence of that social pace-maker, the chaperone, the disciples of Plato are wont to take long walks, and further on, they spend whole days in the country with book and wheel.

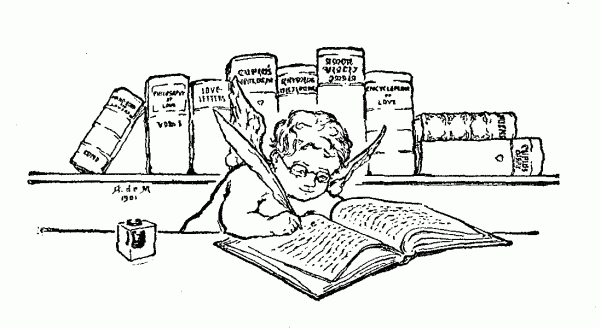

A book is a mysterious bond of union, and by their taste in books do a man and woman unerringly know each other. Two people who unite in admiration of Browning are apt to admire each other, and those who habitually seek Emerson for new courage may easily find the world more kindly if they face it hand in hand.

A latter-day philosopher has remarked upon the subtle sympathy produced by marked passages. "The method is so easy and so unsuspect. You have only to put faint pencil marks against the tenderest passages in your favourite new poet, and lend the volume to Her, and She has only to leave here and there the dropped violet of a timid, confirmatory initial, for you to know your fate."

A man never has a platonic friendship with a woman it is impossible for him to love.[Pg 19] Cupid is the high-priest at these rites of reading aloud and discussing everything under the sun. The two become so closely bound that one arrow strikes both, and often the happiest marriages are those whose love has so begun, for when the Great Passion dies, as it sometimes does, sympathy and mutual understanding may yield a generous measure of content.

The present happy era of fiction closes a story abruptly at the altar or else begins it immediately after the ceremony. Thence the enthralled reader is conducted through rapture, doubt, misunderstanding, indifference, complications, recrimination, and estrangement to the logical end in cynicism and the divorce court.

In the books which women write, the hero of the story shoulders the blame, and often has to bear his creator's vituperation in addition to his other troubles. When a man essays this theme in fiction, he shows clearly that it is the woman's fault. When the situation is presented outside of books, the happily married critics distribute condemnation in the same way, it being customary for each partner in a happy marriage to claim the entire credit for the mutual content.[Pg 20]

Over the afternoon tea cups it has been decided with unusual and refreshing accord, that "it is pursuit and not possession with a man." True—but is it less true with women?

When Her Ladyship finally acquires the sealskin coat on which she has long set her heart, does she continue to scan the advertisements? Does she still coddle him who hath all power as to sealskin coats, with tempting dishes and unusual smiles? Not unless she wants something else.

Still, it is woman's tendency to make the best of what she has, and man's to reach out for what he has not. Man spends his life in the effort to realise the ideals which, like will-o'-the-wisps, hover just beyond him. Woman, on the contrary, brings into her life what grace she may, by idealising her reals.

In her secret heart, woman holds her unchanging ideal of her own possible perfection. Sometimes a man suspects this, and loves her all the more for the sweet guardian angel which is thus enthroned. Other men, less fine, consider an ideal a sort of disease—and they are usually a certain specific.

But, after all, men are as women make them.[Pg 21] Cleopatra and Helen of Troy swayed empires and rocked thrones. There is no woman who does not hold within her little hands some man's achievement, some man's future, and his belief in woman and God.

She may fire him with high ambition, exalt him with noble striving, or make him a coward and a thief. She may show him the way to the gold of the world, or blind him with tinsel which he may not keep. It is she who leads him to the door of glory and so thrills him with majestic purpose, that nothing this side Heaven seems beyond his eager reach.

Upon his heart she may write ecstasy or black despair. Through the long night she may ever beckon, whispering courage, and by her magic making victory of defeat. It is for her to say whether his face shall be world-scarred and weary, hiding tragedy behind its piteous lines; whether there shall be light or darkness in his soul. He cannot escape those soft, compelling fingers; she is the arbiter of his destiny—for like clay in the potter's hands, she moulds him as she will.[Pg 23][Pg 22]

In order to be happy, a woman needs only a good digestion, a satisfactory complexion, and a lover. The first requirement being met, the second is not difficult to obtain, and the third follows as a matter of course.

He was a wise philosopher who first considered crime as disease, for women are naturally sweet-tempered and charming. The shrew and the scold are to be reformed only by a physician, and as for nagging, is it not allopathic scolding in homeopathic doses?

A well woman is usually a happy one, and incidentally, those around her share her content. The irritation produced by fifteen minutes of nagging speaks volumes for the personal influence which might be directed the other way, and the desired result more easily obtained.

The sun around which woman revolves is Love. Her whole life is spent in search of it,[Pg 26] consciously or unconsciously. Incidental diversions in the way of "career" and "independence" are usually caused by domestic unhappiness, or, in the case of spinsters, the fear of it.

If all men were lovers, there would be no "new woman" movement, no sociological studies of "Woman in Business," no ponderous analyses of "The Industrial Condition of Women" in weighty journals. Still more than a man, a woman needs a home, though it be but the tiniest room.

Even the self-reliant woman of affairs who battles bravely by day in the commercial arena has her little nook, made dainty by feminine touches, to which she gladly creeps at night. Would it not be sweeter if it were shared by one who would always love her? As truly as she needs her bread and meat, woman needs love, and, did he but know it, man needs it too, though in lesser degree.

Lacking the daily expression of it which is the sweet unction of her hungry soul, she seeks solace in an ideal world of her own making. It is because the verity jars upon her vision that she takes a melancholy view of life.[Pg 27]

One of woman's keenest pleasures is sorrow. Her tears are not all pain. She goes to the theatre, not to laugh, but to weep. The clever playwright who closes his last scene with a bitter parting is sure of a large clientage, composed almost wholly of women. Sad books are written by men, with an eye to women readers, and women dearly love to wear the willow in print.

Women are unconscious queens of tragedy. Each one, in thought, plays to a sympathetic but invisible audience. She lifts her daily living to a plane of art, finding in fiction, music, pictures, and the stage continual reminders of her own experience.

Does her husband, distraught with business cares, leave her hurriedly and without the customary morning kiss? Woman, on her way to market, rapidly reviews similar instances in fiction, in which this first forgetting proved to be "the little rift within the lute."

The pictures of distracted ladies, wild as to hair and vision, are sold in photogravure by countless thousands—to women. An attraction on the boards which is rumoured to be "so sad," leads woman to economise in the[Pg 28] matter of roasts and desserts that she may go and enjoy an afternoon of misery. Girls suffer all their lives long from being taken to mirthful plays, or to vaudeville, which is unmixed delight to a man and intolerably cheerful to a woman.

Woman and Death are close friends in art. Opera is her greatest joy, because a great many people are slaughtered in the course of a single performance, and somebody usually goes raving mad for love. When Melba sings the mad scene from Lucia, and that beautiful voice descends by lingering half-notes from madness and nameless longing to love and prayer, the women in the house sob in sheer delight and clutch the hands of their companions in an ecstasy of pain.

In proportion as women enjoy sorrow, men shrink from it. A man cannot bear to be continually reminded of the woman he has loved and lost, while woman's dearest keepsakes are old love letters and the shoes of a little child. If the lover or the child is dead, the treasures are never to be duplicated or replaced, but if the pristine owner of the shoes has grown to stalwart manhood and the[Pg 29] writer of the love letters is a tender and devoted husband, the sorrowful interest is merely mitigated. It is not by any means lost.

Just why it should be considered sad to marry one's lover and for a child to grow up, can never be understood by men. There are many things in the "eternal womanly" which men understand about as well as a kitten does the binomial theorem, but some mysteries become simple enough when the leading fact is grasped—that woman's song of life is written in a minor key and that she actually enjoys the semblance of sorrow. Still, the average woman wishes to be idealised and strongly objects to being understood.

Woman's tears mean no more than the sparks from an overcharged dynamo; they are simply emotional relief. Married men gradually come to realise it, and this is why a suspicion of tears in his sweetheart's eyes means infinitely more to a lover than a fit of hysterics does to a husband.

We are wont to speak of woman's tenderness, but there is no tenderness like that of a man for the woman he loves when she is tired[Pg 30] or troubled, and the man who has learned simply to love a woman at crucial moments, and to postpone the inevitable idiotic questioning till a more auspicious time, has in his hands the talisman of domestic felicity.

If by any chance the lachrymal glands were to be dried up, woman's life would lose a goodly share of its charm. There is nothing to cry on which compares with a man's shoulder; almost any man will do at a critical moment; but the clavicle of a lover is by far the most desirable. If the flood is copious and a collar or an immaculate shirt-front can be spoiled, the scene acquires new and distinct value. A pillow does very well, lacking the shoulder, for many of the most attractive women in fiction habitually cry into pillows—because they have no lover, or because the brute dislikes tears.

When grief strikes deep, a woman's eyes are dry. Her soul shudders and there is a hand upon her heart whose icy fingers clutch at the inward fibre in a very real physical pain. There are no tears for times like these; the inner depths, bare and quivering, are healed by no such balm as this.[Pg 31]

A sudden blow leaves a woman as cold as a marble statue and absolutely dumb as to the thing which lies upon her heart. When the tears begin to flow, it means that resignation and content will surely come. On the contrary, when once or twice in a lifetime a man is moved to tears, there is nothing so terrible and so hopeless as his sobbing grief.

Married and unmarried women waste a great deal of time in feeling sorry for each other. It never occurs to a married woman that a spinster may not care to take the troublous step. An ideal lover in one's heart is less strain upon the imagination than the transfiguration of a man who goes around in his shirt-sleeves and dispenses with his collar at ninety degrees Fahrenheit.

If fiction dealt pleasantly with men who are unmindful of small courtesies, the unknown country beyond the altar would lose some of its fear. If the way of an engaged girl lies past a barber shop,—which very seldom has a curtain, by the way,—and she happens to think that she may some day behold her beloved in the dangerous act of shaving himself, it immediately hardens her heart. One[Pg 32] glimpse of one face covered with lather will postpone one wedding-day five weeks. Many a lover has attributed to caprice or coquetry the fault which lies at the door of the "tonsorial parlour."

A woman may be a mystery to a man and to herself, but never to another woman. There is no concealment which is effectual when other feminine eyes are fixed upon one's small and harmless schemes. A glance at a girl's dressing-table is sufficient for the intimate friend—she does not need to ask questions; and indeed, there are few situations in life in which the necessity for direct questions is not a confession of individual weakness.

If fourteen different kinds of creams and emollients are within easy reach, the girl has an admirer who is fond of out-door sports and has not yet declared himself. If the curling iron is kept hot, it is because he has looked approval when her hair was waved. If there is a box of rouge but half concealed, the girl thinks the man is a fatuous idiot and hourly expects a proposal.

If the various drugs are in the dental line, the man is a cheerful soul with a tendency to[Pg 33] be humorous. If she is particular as to small details of scolding locks and eyebrows, he probably wears glasses. If she devotes unusual attention to her nails, the affair has progressed to that interesting stage where he may hold her hand for a few minutes at a time.

If she selects her handkerchief with extreme care,—one with an initial and a faint odour of violet—she expects to give it to him to carry and to forget to ask for it. If he makes an extra call in order to return it, it indicates a lesser degree of interest than if he says nothing about it. The forgotten handkerchief is an important straw with a girl when love's capricious wind blows her way.

It is not entirely without reason that womankind in general blames "the other woman" for defection of any kind. Short-sighted woman thinks it a mighty tribute to her own charm to secure the passing interest of another's rightful property. It does not seem to occur to her that someone else will lure him away from her with even more ease. Each successive luring makes defection simpler for a man. Practice tends towards[Pg 34] perfection in most things; perhaps it is the single exception, love, which proves the rule.

Three delusions among women are widespread and painful. Marriage is currently supposed to reform a man, a rejected lover is heartbroken for life, and, if "the other woman" were only out of the way, he would come back. Love sometimes reforms a man, but marriage does not. The rejected lover suffers for a brief period,—feminine philosophers variously estimate it, but a week is a generous average,—and he who will not come in spite of "the other woman" is not worth having at all.

Emerson says: "The things which are really for thee gravitate to thee." One is tempted to add the World's Congress motto—"Not things, but men."

There is no virtue in women which men cultivate so assiduously as forgiveness. They make one think that it is very pretty and charming to forgive. It is not hygienic, however, for the woman who forgives easily has a great deal of it to do. When pardon is to be had for the asking, there are frequent causes for its giving. This, of course, applies to the interesting period before marriage.[Pg 35]

Post-nuptial sins are atoned for with gifts; not more than once in a whole marriage with the simple, manly words, "Forgive me, dear, I was wrong." It injures a man's conceit vitally to admit he has made a mistake. This is gracious and knightly in the lover, but a married man, the head of a family, must be careful to maintain his position.

Cases of reformation by marriage are few and far between, and men more often die of wounded conceit than broken hearts. "Men have died and worms have eaten them, but not for love," save on the stage and in the stories women cry over.

"The other woman" is the chief bugbear of life. On desert islands and in a very few delightful books, her baneful presence is not. The girl a man loves with all his heart can see a long line of ghostly ancestors, and requires no opera-glass to discern through the mists of the future a procession of possible posterity. It is for this reason that men's ears are tried with the eternal, unchanging: "Am I the only woman you ever loved?" and "Will you always love me?"

The woman who finally acquires legal[Pg 36] possession of a man is haunted by the shadowy predecessors. If he is unwary enough to let her know another girl has refused him, she develops a violent hatred for this inoffensive maiden. Is it because the cruel creature has given pain to her lord? His gods are not her gods—if he has adored another woman.

These two are mutually "other women," and the second one has the best of it, for there is no thorn in feminine flesh like the rejected lover who finds consolation elsewhere. It may be exceedingly pleasant to be a man's first love, but she is wise beyond books who chooses to be his last, and it is foolish to spend mental effort upon old flames, rather than in watching for new ones, for Cæsar himself is not more utterly dead than a man's dead love.

Women are commonly supposed to worry about their age, but Father Time is a trouble to men also. The girl of twenty thinks it absurd for women to be concerned about the matter, but the hour eventually comes when she regards the subject with reverence akin to awe. There is only one terror in it—the dreadful nines.[Pg 37]

"Twenty-nine!" Might she not as well be thirty? There is little choice between Scylla and Charybdis. Twenty-nine is the hour of reckoning for every woman, married, engaged, or unattached.

The married woman felicitates herself greatly, unless a tall daughter of nine or ten walks abroad at her side. The engaged girl is safe—she rejoices in the last hours of her lingering girlhood and hems table linen with more resignation. The unattached girl has a strange interest in creams and hair tonics, and usually betakes herself to the cloister of the university for special courses, since azure hosiery does not detract from woman's charm in the eyes of the faculty.

Men do not often know their ages accurately till after thirty. The gladsome heyday of youth takes no note of the annual milestones. But after thirty, ah me! "Yes," a man will say sometimes, "I am thirty-one, but the fellows tell me I don't look a day over twenty-nine." Scylla and Charybdis again!

Still, age is not a matter of birthdays, but of the heart. Some women are mature cynics at twenty, while a grey-haired matron[Pg 38] of fifty seems to have found the secret of perennial youth. There is little to choose, as regards beauty and charm, between the young, unformed girl, whose soft eyes look with longing into the unyielding future which gives her no hint of its purposes, and the mature woman, well-groomed, self-reliant to her finger-tips, who has drunk deeply of life's cup and found it sweet. A woman is never old until the little finger of her glove is allowed to project beyond the finger itself and she orders her new photographs from an old plate in preference to sitting again.

In all the seven ages of man, there is someone whom she may attract. If she is twenty-five, the boy who has just attained long trousers will not buy her striped sticks of peppermint and ask shyly if he may carry her books. She is not apt to wear fraternity pins and decorate her rooms in college colours, unless her lover still holds his alma mater in fond remembrance. But there are others, always the others—and is it less sweet to inspire the love which lasts than the tender verses of a Sophomore? Her field of action is not sensibly limited, for at twenty[Pg 39] men love woman, at thirty a woman, and at forty, women.

Woman has three weapons—flattery, food, and flirtation, and only the last of these is ever denied her by Time. With the first she appeals to man's conceit, with the second to his heart, which is suspected to lie at the end of the œsophagus, rather than over among lungs and ribs, and with the third to his natural rivalry of his fellows. But the pleasures of the chase grow beautifully less when age brings rheumatism and kindred ills.

Besides, may she not always be a chaperone? When a political orator refers effectively to "the cancer which is eating at the heart of the body politic," someway, it always makes a girl think of a chaperone. She goes, ostensibly, to lend a decorous air to whatever proceedings may be in view. She is to keep the man from making love to the girl. Whispers and tender hand clasps are occasionally possible, however, for, tell it not in Gath! the chaperone was once young herself and at times looks the other way.[Pg 40]

That is, unless she is the girl's mother. Trust a parent for keeping two eyes and a pair of glasses on a girl! Trust the non-matchmaking mother for four new eyes under her back hair and a double row of ears arranged laterally along her anxious spine! And yet, if the estimable lady had not been married herself, it is altogether likely that the girl would never have thought of it.

The reason usually given for chaperonage is that it gives the girl a chance to become acquainted with the man. Of course, in the presence of a chaperone, a man says and does exactly the same things he would if he were alone with the maiden of his choice. He does not mind making love to a girl in her mother's presence. He does not even care to be alone with her when he proposes to her. He would like to have some chaperone read his letters—he always writes with this intention. At any time during the latter part of the month it fills him with delight to see the chaperone order a lobster after they have all had oysters.

Nonsense! Why do not the leaders of society say, frankly: "This chaperone business[Pg 41] is just a little game. Our husbands are either at the club or soundly asleep at home. It is not nice to go around alone, and it is pathetic to go in pairs, with no man. We will go with our daughters and their young friends, for they have cavaliers enough and to spare. Let us get out and see the world, lest we die of ennui and neglect!" It is the chaperone who really goes with the young man. She takes the girl along to escape gossip.

It is strange, when it is woman's avowed object to make man happy, that she insists upon doing it in her own way, rather than in his. He likes the rich, warm colours; the deep reds and dark greens. Behold his house!

Renaissance curtains obscure the landscape with delicate tracery, and he realises what it might mean to wear a veil. Soft tones of rose and Nile green appear in his drawing-room. Chippendale chairs, upon which he fears to sit, invite the jaded soul to whatever repose it can get. See the sofa cushions, which he has learned by bitter experience never to touch! Does he rouse a quiescent Nemesis by laying his weary head upon that elaborate embroidery? Not unless his memory is poor.[Pg 42]

Take careful note of the bric-à-brac upon his library table. See the few square inches of blotting paper on a cylinder which he can roll over his letter—the three stamps stuck together more closely than brothers, generously set aside for his use. Does he find comfort here? Not very much of it.

See the dainty dinner which is set before the hungry man. A cup of rarest china holds four ounces of clear broth. A stick of bread or two crackers are allotted to him. Then he may have two croquettes, or one small chop, when his soul is athirst for rare roast beef and steak an inch thick. Then a nice salad, made of three lettuce leaves and a suspicion of oil, another cracker and a cubic inch of cheese, an ounce of coffee in a miniature cup, and behold, the man is fed!

Why should he go to his club, call loudly for flesh-pots, sink into a chair he is not afraid of breaking, and forget his trouble in the evening paper, while his wife is at home, alone, or having a Roman holiday as a chaperone?

It is a simple thing to acquire a lover, but it is a fine art to keep him. Clubs were origin[Pg 43]ally intended for the homeless, as distinguished from the unmarried. The rare woman who rests and soothes a man when he is tired has no rival in the club. Misunderstanding, sorrowful, yearning for what she has lost, woman contemplates the wreck of her girlish dream.

There are three things man is destined never to solve—perpetual motion, the square of the circle, and the heart of a woman. Yet he may go a little way into the labyrinth with the thread of love, which his Ariadne will gladly give him at the door.

The dim chambers are fragrant with precious things, for through the winding passages Memory has strewn rue and lavender, love and longing; sweet spikenard and instinctive belief. Some day, when the heart aches, she will brew content from these.

There are barriers which he may not pass, secret treasures that he may not see, dreams that he may not guess. There are dark corners where there has been torture, of which he will never know. There are shadows and ghostly shapes which Penelope has hidden with the fairest fabrics of her loom. There[Pg 44] are doors, tightly locked, which he has no key to open; rooms which have contained costly vessels, empty and deep with dust.

There is no other step than his, for he walks there alone; sometimes to the music of dead days and sometimes to the laughter of a little child. The petals of crushed roses rustle at his feet—his roses—in the inmost places of her heart. And beyond, of spotless marble, with the infinite calm of mountains and perpetual snow, is something which he seldom comprehends—her love of her own whiteness.

It is a wondrous thing. For it is so small he could hold it in the hollow of his hand, yet it is great enough to shelter him forever. All the world may not break it if his love is steadfast and unchanging, and loving him, it becomes deep enough to love and pity all the world.

It is a tender thing. So often is it wounded that it cannot see another suffer, and its own pain is easier far to bear. It makes a shield of its very tenderness, gladly receiving the stabs that were meant for him, forgiving always, and forgetting when it may.[Pg 45]

Yet, after all, it is a simple thing. For in times of deepest doubt and trouble, it requires for its solace only the tender look, the whispered word which brings new courage, and the old-time grace of the lover's way.[Pg 47][Pg 46]

A modern novelist has greatly lamented because the prevailing theme of fiction is love. Every story is a love story, every romance finds its inspiration in the heart, and even the musty tomes of history are beset by the little blind god.

One or two men have dared to write books from which women have been excluded as rigorously as from the Chinese stage, but the world of readers has not loudly clamoured for more of the same sort. A story of adventure loses none of its interest if there is some fair damsel to be rescued from various thrilling situations.

The realists contend that a single isolated fact should not be dwelt upon to the exclusion of all other interests, that love plays but a small part in the life of the average man or woman, and that it is unreasonable to expand it to the uttermost limits of art.[Pg 50]

Strangely enough, the realists are all men. If a woman ventures to write a book which may fitly be classed under the head of realism, the critics charitably unite upon insanity as the cause of it and lament the lost womanliness of a decadent generation.

If realism were actually real, we should have no time for books and pictures. Our days and nights would be spent in reclaiming the people in the slums. There would be a visible increase in the church fair—where we spend more than we can afford for things we do not want, in order to please people whom we do not like, and to help heathen who are happier than we are.

The love of money is said to be the root of all evil, but love itself is the root of all good, for it is the very foundation of the social structure. The universal race for the elusive shilling, which is commonly considered selfish, is based upon love.

Money will buy fine houses, but who would wish to live in a mansion alone! Fast horses, yachts, private cars, and the feasts of Lucullus, are not to be enjoyed in solitude; they must be shared. Buying jewels and costly raiment[Pg 51] is the purest philanthropy, for it gives pleasure to others. Sapphires and real lace depreciate rapidly in the cloister or the desert.

The envy which luxury sometimes creates is also altruistic in character, for in its last analysis, it is the wish to give pleasure to others, in the same degree, as the envied fortunately may. Nothing is happiness which is not shared by at least one other, and nothing is truly sorrow unless it is borne absolutely alone.

Love! The delight and the torment of the world! The despair of philosophers and sages, the rapture of poets, the confusion of cynics, and the warrior's defeat!

Love! The bread and the wine of life, the hunger and the thirst, the hurt and the healing, the only wound which is cured by another! The guest who comes like a thief in the night! The eternal question which is its own answer, the thing which has no beginning and no end!

The very blindness of it is divine, for it sees no imperfections, takes no reck of faults, and concerns itself only with the hidden beauty of the soul.[Pg 52]

It is unselfishness—yet it tolerates no rival and demands all for itself. It is belief—and yet it doubts. It is hope and it is also misgiving. It is trust and distrust, the strongest temptation and the power to withstand it; woman's need and man's dream. It is his enemy and his best friend, her weakness and her strength; the roses and the thorns.

Woman's love affairs begin in her infancy, with some childish play at sweethearts, and a cavalier in dresses for her hero. It may be a matter of affinity in later years, or, as the more prosaic Buckle suggests, dependent upon the price of corn, but at first it is certainly a question of propinquity.

Through the kindergarten and the multiplication table, the pretty game goes on. Before she is thirteen, she decides to marry, and selects an awkward boy a little older for the happy man. She cherishes him in her secret heart, and it does not matter in the least if she does not know him well enough to speak to him, for the good fairies who preside over earthly destinies will undoubtedly lead The Prince to become formally acquainted at the proper time.[Pg 53]

Later, the self-conscious period approaches and Mademoiselle becomes solicitous as to ribbons and personal adornment. She pleads earnestly for long gowns, and the first one is never satisfying unless it drags. If she can do her hair in a twist "just like mamma's," and see the adored one pass the house, while she sits at the window with sewing or book, she feels actually "grown up."

When she begins to read novels, her schoolmates, for the time being, are cast aside, because none of them are in the least like the lovers who stalk through the highly-coloured pages of the books she likes best. The hero is usually "tall and dark, with a melancholy cast of countenance," and there are fascinating hints of some secret sorrow. The watchful maternal parent is apt to confiscate these interesting volumes, but there are always school desks and safe places in the neighbourhood of pillows, and a candle does not throw its beams too far.

The books in which the love scenes are most violent possess unfading charm. A hero who says "darling" every time he opens his finely-chiselled mouth is very near[Pg 54] perfection. That fondness lasts well into the after-years, for "darling" is, above all others, the favourite term of endearment with a woman.

Were it not for the stern parents and wholesome laws as to age, girls might more often marry their first loves. It is difficult to conjecture what the state of civilisation might be, if it were common for people to marry their first loves, regardless of "age, colour, or previous condition of servitude."

Age and colour are all-important factors with Mademoiselle. She could not possibly love a boy three weeks younger than herself, and if her eyes are blue and her hair light, no blondes need apply.

There is a curious delusion, fostered by phrenologists and other amiable students of "temperament," to the effect that a brunette must infallibly fall in love with a blonde and vice versa. What dire misfortune may result if this rule is not followed can be only surmised, for the phrenologists do not know. Still, the majority of men are dark and it is said they do not marry as readily as of yore—is this the secret of the widespread havoc made by peroxide of hydrogen?[Pg 55]

The lurid fiction fever soon runs its course with Mademoiselle, if she is let alone, and she turns her attention once more to her schoolmates. She has at least a dozen serious attacks before she is twenty, and at that ripe age, is often a little blasé.

But the day soon comes when the pretty play is over and the soft eyes widen with fear. She passes the dividing line between childhood and womanhood when she first realises that her pastime and her dream have forged chains around her inmost soul. This, then, is what life holds for her; it is ecstasy or torture, and for this very thing she was made.

Some man exists whom she will follow to the end of the world, right royally if she may, but on her knees if she must. The burning sands of the desert will be as soft grass if he walks beside her, his voice will make her forget her thirst, and his touch upon her arm will change her weariness into peace.

When he beckons she must answer. When he says "come," she must not stay. She must be all things to him—friend, comrade, sweetheart, wife. When the infinite mean[Pg 56]ing of her dream slowly dawns upon her, is it strange that she trembles and grows pale?

Soon or late it comes to all. Sometimes there is terror at the sudden meeting and Love often comes in the guise of a friend. But always, it brings joy which is sorrow, and pain which is happiness—gladness which is never content.

A woman wants a man to love her in the way she loves him; a man wants a woman to love him in the way he loves her, and because the thing is impossible, neither is satisfied.

Man's emotion is far stronger than woman's. His feeling, when it is deep, is a force which a woman may but dimly understand. The strongest passion of a man's life is his love for his sweetheart; woman's greatest love is lavished upon her child.

"One is the lover and one is the loved." Sometimes the positions are reversed, to the misery of all concerned, but normally, man is the lover. He wins love by pleading for it, and there is no way by which a woman may more surely lose it, for while woman's pity is closely akin to Love, man's pity is a poor relation who wears Love's cast-off clothes.[Pg 57]

There are two other ways in which a woman loses her lover. One is by marrying him and the other by retaining him as her friend. If she can keep him as her friend, she never believes in his love, and husbands and lovers are often two very different possessions.

A man's heart is an office desk, wherein tender episodes are pigeon-holed for future reference. If he is too busy to look them over, they are carried off later in Father Time's junk-wagon, like other and more profane history.

All the isolated loves of a woman's life are woven into a single continuous fabric. Love itself is the thing she needs and the man who offers it seldom matters much. Man loves and worships woman, but woman loves love. Were it not so, there would be no actor's photograph upon the matinée girl's dressing-table, and no bit of tender verse would be fastened to her cushion with a hat pin, while she herself was fancy free.

All her life long she confuses the gift with the giver, and loving with the pride of being loved, because her love is responsive rather than original.[Pg 58]

She demands that the lover's devotion shall continue after marriage; that every look shall be tender and every word adoring. Failing this, she knows that love is dead. She is inevitably disappointed in marriage, because she is no longer his fear, intoxication, and pain, but rather his comrade and friend. The vibrant strings, struck from silence and dreams to a sounding chord, are trembling still—whispering lingering music to him who has forgotten the harp.

When a woman once tells a man she loves him, he regards it as some chemical process which has taken place in her heart and he never considers the possibility of change. He is little concerned as to its expression, for he knows it is there. On the contrary, it is only by expression that a woman ever feels certain of a man's love.

Doubt is the essential and constant quality of her nature, when once she loves. She continually demands new proof and new devotion, consoling herself sometimes with the thought that three days ago he said he loved her and there has been no discord since.

As for him, if his comfort is assured, he[Pg 59] never thinks to question her, for men are as blind as Love. If she seems glad to see him and is not distinctly unpleasant, she may even be a little preoccupied without arousing suspicion. A man likes to feel that he is loved and a woman likes to be told.

The use of any faculty exhausts it. The ear, deafened by a cannon, is incapable for the moment of hearing the human voice. The eyes, momentarily blinded by the full glare of the sun, miss the delicate shades of violet and sapphire in the smoke from a wood fire. We soon become accustomed to condiments and perfume, and the same law applies to sentiment and emotion.

Thus it seems to women that men love spasmodically—that the lover's devotion is a series of unrelated acts based upon momentary impulse, rather than a steady purpose. They forget that the heart may need more rest than the interval between beats.

If a man and woman who truly loved each other were cast away upon a desert island, he would tire of her long before she wearied of him. The sequence of attraction and repulsion, the ultimate balance of positive and[Pg 60] negative, are familiar electrical phenomena. Is it unreasonable to suppose that the supreme form of attraction is governed by the same law?

Strong attractions frequently begin with strong repulsions, sometimes mutual, but more often on the part of the attracting force. A man seldom develops a violent and inexplicable hatred for a woman and later finds that it has unaccountably changed to love.

Yet a woman often marries a man she has sincerely hated, and the explanation is simple enough, perhaps, for a woman never hates a man unless he is in some sense her master. Love and hate are kindred passions with a woman and the depth of the one is the possible measure of the other.

She is wise who fully understands her weapon of coquetry. She will send her lover from her at the moment his love is strongest, and he will often seek her in vain. She will be parsimonious with her letters and caresses and thus keep her attraction at its height. If he is forever unsatisfied, he will always be her lover, for satiety must precede repulsion.

No woman need fear the effect of absence[Pg 61] upon the man who honestly loves her. The needle of the compass, regardless of intervening seas, points forever toward the north. Pitiful indeed is she who fails to be a magnet and blindly becomes a chain.

The age has brought with it woman's desire for equality, at least in the matter of love. She wishes to be as free to seek a man as he is to seek her—to love him as freely and frankly as he does her. Why should she withhold her lips after her heart has surrendered? Why should she keep the pretence of coyness long after she has been won?

Far beneath the tinsel of our restless age lies the old, old law, and she who scorns it does so at the peril of all she holds most dear. Legislation may at times be disobeyed, but never law, for the breaking brings swift punishment of its own.

Too often a generous-hearted woman makes the mistake of full revelation. She wishes him to understand her every deed, her every thought. Nothing is left to his imagination—the innermost corners of her heart are laid bare. Given the woman and the circumstances, he would infallibly know her action.[Pg 62] This is why the husbands of the "practical," the "methodical," and the "reasonable" women may be tender and devoted, but are never lovers after marriage.

If Alexander had been a woman, he would not have sighed for more worlds to conquer—woman asks but one. If his world had been a clever woman he would have had no time for alien planets, because a man will never lose his interest in a woman while his conquest is incomplete.

The woman who is most tenderly loved and whose husband is still her lover, carefully conceals from him the fact that she is fully won. There is always something he has yet to gain.

After ten years of marriage, if the old relation remains the same, it is because she is a Carmen at heart. She is alluring, tempting, cajoling and scorning in the same breath; at once tender and commanding, inspiring both love and fear, baffling and eluding even while she is leading him on.

She gives him veiled hints of her real personality, but he never penetrates her mask. Could he see for an instant into the secret[Pg 63] depths of her soul, he would understand that her concealment and her coquetry, her mystery and her charm, are nothing but her love, playing a desperate game against Time and man's nature, for the dear stake of his own.

Dumas draws a fine distinction when he says: "A man may have two passions but never two loves: whoever has loved twice has never loved at all." If this is true, the dividing line is so exceedingly fine that it is beyond woman's understanding, and it may be surmised that even man does not fully realise it until he is old and grey.

Yet somewhere, in every man's heart, is hidden a woman's face. To that inner chamber no other image ever finds its way. The cords of memory which hold it are strong as steel and as tender as the heart-fibre of which they are made.

There is no time in his life when those eyes would not thrill him and those lips make him tremble—no hour when the sound of that voice would not summon him like a trumpet-call.

No loyalty or allegiance is powerful enough to smother it within his own heart, in spite of[Pg 64] the conditions to which he may outwardly conform. Other passions may temporarily hide it even from his own sight, yet in reality it is supreme, from the day of its birth to the door of his grave.

He may be happily married, as the world counts happiness, and She may be dead—but never forgotten. No real love or hate is wrought upon by Lethe. The thousand dreams of her will send his blood in passionate flow and the thousand memories of her whiten his face with pain. Friendship is intermittent and passion forgets, but man's single love is eternal.

Because woman's love is responsive, it never dies. Her love of love is everlasting. Some threads in the fabric she has woven are like shining silver; others are sombre, broken, and stained with tears. When a man has once taught a woman to believe his love is true, she is already, though unconsciously, won.

All the beauty in woman's life is forever associated with her love. Violets bring the memory of dead days, when the boy-lover brought them to her in fragrant heaps. Some[Pg 65] women say man's love is selfish, but there is no one among them who has ever been loved by a boy.

Broken, hesitant chords set some lost song to singing in her heart. The break in her lover's voice is like another, long ago. Summer days and summer fields, silver streams, and clouds of apple blossoms set against the turquoise sky, bring back the Mays of childhood and all the childish dreams.

This is another thing a man cannot understand—that every little tenderness of his wakes the memory of all past tenderness, and for that very reason is often doubly sweet. This is the explanation of sudden sadness, of the swift succession of moods, and of lips, shut on sobs, that sometimes quiver beneath his own.

Woman keeps alive the old ideals. Were it not for her eager efforts, chivalry would have died long ago. King Arthur's Court is said to be a myth, and Lancelot and Guenevere were only dreams, but the knightly spirit still lives in man's love for woman.

The Lady of the Court was wont to send her knight into danger at her sweet, capricious[Pg 66] will. Her glove upon his helmet, her scarf upon his arm, her colours on his shield—were they worth the risk of horse and spear? Yet the little that she gave him, made him invincible in the field.

To-day there is a subtle change. She is loved as dearly as was Guenevere, but she gives him neither scarf nor glove. Her love in his heart is truly his shield and his colours are the white of her soul.

He needs no gage but her belief, and having that, it is a trust only a coward will betray. The battle is still to the strong, but just as surely her knight comes back with his shield untarnished, his colours unstained, and his heart aglow with love of her who gave him courage.

The centuries have brought new striving, which the Lady of the Court could never know. The daughter of to-day endeavours to be worthy of the knightly worship—to be royal in her heart and queenly in her giving; to be the exquisitely womanly woman he sees behind her faulty clay, so that if the veil of illusion he has woven around her should ever fall away, the reality might be even fairer than his dream.[Pg 67]

Through the sombre pages of history the knights and ladies move, as though woven in the magic web of the Lady of Shalott. Tournament and shield and spear, the Round Table and Camelot, have taken on the mystery of fables and dreams.

Yet, by the grace of magic, the sweet old story lives to-day, unforgotten, because of its single motive. Elaine still dies for love of Lancelot, Isolde urges Tristram to new proofs of devotion, and Guenevere, the beautiful, still shares King Arthur's throne. For chivalry is not dead—- it only sleeps—and the nobleness and valour of that far-off time are ever at the service of her who has found her knight.[Pg 69][Pg 68]

Civilisation is so acutely developed at present that the old meaning of courtship is completely lost. None of the phenomena which precede a proposal would be deemed singular or out of place in a platonic friendship. This state of affairs gives a man every advantage and all possible liberty of choice.

Our grandparents are scandalised at modern methods. "Girls never did so," in the distant years when those dear people were young. If a young man called on grandmother once a week, and she approved of him and his prospects, she began on her household linen, without waiting for the momentous question.

Judging by the fiction of the period and by the delightful tales of old New England, which read like fairy stories to this generation, the courtships of those days were too leisurely[Pg 72] to be very interesting. Ten-year engagements did not seem to be unusual, and it was not considered a social mistake if a man suddenly disappeared for four or five years, without the formality of mentioning his destination to the young woman who expected to marry him.

We have all read of the faithful maidens who kept on weaving stores of fine linen and making regular pilgrimages for the letter which did not come. Years afterward, when the man finally appeared, it was all right, and the wedding went on just the same, even though in the meantime the recreant knight had married and been bereaved.

Two or three homeless children were sometimes brought cheerfully into the story, and assisted materially in the continuation of the interrupted courtship. The tears which the modern spinster sheds over such a tale are not at the pathos of the situation, but because it is possible, even in fiction, for a woman to be so destitute of spirit.

"In dem days," as Uncle Remus would say, any attention whatever meant business. Small courtesies which are without signifi[Pg 73]cance now were fraught with momentous import then. In this year of grace, among all races except our own, there are ways in which a man may definitely commit himself without saying a word.

A flower or a serenade is almost equivalent to a proposal in sunny Spain. A "walking-out" period of six months is much in vogue in other parts of Europe, but the daughter of the Anglo-Saxon has no such guide to a man's intentions.

Among certain savage tribes, if a man is in love with a girl and wishes to marry her, he drags her around his tent by the hair or administers a severe beating. It may be surmised that these attentions are not altogether pleasant, but she has the advantage of knowing what the man means.

Flowers are a pretty courtesy and nothing more. The kindly thought which prompts them may be as transient as their bloom. Three or four men serenade girls on summer nights because they love to hear themselves sing. Books, and music, and sweets, which convention decrees are the only proper gifts for the unattached, may be sent to any girl,[Pg 74] without affecting her indifference to furniture advertisements and January sales of linen.

If there is any actual courtship at the present time, the girl does just as much of it as the man. Her dainty remembrances at holiday time have little more meaning than the trifles a man bestows upon her, though the gift latitude accorded her is much wider in scope.

When a girl gives a man furniture, she usually intends to marry him, but often merely succeeds in making things interesting for the girl who does it in spite of her. The newly-married woman attends to the personal belongings of her happy possessor with the celerity which is taught in classes for "First Aid to the Injured."

One by one, the cherished souvenirs of his bachelor days disappear. Pictures painted by rival fair ones go to adorn the servant's room, through gradual retirement backward. Rare china is mysteriously broken. Sofa cushions never "harmonise with the tone of the room," and the covers have to be changed. It takes time, but usually by the first anniversary of a man's marriage, his penates have been nobly[Pg 75] weeded out, and the things he has left are of his wife's choosing, generously purchased with his own money.

Woe to the girl who gives a man a scarf-pin! When the bride returns the initial call, that scarf-pin adds conspicuously to her adornment. The calm appropriation makes the giver grind her teeth—- and the bride knows it.

In the man's presence, the keeper of his heart and conscience will say, sweetly: "Oh, my dear, such a dreadful thing has happened! That exquisitely embroidered scarf you made for Tom's chiffonier is utterly ruined! The colours ran the first time it was washed. You have no idea how I feel about it—it was such a beautiful thing!"

The wretched donor of the scarf attempts consolation by saying that it doesn't matter. It never was intended for Tom, but as every stitch in it was taken while he was with her, he insisted that he must have it as a souvenir of that happy summer. She adds that it was carefully washed before it was given to him, that she has never known that kind of silk to fade, and that something must have been done to it to make the colours run.[Pg 76]

The short-sighted man at this juncture felicitates himself because the two are getting on so well together. He never realises that a pitched battle has occurred under his very nose, and that the honours are about even.

If Tom possesses a particularly unfortunate flash-light photograph of the girl, the bride joyfully frames it and puts it on the mantel where all may see. If the original of the caricature remonstrates, the happy wife sweetly temporises and insists that it remain, because "Tom is so fond of it," and says, "it looks just like her."

Devious indeed are the paths of woman. She far excels the "Heathen Chinee" in his famous specialty of "ways that are dark and tricks that are vain."

Courtship is a game that a girl has to play without knowing the trump. The only way she ever succeeds at it is by playing to an imaginary trump of her own, which may be either open, disarming friendliness, or simple indifference.

When a man finds the way to a woman's heart a boulevard, he has taken the wrong road. When his path is easy and his burden[Pg 77] light, it is time for him to doubt. When his progress seems like making a new way to the Klondike, he needs only to keep his courage and go on.

For, after all, it is woman who decides. A clever girl may usually marry any man she sees fit to honour with the responsibility of her bills. The ardent lover counts for considerably less than he is wont to suppose.

There is a good old scheme which the world of lovers has unanimously adopted, in order to find out where they stand. It is so simple as to make one weep, but it is the only one they know. This consists of an intentional absence, judiciously timed.

Suppose a man has been spending three or four evenings a week with the same girl, for a period of two or three months. Flowers, books, and chocolates have occasionally appeared, as well as invitations to the theatre. The man has been fed out of the chafing-dish, and also with accidental cake, for men are as fond of sugar as women, though they are ashamed to admit it.

Suddenly, without warning, the man misses an evening, then another, then another. Two[Pg 78] weeks go by, and still no man. The neighbours and the family begin to ask questions of a personal nature.

It is at this stage that the immature and childish woman will write the man a note, expressing regret for his long absence, and trusting that nothing may interfere with their "pleasant friendship." Sometimes the note brings the man back immediately and sometimes it doesn't. He very seldom condescends to make an explanation. If he does, it is merely a casual allusion to "business." This is the only excuse even a bright man can think of.

This act is technically known among girls as "climbing a tree." When a man does it, he wants a girl to bring a ladder and a lunch and plead with him to come down and be happy, but doing as he wishes is no way to attract a man up a tree.

Men are as impervious to tears and pleadings as a good mackintosh to mist, but at the touch of indifference, they melt like wax. So when her quondam lover attempts metaphorical athletics, the wise girl smiles and withdraws into her shell.

She takes care that he shall not see her[Pg 79] unless he comes to her. She draws the shades the moment the lamps are lighted. If he happens to pass the house in the evening, he may think she is out, or that she has company—it is all the same to her. She arranges various evenings with girl friends and gets books from the library. This is known as "provisioning the citadel for a siege."

It is a contest between pride and pride which occurs in every courtship, and the girl usually wins. True lovers are as certain to return as Bo-Peep's flock or a systematically deported cat. Shame-faced, but surely, the man comes back.

Various laboratory note-books yield the same result. A single entry indicates the general trend of the affair.

Man calls on Girl after five weeks of unexplained absence. She asks no questions, but keeps the conversation impersonal, even after he shows symptoms of wishing to change its character.

Man. (Finally.) "I haven't seen you for an awfully long time."

Girl. "Haven't you? Now that I think of it, it has been some time."[Pg 80]

Man. "How long has it been, I wonder?"

Girl. "I haven't the least idea. Ten days or two weeks, I guess."

Man. (Hastily.) "Oh no, it's been much longer than that. Let's see, it's"—(makes great effort with memory)—"why, it's five weeks! Five weeks and three days! Don't you remember?"

Girl. "I hadn't thought of it. It doesn't seem that long. How time does fly, doesn't it!" (Long silence.)

Man. "I've been awfully busy. I wanted to come over, but I just couldn't."

Girl. "I've been very busy, too." (Voluminous detail of her affairs follows, entirely pleasant in character.)

Man. (Tenderly.) "Were you so busy you didn't miss me?"

Girl. "Why, I can't say I missed you, exactly, but I always thought of you pleasantly."

Man. "Did you think of me often?"

Girl. (Laughing.) "I didn't keep any record of it. Do you want me to cut a notch in the handle of my parasol every time I think of you? If all my friends were so exacting,[Pg 81] I'd have time for nothing else. I'd need a new one every week and the house would be full of shavings. All my fingers would be cut, too."

Man. (Unconsciously showing his hand.) "I thought you'd write me a note."

Girl. (Leading his short suit.) "You could have waited on your front steps till the garbage man took you away, and I wouldn't have written you any note."

Man. (With evident sincerity.) "That's no dream! I could do just that!" (Proposal follows in due course, Man making full and complete confession.)

If he is foolish enough to complicate his game with another girl, he loses much more than he gains, for he lowers the whole affair to the level of a flirtation, and destroys any belief the girl may have had in him. He also forces her to do the same thing, in self-defence. Flirtation is the only game in which it is advisable and popular to trump one's partner's ace.

He who would win a woman must challenge her admiration, prove himself worthy of her regard, appeal to her sympathy—and[Pg 82] then wound her. She is never wholly his until she realises that he has the power to make her miserable as well as to make her happy, and that love is an infinite capacity for suffering.

A man who does it consciously is apt to overdo it, out of sheer enthusiasm, and if a girl suspects that it is done intentionally, the hurt loses its sting and changes her love to bitterness. A succession of attempts is also useless, for a man never hurts a woman twice in exactly the same way. When he has run the range of possible stabs, she is out of his reach—unless she is his wife.

The intentional absence scheme is too transparent to succeed, and temporary devotion to another girl is definite damage to his cause, for it indicates fickleness and instability. There is only one way by which a man may discover his true position without asking any questions, and that is—a state secret. Now and then a man strikes it by accident, but nobody ever tells—even brothers or platonic friends.

Some men select a wife as they would a horse, paying due attention to appearance, gait,[Pg 83] disposition, age, teeth, and grooming. High spirits and a little wildness are rather desirable than otherwise, if both are young. Men who have had many horses or many wives and have grown old with both, have a slight inclination toward sedate ways and domestic traits.

Modern society makes it fully as easy to choose the one as the other. In communities where the chaperone idea is at its prosperous zenith, a man may see a girl under nearly all circumstances. The men who conduct the "Woman's Column" in many pleasing journals are still writing of the effect it has on a man to catch a girl in curl papers of a morning, though curl papers have been obsolete for many and many a moon.

Cycling, golf, and kindred out-door amusements have been the death of careless morning attire. Uncorseted woman is unhappy woman, and the girl of whom the versatile journalist writes died long ago. Perhaps it is because a newspaper man can write anything at four minutes' notice and do it well, that the press fairly reeks with "advice to women."

The question, propounded in a newspaper column, "What Kind of a Girl Does a Man[Pg 84] Like Best," will bring out a voluminous symposium which adds materially to the gaiety of the nation. It would be only fair to have this sort of thing temporarily reversed—to tell men how to make home happy for their wives and how to keep a woman's love, after it has once been given.

Some clever newspaper woman might win everlasting laurels for herself if she would contribute to this much neglected branch of human knowledge. How is a man to know that a shirt-front which looks like a railroad map diverts one's mind from his instructive remarks? How is he to know that a cane is a nuisance when he fares forth with a girl? It is true that sisters might possibly attempt this, but the modern sister is heavily overworked at present and it is not kind to suggest an addition to her cares.

There is no advice of any sort given to men except on the single subject of choosing a wife. This is to be found only in the books in the Sabbath-School library, or in occasional columns of the limited number of saffron dailies which illuminate the age. Surely, man has been neglected by his kind![Pg 85]

The general masculine attitude indicates widespread belief in the promise, "Ask, and ye shall receive." A man will tell his best friend that he doesn't know whether to marry a certain girl. If she hears of his indecision there is trouble ahead, if he finally decides in the affirmative, and it is quite possible that he may not marry her.

After the door of a woman's heart has once swung on its silent hinges, a man thinks he can prop it open with a brick and go away and leave it. A storm is apt to displace the brick, however—and there is a heavy spring on the door. Woe to the masculine finger that is in the way!

A man often hesitates between two young women and asks his friends which he shall marry. Custom has permitted the courtship of both and neither has the right to feel aggrieved, because it is exceedingly bad form for a girl to love a man before he has asked her to.