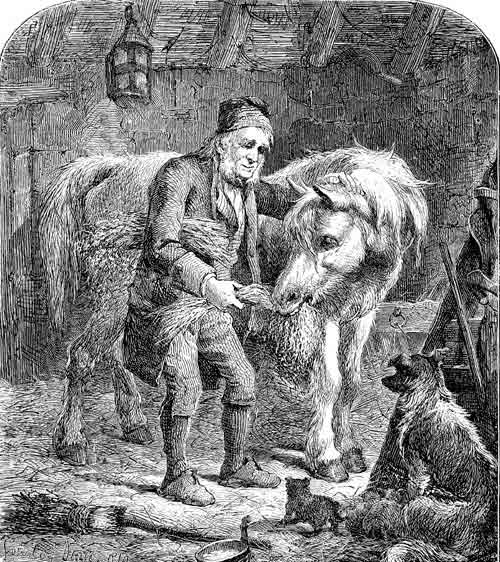

“AULD MARE MAGGIE.”

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Complete Works of Robert Burns:

Containing his Poems, Songs, and Correspondence., by Robert Burns and Allan Cunningham

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Complete Works of Robert Burns: Containing his Poems, Songs, and Correspondence.

With a New Life of the Poet, and Notices, Critical and

Biographical by Allan Cunningham

Author: Robert Burns and Allan Cunningham

Release Date: June 4, 2006 [EBook #18500]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WORKS OF ROBERT BURNS ***

Produced by Marilynda Fraser-Cunliffe, Sankar Viswanathan,

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was made using scans of

public domain works from the University of Michigan Digital

Libraries.)

Transcriber’s Note.

1. The hyphenation and accent of words is not uniform throughout the book. No change has been made in this.

2. The relative indentations of Poems, Epitaphs, and Songs are as printed in the original book.

[On the title-page of the second or Edinburgh edition, were these words: “Poems, chiefly in the Scottish Dialect, by Robert Burns, printed for the Author, and sold by William Creech, 1787.” The motto of the Kilmarnock edition was omitted; a very numerous list of subscribers followed: the volume was printed by the celebrated Smellie.]

My Lords and Gentlemen:

A Scottish Bard, proud of the name, and whose highest ambition is to sing in his country’s service, where shall he so properly look for patronage as to the illustrious names of his native land: those who bear the honours and inherit the virtues of their ancestors? The poetic genius of my country found me, as the prophetic bard Elijah did Elisha—at the plough, and threw her inspiring mantle over me. She bade me sing the loves, the joys, the rural scenes and rural pleasures of my native soil, in my native tongue; I tuned my wild, artless notes as she inspired. She whispered me to come to this ancient metropolis of Caledonia, and lay my songs under your honoured protection: I now obey her dictates.

Though much indebted to your goodness, I do not approach you, my Lords and Gentlemen, in the usual style of dedication, to thank you for past favours: that path is so hackneyed by prostituted learning that honest rusticity is ashamed of it. Nor do I present this address with the venal soul of a servile author, looking for a continuation of those favours: I was bred to the plough, and am independent. I come to claim the common Scottish name with you, my illustrious countrymen; and to tell the world that I glory in the title. I come to congratulate my country that the blood of her ancient heroes still runs uncontaminated, and that from your courage, knowledge, and public[viii] spirit, she may expect protection, wealth, and liberty. In the last place, I come to proffer my warmest wishes to the great fountain of honour, the Monarch of the universe, for your welfare and happiness.

When you go forth to waken the echoes, in the ancient and favourite amusement of your forefathers, may Pleasure ever be of your party: and may social joy await your return! When harassed in courts or camps with the jostlings of bad men and bad measures, may the honest consciousness of injured worth attend your return to your native seats; and may domestic happiness, with a smiling welcome, meet you at your gates! May corruption shrink at your kindling indignant glance; and may tyranny in the ruler, and licentiousness in the people, equally find you an inexorable foe!

I have the honour to be,

With the sincerest gratitude and highest respect,

My Lords and Gentlemen,

Your most devoted humble servant,

ROBERT BURNS.

Edinburgh, April 4, 1787.

I cannot give to my country this edition of one of its favourite poets, without stating that I have deliberately omitted several pieces of verse ascribed to Burns by other editors, who too hastily, and I think on insufficient testimony, admitted them among his works. If I am unable to share in the hesitation expressed by one of them on the authorship of the stanzas on “Pastoral Poetry,” I can as little share in the feelings with which they have intruded into the charmed circle of his poetry such compositions as “Lines on the Ruins of Lincluden College,” “Verses on the Destruction of the Woods of Drumlanrig,” “Verses written on a Marble Slab in the Woods of Aberfeldy,” and those entitled “The Tree of Liberty.” These productions, with the exception of the last, were never seen by any one even in the handwriting of Burns, and are one and all wanting in that original vigour of language and manliness of sentiment which distinguish his poetry. With respect to “The Tree of Liberty” in particular, a subject dear to the heart of the Bard, can any one conversant with his genius imagine that he welcomed its growth or celebrated its fruit with such “capon craws” as these?

There are eleven stanzas, of which the best, compared with the “A man’s a man for a’ that” of Burns, sounds like a cracked pipkin against the “heroic clang” of a Damascus blade. That it is extant in the handwriting of the poet cannot be taken as a proof that it is his own composition, against the internal testimony of utter want of all the marks by which we know him—the Burns-stamp, so to speak, which is visible on all that ever came from his pen. Misled by his handwriting, I inserted in my former edition of his works an epitaph, beginning

the composition of Shenstone, and which is to be found in the church-yard of Hales-Owen: as it is not included in every edition of that poet’s acknowledged works, Burns, who was an admirer of his genius, had, it seems, copied it with his own hand, and hence my error. If I hesitated about the exclusion of “The Tree of Liberty,” and its three false brethren, I could have no scruples regarding the fine song of “Evan Banks,” claimed and justly for Miss Williams by Sir Walter Scott, or the humorous song called “Shelah O’Neal,” composed by the late Sir Alexander Boswell. When I have stated that I have arranged the Poems, the Songs, and the Letters of Burns, as nearly as possible in the order in which they were written; that I have omitted no piece of either verse or prose which bore the impress of his hand, nor included any by which his high reputation would likely be impaired, I have said all that seems necessary to be said, save that the following letter came too late for insertion in its proper place: it is characteristic and worth a place anywhere.

ALLAN CUNNINGHAM.

Mossgiel, 13th Nov. 1786.

Dear Sir,

I have along with this sent the two volumes of Ossian, with the remaining volume of the Songs. Ossian I am not in such a hurry about; but I wish the Songs, with the volume of the Scotch Poets, returned as soon as they can conveniently be dispatched. If they are left at Mr. Wilson, the bookseller’s shop, Kilmarnock, they will easily reach me.

My most respectful compliments to Mr. and Mrs. Laurie; and a Poet’s warmest wishes for their happiness to the young ladies; particularly the fair musician, whom I think much better qualified than ever David was, or could be, to charm an evil spirit out of a Saul.

Indeed, it needs not the Feelings of a poet to be interested in the welfare of one of the sweetest scenes of domestic peace and kindred love that ever I saw; as I think the peaceful unity of St. Margaret’s Hill can only be excelled by the harmonious concord of the Apocalyptic Zion.

I am, dear Sir, yours sincerely,

Robert Burns.

| PAGE | |

| The Life of Robert Burns | xxiii |

| Preface to the Kilmarnock Edition of 1786 | lix |

| Dedication to the Edinburgh Edition of 1787 | vii |

| Remarks on Scottish Songs and Ballads | 502 | |

| The Border Tour | 522 | |

| The Highland Tour | 527 | |

| Burns’s Assignment of his Works | 530 | |

| Glossary | 531 |

Robert Burns, the chief of the peasant poets of Scotland, was born in a little mud-walled cottage on the banks of Doon, near “Alloway’s auld haunted kirk,” in the shire of Ayr, on the 25th day of January, 1759. As a natural mark of the event, a sudden storm at the same moment swept the land: the gabel-wall of the frail dwelling gave way, and the babe-bard was hurried through a tempest of wind and sleet to the shelter of a securer hovel. He was the eldest born of three sons and three daughters; his father, William, who in his native Kincardineshire wrote his name Burness, was bred a gardener, and sought for work in the West; but coming from the lands of the noble family of the Keiths, a suspicion accompanied him that he had been out—as rebellion was softly called—in the forty-five: a suspicion fatal to his hopes of rest and bread, in so loyal a district; and it was only when the clergyman of his native parish certified his loyalty that he was permitted to toil. This suspicion of Jacobitism, revived by Burns himself, when he rose into fame, seems not to have influenced either the feelings, or the tastes of Agnes Brown, a young woman on the Doon, whom he wooed and married in December, 1757, when he was thirty-six years old. To support her, he leased a small piece of ground, which he converted into a nursery and garden, and to shelter her, he raised with his own hands that humble abode where she gave birth to her eldest son.

The elder Burns was a well-informed, silent, austere man, who endured no idle gaiety, nor indecorous language: while he relaxed somewhat the hard, stern creed of the Covenanting times, he enforced all the work-day, as well as sabbath-day observances, which the Calvinistic kirk requires, and scrupled at promiscuous dancing, as the staid of our own day scruple at the waltz. His wife was of a milder mood: she was blest with a singular fortitude of temper; was as devout of heart, as she was calm of mind; and loved, while busied in her household concerns, to sweeten the bitterer moments of life, by chanting the songs and ballads of her country, of which her store was great. The garden and nursery prospered so much, that he was induced to widen his views, and by the help of his kind landlord, the laird of Doonholm, and the more questionable aid of borrowed money, he entered upon a neighbouring farm, named Mount Oliphant, extending to an hundred acres. This was in 1765; but the land was hungry and sterile; the seasons proved rainy and rough; the toil was certain, the reward unsure; when to his sorrow, the laird of Doonholm—a generous Ferguson,—died: the strict terms of the lease, as well as the rent, were exacted by a harsh factor, and with his wife and children, he was obliged, after a losing struggle of six years, to relinquish the farm, and seek shelter on the grounds of Lochlea, some ten miles off, in the parish of Tarbolton. When, in after-days, men’s characters were in the hands of his eldest son, the scoundrel factor sat for that lasting portrait of insolence and wrong, in the “Twa Dogs.”

In this new farm William Burns seemed to strike root, and thrive. He was strong of body and ardent of mind: every day brought increase of vigour to his three sons, who, though very young,[xxiv] already put their hands to the plough, the reap-hook, and the flail. But it seemed that nothing which he undertook was decreed in the end to prosper: after four seasons of prosperity a change ensued: the farm was far from cheap; the gains under any lease were then so little, that the loss of a few pounds was ruinous to a farmer: bad seed and wet seasons had their usual influence: “The gloom of hermits and the moil of galley-slaves,” as the poet, alluding to those days, said, were endured to no purpose; when, to crown all, a difference arose between the landlord and the tenant, as to the terms of the lease; and the early days of the poet, and the declining years of his father, were harassed by disputes, in which sensitive minds are sure to suffer.

Amid these labours and disputes, the poet’s father remembered the worth of religious and moral instruction: he took part of this upon himself. A week-day in Lochlea wore the sober looks of a Sunday: he read the Bible and explained, as intelligent peasants are accustomed to do, the sense, when dark or difficult; he loved to discuss the spiritual meanings, and gaze on the mystical splendours of the Revelations. He was aided in these labours, first, by the schoolmaster of Alloway-mill, near the Doon; secondly, by John Murdoch, student of divinity, who undertook to teach arithmetic, grammar, French, and Latin, to the boys of Lochlea, and the sons of five neighboring farmers. Murdoch, who was an enthusiast in learning, much of a pedant, and such a judge of genius that he thought wit should always be laughing, and poetry wear an eternal smile, performed his task well: he found Robert to be quick in apprehension, and not afraid to study when knowledge was the reward. He taught him to turn verse into its natural prose order; to supply all the ellipses, and not to desist till the sense was clear and plain: he also, in their walks, told him the names of different objects both in Latin and French; and though his knowledge of these languages never amounted to much, he approached the grammar of the English tongue, through the former, which was of material use to him, in his poetic compositions. Burns was, even in those early days, a sort of enthusiast in all that concerned the glory of Scotland; he used to fancy himself a soldier of the days of the Wallace and the Bruce: loved to strut after the bag-pipe and the drum, and read of the bloody struggles of his country for freedom and existence, till “a Scottish prejudice,” he says, “was poured into my veins, which will boil there till the flood-gates of life are shut in eternal rest.”

In this mood of mind Burns was unconsciously approaching the land of poesie. In addition to the histories of the Wallace and the Bruce, he found, on the shelves of his neighbours, not only whole bodies of divinity, and sermons without limit, but the works of some of the best English, as well as Scottish poets, together with songs and ballads innumerable. On these he loved to pore whenever a moment of leisure came; nor was verse his sole favourite; he desired to drink knowledge at any fountain, and Guthrie’s Grammar, Dickson on Agriculture, Addison’s Spectator, Locke on the Human Understanding, and Taylor’s Scripture Doctrine of Original Sin, were as welcome to his heart as Shakspeare, Milton, Pope, Thomson, and Young. There is a mystery in the workings of genius: with these poets in his head and hand, we see not that he has advanced one step in the way in which he was soon to walk, “Highland Mary” and “Tam O’ Shanter” sprang from other inspirations.

Burns lifts up the veil himself, from the studies which made him a poet. “In my boyish days,” he says to Moore, “I owed much to an old woman (Jenny Wilson) who resided in the family, remarkable for her credulity and superstition. She had, I suppose, the largest collection in the country of tales and songs, concerning devils, ghosts, fairies, brownies, witches, warlocks, spunkies, kelpies, elf-candles, dead-lights, wraiths, apparitions, cantraips, giants, enchanted towers, dragons, and other trumpery. This cultivated the latent seeds of poesie; but had so strong an effect upon my imagination that to this hour, in my nocturnal rambles, I sometimes keep a look-out on suspicious places.” Here we have the young poet taking lessons in the classic lore of his native land: in the school of Janet Wilson he profited largely; her tales gave a hue, all their own, to many noble effusions. But her teaching was at the hearth-stone: when he was in the fields, either driving a cart or walking to labour, he had ever in his hand a collection of songs, such as any stall in the land could supply him with; and over these he pored, ballad by ballad, and verse by verse, noting the true, tender, and the natural sublime from affectation and fustian. “To this,” he said, “I am convinced that I owe much of my critic craft, such as it is.”[xxv] His mother, too, unconsciously led him in the ways of the muse: she loved to recite or sing to him a strange, but clever ballad, called “the Life and Age of Man:” this strain of piety and imagination was in his mind when he wrote “Man was made to Mourn.”

He found other teachers—of a tenderer nature and softer influence. “You know,” he says to Moore, “our country custom of coupling a man and woman together as partners in the labours of harvest. In my fifteenth autumn my partner was a bewitching creature, a year younger than myself: she was in truth a bonnie, sweet, sonsie lass, and unwittingly to herself, initiated me in that delicious passion, which, in spite of acid disappointment, gin-horse prudence, and bookworm philosophy, I hold to be the first of human joys. How she caught the contagion I cannot tell; I never expressly said I loved her: indeed I did not know myself why I liked so much to loiter behind with her, when returning in the evenings from our labours; why the tones of her voice made my heart strings thrill like an Æolian harp, and particularly why my pulse beat such a furious ratan, when I looked and fingered over her little hand, to pick out the cruel nettle-stings and thistles. Among other love-inspiring qualities, she sang sweetly, and it was her favourite reel to which I attempted to give an embodied vehicle in rhyme; thus with me began love and verse.” This intercourse with the fair part of the creation, was to his slumbering emotions, a voice from heaven to call them into life and poetry.

From the school of traditionary lore and love, Burns now went to a rougher academy. Lochlea, though not producing fine crops of corn, was considered excellent for flax; and while the cultivation of this commodity was committed to his father and his brother Gilbert, he was sent to Irvine at Midsummer, 1781, to learn the trade of a flax-dresser, under one Peacock, kinsman to his mother. Some time before, he had spent a portion of a summer at a school in Kirkoswald, learning mensuration and land-surveying, where he had mingled in scenes of sociality with smugglers, and enjoyed the pleasure of a silent walk, under the moon, with the young and the beautiful. At Irvine he laboured by day to acquire a knowledge of his business, and at night he associated with the gay and the thoughtless, with whom he learnt to empty his glass, and indulge in free discourse on topics forbidden at Lochlea. He had one small room for a lodging, for which he gave a shilling a week: meat he seldom tasted, and his food consisted chiefly of oatmeal and potatoes sent from his father’s house. In a letter to his father, written with great purity and simplicity of style, he thus gives a picture of himself, mental and bodily: “Honoured Sir, I have purposely delayed writing, in the hope that I should have the pleasure of seeing you on new years’ day, but work comes so hard upon us that I do not choose to be absent on that account. My health is nearly the same as when you were here, only my sleep is a little sounder, and on the whole, I am rather better than otherwise, though I mend by very slow degrees: the weakness of my nerves had so debilitated my mind that I dare neither review past wants nor look forward into futurity, for the least anxiety or perturbation in my breast produces most unhappy effects on my whole frame. Sometimes indeed, when for an hour or two my spirits are a little lightened, I glimmer a little into futurity; but my principal and indeed my only pleasurable employment is looking backwards and forwards in a moral and religious way. I am quite transported at the thought that ere long, perhaps very soon, I shall bid an eternal adieu to all the pains and uneasinesses, and disquietudes of this weary life. As for the world, I despair of ever making a figure in it: I am not formed for the bustle of the busy, nor the flutter of the gay. I foresee that poverty and obscurity probably await me, and I am in some measure prepared and daily preparing to meet them. I have but just time and paper to return you my grateful thanks for the lessons of virtue and piety you have given me, which were but too much neglected at the time of giving them, but which, I hope, have been remembered ere it is yet too late.” This remarkable letter was written in the twenty-second year of his age; it alludes to the illness which seems to have been the companion of his youth, a nervous headache, brought on by constant toil and anxiety; and it speaks of the melancholy which is the common attendant of genius, and its sensibilities, aggravated by despair of distinction. The catastrophe which happened ere this letter was well in his father’s hand, accords ill with quotations from the Bible, and hopes fixed in heaven:—“As we gave,” he says, “a welcome carousal to the new year, the shop took fire, and burnt to ashes, and I was left, like a true poet, not worth a sixpence.”[xxvi]

This disaster was followed by one more grievous: his father was well in years when he was married, and age and a constitution injured by toil and disappointment, began to press him down, ere his sons had grown up to man’s estate. On all sides the clouds began to darken: the farm was unprosperous: the speculations in flax failed; and the landlord of Lochlea, raising a question upon the meaning of the lease, concerning rotation of crop, pushed the matter to a lawsuit, alike ruinous to a poor man either in its success or its failure. “After three years tossing and whirling,” says Burns, “in the vortex of litigation, my father was just saved from the horrors of a jail by a consumption, which, after two years’ promises, kindly slept in and carried him away to where the ‘wicked cease from troubling and the weary are at rest.’ His all went among the hell-hounds that prowl in the kennel of justice. The finishing evil which brought up the rear of this infernal file, was my constitutional melancholy being increased to such a degree, that for three months I was in a state of mind scarcely to be envied by the hopeless wretches who have got their mittimus, ‘Depart from me, ye cursed.’”

Robert Burns was now the head of his father’s house. He gathered together the little that law and misfortune had spared, and took the farm of Mossgiel, near Mauchline, containing one hundred and eighteen acres, at a rent of ninety pounds a year: his mother and sisters took the domestic superintendence of home, barn, and byre; and he associated his brother Gilbert in the labours of the land. It was made a joint affair: the poet was young, willing, and vigorous, and excelled in ploughing, sowing, reaping, mowing, and thrashing. His wages were fixed at seven pounds per annum, and such for a time was his care and frugality, that he never exceeded this small allowance. He purchased books on farming, held conversations with the old and the knowing; and said unto himself, “I shall be prudent and wise, and my shadow shall increase in the land.” But it was not decreed that these resolutions were to endure, and that he was to become a mighty agriculturist in the west. Farmer Attention, as the proverb says, is a good farmer, all the world over, and Burns was such by fits and by starts. But he who writes an ode on the sheep he is about to shear, a poem on the flower that he covers with the furrow, who sees visions on his way to market, who makes rhymes on the horse he is about to yoke, and a song on the girl who shows the whitest hands among his reapers, has small chance of leading a market, or of being laird of the fields he rents. The dreams of Burns were of the muses, and not of rising markets, of golden locks rather than of yellow corn: he had other faults. It is not known that William Burns was aware before his death that his eldest son had sinned in rhyme; but we have Gilbert’s assurance, that his father went to the grave in ignorance of his son’s errors of a less venial kind—unwitting that he was soon to give a two-fold proof of both in “Rob the Rhymer’s Address to his Bastard Child”—a poem less decorous than witty.

The dress and condition of Burns when he became a poet were not at all poetical, in the minstrel meaning of the word. His clothes, coarse and homely, were made from home-grown wool, shorn off his own sheeps’ backs, carded and spun at his own fireside, woven by the village weaver, and, when not of natural hodden-gray, dyed a half-blue in the village vat. They were shaped and sewed by the district tailor, who usually wrought at the rate of a groat a day and his food; and as the wool was coarse, so also was the workmanship. The linen which he wore was home-grown, home-hackled, home-spun, home-woven, and home-bleached, and, unless designed for Sunday use, was of coarse, strong harn, to suit the tear and wear of barn and field. His shoes came from rustic tanpits, for most farmers then prepared their own leather; were armed, sole and heel, with heavy, broad-headed nails, to endure the clod and the road: as hats were then little in use, save among small lairds or country gentry, westland heads were commonly covered with a coarse, broad, blue bonnet, with a stopple on its flat crown, made in thousands at Kilmarnock, and known in all lands by the name of scone bonnets. His plaid was a handsome red and white check—for pride in poets, he said, was no sin—prepared of fine wool with more than common care by the hands of his mother and sisters, and woven with more skill than the village weaver was usually required to exert. His dwelling was in keeping with his dress, a low, thatched house, with a kitchen, a bedroom and closet, with floors of kneaded clay, and ceilings of moorland turf: a few books on a shelf, thumbed by many a thumb; a few hams drying above head in the smoke,[xxvii] which was in no haste to get out at the roof—a wooden settle, some oak chairs, chaff beds well covered with blankets, with a fire of peat and wood burning at a distance from the gable wall, on the middle of the floor. His food was as homely as his habitation, and consisted chiefly of oatmeal-porridge, barley-broth, and potatoes, and milk. How the muse happened to visit him in this clay biggin, take a fancy to a clouterly peasant, and teach him strains of consummate beauty and elegance, must ever be a matter of wonder to all those, and they are not few, who hold that noble sentiments and heroic deeds are the exclusive portion of the gently nursed and the far descended.

Of the earlier verses of Burns few are preserved: when composed, he put them on paper, but the kept them to himself: though a poet at sixteen, he seems not to have made even his brother his confidante till he became a man, and his judgment had ripened. He, however, made a little clasped paper book his treasurer, and under the head of “Observations, Hints, Songs, and Scraps of Poetry,” we find many a wayward and impassioned verse, songs rising little above the humblest country strain, or bursting into an elegance and a beauty worthy of the highest of minstrels. The first words noted down are the stanzas which he composed on his fair companion of the harvest-field, out of whose hands he loved to remove the nettle-stings and the thistles: the prettier song, beginning “Now westlin win’s and slaughtering guns,” written on the lass of Kirkoswald, with whom, instead of learning mensuration, he chose to wander under the light of the moon: a strain better still, inspired by the charms of a neighbouring maiden, of the name of Annie Ronald; another, of equal merit, arising out of his nocturnal adventures among the lasses of the west; and, finally, that crowning glory of all his lyric compositions, “Green grow the rashes.” This little clasped book, however, seems not to have been made his confidante till his twenty-third or twenty-fourth year: he probably admitted to its pages only the strains which he loved most, or such as had taken a place in his memory: at whatever age it was commenced, he had then begun to estimate his own character, and intimate his fortunes, for he calls himself in its pages “a man who had little art in making money, and still less in keeping it.”

We have not been told how welcome the incense of his songs rendered him to the rustic maidens of Kyle: women are not apt to be won by the charms of verse; they have little sympathy with dreamers on Parnassus, and allow themselves to be influenced by something more substantial than the roses and lilies of the muse. Burns had other claims to their regard then those arising from poetic skill: he was tall, young, good-looking, with dark, bright eyes, and words and wit at will: he had a sarcastic sally for all lads who presumed to cross his path, and a soft, persuasive word for all lasses on whom he fixed his fancy: nor was this all—he was adventurous and bold in love trystes and love excursions: long, rough roads, stormy nights, flooded rivers, and lonesome places, were no letts to him; and when the dangers or labours of the way were braved, he was alike skilful in eluding vigilant aunts, wakerife mothers, and envious or suspicions sisters: for rivals he had a blow as ready us he had a word, and was familiar with snug stack-yards, broomy glens, and nooks of hawthorn and honeysuckle, where maidens love to be wooed. This rendered him dearer to woman’s heart than all the lyric effusions of his fancy; and when we add to such allurements, a warm, flowing, and persuasive eloquence, we need not wonder that woman listened and was won; that one of the most charming damsels of the West said, an hour with him in the dark was worth a lifetime of light with any other body; or that the accomplished and beautiful Duchess of Gordon declared, in a latter day, that no man ever carried her so completely off her feet as Robert Burns.

It is one of the delusions of the poet’s critics and biographers, that the sources of his inspiration are to be found in the great classic poets of the land, with some of whom he had from his youth been familiar: there is little or no trace of them in any of his compositions. He read and wondered—he warmed his fancy at their flame, he corrected his own natural taste by theirs, but he neither copied nor imitated, and there are but two or three allusions to Young and Shakspeare in all the range of his verse. He could not but feel that he was the scholar of a different school, and that his thirst was to be slaked at other fountains. The language in which those great bards embodied their thoughts was unapproachable to an Ayrshire peasant; it was to him as an almost foreign tongue: he had to think and feel in the not ungraceful or inharmonious[xxviii] language of his own vale, and then, in a manner, translate it into that of Pope or of Thomson, with the additional difficulty of finding English words to express the exact meaning of those of Scotland, which had chiefly been retained because equivalents could not be found in the more elegant and grammatical tongue. Such strains as those of the polished Pope or the sublimer Milton were beyond his power, less from deficiency of genius than from lack of language: he could, indeed, write English with ease and fluency; but when he desired to be tender or impassioned, to persuade or subdue, he had recourse to the Scottish, and he found it sufficient.

The goddesses or the Dalilahs of the young poet’s song were, like the language in which he celebrated them, the produce of the district; not dames high and exalted, but lasses of the barn and of the byre, who had never been in higher company than that of shepherds or ploughmen, or danced in a politer assembly than that of their fellow-peasants, on a barn-floor, to the sound of the district fiddle. Nor even of these did he choose the loveliest to lay out the wealth of his verse upon: he has been accused, by his brother among others, of lavishing the colours of his fancy on very ordinary faces. “He had always,” says Gilbert, “a jealousy of people who were richer than himself; his love, therefore, seldom settled on persons of this description. When he selected any one, out of the sovereignty of his good pleasure, to whom he should pay his particular attention, she was instantly invested with a sufficient stock of charms out of the plentiful stores of his own imagination: and there was often a great dissimilitude between his fair captivator, as she appeared to others and as she seemed when invested with the attributes he gave her.” “My heart,” he himself, speaking of those days, observes, “was completely tinder, and was eternally lighted up by some goddess or other.” Yet, it must be acknowledged that sufficient room exists for believing that Burns and his brethren of the West had very different notions of the captivating and the beautiful; while they were moved by rosy checks and looks of rustic health, he was moved, like a sculptor, by beauty of form or by harmony of motion, and by expression, which lightened up ordinary features and rendered them captivating. Such, I have been told, were several of the lasses of the West, to whom, if he did not surrender his heart, he rendered homage: and both elegance of form and beauty of face were visible to all in those of whom he afterwards sang—the Hamiltons and the Burnets of Edinburgh, and the Millers and M’Murdos of the Nith.

The mind of Burns took now a wider range: he had sung of the maidens of Kyle in strains not likely soon to die, and though not weary of the softnesses of love, he desired to try his genius on matters of a sterner kind—what those subjects were he tells us; they were homely and at hand, of a native nature and of Scottish growth: places celebrated in Roman story, vales made famous in Grecian song—hills of vines and groves of myrtle had few charms for him. “I am hurt,” thus he writes in August, 1785, “to see other towns, rivers, woods, and haughs of Scotland immortalized in song, while my dear native county, the ancient Baillieries of Carrick, Kyle, and Cunningham, famous in both ancient and modern times for a gallant and warlike race of inhabitants—a county where civil and religious liberty have ever found their first support and their asylum—a county, the birth-place of many famous philosophers, soldiers, and statesmen, and the scene of many great events recorded in history, particularly the actions of the glorious Wallace—yet we have never had one Scotch poet of any eminence to make the fertile banks of Irvine, the romantic woodlands and sequestered scenes of Ayr. and the mountainous source and winding sweep of the Doon, emulate Tay, Forth, Ettrick, and Tweed. This is a complaint I would gladly remedy, but, alas! I am far unequal to the task, both in genius and education.” To fill up with glowing verse the outline which this sketch indicates, was to raise the long-laid spirit of national song—to waken a strain to which the whole land would yield response—a miracle unattempted—certainly unperformed—since the days of the Gentle Shepherd. It is true that the tongue of the muse had at no time been wholly silent; that now and then a burst of sublime woe, like the song of “Mary, weep no more for me,” and of lasting merriment and humour, like that of “Tibbie Fowler,” proved that the fire of natural poesie smouldered, if it did not blaze; while the social strains of the unfortunate Fergusson revived in the city, if not in the field, the memory of him who sang the “Monk and the Miller’s wife.” But notwithstanding these and other productions of equal merit, Scottish poesie, it must be owned, had lost much of its original ecstasy[xxix] and fervour, and that the boldest efforts of the muse no more equalled the songs of Dunbar, of Douglas, of Lyndsay, and of James the Fifth, than the sound of an artificial cascade resembles the undying thunders of Corra.

To accomplish this required an acquaintance with man beyond what the forge, the change-house, and the market-place of the village supplied; a look further than the barn-yard and the furrowed field, and a livelier knowledge and deeper feeling of history than, probably, Burns ever possessed. To all ready and accessible sources of knowledge he appears to have had recourse; he sought matter for his muse in the meetings, religious as well as social, of the district—consorted with staid matrons, grave plodding farmers—with those who preached as well as those who listened—with sharp-tongued attorneys, who laid down the law over a Mauchline gill—with country squires, whose wisdom was great in the game-laws, and in contested elections—and with roving smugglers, who at that time hung, as a cloud, on all the western coast of Scotland. In the company of farmers and fellow-peasants, he witnessed scenes which he loved to embody in verse, saw pictures of peace and joy, now woven into the web of his song, and had a poetic impulse given to him both by cottage devotion and cottage merriment. If he was familiar with love and all its outgoings and incomings—had met his lass in the midnight shade, or walked with her under the moon, or braved a stormy night and a haunted road for her sake—he was as well acquainted with the joys which belong to social intercourse, when instruments of music speak to the feet, when the reek of punchbowls gives a tongue to the staid and demure, and bridal festivity, and harvest-homes, bid a whole valley lift up its voice and be glad. It is more difficult to decide what poetic use he could make of his intercourse with that loose and lawless class of men, who, from love of gain, broke the laws and braved the police of their country: that he found among smugglers, as he says, “men of noble virtues, magnanimity, generosity, disinterested friendship, and modesty,” is easier to believe than that he escaped the contamination of their sensual manners and prodigality. The people of Kyle regarded this conduct with suspicion: they were not to be expected to know that when Burns ranted and housed with smugglers, conversed with tinkers huddled in a kiln, or listened to the riotous mirth of a batch of “randie gangrel bodies” as they “toomed their powks and pawned their duds,” for liquor in Poosie Nansie’s, he was taking sketches for the future entertainment and instruction of the world; they could not foresee that from all this moral strength and poetic beauty would arise.

While meditating something better than a ballad to his mistress’s eyebrow, he did not neglect to lay out the little skill he had in cultivating the grounds of Mossgiel. The prosperity in which he found himself in the first and second seasons, induced him to hope that good fortune had not yet forsaken him: a genial summer and a good market seldom come together to the farmer, but at first they came to Burns; and to show that he was worthy of them, he bought books on agriculture, calculated rotation of crops, attended sales, held the plough with diligence, used the scythe, the reap-hook, and the flail, with skill, and the malicious even began to say that there was something more in him than wild sallies of wit and foolish rhymes. But the farm lay high, the bottom was wet, and in a third season, indifferent seed and a wet harvest robbed him at once of half his crop: he seems to have regarded this as an intimation from above, that nothing which he undertook would prosper: and consoled himself with joyous friends and with the society of the muse. The judgment cannot be praised which selected a farm with a wet cold bottom, and sowed it with unsound seed; but that man who despairs because a wet season robs him of the fruits of the field, is unfit for the warfare of life, where fortitude is as much required as by a general on a field of battle, when the tide of success threatens to flow against him. The poet seems to have believed, very early in life, that he was none of the elect of Mammon; that he was too much of a genius ever to acquire wealth by steady labour, or by, as he loved to call it, gin-horse prudence, or grubbing industry.

And yet there were hours and days in which Burns, even when the rain fell on his unhoused sheaves, did not wholly despair of himself: he laboured, nay sometimes he slaved on his farm; and at intervals of toil, sought to embellish his mind with such knowledge as might be useful, should chance, the goddess who ruled his lot, drop him upon some of the higher places of the land. He had, while he lived at Tarbolton, united with some half-dozen young men, all sons of[xxx] farmers in that neighbourhood, in forming a club, of which the object was to charm away a few evening hours in the week with agreeable chit-chat, and the discussion of topics of economy or love. Of this little society the poet was president, and the first question they were called on to settle was this, “Suppose a young man bred a farmer, but without any fortune, has it in his power to marry either of two women; the one a girl of large fortune, but neither handsome in person, nor agreeable in conversation, but who can manage the household affairs of a farm well enough; the other of them, a girl every way agreeable in person, conversation, and behaviour, but without any fortune, which of them shall he choose?” This question was started by the poet, and once every week the club were called to the consideration of matters connected with rural life and industry: their expenses were limited to threepence a week; and till the departure of Burns to the distant Mossgiel, the club continued to live and thrive; on his removal it lost the spirit which gave it birth, and was heard of no more; but its aims and its usefulness were revived in Mauchline, where the poet was induced to establish a society which only differed from the other in spending the moderate fines arising from non-attendance, on books, instead of liquor. Here, too, Burns was the president, and the members were chiefly the sons of husbandmen, whom he found, he said, more natural in their manners, and more agreeable than the self-sufficient mechanics of villages and towns, who were ready to dispute on all topics, and inclined to be convinced on none. This club had the pleasure of subscribing for the first edition of the works of its great associate. It has been questioned by his first biographer, whether the refinement of mind, which follows the reading of books of eloquence and delicacy,—the mental improvement resulting from such calm discussions as the Tarbolton and Mauchline clubs indulged in, was not injurious to men engaged in the barn and at the plough. A well-ordered mind will be strengthened, as well as embellished, by elegant knowledge, while over those naturally barren and ungenial all that is refined or noble will pass as a sunny shower scuds over lumps of granite, bringing neither warmth nor life.

In the account which the poet gives to Moore of his early poems, he says little about his exquisite lyrics, and less about “The Death and dying Words of Poor Mailie,” or her “Elegy,” the first of his poems where the inspiration of the muse is visible; but he speaks with exultation of the fame which those indecorous sallies, “Holy Willie’s Prayer” and “The Holy Tulzie” brought from some of the clergy, and the people of Ayrshire. The west of Scotland is ever in the van, when mutters either political or religious are agitated. Calvinism was shaken, at this time, with a controversy among its professors, of which it is enough to say, that while one party rigidly adhered to the word and letter of the Confession of Faith, and preached up the palmy and wholesome days of the Covenant, the other sought to soften the harsher rules and observances of the kirk, and to bring moderation and charity into its discipline as well as its councils. Both believed themselves right, both were loud and hot, and personal,—bitter with a bitterness only known in religious controversy. The poet sided with the professors of the New Light, as the more tolerant were called, and handled the professors of the Old Light, as the other party were named, with the most unsparing severity. For this he had sufficient cause:—he had experienced the mercilessness of kirk-discipline, when his frailties caused him to visit the stool of repentance; and moreover his friend Gavin Hamilton, a writer in Mauchline, had been sharply censured by the same authorities, for daring to gallop on Sundays. Moodie, of Riccarton, and Russel, of Kilmarnock, were the first who tasted of the poet’s wrath. They, though professors of the Old Light, had quarrelled, and, it is added, fought: “The Holy Tulzie,” which recorded, gave at the same time wings to the scandal; while for “Holy Willie,” an elder of Mauchline, and an austere and hollow pretender to righteousness, he reserved the fiercest of all his lampoons. In “Holy Willie’s Prayer,” he lays a burning hand on the terrible doctrine of predestination: this is a satire, daring, personal, and profane. Willie claims praise in the singular, acknowledges folly in the plural, and makes heaven accountable for his sins! in a similar strain of undevout satire, he congratulates Goudie, of Kilmarnock, on his Essays on Revealed Religion. These poems, particularly the two latter, are the sharpest lampoons in the language.

While drudging in the cause of the New Light controversialists, Burns was not unconsciously strengthening his hands for worthier toils: the applause which selfish divines bestowed on his[xxxi] witty, but graceless effusions, could not be enough for one who knew how fleeting the fame was which came from the heat of party disputes; nor was he insensible that songs of a beauty unknown for a century to national poesy, had been unregarded in the hue and cry which arose on account of “Holy Willie’s Prayer” and “The Holy Tulzie.” He hesitated to drink longer out of the agitated puddle of Calvinistic controversy, he resolved to slake his thirst at the pure well-springs of patriot feeling and domestic love; and accordingly, in the last and best of his controversial compositions, he rose out of the lower regions of lampoon into the upper air of true poetry. “The Holy Fair,” though stained in one or two verses with personalities, exhibits a scene glowing with character and incident and life: the aim of the poem is not so much to satirize one or two Old Light divines, as to expose and rebuke those almost indecent festivities, which in too many of the western parishes accompanied the administration of the sacrament. In the earlier days of the church, when men were staid and sincere, it was, no doubt, an impressive sight to see rank succeeding rank, of the old and the young, all calm and all devout, seated before the tent of the preacher, in the sunny hours of June, listening to his eloquence, or partaking of the mystic bread and wine; but in these our latter days, when discipline is relaxed, along with the sedate and the pious come swarms of the idle and the profligate, whom no eloquence can edify and no solemn rite affect. On these, and such as these, the poet has poured his satire; and since this desirable reprehension the Holy Fairs, east as well as west, have become more decorous, if not more devout.

His controversial sallies were accompanied, or followed, by a series of poems which showed that national character and manners, as Lockhart has truly and happily said, were once more in the hands of a national poet. These compositions are both numerous and various: they record the poet’s own experience and emotions; they exhibit the highest moral feeling, the purest patriotic sentiments, and a deep sympathy with the fortunes, both here and hereafter of his fellow-men; they delineate domestic manners, man’s stern as well as social hours, and mingle the serious with the joyous, the sarcastic with the solemn, the mournful with the pathetic, the amiable with the gay, and all with an ease and unaffected force and freedom known only to the genius of Shakspeare. In “The Twa Dogs” he seeks to reconcile the labourer to his lot, and intimates, by examples drawn from the hall as well as the cottage, that happiness resides in the humblest abodes, and is even partial to the clouted shoe. In “Scotch Drink” he excites man to love his country, by precepts both heroic and social; and proves that while wine and brandy are the tipple of slaves, whiskey and ale are the drink of the free: sentiments of a similar kind distinguish his “Earnest Cry and Prayer to the Scotch Representatives in the House of Commons,” each of whom he exhorts by name to defend the remaining liberties and immunities of his country. A higher tone distinguishes the “Address to the Deil:” he records all the names, and some of them are strange ones; and all the acts, and some of them are as whimsical as they are terrible, of this far kenned and noted personage; to these he adds some of the fiend’s doings as they stand in Scripture, together with his own experiences; and concludes by a hope, as unexpected as merciful and relenting, that Satan may not be exposed to an eternity of torments. “The Dream” is a humorous sally, and may be almost regarded as prophetic. The poet feigns himself present, in slumber, at the Royal birth-day; and supposes that he addresses his majesty, on his household matters as well as the affairs of the nation. Some of the princes, it has been satirically hinted, behaved afterwards in such a way as if they wished that the scripture of the Burns should be fulfilled: in this strain, he has imitated the license and equalled the wit of some of the elder Scottish Poets.

“The Vision” is wholly serious; it exhibits the poet in one of those fits of despondency which the dull, who have no misgivings, never know: he dwells with sarcastic bitterness on the opportunities which, for the sake of song, he has neglected of becoming wealthy, and is drawing a sad parallel between rags and riches, when the muse steps in and cheer his despondency, by assuring him of undying fame. “Halloween” is a strain of a more homely kind, recording the superstitious beliefs, and no less superstitious doings of Old Scotland, on that night, when witches and elves and evil spirits are let loose among the children of men: it reaches far back into manners and customs, and is a picture, curious and valuable. The tastes and feelings of husbandmen[xxxii] inspired “The old Farmer’s Address to his old mare Maggie,” which exhibits some pleasing recollections of his days of courtship and hours of sociality. The calm, tranquil picture of household happiness and devotion in “the Cotter’s Saturday Night,” has induced Hogg, among others, to believe that it has less than usual of the spirit of the poet, but it has all the spirit that was required; the toil of the week has ceased, the labourer has returned to his well-ordered home—his “cozie ingle and his clean hearth-stane,”—and with his wife and children beside him, turns his thoughts to the praise of that God to whom he owes all: this he performs with a reverence and an awe, at once natural, national, and poetic. “The Mouse” is a brief and happy and very moving poem: happy, for it delineates, with wonderful truth and life, the agitation of the mouse when the coulter broke into its abode; and moving, for the poet takes the lesson of ruin to himself, and feels the present and dreads the future. “The Mountain Daisy,” once, more properly, called by Burns “The Gowan,” resembles “The Mouse” in incident and in moral, and is equally happy, in language and conception. “The Lament” is a dark, and all but tragic page, from the poet’s own life. “Man was made to Mourn’” takes the part of the humble and the homeless, against the coldness and selfishness of the wealthy and the powerful, a favourite topic of meditation with Burns. He refrained, for awhile, from making “Death and Doctor Hernbook” public; a poem which deviates from the offensiveness of personal satire, into a strain of humour, at once airy and original.

His epistles in verse may be reckoned amongst his happiest productions: they are written in all moods of mind, and are, by turns, lively and sad; careless and serious;—now giving advice, then taking it; laughing at learning, and lamenting its want; scoffing at propriety and wealth, yet admitting, that without the one he cannot be wise, nor wanting the other, independent. The Epistle to David Sillar is the first of these compositions: the poet has no news to tell, and no serious question to ask: he has only to communicate his own emotions of joy, or of sorrow, and these he relates and discusses with singular elegance as well as ease, twining, at the same time, into the fabric of his composition, agreeable allusions to the taste and affections of his correspondent. He seems to have rated the intellect of Sillar as the highest among his rustic friends: he pays him more deference, and addresses him in a higher vein than he observes to others. The Epistles to Lapraik, to Smith, and to Rankine, are in a more familiar, or social mood, and lift the veil from the darkness of the poet’s condition, and exhibit a mind of first-rate power, groping, and that surely, its way to distinction, in spite of humility of birth, obscurity of condition, and the coldness of the wealthy or the titled. The epistles of other poets owe some of their fame to the rank or the reputation of those to whom they are addressed; those of Burns are written, one and all, to nameless and undistinguished men. Sillar was a country schoolmaster, Lapraik a moorland laird, Smith a small shop-keeper, and Rankine a farmer, who loved a gill and a joke. Yet these men were the chief friends, the only literary associates of the poet, during those early years, in which, with some exceptions, his finest works were written.

Burns, while he was writing the poems, the chief of which we have named, was a labouring husbandman on the little farm of Mossgiel, a pursuit which affords but few leisure hours for either reading or pondering; but to him the stubble-field was musing-ground, and the walk behind the plough, a twilight saunter on Parnassus. As, with a careful hand and a steady eye, he guided his horses, and saw an evenly furrow turned up by the share, his thoughts were on other themes; he was straying in haunted glens, when spirits have power—looking in fancy on the lasses “skelping barefoot,” in silks and in scarlets, to a field-preaching—walking in imagination with the rosy widow, who on Halloween ventured to dip her left sleeve in the burn, where three lairds’ lands met—making the “bottle clunk,” with joyous smugglers, on a lucky run of gin or brandy—or if his thoughts at all approached his acts—he was moralizing on the daisy oppressed by the furrow which his own ploughshare had turned. That his thoughts were thus wandering we have his own testimony, with that of his brother Gilbert; and were both wanting, the certainty that he composed the greater part of his immortal poems in two years, from the summer of 1784 to the summer of 1786, would be evidence sufficient. The muse must have been strong within him, when, in spite of the rains and sleets of the “ever-dropping west”—when in defiance of the hot and sweaty brows occasioned by reaping and thrashing—declining markets, and showery[xxxiii] harvests—the clamour of his laird for his rent, and the tradesman for his account, he persevered in song, and sought solace in verse, when all other solace was denied him.

The circumstances under which his principal poems were composed, have been related: the “Lament of Mailie” found its origin in the catastrophe of a pet ewe; the “Epistle to Sillar” was confided by the poet to his brother while they were engaged in weeding the kale-yard; the “Address to the Deil” was suggested by the many strange portraits which belief or fear had drawn of Satan, and was repeated by the one brother to the other, on the way with their carts to the kiln, for lime; the “Cotter’s Saturday Night” originated in the reverence with which the worship of God was conducted in the family of the poet’s father, and in the solemn tone with which he desired his children to compose themselves for praise and prayer; “the Mouse,” and its moral companion “the Daisy,” were the offspring of the incidents which they relate; and “Death and Doctor Hornbook” was conceived at a freemason-meeting, where the hero of the piece had shown too much of the pedant, and composed on his way home, after midnight, by the poet, while his head was somewhat dizzy with drink. One of the most remarkable of his compositions, the “Jolly Beggars,” a drama, to which nothing in the language of either the North or South can be compared, and which was unknown till after the death of the author, was suggested by a scene which he saw in a low ale-house, into which, on a Saturday night, most of the sturdy beggars of the district had met to sell their meal, pledge their superfluous rags, and drink their gains. It may be added, that he loved to walk in solitary spots; that his chief musing-ground was the banks of the Ayr; the season most congenial to his fancy that of winter, when the winds were heard in the leafless woods, and the voice of the swollen streams came from vale and hill; and that he seldom composed a whole poem at once, but satisfied with a few fervent verses, laid the subject aside, till the muse summoned him to another exertion of fancy. In a little back closet, still existing in the farm-house of Mossgiel, he committed most of his poems to paper.

But while the poet rose, the farmer sank. It was not the cold clayey bottom of his ground, nor the purchase of unsound seed-corn, not the fluctuation in the markets alone, which injured him; neither was it the taste for freemason socialities, nor a desire to join the mirth of comrades, either of the sea or the shore: neither could it be wholly imputed to his passionate following of the softer sex—indulgence in the “illicit rove,” or giving way to his eloquence at the feet of one whom he loved and honoured; other farmers indulged in the one, or suffered from the other, yet were prosperous. His want of success arose from other causes; his heart was not with his task, save by fits and starts: he felt he was designed for higher purposes than ploughing, and harrowing, and sowing, and reaping: when the sun called on him, after a shower, to come to the plough, or when the ripe corn invited the sickle, or the ready market called for the measured grain, the poet was under other spells, and was slow to avail himself of those golden moments which come but once in the season. To this may be added, a too superficial knowledge of the art of farming, and a want of intimacy with the nature of the soil he was called to cultivate. He could speak fluently of leas, and faughs, and fallows, of change of seed and rotation of crops, but practical knowledge and application were required, and in these Burns was deficient. The moderate gain which those dark days of agriculture brought to the economical farmer, was not obtained: the close, the all but niggardly care by which he could win and keep his crown-piece,—gold was seldom in the farmer’s hand,—was either above or below the mind of the poet, and Mossgiel, which, in the hands of an assiduous farmer, might have made a reasonable return for labour, was unproductive, under one who had little skill, less economy, and no taste for the task.

Other reasons for his failure have been assigned. It is to the credit of the moral sentiments of the husbandmen of Scotland, that when one of their class forgets what virtue requires, and dishonours, without reparation, even the humblest of the maidens, he is not allowed to go unpunished. No proceedings take place, perhaps one hard word is not spoken; but he is regarded with loathing by the old and the devout; he is looked on by all with cold and reproachful eyes—sorrow is foretold as his lot, sure disaster as his fortune; and is these chance to arrive, the only sympathy expressed is, “What better could he expect?” Something of this sort befel Burns: he had already satisfied the kirk in the matter of “Sonsie, smirking, dear-bought Bess,” his daughter, by one of his mother’s maids; and now, to use his own words, he was brought within point-blank[xxxiv] of the heaviest metal of the kirk by a similar folly. The fair transgressor, both for her fathers and her own youth, had a large share of public sympathy. Jean Armour, for it is of her I speak, was in her eighteenth year; with dark eyes, a handsome foot, and a melodious tongue, she made her way to the poet’s heart—and, as their stations in life were equal, it seemed that they had only to be satisfied themselves to render their union easy. But her father, in addition to being a very devout man, was a zealot of the Old Light; and Jean, dreading his resentment, was willing, while she loved its unforgiven satirist, to love him in secret, in the hope that the time would come when she might safely avow it: she admitted the poet, therefore, to her company in lonesome places, and walks beneath the moon, where they both forgot themselves, and were at last obliged to own a private marriage as a protection from kirk censure. The professors of the Old Light rejoiced, since it brought a scoffing rhymer within reach of their hand; but her father felt a twofold sorrow, because of the shame of a favourite daughter, and for having committed the folly with one both loose in conduct and profane of speech. He had cause to be angry, but his anger, through his zeal, became tyrannous: in the exercise of what he called a father’s power, he compelled his child to renounce the poet as her husband and burn the marriage-lines; for he regarded her marriage, without the kirk’s permission, with a man so utterly cast away, as a worse crime than her folly. So blind is anger! She could renounce neither her husband nor his offspring in a lawful way, and in spite of the destruction of the marriage lines, and renouncing the name of wife, she was as much Mrs. Burns as marriage could make her. No one concerned seemed to think so. Burns, who loved her tenderly, went all but mad when she renounced him: he gave up his share of Mossgiel to his brother, and roamed, moody and idle, about the land, with no better aim in life than a situation in one of our western sugar-isles, and a vague hope of distinction as a poet.

How the distinction which he desired as a poet was to be obtained, was, to a poor bard in a provincial place, a sore puzzle: there were no enterprising booksellers in the western land, and it was not to be expected that the printers of either Kilmarnock or Paisley had money to expend on a speculation in rhyme: it is much to the honour of his native county that the publication which he wished for was at last made easy. The best of his poems, in his own handwriting, had found their way into the hands of the Ballantynes, Hamiltons, Parkers, and Mackenzies, and were much admired. Mrs. Stewart, of Stair and Afton, a lady of distinction and taste, had made, accidentally, the acquaintance both of Burns and some of his songs, and was ready to befriend him; and so favourable was the impression on all hands, that a subscription, sufficient to defray the outlay of paper and print, was soon filled up—one hundred copies being subscribed for by the Parkers alone. He soon arranged materials for a volume, and put them into the hands of a printer in Kilmarnock, the Wee Johnnie of one of his biting epigrams. Johnnie was startled at the unceremonious freedom of most of the pieces, and asked the poet to compose one of modest language and moral aim, to stand at the beginning, and excuse some of those free ones which followed: Burns, whose “Twa Dogs” was then incomplete, finished the poem at a sitting, and put it in the van, much to his printer’s satisfaction. If the “Jolly Beggars” was omitted for any other cause than its freedom of sentiment and language, or “Death and Doctor Hornbook” from any other feeling than that of being too personal, the causes of their exclusion have remained a secret. It is less easy to account for the emission of many songs of high merit which he had among his papers: perhaps he thought those which he selected were sufficient to test the taste of the public. Before he printed the whole, he, with the consent of his brother, altered his name from Burness to Burns, a change which, I am told, he in after years regretted.

In the summer of the year 1786, the little volume, big with the hopes and fortunes of the bard made its appearance: it was entitled simply, “Poems, chiefly in the Scottish Dialect; by Robert Burns;” and accompanied by a modest preface, saying, that he submitted his book to his country with fear and with trembling, since it contained little of the art of poesie, and at the best was but a voice given, rude, he feared, and uncouth, to the loves, the hopes, and the fears of his own bosom. Had a summer sun risen on a winter morning, it could not have surprised the Lowlands of Scotland more than this Kilmarnock volume surprised and delighted the people, one and all. The milkmaid sang his songs, the ploughman repeated his poems; the old quoted both, and ever[xxxv] the devout rejoiced that idle verse had at last mixed a tone of morality with its mirth. The volume penetrated even into Nithsdale. “Keep it out of the way of your children,” said a Cameronian divine, when he lent it to my father, “lest ye find them, as I found mine, reading it on the Sabbath.” No wonder that such a volume made its way to the hearts of a peasantry whose taste in poetry had been the marvel of many writers: the poems were mostly on topics with which they were familiar: the language was that of the fireside, raised above the vulgarities of common life, by a purifying spirit of expression and the exalting fervour of inspiration: and there was such a brilliant and graceful mixture of the elegant and the homely, the lofty and the low, the familiar and the elevated—such a rapid succession of scenes which moved to tenderness or tears; or to subdued mirth or open laughter—unlooked for allusions to scripture, or touches of sarcasm and scandal—of superstitions to scare, and of humour to delight—while through the whole was diffused, as the scent of flowers through summer air, a moral meaning—a sentimental beauty, which sweetened and sanctified all. The poet’s expectations from this little venture were humble: he hoped as much money from it as would pay for his passage to the West Indies, where he proposed to enter into the service of some of the Scottish settlers, and help to manage the double mystery of sugar-making and slavery.

The hearty applause which I have recorded came chiefly from the husbandman, the shepherd, and the mechanic: the approbation of the magnates of the west, though not less-warm, was longer in coming. Mrs. Stewart of Stair, indeed, commended the poems and cheered their author: Dugald Stewart received his visits with pleasure, and wondered at his vigour of conversation as much as at his muse: the door of the house of Hamilton was open to him, where the table was ever spread, and the hand ever ready to help: while the purses of the Ballantynes and the Parkers were always as open to him as were the doors of their houses. Those persons must be regarded as the real patrons of the poet: the high names of the district are not to be found among those who helped him with purse and patronage in 1786, that year of deep distress and high distinction. The Montgomerys came with their praise when his fame was up; the Kennedys and the Boswells were silent: and though the Cunninghams gave effectual aid, it was when the muse was crying with a loud voice before him, “Come all and see the man whom I delight to honour.” It would be unjust as well as ungenerous not to mention the name of Mrs. Dunlop among the poet’s best and early patrons: the distance at which she lived from Mossgiel had kept his name from her till his poems appeared: but his works induced her to desire his acquaintance, and she became his warmest and surest friend.

To say the truth, Burns endeavoured in every honourable way to obtain the notice of those who had influence in the land: he copied out the best of his unpublished poems in a fair hand, and inserting them in his printed volume, presented it to those who seemed slow to buy: he rewarded the notice of this one with a song—the attentions of that one with a sally of encomiastic verse: he left psalms of his own composing in the manse when he feasted with a divine: he enclosed “Holy Willie’s Prayer,” with an injunction to be grave, to one who loved mirth: he sent the “Holy Fair” to one whom he invited to drink a gill out of a mutchkin stoup, at Mauchline market; and on accidentally meeting with Lord Daer, he immediately commemorated the event in a sally of verse, of a strain more free and yet as flattering as ever flowed from the lips of a court bard. While musing over the names of those on whom fortune had smiled, yet who had neglected to smile on him, he remembered that he had met Miss Alexander, a young beauty of the west, in the walks of Ballochmyle; and he recorded the impression which this fair vision made on him in a song of unequalled elegance and melody. He had met her in the woods in July, on the 18th of November he sent her the song, and reminded her of the circumstance from which it arose, in a letter which it is evident he had laboured to render polished and complimentary. The young lady took no notice of either the song or the poet, though willing, it is said, to hear of both now:—this seems to have been the last attempt he made on the taste or the sympathies of the gentry of his native district: for on the very day following we find him busy in making arrangements for his departure to Jamaica.

For this step Burns had more than sufficient reasons: the profits of his volume amounted to little more than enough to waft him across the Atlantic: Wee Johnnie, though the edition was[xxxvi] all sold, refused to risk another on speculation: his friends, both Ballantynes and Parkers, volunteered to relieve the printer’s anxieties, but the poet declined their bounty, and gloomily indented himself in a ship about to sail from Greenock, and called on his muse to take farewell of Caledonia, in the last song he ever expected to measure in his native land. That fine lyric, beginning “The gloomy night is gathering fast,” was the offspring of these moments of regret and sorrow. His feelings were not expressed in song alone: he remembered his mother and his natural daughter, and made an assignment of all that pertained to him at Mossgiel—and that was but little—and of all the advantage which a cruel, unjust, and insulting law allowed in the proceeds of his poems, for their support and behoof. This document was publicly read in the presence of the poet, at the market-cross of Ayr, by his friend William Chalmers, a notary public. Even this step was to Burns one of danger: some ill-advised person had uncoupled the merciless pack of the law at his heels, and he was obliged to shelter himself as he best could, in woods, it is said, by day and in barns by night, till the final hour of his departure came. That hour arrived, and his chest was on the way to the ship, when a letter was put into his hand which seemed to light him to brighter prospects.

Among the friends whom his merits had procured him was Dr. Laurie, a district clergyman, who had taste enough to admire the deep sensibilities as well as the humour of the poet, and the generosity to make known both his works and his worth to the warm-hearted and amiable Blacklock, who boldly proclaimed him a poet of the first rank, and lamented that he was not in Edinburgh to publish another edition of his poems. Burns was ever a man of impulse: he recalled his chest from Greenock; he relinquished the situation he had accepted on the estate of one Douglas; took a secret leave of his mother, and, without an introduction to any one, and unknown personally to all, save to Dugald Stewart, away he walked, through Glenap, to Edinburgh, full of new hope and confiding in his genius. When he arrived, he scarcely knew what to do: he hesitated to call on the professor; he refrained from making himself known, as it has been supposed he did, to the enthusiastic Blacklock; but, sitting down in an obscure lodging, he sought out an obscure printer, recommended by a humble comrade from Kyle, and began to negotiate for a new edition of the Poems of the Ayrshire Ploughman. This was not the way to go about it: his barge had well nigh been shipwrecked in the launch; and he might have lived to regret the letter which hindered his voyage to Jamaica, had he not met by chance in the street a gentleman of the west, of the name of Dalzell, who introduced him to the Earl of Glencairn, a nobleman whose classic education did not hurt his taste for Scottish poetry, and who was not too proud to lend his helping hand to a rustic stranger of such merit as Burns. Cunningham carried him to Creech, then the Murray of Edinburgh, a shrewd man of business, who opened the poet’s eyes to his true interests: the first proposals, then all but issued, were put in the fire, and new ones printed and diffused over the island. The subscription was headed by half the noblemen of the north: the Caledonian Hunt, through the interest of Glencairn, took six hundred copies: duchesses and countesses swelled the list, and such a crowding to write down names had not been witnessed since the signing of the solemn league and covenant.

While the subscription-papers were filling and the new volume printing on a paper and in a type worthy of such high patronage, Burns remained in Edinburgh, where, for the winter season, he was a lion, and one of an unwonted kind. Philosophers, historians, and scholars had shaken the elegant coteries of the city with their wit, or enlightened them with their learning, but they were all men who had been polished by polite letters or by intercourse with high life, and there was a sameness in their very dress as well as address, of which peers and peeresses had become weary. They therefore welcomed this rustic candidate for the honour of giving wings to their hours of lassitude and weariness, with a welcome more than common; and when his approach was announced, the polished circle looked for the advent of a lout from the plough, in whose uncouth manners and embarrassed address they might find matter both for mirth and wonder. But they met with a barbarian who was not at all barbarous: as the poet met in Lord Daer feelings and sentiments as natural as those of a ploughman, so they met in a ploughman manners worthy of a lord: his air was easy and unperplexed: his address was perfectly well-bred, and elegant in its simplicity: he felt neither eclipsed by the titled nor struck dumb before the[xxxvii] learned and the eloquent, but took his station with the ease and grace of one born to it. In the society of men alone he spoke out: he spared neither his wit, his humour, nor his sarcasm—he seemed to say to all—“I am a man, and you are no more; and why should I not act and speak like one?”—it was remarked, however, that he had not learnt, or did not desire, to conceal his emotions—that he commended with more rapture than was courteous, and contradicted with more bluntness than was accounted polite. It was thus with him in the company of men: when woman approached, his look altered, his eye beamed milder; all that was stern in his nature underwent a change, and he received them with deference, but with a consciousness that he could win their attention as he had won that of others, who differed, indeed, from them only in the texture of their kirtles. This natural power of rendering himself acceptable to women had been observed and envied by Sillar, one of the dearest of his early comrades; and it stood him in good stead now, when he was the object to whom the Duchess of Gordon, the loveliest as well as the wittiest of women—directed her discourse. Burns, she afterwards said, won the attention of the Edinburgh ladies by a deferential way of address—by an ease and natural grace of manners, as new as it was unexpected—that he told them the stories of some of his tenderest songs or liveliest poems in a style quite magical—enriching his little narratives, which had one and all the merit of being short, with personal incidents of humour or of pathos.

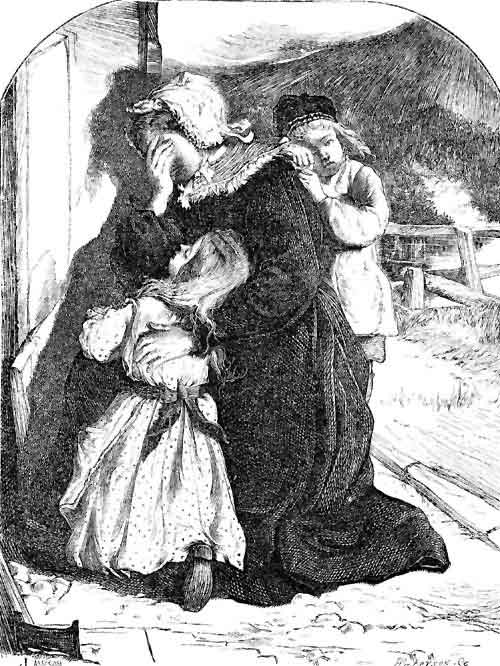

In a party, when Dr. Blair and Professor Walker were present, Burns related the circumstances under which he had composed his melancholy song, “The gloomy night is gathering fast,” in a way even more touching than the verses: and in the company of the ruling beauties of the time, he hesitated not to lift the veil from some of the tenderer parts of his own history, and give them glimpses of the romance of rustic life. A lady of birth—one of his must willing listeners—used, I am told, to say, that she should never forget the tale which he related of his affection for Mary Campbell, his Highland Mary, as he loved to call her. She was fair, he said, and affectionate, and as guileless as she was beautiful; and beautiful he thought her in a very high degree. The first time he saw her was during one of his musing walks in the woods of Montgomery Castle; and the first time he spoke to her was during the merriment of a harvest-kirn. There were others there who admired her, but he addressed her, and had the luck to win her regard from them all. He soon found that she was the lass whom he had long sought, but never before found—that her good looks were surpassed by her good sense; and her good sense was equalled by her discretion and modesty. He met her frequently: she saw by his looks that he was sincere; she put full trust in his love, and used to wander with him among the green knowes and stream-banks till the sun went down and the moon rose, talking, dreaming of love and the golden days which awaited them. He was poor, and she had only her half-year’s fee, for she was in the condition of a servant; but thoughts of gear never darkened their dream: they resolved to wed, and exchanged vows of constancy and love. They plighted their vows on the Sabbath to render them more sacred—they made them by a burn, where they had courted, that open nature might be a witness—they made them over an open Bible, to show that they thought of God in this mutual act—and when they had done they both took water in their hands, and scattered it in the air, to intimate that as the stream was pure so were their intentions. They parted when they did this, but they parted never to meet more: she died in a burning fever, during a visit to her relations to prepare for her marriage; and all that he had of her was a lock of her long bright hair, and her Bible, which she exchanged for his.