The Project Gutenberg EBook of Blister Jones, by John Taintor Foote This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Blister Jones Author: John Taintor Foote Illustrator: Jay Hambridge Release Date: August 14, 2006 [EBook #19041] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BLISTER JONES *** Produced by Al Haines

I dedicate this, my first book, with awe and

the deepest affection, to Mulvaney—Mowgil—Kim,

and all the wonderful rest of them.

J. T. F.

A certain magazine, that shall be nameless, I read every month. Not because its pale contents, largely furnished by worthy ladies, contain many red corpuscles, but because as a child I saw its numbers lying upon the table in the "library," as much a part of that table as the big vase lamp that glowed above it.

My father and mother read the magazine with much enjoyment, for, doubtless, when its editor was young, the precious prose and poetry of Araminta Perkins and her ilk satisfied him not at all.

Therefore, in memory of days that will never come again, I read this old favorite; sometimes—I must confess it—with pain.

It chanced that a story about horses—aye, race horses—was approved and sanctified by the august editor.

This story, when I found it sandwiched between Jane Somebody's Impressions Upon Seeing an Italian Hedge, and three verses entitled Resurgam, or something like that, I straightway bore to "Blister" Jones, horse-trainer by profession and gentleman by instinct.

"What that guy don't know about a hoss would fill a book," was his comment after I had read him the story.

I rather agreed with this opinion and so—here is the book.

THE THOROUGHBRED

Lead him away!--his day is done,

His satin coat and velvet eye

Are dimmed as moonlight in the sun

Is lost upon the sky.

Lead him away!--his rival stands

A calf of shiny gold;

His masters kneel with lifted hands

To this base thing and bold.

Lead him away!--far down the past,

Where sentiment has fled;

But, gentlemen, just at the last,

Drink deep!--_the thoroughbred_!

| I | Blister |

| II | Two Ringers |

| III | Wanted--a Rainbow |

| IV | Salvation |

| V | A Tip in Time |

| VI | Très Jolie |

| VII | Ole Man Sanford |

| VIII | Class |

| IX | Exit Butsy |

| X | The Big Train |

How my old-young friend "Blister" Jones acquired his remarkable nickname, I learned one cloudless morning late in June.

Our chairs were tipped against number 84 in the curving line of box-stalls at Latonia. Down the sweep of whitewashed stalls the upper doors were yawning wide, and from many of these openings, velvet black in the sunlight, sleek snaky heads protruded.

My head rested in the center of the lower door of 84. From time to time a warm moist breath, accompanied by a gigantic sigh, would play against the back of my neck; or my hat would be pushed a bit farther over my eyes by a wrinkling muzzle—for Tambourine, gazing out into the green of the center-field, felt a vague longing and wished to tell me about it.

The track, a broad tawny ribbon with a lace-work edging of white fence, was before us; the "upper-turn" with its striped five-eighths pole, not fifty feet away. Some men came and set up the starting device at this red and white pole, and I asked Blister to explain to me just what it meant.

"Goin' to school two-year-olds at the barrier," he explained. And presently—mincing, sidling, making futile leaps to get away, the boys on their backs standing clear above them in the short stirrups—a band of deer-like young thoroughbreds assembled, thirty feet or so from the barrier.

Then there was trouble. Those sweet young things performed, with the rapidity of thought, every lawless act known to the equine brain. They reared. They plunged. They bucked. They spun. They surged together. They scattered like startled quail. I heard squeals, and saw vicious shiny hoofs lash out in every direction; and the dust spun a yellow haze over it all.

"Those jockeys will be killed!" I gasped.

"Jockeys!" exclaimed Blister contemptuously. "Them ain't jockeys—they're exercise-boys. Do you think a jock would school a two-year-old?"

A man, who Blister said was a trainer, stood on the fence and acted as starter. Language came from this person in volcanic blasts, and the seething mass, where infant education was brewing, boiled and boiled again.

"That bay filly's a nice-lookin' trick, Four Eyes!" said Blister, pointing out a two-year-old standing somewhat apart from the rest. "She's by Hamilton 'n' her dam's Alberta, by Seminole."

The bay filly, I soon observed, had more than beauty—she was so obviously the outcome of a splendid and selected ancestry. Even her manners were aristocratic. She faced the barrier with quiet dignity and took no part in the whirling riot except to move disdainfully aside when it threatened to engulf her. I turned to Blister and found him gazing at the filly with a far-away look in his eyes.

"Ole Alberta was a grand mare," he said presently. "I see her get away last in the Crescent City Derby 'n' be ten len'ths back at the quarter. But she come from nowhere, collared ole Stonebrook in the stretch, looked him in the eye the last eighth 'n' outgamed him at the wire. She has a hundred 'n' thirty pounds up at that.

"Ole Alberta dies when she has this filly," he went on after a pause. "Judge Dillon, over near Lexington, owned her, 'n' Mrs. Dillon brings the filly up on the bottle. See how nice that filly stands? Handled every day since she was foaled, 'n' never had a cross word. Sugar every mawnin' from Mrs. Dillon. That's way to learn a colt somethin'."

At last the colts were formed into a disorderly line.

"Now, boys, you've got a chance—come on with 'em!" bellowed the starter. "Not too fast …" he cautioned. "Awl-r-r-right … let 'em go-o-!"

They were off like rockets as the barrier shot up, and the bay filly flashed into the lead. Her slender legs seemed to bear her as though on the breast of the wind. She did not run—she floated—yet the gap between herself and her struggling schoolmates grew ever wider.

"Oh, you Alberta!" breathed Blister. Then his tone changed. "Most of these wise Ikes talk about the sire of a colt, but I'll take a good dam all the time for mine!"

Standing on my chair, I watched the colts finish their run, the filly well in front.

"She's a wonder!" I exclaimed, resuming my seat.

"She acts like she'll deliver the goods," Blister conceded. "She's got a lot of step, but it takes more'n that to make a race hoss. We'll know about her when she goes the route, carryin' weight against class."

The colts were now being led to their quarters by stable-boys. When the boy leading the winner passed, he threw us a triumphant smile.

"I guess she's bad!" he opined.

"Some baby," Blister admitted. Then with disgust: "They've hung a fierce name on her though."

"Ain't it the truth!" agreed the boy.

"What is her name?" I asked, when the pair had gone by.

"They call her Trez Jolly," said Blister. "Now, ain't that a hell of a name? I like a name you can kind-a warble." He had pronounced the French phrase exactly as it is written, with an effort at the "J" following the sibilant.

"Très Jolie—it's French," I explained, and gave him the meaning and proper pronunciation.

"Traysyolee!" he repeated after me. "Say, I'm a rube right. Tra-aysyole-e in the stretch byano-o-se!" he intoned with gusto. "You can warble that!" he exclaimed.

"I don't think much of Blister—for beauty," I said. "Of course, that isn't your real name."

"No; I had another once," he replied evasively. "But I never hears it much. The old woman calls me 'thatdambrat,' 'n' the old man the same, only more so. I gets Blister handed to me by the bunch one winter at the New Awlin' meetin'."

"How?" I inquired.

"Wait till I get the makin's 'n' I'll tell you," he said, as he got up and entered a stall.

"One winter I'm swipin' fur Jameson," he began, when he returned with tobacco and papers. "We ships to New Awlins early that fall. We have twelve dogs—half of 'em hop-heads 'n' the other half dinks.

"In them days I ain't much bigger 'n a peanut, but I sure thinks I'm a clever guy. I figger they ain't a gazabo on the track can hand it to me.

"One mawnin' there's a bunch of us ginnies settin' on the fence at the wire, watchin' the work-outs. Some trainers 'n' owners is standin' on the track rag-chewin'.

"A bird owned by Cal Davis is finishin' a mile-'n'-a-quarter, under wraps, in scan'lous fast time. Cal is standin' at the finish with his clock in his hand lookin' real contented. All of a sudden the bird makes a stagger, goes to his knees 'n' chucks the boy over his head. His swipe runs out 'n' grabs the bird 'n' leads him in a-limpin'.

"Say! That bird's right-front tendon is bowed like a barrel stave!

"This Cal Davis is a big owner. He's got all kinds of kale—'n' he don't fool with dinks. He gives one look at the bowed tendon.

"'Anybody that'll lead this hoss off the track, gets him 'n' a month's feed,' he says.

"Before you could spit I has that bird by the head. His swipe ain't goin' to let go of him, but Cal says: 'Turn him loose, boy!' 'N' I'm on my way with the bird.

"That's the first one I ever owns. Jameson loans me a stall fur him. That night a ginnie comes over from Cal's barn with two bags of oats in a wheelbarrow.

"A newspaper guy finds out about the deal, 'n' writes it up so everybody is hep to me playin' owner. One day I see the starter point me out to Colonel King, who's the main squeeze in the judge's stand, 'n' they both laugh.

"I've got all winter before we has to ship, 'n' believe me I sweat some over this bird. I done everythin' to that tendon, except make a new one. In a month I has it in such shape he don't limp, 'n' I begins to stick mile gallops 'n' short breezers into him. He has to wear a stiff bandage on the dinky leg, 'n' I puts one on the left-fore, too—it looks better.

"It ain't so long till I has this bird cherry ripe. He'll take a-holt awful strong right at the end of a stiff mile. One day I turns him loose, fur three-eighths, 'n' he runs it so fast he makes me dizzy.

"I know he's good, but I wants to know how good, before I pays entrance on him. I don't want the clockers to get wise to him, neither!

"Joe Nickel's the star jock that year. I've seen many a good boy on a hoss, but I think Joe's the best judge of pace I ever see. One day he's comin' from the weighin'-room, still in his silks. His valet's with him carryin' the saddle. I steps up 'n' says:

"'Kin I see you private a minute, Joe?'

"'Sure thing, kid,' he says. 'N' the valet skidoos.

"'Joe,' I says, 'I've got a bird that's right. I don't know just how good he is, but he's awful good. I want to get wise to him before I crowds my dough on to the 'Sociation. Will you give him a work?'

"It takes an awful nerve to ask a jock like Nickel to work a hoss out, but he's the only one can judge pace good enough to put me wise, 'n' I'm desperate.

"'It's that Davis cripple, ain't it?' he asks.

"'That's him,' I says.

"He studies a minute, lookin' steady at me.

"'I'm your huckleberry,' he says at last. 'When do you want me?'

"'Just as she gets light to-morrow mawnin',' I says quick, fur I hasn't believed he'd come through, 'n' I wants to stick the gaff into him 'fore he changes his mind.

"He give a sigh. I knowed he was no early riser.

"'All right,' he says. 'Where'll you be?'

"'At the half-mile post,' I says. 'I'll have him warmed up fur you.'

"'All right,' he says again—'n' that night I don't sleep none.

"When it begins to get a little gray next mawnin' I takes the bird out 'n' gallops him a slow mile with a stiff breezer at the end. But durin' the night I gives up thinkin' Joe'll be there, 'n' I nearly falls off when I comes past the half-mile post, 'n' he's standin' by the fence in a classy overcoat 'n' kid gloves.

"He takes off his overcoat, 'n' comes up when I gets down,'n' gives a look at the saddle.

"'I can't ride nothin' on that thing,' he says. 'Slip over to the jocks' room 'n' get mine. It's on number three peg—here's the key.'

"It's gettin' light fast 'n' I'm afraid of the clockers.

"'The sharp-shooters'll be out in a minute,' I says.

"'I can't help it,' says Joe. 'I wouldn't ride a bull on that saddle!'

"I see there's no use to argue, so I beats it across the center-field, cops the saddle 'n' comes back. I run all the way, but it's gettin' awful light.

"'Send him a mile in forty-five 'n' see what he's got left,' I says, as I throws Joe up.

"'Right in the notch—if he's got the step,' he says.

"I click Jameson's clock on them, as they went away—Joe whisperin' in the bird's ear. The back-stretch was the stretch, startin' from the half. I seen the bird's mouth wide open as they come home, 'n' Joe has double wraps on him. 'He won't beat fifty under that pull!' I says to myself. But when I stops the clock at the finish it was at forty-four-'n'-three-quarters. Joe ain't got a clock to go by neither—that's judgin' pace!—take it from me!

"'He's diseased with speed,' says Joe, when he gets down. 'He can do thirty-eight sure—just look at my hands!'

"I does a dance a-bowin' to the bird, 'n' Joe stands there laughin' at me, squeezin' the blood back into his mitts.

"We leads the hoss to the gate, 'n' there's a booky's clocker named Izzy Goldberg.

"'You an exercise-boy now?' he asks Joe.

"'Not yet,' says Joe. 'Mu cousin here owns this trick, 'n' I'm givin' him a work.'

"'Up kind-a early, ain't you? Say! He's good, ain't he, Joe?' says Izzy; 'n' looks at the bird close.

"'Naw, he's a mutt,' says Joe.

"'What's he doin' with his mouth open at the end of that mile?' Izzy says, 'n' laughs.

"'He only runs it in fifty,' says Joe, careless. 'I takes hold of him 'cause he's bad in front, 'n' he's likely to do a flop when he gets tired. So long, Bud!' Joe says to me, 'n' I takes the bird to the barn.

"I'm not thinkin' Izzy ain't wise. It's a cinch Joe don't stall him. Every booky would hear about that work-out by noon. Sure enough the Item's pink sheet has this among the tips the next day:

"'Count Noble'—that was the bird's name—'a mile in forty-four. Pulled to a walk at the end. Bet the works on him; his first time out, boys!'

"That was on a Saturday. On Monday I enters the bird among a bunch of dogs to start in a five furlong sprint Thursday. I'm savin' every soomarkee I gets my hands on 'n' I pays the entrance to the secretary like it's a mere bag of shells. Joe Nickel can't ride fur me—he's under contract. I meets him the day before my race.

"'You're levelin' with your hoss, ain't you?' he says. 'I'll send my valet in with you, 'n' after you get yours on, he'll bet two hundred fur me.'

"'Nothin' doin', Joe!' I says. 'Stay away from it. I'll tell you when I gets ready to level. You can't bet them bookies nothin'—they're wise to him.'

"'Look-a-here, Bud!' says Joe. 'That bird'll cake-walk among them crabs. No jock can make him lose, 'n' not get ruled off.'

"'Leave that to me,' I says.

"Just as I figgers—my hoss opens up eight-to-five in the books.

"I gives him all the water he'll drink afore he goes to the post, 'n' I has bandages on every leg. The paddock judge looks at them bandages, but he knows the bird's a cripple, 'n' he don't feel 'em.

"'Them's to hold his legs on, ain't they?' he says, 'n' grins.

"'Surest thing you know,' I says. But I feels some easier when he's on his way—there's seven pounds of lead in each of them bandages.

"I don't want the bird whipped when he ain't got a chance.

"'This hoss backs up if you use the bat on him,' I says to the jock, as he's tyin' his reins.

"'He backs up anyway, I guess,' he says, as the parade starts.

"The bird gets away good, but I'd overdone the lead in his socks. He finished a nasty last—thirty len'ths back.

"'Roll over, kid!' says the jock, when I go up to slip him his fee. 'Not fur ridin' that hippo. It 'ud be buglary—he couldn't beat a piano!'

"I meets Colonel King comin' out of the judge's stand that evenin'.

"'An owner's life has its trials and tribulations—eh, my boy?' he says.

"'Yes, sir!' I says. That's the first time Colonel King ever speaks to me, 'n' I swells up like a toad. 'I'm gettin' to be all the gravy 'round here,' I says to myself.

"Two days after this they puts an overnight mile run fur maidens on the card, 'n' I slips the bird into it. I knowed it was takin' a chance so soon after his bad race, but it looks so soft I can't stay 'way from it. I goes to Cal Davis, 'n' tells him to put a bet down.

"'Oh, ho!' he says. 'Lendin' me a helpin' hand, are you?' Then I tells him about Nickel.

"'Did Joe Nickel work him out for you?' he says. 'The best is good enough fur you, ain't it? I'll see Joe, 'n' if it looks good to him I'll take a shot at it. Much obliged to you.'

"'Don't never mention it,' I says.

"'How do you mean that?' he says, grinnin'.

"'Both ways,' says I.

"The mawnin' of the race, I'm givin' the bird's bad leg a steamin', when a black swipe named Duckfoot Johnson tells me I'm wanted on the phone over to the secretary's office, 'n' I gets Duckfoot to go on steamin' the leg while I'm gone.

"It's a feed man on the phone, wantin' to know when he gets sixteen bucks I owe him.

"'The bird'll bring home your coin at four o'clock this afternoon,' I tells him.

"'Well, that's lucky,' he says. 'I thought it was throwed to the birds, 'n' I didn't figure they'd bring it home again.'

"When I gets back there's a crap game goin' on in front of the stall, 'n' Duckfoot's shootin'. There's a hot towel on the bird's leg, 'n' it's been there too long. I takes it off 'n' feel where small blisters has begun to raise under the hair—a little more 'n' it 'ud been clear to the bone. I cusses Duckfoot good, 'n' rubs vaseline into the leg."

I interrupted Blister long enough to inquire:

"Don't they blister horses sometimes to cure them of lameness?"

"Sure," he replied. "But a hoss don't work none fur quite a spell afterwards. A blister, to do any good, fixes him so he can't hardly raise his leg fur two weeks.

"Well," he went on, "the race fur maidens was the last thing on the card. I'm in the betting-ring when they chalks up the first odds, 'n' my hoss opens at twenty-five-to-one. The two entrance moneys have about cleaned me. I'm only twenty green men strong. I peels off ten of 'em 'n' shoved up to a booky.

"'On the nose fur that one,' I says, pointin' to the bird's name.

"'Quit your kiddin',' he says. 'What 'ud you do with all that money? This fur yours.' 'N' he rubs to twelve-to-one.

"'Ain't you the liberal gink?' I says, as he hands me the ticket.

"'I starts fur the next book, but say!—the odds is just meltin' away. Joe's 'n' Cal's dough is comin' down the line, 'n' the gazabos, thinkin' it's wise money, trails. By post-time the bird's a one-to-three shot.

"I've give the mount to Sweeney, 'n' like a nut I puts him hep to the bird, 'n' he tells his valet to bet a hundred fur him. The bird has on socks again, but this time they're empty, 'n' the race was a joke. He breaks fifth at the get-away, but he just mows them dogs down. Sweeney keeps thinkin' about that hundred, I guess, 'cause he rode the bird all the way, 'n' finished a million len'ths in front.

"I cashes my ticket, 'n' starts fur the barn to sleep with that bird, when here comes Joe Nickel.

"'He run a nice race,' he says, grinnin', 'n' hands me six hundred bucks.

"What's this fur?' I says. 'You better be careful … I got a weak heart.'

"'I win twelve hundred to the race,' he says. ''N' we splits it two ways.'

"'Nothin' doin',' I says, 'n' tries to hand him back the wad.

"'Go awn!' he says, 'I'll give you a soak in the ear. I bet that money fur you, kiddo.'

"I looks at the roll 'n' gets wobbly in the knees. I never see so much kale before—not at one time. Just then we hears the announcer sing out through a megaphone:

"'The o-o-owner of Count Nobul-l-l-l is wanted in the judge's stand!'

"'Oy, oy!' says Joe. 'You'll need that kale—you're goin' to lose your happy home. It's Katy bar the door fur yours, Bud!'

"'Don't worry—watch me tell it to 'em,' I says to Joe, as I stuffs the roll 'n' starts fur the stand. I was feelin' purty good.

"'Wait a minute,' says Joe, runnin' after me. 'You can't tell them people nothin'. You ain't wise to that bunch yet. Bud—why, they'll kid you silly before they hand it to you, 'n' then change the subject to somethin' interestin', like where to get pompono cooked to suit 'em. I've been up against it,' he says, ''n' I'm tellin' you right. Just keep stallin' around when you get in the stand, 'n' act like you don't know the war's over.'

"'Furget it,' I says. 'I'll show those big stiffs where to head in. I'll hypnotize the old owls. I'll give 'em a song 'n' dance that's right!'

"As I goes up the steps I see the judges settin' in their chairs, 'n' I takes off my hat. Colonel King ain't settin', he's standin' up with his hands in his pockets. Somehow, when I sees him I begins to wilt—he looks so clean. He's got a white mustache, 'n' his face is kind-a brown 'n' pink. He looks at me a minute out of them blue eyes of his.

"'Are you the owner of Count Noble, Mr.—er—?'

"'Jones, sir,' I says.

"'Jones?' says the colonel.

"'Yes, sir,' I says.

"'Mr. Jones,' says the colonel, 'how do you account for the fact that on Thursday Count Noble performs disgracefully, and on Saturday runs like a stake horse? Have the days of the week anything to do with it?'

"I never says nothin'. I just stands there lookin' at him, foolin' with my hat.

"'This is hell," I thinks.

"'The judges are interested in this phenomenon, Mr. Jones, and we have sent for you, thinking perhaps you can throw a little light on the matter,' says the colonel, 'n' waits fur me again.

"'Come on … get busy!' I says to myself. 'You can kid along with a bunch of bums, 'n' it sounds good—don't get cold feet the first time some class opens his bazoo at you!' But I can't make a noise like a word, on a bet.

"'The judges, upon looking over the betting sheets of the two races in which your horse appeared, find them quite interesting,' says the colonel. 'The odds were short in the race he did not win; they remained unchanged—in fact, rose—since only a small amount was wagered on his chances. On the other hand, these facts are reversed in to-day's race, which he won. It seems possible that you and your friends who were pessimists on Thursday became optimists today, and benefited by the change. Have you done so?'

"I see I has to get some sort-a language out of me.

"'He was a better hoss to-day—that's all I knows about it,' I says.

"'The first part of your statement seems well within the facts,' says the colonel. 'He was, apparently, a much better horse to-day. But these gentlemen and myself, having the welfare of the American thoroughbred at heart, would be glad to learn by what method he was so greatly improved.'

"I don't know why I ever does it, but it comes to me how Duckfoot leaves the towel on the bird's leg, 'n' I don't stop to think.

"'I blistered him,' I says.

"'You—what?' says the colonel. I'd have give up the roll quick, sooner'n spit it out again, but I'm up against it.

"'I blisters him', I says.

"The colonel's face gets red. His eyes bung out 'n' he turns 'round 'n' starts to cough 'n' make noises. The rest of them judges does the same. They holds on to each other 'n' does it. I know they're givin' me the laugh fur that fierce break I makes.

"'You're outclassed, kid!' I says to myself. 'They'll tie a can to you, sure. The gate fur yours!'

"Just then Colonel King turns round, 'n' I see I can't look at him no more. I looks at my hat, waitin' fur him to say I'm ruled off. I've got a lump in my throat, 'n' I think it's a bunch of bright conversation stuck there. But just then a chunk of water rolls out of my eye, 'n' hits my hat—pow! It looks bigger'n Lake Erie, 'n' 'fore I kin jerk the hat away—pow!—comes another one. I knows the colonel sees 'em, 'n' I hopes I croak.

"'Ahem—', he says.

"'Now I get mine!' I says to myself.

"'Mr. Jones,' says the colonel, 'n' his voice is kind-a cheerful. 'The judges will accept your explanation. You may go if you wish.'"

Just as I'm goin' down the steps the colonel stops me.

"'I have a piece of advice for you, Mr. Jones,' he says. His voice ain't cheerful neither. It goes right into my gizzard. I turns and looks at him. 'Keep that horse blistered from now on!' says the colonel.

"Some ginnies is in the weighin'-room under the stand, 'n' hears it all. That's how I gets my name."

"Hello, ole Four Eyes!" was the semi-affectionate greeting of Blister Jones. "I ain't seed you lately."

I had found him in the blacksmith shop at Latonia, lazily observing the smith's efforts to unite Fan Tan and a set of new-made, blue-black racing-plates. I explained how a city editor had bowed my shoulders with the labors of Hercules during the last week, and began to acquire knowledge of the uncertainties connected with shoeing a young thoroughbred.

A colored stable-boy stood at Fan Tan's wicked-looking head and addressed in varied tone and temper a pair of flattened ears.

"Whoa! Baby-doll! Dat's ma honey—dat's ma petty chile— … Whoa! Yuh no-'coun' houn', yuh!" The first of the speech had been delivered soothingly, as the smith succeeded in getting a reluctant hind leg into his lap; the last was snorted out as the leg straightened suddenly and catapulted him into a corner of the shop, where he sat down heavily among some discarded horseshoes.

The smith arose, sweat and curses dripping from him.

"Chris!" said Blister, "it's a shame the way you treat that pore filly. She comes into yer dirty joint like a little lady, fur to get a new pair of shoes, 'n' you grabs her by the leg 'n' then cusses her when she won't stand fur it."

Part of the curses were now directed at Blister.

"Come on, Four Eyes," he said. "This ain't no place fur a minister's son."

"I'd like to stay and see the shoeing!" I protested, as he rose to go.

"What shoeing?" he asked incredulously. "You ain't meanin' a big strong guy like Chris manhandlin' a pore little filly? Come awn—I can't stand to see him abusin' her no more."

We wandered down to the big brown oval, and Blister, perching himself on the top rail of the fence, took out his stop-watch, although there were no horses on the track.

"What are you going to do with that?" I asked.

"Got to do it," he grinned. "If I was to set on a track fence without ma clock in my mitt, I'd get so nur-r-vous! Purty soon I'd be as fidgity as that filly back there. Feelin' this ole click-click kind-a soothes my fevered brow."

In a silence that followed I watched a whipped-cream cloud adrift on the deepest of deep blue skies.

"Hi, hum!" said Blister presently, and extending his arms in a pretense of stretching, he shoved me off the fence. "You're welcome," he said to my protests, and added: "There's a nice matched pair."

A boy, leading a horse, was emerging from the mouth of a stall.

The contrast between them was startling—never had I seen a horse with so much elegant apparel; rarely had I seen a boy with so little. The boy, followed by the horse, began to walk a slow circle not far from where we sat. Suddenly the boy addressed Blister.

"Say, loan me the makin's, will you, pal?" he drawled.

From his hip pocket Blister produced some tobacco in a stained muslin bag and a wad of crumpled cigarette papers. These he tossed toward the boy.

"Yours trooly," muttered that worthy, as he picked up the "makin's". "Heard the news about Hicky Rogers?" he asked, while he rolled a cigarette.

"Nothin', except he's a crooked little snipe," Blister answered.

"Huh! that ain't news," said the boy. "They've ruled him off—that's what I mean."

"That don't surprise me none," Blister stated. "He's been gettin' too smart around here fur quite a while. It'll be a good riddance."

"Were you ever ruled off the track?" I asked Blister, as the boy, exhaling clouds of cigarette smoke, returned to the slow walking of his horse. He studied in silence a moment.

"Yep—once," he replied. "I got mine at New Awlins fur ringin' a hoss. That little ole town has got my goat."

"When was this?" I asked.'

"The year I first starts conditionin' hosses," he answered.

I had noticed that dates totally eluded Blister. A past occurrence as far as its relation to time was concerned, he always established by a contemporary event of the turf. Pressed as to when a thing had taken place he would say, "The year Salvation cops all the colt stakes," or "The fall Whisk-broom wins the Brooklyn Handicap." This had interested me and I now tried to get something more definite from him. He answered my questions vaguely.

"Say, if you're lookin' fur that kind of info," he said at last, "get the almanac or the byciclopedia. These year things slide by so easy I don't get a good pike at one, 'fore another is not more'n a len'th back, 'n' comin' fast."

I saw it was useless.

"Well, never mind just when it happened," I said. "Tell me about it."

"All right," said Blister. "Like I've just said it happens one winter at New Awlins, the year after I starts conditionin' hosses.

"Things break bad fur me that winter. Whenever a piker can't win a bet he comes 'round, slaps me on the wrist, 'n' separates me from some of my kale. I'm so easy I squeezes my roll if I meets a child on the street. The cops had ought to patrol me, 'cause larceny'll sure be committed every time a live guy speaks to me.

"I've only got three dogs in my string. One of 'em's a mornin'-glory. He'll bust away as if he's out to make Salvator look like a truck-hoss, but he'll lay down 'n' holler fur some one to come 'n' carry him when he hits the stretch. One's a hop-head 'n' I has to shoot enough dope into him to make him think he's Napoleon Bonyparte 'fore he'll switch a fly off hisself. Then when he sees how far away the wire is he thinks about the battle of Waterloo 'n' says, 'Take me to Elby.'

"I've got one purty fair sort of a hoss. He's just about ready to spill the beans, fur some odds-on, when he gets cast in the stall 'n' throws his stifle out. The vet. gets his stifle back in place.

"'This hoss must have a year's complete rest,' he says.

"'Yes, Doc,' I says. ''N' when he gets so he can stand it, how'd a trip to Europe do fur him?'

"Things go along like this till I'm busted right. No, I ain't busted—I'm past that. I owes the woman where I eats, I owes the feed man, I owes the plater, 'n' I owes every gink that'll stand fur a touch.

"One day a messenger boy comes 'n' leans against the stall door 'n' pokes a yellow envelope at me.

"'Well, Pierpont,' I says, 'what's the good word?'

"'Sign here. Two bits,' he says, yawnin'.

"I sees where it says 'charges paid,' 'n' I takes him by the back of the neck 'n' he gets away to a flyin' start fur the gate. The message is from Buck Harms.

"'Am at the St Charles, meet me nine a. m. to-morrow,' it says.

"This Harms duck is named right, 'cause that's what he does to every guy he meets. He's so crooked he can sleep on a corkscrew. When there ain't nobody else around he'll take money out of one pocket 'n' put it in another. He's been ruled off twict 'n' there's no chance fur him to get back. I wouldn't stand fur him only I'm in so bad I has to do somethin'.

"'If he takes any coin from me he'll have to be Hermann,' I says to myself, 'n' I shows up at the hotel the next mawnin'.

"Harms is settin' in the lobby readin' the dope-sheet. I pipes him off 'n' he don't look good to me fur a minute, but I goes over 'n' shakes his mitt.

"'Well, Blister, old scout, how're they breakin'?' he says.

"'So, so,' I says.

"'That right?' he says. 'I hears different. Fishhead Peters tells me they've got you on the ropes.'

"'What th' hell does that gassy Fishhead know about me?' I says.

"'Cut out the stallin',' he says. 'It don't go between friends. Would you like to git a-holt of a new roll?'

"'I don't mind tellin' you that sooner 'n have my clothes tore I lets somebody crowd a bundle of kale on to me,' I says.

"'That sounds better,' he says. 'Come on—we'll take a cab ride.'

"'Where we goin'?' I asks him, as we gets into a cab.

"'Goin' to look at a hoss,' he says.

"'What fur?' I says.

"'Wait till we git there 'n' I'll tell you,' he says.

"We rides fur about a hour 'n' pulls up at a barn out in the edge of town. We goes inside 'n' there's a big sorrel geldin', with a blaize face, in a box-stall.

"'Look him over,' says Harms. I gets one pike at the hoss—

"'Why! it's ole Friendless!' I says.

"'Look close,' he says. 'Wait till I get him outside.'

"I looks the hoss over careful when he's outside in the light, 'n' I don't know what to think. First I think it's Friendless 'n' then I think maybe it ain't.

"'If it ain't Friendless, it's his double!' I says at last. 'But I think Friendless has a white forefoot.'

"'Well, it ain't Friendless,' says Harms as he leads the hoss into the barn. 'And you're right about the white foot.'

"Now, Friendless is a bird that ain't started fur a year. Harms or some of his gang used to own him, 'n' believe me, he can ramble some if everythin' 's done to suit him. He's a funny hoss, 'n' has notions. If a jock'll set still 'n' not make a move on him, Friendless runs a grand race. But if a boy takes holt of him or hits him with the bat, ole Friendless says, 'Nothin' doin' to-day!' 'n' sulks all the way. He'd have made a great stake hoss only he's dead wise to how much weight he's packin'. He'll romp with anythin' up to a hundred 'n' ten, but not a pound over that can you slip him. Looks like he says to hisself, 'They must think I'm a movin' van,' 'n' he lays his ole ears back, 'n' dynamite won't make him finish better'n fourth. This little habit of his'n spoils him 'cause he's too good, 'n' the best he gets from a handicapper is a hundred 'n' eighteen—that kind of weight lets him out.

"Goin' back in the cab Harms tells me why he sends fur me. This dog he's just showed me 's named Alcyfras. He's been runnin' out on the coast 'n' he's a mutt—he can't beat a fat man. Harms sees him one day at Oakland, 'n' has a guy buy him.

"Harms brings this pup back East. He has his papers 'n' description all regular. The guy that buys him ain't wise—he's just a boob Harms is stallin' with. What he wants me to do is to take the hoss in my string, get him identified 'n' start him a couple of times; then when the odds is real juicy I'm to start Friendless under the dog's name 'n' Harms 'n' his gang'll bet him to a whisper at the poolrooms in Chicago 'n' New York.

"'Where's Friendless now?' I asks him.

"'They're gettin' him ready on a bull-ring up in Illinois,' says Harms. 'He's in good shape 'n' 'll be dead ripe time we get ready to ship him down here. I figure we'll put this gag across about Christmas.'

"'What does the boy wonder get fur swappin' mules with the Association?' I says. 'I'm just dyin' to know what Santa Claus'll bring little Alfred.'

"'You get all expenses, twenty-five bucks a week, 'n' a nice slice of the velvet when we cleans up,' says Harms.

"'Nix, on that noise!' says I. 'If you or some other benevolent gink don't crowd five hundred iron dollars on G. Percival the day before the bird flies, he won't leave the perch.'

"'Don't you trust me?' says Harms.

"'Sure,' I says, 'better'n Cassie Chadwick.'

"He argues, but it don't get him nothin' so he says he'll come across the day before Friendless brings home the bacon, 'n' I make him cough enough to pay what I owes. The next day a swipe leads Alcyfras out to the track.

"'What's the name of that dog?' Peewee Simpson yells, as I'm cross-tyin' the hoss at the stall door.

"'Alcyfras,' I says, as I pulls the blanket off. Peewee comes over 'n' looks at the hoss a minute.

"'Alcy nothin'!' he says. 'If that ain't Friendless, I never sees him.'

"I digs up the roll Harms give me.

"I'll gamble this pinch of spinach his name is Alcyfras,' I says.

"'You kin name what you like far as I'm concerned, 'n' change it every mawnin' before breakfast,' says Peewee. 'But if you starts him as anythin' but Friendless we don't see your freckled face 'round here no more.'

"By this time a bunch has gathered 'n' soon there's a swell argument on. One guy'll say it's Friendless 'n' another 'll say it ain't. Finally somebody says to send fur Duckfoot Johnson, who swiped Friendless fur two years. They send for him.

"When Duckfoot comes he busts through the crowd like he's the paddock judge.

"'Lemme look at dis hoss,' he says.

"Everybody draws back 'n' Duckfoot looks the hoss over 'n' then runs his hand under his barrel close to the front legs.

"'No, sah, dis ain' Frien'less,' he says. 'Frien'less has a white foot on de off front laig and besides dat he has a rough-feeling scab on de belly whar he done rip hisself somehow befo' I gits him. Dis dawg am smooth as a possum.'

"That settles all arguments. You can't fool a swipe 'bout a hoss he's taken care of. He knows every hair on him.

"One day I'm clockin' this Alcyfras while a exercise-boy sends him seven-eights. When I looks at my clock I thinks they ought to lay a thousand-to-one against the mutt, after he starts a couple of times. Just then somethin' comes 'n' stands in front of me 'n' begins to make little squeaky noises.

"'Are you Mr. Blister?' it says.

"I bats my eyes 'n' nods.

"'I've got 'em again,' I thinks.

"'Oh, what a relief!' it squeaks. 'I just thought I'd never find you. I've been looking all over the race course for you!'

"'Gracious! Ferdy, you've had a awful time, ain't you?' I says. 'If you want to stay out of trouble, read your Ladies' Home Journal more careful.'

"'My name is Alcibides Tuttle,' says pink toes, drawin' hisself up. 'And I am the owner of the horse called Alcyfras. I purchased this animal upon the advice of my friend, Mr. Harms, whom I met in San Francisco.'

"Say! I've worked fur some nutty owners, but this yap's the limit.

"'Well, Alci, here comes Alcy now,' I says, as the boy comes up with the dog, 'n' my new boss stretches his number three neck out of his number nine collar 'n' blinks at the hoss.

"Alcibides comes back to the stall with me 'n' from then on he sticks to me tighter 'n a woodtick. He's out to the track every mawnin' by nine 'n' he don't leave till after the races. He asks me eighty-seven squeaky questions a minute all the time we're together. I calls him 'n' his hoss both Alcy fur a while, but I changes him to Elsy—that was less confusin' 'n' it suits him better.

"The next week I starts Alcyfras among a bunch of crabs in a seven furlong sellin' race, 'n' the judges hold up his entrance till I can identify him. I hands them his papers 'n' they looks up the description of Friendless in the stud-book, where it shows he's got one white foot. Then they wire to the breeder of Alcyfras 'n' to the tracks in California where the dog has started. The answers come back all proper 'n' to cinch it I produce Elsy as owner. They look Elsy over while he tells 'em he's bought the hoss.

"'Gentlemen,' says Colonel King to the other judges, 'the mere sight of Mr. Tuttle has inspired me with full confidence in his entry and himself.' He bows to Elsy 'n' Elsy bows to him. The rest of the judges turn 'round 'n' look at somethin' over across the center-field.

"I tells Elsy his hoss is all to the merry, but we don't want him to win till the odds get right. He's standin' beside me at the race, 'n' Alcyfras runs next to last.

"'Of course, I realize you are more familiar with horse racing than myself,' he says; 'but I think you should have allowed him to do a little better. What method did you employ to make him remain so far in the rear?'

"'I tells the jock to pull him,' I says. The boy was usin' the bat half the trip, but Elsy never tumbles.

"'What do you say to a jockey when you desire him to lose?' Elsy asks me.

"'I just say—"Grab this one,"' I says.

"'What do you say when you require him to win?' he squeaks.

"'I don't say nothin'. I hands him a ticket on the hoss 'n' the jock wins if he has to get down 'n' carry the dog home,' I says.

"Not long after this, Friendless gets in from Illinois. I look him over in the car 'n' I see he's not ready. He's not near ready.

"'What kind of shoemakers give this hoss his prep.?' I asks Harms.

"'What's wrong with him?' he says. 'He looks good to me.'

"'He ain't ready,' I says. 'Look at him 'n' feel him! He'll need ten days more work 'n' a race under his belt 'fore he's safe to bet real money on.'

"Harms buys some stuff at a drug store, 'n' gets busy with the white fore-foot.

"'Only God A'mighty can make as good a sorrel as that!' he says when he's through. 'Here's the can of dope. Don't let her fade.'

"'What are you goin' to do about this Elsy person?' I says. 'While I ain't sayin' it's pure joy to have him around, I ain't got the heart to hand it to him. I don't mind trimmin' boobs—that's what they're for—but this Elsy thing is too soft. He must be in quite a wad on this bum hoss of his'n.'

"'Who's Elsy?' says Harms.

"I tells him, 'n' he laughs.

"'Is that what you call him?' he says. 'What's bitin' you—ain't Friendless goin' to win a nice purse for him?'

"About ten o'clock that night Alcyfras goes out one gate 'n' Friendless comes in another. I keeps the foot stained good, 'n' shuts the stall door whenever Duckfoot shows up. In ten days the hoss is right on edge 'n' one race'll put the finish on him, so I enter him, in a bunch of skates, as Alcyfras. I gives the mount to Lou Smith—he ain't much of a jock, but he'll ride to orders. Just before the race I has a heart to heart talk with Lou.

"'Fur this hoss to win you don't make a move on him,' I says. 'If you hand him the bat or take hold of him at the get-away he sulks.'

"'All right, I lets him alone,' says Lou.

"'When I'm ready fur you to let him alone I slips you a nice ticket on this bird. You ain't got a ticket to-day, have you?' I says.

"'Not so's you could notice,' says Lou.

"'Are you hep?' I says.

"'I got-cha, Bo,' says Lou.

"I see Lou's arm rise 'n' fall a couple of times at the start 'n' ole Friendless finished fifth, his ears laid back, sulkier 'n a grass widow at a married men's picnic.

"'You let him do better to-day,' says Elsy. 'Isn't it time to allow him to win?'

"'He wins his next out,' I says.

"I tell Harms we're ready fur the big show 'n' I looks fur a nice race to drop the good thing into. But it starts to rain 'n' it keeps it up a week. Friendless ain't a mudder 'n' we has to have a fast track fur our little act of separating the green stuff from the poolrooms. I'm afraid the bird stales off if I don't get a race into him, so I enters him among a pretty fair bunch of platers, to keep him on edge.

"Three days before the race the weather gets good 'n' the track begins to dry out fast. I see it's goin' to be right fur my race 'n' I meets Harms 'n' tells him to wire his bunch to bet their heads off.

"'I don't like this race,' he says, when he looks at the entries. 'There's two or three live ones in here. This Black-jack ain't such a bad pup, 'n' this here Pandora runs a bang-up race her last out. Let's wait fur somethin' easier.'

"'Well, if you ain't a sure-thing better, I never gets my lamps on one!' I says. 'Don't you want me to saw the legs off the rest of them dogs to earn my five hundred? You must have forgot ole Friendless. He's only got ninety-six pounds up! He'll tin can sure! He kin fall down 'n' roll home faster than them kind of hosses.'

"But Harms won't take a chance, so I goes back to the track 'n' I was sore.

"'That guy's a hot sport, not!' I thinks.

"I hates to tell Elsy the hoss he thinks is his won't win—he'd set his little heart on it so. I don't tell him till the day before the race, 'n' he gets right sassy about it. I never see him so spunky.

"'As owner, I insist that you allow Alcyfras to win this race,' he says, 'n' goes away in a pet when I tells him nix.

"The day of the race I don't see Elsy at all.

"'You ain't got a ticket to-day, 'n' you know the answer,' I says to Lou Smith as the parade starts. He don't say nothin' but nods, so I think he's fixed.

"When I come through the bettin' ring I can't believe my eyes. There's Alcyfras at four-to-one all down the line. He opened at fifty, so somebody has bet their clothes on him.

"'Where does all this play on Alcyfras come from?' I says to a booky.

"'A lost shrimp wanders in here and starts it,' says the booky.

"'What does he look like?' I says.

"'Like a maiden's prayer,' says the booky, 'n' I beats it out to the stand.

"Elsy is at the top of the steps lookin' kind of haughty, 'n' say!—he's got a bundle of tickets a foot thick in his hand.

"'What dead one's name is on all them soovenirs?' I says, pointin' to the tickets.

"'Mr. Blister,' he says, 'after our conversation yesterday I made inquiry concerning the rights of a trainer. I was informed that a trainer, as a paid employee, is under the direction of the owner—his employer. You refused to allow my horse to win, contrary to my wishes. You had no right to do so. I intend that he shall win, and have wagered accordingly—these tickets are on Alcyfras.' He's nervous 'n' fidgity, 'n' his voice is squeakier 'n ever.

"'Well, Mr. Belmont,' I says, 'did you happen to give instructions to any more of your employees, your jockey, fur instance?'

"'I have adopted the method you informed me was the correct one,' he says, swellin' up. 'I gave a ticket at fifty-to-one calling for one hundred and two dollars to Mr. Smith, and explained to him that I was the owner.'

"Before Elsy gets through I'm dopey. I looks over his tickets 'n' he figures to win eight thousand to the race. I have two iron men in my jeans—I don't even go down 'n' bet it.

"'What's the use?' I says to myself.

"I can't hardly see the race, I'm so groggy from the jolt Elsy hands me. Friendless breaks in front and stays there all the way. Lou Smith just sets still 'n' lets the hoss rate hisself. That ole hound comes down the stretch a-rompin', his ears flick-flackin' 'n' a smile on his face. He wins by five len'ths 'n' busts the track record fur the distance a quarter of a second.

"Then it begins to get brisk around there. I figger to have Alcyfras all warmed up outside the fence the day Friendless wins. After the race I'd put him in the stall 'n' send Friendless out the gate. Elsy, practisin' the owner act, has gummed the game—Alcyfras is over in the other end of town.

"Ole Friendless bustin' the track record is the final blow. I don't hardly get to the stall 'fore here comes the paddock judge 'n' his assistant.

"'We want this hoss and you, too, over at the paddock,' he says. 'What's the owner's name?'

"'Alcibides Tuttle,' I says.

"'Is that all?' says the paddock judge. 'Go get him, Billy!' he says to his assistant. 'You'll likely find him cashin' tickets.'

"When we gets to the paddock, there's Colonel King and the rest of the judges.

"'Take his blanket off,' says the colonel, when we leads in the hoss.

"'He's red-hot, Colonel,' I says.

"'So am I,' says the colonel. 'Who was caretaker for the horse Friendless when he was racing?' he asks some of the ginnies.

"'Duckfoot Johnson,' says the whole bunch at once.

"'Send for him,' says the colonel.

"'I's hyar, boss,' says Duckfoot, from the back of the crowd.

"'Come and look this horse over,' says the colonel.

"'I done looked him over befo', boss,' says Duckfoot, when he gets to the colonel.

"'When?' says the colonel. 'When did you see him?'

"''Bout a month ago,' says Duckfoot.

"'Did you recognize him?' says the colonel.

"'Yes, sah,' says Duckfoot, 'I done recnomize him thoully fum his haid to his tail, but I ain' never seed him befo'.'

"'Recnomize him again,' the colonel tells him.

"'Boss,' says Duckfoot, 'some folks 'low dis hoss am Frien'less, but hit ain'. Ef hits Frien'less, an' yo' puts yo' han' hyar on his belly dey is a rough-feelin' scab. Dis hoss am puffeckly smo-o—' then he stops 'n' begins to get ashy 'round the mouth.

"'Well?' says the colonel. 'What's the matter?'

"'Lawd Gawd, boss! Dis am Frien'less … Hyar's de scah!' says Duckfoot, his eyes a-rollin'. Then he goes 'round 'n' looks at the hoss in front. 'Whar his white foot at?' he asks the colonel.

"'That's what we are about to ascertain,' says the colonel. 'Boy,' he says to a ginny, 'run out to the drug store with this dollar and bring me back a pint of benzine and a tooth-brush.'

"The ginny beats it.

"'You may blanket this horse now,' the colonel says to me.

"When the ginny gets back, Colonel King pours the benzine on the tooth-brush 'n' goes to work on the off-forefoot. It ain't long till it's nice 'n' white again.

"'That is most remarkable!' says Elsy, who's watchin' the colonel.

"'In my opinion, Mr. Tuttle,' says the colonel, 'the only remarkable feature of this affair is yourself. I can't get you properly placed. The Association will take charge of this horse until the judges rule.'

"The next day the judges send fur me 'n' Elsy. It don't take Colonel King thirty seconds to rule me off—I don't get back fur two years, neither! Then the colonel looks at Elsy.

"'Mr. Tuttle,' he says, 'if your connection with this business is as innocent as it seems, you should be protected against a further appearance on the turf. On the other hand, if you have acted a part in this little drama, the turf should be protected against you. In either case the judges desire to bring your career as an owner to a close; and we hereby bar you and your entries from all tracks of the Association. This is final and irrevocable.'

"Three years after that I'm at Hot Springs, 'n' I drops into McGlade's place one night to watch 'em gamble. There's a slim guy dealin' faro fur the house, 'n' he's got a green eye-shade on. All of a sudden he looks up at me.

"'Blister,' he says, 'do you ever tumble there's two ringers in the New Awlins deal? Me 'n' Buck Harms has quite a time puttin' it over—without slippin' you five hundred.'

"It's Elsy! 'N' say!—his voice ain't any squeakier 'n mine!"

At our last meeting Blister had told me of a "ringing" in years gone by that had ended disastrously for him. And now as we idled in the big empty grand-stand a full hour before it would be electrified by the leaping phrase, "They're off!" I desired further reminiscences.

"Ringing a horse must be a risky business?" I ventured.

"Humph!" grunted Blister, evidently declining to comment on the obvious. Then he glanced at me with a dry whimsical smile. "I see that little ole pad stickin' out of your pocket," he said. "Ain't she full of race-hoss talk yet?"

"Always room for one more," I replied, frankly producing the note-book.

"Well, I guess I'm the goat," he said resignedly. "I had figured to sick you on to Peewee Simpson to-day, but he ain't around, so I'll spill some chatter about ringin' a hoss among the society bunch one time, 'n' then I'll buy a bucket of suds."

"I'll buy the beer," I stated with emphasis.

"All right—just so we get it—I'll be dryer'n a covered bridge," said Blister.

"This ringin' I mentions," he went on, "happens while I'm ruled off.

"At the get-away I've got a job with a Chicago buyer, who used to live in New York. This guy has a big ratty barn. He deals mostly in broken-down skates that he sells to pedlers 'n' cabmen. Once in a while he takes a flier in high-grade stuff, 'n' one day he buys a team of French coach hosses from a breedin' farm owned by a millionaire.

"Believe me they was a grand pair—seal brown, sixteen hands 'n' haired like babies. They fans their noses with their knees, when get's the word, 'n' after I sits behind 'em 'n' watches their hock-action fur a while I feels like apologizin' to 'em fur makin' 'em haul a bum like me.

"These dolls go East,' says the guy I works fur. 'They don't pull no pig-sticker in this burg. They'll be at the Garden so much they'll head fur Madison Square whenever they're taken out.'

"He ships the pair East 'n' sends me with 'em as caretaker. I deliver 'em to a swell sales company up-town in New York.

"This concern has some joint—take it from me—every floor is just bulgin' with hosses that's so classy they sends 'em to a manicure parlor 'stead of a blacksmith's shop.

"There's a big show-ring, with a balcony all 'round it, on the top floor. They take my pair up there 'n' hook 'em to a hot wagon painted yellow, 'n' the company's main squeeze, named Brown, comes up to see 'em act. I'm facin' the door just as a guy starts to lead a hoss into the show-ring. The pair swings by, this hoss shies back sudden 'n' I see him make a queer move with his off rear leg. Brown don't see it—he's got his back to the door.

"The guy leads the hoss up to us.

"'Here's that hunter I phoned you about, Mr. Brown,' he says. The hoss is a toppy trick—bright bay, short backed, good coupled 'n' 'll weigh eleven hundred strong. But he's got a knot on his near-fore that shows plain.

"'I thought you told me he was sound?' says Brown, lookin' at the knot.

"'What's the matter with you, Mr. Brown?' says the guy. 'That little thing don't bother him. Any eight-year-old hunter that knows the game is bound to be blemished in front.'

"'Can you tell an unsound one when you look at him?' Brown asks me.

"'I can smell a dink a mile off,' I says.

"'Here's an outside party,' says Brown; 'let's hear what he has to say. Feel that bump, young man!' he says to me.

"I runs my hand over the knot.

"'That don't hurt him,' I says. 'It's on the shin 'n' part of it's thick skin.'

"'There!' says the guy. 'Your own man's against you.'

"'He's not my man,' says Brown, lookin' at me disgusted.

"'This ain't my funeral,' I says to Brown. ''N' I ain't had a call to butt in. If you tells me to butt—I butts.'

"'Go to it,' says Brown.

"'Do you throw a crutch in with this one?' I says to the guy.

"'What does he need a crutch for?' he says, givin' me a sour look.

"I takes the hoss by the head, backs him real sudden, 'n' he lifts the off-rear high 'n' stiff.

"'He's a stringer,' I says.

"Brown gives the guy the laugh.

"'You might get thirty dollars from a Jew pedler for him,' he says. 'He'll make a high-class hunter—for paper, rags and old iron.'

"'How did you know that horse was string-halted so quick?' says Brown to me when the guy has gone.

"'I told you I can smell a dink,' I says. But I don't tell him what I sees at the door.

"'I think we could use you and your nose around here,' he says. 'Are you stuck on Chicago?'

"'Me fur this joint,' I says, lookin' 'round. 'Do I have to get my hair waved more 'n' twict a week?'

"'We'll waive that in your case,' he says, laughin' at his bum joke.

"'Don't do that again,' I says. 'I've a notion to quit right here.'

"'I'd hate to lose an old employee like you—I'll have to be more careful,' he says—'n' I'm workin' fur Mr. Brown.

"About a week after this, I'm bringin' a hackney up to the showroom fur Brown to look at, when a young chap dressed like a shoffer stops me.

"'I wish to see Mr. Brown, my man,' he says. 'Can you tell me where he is?'

"No shofe can spring this 'my man' stuff on me, 'n' get away with it. But a blind kitten can see this guy's all the gravy. There's somethin' about him makes you think the best ain't near as good as he wants. I tells him to come along with me, 'n' when we gets up to the showroom he sticks a card at Brown.

"'Yes, indeed—Mr. Van Voast!' says Brown, when he squints at the card. 'You're almost the only member of your family I have been unable to serve. I believe I have read that you are devoted to the motor game.'

"'That's an indiscretion I hope to rectify—I want a hunter,' says the young chap.

"'Take that horse down and bring up Sally Waters,' says Brown to me.

"This Sally Waters is a chestnut mare that's kep' in a big stall where she gets the best light 'n' air in the buildin'. A lot of guys have looked at her, but the price is so fierce nobody takes her.

"'Is that the best you have?' says the young chap, when I gets back with her.

"'Yes, Mr. Van Voast,' says Brown. 'And she's as good as ever stood on four legs! She'll carry your weight nicely, too.'

"'Is she fast?' says the young chap.

"'After racing at ninety miles an hour, anything in horse-flesh would seem slow to you, I presume,' says Brown. 'But she is an extremely fast hunter, and very thorough at a fence.'

"'Do you know Ferguson's Macbeth?' says the young chap.

"'I ought to,' says Brown. 'We imported Macbeth and Mr. Ferguson bought him from me.'

"The young chap studies a minute.

"'I might as well tell you that I want a hunter to beat Macbeth for the Melford Cup,' he says at last.

"'Oh, oh!' says Brown. 'That's too large an order, Mr. Van Voast—I can't fill it.'

"'You don't think this mare can beat Macbeth?' says the young chap.

"'No, sir, I do not,' says Brown. 'Nor any other hunter I ever saw. There might be something in England that would be up to it, but I don't know what it would be—and money wouldn't buy it if I knew.'

"The young chap won't look at the mare no more, 'n' Brown tells me to put her up. I hustles her back to the stall, 'n' goes down to the street door 'n' waits. There's a big gray automobile at the curb, with six guns stickin' out of her side in front—she looks like a battle-ship. Pretty soon the young chap comes out 'n' starts to board her 'n' I braces him.

"'I think I know where you can get the hoss you're lookin' fur,' I says.

"He stares at me kind-a puzzled fur a minute.

"'Oh, yes, you are the man who brought the mare up-stairs,' he says. 'What leads you to believe you can find a hunter good enough to beat Macbeth?'

"'I ain't said nothin' about a hunter,' I says. 'Would you stand fur a ringer?'

"'I think I get your inference,' he says. 'Be a little more specific, please.'

"'If I puts you hep to a hoss that ain't no more a hunter than that automobile,' I says, 'but can run like the buzz-wagon 'n' jump like a hunter—could you use him in your business?'

"'What sort of a horse would that be?' he says.

"'A thoroughbred,' I says. 'A bang-tail.'

"'Oh—a runner,' he says. 'Do you know anything about the runners?'

"'A few,' I says. 'I'm on the track nine years.'

"'What are you doing here?' he says.

"'Ruled off,' I says.

"'Hm-m!' he says. 'What for?'

"'Ringin',' I says.

"'You seem to run to that sort of thing,' he says. 'What's your name?' he asks.

"'Blister Jones,' I says.

"'Delightful!' he says. 'I'm glad I met you. Who has this remarkable horse?'

"'Peewee Simpson,' I says.

"'Equally delightful! I'd like to meet him, too,' he says.

"'He's in Loueyville,' I says.

"'Regrettable,' he says. 'What's the name of his horse?'

"'Rainbow,' I says.

"'And I thought this was to be a dull day,' he says. 'Jump in here and take a ride. I don't know that I care to go rainbow-chasing assisted by Blisters, and Peewees—but nefarious undertakings have always appealed to me, and I desire to cultivate your acquaintance.'

"We goes fur a long ride in the battle-ship. He don't say much—just asks questions 'n' listens to my guff. At last I opens up on the Rainbow deal, 'n' I tries all I know to get him goin'—I sure slips him some warm conversation.

"'You heard what Brown said of Macbeth!' he says. 'Why are you so certain this Rainbow can beat him in a steeplechase?'

"'Why, listen, man!' I says. 'This Rainbow is the best ever. He can beat any brush-topper now racin' if the handicapper don't overload him. He's been coppin' where they race your eyeballs off. He's been makin' good against the real thing. He's a thoroughbred! If he turns in one of these here parlor races fur gents, with a bunch of hunters, they won't know which way he went!'

"'The runners I have seen are all neck and legs. They don't look like hunters at all,' he says.

"'You're thinkin' about these here flat-shouldered sprinters,' I says. 'This Rainbow is a brush-topper. He's got a pair of shoulders on him 'n' he's the jumpin'est thoroughbred ever I saw. Course he's rangier 'n most huntin'-bred hosses, but with a curb to put some bow in his neck, he'll pass fur a hunter anywhere!'

"'There is one sad thing I haven't told you,' he says. 'I must ride the horse myself.'

"'What's sad about that?' I says. 'You ain't much over a hundred 'n' forty, at a guess.'

"'The trouble is not with my weight—it's my disposition,' he says. 'I have not ridden for ten years. In fact I never rode much. To tell you the truth—I'm afraid of a horse.'

"Say—I'd liked that young chap fine till then! I think he's handin' me a josh at first.

"'You're kiddin' me, ain't you?' I says.

"'No,' he says. 'I'm not kidding you. I've fought my fear of horses since I was old enough to think. Lately it has become necessary for me to ride, and I'm going to do it—it it kills me!'

"We were back to my joint by this time 'n' he looks at me 'n' laughs.

"'Cheer up!' he says. 'I'll think over what you told me and let you know. I go over to Philadelphia to-morrow to race in a "buzz-wagon," as you call it. I don't want you to think me entirely chicken-hearted—and I'll take you with me, if Brown can spare you.'

"The next day he shows up in the battle-ship.

"'Blister,' he says, 'I don't know just how far I'll be willing to go in the affair, but if you can get Rainbow, I'll buy him.'

"'Now you've said somethin',' I says. 'Head fur the nearest telegraph office 'n' I'll wire Peewee.'

"'They're likely to ask a stiff price fur this hoss,' I says when we gets to the telegraph office.

"'Buy him,' he says.

"'Do you mean the sky's the limit?' I says, 'n' he nods.

"We cross on the ferry after sendin' the wire. He has the battle-ship under wraps till we hit the open country, 'n' then he lets her step. We gets to goin' faster 'n' faster. I can't see, 'n' I think my eyebrows have blowed off. I'm so scared I feel like my stumick has crawled up in my chest, but I hopes this is the limit, 'n' I grits my teeth to keep from yelpin'. Just then we hits a long straight road, 'n' what we'd been doin' before seemed like backin' up. I can't breathe 'n' I can't stand no more of it.

"'Holy cats!' I yells. 'Cut it!'

"'What's the matter?' he says, when he's slowed down.

"'Holy cats!' I says again. 'Is that what racin' in these things is like?'

"'Oh, no,' he says. 'My mechanic took my racing car over yesterday. This is only a roadster.'

"'Only a—what?' I says.

"'Only a roadster—a pleasure car,' he says.

"'Oh—a pleasure car,' I says. 'It's lucky you told me.'

"'It's all in getting accustomed to it,' he says.

"I spends the night at a hotel in Philadelphia with a guy named Ben, who's the mechanic, 'n' the next mawnin' I sees the race. Say! Prize-fightin', or war, or any of them little games is like button-button to this automobile racin'! They kills two guys that day 'n' why they ain't all killed is by me. The young chap finishes second to some Eyetalian—but that Dago sure knowed he'd been in a race.

"''N' he's the guy that's afraid of a hoss!' I says to myself. 'Now, wouldn't that scald you?'

"When he leaves me at my joint in New York the young chap writes on a card 'n' hands it to me.

"'Here's my name and present address,' he says. 'Let me know when you hear from our friend Peewee.'

"Printed on the card is 'Mr. William Dumont Van Voast,' 'n' in pencil, 'Union Club, New York City.'

"The next day I gets a wire from Peewee in answer to mine.

"'Sound as a dollar. Eighteen hundred bones buys him. P. W. Simpson,' it says.

"I phones Mr. Van, 'n' he says to go to it—so I wires Peewee.

"'Check on delivery if sound. You know me. Ship with swipe first express. Blister Jones.'

"In two days Duckfoot Johnson leads ole Rainbow into the joint, 'n' I tells Brown it's a hoss fur Mr. Van. I looks him over good 'n' he's O. K. I gets Mr. Van on the phone 'n' he comes up 'n' writes a check fur eighteen hundred, payable to Peewee. He gives this to Duckfoot, slips him twenty-five bucks fur hisself, 'n' hands him the fare back to Loueyville besides.

"'What next?' says Mr. Van to me. 'Do we need a burglar's kit, and some nitroglycerin, or does that class of crime come later?'

"'We want a vet. right now,' I says. 'This bird has got to lose some tail feathers.'

"'Well, you are the chief buccaneer!' says Mr. Van. 'I'll serve as one of the pirate crew at present. When you have the good ship Rainbow shortened at the stem and ready to carry the jolly Roger over the high seas—I should say, fences—let me know. In the meantime,' he says, slippin' me five twenties, 'here are some pieces-of-eight with which to buy cutlasses, hand grenades and other things we may need.'

"I has the vet. dock Rainbow's tail, 'n' as soon as it heals I lets Mr. Van know. He tells me to bring the hoss to Morrisville, New Jersey, on the three o'clock train next day.

"When I unloads from the express car at Morrisville, there's Mr. Van and a shoffer in the battle-ship.

"'Just follow along behind, Blister!' says Mr. Van, 'n' drives off slow down the street.

"We go through town 'n' out to a big white house, with pillars down the front. Mr. Van stops the battle-ship at the gates.

"'Take the car to the Williamson place—Mr. Williamson understands,' he says to the shofe.

"I wonders why he stops out here—it's a quarter of a mile to the house. When we gets to the house there's an old gent, with gray hair, settin' on the porch. He gets up when he sees us, 'n' limps down the steps with a cane.

"'Don't disturb yourself, Governor!' says Mr. Van. 'Anybody here?'

"'No, I'm alone,' says the old gent. 'Your sister is with the Dandridges. Your man came this morning, so I was expecting you.' Then he looks at Rainbow. 'What's that?' he says.

"'A horse I've bought,' says Mr. Van. 'I'm thinking of going in for hunting.'

"'Oh! She's brought you to it, has she?' says the old gent. 'I never could. Why do you bring the horse here?'

"Mr. Van flushes up.

"'You know what a duffer I am on a horse, Governor,' he says. 'Well, I want to try for the Melford Cup. I'd like to build a course on the place, and school myself under your direction.'

"'Ah, ha!' says the old gent. 'And then the conquering hero will descend on Melford, to capture the place in general, and one of its fair daughters in particular!'

"'Something like that,' says Mr. Van.

"'I'll be glad to help you all I can,' says the old gent, 'just so long as you don't bring one of those stinking things you usually inhabit on these premises!'

"'It's a bargain. I've already sent the one I came in to Ralph Williamson,' says Mr. Van, 'n' we takes Rainbow to the stables.

"I liked Mr. Van's old man right away, 'n' when he finds out I knows as much about a hoss as he does, he treats me like a brother.

"He gets busy quick, 'n' has the men fix up a mile course on the place with eight fences in it—some of 'em fierce.

"'Twice around, and you have the Melford course to a dot,' he says. 'Now, young man,' he says to me, 'you get the horse ready and I'll go to work on the rider.' 'N' believe me, he does it.

"His bum leg won't let him ride no more, but he puts Mr. Van on a good steady jumper, 'n' drives besides the course in a cart, tellin' him what to do. He keeps Mr. Van goin' till I think he'll put him out of business—'n' say!—but he cusses wicked when things don't go to suit him!

"'Stick your knees in and keep your backbone limber! Hold his head up now at this jump—don't drag at his mouth that way! Why! damn it all!… you haven't as good hands as a cab-driver,' is the kind of stuff he keeps yellin' at poor Mr. Van.

"I'm workin' Rainbow each day, 'n' in three weeks I take him twice around the course at a good clip.

"'The hoss'll do in another week,' I says to the old gent.

"'I'll be ready fur you,' he says, shuttin' his mouth, 'n' that was the worst week of all for Mr. Van. But he improved wonderful, 'n' one mawnin' he takes Rainbow over the course at speed.

"'Not half bad!' says the old gent when they come back. 'He's not up to his horse yet,' he says to me. 'But between 'em they'll worry that Melford crowd some, or I miss my guess!'

"A day or so after that we starts for Melford. The old gent says good-by to me, 'n' then he sticks out his mitt at Mr. Van.

"'God bless you, boy!' he says. 'I wish you luck both in the race and—elsewhere.'

"Say, this Melford is the horsiest burg ever I saw! They don't do nothin' but ride 'em 'n' drive 'em 'n' chew the rag about 'em—men 'n' women the same. Even the kids has toppy little ponies and has hoss shows fur their stuff.

"They has what they call a Hunt Club, 'n' everybody hangs out there. This club gives the cup Mr. Van wants to win. The race fur it is pulled off once a year, 'n' only club members can enter.

"The Ferguson guy has won the race twice with the Macbeth hoss 'n' if he wins it again he keeps the cup. The race is due in two weeks, but there ain't much talk about it—everybody knows Ferguson'll win sure.

"This Ferguson has all the kale in the world. He lives in a house so big it looks like the Waldorf. But from what I hear, the bloods ain't so awful strong fur him—except his ridin', they all take their hats off to that.

"There's a girl named Livingston 's the best rider among the dames, 'n', believe me, she's a swell doll—she's the niftiest filly I ever gets my lamps on—she's all to the peaches 'n' cream.

"It don't take me long to see that Mr. Van is nutty, right, about this one, but it looks like Ferguson has the bulge on him, 'cause her 'n' Ferguson is always out in front when they chase the hounds, 'n' they ride together a lot. We're at Mr. Van's brother's place, 'n' when we first get there Mr. Van puts me wise.

"'Blister,' he says, 'you must now assume the disguise of a groom. While you and I know we are partners in crime, custom requires an outward change in our heretofore delightful relationship—keep your eyes open and act accordingly.'

"I'm dead hep to what he means, 'n' when I'm rigged up like all the rest of the swipes around there, I touches my hat to him whenever he tells me anythin'.

"Everybody joshes Mr. Van about his ridin', but they get over that sudden—the first time he chases hounds with 'em ole Rainbow 'n' him stays right at the head of the procession. I'm waitin' at the club to take the hoss home after the run. When Mr. Van is turnin' him over to me Miss Livingston comes up.

"'I'm so proud of you!' she says to him. 'It was splendid … I told you you could do anything you tried!'

"'Rainbow's the chap who deserves your approval,' says Mr. Van, pointin' to the hoss.

"'Indeed, he does—the old precious!' she says, 'n' rubs her face against Rainbow's nose. Just then Ferguson rides up with a English gink who's a friend of Mr. Van's, 'n' the dame beats it into the club-house. This Englishman is a lord or a duke or somethin', 'n' he's visitin' Mr. Van's brother. Ferguson ain't on Macbeth. He's rode a bay mare that day, 'n' Rainbow has outrun 'n' out-jumped her.

"'That's quite a horse you have there, Van,' Ferguson says. 'A bit leggy—isn't he?'

"'Perhaps he is,' says Mr. Van. 'But I like something that can get over the country.'

"'Going to enter him for the cup?' says Ferguson.

"'I don't know yet,' says Mr. Van, careless. 'I must see the committee, and tell them his antecedents—this horse rather outclasses most hunters.'

"'He doesn't outclass mine, over the cup course, for five thousand!' says Ferguson, gettin' red.

"'Done!' says Mr. Van, quiet-like. 'If the committee says I'm eligible we'll settle it in the cup race. If not, we can run a match.'

"'Entirely satisfactory,' says Ferguson, 'n' starts to go. But he comes back, 'n' looks at Mr. Van wicked. 'By the way,' he says, 'money doesn't interest either of us at present. Suppose we raise the stake this way—the loser will take a trip abroad, for a year, and in the meantime we both agree to let matters rest—in a certain quarter.'

"'Done!' says Mr. Van again. He looks at the other guy colder 'n ice when he says it.

"Ferguson nods to him 'n' rides off.

"The English gink has heard the bet, 'n' when Ferguson beats it he shakes his head.

"'Aw, old chap!' he says. 'That's a bit raw—don't you think? I'm sorry you let him draw you. It's a beastly mess.'

"'I'm not afraid of him and his horse!' says Mr. Van. But I can see he ain't feelin' joyous.

"'Damn him and his hawss—and you too!' says the English gink. 'Aw, it's the young girl you've dragged into it, Billy!'

"'It's a confidential matter, and no names were mentioned,' says Mr. Van.

"'Don't quibble, old chap!' says the English gink. 'The name's nothing. And as for its being confidential—Ferguson is sure to tell that—aw—French puppy he's so thick with, and the viscawnt'll be—aw—tea-tabling it about by five o'clock!'

"'You're right, of course,' says Mr. Van, slow. 'It was a low thing to do—a cad's trick. No wonder you English are so rotten superior. You don't need brains—the right thing's bred into your bones. Your tempers never show you up. We revert to the gutter at the pinch.'

"'Oh, I say! That's bally nonsense!' says the English gink. 'I would have done the same thing.'

"'Not unless the fifteen hundred years it's taken to make you were wiped off the slate,' says Mr. Van. 'However, I'll have to see it through now.'

"The guys that run the club say Rainbow can start in the cup race. Mr. Van tells me, 'n' the next week I watch him while he sends the hoss over the course. We're comin' up towards the club-house, after the work-out, 'n' we run into Miss Livingston. She hands Mr. Van the icy stare 'n' he starts to say something but she breaks in.

"'I wonder you care to waste any words on a mere racing wager,' she says.

"'Please let me try to explain …' says Mr. Van.

"'There can be no explanation. What you did was the act of a boor—and a fool,' says the dame, 'n' walks on by.

"I think over what she says. 'She's more sore cause she thinks he'll lose than anythin' else,' I says to myself. 'He ain't in so bad, after all.' But Mr. Van don't tumble. He's awful glum from then on.

"There's a fierce mob of swells at the course the day of the race, classy rigs as far as you can see. The last thing I says to Mr. Van is:

"'You've got the step of them any place in the route, but you're on a thoroughbred, 'n' he'll run hisself into the ground if you let him. You don't know how to rate him right—so stay close to the Macbeth hoss till you come to the last fence, then turn Rainbow loose, 'n' he'll make his stretch-run alone.'

"There's six entries, but the race is between Rainbow and Macbeth from the get-away. Macbeth is a black hoss, 'n' I never believed till then a hunter could romp that fast. He was three len'ths ahead of the field at the first fence, with Rainbow right at his necktie. They gets so far ahead, nobody sees the other starters from the second fence on. Mr. Van rides just like I tells him, 'n' lets the black hoss make the pace. Man!—that hunter did run! Towards the end both hosses begin to tire, but the clip was easier fur the thoroughbred, 'n' I see Rainbow's got the most left.

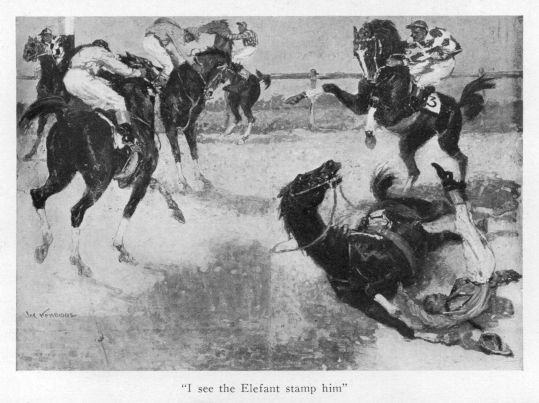

"Before they come to the last fence Mr. Van turns his hoss loose like I tells him, 'n' he starts to come away from Macbeth. My! but those swells did holler! They never thought Rainbow has a chance. At the last fence he's a len'th in front, 'n' right there it happens Mr. Van don't take hold of him enough to keep his head up, 'n' he blunders at the fence 'n' comes down hard on his knees. Mr. Van slides clear to the hoss's ears, 'n' the crowd gives a groan as Macbeth comes over 'n' goes by.

"'He's gone!' I says to myself, 'n' I can't believe it when he gets back in the saddle somehow 'n' starts to ride. But the black hoss has a good six len'ths 'n' now two hundred yards to go.

"'He'll never reach …' I says out loud. 'He'll never reach …'

"Then Rainbow begins his stretch-run with the blood comin' out of his knees, 'n' while he's a tired hoss, a gamer one never looks through a bridle. I ain't knockin' that hunter—there was no canary in him, but I think a game thoroughbred's the gamest hoss that lives!

"Ole Rainbow is a straight line from his nose to his tail. His ears is flat 'n' his mouth's half open fur air. Every jump he takes looks thirty feet long 'n' he's gettin' to the black hoss fast. I'm watchin' the distance to go 'n' all of a sudden I furgets where I am—.

"'He wins sure as hell!' I hollers.

"'Oh, will he?' says a voice. I looks up 'n' there's Miss Livingston sittin' on her hoss, her fists doubled up 'n' her face whiter'n chalk.

"About ten len'ths from the finish Rainbow gets to the black 'n' they look each other in the eye. But them long jumps of the thoroughbred breaks the hunter's heart, 'n' Rainbow comes away, 'n' wins by a len'th.…

"After I've cooled Rainbow out, 'n' bandaged his knees at the club stables, I starts fur home with him.

"I'm just leavin' the main road, to take the short cut, when Miss Livingston gallops by, with a groom trailin'. She looks up the cross-road, sees me 'n' the hoss, 'n' reins in. She says somethin' to the groom 'n' he goes on.