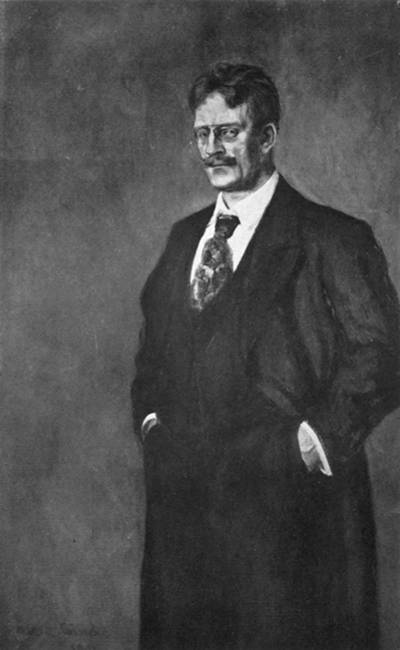

Knut Hamsun

Knut HamsunPhoto by Wilse

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Knut Hamsun, by Hanna Astrup Larsen This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Knut Hamsun Author: Hanna Astrup Larsen Release Date: July 16, 2011 [EBook #36754] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK KNUT HAMSUN *** Produced by Bryan Ness and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

Obvious punctuation errors have been repaired silently. Word errors have been corrected and a list of corrections can be found after the book.

MR. ALFRED A. KNOPF

has been appointed the sole authorized

American publisher of

KNUT HAMSUN

The following books are now ready:

The following are scheduled for later publications:

Knut Hamsun

Knut HamsunKnut Hamsun

by

Hanna Astrup Larsen

Editor "The American-Scandinavian Review"

New York

Alfred · A · Knopf

Mcmxxii

COPYRIGHT, 1922, BY

ALFRED A. KNOPF, Inc.

Published, October, 1922

Set up and printed by the Vail-Ballou Co., Binghamton, N. Y.

Paper furnished by W. F. Etherington & Co., New York.

Bound by the H. Wolff Estate, New York.

MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

The author wishes to acknowledge her debt to The American-Scandinavian Foundation for the Fellowship which enabled her to study the works of Hamsun in Norway during the winter of 1920-1921.

Knut Hamsun has become identified in our minds with the lonely figure that recurs again and again in his earlier books, the Wanderer who is for ever outside of organized society and for ever pays the penalty of being different from the crowd and unable to conform to its standards. That this lonely creature is really himself in a certain period of his life we know from the testimony of his own works. Yet this vagabond and iconoclast sprang from the most conservative stock of Norway. He is the descendant of an old peasant family in Gudbrandsdalen, one of the interior mountain valleys in the heart of the country.

Gudbrandsdalen is a region of proud historical traditions. There, nine centuries ago, King Saint Olaf struggled to foist the new religion on a stiff-necked race of pagans, and not far from Hamsun's birthplace one of the oldest churches in Norway proclaimed his victory. There, six centuries ago, the Scotch invader Sinclair was annihilated with all his force when "the peasants of Vaage and Lesje and Lom their whetted axes shouldered," as the ballad tells us, and the story is still cherished, still repeated to every traveller. In this as in other secluded valleys in Norway a peasant aristocracy developed, a hard, strong race, intensely proud of its family and land, looking on any one who had been less than three generations in the neighborhood as an interloper, and scorning the classes of people who were not rooted to the soil by inherited homesteads. For the Norwegian roving blood is strangely tempered by a passionate attachment to inherited land, a trait that is perhaps a salutary safeguard against the national restlessness. Artistic handicrafts flourished in the valley. In the Open Air Museum at Lillehammer we may see them even now, marvellous creations of hammered iron, tapestries picturing scenes from the Bible, wood carvings in mellow colors and with a Renaissance exuberance of design overflowing even the commonest kitchen utensils, all of a rich yet disciplined beauty as if built on age-old artistic traditions and standards.

Hamsun counted among his forefathers many of the artistic craftsmen who set their stamp of culture upon their community. His father's father was a worker in metals. The arts did not bring wealth to those who practised them, however, and his parents at the time of his birth were in straitened circumstances. He was born, August 4, 1859, in Lom, in one of the small well-weathered houses which look so bleak and insignificant against the mighty Gudbrandsdalen uplands. When he was four years old his family removed to the Lofoten Islands, Nordland, in an effort to better their fortunes.

Two strains may be traced in Knut Hamsun's personality. By virtue of his blood and birth he had his roots in a community characterized by an unusually firm and solid culture based on centuries of tradition, and this heritage we shall find coming out in him more and more in his later years. The moralist and preacher who wrote "Growth of the Soil" is a true scion of the best old peasant stock. Through the impressions of his childhood and early youth he became affiliated with the volatile race of Nordland, a people as alien from the heavier inland peasant as if they lived on different continents. The fishermen who play with death for the wealth of the sea and depend for their livelihood on the caprices of nature do not easily harden into traditional moulds. Childish and improvident, witty and sentimental, often fond of the melodramatic, simple and yet shrewd, superstitious but brave beyond all praise, the native of Nordland is a type unlike every other Norwegian. Wherever he may roam, he will yearn for the wonderland of his youth. It is from this Nordland type that Hamsun has created his Wanderer hero, and it was from the nature of Nordland with its alternations of melting loveliness and stark gloom that he drew his poetic inspiration.

At the very time when Hamsun was spending his childhood in the Lofoten Islands, Jonas Lie, the literary discoverer of Arctic Norway, wrote his idyllic little story "Second Sight" in which he has really delineated a "Wanderer" type, his hero being a gifted Nordland lad who is set apart from ordinary people by his strange mental malady and who, wherever he goes, feels himself an alien. In this book, written at a time when not even fixed steamship routes united Nordland with the southern part of the country (railroads are even yet unknown), Jonas Lie has given us a classic description of the country in its virgin state of isolation. It gives the key to that mysterious, extravagant strain which belongs to the Nordland type, and throws light on the sources from which Hamsun drew his hero.

The words that to other people convey only commonplaces become magnified in the Nordland mind accustomed to the ecstatic moods of nature, Lie tells us. Fish to a Nordlanding means Lofoten's and Finmarken's millions, an infinite variety, from the spouting whales that penetrate our fjords driving huge masses of fish like a froth before them, to the tiniest minnow. When he speaks of birds, the Nordlanding does not mean merely an eatable fowl or two, but a heavenly host, billowing in the air like white breakers around the bird crags, shrieking and fluttering and filling the air like a veritable snow-storm over the nesting-places. He thinks of the eider-duck and the tystey; the duck and the sea-pie swimming in fjord and sound or perched on the rocks; the gull, the osprey, and the eagle sailing through the air; the owl moaning weirdly in the mountain clefts—a world of birds. A storm at sea to him means sudden hurricanes that sweep down from the mountains and uproot buildings—so that people at home often have to tie down their houses with chains—waves rushing in from the Arctic Ocean fathoms high, burying big rocks and skerries in their froth and then receding so fast that a ship may be left high and dry and be smashed right in the open sea; hosts of brave men sailing before the wind to save not only their own lives but the dearly bought boatload on which the lives of those at home depend.

"There in the North popular fancy from mythical times has imagined the home of all the powers of evil. There the Lapp has made himself feared by his sorceries, and there at the outermost edge of the world, washed by the breakers of the dark, wintry grey Arctic Ocean, stand the gods of primitive times, the demoniacal, terrible, half formless powers of darkness against whom even the Æsir did battle, but who were not entirely vanquished before St. Olaf with his cruciform sword 'set them in stock and stone.'—The terrors of nature have created an army of evil demons that draw people to them, ghosts of drowned men who have not been buried in Christian earth, mountain titans, the sea draug who sails in his half boat and in the winter nights shrieks terribly out on the fjord. Many a man in real danger has perished because his comrades were afraid of the draug, and we of second sight can see him.

"But even though the overwhelming might of nature bears down with oppressive weight on everything living along that dark, wintry, frothing coast, where nine months of the year are a constant twilight and three of these are without even a glimpse of the sun, so that people's minds become filled with fear of the dark, yet Nordland also possesses the opposite extreme in its sun-warmed, clear-skied, scent-filled summers with their endless play of infinitely varied colors and tints, when distances of seventy or eighty miles seem to melt away so that we can shout across them, when the mountain clothes itself in brownish green grass to the very top—in Lofoten to a height of two thousand feet—and the slender birch trees wreathe the tops of the hills and the edges of the mountain clefts like a dance of sixteen-year-old white-clad girls, while the fragrance of strawberries and raspberries rises to you through the warm air as you pass in your shirt sleeves, and the day is so hot that you long to bathe in the sun-filled, rippling sea which is clear to the very bottom.

"The learned say that the intensities of color and fragrance in the far North are due to the power of the light which fills the air when the sun shines without interruption day and night. Therefore one can not pick so aromatic strawberries and raspberries or so fragrant birch boughs in any other clime. If a fairy idyl has any home, it is certainly in the deep fjord valleys of Nordland in the summer. It is as though the sun were kissing nature so much more tenderly because they have such a short time to be together and must soon part again."

Jonas Lie's description, which I have taken the liberty to quote in abbreviated form, gives a picture of the surroundings in which Hamsun spent his boyhood. It would have been impossible to find any spot in the world more suited to nourish the fancy of an imaginative, impressionable boy. Lonely as he was, he had little to interest him or occupy his mind except what he could find for himself out of doors. He was put to work herding cattle, and spent long dreamy hours alone revelling in the loveliness of the light Nordland summer. It was then he laid the foundation for his habit of roaming alone in the woods and fields, and there he gained that intimate, tender knowledge of nature which appears in his works. In telling of his childhood, Hamsun says that the animals and birds became his friends. He speaks also of the deep impression which the sea made upon him. His uncle's house, where he spent some of his boyhood, was built above the ocean stream, Glimma, which rushed over a rocky bottom, sometimes one way, sometimes another, according to the tide, but always in motion. Beyond it lay the open sea.

The sharp contrasts of nature, its alternations between darkness and light, are reflected in the temperament of the Nordland people who are easily swung from one extreme to another. Underneath the brightness and levity there is a consciousness of superstitions that are felt sometimes as dark and sinister forces waiting to drag men away from the light into the gloomy void where the evil powers reign. The boy Knut Hamsun's nature was like a sensitive stringed instrument vibrating to the faintest breath of nature's moods, and we find in his works the nervousness, the quick transitions, and the swinging between extremes of exaltation and despair which belong to the Nordland type. While the brightness predominates, the gloom is also present, especially in his earliest, most personal works.

The years he spent with his clergyman uncle were not happy. The uncle had no idea of how to handle a highstrung boy, and his method of education consisted of many lickings, much hard work, and few hours for play. So lonely and dreary was the boy's life that he found his chief amusement in roaming about in the cemetery, spelling out the inscriptions on crosses and slabs, making up stories about them, and talking to himself, or listening to the wind rustling in the grass that grew tall on neglected graves. Occasionally the old weather vane on the church steeple would let out a terrible shriek when the wind veered. It sounded like "iron gritting its teeth against some other iron." Sometimes he would help the old grave-digger in his work, and he had strict injunctions on what to do if bits of bone or tufts of hair worked their way out to the surface. They were to be put back in place and decently covered. Once, however, he ventured to disobey the gravedigger and take with him a tooth which he thought he could use for some little object he was fashioning. In the short story "A Ghost" in the collection "Things that Have Happened to Me," where he draws this dismal story of his childhood, he tells how the dead owner appeared to him and threatened him at intervals for years afterwards, even after he had left the house of his uncle and was living with his parents, where he shared a room with his brothers and sisters. The apparition froze him with fear and tortured him so that he was often tempted to throw himself in the Glimma and end it all. Of the effect that this incident had upon him he writes: "This man, this red-bearded messenger from the land of death, did me much harm by the unspeakable gloom he cast over my childhood. Since then I have had more than one vision, more than one strange encounter with the inexplicable but nothing that has gripped me with such force. And yet perhaps the effect upon me was not all harmful. I have often thought of that. It has occurred to me that he was one of the first things that made me grit my teeth and harden myself. In my later experiences I have often had need of it."

In view of the high position clergymen hold in Norway, and especially considering the prestige attached to the official class fifty years ago, it seems odd that a clergyman's nephew, an inmate of his house for years, should have been slated for a shoemaker, but evidently there was no money with which to send Knut to school, and perhaps his mental gifts were not of the caliber to promise that he would fit easily into any one of the usual professional niches. After his confirmation, which is the Norwegian boy's entrance to manhood, he was therefore apprenticed to a cobbler in the city of Bodö on the mainland. In his own mind, however, he was quite determined that he was to be a poet, and it was while working for the cobbler that he published his first literary venture, a highly romantic poem called "Meeting Again." This was followed by the story "Björger, by Knud Pedersen Hamsund," a gloomy, introspective tale of an orphaned peasant boy and a lady of high degree who died for love of him—a foreshadowing of the motif in "Victoria." In spite of its immaturity, its absurdity even, the story, according to the judgment of critics to-day, shows flashes of Hamsun's peculiar genius. Alas, there were no critics wise and sympathetic enough to see its promise at the time, if indeed any critics read it. The book was printed by the nineteen-year-old author at his own expense, paid for by his hard-earned savings, and was bought by a few people in Bodö, but hardly circulated beyond the confines of the city.

Naturally the cobbler's bench could not long confine his restlessness, and, after a short experience as a coal-heaver on the docks of Bodö—where his eye-glasses attracted amused attention as out of keeping with his work—Hamsun set out on the wanderings that were to last full ten years. He taught a little school, was clerk in a sheriff's office, and crushed stones on the road.

The experiences of this period were the foundation of his two novels "Under the Autumn Star" and "A Wanderer Plays with Muted Strings," bound in the English edition under the common title "Wanderers." Written many years later from the standpoint of an elderly citizen who leaves his home in the city to revisit the haunts of his youth and play at being a vagrant laborer once more, they give his adventures in the softening light of retrospect. A touch of personal description may be found in the lines, "I taught myself to walk with long, tenacious steps. The proletarian appearance I had already in my face and hands."

There is a lingering tenderness in the author's treatment of these years which would indicate that at the time of writing he looked back upon them almost with regretful longing. We do not find the smallest trace of the acrid bitterness which he put into the short stories from his American experiences or into the account of his struggles to gain a foothold in Christiania. The roving life without fixed habitation or routine had its charms for him and it gave him an opportunity to be much out of doors. Strong and capable as he was, the manual labor in itself held no terrors for him, and he was rather proud of his inventive skill. "Under the Autumn Star" recounts a number of small technical triumphs, chief among which was a marvellous saw for cutting timber on the root—an actual invention of Hamsun's. Not many years ago he replied in answer to a question in an enquête that the proudest achievement of his life was the invention of this saw, in the practicability of which he still had faith, although I believe it has never been perfected for actual use.

During the time when he ate and slept with servants and tramped the road with other day laborers, while observing the upper class from the vantage point of his own obscurity, Hamsun garnered a full sheaf of those curious and startling incidents by means of which he keeps his readers in a constant state of surprise. Meanwhile he did not forget his old ambition to become a poet. He felt the need of an education, and gradually worked his way southward to Christiania, where he entered the University.

The experiment was not a success. At that time the University was much more than now under the influence of old academic traditions, and did not welcome the rustic in search of knowledge as cordially as perhaps it would have done to-day. Moreover, the former cobbler and road-laborer was uncouth in his manner, bursting with loud-voiced opinions, and by no means filled with the proper reverence for authority. He soon realized that he was a misfit in University circles, and gave up the attempt in disgust. Of more benefit to him was a trip to the continent which he was enabled to make. After his return he went back to his old life on the road, but his intellect was more and more reaching out beyond the humble work by which he earned his living. Finally he made his escape and took passage to America.

In the early eighties, when Hamsun started out for America, the tide of Norwegian immigration was at its height. Not only were thousands and thousands of young men and women going across the sea to try to better their worldly status, but America had come to be looked upon as a spiritual as well as an economic land of promise. The poets, Björnson, Ibsen, Kielland, Jonas Lie and others were busy sending their heroes and heroines over there to find expansion of life or perhaps to come back and be the fresh, salty stream in the back waters of Norwegian narrowness and prejudice. We need only call to mind Lona Hessel in "Pillars of Society." Knut Hamsun had, of course, read these books, and when he started out for the New World he did not go merely as an immigrant to seek his fortune. He hoped to find those larger opportunities for leading his own life and using his gifts which the poets had been telling him about. He had bruised himself on Old World littleness; quite naturally he looked to the New World for bigger visions, ampler spaces, and a saner estimate of a man's worth. In this he was destined to be sorely disappointed. And yet some of the things he sought, and even more those he learned to value later in life, were there, but he failed to find them.

His dream of being a poet was still alive in him, and when he came to his countrymen in the Middle West he announced to a friend that he was going to write poetry for the Norwegian people in America. To one who knows the Middle Western settlements, there is something pathetic in this youthful ambition. God knows that if any one needs a poet it is the immigrant who is torn violently from his contact with the spiritual life of the old country and has not yet taken root in the new, but the Hamsun of that day had no message which his emigrated countrymen cared to hear. Like other immigrants they were absorbed in the task of building a new community, and when this work left them any leisure they preferred to sing the old songs and dream the old dreams of the fjælls and fjords. Immigrants are generally very conservative, and cling with all the fibres of their affection to the old melodies. They have little ear for any new voice that lifts itself among them. But the Middle West has never at any time had much use for the dreamer and visionary, and in Hamsun's day it was more than now a country of absorption in material things by as much as it was nearer pioneer times.

Hamsun soon found that in order to make his living he would have to work hard under conditions more distasteful to him than his old roving life in Norway. For a while he cherished a hope that he might be able to make his way in some manner more suited to his mental equipment. He came under the influence of a Norwegian writer and clergyman, Kristoffer Janson, of Minneapolis, who tried to make a Unitarian minister of him. But the faith that tries to modernize religion by eliminating its mystery could not long hold the imagination of one who sees mystery as the very life and essence of religion. In the diatribes on American intellectual life published after his return to Norway he paid his respects to Unitarianism in an essay on Emerson. He cared little for the Concord philosopher. Of the American poets he "could bear to read" certain parts of Walt Whitman, Poe, and Hawthorne, while he referred to our most beloved poet as "the somnolent Longfellow." In Minneapolis he tried to express his unflattering views on American literature in lectures, and hired Dania Hall for the purpose, but Americans of Scandinavian extraction are extremely quick to resent any attack on their adopted country, and refused to listen to him.

When we remember how sober and well draped was the verse of our great New England poets, we can hardly wonder that it failed to satisfy the young author who, a few years later, was to lay bare every quivering nerve of his being in "Hunger." Nor can we wonder that a young immigrant, forced to work hard in rough surroundings, should not have discovered the finest flowers of American culture. It is more remarkable that he who was destined to write the great epic of the pioneer farmer in "Growth of the Soil" should have failed utterly to see the real elemental soundness and vigor of the pioneer community in which he found himself, and that he should never have had his eyes opened to the many obscure Isaks toiling on Norwegian farms in the Middle West. Yet this too can easily be understood when we remember how he thirsted for the richer, subtler life of an old community and how little his thirst had yet been satisfied.

In his later books Hamsun has glorified any kind of work that has to do with practical realities and is done with a will. In his youth he learned by his own experience the deadening, brutalizing effect of toiling under the lash. He was initiated on the wheatfields of North Dakota, where production was carried on with swarms of day laborers. In the winter, on the grip of a Chicago street car, he suffered the hardships of long hours and low pay for uncongenial work. Finally he plumbed the lowest depths he was fated to know when he spent some miserable seasons on a fishing-smack off New Foundland.

Reminiscences of these years are found in a few short stories and sketches scattered through various volumes of his works. "Woman's Victory" a story in "Struggling Life" (1905) is based on his experiences in Chicago, and is prefaced by a paragraph which gives a vivid picture of this phase of his American adventures. It begins: "I was a street car conductor in Chicago. First I had a job on the Halstead line, which was a horse car line running from the centre of town to the cattle market. We who had night duty were not very safe, for there were many suspicious characters passing that way at night. We were not allowed to shoot and kill people, for then the company would have had to pay compensation. However, one is seldom wholly devoid of weapons, and there was the handle of the brake which could be torn off and was a great comfort. Not that I ever had need of it except once.

"In 1886 I stood on my car every night through the Christmas holidays, and nothing happened. Once there came a big crowd of Irishmen out of the cattle market and quite filled my car. They were drunk and had bottles along. They sang loudly and did not seem inclined to pay, although the car started. Now they had paid the company five cents every evening and every morning for another year, they said, and this was Christmas, and they were not going to pay. There was nothing unreasonable in this point of view, but I did not dare to let them off for fear of the company's 'spies' who were on the watch for lapses on the part of conductors. A policeman boarded the car. He stood there for a few minutes, said something about Christmas and the weather, and jumped off again when he saw how crowded the car was. I knew very well that at a word from the policeman all the passengers would have had to pay their fares, but I said nothing. 'Why didn't you report us?' asked one of the men. 'I thought it unnecessary,' said I, 'I am dealing with gentlemen.' At that there were some of them who began to laugh, but others thought I had spoken well, and they saw to it that everybody paid."

The author's North Dakota experiences are the subject of several short stories. "Zacchæus" in the collection "Brushwood" (1903) gives a vivid picture of life on Billibony farm, where work began at three in the morning and went on at a nerve-racking speed until the stars came out at night, and the only comic relief was the serving up to Zacchæus of his own finger in the stew. Yet Zacchæus who treasured this severed member of himself, and the cook who played the gruesome trick because Zacchæus had laid hands on his sacred "library" consisting of one old newspaper and a book of war songs, these were human compared to the creatures described in the sketch "On the Banks" in "Siesta" (1897). Never before or since has Hamsun drawn a picture of such stark and unrelieved hideousness as this description of eight men who were herded together on the boat regardless of race or color, whose chief pleasure was maltreating the fish they caught, and whose obscene talk and lewd dreams rise from the crowded forecastle like a loathsome stench. To the man of nerves and imagination who tells the story, the horror of the situation was deepened by the consciousness of the hostile powers of nature lying in wait out there on the sea which closed around him everywhere and of the unseen monsters in the deep trying to hold what is their own while the men tug frantically at the nets. This sense of being surrounded by hostile forces is very unusual with Hamsun, who generally loves to dwell on the friendliness of nature.

With these months on the fishing banks, the cup was full. Hamsun made up his mind that his wanderings must end and his real work begin, no matter at what cost. He took passage home on a Danish steamer, and came to Christiania in 1888, determined to make his way by writing. He was not wholly unknown in the editorial offices of the city. He had been back in Norway between the years 1883 and 1886, when he had attempted to give lectures on literature, though not with much more success than that which attended his efforts in Minneapolis. During his second sojourn in the United States he had written some correspondences to Norwegian papers.

Before beginning his serious literary work, Hamsun threw off at white heat a book entitled "Intellectual Life in Modern America" (1889). It is full of prejudice and misinformation: arraignment of American culture after following resplendently attired servant girls on the street and listening to their conversation (just as Kipling did); moralizings about the divorce evil based on the stories in sensational newspapers without the slightest knowledge of good American home-life; condemnation of our art museums and opera houses as temples of Mammon, and much more of the same kind. Yet the scathing satire of the book, though biased, does not always miss its mark. Hamsun's shrewdness had penetrated to the weakness of American civilization, its externalism, its materialism, its dryness and shallowness. We may also admit that his American experiences fell in a period of little intellectual vitality, when the great New Englanders had been relegated to school declamations, and the modern quickening of liberal thought was yet far distant.

One thing, at least, must be set down to Hamsun's credit. He did not, like many lesser writers from across the sea, fall into the cheap and easy task of ridiculing the simple people of the frontier or making fun of his own countrymen in their uncouth efforts to Americanize themselves. His shafts were always aimed at that which passes for the highest in American civilization. Here as in his later onslaughts on Ibsen and Tolstoy, his audacities loved a shining mark.

There are only a few scattered references in the book to the Norwegian immigrants in this country, and these are full of sympathetic comprehension of their difficulties. This fact, however, has not prevented "Intellectual Life in Modern America" from being a stumbling block and an offense to Americans of Norwegian extraction. It has been one of the main factors in preventing for many years the recognition of his genius among them.

In this connection I recollect the first and only time I have seen Knut Hamsun. It was in 1896, on my first visit to Norway, when I met him at the home of my relatives, and I can well remember how my own youthful prairie patriotism resented his attacks on the country my parents had made their own. As I think of him at this distance of years, with tolerance for his views on America, with charity for other things not acceptable to the staid household of which I was a member, I remember him as a man of distinguished presence, still in the flush of young manhood. He was distinctly of the fair, virile type met in the eastern mountain districts where he was born, tall, broad-shouldered, with a particularly fine profile and well-shaped head which he carried in a regal manner. He was then at the height of his early fame.

Knut Hamsun, like more than one other Norwegian genius, won his first recognition in Denmark, where he spent a few months after his return from the United States. Edvard Brandes, at that time editor of the Copenhagen daily "Politiken," has told a story of a young Norwegian who one day presented himself at the office with a manuscript. The editor was about to refuse it on the ground of unsuitable length, when something in the appearance of the stranger made the refusal die on his lips. It was the shabbiest, most emaciated figure that had ever crossed the editorial threshold, but there was something in the pale, trembling face and the eyes behind the glasses that moved the editor in spite of himself. He took the manuscript home with him and began to read it. As he read the story of the starving young genius, it dawned on him with a sense of shame that the writer was probably at that moment without the means of subsistence. Hastily he enclosed a ten krone bill in an envelope, addressed it to the place the unknown author had given as his residence, and ran to the station to mail it. Then he returned and read on to the last paragraphs, where the hero is stealthily crawling up to his room, afraid to rouse a wrathful landlady, and is moved to a delirium of joy by the receipt of a letter containing a ten krone bill sent him by an editor—ten kroner being the highest pitch of opulence to which Hamsun ever carries his hero.

In telling the coincidence that same evening to a Swedish critic, Axel Lundegård, who has published the story, Brandes spoke of how the manuscript had impressed him. "It was not only that it showed talent. It somehow caught one by the throat. There was about it something of a Dostoievsky."

"Was it really so remarkable?" asked Lundegård. "What was the title of it?"

"Hunger."

"And the author?"

"It was the first time I heard the name Knut Hamsun," writes Lundegård, "and the first time I heard the phrase 'something of a Dostoievsky' used about any of his books. Since then it has become a commonplace, but applied to the first production of a young author by a critic not at all given to over-enthusiasm, it was a tribute."

Through the influence of Edvard Brandes the manuscript, which contained the first chapters of the book "Hunger," was placed with a new radical Copenhagen magazine, "New Soil." This was in 1888. The story was anonymous, but it attracted attention by its exotic brilliance of style and by the intensity which up to that time had been unknown in Northern literature. Rumors of its authorship were current, and were confirmed when, in 1890, the book "Hunger" burst upon a startled Christiania and made its author instantly famous.

In the intervening time Hamsun had gained some notoriety in his own country by the publication of "Intellectual Life in Modern America." Although he had thus trumpeted forth his failure to find any stirring of the intellect whatever in the great American republic, the Norwegian critic Sigurd Hoel attributes the style of "Hunger" to American influence. It had a daredevil humor, a dash and verve, and a feeling for effect that certainly had no precedent in the respectable annals of Norwegian literature.

"It was the time when I went about and starved in Christiania, that strange city which no one leaves before it has set its mark upon him,"—so runs the oft-quoted first sentence in "Hunger." There is no reason why it should have been Christiania. It might as well have been the American brain market, New York, or any other city where men and women try to sell the product of their brains and learn that their finest thoughts and highest efforts are not of the slightest consequence to anybody. Hundreds of men and women have fought the fight to which he has given classic expression. They will recognize his astonishment as it dawned upon him that although he had "the best brain in the country and shoulders that could stop a truck," there was no place for him in the great machine that ground food for the dullest and stupidest. They will know the bending of the neck and the sagging of the spirit, the hysterical swinging between absurd pride and shameless grasping at any opportunity, the agonized striving to catch the eye and ear of an indifferent world by strained and overwrought work, the impotent sense of never being able to begin the fight on equal terms.

Few, however, have dared to follow the experiment to the uttermost ends of destitution. Few have explored the abysses of suffering through which Hamsun leads his hero. At one time he tried to bully a poor frightened cashier into stealing five öre (a little over a cent) from the cash drawer so that he could buy bread with it. Another time he refused the offer of an editor to pay him in advance for an article not yet written. Once he suddenly decided to beg the price of a little food from some big business man whose name had suddenly come into his head with the force of an inspiration, and persisted, humiliating himself to the depths, holding his ground till he was practically thrown out. Another time, when he himself had starved for days, he pawned his vest to get a krone to give a beggar. It is just such absurdities and inconsistencies that people commit when the starch of everyday habits has been washed out of them.

He keeps back nothing in his story. He even relates with grim humor an encounter with a girl of the streets who in pity offers to take him home with her although he has no money, while he simulates virtue to conceal his abject state: "I am Pastor So-and-so. Go away and sin no more." But his realism does not consist merely in dragging out into the light the acts that others commit in the dark. One need not be a genius to do that. No, he plumbs below action, below even conscious thought and feeling, to those erratic impulses that would make criminals or maniacs of us all if we followed them, not only the great overmastering passions that have their place in the Decalogue, but all the fitful whims and inconsequential trifles that influence conduct. It is as though the delirium of hunger had released all that which is usually controlled by will or custom. Sometimes, when he has starved for days, he can feel his brain as it were detaching itself from the rest of his personality, going its own way, manufacturing idiotic conceits, which he knows to be idiotic, but can not stop. Yet all the time his other consciousness is sitting by, holding the pulse of his delirious imagination and recording its antics.

The light, whimsical touch rarely fails him, but occasionally there are passages of a sombre and thrilling pathos, as the following: "God had thrust His finger down into the tissue of my nerves and gently, quite casually, disarranged the fibres a little. And God had drawn His finger back, and behold, there were shreds and fine root filaments on His fingers from the tissue of my nerves. And there was an open hole after the finger which was God's finger and wounds in my brain where His finger had passed. But when God had touched me with the finger of His hand, he left me alone and did not touch me any more."

Hamsun as a Young Man

Hamsun as a Young ManOnce he cursed God. He had begged a bone of a butcher under pretense of giving it to his dog, and hid it under his coat until he came to a doorway where he could take it out and gnaw it. But the noxious bits came up again as fast as he could swallow them, while the tears streamed from his eyes, and his whole body shook with nausea. Then he screamed out his imprecations: "I tell you, you sacred Ba'al of heaven, you do not exist, but if you did I would curse you so that your heaven should tremble with the fires of hell. I tell you, I have offered you my service, and you have refused it, and I turn my back on you forever, because you did not know the time of your visitation. I tell you that I know I am going to die, and yet I scorn you, you heavenly Apis, in the teeth of death. You have used your power over me, although you know that I never bend in adversity. Ought you not to know it? Did you form my heart in your sleep? I tell you, my whole life and every drop of blood in me rejoices in scorning you and spitting on your grace. From this moment I renounce you and all your works and all your ways; I will curse my thought if it thinks of you and tear off my lips if they ever again speak your name. I say to you, if you exist, the last word in life or in death—I say farewell." But the imp of irony, which in Hamsun is never far away, is peeping over his shoulder as he writes, and the blasphemies are hardly cold on the page before he tells himself that they are "literature." He is conscious of forming his curses so that they read well. This outburst stands alone in his works. It is as though in "Hunger" he had once for all rid himself of all the accumulated rage and agony of his youth. They never come again.

The book is without beginning and end and without a plot, but it has a series of climaxes. Each section describes some phase of hunger and its attendant sufferings: the physical deterioration and weakness, the rebellion of spirit, the hallucinations, the shame and degradation. When the strain becomes intolerable, the tension suddenly snaps with the receipt of five or ten kroner, and then Hamsun instantly removes his hero from our sight. We never see him in the enjoyment of this comparative opulence, but when the money is gone, we meet him again beginning the old struggle, though each time weaker and more unfit to take up the fight. He never achieves anything; his small successes in occasionally selling a manuscript never lead to anything. The book is a record of defeat and frustration which have at last become inevitable because something in himself has given way. Even his strange love affair with the girl whom he calls Ylajali ends in baffled disappointment.

Finally Hamsun simply cuts the thread of the story by letting his hero ship as an ordinary seaman in a boat that is going to England. He leaves the city he had set out to conquer. The city has conquered him. "Out in the fjord I straightened up once and, drenched with fever and weakness, looked in toward land and said good-bye for this time to the city of Christiania, where the windows shone so brightly in all the homes."

The most adequate idea of Hamsun's artistic personality can be gained by reading his early works from "Hunger" to "Munken Vendt" and preferably reading them in the order of their appearance.

Through the medley of characters there emerges a distinct type that can be traced in one after the other of his early books but disappears in the later, more objective, pictures of whole communities. This person is at first always the hero in whom everything centres; later he steps into the background as an onlooker who is sometimes the author's spokesman. He is always a dreamer and one who stands outside of organized society; but this aloofness is not self-sought. On the contrary, he often suffers in his loneliness, and is longing and struggling to come within the circle of human fellowship, but there is something in his own nature which unfits him to be a cog in the common machinery. His pulses are differently attuned from those of other people. The standards by which happiness and success are usually measured mean nothing to him, but he can be lifted to exaltation by the fragrance of a flower or the humming of an insect. He is often a poet, if not in actual production at least in his temperament, and has the poet's responsiveness to things that more thick-skinned people do not notice. An ugly face, a jarring noise can shiver his highest mood like crystal and plunge him to the depths of despair. A sour look or an unkind word or even a trifling mishap—the loss of a lead pencil when he is inspired to write—can cast a gloom over his day. He is full of generous impulses which sometimes take erratic forms and is capable of carrying self-sacrifice to the most senseless extreme, but his nature has never a drop of meanness. He revels in communing with nature and finds pleasure in the society of some lowly friend or simple, loving woman, but any happiness that life may bring him is never more than a momentary gleam. He never lives to his full potentiality either in achievement or in passion. The Swedish critic John Landquist puts the question why we never tire of this oft-repeated Hamsun hero any more than of his Swedish cousin Gösta Berling, and answers that it is because he never gains anything and never turns any situation to his own advantage.

There is no doubt that this constantly recurring figure is Hamsun himself in one incarnation after another. He has pointed the connection by personal description, by reference to his authorship, and once even by the use of his own name. He has to a greater extent than most creative artists drawn for his subjects on his own varied experiences, and though he has of course transmuted them in his imagination, it is clear that he has at least been near enough to the events he records to have lived through them very intensely in his own mind. This is, of course, notably true of "Hunger," which was written at the age of thirty, when his own experiences as a journalistic free lance in Christiania were still fresh in his mind. It is true also of "Mysteries," "Pan," and "Victoria," each one of which corresponds to some phase in his own development. In "Munken Vendt" and "Wanderers" there are reminiscences from his vagabond days, and it is significant of the subjectivity with which he enters into the person of his hero that in the latter he has chosen to make the narrator a man of his own age at the time of writing rather than reincarnate himself in the image of his youth. In the earlier books, on the other hand, the hero is always young, generally between twenty-five and thirty.

The Hamsun ego as the critic of contemporary phenomena, the outsider who is unable to fit himself into any clique or party, appears in Höibro of "Editor Lynge," who is carried over into the drama "Sunset," and in Coldevin of "Shallow Soil." He is absent from all the author's later, more objective, novels, "Dreamers," "Benoni," "Rosa," "Children of the Age," "Segelfoss City," and "Women at the Pump," but we may perhaps find a shadow of him in Sheriff Geissler of "Growth of the Soil," the garrulous wiseacre who "knew what was right, but did not do it."

The typical traits of the young Hamsun hero are found in the highest degree in Johan Nagel. The central figure of "Mysteries" (1892) is a reincarnation of the nameless narrator of "Hunger," a few years older, gentler, but no less erratic, and even more sensitive. There is about him a great lassitude, an indifference to his own advancement in life, which might easily be the aftermath of great suffering and terrible struggles. He seems to have no purpose of any kind. He steps ashore one day in a small Norwegian seacoast town simply because it looks so pleasant to a returned wanderer, and there he remains, startling the inhabitants by his odd manners and freakish garments. There is an exquisite goodness in Nagel. His attitude is no longer that of the clenched fist. He tries to win his way into the fellowship of his neighbors by acts of quixotic generosity—which another impulse leads him to cover up. He takes infinite pains to find opportunities of giving pleasure to the outcasts of the community without letting them know whence the bounty comes. He loves to decoy a beggar into a doorway and bestow a large sum upon him with strict injunctions to secrecy. He has in the highest degree the sweetness and longing for affection which is a leading trait in all the Hamsun heroes, though least apparent in the youngest of them, the narrator of "Hunger;" but he has also in a superlative degree their unfitness for the common affairs of men. Consequently he suffers the fate of those who would do good as it were from the outside without being a part of the community for which they would sacrifice themselves: his efforts fall fruitless to the ground.

Into this book Hamsun has introduced a curious parody of the hero, a little wizened cripple who is like a deformed reflection of Nagel. This poor devil carries goodness, meekness, and long-suffering to a point where it merely rouses the beast in the respectable citizens of the small town and draws on himself brutal persecution; but underneath his real goodness there is some abyss of evil which we are not allowed to fathom, but which Nagel understands by a strange intuition. His efforts to warn and save his protegé are unavailing. Unsuccessful too are his efforts to win the confidence of Martha Gude to whom he turns for consolation when Dagny rejects his love. Nagel is an artist nature, and in the latter part of the book he is revealed as a violinist with at least a touch of real genius, but he has been thoroughly disillusioned regarding himself and his art. He will not be one of the swarm of little geniuses or cater to the beef-eaters. Whatever possibilities of achievement still lie dormant in him are completely destroyed by his unhappy love affair.

Written at a time when Hamsun from the lecture platform was carrying on a campaign against the older poets and the established literary standards, "Mysteries" is made the vehicle of many iconoclastic opinions, and Nagel is to a greater extent than most of his heroes made the mouthpiece of the author's views. In long rambling talks, sometimes carried on with himself as sole audience, he attacks Ibsen, Tolstoy, Gladstone, and other great names of the day. In the books immediately following "Mysteries," "Editor Lynge" and "Shallow Soil," Hamsun continues his attacks on the ideals of the day, though in them he directs his blows rather at the small imitators of the great.

The Hamsun hero in his relation to nature appears in "Pan" (1894). Lieutenant Glahn, the central figure of the book, is a hunter who has lived in the forest until he has himself taken on something of the nature of an animal in the look of his eyes and in his manner of moving. He is supremely happy in his hut. His senses are saturated with the warmth of summer days, the fragrance of roots and trees, the soughing of the woods, and the tiny noises of all the things that live in the forest. His spirit rests in the sense that in nature all things go on, tiny streamlets trickle their melodies against the mountainside though no one hears them, the brook rushes to the ocean, and everything is renewed each year regardless of human fates. With the outdoor life comes the primitive love of shelter which we lose in cities; a warm sense of home ripples through his whole being when he returns to his but in the evening, and he talks to his dog about how comfortable they are.

Glahn has found peace in the forest, but this peace is shattered as soon as he comes in contact with his fellowmen. Awkward and uncouth, he is unable to comport himself with dignity even in the little group of merchants and professional men that constitute society in a Nordland fishing village. He is too proud and simple to cope with the caprices of the woman he has fallen in love with, and she soon tires of him. Then Glahn, moved by a childish desire to make her feel his existence even though it be only by a big noise, arranges a rock explosion, and this foolish feat accidently kills the only person who really loves him, the simple woman whom he has met in the forest. Against his misery now nature, which a few weeks earlier was all in all to him, has no remedy.

Between the appearance of "Pan" and "Victoria" (1898) lay a period of productive work resulting in the publication of the dramatic trilogy centering in the philosopher Kareno and a volume of short stories entitled "Siesta." The increasing success of Hamsun's own authorship set its stamp on the next incarnation of his hero, Johannes, the miller's son in "Victoria" who becomes a poet. Johannes is the only one of all his youthful heroes who is fundamentally a harmonious nature and the only one who masters life. The opening paragraph of the book is like a happier reflection of Hamsun's own dreamy, lonely boyhood. "The miller's son went around and thought. He was a big fellow of fourteen years, brown from sun and wind and full of ideas. When he was grown up he was going to be a match manufacturer. That was so deliciously dangerous, he might get sulphur on his fingers so that no one would dare to shake hands with him. He would be very much respected by the other boys because of his dangerous trade." Johannes knows all the birds and is like "a little father" to the trees, lifting up their branches when they are weighed down by snow. He preaches to a congregation of boulders in the old granite quarry, and stands dreaming over the mill dam, following the course of the bubbles as they burst in foam. "When he was grown up he was going to be a diver, that's what he was going to be. Then he would step down into the ocean from the deck of a ship and enter strange kingdoms and lands where marvellous forests were waving, and a castle of coral stood on the bottom. And the princess beckons to him from a window and says, 'Come in!'"

Just as Hamsun's own dreams are echoed in this boyish imagery, so his own authorship in its happiest time when he felt all his powers in full swing, is reflected in the later story of Johannes. Between the rude hunter of "Pan" and the poet of "Victoria" there is a lifetime of development. Johannes is just as impulsive and irrepressible as the other Hamsun heroes he is quite likely to burst into loud song in the middle of the night and disturb the neighbors, if a happy idea strikes him, but he has really found himself in his work. Johannes is loved by the young lady of the manor with a love that is strong enough for death, but not strong enough for life. He loses her, but the loss does not blight his life. The great emotion she has given him remains with him to deepen and enrich his nature and to become the life-sap of his blossoming genius.

Very different from the miller's son and yet of the same family is the happy-go-lucky swain who gives his name to the dramatic poem "Munken Vendt" (1902). It is to some degree reminiscent of "Peer Gynt" both in the verse form and in the chief character; but while Ibsen wrote a bloody satire of the worst qualities in his race, Hamsun has drawn a lovable vagabond. Munken Vendt is a student and hunter whose adventures take place in some Norwegian valley at a period not definitely fixed, but certainly much more romantic than the present. He is something of a poet, is clever but unable to turn his gifts to his own advantage, is clothed in rags but always with a feather in his cap and ready to give away his last shirt, wins sweethearts wherever he goes but fails the woman who should have been his mate, and finally throws away his life in a senseless extravagance of self-sacrifice. There is about Munken Vendt, for all his foolishness, a proud defiance of suffering, a noble pathos, a bigness and elevation of thought, which give his portrait a distinctive place in the Hamsun gallery.

The books I have mentioned here are generally regarded as the most individualistic of Hamsun's works and as those that reveal his personality most intimately. Among them should be counted also "The Wild Chorus" (1904), a slender volume of poems which, with "Munken Vendt," constitute all that he has written in metrical form. While Hamsun is most at home in poetic prose, his poems have a wild, fresh charm and are intensely personal expressions of his views on the two subjects that engage him most deeply: love between man and woman and love of nature.

A veritable Shakespearean gallery of women, drawn with subtle insight and delicate sympathy, is found in Hamsun's works. Though infinitely varied in their personalities, they move within certain limits and have certain traits in common. They are intensely feminine with the nervous fitfulness and spasmodic capriciousness that go with overwrought sexual sensibilities. Occasionally he carries a woman through this phase in her life into a warm and passionate motherliness, but never into a finer and more complex individual development. All his heroines have in the highest degree the unfathomable lure of sex, but what they are above and beyond this we never learn.

The limitation may be less in the heroines themselves than in the medium through which we are allowed to see them. If it were possible to mention in the same breath two such antipodes as Jane Austen and Knut Hamsun, I might recall what has been said of her that she never attempts to tell us how men talk when they are away from the presence of women. He never describes a woman when she is alone. We are never allowed to be present when his heroines commune with their own thoughts; we never see them from their own point of view and but rarely from that of a mere observer. We glimpse only so much of them as they reveal to their lovers, and while in this way they never lose the glamour and mystery with which they are surrounded, it is inevitable that they will seem members of a common sisterhood, inasmuch as their lover, the Hamsun hero, is always the same.

In the character of Edvarda in "Pan" the qualities of the Hamsun heroine are heavily underscored. She is a wayward girl with erotic instincts early awakened and with a flighty imagination which sets her lovers absurd tasks, and yet there is a certain sweetness and a primitive freshness about her that attract in spite of better judgment. Her curiosity is roused by Glahn, the hunter with the "eyes like an animal's"; she invites him to her father's house and draws him into their social circle. At a picnic she suddenly flies at him and kisses him in the presence of the assembled village, and after this outburst she meets him constantly, circles around his hut by night, and kisses his very footprints. But in a few days her violence has exhausted itself; she stays away from their trysts; she insults and ridicules him in her own home as publicly as she has formerly favored him, and before many weeks have passed, she has engaged herself to another man. Yet her love for Glahn is real, and presently she makes frantic attempts to get him back. Glahn's stubborn resistance is the measure of the suffering she has inflicted upon him, and when at last she begs him to leave his dog Æsop with her when he departs, he shoots his four-footed friend and sends her the body. He seeks consolation with other women, and there is much sweetness in his relation with Eva, the simple daughter of the people, but in spite of her humble, unquestioning devotion and his real tenderness for her, his feeling never touches the heights or the depths. Even when he is with her, the thought of Edvarda is like a constantly smarting wound. Yet he continues to resist Edvarda's advances. When after the lapse of some years she tries to call him back, he pretends to himself that he does not care, but he goes away to the Indian jungle and seeks death.

Edvarda reappears in a subsequent novel "Rosa," a torn and lacerated soul, forever unsatisfied, with strange gleams of generosity alternating with petty cruelty. She owns that there have been some moments in life not so bad as others, and chief among these to her was the time when she was in love with the strange hunter. In her desperate longing for something that will take her out of herself, she has spasms of religion, but at last sinks to the level of having an erotic adventure with a Lapp in the forest and worshipping his hideous little stone god.

A repellent creature in many ways is Edvarda, and yet the author has managed to make us feel her through the perceptions of her lover, who sees—shall we say a figment of his imagination or the real Edvarda? Behind her flagrant coquetries he discerns a fount of purity: "She has such chaste hands." Her girlish affectations, even her clumsiness, have for him a kind of appeal as of something naïve and helpless. Glahn and Edvarda are both essentially and deeply primitive though afflicted with a blight of sophistication. Each answers to a profound need in the other; each has for the other that one supreme thing which is higher and deeper than virtue and wisdom and which no one can give in its full intensity to more than one person out of the world of men and women. Both know that it is so, and yet something in themselves prevents them from giving and receiving that which both long for with undying fervor. Glahn's passion is strong enough to ruin his life, but it is after all not strong enough to hold fast through good and bad, in happiness and unhappiness, and win from the relation the fullness of life which no one but Edvarda could give him. The conflict of love which Hamsun so often describes is here present in the most clearcut form because there is nothing outwardly to divide the lovers. Their tragedy is entirely of their own making.

Dagny in "Mysteries" is superficially a much more attractive young woman than Edvarda. She is the clergyman's daughter, sweet and blithe, with a big blond braid and a habit of blushing when she speaks. All the village loves her, and we can easily imagine her visiting the sick and befriending the poor. But Dagny is a far more inveterate coquette than Edvarda. While Edvarda was moved by her own thirst for excitement and longed rather to be herself subjugated than to subjugate others, Dagny is a deliberate flirt who can not bring herself to release any man once she has him in her power. Whether she loves Nagel or not he does not know, nor does the reader. She weakens for a moment under the force of his passion, but she holds fast to her purpose of marrying her handsome and wealthy fiancé, although she intrigues to prevent Martha Gude from giving Nagel what she herself withholds. That his death for her sake shakes her nature to its depths we learn when we meet her again in "Editor Lynge," where she owns to herself that at one word more she would have given up everything and thrown herself on his breast.

This one word Nagel never speaks. Like the hero of "Pan" he seeks the haven of another woman's tenderness. He yearns toward Martha Gude with all his heart, longs for the peace and rest and purity she could have brought into his life, and yet he can not tear himself loose from the passion that binds his soul and senses. Even while he is pleading with Martha and tries to win her confidence in a scene drawn with tender delicacy, his thoughts are with Dagny, and when at last he has won Martha's shy promise, he rushes out into the night to whisper Dagny's name to the trees and the earth. The love which gushes forth irrepressibly from some unquenchable fountain in the soul, which wells out again and again, warm and fresh, however often its outlet is clogged and muddied, this love Hamsun has often pictured and seldom with more tragic force than in the unhappy hero of "Mysteries." And yet, great and real as his love is—great and real enough to send him to his death—it is not perfect. It is poisoned by a lingering doubt, which prevents him from putting forth the one last effort that would have broken down Dagny's resistance.

The lovers in Hamsun's books are never at peace. They never know the quiet, gradual opening of heart to heart or the intimate communion of perfect sympathy. With them the conflict always goes on. Gunnar Heiberg, the Norwegian dramatist, has said that there is no such thing as mutual love, because no two people ever love each other simultaneously. When one has grown warm, the other has grown cold; and when one advances, the other instinctively recoils. With Hamsun the conflict is more fine-spun than that which Heiberg has painted rather crassly. The mutual love is there, but it is a thing so wild and shy and sensitive that it shrinks back into the dark at a touch even from the hand of the beloved. Or is perhaps the human soul so jealous of its freedom that it reacts against having another individuality fasten upon it even in love?

It is these intangible forces rather than the outer facts that divide the lovers in "Victoria." Victoria is the patrician among Hamsun's heroines, not only because of her birth and breeding, but by virtue of her character. She is far too noble for deliberate coquetry, and yet she tortures Johannes by an apparent capriciousness that seems out of keeping with her frank, generous nature, while he answers with coldness and hauteur. Why? Victoria has the secret, agonizing consciousness of the promise she has given her father that she would marry a wealthy suitor who can retrieve the fallen fortunes of the family. Johannes feels his own humble birth and his distance from the princess of his dreams. Yet these reasons seem hardly sufficient. It is difficult to imagine that battered old aristocrat, Victoria's father, forcing his daughter into an unhappy marriage to save his home, still more difficult to picture the mother, who knows everything, leading her daughter to the sacrifice. Moreover, Johannes, though of humble birth, has won fame and has developed into a man of substantive personality. He is not only Victoria's lover but her playmate and oldest friend and a favorite of her parents. In fact the sweetness in the relation between cottage and manor is one of the things that entitle "Victoria" to its reputation as the most idyllic among its author's works. Why then do not these four people face the situation together? Why does not at least Victoria talk it over with her lover? Afterwards she writes that she has been hindered by many things but most by her own nature which leads her to be cruel to herself. But the real reason is that Hamsun's art at this stage of his development has no use for fulfillment. With fulfillment comes indifference. It is his to paint the unslaked thirst and the unstilled longing. Therefore the wonderful letter in which Victoria lays bare her heart is not sent until after her death, and therefore she leaves Johannes the legacy of a great tragic feeling which is forever alive and throbbing because it is forever unsatisfied.

Mariane Holmengraa in "Segelfoss City" belongs with Hamsun's young heroines. She has some traits both of Edvarda and of Victoria. But in this much later book the author has begun to take a godfatherly attitude toward his young hero and heroine; their sparring is playful rather than tragic, and he leaves them at the entrance to what promises to be a happy-ever-afterwards.

In "Munken Vendt" the man's waywardness and the woman's pride divide the two who should have belonged to each other. When Iselin, the great lady of Os, stoops to befriend the vagabond student, he tells her brutally that he has no use for her kindness and does not love her. Many years later, when he returns after a long absence, he again rejects her advances. In revenge Iselin orders him to be bound to a tree with uplifted arms until the seed in his hand has sprouted. Munken Vendt bears the torture without a murmur and curses those who would release him before she gives the word, but his hands are crippled by the ordeal, and, partly in consequence of his helplessness, he meets death not long after by an accident. Then Iselin walks backward over the edge of a pier and is drowned. Here the conflict, which appears more veiled in Hamsun's other books, is clearly expressed in terms of savage, impulsive actions possible only in a primitive state of society.

A relation of perfect trust and harmony is that of Isak and Inger in "Growth of the Soil." From their elemental community of interest develops a really beautiful affection, which Inger's straying from the straight path can not long disturb. It is almost as though the author would say: So simple and so primitive must people be in order to make a success of marriage for the complex and the sophisticated there is no such thing as happiness in love. A similar lesson might be drawn from "The Last Joy" where Ingeborg Torsen, a teacher, after various adventures, marries a peasant and becomes happy in sharing his humble work and bearing his children.

The rebellion of a man against the monotony of marriage has been presented again and again by writers great and small from every possible angle. The inner revolt of a woman against the concrete fact of marriage, even with the man she has herself chosen, has not often been pictured, and rarely with the sympathetic divination that Hamsun brings to bear on the subject. Puzzling and contradictory, but very interesting is, for instance, Fru Adelheid in "Children of the Age." She is a woman with a cold manner but with a warmth of temperament revealed only in her voice. At first we do not know whether she is attracted to her husband or repelled by him until she reveals that she has simply reacted against his air of possession. Her husband, the "lieutenant" of Segelfoss manor, knows that his wife has enthralled his soul and senses and that no other woman can mean anything to him, but he can not bring himself to try to patch up what has been broken. Here we have the conflict between two people of maturer years who wake up one day to the realization that it is too late. Life has passed them by and can never be recaptured.

In "Wanderers" the disintegrating influence in the marriage of the Falkenbergs is habit that breeds indifference, and Fru Falkenberg, one of Hamsun's most poignantly beautiful and most unhappy heroines, is of too fine a caliber to survive the bruise to her self-respect. In "Shallow Soil" Hanka Tidemand is drawn by the false glamour of genius which surrounds the poet Irgens, and regards her husband as nothing but a commonplace business man. Here, however, the strength and depth of the man's love saves the situation. In its happy ending their story is unique among the author's earlier works.

Among his many wayward heroines Hamsun has painted one woman of calm and benignant steadfastness, Rosa, the heroine of the two Nordland novels, "Benoni" and "Rosa." She is so deeply and innately faithful that she not only clings for many years to her worthless fiancé and finally marries him, but even after she has been forced to divorce him and has been told he is dead, she feels that she can "never be unmarried from" the man whose wife she has once been. It is only after he is really dead and after her child is born that she can be content in her marriage with her devoted old suitor, Benoni. Then the mother instinct, which is her strongest characteristic, awakens and enfolds not only her child but her child's father. Quite alone in the sisterhood of Hamsun heroines stands Martha Gude, a spinster of forty with white hair and young eyes and a child heart. Her goodness and her purity, which has the dewy freshness of morning, draw Nagel to her, although she is twelve years older than he.

Side by side and often intermingled with the ethereal delicacy of his love passages, Hamsun has many pages of such crassness that often, at the first reading of his books, they seem to overshadow and blot out the fineness. He treats the subject of sex sometimes with brutal Old Testament directness, sometimes with a rough, caustic humor akin to that of "Tom Jones" or "Tristam Shandy," but never with sultry eroticism or with innuendo under the guise of morality. There is in his very earthiness something that brings its own cleansing, as water is cleansed by passing through the ground. Probably most of us would willingly have spared from his pages many passages in "Benoni" and "Rosa," "The Last Joy," and more especially in his last book "Women at the Pump," and even in "Growth of the Soil," but they all belong to the author's conception of a true picture of life.

"What was love?" writes Johannes in "Victoria." "A wind soughing in the roses, no, a yellow phosphorescence. Love was music hot as hell which made even the hearts of old men dance. It was like the marguerite which opens wide at the approach of night, and it was like the anemone which closes at a breath and dies at a touch.

"Such was love.

"It could ruin a man, raise him up, and brand him again; it could love me to-day, you to-morrow, and him to-morrow night, so fickle was it. But it could also hold fast like an unbreakable seal and glow unquenchably in the hour of death, so everlasting was it. What then was love?

"Oh, love it was like a summer night with stars in the heavens and fragrance on earth. But why does it make the youth go on secret paths, and why does it make the old man stand on tiptoe in his lonely chamber? Alas, love makes the human heart into a garden of toadstools, a luxuriant and shameless garden in which secret and immodest toadstools grow.

"Does it not make the monk sneak by stealth through closed gardens and put his eye to the windows of sleepers at night? And does it not strike the nun with foolishness and darken the understanding of the princess? It lays the head of the king low on the road so that his hair sweeps all the dust of the road, and he whispers indecent words to himself and sticks his tongue out.

"Such was love.

"No, no, it was something very different again, and it was like no other thing in all the world. It came to earth on a night in spring when a youth saw two eyes, two eyes. He gazed and saw. He kissed a mouth, then it was as if two lights had met in his heart, as a sun that struck lightning from a star. He fell in an embrace, then he heard and saw nothing more in all the world.

"Love is God's first word, the first thought that passed through his brain. When he said: Let there be light! then love came. And all that he had made was very good, and he would have none of it unmade again. And love became the origin of the world and the ruler of the world. But all its ways are full of blossoms and blood, blossoms and blood."

The fervent love of nature which vibrates through everything Hamsun has written has endeared him to many of his countrymen who are repelled by his eroticism and out of sympathy with his social theories. The lyric rhapsodies in "Pan" minister to a deep and real craving in the Norwegian temperament, and it is not for nothing that this book has steadfastly held its own as the first in the affections of the public. "Fair is the valley; never saw I it fairer," said Gunnar of Hlidarendi in "Njal's Saga," when he turned from the ship he had made ready to carry him away from his Iceland home, and went back to face certain death there rather than save himself by banishment. To the Northerner, whether he be Icelander, Swede, or Norwegian, natural environment is the determining influence in the choice of his home; and not only the poet and artist but the average middle class individual, clerk, teacher, or store-keeper, will forego social life and endure much discomfort in order to establish himself in a place where he can satisfy the love of beauty in nature which is one of the strongest passions in the Northern races. And yet, however fair the valley of his home, he will yearn to get away from it sometimes, to rove alone on skis over the snowfields or bury himself in a forest hut far from the sound of a human voice. The vast uncultivated stretches of Norway have enabled the people to follow their bent and seek outdoor solitude, and while the habit has not fostered in them the pleasant urban virtues of nations that live more in cities, it has developed a richness and intensity of inner life which has flowered vividly in their art and literature.

The solitary hunter of "Pan" is perhaps the most typically Norwegian among the Hamsun heroes, and in him love of nature has deepened into a veritable passion. This book, which followed several novels of city and town life and was written during a summer in Norway after a sojourn abroad, is the first full-toned expression of Hamsun's feeling for nature. It has a melting tenderness and a warm intimacy of knowledge which can only come from much living out of doors, as the author did when he herded cattle as a boy, and later when he roved through the country as a vagrant laborer. To read it is like nothing else but lying on your back and gazing up to the mountains until you feel the breath of the forest as your own breath and sense no stirring of life except that which sways the trees above you. The feeling of being one with nature, of enfolding all things with affection and being oneself enfolded in a universal goodness, is typical of Hamsun's attitude. He never paints nature merely as the scenic background for his human drama, and he never romances about nature for its own sake. He rarely describes in detail; it is as though he were too near for description. Like a child which buries its face on its mother's breast and does not know whether her features are homely or beautiful, he seems to be hiding his face in the grass and listening to the pulse-beats of the earth rather than standing off and looking at it. "I seem to be lying face to face with the bottom of the universe," says Glahn, as he gazes into a clear sunset sky, "and my heart seems to beat tenderly against this bottom and to be at home here." Nothing is great or small to him. A boulder in the road fills him with such a sense of friendliness that he goes back every day and feels as though he were being welcomed home. A blade of grass trembling in the sun suffuses his soul with an infinite sea of tenderness.

"Pan" is full of lyric outbursts. When Glahn revisits the forest on the first spring day, he is moved to transports. He weeps with love and joy and is dissolved in thankfulness to all living things. He calls the birds and trees and rocks by name; nay, even the beetles and worms are his friends. The mountains seem to call to him, and he lifts his head to answer them. He can sit for hours listening to the tiny drip, drip of the water that trickles down the face of the rocks, singing its own melody year in and year out, and this faint stirring of life fills his soul with contentment.

Glahn follows the intense seasonal changes of Nordland. At midsummer, when the sun hardly dips its golden ball in the sea at night, he sees all nature intoxicated with sex, rushing on to fruition in the few short weeks of summer. Then mysterious fancies come over him. He weaves a strange tale about Iselin, the mistress of life, the spirit of love, who lives in the forest. He dreams that she comes to him and tells about her first love. The breath of the forest is like her breath, and he feels her kisses on his lips, and the stars sing in his blood. The women who meet him in the forest, Eva and the little goat-girl, seem to him only a part of nature as they expand unconsciously to love like the flower in the sun, and he takes what they give him. Yet there is in him a spiritual craving which these loves of the forest can not satisfy.

Summer passes; the first nipping sense of autumn is in the air, and the children of nature too feel the benumbing hand of coming winter, as if the brief thrill of summer in their veins had already subsided. But in the solitude of the dark, cold "iron nights" the Northern Pan wins from Nature the highest she has to give him. As he sits alone, he gives thanks for "the lonely night, for the mountains, the darkness, and the throbbing ocean.... This stillness that murmurs in my ear is the blood of all nature that is seething. God who vibrates through the world and me."