The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Girl in Spring-Time, by Jessie Mansergh

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: A Girl in Spring-Time

Author: Jessie Mansergh

Illustrator: Gertrude Demain Hammond

Release Date: July 27, 2011 [EBook #36874]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A GIRL IN SPRING-TIME ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

Jessie Mansergh

"A Girl in Spring-Time"

Chapter One.

The Day Before the Holidays.

It was the day before the midsummer holidays, and the girls of the first form were sitting together in the upstairs school-room at Milvern House, discussing the events of the term, and the prospective pleasures of the next few weeks. Lessons had been finished in the morning, the afternoon had been given up to packing, and now they were enjoying a delightfully unsupervised hour of rest.

A tall, slim girl was standing by the table, turning out the contents of a desk, and filling the waste-paper basket with fragments of paper. The other pupils watched the movements of the small hands, and the sleek, dark head with unconscious fascination. There was something delightfully trim and dainty about Bertha Faucit. Her hair was always neat, her actions deliberate and graceful; she reminded one irresistibly of a sleek, well-nurtured pigeon pluming its wings in the sunshine, with a very happy sense of its own importance.

By the window stood another girl, who was evidently a sister, for she wore a dress of the same pattern, and held herself with a like air of dignified composure. Bertha and Lois Faucit were the daughters of a dean who lived in an old cathedral town, and their school-fellows were accustomed to account for every peculiarity on this score. “Dean’s daughters, you know!” It was ridiculous to expect that the children of such a dignitary would indulge in pillow-fights, and bedroom supper, like ordinary frivolous mortals.

Bertha was talking all the while she worked, dropping out her words with the same delicate distinctness which characterised her actions.

“Picnics? Oh, dear me, yes! We have a picnic almost every week. We take the pony carriage and carry our own provisions, and make a fire of sticks. Have you ever tried to boil a kettle in the open air? It is a terrible experience. First of all the wood is so damp that it won’t light, and you get all smoked and dirty; then when it does begin to burn, and you put the kettle on the top, the whole thing collapses to the ground, and you have to begin again from the beginning. You prop it up with stones, and get everything started for the second time, and then the others come back from laying the table and say, ‘What! isn’t the water boiling yet? Oh, you don’t know how to light a fire! It is not properly laid. Let me show you!’ and down comes the whole thing again. At the end of an hour the kettle boils, and the water is smoked! We always use it to wash our hands, and drink milk instead. This year I intend to use fire-lighters.”

“We have a proper tea-basket for taking about with us,” said one of the other girls. “The kettle hangs over a lamp which is protected from the draught, and you can have boiling water in ten minutes without any trouble. We always take it when we go on the river. I like boating picnics best of any.”

“We go to the sea-side for the whole of the holidays,” said Ella Bennet, a big girl with rosy cheeks and long, brown hair; “Mother thinks the bathing does us so much good. I learnt to swim last year. An old fisherman rowed out in a boat. I had a strap fastened round my waist, and he held me up with a pole while I went puffing round and round. He tried to teach me to dive as well, but I was too nervous. One day I vowed I really would try. I climbed on to the edge of the boat six times over, while he held me, and showed me how to put out my hands, and each time I began to squeal, and jumped down again at the last moment. It was band day, so there were hundreds of people sitting on the shore, and they roared with laughter. I was ashamed to come out of the van.”

“I don’t care about the sea-side. I like the country,” said another girl. “Last year we stayed at an old farmhouse in Derbyshire. The walls are of oak, and there are secret cupboards on the stairs. There is a legend that on moonlight nights one of the rooms is haunted by a lady in white, who comes and sits by an old spinning-wheel. One evening I dressed up in a sheet, powdered my hair, and blacked my eyebrows, then I got the landlady to suggest to the others that they should go upstairs and look for the ghost. They came up in a rush, and there I was spinning away with my head bent down as solemn as a judge. They were awfully quiet, but the boys crept nearer and nearer, and then pretended to faint, and toppled right over me. Horrid things! It turned out that the silly old woman thought they might be frightened, so she told them who it was before they came up. I was so cross!”

“But they might really have been frightened. I wouldn’t go upstairs to see a ghost for a million pounds—not by myself, at least,” said Nellie Grey, the youngest girl in the form. “Of course it wouldn’t be so bad if you had your brothers with you. Brothers are great teases, but they never get frightened themselves, so it is a comfort to have them sometimes. My eldest brother is awfully brave. He wanted to be a sailor, but Father wouldn’t let him, so at Christmas he confided in us one night that he was going to run away. He said good-bye, and divided his things among us. I got the paint-box, and Minnie the desk, and Phil the books and tool-chest. Next morning when we came down to breakfast, there he was just the same as usual. He hadn’t run away at all. He said it was too cold. But we wouldn’t give the things back. It’s an awfully nice paint-box, with a lovely big palette in a drawer underneath. Mildred! how quiet you are! What are you going to do in the holidays?”

The speaker turned to look at a girl who was seated on the edge of the table itself, and everyone in the room followed her example with an alacrity which showed how pleasant the sight was in their eyes.

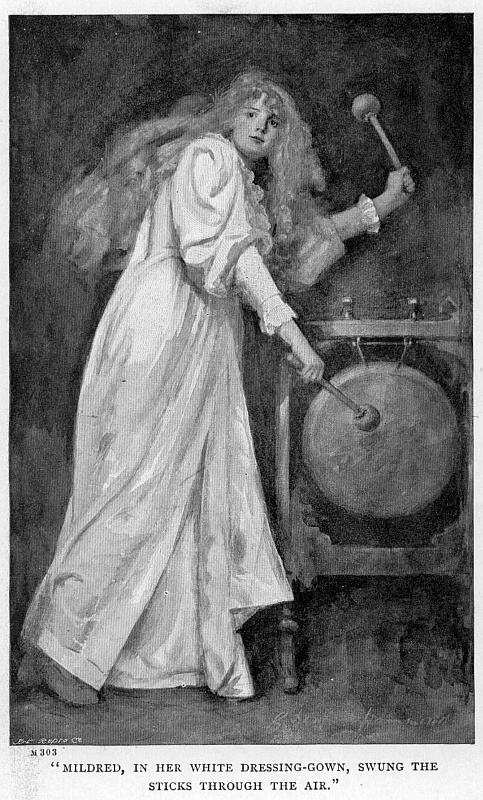

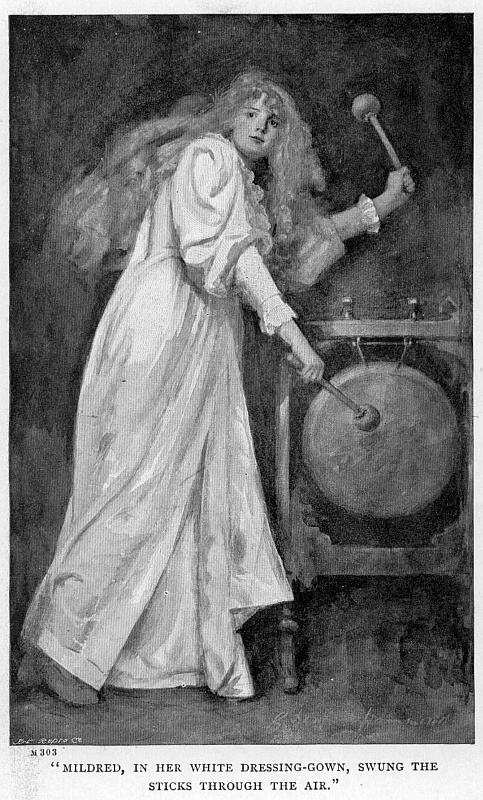

Mildred Moore had just passed her fourteenth birthday, but she was so big and strong that she looked older than her age. Her long legs nearly reached the floor, her hands were folded in her lap, and she stared through the window, lost in happy day-dreams. Mildred was the beauty of the school, and as the love of all that is sweet, and bright, and lovely is natural to girlhood, her companions placed her on a pedestal on that account, and treated her with special marks of favour. Eva Murray, who was sentimental, was accustomed to declare that Mildred was exactly like a Norse princess, and when Blanche Green, who was practical, asked what a Norse princess was like, she replied that she had never met one in real life, but had seen many in picture galleries, that they always had grey eyes and golden hair, and looked strong and kind and fearless, but also as if they could be awfully disagreeable if they liked,—which settled the question once for all, for everyone agreed that the description suited Mildred to a T.

“What am I going to do?” repeated the Norse princess cheerily. “Why, nothing at all in the way you mean. We never go away, either to the country or the sea-side, or have picnics, or parties, or any excitements of that kind. We just stay quietly at home and go on with the usual work, but I am with Mother, you know—that’s my holiday! You have never seen her, you girls; I wish you had, for she is quite different to other peoples’ mothers. She is only twenty years older than I am, to begin with, and she is awfully pretty. She is a tiny little thing, with dark eyes, and soft brown hair. She comes to meet me at the station in a sailor hat, and a little blue jacket, looking like a big school-girl herself. I’m so proud of her! Last time I went home I took her up in my arms and carried her across the room. She kicked like anything and said, ‘You disrespectful child! How dare you! Put me down this instant!’ but she wasn’t really angry a bit, and we both tumbled over on to the sofa, and laughed till we cried. We do enjoy ourselves so much when we get together—Mother and I. She is lonely when I am away, poor dear, with no one to speak to but the children, so we make up for it in the holidays. I sit up to supper every night, and we have coffee, and hot buttered toast, and all sorts of good things that are bad for us, and in the daytime we bribe the elder children with pennies to amuse the younger ones, so that we may have the room to ourselves, and talk of the good times we shall have when my schooling is over, and I go home to stay!”

The girls gazed at Mildred as she spoke, with a mingling of envy and compassion. Envy,—because her intense delight in the mere prospect of being at home made them conscious of their own selfishness in regarding the holidays as a period when parents should occupy themselves in providing amusement for their families;—compassion,—because it was well known that Mrs Moore was a widow, and so poor that she could not afford to leave the country house where she lived with her half-dozen noisy youngsters. Mildred had been sent to a good boarding-school so that she might be able to teach her little brother and sisters in due time, and the other girls were specially pitiful over this prospect.

Mary Nicoll referred to the subject now with questionable taste.

“But it won’t be much fun, Mildred, if you have to teach all day long. You won’t be able to go about as you like, or have any time free except in the evenings. And fancy having to go over all the wretched old lessons again, and to drill tables and dates, and latitudes and longitudes into the brains of a lot of stupid children. It will be worse than being at school.”

“Our children are not stupid. They are as sharp as needles, and I don’t think it will be dull at all. It will be fun to have the positions reversed, and to do none of the work and all the fault-finding. I shall bully them fearfully. Can’t you imagine me—very proper and stiff, hair done up—sitting at the head of the table tapping with a lead pencil... ‘At-tention to the board! ... Shoulders back, young ladies, if you please! Your deportment leaves much to be desired! ... My dear, good child, how can you be so stupid! You try my patience to the uttermost!’”

Mildred accompanied these remarks with contortions of the face and body in imitation of the different teachers at Milvern House, and the bursts of laughter with which they were greeted showed how real were her powers of mimicry. She joined in the laughter herself, then suddenly breaking off, clasped her hands together, and rocked to and fro in an ecstasy of anticipation.

“This time to-morrow—oh! I shall be driving home from the station. We shall have passed the village cross, and the almshouses, and turned the corner by the farm. The children will be swarming out of the gate—the table will be laid for tea, with a bowl of roses in the middle—oh!—and strawberries—oh!—and real, true, thick, country cream. To-morrow! I can’t believe it. I don’t think I ever wanted to go home so badly before. The term from Christmas to midsummer seems so awfully long when you don’t go away for Easter. I shan’t sleep a wink to-night, I am so excited. I don’t think I can lie down at all.”

The girls were so absorbed in their conversation that they had not heard the door open during Mildred’s last speech, and the new comer had thus an opportunity of listening undisturbed. She was a tall, slight young lady, with dark hair, and the sweetest brown eyes that were ever seen. She wore a black dress, and white collar and cuffs, and looked as if she were trying her best to appear old and dignified, and not succeeding so well as she would have wished. This was Miss Margaret, the younger of the two lady principals, familiarly known among the girls as “Mardie”, because she was “such a darling” that it was impossible to address her by an ordinary, stiff, school-mistressy title. This afternoon, however, Mardie’s eyes were not so serene as usual, and her face clouded over in a noticeable manner as she listened to Mildred’s rhapsodies.

“Mildred, dear,” she said, coming forward and laying her hand on the girl’s shoulder. “I want you in my room for a few minutes. I won’t keep you long. There is something—”

“You want to say to me! Oh, Mardie, I can guess. I have left my slippers in the middle of the floor, and thrown my clothes all over the room. I know—I know quite well, but it’s the last day—I can’t be prim and tidy on the last day. It’s not in human nature!” Mildred took hold of Miss Margaret by the arm, and rubbed her curly head against her shoulder in a pretty, kitten-like manner. “To-morrow morning you will be rid of us altogether, and then—”

“But it is not about your room, Mildred. Come dear—come with me. I really want you.”

“I’m ready then!” The girl slipped lightly to the ground, and turned to follow Miss Margaret from the room. “You make me quite curious, Mardie. Whatever can it be?”

Chapter Two.

A Great Disappointment.

Miss Margaret’s room was on the third floor, and did service both as a bedroom and as a sanctum to which its owner could retire in rare moments of leisure. The bed stood in a corner, curtained off from the rest of the room; pictures hung on the walls; little bookcases fitted into the angles; while before the window was an upholstered seat, so long and wide, and luxuriously cushioned, as to make an ideal sofa. In the girls’ estimation Mardie’s room was a paradise, and it seemed almost worth while having a headache, when one could be tucked up warm and cosy on that delightful seat, shaded from the sun by the linen blind outside the window, yet catching delicious peeps at the garden beneath its shelter.

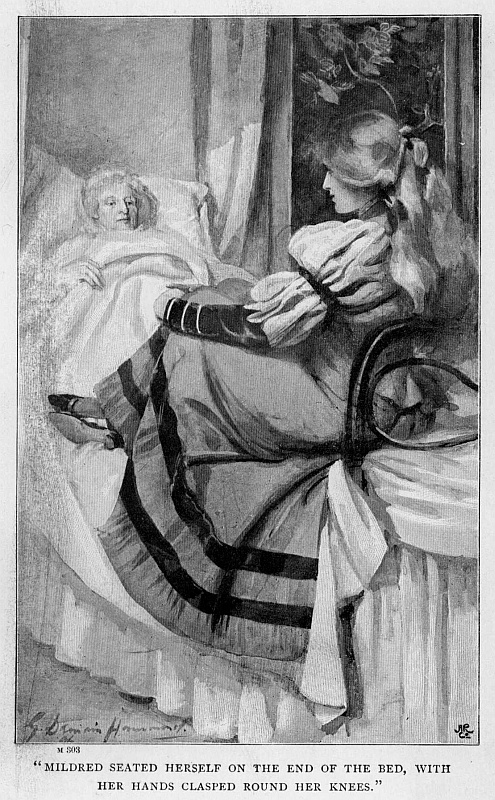

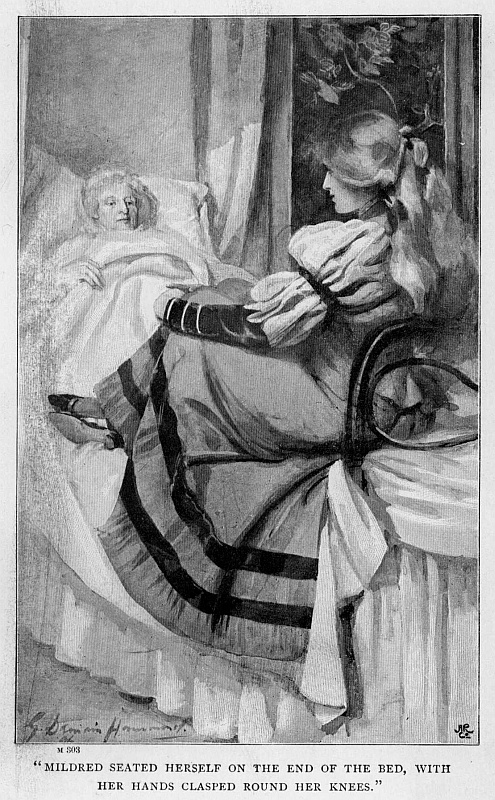

Mildred made straight for the coveted position and leant back against the cushions, her hands clasped round her knees in an attitude rather comfortable than elegant. For once, however, Miss Margaret had no reproof to offer. She had nothing to say about the awful consequences of curving the back and contracting the chest; she did not even inquire, with a lifting of the eyebrows, “My dear Mildred, is that the way in which a young lady ought to sit?” She only gazed at the girl’s face and wrinkled her brows, as if puzzled how to open the conversation.

“Go on, Mardie, dear?” said her pupil, encouragingly. “What is it—have I done anything wrong? I don’t know what it is, but I’m awfully sorry, and I’ll never do it any more. Don’t scold me on the last day! I’ll promise faithfully—”

“Don’t, dear! It isn’t anything like that.” Miss Margaret straightened herself with an expression of resolution and went boldly forward. “Mildred, are you brave? Can you bear a great disappointment?”

Mildred raised her eyes with a start of apprehension. There was a moment’s silence, during which a curious change came over the girlish face. The colour faded from the cheeks, the eyes hardened, the lips set themselves in a thin, straight line.

“No,” she said sharply, “I can’t!” and Miss Margaret looked at her with gentle remonstrance.

“Oh, Mildred, don’t take it like that! I have had to bring other girls into this room, dear, and tell them of troubles compared to which this disappointment of yours is as nothing—nothing! Poor little Effie Browning, looking forward to her parents’ return from abroad, and counting the hours to their arrival—I had to show her the telegram announcing her mother’s death. And Mabel, and Fanny—But your mother is well, quite well and safe. Doesn’t that make you feel thankful to bear any lesser trouble?”

“No!” said Mildred again, more obstinately than before; “No!” She stared at Miss Margaret with unflinching eyes. “If Mother is well, there is only one other trouble which I could feel just now. If—if it is anything to prevent me going home, I can’t bear it—it will kill me! I shall break my heart!”

“Nonsense! You are far too strong, and brave, and sensible to break your heart over a disappointment of a few weeks, however hard it may be to face. Come, Mildred, you know I rely upon you to be my helper in difficulties; you must not quarrel with me, for we shall have to keep each other company. Your little brother Robbie has taken scarlet fever, and you will not be able—”

She did not finish the sentence, for her pupil interrupted with a cry of bitter grief, and buried her face in her hands. It was one thing to imagine a thing, and another to know that it was true in solemn earnest. Mildred had spoken of the possibility of not being able to go home as of some appalling imaginary calamity, but she had never, never thought it could be true. Not go home! Stay at school all through the holidays!—the prospect was so terrible that it was impossible to realise all that it meant. Nevertheless some of the first miserable consequences were clear enough to poor Mildred’s mind:—to unpack all her boxes, to put her clothes back in drawers and cupboards; to sleep by herself in the deserted dormitory; to spend the days lounging about empty school-rooms, feeling doubly lonely because of the remembrance of the friends who had been by her side but a few days before, and who had now dispersed to their own happy homes. Effie Browning had spent the holidays at school once or twice, and Mildred had pitied her so much that she had sent weekly letters and boxes of country flowers and mosses, to cheer her solitude. And now she herself was to undergo this awful experience! To-morrow morning the other girls would fasten their boxes and drive off to the station, but for her there would be no excitement of farewell, no railway journey, with the delightful sense of importance in travelling by herself all the way from the junction, no dear little mother waiting to greet her in sailor hat and blue serge suit! Her heart swelled with passionate longing, but she could not cry; the blow was too sudden, too severe. Miss Margaret’s eyes were wet, however, as she looked down at the curly, golden head. She did not speak for a few minutes, then she laid her hand on the girl’s arm and pressed it to attract attention.

“I am so sorry for you—so sorry, my poor girl. See, dear, here is a letter which came inclosed in one to my sister. Your mother wished us to break the news—”

Mildred seized the letter in an almost savage grasp. It was in her mother’s handwriting, and ran as follows:—

My darling Mildred,

When you get this letter, Miss Chilton will have told you of the trouble at home. Poor little Robbie has been very poorly for two days, and this morning the doctor pronounces it to be scarlet fever. I could not help crying when he told me, for so many things came rushing into my head, and it all seemed so dark and difficult. I was anxious about Robbie, and couldn’t think what to do with the rest of the children; and you, my darling, with your holidays just beginning! It broke my heart to think of you. I seem to have lived a month in the last few hours, but everyone has been so kind, and help has come from all directions. Mrs Bewley and Mrs Ross are to take the children to stay with them, as they have no little ones of their own, and are not afraid of infection. I will nurse Robbie, and if any of the others fall ill, they will be sent home at once, and we will make a hospital of the top floor. I suppose, even if all goes well, and Robbie is the only patient, it will be six weeks before we are out of quarantine. Oh, my dearest child, I am so grieved for your disappointment, coming upon you in the midst of your preparations; but there is no help for it, you must stay on at school, for there is no other place to which I can send you. I can’t ask either Mrs Bewley or Mrs Ross to take you in addition to the other children, and even if you were here we could not see or speak to each other, and it would be dreadful to know that you were so near, and not be able to be together.

I am as disappointed as you, can be, dear, for I can’t tell you how I was looking forward to having my dear, big girl back again, but this is a trouble which has come to us, and which we cannot help, and we must try to be as brave as possible. Robbie is very hot and feverish to-day. He asked when you would be at home, and I was obliged to tell him that you could not come now. A little time afterwards I went back and found him crying, “’Cause Millie will be angry wif me!” Poor wee man! if he only gets on well we must not mind any disappointment which his illness has caused.

I shall not be allowed to send you letters, dear, but please write to me as often and as cheerfully as you can. We shall be shut off from all our friends, and letters will be eagerly welcomed. I send you a postal order for a sovereign for pocket-money during the holidays. It is all I can afford, darling, or you should have ten times as much. You know that.

I have not another minute to spare, so goodbye, dearie. I shall think of you every hour of the day. Help me by being brave!

Mother.

Mildred read the letter through, folded it away, and looked up at Miss Margaret with bright, dry eyes.

“Can I go to my own room, Miss Margaret, please?”

“You can if you like, Mildred, but the other girls will be there in a moment, getting ready for tea. Wouldn’t you prefer to stay here? I will give you my writing-case, and you can write to your mother; she will be longing to hear. You shall have tea up here, a nice little tray, and Bertha shall have it with you, unless you prefer to be alone.”

“I don’t want to see anyone. They are all going home. It would make me feel worse than ever. They are all happy but me—”

“They will feel your disappointment almost as much as you do yourself. We are all so grieved; but I will do my best to make the holidays pleasant for you, dear.”

“Don’t be kind to me, Mardie, please. I can’t bear it—I feel as if I hated everyone! Why need Robbie take ill just now of all times in the year? He is a tiresome little thing. It is always the same way,—there is more trouble with him than with all the five girls. Why can’t Mother stay with us and send him away to be nursed? There are five of us, and only one of him. I wasn’t home at Easter, though almost all the girls went. I can’t live six whole months longer without seeing Mother. It makes me wild even to think of it!”

“Don’t think of it, Mildred. Six months is a long way ahead; a hundred things may happen before then. Don’t worry yourself about months, think only of to-day, and try to be bright, and brave, and patient.”

“It would be horrid of me to be bright when Mother is in trouble. I can’t be brave when everything goes wrong; I can’t be patient when my heart is breaking.”

“It is hard, dear, but there are harder trials than this, which we have to bear as we go through life, and you know—”

“Mardie, don’t preach! Don’t! I can’t bear it. How can it make it easier to know that other people have worse troubles? It makes it harder, for I have to be sorry for them as well as myself. It’s no use trying to reason; you had better leave me alone. If you say another word I—I—I shall—” Mildred’s voice broke, she struggled in vain against the rising sobs, and burying her face in her hands, burst into a storm of bitter weeping.

Miss Margaret did not try to check her, for she knew that tears would be a relief, and that after this outburst Mildred would be calmer and more reasonable. She patted her heaving shoulders and murmured caressing words from time to time.

“Dear Mildred! poor girl! I am so sorry,—we are all so sorry for you, dear. You know that—don’t you?”

Mildred cried on unrestrainedly, but by and by she nestled nearer to Mardie’s side, and a few broken phrases began to mingle with her sobs.

“Oh, Mardie, I don’t want—to be—so horrid! I’ll try—to be good.—But you don’t know—how—I feel—inside! All raging, desperate! It seems—as if—it can’t be true. I was so happy. It was so—near.”

“Yes, dear, yes; but, Mildred, listen to me. I know that nothing can make up for home or Mother, but I am not going away for two or three weeks, and we will have some cosey little times together—you and I. You shall sleep with me, we will have our meals in the south parlour, and we will go little expeditions on our own account, have tea in village inns, and botanise in the fields. The doctor’s daughter will be at home from school, she shall come and spend the day with you as often as you like, and you must help me to pick fruit and make jam. We will get some nice books too, and read aloud in the evenings. It won’t be so dreadful—will it, dear? Come, Mildred, if you cry like this I shall think you don’t care for me at all.”

“Oh, Mardie, I do! I love you, and I know you will be kind, but I’m—tired of school. I want Mother! I want Mother!” And down went the curly head once more, and Mildred burst into fresh floods of tears.

It was indeed a sad ending to a day which had dawned with such radiant promise.

Chapter Three.

Friends to the Rescue.

There was consternation downstairs when the news of Mildred’s disappointment was made public. The girls clustered together in groups, and talked with bated breath. The number of times that the words “fearful” and “awful” were used would have horrified Miss Chilton if she had been present, and one and all were agreed that their friend was the most pitiable creature upon earth.

Even the little sixth-form pupils were full of sympathy, for Mildred took more notice of them than any of the “big girls”, and even condescended, upon occasion, to spend a holiday afternoon helping them with their games and “dressings up.” Within ten minutes of hearing the news little Nina Behrends had scribbled a note on a leaf of an exercise-book, and fitted it into an envelope together with a bulky inclosure. She trotted upstairs and knocked at Miss Margaret’s door, and when Mildred peered out into the passage with her tear-stained eyes, the little mite pressed the package into her hands and scuttled away as fast as her legs would carry her.

Mildred opened the envelope with a feeling of bewilderment, which was certainly not decreased when she drew forth an aged piece of india-rubber, shaggy and frayed at the ends, as with the bites of tiny teeth. She turned to the note for an explanation, which was given in the following words:

Deer Mildred,

I hope you are quite well. I send you my injy-ruber. The thick side rubs out. I hope it will comfort you that you can’t go home.

So I remain,

Your little friend,

Nina.

Poor little Nina! The “injy-ruber” was one of her greatest treasures, and it had seemed to her that no other offering could so fitly express her love and pity.

The same impulse visited all the other girls in their turn. It was not enough to sympathise in words, it seemed absolutely necessary to do something; and before half an hour was over, every girl was rummaging through the contents of a newly-tidied desk, in search of some tribute which she might send to Mildred in her distress. Such a curious collection of presents as it was! Pencil boxes (more or less damaged); blotted blotters; “happy families” of ducks and rabbits congregated on circles of velvet; photograph frames; coloured slate-pencils;—it would be difficult to say what was not included in the list, while every gift was wrapped in a separate parcel, and offered in terms of tenderest affection.

Bertha Faucit was deputed to carry the presentations upstairs, and she found Mildred sitting upon the window-seat, gazing out into the garden with dreary, tear-stained eyes. There was nothing in the least like a Norse princess about her at this moment. She looked just what she was—a particularly lugubrious, unhappy, English school-girl. Her face lighted up with a gleam of pleasure when she saw her friend, however, for she had been alone for nearly an hour, while tea was going on downstairs, and was beginning to find the unusual silence oppressive.

“Oh, Mildred!” cried Bertha. “Oh, Bertha!” cried Mildred; then they collapsed into silence, gazing at each other with melancholy eyes.

“I can’t—go home!” said Mildred at last, speaking with heaving breath and suspicious gaps between the words. “I have to stay here all the holi—days—by myself! Eight weeks—fifty-six days! I think I shall go mad—I’m sure I shall! My head feels queer already!”

“That is because you have been crying. You will be better in the morning,” said Bertha, and her quiet, matter-of-fact voice sounded soothingly in her friend’s ears. “See, Mildred, the girls have sent you these little presents to show how sorry they are for your disappointment. We couldn’t go out to buy anything new, so you must excuse us if they are not quite fresh. I have brought my crayons,—you said the blue was a nicer colour than yours; Lois has chosen two texts for illuminating, and there are all sorts of things besides. See what a collection! Maggie Bruce has sent an exercise-book with the used leaves torn out. She said it was to be used as an album; and when we go home we are all going to ask our fathers for foreign stamps, and send them on to you. Don’t you want to look at all the other things?”

Bertha had laid the parcels in a row along the floor, and Mildred now took up one after another and examined the contents, while at one moment she laughed, and at the next her eyes ran over with tears.

“How good of them all—how kind! Poor little Nina Behrends presented me with her ‘injy-ruber’ before tea. It is so dirty that it would spoil anything it touched, but it was sweet of the little thing to think of it. A note from Carrie. Poor old Elsie—fancy sending me this! What a nice frame; I’ll put your photograph in it, Bertha. Slate-pencils! does she think I am going to do sums in the holidays? Oh, Bertha, don’t think me horrid, but people seem to me to have a very queer idea of comfort! Miss Margaret sent up strawberry jam and cake for my tea, as if anything to eat could make up for not seeing Mother!—or pencils, or books, or stamps. I’d give all the stationery in the world if I could only wake up and find it was a dream, and that I was really going home!”

“I don’t think that is quite the right way to look at it,” said Bertha, seating herself elegantly on a chair, and speaking in her precise, little, grown-up manner. “We don’t expect these things to ‘make up’; they are not of much value in themselves, but you must think of their meaning, and that is that we all love you, and are sorry for you, and want to do everything in our power to help you.”

“Yes, yes, I know; you are all angels, and I am a wretch!” cried poor Mildred dismally. “I don’t deserve that you should be so kind. I should like to be grateful and patient, but I can’t! Bertha, if you were in my place, and had to stay here at school all alone, without even Lois or a single one of the girls, what would you do?”

Bertha reflected.

“I think I should cry a good deal at first,” she said honestly, “and lie awake at nights, and have a headache, but I should try to be resigned. I have never had anything very hard to bear, and sometimes I have almost wished that I had. I don’t mean, of course, that I want anyone belonging to me to fall ill like your brother. I should like a trouble that affected myself alone, so that I might see how well I could bear it. I love to read about people who have had terrible trials, and have been brave and heroic, and overcome them all. I have an ambition to see if I could imitate them.”

“Well, I haven’t,” said Mildred, “not a bit; and you won’t like it either, Bertha, when it comes to your turn! Besides, I don’t see that there is much chance of being heroic in living alone by yourself in a ladies’ school. Heroes have to fight against armies, and plagues, and terrible calamities, and I have to face only dullness and disappointment. Even if I bear them well it will be no more than is expected of me. ... There would be nothing heroic about it!”

Bertha knit her brows in thoughtful fashion.

“I am not so sure,” she said. “I think it must be pretty easy to be brave when you are marching with hundreds of other people, while drums are beating and flags waving, and you remember that England expects you to do your duty, and that the whole world will talk of it to-morrow if you do well. It would be quite easy for you, Mildred; for you are never afraid, and you would get so excited that you would hardly know what you were doing. It will be much harder for you to sit still here and be cheerful; and to do the hardest thing must be heroic! I will write to you often, Mildred; all the girls will write. You will have heaps of letters.”

“That will be nice. I love letters,” said Mildred gratefully. She cheered up a little at the prospect, and talked to her friend for the next half-hour without relapsing into tears. Nevertheless, the remembrance of the poor, disfigured face weighed heavily on Bertha’s heart, and she could talk of nothing else, as she and Lois finished their packing later on the same evening.

“I feel quite mean to be going home when poor Mildred is left here alone,” she said. “And we have such a happy time. Father and Mother are so good, they give us almost everything we ask in the holidays. I wonder—” She stopped short as if struck with a brilliant idea, and stared into her sister’s eyes.

“I wonder—” echoed Lois immediately, and her voice had the same ring, her face the same curious expression.

The pupils at Milvern House were often amazed at the instinctive manner in which these two sisters leapt to an understanding of each other’s meaning, and the present instance it was evident that Lois needed no explanation of that mysterious “I wonder.” “We are twins, you know,” they were accustomed to say, when questioned about this peculiarity, and it seemed as if this fact did indeed save them from much conversational exercise.

“We will see!” said Bertha again, and Lois nodded her head and repeated, “We will see!” while her face lit up with smiles.

But Mildred did not know what pleasant schemes her friends were plotting on her behalf, and she lay, face downwards, crying heart-brokenly upon her bed.

Chapter Four.

Bad News from Home.

The next morning Mildred awoke with a wail of despairing remembrance. She hid her face in the pillow and wondered how she was to live through the day, to see the different batches of girls leave the house at ten o’clock, at eleven, at one, at half a dozen different times, while she was left alone in solitary misery.

Her friends, however, were too considerate of her feelings to let her experience such a trial. Immediately after breakfast Miss Chilton announced that she was going to spend the day in a neighbouring township, and requested Mildred to get ready to accompany her. Now, Miss Chilton was a majestic person, with a Roman nose and hair braided smoothly down each side of her face; and none of the girls dared to argue concerning her decrees, as they did, on occasion, with the more popular Miss Margaret.

So Mildred marched meekly upstairs, to put on hat and jacket, without uttering a single protest. She would have liked to say, “Oh, do leave me alone! I would far rather stay at home and mope;” and Miss Chilton probably guessed as much, though she took no notice of her companion’s downcast expression, and sat with the same unconscious smile upon her face all the length of the journey.

She had some shopping to do, in preparation for her own holidays, but when that was over, she and her pupil repaired to the house of a friend, where they were to lunch and spend the afternoon.

The friend had two daughters about Mildred’s own age,—bright, lively girls, who carried her away to their own rooms, showed her their possessions, confided secret plans, and were altogether so kind and friendly that she forgot to be unhappy, and chatted as gaily as they did themselves. Miss Chilton had probably sounded a note of warning in the letter which announced her coming, for no one said a word to Mildred on the subject of the holidays, but when she was leaving, the mother invited her to spend another day with the girls, and the girls themselves kissed her with sympathetic effusion.

It was nearly eight o’clock when the travellers reached school again, to find the house transformed from its usual bustling aspect. The classrooms were closed, supper was laid in the cosy little south parlour, and when Mildred tried to enter the dormitory which she shared with two other girls she found that the door was locked, and Miss Margaret came smilingly forward to lead the way to her own room.

“I have been as busy as a bee all afternoon. Come and see how nicely I have arranged it all,” she said brightly, and Mildred, looking round, saw her own chest of drawers in one corner, her dresses hanging neatly in the wardrobe, while a narrow bed stood out at right angles from the wall.

Her heart swelled at the sight, and a hundred loving, grateful thoughts arose in her heart. She longed to thank Miss Margaret for sparing her the painful task of unpacking, and for letting her share this pretty, luxurious room, but it seemed as if an iron band were placed round her lips, and she could not pronounce the words.

“The bed spoils the look of the room!” she muttered at last, and even in her own ears her voice sounded gruff and ungracious; but Miss Margaret only smiled, and slipped one arm caressingly round her waist.

“Ah, but I sha’n’t think that when I wake in the morning and see my little goldilocks lying beside me, with her curls all over the pillow like the princess in the fairy tale!” she said, and at that Mildred was obliged to laugh too, for she was like most other mortals—marvellously susceptible to a touch of flattery!

“A very grumpy princess!” she said penitently. “I am really awfully grateful, Mardie, but I can’t show it. You will excuse me if I am nasty for a day or two, won’t you, dear?”

Mardie raised her eyebrows and pursed up her lips in comical fashion. She was always unusually lively for a school-mistress, but already it seemed to Mildred that she was quite a different person from the “Miss Margaret” of term time. She wore a pretty blue dress, with lace frillings on the bodice, and walked about with an airy tread, as though released from a weight of responsibility.

“Well,” she said, nodding her head, and looking as mischievous as a girl herself, “I’ll make allowances, of course, but I hope you won’t try me too far. I am a delightful person out of school time, and mean to enjoy every day of the holidays to the full—unless you prevent me I shall be dependent upon you!”

“I prevent you,—I!”

That seemed to put the matter in a new light, and Mildred was overcome at the thought of her own selfishness. Whatever she might have to suffer, she must not spoil poor Mardie’s pleasure in her well-earned rest. That would be inexcusable. She determined to do her utmost to be brave for Mardie’s sake.

The next day Miss Chilton departed on her travels, and a letter arrived from Mrs Ross giving a serious account of the little invalid’s condition. She evidently tried to write as cheerfully as possible, but Mildred read anxiety between the lines, and was full of compunction.

She had never imagined that Robbie would be really ill, but had looked upon the fever as a childish complaint which would make him hot and red for a few days, and put everyone else to inconvenience for as many weeks. She had not only felt, but said, that it was very “tiresome” of him to have taken ill at such a time; but now the remembrance of poor wee Robbie lying in bed crying, “’Cause Millie would be angry wif him,” cut her to the heart. The day seemed endlessly long and dreary, and the next morning’s news was worse instead of better. Robbie’s life was in danger. The doctor hoped, however, that a change might take place within the next twenty-four hours, and Mrs Ross promised to telegraph in the afternoon to allay his sister’s anxiety.

Miss Margaret looked very grave, but she said little, and did not attempt to follow when Mildred fled upstairs, leaving the letter in her hands. There are times when we all prefer to be alone, and this morning Mildred could not have brought herself to speak to anyone in the world but her mother. She lay motionless on the window-seat, her head resting on the open sill, the summer breeze stirring the curls on her forehead, while the clock in the hall chimed one hour after another, and the morning crept slowly away. For the most part she felt stupefied, as if she could not realise all that the tidings meant, but every now and then her heart swelled with an intolerable ache.

It was true that Robbie had caused more trouble than his five sisters put together, but his exploits had been of an innocent, lovable nature, and when the temporary annoyance which they caused was over, she and her mother had laughed over them with tender pride. He was such a manly little fellow! Many a boy would have been spoiled if he had been brought up in a household composed exclusively of womenkind, but nothing could take the spirit out of Robbie. He had begun to domineer over his sisters while he was still in petticoats, and now that he was promoted to sailor suits, he gave himself the airs of the master of the house! Mildred recalled the day when he had been discovered standing before a mirror, making wild slashes at his curls with a pair of cutting-out scissors. The explanation given was that some boys had dared to call him “pitty girl!” and he couldn’t “’tand it!” When his mother shed tears of mortification, Robbie hugged her with sympathetic effusion, but sturdily refused to say that he was “torry!”

A vision of the little shaggy head rose up before Mildred’s eyes: she saw the chubby face, the defiant pose of the childish figure, and stretching out her hands, sobbed forth a broken prayer.

“Oh, God! you have so many children in Heaven—so many little boys. We have only one... Don’t take Robbie!”

The morning wore away, the blazing sun of noon shone in through the open window, Mildred’s head throbbed with pain, then gradually everything seemed to sink away to an immeasurable distance, and she was lost in blessed unconsciousness.

When she awoke the church bell was chiming for afternoon service, and Miss Margaret knelt by her side, holding an open telegram in her hand.

“I opened it, darling!” she said; “I thought it would be better. It is good news, Mildred—good news! Robbie is better. The doctors think he will get well now!”

Ah! that was a happy afternoon! Mardie took Mildred in her arms and kissed and petted her to her heart’s content, then the door opened and in came old Ellen, the cook, carrying a tea-tray with freshly-made scones, a plate of raspberries from the garden, and a jug of thick, country cream. The kind old soul had been so full of sympathy that she had insisted upon carrying it up the three flights of stairs herself, although her breath was of the shortest, and she gasped and panted in alarming fashion. Mildred laughed and cried in one breath, and lay back against the cushions, drinking tea, and eating raspberries in great contentment of spirit.

“I was awfully hungry, though I didn’t know it. I feel as if I had been ill. Oh, Mardie, isn’t it a lovely feeling when the pain goes, and you can just rest and be thankful! ... It’s worse to have a pain in your mind than in your body. I feel ashamed now that I made such a fuss about staying at school—it seems such a little thing in comparison, but don’t say ‘I told you so!’ Mardie, or that will make me feel horrid again. It really is big, you know, only the other was so much bigger... Mardie, have you ever had a disappointment—as big a disappointment as mine?”

A quiver passed over Miss Margaret’s face, and for a moment she looked very sad.

“Oh, Mildred, yes!” she cried. “Everyone has, dear, but sometimes I have been discontented enough to imagine that I have had more than my share. A disappointment, indeed! dozens,—scores,—hundreds! But of course some are harder to bear than others.”

“Tell me about one now!” said Mildred, leaning back against the cushions and settling herself to listen in comfort. “Do, Mardie! I feel just in the humour to listen to a story; and I know it will be interesting if you tell it. ‘The Story of a Disappointment!’ Something exciting that happened to you when you were young. Now then, go along! Begin at once!”

Mardie laughed, and then pretended to look indignant.

“When I was young, indeed! What do you call me now? When you are my age you will be very indignant if anyone calls you old. Well now, let me see! I’ll tell you the story of a disappointment which happened to—well—not exactly to me, but to a very great friend whom I had known all my life. He tried to get on in business in England, but it seemed as if there was no opening for him here, and at last he made up his mind to go abroad. He heard through an advertisement of an opening in a tea plantation in Assam (Assam, Mildred! You know where it is, of course), and though he hated the idea of leaving home, he thought it was the right thing to do. Well, he went. It was a long and expensive journey, and when he arrived he found that things were not at all as they had been represented. I can’t enter into details, but the advertisement had been one of those cruel frauds by which young men are tempted abroad, and robbed of time and money. My friend was clever enough to see through the deception, and refused to have anything to do with the business. That was all right so far as it went, but there he was, alone in a strange land, not knowing where to turn, or what to do to earn a livelihood. It was just about this time that the planters in Ceylon were beginning to grow the cinchona-tree, from the bark of which the medicine known as quinine is made; and it happened one day that my friend overheard two gentlemen discussing the prospects of the crops and speaking very enthusiastically about it. He made inquiries in as many directions as he could, and finally decided to go south to Ceylon and prospect. He had some money of his own, and he was fortunate enough to meet a man who had been in the island for years, and who had valuable experience. They bought an estate between them, planted it with cinchona, and worked hard to cultivate it; and it is very hard, Mildred, for an Englishman to work in the open air in those tropical countries! It was a difficult crop to raise, and misfortune befell all the estates around. The roots ‘cankered’, the leaves turned red and dropped off, so that the trees had to be uprooted, and very little if any of the bark could be used. My friend’s estate, however, flourished more and more. His partner was a clever planter, and they were not content to leave the work to the care of an overseer, but looked after it themselves, night and day. There was not a single precaution which they neglected; not an improvement which they left untried, and as I say the place flourished—people talked about it—it became well known in the island. It was all the more valuable because of the failure of the other estates, and the sum which the estate would realise, if all went well, would be a fortune—large enough to provide both partners for life.

“Imagine how they felt, Mildred! How eager they were; how delighted. They had been away from home for years by this time, and were longing to return. They had each their own castle in the air, and it seemed as if this money would build it on solid earth. For some time everything flourished, then—one morning—”

Miss Margaret paused, and drew a difficult breath; Mildred stared at her with dilated eyes.

“My friend wrote me all about it. They had finished breakfast and strolled out together, talking of what they would do when the next few weeks were over, and the money was paid down. They were to buy presents in Colombo, take passages in the first steamer, and come home laden with spoils. The partner—his name was ‘Ned’—was picturing the scene which would take place at his home when he distributed the treasures which he had bought for his sisters—amethyst rings, tortoise-shell brushes, brass ornaments. He walked on ahead, gesticulating, and waving his hands in the air. Suddenly he stopped short, started violently, and stared at one of the carefully-guarded cinchona-trees.

“‘What is it, Ned?’ cried his partner, and at that the other turned his face. It had been all bright and sparkling a moment before. It was changed now—like the face of an old, old man. My friend looked and saw: the leaves were shrivelling—it was the beginning of the red blight!”

Miss Margaret jumped up from her seat and began to pace the room. Her voice quivered; her eyes had a suspicious brightness; while Mildred was undisguisedly tearful.

“Oh, Mardie! How awful! Oh, the poor, poor fellows! What did they do?”

“There was nothing to be done. They knew that by experience. The blight would spread and spread until the whole estate was destroyed. They could do nothing to stop it. They went back to the bungalow and sat there all day long—without speaking a word or lifting their eyes from the ground. All the years of hard, unceasing work had been for nothing—”

Mardie stopped abruptly.

“And after—afterwards?”

Mardie stood with her back to her companion, as if avoiding her glance. Her voice had a curiously tired, listless expression.

“Oh!—they dug up the ground to plant tea, and began life over again.”

“But, Mardie, dear, don’t be so sorry! It was terribly hard, but after all it is over, and it did not affect your own personal happiness!”

Mardie moved the ornaments on the dressing-table with nervous fingers.

“It is getting late,” she said. “Put on your hat, Mildred, and let us have a stroll in the garden before it is dusk.”

Chapter Five.

Sunshine Again!

The next day brought reassuring news of Robbie, who had had a good night, and was distinctly better. Mildred was devoutly thankful; but now that the strain of anxiety was relieved, the loneliness of her position began to weigh upon her with all the old intensity. She grew tired of reading and writing letters, and the silence of the big, empty house weighed upon her spirits.

“Three days—and already it seemed like a month! Then what will a month feel like? and two months?” she asked herself in a tremor of alarm. “It is all very well for Mardie to say, ‘Take one day at a time, and don’t worry about the future.’ She wouldn’t find it so easy in my place! Bertha might send me a letter! I didn’t expect her to write the first day she was at home, but she might have managed it the second, under the circumstances!”

Miss Margaret was engaged with callers; the servants busy at their work. Mildred was at her wits’ end to know what to do with herself. She flattened her face against the window, and stared gloomily down the drive.

“Two more visitors coming to see Mardie. That means another half-hour at the least before I can go downstairs to have tea. An old lady, and a young one in a light dress, and a hat with pink roses. She doesn’t look a bit nice!” pronounced Mildred in critical spirit; “I shall dress much better than that when I am grown up. Her boots are awful!—old, shabby things beneath a grand dress. I would rather spend less on finery and have respectable feet. The old lady is as broad as she is long; her bonnet is crooked! Why doesn’t the girl put it straight before they go into the house? I wouldn’t allow my mother to be so untidy! She looks fearfully hot!”

Mildred stared at the old lady and her daughter until a sweep of the drive hid them from sight, and felt more lonely than ever when they had disappeared. For ten minutes or more not another soul could be seen, then the postman came briskly trotting towards the house. Mildred heard the peal of the bell, and became fired with curiosity to know whether any of the letters were for herself. Probably, almost certainly; for this was the post from the south, in which direction almost all the girls had their homes. There might be one from Bertha among the number. How aggravating to know that they were lying in the letter-box at the present moment, and to be obliged to wait until the visitors took their departure before Mardie could come out and unlock it.

“He had five or six in his hand; some of them must be for me. Suppose now, just suppose I could have whatever I liked—what should I choose? A letter from a lawyer to say I had come in for a fortune of a million pounds? That would be rather nice. What should I do with it, I wonder? Mother couldn’t come away with me just now, which would be a nuisance. I think I would travel about with Mardie, and look at all the big estates that were for sale, and buy one with a tower and a beautiful big park, with deer, and peacocks, and sun-dials on the grass. I’d go up to London to buy the furniture,—the most artistic furniture that was ever seen. The drawing-room and library should be left for Mother to arrange, but I’d finish all the rest, so that she could come the first moment it was safe. I’d have a suite of rooms for myself next to hers. A big sitting-room,—blue,—with white wood arches over the windows; dear little bookcases fitting into the corners, and electric lights hanging like lilies from the wall. Opening out of that there would be another little room where I could amuse myself as I liked, without being so awfully tidy. I’d do wood-carving there, and painting, and sewing. I might have a little cooking-stove in one corner to make toffee and caramels whenever I felt inclined, but I’m not quite decided about that. It would be rather sticky, and I could always go down to the kitchen. Then there would be my bedroom—pink,—with the sweetest little bed, with curtains draped across from one side of the top to the other side of the bottom. I saw one like that once, and it was lovely. I’d have all sorts of nice things out-of-doors, too—horses for Mother and myself to ride, and long-tailed ponies for the children. I’d like to send the little ones to boarding-schools, but I am afraid Mother wouldn’t consent to that; but they could have governesses and tutors, and a school-room right at the other end of the house. I should have nothing to do with teaching them, of course. I should be called ‘The Heiress of the Grange’, and all the village children would bob as I passed by. It would be rather nice. I would give them a treat in the grounds every year on my birthday, and they would drink my health. It seems a great deal of happiness for a million pounds. I wish I had someone to leave it to me—an old uncle in Australia or Africa; someone I had never seen, then I could enjoy it without feeling sorry.”

The prospect of inheriting a million pounds was so engrossing that it was with quite a shock of surprise that Mildred perceived the old lady and her daughter retracing their steps down the drive. Downstairs she flew, two steps at a time, and discovered Miss Margaret emptying the letter-box of its contents.

“Oh, Mardie, I saw the postman coming, ages ago! I’ve been dying to get that key for the last half-hour!”

“Have you, really? I am sorry; but you are well repaid. Three letters for you, and only one for me. You are fortunate to-day.”

“Bertha—Carrie—Norah!” Mildred turned over the envelopes one by one, and skipped into the drawing-room with dancing tread. “Now for a treat. I love letters. I shall keep Bertha’s to the last, and see what these other young ladies have to say for themselves.”

She settled herself comfortably in an armchair, and Miss Margaret, having read her own note, watched her with an expression of expectant curiosity. The two first letters were short and obviously unexciting; the third contained several inclosures at which Mildred stared with puzzled eyes. One looked like a telegram, but the flash of fear on her face was quickly superseded by amazement, as she read the words of the message. Last of all came Bertha’s own communication, and when that had been mastered the reader’s cheeks were aglow, her eyes bright with excitement. She raised her head, and there was Mardie staring at her from the other end of the room, and smiling as though she knew all about it.

“Oh, Mardie, the most wonderful thing! It’s from Mrs Faucit; an invitation to go and stay with them for a whole month! She has written to Mother, and here is a telegram which came in reply, saying that she is delighted to allow me to accept. I am to go at once. There is a note from Mrs Faucit as well as one from Bertha. So kind! She says they are to be at home for a month before taking the girls to Switzerland for a few weeks, and that it will be a great pleasure to have me. I wish—I wish—”

She stopped short, staring at Miss Margaret with an expression of comical penitence. Even when that lady inquired, “Well, what do you wish now, you dissatisfied child?” it was several minutes before she replied.

“Nothing; only when you have made a great fuss about a thing, and it turns out in the end that you haven’t to do it after all, you feel rather—small. I wish now that I had been good and resigned; I should feel so much more comfortable. I suppose my going won’t make any difference to you, Mardie?”

“Only this, that I shall hurry through my work as quickly as possible, and go away now instead of waiting until my sister returns. I am delighted, Mildred! it’s just as nice as it can be. I have had a letter from Mrs Faucit, too. She asks you to go at once, but I am not sure if we can manage that.” She hesitated, looking at her pupil with uncertain eyes. “She is so pretty, bless her!” she was saying to herself, “that she always manages to look well; but she is shabby! I should think her mother would wish her to have one or two new dresses before she goes. I must speak about it. You see, Mildred,” she said aloud, “I am thinking about your clothes. You will probably be asked to a great many tennis and garden parties while you are at The Deanery, and you will have to be more particular than at school. Do you think you can go with what you have, or shall we get something new? We might call at the dressmaker’s to-morrow.”

Mildred shook her head.

“Oh, no! I must go as I am, Mardie, or stay at school. I wouldn’t ask Mother for money just now, not for the world. There will be doctors’ bills, and a dozen extra expenses to meet, and she has a hard enough time as it is. I can buy some little things—shoes, and gloves, and a sailor hat—with the money I have: nearly twenty-five shillings altogether; but it is no use thinking about a dress. I shall do very well. I have the blue crepe, and the brown, and the dyed green, and this good old serge to wear with blouses. If I see people examining my clothes, I shall shake my hair all over my back, and stare as hard as I can, so that they will be obliged to turn away... If we go into town to-morrow, I could go on Wednesday, couldn’t I?”

“Say Friday, dear; it will give us a little more time.” For, to herself, Miss Margaret was saying: “I will engage that clever little sewing-woman to come in for a couple of days and look over her dresses. She is quite right to consider her mother’s purse, but she will feel her own shortcomings when she is among the Faucit’s friends. I must do all I can to make it easier for the child. There is one comfort, she is easy to dress.”

Mildred danced away to answer her friend’s letter in overflowing spirits. She had never before paid a visit on her own account, and it seemed delightfully grown-up to be going to a strange house by herself. A Deanery, too! There was something so imposing about the sound. One Deanery was worth a dozen ordinary, commonplace houses, just as Bertha was worth a hundred other friends. Dear, darling Bertha—this was her idea, of course! It took three sheets of note-paper to contain all Mildred’s expressions of delight.

The next day was set apart for the shopping expedition, an occasion calling for anxious consideration. At Miss Margaret’s suggestion Mildred drew out a list of the articles which she wished to purchase out of her twenty-five shillings of capital. It was neatly written on a sheet of note-paper, with descriptive notes attached to the various items, and red lines ruled between, so that it presented quite a superior appearance. The list ran as follows:—

New shoes (pretty ones this time,—not thick).

Slippers (with buckles).

Gloves (light and dark).

Ribbons.

Something to do up the hat.

Sashes.

Lace things for evening.

Scent.

P.F.M.

Miss Margaret read the list, and shook with laughter.

“Are you sure there is nothing else?” she inquired. “How much more do you expect from those poor twenty-five shillings? They can never, by any possibility, be induced to buy so much. What is the mysterious P.F.M.?”

“A necessity; can’t be crossed out. Oh, dear,” groaned Mildred, “what a bother it is!” She tore off half a sheet of paper this time, and did not attempt any decorations. Then she went over the items one by one, sighing heavily as she did so.

“I can’t do without shoes; I can’t do without slippers; I can’t do without gloves. I might get silk ones, of course, but they make me feel creepy-creepy all over. I daren’t touch anything when I have them on. I should look like one of those wax figures in shop windows, with my arms sticking out on either side! I can’t do without ribbons; I can’t do—well, I suppose I could wear the old hat as it is, and do without scent, and a sash, and laces, or any single pretty thing to put on at night, but I don’t want to! They are the most interesting things... Oh, dear, here goes!” and list number two was dashed off in disgusted haste.

Shoes.

Slippers.

Sailor Hat.

Gloves. P.F.M.

“That’s short enough now! All the fripperies cut out, and the dull necessities left. I can get these, I suppose, Mardie?”

Miss Margaret believed that she could “with care”, whereupon Mildred wrinkled her saucy nose, and said she should never have any respect for twenty-five shillings again, since it appeared that so very little could be obtained in exchange.

The shopping expedition was a great success, however, in spite of all drawbacks. The purchases were pretty and good of their kind, and Mildred felt an agreeable sense of virtue in having chosen useful things rather than ornamental. She had still a little plan of her own which she was anxious to execute before returning home, and took the opportunity to make a request while waiting for change in a large drapery establishment.

“I want to go to another department, Mardie. Do you mind if I leave you for a few minutes?”

“Not at all. I have some little things to get too. Suppose we arrange to meet at the door in ten minutes from now?”

Mildred dashed off in her usual impetuous fashion, but presently came to a standstill before a long, glass-covered counter, on which was displayed a fascinating assortment of silver and enamel goods. For the first few moments the assistant in charge took no further notice than a glance of kindly admiration. School-girls in short dresses, and with clouds of golden hair hanging loose round their shoulders, are not given to the purchase of valuable articles such as these; but Mildred proceeded to ask the price of one thing after another, with an air of such serious consideration as made it seem likely that she was to be the exception to the rule.

The glass case was opened, little heart-shaped trays and boxes brought forth, and such rhapsodies indulged in concerning silver-backed mirrors that the assistant felt certain of a sale. She was stretching underneath the glass to reach a mirror of another pattern, when Mildred suddenly glanced up at a clock, ejaculated “Oh, I must go! Thank you so much!” and rushed off at full speed in another direction. The ten minutes were nearly over, and Mildred had not executed the private business which she had on hand. She turned the corner where parasols hung in tempting array, passed the fancy work with resolute indifference, and making a dash for the perfumery counter came into collision with a lady who was just turning away, parcel in hand.

The lady lifted her eyes in surprise. By all that was mysterious and unexpected, it was Miss Margaret herself! Mildred blushed, Mardie laughed.

“What are you doing here, Ubiquitous Person?” she cried, but immediately turned aside in tactful fashion, and made her way to the door.

No reference to this encounter was made on either side, but later in the day a comical incident occurred. When Miss Margaret went upstairs to dress for dinner, she found a small box lying upon her dressing-table, on the paper covering of which an inscription was written in well-known, straggly writing:

“Mardie, with heaps of love and many thanks, from Mildred.”

Inside the box was a bottle of White Rose perfume, at the sight of which Miss Margaret began to laugh with mysterious enjoyment. When Mildred appeared a few minutes later, blushing and embarrassed, she said never a word of thanks, but led her across the room towards a table which had been specially devoted to her use. Mildred stared around, and then began to laugh in her turn, for there lay a parcel of precisely the same shape and size as that which she had addressed a few minutes earlier, and her own name was written on the cover.

“Great minds think alike!” cried Mardie. “So this is the explanation of that mysterious ‘P.F.M.’! But what are the thanks for, dear?”

“Oh, everything! You are so nice, you know, and I’ve been so nasty!” said Mildred.

Chapter Six.

The Journey to the Deanery.

Friday arrived in a bustle of work and excitement. For the last two days Miss Margaret’s little sewing-woman had taken possession of the work-room, and Mildred’s well-worn dresses had been sponged and pressed, with such wholesale renewals of braid and buttons as brought back a remembrance of their lost youth. And now all was ready. Letters from home announced further improvements in Robbie’s condition; Miss Margaret was radiant in the prospect of her own holiday; there was nothing to shadow Mildred’s expectation, and it really seemed as if it had been worth while having those days of disappointment and anxiety, so delightful was the reaction.

Miss Margaret and her pupil had a great many nice things to say to each other in the few minutes before the train steamed out of the station. Mildred had said “thank you” so many times during the last few days, that there was little left to be done in that direction, but she was full of warm-hearted affection.

“I shall always remember how good you have been to me, Mardie. I think you are the nicest person in the world next to Mother. I shouldn’t mind being old if I could be like you.”

“But my dear child, I don’t consider myself old at all! When you get to my age you will have discovered that you are just beginning to be young. I wonder if,—when,—if you would—”

Mardie checked herself suddenly, and Mildred, scenting one of those secrets which are the delight of a school-girl’s existence, called out an eager: “What? What? What?”

“Oh, nothing! I only wondered if you would be very much shocked if I were betrayed into doing something very foolish and youthful one of these days.”

Mildred stared down from the altitude of the carriage window.

What could Mardie mean? There was no secret about her age. It was inscribed in every birth-day-book in the school, and thirty seemed venerable in the estimation of fourteen. It did occur to the girl at this moment that Miss Margaret looked unusually charming for an elderly lady—those sweet eyes of hers were sweeter than ever when lighted by a happy smile.

“I am sure you will never be foolish, Mardie!” she said reassuringly, and then the engine whistled, the guard waved his flag, and there was only time for a hurried embrace before the train was off.

So long as the platform remained in sight Mildred’s head was out of the window; then she sat down to find herself confronted by the mild-faced old lady into whose charge she had been committed.

She was an ideal old lady so far as appearances went. Her hair was white as snow; her chin nestled upon bows of lavender ribbon, and her face beamed with good nature; nevertheless Mildred found her fixed scrutiny a trifle discomposing, and stared out of the window by way of escape. For ten minutes on end the old lady gazed away with unblushing composure, then suddenly burst into conversation.

“Dear me, my love, you have a great deal of it! Are you not afraid that it may injure your health?”

Mildred fairly jumped with astonishment.

“Afraid? Of what? I beg your pardon—I don’t understand—”

“Your hair, my dear!—so much of it. They say, you know, that it saps the strength. A young friend of mine had hair just like yours—you remind me very much of her—and she died! Consumption, they called it. The doctors said all her strength went into her hair!”

Mildred laughed merrily.

“Oh, well! it’s quite different with me, I have plenty of strength left over for myself. I am as strong as a horse, and have hardly been ill a day in my life.”

“Dear! Dear!” ejaculated the old lady. “And with that complexion too—pink and white. Now I should have been afraid—”

She fell to shaking her head in lugubrious fashion, and watched the girl’s movements with anxious scrutiny.

“Do you think you are quite wise to sit next the window, love?” she asked presently. “You look a little flushed, and there is always a draught. Won’t you come over and sit by me? Just as you like, of course; but I assure you you can’t be too careful. I noticed that you cleared your throat just now. Ah, that’s just what a young friend of mine used to say, ‘It’s only a little tickling in my throat,’ but it grew worse and worse, my dear, till the doctors could do nothing for her. I am always nervous about colds—”

“She has been very unfortunate in her ‘young friends’!” commented Mildred to herself, but she made no reply, and the old lady waited fully two minutes before venturing another remark.

“Your—er—aunt seems a very sweet creature, my dear! You must be sorry to part from her.”

“I am. Very! But she is not my aunt.”

“You don’t say so! Not a sister, surely? I never should have thought it—”

“She is not a sister either.” (Now, what in the world can it matter to her whether we are relations or not! I suppose I had better tell her, or she will be suggesting ‘mother’ next). “She is one of the school-mistresses. I am just leaving school.”

The old lady appeared overwhelmed by this intelligence. Her placid expression vanished, her forehead became fretted with lines, and she looked so distressed that it was all Mildred could do to keep from bursting into a fit of laughter.

“A boarding-school! Oh, my dear!” she cried. Then in a tone of breathless eagerness, “Now tell me—quite in confidence, you know, absolutely in confidence,—do they give you enough to eat? Oh, my love, I could tell you such stories—the saddest experiences—”

“Dear young friends of her own, starved to death! I know,” said Mildred to herself, and she broke in hastily upon the reminiscences, to give such glowing accounts of the management of Milvern House as made the old lady open her eyes in astonishment.

“Four courses for dinner, and a second helping whenever you like. Now really, my dear, you must write down the address of that school for me. I have so many young friends. And have you any idea of the terms?”

She was certainly an inquisitive old lady, but she was very kind-hearted, and when one o’clock arrived she insisted upon Mildred sharing the contents of her well-filled luncheon-basket. Her endless questions served another purpose too, for they filled up the time, and made the journey seem shorter than it would otherwise have done. It came as quite a surprise when the train steamed into the station at B—, and Mildred had not time to lower the window before it had come to a standstill. She caught a glimpse of her friends upon the platform, however, and in another minute was out of the carriage, waving her hand to attract attention.

Bertha and Lois were accompanied by a lady who was so evidently their mother that there could be no doubt upon the subject. She had the same pale complexion and dark eyes, the same small features and dainty, well-finished appearance. As Mildred advanced along the platform to meet the three figures in their trim, tweed suits, she became suddenly conscious of flying locks, wrinkled gloves, and loose shoe-laces, and blushed for her own deficiencies. She could not hear Bertha’s rapturous “There she is! Look, Mother! Do you wonder that we call her the ‘Norse Princess?’” or Mrs Faucit’s “Is that Mildred? She looks charming, Bertha. It is a very good description;” but the greetings which she received were so cordial as to set her completely at ease.

On the drive home Mrs Faucit leant back in her corner of the carriage, and listened to the conversation which went on between the three girls in smiling silence. She soon heard enough to prove that it was the attraction of opposites which drew the stranger and her own daughters so closely together, but though Mildred’s impetuosity was a trifle startling, she was irresistibly attracted, not only by her beauty, but by the frank, open expression of the grey eyes.

“Plenty of spirit,” she said to herself, “as well as honest and true-hearted! Miss Chilton was right. She will do the girls good. They are a little too quiet for their age. I am glad I asked her—”

“What did you think, Mildred, when Mother’s letter arrived with the invitation?” Lois asked, and Mildred clasped her hands in ecstatic remembrance.

“Oh-h, I can’t tell you! I had just been longing for a letter, and wondering what sort of one I would have if I could chose. I decided that I would hear that I had inherited a fortune, and I was just arranging how to spend it when your letter arrived. Lovely! lovely! I wanted to come off the next day, but Mardie objected. She has been so good to me, and I was a perfect horror for the first few days. I was ashamed of myself when your invitation came. Oh, what a funny old place this is! What curious houses—what narrow little streets!”

Mrs Faucit smiled.

“We are very proud of our old city, Mildred,” she said. “We must show you all the sights—the walls, and the castle, and the old streets down which the mail-coaches used to pass on their way to London. Some of them are so narrow that you would hardly believe there was room for a coach. These newer streets seem to us quite wide and fashionable in comparison.”

Even as she was speaking the carriage suddenly wheeled round a corner, and turned up a road leading to the Deanery gates. Mildred was not familiar with the peculiarities of old cathedral cities, and she stared in bewilderment at the sudden change of scene. One moment they had been in a busy, shop-lined thoroughfare; the next they were apparently in the depths of the country—avenues of beech-trees rising on either side; moss growing between the stones on the walls; and such an air of still solemnity all around, as can be found nowhere in the world but in the precincts of a cathedral.

The Deanery itself was in character with its surroundings. The entrance hall was large and dim; furnished in oak, with an array of old armour upon the walls. In winter time, when a large fire blazed in the grate, it looked cheerful and home-like enough, but coming in from the bright summer sunshine the effect was decidedly chilling, and Mildred’s eyes grew large and awe-stricken as she glanced around. The next moment, however, Mrs Faucit threw open a door to the right, and ushered her guest into the most charming room she had ever seen.

Whatever of cheerfulness was wanting in the hall without was abundantly present here. One bay window looked out on to the lawn, and the row of old beeches in the distance; another opened into a conservatory ablaze with flowering plants, while over the mantel-piece was a third window, raising perplexing questions in the mind concerning the position of the chimney. Wherever the eye turned there was some beautiful object to hold it entranced, and Mildred was just saying to herself, “I shall have one of my drawing-rooms furnished exactly like this!” when she became aware that someone was seated in an armchair close to where she herself was standing.

“Well, Lady Sarah, we have brought back our little friend. This is Mildred. She has accomplished her journey in safety. Mildred, I must introduce you to our other guest, Lady Sarah Monckton.”

“How do you do?” murmured Mildred politely. Lady Sarah put up a pair of eye-glasses mounted on a tortoise-shell stick, and stared at her critically from head to foot. Then she dropped them with a sharp click, as if what she saw was not worth the trouble of regarding, and addressed herself to Mrs Faucit in accents of commiseration.

“My dear, you look shockingly tired! Train late, as usual, I suppose! It is always the way with this wretched service. I know nothing more exhausting than hanging about a platform waiting for people who are behind their time. Bertha looks white too. You have had no tea, of course. You must be longing for it?”

“Oh! I am always ready for tea, but we had only a few minutes to wait. Sit down, Mildred dear, you must be the hungry one after your long journey. James will bring in the tray in another moment.”

Mrs Faucit smiled in an encouraging manner, for she had seen a blank expression overspread the girl’s face as she listened to Lady Sarah’s remarks. “She speaks as if it were my fault!” Mildred was saying to herself. “How could I help it if the train was late? She never even said, ‘How do you do?’ I wonder who she can be?”

It was her turn to stare now, and once having begun to look at Lady Sarah, it was difficult to turn away, for such an extraordinary looking individual she had never seen before in the whole course of her life. Her face was wan and haggard, and a perfect net-work of wrinkles; but it was surmounted by a profusion of light-brown hair, curled and waved in the latest fashion; her skinny hands glittered with rings, and her dress was light in colour, and elaborately trimmed. She had a small waist, wide sleeves, and high-heeled shoes peeping out from beneath the frills of her skirt. If it had not been for her face, she might have passed for a fashionable young lady, but her face was beyond the reach of art, and looked pitifully out of keeping with its surroundings.