FROM WORKHOUSE TO

WESTMINSTER

WILL CROOKS, M.P.

Photo: G. Dendry.

WITH INTRODUCTION BY G. K. CHESTERTON

FOUR FULL-PAGE PLATES

CASSELL AND COMPANY, LIMITED

London, New York, Toronto and Melbourne

MCMIX

First Edition February 1907.

Reprinted March, June and August 1908.

January and November 1909.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

TO

Mrs. WILL CROOKS

THIS SLIGHT RECORD OF HER HUSBAND'S CAREER

IS DEDICATED BY THE AUTHOR

This record of the career of a man whom I have known intimately in his public and private life for over a dozen years can claim at least one distinction. It is the first biography of a working man who has deliberately chosen to remain in the ranks of working men as well as in their service. From the day in the early 'nineties when he was called upon to decide between a prospective partnership in a prosperous business and the hard, joyless life of a Labour representative, with poverty for his lot and slander for his reward, he has adhered to the principle he then laid down, consistently refusing ever since the many invitations received from various quarters to come up higher. There have been endless biographies of men who have risen from the ranks of Labour and then deserted those ranks for wealthy circles. Will Crooks, in his own words, has not risen from the ranks; he is still in the ranks, standing four-square with the working classes against monopoly and privilege.

This book would have been an autobiography rather than a biography could I have had my way. Nor was I alone in urging Crooks to write the story[Pg viii] of his life, as strenuous in its poverty as it has been in its public service. He always argued that that was not in his way at all—that, in fact, he did not believe in men sitting down to write about themselves any more than he believed in men getting up to talk about themselves.

So I have done the next best thing. Since the interpretation depends upon the interpreter, I have tried, in writing this account of his life, to make him the narrator as often as I could. Most of the incidents in his career I have given in his own words, mainly from personal talks we have had together during our years of friendship, sometimes by our own firesides, sometimes amid the stress of public life, sometimes during long walks in the streets of London. Nor do any of the incidents lose in detail or in verity by reason of many of those cherished conversations having taken place long before either of us ever dreamed they would afterwards be pieced together in book form.

Not to Crooks alone am I indebted for help in compiling this book. I owe much to members of his family, to my wife, and to other friends of his.

George Haw.

| PAGE | |

| Introduction | xiii |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Earliest Years in a One-Roomed Home | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| As a Child in the Workhouse | 8 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Schools and Schoolmasters | 16 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Round the Haunts of his Boyhood | 25 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| In Training for a Craftsman | 33 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Tramping the Country for Work | 43 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| One of London's Unemployed | 50 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| The College at the Dock Gates | 57 |

| [Pg x]CHAPTER IX. | |

| From the Cheering Multitude to a Sorrow-laden Home | 67 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| A Labour Member's Wages | 75 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| On the London County Council | 85 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Two of his Monuments | 96 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| The Task of his Life Begins | 105 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| The Man who Fed the Poor | 112 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Turning Workhouse Children into Useful Citizens | 119 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| On the Metropolitan Asylums Board | 128 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| A Bad Boys' Advocate | 134 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Proud of the Poor | 144 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| The First Working-Man Mayor in London | 154 |

| [Pg xi]CHAPTER XX. | |

| The King's Dinner—and Others | 166 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| The Man who Paid Old-age Pensions | 175 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| Election to Parliament | 186 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| Advent of the Political Labour Party | 195 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| The Living Wage for Men and Women | 202 |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| Free Trade in the Name of the Poor | 210 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| Preparing for the Unemployed Act | 219 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| Agitation in the House of Commons | 227 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

| The Queen Intervenes | 241 |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | |

| Home Life and Some Engagements | 252 |

| CHAPTER XXX. | |

| Colonising England | 264 |

| CHAPTER XXXI. | |

| The Revival of Bumbledom | 271 |

| [Pg xii]CHAPTER XXXII. | |

| Appeal to the People | 280 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. | |

| The Happy Warrior | 296 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. | |

| "The Happy Warrior" | 296 |

| INDEX | 303 |

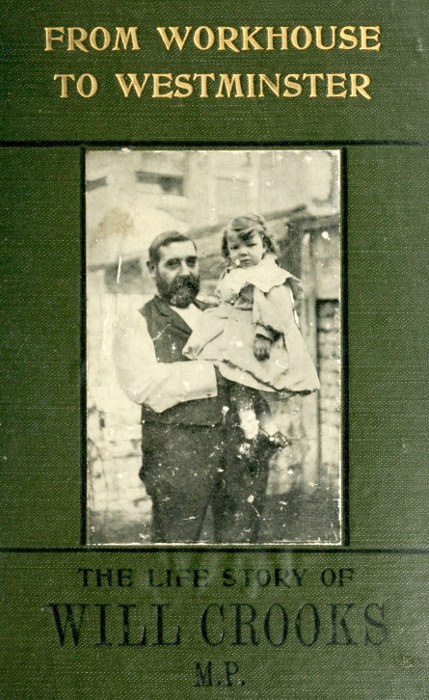

| Will Crooks, M.P. | Frontispiece |

| The Crooks Family | Facing p. 18 |

| Will Crooks Addressing an Open-Air Meeting at Woolwich | 192 |

| Mr. and Mrs. Will Crooks | 248 |

Mr. Will Crooks, as I know him in his own house at Poplar and in that other House at Westminster, always seems to me to be something far greater than a Labour Member of Parliament. He stands out as the supreme type of the English working classes, who have chosen him as one of their representatives.

Representative government, a mystical institution, is said to have originated in some of the monastic orders. In any case, it is evident that the character of it is symbolic, and that it is subject to all the advantages and all the disadvantages of a symbol. Just exactly as a religious ritual may for a time represent a real emotion, and then for a time cease to represent anything, so representative government may for a time represent the people, and for a time cease to represent anything. But the peculiar difficulties attaching to the thing called representative government have not been fully appreciated. The great difficulty of representative governments is simply this: that the representative is supposed to discharge two quite definite and distinct functions. There is in his position the idea of being a picture or copy of the thing he represents. There is also the idea of being an instrument of the thing he represents, or a message from the thing he represents. The[Pg xiv] first is like the shadow a man throws on the wall; the second is like the stone that he throws over the wall. In the first sense, it is supposed that the representative is like the thing he represents. In the second case it is only supposed that the representative is useful to the thing he represents. In the first case, a parliamentary representative is used strictly as a parliamentary representative. In the second case a parliamentary representative is used as a weapon. He is used as a missile. He is used as something to be merely thrown against the enemy; and those who merely throw something against the enemy do not ask especially that the thing they throw shall be a particular copy of themselves. To send one's challenge is not to send one's photograph. When Ajax hurled a stone at his enemy, it was not a stone carved in the image of Ajax. When a modern general causes a cannon-ball to be fired, he is not understood to indicate that the contours of the cannon-ball represent in any exact way the curves of his own person. In short, we can in modern representative politics use a politician as a missile without using him, in the fullest sense of the word, as a symbol.

In this sense most of our representatives in modern representative government are merely used as missiles. Mr. Balfour is a missile. Mr. Balfour is hurled at the heads of his enemies like a boomerang or a javelin. He is flung by the great mass of mediocre Tory squires. He is flung, not because he is at all like them, for that he obviously is not. He is flung because he is a particularly bright and sharp missile; that is to say, because he is so very unlike the men who fling him. Here, then, is the primary paradox of representative [Pg xv]government. Men elect a representative half because he is like themselves and half because he is not like themselves. They elect a representative half because he represents them and half because he misrepresents them. They choose Mr. Balfour (let us say) half because he does what they would do and half because he does what they could never do at all.

We are told that the Labour movement will be an exception to all previous rules. The Labour movement has been no exception to this previous rule. The Labour Members, as a class, are not representatives, but missiles. Poor men elect them, not because they are like poor men, but because they are likely to damage rich men: an excellent reason. Labour Members are the exceptions among Labour men. As I have said, they are weapons, missiles, things thrown. Working-men are not at all like Mr. Keir Hardie. If it comes to likeness, working-men are rather more like the Duke of Devonshire. But they throw Mr. Keir Hardie at the Duke of Devonshire, knowing that he is so curiously shaped as to hurt anything at which he is thrown. Unless this is thoroughly understood, great injustice will necessarily be done to the Labour movement; for it is obvious on the face of it that Labour Members do not represent the average of labouring men. A man like Mr. J. R. Macdonald no more suggests a Battersea workman than he suggests a Bedouin or a Russian Grand Duke. These men are not the representatives of the democracy, but the weapons of the democracy. They are intended only to fulfil the second of those functions in the delegate which I have already defined. They are the instruments of the people. They are not the images of the[Pg xvi] people. They are fanatics for the things about which the people are good-humouredly convinced. They are philosophers about the things which are to the people an easy and commonplace religion. In a word, they are not representatives; they are not even ambassadors. They are declarations of war.

Such being the problem, we must reconcile ourselves to finding many of the Labour Members men of a definite and even pedantic class; men whose austere and lucid tone, whose elaborate economic explanations smack of something very different from the actual streets of London. This economic knowledge may be very necessary. It may remind us of our duties; but it does not remind us of the Walworth Road. It may enable a man to speak for the proletarians, but it does not enable a man to speak with them.

Now, if a man has a good rough-and-ready knowledge of the mechanics of Battersea and the labourers of Poplar; if the same man has a good rough-and-ready knowledge of the men in the House of Commons (a vastly inferior company); he will come out of both those experiences with one quite square and solid conviction, a conviction the grounds of which, though they may be difficult to define verbally, are as unshakable as the ground. He will come out with the conviction that there is really only one modern Labour Member who represents, who symbolises, or who even remotely suggests the real labouring men of London; and that is Mr. Will Crooks.

Mr. Crooks alone fulfils both the functions of the representative. He is a representative who, like Mr. Keir Hardie and the others, fights, cleaves[Pg xvii] a way, does something that only a man of talent could do, expresses the inexpressible, sacrifices himself. But also, unlike Mr. Keir Hardie, and the rest, he is a representative who represents. He is a picture as well as a projectile; he is the stone carved in the image of Ajax. He is really like the people for whom he stands. A man can realise this fact, merely as a fact, without implying any disrespect, for instance, to the Scotch ideality of Mr. Keir Hardie, or the Scotch strenuousness of Mr. John Burns. They are expressive of the English democracy, but not typical of it. The first characteristic of Mr. Crooks, which must strike anyone who has ever had to do with him, even for ten minutes, is this immense fact of the absolute and isolated genuineness of his connection with the working classes. To all the other Labour leaders we listen with respect on Labour matters, because they have been elected by labourers. To him alone we should listen if he had never been elected at all. Of him alone it can be said that if we did not accept him as a representative, we should still accept him as a type. I need not dwell, and indeed I feel no desire to dwell, on those qualities in Mr. Crooks which express just now the popular qualities of the populace. I feel more interest in the unpopular qualities of the populace.

The greatness of Mr. Crooks lies not in the fact that he expresses the claims of the populace, which twenty dons at Oxford would be ready to express; it is that he expresses the populace: its strong tragedy and its strong farce. He is not a demagogue. He is not even a democrat. He is a demos; he is the real King. And his chief characteristic, as I have suggested, is that he represents especially those popular good qualities[Pg xviii] which are unpopular in modern discussion. Will Crooks is to the ordinary London omnibus conductor or cabman exactly what Robert Burns was to the ordinary puritanical but passionate peasant of the Scotch Lowlands. He is the journeyman of genius. All that is good in them is better in him; but it is the same thing. Walt Whitman has perfectly expressed this attitude of the average towards the fine type. "They see themselves in him. They hardly know themselves, they are so grown."

In numberless points Mr. Crooks thus completes and glorifies the common character of the poor man. Take, for instance, the deep matter of humour: humour in which the English poor are certainly pre-eminent among all classes of the nation and all nations of the world. By all politicians, including Labour politicians, humour is only introduced exceptionally and elaborately; by all politicians the comic anecdote is led up to with dextrous prefaces and deep intonations, as if it were something altogether unique and separate. All politicians take their own humour very seriously. Mr. Crooks recalls the real life of the streets in nothing so much as in the fact that humour is a constant condition. He and the poor exist in a normal atmosphere of amiable irony. If anything, they have to make an effort to become verbally serious: something of the same kind of earnest that it costs an ordinary member of Parliament to become witty. Anyone who has heard Mr. Crooks talk knows that his permanent mood is humorous. He is never without a story, but his face and his mind are humorous before he has even thought of the story. He lives, so to speak, in a state of expectant reminiscence. The man who[Pg xix] said that "brevity was the soul of wit" told a lie; nobody minds how long wit goes on so long as it is wit. Mr. Crooks belongs to that strong old school of English humour in which Dickens was supreme; that school which some moderns have called dull because it could go on for a long time being interesting.

I have merely taken this case of popular humour as one out of a hundred. A similar case of Mr. Crooks's popular sympathy might be found in his pathos, which is equally uncompromising and direct. Even his political faults, if they are faults, against which so much criticism has for a time been raised, have still this pervading quality, that they are essentially the popular faults. This instinct for a prompt and practical and hand-to-mouth benevolence, this instinct for giving a very good time to those who have had a very bad time, this is the very soul of that immense and astonishing altruism at which all social reformers have stood thunderstruck: the kindness of the poor to the poor. This attitude may or may not be the great vice of the governors; there is no doubt that it is the great virtue of the people. The charity of poor men to poor men has always been spontaneous, irregular, individual, liable therefore in its nature to some faults of confusion or of favouritism.

It is the misfortune of Mr. Crooks that alone among modern philanthropists and social reformers he has really been the typical poor man giving to poor men. This quality which has been seen and condemned in him is simply the quality which is the common and working morality of the London streets. You may like it; you may dislike it. But if you dislike it you are simply disliking the[Pg xx] English people. You have seen English people perhaps for a moment in omnibuses, in streets on Saturday nights, in third-class carriages, or even in Bank Holiday waggonettes. You have not yet seen the English people in politics. It has not yet entered politics. Liberals do not represent it; Tories do not represent it; Labour Members, on the whole, represent it rather less than Tories or Liberals. When it enters politics it will bring with it a trail of all the things that politicians detest; prejudices (as against hospitals), superstitions (as about funerals), a thirst for respectability passing that of the middle classes, a faith in the family which will knock to pieces half the Socialism of Europe. If ever that people enters politics it will sweep away most of our revolutionists as mere pedants. It will be able to point only to one figure, powerful, pathetic, humorous, and very humble, who bore in any way upon his face the sign and star of its authority.

G. K. Chesterton.

FROM WORKHOUSE TO

WESTMINSTER

Difference between "Will" and "William"—Early Memories—Crying for Bread—An Aspersion Resented—A Prophecy that has been Fulfilled—Will earns his First Half-Sovereign.

Will Crooks!

In the little one-roomed home where he was born at No. 2, Shirbutt Street, down by the Docks at Poplar, it was the earnest desire of all whom it concerned that he should be known to the world as William Crooks. The desire found practical expression in the register of Trinity Congregational Church in East India Dock Road close by. Thither, within a few weeks of his birth, in the year 1852, he was carried with modest ceremony and solemnly christened by a name which everybody ever since has refused to give to him.

For somehow "William Crooks" does not sound like the man at all. Looking at it gives you no suggestion of the good-humoured, hard-headed Labour man, known as familiarly to his colleagues in the[Pg 2] House of Commons as he is to the great world of wage-earners outside by the shorter and more expressive name of Will Crooks.

Born in poverty, the third of seven children, Will Crooks, who is blessed with keen powers of observation and a good memory, can carry his mind back to the days before he was put into breeches.

"I remember before my fourth year was out," I have heard him tell, "something of the public rejoicings on the declaration of peace after the Crimean War. The following year was also memorable to me as the time I witnessed troops of soldiers marching to the East India Docks on the outbreak of the Mutiny."

Those were days of want and sorrow, as were many days that followed, in the little one-roomed home in East London. His father was a ship's stoker, who lost an arm by the starting of the engines one day when he was oiling the machinery as his vessel lay in the Thames.

"My very earliest recollections are associated with mother dressing father's arm day after day. I was only three years old at the time, but I know that all our privations dated from the day of this accident to my father, because he was forced to give up his work.

"It must have been with the aid of some good friends that at last my father got an old horse, hoping to earn a little by leading and carting; but nothing came of this small venture, and in time the horse had to be sold to pay the rent.[Pg 3] Almost the only work of any kind that father, being thus disabled, could get to do was an odd job as watchman.

"Those were very lean years indeed, and I don't know what we should have done but for mother. She used to toil with the needle far into the night and often all night long, slaving as hard as any poor sweated woman I have ever known, and I have known hundreds of such poor creatures. Many a time as a lad have I helped mother to carry the clothes she had made to Houndsditch. There were no trams running then, and the 'bus fare from Poplar to Aldgate was fourpence, a sum we never dared think of spending on a ride.

"My elder brother was as clever with the needle as many a woman, and often he would stay up all through the night with mother, helping her to make oil-skin coats."

One night, as the mother worked alone, young Will woke up in the little orange-box bedstead by the wall where he slept with a younger brother. Silently he watched her plying the needle at the table until he noticed tears trickling down her cheeks.

"What are you crying for, mother?"

"Never mind, Will, my boy. You go to sleep."

"But you must be crying about something, mother."

And then, in a doleful tone, she said, "It's through wondering where the next meal is coming from, my boy."

The little chap pretended to go to sleep soon[Pg 4] after; but now and again he would peep cautiously over the side of the box at his mother silently crying over her work at the table. And he puzzled his young head as to what it all meant.

"My mother crying because she can't get bread for us! Why can't she get bread? I saw plenty of bread in the shops yesterday. Do all mothers have to cry before they can get bread for their children?"

It was the first incident that made him think.

There was one morning, the morning after a Christmas Day of all times in the year, when his mother refused to let him or the others get up, even when she left the house. It was not until she returned after what seemed a long time, bringing with her a portion of a loaf, that she allowed them to get out of bed.

"It was many years afterwards before I learnt the reason for her strange conduct that Boxing Day morning. Then I found out that she had made a vow that her children should never get up unless there was some breakfast for them.

"We were so poor that we children never got a drop of tea for months together. It used to be bread and treacle for breakfast, bread and treacle for dinner, bread and treacle for tea, washed down with a cup of cold water. Sometimes there was a little variation in the form of dripping. At other times the variety was secured by there being neither treacle nor dripping. The very bread was so scarce that mother could not afford to allow the three eldest, of whom I was one, more than three slices[Pg 5] apiece at a meal, while the four youngest got two and a half slices. Whenever we could afford to buy tea or butter, it was only in ounces. Once my brother and I were sent to buy a whole quarter of a pound of butter—it turned out that auntie was coming to tea—and on the way we speculated seriously whether mother was going to open a shop."

Perhaps the first occasion upon which Crooks as a lad showed something of that spirited resentment at aspersions on the poor which ultimately led him into public life was one that arose in a cobbler's shop. He was about eight years old, when his father sent him back with a pair of boots that had been repaired to ask that a little more be done to them for the money.

"I don't know what he wants for his ninepence," said the cobbler, referring to the lad's father; "but, there!"—throwing the boots to his man—"put another patch on. He's only a poor beggar."

There was an angry cry from the other side, of the counter. "My father's not a poor beggar!" shouted the boy. "He's as good a man as you, and only wants what he has paid for."

If the boy thought much of the father the father thought much of the boy. It had often been his boast that "Our Will will do things some day."

One little fancy of the old man's was brought to my notice the morning after Crooks was first returned to Parliament for Woolwich. His elder brother told me then of a little incident that took place over forty-five years before.

"We children were playing in the home together when young Will said something which made the dad look up surprised. And I heard him say to mother, 'That lad'll live to be either Lord Mayor of London or a Member of Parliament.'"

The poverty deepened and darkened in the little one-roomed home during Will's boyhood. It soon became impossible even to spend an odd ninepence on boot repairs. The mother met this emergency as she met nearly all the others. She became the family cobbler, as she had all along been the family tailor. Often would she go on her knees, hammer in hand, mending the boots. The children could not remember the time when she did not make all their clothes.

"God only knows, God only will know, how my mother worked and wept," says Crooks. "With it all she brought up seven of us to be decent and useful men and women. She was everything to us. I owe to her what little schooling I got, for, though she could neither read nor write herself, she would often remark that that should never be said of any of her children. I owe to her wise training that I have been a teetotaller all my life. I owe it to her that I was saved from becoming a little wastrel of the streets, for, as a Christian woman, she kept me at the Sunday School and took me regularly to the Congregational Church where I had been baptised.

"I can picture her now as I used to see her when I awoke in the night making oil-skin coats by candle-light in our single room. Youngster[Pg 7] though I was, I meant it from the very bottom of my heart when I used to whisper to myself, as I peeped at her from the little box-bedstead by the wall, 'Wait till I'm a man! Won't I work for my mother when I'm a man!'"

He thought he was a man at thirteen, when he could bring home to her proudly five shillings every week, his wages in the blacksmith's shop. There came a memorable Saturday night when, having worked overtime all the week and earned an extra five shillings, he was paid his first half-sovereign. He threw on his coat and cap excitedly and ran all the way home from Limehouse Causeway, the half-sovereign clenched tightly in his hand, until he burst breathlessly into the little room, exclaiming:

"Mother, mother, I've earned half a sovereign, all of it myself, and it's yours, all yours, every bit yours!"

With an Idiot Boy in the Workhouse—Life in the Poor Law School at Sutton—At Home Once More—A Fashionable Knock for the Casual Ward—A Bread Riot.

But we must go back a few years—to the evil day when, the father being a cripple, the family have to enter the workhouse.

The mother had before this been forced to ask for parish relief. For a time the Guardians paid her two or three shillings a week and gave her a little bread. Suddenly these scanty supplies were stopped. The mother was told to come before the Board and bring her children.

Six of them, clinging timidly to her skirt, were taken into the terrible presence. The Chairman singled out Will, then eight years of age, and, pointing his finger at him, remarked solemnly:

"It's time that boy was getting his own living."

"He is at work, sir," was the mother's timid apology. "He gets up at a quarter to five every morning and goes round with the milkman for sixpence a week."

"Can't he earn more than that?"

"Well, sir, the milkman says he's a very willing boy and always punctual, but he's so little that he[Pg 9] doesn't think he can pay him more than sixpence yet."

And the little boy looked furtively at the great man in the great chair, never dreaming that the time would come when he would occupy that chair himself, and that almost the first order he would issue from it would be one putting an end to the bad practice of making mothers drag their young children before the Board.

On that unhappy afternoon the Guardians, firm in their resolve not to renew the out-relief, offered to take the children into the workhouse. The mother said 'No' at first, marching them all bravely home again. Stern want forced her to yield at last. The day came when she saw the five youngest, including Will, taken from home to the big poorhouse down by the Millwall Docks. The crippled father was admitted into the House at the same time.

They were put into a bare room like a vault, the father and two sons, while the three sisters were taken they knew not where. There the lads and their dad spent the night and the next day until the doctor saw them and passed them into the main workhouse building. Then Will lost sight of his father, though he was permitted to remain with his young brother and share with him the same bed.

In the dormitory was an idiot boy, who used to ramble in his talk all through the night, keeping the others awake. Sometimes Will succeeded in coaxing his young brother off to sleep, but as for[Pg 10] himself, he would lie awake for hours listening to the strange talk of the idiot boy, and thinking of his mother. Often in the night the idiot boy would cry out for his own mother, leaving Will wondering who she was and where she was, and whether the plaintive cry of her imbecile child ever reached her ears in the night's stillness.

The lad was ravenously hungry all the time he spent in the workhouse. He often felt at times as though he could eat leather; yet every morning, when the "skilly" was served for breakfast, he could not touch it. Morning after morning, spurred on by hunger, he forced the spoon into his mouth, but the stomach revolted, and he always felt as though the first spoonful would turn him sick.

Somehow his father, away in the men's ward, got to know that young Will, who he knew could relish dry crusts at home with the best of them, was not able to eat the fare provided in the workhouse. The men occasionally got suet pudding, and one dinner-time the old man secretly smuggled his portion into his pocket. In the afternoon he made over to the children's quarters, hoping to hand it to Will. The pudding was produced, the lad's hungry eyes lighted up, when, behold! it was snatched away, almost from his very grasp. The burly figure of the labour master interposed between father and son. This was a breach of discipline not to be tolerated in the workhouse.

"But the boy's hungry, and this is what I've saved from my own dinner," argued the father (all[Pg 11] in vain). "You don't know how that boy likes suet pudding."

For two or three weeks the Crooks children were kept in the workhouse, before being taken away in an omnibus with other boys and girls to the Poor Law School at Sutton. Then came the most agonising experience of all to Will. They parted him from his young brother. In the great hall of the school he would strain his eyes, hoping to get a glimpse of the lone little fellow among the other lads, but he never set eyes on him again until the afternoon they went home together.

"Every day I spent in that school is burnt into my soul," he has often declared since.

He could not sleep at night nor play with the other boys, haunted as he was by the strange dread that he must have committed some unknown crime to be taken from home, torn from his young brother, and made a little captive in what seemed a fearful prison. The nights seemed endless, and were always awful. He whispered his fears on the fourth day to another Poplar boy who was there.

"Ah! you just wait until Sunday," said the other lad. "Every Sunday's like a fortnight."

When Sunday did come it proved to be one lasting agony. He thought time could not be made more terrible to children anywhere. They had dinner at twelve and tea at six, confined during the yawning interval in the dull day-room with nothing to do but to look at the clock, and then out of the window, and then back at the clock again.

During the week, after school hours, he hung about in abject misery all the time. From the day he went in to the day he left he never smiled. One afternoon he was loitering in the playground as the matron showed some visitors round.

"Who is that sad-faced boy?" he heard one of them ask.

"Oh, he's one of the new-comers," the matron answered. "He'll soon get over it."

The new-comer said to himself, "I wonder whether you would soon get over it if you had been taken from your mother and parted from a young brother?"

How long he stayed in the workhouse school he has never been able to tell. It could not have been very long in point of time, but to the sensitive lad it seemed an age. An indescribable burden was lifted from his shoulders when one day at dinner someone called him by his name.

He sprang to his feet.

"Go to the tailor's shop after dinner and get your own clothes."

"What for, sir?"

"You are going home!"

His heart leapt up. The boys crowded round him, wishing they were in his place. Poor miserable lads, he parted from them with feelings of the deepest pity.

At the gate he met his young brother and sisters again, and they were taken back to Poplar, to be welcomed with open arms by their mother. She had worked harder than ever to add to the[Pg 13] family income in order to justify her in going before the Guardians to ask that her children be restored to her own keeping.

Not until thirty-three years later could he command the courage to enter that same workhouse school again. Many changes for the good had been made, but the sight of the same hall, with the same peculiar odour, brought back the same old feeling of utter friendlessness and despair. And he saw in imagination a sad-faced boy sitting on the form, straining his eyes in the vain search for his young brother.

The mother had moved to a cheaper room when the children returned home from the workhouse school. It was in a small house in the High Street, next door to the entrance to the casual ward, with the main workhouse building in the rear. This was Will's home for the rest of his boyhood.

There, with the workhouse surrounding him as it were, he got daily glimpses of the misery that hovers round the Poor Law. Men and women would sit for hours huddled on the pavement in front of his home waiting for the casual ward to open. Will came bounding out of the house in the dull dawn to go to work as an errand boy one morning, when he kicked violently against a bundle of rags on the pavement.

There was a cry of pain in a woman's voice, and the lad pulled up sharp, filled with remorse:

"I'm so sorry, missus; I am really. I didn't see you."

"All right, kiddie. I saw you couldn't help it. I'm used to being kicked about the streets."

But the lad could not forget it. And when he came home at dinner-time, "Oh, mother," he said, "I kicked a poor woman outside our door this morning, and I wouldn't have done it for anything, had I known."

Sometimes a poor wayfarer would knock at the door, mistaking it for the entrance to the casual ward. In answer to a series of sharp raps one night Will raced to the door with the mother of another family who rented the front room. She got there first and opened it, to find a tramp on the step.

"Is this the casual ward?"

"The casual ward!" cried the woman in disgust, turning away and leaving Will to direct him. "That's a nice fashionable kind of knock to come with asking for the casual ward!"

It was from this house that he saw a bread riot in the winter of 1866, when he got the first of many impressions he was to receive of what a winter of bad trade means to a district of casual labour like Poplar. Hundreds of men used to wait outside the workhouse gates for a 2-lb. loaf each. The baker's waggon drove up with the bread one afternoon while they waited. The ravenous crowd would not let it pass into the workhouse yard. They seized the bread, frantically struggling with each other. Almost as fiercely they tore the bread to pieces when they got it and devoured it on the spot.

Sights like these of his childhood, with the shuddering memories of his own dark days in the[Pg 15] workhouse and the workhouse school, made him register a vow, little chap though he was at the time, that when he grew up to be a man he would do all he could to make better and brighter the lot of the inmates, especially that of the boys and girls.

Some children's dreams come true, and this was one of them.

The School of Life—Borrowed Magazines—Reading Dickens—Crooks's Humour and Story-Telling Faculty—Discovering Scott—Declaiming Shakespeare—Books that influenced him.

Little education of the ordinary kind came into Will's life as a lad. We have seen that he turned out before five o'clock every morning at eight years of age to take milk round for a wage of sixpence a week. Soon after coming out of the workhouse he got a job as errand boy at a grocer's at two shillings a week. At eleven he was in a blacksmith's shop, where he stayed until at fourteen he was apprenticed to the trade of cooper.

"In a sense, my training for becoming a servant of the people has been better than a University training," he tells you. "My University has been the common people—the common people whom Christ loved, and loved so well that He needs must make so many of us. The man trained as I have been amid the poor streets and homes of London, who knows where the shoe pinches and where there are no shoes at all, has more practical knowledge of the needs and sufferings of the people than the man who has been to the recognised Universities.

"I am the last to despise education. I have[Pg 17] felt the need of more education all my life. But I do protest against the idea that only those who have been through the Universities or public schools are fit to be the nation's rulers and servants. Legislation by the intellectuals is the last thing we want. See to what extremes it sometimes leads. There was a case under the Workmen's Compensation Act when eight leading lawyers argued for hours whether a well thirty feet deep was a building thirty feet high. Finally they decided solemnly that it was not. That was legislation by the intellectuals being carried out by the intellectuals."

He once complained in the House of Commons that Mr. Balfour—then Prime Minister—was using a dead language in answering a Labour Member's question. He had asked whether the Aliens Bill would take precedence over Redistribution. Mr. Balfour replied that the two things were not at all in pari materia.

"Will the right hon. gentleman please speak in English?" pleaded the questioner. "It is well known both inside and outside this House that I do not know Latin."

Mr. Balfour said that what he meant to convey was that you could not compare resolutions with a Bill, because a Bill involved a number of different stages, while the other dealt with the matter as one substantive question.

"A very loose translation," remarked a Member, amid the laughter of the House.

Crooks was learning life at the time other lads are usually learning Latin. And his knowledge of[Pg 18] life, carrying with it an unbounded sympathy with suffering, an intense love of truth and justice, has proved more useful to him and to the class he serves than any knowledge of a dead language would.

Yet it was a pleasure to him to go down to Oxford in the early part of 1906 to speak on the need for University men taking up social work. It was a greater pleasure to receive on his return the following letter from one in authority at Christ Church College:—

I am writing a line thanking you again for your kindness in coming and speaking here on Saturday. From all sides I hear nothing but commendation of your speech. There was a considerable number of our men present, and as I surveyed them I was glad to see that some who are really thinking about things were impressed.

Crooks always tells you that his best "schoolmaster" was his mother, the righteous working woman who could not read a line or write a word.

She and one of her boys spent nearly three hours one evening preparing a letter to a far-away sister, the mother painfully composing the sentences, the lad painfully writing them down. The glorious epistle was at last complete, the first great triumph of a combined intellectual effort between mother and son. Proudly they held the letter to the candle-light to dry the ink, when the flame caught it, and behold! the work of three laborious hours destroyed in three seconds. It was more than they could bear. Mother and son sat down and cried together.

THE CROOKS FAMILY.

(Will is the second child from the right, looking over his father's left shoulder.)

[Pg 19]"I have nothing but praise for my other schoolmaster," says Crooks. "I mean the schoolmaster at the old George Green schools in East India Dock Road. They were elementary schools then, and we paid a penny a week, though even that small sum for all of us meant a sacrifice for mother. The schoolmaster there was essentially a kind man. He had me under his teaching in the Sunday school as well as in the day school. During the few years I was with him prior to my workhouse days I learnt much that has been of service to me ever since."

Neither books nor papers found their way into Shirbutt Street. The first paper he remembers reading was The British Workman, brought occasionally to the little house in High Street just after the workhouse days. Then came a short spell of penny dreadfuls, from among which "Alone in a Pirate's Lair" stands out in memory riotous and reeking to this day.

Though the mother could not read herself, she encouraged her children by borrowing occasional magazines and inviting them to read the contents to her and her neighbours.

"I was about ten or eleven when The Leisure Hour and The Sunday at Home were started, and mother and the neighbours used to get these and ask us boys to read the stories to them.

"I owe something to an old man who went round the poor people's houses selling books. From him I got some of Dickens's novels. I suddenly found myself in a new and delightful world.[Pg 20] Having been in the workhouse myself, how I revelled in Oliver Twist! How I laughed at Bumble and the gentleman in the white waistcoat! I have seen that white waistcoat, pompous and truculent, administering the Poor Law many times since.

"After the unceasing hunger I experienced in the workhouse, you can guess how I sympathised with Oliver in his demand for more. I thought that a delightful touch in one of our L.C.C. day schools the other day. The teacher asked a class what books they liked best.

"'Oliver Twist,' came one little chap's answer.

"'Why?'

"'Because he asked for more.'"

This early reading of Dickens may have helped to develop his own quaint, rich humour. Will Crooks often reminds one of Charles Dickens. He knows the Londoner of to-day, his oddities, whimsicalities, his trials, humours, and sorrows, as thoroughly as Dickens knew the Londoner of fifty years ago. Many a time I have journeyed with him down to his home in East London, after he had finished a hard day's work in Parliament or on the London County Council, possibly having been defeated on some public question in a way that would make many men despair; and yet how easily he has put aside all the worries and work, and made the journey delightful by his unfailing fund of Cockney anecdotes. He is one of the rare story-tellers you meet with in a lifetime. The charm, too, of all his stories is that they never[Pg 21] relate to what he has read, but always to what he has heard or observed himself.

Some unknown friend at Yarmouth, who doubtless had heard him speak, seems to have been impressed by this ready way he has of taking his illustrations from the common things around him. Under the initials A. H. S. he sent the following "Limerick" to London Opinion:—

After Dickens the lad discovered Scott. "It was an event in my life when, in an old Scotch magazine, I read a fascinating criticism of 'Ivanhoe.' Nothing would satisfy me until I had got the book; and then Scott took a front place among my favourite authors.

"I was in my teens then, reading everything I could lay hands on. I used to follow closely public events in the newspapers. Not long ago I met a man in a car with whom I remonstrated for some rude behaviour to the passengers. He looked at me in amazement when I called him by his name.

"'Why,' he said, 'you must be that boy Will Crooks I knew long ago. Do you know what I remember about you? I can see you now tossing your apron off in the dinner-hour and squatting down in the workshop with a paper in your hand.'"

Crooks was still an apprentice when, as he[Pg 22] describes it, the great literary event of his life occurred.

"On my way home from work one Saturday afternoon I was lucky enough to pick up Homer's 'Iliad' for twopence at an old bookstall. After dinner I took it upstairs—we were able to afford an upstairs room by that time—and read it lying on the bed. What a revelation it was to me! Pictures of romance and beauty I had never dreamed of suddenly opened up before my eyes. I was transported from the East End to an enchanted land. It was a rare luxury to a working lad like me just home from work to find myself suddenly among the heroes and nymphs and gods of ancient Greece."

The lad's imagination was also fired by "The Pilgrim's Progress."

"I often think of that splendid passage describing the passing over the river and the entry into Heaven of Christian and Faithful. I can sympathise with Arnold of Rugby when he said, 'I never dare trust myself to read that passage aloud.'"

While in the blacksmith's shop he learnt many portions of Shakespeare, with a decided preference for Hamlet. Often in the little forge the men would say, "Give us a bit of Shakespeare, Will." The lad, nothing loath, would declaim before them, more often than not in a mock heroic strain that greatly delighted his grimy workmates.

Like many other members of the Labour Party, he was greatly influenced in his youth by the principles of "Unto this Last" and "Alton[Pg 23] Locke." Later in life he was set thinking seriously by a course of University Lectures on Political Economy delivered in Poplar by Mr. G. Armitage Smith.

Quietly he began building up a little library of his own, supplemented in later years by an occasional autograph copy from authors whose friendship he had made. Father Dolling, for instance, sent him a copy of his "Ten Years in a Portsmouth Slum," inscribed:—

Will Crooks.—The story of a kind of trying to do in a different way what he is doing.—With the author's best Christmas wishes, 1898.

In the flyleaf of this book Crooks keeps the following letter, received after his election to Parliament from the author's sister:—

Dear Mr. Crooks,—I have just seen the papers, and must send you a word of congratulation on your success. If, as I believe, the blessed dead are allowed to watch over and help us, I am sure my dear brother is thinking of you and praying that in your new sphere of usefulness you may be helped to do God's will.—Truly yours, Geraldine Dolling.

The book that he values most to-day is a pleasant little story for boys called "Joe the Giant Killer." It was given to him by the author, Dr. Chandler, Bishop of Bloemfontein, when rector of Poplar. The reason he values it so is because the printed dedication reads:—

"To WILL CROOKS, L.C.C.

In memory of many years

Of delightful comradeship in Poplar."

When, after the big victory in Woolwich, Crooks was able to add M.P. as well as L.C.C. after his name, there came among hundreds of other congratulations a cabled cheer from South Africa. It was signed "Chandler."

Proud of his Birthplace—Famous Residents at Blackwall—Memories of Nelson's Flagship—Stealing a Body from a Gibbet—A Waterman who Remembered Dickens.

Of many interesting days spent with Crooks in Poplar, one stands out as the day on which he showed me some of the haunts of his boyhood.

Poplar is always picturesque with the glimpses it gives of ships' masts rising out of the Docks above the roofs of houses. With Crooks as guide, this rambling district of Dockland, foolishly imagined by many people to be wholly a centre of squalor, becomes as romantic as a mediæval town.

It was not always grey and poor, as so many parts of it are to-day, though even these are not without their quaint and pleasant places.

We wended through several of its grey streets, making for the river at Blackwall. Everywhere women and children, as well as men, whom we passed greeted Crooks cheerily.

"Can you wonder so many of our people take to drink?" And he pointed to the shabby little houses, all let out in tenements, in the street where he was born. "Look at the homes they are forced to live in! The men can't invite their mates[Pg 26] round, so they meet at 'The Spotted Dog' of an evening. During the day the women often drift to the same place. The boys and girls cannot do their courting in these overcrowded homes. They make love in the streets, and soon they too begin to haunt the public-houses."

He changed his tone when we entered the famous old High Street that runs between the West India Docks and Blackwall. He pointed out the house where he spent many years of his boyhood after his parents moved from Shirbutt Street. The old home is associated with his errand-boy experiences. In those days he finished work at midnight on Saturdays, and knowing that his parents would be in bed, he often lingered in the High Street into the early hours of Sunday, playing with other lads who, like himself, had just finished work.

As we continued our way down the High Street together, he surprised me by his wonderful knowledge of the neighbourhood. Here was a Poplar man proud of Poplar. He told me that the now silent High Street was at one time a sort of sailors' fair-ground, like the old Ratcliff Highway. It was there, he said, that Poplar had its beginning, according to the historian Stow. There shipwrights and other marine men built large houses for themselves, with small ones around for seamen.

Not for these people alone were the houses built. Worthy citizens of London lived down there. Sir John de Poultney, four times Lord Mayor, lived[Pg 27] in a quaint old house in Coldharbour, at Blackwall, that stood until recently. This same house once formed the home of the discoverer, Sebastian Cabot. It was there that Cabot made friends with Sir Thomas Spert, Vice-Admiral of England, who also had a house at Poplar, and promised Cabot a good ship of the Government's for a voyage of discovery. And, later still, Sir Walter Raleigh is said to have been the tenant, and of course legend credits him with having smoked one of his earliest pipes there.

Gone are the old houses now, with the old traditions, the old gaiety, the old mad enthusiasm for the sea. In his day the Blackwall seaman was a dare-devil, efficient man, eagerly coveted by shipowners and captains alike. Never did a ship sail from Blackwall during Crooks's schooldays without most of the boys staying away from school, regardless of results to their skins the next morning, in order to join in the farewell cheering from the foreshore. The welcome home to the Blackwall ships was something to remember. It was always a bitter disappointment to the boys, since it robbed them of an opportunity of playing truant, if a ship came home and docked during the night, having come up, as the old tide-master used to say, and brought her own news.

Little remains to suggest the sea in Poplar High Street to-day. The old highway has lost its old glory. The old folks have forsaken the old homesteads. Of the few old buildings that remain, nearly every one has been cut up into small shops and tenements. One or two general dealers still[Pg 28] pose as ships' outfitters, and an occasional shop remains as a marine store, as though in a final feeble struggle to preserve the old traditions.

Crooks recollected well the period that costermongers thronged this riverside highway. They came about the time seamen were deserting it, so that the street for some time lost nothing of its noise or bustle. The day came when they, too, departed, seeking a more profitable field in Chrisp Street, on the northern side of East India Dock Road, where to this day they still hold carnival. That they carried away something of the seafaring character of their former highway is borne out by the nautical turn they give to some of their remarks.

"Here," cried a fish-dealer of their number the other day, holding aloft a haddock, "wot price this 'ere 'addick?"

"Tuppence," suggested a woman bystander.

"Wot! tuppence! 'Ow would you like to get a ship, an' go out to sea an' fish for 'addicks to sell for tuppence in foggy weather like this?"

As we passed down that portion of the High Street that skirts the Recreation Ground, Crooks pointed out the quaint old church of St. Matthias. He told me it was the oldest church in Poplar, built as a chapel-of-ease to the mother church of East London, St. Dunstan's. Then it was that all the parishes that now go to make up the teeming Tower Hamlets were comprised in Stepney. As the Port of London in those days was confined to the Pool and lower reaches and to the riverside[Pg 29] hamlets of the East End, that was why people born at sea were often entered as having been born in the parish of Stepney.

St. Matthias' Church afterwards became the chapel of the old East India Company. Poplar people sometimes call it that to this day. The Company's almshouses were near, and the chapel ministered to the aged almoners alone. According to tradition, the teak pillars in the church served as masts in vessels of the Spanish Armada. Upon the ceiling is the coat-of-arms of the original East India Company. Adjoining the church is the picturesque vicarage, where Crooks pointed out the coat-of-arms adopted by the United Company a hundred years later on the amalgamation with the New East India Company.

This chapel contains a monument to the memory of George Green, who stands out as Poplar's worthiest philanthropist. Schools, churches, and charities in Poplar to-day testify to his generosity. He was one of the owners of the famous Blackwall Shipbuilding Yard, that turned out some of the sturdiest of the wooden walls of England. They were proud in the shipyard of the Venerable and the Theseus, the former Lord Duncan's flagship at the battle of Camperdown, the latter at one time Nelson's flagship, in the cockpit of which his arm was amputated.

The people of old Poplar had at times unpleasant things to tolerate. Sometimes the pirates hung at Execution Dock, higher up the river, would be brought down, still on their gibbets, and[Pg 30] suspended for a long period at a place near Blackwall Point, as a warning to all seafarers entering the Port of London.

One of the old East India Company pensioners used to tell Crooks's father how one of the bodies hanging on a gibbet was stolen during the night, under romantic circumstances. An old waterman at the stairs was startled at a late hour by a young and ladylike girl coming ashore in a boat and asking him to lend a hand with her father, who, she said, was dead drunk in the bottom of the skiff. A youth was with her, and the waterman assisted them to carry the supposed drunken man to a carriage which was waiting. Not until the pirate's body was missing in the morning did the old waterman know the truth.

We reached the river ourselves from the Blackwall end of the High Street, while Crooks was giving me these entertaining glimpses into the past of his native Poplar. The sight of Blackwall Causeway and the river crowded with craft instantly reminded him of the last mutiny in the Thames, of which he has gruesome recollections, associated with bad dreams as a lad, caused by the knowledge that dead seamen lay in the building adjoining his home. It was here at Blackwall Point that the crew of the Peruvian frigate mutinied in 1861. He relates graphically how the eleven men who were shot dead on the ship were brought ashore and laid in the mortuary next his mother's house by the casual ward.

The old watermen at the head of the Causeway,[Pg 31] waiting to row people across to the Greenwich side, welcomed Crooks with a cheerful word as we approached. They were soon full of talk. The eldest told how he went to sea as a boy in the famous wooden ships turned out of Blackwall Yard. His aged companion remembered the stage coaches coming down from London to Blackwall. He was proud also of a memory of Queen Victoria's visit to the neighbourhood to see a Chinese junk.

The two ancient watermen soon overflowed with reminiscences. One remembered his grandfather telling how King George the Fourth would come down to see the ships built at Blackwall, and how on one occasion a sailor who had come ashore and got drunk took a pint of ale to his Majesty in a pewter and asked him to drink to the Army and Navy.

"Ah!" exclaimed the other, fetching a sigh; "but don't you remember that old Yarmouth fisherman who used to bring his smack round here from the Roads and sell herrings out of it on this very Causeway?"

"Remember! What do you think? That was the old man who would never keep farthings. In the evening, when he'd got a handful in the course of the day's trade, he would pitch them in the river for the boys to find."

"Likely enough," interposed Crooks. "I mudlarked about here myself as a lad."

The eldest of the ancient watermen would have it that this old boy from Yarmouth was the original[Pg 32] of Mr. Peggotty, and that it was at Blackwall Dickens first made his acquaintance. He said he had often seen Dickens himself about those parts.

We ventured a doubt.

"Why, bless my life!" he cried; "ain't I talked to him at the Causeway here many a time?"

This, of course, was unanswerable, so we asked what Dickens did when there.

The ancient waterman thought a moment.

"What did Dickens do?" he ruminated. "Now, let me see. What did Dickens do? I know: Dickens used to go afloat!"

The other declared that Dickens did more than that: he would often go into the fishing-smack.

We immediately assumed that it was the fishing-smack of the old Yarmouth salt that was meant. We were wrong. It was another "Fishing Smack," one of the quaint old taverns by the river still standing in Coldharbour.

Three years in a Smithy—Provoking a Carman—Apprenticeship—Winning a Nickname—Activity of an Idle Apprentice—"Not Dead, but Drunk"—A Boisterous Celebration—The Workman's Pride in His Work.

The three years in the blacksmith's shop in Limehouse Causeway, that commenced at the age of eleven after the errand-boy period, were years of hard work and long hours. The lad's working day began at six in the morning and often did not close until eight at night. Working overtime meant ten and twelve midnight before the day's work was done. He was paid for the overtime at the rate of a penny an hour.

He was kept hard at it all the time. Once, in the excitement of a General Election, in the days of the old hustings, he stole away from the forge for an hour. The smith had returned in his absence, and inquired angrily where he had been.

"Only to see the state of the poll."

"You'll know the state of the poll on Saturday, young fellow."

He did. A shilling was taken from his week's wages.

It was a heavy blow. It delayed a promised pair of new trousers. The need for a new pair[Pg 34] was constantly being brought to his notice in a more or less personal way. The biggest affront came from a tall boy at a shop he passed on the way home.

"Hi!" this youth would call after him. "Look at the kid wot's put his legs too far frew his trowsis!"

Nevertheless, the little chap in the short trousers was immensely proud to be at work. He would blacken his face before leaving for home so as to look like a working man.

Many a long day's search had he before getting that job. He spent hours one morning in calling at nearly all the shops in the two miles' length of Commercial Road between Poplar and the City. But nobody wanted so small a boy. On his way back, not yet wholly disheartened, he turned down Limehouse Causeway and peeped in at the smithy.

"Can you blow the bellows, little 'un?" he was asked.

Couldn't he; you just try him!

They tried him for an hour, then told him he was just the boy they wanted.

They got a lot of smiths' work in connection with the fitting out of small vessels in Limehouse Basin and the West India Docks. The first job at which Will assisted was on board the barque Violet.

The Causeway where the smithy stood was so narrow that carts could not pass each other. Two carmen driving in opposite directions met just outside the smithy door one afternoon. Neither would[Pg 35] give way, and they filled the air with lurid fancies. Young Will came out of the smithy and took the part of the one whom he believed to have the right on his side.

Seizing the bridle of the other driver's horse, he commenced to back the cart down the lane. The man's flow of language increased as he tried to get at the lad with his whip. Will dodged first to one side and then to the other, then under the horse's nose, eluding the lash every time. At last he got the cart backed right out of the lane, allowing the other driver to pass in triumph.

The enraged carman sprang down and chased the lad back into the smithy. Will had just time to spring behind the big bellows out of sight before the other appeared foaming at the door. With many oaths the man swore he would have vengeance on the boy some day, come what would.

Some years afterwards Crooks found himself at work in the same yard as his burly enemy, but time, which had made little difference to the man, had transformed the boy out of all recognition. Crooks asked him if he remembered the event.

"Yes; and if I came across that youngster to-day I'd break every bone in his body."

"I don't think you would, Jack," Crooks replied, preparing to take off his coat.

Then the carman understood.

In his third year at the smithy Will was getting six shillings a week, with something more than a penny an hour for overtime. Small though the wages were, they were very welcome at home;[Pg 36] and it meant a great deal to his mother when she sacrificed more than half this amount in the lad's best interest.

She was as determined that her boys should learn a trade as that they should learn to read and write. She took Will away from the smithy and his six shillings a week, when she found he was not to be taught the business but to be merely a smiths' labourer, and she apprenticed him to the trade of cooper at a weekly wage of half a crown.

"The sacrifice of a few shillings a week," says Crooks, "which mother made in order that I should learn a trade was only one of the many things she did for me as a boy for which I have blessed her memory in manhood many times. I really don't know now how she managed to feed us all, after losing my three-and-six a week. I know that she always put up a good dinner in a handkerchief for me to take to work. It may have got smaller towards the end of the week, like many of the men's. I remember one Monday dinner-time flopping down on a saw-tub and opening my handkerchief as the foreman passed.

"'That looks a good meal to begin the week on,' he said. 'I see how it is;—

Among the workmen was a thinker and [Pg 37]reformer far ahead of his times. It was dangerous in those days for workmen to give expression to advanced views, and as he was a married man he made no display of his opinions. He seems to have seen promise in young Will, for he talked to him freely on social and political matters, encouraging him to read by lending him books and papers, and inspiring him with an enthusiasm for the teaching of John Bright.

So much so, that at home Will was nicknamed Young John Bright. An uncle, looking in on the eve of the General Election of 1868, said jokingly, "Now, young John Bright, tell us all about what is going to happen." Nothing loath, Will delivered a long speech on the political situation, and foretold, among other things, that the Liberals would sweep the country, and that one of their first acts would be to disestablish the Church of Ireland. The prophecy, needless to say, was fulfilled.

Will was one of half-a-dozen apprentices in the coopering establishment. While still the youngest among them he made his mark by acting as spokesman in a sudden emergency. The lads thought they had a grievance under the piece-rate system. They went in a body to the head of the firm, the eldest primed with a well-rehearsed speech stating their case.

If Will saved the situation, he began by nearly bringing disaster upon it. It happened that the spokesman's father was an undertaker in Stepney, and that on Sundays the lad, with becoming gravity, frequently walked as a mute at funerals.

Just as the solemn procession of aggrieved apprentices was about to enter the office, the employer's wondering eye upon them through the window, Will called out in a stage whisper:

"Now, Joe, put on your best Sunday face!"

The fearful tension was broken. All the boys burst into laughter. The lads tumbled over each other in their eagerness to get outside the passage. When the head of the firm opened his door Will alone remained.

"What's all this about, Crooks?"

The youngest apprentice thereupon briefly ran over the lads' grievances, and on being asked why the deputation fled in laughter, he explained the meaning of the Sunday face.

The employer laughed as boisterously as his boys. He told Crooks to go back to work, promising that the lads should have fair play. That very day he issued orders placing the apprentices under better conditions.

One of the lads, with an unconquerable liking for lying in bed, had not turned up by nine o'clock on a certain morning. The other apprentices stole out with a barrow and went to his house with the object of wheeling him to work.

Half an hour later the lad rushed into the cooperage panting and dishevelled, his clothes torn, his hat missing.

"Done 'em!" he gasped, after the manner of Alfred Jingle. "I rushed out o' the back door, got over the wall, over the next wall, fell on a[Pg 39] flower-bed, man came out (such langwidge!), climbed his wall afore he could ketch me, landed clean on a dog kennel, dog tore me clothes, got over another wall—into the street at last—boys caught sight o' me, howling chase with barrow, woman let me run through her house, over another wall. Done 'em!"

Something more than laziness explained the occasional absence of others from work. Certain of the men would be missing for two or three days. During an unusually long absence of one of the older coopers, the men and lads rigged up a dummy figure, dressing it in whatever clothes of their own they could spare. They placed the dummy in an improvised coffin by the side of their missing comrade's bench, with an imitation tombstone at the head, bearing the inscription, "Not dead, but drunk."

The morning came when the delinquent turned up. A deep silence fell over the workshop as he entered. Men and apprentices alike suddenly appeared to be absorbed in work. The late-comer pretended not to see the effigy by his bench. With quiet deliberation he took off his coat, rolled up his sleeves, and lighted the furnace-fire. No one spoke. The old man brought two handfuls of shavings and piled them on the fire until it roared again. Then suddenly he seized the dummy figure and hurled it on the flames.

Everybody sprang forward to snatch his garments from the fire. One rescued his coat, another his vest, another his cap, another his muffler,[Pg 40] another his pair of boots, the old man belabouring each in turn.

"Ah!" he cried with a chuckle, as the singed garments were dragged away. "I knew that would find you all out."

Quaint and boisterous customs were observed when an apprentice was out of his time. The greater part of the day was given up by men and boys alike to revelry and horse-play.

The ceremonies began at about eleven o'clock in the morning, to be kept up for the rest of the day. First, the apprentice was seized and put into a hot barrel. Round him stood some fifty men and boys checking every attempt he made to get out, tapping him with hammers on the head and fingers and shoulders every time he made an effort to escape. When his clothes—the last he was to wear as an apprentice—had been singed in the barrel out of all further use, he would be dragged out and tossed in the air by about a dozen of the strongest men.

Only once did the employer try to stop these boisterous interludes. He never tried again. The men laid hold of him, and for about five minutes treated him to a vigorous tossing.

It then became the bruised and singed apprentice's privilege to pay for bread and cheese and drink. In the afternoon the men turned the yard into an imitation fair. Flags and bunting were put up and side shows were improvised. One feature was to persuade the fattest men to walk the tight-rope.

On the whole, Will had a happy time as an apprentice, working hard and laughing hard, more than once threatened with dismissal because his spirit of fun led him into mischief. He became a good craftsman, and to this day boasts of being as skilful at his own trade as any man. He attributes this to the old spirit of craftsmanship that held good in his day. One incident during his apprenticeship helped to make him take a pride in what he made with his own hands. An old workman in the shop, after finishing a piece of work, set it in the middle of the floor and walked round it admiringly several times.

"'Pon my honour, one would think you'd made a thousand-horse-power engine," said the apprentice.

"Never you mind, sonny," replied the old workman. "Whether it's a thousand-horse-power engine or not, I made it myself!"

"That is the spirit I want to see revived among workmen to-day," Crooks told the Labour Co-partnership Association in 1905, relating the incident at their annual exhibition at the Crystal Palace. He went on to say:

I want to see workmen proud of what they make with their own hands. That is impossible in many workshops to-day because of the soulless way in which they are conducted. Many workmen have got the idea they only exist for what other people can get out of them. I blame employers as much as workmen for this state of things. There are in the country some excellent employers. Unfortunately, they are becoming fewer. The individual employer is going out, and the limited liability company coming in,[Pg 42] having as its one object the making of profit, utterly regardless of the bodies or souls of the men or women from whom the profit is wrung. The result of running works and factories for company dividends only has destroyed the old school of masters and men, both of whom had a pride in their work, both of whom stamped their work with the mark of their own individuality.

To get back to a better state of things workmen must become their own masters, and the Co-Partnership Association is showing men the way. It is teaching them to live and work with and for each other. I want men who groan under the injustice of so much in our industrial system to understand that they can do much for themselves. By combination and co-operation they can run businesses of their own. But they must first take to the water before they can swim. It means discipline, but trade unionism has meant discipline. The administrative capacity of workmen can be developed to an enormous extent yet.

How are we going to train our men and women workers to take on the responsibilities of regulating their own lot in a better manner? Trade unionists are now learning that instead of spending money on strikes it is better to spend it in starting workshops of their own. The time has come when Labour leaders and others might well cease talking to the workers about their power and begin talking to them about their responsibilities.

The day after this speech he received the following letter from George Jacob Holyoake, a few months before that veteran co-operator passed away:—

"Against my will I was prevented from being present at the Crystal Palace, but that does not disqualify me from expressing my thanks for the wise and practical speech you made—in every way admirable."

Marriage—Dismissed as an Agitator—Home broken up—"On the Road"—Timely Help at Burton—Finding Work at Liverpool—Bereavement—Back in London—A Second Tramp to Liverpool—Feelings of an "Out-of-Work."

On a grey morning in the December of 1871 two young people came out of St. Thomas's Church, Bethnal Green, man and wife. Both were only nineteen years of age. The husband was Will Crooks; his wife the daughter of an East London shipwright named South.

They set up their home in Poplar, near the coopering yard where Will was employed. At first they had to be content with apartments; then came a small tenement; soon after a little house of their own.

It was fair and pleasant sailing for the first two or three years. He got a journeyman's full wages the first week he was out of his apprenticeship. It seemed as though he were to have an unbroken run of good fortune. The bright hopes soon collapsed.

Good craftsmanship and trade unionism, blended as they were in Crooks, made him rebel against certain conditions of his work. Finally he refused to use inferior timber on a job, and objected to[Pg 44] excessive overtime. Although the youngest among them, he addressed the workmen on the subject. A few days afterwards he was dismissed.

He took his notice lightly enough, confident that as master of his trade he could soon secure work again.

It was not to be. Every shop and yard in London was closed to him. Word had gone round that he was an agitator.

Try as he did, he could not break through the barrier that had been raised against him. Wherever he applied, whether in Rotherhithe, Battersea, Hackney, or Clerkenwell, he was known as the young fellow who would not work with shoddy material and talked other men into the same view.

The experience was the same at every place of call.

"What's your name?"

"Crooks."

"Of Poplar?"

"That's me."

"We don't want anyone."

From several of these places he heard afterwards that the instant he was gone other men were taken on.

Since London was a closed door to him, he turned his back upon it, and set out tramping the country in search of work. With a fully-paid-up trade union card, he knew he could count on an occasional half-crown to help him on the way at those towns where his society had branches.

His home had to be broken up. His wife with their child went to her mother's, there to await for weary weeks the result of her husband's first quest into the country.

The only piece of good news came from Liverpool. Not until he reached that city did he get a job. He tramped into Liverpool from Burton-on-Trent. Never in his life, either before or since, did a silver coin mean so much to him as the half-crown given by a member of his own trade to help him on the road as he set out from Burton for Liverpool.

Twenty-nine years later Crooks was speaking at a meeting of co-operators in Burton when he recognised his former benefactor on the platform. He told the audience of his last visit to their town, remarking how on that occasion no one but this man offered him hospitality, whereas now, if he lived to be a hundred and fifty years of age, he would not be able to accept all the invitations he had received from friends and would-be friends to spend week-ends with them. His regret was, he told the meeting, that those good people did not begin to ask him earlier and that they did not think of asking other poor men in a similar plight to his when he first entered Burton.

By the time he dragged himself into Liverpool he was without a sole to his boots. The journey was completed on the uppers of his boots, with the aid of string, a device he had learnt from friendly tramps on the road. Having got what looked like a promising job, he invited his wife to join him[Pg 46] with their child, enclosing the fare from his first week's wages.

This work in Liverpool had not been obtained without much weary searching. A good friend to the young fellow in his distress was the Y.M.C.A. in that city. Nearly thirty years later he addressed a crowded public meeting in the large hall of the Liverpool Y.M.C.A. He had an enthusiastic welcome when he rose to speak.

I am very grateful to you for your kind welcome of me to-night. This hall has carried my memory back to 1876 when I first visited Liverpool. I was then looking for work, knowing what it was to want a meal many a day. I don't know what I should have done without the many kindnesses I met with from Liverpool people, and from none more hearty and truly helpful than I received here in this building.

But Liverpool is associated with one of the saddest memories in his life. This is how he refers to it:—

"My wife joined me, bringing our little girl, a bonny child of whom we were immensely proud. The little one pined from the day it reached Liverpool and died within a month. I thought my wife would have followed the child to the grave within a day or two. I never saw her so much affected in all my life. She pleaded to be taken away from that place. 'Anywhere,' she said, 'only let's get away.' So we buried our little girl in Liverpool one rainy Saturday afternoon, and came back to London to seek work the same night."

It was the most miserable railway journey of his life. If anything, the misery was increased[Pg 47] when as the dull dawn crept over London he and his wife stepped out of the train and walked the seven miles of silent streets between Euston and Poplar.

No better fortune awaited them in London. The young husband sought work with no success. News reached him that his trade was thriving again in Liverpool, so he set out to tramp there a second time.

"It is a weird experience, this, of wandering through England in search of a job," he says. "You keep your heart up so long as you have something in your stomach, but when hunger steals upon you, then you despair. Footsore and listless at the same time, you simply lose all interest in the future.