Transcriber's Note:

Obvious typographical errors have been corrected. Inconsistent spelling and hyphenation in the original document have been preserved.

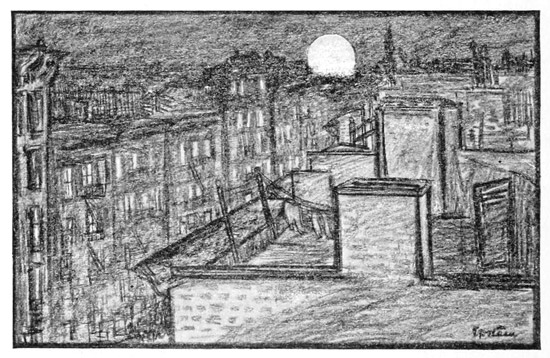

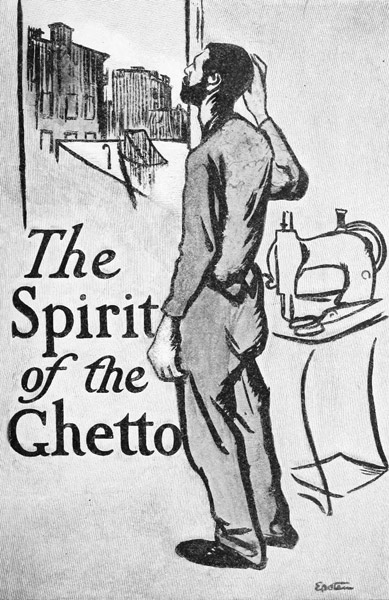

THE SPIRIT of

THE GHETTO

STUDIES OF THE JEWISH

QUARTER IN NEW YORK

By

HUTCHINS HAPGOOD

With Drawings from Life by

JACOB EPSTEIN

NEW YORK AND LONDON

FUNK & WAGNALLS COMPANY

NINETEEN HUNDRED AND TWO

Copyright, 1902

by

Funk & Wagnalls

Company

Printed in the

United States of America

Published

November, 1902

A number of these chapters have appeared as

separate articles in "The Atlantic Monthly,"

"The Critic," "The Bookman," "The World's

Work," "The Boston Transcript," and "The

Evening Post" and "The Commercial Advertiser"

of New York. To the editors of

these publications thanks for permission to

republish are gratefully tendered by

The Author.

The Jewish quarter of New York is generally supposed to be a place of poverty, dirt, ignorance and immorality—the seat of the sweat-shop, the tenement house, where "red-lights" sparkle at night, where the people are queer and repulsive. Well-to-do persons visit the "Ghetto" merely from motives of curiosity or philanthropy; writers treat of it "sociologically," as of a place in crying need of improvement.

That the Ghetto has an unpleasant aspect is

as true as it is trite. But the unpleasant aspect

is not the subject of the following sketches. I

was led to spend much time in certain poor resorts

of Yiddish New York not through motives

either philanthropic or sociological, but simply

by virtue of the charm I felt in men and things

there. East Canal Street and the Bowery have

interested me more than Broadway and Fifth

Avenue. Why, the reader may learn from the

present volume—which is an attempt made by a

"Gentile" to report sympathetically on the

character, lives and pursuits of certain east-side

Jews with whom he has been in relations of

considerable intimacy.

The Author.

| Chapter I | ||

| Page | ||

| The Old and the New | 9 | |

| The Old Man | ||

| The Boy | ||

| The "Intellectuals" | ||

| Chapter II | ||

| Prophets without Honor | 44 | |

| Submerged Scholars: A Man of God—A Bitter Prophet—A Calm Student | ||

| The Poor Rabbis: Their Grievances—The "Genuine" Article—A Down-Town Specimen—The Neglected Type | ||

| Chapter III | ||

| The Old and New Woman | 71 | |

| The Orthodox Jewess: Devotion and Customs | ||

| The Modern Type: Passionate Socialists—Confirmed Blue-Stockings | ||

| Place of Woman in Ghetto Literature | ||

| Chapter IV | ||

| Four Poets | 90 | |

| A Wedding Bard | ||

| A Champion of Race | ||

| A Singer of Labor | ||

| A Dreamer of Brotherhood | ||

| Chapter V | ||

| The Stage | 113 | |

| Theatres, Actors, and Audience | ||

| Realism, the Spirit of the Ghetto Theatre | ||

| The History of the Yiddish Stage 8 | ||

| Chapter VI | ||

| The Newspapers | 177 | |

| The Conservative Journals | ||

| The Socialist Papers | ||

| The Anarchist Papers | ||

| Some Picturesque Contributors | ||

| Chapter VII | ||

| The Sketch-Writers | 199 | |

| Some Realists | ||

| A Cultivated Literary Man | ||

| American Life Through Russian Eyes | ||

| A Satirist of Tenement Society | ||

| Chapter VIII | ||

| A Novelist | 230 | |

| Chapter IX | ||

| The Young Art and its Exponents | 254 | |

| Chapter X | ||

| Odd Characters | 272 | |

| An Out-of-date Story-Writer | ||

| A Cynical Inventor | ||

| An Impassioned Critic | ||

| The Poet of Zionism | ||

| An Intellectual Debauchee | ||

No part of New York has a more intense and varied life than the colony of Russian and Galician Jews who live on the east side and who form the largest Jewish city in the world. The old and the new come here into close contact and throw each other into high relief. The traditions and customs of the orthodox Jew are maintained almost in their purity, and opposed to these are forms and ideas of modern life of the most extreme kind. The Jews are at once tenacious of their character and susceptible to their Gentile environment, when 10 that environment is of a high order of civilization. Accordingly, in enlightened America they undergo rapid transformation tho retaining much that is distinctive; while in Russia, surrounded by an ignorant peasantry, they remain by themselves, do not so commonly learn the Gentile language, and prefer their own forms of culture. There their life centres about religion. Prayer and the study of "the Law" constitute practically the whole life of the religious Jew.

When the Jew comes to America he remains, if he is old, essentially the same as he was in Russia. His deeply rooted habits and the "worry of daily bread" make him but little sensitive to the conditions of his new home. His imagination lives in the old country and he gets his consolation in the old religion. He picks up only about a hundred English words and phrases, which he pronounces in his own way. Some of his most common acquisitions are "vinda" (window), "zieling" (ceiling), "never mind," "alle right," "that'll do," "politzman" (policeman); "ein schön kind, ein reg'lar pitze!" (a pretty child, a regular picture). Of this modest vocabulary he is very proud, for it takes him out of the category of the "greenhorn," a term of contempt to which the satirical Jew is very sensitive. The man who has been only three weeks in this 11 country hates few things so much as to be called a "greenhorn." Under this fear he learns the small vocabulary to which in many years he adds very little. His dress receives rather greater modification than his language. In the old country he never appeared in a short coat; that would be enough to stamp him as a "freethinker." But when he comes to New York and his coat is worn out he is unable to find any garment long enough. The best he can do is to buy a "cut-away" or a "Prince Albert," which he often calls a "Prince Isaac." As soon as he imbibes the fear of being called a "greenhorn" he assumes the "Prince Isaac" with less regret. Many of the old women, without diminution of piety, discard their wigs, which are strictly required by the orthodox in Russia, and go even to the synagogue with nothing on their heads but their natural locks.

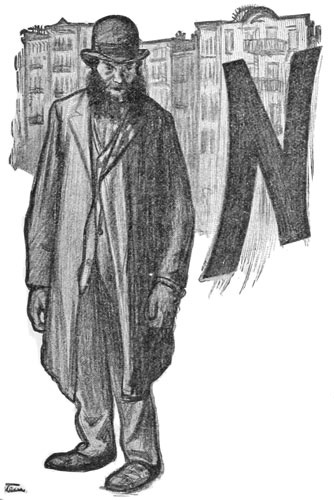

The old Jew on arriving in New York usually becomes a sweat-shop tailor or push-cart peddler. There are few more pathetic sights than an old man with a long beard, a little black cap on his head and a venerable face—a man who had been perhaps a Hebraic or Talmudic scholar in the old country, carrying or pressing piles of coats in the melancholy sweat-shop; or standing for sixteen hours a day by his push-cart in one 12 of the dozen crowded streets of the Ghetto, where the great markets are, selling among many other things apples, garden stuff, fish and second-hand shirts.

This man also becomes a member of one of the many hundred lodges which exist on the east side. These societies curiously express at once the old Jewish customs and the conditions of the new world. They are mutual insurance companies formed to support sick members. When a brother is ill the President appoints a committee to visit him. Mutual insurance societies and committees are American enough, and visiting the sick is prescribed by the Talmud. This is a striking instance of the adaptation of the "old" to the "new." The committee not only condoles with the decrepit member, but gives him a sum of money.

Another way in which the life of the old Jew is affected by his 13 New York environment, perhaps the most important way as far as intellectual and educative influences are concerned, is through the Yiddish newspapers, which exist nowhere except in this country. They keep him in touch with the world's happenings in a way quite impossible in Europe. At the Yiddish theatres, too, he sees American customs portrayed, although grotesquely, and the old orthodox things often satirized to a degree; the "greenhorn" laughed to scorn and the rabbi held up to derision.

Nevertheless these influences leave the man pretty much as he was when he landed here. He remains the patriarchal Jew devoted to the law and to prayer. He never does anything that is not prescribed, and worships most of the time that he is not at work. He has only one point of view, that of the Talmud; and his aesthetic as well as his religious criteria are determined by it. "This is a beautiful letter you have written me"; wrote an old man to his son, "it smells of Isaiah." He makes of his house a synagogue, and prays three times a day; when he prays his head is covered, he wears the black and white praying-shawl, and the cubes of the phylactery are attached to his forehead and left arm. To the cubes are fastened two straps of goat-skin, black and white; those on the forehead hang down, and those attached 14 to the other cube are wound seven times about the left arm. Inside each cube is a white parchment on which is written the Hebrew word for God, which must never be spoken by a Jew. The strength of this prohibition is so great that even the Jews who have lost their faith are unwilling to pronounce the word.

At the Synagogue

Besides the home prayers there are daily visits to the synagogue, fasts and holidays to observe. When there is a death in the family he does not go to the synagogue, but prays at home. The ten men necessary for the funeral ceremony, who are partly supplied by the Bereavement Committee of the Lodge, sit seven days in their stocking-feet on foot-stools and read Job all the time. On the Day of Atonement the old Jew stands much of the day in the synagogue, wrapped in a white gown, and seems to be one of a meeting of the dead. The Day of Rejoicing of the Law and the Day of Purim are the only two days in the year when an orthodox Jew may be intoxicated. It is virtuous on these days to drink too much, but the sobriety of the Jew is so great that he sometimes cheats his friends and himself by shamming drunkenness. On the first and second evenings of the Passover the father dresses in a big white robe, the family gather about him, and the youngest male child asks the father the reason 15 why the day is celebrated; whereupon the old man relates the whole history, and they all talk it over and eat, and drink wine, but in no vessel which has been used before during the year, for everything must be fresh and clean on this day. The night before the Passover the remaining leavened bread is gathered together, just enough for breakfast, for only unleavened bread can be eaten during the next eight days. The head of the family goes around with a candle, gathers up the crumbs with a quill or a spoon and burns them. A custom which has 16 almost died out in New York is for the congregation to go out of the synagogue on the night of the full moon, and chant a prayer in the moonlight.

In addition to daily religious observances in his home and in the synagogues, to fasts and holidays, the orthodox Jew must give much thought to his diet. One great law is the line drawn between milk things and meat things. The Bible forbids boiling a kid in the milk of its mother. Consequently the hair-splitting Talmud prescribes the most far-fetched discrimination. For instance, a plate in which meat is cooked is called a meat vessel, the knife with which it is cut is called a meat knife, the spoon with which one eats the soup that was cooked in a meat pot, though there is no meat in the soup, is a meat spoon, and to use that spoon for a milk thing is prohibited. All these regulations, of course, seem privileges to the orthodox Jew. The sweat-shops are full of religious fanatics, who, in addition to their ceremonies at home, form Talmudic clubs and gather in tenement-house rooms, which they convert into synagogues.

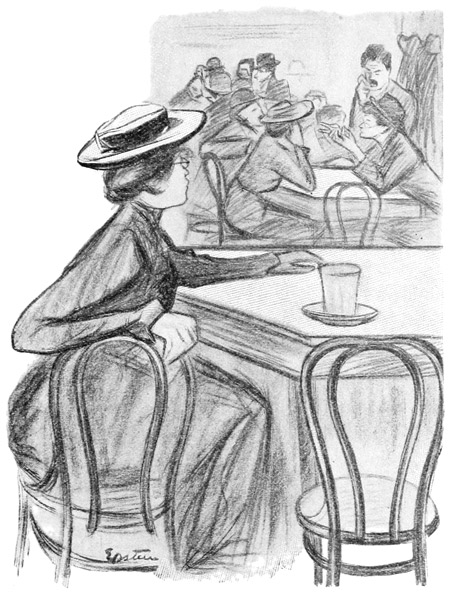

In several of the cafés of the quarter these old fellows gather. With their long beards, long black coats, and serious demeanor, they sit about little tables and drink honey-cider, eat lima 17 beans and jealously exclude from their society the socialists and freethinkers of the colony who, not unwillingly, have cafés of their own. They all look poor, and many of them are, in fact, peddlers, shop-keepers or tailors; but some, not distinguishable in appearance from the proletarians, have "made their pile." Some are Hebrew scholars, some of the older class of Yiddish journalists. There are no young people there, for the young bring irreverence and the American spirit, and these cafés are strictly orthodox.

In spite, therefore, of his American environment, the old Jew of the Ghetto remains patriarchal, highly trained and educated in a narrow sectarian direction, but entirely ignorant of modern culture; medieval, in effect, submerged in old tradition and outworn forms.

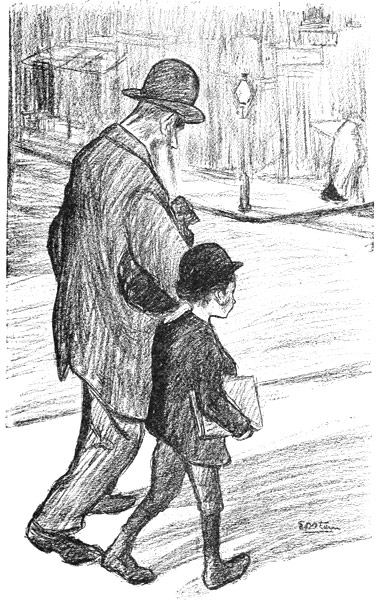

The shrewd-faced boy with the melancholy eyes that one sees everywhere in the streets of New York's Ghetto, occupies a peculiar position in our society. If we could penetrate into his soul, we should see a mixture of almost unprecedented hope and excitement on the one hand, and of doubt, confusion, and self-distrust on the other hand. Led in many contrary directions, the fact that he does not grow to be an intellectual anarchist is due to his serious racial characteristics.

Three groups of influences are at work on him—the orthodox Jewish, the American, and the Socialist; and he experiences them in this order. He has either been born in America of Russian, Austrian, or Roumanian Jewish parents, or has immigrated with them when a very young child. The first of the three forces at work on his character is religious and moral; the second is practical, diversified, non-religious; and the third is reactionary from the other two and hostile to them.

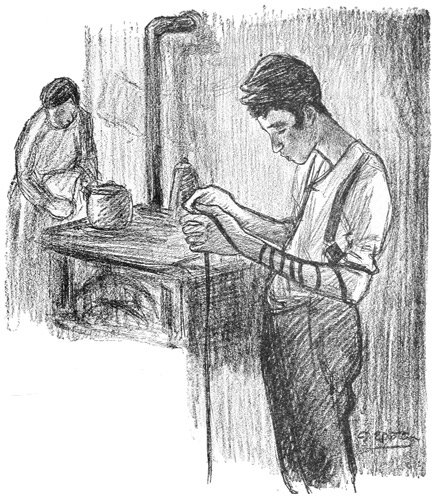

THE MORNING PRAYER

Whether born in this country or in Russia, the son of orthodox parents passes his earliest years in a family atmosphere where the whole duty of man is to observe the religious law. He learns 19 to say his prayers every morning and evening, either at home or at the synagogue. At the age of five, he is taken to the Hebrew private school, the "chaider," where, in Russia, he spends most of his time from early morning till late at night. The ceremony accompanying his first appearance in "chaider" is significant of his whole orthodox life. Wrapped in a "talith," or praying shawl, he is carried by his father to the school and received there by the "melamed," or teacher, who holds out before him the Hebrew alphabet on a large chart. Before beginning to learn the first letter of the alphabet, he is given a taste of honey, and when 20 he declares it to be sweet, he is told that the study of the Holy Law, upon which he is about to enter, is sweeter than honey. Shortly afterwards a coin falls from the ceiling, and the boy is told that an angel dropped it from heaven as a reward for learning the first lesson.

In the Russian "chaider" the boy proceeds with a further study of the alphabet, then of the prayer-book, the Pentateuch, other portions of the Bible, and finally begins with the complicated Talmud. Confirmed at thirteen years of age, he enters the Hebrew academy and continues the study of the Talmud, to which, if he is successful, he will devote himself all his life. For his parents desire him to be a rabbi, or Talmudical scholar, and to give himself entirely to a learned interpretation of the sweet law.

GOING TO THE SYNAGOGUE

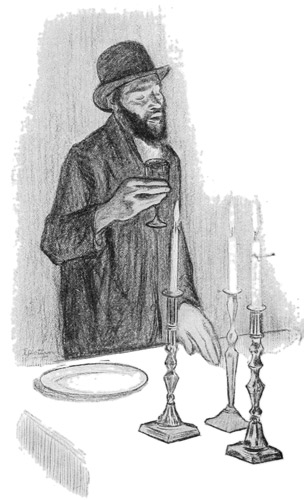

The boy's life at home, in Russia, conforms with the religious education received at the "chaider." On Friday afternoon, when the Sabbath begins, and on Saturday morning, when it continues, he is free from school, and on Friday does errands for his mother or helps in the preparation for the Sabbath. In the afternoon he commonly bathes, dresses freshly in Sabbath raiment, and goes to "chaider" in the evening. Returning from school, he finds his mother and sisters dressed in their best, ready to "greet the 22 Sabbath." The lights are glowing in the candlesticks, the father enters with "Good Shabbas" on his lips, and is received by the grandparents, who occupy the seats of honor. They bless him and the children in turn. The father then chants the hymn of praise and salutation; a cup of wine or cider is passed from one to the other; every one washes his hands; all arrange themselves at table in the order of age, the youngest sitting at the father's right hand. After the meal they sing a song dedicated to the Sabbath, and say grace. The same ceremony is repeated on Saturday morning, and afterwards the children are examined in what they have learned of the Holy Law during the week. The numerous religious holidays are observed in the same way, with special ceremonies of their own in addition. The important thing to notice is, that the boy's whole training and education bear directly on ethics and religion, in the study of which he is encouraged to spend his whole life.

In a simple Jewish community in Russia, where the "chaider" is the only school, where the government is hostile, and the Jews are therefore thrown back upon their own customs, the boy loves his religion, he loves and honors his parents, his highest ambition is to be a great scholar—to know the Bible in all its glorious 23 meaning, to know the Talmudical comments upon it, and to serve God. Above every one else he respects the aged, the Hebrew scholar, the rabbi, the teacher. Piety and wisdom count more than riches, talent and power. The "law" outweighs all else in value. Abraham and Moses, David and Solomon, the prophet Elijah, are the kind of great men to whom his imagination soars.

But in America, even before he begins to go to our public schools, the little Jewish boy finds himself in contact with a new world which stands in violent contrast with the orthodox environment of his first few years. Insensibly—at the beginning—from his playmates in the streets, from his older brother or sister, he picks up a little English, a little American slang, hears older boys boast of prize-fighter Bernstein, and learns vaguely to feel that there is a strange and fascinating life on the street. At this tender age he may even begin to black boots, gamble in pennies, and be filled with a "wild surmise" about American dollars.

With his entrance into the public school the little fellow runs plump against a system of education and a set of influences which are at total variance with those traditional to his race and with his home life. The religious element is entirely lacking. The educational system of the 24 public schools is heterogeneous and worldly. The boy becomes acquainted in the school reader with fragments of writings on all subjects, with a little mathematics, a little history. His instruction, in the interests of a liberal non-sectarianism, is entirely secular. English becomes his most familiar language. He achieves a growing comprehension and sympathy with the independent, free, rather sceptical spirit of the American boy; he rapidly imbibes ideas about social equality and contempt for authority, and tends to prefer Sherlock Holmes to Abraham as a hero.

The orthodox Jewish influences, still at work upon him, are rapidly weakened. He grows to look upon the ceremonial life at home as rather ridiculous. His old parents, who speak no English, he regards as "greenhorns." English becomes his habitual tongue, even at home, and Yiddish he begins to forget. He still goes to "chaider," but under conditions exceedingly different from those obtaining in Russia, where there are no public schools, and where the boy is consequently shut up within the confines of Hebraic education. In America, the "chaider" assumes a position entirely subordinate. Compelled by law to go to the American public school, the boy can attend "chaider" only before 25 the public school opens in the morning or after it closes in the afternoon. At such times the Hebrew teacher, who dresses in a long black coat, outlandish tall hat, and commonly speaks no English, visits the boy at home, or the boy goes to a neighboring "chaider."

Contempt for the "chaider's" teaching comes the more easily because the boy rarely understands his Hebrew lessons to the full. His real language is English, the teacher's is commonly the Yiddish jargon, and the language to be learned is Hebrew. The problem before him is consequently the strangely difficult one of learning Hebrew, a tongue unknown to him, through a translation into Yiddish, a language of growing unfamiliarity, which, on account of its poor dialectic character, is an inadequate vehicle of thought.

The orthodox parents begin to see that the boy, in order to "get along" in the New World, must receive a Gentile training. Instead of hoping to make a rabbi of him, they reluctantly consent to his becoming an American business man, or, still better, an American doctor or lawyer. The Hebrew teacher, less convinced of the usefulness and importance of his work, is in this country more simply commercial and less disinterested than abroad; a man generally, 26 too, of less scholarship as well as of less devotion.

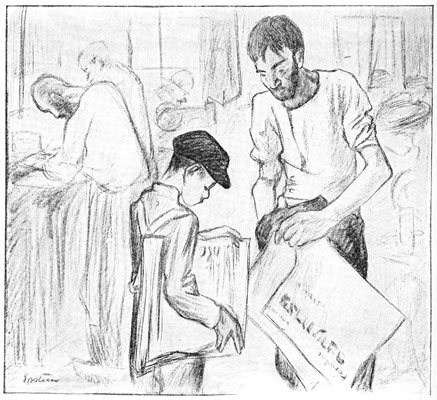

THE "CHAIDER"

The growing sense of superiority on the part of the boy to the Hebraic part of his environment extends itself soon to the home. He learns to feel that his parents, too, are "greenhorns." In the struggle between the two sets of influences that of the home becomes less and less effective. He runs away from the supper table to join his gang on the Bowery, where he is quick to pick up the very latest slang; where his talent for caricature is developed often at the expense of his parents, his race, and all "foreigners"; for 27 he is an American, he is "the people," and like his glorious countrymen in general, he is quick to ridicule the stranger. He laughs at the foreign Jew with as much heartiness as at the "dago"; for he feels that he himself is almost as remote from the one as from the other.

"Why don't you say your evening prayer, my son?" asks his mother in Yiddish.

"Ah, what yer givin' us!" replies, in English, the little American-Israelite as he makes a bee-line for the street.

The boys not only talk together of picnics, of the crimes of which they read in the English newspapers, of prize-fights, of budding business propositions, but they gradually quit going to synagogue, give up "chaider" promptly when they are thirteen years old, avoid the Yiddish theatres, seek the up-town places of amusement, dress in the latest American fashion, and have a keen eye for the right thing in neckties. They even refuse sometimes to be present at supper on Friday evenings. Then, indeed, the sway of the old people is broken.

"Amerikane Kinder, Amerikane Kinder!" wails the old father, shaking his head. The trend of things is indeed too strong for the old man of the eternal Talmud and ceremony.

An important circumstance in helping to determine 28 the boy's attitude toward his father is the tendency to reverse the ordinary and normal educational and economical relations existing between father and son. In Russia the father gives the son an education and supports him until his marriage, and often afterward, until the young man is able to take care of his wife and children. The father is, therefore, the head of the house in reality. But in the New World the boy contributes very early to the family's support. The father is in this country less able to make an economic place for himself than is the son. The little fellow sells papers, blacks boots, and becomes a street merchant on a small scale. As he speaks English, and his parents do not, he is commonly the interpreter in business transactions, and tends generally to take things into his own hands. There is a tendency, therefore, for the father to respect the son.

There is many a huge building on Broadway which is the external sign (with the Hebrew name of the tenant emblazoned on some extended surface) of the energy and independence of some ignorant little Russian Jew, the son of a push-cart peddler or sweat-shop worker, who began his business career on the sidewalks, selling newspapers, blacking boots, dealing in candles, shoe-strings, fruit, etc., and continued it by peddling 29 in New Jersey or on Long Island until he could open a small basement store on Hester Street, then a more extensive establishment on Canal Street—ending perhaps as a rich merchant on Broadway. The little fellow who starts out on this laborious climb is a model of industry and temperance. His only recreation, outside of business, which for him is a pleasure in itself, is to indulge in some simple pastime which generally is calculated to teach him something. On Friday or Saturday afternoon he is likely, for instance, to take a long walk to the park, where he is seen keenly inspecting the animals and perhaps boasting of his knowledge about them. He is an acquisitive little fellow, and seldom enjoys himself unless he feels that he is adding to his figurative or literal stock.

The cloak and umbrella business in New York is rapidly becoming monopolized by the Jews who began in the Ghetto; and they are also very large clothing merchants. Higher, however, than a considerable merchant in the world of business, the little Ghetto boy, born in a patriarchal Jewish home, has not yet attained. The Jews who as bankers, brokers, and speculators on Wall Street control millions never have been Ghetto Jews. They came from Germany, where conditions are very different from those 30 in Russia, Galicia, and Roumania, and where, through the comparatively liberal education of a secular character which they were able to obtain, they were already beginning to have a national life outside of the Jewish traditions. Then, too, these Jews who are now prominent in Wall Street have been in this country much longer than their Russian brethren. They are frequently the sons of Germans who in the last generation attained commercial rank. If they were born abroad, they came many years before the Russian immigration began and before the American Ghetto existed, and have consequently become thoroughly identified with American life. Some of them began, indeed, as peddlers on a very small scale; travelled, as was more the habit with them then than now, all over the country; and rose by small degrees to the position of great financial operators. But they became so only by growing to feel very intimately the spirit of American enterprise which enables a man to carry on the boldest operation in a calm spirit.

To this boldness the son of the orthodox parents of our Ghetto has not yet attained. Coming from the cramped "quarter," with still a tinge of the patriarchal Jew in his blood, not yet thoroughly at home in the atmosphere of the 31 American "plunger," he is a little hesitant, though very keen, in business affairs. The conservatism instilled in him by the pious old "greenhorn," his father, is a limitation to his American "nerve." He likes to deal in ponderable goods, to be able to touch and handle his wares, to have them before his eyes. In the next generation, when in business matters also he will be an instinctive American, he will become as big a financial speculator as any of them, but at present he is pretty well content with his growing business on Broadway and his fine residence up-town.

FRIDAY NIGHT PRAYER

Altho as compared with the American or German-Jew financier who does not turn a hair at the gain or loss of a million, and who in personal manner maintains a phlegmatic, Napoleonic calm which is almost the most impressive 32 thing in the world to an ordinary man, the young fellow of the Ghetto seems a hesitant little "dickerer," yet, of course, he is a rising business man, and, as compared to the world from which he has emerged, a very tremendous entity indeed. It is not strange, therefore, that this progressive merchant, while yet a child, acquires a self-sufficiency, an independence, and sometimes an arrogance which not unnaturally, at least in form, is extended even toward his parents.

If this boy were able entirely to forget his origin, to cast off the ethical and religious influences which are his birthright, there would be no serious struggle in his soul, and he would not represent a peculiar element in our society. He would be like any other practical, ambitious, rather worldly American boy. The struggle is strong because the boy's nature, at once religious and susceptible, is strongly appealed to by both the old and new. At the same time that he is keenly sensitive to the charm of his American environment, with its practical and national opportunities, he has still a deep love for his race and the old things. He is aware, and rather ashamed, of the limitations of his parents. He feels that the trend and weight of things are against them, that they are in a minority; but yet in a real way the old people remain his conscience, 33 the visible representatives of a moral and religious tradition by which the boy may regulate his inner life.

The attitude of such a boy toward his father and mother is sympathetically described by Dr. Blaustein, principal of the Educational Alliance:

"Not knowing that I speak Yiddish, the boy often acts as interpreter between me and his exclusively Yiddish-speaking father and mother. He always shows a great fear that I should be ashamed of his parents and tries to show them in the best light. When he translates, he expresses, in his manner, great affection and tenderness toward these people whom he feels he is protecting; he not merely turns their Yiddish into good English, but modifies the substance of what they say in order to make them appear presentable, less outlandish and queer. He also manifests cleverness in translating for his parents what I say in English. When he finds that I can speak Yiddish and therefore can converse heart to heart with the old people, he is delighted. His face beams, and he expresses in every way that deep pleasure which a person takes in the satisfaction of honored protégés."

The third considerable influence in the life of the Ghetto boy is that of the socialists. I am inclined to think that this is the least important and the least desirable of the three in its effect on his character. 34

Socialism as it is agitated in the Jewish quarter consists in a wholesale rejection, often founded on a misunderstanding, of both American and Hebraic ideals. The socialists harp monotonously on the relations between capital and labor, the injustice of classes, and assume literature to comprise one school alone, the Russian, at the bottom of which there is a strongly anarchistic and reactionary impulse. The son of a socialist laborer lives in a home where the main doctrines are two: that the old religion is rubbish and that American institutions were invented to exploit the workingman. The natural effects on such a boy are two: a tendency to look with distrust at the genuinely American life about him, and to reject the old implicit piety.

The ideal situation for this young Jew would be that where he could become an integral part of American life without losing the seriousness of nature developed by Hebraic tradition and education. At present he feels a conflict between these two influences: his youthful ardor and ambition lead him to prefer the progressive, if chaotic and uncentred, American life; but his conscience does not allow him entire peace in a situation which involves a chasm between him and his parents and their ideals. If he could find along the line of his more exciting interests—the 35 American—something that would fill the deeper need of his nature, his problem would receive a happy solution.

At present, however, the powers that make for the desired synthesis of the old and the new are fragmentary and unimportant. They consist largely in more or less charitable institutions such as the University Settlement, the Educational Alliance, and those free Hebrew schools which are carried on with definite reference to the boy as an American citizen. The latter differ from the "chaiders" in several respects. The important difference is that these schools are better organized, have better teachers, and have as a conscious end the supplementing of the boy's common school education. The attempt is to add to the boy's secular training an ethical and religious training through the intelligent study of the Bible. It is thought that an acquaintance with the old literature of the Jews is calculated to deepen and spiritualize the boy's nature.

The Educational Alliance is a still better organized and more intelligent institution, having much more the same purpose in view as the best Hebrew schools. Its avowed purpose is to combine the American and Hebrew elements, reconcile fathers and sons by making the former more 36 American and the latter more Hebraic, and in that way improve the home life of the quarter. With the character of the University Settlement nearly everybody is familiar. It falls in line with Anglo-Saxon charitable institutions, forms classes, improves the condition of the poor, and acts as an ethical agent. But, tho such institutions as the above may do a great deal of good, they are yet too fragmentary and external, are too little a vital growth from the conditions, to supply the demand for a serious life which at the same time shall be American.

But the Ghetto boy is making use of his heterogeneous opportunities with the greatest energy and ambition. The public schools are filled with little Jews; the night schools of the east side are practically used by no other race. City College, New York University, and Columbia University are graduating Russian Jews in numbers rapidly increasing. Many lawyers, indeed, children of patriarchal Jews, have very large practices already, and some of them belong to solid firms on Wall Street; although as to business and financial matters they have not yet attained to the most spectacular height. Then there are innumerable boys' debating clubs, ethical clubs, and literary clubs in the east side; altogether there is an excitement in ideas and an enthusiastic 37 energy for acquiring knowledge which has interesting analogy to the hopefulness and acquisitive desire of the early Renaissance. It is a mistake to think that the young Hebrew turns naturally to trade. He turns his energy to whatever offers the best opportunities for broader life and success. Other things besides business are open to him in this country, and he is improving his chance for the higher education as devotedly as he has improved his opportunities for success in business.

It is easy to see that the Ghetto boy's growing Americanism will be easily triumphant at once over the old traditions and the new socialism. Whether or not he will be able to retain his moral earnestness and native idealism will depend not so much upon him as upon the development of American life as a whole. What we need at the present time more than anything else is a spiritual unity such as, perhaps, will only be the distant result of our present special activities. We need something similar to the spirit underlying the national and religious unity of the orthodox Jewish culture.

Altho the young men of the Ghetto who represent at once the most intelligent and the most progressively American are, for the most part, floundering about without being able to 38 find the social growths upon which they can rest as true Americans while retaining their spiritual and religious earnestness, there are yet a small number of them who have already attained a synthesis not lacking in the ideal. I know a young artist, a boy born in the Ghetto, who began his conscious American life with contempt for the old things, but who with growing culture has learned to perceive the beauty of the traditions and faith of his race. He puts into his paintings of the types of Hester Street an imaginative, almost religious, idealism, and his artistic sympathy seems to extend particularly to the old people. He, for one, has become reconciled to the spirit of his father without ceasing to be an American. And he is not alone. There are other young Jews, of American university education, of strong ethical and spiritual character, who are devoting themselves to the work of forming, among the boys of the Ghetto, an ideal at once American and consistent with the spirit at the heart of the Hebraic tradition.

Between the old people, with their religion, their traditions, the life pointing to the past, and the boy with his young life eagerly absorbent of the new tendencies, is a third class which may 39 be called the "Intellectuals" of the Ghetto. This is the most picturesque and interesting, altho not the most permanently significant, of all. The members of this class are interesting for what they are rather than for what they have been or for what they may become. They are the anarchists, the socialists, the editors, the writers; some of the scholars, poets, playwrights and actors of the quarter. They are the "enlightened" ones who are at once neither orthodox Jews nor Americans. Coming from Russia, they are reactionary in their political opinions, and in matters of taste and literary ideals are Europeans rather than Americans. When they die they will leave nothing behind them; but while they live they include the most educated, forcible, and talented personalities of the quarter. Most of them are socialists, and, as I pointed out in the last section, socialism is not a permanently nutritive element in the life of the Ghetto, for as yet the Ghetto has not learned to know the conditions necessary to American life, and can not, therefore, effectively react against them.

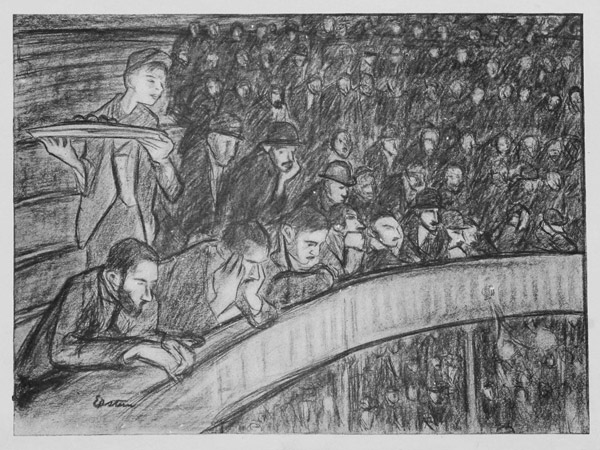

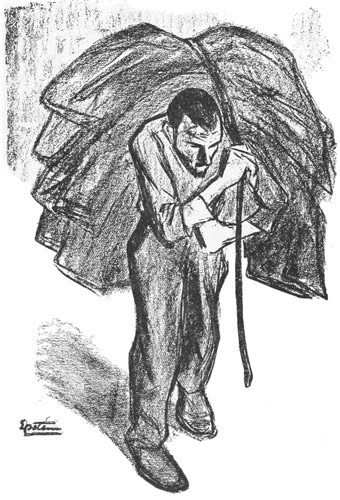

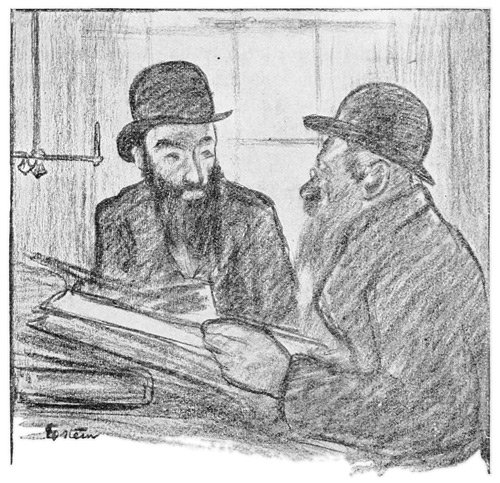

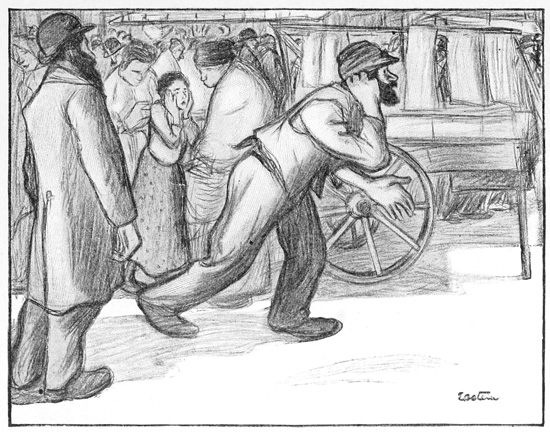

It is this class which contains, however, the many men of "ideas" who bring about in certain circles a veritable intellectual fermentation; and are therefore most interesting from what might be called a literary point of view, as well as of 40 great importance in the education of the people. Gifted Russian Jews hold forth passionately to crowds of working men; devoted writers exploit in the Yiddish newspapers the principles of their creed and take violent part in the labor agitation of the east side; or produce realistic sketches of the life in the quarter, underlying which can be felt the same kind of revolt which is apparent in the analogous literature of Russia. The intellectual excitement in the air causes many "splits" among the socialists. They gather in hostile camps, run rival organs, each prominent man has his "patriots," or faithful adherents who support him right or wrong. Intense personal abuse and the most violent denunciation of opposing principles are the rule. Mellowness, complacency, geniality, and calmness are qualities practically unknown to the intellectual Russian Jews, who, driven from the old country, now possess the first opportunity to express themselves. On the other hand they are free of the stupid Philistinism of content and are not primarily interested in the dollar. Their poets sing pathetically of the sweat-shops, of universal brotherhood, of the abstract rights of man. Their enthusiastic young men gather every evening in cafés of the quarter and become habitually intoxicated with the excitement of 42 ideas. In their restless and feverish eyes shines the intense idealism of the combined Jew and Russian—the moral earnestness of the Hebrew united with the passionate, rebellious mental activity of the modern Muscovite. In these cafés they meet after the theatre or an evening lecture and talk into the morning hours. The ideal, indeed, is alive within them. The defect of their intellectual ideas is that they are not founded on historical knowledge, or on knowledge of the conditions with which they have to cope. In their excitement and extremeness they resemble the spirit of the French "intellectuals" of 1789 rather than that more conservative feeling which has always directed the development of Anglo-Saxon communities.

IN THESE CAFÉS THEY MEET AFTER THE THEATRE OR AN EVENING LECTURE

Among the "intellectuals" may be classed a certain number of poets, dramatists, musicians, and writers, who are neither socialists nor anarchists, constituting what might roughly be called the literary "Bohemia" of the quarter; men who pursue their art for the love of it simply, or who are thereto impelled by the necessity of making a precarious living; men really without ideas in the definite, belligerent sense, often uneducated, but often of considerable native talent. There are also many men of brains who form a large professional class—doctors, lawyers, and dentists—and 43 who yet are too old when they come to America to be thoroughly identified with the life. They are, however, a useful part of the Jewish community, and, like others of the "intellectual" class, are often men of great devotion, who have left comparative honor and comfort in the old country in order to live and work with the persecuted or otherwise less fortunate brethren.

The greater number of the following chapters deal with the men of this "intellectual" class, their personalities, their literary work and the light it throws upon the life of the people in the New York Ghetto. 44

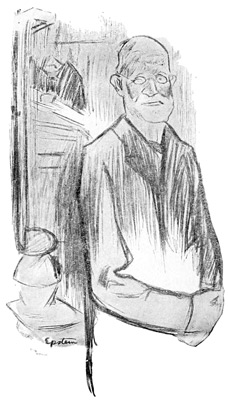

A ragged man, who looks like a peddler or a beggar, picking his way through the crowded misery of Hester Street, or ascending the stairs of one of the dingy tenement-houses full of sweat-shops that line that busy mart of the poor Ghetto Jew, may be a great Hebrew scholar. He may be able to speak and write the ancient tongue with the facility of a modern language—as fluently as the ordinary Jew makes use of the "jargon," the Yiddish of the people; he may be a manifold author with a deep and pious love for the beautiful poetry in his literature; and in character an enthusiast, a dreamer, or a good and reverend old man. But no matter what his attainments and his quality he is unknown and unhonored, for he has pinned his faith to a declining cause, writes his passionate accents in a tongue more and more unknown even to the cultivated Jew; and consequently amid the crowding and material interests of the new world 45 he is submerged—poor in physical estate and his moral capital unrecognized by the people among whom he lives.

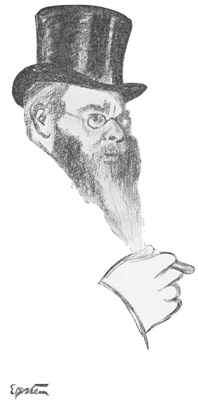

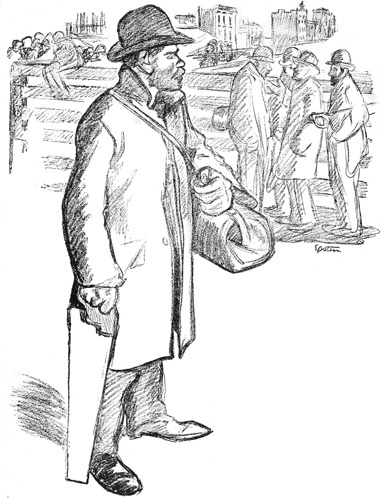

HE IS UNKNOWN AND UNHONORED

Not only unrecognized by the ignorant and the busy and their teachers the rabbis, who in New York are frequently nearly as ignorant as the people, he is also (as his learning is limited largely to the literature of his race) looked down upon by the influential and intellectual element of the Ghetto—an element socialistic, in literary 46 sympathy Russian rather than Hebraic, intolerant of everything not violently modern, wedded to "movements" and scornful of the past. The "maskil," therefore, or "man of wisdom"—the Hebrew scholar—is called "old fogy," or "dilettante," by the up-to-date socialists.

Of such men there are several in the humble corners of the New York Ghetto. One peddles for a living, another has a small printing-office in a basement on Canal Street, a third occasionally tutors in some one of many languages and sells a patent medicine, and a fourth is the principal of the Talmud-Thora, a Hebrew school in the Harlem Ghetto, where he teaches the children to read, write, and pray in the Hebrew language.

Moses Reicherson is the name of the principal. "Man of wisdom" of the purest kind, probably the finest Hebrew grammarian in New York, and one of the finest in the world, his income from his position at the head of the school is $5 a week. He is seventy-three years old, wears a thick gray beard, a little cap on his head, and a long black coat. His wife is old and bent. They are alone in their miserable little apartment on East One Hundred and Sixth Street. Their son died a year or two ago, and to cover the funeral expenses Mr. Reicherson tried in vain to sell his "Encyclopædia Britannica." But, nevertheless, 47 the old scholar, who had been bending over his closely written manuscript, received the visitor with almost cheerful politeness, and told the story of his work and of his ambitions. Of his difficulties and privations he said little, but they shone through his words and in the character of the room in which he lived.

Born in Vilna, sometimes called the Jerusalem of Lithuania or the Athens of modern Judæa because of the number of enlightened Jews who have been born there, many of whom now live in the Russian Jewish quarter of New York, he has retained the faith of his orthodox parents, a faith, however, springing from the pure origin of Judaism rather than holding to the hair-splitting distinctions later embodied in the Talmud. He was a teacher of Hebrew in his native town for many years, where he stayed until he came to New York some years ago to be near his son. His two great intellectual interests, subordinated indeed to the love of the old literature and religion, have been Hebrew grammar and the moral fables of several languages. On the former he has written an important work, and of the latter has translated much of Lessing's and Gellert's work into pure Hebrew. He has also translated into his favorite tongue the Russian fable-writer Krilow; has written fables of his 48 own, and a Hebrew commentary on the Bible in twenty-four volumes. He loves the fables "because they teach the people and are real criticism; they are profound and combine fancy and thought." Many of these are still in manuscript, which is characteristic of much of the work of these scholars, for they have no money, and publishers do not run after Hebrew books. Also unpublished, written in lovingly minute characters, he has a Hebrew prayer-book in many volumes. He has written hundreds of articles for the Hebrew weeklies and monthlies, which are fairly numerous in this country, but which seldom can afford to pay their contributors. At present he writes exclusively for a Hebrew weekly published in Chicago, Regeneration, the object of which is to promote "the knowledge of the ancient Hebrew language and literature, and to regenerate the spirit of the nation." For this he receives no pay, the editor being almost as poor as himself. But he writes willingly for the love of the cause, "for universal good"; for Reicherson, in common with the other neglected scholars, is deeply interested in revivifying what is now among American Jews a dead language. He believes that in this way only can the Jewish people be taught the good and the true.

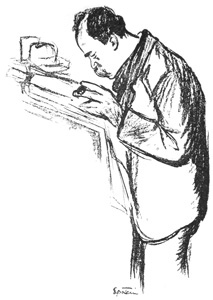

MOSES REICHERSON

"When the national language and literature 49 live," he said, "the nation lives; when dead, so is the nation. The holy tongue in which the Bible was written must not die. If it should, much of the truth of the Bible, many of its spiritual secrets, much of its beautiful poetry, would be lost. I have gone deep into the Bible, that greatest book, all my life, and I know many of its secrets." He beamed with pride as he said these words, and his sense of the beauty of the Hebrew spirit and the Hebrew literature led him to speak wonderingly of Anti-Semitism. This cause seemed to him to be founded on ignorance of the Bible. "If the Anti-Semites would only study the Bible, would go deep into the knowledge of Hebrew and the teaching of Christ, then everything would be sweet and well. If they would spend a little of that money in supporting the Hebrew language and literature and explaining the sacred books which they now use against our race, they would see that they are Anti-Christians rather than Anti-Semites."

The scholar here bethought himself of an old 50 fable he had translated into Hebrew. Cold and Warmth make a wager that the traveller will unwrap his cloak sooner to one than to the other. The fierce wind tries its best, but at every cold blast the traveller only wraps his cloak the closer. But when the sun throws its rays the wayfarer gratefully opens his breast to the warming beams. "Love solves all things," said the old man, "and hate closes up the channels to knowledge and virtue." Believing the Pope to be a good man with a knowledge of the Bible, he wanted to write him about the Anti-Semites, but desisted on the reflection that the Pope was very old and overburdened, and that the letter would probably fall into the hands of the cardinals.

All this was sweetly said, for about him there was nothing of the attitude of complaint. His wife once or twice during the interview touched upon their personal condition, but her husband severely kept his mind on the universal truths, and only when questioned admitted that he would like a little more money, in order to publish his books and to enable him to think with more concentration about the Hebrew language and literature. There was no bitterness in his reference to the neglect of Hebrew scholarship in the Ghetto. His interest was impersonal and detached, 51 and his regret at the decadence of the language seemed noble and disinterested; and, unlike some of the other scholars, the touch of warm humanity was in everything he said. Indeed, he is rather the learned teacher of the people with deep religious and ethical sense than the scholar who cares only for learning. "In the name of God, adieu!" he said, with quiet intensity when the visitor withdrew.

Contrasting sharply in many respects with this beautiful old teacher is the man who peddles from tenement-house to tenement-house in the down-town Ghetto, to support himself and his three young children. S. B. Schwartzberg, unlike most of the "submerged" scholars, is still a young man, only thirty-seven years old, but he is already discouraged, bitter, and discontented. He feels himself the apostle of a lost cause—the regeneration in New York of the old Hebrew language and literature. His great enterprise in life has failed. He has now given it up, and the natural vividness and intensity of his nature get satisfaction in the strenuous abuse of the Jews of the Ghetto.

He was born in Warsaw, Poland, the son of a distinguished rabbi. In common with many Russian and Polish Jews, he early obtained a living knowledge of the Hebrew language, and 52 a great love of the literature, which he knows thoroughly, altho, unlike Reicherson and a scholar who is to be mentioned, Rosenberg, he has not contributed to the literature in a scientific sense. He is slightly bald, with burning black eyes, an enthusiastic and excited manner, and talks with almost painful earnestness.

Three years ago Schwartzberg came to this country with a great idea in his head. "In this free country," he thought to himself, "where there are so many Russian and Polish Jews, it is a pity that our tongue is dying, is falling into decay, and that the literature and traditions that hold our race together are being undermined by materialism and ethical skepticism." He had a little money, and he decided he would establish a journal in the interests of the Hebrew language and literature. No laws would prevent him here from speaking his mind in his beloved tongue. He would bring into vivid being again the national spirit of his people, make them love with the old fervor their ancient traditions and language. It was the race's spirit of humanity and feeling for the ethical beauty, not the special creed of Judaism, for which he and the other scholars care little, that filled him with the enthusiasm of an apostle. In his monthly magazine, the Western Light, he put his best efforts, his best thoughts 53 about ethical truths and literature. The poet Dolitzki contributed in purest Hebrew verse, as did many other Ghetto lights. But it received no support, few bought it, and it lasted only a year. Then he gave it up, bankrupt in money and hope. That was several years ago, and since then he has peddled for a living.

The failure has left in Schwartzberg's soul a passionate hatred of what he calls the materialism of the Jews in America. Only in Europe, he thinks, does the love of the spiritual remain with them. Of the rabbis of the Ghetto he spoke with bitterness. "They," he said, "are the natural teachers of the people. They could do much for the Hebrew literature and language. Why don't they? Because they know no Hebrew and have no culture. In Russia the Jews demand that their rabbis should be learned and spiritual, but here they are ignorant and materialistic." So Mr. Schwartzberg wrote a pamphlet which is now famous in the Ghetto. "I wrote it with my heart's blood," he said, his eyes snapping. "In it I painted the spiritual condition of the Jews in New York in the gloomiest of colors."

"It is terrible," he proceeded vehemently. "Not one Hebrew magazine can exist in this country. They all fail, and yet there are many beautiful Hebrew writers to-day. When Dolitzki 54 was twenty years old in Russia he was looked up to as a great poet. But what do the Jews care about him here? For he writes in Hebrew! Why, Hebrew scholars are regarded by the Jews as tramps, as useless beings. Driven from Russia because we are Jews, we are despised in New York because we are Hebrew scholars! The rabbis, too, despise the learned Hebrew, and they have a fearful influence on the ignorant people. If they can dress well and speak English it is all they want. It is a shame how low-minded these teachers of the people are. I was born of a rabbi, and brought up by him, but in Russia they are for literature and the spirit, while in America it is just the other way."

The discouraged apostle of Hebrew literature now sees no immediate hope for the cause. What seems to him the most beautiful lyric poetry in the world he thinks doomed to the imperfect understanding of generations for whom the language does not live. The only ultimate hope is in the New Jerusalem. Consequently the fiery scholar, altho not a Zionist, thinks well of the movement as tending to bring the Jews again into a nation which shall revive the old tongue and traditions. Mr. Schwartzberg referred to some of the other submerged scholars of the Ghetto. His eyes burned with indignation 55 when he spoke of Moses Reicherson. He could hardly control himself at the thought that the greatest Hebrew grammarian living, "an old man, too, a reverend old man," should be brought to such a pass. In the same strain of outrage he referred to another old man, a scholar who would be as poor as Reicherson and himself were it not for his wife, who is a dressmaker. It is she who keeps him out of the category of "submerged" scholars.

REV. H. ROSENBERG

But the Rev. H. Rosenberg, of whose condition Schwartzberg also bitterly complained, is indeed submerged. He runs a printing-office in a Canal Street basement, where he sits in the damp all day long waiting for an opportunity to publish his magnum opus, a cyclopedia of Biblical literature, containing an historical and geographical description of the persons, places, and objects mentioned in the Bible. All the Ghetto scholars speak of this work with bated breath, as a tremendously learned affair. Only two volumes of it have been published. To give the remainder to the world, Mr. Rosenberg is waiting for his children, who are nearly self-supporting, to contribute their mite. He is a man of sixty-two, with the high, bald forehead of a scholar. For twenty years he was a rabbi in Russia, and has preached in thirteen synagogues. He has 56 been nine years in New York, and, in addition to the great cyclopedia, has written, but not published, a cyclopedia of Talmudical literature. A "History of the Jews," in the Russian language, and a Russian novel, "The Jew of Trient," are among his published works. He is one of the most learned of all of these men who have a living, as well as an exact, knowledge of what is generally regarded as a dead language and literature.

Altho he is waiting to publish the great cyclopedia, he is patient and cold. He has not the sweet enthusiasm of Reicherson, and not the vehement and partisan passion of Schwartzberg. He has the coldness of old age, without its spiritual glow, and scholarship is the only idea that moves him. Against the rabbis he has no complaint to make; with them, he said, he had nothing to do. He thinks that Schwartzberg is extreme 57 and unfair, and that there are good and bad rabbis in New York. He is reserved and undemonstrative, and speaks only in reply. When the rather puzzled visitor asked him if there was anything in which he was interested, he replied, "Yes, in my cyclopedia." The only point at which he betrayed feeling was when he quoted proudly the words of a reviewer of the cyclopedia, who had wondered where Dr. Rosenberg had obtained all his learning. He stated indifferently that the Hebrew language and literature is dead and cannot be revived. "I know," he said, "that Hebrew literature does not pay, but I cannot stop." With no indignation, he remarked that the Jews in New York have no ideals. It was a fact objectively to be deplored, but for which he personally had no emotion, all of that being reserved for his cyclopedia.

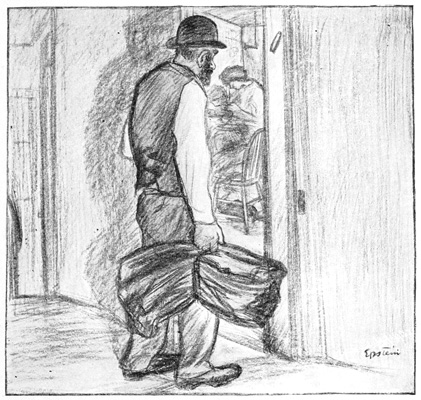

"SUBMERGED SCHOLARS"

These three men are perfect types of the "submerged Hebrew scholar" of the New York Ghetto. Reicherson is the typical religious teacher; Schwartzberg, the enthusiast, who loves the language like a mistress, and Rosenberg, the cool "man of wisdom," who only cares for the perfection of knowledge. Altho there are several others on the east side who approach the type, they fall more or less short of it. Either they are not really scholars in the old tongue, altho 58 reading and even writing it, or through business or otherwise they have raised themselves above the pathetic point. Thus Dr. Benedict Ben-Zion, one of the poorest of all, being reduced to occasional tutoring, and the sale of a patent medicine for a living, is not specifically a scholar. He writes and reads Hebrew, to be sure, but is also a playwright in the "jargon;" has been a 59 Christian missionary to his own people in Egypt, Constantinople, and Rumania, a doctor for many years, a teacher in several languages, one who has turned his hand to everything, and whose heart and mind are not so purely Hebraic as those of the men I have mentioned. He even is seen, more or less, with Ghetto literati who are essentially hostile to what the true Hebrew scholar holds by—a body of Russian Jewish socialists of education, who in their Grand and Canal Street cafés express every night in impassioned language their contempt for whatever is old and historical.

Then, there are J. D. Eisenstein, the youngest and one of the most learned, but perhaps the least "submerged" of them all; Gerson Rosenschweig, a wit, who has collected the epigrams of the Hebrew literature, added many of his own, and written in Hebrew a humorous treatise on America—a very up-to-date Jew, who, like Schwartzberg, tried to run a Hebrew weekly, but when he failed, was not discouraged, and turned to business and politics instead; and Joseph Low Sossnitz, a very learned scholar, of dry and sarcastic tendency, who only recently has risen above the submerged point. Among the latter's most notable published books are a philosophical attack on materialism, 60 a treatise on the sun, and a work on the philosophy of religion.

It is the wrench between the past and the present which has placed these few scholars in their present pathetic condition. Most of them are old, and when they die the "maskil" as a type will have vanished from New York. In the meantime, tho they starve, they must devote themselves to the old language, the old ideas and traditions of culture. Their poet, the austere Dolitzki, famous in Russia at the time of the revival of Hebrew twenty years ago, is the only man in New York who symbolizes in living verse the spirit in which these old men live, the spirit of love for the race as most purely expressed in the Hebrew literature. This disinterested love for the remote, this pathetic passion to keep the dead alive, is what lends to the lives of these "submerged" scholars a nobler quality than what is generally associated with the east side.

The rabbis, as well as the scholars, of the east side of New York have their grievances. They, too, are "submerged," like so much in humanity that is at once intelligent, poor, and out-of-date. As a lot, they are old, reverend men, with long gray beards, long black coats and little black 61 caps on their heads. They are mainly very poor, live in the barest of the tenement houses and pursue a calling which no longer involves much honor or standing. In the old country, in Russia—for most of the poor ones are Russian—the rabbi is a great person. He is made rabbi by the state and is rabbi all his life, and the only rabbi in the town, for all the Jews in every city form one congregation, of which there is but one rabbi and one cantor. He is a man always full of learning and piety, and is respected and supported comfortably by the congregation, a tax being laid on meat, salt, and other foodstuffs for his special benefit.

But in New York it is very different. Here there are hundreds of congregations, one in almost every street, for the Jews come from many different cities and towns in the old country, and the New York representatives of every little place in Russia must have their congregation here. Consequently, the congregations are for the most part small, poor and unimportant. Few can pay the rabbi more than $3 or $4 a week, and often, instead of having a regular salary, he is reduced to occasional fees for his services at weddings, births and holy festivals generally. Some very poor congregations get along without a rabbi at all, hiring one for special occasions, 62 but these are congregations which are falling off somewhat from their orthodox strictness.

The result of this state of affairs is a pretty general falling off in the character of the rabbis. In Russia they are learned men—know the Talmud and all the commentaries upon it by heart—and have degrees from the rabbinical colleges, but here they are often without degrees, frequently know comparatively little about the Talmud, and are sometimes actuated by worldly motives. A few Jews coming to New York from some small Russian town, will often select for a rabbi the man among them who knows a little more of the Talmud than the others, whether he has ever studied for the calling or not. Then, again, some mere adventurers get into the position—men good for nothing, looking for a position. They clap a high hat on their heads, impose on a poor congregation with their up-to-dateness and become rabbis without learning or piety. These "fake" rabbis—"rabbis for business only"—are often satirized in the Yiddish plays given at the Bowery theatres. On the stage they 63 are ridiculous figures, ape American manners in bad accents, and have a keen eye for gain.

The genuine, pious rabbis in the New York Ghetto feel, consequently, that they have their grievances. They, the accomplished interpreters of the Jewish law, are well-nigh submerged by the frauds that flood the city. But this is not the only sorrow of the "real" rabbi of the Ghetto. The rabbis uptown, the rich rabbis, pay little attention to the sufferings, moral and physical, of their downtown brethren. For the most part the uptown rabbi is of the German, the downtown rabbi of the Russian branch of the Jewish race, and these two divisions of the Hebrews hate one another like poison. Last winter when Zangwill's dramatized Children of the Ghetto was produced in New York the organs of the swell uptown German-Jew protested that it was a pity to represent faithfully in art the sordidness as well as the beauty of the poor Russian Ghetto Jew. It seemed particularly baneful that the religious customs of the Jews should be thus detailed upon the stage. The uptown Jew felt a little ashamed that the proletarians of his people should be made the subject of literature. The downtown Jews, the Russian Jews, however, received play and stories with delight, as expressing truthfully their life and character, of which they are not ashamed. 64

Another cause of irritation between the downtown and uptown rabbis is a difference of religion. The uptown rabbi, representing congregations larger in this country and more American in comfort and tendency, generally is of the "reformed" complexion, a hateful thought to the orthodox downtown rabbi, who is loath to admit that the term rabbi fits these swell German preachers. He maintains that, since the uptown rabbi is, as a rule, not only "reformed" in faith, but in preaching as well, he is in reality no rabbi, for, properly speaking, a rabbi is simply an interpreter of the law, one with whom the Talmudical wisdom rests, and who alone can give it out; not one who exhorts, but who, on application, can untie knotty points of the law. The uptown rabbis they call "preachers," with some disdain.

So that the poor, downtrodden rabbis—those among them who look upon themselves as the only genuine—have many annoyances to bear. Despised and neglected by their rich brethren, without honor or support in their own poor communities, and surrounded by a rabble of unworthy rivals, the "real" interpreter of the "law" in New York is something of an object of pity.

Just who the most genuine downtown rabbis 65 are is, no doubt, a matter of dispute. I will not attempt to determine, but will quote in substance a statement of Rabbi Weiss as to genuine rabbis, which will include a curious section of the history of the Ghetto. He is a jolly old man, and smokes his pipe in a tenement-house room containing 200 books of the Talmud and allied writings.

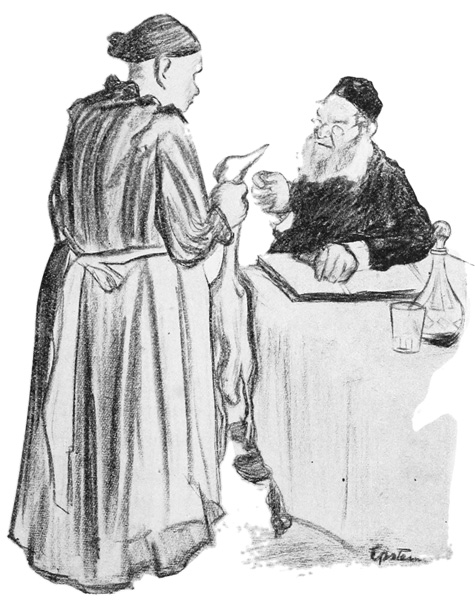

"A genuine rabbi," he said, "knows the law, and sits most of the time in his room, ready to impart it. If an old woman comes in with a goose that has been killed, the rabbi can tell her, after she has explained how the animal met its death, whether or not it is koshur, whether it may be eaten or not. And on any other point of diet or general moral or physical hygiene the rabbi is ready to explain the law of the Hebrews from the time of Adam until to-day. It is he who settles many of the quarrels of the neighborhood. The poor sweat-shop Jew comes to complain of his "boss," the old woman to tell him her dreams and get his interpretation of them, the young girl to weigh with him questions of amorous etiquette. Our children do not need to go to the Yiddish theatres to learn about "greenhorn" types. They see all sorts of Ghetto Jews in the house of the rabbi, their father.

"I myself was the first genuine rabbi on the 66 east side of New York. I am now sixty-two years old, and came here sixteen years ago—came for pleasure, but my wife followed me, and so I had to stay."

Here the old rabbi smiled cheerfully. "When I came to New York," he proceeded, "I found the Jews here in a very bad way—eating meat that was "thrapho," not allowed, because killed improperly; literally, killed by a brute. The slaughter-houses at that time had no rabbi to see that the meat was properly killed, was koshur—all right.

"You can imagine my horror. The slaughter-houses had been employing an orthodox Jew, who, however, was not a rabbi, to see that the meat was properly killed, and he had been doing things all wrong, and the chosen people had been living abominably. I immediately explained the proper way of killing meat, and since then I have regulated several slaughter-houses and make my living in that way. I am also rabbi of a congregation, but it is so small that it doesn't pay. The slaughter-houses are more profitable."

THE RABBI CAN TELL WHETHER OR NOT IT IS KOSHUR

These "submerged" rabbis are not always quite fair to one another. Some east side authorities maintain that the "orthodox Jew" of whom Rabbi Weiss spoke thus contemptuously, was 68 one of the finest rabbis who ever came to New York, one of the most erudite of Talmudic scholars. Many congregations united to call him to America in 1887, so great was his renown in Russia. But when he reached New York the general fate of the intelligent adult immigrant overtook him. Even the "orthodox" in New York looked upon him as a "greenhorn" and deemed his sermons out-of-date. He was inclined, too, to insist upon a stricter observance of the law than suited their lax American ideas. So he, too, famous in Russia, rapidly became one of the "submerged."

One of the most learned, dignified and impressive rabbis of the east side is Rabbi Vidrovitch. He was a rabbi for forty years in Russia, and for nine years in New York. Like all true rabbis he does not preach, but merely sits in his home and expounds the "law." He employs the Socratic method of instruction, and is very keen in his indirect mode of argument. Keenness, indeed, seems to be the general result of the hair-splitting Rabbinical education. The uptown rabbis, "preachers," as the down-town rabbi contemptuously calls them, send many letters to Rabbi Vidrovitch seeking his help in the untying of knotty points of the "law." It was from him that Israel Zangwill, when the Children of the 69 Ghetto was produced on the New York stage, obtained a minute description of the orthodox marriage ceremonies. Zangwill caused to be taken several flash-light photographs of the old rabbi, surrounded by his books and dressed in his official garments.

There are many congregations in the New York Ghetto which have no rabbis and many rabbis who have no congregations. Two rabbis who have no congregations are Rabbi Beinush and Rabbi, or rather, Cantor, Weiss. Rabbi Weiss would say of Beinush that he is a man who knows the Talmud, but has no diploma. Rabbi Beinush is an extremely poor rabbi with neither congregation nor slaughter-houses, who sits in his poor room and occasionally sells his wisdom to a fishwife who wants to know if some piece of meat is koshur or not. He is down on the rich up-town rabbis, who care nothing for the law, as he puts it, and who leave the poor down-town rabbi to starve.

Cantor Weiss is also without a job. The duty of the cantor is to sing the prayer in the congregation, but Cantor Weiss sings only on holidays, for he is not paid enough, he says, to work regularly, the cantor sharing in this country a fate similar to that of the rabbi. The famous comedian of the Ghetto, Mogolesco, was, as a boy, 70 one of the most noted cantors in Russia. As an actor in the New York Ghetto he makes twenty times as much money as the most accomplished cantor here. Cantor Weiss is very bitter against the up-town cantors: "They shorten the prayer," he said. "They are not orthodox. It is too hot in the synagogue for the comfortable up-town cantors to pray."

Comfortable Philistinism, progress and enlightment up town; and poverty, orthodoxy and patriotic and religious sentiment, with a touch of the material also, down town. Such seems to be the difference between the German and the Russian Jew in this country, and in particular between the German and Russian Jewish rabbi. 71

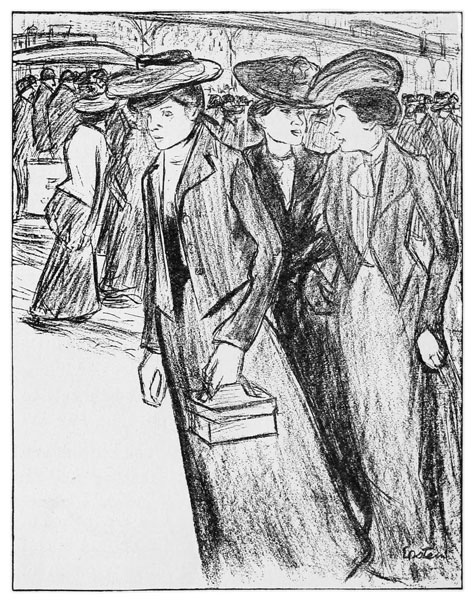

The women present in many respects a marked contrast to their American sisters. Substance as opposed to form, simplicity of mood as opposed to capriciousness, seem to be in broad lines their relative qualities. They have comparatively few états d'ame; but those few are revealed with directness and passion. They lack the subtle charm of the American woman, who is full of feminine devices, complicated flirtatiousness; who in her dress and personal appearance seeks the plastic epigram, and in her talk and relation to the world an indirect suggestive delicacy. They are poor in physical estate; many work or have worked; even the comparatively educated among them, in the sweat-shops, are undernourished and lack the physical well-being and consequent temperamental buoyancy which are comforting qualities of the well-bred American woman. Unhappy in circumstances, they are predominatingly serious in nature, and, if they lack alertness to the social nuance, have yet a compelling appeal which consists in headlong 72 devotion to a duty, a principle or a person. As their men do not treat them with the scrupulous deference given their American sisters, they do not so delightfully abound in their own sense, do not so complexedly work out their own natures, and lack variety and grace. On the other hand, they are more apt to abound in the sense of something outside of themselves, and carry to their love affairs the same devoted warmth that they put into principle.

The first of the two well-marked classes of women in the Ghetto is that of the ignorant orthodox Russian Jewess. She has no language but Yiddish, no learning but the Talmudic law, no practical authority but that of her husband and her rabbi. She is even more of a Hausfrau than the German wife. She can own no property, and the precepts of the Talmud as applied to her conduct are largely limited to the relations with her husband. Her life is absorbed in observing the religious law and in taking care of her numerous children. She is drab and plain in appearance, with a thick waist, a wig, and as far as is possible for a woman a contempt for ornament. She is, however, with the noticeable assimilative sensitiveness of the Jew, beginning 73 to pick up some of the ways of the American woman. If she is young when she comes to America, she soon lays aside her wig, and sometimes assumes the rakish American hat, prides herself on her bad English, and grows slack in the observance of Jewish holidays and the dietary regulations of the Talmud. Altho it is against the law of this religion to go to the theatre, large audiences, mainly drawn from the 74 ignorant workers of the sweat-shops and the fishwives and pedlers of the push-cart markets, flock to the Bowery houses. It is this class which forms the large background of the community, the masses from which more cultivated types are developing.

HER LIFE IS ABSORBED IN OBSERVING THE RELIGIOUS LAW

Many a literary sketch in the newspapers of the quarter portrays these ignorant, simple, devout, housewifely creatures in comic or pathetic, more often, after the satiric manner of the Jewish writers, in serio-comic vein. The authors, altho they are much more educated, yet write of these women, even when they write in comic fashion, with fundamental sympathy. They picture them working devotedly in the shop or at home for their husbands and families, they represent the sorrow and simple jealousy of the wife whose husband's imagination, perhaps, is carried away by the piquant manner and dress of a Jewess who is beginning to ape American ways; they tell of the comic adventures in America of the newly-arrived Jewess: how she goes to the theatre, perhaps, and enacts the part of Partridge at the play. More fundamentally, they relate how the poor woman is deeply shocked, at her arrival, by the change which a few years have made in the character of her husband, who had come to America before her 75 in order to make a fortune. She finds his beard shaved off, and his manners in regard to religious holidays very slack. She is sometimes so deeply affected that she does not recover. More often she grows to feel the reason and eloquence of the change and becomes partly accustomed to the situation; but all through her life she continues to be dismayed by the precocity, irreligion and Americanism of her children. Many sketches and many scenes in the Ghetto plays present her as a pathetic "greenhorn" who, while she is loved by her children, is yet rather patronized and pitied by them.

In "Gott, Mensch und Teufel," a Yiddish adaptation of the Faust idea, one of these simple religious souls is dramatically portrayed. The restless Jewish Faust, his soul corrupted by the love of money, puts aside his faithful wife in order to marry another woman who has pleased his eye. He uses as an excuse the fact that his marriage is childless, and as such rendered void in accordance with the precepts of the religious law. His poor old wife submits almost with reverence to the double authority of husband and Talmud, and with humble demeanor and tears streaming from her eyes begs the privilege of taking care of the children of her successor. 76

In "The Slaughter" there is a scene which picturesquely portrays the love of the poor Jew and the poor Jewess for their children. The wife is married to a brute, whom she hates, and between the members of the two families there is no relation but that of ugly sordidness. But when it is known that a child is to be born they are all filled with the greatest joy. The husband is ecstatic and they have a great feast, drink, sing and dance, and the young wife is lyrically happy for the first time since her marriage.

Many little newspaper sketches portray the simple sweat-shop Jewess of the ordinary affectionate type, who is exclusively minded so far as her husband's growing interest in the showy American Jewess is concerned. Cahan's novel, "Yekel," is the Ghetto masterpiece in the portrayal of these two types of women—the wronged "greenhorn" who has just come from Russia, and she who, with a rakish hat and bad English, is becoming an American girl with strange power to alienate the husband's affections.