Larger Image

OR,

IRELAND’S ANCIENT SCHOOLS AND SCHOLARS

BY THE

MOST REV. JOHN HEALY, D.D., LL.D., M.R.I.A.,

BISHOP OF CLONFERT; COMMISSIONER FOR THE PUBLICATION

OF THE BREHON LAWS; EX-PREFECT OF THE DUNBOYNE

ESTABLISHMENT, MAYNOOTH COLLEGE.

SIXTH EDITION.

DUBLIN:

SEALY, BRYERS & WALKER,

86 Middle Abbey Street.

M. H. GILL & SON,

50 Upper O’Connell Street.

LONDON: BURNS & OATES, Limited,

28 Orchard Street, W., and 63 Paternoster Row, E.C..

New York, Cincinnati and Chicago:

BENZIGER BROTHERS.

1912.

PRINTED BY

SEALY, BRYERS AND WALKER,

MIDDLE ABBEY STREET,

DUBLIN.

PREFACE TO THE FOURTH EDITION.

Some smaller inaccuracies in the previous Editions have been corrected in this Edition; but no other changes have been made.

✠ JOHN HEALY, D.D.,

Bishop of Clonfert.

Mount St. Bernard,

October, 1902.

PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION.

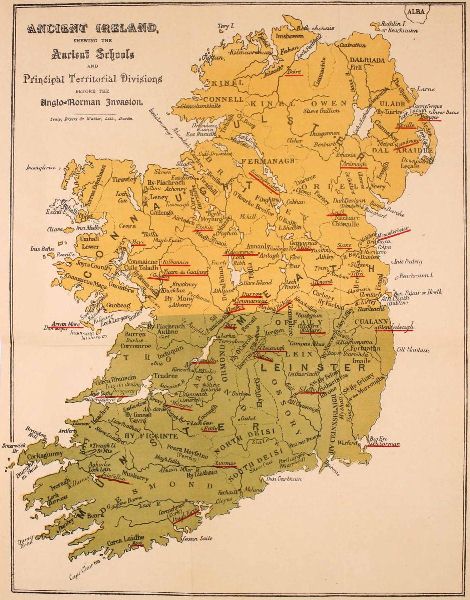

The First Edition of this work has been very favourably received both by the critics and by the public. It was exhausted nearly twelve months ago; but other engrossing occupations left the author little time to revise the text and prepare a new edition. In this Second Edition many errors of the press have been corrected; several explanatory notes have been added, and some few inaccuracies have been rectified. Maps of the Aran Islands and Clonmacnoise have been inserted, and the Index has been greatly enlarged. It is hoped also, that the lower price of the present edition will bring it within the range of a wider circle of readers, and still further carry out the author’s purpose of vindicating and enlarging the just renown of Ireland’s ancient Saints and Scholars.

✠ JOHN HEALY, D.D.

Mount St. Bernard,

Easter, 1893.

PREFACE.

In the following pages it has been the author’s purpose to give a full and accurate, but at the same time, as he hopes, a popular account of the Schools and Scholars of Ancient Ireland. It is a subject about which much is talked, but little is known, and even that little is only to be found in volumes that are not easily accessible to the general reader. In the present work the history of the Schools and Scholars of Celtic Erin is traced from the time of St. Patrick down to the Anglo-Norman Invasion of Ireland. The first three centuries of this period is certainly the brightest page of what is, on the whole, the rather saddening, but not inglorious record, of our country’s history. It was not by any means a period altogether free from violence and crime, but it was certainly a time of comparative peace and security, during which the religious communities scattered over the island presented a more beautiful spectacle before men and angels, than anything seen in Christendom either before or since. It is an epoch, too, whose history can be studied with pleasure and profit, and in which Irishmen of all creeds and classes feel a legitimate pride.

It has been questioned, indeed, if the Monastic Schools of this period were really so celebrated and so frequented by holy men, as justly to win for Ireland her ancient title of the Insula Sanctorum et Doctorum—the Island of Saints and Scholars. The author ventures to hope that the following pages will furnish, even to the most sceptical, conclusive evidence on this point. It has been his purpose to show not merely the extent, the variety, and the character of the studies, both sacred and profane, pursued in our Celtic Schools, but also[Pg vii] the eminent sanctity of those learned men, whose names are found in all our domestic Martyrologies.

Perhaps the most striking feature in their character, speaking generally, was their extraordinary love of solitude and mortification. They loved learning much, it is true; but they loved God and nature more. They knew nothing of what is now called civilization, and were altogether ignorant of urban life; but still they had a very keen perception of the grandeur and beauty of God’s universe. The voice of the storm and the strength of the sea, the majesty of lofty mountains and the glory of summer woods, spoke to their hearts even more eloquently than the voice of the preacher, or the writing on their parchments.

The author has sought throughout to put all the information, which he could collect in reference to his subject, in a popular and attractive form. At the same time he has spared no pains to consult all the available authorities both ancient and modern; and he has always gone to the original sources, whenever it was possible to do so. He does not pretend to have avoided all mistakes in matters of fact, nor to be quite free from errors in matters of opinion. But he can say that he has honestly done his best to make the study of this portion of our Celtic history interesting and profitable to the general reader. And there is no doubt that the study of the holy and self-denying lives of our ancient Saints and Scholars will exercise a purifying and elevating influence on the minds of all, but more especially of the young; will teach them to raise their thoughts to higher things, and set less store on the paltry surroundings of their daily life.

With the single exception of Iona, which may be considered as an Irish island, this volume deals only with our Monastic Schools at home. Irishmen founded during this period many schools and monasteries abroad; but[Pg viii] it would require another volume to give a full account of those monasteries and their holy founders.

There are many friends to whom we owe thanks for assistance; but we have reason to believe that they would prefer not to have their names mentioned in this preface.

In conclusion, we have only to add, that these pages have not been written in a controversial spirit; because in our opinion little or nothing is ever to be gained by writing history in a spirit of controversy, which tends rather to obscure than to make known the truth. It is better from every point of view to let the facts speak for themselves; and hence not only in quoting authorities, but also in narrating events, we have, as far as possible, reproduced the language of the original authorities.

A few of the papers here published have appeared in the Irish Ecclesiastical Record, but they are now presented in a more popular form.

✠ JOHN HEALY, D.D.

Palmerston House, Portumna,

May, 1890.

“May the tongue of Sage and Saint be lasting.”

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER I. | PAGE | |

| STATE OF LEARNING IN IRELAND BEFORE ST. PATRICK. | ||

| I.— | The Druids | 1 |

| Learning of the Druids | 1 | |

| Religious Worship | 2 | |

| Sacrifice of Human Victims | 3 | |

| Worship of the Elements | 3 | |

| Enchantments | 4 | |

| Acquaintance with Letters | 4 | |

| Sun-Worship | 5 | |

| II.— | The Bards | 7 |

| The Files | 7 | |

| The Ollamh-Poet | 7 | |

| Historic Poet | 8 | |

| Neidhe | 9 | |

| Ollioll Olum | 10 | |

| Ossian | 10 | |

| III.— | The Brehons | 11 |

| Office of Brehon thrown open to all possessing necessary qualifications | 11 | |

| Morann | 12 | |

| Their Course of Instruction | 12 | |

| IV.— | The Ogham Alphabet | 13 |

| Inscribed Stones | 13 | |

| Invention of the Ogham | 14 | |

| Letters of the Ogham Alphabet | 15 | |

| CHAPTER II. | ||

| IRISH SCHOLARS BEFORE ST. PATRICK. | ||

| I.— | Cormac Mac Art | 16 |

| Battle of Magh Mucruimhe | 17 | |

| Fenian Militia | 18 | |

| Finn Mac Cumhail | 19 | |

| Feis of Tara | 19 | |

| The Teach Miodhchuarta | 21 | |

| Writings ascribed to Cormac | 23 | |

| Saltair of Tara | 23 | |

| Schools at Tara | 23 | |

| Book of Aicill | 25 | |

| Death of Cormac | 26 | |

| Torna Eigas | 28 | |

| II.— | Sedulius | 29 |

| Evidence of Irish Birth | 29 | |

| Religious Training | 32 | |

| Writings of Sedulius | 35 | |

| Carmen Paschale | 36 | |

| Elegiac Poems | 37 | |

| III.— | Caelestius and Pelagius | 39 |

| Caelestius not an Irishman | 39 | |

| Pelagius of British Birth, but of Scottish Origin | 40 | |

| No evidence to show that Caelestius was either a Briton or Scot—His Character | 41 | |

| CHAPTER III. | ||

| LEARNING IN IRELAND IN THE TIME OF ST. PATRICK. | ||

| I.— | St. Patrick’s Education | 43 |

| Life at Marmoutier | 44 | |

| St. Germanus of Auxerre | 46 | |

| Patrick accompanied Germanus on his journey to Britain, A.D. 429 | 48 | |

| St. Patrick in the Island of Lerins | 49 | |

| St. Patrick commissioned by St. Celestine to Preach the Gospel in Ireland | 50 | |

| II.— | St. Patrick’s Literary Labour in Ireland | 50 |

| Arrival in Ireland | 50 | |

| He lights the Paschal Fire | 51 | |

| Miraculous Destruction of the two Chief Druids of Erin | 51 | |

| Patrick burns the idolatrous books at Tara and overturns the idols in Leitrim | 52 | |

| [Pg x]III.— | St. Patrick Reforms the Brehon Laws | 52 |

| The Senchus Mor | 52 | |

| Commission of Nine | 53 | |

| Benignus | 54 | |

| Church Organization | 55 | |

| Friendly Alliance with the Bards | 57 | |

| Church Music | 58 | |

| St. Patrick accompanied by Bishops and Priests in his Mission to Ireland | 59 | |

| Synod of Patrick, Auxilius and Iserninus | 60 | |

| Holy See Supreme Judge of Controversies | 60 | |

| Duties of Ecclesiastical Judges and Kings | 61 | |

| Oral Instruction communicated by St. Patrick to his Disciples during Missionary Journeys | 62 | |

| Books used by St. Patrick | 63 | |

| Elements, or “Alphabets” of Christian Doctrine | 63 | |

| Equipment of the young Priest beginning his Missionary Work | 64 | |

| Patrick’s Household | 65 | |

| Patrick’s Artificers | 66 | |

| CHAPTER IV. | ||

| THE WRITINGS OF SAINT PATRICK AND OF HIS DISCIPLES. | ||

| I.— | St. Patrick’s Confession | 67 |

| Evidence in favour of its authenticity | 68 | |

| The Saint’s motive in writing it | 69 | |

| Patrick’s parents in Britain | 71 | |

| Patrick met opposition in preaching the Gospel in Ireland | 72 | |

| II.— | The Epistle to Coroticus | 73 |

| III.— | The Lorica, or the Deer’s Cry | 75 |

| IV.— | Sechnall’s Hymn of St. Patrick | 77 |

| Secundinus | 77 | |

| Sechnall, son of Patrick’s sister, Darerca | 79 | |

| Sechnall’s father | 79 | |

| V.— | The Hymn Sancti Venite | 80 |

| St. Sechnall the first Christian Poet in Erin | 81 | |

| VI.— | St. Fiacc of Sletty | 81 |

| Fiacc receives grade or orders | 83 | |

| He founds two Churches | 83 | |

| Fiacc’s Metrical Life of St. Patrick | 85 | |

| VII.— | The Sayings of Saint Patrick | 87 |

| VIII.— | The Tripartite Life of St. Patrick | 88 |

| Its date and authorship | 89 | |

| CHAPTER V. | ||

| IRISH MONASTIC SCHOOLS IN GENERAL. | ||

| I.— | General View of an Irish Monastery | 91 |

| Monasticism always existed and always will exist in the Church | 92 | |

| St. Martin of Tours, the Father of Monasticism in Gaul | 93 | |

| II.— | The Buildings | 94 |

| Cells of the Monks | 95 | |

| Monastic Hospitality | 96 | |

| III.— | Discipline | 97 |

| The Abbot | 98 | |

| The Monastic Family | 99 | |

| The Rule | 99 | |

| Food | 101 | |

| Ordinary Dress | 102 | |

| IV.— | The Daily Labour of the Monastery | 102 |

| Religious Exercises | 103 | |

| Study | 103 | |

| Writing | 104 | |

| Manual Labour | 104 | |

| Church Furniture | 105 | |

| V.— | The Three Orders of Irish Saints | 106 |

| CHAPTER VI. | ||

| SCHOOLS OF THE FIFTH CENTURY. | ||

| I.— | The Schools of Armagh | 110 |

| Emania | 111 | |

| Daire | 111 | |

| Patrick founds Armagh | 112 | |

| [Pg xi] | Ecclesiastical Buildings at Armagh | 113 |

| St. Benignus | 114 | |

| Death of Benignus | 116 | |

| The Book of Rights attributed to Benignus | 116 | |

| The School of Armagh, primarily a great Theological Seminary | 117 | |

| The Moralia of St. Gregory the Great | 117 | |

| Gildas the Wise | 118 | |

| His Destruction of Britain | 119 | |

| English Students at Armagh | 119 | |

| Churches and Schools of Armagh burned and plundered between A.D. 670 and 1179 | 120 | |

| Imar O’Hagan | 121 | |

| The Book of Armagh | 122 | |

| The Mac Moyres | 124 | |

| II.— | The School of Kildare | 125 |

| St. Brigid | 125 | |

| St. Mathona | 126 | |

| St. Ita | 127 | |

| St. Brigid born at Faughart | 128 | |

| Events of her marvellous history | 129 | |

| Brigid’s religious vows | 130 | |

| Brigid founds Kildare | 130 | |

| Brigid the “Mary of Ireland” | 131 | |

| Monastery of Men at Kildare | 132 | |

| St. Conlaeth | 132 | |

| St. Ninnidhius | 132 | |

| Great Church of Kildare | 133 | |

| Six Lives of St. Brigid | 133 | |

| St. Brogan Cloen | 134 | |

| Cogitosus | 135 | |

| Round Tower of Kildare | 138 | |

| Perpetual fire of Kildare | 138 | |

| Art of Illumination in the Monastic Schools of Kildare | 139 | |

| The Book of Leinster | 140 | |

| CHAPTER VII. | ||

| MINOR MONASTIC SCHOOLS OF THE FIFTH CENTURY. | ||

| I.— | The School of Noendrum | 141 |

| St. Mochae | 141 | |

| St. Colman of Dromore | 143 | |

| Mochae of Noendrum enchanted for 150 years by the song of a Blackbird | 144 | |

| II.— | The School of Louth | 145 |

| St. Mochta | 145 | |

| School founded | 147 | |

| The Druid Hoam | 147 | |

| Book of Cuana | 149 | |

| III.— | The School of Emly | 149 |

| St. Ailbe | 149 | |

| Pre-Patrician Bishops in Ireland | 150 | |

| Life of St. Ailbe of Emly | 151 | |

| Ailbe preached the Gospel in Connaught | 152 | |

| Life of St. Declan | 153 | |

| Sts. Ciaran, Ailbe, Declan, and Ibar yield subjection and supremacy to Patrick | 153 | |

| Difficulties against the authenticity of the Lives of St. Ciaran, St. Declan, and St. Ailbe | 155 | |

| IV.— | St. Ibar | 155 |

| Beg-Eri | 156 | |

| School of Beg-Eri | 157 | |

| Beg-Eri no longer an Island | 158 | |

| V.— | Early Schools in the West of Ireland | 159 |

| College at Cluainfois | 160 | |

| School of St. Asicus of Elphin | 161 | |

| CHAPTER VIII. | ||

| SCHOOLS OF THE SIXTH CENTURY. THE MONASTIC SCHOOL OF ST. ENDA OF ARAN. | ||

| I.— | Life of St. Enda of Aran | 163 |

| Monastic Character of the Early Irish Church | 163 | |

| Family of St. Enda | 164 | |

| His Sister, St. Fanchea | 165 | |

| He goes to Candida Casa | 167 | |

| Goes to Aran | 169 | |

| II.— | The Isles of Aran | 169 |

| Aran Mor | 170 | |

| III.— | Pagan Remains in the Isles of Aran | 172 |

| Dun Ængusa | 173 | |

| Dun Conchobhair | 175 | |

| These Islands in ancient times the stronghold of a Warrior Race | 176 | |

| [Pg xii]IV.— | Christian Aran of St. Enda | 177 |

| The Curragh Stone | 177 | |

| Enda founded his First Monastery at Killeany | 177 | |

| Scholars of St. Enda | 178 | |

| Columba and Ciaran at Aran | 179 | |

| The Life of Enda and his Monks, simple and austere | 180 | |

| V.— | Ancient Churches in Aran | 181 |

| Churches in Townland of Killeany | 181 | |

| Telagh-Enda | 182 | |

| The “Seven Churches” | 182 | |

| The Tomb of St. Brecan | 183 | |

| The Septem Romani | 184 | |

| Ruins at Kilmurvey | 185 | |

| Tempull na-Cheathair-Aluinn | 186 | |

| CHAPTER IX. | ||

| THE SCHOOL OF ST. FINNIAN OF CLONARD. | ||

| I.— | Preliminary Sketch of Christian Schools | 188 |

| The First Christian Schools | 188 | |

| Schools of the Pagans | 189 | |

| Episcopal Schools | 190 | |

| School founded by John Cassian near Marseilles | 190 | |

| Monastery of Lerins | 192 | |

| II.— | St. Finnian of Clonard | 193 |

| Finnian’s birth | 194 | |

| Goes to Britain | 195 | |

| Dubricius | 196 | |

| St. David | 196 | |

| Cathmael | 197 | |

| Finnian returns to Erin | 198 | |

| III.— | The School of Clonard | 199 |

| Scholars of Clonard | 201 | |

| Instruction altogether oral | 202 | |

| Knowledge of the Sacred Scriptures | 203 | |

| “Tutor of the Saints of Ireland” | 203 | |

| Remains at Clonard | 205 | |

| St. Aileran the Wise | 206 | |

| CHAPTER X. | ||

| THE SCHOOL OF CLONFERT. | ||

| I.— | St. Brendan of Clonfert | 209 |

| Fostered by St. Ita | 211 | |

| Brendan’s progress in learning under St. Erc | 211 | |

| Seminary at Cluainfois | 212 | |

| Brendan’s Rule | 213 | |

| St. Brendan’s Oratory on the summit of Brandon Hill | 214 | |

| Brendan’s Voyages | 215 | |

| He goes to Britain | 217 | |

| The Cursing of Tara | 218 | |

| He founds the Monastery of Inchiquin | 219 | |

| Founds Clonfert | 220 | |

| Death of Brendan | 221 | |

| II.— | St. Moinenn | 222 |

| St. Fintan | 224 | |

| The Abbot Seanach Garbh | 225 | |

| St. Fursey | 226 | |

| Birth of Fursey | 227 | |

| III.— | St. Cummian the Tall, Bishop of Clonfert | 228 |

| Birth of Cummian | 229 | |

| Pupil of St. Finbar | 230 | |

| Cummian and King Domhnall | 232 | |

| Paschal Controversy | 233 | |

| The Irish Usage | 234 | |

| Main charge brought against the Irish | 235 | |

| A National Synod at Magh Lene | 236 | |

| Cummian’s Paschal Epistle | 237 | |

| He appeals to the authority of the Church | 238 | |

| Quotes the Synodical Decrees of St. Patrick | 239 | |

| The Liber de Mensura Poenitentiarum | 240 | |

| IV.— | Subsequent History of Clonfert | 242 |

| Turgesius and the Danes | 242 | |

| Old Cathedral of Clonfert | 243 | |

| CHAPTER XI. | ||

| THE SCHOOL OF MOVILLE. | ||

| I.— | St. Finnian of Moville | 245 |

| His Boyhood and Education | 246 | |

| Candida Casa | 246 | |

| Finnian at Candida Casa | 247 | |

| He goes to Rome | 248 | |

| Returns to Ireland and founds a School at Moville | 249 | |

| Columcille’s Copy of St. Finnian’s Psaltery | 251 | |

| [Pg xiii] | The Cathach | 252 |

| St. Finnian’s Rule | 253 | |

| His Death | 254 | |

| The Hymn of St. Colman | 255 | |

| II.— | Marianus Scotus | 256 |

| CHAPTER XII. | ||

| THE SCHOOL OF CLONMACNOISE. | ||

| I.— | St. Ciaran of Clonmacnoise | 258 |

| Clonmacnoise | 258 | |

| St. Ciaran at the School of Clonard | 259 | |

| He goes to Aran | 260 | |

| Visits St. Senan at Scattery | 261 | |

| Founds Churches at Isell Ciaran and Hare Island, and the Monastery at Clonmacnoise | 261 | |

| Origin of the Diocese of Clonmacnoise | 262 | |

| Death of St. Ciaran | 263 | |

| Festival of St. Ciaran | 264 | |

| The Eclais Beg | 265 | |

| II.— | The Ruined Churches at Clonmacnoise | 266 |

| Round Tower | 267 | |

| O’Rourke’s Tower | 268 | |

| De Lacy’s Castle | 269 | |

| Inscribed Tombstones | 269 | |

| III.— | The Scholars of Clonmacnoise | 270 |

| Grants to the School of Clonmacnoise | 271 | |

| Colgan, or Colgu the Wise | 272 | |

| Alcuin | 272 | |

| The Ferleginds | 273 | |

| The Prayer of St. Colgu | 273 | |

| Scuap Chrabhaigh | 274 | |

| Plundered by the Danes | 274 | |

| Felim Mac Criffan | 275 | |

| IV.— | Annalists of Clonmacnoise | 276 |

| Tighernach | 276 | |

| Chronicon Scotorum | 278 | |

| Gilla-Christ O’Maeileon | 279 | |

| Annals of Clonmacnoise | 279 | |

| V.— | The “Leabhar-na-h-Uidhre” | 280 |

| Conn-na-m-Bocht | 280 | |

| VI.— | Dicuil, the Geographer | 281 |

| The De Mensura Orbis Terrarum | 281 | |

| His Learning | 284 | |

| Irish Pilgrimage to Jerusalem | 285 | |

| The “Barns of Joseph” | 286 | |

| Dicuil’s reference to Iceland | 287 | |

| Love of the Ancient Irish Monks for island solitudes | 288 | |

| Iceland and the Faroe Isles occupied by Irish Monks prior to discovery of these islands by the Danes | 289 | |

| Dicuil’s testimony that Sedulius was an Irishman | 290 | |

| CHAPTER XIII. | ||

| THE COLUMBIAN SCHOOLS IN IRELAND. | ||

| I.— | St. Columba’s Education | 291 |

| St. Columba, a typical Celt | 291 | |

| Early History | 292 | |

| Goes to the School of St. Finnian at Moville | 294 | |

| Columba at the School of Clonard | 295 | |

| Columba at Glasnevin | 296 | |

| He returns to his native territory | 297 | |

| II.— | Columba founds Derry | 298 |

| Columcille’s original Church | 298 | |

| Personal description of Columba | 299 | |

| III.— | The Schools of Durrow and Kells | 301 |

| Columba founded the Monastery of Durrow | 301 | |

| Interesting incidents | 302 | |

| Cormac Ua Liathain | 303 | |

| The Book of Durrow | 304 | |

| Ancient remains at Durrow | 305 | |

| Assassination of De Lacy | 306 | |

| IV.— | The Foundation of Kells | 306 |

| King Diarmait | 306 | |

| St. Columba’s House | 308 | |

| Round Tower of Kells | 309 | |

| Book of Kells | 309 | |

| This MS. caused the Battle of Cuil-Dreimhne | 310 | |

| Columba’s departure from Derry | 312 | |

| Port-a-Churraich | 314 | |

| [Pg xiv] | ||

| CHAPTER XIV. | ||

| THE COLUMBIAN SCHOOL IN ALBA. | ||

| I.— | Iona | 315 |

| Columba settles in Iona | 316 | |

| Reilig Odhran | 317 | |

| Columba’s Monasteries | 318 | |

| Scribes in Iona | 319 | |

| Rule in Iona | 319 | |

| II.— | Columba Protects the Bards | 320 |

| Threatened destruction of the Bards | 320 | |

| Convention of Drumceat | 321 | |

| Columba’s defence of the Bards | 322 | |

| The Bardic Schools | 323 | |

| III.— | Death of Columba | 324 |

| IV.— | Writings of Columba | 326 |

| The Altus Prosator | 327 | |

| In te Christe | 328 | |

| Noli Pater | 328 | |

| Irish Poems attributed to Columcille | 329 | |

| Columba’s Prophecies | 329 | |

| V.— | Lives of Columcille | 330 |

| VI.— | Other Scholars of Iona | 331 |

| Baithen | 331 | |

| Death of Baithen | 333 | |

| Laisren | 333 | |

| Seghine | 333 | |

| Suibhne | 334 | |

| Cuimine the Fair | 334 | |

| VII.— | Adamnan, Ninth Abbot of Hy | 335 |

| Greek Tongue taught in the School of Hy 1170 years ago | 336 | |

| Adamnan’s Birth | 336 | |

| His Parentage | 337 | |

| King Finnachta | 337 | |

| Adamnan goes to Iona | 338 | |

| Vita Columbae | 339 | |

| Adamnan introduces the new Paschal observance into Ireland | 341 | |

| Dispute between Adamnan and Finnachta | 342 | |

| Canon of Adamnan | 342 | |

| Death of Adamnan—relics transferred to Ireland | 343 | |

| Adamnan’s writings | 344 | |

| De Locis Sanctis | 344 | |

| Expulsion of the Columbian Monks by the Pictish King Nectan | 345 | |

| The “Gentiles” make their first descent on the Hebrides | 346 | |

| Martyrdom of St. Blaithmac | 347 | |

| The Rule of Columba | 347 | |

| CHAPTER XV. | ||

| THE LATER COLUMBIAN SCHOOLS IN IRELAND. | ||

| I.— | Kells Head of the Columbian Houses | 348 |

| Kells pillaged by the Danes | 348 | |

| The Cathach | 348 | |

| II.— | Marianus Scotus | 349 |

| Commentaries on the Epistles of St. Paul | 351 | |

| III.— | The Later School of Derry | 352 |

| The Ua Brolchain | 352 | |

| St. Maelisa O’Brolchain | 353 | |

| Flaithbhertach O’Brolchain | 354 | |

| The Abbot of Derry resolves to renovate his monastery and collects funds for the purpose | 355 | |

| Synod of the Clergy of Ireland convened at Bri Mac Taidgh in Laeghaire | 356 | |

| See of Derry established | 357 | |

| IV.— | Gelasius | 358 |

| His name of Mac Liag | 358 | |

| Gelasius becomes Abbot of Derry, | 359 | |

| He reforms the morals of clergy and people | 359 | |

| Synod of Kells | 360 | |

| Synod of Mellifont | 361 | |

| Synod of Brigh Mac-Taidgh | 361 | |

| Synod of Clane | 362 | |

| Gelasius consecrates St. Laurence O’Toole | 362 | |

| Death of Gelasius | 363 | |

| CHAPTER XVI. | ||

| THE SCHOOL OF BANGOR. | ||

| I.— | St. Comgall of Bangor | 364 |

| Birth and parentage | 365 | |

| Comgall enters the Monastery of Fintan | 366 | |

| [Pg xv]He visits Clonmacnoise, and receives the priesthood | 367 | |

| Description of Bangor | 367 | |

| St. Columba visits Comgall at Bangor | 368 | |

| The fame of Comgall attracts crowds to Bangor | 369 | |

| Death of Comgall | 370 | |

| II.— | St. Columbanus | 370 |

| His early life | 371 | |

| Goes to Cluaninis and places himself under the care of Sinell | 372 | |

| He enters Bangor | 372 | |

| Preaches the Gospel in Gaul | 373 | |

| He buries himself in the depths of the forest | 373 | |

| Increase of Disciples | 374 | |

| Founds a monastery at Luxeuil | 375 | |

| Columbanus and his Irish Monks banished from Luxeuil | 376 | |

| They establish themselves at Bregentz | 376 | |

| He founds the Monastic Church of Bobbio | 378 | |

| Death of Columbanus | 378 | |

| His writings | 379 | |

| The Bobbio Missal | 380 | |

| The Antiphonarium Benchorense | 381 | |

| III.— | Dungal | 381 |

| Theologian, astronomer and poet | 381 | |

| Dungal was an Irishman | 382 | |

| Probably educated in the School of Bangor | 382 | |

| Dungal goes to France | 382 | |

| His Letter to Charlemagne on the two solar eclipses said to have taken place in A.D. 810 | 383 | |

| He opens a school at Pavia | 385 | |

| The last struggle of Western Iconoclasm | 385 | |

| The Libri Carolini | 386 | |

| Synod of Frankfort | 386 | |

| The Council of Nice | 387 | |

| The Paris Conference | 388 | |

| Claudius of Turin | 389 | |

| Dungali Responsa contra perversas Claudii Taurinensis Episcopi Sententias | 390 | |

| Character of Dungal’s writings | 391 | |

| His death | 392 | |

| IV.— | St. Malachy | 393 |

| Sketch of his life | 393 | |

| He rebuilds the monastery at Bangor | 394 | |

| Becomes Bishop of Connor | 394 | |

| Founds the Monasterium Ibracense | 395 | |

| Malachy transferred to the Primatial See | 395 | |

| Difficulties in Armagh | 395 | |

| Malachy honoured at Rome by Pope Innocent III. | 396 | |

| Death at Clairvaux | 397 | |

| CHAPTER XVII. | ||

| THE SCHOOL OF CLONENAGH. | ||

| I.— | St. Fintan | 398 |

| Churches founded round the base of the Slieve Bloom mountains | 398 | |

| Clonenagh | 398 | |

| Fintan’s Rule | 401 | |

| St. Comgall a pupil of the School of Clonenagh | 402 | |

| Miracles of St. Fintan | 403 | |

| Fintan, “Father of the Irish Monks” | 404 | |

| II.— | St. Ængus | 404 |

| A Ceile De | 405 | |

| He leads a solitary life | 405 | |

| Dysert-Enos | 406 | |

| Penitential Exercises | 407 | |

| Ængus arrives at Tallagh | 407 | |

| Martyrology of Tallagh | 408 | |

| The Felire | 409 | |

| Fothadh-na-Canoine | 410 | |

| Invocation of the Saints | 411 | |

| The Saltair-na-Rann | 412 | |

| Opinions of Dr. Stokes with regard to the writings of Ængus | 412 | |

| Death of Ængus | 413 | |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | ||

| THE SCHOOL OF GLENDALOUGH. | ||

| I.— | St. Kevin | 414 |

| Sketch of his Life | 414 | |

| Kevin is placed under the care of St. Petroc | 415 | |

| He goes to Glendalough | 416 | |

| Description of Glendalough | 417 | |

| [Pg xvi]St. Kevin’s Bed | 418 | |

| Tempull-na-Skellig | 419 | |

| Glendalough, a Seminary of Saints and Scholars | 420 | |

| Kevin meets Columba, Comgall and Canice at the hill of Uisnech | 421 | |

| Death of Kevin | 421 | |

| Writings attributed to Kevin | 422 | |

| II.— | Ruins at Glendalough | 422 |

| The Cathedral | 423 | |

| St. Kevin’s Kitchen | 423 | |

| Our Lady’s Church | 424 | |

| Trinity Church | 424 | |

| Kevin’s Yew Tree | 425 | |

| III.— | St. Moling | 425 |

| St. Moling | 426 | |

| Teach Moling | 426 | |

| Moling becomes Bishop of Ferns | 427 | |

| Remission of the Cow-Tax | 428 | |

| Writings attributed to St. Moling | 429 | |

| Glendalough ravaged by the Danes | 429 | |

| “Gilla-na-naomh Laighen” | 430 | |

| CHAPTER XVIII.—(continued). | ||

| THE SCHOOL OF GLENDALOUGH. | ||

| St. Laurence O’Toole | 432 | |

| His Parentage | 433 | |

| He goes to Glendalough | 434 | |

| Lorcan as a Student | 435 | |

| He is placed at the head of St. Kevin’s Great Establishment | 436 | |

| Consecrated Archbishop of Dublin | 437 | |

| Synod of the Irish Prelates at Clane | 437 | |

| He reforms the Clergy | 437 | |

| His Spirit of Mortification and Prayer | 438 | |

| Dermott McMurrough and Maurice Fitzgerald attack Dublin | 440 | |

| He stimulates the slothful king, Rory O’Connor, to action | 441 | |

| Laurence O’Toole attends a General Council in Rome, and secures many privileges for the Church in Ireland | 443 | |

| He travels to England in the interests of Rory O’Connor the discrowned king | 444 | |

| Detained a prisoner in the monastery of Abingdon | 444 | |

| His death | 445 | |

| Canonization | 446 | |

| CHAPTER XIX. | ||

| SCHOOLS OF THE SEVENTH CENTURY. | ||

| I.— | The School of Lismore, St. Carthach | 447 |

| He visits the School of Bangor | 448 | |

| He founds a monastery at Rahan | 449 | |

| “Effugatio” of Carthach from Rahan | 450 | |

| He founds Lismore | 453 | |

| Retires from community life to prepare for death | 454 | |

| Miracles | 454 | |

| Rule of Carthach | 455 | |

| II.— | St. Cathaldus of Tarentum | 457 |

| The Life of St. Cathaldus | 457 | |

| His Birth-place | 458 | |

| A Student at Lismore | 460 | |

| He becomes a bishop | 461 | |

| See of Rachau | 462 | |

| Pilgrimage to Jerusalem | 462 | |

| Taranto | 463 | |

| Cathaldus endeavours to reform the licentious inhabitants of Taranto | 463 | |

| His death at Taranto | 464 | |

| Invention of the Saint’s Relics | 464 | |

| III.— | Other Scholars of Lismore | 465 |

| St. Cuanna | 465 | |

| St. Colman O’Leathain | 467 | |

| Aldfrid, King of Northumbria | 468 | |

| IV.— | Subsequent History of Lismore | 466 |

| Lismore ravaged by the Danes | 469 | |

| Scenery at Lismore | 471 | |

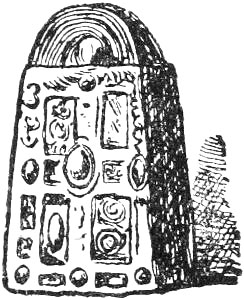

| Inscribed stones | 472 | |

| The Crozier of Lismore | 472 | |

| The Book of Lismore | 473 | |

| [Pg xvii] | ||

| CHAPTER XX. | ||

| THE SCHOOLS OF DESMOND. | ||

| I.— | The School of Cork | 475 |

| St. Finbarr | 476 | |

| Gougane Barra | 478 | |

| Cork in A.D. 1600 | 480 | |

| Death of St. Finbarr | 482 | |

| His character | 483 | |

| Assassination of Mahoun | 484 | |

| Giolla Aedha O’Muidhin | 486 | |

| II.— | St. Colman Mac Ua Cluasaigh | 487 |

| Pestilence in Ireland | 487 | |

| St. Colman’s Hymn | 488 | |

| III.— | The School of Ross | 490 |

| St. Fachtna | 490 | |

| Geographical Poem of Mac Cosse | 494 | |

| IV.— | The School of Innisfallen | 495 |

| St. Finan the Leper | 496 | |

| St. Finan Cam | 497 | |

| V.— | The Annals of Innisfallen | 500 |

| Maelsuthain O’Cearbhail | 500 | |

| Curious anecdote of Maelsuthain | 502 | |

| Annals of Innisfallen | 503 | |

| Description of Innisfallen | 505 | |

| CHAPTER XXI. | ||

| THE SCHOOLS OF THOMOND. | ||

| I.— | The School of Mungret | 506 |

| St. Nessan | 507 | |

| St. Munchin | 508 | |

| Mungret plundered by the Danes | 510 | |

| “The Learning of the Women of Mungret” | 511 | |

| II.— | The School of Iniscaltra | 513 |

| Island of Iniscaltra | 513 | |

| St. Columba of Terryglass | 513 | |

| Death of St. Columba | 515 | |

| St. Caimin | 517 | |

| Round Tower of Iniscaltra | 519 | |

| St. Caimin’s Church | 519 | |

| Sculptured stones | 520 | |

| Iniscaltra ravaged by the Danes | 521 | |

| III.— | Other Monastic Schools of Thomond | 522 |

| St. Brendan of Birr | 522 | |

| St. Cronan of Roscrea | 523 | |

| Book of Dimma | 524 | |

| CHAPTER XXII. | ||

| LATER SCHOOLS OF THE WEST. | ||

| I.— | St. Colman’s School of Mayo | 527 |

| The Easter Controversy | 527 | |

| Inisboffin | 531 | |

| Death of Colman | 533 | |

| II.— | St. Gerald of Mayo | 534 |

| Life of St. Gerald | 534 | |

| Adamnan promulgates the celebrated “Lex Innocentiae” | 537 | |

| Date of St. Gerald’s Death | 537 | |

| III.— | Subsequent History of the School of Mayo | 538 |

| Cele O’Duffy | 539 | |

| IV.— | The School of Tuam | 540 |

| St. Jarlath | 541 | |

| “Meadow of Retreat” | 542 | |

| St. Brendan visits St. Jarlath’s School at Cluainfois | 543 | |

| St. Jarlath founds Tuam | 544 | |

| CHAPTER XXII.—(continued). | ||

| CELTIC ART IN THE WESTERN MONASTERIES DURING THE REIGN OF TURLOUGH O’CONNOR. | ||

| I.— | The O’Duffys | 547 |

| II.— | Celtic Art at Clonmacnoise | 550 |

| The Ollamh-builder | 551 | |

| Gobban Saer | 551 | |

| Religh-na-Cailleach | 552 | |

| Crosses and Architectural Ornaments in Sculpture at Tuam and Cong | 554 | |

| Turlough rebuilds the Cathedral of Tuam | 557 | |

| The Abbey of Cong | 558 | |

| The Cross of Cong | 560 | |

| The Chalice of Ardagh | 562 | |

| The Shrine of St. Manchan | 564 | |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | ||

| IRISH SCHOLARS ABROAD | ||

| I.— | St. Virgilius, Archbishop of Salzburg | 566 |

| Country of St. Virgilius | 566 | |

| [Pg xviii]Accusations against Virgilius | 569 | |

| Doctrine of the Antipodes | 570 | |

| Virgilius, the Apostle of Carinthia | 572 | |

| Discovery of the Tomb of Virgilius | 573 | |

| II.— | Sedulius, Commentator on Scripture | 574 |

| Writings of Sedulius | 574 | |

| III.— | John Scotus Erigena | 576 |

| Born in Ireland | 576 | |

| Patronised by Charles the Bald | 579 | |

| His Liber de Prædestinatione | 581 | |

| Alleged Errors about the Real Presence | 583 | |

| His Translation of the Pseudo-Dionysius | 584 | |

| His Treatise De Divisione Naturae | 586 | |

| This Book condemned A.D. 1225 | 587 | |

| His Death | 588 | |

| IV.— | Foreign Scholars in Ireland | 589 |

| College of Slane | 590 | |

| Dagobert, a Pupil of Slane | 590 | |

| Egbert in Ireland | 591 | |

| Studies in Connaught | 592 | |

| St. Chad in Connaught | 593 | |

| St. Willibrord in Ireland | 594 | |

| Agilbert, Bishop of Paris, in Ireland | 595 | |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | ||

| GAEDHLIC SCHOOLS AND SCHOLARS OF ANCIENT ERIN. | ||

| I.— | Organization of the Gaedhlic Professional Schools | 597 |

| The Learned Professions in Erin | 598 | |

| Degrees in Poetry, in Law, in History | 600 | |

| II.— | School of Tuaim Drecain | 602 |

| Three Schools at Tuaim Drecain | 602 | |

| Cennfaeladh, Professor in all the Faculties | 604 | |

| III.— | Cormac Mac Cullinan | 605 |

| Disert-Diarmada | 605 | |

| Cormac, King of Cashel | 607 | |

| Not Bishop of Cashel | 609 | |

| Cashel then a Royal Dun | 610 | |

| Battle of Ballaghmoon | 611 | |

| IV.— | Writings of Cormac Mac Cullinan | 612 |

| Psalter of Caiseal | 613 | |

| Cormac’s Glossary | 612 | |

| CHAPTER XXIV.—(continued). | ||

| I.— | Gaedhlic Scholars of the Sixth and Seventh Centuries | 614 |

| Amergin Mac Awley | 615 | |

| Dallan Forgaill | 616 | |

| II.— | Gaedhlic scholars of the Ninth and Tenth Centuries | 617 |

| Maelmura of Fathan | 617 | |

| Flann Mac Lonan | 618 | |

| Eochaid O’Flinn | 619 | |

| III.— | Gaedhlic Scholars of the Eleventh Century | 620 |

| Mac Liag | 620 | |

| His writings | 623 | |

| Cuan O’Lochain | 624 | |

| The Monastery of Buite | 625 | |

| IV.— | Discipline of the Lay Colleges | 628 |

| Relations between pupils and Teachers laid down in the Senchus Mor | 629 | |

| Corporal punishment sometimes inflicted | 630 | |

STATE OF LEARNING IN IRELAND BEFORE ST. PATRICK.

| “The wrath of Crom spoke in the storm, The blighted harvests felt his eye; The cooling shower, the sunshine warm, Answered the Druid’s plaintive cry.” —T. D. McGee. |

It is not our purpose to discuss at length the state of learning and civilization in Ireland before the coming of St. Patrick. It is a question about which much difference of opinion exists even amongst learned men. A few remarks, however, on this subject will enable the reader to understand more clearly the literature and history of the Christian Schools of Ancient Ireland.

It is admitted by all that whatever learning existed in Erin during the pagan period of her history, was the exclusive possession of certain privileged classes amongst the Celtic tribes. They may be included in the three great orders, so familiar to the students of our ancient history—the Druids, Bards, and Brehons. We shall offer a few brief observations about each of these highly privileged classes.[1]

I.—The Druids.

In Ireland, as in all the Celtic nations, the Druids were priests and seers, and frequently poets and judges also, especially in the earliest periods of our history. We know from Cæsar that their learning, at least in Gaul, consisted for the most part in rather fanciful theories about the heavenly bodies, the laws of nature, and the attributes of their pagan deities. These doctrines, like their religious tenets, were not committed to writing, but were handed down by oral tradition; for they wished above all things to keep their knowledge to themselves, and to impress the common people with a mysterious awe for their own power and wisdom. It has been said[2] by some writers that druidism[Pg 2] was a philosophy rather than a religion; but this statement cannot be admitted against the express testimony of Cæsar,[3] who must have often seen the Druids both in Gaul and Britain. He asserts[4] most distinctly that they attended to religious worship, offered sacrifice both in public and in private, and also expounded omens and oracles. Cæsar’s statement in this single sentence offers a text for our observations. We must bear in mind what he says of the Druids of Gaul, as well as of the British Druids; because it is quite evident that the Druids of the three great Celtic nations about this period had practically the same religion. He says that they had exclusive charge of public worship, sometimes even offered human sacrifice; and we shall show, notwithstanding O’Curry,[5] that they did the same in Ireland also. A similar long course of instruction, generally extending to twenty years, was required for their disciples in Ireland as in Gaul. As judges, too, the Druids enforced their decisions by a kind of social excommunication, which few people dared to despise. It is curious how the Celtic races, even to this day, have recourse to similar excommunications, both in things social and political. The Druids of Gaul were subject to an Arch-Druid, who was, like the Jewish High Priest, elected for life. But above all, the Druids of Gaul taught the immortality of the soul, as also its transmigration, and appeared most anxious to inculcate these doctrines on all their disciples. This is the one saving doctrine of druidism, which thus prepared the way for Christianity.

There were Druids amongst all the Celtic tribes of France, Britain, and Ireland. The British Druids in the time of Cæsar were very famous both as priests and scholars; so that it was customary for the young Druids of Gaul to be sent over to Britain to finish their education in the colleges of the British Druids. Their chief establishment was in the Island of Anglesey, anciently called Mona; so at least it is called by Tacitus, although Cæsar seems to give that name to the Isle of Man. During the period immediately preceding the arrival of St. Patrick in Ireland, it seems highly probable that Mona was occupied by a colony of the Irish Celts. It is certain, at least, that very frequent and friendly intercourse took place between Ireland and Anglesey, from[Pg 3] which it may be safely inferred that if the druidism of Anglesey was not of Irish origin, Irish as well as Gaulish Druids were certainly educated in that island.

The Druids worshipped not in temples made with hands. As in Palestine, and many Eastern countries, these pagan priests conducted their religious services in ‘groves’ and ‘high places’ under the shade of the spreading oaks, from which some writers derive their name—derw being the Celtic, not the Greek name for oak. Hence this tree was sacred in their eyes; their dwellings were surrounded with oak groves, whose dark foliage threw a sombre and solemn shade over the rude altars of unhewn stone on which they offered their sacrifices. The yew, blackthorn, and quicken were also regarded as sacred trees, at least by the Irish Druids, who made their divining rods in some cases from the yew, but oftener from oaken boughs. The mystic ogham characters were also cut by the Druids on staves made from the yew, at least so we are informed in some of our oldest Irish tales.[6]

Our knowledge of Irish druidism is derived chiefly from incidental references in the old romantic tales, and also in the Lives of the Saints, and especially in the Lives of St. Patrick, who came into direct antagonism with their entire system. It is certain that in other countries the Druids sometimes offered human victims in sacrifice; and there is some evidence that the same custom, although, perhaps, more rarely, prevailed in Ireland. There is a passage in the Book of Leinster,[7] which expressly states that the Irish used to sacrifice their children to Crom Cruach, or more correctly, Cenn Cruaich, the great gold-covered idol of Magh Slecht, on the borders of Cavan and Leitrim. Hence it was called the Plain of Slaughter, and the sight of the foul idol so excited the righteous zeal of St. Patrick that he smote it deep into the earth with a blow of his crozier. We also know from the Saint’s “Confession” that the Irish to whom he preached the Gospel, had previously worshipped idols and unclean things,[8] which goes to prove that idol-worship was a part of the druidical ritual in Ireland.

There is no doubt also that the worship of the elements was a part of the druidical religion. Their most terrible oaths were sworn on the Sun and the Wind; and it was confidently believed that the perjurer could never escape the vengeance of these mighty elements. The account given in[Pg 4] the Tripartite of St. Patrick’s interview with the daughters of King Laeghaire by Cliabach Well, on the slopes of Cruachan, shows that the worship of fairy gods, or elves, was a part of the druidical religion; and the same is expressly stated in the very ancient metrical Life of the Apostle, by St. Fiacc of Sletty.[9]

It is evident also not only from Cæsar’s statement, but also from several passages in our earliest extant writings, that one of the principal functions of the Druids was to act as haurispices, that is, to foretell the future, to unveil the hidden, to pronounce incantations, and ascertain by omens lucky and unlucky days. Hence we always find some of them living with the king in his royal rath; they are not only his priests, but still more his guides and counsellors on all occasions of danger or emergency. King Laeghaire had at Tara Druids and enchanters, who used to foretell the future by their druidism and heathenism;[10] and they announced the coming of the tailcend, or shaven-crown, that is St. Patrick, long before his arrival. They were powerful in charms and spells. They could bring snow on the plain, but could not, like Patrick, take it away; they could cover the land with sudden darkness, but could not, like him, dispel it. They were powerful for evil, but not for good; they could with the charm called the ‘Fluttering Wisp,’ strike their unhappy victim with lunacy, or afflict him by the elements; they would even promise to make the earth swallow him up, as they said it would swallow St. Patrick when he was preaching on the banks of the Moy in Tyrawley. Their incantations, too, were in some instances not only wicked, but filthy and unclean,[11] and as such were of course strictly prohibited by St. Patrick.

The Druids of Gaul, although unwilling to commit their doctrines to writing, were acquainted with the use of the Greek letters. The British Druids of Anglesey were even more learned; and we must infer that the Irish Druids possessed a similar culture. They had ‘books,’[12] when St. Patrick met them at Tara; and two of them were entrusted with the education of the king’s daughters at Cruachan. They were also skilled in medicine, and possessed a knowledge of healing herbs; they discoursed to their disciples on the nature of things,[13] and ad some [Pg 5]knowledge of astronomy. Thus vested with mysterious and supernatural powers, and possessed of an esoteric learning, that was exclusively their own, the Druids were held in great reverence and fear. “Tara was the chief seat of the idolatry and druidism of Erin,”[14] but we also find them at Cruachan in Connaught, and at Killala beyond the Moy[15]—both royal seats of the kings of that province. They accompanied the kings in their journeys and were present sometimes on the field of battle.[16] They were generally dressed in white, but wore an inner tunic to which reference is sometimes made. It is probable that one or more of them abode in the Raths of all the great nobles, who claimed to be righs, or kinglets, in their own territories. They were sworn enemies of Christianity, and frequently attempted to take St. Patrick’s life by violence or poison. In the remote districts of the country some of them remained for several centuries after the island generally became Christian; and to this day we can find traces of ancient druidism in the superstitions of the people.

Their New Year’s Day was about the 10th of March, and was deemed holy as the great day on which they cut the mistletoe from the sacred oak. The first of May was kept as a festival in honour of the Sun-God; and probably gave origin to that custom of lighting fires in honour of the god, which was afterwards transferred to the eve of the 24th of June, in order to do honour to St. John.

St. Patrick in his Confession clearly refers to this sun-worship as an idolatrous practice prevalent amongst our pagan forefathers. “That sun,” he says, “which at His bidding we see rising daily for our sake will never reign, and its splendour will not last for ever; but those who adore it will perish miserably for all eternity.” The great November festival called Samuin, seems to have been held especially in honour of the side, or fairy-gods, who dwelt in the bosom of the beautiful green hills of Erin, and were supposed to hold high revel throughout all the land on November Eve. But the Druids had influence even with these gods of the hills; and we are told that when Edain, the lovely queen of royal Tara, was stolen away from her husband, and hidden in the Land of Youth under Bri Leith, near Ardagh, in Longford, she was restored to her home and her husband by the mighty magic of Dallan the Druid.

[Pg 6]We find reference made to the Druids as present with every colony that came to Erin, which shows at least that the old bards and chroniclers regarded them as an essential element of the nation. They were endowed with lands for their maintenance, and enjoyed special privileges and immunities, like the Bards and Brehons. But, as they were the priests of a false and idolatrous religion, it was sought as far as possible to remove every trace of their existence from the minds of the people; and hence after the revision of the Brehon Laws in the time of St. Patrick, we find all reference to the Druids, their rights, and their privileges, entirely expunged from that ancient code. Accordingly we know nothing about the Irish Druids, except what may be gathered from such accidental references as those to which we have already referred.

II.—The Bards.

Under this term we include both poets and chroniclers that is, the Fileadh and the Fer-comgne.[17] Sometimes history and poetry are represented as distinct branches of learning in ancient Erin; it is certain, however, that in pre-Christian times, and long after the introduction of Christianity, the chronicler made poetry the medium of preserving and communicating to posterity both the genealogical and historical records of his tribe or clan. It is true, indeed, that the Introduction to the Senchus Mor makes a careful distinction between the chronicler and the poet. “Until Patrick came, only three classes of persons were permitted to speak in public in Erin: a Chronicler to relate events and to tell stories; a Poet to eulogise and to satirize; a Brehon to pass sentence from precedents and commentaries.” It is added that since Patrick’s arrival, each of these professions is subject to his censorship; and it is noteworthy that no reference at all is made to the Druids after Patrick came to Erin, and this Brehon Code came to be purified. The commentator on the Senchus also notes that for a long time the judicature had belonged to the poets alone, that is, from the time of Amergin, the first poet-judge, down to the time of the Contention at Emhain Macha between the two Sages, Ferceirtne and Neidhe. The language which the poets spoke on that occasion was so obscure, that the chieftains could not understand what had passed between the rival Sages. It was therefore ordained by Conchobhar (Connor) and his chieftains, that thenceforward the[Pg 7] poets should be deprived of that exclusive privilege which they had hitherto enjoyed, and made too exclusive; and that the men of Erin in general should be entitled to have their proper share in the judicature. This dim tradition clearly represents a protest against the technical language of an exclusive and privileged class, who, for their own purposes, sought to keep secret their traditionary lore. Thus it came to pass that thenceforward the profession of the judge and poet became quite distinct, and the judge assumed the post of official chronicler and keeper of the records of his tribe.

The function of the Bard, or poet, afterwards was ‘to eulogize and to satirize;’ and in this more restricted sense of the word the term poet or Bard is frequently employed in Christian times. We know, however, that as a matter of fact all our historical documents down to the tenth century are written in poetry, that is, in a certain metre and rhythm, which would help to preserve these compositions even without the aid of writing for the benefit of posterity; that is to say, the Chronicler was also a poet.

The File, or poet in the more restricted sense of the word, soon became a pest and a nuisance. He was willing enough to eulogize when he expected liberal rewards; but if he were disappointed in his hopes, or if from any other cause he wished to inflict the lash of his satire on any person, he never spared the poisoned shafts of his flashing wit. Hence Cormac Mac Cullinan, who knew the tribe well, derives File, the old Irish word for poet, from fi, poison, and li, brightness; because in eulogy the poet is bright, but in satire he is venomous. The poets were extortionate, too, in exacting rewards for their eulogistic verses, so that the order came to be more feared than loved, and at length incurred the danger of extinction, as we shall see further on. Hence, too, it is expressly ordained in the Senchus Mor that the poet who demands an excessive reward, or claims an amount to which he is not entitled, or composes unlawful satire, is to be deprived of half his ‘honour price’ for the first and second offence, and of his full honour price, or social status, for the third. Among the four dignitaries of a territory who might be degraded, besides the false-judging king, the stumbling bishop, and the unworthy chief, was the fraudulent poet, who demanded an exorbitant reward for his compositions.

No man was qualified to become Chief-poet, or Doctor in Poetry—‘Ollamh-poet’—who was not able to compose an extempore stanza on any subject proposed to him. And the way in which it is done is this: “When the poet sees the[Pg 8] person or thing before him he makes a verse at once with the ends of his fingers, or in his mind without studying, and he composes and repeats at the same time.”[18] This, however, was after the reception of the New Testament in the time of St. Patrick. “Before Patrick’s time the poet placed his (divining) staff upon the person’s body, or upon his head, and found out his name, and the name of his father and mother, and discovered every unknown thing that was proposed to him in a minute or two or three.” But St. Patrick abolished these profane rites amongst the poets when they believed, for they could not be performed without offering to idol gods, and thenceforward he made the profession pure.[19]

The chief duty of the Historic Poet, or Chronicler, was to register the genealogies of the men of Erin, and to recite lays of battle, and rhymed stories or tales of Courtships, Voyages, Cattle-spoils, Sieges, Slaughters, and other moving incidents by field and flood. The Ollamh-poet, or Doctor of Poetry, was required by law to spend at least twelve years in careful preparation for his final degree, and to have prepared for public recitation seven times fifty tales or stories of the character already indicated. He was also required to be perfectly familiar with the pedigrees of the principal families, their topographical distribution, the synchronisms of remarkable events both at home and abroad, and the etymologies of names in Erin. He was besides required to know the artistic rules of poetry, and to have a knowledge of the seven kinds of verse and their various metres. It is evident that these manifold accomplishments required long and careful study; and the necessity of this training explains, what many persons think incredible, the wonderful accuracy of our ancient historical and genealogical records, which the evidence of facts now proves to be on the whole undoubtedly authentic and trustworthy documents.

In the Book of Ballymote there is a long list of great historians and poets, who flourished in ancient Ireland; many of them, however, are now known only by name. All our ancient records point to the fact that the Tuatha de Danaan, who colonized this country before the Milesians, were a people of considerable civilization. Their royal family seems to have possessed great culture. Daghda, the king, and his wife the Great Queen—Mor Rigan—are both represented as distinguished poets, who flourished more than 1,000 years before[Pg 9] Christ. Diancecht, the royal physician, was also a distinguished judge and poet; his daughter, the princess Etan, was a poetess; and her son was no less remarkable for poetic talent. About the same period flourished the poet Ogma, the traditional inventor of the Ogham alphabet.

The Milesians cultivated poetry with equal zeal. We have already referred to the poet-judge, Amergin, and we are told that a poet called Cir, and a harper named Ona, were amongst the first Milesian colonists. After the conquest of the country by the brothers Heber and Heremon, it was resolved to cast lots for the possession of these distinguished bards. The poet fell to Heremon and the harper to Heber, whence it came to pass that the Northerns were, in after times, distinguished for poetry; but the gift of music remained with their Southern brothers.

There is still extant[20] a curious genealogical poem attributed to Conor of the Red-Brows (about B.C. 6) which O’Curry seems to have regarded as genuine. But the most remarkable remnant of pre-Christian literature, if, indeed, it can be regarded as such, is the Dialogue of the two Sages, which is attributed to the reign of Conor Mac Nessa, king of Ulster, about the period of the birth of Christ. These two sages were Ferceirtne, the royal poet of Emania, and Neidhe, son of Adhna, the predecessor of Ferceirtne in the Chair of Poetry. The young Neidhe, after completing his education at home, went to Scotland, where he still further pursued his studies. Upon learning the death of his father he returned home, and happening to find the chief poet’s chair just then empty by the temporary absence of the Professor Ferceirtne, who had succeeded his father, he put on the poet’s Gown which he found lying on the chair, and sat down himself in state in the vacant seat. Thereupon Ferceirtne returned, and finding his place occupied, asked in poetic phrase who was the distinguished stranger upon whom rested the splendour of the poet’s Gown. Neidhe answered him in language as poetic as his own, and thereupon began the famous Dialogue, in which the rival poets displayed all their various accomplishments in literature, history, and druidism. The victory was finally gained by the youthful Neidhe, who proved himself fully worthy of his father’s Chair; but with modest condescension he yielded the place to the elder Ferceirtne, and consented to become his pupil and destined successor. The language of the Dialogue shows its great antiquity; but the frequent allusions, although only by way of prophecy to Christian usages, throw grave doubt, on its authenticity.

[Pg 10]Learning is said to have greatly flourished in Erin during the reign of Conor Mac Nessa. He was certainly a bountiful benefactor to the poets; and, when their numbers and avarice raised loud complaints against them in other parts of the country, he invited the whole tribe to his own kingdom of Ulster, where he entertained them hospitably for seven years.

Ollioll Olum, that is Ollioll the Sage, was, as his name implies, a learned poet, who flourished from A.D. 186 to 234. He is said to have written several poems of great merit, three of which, according to O’Curry, are still preserved in the Book of Leinster. It is said also that Finn Mac Cumhaill was a poet as well as a warrior; and several poems are attributed to him in our ancient books.

He was at least the father of Erin’s greatest poet—from him and “Graine of the golden hair the primal poet sprung.” Finn flourished during the later heroic period, which corresponds to the third century of the Christian era. Ossian, or more properly Oisin, his son, is the Homer of Gaedhlic song, whose name and fame have floated down to us on the stream of time from those far distant and misty ages. Many poems still extant are attributed, and perhaps justly, to the grand old warrior Bard of Erin. The publications of the Ossianic Society have done much to make the history of the heroic period familiar to modern readers. More than one of our Irish poets,[21] too, have, with the quick ear of genius, caught up the faint echo of Ossian’s song, and once more attuned the harp of Erin to the thrilling melodies of her heroic youth. Once more the Fenian heroes begin to tread the hills of fame, and the spirit of Ossian’s vanished muse, like the quickening breath of spring, is felt over all the land.

Ossian! two thousand years of mist and change

Surround thy name—

Thy Fenian heroes now no longer range

The hills of fame.

The very name of Finn and Goll sound strange—

Yet thine the same,

By miscalled lake and desecrated grange,

Remains, and shall remain.

The Druid’s altar and the Druid’s creed

We scarce can trace;

There is not left one undisputed deed

Of all your race,

Save your majestic song, which hath their speed

And strength and grace,

In that sole song they live and love and bleed,

It bears them on through space.

—T. D. M‘Gee.

III.—The Brehons.

They formed the third of the learned and specially privileged Orders in ancient Erin. During the pre-Christian period the customary laws, by which the Celtic tribes were governed, were formulated in brief sententious rhymes. These rhythmical maxims of law were at first transmitted orally, but afterwards in writing from each generation of Poets to their successors. For up to the first century of the Christian era the Files or Poets had not only the custody of the laws, but also the exclusive right of expounding them to the people, and pronouncing judgments both civil and criminal. Even when the King himself undertook to adjudicate, the File was his official assessor, and the royal judge was guided by his advice in the administration of justice. The Poets were exceedingly jealous of this great privilege, and in order to exclude outsiders from any share in the administration of the law they preserved the archaic legal formula with the greatest secrecy and tenacity.

But as we have already seen, this jealous spirit over-reached itself, and in the reign of Conor Mac Nessa the men of Erin resolved to deprive the Poets of this exclusive privilege, and throw open the office of Brehon to all who duly qualified themselves by acquiring the learning necessary to enable them to discharge its duties.

It was after the office was thus thrown open to men of talent and industry that some of those ancient judges flourished in Erin, whose names and decisions are spoken of with the greatest reverence in the Senchus Mor. “It was,” we are there told, “Sen, son of Aighe, who passed the first judgment respecting Distress at a territorial meeting held by the three noble tribes who divided this island.” This points to legislation on the subject of Distress formulated at a tribe-assembly by a great jurist, and then solemnly ratified by popular consent. The gloss on this text adds that Sen was of the men of Connaught, and that the meeting was held at Uisnech in Westmeath. Another distinguished judge was Sencha, son of Ailell, on whose face three permanent blotches appeared whenever he pronounced a false judgment. Connla Cainbrethach (of the Fair Judgments) was the chief legal doctor of Connaught; he excelled the men of Erin in wisdom, for he was “filled with the grace of the Holy Ghost.”[22] He it was who said that it was God, and not the Druids, who made the heavens, and the earth, the sun and the moon and[Pg 12] the sea. This seems to imply that Connla was wise and courageous enough to reject the philosophy, and probably also the worship of the Druids. The Light had already arisen in the east, and the first faint dawnings of Christianity were beginning to illumine the horizon of Erin. Morann, another great judge, who flourished during the first century of our era, wore a chain around his neck, and if ever he pronounced a false judgment the chain tightened around his neck; but it began to expand again, when he came to speak what was just and true. These and other great judges of the same period appear to be undoubted historical characters, whose wisdom and learning, hallowed by the reverence of ages, appeared to their successors to be in some way divinely inspired. They were, it is true, at the time without the light of Revelation to guide them, but as the gloss says, the grace of the Holy Ghost would not be wanting to help men, who were striving according to their conscience to be just and good.

Cormac Mac Art, of whose writings we shall presently speak, did much to encourage the systematic study of law amongst the Brehons. He appears to have been the first who reduced to writing the traditional legal maxims of the Brehon’s court, and thus may be regarded as the author of the earliest Code of Laws in pagan Ireland. This great work was afterwards purified and perfected in the time of St. Patrick, when the Senchus Mor, as it is now known, was first compiled.

These three Orders of Druids, Bards, and Brehons were, as we have seen, close corporations, invested with many privileges, and communicating a professional knowledge for the most part by oral instruction to their disciples. This course of instruction was very long and elaborate, sometimes extending to a period of twenty years. It included, as in more modern times, various steps or degrees of learning, the highest of which always was that of Ollamh or Doctor, whether in law, poetry, or divinity. The ordinary course was twelve years, and each year’s work seems to have been as carefully fixed as in a modern college or university. A great portion of the work, after the purely elementary studies, consisted in getting off by rote either the bardic tales, or legal maxims with their leading cases, or historical poems and genealogies. This included a very perfect knowledge of topography, chronology, and family history. Versification of a very artificial and complicated character was also a portion of the programme. Besides the students had undoubtedly, at least in pre-Christian times, some kind of ‘secret’ language known only to the initiated. It would seem as if each [Pg 13]profession or school had its own peculiar Oghamic alphabet, the key of which was known only to themselves; but in this matter we have no certain knowledge, and are left almost entirely to pure conjecture. Hereafter we shall see that the legal relations between the professor and his pupils were definitely ascertained, and are laid down in that portion of the Brehon Code which deals with the Law of Social Connections.

IV.—The Ogham Alphabet.

We shall see presently, when treating of the literary history of Cormac Mac Art, that the use of letters, and most probably of Roman letters, was quite common in Erin before the coming of St. Patrick. Besides the Roman alphabet there was, however, an earlier and ruder alphabet, which seems to have been used in Erin even in the pre-historic times. This is called the Ogham alphabet which has had a very strange and curious history. It is a singular fact that all knowledge of the Ogham alphabet, as well as of the existence of any inscriptions written in its peculiar characters, had for a considerable period completely disappeared from the minds of Irish scholars. Yet the Ogham score was all the time contained in the Book of Ballymote,[23] and the key to its interpretation also. Inscribed stones too were thrown about unnoticed in various parts of the country down to the year 1820, when Mr. John Windele discovered the first inscription in the co. Cork.

Since that time no less than 200 inscribed stones have been discovered in various parts of the country, but especially in the South and West; and Irish scholars have directed their attention to decipher and explain these mysterious and time-worn lines. Twenty-two stones inscribed with similar characters have been found in Wales and Devonshire, that is in the South and West of England, and ten in Scotland. Almost all these inscriptions have been examined by the late Mr. Brash of Cork, a most painstaking and accurate investigator, who has published the result of his labours in a very interesting work on the subject.[24] His conclusions may be briefly summed up as follows[25]:—

The inscriptions have been invariably found on pillar stones and flags, and are nearly all of a sepulchral character. The lettering is in a style peculiar to the Gaedhlic race, and represents a very ancient dialect of the Gaedhlic language. The inscribed stones are found only in those districts, where[Pg 14] the Gaedhils are known to have established themselves; and the mode of forming the characters and formulating the inscriptions is the same in Ireland, in Wales, and in Scotland. He asserts, moreover, that no Ogham monument hitherto discovered bears any trace of any Christian formula, or any symbol of Christian hope;[26] that any such symbols when found upon an Ogham stones, are manifestly of later date than the original inscription; and that the allusions in our ancient MSS. to the Ogham mode of writing have reference only to pre-Christian times. He thinks too that the Ogham mode of writing was not invented in Ireland, but carried to this country by a colony that landed on our south-western shores, and moved gradually from West to East, and thence across the Channel to Wales. He adds that in all probability this colony came originally from the East, then settled for some time in Egypt, and migrated thence to Spain—conclusions that are all in conformity with the common traditional account of the advent of the Milesian race to this country, as contained in our own ancient Books.

The invention of the Ogham is attributed in bardic history to Ogma, son of Elathan, a prince of the Tuatha de Danaans, that people whom all our national traditions represent as a more cultured race than any of the other colonies that took possession of this island in primitive times. The most singular fact connected with the Ogham inscriptions is their geographical distribution. They are in Ireland almost all confined to the South and West, and to those parts of Wales and England that could be most easily reached from the South of Ireland. The few inscriptions found elsewhere in Ireland are only found in those places, to which we have reason to know that families from the South-West migrated in early times. This certainly would seem to indicate that an immigrant colony landed somewhere in Kerry; and gradually diffusing themselves through the country carried this archaic form of writing along with them; but either they never succeeded in occupying the whole country, or before the occupation of the remoter parts they gradually gave up the Ogham, and adopted a form of writing more suitable for general use, but not so well adapted for brief permanent inscriptions in stone. Mr. Brash has declared that no Oghams of a Christian character have yet been discovered, nor is there any coeval reference to any Christian symbols on the Ogham pillar-stones, a fact which, if true, clearly proves that all the Oghams date from Pagan times. In most cases they are sepulchral inscriptions of the briefest character, merely giving[Pg 15] the name of the deceased and the name of his father with, in a few instances, one or two short laudatory epithets.

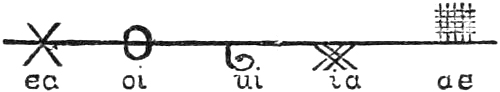

The letters of the Ogham alphabet are divided into four groups of five letters each, twenty in all. Taking the angular edge of the upright pillar to be represented by a straight line the following is the score:—

Besides these we find a few dipthongal symbols, but apparently of later date:—

The line on which the letters are written is nearly always the rectangular line on the left hand side of the upright flag, facing the spectator. The inscription begins below at the left hand corner, and is read upwards, but sometimes it is continued downwards on the right hand angular line of the pillar on the same face. The vowels are generally not much larger than points on the very angle of the stone, or very short lines cutting the angular line; the consonants are much longer scores drawn to the left or to the right of the angular line as the word requires; the last five scores are longer lines across the angular line and oblique to it.[27]

From various references in our ancient MSS. it appears that the Oghams were written not merely on stones, but also on rods and tablets of wood, which could be easily tied up in bundles and carried from place to place. A letter written to a friend might thus consist of a bundle of rods, duly marked and numbered. The bark of trees, being easily notched, was probably used for the same purpose, and thus even before the introduction of parchment and Roman letters, there would be no want of writing materials. There is no evidence that before the introduction of Roman letters there was any other kind of alphabet in use except the Ogham. But as the Druids of Gaul, in the time of Cæsar, were acquainted with the use of the Greek letters, why should not the ‘more learned’ Druids of Britain and Ireland be familiar with the Greek or Roman alphabet? It will be seen in the next chapter that there is every reason to conclude that at least after the Roman occupation of Britain, they were quite familiar with Roman letters and Roman writing.

IRISH SCHOLARS BEFORE ST. PATRICK.

| “Crom Cruach and his sub-gods twelve,” Said Cormac, “are but carven treene; The axe that made them, haft and helve, Had worthier of our worship been.” —Ferguson. |

We are frequently told that before the time of St. Patrick the Irish were an utterly barbarous people like the North American Indians. They had of course an unwritten language, but neither scholars, learning, nor even letters. Vague statements of certain Roman writers are cited in proof of these assertions—we shall appeal to the evidence of facts. The Roman writers of that period knew far less of ancient Ireland than even we do at present. It was beyond the sphere of their knowledge, as well as of their empire. But as a matter of fact the statements of Roman historians, so far as they go, tend to prove that a considerable amount of civilization existed in Erin during the time of the Roman occupation of Britain; and in proof of this statement it is quite enough to examine the history of Cormac Mac Art.

I.—Cormac Mac Art.

The reign of Cormac Mac Art furnishes, perhaps, the most interesting chapter in the history of pre-Christian Ireland. He may be regarded with justice as the greatest king that ever reigned in ancient Erin. He was, as our poets tell us, a sage, a judge, and a scholar, as well as a great prince and a skilful warrior. His reign furnished, indeed, many rich themes for the romantic poets and story-tellers of subsequent ages, in which they greatly indulged their perfervid Celtic imagination. But the leading facts of his reign are all within the limits of authentic history, and are provable by most satisfactory evidence.

Cormac was the son of Art the Solitary, or the Melancholy, as he is sometimes called, and was grandson of the celebrated Conn the Hundred-Fighter. Hence he is sometimes called Cormac O’Cuinn, as well as Cormac Mac Art. His father was slain about the year A.D. 195, in the great battle of[Pg 17] Magh Mucruimhe where, as at the battle of Aughrim in the same county, a kingdom was lost and won. Magh Mucruimhe was the ancient name of the great limestone plain extending from Athenry towards Oranmore; and the spot where King Art was killed has been called Tulach Art even down to our own times. It was between Oranmore and Kilcornan, and close to the townland of Moyvaela.[28] The victor in this great battle was Lughaidh, surnamed Mac Con, who had been for many years a refugee in Britain, and now returned with the king of that country and a host of foreigners to wrest the kingdom from Art, who was his maternal uncle. The flower of the chivalry of Munster perished also on that fatal field; for the seven sons of Ollioll Olum who had come to assist King Art, their mother’s brother, were slain to a man on the field or in the rout that followed.

Fortunately for young Cormac, the king’s son, he was just then at fosterage in Connaught, probably with Nia Mor, who was his cousin, and one of the sub-kings of the province at that time. So Mac Con, the usurper, found no obstacle to prevent him assuming the sovereignty of Tara; and we are told that he reigned some 30 years, from A.D. 196 to 226.

Meantime young Cormac was carefully trained in all martial exercises, as well as in all the learning befitting a king, until he came to man’s estate. Then he came to Tara in disguise, and according to one account, was employed in herding the sheep of a poor widow, who lived close to Tara, when some of the sheep were seized for trespassing on the queen’s private green or lawn. When this case of trespass was brought before the king in his court on the western slope of the Hill of Tara, he adjudged that the sheep should be forfeited for the trespass. “No,” said Cormac, who was present, “the sheep have only eaten of the fleece of the land, and in justice only their own fleece should be forfeited for that trespass.” The bystanders murmured their approval, and even Mac Con himself cried out—“It is the judgment of a king”—for kings were supposed to possess a kind of inspiration in giving their decisions. Then immediately recognising Cormac, whom he knew to be in the country, he tried to seize him on the spot. But Cormac leaped the mound of the Claenfert, and not only succeeded in effecting his escape, but also in raising such a body of his own and his father’s friends, that he was able to drive the usurper from Tara. Mac Con fled to his own relatives in the South of Ireland, where he was shortly afterwards killed, at a place called Gort-an-Oir, near Cahir, in the Co. Tipperary.